To the Editors:

Use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in pregnancy is estimated to limit mother-to-child/vertical HIV transmissions to <2% versus up to 45% in breastfed children born to HIV-infected mothers not receiving ART.1,2 However, safety data on ART use in pregnancy remain sparse due to exclusion of pregnant women from clinical trials and underreporting by health care professionals to existing databases such as the antiretroviral pregnancy registry (APR). Review of additional data can help assess benefits and risks of specific ART regimens.

Dolutegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, has increasingly been used as first-line ART in people with HIV. No evidence of teratogenicity or developmental toxicity in animal studies or early clinical trials in women with unplanned pregnancies while taking dolutegravir was identified.3 In May 2018, new data were reported from an unplanned interim analysis of 426 infants born to women taking dolutegravir at conception from the Botswana Birth Outcomes Surveillance Cohort (Tsepamo study). Four neural tube defects (NTDs; anencephaly, encephalocele, iniencephaly, myelomeningocele) were reported, resulting in a prevalence of 0.94% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.37 to 2.4],4,5 compared with 14/11,300 infants (0.12%; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.21) born to women taking non–dolutegravir-based ART at conception and 61/66,057 infants (0.09%; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.12) born to HIV-uninfected women in this study. In a subsequent analysis from March 2019, the prevalence rate with dolutegravir taken at conception had decreased to 0.30% (95% CI: 0.13 to 0.69) due to an increased denominator (5/1683). Among infants born to women who started dolutegravir during pregnancy, the prevalence of NTDs was 1/3840 (0.03%; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.15).6

NTDs are congenital abnormalities involving the brain, spine, or spinal cord that result from failure of the neural tube to close completely, a process normally completed by the end of the first month of pregnancy.7,8,9,10 Risk factors include folate deficiency, obesity, uncontrolled maternal diabetes, maternal fever, and medications such as carbamazepine and valproic acid.7,11,12 In the Tsepamo study, none of the 5 women taking dolutegravir at conception who delivered an infant with an NTD was reported to be taking folic acid supplementation before pregnancy, and folate supplementation of grain products is not standard practice in Botswana. No other risk factors for NTDs in these women were reported.5

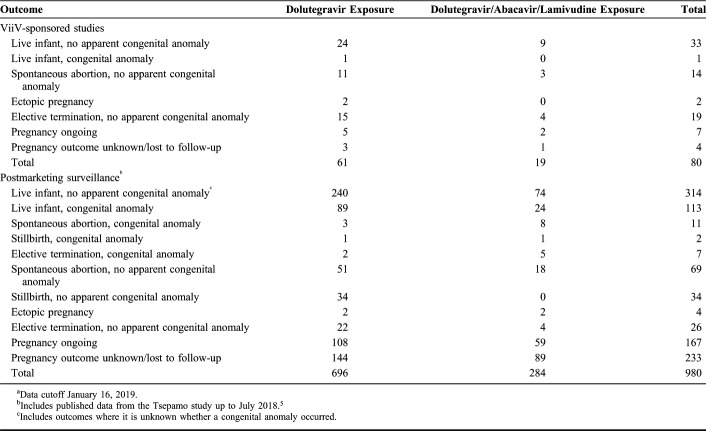

Here, we report pregnancy outcomes in women taking dolutegravir and their infants who have been recorded in the ViiV Healthcare global safety database, which includes cases received through spontaneous (voluntary) reporting, postmarketing studies, and ViiV Healthcare–sponsored clinical trials. As of January 16, 2019, 1060 pregnancies with exposure to dolutegravir-containing products were identified, with 757 pregnancy outcomes with dolutegravir exposure and 303 with the fixed-dose single-tablet dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine (Table 1). From the combined data set, 80 cases were from ViiV Healthcare–sponsored clinical trials, 500 were from spontaneous reports, and 480 were from postmarketing studies or studies supported by ViiV Healthcare (including the APR). These included 47 cases reporting pregnancy exposures identified from the published literature.

TABLE 1.

Cumulative Pregnancy Outcomes Reported After Maternal Exposure to Dolutegravir During a ViiV-Sponsored Study or Postmarketing Surveillancea

Overall, 134 congenital abnormalities were identified in individuals exposed to dolutegravir (n = 96) or dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine (n = 38) during pregnancy. Of these, data from 104 abnormalities came from postmarketing studies or studies supported by ViiV Healthcare (generally designed to study dolutegravir use in late-stage pregnancy), 29 from spontaneous reports, and 1 from a ViiV Healthcare–sponsored clinical trial. Forty-three of the congenital abnormalities were cases of umbilical hernia, with 37 occurring in the DolPHIN-2 study (ongoing in Uganda and South Africa) investigating efficacy and safety of third-trimester dolutegravir exposure in pregnant HIV-infected women.13 The majority of the remaining cases was related to the nervous system (n = 14), cardiac system (n = 13), and musculoskeletal system (n = 8). Of the 116 reports of congenital abnormalities that provided information on the trimester of exposure, 49 were exposed to dolutegravir or dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine in the first trimester (including 33 cases exposed at conception), 20 in the second trimester, and 47 in the third trimester.

There have been 9 reported and confirmed cases of NTDs with mothers who were exposed to dolutegravir or dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine: 6 from the Tsepamo study (5 with exposure at conception and 1 with exposure to dolutegravir started during pregnancy; study data as of March 2019)6 and 3 spontaneous cases as of January 31, 2019 (1 from Namibia, reported in January 2017 and 2 from the United States, both reported in June 2018).

Of the 3 cases of NTDs reported spontaneously to ViiV Healthcare outside of the Tsepamo study, 1 case was from a woman in Namibia who had been receiving dolutegravir for several months before conception. Treatment with dolutegravir continued until an unspecified NTD was diagnosed in utero. No information was provided on concomitant medications or medical or family history. The other 2 cases were both from the United States and involved women who had taken dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine for ≥1 year before conception. In both cases, the NTDs (anencephaly, sacromeningocele) were diagnosed during prenatal ultrasound. Both infants were carried to term, 1 died after delivery, whereas the other was reported to be doing well after surgical closure of the sacromeningocele. Neither mother was reported to have taken folic acid supplementation preconception. Neither woman had taken medications recognized as associated with NTDs or had a current diagnosis of epilepsy or diabetes, although 1 had a history of seizures and 2 previous spontaneous abortions, and the other had a body mass index >30 kg/m2, indicating a potentially elevated risk.

Although reporting postmarketing surveillance data is important, they are limited by the inability to calculate prevalence rates because the true denominator is not available and births without defects are underreported. Cumulative exposure to dolutegravir-containing products is estimated to be >1.3 million patient-years, but the number of women who have taken dolutegravir during pregnancy is unknown. Although the limitations of postmarketing surveillance data are well recognized, the number of spontaneous reports of NTDs with dolutegravir-containing regimens has been low when viewed in the context of global dolutegravir use and awareness of the NTD signal among prescribers since the Tsepamo study findings were first reported.

To detect associations of drug exposure with rare events like NTDs, ∼2000 pregnancies with drug exposure collected in a structured manner are needed to determine a 3-fold increased probability of the event occurring.14 In 2018, the Botswana Birth Outcomes Surveillance study expanded to include surveillance from 8 to 18 sites, with plans to include data from an additional 1226 births of infants exposed to dolutegravir at conception.5 In addition, the Ministry of Health of Brazil, in partnership with the National Institutes of Health, Vanderbilt University, and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, has initiated a national, retrospective, observational cohort study to evaluate the incidence of NTDs after dolutegravir exposure during pregnancy, estimate the risk of NTDs in infants born to women receiving dolutegravir and raltegravir at conception, and evaluate factors associated with the risk of NTDs in infants born to women who received dolutegravir at conception.15 ViiV Healthcare is conducting or supporting several observational studies to assess dolutegravir use in pregnancy, including the APR,16 as well as the DOLOMITE-EPPICC17 and DOLOMITE-NEAT ID NETWORK18 studies that include European data. These emerging data will be critical in making a more definitive judgment about the potential risk of dolutegravir use during pregnancy.

It is important that the potential benefits of any ART during pregnancy are carefully weighed against the potential risks to the developing fetus, keeping in mind that untreated HIV infection during pregnancy has also been associated with adverse birth outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm birth, and stillbirth compared with HIV-negative controls.19 In addition, lack of ART or delayed ART initiation in pregnant women increases the risk of vertical transmission.20,21 To further minimize this risk, full viral suppression by delivery is a vital treatment goal for pregnant HIV-infected women.22 Dolutegravir-based therapy in pregnancy is generally effective with a good maternal safety and tolerability profile. Overall, the rate of adverse birth outcomes following dolutegravir exposure after conception has been consistent with that observed for other ART regimens and the general population,16,23 but the potential association of dolutegravir exposure at the time of conception with the development of NTDs requires further study. Until the NTD signal is confirmed or refuted, ViiV Healthcare recommends that women of childbearing potential who are taking a dolutegravir-based regimen use effective contraception.24 If pregnancy occurs while taking a dolutegravir-based regimen and the pregnancy is confirmed within the first trimester, the benefits and risks of switching to an alternative regimen should be considered.24 For those women planning to become pregnant, switching to an appropriate alternative regimen, if possible, is recommended.24 Treatment guidelines for HIV, including those from the US Department of Health and Human Services, recommend a similar approach and allow for dolutegravir use after the first 14 weeks of pregnancy.25 Updated guidelines from the World Health Organization in July 2019 now recommend that dolutegravir can be prescribed in all women of childbearing potential, including those planning pregnancy as well as during pregnancy, provided the woman is fully informed of the potential increased risk of NTDs (at conception and until the end of the first trimester).26 At this time, available data do not indicate any specific safety risk with dolutegravir use after the first trimester of pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Editorial assistance was provided under the direction of the authors by Jeffrey Stumpf, PhD, and Jennifer Rossi, MA, ELS, MedThink SciCom, and was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

Footnotes

M.C. and L.C. are employees of GlaxoSmithKline and may own stock in GlaxoSmithKline. J.v.W., M.A., V.V., B.R., B.W., A.d.R., K.S., and N.P. are employees of ViiV Healthcare and may own stock in GlaxoSmithKline. This research was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegfried N, van der Merwe L, Brocklehurst P, et al. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey H, Zash R, Rasi V, et al. HIV treatment in pregnancy. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e457–e467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tivicay [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: ViiV Healthcare; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-tube defects with dolutegravir treatment from the time of conception. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:979–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zash R, Holmes L, Makhema J, et al. Surveillance for neural tube defects following antiretroviral exposure from conception. Presented at: 22nd International AIDS Conference; July 24, 2018; Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- 6.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural tube defects by antiretroviral and HIV exposure in the Tsepamo study, Botswana [MOAX0105LB]. Presented at: 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science; July 22, 2019; Mexico City, Mexico.

- 7.Wilde JJ, Petersen JR, Niswander L. Genetic, epigenetic, and environmental contributions to neural tube closure. Annu Rev Genet. 2014;48:583–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaganjor I, Sekkarie A, Tsang BL, et al. Describing the prevalence of neural tube defects worldwide: a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene ND, Copp AJ. Neural tube defects. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:221–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavalli P. Prevention of neural tube defects and proper folate periconceptional supplementation. J Prenat Med. 2008;2:40–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copp AJ, Greene ND. Neural tube defects—disorders of neurulation and related embryonic processes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2:213–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279–e290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kintu K, Malaba T, Nakibuka J, et al. ; for the DolPhin-2 Study Group. RCT of dolutegravir vs efavirenz-based therapy initiated in late pregnancy: DolPHIN-2 [40 LB]. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 5, 2019; Seattle, WA.

- 14.Mofenson LM. Overview on safety of HIV treatment in pregnancy. Presented at: 22nd International AIDS Conference; July 24, 2018; Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- 15.Benzaken AS. Brazil experience: active toxicity monitoring in adults and birth defect surveillance with DTG: country experience in monitoring new ARVs: focus on toxicity monitoring and surveillance of DTG during pregnancy to inform treatment policy. Presented at: 22nd International AIDS Conference; July 27, 2018; Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- 16.Vannappagari V, Thorne C; for APR and EPPICC. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes following prenatal exposure to dolutegravir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81:371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ViiV Healthcare Study Register. ViiV Study ID: 208613. ViiV Healthcare UK Limited; 2019. Available at: https://www.viiv-studyregister.com/study/19664. Accessed May 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to Define Safety and Effectiveness of Dolutegravir (DTG) Use in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Positive Pregnant Women. ClinicalsTrials.gov; 2019. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03564613. Accessed May 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedi CO, Kirtley S, Hopewell S, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with maternal HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e33–e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.British HIV Association. British HIV Association Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Pregnancy and Postpartum 2018 (2019 Interim Update). British HIV Association; 2019. Available at: https://www.bhiva.org/file/5bfd30be95deb/BHIVA-guidelines-for-the-management-of-HIV-in-pregnancy.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugdale CM, Ciaranello AL, Bekker LG, et al. Risks and benefits of dolutegravir- and efavirenz-based strategies for South African women with HIV of child-bearing potential: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:614–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines Version 9.1. European AIDS Clinical Society; 2018. Available at: http://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/eacs-guidelines.html. Accessed May 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zash R, Jacobson DL, Diseko M, et al. Comparative safety of dolutegravir-based or efavirenz-based antiretroviral treatment started during pregnancy in Botswana: an observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e804–e810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triumeq [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: ViiV Healthcare; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services. Recommendations Regarding the Use of Dolutegravir in Adults and Adolescents With HIV Who Are Pregnant or of Child-Bearing Potential. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/2109/recommendations-regarding-the-use-of-dolutegravir-in-adults-and-adolescents-with-hiv-who-are-pregnant-or-of-child-bearing-potential. Accessed May 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Update of Recommendations on First- and Second-Line Antiretroviral Regimens. World Health Organization; 2019. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325892/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.15-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]