Abstract

Introduction

The FreeStyle Libre is a flash glucose monitoring (FSL-FGM) system. Compared with finger-prick based self-monitoring of blood glucose, FSL-FGM may provide benefits in terms of improved glycemic control and decreased disease burden.

Methods

Prospective nationwide registry. Participants with diabetes mellitus (DM) used the FSL-FGM system for a period of 12 months. End points included changes in HbA1c, hypoglycemia, health-related quality of life (12-Item Short Form Health Surveyv2 (SF-12v2) and 3-level version of EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D-3L)), a specifically developed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) questionnaire, diabetes-related hospital admission rate and work absenteeism. Measurements were performed at baseline, and after 6 months and 12 months.

Results

1365 persons (55% male) were included. Mean age was 46 (16) years, 77% of participants had type 1 DM, 16% type 2 DM and 7% other forms. HbA1c decreased from 64 (95%CI 63 to 65) mmol/mol to 60 (95%CI 60 to 61) mmol/mol with a difference of −4 (95% CI −6 to 3) mmol/mol. Persons with a baseline HbA1c >70 mmol/mol had the most profound HbA1c decrease: −9 (95% CI −12 to to 5) mmol/mol. EQ-5D tariff (0.03 (95%CI 0.01 to 0.05)), EQ-VAS (4.4 (95%CI 2.1 to 6.7)) and SF-12v2 mental component score (3.3 (95%CI 2.1 to 4.4)) improved. For most, PROMs improved. Work absenteeism rate (/6 months) and diabetes-related hospital admission rate (/year) decreased significantly, from 18.5% to 7.7% and 13.7% to 2.3%, respectively.

Conclusions

Real world data demonstrate that use of FSL-FGM results in improved well-being and decreased disease burden, as well as improvement of glycemic control.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, freestyle libre, flash glucose monitoring, continuous glucose monitoring, patient reported outcome measures

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Use of a flash glucose monitoring system is often associated with a decrease in HbA1c and improved well-being.

What are the new findings?

Users report a considerable decrease in disease burden, reporting, among others, less hypoglycemic episodes and less severe hypoglycemias.

Work absenteeism rate and diabetes-related hospital admissions decrease by two thirds.

Use of a flash glucose monitoring system for 1 year is associated with a significant decrease in HbA1c, with the most pronounced improvement in patients with the worst metabolic control.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

HbA1c as a primary end point is important, but, health-related quality of life (12-Item Short Form Health Surveyv2 and 3-level version of EuroQol 5D) and patient-reported outcome measures, including hypoglycemic episodes, should be considered as possibly even more important end points when assessing the effects of a glucose registering device.

Introduction

A major challenge in the treatment of diabetes mellitus (DM) is to achieve blood glucose levels as close to the physiological as possible without increasing the incidence of hypoglycemia. Ultimately, this approach leads to less microvascular and macrovascular complications and maintenance of health-related quality of life (HRQoL).1 2 Besides insulin administration, a very important component in DM management is accurate glucose monitoring. With self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) based on finger-prick testing of capillary blood glucose, testing is often focused on premeal glucose concentrations, has a limited frequency of use and (largely) relies on patient compliance and motivation. In the last decade, SMBG is supplemented and even supplanted by systems aiming at ‘real time’ continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in the interstitial fluid.

In 2014, the FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitor (FSL-FGM, Abbott) system was introduced. There are some major differences between FGM and other ‘real-time’ CGM systems. Results of the FSL-FGM have to be obtained through a reader actively used by the user instead of data being relayed automatically to a receiver like in most CGMs. Furthermore; the FSL-FGM is calibrated during the fabrication process, and can be used in the upper arm only.3 According to the manufacturer, no further individual calibration is needed (and is also not possible).

Dutch healthcare authorities and insurance companies currently do consider the evidence on scientific and technical aspects to be insufficient to warrant reimbursement for all persons with DM using insulin therapy.4 Still, both the Dutch DM patient organization (Diabetes Vereniging Nederland, DVN) and health professionals involved in DM management would welcome the FSL-FGM as an adjunct to current glucose measurement possibilities. Therefore, the initiative was taken to establish a nationwide prospective registry of persons with DM using FSL-FGM: the FLAsh monitor Registry in The Netherlands (FLARE-NL). This initiative was taken by the DVN in cooperation with Zilveren Kruis (ZK) Achmea (the largest healthcare insurance company in the Netherlands) and the Diabetes Research Center in Zwolle.

The aim of this registry was to collect daily life data from persons with DM using the FSL-FGM system (prior to and during use of FSL-FGM). The current study presents the 1-year results of the FLARE-NL registry.

Patients and methods

Study design and aims

The FLARE-NL registry has a prospective, observational design. The aim of the FLARE-NL registry was to assess the effects of use of the FSL-FGM on clinically relevant end points, with emphasis on HbA1c (primary outcome), and changes in frequency and severity of hypoglycemia, HRQoL, and experienced disease burden over a period of 1 year. Detailed information concerning the FLARE-NL registry has been submitted elsewhere. The study protocol was registered at the Dutch trial register. (www.trialregister.nl (NTR6212)).

Outcomes

When choosing the parameters to be assessed in this study, we strived for a more value-based healthcare approach.5 As such, we did not exclusively study medically defined outcomes, such as changes in HbA1c, but also patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) such as disease burden as experienced by individuals with DM.

Outcomes were the change in HbA1c after 6 months and 1 year of FSL-FGM use, changes in HRQoL as assessed by the 12-Item Short Form Health Surveyv2 (SF-12v2),6 and the 3-level version of EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D-3L),7–9 the number of hypoglycemic episodes in the previous 6 months, number of hospitalizations related to DM (in the previous year), use of test strips (per day), work absenteeism rate (in the previous 6 months), and daily functioning in the previous 6 months (including sports performance). Furthermore, after consulting a patient panel of the DVN, a new questionnaire (‘DVN-PROM’) was formulated to allow assessment of the degree of disease burden experienced by the study population in relation to their DM and especially the need for, and use, and usefulness of (continuous) glucose measurements. This allows a value-based healthcare approach for rating the FSL-FGM system from a user’s perspective. Questions on this list are divided into different categories, some of them descriptive only and others allowing before and after assessment. Although this DVN-PROM has not been validated yet, we included this information as an important outcome in the current study as it may yield relevant information from a user’s perspective.

Population

Adults (≥18 years) with DM using insulin were eligible for participation in the registry. The advice to use the FSL-FGM was not defined by diabetes type, but by indication irrespective of type of diabetes. All subjects were treated by a hospital-based diabetes team, had a health insurance with ZK and belonged to one or more prespecified targets groups.

The definitions of these target groups (indications for FSL-FGM use) were formulated in cooperation with a patient panel and the DVN. These indications were:

Individuals with ‘hypoglycemia unawareness’ and occurrence of moderate-to-severe hypoglycemic episodes despite an average of six or more measurements per day over the past year and intensive support from a diabetes team.

Individuals with unexpected hypoglycemias despite an average of six or more measurements per day over the past year and despite intensive support from a diabetes team.

Individuals treated with insulin who, despite maximal efforts (frequent blood monitoring and proper lifestyle management) and intensive support from their diabetes team, do not reach acceptable glycemic control, as evidenced by a mean HbA1c>70 mmol/mol (8.5%) over the year preceding the inclusion.

Individuals having an occupation, where sensation loss of the fingers by frequent use of home blood glucose meter (HBGM) measurement can cause disability, such as musicians, who under other circumstances would be advised by the healthcare team to perform frequent HBGM daily.

Individuals having an occupation, where even relatively rarely occurring hypoglycaemic episodes would lead to a situation endangering themselves and/or others (eg, bus and lorry drivers, school teachers, sports trainers).

Individuals who at the moment are already eligible for CGM according to Dutch regulations.

Individuals already using FSL-FGM on their own costs, but fit with one of the indications described above.

Individuals who were eligible for more than one target indication were included in a separate group.

Study procedures

The departments of internal medicine and/or diabetes centers of all 95 hospitals in the Netherlands were invited to include individuals based on the inclusion criteria as described above. All these centers were approached by means of a letter, providing them extensive information with regard to the registry. Every participating hospital appointed a single contact person who was responsible for collecting data in the center.

At baseline, informed consent of the intended FSL-FGM user was obtained. Next, the participant received a link to fill out the various questionnaires in the online registry. The healthcare provider filled out the data necessary for the registry. These data included demographics (age, gender), type of DM, indication for participation, level of HbA1c (preceding four values), presence of microvascular (neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy) or macrovascular complications, frequency of HBGM measurement, number of DM-related hospitalizations, number of hypoglycemic events, absenteeism rate and working day losses or reduced functioning due to DM. Furthermore, participants were asked to complete three questionnaires related to HRQoL: SF12v2, EQ-5D-3L, and the DVN-PROM. The questions as asked in the DVN-PROM can be found in online supplementary 1. No cut-off points were formulated beforehand with regards to the possible clinically relevant differences in the questionnaires used.

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp001.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)

After 6 months and 12 months participants and healthcare providers were asked to report HbA1c results from the preceding 6 months. In addition, participants were asked to report changes in the presence of complications, the number of diabetes-related hospitalizations in the previous period, hypoglycemias (<3 mmol/L; (54 mg/dL)) in 3 months before filling out questionnaires, work absenteeism rate (any work-associated period of absence in the prior 6 months) and actual amount of working days absent in prior 6 months, or reduced functioning (including sports performance) due to dysregulation of DM, and the SF-12 v2, EQ-5D-3L, and DVN-PROM.

Statistical analysis

Q-Q plots (detrended) and histograms were used to determine if the tested variable had a normal distribution or not. Descriptive statistics include number (percentage), mean (SD) and median (IQR (25th, 75th centiles)). In order to compare persons with measurements at baseline only and with measurements both at baseline and after 12 months, Fisher’s exact test was used in case of categorical data; and in the case of continuous data, Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used if the data were distributed normally or skewed, respectively.

Linear mixed models with Bonferroni correction were used to calculate estimated values and to test differences between the three moments in time (t=0, t=6 months and t=12 months). Unadjusted and, as a sensitivity analysis, age-adjusted and gender-adjusted linear mixed model analyses were performed. In the present manuscript only the unadjusted results are presented; outcomes of the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted linear mixed model analyses are presented in online supplementary 2.

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp002.pdf (20.5KB, pdf)

A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.25.0. Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

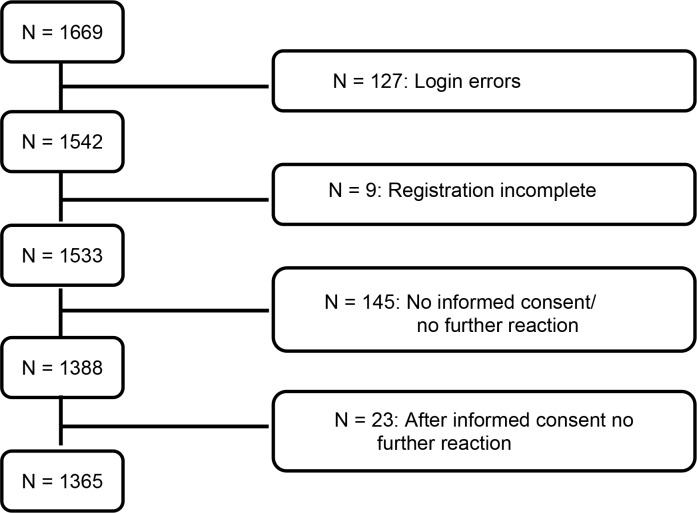

From June 13, 2016 to July 12, 2017 a total of 1669 participants were included from 88 hospitals throughout the Netherlands. Because of errors in the application procedure (n=127), incomplete applications (n=9), refusal to participate in the registry (n=145) or lack of interest in participating in the registry (n=23) 304 subjects were excluded from the current analyses (figure 1), leaving 1365 participating subjects to be analyzed at baseline.

Figure 1.

Patient selection.

As presented in table 1, mean age at baseline of the 1365 (55% male) subjects was 46.1 (16.1) years. Type 1 DM (T1DM) (77.2%) was the most common form of DM while 16.3% had type 2 DM (T2DM) and 6.5% (n=88) had another form of DM such as latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (n=62), maturity-onset diabetes of the young (n=7), or unknown (n=19). Eighty-three per cent of the included subjects were treated with insulin alone. Concerning the different groups of indications for FSL-FGM use, indications 2 (30.0%), 3 (21.5%) and 1 (11.4%) were most common (see table 1). In addition, 20.8% of patients had more than one indication for FSL-FGM use.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 1365 persons with DM included in the registry

| Total | T1DM | T2DM | Other forms of DM | |

| Number (%) | 1365 (100) | 1054 (77.2) | 223 (16.3) | 88 (6.5) |

| Age, years | 46.1 (16.1) | 42.8 (15.5) | 59.9 (10.8) | 52.6 (11.6) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 744 (54.5) | 555 (52.7) | 142 (63.7) | 30 (48.4) |

| Therapy | ||||

| Insulin monotherapy | 1131 (82.9) | 100 (100.0) | 88 (39.5) | 45 (72.6) |

| Insulin and OBGLD | 234 (17.1) | 63 (5.9) | 130 (5.8) | 17 (19.3) |

| Presence of microvascular complications | ||||

| Neuropathy, n (%) | 230 (16.8) | 154 (14.6) | 23 (10.3) | 6 (9.7) |

| Albuminuria, n (%) | 244 (17.9) | 180 (17.1) | 50 (22.4) | 10 (16.1) |

| Retinopathy, n (%) | 247 (18.1) | 199 (18.9) | 39 (17.5) | 6 (9.7) |

| Presence of cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 33 (2.4) | 15 (1.4) | 14 (6.3) | 2 (3.2) |

| PCI, n (%) | 52 (3.8) | 31 (2.9) | 14 (6.3) | 4 (6.5) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 40 (2.9) | 23 (2.2) | 14 (6.3) | 2 (3.2) |

| CABG, n (%) | 37 (2.7) | 23 (2.2) | 11 (4.9) | 2 (3.2) |

| TIA, n (%) | 28 (2.1) | 14 (1.3) | 9 (4.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| CVA, n (%) | 23 (1.7) | 14 (1.3) | 6 (2.7) | 3 (4.8) |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 51 (3.7) | 29 (2.8) | 18 (8.1) | 2 (3.2) |

| Indication for FSL-FGM use | ||||

| Hypoglycemia unawareness 1 | 156 (11.4) | 119 (11.3) | 25 (11.2) | 8 (12.9) |

| Unexpected hypoglycemias 2 | 410 (30.0) | 322 (30.6) | 56 (25.1) | 25 (40.3) |

| HbA1c>70 mmol/mol (8.5%) 3 | 294 (21.5) | 202 (19.2) | 80 (35.9) | 6 (9.7) |

| Unwanted sensation loss of the fingers 4 | 19 (1.4) | 14 (1.3) | 5 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Occupational hazards with hypoglycemia 5 | 57 (4.2) | 39 (3.7) | 11 (4.9) | 4 (6.5) |

| Individuals eligible for CGM 6 | 45 (3.3) | 40 (3.8) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (3.2) |

| Individuals already using FSL-FGM 7 | 100 (7.3) | 76 (7.2) | 14 (6.3) | 6 (9.7) |

| Multiple indications | 284 (20.8) | 242 (23.0) | 30 (13.5) | 11 (17.7) |

Data are presented as numbers (%), means (SD) or medians (25th, 75th centiles).

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting;CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CVA, cerebral vascular event; DM, diabetes mellitus; FSL-FGM, FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring; OBGLD, oral blood glucose lowering drugs;PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; T1DM, type I diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type II diabetes mellitus; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

The baseline characteristics of patients with and without a T12 HbA1c measurement are presented in table 2 to allow comparison of the population missing T12 data with the analyzed population with T12 data present. The patients analyzed at T12 were slightly older and had a slightly lower HbA1c, but differences were minor.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with and without a T12 HbA1c measurement.

| Baseline HbA1c value (n=1362) | P value | |||

| All (n=1362) | T12 missing (n=675) | T12 present (n=687) | ||

| Age | 46.2 (±16.1) | 45.0 (±16.3) | 47.3 (±15.7) | 0.008 |

| Sex (men) | 742 (54.5%) | 382 (56.6%) | 360 (52.4%) | 0.128 |

| DM type | ||||

| 1 | 1051 (77.2%) | 508 (75.3%) | 543 (79.0) | |

| 2 | 223 (16.4%) | 124 (18.4%) | 99 (14.4) | |

| LADA | 62 (4.6%) | 29 (4.3%) | 33 (4.8) | |

| MODY | 7 (0.5%) | 4 (0.6%) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Others | 19 (1.4%) | 10 (1.5%) | 9 (1.3) | 0.357 |

| Indication | ||||

| Hypoglycemia unawareness 1 | 156 (11.5%) | 83 (12.3%) | 73 (10.6% | |

| Unexpected hypoglycemias 2 | 410 (30.1%) | 192 (28.4%) | 218 (31.7%) | |

| HbA1c>70 mmol/mol (8.5%) 3 | 294 (21.6%) | 162 (24.0%) | 132 (19.2%) | |

| Unwanted sensation loss of the fingers 4 | 19 (1.4%) | 9 (1.3%) | 10 (1.5%) | |

| Occupational hazards with hypoglycemia 5 | 57 (4.2%) | 29 (4.3%) | 28 (4.1%) | |

| Individuals eligible for CGM 6 | 43 (3.2%) | 22 (3.3%) | 21 (3.1%) | |

| Individuals already using FSL-FGM 7 | 100 (7.3%) | 41 (6.1%) | 59 (8.6%) | |

| Multiple indications | 283 (20.8%) | 137 (20.3%) | 146 (21.3%) | 0.262 |

| HbA1c T0 | 64.2 (±14.2) 62 (55, 72) |

65.0 (±14.6) 63 (55, 74) |

63.4 (±13.6) 62 (54, 71) |

0.031 0.026 |

Indication: (1) Individuals with ‘hypoglycaemia unawareness’ and occurrence of moderate to severe hypoglycemic episodes despite an average of six or more measurements per day over the past year and intensive support from a diabetes team. (2) Individuals with unexpected hypoglycemias despite an average of six or more measurements per day over the past year and despite intensive support from a diabetes team. (3) Individuals treated with insulin who, despite maximal efforts (frequent blood monitoring and proper lifestyle management) and intensive support from their diabetes team, do not reach acceptable glycemic control, as evidenced by a mean HbA1c>70 mmol / mol (8.5%) over the year preceding the inclusion. (4) Individuals having an occupation, where sensation loss of the fingers by frequent use of HBGM can cause disability, such as musicians, who under other circumstances would be advised by the healthcare team to perform frequent HBGM daily. (5) Individuals having an occupation, where even relatively rarely occurring hypoglycemic episodes would lead to a situation endangering themselves and/or others (eg, bus and lorry drivers, school teachers, sports trainers). (6) Individuals who at the moment are already eligible for CGM according to the Dutch regulations. (7) Individuals already using the FSL-FGM on their own costs, but fit with one of the indications as described above. Subjects who were eligible for more than one target indication were included in a separate group.

CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; DM, diabetes mellitus; FSL-FGM, FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring; HBGM, home blood glucose meter; LADA, Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults; MODY, maturity-onset diabetes of the young; T12, 12 months.

Overall, the HbA1c concentration decreased from 64.1 (95% CI 62.5 to 64.9) mmol/mol before the use of FSL-FGM to 59.2 (95% CI 58.4 to 60.2) mmol/mol after 6 months (p<0.001) and 60.1 (95% CI 59.2 to 61.1) mmol/mol after 12 months (p<0.001) (table 3), resulting in an overall difference in HbA1c over the study period of −4.0 (95%CI −5.5 to 2.6) mmol/mol.

Table 3.

Observed and estimated HbA1c concentrations during the study period

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Difference (12 months) | |

| All patients | ||||

| Observed | 62 (55 to 72) | 58 (52 to 65) | 58 (52 to 66) | |

| Number | 1362 | 790 | 687 | |

| Estimated | 64.1 (62.5 to 64.9) | 59.2 (58.4 to 60.2) ** | 60.1 (59.2 to 61.1) ** | −4.0 (–5.5 to –2.6) |

| T1DM | ||||

| Observed | 62 (54 to 71) | 57 (51 to 65) | 58 (53 to 66) | |

| Number | 1051 | 628 | 543 | |

| Estimated | 63.5 (62.7 to 64.3) | 59.2 (58.2 to 60.1) ** | 60.2 (59.1 to 61.3) ** | −3.3 (–4.9 to –1.7) |

| T2DM | ||||

| Observed | 67 (56 to 78) | 61 (53 to 67) | 62 (53 to 69) | |

| Number | 223 | 114 | 99 | |

| Estimated | 68.2 (66.3 to 70.8) | 61.2 (58.6 to 63.8) ** | 62.0 (59.2 to 64.7) * | −6.2 (–10.3 to –2.1) |

| Other forms of DM | ||||

| Observed | 61 (51 to 71) | 57 (51 to 63) | 55 (50 to 62) | |

| Number | 88 | 48 | 45 | |

| Estimated | 62.2 (59.6 to 64.8) | 56.1 (52.6 to 59.6)* | 56.2 (52.6 to 59.8) * | −6.0 (–11.5 to –0.6) |

Values are presented as numbers, medians (25th, 75th centiles) and estimated means (difference) (95% CI). Data are presented as observed data and estimated data using the linear mixed model. HbA1c concentrations are presented in mmol/mol.

*p<0.05 as compared with baseline; **p<0.001 as compared with baseline.

DM, diabetes mellitus; T1DM, type I diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type II diabetes mellitus.

The decrease in HbA1c was present among all types of DM: −3.3 (95%CI −4.9 to 1.7) mmol/mol for persons with T1DM, −6.2 mmol/mol (95% CI −10.3 to 2.1) for persons with T2DM and −6.0 (95%CI −11.5 to 0.6) mmol/mol for persons with other forms of DM.

When looking at HbA1c changes within different groups of indications of FSL use, maximum impact was present within group 3 with an HbA1c reduction of −8.6 (95% CI −11.8 to to 5.4) mmol/mol. In group 2 and the group with multiple indications for FSL use there was also a decrease in HbA1c, while HbA1c remained stable in groups 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 (table 4).

Table 4.

Observed and estimated HbA1c outcomes in the different groups of indications for FSL-FGM use

| Indication for FSL-FGM use | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Difference (12 months) |

| Hypoglycemia unawareness 1 | ||||

| Observed | 56.6 (50.0 to 63.0) | 55.0 (49.0 to 62.0) | 55.0 (49.2 to 62.0) | |

| Estimated | 57.4 (55.8 to 59.0) | 55.7 (53.6 to 57.9) | 56.9 (54.5 to 59.3) | −0.5 (–4.0 to 3.0) |

| Number | 156 | 86 | 73 | |

| Unexpected hypoglycemias 2 | ||||

| Observed | 58.0 (52.0 to 63.0) | 55.0 (50.0 to 61.0)** | 55.0 (51.0 to 62.0)** | |

| Estimated | 58.0 (57.2 to 58.9) | 55.4 (54.3 to 56.5) | 56.2 (55.0 to 57.3) | −1.9 (–1.1 to –0.2) |

| Number | 410 | 252 | 218 | |

| HbA1c>70 mmol / mol (8.5%) 3 | ||||

| Observed | 76.0 (71.0 to 85.0) | 67 (61.0 to 76.8)** | 67.5 (61.0 to 76.0)** | |

| Estimated | 79.1 (77.6 to 80.5) | 70.0 (67.9 to 72.0) | 70.4 (68.3 to 72.6) | −8.6 (–11.8 to –5.4) |

| Number | 294 | 144 | 132 | |

| Unwanted sensation loss of the fingers 4 | ||||

| Observed | 66.0 (53.0 to 78.0) | 61.0 (51.0 to 71.8) | 67.5 (58.0 to 73.0)* | |

| Estimated | 68.8 (60.0 to 77.5) | 61.6 (49.5 to 73.7) | 65.6 (53.5 to 77.7) | −3.2 (–21.6 to 15.3) |

| Number | 19 | 10 | 10 | |

| Occupational hazards with hypoglycemia 5 | ||||

| Observed | 60.0 (52.5 to 69.0) | 56.0 (49.0 to 62.5)* | 57.4 (49.3 to 65.5) | |

| Estimated | 64.0 (60.3 to 67.7) | 58.0 (53.4 to 62.6) | 58.0 (52.7 to 63.3) | −5.9 (–13.9 to 2.0) |

| Number | 57 | 37 | 28 | |

| Individuals eligible for CGM 6 | ||||

| Observed | 59.0 (51.0 to 67.0) | 57.0 (48.5 to 62.0) | 61.0 (51.0 to 65.5) | |

| Estimated | 59.1 (55.6 to 62.5) | 57.2 (52.7 to 61.7) | 59.1 (54.2 to 61.1) | 0.1 (–7.3 to 7.5) |

| Number | 52 | 43 | 21 | |

| Individuals already using FSL-FGM 7 | ||||

| Observed | 58.5 (53.3 to 67.0) | 56.0 (51.5 to 62.0) | 56.0 (52.0 to 63.0) | |

| Estimated | 60.4 (58.3 to 62.5) | 57.5 (55.0 to 60.1) | 58.2 (55.4 to 60.9) | −2.2 (–6.4 to 2.0) |

| Number | 100 | 65 | 39 | |

| Multiple indications | ||||

| Observed | 63.0 (54.0 to 71.0) | 58.0 (51.0 to 65.0)** | 59.0 (52.0 to 66.0)** | |

| Estimated | 63.2 (61.8 to 64.5) | 59.0 (57.2 to 60.7) | 59.5 (57.7 to 61.4) | −3.6 (–6.5 to –0.8) |

| Number | 283 | 171 | 146 | |

Values are presented as numbers, medians (25th, 75th centiles) and estimated means (difference) (95% CI). Data are presented as observed data and estimated data using the linear mixed model. HbA1c concentrations are presented in mmol/mol.

*p<0.05 as compared with baseline; **p<0.001 as compared with baseline. Detailing of indications: see text and Table.

CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; FSL-FGM, FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring.

Data concerning the course of indices of disease burden are presented in table 5. Both the SF-12v2 (mental component score) as well as the EQ-5D-3L (scores divided into assessment of the answers to the five questions and the health evaluation using a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS)) showed significant improvements in outcomes, whereas the SF-12v2 (physical component score) remained unchanged.

Table 5.

Changes in indices of disease burden

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Difference (12 months) | ||

| SF-12v2 | |||||

| PCS | Observed | 50.6 (44.7 to 54.1) | 51.6 (45.9 to 54.7)** | 51.2 (45.8 to 54.7)* | |

| Number | 1360 | 1055 | 680 | ||

| Estimated | 48.8 (48.4 to 49.2) | 49.6 (49.2 to 50.1) | 49.4 (48.8 to 49.9) | 0.6 (−0.3 to 1.5) | |

| MCS | Observed | 49.6 (40.6 to 56.4) | 51.2 (43.4 to 57.8)* | 52.6 (45.1 to 58.6)* | |

| Number | 1360 | 1055 | 685 | ||

| Estimated | 48.0 (47.5 to 48.6) | 50.0 (49.4 to 50.7) | 51.3 (50.5 to 52.1) | 3.3 (2.1 to 4.4) | |

| EQ-5D-3L | |||||

| Dutch Tariff | Observed | 0.84 (0.77 to 1.00) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.00)* | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.00)* | |

| Number | 1360 | 1056 | 685 | ||

| Estimated | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.4) | 0.86 (0.85 to 0.87) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.87) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | |

| EQ-VAS | Observed | 72 (61 to 81) | 76 (67 to 82)* | 77 (69 to 85)* | |

| Number | 1361 | 1057 | 685 | ||

| Estimated | 68.2 (67.1 to 69.2) | 71.5 (70.3 to 72.8) | 72.6 (71.1 to 74.2) | 4.4 (2.1 to 6.7) | |

| Hypoglycemic events | |||||

| Presence of any hypoglycemic events in past 6 months, yes/no, n (%) | 1271 yes (93.5) n=1360 |

76 yes (92.4)* n=1056 |

624 yes (91.0)* n=686 |

||

| Number of hypoglycemic events in past 6 months, n (%) | Observed | 30 (10 to 72) | 30 (12 to 72) | 26 (11 to 70)* | |

| Number | 1266 | 972 | 623 | ||

| Estimated | 54.0 (50.1 to 58.0) | 54.8 (50.4 to 59.3) | 57.4 (51.9 to 63.0) | 3.4 (−4.9 to 11.7) | |

| Use of strips | |||||

| Strips per day, n (%) | Observed | 6 (4 to 8) | 5 (1 to 7)* | 3 (0 to 6)* | |

| Number | 1350 | 1049 | 685 | ||

| Estimated | 6.1 (5.9 to 6.3) | 5.0 (4.8 to 5.3) | 4.0 (3.7 to 4.3) | −2.2 (−2.6 to –1.7) | |

| Hospital admissions | |||||

| Hospital admissions in past 12 months, yes, n (%) | 187 (13.7) | 97 (7.1)** | 32 (4.7)** | ||

| Number | 1365 | 1049 | 681 | ||

| Number of hospital admissions, n | Observed | 1.0 (1.0 to 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0 to 2.5) | 1.0 (1.0 to 2.0) | |

| Number | 187 | 97 | 32 | ||

| Estimated | 0.33 (0.24 to 0.42) | 0.30 (0.19 to 0.40) | 0.09 (−0.03 to 0.22) | −0.24 (−0.43 to –0.04) | |

| Loss of working days | |||||

| Absenteeism rate in past 6 months, yes, n (%) | 251 (18.5) | 104 (9.8)* | 53 (7.7)* | ||

| Number | 1360 | 1056 | 686 | ||

| Number of working days lost in last 6 months | Observed | 7 (3 to 25) | 9 (3 to 35) | 10 (3 to 44) | |

| Number | 247 | 95 | 50 | ||

| Estimated | 34.6 (27.2 to 42.0) | 38.2 (26.5 to 50.0) | 44.4 (28.1 to 60.8) | 9.8 (−12.1 to 31.8) |

Values are presented as numbers (%), medians (25th, 75th centiles) and estimated means (difference) (95% CI). Data are presented as observed data and estimated data using the linear mixed model.

*p<0.05 as compared with baseline; **p<0.001 as compared with baseline.

EQ-5D-3L, 3-level version of EuroQol 5D; EQ-VAS, EQ-visual analogue scale; MCS, Mental Component Score; PCS, Physical Component Score; SF-12v2, 12-Item Short Form Health Surveyv2.

During 1-year use of the FSL-FGM the percentage of patients experiencing any hypoglycemic events decreased from 93.5% to 91.0% at 12 months (p<0.05). The percentage of DM-related hospital admissions decreased from 13.7% to 4.7% (p<0.05). There was also a decrease in work absenteeism rate over time: from 18.5% to 7.7% (p<0.05). Finally, a decrease in the number of test strips used per day for SMBG was reported: −2.2 (95%CI −2.6, to 1.7) per day.

In online supplementary 3, data of indices of disease burden are shown for T1DM and T2DM separately. As presented in online supplementary 2, besides a significant increase in the physical component score of the SF-12v2 in the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted analyses as compared with the unadjusted data, there were no relevant differences in outcomes after adjustment for age and gender.

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp003.pdf (34KB, pdf)

A complete list of the questions asked in the DVN-PROM is shown in online supplementary 1. Selected results are shown in box 1. Results are positive, for example, on aspects as self-reported (severe) hypoglycemia incidence and measuring before driving, a better understanding of glucose fluctuations, a more active role in adjusting insulin doses, and less worries for house mates and family members.

Box 1. Selected results of Diabetes Vereniging Nederland patient-reported outcome measures (DVN-PROM) comparing baseline to 1 year.

No impediment to measure glucose in the presence of strangers: from 34.7% to 81.7% (p<0.001).

Deciding what to do best after measuring glucose: improvement from 22.9% to 56.7% (p<0.001).

Glucose measurement in a poorly illuminated space is achievable/workable: from 49.4% to 88.6% (p<0.001).

Measuring glucose before participating in traffic as a driver: usually and always: from 40.9% to 75.4% (p<0.001).

37% reports sporting and exercising more frequently.

95% reports a better understanding of his or her glucose fluctuations.

77% experiences less hypoglycemias.

78% experiences less severe hypoglycemias.

92% finds it easier to regulate glucose around a meal.

80% adjusts insulin doses more frequently.

62% reports that house mates and family members are less worried about their diabetes.

During the study period, 86 (6.3%) persons reported their reason to stop with FSL-FGM use. Reasons for stopping FSL-FGM were high costs (54.7%), insufficient convenience (7.0%), inability to control blood glucose concentrations (3.5%), a combination of these factors (2.4%) or other reasons (32.6%). It should be noted that the majority of people ceasing the use of the FSL-FGM did not provide an official reason for their discontinuation (no obligatory filling out of data was required since this was a real life registry without any means of enforcement). An unknown number of users ceased using the device due to an allergic reaction on the glue.

Discussion

The FLARE-NL registry provides real life data on the effects of 1-year use of the FSL-FGM. A significant decrease in the primary outcome measure, HbA1c, was observed, with the most pronounced decreases in subjects with the highest baseline HbA1c.

Possibly more important from a patient and socioeconomic point of view, are the improvements in HRQoL, the decrease in number of patients experiencing hypoglycemic events, and the effects on work absenteeism rate and diabetes-related hospital admissions. Despite the fact that the present version of the FSL-FGM does not contain automated alarms or a direct connection with an external insulin infusion pump, generally the device is well appreciated by the users in this study as reflected in the answers to the non-validated DVN-PROM.

The patients included in the analysis at T12 were slightly older and had a slightly lower HbA1c compared with the group with missing T12 information. However, given the very small differences (see table 2), we do not think that the outcomes found in this study are biased by selective attrition.

In the whole analyzed group, HbA1c decreased moderately with −4.0 (95% CI −5.5 to to 2.6) mmol/mol. Part of this rather moderate effect might be due to the already relatively low baseline HbA1c with a mean of 64 mmol/mol in subjects already trying to comply to a rather intensive control and intervention scheme before starting with the FSL-FGM. This may be emphasized by the fact that the largest HbA1c decrease is present in subjects with the highest baseline HbA1c, although in this last group a regression to the mean effect cannot be completely excluded. Furthermore, the moderate overall effect on HbA1c could well be explained by the fact that multiple indications (including frequent hypoglycemic events) were included for FSL-FGM use. Indeed, analyses among the different groups of FSL-FGM users demonstrate that, for instance, there was no decrease of HbA1c among patients in group 1 (‘hypoglycaemia unawareness’) while a profound HbA1c decrease of −8.6 (95% CI −11.8 to 5.4) mmol/mol was present in group 3 (‘inadequate glycaemic control’).

The reported HbA1c change in the present study is rather comparable to the reported changes in other studies. For instance, meta-analysis of 363 persons with T2DM using insulin (baseline HbA1c 74 mmol/mol) by Kroeger et al 10 demonstrated a HbA1c decrease of 10 mmol/mol after at least 3-month use of the FSL-FGM. In addition, among 900 persons with T1DM with baseline HbA1c≥58 mmol/mol FSL-FGM a median decrease of −7 mmol/mol was noted during a median study period of 245 days.7 In accordance with our study, a relationship between baseline HbA1c and rate of decrease was noted (r= −0.479, in Kroeger’s study, vs r=−0.494 in our study). The current study adds to these data by providing data on the effectiveness of FSL-FGM among different types of DM and indications for FSL-FGM use.

As for experienced disease burden, virtually all outcomes showed positive results.

The improvements in the SF-12v2 Mental Component Score, the EQ5D-3L were significant. Of course, with the relatively small differences found, discussion may remain with regard to the clinical relevance as opposed to significance.

With regard to differences between persons with T1DM and T2DM, direction of change was comparable for T1DM and T2DM in most indices of disease burden and quality of life. A rather large difference is noted in the amount of subjects reporting any hypoglycemias: this is considerably lower in subjects with T2DM, and there was no trend to decrease in this study. Grade of significance, in particular among persons with T2DM, is somewhat variable; trends are largely comparable, but with smaller group sizes, significance is not reached.

In our opinion, the reported effect of less hypoglycemic events combined with a neutral effect or a (slight) decrease in HbA1c is significant and relevant from a user point of view. For all involved parties (users, healthcare professionals, and healthcare insurance companies), the observed lower diabetes-related hospital admission rate can be considered quite a positive result. This finding, based on self-reported data, is slightly in contrast with the findings in the study of Tyndall et al,11 where hospital admission rates show a tendency to increase. In a follow-up study (presently in progress), we will try to confirm or refute this finding by analyzing the health insurance company data. Work absenteeism rate dropped, even when analyzing the total population, in which part of the participants are not employed (anymore). When restricting the analysis to people 65 years or less of age (as a surrogate measure for employment, n=1186), the drop in absenteeism rate was still present: 20.4% to 8.3% (p<0.001).

While fully acknowledging the fact that we used the non-validated (‘DVN-PROM’) questionnaire, most patients and healthcare workers may recognize the questions as being rather representative for daily life barriers, impediments and incidents.

As recently stated by Poole, patient-experience data are vitally important to both large healthcare organizations and small medical practices.12 Obstacles for proper interpretation and chances on bias are plentiful, but still the presented results show outcomes which are important from patient’s perspective in value-based healthcare.

Moreover, anxiety (which can be the result of the perceived disease burden, but definitely is also associated with the burden of depression) is correlated to high-cost resource use, at least in T2DM. Decreasing anxiety by decreasing disease burden might be a factor contributing to diminished medical expenditure.13

As can be expected, there are also side effects of the devices used, among others, costs, unreliable data, and allergies. Besides the reported reasons to cease FSL-FGM use, several patients reported (sometimes severe) skin reactions. This seems to be due to the type of glue used to attach the FSL-FGM to the skin.14

Strengths of our study are the large study population (the largest data available in literature to date), the participation of the majority of the Dutch hospital organizations, and the inclusion of both clinical and societal aspects when analyzing the effects of the use of the FSL-FGM, including the PROM DVN-PROM. Furthermore, aspects with regards to quality of life and disease burden are included as well.

Definitely, limitations are present as well. First, this study can be described as a prospective intervention study without a control group and a multitude of missing data. To a large extent, the obtained data are patient-reported; recall bias may be present and the verity of a substantial part of the patient-reported information cannot be controlled through other means. In addition, participants had to finance half of the costs of the FSL-FGM themselves; this inevitably will contribute to bias, since the participants probably will be more affluent than the average DM population, at least in the Netherlands. Many users dropped out and did not report back even after 6 months, without reporting a reason for the discontinuation in the register. Since participation for filling out the various questionnaires was voluntary, the dropout was considerable for that reason as well, especially after 12 months.

In general and as already mentioned, many data were missing in this real life database. Efforts to gain more information from the participants and hospitals only partly succeeded. Since the participation was voluntary, no other means to improve data completeness were applied. Finally, it should be mentioned that one of the questionnaires (the ‘DVN-PROM’) used in this study is not validated. Although the DVN-PROM was non-validated, we still find the results valuable and useful as it represents the results of collaboration with a DM patient organization and FSL-FGM users, and the questions asked are very recognizable for both caregivers and patients.

Several steps are already taken to remedy part of the limitations. In a follow-up study we plan to combine the data as present in the current FLARE-NL registry with the reimbursement data of the healthcare insurance company to assess the actual effects of FSL-FGM on healthcare costs (as represented by reimbursement data). This will allow an analysis with regards to diabetes-related hospital admission rate, but also allows for other comparisons. Anonymization and combining of these databases is outsourced in order to prevent any privacy issue.

Furthermore, questionnaires will be sent out again 2 years after starting with the FSL-FGM to assess the effects of ceasing the use of the FSL-FGM.

Conclusions

It can be concluded, that a large proportion of persons with DM, using FSL-FGM, experiences positive effects on a wide range of outcome parameters. HbA1c levels decreased, while, according to their own reporting, patients experienced a lower absenteeism rate, and less diabetes-related hospital admission rates. Furthermore, they reported less and less severe hypoglycemias, and a more active role toward treatment and treatment changes. Of course, these outcomes should not all be taken at face value. Acknowledging the several limitations of this study, in our opinion the results are still convincing enough to allow the general conclusion that the FSL-FGM is a valuable addition to treatment options for specific target groups of patients with DM, irrespective of the type of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeannette Braakman, Joep Dille, Anouk Damman, Clarinda Schreuder and Dr. Klaas H. Groenier for their support and valuable comments on the manuscript. The authors also thank all the participants for allowing use of their data for the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF wrote protocol, performed the actual research, analyzed data, wrote manuscript, contributed to discussion. PvD, JM and ME analyzed data, contributed to discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript. EB and RS contributed to discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript. RG and HB contributed to protocol and discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by an unconditional grant from the Stichting Achmea Gezondheidzorg (SAG). The SAG is an innovation fund of health insurance company Zilverenkruis. The manufacturer of the FreeStyle Libre (Abbott) did not provide any finances for the proposed study and did not have any influence on study design, nor on definition of the target groups or the study objectives.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: The initiative of a registry was taken by the Diabetes Research Center in Zwolle in cooperation with Zilveren Kruis (ZK) Achmea (the largest healthcare insurance company in the Netherlands) and DVN (Dutch diabetes patient Associsation). After consulting a patient panel of the DVN, a new questionnaire (‘DVN-PROM’) was formulated to allow assessment of the degree of disease burden experienced by the study population in relation to their DM and especially the need for, and use, and usefulness of (continuous) glucose measurements.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Isala. Furthermore, the Medical Ethical Committee decided to provide a waiver for this study (decision METC 16.0346).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). The Lancet 1998;352:854–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07037-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund J-YC, et al. . Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2643–53. 10.1056/NEJMoa052187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fokkert MJ, van Dijk PR, Edens MA, et al. . Performance of the FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring system in patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diab Res Care 2017;5:e000320 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministerie van Volksgezondheid W en S Standpunt Flash Glucose Monitoring (FreeStyle Libre) bij diabetes - Standpunt - Zorginstituut Nederland [Internet], 2018. Available: https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/standpunten/2018/04/30/standpunt-flash-glucose-monitoring-freestyle-libre-bij-diabetes [Accessed 19 Jun 2019].

- 5. ICHOM | Diabetes Standard Set | Measuring Outcomes [Internet] ICHOM – International Consortium for health outcomes measurement. Available: https://www.ichom.org/portfolio/diabetes/ [Accessed 19 Jun 2019].

- 6. Hagell P, Westergren A, Årestedt K. Beware of the origin of numbers: standard scoring of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures distorts measurement and score interpretations. Res Nurs Health 2017;40:378–86. 10.1002/nur.21806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoeymans N, Lindert Hvan, Westert GP. The health status of the Dutch population as assessed by the EQ-6D. Qual Life Res 2005;14:655–63. 10.1007/s11136-004-1214-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Reenen M, Oppe M. EQ-5DL-3L user guide basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-3L instrument 2015.

- 9. Lammers LM, Stalmeijer PFM, McDonnell J, et al. . Kwaliteit van leven meten in economische evaluaties: Het Nederlands EQ-5D-tarief. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005:1574–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kroeger J, Fasching P, Hanaire H. 99-LB: meta-analysis of three real-world, chart review studies to determine the effectiveness of FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring system on HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2019;68:99-LB 10.2337/db19-99-LB [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tyndall V, Stimson RH, Zammitt NN, et al. . Marked improvement in HbA1c following commencement of flash glucose monitoring in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2019;62:1349–56. 10.1007/s00125-019-4894-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poole KG. Patient-Experience Data and Bias — What Ratings Don’t Tell Us. New England Journal of Medicine 2019;380:801–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1813418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iturralde E, Chi FW, Grant RW, et al. . Association of anxiety with high-cost health care use among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1669–74. 10.2337/dc18-1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herman A, de Montjoye L, Tromme I, et al. . Allergic contact dermatitis caused by medical devices for diabetes patients: a review. Contact Dermatitis 2018;79:331–5. 10.1111/cod.13120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp001.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp002.pdf (20.5KB, pdf)

bmjdrc-2019-000809supp003.pdf (34KB, pdf)