Abstract

Sweet disease (SD) is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterised by fever, cutaneous erythematous plaques and aseptic neutrophilic infiltration of various organs. Neuro-Sweet disease (NSD) is a known rare central nervous system complication of SD. We describe a case of a 39-year-old Japanese woman who was diagnosed as NSD associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. She was successfully treated with systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Keywords: headache (including migraines), pathology, sjogren's syndrome

Background

Sweet disease (SD) is known as an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Aseptic neutrophilic inflammation may also occur in other organs.1 Neuro-Sweet disease (NSD) is a variant of SD, which involves the central nervous system, and is most common in Asian patients.2 Encephalitis and meningitis are common neurological manifestations of NSD. Several inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and rheumatic arthritis, have been reported to be associated with SD3 NSD is a rare complication of SD and no cases of NSD with Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) have previously been reported. Therefore, we report the first case of NSD associated with SS in a Japanese woman.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old woman presented with fever, severe headache, vomiting and painful rashes. Skin lesions were detected on her extremities and trunk. In addition, she had experienced 1 year of dry mouth. She did not take any medicine. At hospital admission, her temperature was 39.2℃ and her heart rate was 103/s.

On clinical examination, she had neck stiffness. There were no changes in consciousness. The patient’s tendon reflexes were normal, and no pathological reflexes were noted. She had no abnormal ocular signs, including uveitis and episcleritis. Multiple tender erythema nodosum were detected on her extremities and trunk (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multiple erythema nodosum are present on the left arm.

Investigations

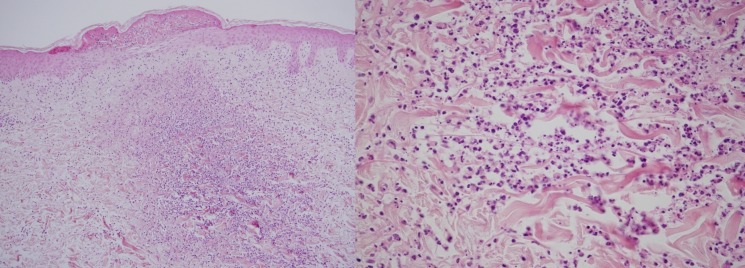

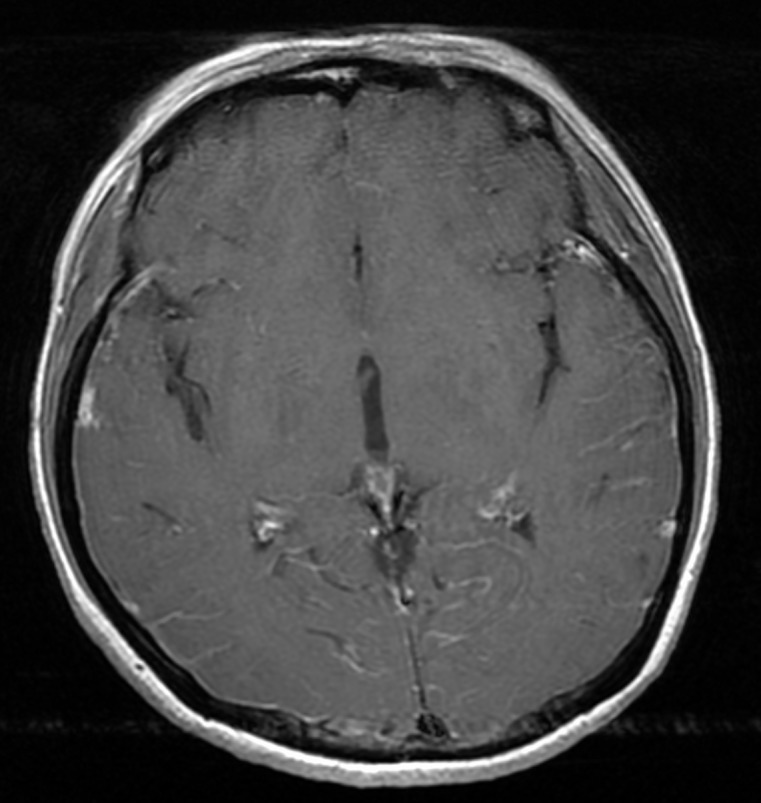

At admission, laboratory examinations revealed leucocytosis (8.3×109/L) with a neutrophil count of 7.3×109/L. There was also an increased C reactive protein level of 13.7 mg/dL (reference <0.3 mg/dL) and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (59 mm/h). Antinuclear antibody titre was 640, and anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La antibodies were both positive. HLA-B51 was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a total count of 21 cells/µL (reference <5 cells/µL), comprising 14 cells/µL mononuclear cells and 7 cells/µL polynuclear cells. CSF glucose level was 69 mg/dL (reference range: 45–80 mg/dL; serum glucose level: 96 mg/dL (reference range: 70–110 mg/dL)) and CSF total protein level was 41 mg/dL (reference range: 15–45 mg/dL). CSF culture was negative and PCR analysis for herpes simplex virus was negative. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted axial images showed meningeal enhancement extending from the right temporal lobe to the occipital lobe (figure 2). A skin biopsy of an erythema nodosum lesion on the left arm revealed predominantly neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis (figure 3), but no vasculitis was noted. Based on the presence of dry mouth and the positive anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La, we performed a labial salivary gland biopsy. This revealed focal lymphocytic sialadenitis with predominant lymphocytic infiltration, which was compatible with SS.3

Figure 2.

Axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images show increased leptomeningeal contrast enhancement in both temporal lobes and the right occipital lobe.

Figure 3.

A skin biopsy specimen shows predominantly neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis. There are no findings of necrotising vasculitis (H&E staining, (a) ×100, (b) ×20).

The patient was diagnosed with SS based on the American College of Rheumatology Classification for SS criteria.4 She met the required two of three criteria with positive anti-SS-A and-SS-B, as well as her labial salivary gland biopsy findings.

The diagnosis of SD was made utilising the criteria outlined by Von den Driesch.1 The two SD major criteria were fulfilled by the abrupt onset of typical skin lesions and neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis and three minor criteria were met by fever, laboratory findings of inflammation and the coexistence of an autoimmune disorder. In addition, the fourth minor criterion was achieved after she experienced and excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids.

The diagnosis of NSD was made using clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by Hisanaga et al.5 The patient had three major features, including neurological and dermatological involvement, and the absence of features of Behcet’s disease. Furthermore, we confirmed that HLA-B51 was negative. These features were all compatible with probable NSD.

Within the scope of our investigations, no findings suggestive of malignancy or infectious disease were detected. She was not pregnant and had no history of drug use.

Differential diagnosis

Neuro-Behcet’s disease, another systemic inflammatory disease, involving the central nervous system, skin and mucosa, is the most important differential diagnosis when considering NSD. This is due to the common overlapping clinical features of both Behcet’s disease and SD. However, in this case, there were no typical physical findings of Behcet’s disease, such as oral aphthae, genital ulcer and uveitis. In addition, the finding of skin biopsy did not show vasculitis and thrombophlebitis which are also seen in Behcet’s disease. Therefore, we excluded neuro-Behcet’s disease.

Treatment

Prednisolone was administered. The first dose was 50 mg/day for 7 days. Her symptoms, such as fever, headache and rash, gradually improved with a decrease in her serum inflammatory makers. Thereafter, the dose was tapered by 10 mg each week while her response was observed. She remained stable on 30 mg/day and tapering was continued at a decrease of 10 mg every 2 weeks.

Outcome and follow-up

She was discharged on day 45. She required no further systemic corticosteroids during her follow-up as an outpatient. During the systemic glucocorticoid therapy, she did not have any major side effects of taking the therapy. The recurrence of NSD has not been detected for 7 years.

Discussion

NSD was first described in 1999 by Hisanaga et al.5 They reported a case of a 32-year-old Japanese man with a recurrent steroid-responsive encephalitis associated with SD. In total, 70 patients with NSD have been described up to date.3 6 NSD is rare and more cases have been reported in Asians than Caucasians.3

The most common neurological manifestation of SD is thought to be encephalitis or meningitis. Although altered consciousness and headache are common symptoms, a wide range of neurological manifestations can occur. Therefore, the diagnosis of NSD is considered challenging. Our case had headache and neck stiffness with no altered consciousness. We confirmed the presence of meningitis based on CSF analysis and MRI findings.

SD is classically divided into types: classical or idiopathic, drug-induced and malignancy-associated.1 Classical SD constitutes the majority of cases and is often associated with infection, inflammatory disease or pregnancy.2 We thought our case was classical SD because she was diagnosed as having SS with no significant history of previous medication use or malignancy. In terms of conditions that are frequently associated with classical SD, she did not have any infection and was not pregnant. Therefore, we considered this a case of classical SD associated with SS. To our knowledge, there have been only six case reports of SD associated with SS.7–10 However, this is the first reported case of NSD associated with SS.

The aetiology of SD remains unclear. Three proposed phenomena are thought to contribute to the development of SD including hypersensitivity reaction, cytokine dysregulation and genetic susceptibility.

Regarding hypersensitivity reaction, an immune reaction to bacteria, tumour cells or other antigens stimulate the production of cytokines that promote neutrophil activation and infiltration, which leads to the development of SD.11

Findings from several studies indicate that a number of cytokines and chemokines, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukins (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6 and IL-8) play a key role in the pathogenesis of SD.3 12 13 Serum levels of these cytokines and chemokines are elevated in patients with SD. Therefore, cytokine dysregulation is considered to be associated with the development of SD.

In terms of genetic susceptibility, HLA-B54 and mutations in the MEFV gene are said to have an association with SD.14 15

Although our case showed a good response to systemic glucocorticoid therapy and there has been no recurrence to date, nearly half of NSD cases reported by 2015 experienced the recurrence of some neurological manifestations.2 For the risk of recurrence, NSD patients should be carefully followed up.

Prompt recognition of the possible neurological complications of SD is essential to avoiding delayed or unnecessary treatment for other forms of meningoencephalitis.

Learning points.

In patients with Sweet’s disease and neurological symptoms, consider neuro-Sweet’s disease.

Consider and evaluate for comorbidities and coexisting diseases including inflammatory conditions, autoimmune disease, infection and malignancy.

Neuro-Behcet’s disease is the most important differential diagnosis in a patient with neurological and cutaneous findings suggestive of Sweet’s disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinical staff of the Japan Self-Defense Forces Central Hospital for their assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: TK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. YY and HT assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigate and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. von den Driesch P. Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:535–56. 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70215-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Agnoletti AF, et al. Neuro sweet syndrome: a systematic review. A rare complication of sweet syndrome. Acta Neurol Belg 2017;117:33–42. 10.1007/s13760-016-0695-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen PR. Sweet's syndrome – a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:34 10.1186/1750-1172-2-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell L, et al. New Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: A data-driven expert-clinician consensus approach within the SICAA Cohort. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:475–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hisanaga K, Hosokawa M, Sato N, et al. “Neuro-Sweet disease“:Benign recurrent encephalitis with neutrophiloic dermatosis. Acrh Neurol 1999;56:1010–3. 10.1001/archneur.56.8.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oka S, Ono K, Nohgawa M. Successful treatment of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion associated with neuro-Sweet disease in myelodysplastic syndrome. Intern. Med. 2018;57:595–600. 10.2169/internalmedicine.9215-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bianconcini G, Mazzali F, Candini R, et al. [Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) associated with Sjögren's syndrome. A clinical case]. Minerva Med 1991;82:869–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vatan R, Ragnaud J. Association of primary Gougerot- Sjögren’s syndrome and Sweet syndrome. Apropos of a case (letter). Rev Med Intern 1997;18:734–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osawa H, Yamabe H, Seino S, et al. A case of Sjögren's syndrome associated with sweet's syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 1997;16:101–5. 10.1007/BF02238773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mrabet D, Saadi F, Zaraa I, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome and lymph node tuberculosis. BMJ Case Reports 2011:2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Voelter-Mahlknecht S, Bauer J, Metzler G, et al. Bullous variant of sweet's syndrome. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:946–7. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kimura A, Sakurai T, Koumura A, et al. Longitudinal analysis of cytokines and chemokines in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with neuro-Sweet disease presenting with recurrent encephalomeningitis. Intern. Med. 2008;47:135–41. 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White JML, Mufti GJ, Salisbury JR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:206–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takahama H, Kanbe T. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: a case showing HLA B54, the marker of sweet's syndrome. Int J Dermatol 2010;49:1079–80. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jo T, Horio K, Migita K, et al. Sweet's Syndrome in Patients with MDS and MEFV Mutations. N Engl J Med 2015;372:686–8. 10.1056/NEJMc1412998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]