Abstract

T-box riboswitches are modular bacterial noncoding RNAs that sense and regulate amino-acid availability through direct interactions with tRNAs. Between the 5' anticodon-binding Stem I and 3' amino acid-sensing domains of most T-boxes lies the Stem II domain of unknown structure and function. Here, we report a 2.8-Å cocrystal structure of the Nocardia farcinica ileS T-box in complex with its cognate tRNAIle. The structure reveals a perpendicularly arranged ultrashort Stem I containing a K-turn and an elongated Stem II bearing an S-turn. Both stems rest against a compact pseudoknot, dock via an extended ribose zipper, and jointly create a binding groove specific to the anticodon of its cognate tRNA. Contrary to proposed distal contacts to the tRNA elbow region, Stem II locally reinforces the codon-anticodon interactions between Stem I and tRNA, achieving low-nanomolar affinity. This study illustrates how mRNA junctions can create specific binding sites for interacting RNAs of prescribed sequence and structure.

Introduction

T-box riboswitches are gene-regulatory noncoding RNAs that are pervasively present in the 5'-leader regions of certain mRNAs in most Gram-positive bacteria1-3. These versatile genetic switches sense intracellular concentration of specific amino acids and respond by modulating either the transcription or translation of essential downstream genes in amino acid metabolism. More than 1000 T-boxes have been identified and are actively pursued as attractive targets for developing RNA-targeted antibiotics4-7.

T-boxes are modular in nature and most contain three domains —a 5' Stem I domain, an intervening Stem II domain and a 3' discriminator domain (Fig. 1a). Stem I decodes the tRNA anticodon using a complementary trinucleotide termed the specifier. Most transcriptional T-boxes (T-boxes that regulate transcription) feature an elongated, C-shaped Stem I that bends and tracks the overall shape of tRNA8,9. In addition to the specifier-anticodon pairing, the distal region of most Stem I’s folds into two interdigitated pentanucleotide T-loops that jointly present a planar surface using a base triple. This base triple stacks with the characteristically flat “elbow” of the tRNA, created by the inter-loop G19-C56 base pair present in all cytosolic elongator tRNAs. Similar stacking interactions to the tRNA elbow using a pair of T-loops are also observed in the evolutionarily unrelated RNase P and the ribosome L1 stalk9-12. In transcriptional T-boxes, this conserved stacking interaction is required for sufficient affinity and association rate (kon) for tRNA binding and tRNA-mediated transcriptional readthrough3,9,13,14. In contrast, the length and architecture of Stem I’s in translational T-boxes are divergent and some feature “ultrashort” Stem I’s that lack the distal T-loops and contain the specifier in a short terminal loop6,15 (Fig. 1a). Near the base of Stem I is a Kink-turn (K-turn)16 motif that sharply bends the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) trajectory, bringing the discriminator domain into close proximity to the 3'-end of the Stem I-bound tRNA to sense aminoacylation17.

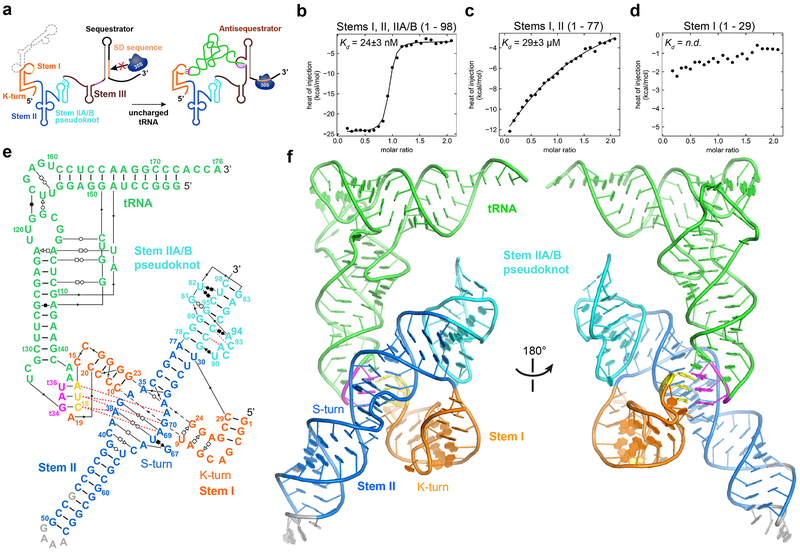

Figure 1. Overall structure of the N. farcinica ileS T-box in complex with tRNAIle.

a) Schematic of the proposed mechanism of translation regulation by the N. farcinica ileS T-box riboswitch. b-d) ITC analysis of tRNAIle binding by b) T-box1-98 (residues 1-98) consisting of Stems I, II and IIA/B, c) T-box1-77 containing Stems I and II and d) T-box1-29 Stem I only. Kd values are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 independent experiments for T-box1-98, n = 2 for T-box1-77, n = 3 for T-box1-29). e) Sequence and secondary structure of the cocrystallized ileS T-box1-98 and tRNAIle, with non-canonical base-pairing interactions indicated using the Leontis-Westhof symbols48. The 77-nt long tRNAIle is numbered (with a ‘t’ prefix) according to standard convention, with t76 as the last nucleotide. f) Structure of the ileS T-box-tRNAIle complex colored as in e). Sequence changes to facilitate crystallization are shown in gray.

The discriminator domain, consisting of the Stem III region and the antiterminator or antisequestrator element, captures the 3'-end of a cognate tRNA initially selected by Stem I, assesses its aminoacylation state, and changes conformations to control downstream gene expression17. In recently validated translation-regulating T-boxes from Actinobacteria, the discriminator either forms a “sequestrator” hairpin masking the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and blocking ribosome binding, or an “anti-sequestrator” structure that competes with the sequestrator6,15 (Fig. 1a). A highly conserved discriminator core across all known T-boxes suggest a unified mechanism of amino acid sensing and conformational switching.

In contrast to the better-understood Stem I and discriminator domains, the structure and function of the intervening Stem II domain remain enigmatic. In glycine-specific transcriptional T-boxes, the Stem II domain is replaced with a short, flexible linker. In most other T-boxes, Stem II domain is present and its secondary structure is conserved18. The Stem II domain consists of a long hairpin (Stem II) of variable length containing a presumed S-turn motif (or Loop E, or bulged-G motif)19,20 near its center, followed by a Stem IIA/B element predicted to form a pseudoknot. As the Stem II domain coexists with Stem I distal T-loops in most transcriptional T-boxes and either but not both can be absent, we hypothesize that the Stem I T-loops and the Stem II domain can functionally substitute for each other by making independent, cooperative contacts to different parts of the tRNA. A recent 4-thio-U crosslinking study using a translational T-box containing an ultrashort Stem I proposed two direct contacts between Stem II domain and the regions of tRNA near the elbow15. Specifically, the S-turn motif in Stem II cross-linked to C62 and U63 of the tRNA T-stem while the Stem IIA/B element cross-linked to G15 and G16 of the D-loop15.

In order to understand how the Stem II domain enables specific tRNA recognition by an ultrashort Stem I, we crystallized the Stem I and Stem II domains of a Nocardia farcinica ileS translational T-box riboswitch in complex with its cognate tRNAIle and solved its structure at 2.8 Å resolution. Using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), we further quantitatively characterized the thermodynamic parameters of the T-box-tRNA interaction and evaluated the impact of specific domain truncations and mutations. Together, our data reveal a surprising role of the T-box Stem II domain in locally reinforcing Stem I-tRNA interactions by organizing a unique anticodon-binding groove, latching the codon-anticodon duplex using a strategically placed S-turn, and shaping a pattern of codon and tRNA usage by the T-boxes distinct from the ribosome.

Results

Overall structure of the N. farcinica ileS T-box-tRNAIle complex

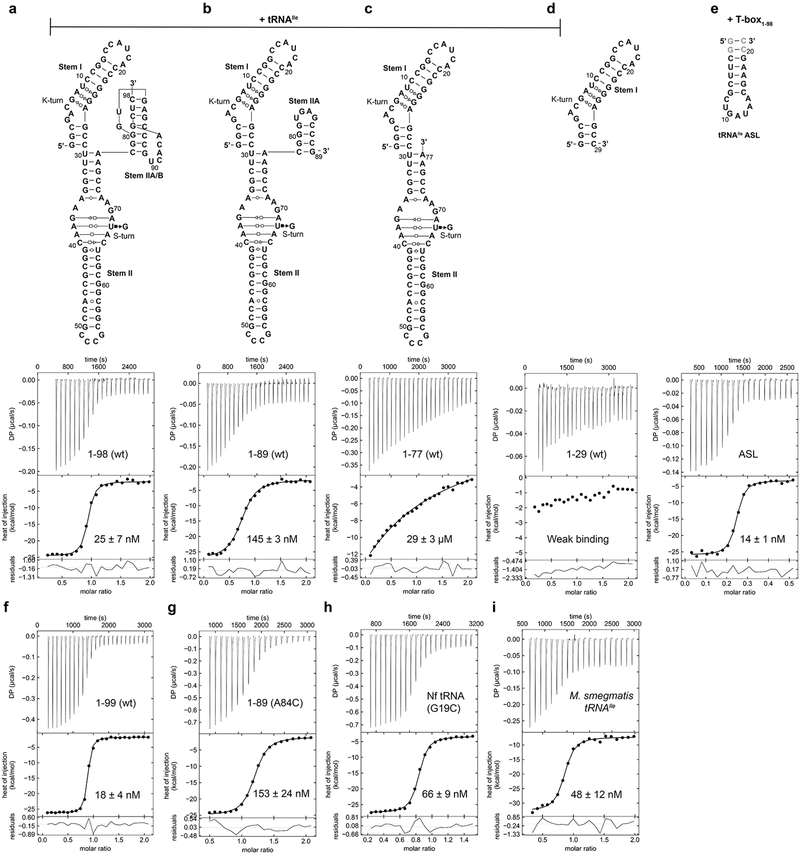

We first defined N. farcinica ileS T-box domains required for high-affinity binding to its cognate tRNAIle. ITC and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analyses showed that T-box1-98 (residues 1-98, Stem I-Stem II-Stem IIA/B) bound tRNAIle with a Kd ~25 nM (Fig. 1b; Extended Data Figs. 1-3; Supplementary Table 1), consistent with prior measurements using a filter-retention assay6. Notably, T-box1-77 (Stems I and II, without Stem IIA/B) exhibited ~1000-fold lower affinity than T-box1-98 whereas tRNA binding to T-box1-29 (Stem I alone) was barely detectable (Fig. 1c, d). Therefore, we proceeded to co-crystallize the T-box1-98-tRNAIle complex and determined its structure at 2.82 Å resolution (Extended Data Figs. 1 & 4; Table 1; Supplementary Movie 1).

Table 1.

X-ray crystallographic statistics of the ileS T-box – tRNAIle complex cocrystal.

| T-box1-98 – tRNAIle complex |

Native (6UFM) |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 |

| Space group | P2221 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 42.23 93.98 179.63 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 46.99 – 2.82 (2.92 – 2.82) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 8.57 (196.5) |

| <I>/<σ(I)>a | 15.2 (1.2) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.3 (99.4) |

| Redundancya | 13.0 (10.3) |

| CC1/2 | 0.994 (0.712) |

| CC* | 0.999 (0.912) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å)a | 46.99 – 2.82 (2.92 – 2.82) |

| No. reflectionsb | 17899 (1726) |

| Rwork/ Rfree (%)a | 19.0 (44.2) /23.1 (44.2) |

| No. atoms | 3759 |

| RNA | 3754 |

| Ion | 5 |

| Water | 0 |

| Mean B-factors (Å2) | 141.41 |

| RNA | 141.41 |

| Ligand/ion | 143.20 |

| Water | - |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.74 |

| Maximum likelihood | 0.42 |

| coordinate precision (Å) |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Values in parentheses are for the cross-validation set.

The structure reveals a perpendicularly arranged Stem I and Stem II, enabled by a sharp bend at the Stem I K-turn and joined at their bases near the Stem IIA/B pseudoknot (Fig. 1e, f). The pseudoknot extends the dsRNA trajectory of Stem II by coaxial stacking, and anchors the base of Stem I to dock with the middle section of Stem II. This architecture creates an extended binding groove for the tRNA’s anticodon stem loop (ASL). Surprisingly, we observed no contacts to the tRNA T-arm or D-loop regions as previously proposed15. Instead, Stem II uses its conserved S-turn motif to locally reinforce the anticodon-specifier duplex on the minor groove side. Remarkably, these densely populated interactions at the ASL achieve considerably higher affinity (25 nM vs 150 nM; 6 fold, Fig. 1b) than the elongated Stem I’s, in which the affinities are distributed between two distant interfaces at the anticodon and elbow9.

Recognition of the tRNA anticodon by an ultrashort Stem I

The specifier trinucleotide (AUC) in the Stem I distal loop forms three Watson-Crick pairs with the tRNA anticodon (GAU) (Fig. 2a). Similar to elongated Stem I’s (Fig. 2b), the 3-bp anticodon-specifier duplex is sandwiched by cross-strand stacking by two conserved purines — tA37 on the tRNA and A19 on the T-box (Fig. 2a)1,3,9. Thus, the basal mechanisms of anticodon recognition and duplex stabilization are shared between T-boxes harboring long and short Stem I’s (Fig. 2c).

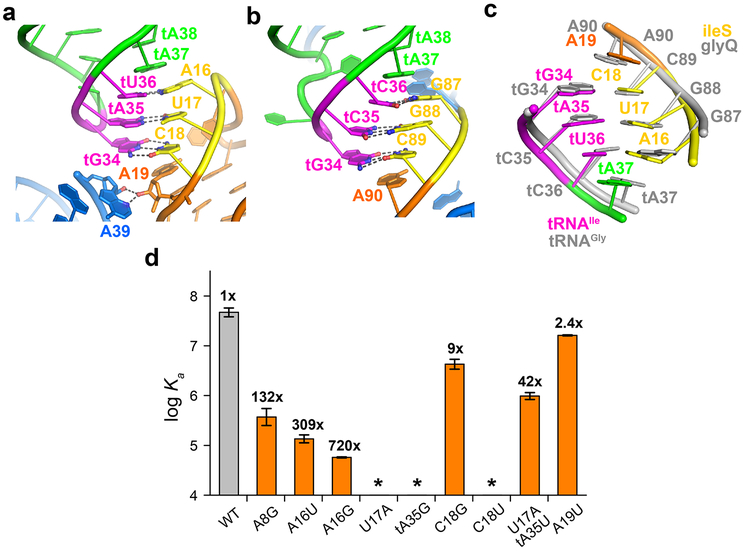

Figure 2. Recognition of tRNA anticodon by the ileS T-box riboswitch.

a) Specifier-anticodon interactions in the ileS T-box-tRNAIle complex. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. b) Specifier-anticodon interactions in the glyQ T-box riboswitch (PDB ID: 4LCK)9. c) Superposition of the Specifier-anticodon interactions in the ileS (colored as in a) and glyQ (gray) T-box riboswitches. d) Mutagenesis and ITC analysis of selected Stem I mutations in T-box1-98 (orange columns) compared to the wt T-box1-98 (gray column). The fold change in the Kd value, compared to wt T-box1-98 is shown on top of each column. Data shown are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 independent experiments for WT, n = 3 for A8G, tA35G, C18G, U17A:tA35U, n = 2 for A16U, A16G, U17A, C18U, A19U). Source data for panel d are available online.

Several distinctions also exist between the two types of Stem I’s. First, unlike the long Stem I’s which house the specifier in a bulge, ultrashort Stem I’s host it in a distal loop. At the 3'-edge of this loop, A19 uses its 2'-OH to make two hydrogen bonds to the N3 and 2'-OH of A39 of Stem II for additional stabilization. These interactions are absent from glycine T-boxes due to the absence of Stem II. Second, due to Stem I truncation, all three base edges of tA37 are exposed to the solvent and unobstructed by the T-box, thus accommodating any bulky post-transcriptional modifications here (Fig. 2a). This contrasts with the partially exposed tA37 in the case of long Stem I’s (Fig. 2b), which uses its S-turn to evade potential clashes with the modifications9. Third, this distal loop of short Stem I’s structurally resembles the tRNA ASL to which it binds, exhibiting a near symmetrical arrangement (Extended Data Fig. 5)21.

Single nucleobase substitutions of the specifier reduced tRNA binding affinities to different extents, suggesting variable specificities among the three pairing positions. Most mutations drastically reduced binding by >300-fold, except for a G×G mismatch (by C18G) which only increased the Kd by ~9-fold (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 1). It is possible that the G×G mismatch is tolerated due to enhanced stacking between G18 and its neighboring U17 and A19, or formation of a non-canonical G•G pair. Interestingly, an A19U substitution of the conserved purine that stacks with the anticodon-specifier duplex only increased the Kd by ~2.5-fold, in contrast to the loss of binding by an A90U substitution at the equivalent position in the glyQ T-box. This is consistent with the reduced cross-strand stacking observed between A19 and tG34 compared to A90 in glyQ (Fig. 2c). Compared to glyQ T-boxes which tolerated many near-cognate pairs in the anticodon-specifier duplex22, the Stem II-containing ile T-box exhibited a stronger preference for Watson-Crick pairing. This may be due to geometric requirements to bind the Stem II S-turn, or the reliance on a single binding interface due to lack of tRNA elbow contacts. Similar to the glyQ T-boxes, the central position of the anticodon-specifier duplex in the ileS T-box is the least tolerant of mismatches and near-cognate wobble base pairs22.

A conserved K-turn links the proximal regions of Stem I and Stem II via a sharp 120° turn, directing Stem II to the vicinity of the Stem I-tRNA interface to reinforce it. Disrupting the K-turn with an A8G substitution reduced tRNA binding by over ~100-fold (Fig. 2d), suggesting an essential topological role. In comparison, the K-turn in glycyl T-boxes plays a distinct geometric role in guiding the 3' discriminator domain towards the tRNA 3'-end9,23.

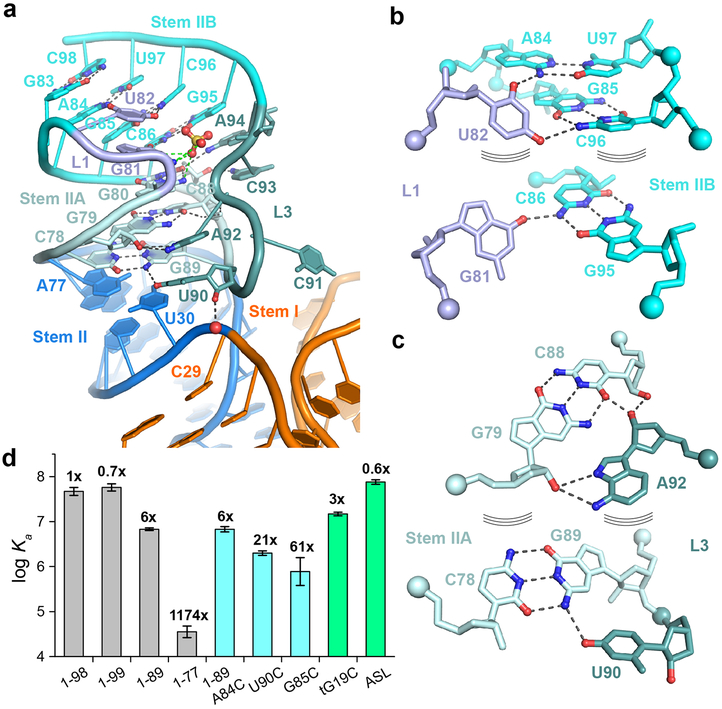

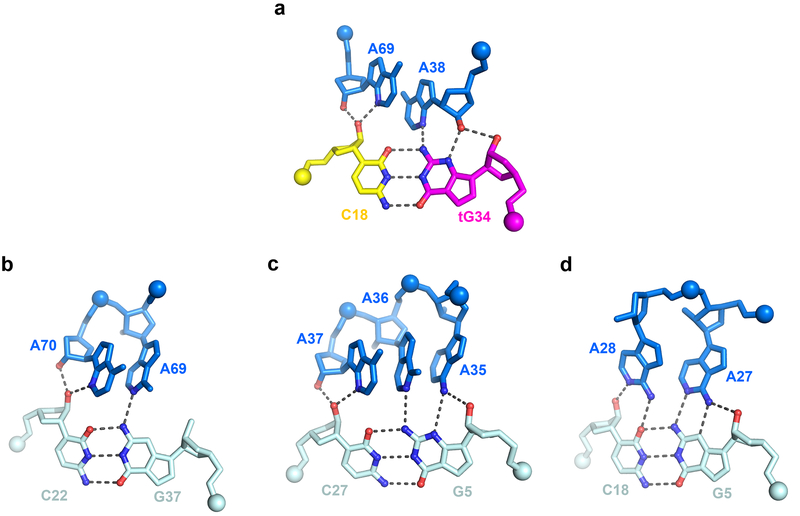

Extensive stabilization of codon-specifier duplex by the Stem II S-turn

The S-turn motif is a widespread helical motif that features two consecutive bends in the phosphate-sugar backbone resulting in a characteristic ‘S’ shape (Extended Data Figs. 4 & 6)19,20,24. The Stem II S-turn features a three-layered, extensively stacked structure consisting of a central base triple (A38•U68•bulged G67) sandwiched by a sheared G37•A69 pair on top and a parallel, symmetrical Hoogsteen-Hoogsteen A39•A66 pair below (Fig. 3a-b). The predominant utilization of Hoogsteen nucleobase edges as opposed to Watson-Crick edges in the pairing exposes the latter to the solvent. Together with the neighboring exposed sugar edges (especially the N2 and N3 groups of purines) and widened major and minor grooves, the purines within S-turns provide a distinct cluster of polar groups available for interactions with a partner RNA or protein. Within the ribosome and the Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme, S-turns are used for tertiary interactions with RNA as well as proteins such as ribosomal proteins, α-sarcin and ricin (Extended Data Fig. 6)19,20,25,26. Interestingly, despite having a nearly identical S-turn, the long Stem I is not known to use it for interactions9. In contrast, the Stem II S-turn makes numerous hydrogen bonds to the minor groove of the anticodon-specifier duplex, especially at the wobble position (tG34-C18) (Fig. 3c). Specifically, the S-turn approaches the duplex at a ~40° angle, allowing the cross-strand stacked A38 and A69 to interact simultaneously with the minor groove of a single base pair (tG34-C18). The 2'-OH groups from all four involved residues and three N3 groups of A38, A69, and tG34 are arranged in an alternating manner to make 5 hydrogen bonds across the groove (Fig. 3c-d). We term this unusual arrangement an “inclined tandem A-minor (ITAM)” motif and note that similar motifs have been observed in other RNA structures such as the TPP 27,28, SAM-II29, and preQ1-I riboswitches30 (Extended Data Fig. 7). ITAM differs from canonical A-minor interactions in that instead of using a single, approximately coplanar adenosine to span part or the entire width of a minor groove, this motif uses two or more (e.g., three in the SAM-II riboswitch) inclined, stacked adenosines in tandem (e.g., A38 and A69 in T-box Stem II) to span the same distance across the groove, thus having the potential to make more extensive interactions (Fig. 3c-d; Extended Data Fig. 7). Further, the Stem II ITAM is distinct from other examples in that the inclined, stacked adenosines come from opposite strands while most other ITAM examples use adjacent adenosines in the same strand. In effect, the Stem II S-turn uses the ITAM motif to allow the helical sections of two angled dsRNA helices — one regular and the other irregular due to the S-turn distortions — to anchor to each other via mutual minor-groove interactions (Fig. 3a-d).

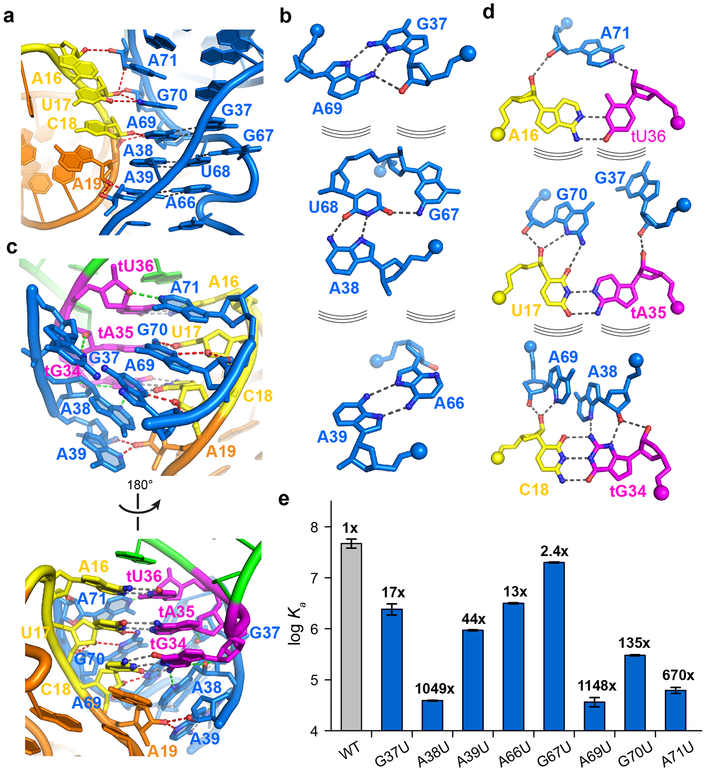

Figure 3. Stabilization of specifier-anticodon interaction by the S-turn motif.

a) The S-turn motif of Stem II showing the characteristic ‘S’ shape of the backbone bend near the bulged G67. Stem I and Stem II dock via extensive ribose-zipper interactions, shown as red dashed lines.

b) Hydrogen-bonding patterns of each of the three layers of the S-turn motif. The curved lines indicate stacking between the layers and the spheres indicate backbone phosphate atoms. c) The S-turn and neighboring residues make multiple hydrogen bonds to the specifier (red dashes) and the anticodon (green dashes) to stabilize the 3-bp anticodon-specifier helix. d) Interactions from the S-turn and adjacent residues to each layer of the 3-bp specifier-anticodon duplex. e) Mutagenesis and ITC analysis of selected Stem II mutations in T-box1-98 (blue columns) compared to the wt T-box1-98 (gray column). The fold change in the Kd value compared to wt T-box1-98 is shown on top of each column. Data shown are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 independent experiments for WT, n = 3 for G67U, A69U, A71U, n = 2 for G37U, A38U, A39U, G70U, A66U). Source data for panel e are available online.

Single uridine substitutions of S-turn residues facing Stem I or tRNA (A38, A39, A69, G70, A71) exhibited severe defects in tRNA binding (44 −1148-fold increase in Kd; Fig. 3e), in contrast to the residues facing the solvent (G37, A66, G67) which had relatively mild effects (2.4 −17-fold) . In particular, substitutions of ITAM residues A38 or A69 drastically reduced tRNA-binding affinity by ~1000 fold, highlighting the key contribution of this motif to binding (Fig. 3e, and Extended Data Fig. 3). Interestingly, a G67U mutation of the extrahelical, bulged-G residue only caused a ~2-fold increase in Kd. G67 forms only a single hydrogen bond with U68 within the S-turn as part of a GU platform31,32, and does not interact with Stem I or tRNA, explaining the observed minor effect of its substitution. The expendability of the bulged-G residue is notable as it is naturally variable, as adenosines and pyrimidines have been observed in other S-turns27,30,33.

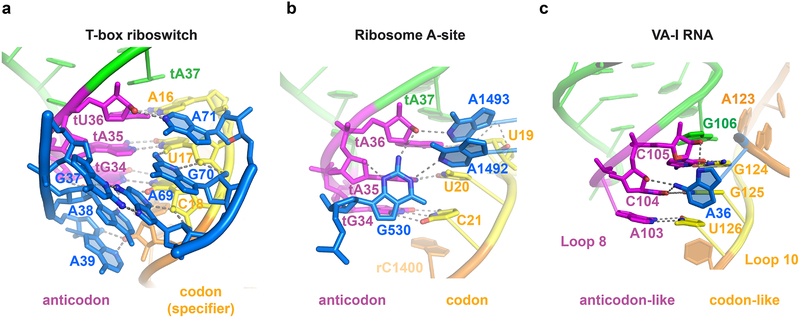

As the ITAM involves two hydrogen bonds to both the 2-amino and N3 of the tG34 nucleobase (Fig. 3d), it imposes a strong preference for a guanine at the wobble position. This in turn translates into a preference for a cytosine at the third position of the T-box codon. This unusual and nearly absolute cytosine preference (termed the “C rule”) was previously noted in several phylogenetic analyses but has remained unexplained22, as it does not correlate with either tRNA isoacceptor abundance or general codon usage4,5,34. A secondary driving force for the cytosine preference may have been the more stable G-C pair over the A-U pair. Similarly, G70 makes a base-specific interaction to the 2-carbonyl group of U17(Fig. 3d). This contact may explain the dramatic effect of the U17A substitution, and the inability to fully restore binding affinity by a compensatory tA35U substitution (still 42-fold defective, Fig. 2d). Thus, the base-specific interactions with the Stem II S-turn observed in the structure may have restricted the choices of tRNA isoacceptors and T-box codons, producing a unique pattern distinct from the codon usage by the ribosome. The manner by which the purine-rich Stem II S-turn latches the codon-anticodon duplex shares features with the ribosomal A site, where A1492, A1493, and G532 of ribosomal RNA jointly latch the codon-anticodon duplex to ensure decoding fidelity35-37, and the adenovirus Virus-Associated RNA I (VA-I) central domain, where a single adenosine (A37) stabilizes a codon-anticodon-like 3-bp pseudoknot38 (Extended Data Fig. 8). Among the three, the inclined S-turn of Stem II provides the most extensive stabilizing contacts.

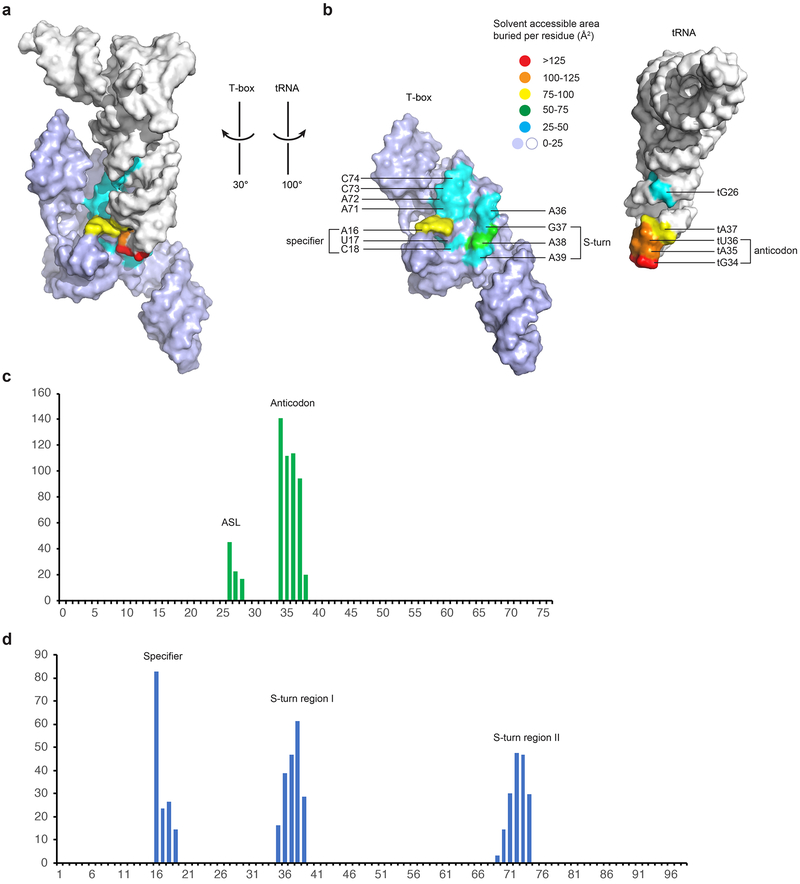

Stem I - Stem II docking forms a specific anticodon-binding groove

Stem I and II interact via an unusually long ribose zipper formed between the backbone 2'-OHs of the Stem I specifier region (A16, U17, C18 and A19) and the 2'-OHs and N3 of the Stem II S-turn and surrounding region (A71, G70 and A69, then crossing over to the opposite strand to A38 and A39) (Fig. 3a, red dashed lines). This ribose zipper flanks the ITAM interaction from A38 and A69 and involves multiple bifurcated hydrogen bonds to the 2'-OHs and N3 of the Stem II purines. These backbone interactions create an extended groove between the two stems to capture the tRNA anticodon (Fig. 4a-b; Extended Data Fig. 9). The predominant use of backbone as opposed to nucleobase contacts allows the use of different anticodon and specifier pairs with this binding groove. Notably, the helical, stacked A69-G70-A71 all-purine trinucleotide appears to use these backbone contacts to guide the specifier into a helical, stacked conformation poised to receive the incoming anticodon (Fig. 3d). Substituting any of the three purines with a uridine reduced tRNA binding by 100-1000-fold, suggesting their critical importance (Fig. 3e).

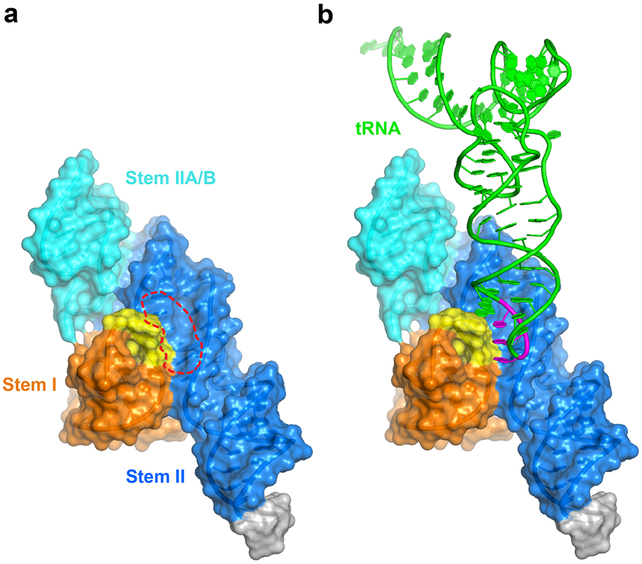

Figure 4. tRNA recognition by the T-box anticodon-binding groove.

a) Surface representation of the T-box riboswitch showing the anticodon-binding groove (red dashed oval) formed between Stem I and Stem II. tRNA is omitted for clarity b) same view as a) with tRNA bound. See also Extended Data Fig. 9 for detailed surface burial analysis.

Stem IIA/B pseudoknot is an essential organizational hub

A compact H-type (or hairpin-type) pseudoknot immediately follows Stem II in most T-boxes and contains two short stacked helices termed Stem IIA (3 bp) and IIB (4 bp) (Fig. 5a). The latter is formed by base pairing between the 3' region of the Stem IIA loop and single-stranded sequences at the 3'-end of the Stem II domain. A leading 2-nt L1 loop and a trailing 5-nt L3 loop (L2 = 0) make extensive interactions with the major and minor grooves of Stem IIB and IIA helices, respectively, producing the most compact pseudoknot visualized so far in the PseudoBase39 — spanning only 21 nt.

Figure 5. Stem IIA/B forms a compact pseudoknot to position Stems I and II.

a) Structure of the Stem IIA/B pseudoknot. The base-pairing interactions within Stems IIA and IIB and key tertiary interactions with loops L1 and L3 are shown. A single hydrogen bond between the 2'-OH of U90 in L3 and the U30 OP2 (red sphere) is indicated. A pseudoknot-bound sulfate ion is shown. b) Tertiary interactions of loop L1 residues (light blue) with Stem IIB (cyan). c) L3 (teal) interactions with Stem IIA (light cyan). d) ITC analysis of T-box length variants (gray), pseudoknot mutants (cyan), tRNA tG19C mutant and ASL (green). The fold change in Kd value compared to wt T-box1-98 is shown on top of each column. Data shown are mean ± s.d. (n = 4 independent experiments for ASL, 1-98, n = 3 for 1-99, 1-89, U90C, n = 2 for 1-77, 1-89 UGCG, G85C, tG19C). Source data for panel d are available online.

On the major groove side, G81 from L1 forms a base triple with the closing pair of Stem IIB (C86-G95) and stacks with U82 (Fig. 5b). Unusually, U82 uses both its 2- and 4- carbonyls of its 45°-inclined nucleobase to construct two tandem base triples with two consecutive base pairs A84-U97 and G85-C96, respectively. On the minor groove side, another highly conserved uridine U90 from L3 forms a second GU platform (the first being G67•U68 in the S-turn base triple)31,32 with G89, as part of a base triple involving the conserved C78-G89 pair at the base of Stem IIA (Fig. 5c). U90 also provides a flexible backbone bend. This base triple interfaces with both Stem I and Stem II and appears to play a key role in orienting both stems and facilitating their docking. A conservative U90C mutation reduced tRNA binding affinity by ~21-fold (Fig. 5d), likely due to the loss of the GU platform and base triple, consistent with a strong preference for uridine here6. While the C78-G89 pair portion of the triple stacks with the base of Stem II, the 2'-OH of U90 bonds with a phosphate oxygen between C29 and U30, helping anchor Stem I (Fig. 5a). This interfacial base triple is backed by another triple-like structure consisting of the G79-C88 pair and A92 which form robust A-minor interactions (Fig. 5c). C91 flips out to facilitate the sharp backbone bend and allows A92 to stack with U90. The sequence in the 3' strand of Stem IIA and 5' half of L3 (87CCGUCA92) forms the second most conserved region of the T-box termed the “F-box”, only after the discriminator bulge sequence that binds the tRNA 3'-end2,18. The base-specific contacts of the F-box to generate and reinforce the pseudoknot rationalize its unique conservation pattern and functional importance. Finally, C93 and A94 at the 3' edge of L3 stack against Stem IIB and bond with the 2'-OH and 2-carbonyl of C87, respectively, bolstering Stem IIB (Fig. 5a). Altogether, six out of the seven Watson-Crick pairs in the Stem IIA/B helix are reinforced with five base triples and one A-minor interaction, creating a robust three-stranded structure.

Previous crosslinking analyses suggested a direct contact between tRNA D-loop and the Stem IIA/B pseudoknot15. Our structure reveals that the pseudoknot is located 30-40 Å away from the D-loop on the opposite side of the tRNA. To ascertain that the pseudoknot does not directly contact tRNA, we measured binding of an isolated tRNAIle ASL to the T-box. Remarkably, the ASL alone binds with very high affinity (~14 nM, Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 2) comparable to the full tRNA (~25 nM). Similarly, a tG19C mutation that disrupts the tG19-tC56 tertiary pair that forms the tRNA elbow still binds with a robust ~66 nM affinity (2.8-fold effect). These findings strongly suggest that all the binding determinants present on tRNAIle to bind the Stem I and II domains are located within the ASL (Extended Data Fig. 9). Consistent with previous reports that pseudoknot mutations reduced tRNA crosslinking and abolished T-box responses in vivo15,18, we observed that pseudoknot disruptions drastically reduced tRNA binding. A complete deletion of the pseudoknot (T-box1-77) nearly abolished tRNA binding with a ~1000-fold reduction in affinity (Figs. 1c & 5d; Extended Data Figs. 2-3) while a single G85C substitution reduced affinity by ~60-fold. In comparison, a partial deletion of L3 and Stem IIB leaving the Stem IIA hairpin loop intact exhibited only a ~5-fold defect. We reason that the base of Stem IIA presumably can still stack with Stem II and guide the trajectory of Stem I, albeit more weakly than the pseudoknot base triple. Interestingly, tRNA binding reciprocally stabilizes the pseudoknot, restricting the backbone flexibility of U90 of the base triple and reducing its chemical modification15. In addition, or as an alternative to a role in Stem II stabilization, the pseudoknot may act to redirect the base of Stem I away and block it from stacking with the base of Stem II, which would prevent their docking and tRNA binding. This notion is consistent with the dramatic effect of the pseudoknot deletion (Fig. 5d) and the functional sufficiency of Stem IIA. Taken together, our data show that the Stem IIA/B pseudoknot is an essential structural element that does not directly bind tRNA, but rather acts as a geometric hub to organize and orient Stem I and Stem II.

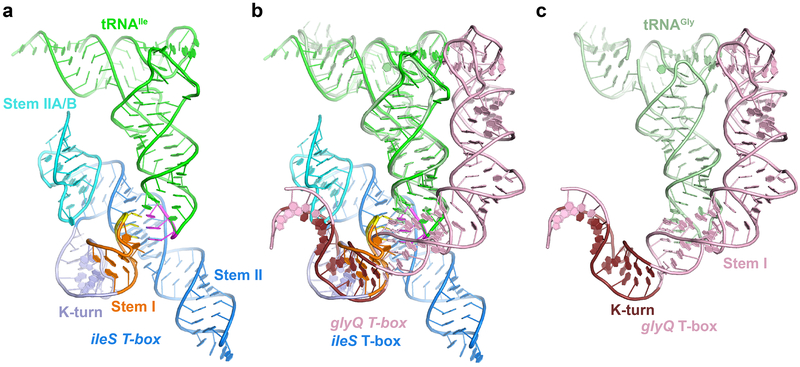

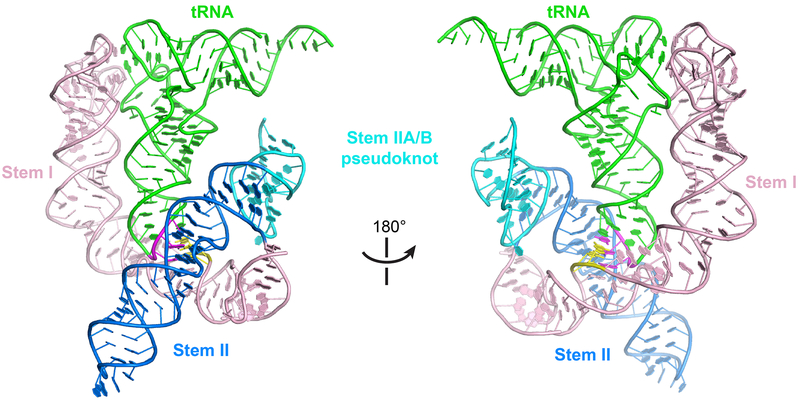

Stem II structure and interactions are compatible with a canonical, elongated Stem I

Lastly, we examined whether the structure and interactions of the Stem II domain within a translational T-box would be similar to or different from the same domain in a feature-complete transcriptional T-box containing a canonical, elongated Stem I. When we superimposed the two tRNAs from the N. farcinica ileS T-box-tRNAIle complex (Fig. 6a) and Oceanobacillus iheyensis glyQ Stem I-tRNAGly complex9 (Fig. 6c), the two Stem I’s align well, even placing the K-turns in approximately the same location (Fig. 6b). The Stem II and IIA/B pseudoknot do not clash with the elongated Stem I, as they engage the tRNA on opposite sides, and together embrace the tRNA near the ASL. The distal region of the long Stem I can be viewed as a seamless insertion into the distal loop of the ultrashort Stem I. This allowed facile modeling of a canonical, most common T-box riboswitch containing both the long Stem I and the Stem II domain, such as the first discovered B. subtilis tyrS T-box (Extended Data Fig. 10). These findings corroborate the modular nature of the T-box riboswitch, hint at the evolution of different Stem I’s, and suggest a level of plug-and-play for RNA structural modules.

Figure 6. Structural comparison with T-boxes containing canonical long Stem I.

a) Cocrystal structure of N. farcinica ileS T-box1-98 bound to tRNAIle. The K-turn motif in Stem I is in light blue. b) Superposition of cocrystal structures of the ileS T-box1-98-tRNAIle in a) and glyQ Stem I-tRNAGly complexes in c). The structures are aligned using tRNAs from both models. The superposition shows that the K-turn motifs in both the structures occupy similar locations and the long Stem I of glyQ T-box is compatible with the Stem II and Stem IIA/B pseudoknot elements of ileS T-box, providing a plausible model for canonical T-boxes containing all these elements c) Cocrystal structure of the O. iheyensis glyQ T-box Stem I bound to tRNAGly (PDB ID: 4LCK9). K-turn in the proximal region of Stem I is shown in dark brown.

Discussion

Our structural and biochemical analyses portray how an ultrashort T-box Stem I collaborates with a perpendicularly arranged Stem II to jointly sculpt a high-affinity binding site for the anticodon of specific tRNAs. The inclined Stem II makes full use of the numerous exposed purine base edges and backbone 2'-OHs of its S-turn region to locally reinforce the otherwise weak anticodon-specifier duplex. The Stem IIA/B pseudoknot, in conjunction with the Stem I K-turn, positions and orients Stem I and II so that they dock via an extended ribose zipper to form the anticodon-binding groove.

As the Stem II domain is present in nearly all but the glycine-specific transcriptional T-boxes, it represents an integral component of the T-box riboswitch. Mutations in this phylogenetically conserved region strongly compromised tRNA-mediated transcription readthrough in vivo, suggesting its functional importance18. Our data demonstrate that the Stem II domain enhances tRNA binding affinity compared to Stem I alone by >1000 fold. Given this importance of the Stem II domain, why is it dispensable in glycyl T-boxes? Glycyl T-boxes recognize tRNAGly which contains well-stacked GCC anticodon that forms stable pairs with its cognate GGC specifier. Thus, it is likely unnecessary to pre-organize the specifier trinucleotide or to locally bolster the already-stable duplex. This explanation is congruent with the primary function of the Stem II domain being to locally reinforce weaker, A-U-rich anticodon-specifier duplexes. Further, the manner by which the Stem II S-turn latches the duplex constrains the choices of T-box codons and tRNA isoacceptors, shaping a distinct pattern of codon usage from that on the ribosome.

A second question is why certain translation-regulatory T-boxes can operate without the highly conserved Stem I distal T-loops that stack with the tRNA elbow? This interaction plays essential roles in transcriptional T-boxes in ensuring requisite tRNA affinity, binding rates, and complex stability3,9,13,14 . All known transcription-regulating riboswitches, including the T-boxes, have a finite time window (~ a few seconds) to race towards co-transcriptional RNA folding and ligand-binding before the elongating RNAP reaches the terminator region40-42. By contrast, translation-regulating riboswitches exemplified by certain purine and SAM riboswitches interconvert between two conformers that are in equilibrium depending on ligand concentrations43,44. Thus, transcriptional T-boxes may require a faster kon to allow more time for tRNA to bind before the RNAP reaches the decision point, whereas translational T-boxes need to continuously monitor tRNA aminoacylation in binding equilibria. In support, the Stem I distal T-loops contribute ~2-20 fold to kon of tRNAs based on single-molecule measurements13,14. Additionally or alternatively, the distal T-loops of Stem I may be required to stabilize the tRNA-discriminator interaction17. By stacking with the tRNA elbow, the T-loops add six layers to the continuous stack with the discriminator thereby allowing its aggregate stability to transiently overcome the terminator. Consistent with this notion, a deletion of the T-loops abrogated the extremely long-lived T-box-tRNA complexes observed in single-molecule experiments13. For the translational T-boxes, over-stabilization of one of the two conformers can prevent interconversion needed to maintain structural fluidity and responsiveness of the switch. Taken together, the architectural differences in the translational versus transcriptional T-boxes may have been driven by the specific kinetic and thermodynamic requirements dictated by their distinct regulatory needs43.

Intriguingly, the compact ASL-binding groove formed by Stem I and II achieves significantly higher affinities than the elongated Stem I (25 nM vs 150 nM) despite burying much less solvent-accessible surface areas (ASA; 539 Å2 vs 802 Å2; Extended Data Fig. 9)9. These translate into a nearly two-fold difference in binding efficiencies (BEs, as defined by ΔG0/ASA) of 19 and 11 cal mol−1 Å−2, for the ultrashort and elongated Stem I’s, respectively. Notably, the remarkable binding efficiency of this groove parallels some of the highest-affinity protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and approaches the upper limit of ~20 cal mol−1Å−2 estimated for PPIs45. Further examination of the thermodynamic parameters show that the ultrashort Stem I-Stem II achieves higher binding energies not primarily through making more favorable contacts (i.e., better enthalpy), but by reducing the entropic cost of binding (-TΔS = 13.3 kcal mol−1 for ileS T-box vs 15.9 kcal mol−1 for the glyQS T-box9, Supplementary Table 1). This finding suggests that the docking of Stem I and Stem II aided by the IIA/B pseudoknot likely pre-organizes the binding groove and stacks the specifier nucleotides in anticipation of the anticodon of the incoming tRNA.

The structural and functional elucidations of the ultrashort T-box Stem I and enigmatic Stem II domain complete our understanding of the T-box structural framework. As the N. farcinica T-box closely resembles those from important human pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the structural and biochemical insights obtained here can inform the development of novel antimicrobials against mycobacteria. Our ileS T-box-tRNAIle complex structure exemplifies how a linear mRNA can utilize strategically positioned geometric devices such as the K-turn and a pseudoknot together with interaction modules such as the S-turn and a ribose zipper to self-assemble into a scaffold that harbors functional modules such as a specific tRNA-binding groove. Similar organizational principles and strategies may drive RNA and ribonucleoprotein assembly into RNA suprastructures such as RNA genomes, condensates or granules46,47.

Methods:

RNA preparation.

The ileS T-box riboswitch RNAs and tRNAs were produced by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase using PCR products as templates38. The RNAs were purified by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide (29:1 acrylamide: bisacrylamide), 8 M Urea TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) gels, electroeluted, washed once with 1 M KCl, desalted by ultrafiltration, washed four times with DEPC-treated H2O, and stored at −80°C until use. The T-box riboswitch-tRNA complexes were prepared by folding them together with tRNA in excess, by heating at 90 °C for 3 min, followed by snap-cooling in a folding buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA. 10 mM MgCl2 was added to the buffer upon cooling and the samples were incubated on ice for 20 min. The RNA complex was purified using size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column in the same buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2. Peak fractions containing the complex were pooled and concentrated to 6-8 mg/mL. For crystallization, unmodified tRNAIle from Mycobacterium smegmatis which is nearly identical to the N. farcinica tRNAIle and only differs at a single A57G substitution yielded crystals, which were used for structure determination. The two tRNAs exhibited comparable Kd values for binding to the wt T-box1-98 (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Conformational homogeneity of the RNAs and binding between the T-box RNAs and tRNA was assessed using native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in Tris-HEPES-EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2 (Extended Data Fig. 1). T-box RNAs and tRNA were co-folded in the 1x folding buffer by heating at 90 °C, snap-cooling together, followed by addition of 10 mM MgCl2 and incubation on ice for 20 min. The RNAs were analyzed on 10 % non-denaturing gel at 20 W for 4 hrs at room temperature. The gels were stained with GelRed and imaged on a GE ImageQuant LAS 4000 imager.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC).

RNAs were folded as described above by heating at 90 °C for 3 min, followed by snap-cooling over 2 min and addition of 10 mM MgCl2. The folded RNAs were incubated on ice for 15 min, followed by exchange into a buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM MgCl2 using ultrafiltration. For each measurement, ITC was done at least in duplicates at 20 °C with 5 - 20 μM T-box RNA in the cell and 50 – 200 μM tRNA in the syringe using a MicroCal iTC200 microcalorimeter (GE). ITC measurements for binding between T-box and tRNA anticodon stem loop (ASL) were done with 5-10 μM ASL in the cell and 50-100 μM T-box in the syringe. The 5-bp wt ASL was extended by two G-C base-pairs for stabilization (Extended Data Fig. 2) The raw ITC data were integrated using NITPIC and fit with SEDPHAT49 to obtain the dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Cocrystallization and diffraction data collection.

To facilitate crystallization, the CCCG Stem II loop in wt T-box1-98 (Extended Data Fig. 2) was replaced with a GAAA tetraloop along with introducing a single A47G substitution. For crystallization, the purified N. farcinica ileS T-box riboswitch-tRNA complex was supplemented with 1 mM spermine, 0.1 – 0.2 % (w/v, final) of low-melting-point (LM) agarose and held at 37 °C. The RNA solution was mixed 1:1 with a reservoir solution consisting of 0.1 M Bis-Tris, pH 6.5, 0.2 M Li2SO4, 20-25 % (w/v) PEG 3350, and crystallized at 21°C by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Thick rectangular prism-shaped crystals grew in 1-2 weeks to maximum dimensions of 300 × 200 × 50 μm3 (Extended Data Fig. 1). The drops containing ~0.1 - 0.2% LM agarose had a viscous gel-like consistency from which crystals were directly harvested. The crystals were cryo-protected in a synthetic mother liquor containing 25% (v/v) PEG 3350 and 20% ethylene glycol before vitrification in liquid nitrogen. For de novo phasing with Ir(III), crystals (in agarose) were soaked in a synthetic mother liquor supplemented with 20% ethylene glycol and 10 mM Ir(III) Hexammine for 15 hrs before vitrification in liquid nitrogen. Single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) data were collected at 1.0 Å near the Iridium L2 edge (0.9687 Å) at the SER-CAT beamline ID-22 at the Advanced Photon Source (APS). Crystals exhibit the symmetry of space group P2221. Unit cell dimensions are in Table 1.

Crystal structure determination and refinement.

A total of 14 Ir sites were identified by ShelxD and Phenix.HySS50 from a single 3.05 Å Ir-SAD dataset, which generated an initial electron density map with a mean overall figure of merit (FOM) of 0.298. These weak phases were improved by molecular placement of a tRNAGly (PDB ID: 4LCK) using PHASER51 followed by improved Ir substructure identification and phasing using the MR-SAD pipeline of Phenix.Autosol, producing a figure of merit (FOM) of 0.527. RNA helices and some individual nucleotides were clearly visible in the resulting electron density map. Model building was performed using Coot52 and iterative MR-SAD was used to improve the maps using the evolving model. A near-complete model of the T-box-tRNA complex was built and refined using Phenix.Refine53. The refined structure with Ir atoms removed was located in a native 2.82 Å dataset using PHASER (Translational Function Z (TFZ) score = 39.1; Log-likelihood Gain (LLG) = 2051), manually adjusted and rebuilt using Coot, and refined using Phenix.Refine. The model was then corrected by ERRASER54 and further refined. The refinement statistics for the model are summarized in Table 1. Solvent accessibility analysis was performed using StrucTools with default parameters and a 1.4 Å probe size.

Data Availability:

Atomic coordinates and structure factor amplitudes for the RNA have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank under accession code 6UFM [https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6UFM]. Source data for figure 2d, 3e and 5d are available online. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or available upon request.

Extended Data

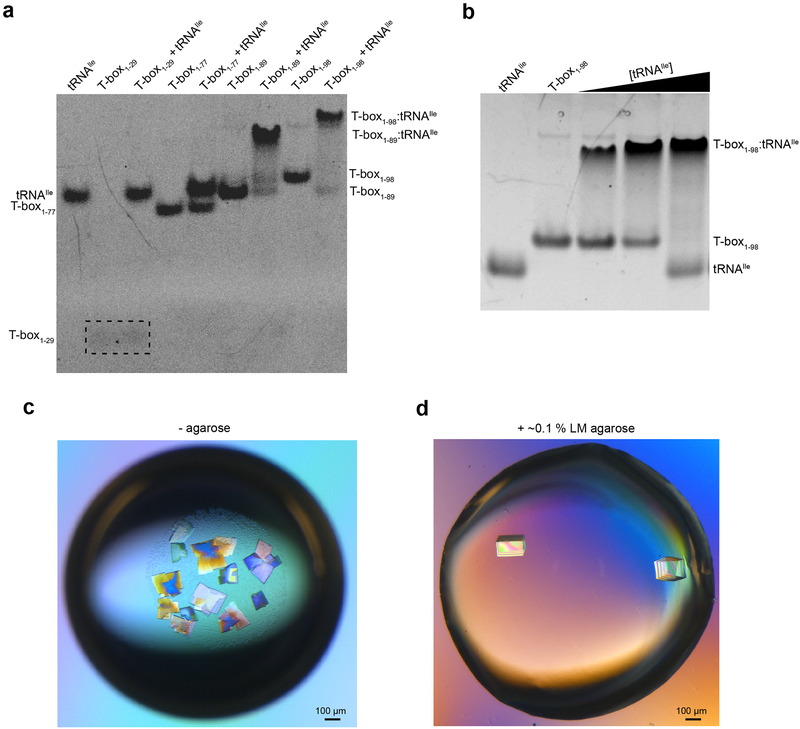

Extended Data Fig. 1. Binding of tRNAIle by the N. farcinica ileS T-box riboswitch and effect of agarose on crystal morphology.

a, Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using 10% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel showing binding of T-box length variants to tRNAIle. T-box1-29 (Stem I) bands were poorly stained by GelRed and are indicated by the dashed box. b, EMSA titration showing the binding of tRNAIle by N. farcinica ileS T-box1-98. Lanes 1-5 (left-right): 0:1, 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:1 and 1:2 mixing ratios of T-box1-98:tRNAIle. 10 μM of T-box1-98 was used for the assay. c, Crystals grown in the absence of agarose appear as thin plates with parasitic growth from the corners. Crystals were grown at 21 °C by vapor diffusion by mixing an equal volume of reservoir solution containing 20% PEG 3350, 0.1 M Bis-Tris (HCl), pH 6.5 and 200 mM Li2SO4. d, Crystals grown under similar conditions as in c), but in the presence of ~0.1 % low-melting-point agarose. In the presence of agarose, crystals grew as thick rectangular prisms with sharp edges, and exhibited improved diffraction properties. Scale bar, ~100 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis of tRNAIle binding by the ileS T-box riboswitch length variants.

a-d, Representative ITC isotherms for N. farcinica wt tRNAIle binding to (a) T-box1-98, (b) T-box1-89, (c) T-box1-77, and (d) T-box1-29. e, ITC isotherm of tRNAIle anticodon stem loop (ASL) binding to T-box1-98 (wt). f-g, ITC isotherms for N. farcinica wt tRNAIle binding to (f) T-box1-99 (with an extra 3'-G), and (g) T-box1-89 A84C mutant. h-i, ITC isotherms of h) tRNAIle G19C mutant and i) M. smegmatis tRNAIle binding to T-box1-98 (wt). The construct names and the Kd values (mean ± s.d., n = 4 for a, e; n = 3 for b, d, f; n = 2 for c, g, h, i) are reported in the top and bottom panels of the ITC isotherms.

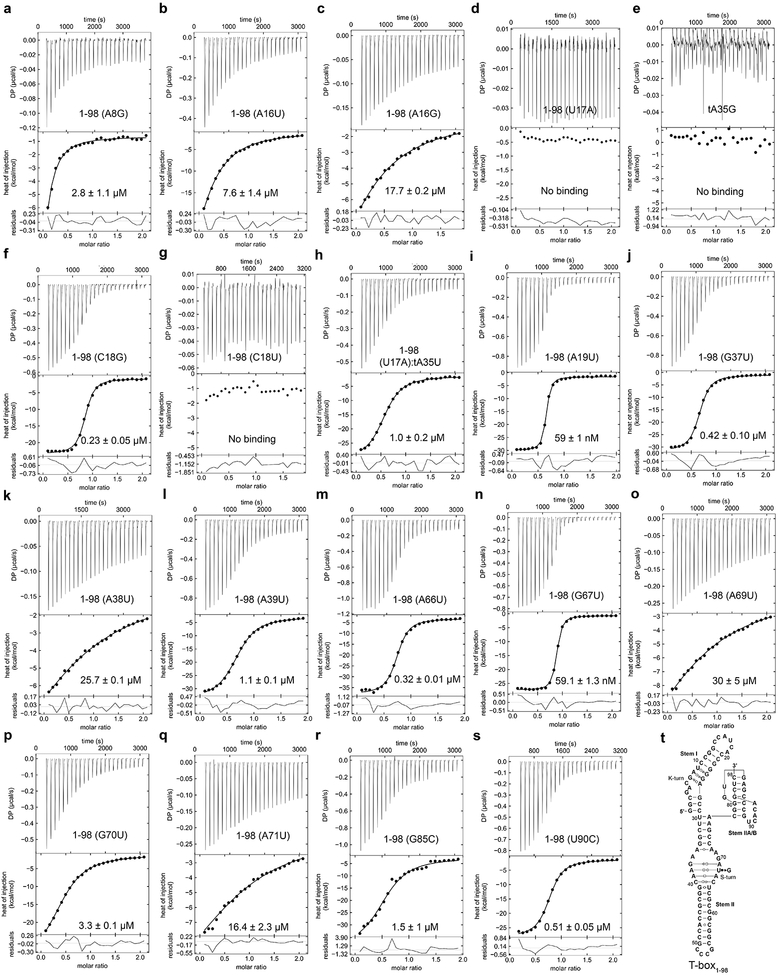

Extended Data Fig. 3. ITC analysis of the effects of single nucleobase substitutions on the ileS T-box and tRNAIle.

a-d, Representative ITC isotherms for wt tRNAIle binding by T-box1-98 Stem I mutants (a) A8G, (b) A16U, (c) A16G, (d) U17A, (d) C18G. e, T-box1-98 binding to tRNAIle tA35G mutant. f-g, ITC isotherms for wt tRNAIle binding by T-box1-98 Stem I mutants (f) C18G and (g) C18U. h, T-box1-98 U17A mutant binding to tRNAIle tA35U mutant. i) ITC isotherms for wt tRNAIle binding by T-box1-98 Stem I mutant A19U. j-s, tRNAIle binding to T-box1-98 Stem II mutants (j) G37U, (k) A38U, (l) A39U, (m) A66U, (n) G67U, (o) A69U, (p) G70U, (q) A71U, (r) G85C and (s) U90C. (t) Sequence and secondary structure of T-box1-98 for reference. The construct names and the Kd values (mean ± s.d., n = 3 for a, f, h, n, o, q, s; n = 2 for b, c, d, e, g, i, j, k, l, m, p, r) are reported in the top and bottom panels of the ITC isotherms.

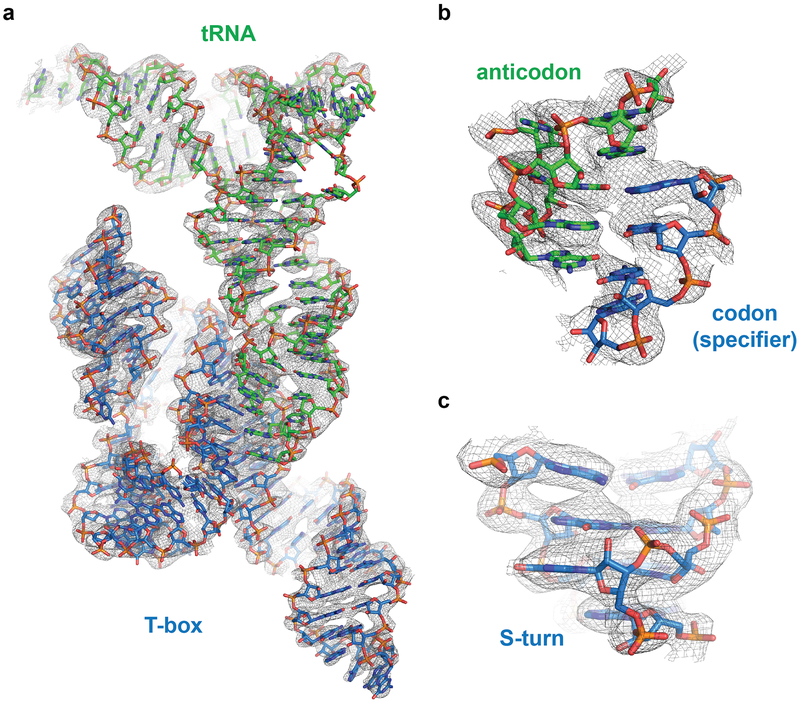

Extended Data Fig. 4. Representative X-ray crystallographic electron density maps.

a, Composite simulated anneal-omit 2|Fo|-|Fc| electron density calculated using the final model (1.0 s.d.) superimposed with the final refined model. b-c, Portions of the map showing the tRNA anticodon - T-box specifier duplex region (b) and the characteristic “S”-like backbone bend of the Stem II S-turn (c).

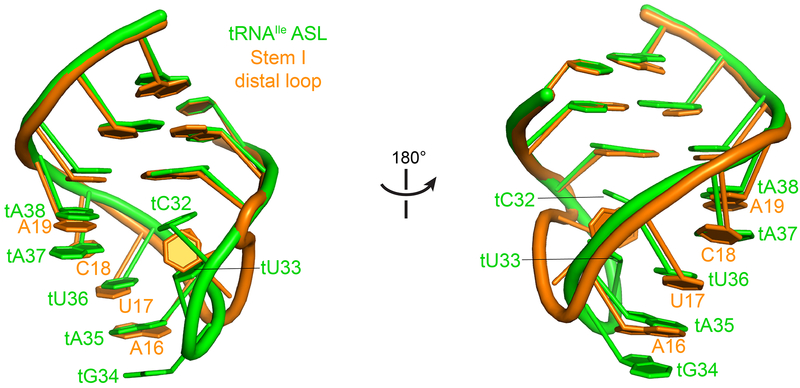

Extended Data Fig. 5. Similarity between ileS T-box Stem I distal loop and tRNAIle anticodon stem-loop (ASL).

Superposition of the ileS Stem I distal loop (orange) with tRNAIle ASL (green) showing structural similarities.

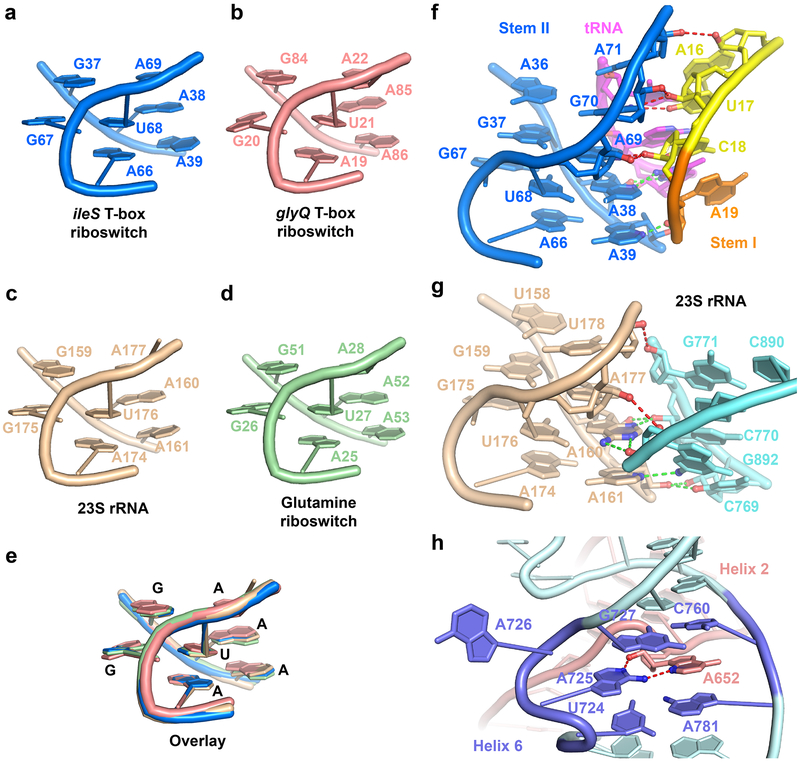

Extended Data Fig. 6. Comparison of S-turn structures and S-turn-mediated RNA-RNA interactions.

a-d, The S-turn (or loop E) motif from a) N. farcinica ileS T-box riboswitch structure, b) glyQ T-box Stem I from Oceanobacillus iheyensis (PDB ID: 4lck)1 c) 23S rRNA from the Haloarcula marismortui large ribosomal subunit (PDB ID: 4v9f)2, and d) glutamine riboswitch (PDB ID: 5ddp)3. e, Overlay of the S-turn structures in a-d. f, Stabilization of codon-anticodon helix by the Stem II S-turn in ileS T-box riboswitch. g, Interactions between an S-turn and a neighboring helix in 23S rRNA from H. marismortui. h, Interactions between an atypical S-turn motif in helix 6 of the Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme (PDB ID: 4r4v)4 and A652 of helix 2. Red and green dashes represent H-bonds involving nucleotides in the backbone-turn-containing strand and the opposite strand, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Examples of the recurring inclined tandem A-minor (ITAM) motifs in RNA structures.

a, The inclined tandem A-minor (ITAM) motif observed in the ileS T-box-tRNAIle structure. b-d, Similar ITAM motifs observed in the b) TPP riboswitch (PDB ID: 2gdi)5, c) SAM-II riboswitch (PDB ID: 2qwy)6 and d) preQ1-I riboswitch (PDB ID: 3fu2)7 crystal structures. For comparison, the motifs shown in b-d are formed by adjacent adenosines on the same strand, whereas the ITAM motif in a) uses cross-strand stacked adenosines from opposite strands. This configuration allows both the ribose and the nucleobases from both adenosines to contact the C-G base pair. The inclined adenosine motif in c) is unusual in that three adjacent, stacked adenosines span the width of a single C-G base pair and form multiple contacts with it. The motif in d) (also termed the A-amino kissing motif) involves the Watson-Crick edges of the adenosines and does not involve interactions with the ribose. These interactions are formed by L3 loop adenosines of the preQ1-I riboswitch and are common in many other H-type pseudoknots.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Three different strategies to stabilize the codon-anticodon duplex.

a, The minor groove side of the N. farcinica ileS T-box Stem II S-turn interacts extensively with the minor groove of the anticodon-specifier duplex. In particular, the A38-A69 inclined tandem A-minor (ITAM) motif stabilizes the C18-tG34 base pair. G70 and A71 stack with the top layer of the S-turn (G37•A69) and stabilize the U17-tA35 and A16-tU36 pairs, respectively (see also Fig. 3d). b, The conserved A1492 and A1493 of ribosomal RNA in the ribosome A-site interact with the codon-anticodon duplex via tandem, stacked A-minor interactions (similar to G70 and A71 in panel a) in conjunction with the G530 latch (similar to A38 and A69 in panel a) to ensure decoding fidelity8-11. c, Similarly, in the adenovirus virus-associated RNA I (VA-I RNA), A36 stabilizes a 3-bp pseudoknot formed between residues 103-105 in Loop 8 (5'-ACC-3', anticodon-like) and residues 124-126 (5'-GGU-3', codon-like) of Loop 10, through extensive A-minor interactions between A36 and the minor groove12.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Intermolecular interface of the N. farcinica T-box -tRNAIle complex.

a, Solvent-accessible surface colored according to area buried from light blue or white (no burial) to red (>125 Å2 per residue). b, Open-book view of the binding interface. c and d, Plots of solvent-accessible surface area buried per residue (Å2) on the tRNA (c) and T-box (d).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Structural model of a canonical, feature-complete T-box riboswitch Stem I and II domains in complex with its cognate tRNA.

Model of a canonical, feature-complete T-box riboswitch, such as the originally described B. subtilis tyrS T-box containing a long Stem I (salmon), Stem II (marine) and Stem IIA/B pseudoknot (cyan) elements bound to its cognate tRNA (green). The composite structural model is derived by combining the cocrystal structures of the ileS T-box riboswitch bound to tRNAIle and the cocrystal structure of the Oceanobacillus iheyensis glyQ T-box Stem I bound to tRNAGly (PDB: 4LCK)1. tRNAs from both structures were superimposed as shown in Fig. 6b. The distal loop of the ultrashort Stem I from the ileS T-box was then replaced with the long, canonical Stem I from the glyQ T-box.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Botos for computational support, G. Piszczek and D. Wu for support in biophysical analyses, F. Dyda for suggesting the use of zero-dose correction, and S. Li, C. Bou-Nader, J.M. Gordon, C. Stathopoulos, and A. Ferré-D’Amaré for discussions. Data were collected at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source of the Argonne National Laboratory, supported by the U. S. Department of Energy under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. This work was supported by the intramural research program of NIDDK, NIH, a NIH Deputy Director for Intramural Research (DDIR) Innovation Award and a DDIR Challenge Award to J.Z.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Zhang J & Ferre-D'Amare AR Structure and mechanism of the T-box riboswitches. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 6, 419–33 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy FJ & Henkin TM tRNA as a positive regulator of transcription antitermination in B. subtilis. Cell 74, 475–482 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suddala KC & Zhang J An evolving tale of two interacting RNAs-themes and variations of the T-box riboswitch mechanism. IUBMB Life 71, 1167–1180 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Lyubetsky VA & Gelfand MS Comparative genomic analysis of T-box regulatory systems in bacteria. RNA 14, 717–735 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez-Preciado A, Henkin TM, Grundy FJ, Yanofsky C & Merino E Biochemical features and functional implications of the RNA-based T-box regulatory mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73, 36–61 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherwood AV, Grundy FJ & Henkin TM T box riboswitches in Actinobacteria: translational regulation via novel tRNA interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 1113–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frohlich KM et al. Discovery of small molecule antibiotics against a unique tRNA-mediated regulation of transcription in Gram-positive bacteria. ChemMedChem (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigg JC & Ke A Structural Determinants for Geometry and Information Decoding of tRNA by T Box Leader RNA. Structure 21, 2025–32 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J & Ferré-D'Amaré AR Co-crystal structure of a T-box riboswitch stem I domain in complex with its cognate tRNA. Nature 500, 363–366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korostelev A, Trakhanov S, Laurberg M & Noller HF Crystal structure of a 70S ribosome-tRNA complex reveals functional interactions and rearrangements. Cell 126, 1065–77 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiter NJ et al. Structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P holoenzyme in complex with tRNA. Nature 468, 784–789 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann J, Jossinet F & Gautheret D A universal RNA structural motif docking the elbow of tRNA in the ribosome, RNase P and T-box leaders. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 5494–5502 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suddala KC et al. Hierarchical mechanism of amino acid sensing by the T-box riboswitch. Nat Commun 9, 1896 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J et al. Specific structural elements of the T-box riboswitch drive the two-step binding of the tRNA ligand. Elife 7(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwood AV, Frandsen JK, Grundy FJ & Henkin TM New tRNA contacts facilitate ligand binding in a Mycobacterium smegmatis T box riboswitch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 3894–3899 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lilley DM The K-turn motif in riboswitches and other RNA species. Biochim Biophys Acta 1839, 995–1004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J & Ferré-D’Amaré AR Direct evaluation of tRNA aminoacylation status by the T-box riboswitch using tRNA-mRNA stacking and steric readout. Mol Cell 55, 148–55 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollins SM, Grundy FJ & Henkin TM Analysis of cis-acting sequence and structural elements required for antitermination of the Bacillus subtilis tyrS gene. Mol Microbiol 25, 411–21 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correll CC, Freeborn B, Moore PB & Steitz TA Metals, motifs, and recognition in the crystal structure of a 5S rRNA domain. Cell 91, 705–712 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, Gérczei T, Glover L & Correll CC Crystal structures of restrictocin-inhibitor complexes with implications for RNA recognition and base flipping. Nature Struct. Biol. 8, 968–973 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosjean H & Westhof E An integrated, structure- and energy-based view of the genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 8020–40 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caserta E, Liu LC, Grundy FJ & Henkin TM Codon-Anticodon Recognition in the Bacillus subtilis glyQS T Box Riboswitch: RNA-DEPENDENT CODON SELECTION OUTSIDE THE RIBOSOME. J Biol Chem 290, 23336–47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winkler WC, Grundy FJ, Murphy BA & Henkin TM The GA motif: an RNA element common to bacterial antitermination systems, rRNA, and eukaryotic RNAs. RNA 7, 1165–1172 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leontis NB, Stombaugh J & Westhof E Motif prediction in ribosomal RNAs Lessons and prospects for automated motif prediction in homologous RNA molecules. Biochimie 84, 961–73 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suslov NB et al. Crystal structure of the Varkud satellite ribozyme. Nat Chem Biol 11, 840–6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabdulkhakov A, Nikonov S & Garber M Revisiting the Haloarcula marismortui 50S ribosomal subunit model. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69, 997–1004 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serganov A, Polonskaia A, Phan AT, Breaker RR & Patel DJ Structural basis for gene regulation by a thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitch. Nature 441, 1167–71 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards TE & Ferré-D'Amaré AR Crystal structures of the thi-box riboswitch bound to thiamine pyrophosphate analogs reveal adaptive RNA-small molecule recognition. Structure 14, 1459–1468 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert SD, Rambo RP, Van Tyne D & Batey RT Structure of the SAM-II riboswitch bound to S-adenosylmethionine. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15, 177–82 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein DJ, Edwards TE & Ferre-D'Amare AR Cocrystal structure of a class I preQ1 riboswitch reveals a pseudoknot recognizing an essential hypermodified nucleobase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 343–4 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cate JH et al. RNA tertiary structure mediation by adenosine platforms. Science 273, 1696–9 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westhof E & Fritsch V RNA folding: beyond Watson-Crick pairs. Structure 8, R55–65 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leontis NB & Westhof E A common motif organizes the structure of multi-helix loops in 16 S and 23 S ribosomal RNAs. J Mol Biol 283, 571–83 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreuzer KD & Henkin TM The T-Box Riboswitch: tRNA as an Effector to Modulate Gene Regulation. Microbiol Spectr 6(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demeshkina N, Jenner L, Westhof E, Yusupov M & Yusupova G A new understanding of the decoding principle on the ribosome. Nature 484, 256–9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korostelev A, Trakhanov S, Laurberg M & Noller H Crystal structure of a 70S ribosome-tRNA complex reveals functional interactions and rearrangements. Cell 126, 1065–1077 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogle JM et al. Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit. Science 292, 897–902 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hood IV et al. Crystal structure of an adenovirus virus-associated RNA. Nat Commun 10, 2871 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taufer M et al. PseudoBase++: an extension of PseudoBase for easy searching, formatting and visualization of pseudoknots. Nucleic Acids Res 37, D127–35 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR & Crothers DM The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell 18, 49–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Lau MW & Ferre-D'Amare AR Ribozymes and riboswitches: modulation of RNA function by small molecules. Biochemistry 49, 9123–31 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santner T, Rieder U, Kreutz C & Micura R Pseudoknot preorganization of the preQ1 class I riboswitch. J Am Chem Soc 134, 11928–31 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemay JF et al. Comparative study between transcriptionally- and translationally-acting adenine riboswitches reveals key differences in riboswitch regulatory mechanisms. PLoS Genet 7, e1001278 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suddala KC et al. Single transcriptional and translational preQ1 riboswitches adopt similar pre-folded ensembles that follow distinct folding pathways into the same ligand-bound structure. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 10462–75 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Day ES, Cote SM & Whitty A Binding efficiency of protein-protein complexes. Biochemistry 51, 9124–36 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Treeck B & Parker R Emerging Roles for Intermolecular RNA-RNA Interactions in RNP Assemblies. Cell 174, 791–802 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jain A & Vale RD RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 546, 243–247 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leontis NB & Westhof E Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA 7, 499–512 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References (Methods)

- 49.Zhao H, Piszczek G & Schuck P SEDPHAT--a platform for global ITC analysis and global multi-method analysis of molecular interactions. Methods 76, 137–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams P & al, e. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst D 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCoy A et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Afonine PV et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chou FC, Sripakdeevong P, Dibrov SM, Hermann T & Das R Correcting pervasive errors in RNA crystallography through enumerative structure prediction. Nat Methods 10, 74–6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factor amplitudes for the RNA have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank under accession code 6UFM [https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6UFM]. Source data for figure 2d, 3e and 5d are available online. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or available upon request.