Abstract

Approximately half of all cancer patients present with cachexia, a condition in which disease-associated metabolic changes lead to a severe loss of skeletal muscle mass. Working toward an integrated and mechanistic view of cancer cachexia, we investigated the hypothesis that cancer promotes mitochondrial uncoupling in skeletal muscle. We subjected mice to in vivo phosphorous-31 nuclear magnetic resonance (31P NMR) spectroscopy and subjected murine skeletal muscle samples to gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). The mice used in both experiments were Lewis lung carcinoma models of cancer cachexia. A novel ‘fragmented mass isotopomer’ approach was used in our dynamic analysis of 13C mass isotopomer data. Our 31P NMR and GC/MS results indicated that the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis rate and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle flux were reduced by 49% and 22%, respectively, in the cancer-bearing mice (p<0.008; t-test vs. controls). The ratio of ATP synthesis rate to the TCA cycle flux (an index of mitochondrial coupling) was reduced by 32% in the cancer-bearing mice (p=0.036; t-test vs. controls). Genomic analysis revealed aberrant expression levels for key regulatory genes and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed ultrastructural abnormalities in the muscle fiber, consistent with the presence of abnormal, giant mitochondria. Taken together, these data suggest that mitochondrial uncoupling occurs in cancer cachexia and thus point to the mitochondria as a potential pharmaceutical target for the treatment of cachexia. These findings may prove relevant to elucidating the mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle wasting observed in other chronic diseases, as well as in aging.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, cancer cachexia, mitochondria, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator-1β, uncoupling protein 3, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, adenosine triphosphate, tricarboxylic acid

Introduction

Approximately half of all cancer patients, particularly those with cancers of the gastrointestinal tract and lung (1–3), present with cachexia, in which disease-associated metabolic changes lead to a severe loss of skeletal muscle mass (4), resulting in a body weight reduction of ≥30% (5). Given the considerable information regarding the mechanisms underlying cancer cachexia that has come to light over the past decade (1,6–33) and the absence of available curative treatments for cancer cachexia (24,27,33–61), in the present study, we examined the hypothesis of mitochondrial uncoupling in cancer cachexia. Our hypothesis is based on our previous studies on experimental models of muscle wasting (62–71).

Although several clinically relevant animal models, in which animals exhibit a cachectic state, are characterized by profound muscle wasting, there is no consensus on which model should be used for the preclinical testing of cachexia therapies (72). In this study, we used the Lewis lung carcinoma murine model (45), which was successfully used in our previous study (71). Colon 26 adenocarcinoma is also an appropriate model for examining cachexia (73–75) and murine adenocarcinoma 16 (MAC16 adenocarcinoma) is a well-established model for studies on human gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancers (76). Indeed, muscle data obtained from mice bearing MAC16 tumors (77) are in agreement with human muscle biopsy data (78) and are suggestive of mitochondrial uncoupling.

In vivo nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy allows for the measurement of physiological biomarkers in intact cellular systems (79,80) and has been used to identify mitochondrial dysfunction in burn trauma (62), which is also characterized by severe muscle wasting. A novel ‘fragmented mass isotopomer’ approach [similar to bonded cumomer technique (81)] to the dynamic analysis of 13C mass isotopomer data, measured ex vivo by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), may be used to evaluate skeletal muscle tricarboxylic acid (TCA) flux and compare flux data under different conditions. The adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis rate to the TCA cycle flux ratio may then be calculated as an index of mitochondrial coupling (82,83).

Our recent NMR spectroscopy experiments, performed in conjunction with functional genomics, suggested the presence of mitochondrial dysfunction in a mouse model of cancer cachexia (71). Therefore, in the present study, we combined the same NMR technique with the GC/MS technique, to enable the assessment of the ATP synthesis rate and TCA cycle flux, respectively, and determine whether their ratio, which is an index of mitochondrial coupling, is affected in the skeletal muscle of animals in a cancer cachexia model. Our NMR spectroscopy and GC/MS experiments were complemented by genomic analysis and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57Bl/6 mice (weighing 20–25 g) (Charles River Laboratories, Boston, MA, USA) were used as a representative inbred stock and reliable reference population for the microarray analyses. The animals were maintained at 22±2°C with a regular light-dark cycle (lights on from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.) and allowed free access to standard rodent chow and water. The chow consisted of 54% carbohydrate, 17% protein and 5% fat (the remainder was non-digestible material). Food consumption was measured daily by subtracting the weight of food remaining after 24 h from the weight of food provided 24 h earlier. Daily net values of food consumption were used to determine the rate of food intake. In order to avoid the variability that may result from the female estrous cycle, only male mice were used. All animal experiments were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Tumor implantation

Mice were inoculated with Lewis lung carcinoma cells, according to an established protocol, under brief isoflurane anesthesia (3% in O2), as previously described (45, 71). Animals were randomized into tumor-free control (C) and tumor-bearing (TB) groups. Mice in the TB group were inoculated intramuscularly (right hind leg) with 4×105 Lewis lung carcinoma cells obtained from exponential tumors.

31P NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra of hind limbs were acquired 14 days after the intramuscular (hind leg) injection of 4×105 Lewis lung carcinoma cells from exponential tumors. All NMR spectroscopy experiments were performed using a horizontal bore magnet (400-MHz proton frequency and 21-cm diameter; Magnex Scientific), with a Bruker Avance console. A 90° pulse was optimized for the detection of phosphorus spectra (repetition time, 2 sec; 400 averages; 4,000 data points). Saturation 90°-selective pulse trains (duration, 36.534 msec; bandwidth, 75 Hz) followed by crushing gradients were used to saturate the γ-ATP peak. The same saturation pulse train was also applied downfield of the inorganic phosphate (Pi) resonance, symmetrically to the γ-ATP resonance. T1 relaxation times of Pi and phosphocreatine (PCr) were measured using an inversion recovery pulse sequence in the presence of γ-ATP saturation. An adiabatic pulse (400 scans; sweep with 10 kHz; 4,000 data points) was used to invert Pi and PCr, with an inversion time between 152 and 7,651 msec.

NMR spectroscopy data analysis

31P NMR spectra were analyzed using the MestReNova NMR software package (Mestrelab Research S.L. version 6.2.1 NMR solutions; www.mestrec.com). Free induction decays were zero-filled to 8,192 points and apodized with an exponential multiplication factor (30 Hz) prior to Fourier transformation. The spectra were then manually phased and corrected for baseline broad features with the Whittaker smoother algorithm (84). The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used to least-square fit a model of mixed Gaussian/Lorentzian functions to the data. Similarly, the T1obs relaxation time for Pi and PCr was calculated by fitting the function y = A1(1 − A2e−(t/T1obs)) to the inversion recovery data, where y is the z magnetization and t is the inversion time.

Calculation of ATP concentration and synthesis rate

The ATP concentration was measured using a Bioluminescence Assay kit CLS II (cat. no. 1699695; Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA). Information from 31P NMR spectra and the previously mentioned biochemically measured concentration of ATP was used to calculate the ATP synthesis rates, as previously described by Forsen and Hoffman (85). In brief, the chemical reaction between Pi and ATP is:

| [1] |

where kf and kr are the forward and reverse reaction rate constants, respectively. The influence of the chemical exchange between Pi and ATP on the longitudinal magnetization of Pi, M(Pi), is described by:

| [2] |

At equilibrium (dM(Pi)/dt) = 0 and with ATP saturation (M(ATP) = 0), equation [2] becomes:

| [3] |

The spin lattice relaxation time, T1app, measured using the inversion recovery pulse sequence in the presence of ATP saturation, is related to the intrinsic T1(Pi) by:

| [4] |

| [5] |

where ΔM(Pi)/M0(Pi) is the fractional change of the longitudinal magnetization M(Pi) of Pi. All quantities on the right side of [5] can be calculated from the NMR spectroscopy data. Finally, the unidirectional ATP synthesis flux can be calculated as:

| [6] |

where [Pi] is the concentration of Pi extrapolated from a baseline NMR spectrum by comparing the peak integrals from Pi and γ-ATP, with respect to the biochemically measured concentration of ATP.

TCA flux assessment

The TCA cycle flux was calculated from the timecourse of 13C mass isotopomers of glutamate (mass isotopomers M + 1 and M + 2 of glutamate), during an infusion of [2-13C]acetate. Plasma acetate concentration and 13C enrichment of glutamate in the gastrocnemius muscle were obtained by GC/MS, as previously described (86,87). A one-compartment dynamic metabolic model was used to fit 13C timecourses of mass isotopomers of glutamate to determine gastrocnemius metabolic flux values.

The model was mathematically expressed using 2 types of mass balance equations: i) mass balance for total metabolite concentration and ii) 13C mass isotopomer mass balance for labeled metabolites and their fragments, based on assumed bionetwork and atom distribution matrices (fragmented mass isotopomer framework).

In this model, the infused labeled (or unlabeled in plasma) glucose is transported from the extracellular medium to the muscle cells, assuming reversible non-steady-state Michaelis-Menten transport kinetics through the glucose transporter (GLUT4). Labeled acetate molecules are transported from the plasma to the cell interior and consequently to the mitochondria, obeying Michaelis-Menten kinetics, through the monocarboxylate transporter. The metabolic network includes glycolysis, the TCA cycle, α-ketoglutarate-glutamate and oxaloacetate-aspartate exchange, pyruvate carboxylase activity, anaplerosis at the succinyl-CoA level, pyruvate recycling through malic enzyme and acetyl-CoA synthetase activity. Once acetyl-CoA is formed, either through the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, β-oxidation or acetyl-CoA synthetase, it is used in the TCA cycle to produce energy and electron carriers.

Mass isotopomer balance equations were derived in a similar manner as the equations for bonded cumulative isotopomers (e.g., for glutamate, glutamine and aspartate), as previously described by Shestov et al(81). This study resulted in a set of 75 non-linear mass isotopomer ordinary differential equations. The concept of fragmented mass isotopomers, as well as bonded cumulative isotopomers (81), or bonded cumomers, leads to a reduced number of equations, as well as a more simple derivation of equations, compared to a model that includes all possible isotopomers, while retaining all mass spectrometry-measurable mass isotopomer information.

In terms of ordinary differential equations, the model describes the rates of loss and formation of particular labeled and unlabeled metabolite forms (mass isotopomers), following infusion of a labeled substrate. These equations are based on the flux balance of metabolites and take the form (e.g., for parallel unimolecular reactions):

where metabolite M is downstream of another metabolite, Sj. The total outflux balances the total influx ∑Fj. [M] represents the total pool size of metabolite M, while μ(i) and σj(i) represent the I mass isotopomer fraction of metabolite M (M + I mass isotopomer) and metabolite Sj (S + I mass isotopomer). The number of labeled C atoms in molecules, I, changes between 0 and N, where N is the total number of C atoms in the metabolites.

For labeled [2-13C]acetate infusion, the fitted timecourses were Glu M + 1 and Glu M + 2 mass-isotopomers, with a total of two curves. The two following fluxes were determined: gastrocnemius TCA cycle FTCA and exchange flux between glutamate and 2-oxoglutarate FX. Solving a system of non-linear differential equations in terms of whole/fragmented mass isotopomers, with the Runge-Kutta 4th order procedure for stiff systems, yields timecourses for all possible 13C mass isotopomers (e.g., glutamate, glutamine and aspartate). The cost function is used to quantify differences between measurements and computational results for labeled dynamic data. Minimization was performed with Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) or Simplex algorithms. Proper mean-square convergence was confirmed by verifying that goodness-of-fit values were close to the expected theoretical values. We estimated errors for the obtained values using Monte Carlo simulations with experimental noise levels. All numerical procedures were carried out using Matlab software.

Transmission electron microscopy

For mitochondrial morphology analysis, gastrocnemius muscles were extracted, dissected into small sections (~1 mm2) and transferred to glass vials filled with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (fixative buffer). The samples were maintained in the fixative buffer for 24 h at 4°C. The samples were rinsed 4 times with the same buffer (10 min per rinse) and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer containing 0.8% potassium ferricyanide for 90 min at 4°C. The dehydration procedure was performed in different dilutions of acetone in distilled water (50, 70, 90, 96 and 100% v/v). The dehydrated samples were infiltrated with Epon resin over 2 days, embedded in the same resin and allowed to polymerize at 60°C for 48 h.

Resin-embedded specimens were cut into semi-thin sections using an ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung Ultracut E) and the sections were stained with bromophenol blue, to visualize cell borders under a light microscope (Leica). When skeletal muscle fibers were detected and selected, we proceeded to collect ultra-thin sections using a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome and mounted the ultra-thin sections on Formvar-coated copper grids. The mounted sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate in water and lead citrate. The stained sections were observed under a JEM-1010 electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) with an acceleration voltage of 80 kV. Images were captured using a CCD camera (MegaView III) and digitized by software-supported analysis (Soft Imaging System, Münster, Germany).

RNA extraction, gene array hybridization and data analysis

Muscle specimens were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 60 sec using a tissue homogenizer (Brinkman Polytron PT3000), followed by TRIzol RNA extraction (Gibco-BRL). Total RNA was purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). RNA purity and quantity were assessed by spectrophotometry and capillary gel electrophoresis (Agilent 2100) and the RNA samples were stored at −80°C. Biotinylated cRNA was extracted from 10-mg samples of total RNA and hybridized to GeneChip® Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays, which were then stained, washed and scanned. All procedures followed standard Affymetrix, Inc. protocols (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and all experiments were performed in triplicate and analyzed as described in our previous publications (62,63).

Results

Fig. 1 shows representative 31P NMR spectra acquired from the mice in the C group before and after saturation of the γ-ATP resonance. Upon irradiation of the γ-ATP resonance, the signal intensities for the PCr, Pi, α-ATP and β-ATP resonances were all decreased, either by magnetization transfer or by direct off-resonance saturation.

Figure 1.

NMR spectra from in vivo31P NMR spectroscopy saturation-transfer experiments performed on the hind limb skeletal muscle of control (C) mice for determination of unidirectional inorganic phosphate (Pi) to ATP flux. Representative summed 31P-NMR spectra acquired from C before (upper curve) and after (lower curve) saturation of the γ-ATP resonance. The arrow on γ-ATP indicates the position of saturation by radiofrequency irradiation (−13.2 ppm). ppm, chemical shift in parts per million.

We discovered that the unidirectional synthesis rate of the Pi → γ-ATP reaction in the mice in the TB group was 49% lower compared to that observed in the mice in the C group (p=0.008). Additionally, the unidirectional synthesis rate of the PCr → γ-ATP reaction was 22% lower in the mice in the TB group compared to those in the C group, a difference that was significant according to a unidirectional (one-tailed) t-test (p=0.036). The NMR-measured fractional change in magnetization (ΔM/M0) was decreased by 37% in the TB group compared to the C group. The ATP concentration (14 days post-inoculation) was lower in the mice in the TB group compared to those in the C group by approximately 27%, a difference that approached significance (p=0.054) in the unidirectional (one-tailed) t-test.

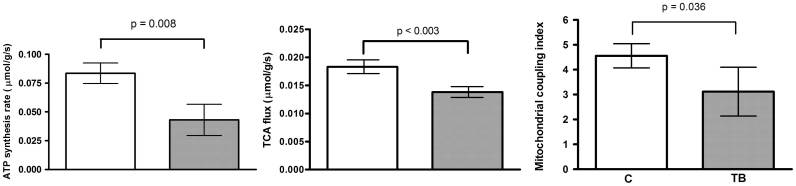

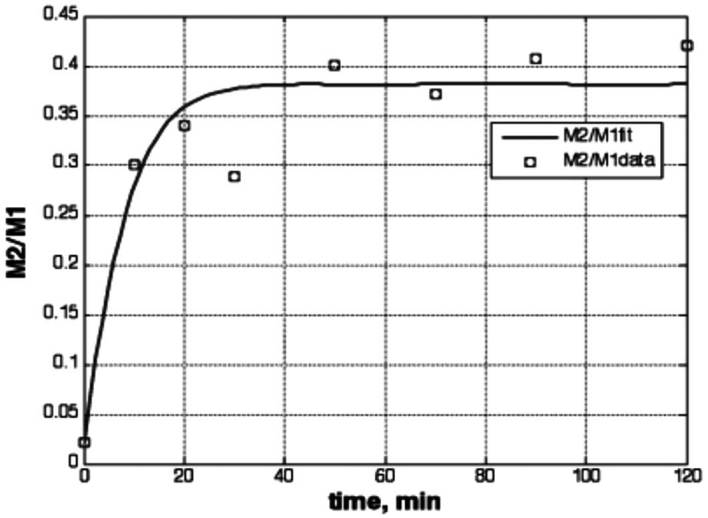

The experimental timecourse for the labeled glutamate mass isotopomer ratio M + 2/M +1 obtained during the infusion of [2-13C]acetate is presented in Fig. 2. As shown in Table I, we found that the ATP synthesis rate, calculated from 31P NMR spectroscopy data, and the TCA cycle flux, calculated from mass spectrometry data, were reduced by 49 and 25%, respectively, in the mice in the TB group (p=0.008 and p<0.003; Mann-Whitney U test). The ratio of the ATP synthesis rate to the TCA cycle flux (an index of mitochondrial coupling) was 32% lower in the mice in the TB group compared to those in the C group (p=0.036; Mann-Whitney U test; Table I). Fig. 3 graphically depicts the results presented in Table I.

Figure 2.

Dynamic profile for M + 2 to M + 1 ratio (M2/M1) of glutamate mass isotopomers during [2-13C]acetate infusion in mouse exhibiting cancer cachexia. Squares indicate experimental data points, and the line represents the best fit for our dynamic mass isotopomer model.

Table I.

ATP synthesis, TCA cycle flux and mitochondrial coupling index mean values (± standard errors) in control and tumor-bearing mice.

| Variable | C | TB | % Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP synthesis rate (μmol/g/sec) | 0.084±0.009 n=10 |

0.043±0.013 n=6 |

−48.8 | 0.008 |

| TCA flux (μmol/g/sec) | 0.018±0.005 n=18 |

0.014±0.003 n=18 |

−22.2 | <0.003 |

| Mitochondrial coupling indexa | 4.559±0.486 | 3.117±0.979 | −31.6 | 0.036 |

Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparisons.

Calculated per animal as the ratio of ATP synthesis rate to the TCA flux.

C, control mice; TB, tumor-bearing mice; n, number of mice.

Figure 3.

Rates of unidirectional ATP synthesis (left plot), TCA cycle flux (TCA, middle plot) and the coupling index (right plot), calculated as the ratio of the former two variables in control (C) and tumor-bearing (TB) mice.

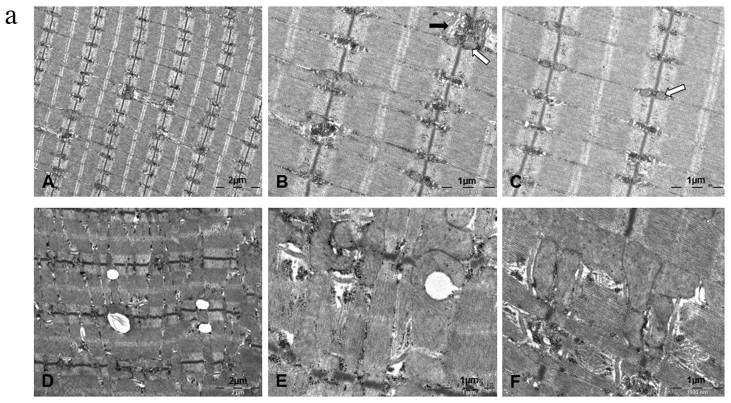

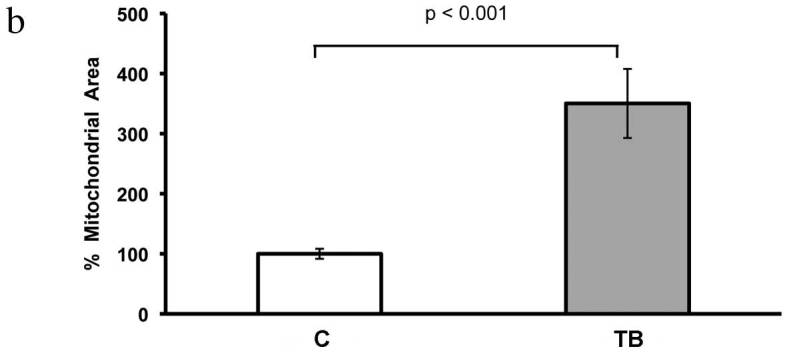

Images from our TEM observations showing features of gastrocnemius muscle morphology are presented in Fig. 4a. In gastrocnemius muscle samples from mice in the C group, we observed normal myofibrils with a clear division of bands and an intact sarcomere structure (Fig. 4a-A). Mitochondria in the control specimens were distributed along the Z line (Fig. 4a-B and -C, white arrows) and adjacent to triad structures (Fig. 4a-B, black arrow). In mice in the TB group, gastrocnemius muscle micrographs from the leg contralateral to the cancer cell inoculation were characterized by disorganization of myofibrils (Fig. 1D), giant mitochondria and lipid accumulation (Fig. 4a-E and -F). Moreover, the intermyofibrillar mitochondria area was increased by 3.5-fold (p<0.001) in cachectic gastrocnemius muscle from mice in the TB group (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) TEM micrographs from healthy control muscle (A–C) and cancer-induced cachectic (D–F) gastrocnemius muscle. White arrows, normal mitochondria; black arrow, triad structure. (b) Barograph showing the difference in the mitochondrial area between control and cancer-induced cachectic gastrocnemius muscle.

Gene expression analysis demonstrated that, compared to mice in the C group, mice in the TB group exhibited an upregulated expression of uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3; p=0.03), forkhead box O 3α (FOXO3α; p=0.04) and atrogin-1 (p=0.0084), as well as an upregulated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4; p=0.01), an inhibitor of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. The expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1β (PGC-1β) was significantly downregulated in the mice in the TB group (p=0.04 vs. C group). These results corroborate, in part, previous findings (19,71,88).

Discussion

The principle finding of this study was that TCA cycle flux determined by mass spectrometry was significantly reduced in mice in the TB group, compared to those in the C group. We further found that the ATP synthesis rate, determined by 31P NMR spectroscopy, was significantly reduced in mice in the TB group, which was consistent with our previous findings and suggestive of bioenergetic mitochondrial dysfunction (71). The ATP synthesis rate to the TCA cycle flux ratio (an index of mitochondrial coupling) was also reduced in mice in the TB group. In addition, our TEM observations revealed disrupted muscle morphology in mice in the TB group and our gene expression experiments demonstrated an upregulation of UCP3, FOXO3α, atrogin-1 and PDK4 expression, accompanied by a downregulation of PGC-1β expression. The novel results reported in this study provide evidence of mitochondrial uncoupling in cancer cachexia and demonstrate that cancer-induced cachexia leads to a profound functional and structural disorganization of murine skeletal muscle. Our data corroborate, in part, previous findings obtained from other experimental models (19,71,77,88–90), as well as data from human muscle biopsies (78).

To elucidate the function of gastrocnemius TCA flux in cancer cachexia, we used 13C-labeling experiments. We employed a novel fragmented mass isotopomer approach for the dynamic analysis of 13C mass isotopomer data measured ex vivo by GC/MS. Our dynamic labeling approach has several advantages compared to the steady-state isotopic approach commonly used for such studies. The main advantage of our approach is that it provides absolute flux values instead of flux ratios at network branch points. Secondly, it provides quantitative understanding of metabolic networks and enables researchers to discriminate between multiple pathways that give similar labeled metabolite patterns in steady-state analyses. Thirdly, our dynamic analysis approach requires less labeling time and thus requires less labeling compounds, which are costly. Finally, dynamic models enable researchers to gain a better insight into metabolic networks.

Of note, our NMR spectroscopy findings of mitochondrial dysfunction in the skeletal muscle of animals exhibiting cancer cachexia, are similar to observations previously made on murine models of burn trauma (62,68). In vivo31P NMR spectroscopy saturation transfer may be used to measure fast enzyme reaction exchange rates non-invasively (91) and, in particular, the net rate of oxidative ATP synthesis catalyzed by mitochondrial ATPase in skeletal muscle, which is proportional to oxygen consumption (92,93). It has been proposed that NMR-measured unidirectional ATP synthesis flux primarily reflects flux through F1F0-ATP synthase, with negligible influence of the coupled glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphoglycerate kinase reactions (82,94). Since these enzymes are present at near-equilibrium levels, the unidirectional production of ATP may be pronounced. Furthermore, since PDK4 expression is upregulated in cancer cachexia in mice, as shown in this study (Fig. 3) and in our previous study (71), as well as in rats (95), we hypothesized that the contribution of glycolytic reactions to unidirectional ATP synthesis flux is negligible, since PDK4 inhibits the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which is involved in controlling the use of glucose-linked substrates as sources of oxidative energy via glycolysis (96).

The aberrant expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1β) and uncoupling (UCP3) that we observed in this clinically relevant cancer cachexia model, are in agreement with previously reported data (71). The reduced expression of PGC-1β has also been observed in murine models of burn-induced skeletal muscle wasting (62,68), whereas increased PGC-1α protein levels have been reported in a rat cancer cachexia model (95), strongly suggesting that PGC-1 proteins play a key role in cancer-induced muscle wasting. Specifically, it has been suggested that PGC-1α protects skeletal muscle from atrophy (25), while PGC-1β expression has been associated with an increase in ATP-consuming reactions (97). Moreover, reduced PGC-1 expression levels have also been correlated with profoundly reduced mitochondrial content and activity (98). These effects may be due to the action of UCPs (65), given that PGC-1 downregulation is accompanied by increased UCP expression in murine models of both cancer- (89,90,95) and burn-related (62,65) cachexia. Increased levels of UCPs dissipate the proton gradient and lower the mitochondrial membrane potential, a process that increases energy expenditure by dissipating energy as heat (99). The presently observed upregulation of UCP3 in cancer cachectic animals agrees with our mitochondrial coupling index difference in suggesting the presence of mitochondrial uncoupling in cachectic mice and corroborates previous findings (78,88–90).

Our results are consistent with earlier studies on rats, in which an increase in UCP3 expression, induced by T3 treatment (94) or fasting (82), was associated with an increase in mitochondrial uncoupling. However, in contrast to these earlier studies, wherein the observed increase in mitochondrial uncoupling was the result of an increased TCA cycle flux (i.e., the denominator), the change in coupling that we observed in our cancer-bearing mice was the result of changes in both the ATP synthesis rate (the numerator) and TCA cycle flux (the denominator). Since the decrease in ATP synthesis rates was more pronounced than in the TCA cycle flux, the ratio (coupling index) was decreased. Our data are further supported by a previous report, demonstrating significantly increased mitochondrial coupling in UCP3 knockout mice (87).

Our TEM findings demonstrated that cancer-induced cachexia causes a profound structural disorganization of skeletal muscle characterized by fiber disruption, band disarrangement and dilated sarcoplasmic reticulum. In addition, the intermyofibrillar area in specimens from cachectic mice was characterized by the presence of giant mitochondria, which are formed when dysfunctional mitochondria are unable to achieve fusion (100). Swollen mitochondria have previously been described in cancer-induced cachexia (101). These giant mitochondria point to a causal effect of structural mitochondrial dysfunction on cancer-induced muscle wasting. In light of our previously published genomic data (71), the presently observed increase in intramyocellular lipids in specimens from mice in the TB group may be attributed to defective intracellular lipid metabolism. It has also been suggested that increased intramyocellular lipids may signal apoptosis (63), a process known to contribute to cancer-induced muscle wasting that was induced in our experimental murine model of cancer-induced cachexia (102).

In conclusion, our study fills a knowledge gap in an integrated and mechanistic view of cancer cachexia. Since the muscle wasting that occurs in cancer is similar to that observed in a number of other chronic diseases and aging, studies that focus on the mechanisms underlying cachexia are of significant public health relevance. Muscle biopsies from cachectic patients with pancreatic (103) and gastrointestinal cancer (26,78) have been reported to show supra-normal mitochondrial uncoupling (78), apoptosis and DNA fragmentation (26), as well as evidence of oxidative stress resulting from reactive oxygen species (ROS), a fact corroborated by animal studies (71,88,104). Although the integrity of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was not examined in this study, such effects may be inferred, given that mtDNA is highly vulnerable to oxidative damage induced by ROS, as it is situated closer to the site of ROS generation, lacks protective histones and has more limited base excision repair mechanisms than nuclear DNA (66,105–111). Further studies on the effects of cancer cachexia on mtDNA integrity, as well as studies designed to test mitochondrial agents are warranted.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Shriners Hospital for Children research grants (no. 8893) to A. Aria Tzika and (no. 8892) to Laurence G. Rahme. Cibely C. Fontes-Oliveira was supported by an Alban Scholarship Programme (E05D059293BR). We thank Ann Power Smith of Write Science Right for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Tisdale MJ. Cachexia in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:862–871. doi: 10.1038/nrc927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy DO. Rethinking nutritional support for persons with cancer cachexia. Biol Res Nurs. 2003;5:3–17. doi: 10.1177/1099800403005001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al-Majid S, McCarthy DO. Cancer-induced fatigue and skeletal muscle wasting: the role of exercise. Biol Res Nurs. 2001;2:186–197. doi: 10.1177/109980040100200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argilés J, et al. Cachexia: a new definition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windsor JA, Hill GL. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia. The importance of protein depletion. Ann Surg. 1988;208:209–214. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198808000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Mechanisms of muscle wasting. The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1897–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612193352507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogswell PC, Guttridge DC, Funkhouser WK, Baldwin AS., Jr Selective activation of NF-kappa B subunits in human breast cancer: potential roles for NF-kappa B2/p52 and for Bcl-3. Oncogene. 2000;19:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Madrid LV, Wang CY, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB-induced loss of MyoD messenger RNA: possible role in muscle decay and cachexia. Science. 2000;289:2363–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasselgren PO, Fischer JE. Muscle cachexia: current concepts of intracellular mechanisms and molecular regulation. Ann Surg. 2001;233:9–17. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Guttridge DC, You Z, et al. Wnt-1 signaling inhibits apoptosis by activating beta-catenin/T cell factor-mediated transcription. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:87–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You Z, Saims D, Chen S, et al. Wnt signaling promotes oncogenic transformation by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:429–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasselgren PO, Wray C, Mammen J. Molecular regulation of muscle cachexia: it may be more than the proteasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:1–10. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argilés JM, Busquets S, López-Soriano FJ. The role of uncoupling proteins in pathophysiological states. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, et al. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of >10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutstein HB. Mechanisms underlying cancer-induced symptoms. Drugs Today (Barc) 2003;39:815–822. doi: 10.1358/dot.2003.39.10.799474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acharyya S, Ladner KJ, Nelsen LL, et al. Cancer cachexia is regulated by selective targeting of skeletal muscle gene products. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:370–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI200420174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttridge DC. Signaling pathways weigh in on decisions to make or break skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:443–450. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000134364.61406.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, et al. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:39–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acharyya S, Butchbach ME, Sahenk Z, et al. Dystrophin glycoprotein complex dysfunction: a regulatory link between muscular dystrophy and cancer cachexia. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argilés JM, Busquets S, Felipe A, López-Soriano FJ. Molecular mechanisms involved in muscle wasting in cancer and ageing: cachexia versus sarcopenia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1084–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argilés JM, Busquets S, López-Soriano FJ. The pivotal role of cytokines in muscle wasting during cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:2036–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YP, Chen Y, John J, et al. TNF-alpha acts via p38 MAPK to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/MAFbx in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005;19:362–370. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2364com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skipworth RJ, Stewart GD, Ross JA, Guttridge DC, Fearon KC. The molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle wasting: implications for therapy. Surgeon. 2006;4:273–283. doi: 10.1016/S1479-666X(06)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandri M, Lin J, Handschin C, et al. PGC-1alpha protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busquets S, Deans C, Figueras M, et al. Apoptosis is present in skeletal muscle of cachectic gastro-intestinal cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melstrom LG, Melstrom KA, Jr, Ding XZ, Adrian TE. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle degradation and its therapy in cancer cachexia. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:805–814. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acharyya S, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia signaling pathways continue to emerge yet much still points to the proteasome. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1356–1361. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Argilés JM, López-Soriano FJ, Busquets S. Apoptosis signalling is essential and precedes protein degradation in wasting skeletal muscle during catabolic conditions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1674–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arany Z. PGC-1 coactivators and skeletal muscle adaptations in health and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandri M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:160–170. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:381–410. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popiela T, Lucchi R, Giongo F. Methylprednisolone as palliative therapy for female terminal cancer patients. The Methylprednisolone Female Preterminal Cancer Study Group. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1989;25:1823–1829. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(89)90354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kardinal CG, Loprinzi CL, Schaid DJ, et al. A controlled trial of cyproheptadine in cancer patients with anorexia and/or cachexia. Cancer. 1990;65:2657–2662. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900615)65:12<2657::AID-CNCR2820651210>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loprinzi CL, Schaid DJ, Dose AM, Burnham NL, Jensen MD. Body-composition changes in patients who gain weight while receiving megestrol acetate. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:152–154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Argilés JM, Almendro V, Busquets S, López-Soriano FJ. The pharmacological treatment of cachexia. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5:265–277. doi: 10.2174/1389450043490505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Busquets S, Figueras MT, Fuster G, et al. Anticachectic effects of formoterol: a drug for potential treatment of muscle wasting. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6725–6731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neary NM, Small CJ, Wren AM, et al. Ghrelin increases energy intake in cancer patients with impaired appetite: acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2832–2836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith HJ, Wyke SM, Tisdale MJ. Mechanism of the attenuation of proteolysis-inducing factor stimulated protein degradation in muscle by beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8731–8735. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon JN, Trebble TM, Ellis RD, Duncan HD, Johns T, Goggin PM. Thalidomide in the treatment of cancer cachexia: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2005;54:540–545. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Argilés JM, López-Soriano FJ, Busquets S. Emerging drugs for cancer cachexia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:555–570. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuster G, Busquets S, Almendro V, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. Antiproteolytic effects of plasma from hibernating bears: a new approach for muscle wasting therapy? Clin Nutr. 2007;26:658–661. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore-Carrasco R, Busquets S, Almendro V, Palanki M, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. The AP-1/NF-kappaB double inhibitor SP100030 can revert muscle wasting during experimental cancer cachexia. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:1239–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Argilés JM, Figueras M, Ametller E, et al. Effects of CRF2R agonist on tumor growth and cachexia in mice implanted with Lewis lung carcinoma cells. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:190–195. doi: 10.1002/mus.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fong LY, Jiang Y, Riley M, et al. Prevention of upper aerodigestive tract cancer in zinc-deficient rodents: inefficacy of genetic or pharmacological disruption of COX-2. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:978–989. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mantovani G, Madeddu C. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and antioxidants in the treatment of cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:275–281. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32830f47e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alamdari N, O’Neal P, Hasselgren PO. Curcumin and muscle wasting: a new role for an old drug? Nutrition. 2009;25:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Argilés JM, López-Soriano FJ, Busquets S. Therapeutic potential of interleukin-15: a myokine involved in muscle wasting and adiposity. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beijer S, Hupperets PS, van den Borne BE, et al. Effect of adenosine 5′-triphosphate infusions on the nutritional status and survival of preterminal cancer patients. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:625–633. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32832d4f22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Cornille K, Csibi A, Batonnet-Pichon S, Leibovitch MP, Leibovitch SA. Inhibition of atrogin-1/MAFbx mediated MyoD proteolysis prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in vivo. PloS One. 2009;4:e4973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madeddu C, Mantovani G. An update on promising agents for the treatment of cancer cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3:258–262. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283311c6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantovani G, Macciò A, Madeddu C, et al. Phase II nonrandomized study of the efficacy and safety of COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib on patients with cancer cachexia. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mantovani G, Madeddu C. Cancer cachexia: medical management. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy KT, Lynch GS. Update on emerging drugs for cancer cachexia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:619–632. doi: 10.1517/14728210903369351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noé JE. L-glutamine use in the treatment and prevention of mucositis and cachexia: a naturopathic perspective. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:409–415. doi: 10.1177/1534735409348865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell ST, Siren PM, Siren MJ, Tisdale MJ. Attenuation of skeletal muscle atrophy in cancer cachexia by D-myo-inositol 1,2,6-triphosphate. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0899-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siddiqui RA, Hassan S, Harvey KA, et al. Attenuation of proteolysis and muscle wasting by curcumin c3 complex in MAC16 colon tumour-bearing mice. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:967–975. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509345250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor LA, Pletschen L, Arends J, Unger C, Massing U. Marine phospholipids - a promising new dietary approach to tumor-associated weight loss. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Norren K, Kegler D, Argiles JM, et al. Dietary supplementation with a specific combination of high protein, leucine, and fish oil improves muscle function and daily activity in tumour-bearing cachectic mice. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:713–722. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weyermann P, Dallmann R, Magyar J, et al. Orally available selective melanocortin-4 receptor antagonists stimulate food intake and reduce cancer-induced cachexia in mice. PloS One. 2009;4:e4774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Padfield KE, Astrakas LG, Zhang Q, et al. Burn injury causes mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5368–5373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501211102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Astrakas LG, Goljer I, Yasuhara S, et al. Proton NMR spectroscopy shows lipids accumulate in skeletal muscle in response to burn trauma-induced apoptosis. FASEB J. 2005;19:1431–1440. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2005com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padfield KE, Zhang Q, Gopalan S, et al. Local and distant burn injury alter immuno-inflammatory gene expression in skeletal muscle. J Trauma. 2006;61:280–292. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000230567.56797.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Q, Cao H, Astrakas LG, et al. Uncoupling protein 3 expression and intramyocellular lipid accumulation by NMR following local burn trauma. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:1223–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan N, Mupparaju SP, Mintzopoulos D, et al. Burn trauma in skeletal muscle results in oxidative stress as assessed by in vivo electron paramegnetic resonance. Mol Med Report. 2008;1:813–819. doi: 10.3892/mmr-00000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tzika AA, Astrakas LG, Cao H, et al. Murine intramyocellular lipids quantified by NMR act as metabolic biomarkers in burn trauma. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:825–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tzika AA, Mintzopoulos D, Padfield K, et al. Reduced rate of adenosine triphosphate synthesis by in vivo 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and downregulation of PGC-1β in distal skeletal muscle following burn. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Righi V, Andronesi O, Mintzopoulos D, Tzika AA. Molecular characterization and quantification using state of the art solid-state adiabatic TOBSY NMR in burn trauma. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:749–757. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tzika AA, Mintzopoulos D, Mindrinos M, Zhang J, Rahme LG, Tompkins RG. Microarray analysis suggests that burn injury results in mitochondrial dysfunction in human skeletal muscle. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:387–392. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Constantinou C, Fontes de Oliveira CC, Mintzopoulos D, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance in conjunction with functional genomics suggests mitochondrial dysfunction in a murine model of cancer cachexia. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:15–24. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2010.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bennani-Baiti N, Walsh D. Animal models of the cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1451–1463. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanaka Y, Eda H, Tanaka T, et al. Experimental cancer cachexia induced by transplantable colon 26 adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2290–2295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diffee GM, Kalfas K, Al-Majid S, McCarthy DO. Altered expression of skeletal muscle myosin isoforms in cancer cachexia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1376–C1382. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00154.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gorselink M, Vaessen SF, van der Flier LG, et al. Mass-dependent decline of skeletal muscle function in cancer cachexia. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:691–693. doi: 10.1002/mus.20467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bibby MC, Double JA, Ali SA, Fearon KC, Brennan RA, Tisdale MJ. Characterization of a transplantable adenocarcinoma of the mouse colon producing cachexia in recipient animals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bing C, Brown M, King P, Collins P, Tisdale MJ, Williams G. Increased gene expression of brown fat uncoupling protein (UCP)1 and skeletal muscle UCP2 and UCP3 in MAC16-induced cancer cachexia. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2405–2410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Collins P, Bing C, McCulloch P, Williams G. Muscle UCP-3 mRNA levels are elevated in weight loss associated with gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma in humans. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:372–375. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ackerman JJ, Grove TH, Wong GG, Gadian DG, Radda GK. Mapping of metabolites in whole animals by 31P NMR using surface coils. Nature. 1980;283:167–170. doi: 10.1038/283167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hitzig BM, Prichard JW, Kantor HL, et al. NMR spectroscopy as an investigative technique in physiology. FASEB J. 1987;1:22–31. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.1.3301494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shestov AA, Valette J, Deelchand DK, Uğurbil K, Henry PG. Metabolic modeling of dynamic brain 13C NMR multiplet data: concepts and simulations with a two-compartment neuronal-glial model. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:2388–2401. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0782-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jucker BM, Ren J, Dufour S, et al. 13C/31P NMR assessment of mitochondrial energy coupling in skeletal muscle of awake fed and fasted rats. Relationship with uncoupling protein 3 expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39279–39286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Befroy DE, Falk Petersen K, Rothman DL, Shulman GI. Assessment of in vivo mitochondrial metabolism by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2009;457:373–393. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05021-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cobas JC, Bernstein MA, Martín-Pastor M, Tahoces PG. A new general-purpose fully automatic baseline-correction procedure for 1D and 2D NMR data. J Magn Reson. 2006;183:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Forsen S, Hoffman RA. Study of moderately rapid chemical exchange reactions by means of nuclear magnetic double resonance. J Chem Phys. 1963;39:2892–2901. doi: 10.1063/1.1734121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leimer KR, Rice RH, Gehrke CW. Complete mass spectra of N-trifluoroacetyl-n-butyl esters of amino acids. J Chromatogr. 1977;141:121–144. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)99131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cline GW, Vidal-Puig AJ, Dufour S, Cadman KS, Lowell BB, Shulman GI. In vivo effects of uncoupling protein-3 gene disruption on mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20240–20244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Busquets S, Almendro V, Barreiro E, Figueras M, Argilés JM, López-Soriano FJ. Activation of UCPs gene expression in skeletal muscle can be independent on both circulating fatty acids and food intake. Involvement of ROS in a model of mouse cancer cachexia. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sanchís D, Busquets S, Alvarez B, Ricquier D, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. Skeletal muscle UCP2 and UCP3 gene expression in a rat cancer cachexia model. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:415–418. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Busquets S, Sanchís D, Alvarez B, Ricquier D, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. In the rat, tumor necrosis factor alpha administration results in an increase in both UCP2 and UCP3 mRNAs in skeletal muscle: a possible mechanism for cytokine-induced thermogenesis? FEBS Lett. 1998;440:348–350. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alger JR, Shulman RG. NMR studies of enzymatic rates in vitro and in vivo by magnetization transfer. Q Rev Biophys. 1984;17:83–124. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500005266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sako EY, Kingsley-Hickman PB, From AH, Foker JE, Ugurbil K. ATP synthesis kinetics and mitochondrial function in the postischemic myocardium as studied by 31P NMR. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10600–10607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kingsley-Hickman PB, Sako EY, Uğurbil K, From AH, Foker JE. 31P NMR measurement of mitochondrial uncoupling in isolated rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1545–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jucker BM, Dufour S, Ren J, et al. Assessment of mitochondrial energy coupling in vivo by 13C/31P NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6880–6884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120131997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fuster G, Busquets S, Ametller E, et al. Are peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors involved in skeletal muscle wasting during experimental cancer cachexia? Role of beta2-adrenergic agonists. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6512–6519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roche TE, Baker JC, Yan X, et al. Distinct regulatory properties of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase and phosphatase isoforms. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;70:33–75. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(01)70013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.St-Pierre J, Lin J, Krauss S, et al. Bioenergetic analysis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivators 1alpha and 1beta (PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta) in muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26597–26603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uldry M, Yang W, St-Pierre J, Lin J, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 2006;3:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Giordano A, Calvani M, Petillo O, Carteni M, Melone MR, Peluso G. Skeletal muscle metabolism in physiology and in cancer disease. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:170–186. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Navratil M, Terman A, Arriaga EA. Giant mitochondria do not fuse and exchange their contents with normal mitochondria. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shum AM, Mahendradatta T, Taylor RJ, et al. Disruption of MEF2C signaling and loss of sarcomeric and mitochondrial integrity in cancer-induced skeletal muscle wasting. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:133–143. doi: 10.18632/aging.100436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Royen M, Carbó N, Busquets S, et al. DNA fragmentation occurs in skeletal muscle during tumor growth: A link with cancer cachexia? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:533–537. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.DeJong CH, Busquets S, Moses AG, et al. Systemic inflammation correlates with increased expression of skeletal muscle ubiquitin but not uncoupling proteins in cancer cachexia. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Barreiro E, de la Puente B, Busquets S, López-Soriano FJ, Gea J, Argilés JM. Both oxidative and nitrosative stress are associated with muscle wasting in tumour-bearing rats. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Turrens JF, Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1980;191:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj1910421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Turrens JF, Freeman BA, Levitt JG, Crapo JD. The effect of hyperoxia on superoxide production by lung submitochondrial particles. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;217:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bandy B, Davison AJ. Mitochondrial mutations may increase oxidative stress: implications for carcinogenesis and aging? Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:523–539. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Esposito LA, Melov S, Panov A, Cottrell BA, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial disease in mouse results in increased oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4820–4825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Imam SZ, Karahalil B, Hogue BA, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA-repair capacity of various brain regions in mouse is altered in an age-dependent manner. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]