Abstract

Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit (AWV) was introduced in 2011 to promote evidence-based preventive care and identify undiagnosed risk factors and conditions in aging adults. Since then, AWV use has risen steadily, yet the visit’s benefits remain unclear. Using 2008–2015 national Medicare data, we examined fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries attributed to practices that did or did not adopt the AWV. We performed difference-in-differences analysis to compare differential changes in appropriate and low-value cancer screening, functional and neuropsychiatric care, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and total spending. Examining 17.8 million beneficiary-years, we found modest differential improvements in evidence-based screening rates and declines in emergency department visits; however, when we accounted for trends pre-dating visit introduction, none of these benefits persisted. In sum, we find no substantive association between AWVs and improvements in care.

Keywords: Medicare, Annual Wellness Visit, preventive care, annual physical, primary care

Introduction

Annual check-ups are a ubiquitous feature of primary care despite ongoing debate as to whether such visits improve outcomes.(1–5) In 2011, Medicare introduced the Annual Wellness Visit (AWV): the first time Medicare offered such check-ups at no cost to its fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries.(6) Medicare reimburses the AWV at a higher rate than a typical office visit and recently added a small monetary incentive for some beneficiaries to obtain the visit (Appendix Exhibit 1).(6–8) AWV use among eligible beneficiaries has grown from 7.5% in 2011(9) to 18.8% in 2015, reaching millions each year at a cost of more than a billion dollars in visit reimbursements alone. At the same time, there has been marked variation in AWV use across physician practices: in 2015, half of practices provided no AWVs while 23% provided them to at least a quarter of their eligible beneficiaries.(10)

Like other annual check-ups, the AWV might be expected to promote evidence-based preventive care and identify undiagnosed risk factors and conditions. To this end, the AWV specifically includes visit requirements such as functional assessment and screening for cancer, depression, and cognitive impairment (Appendix Exhibit 2).(8,9,11) Through proactive identification and treatment of medical risks and the opportunity to bolster primary care relationships, AWVs might in turn reduce the need for emergency department visits and hospitalizations, or lower spending.(1,5,12) Previous work on AWVs examining some of these outcomes showed modest improvements in use of some screening services but not others.(13–17) However, these studies were limited by reliance on self-report, focus on single systems, short follow-up periods, or most notably, potential selection bias (i.e. unobservable differences, such as health-consciousness, in patients who choose to receive an AWV compared to those who do not).(18,19)

To address these limitations and advance understanding of the AWV’s impact, we exploited practice-level variation in AWV uptake to assess the visit’s association with improvements in evidence-based screening, referrals, utilization, and spending among eligible beneficiaries. Specifically, we used practice AWV adoption as the exposure of interest and compared beneficiaries who received care at practices that adopted the AWV with beneficiaries at practices that did not - an “intention-to-treat” approach to mitigate the beneficiary-level selection bias that would compromise comparison of beneficiaries receiving an AWV with those not receiving one. Using difference-indifferences analysis, we assessed a set of outcomes that might be associated with the AWV: appropriate and low-value cancer screenings; referrals for neuropsychiatric and functional issues; emergency department visits and hospitalizations; and spending.

Study Data and Methods

Data –

We examined 2008–2015 national Medicare Parts A and B claims for a 20% sample of beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare.

Beneficiary sample –

For each study year, we examined beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in FFS Medicare (or, if decedent, continuously enrolled until death) and eligible for an AWV based on at least one prior year of Medicare FFS enrollment. We attributed each beneficiary to the practice that accounted for more of the beneficiary’s visits with a primary care physician (based on specialty in general practice, family practice, internal medicine, or geriatrics) than any other practice in a given year. To break ties, we chose the practice with the largest share of total primary care charges (including 99201–99215, 99241–5, and G0438–9); if there was still a tie, we used the practice providing the last visit in that year (Appendix Methods).(8)

Practice sample –

We defined practices by their tax identification number.(10,20) We limited our sample to practices that had at least ten attributed Medicare beneficiaries and were continuously present in our data throughout 2008–2015 (allowing us to define practices by their 2015 AWV use). Among the practices in our sample, we identified AWV adopters (practices that provided any AWVs to their eligible beneficiaries in 2015) and AWV non-adopters (practices that provided no AWVs in 2015).

Beneficiary characteristics –

We measured demographic characteristics of populations attributed to AWV adopter and non-adopter practices in each year. We used standard Medicare claims classifications to determine age, sex, race, and dual enrollment in Medicaid. To calculate Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) risk scores, we used Medicare enrollment and claims data from the calendar year preceding each given year (Appendix Exhibit 4).(8)

Practice characteristics –

In each year, we measured practice characteristics previously shown to be associated with visit adoption that might confound the relationship between adoption and our outcomes:(10) geographic setting, percentage hospital-based (vs independent), specialty mix (percentage of physicians who specialize in primary care), size (number of primary care physicians), and number of attributed Medicare beneficiaries (Appendix Exhibit 4).(8)

Outcome measures –

We chose to assess a set of outcomes based on prior research on AWVs and annual check-ups as well as on Affordable Care Act and AWV requirements.(6,21) We then defined these measures using prior literature, US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, and the HealthCare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). We calculated the measures annually among relevant populations (Appendix Exhibit 5).(8)

Appropriate screening measures –

A key component of the AWV is assessing whether patients have received age-appropriate preventive screening. We measured percent of women 50–74 years old who received a mammogram; and percent of individuals 50–75 years old with no prior colorectal cancer diagnosis who received colorectal cancer screening (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, CT colonography, fecal immunochemical testing, or fecal occult blood testing).

Low-value screening measures –

Medicare’s emphasis on evidence-based screening during the AWV could also discourage use of guideline-discordant cancer screening. We assessed percent of individuals ≥86 years old with no prior colorectal cancer diagnosis who received colorectal cancer screening; percent of women ≥66 years old with no prior cervical cancer diagnosis who received a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear; and percent of men >75 years old with no prior prostate cancer diagnosis who received prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening.

Neuropsychiatric/functional care measures –

During the AWV, clinicians assess patients for physical and cognitive impairments. As a measure of the impact of such assessments, we calculated the percent of beneficiaries who received a new patient visit with a psychiatrist or neurologist; and the number of physical therapy and occupational therapy visits per 100 beneficiary-years.

Health care utilization/spending measures –

By strengthening the primary care relationship and proactively addressing medical risks and conditions, the AWV may reduce higher acuity care utilization. In particular, emergency department visits and hospitalizations for “ambulatory care sensitive conditions” are considered potentially avoidable with effective outpatient care.(22,23) We measured number of emergency department visits and hospitalizations for any condition and for an ambulatory care sensitive condition per 100 beneficiary-years; and total Part A and B Medicare spending per beneficiary.

Statistical analyses:

For each outcome, we fit a beneficiary-year-level, linear difference-in-differences model to compare change between adopter and non-adopter practices from the pre-AWV period (2008–2010) to 2015.(24) Specifically, the model included a term for attribution to an AWV-adopting practice and each year in the pre-AWV period (2008–2010) and post-AWV period (2013–2015), as well as interactions between AWV-adopting practice attribution and each year of the post-AWV period to produce the differential changes of interest. The models included the aforementioned beneficiary characteristics, practice characteristics, and geography at the level of hospital referral region (HRR). They also included interactions between each beneficiary characteristic and year, and interactions between HRR and each year, allowing us to estimate differential changes for beneficiaries of adopter practices relative to concurrent changes for beneficiaries of non-adopter practices with the same characteristics or living in the same HRR. We omitted 2011–2012 from the pre- and post-periods because AWV uptake was low during these transition years after AWV introduction (Appendix Methods).(8,9)

Our difference-in-differences approach assumed that differences in outcomes between adopter and non-adopter practices would have remained constant over the study period in the absence of AWV introduction. There are two overarching reasons why this assumption may be violated. First, the population treated by adopter practices may have changed over time in ways different from non-adopter practices. For example, practices that adopted AWVs may have attracted more engaged beneficiaries. Because we included AWVs when using office visits to attribute beneficiaries to practices, our categorization of practices may have been partly driven by differences in demand for preventive care. To assess this potential threat to validity, we compared beneficiary attribution with and without use of AWVs and found that AWVs had minimal effect on the size of populations attributed (Appendix Exhibit 3).(8) We examined differential changes in observable beneficiary characteristics, adjusted for geography. We also assessed how differential changes in our outcomes were affected by adjustment for beneficiary characteristics and beneficiary characteristics interacted with time, finding that this adjustment produced directionally consistent results of smaller magnitude (Appendix Exhibits 7,8).(8)

Second, adopter and nonadopter practices may have exhibited different (non-parallel) trajectories in quality and efficiency independent of the AWV. To address this, we compared trends in outcomes between adopter and non-adopter practices during the pre-AWV period. Recent methodological research suggests that significance testing for parallel pre-intervention trends (the “parallel trends test”) does not reliably rule out potentially meaningful violations of the parallel trends assumption, particularly when effect sizes are small.(25) Therefore, we instead estimated differential changes in our outcomes that would be expected if differences in pre-AWV period trends had continued into the post-AWV period through 2015 (Appendix Exhibit 9).(8) Because we detected potentially meaningful differences in pre-AWV period trends for some outcomes, we present both trend-adjusted and non-trend-adjusted differential changes to provide bounds under each set of assumptions (1 - that pre-AWV trends were parallel and 2 – that differences in pre-AWV trends continued into the post-AWV period).

One potential concern with our definition of intervention population is that only 30% of eligible beneficiaries received an AWV. In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated our main analyses but instead compared beneficiaries in AWV non-adopter practices to those in the subset of practices that provided the visit to at least 25% of their eligible beneficiaries in 2015 (“intensive adopters”). In these intensive adopter practice, 49% of beneficiaries received an AWV in 2015 (see Appendix). In an exploratory subgroup analysis to see if AWVs may differentially benefit underserved populations, we examined the association between AWV uptake and our outcomes among beneficiaries in our cohort who were dually enrolled in Medicaid.

We used robust variance estimation to account for clustering of observations within HRRs and reported two-sided p values.

Because we tested multiple outcomes, we applied Bonferroni correction to a 5% false discovery rate to set a new statistical significance threshold of p<0.002. We used SAS (version 7.12) to perform the analyses.

Limitations:

Our study has several limitations. While we used difference-in-differences analysis and a practice-level approach to mitigate the selection bias found in comparisons of beneficiaries who did or did not receive a wellness visit,(19) our results may be biased by unmeasured practice-level confounders (e.g. AWV adopting practices may be more likely to engage in other quality improvement efforts or attract more engaged beneficiaries). However, when we controlled for observed shifts in practice demographics, our results were substantively the same, suggesting that unobserved changes were unlikely to alter our conclusions. We further addressed these concerns by controlling for time-varying practice characteristics and presenting results with and without pre-intervention trends to provide a bound on the potential association between AWV adoption and our outcomes. In addition, we would expect that these sources of potential bias would have led us to find increases in appropriate preventive services and decreases in ED use and hospitalizations, whereas we found no substantial effects. Our results are limited to the Medicare fee-for-service population and may not generalize to Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. In addition, we measured yearly use of appropriate screening services rather than what fraction of patients were up to date on the screening, though we would not expect this to bias our results.(15) While we examined an array of outcomes, future studies might explore other outcomes such as self-reported health or management of falls. Additional research should focus on the optimal target populations and frequency of the AWV, and how to improve visit quality.

Results

Among the 23,665 practices continuously present between 2008–2015, 15,123 practices adopted the AWV (N=14,519,940 attributed beneficiary-years) and 8,542 did not (N=3,237,760 beneficiary-years). Thirty percent (30.0%) of beneficiaries attributed to adopter practices received an AWV in 2015.

Demographic characteristics –

Compared to beneficiaries attributed to non-adopter practices, those in adopter practices were older, less medically complex, and less likely to belong to a minority group or be dually enrolled in Medicaid. The differential changes in these characteristics over the study period (2008–2010 to 2015) were of small magnitude (Appendix Exhibit 6).

Pre-AWV period outcomes –

In 2008–2010, beneficiaries attributed to adopter practices had higher rates of appropriate and low-value screenings and of neuropsychiatric/functional care, and lower rates of ED visits, hospitalizations, and total spending than those in non-adopter practices (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1.

Association between Annual Wellness Visit exposure and screening, referrals, utilization, and spending in difference-in-differences analyses, 2008–10 versus 2015

SOURCE Authors’ beneficiary-level analysis of 20 percent Medicare claims data

| Outcome category |

Outcome | Yearly rate among beneficiaries in pre-AWV period, 2008–10 |

Difference-in-difference estimates, 2008–10 vs. 2015b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non- adopter prac- tices |

Adopter prac- tices |

Adjusted difference between adopter and non-adopter practices |

Not adjusted for pre- intervention trend, 95% CI |

Adjusted for pre- intervention trend, 95% CI |

||

| Appropriate screening | Mammography, % | 46.3 | 53.7 | 2.3 | 0.82c (0.37, 1.27) | 0.41 (−0.96, 1.79) |

| CRC screening, % | 12.9 | 14.3 | 1.4 | 0.14 (−0.23, 0.51) | 0.18 (−0.66, 1.01) | |

| Low-value screening | Pap smears, % | 9.8 | 11.0 | 0.61 | −0.61c (−0.80, 0.43) | −0.46 (−1.02, 0.11) |

| PSA testing, % | 46.8 | 46.9 | 2.5 | −1.41c (−2.00, 0.82) | 0.47 (−1.29, 2.24) | |

| CRC screening, % | 8.1 | 8.2 | 0.61 | −0.16 (−0.47, 0.16) | 0.54 (−0.57, 1.66) | |

| Neuropsychiatric and functional care | Specialist referral, % | 3.5 | 3.7 | 0.21 | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.11) | −0.03 (−0.31, 0.26) |

| PT/OT visits, rate per 100 beneficiary -years | 19.2 | 21.4 | 0.77 | 0.86c (0.51, 1.21) | 0.17 (−0.81, 1.15) | |

| Emergency Department visitsa | All, rate per 100 beneficiary-years | 77.7 | 70.1 | −1.3 | −2.07c (−2.92, −1.22) | 0.00 (−2.68, 2.68) |

| Ambulatory sensitive condition, rate per 100 beneficiary -years | 46.4 | 42.6 | −0.18 | −1.57c (−2.22, −0.92) | −0.38 (−2.12, 1.36) | |

| Hospitalizationsa | All, rate per 100 beneficiary-years | 41.7 | 37.7 | −1.07 | −0.30 (−0.74, 0.14) | 0.89 (−0.51, 2.28) |

| Ambulatory sensitive condition, rate per 100 beneficiary -years | 36.7 | 33.0 | −1.0 | 0.0 (−0.38, 0.39) | 1.07 (−0.26, 2.40) | |

| Spending | Total, per beneficiary, $ | 10,262.0 | 9,140.6 | −192.9 | −58.14 (−159.00, 42.72) | 290.84 (19.80, 561.88) |

NOTES CRC is colorectal cancer; Pap is Papanicolaou. PSA is prostate specific antigen. Specialist refers to physicians with specialty in neurology or psychiatry. PT is physical therapy. OT is occupational therapy.

Emergency Department visits and hospitalizations were examined from January 1-September 30 of each year to allow consistent use of ICD-9 codes for these measures (transition to ICD-10 coding October 1, 2015).

Both models controlled for beneficiary characteristics (age, sex, race, dual enrollment in Medicaid, Hierarchical Condition Category score), practice characteristics (geographic setting, hospital-based vs independent site, specialty mix, size, number of attributed Medicare beneficiaries), geography at the level of hospital referral region (HRR), and the interaction between beneficiary characteristics and year and between HRR and year. The model adjusted for pre-intervention trend also included a term for AWV adoption interacted with a continuous year variable.

Cancer screening –

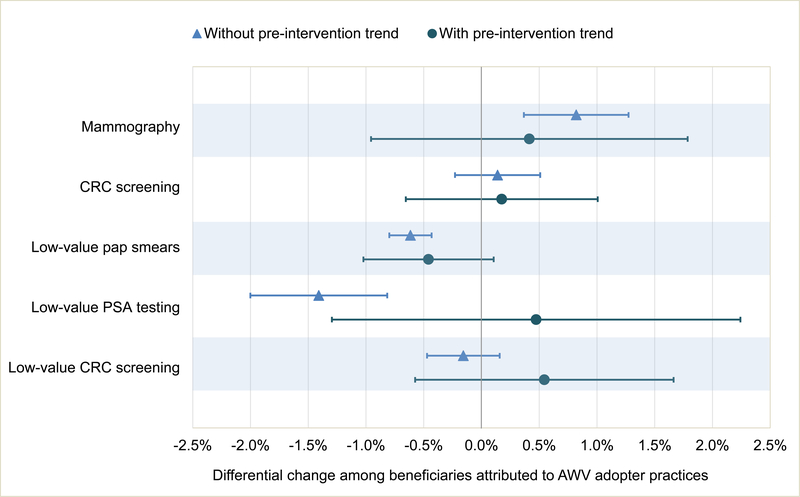

In 2015 (post-AWV introduction), we found small differential increases in appropriate screenings and declines in low-value screenings that were not robust to adjustment for pre-intervention trend differences. For example, when we accounted for pre-intervention trend, the 0.82% (95%CI 0.37,1.27) differential rise in mammography rate decreased to 0.41% (95% CI −0.96,1.79) and became nonsignificant (Exhibits 1, 2A, Appendix Exhibit 9).(8)

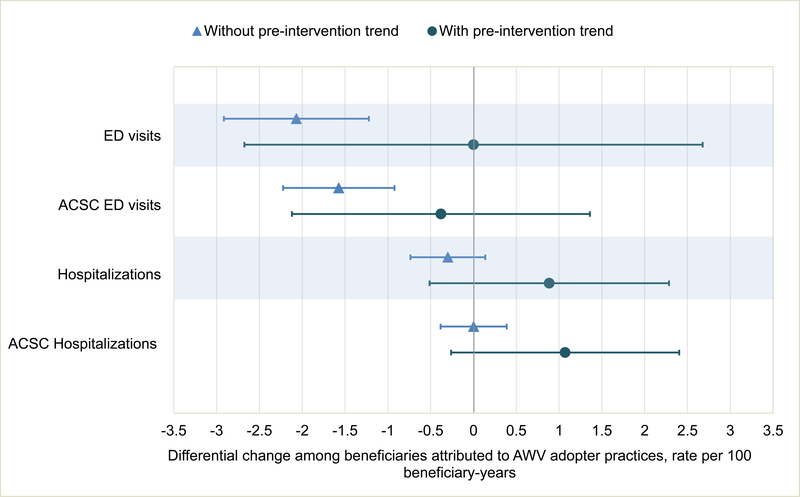

Exhibit 2.

CAPTION A. Differential changes in appropriate and low-value cancer screening associated with AWV exposure B. Differential changes in health care utilization associated with AWV exposure

SOURCE Authors’ beneficiary-level analysis of 20 percent Medicare claims data

NOTES CRC is colorectal cancer. Pap is Papanicolaou. PSA is prostate specific antigen. ED is emergency department. ACSC is ambulatory care sensitive conditions. This figure displays data also shown in Exhibit 2. Both models controlled for beneficiary characteristics (age, sex, race, dual enrollment in Medicaid, Hierarchical Condition Category score), practice characteristics (geographic setting, hospital-based vs independent site, specialty mix, size, number of attributed Medicare beneficiaries), geography at the level of hospital referral region (HRR), and the interaction between beneficiary characteristics and year and between HRR and year. The model “with pre-intervention trend” also included a term for AWV adoption interacted with a continuous year variable.

Functional and neuropsychiatric care –

Beneficiaries in adopter practices had a small, significant differential increase in use of physical or occupational therapy; this was not observed when accounting for pre-intervention trend (Exhibit 1).

Utilization and spending –

We found modest differential drops in all ED visits and in those for ambulatory sensitive conditions; these became nonsignificant with the inclusion of preintervention trends. We found no significant differential change in hospitalizations, including those for ambulatory sensitive conditions, with or without accounting for pre-intervention trends (Exhibit 2B). There was a nonsignificant differential drop of $58.14 in total per beneficiary Medicare spending among beneficiaries in adopter practices; when accounting for preintervention trends, we found a nonsignificant differential increase of $290.84 (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3.

CAPTION Adjusted spending trends among Medicare beneficiaries attributed to AWV adopter vs AWV non-adopter practices

SOURCE Authors’ beneficiary-level analysis of 20 percent Medicare claims data

NOTES Total Medicare spending among beneficiaries attributed to Annual Wellness Visit (AWV) adopter vs non-adopter practices, adjusted for beneficiary characteristics (age, sex, race, dual enrollment in Medicaid, Hierarchical Condition Category score), practice characteristics (geographic setting, hospital-based vs independent site, specialty mix, size, number of attributed Medicare beneficiaries), geography at the level of hospital referral region (HRR), and the interaction between beneficiary characteristics and year and between HRR and year.

When we compared beneficiaries in non-adopter vs intensive adopter practices, our conclusions were substantively unchanged (Appendix Results, Appendix Exhibit 10).(8) Similarly, the subgroup analysis of dual enrollees in non-adopter vs adopter practices found no association between AWV exposure and our outcomes (Appendix Exhibit 11).

Discussion

We found that AWV use was not associated with meaningful, consistent changes in appropriate or low-value cancer screening, neuropsychiatric or functional care, acute care use, or spending. There were some favorable changes in screening and utilization (e.g. differential increases in mammography rates, differential declines in low-value pap smear and ED visit rates) that were small and largely clinically insignificant (even if we multiply them by three since roughly a third of enrollees received an AWV in the intervention practices). What’s more, none of these benefits persisted when accounting for the trends that pre-dated AWV introduction and our findings were similar in a sensitivity analysis examining practices with higher uptake of the AWV. Together, the magnitude and lack of consistency across our analyses and the array of measures we examined suggest that AWV adoption itself was not associated with substantial improvements in care.

These results align with prior AWV studies showing inconsistent benefits.(14,17) For example, in one health system, AWV adoption was associated with slightly greater use of some routine, appropriate services (e.g. advance directives, abdominal aortic aneurysm screening, mammography), but decreased use of others (e.g. colorectal cancer screening, bone density scans).(13) Another study using national survey data found no significant change in self-reported preventive service rates before or after AWV introduction.(15) Our results are also consistent with the larger literature on annual check-ups showing mixed effects on most preventive measures, hospitalizations, and costs.(5,26) This is the first study to our knowledge to assess the AWV – arguably the most prescriptive, evidence-based version of an annual check-up - on a national scale across a range of clinical and utilization outcomes.

Several factors may contribute to the lack of consistent association between AWV use and the outcomes we assessed. First, despite Medicare’s specific requirements that the AWV include a number of screening services, the AWV may not elicit a large enough change in clinician practice to produce improvements. In prior research, AWVs seemed to replace other problem-based visits, suggesting that clinicians may bill for these visits (and check the necessary boxes) yet not appreciably change how they practice.(10) Medicare lagged behind other insurers in covering an annual check-up; many doctors likely provided annual check-ups to Medicare beneficiaries yet billed them as problem-based visits. Conversely, in some cases, AWV requirements could crowd out more important conversations during a visit, perhaps proving counterproductive to the goals of preventing ED visits and hospital-level care. Some clinicians have even criticized AWV requirements for impeding the relationship-building aspects of an office visit.(27,28)

Second, while the AWV provides an opportunity for clinicians to discuss screening plans with their beneficiaries and Medicare now covers many preventive services without cost-sharing,(6) beneficiaries may still face financial, transportation, and other barriers to successful completion of these services.(29) Notably, research on efforts to improve preventive care uptake in general show that improvements are incremental at best.(15) Third, AWVs may not be received by the beneficiaries most likely to benefit from a health assessment – for example, those overdue for screening tests or with undiagnosed depression or physical frailty.(30) This is supported by previous work showing that the largest predictor of receiving an AWV was having one the year before, while AWVs were less likely to be used by historically underserved beneficiaries – those who were nonwhite, lived in rural, low-income areas, and were dually-enrolled in Medicaid.(9,10) Indeed, our subgroup analysis of dual enrollees was limited by the low AWV uptake in this population.

Policy Implications

Our work suggests that Medicare’s introduction of a new billing code for annual check-ups and associated visit requirements were insufficient to improve uptake of evidence-based preventive services and to reduce higher acuity care and spending. In order for AWVs to contribute to these goals more effectively, policymakers and clinicians might examine ways to customize and deliver these visits to the beneficiaries most likely to benefit – for example, through attention to social and behavioral determinants of health and targeted outreach to beneficiaries who are less engaged in care.(30) They might also invest in complementary mechanisms to bolster primary care while achieving the visit’s goals. To improve evidence-based screening, health systems could focus on tactics such as cancer screening registries managed by population health coordinators, text-based reminders, and clinical decision support tools used during any point of contact with the health care system.(31–34)

Conclusion

In sum, we find no consistent evidence of an association between AWV use and appropriate or low-value cancer screening, neuropsychiatric/functional care, ED visits, hospitalizations, or spending. Our work suggests that the introduction of Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit was not sufficient to improve uptake of evidence-based preventive services and to reduce higher acuity care and spending, particularly given other barriers to such improvements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Ishani Ganguli reports receiving consultant fees from Haven. The work of Jeffrey Souza and J. Michael McWilliams was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. P01 AG032952)

Contributor Information

Ishani Ganguli, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts..

Jeffrey Souza, programmer in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School..

J. Michael McWilliams, Warren Alpert Foundation Professor of Health Care Policy in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School..

Ateev Mehrotra, associate professor of health care policy and medicine in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School..

Endnotes

- 1.Boulware LE, Barnes GJ, Wilson RF, Phillips K, Maynor K, Hwang C, et al. Value of the periodic health evaluation. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) [Internet]. 2006. April [cited 2018 Aug 10];(136):1–134. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17628127 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laine C The annual physical examination: needless ritual or necessary routine? Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2002. May 7 [cited 2018 Aug 10];136(9):701–3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11992306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra A, Prochazka A. Improving Value in Health Care — Against the Annual Physical. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2015. October 15 [cited 2018 Aug 10];373(16):1485–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26465981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goroll AH. Toward Trusting Therapeutic Relationships — In Favor of the Annual Physical. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2015. October 15 [cited 2018 Aug 10];373(16):1487–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26465982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krogsbøll LT, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. General Health Checks in Adults for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality From Disease. JAMA [Internet]. 2013. June 19 [cited 2018 Aug 10];309(23):2489 Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2013.5039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patient Protection And Affordable Care Act [Internet]. 2010. [cited 2018 Dec 17]. Available from: http://docs.house.gov/

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Coordinated Care Reward [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/MedicareLearning-Network

- 8.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 9.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Trends in Use of the US Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, 2011–2014. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2233–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Practices Caring For Underserved Less Likely to Adopt Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit. Health Aff. 2018;37(2):283–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh HK, Sebelius KG. Promoting Prevention through the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2010. September 30 [cited 2018 Dec 3];363(14):1296–9. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMp1008560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochazka A V, Caverly T General Health Checks in Adults for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality From Disease. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2013. March 11 [cited 2019 Jan 18];173(5):371 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23318544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, Johns NE, Palaniappan LP,Luft HS. Medicare annual preventive care visits: Use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfoh E, Mojtabai R, Bailey J, Weiner JP, Dy SM. Impact of Medicare Annual Wellness Visits on Uptake of Depression Screening. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen GA, Salloum RG, Hu J, Ferdows NB, Tarraf W. A slow start: Use of preventive services among seniors following the Affordable Care Act’s enhancement of Medicare benefits in the U.S. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015;76:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvin SL, Grandy R, Woodall T, Parlier AB, Thach S, Landis SE. Improved Utilization of Preventive Services Among Patients Following Team-Based Annual Wellness Visits. N C Med J. 2017;78(5):287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler NR, Campbell NL, Pohl GM, Munsie LM, Kirson NY, Desai U, et al. One-Year Effect of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit on Detection of Cognitive Impairment: A Cohort Study. Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 21];66:969–75. Available from: https://onlinelibrary-wileycom.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/doi/pdf/10.1111/jgs.15330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ives DG, Traven ND, Kuller LH, Schulz R. Selection bias and nonresponse to health promotion in older adults. Epidemiology [Internet]. 1994. July [cited 2018 Dec 3];5(4):456–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7918817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones D, Molitor D, Reif J, Baicker K, Bhattacharya J, Deryugina T, et al. What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper series; Cambridge, MA; 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 3]. Available from: http://www.nber.org/workplacewellness. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care Patterns in Medicare and Their Implications for Pay for Performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Annual Wellness Visit: Medicare Coverage of Physical Exams [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-NetworkMLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/AWV_Chart_ICN905706.pdf

- 22.Caminal J, Starfield B, Sánchez E, Casanova C, Morales M. The role of primary care in preventing ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2004. [cited 2018 Dec 17];14(3):246–51. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/articleabstract/14/3/246/528148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y-H, Eberth JM, Probst JC. Ambulatory Care–Sensitive Condition Hospitalizations Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Am Prev Med [Internet]. 2016. October [cited 2019 Feb 26];51(4):493–501. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27374209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation?: Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ [Internet]. 2004. May 1 [cited 2018 May 21];23(3):525–42. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629604000220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilinski A, Hatfield L. Seeking evidence of absence: Reconsidering tests of model assumptions [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2018 Oct 30]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.03273.pdf

- 26.Boulware LE, Marinopoulos S, Phillips KA, Hwang CW, Maynor K, Merenstein D, et al. Systematic Review: The Value of the Periodic Health Evaluation. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2007. February 20 [cited 2019 Jan 16];146(4):289 Available from: http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.7326/0003-4819-146-4200702200-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A Country Doctor. Are your patients uncomfortable with a scripted physical? [Internet]. KevinMD.com; 2015. [cited 2018 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2015/07/are-your-patientsuncomfortable-with-a-scripted-physical.html [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuenca AE. Making Medicare annual wellness visits work in practice. Fam Pract Manag [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Dec 17];19(5):11–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22991904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guessous I, Dash C, Lapin P, Doroshenk M, Smith RA, Klabunde CN. Colorectal cancer screening barriers and facilitators in older persons. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet]. 2010. January 1 [cited 2018 Dec 17];50(1–2):3–10. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/science/article/pii/S0091743509006355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiperneni R, Ganguli I, Ayanian J, Langa K. Reducing Disparities in Healthy Aging Through an Enhanced Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2018;1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowen ME, Bhat D, Fish J, Moran B, Howell-Stampley T, Kirk L, et al. Improving Performance on Preventive Health Quality Measures Using Clinical Decision Support to Capture Care Done Elsewhere and Patient Exceptions. Am J Med Qual [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 18];33(3):237–45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29034685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagholikar KB, MacLaughlin KL, Henry MR, Greenes RA, Hankey RA, Liu H, et al. Clinical decision support with automated text processing for cervical cancer screening. J Am Med Informatics Assoc [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Dec 21];19(5):833–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jamia/articlelookup/doi/10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uy C, Lopez J, Trinh-Shevrin C, Kwon SC, Sherman SE, Liang PS. Text Messaging Interventions on Cancer Screening Rates: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Dec 21];19(8):e296 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, Mercer SL, Wilson KM, DeVinney B, et al. Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Screening for Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancers. Am J Prev Med [Internet]. 2012. July [cited 2018 Dec 21];43(1):97–118. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22704754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.