Abstract

Background and study aims A new hemostatic adhesive powder (UI-EWD) was developed to reduce high rebleeding rates and technical challenges associated with application of currently available hemostatic powders. The aim of the current study was to assess performance of UI-EWD for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB).

Patients and methods A total of 56 consecutive patients that received UI-EWD monotherapy for endoscopic hemostasis due to NVUGIB were retrospectively reviewed. Main study outcomes were success rates with immediate hemostasis and rebleeding within 30 days. Outcomes were analyzed by reviewing patient medical records.

Results Etiologies of bleeding were: post-endoscopic therapy bleeding in 46 (82.1 %), peptic ulcer in 8 (14.3 %), tumor in 1 (1.8 %), and other in 1 (1.8 %). UI-EWD was successfully applied at bleeding site in all cases. The success rate of immediate hemostasis was 96.4 % (54/56), and the 30-day rebleeding rate among patients that achieved immediate hemostasis was 3.7 % (2/54). No adverse event related to use of UI-EWD occurred.

Conclusion UI-EWD was found to have a high immediate hemostasis success rate in NVUGIB when used as monotherapy and showed promising results in terms of preventing rebleeding.

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is encountered commonly in emergency departments and can result in hospital admission and significant morbidity and mortality 1 . Currently, endoscopic hemostasis is accepted as a first-line treatment modality for management of UGIB and has been demonstrated to effectively reduce rebleeding, surgical intervention, and mortality rates 2 . Endoscopic methods commonly used to control bleeding are injection or thermal or mechanical devices. However, endoscopic management of UGIB is often challenging due to anatomic position or a diffuse bleeding lesion, and as a result, endoscopic hemostasis has a failure rate of 8 % to 15 % 3 . In addition, success of endoscopic hemostasis is dependent on operator skill, thus success rates may be lower when endoscopic hemostasis is performed by inexperienced hands 4 . In view of these challenges, more effective and straightforward endoscopic hemostasis modalities are required.

Hemostatic powders have been developed recently for endoscopic hemostasis and reportedly have excellent immediate hemostatic rates (93 % – 98 %) in UGIB patients 5 6 . These powders have the advantage of being easy to use because application does not require accurate spraying at bleeding sites, which are frequently difficult to visualize in endoscopic view and to approach. For these reasons, clinicians not experienced at endoscopic hemostasis are expected to be able to use hemostatic powders in emergency cases. However, recently developed powders have high rebleeding rates (33 % – 49 %) 7 8 , and their applications may be demanding due to, for example, clogging of the delivery catheter and impaired visualization due to formation of powder-in-air suspensions.

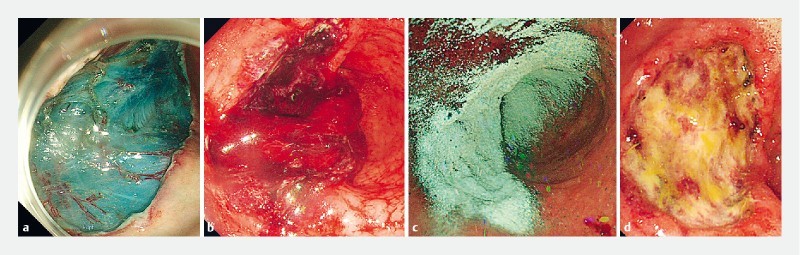

To address limitations of available hemostatic powders, we developed a hemostatic adhesive powder (UI-EWD; Fig. 1 ) composed of a biocompatible natural polymer produced using aldehyde dextran and succinic acid modified ε-poly (l-lysine), which is immediately converted to a highly adhesive hydrogel in the presence of water. The reaction between UI-EWD and water leads to formation of a Schiff base and to multiple crosslinks within the hydrogel and between it and tissues. UI-EWD can be delivered to bleeding loci without catheter clogging or forming powder-in-air suspensions by liquid coating technology using a fluidized bed granulator 9 . Clinically, UI-EWD has been shown to achieve high immediate hemostasis rates and low rebleeding in patients with UGIB refractory to conventional endoscopic procedures 9 . To obtain further information on practical performance of UI-EWD, the current study was undertaken to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of UI-EWD monotherapy for treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB).

Fig. 1.

Images of a UI-EWD and b spraying devices.

Patients and methods

Study design and study population

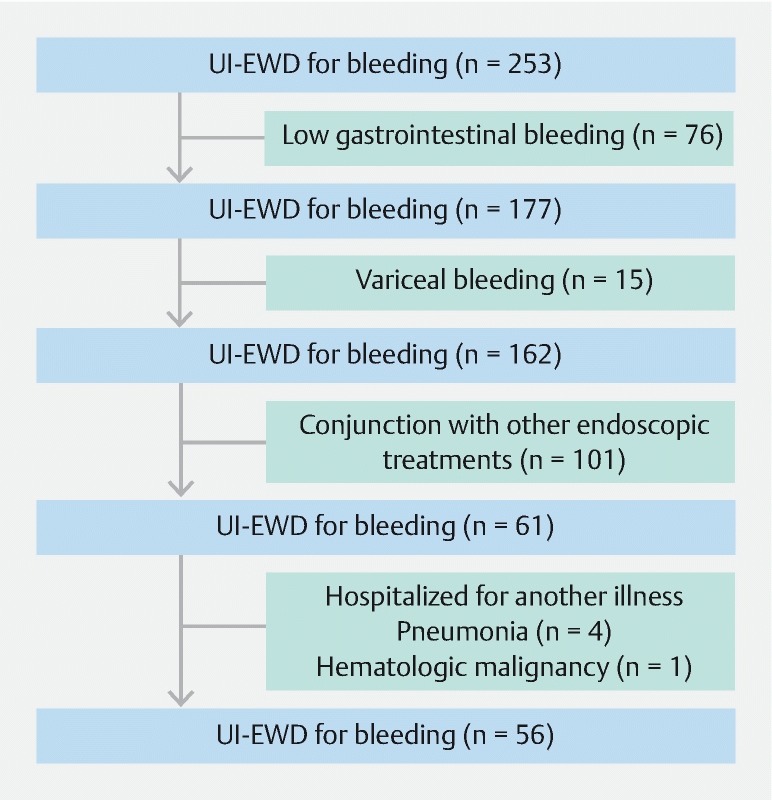

Patients were retrospectively selected from established prospective registries using the following inclusion criteria: (1) age > 18 years; (2) signs of acute bleeding (e. g., coffee-ground or fresh blood vomiting and/or melena); (3) acute NVUGIB of Forrest class Ib, IIa, or IIb caused by peptic ulcer, post-endoscopic therapy, tumor, or others; and (4) receipt of endoscopic hemostasis using UI-EWD monotherapy. Exclusion criteria applied were as follows: (1) low gastrointestinal tract bleeding; (2) variceal bleeding at time of endoscopy; (3) hospitalization for another illness; and (4) receipt of treatment by other endoscopic or surgical means within 30 days prior to UI-EWD application. Fifty-six consecutive NVUGIB patients that met study inclusion criteria underwent UI-EWD monotherapy from January 2017 to December 2018. Patient medical records were analyzed and information on clinical characteristics, bleeding, clinical outcomes (including immediate hemostasis success and rebleeding rates), and UI-EWD-related complications were collected. The study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board (INHAUH 2019-04-014).

Endoscopic procedures

All bleeding was controlled by one of six experienced endoscopists using UI-EWD; each endoscopist had performed more than 1000 endoscopic procedures per annum and had extensive experience (6 – 25 years) with therapeutic endoscopy for UGIB. UI-EWD was applied using a conventional endoscope (GIF-H290 Evis Lucera Elite; GIF-H260 Evis Lucera; GIF-2TQ 260 M Evis Lucera; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to completely cover bleeding lesions of Forrest class Ib, IIa, or IIb using an 8 Fr catheter and a novel spraying device under direct endoscopic vision. After positioning the catheter for powder delivery, the working endoscopic channel was flushed with air (delivered using a 60-mL syringe) to ensure that the catheter tip was dry. Initially, 3 g of UI-EWD was administered in onto bleeding lesions, which were then directly observed for 5 minutes using the endoscope. If bleeding was not controlled, UI-EWD application was repeated up to a maximum powder delivery of 6 g ( Fig. 2 ). In cases of failure, a conventional endoscopic hemostatic modality was used based on discretion of the endoscopist, and the case was defined as an immediate hemostasis failure. Standard scheduled second-look endoscopy was not conducted.

Fig. 2.

Representative endoscopic images of UI-EWD application for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. a Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer was conducted from the stomach body. b A Forrest-IB bleeding from dissection was noted 1 day after ESD. c Application of UI-EWD at the bleeding site; the bleeding lesion completely covered. d Second-look endoscopy 72 hours after UI-EWD application, showing ulcer and no bleeding.

Outcome measurements

Rates of technical success, immediate hemostasis, and rebleeding were evaluated. In addition, all medical records were checked to evaluate adverse events associated with UI-EWD, such as newly developed symptoms, vital signs, and blood tests (i. e., hemoglobin, platelet count, and chemistry). Successful immediate hemostasis was defined when powder application led to hemostasis within 10 minutes by visual inspection. Rebleeding was defined as clinical evidence of bleeding, such as melena or hematemesis, with an associated hemoglobin reduction ≥ 2 g/dL within 30 days of the endoscopic procedure. This definition was applied to all bleeding cases to suspect rebleeding. When rebleeding was suspected, second-look endoscopy was performed to confirm its presence.

Results

Patient demographics

Fifty-six patients (43 men, 13 women) of mean age 64.6 ± 11.2 years were treated with UI-EWD monotherapy for UGIB by six endoscopists at two centers ( Fig. 3 ). Baseline patient characteristics and indication for UI-EWD are summarized in Table 1 . Post-interventional bleeding was the most common cause of bleeding and the most common location was the stomach body. Bleeding was classified as Forrest Ib (n = 36), IIa (n = 12), or IIb (n = 8).

Fig. 3.

Flow diagram of the study design, showing the number of patients at each exclusion step.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients and bleeding.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Patients, n | 56 |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 64.6 (11.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

|

43 (76.8) |

|

13 (23.2) |

| Bleeding etiology, n (%) | |

|

46 (82.1) |

|

8 (14.3) |

|

1 (1.8 %) |

|

1 (1.8 %) |

| Bleeding location, n (%) | |

| Stomach | |

|

3 (5.3) |

|

24 (42.9) |

|

15 (26.8) |

|

13 (23.2) |

|

1 (1.8) |

| Forrest classification, n (%) | |

|

36 (64.3) |

|

12 (21.4) |

|

8 (14.3) |

Clinical outcomes

Immediate hemostasis

UI-EWD was used as the initial bleeding control modality for NVUGIB and was successful in all patients, and in all cases, the amount of UI-EWD used was ≤ 6 g (3 g, 52 patients; 6 g, 4 patients). Primary hemostasis rates achieved by UI-EWD monotherapy are shown in Table 2 . Immediate hemostasis was achieved in 54 of 56 patients (96.4 %). Of the remaining two patients, one with post-interventional bleeding was successfully treated with thermal therapy and in the other, who underwent jejunal anastomosis, bleeding was controlled using thermal therapy with endoclips. At second-look endoscopy 24 hours after procedures, UI-EWD hydrogel remained attached at bleeding sites in 33 of 47 patients (70.2 %) and at 3 days after procedures remained attached in 15 of 38 patients (39.4 %).

Table 2. Clinical outcomes of UI-EWD for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Total patients, n | 56 |

| Overall success of immediate hemostasis, n (%) | 54 (96.4) |

| Overall rebleeding in day 7, n (%) | 2 (3.7) |

| Success rate of hemostasis according to etiology, n (%) | |

|

45 (97.8) |

|

8 (100) |

|

0 (0) |

|

1 (100) |

| Success rate of hemostasis according to Forrest classification, n (%) | |

|

35 (97.2) |

|

11 (91.6) |

|

8 (100) |

Rebleeding

Rebleeding within 7 days occurred in two patients (3.7 %), all of which was ascribed to post-interventional bleeding, and occurred within 24 hours of procedures. All rebleeding was successfully treated with a conventional modality, and neither surgery nor interventional radiology was required to achieve hemostasis.

Spraying catheter clogging and adverse events

Clogging of spraying catheters during UI-EWD spraying occurred in two of 56 patients (3.6 %), and when it occurred the powder was sprayed using another catheter. No procedure-related AEs related to UI-EWD application such as intestinal obstruction or perforation occurred.

Discussion

Results of this study suggest that UI-EWD constitutes a reasonable primary treatment strategy for NVUGIB. The powder was easily applied at all bleeding sites, the catheter clogging rate was low at 3.6 %, and the immediate hemostatic rate was excellent (96.4 %). In addition, the rebleeding rate within 7 days of endoscopic procedures was only 3.7 %.

Recently, several hemostatic powders like TC-325 (Hemospray, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States), Endoclot (AMP; EndoClot Plus Inc, Santa Clara, California, United States), and Ankaferd Blood Stopper (AnkaferdHealth Products Ltd, Istanbul, Turkey) were introduced for the endoscopic control of UGIB. These powders have the advantage of being easy to apply in difficult situations to control bleeding from multiple sites or large areas and have been demonstrated to allow immediate hemostasis to be achieved satisfactorily (73.4 – 100 %) 5 10 11 , but they have also been associated with high rebleeding risk. Sung et al. were the first to describe use of TC-325 in human subjects. They evaluated the hemostatic effect of TC-32520 patients with NVUGIB (mostly Forrest Ib) from gastroduodenal ulcers with high-risk stigmata in a manner similar to that used in the current study 12 . The immediate hemostasis rate was found to be excellent at 95 % for TC-325 monotherapy, but the 7-day rebleeding rate was high (10.5 %). Furthermore, second-look endoscopy at 72 hours, which was performed in all subjects, showed ulcer healing but no remaining hemostatic powder 12 . A later series by Smith et al. returned a much more modest rate of immediate hemostasis (76 %) and a relatively high 7-day rebleeding rate (15.8 %) for TC-325 monotherapy 13 . Subsequently, some experts recommended hemostatic powders not be used to treat conditions such as ulcers with high-risk stigmata because hydrogel residence times are probably less than 24 hours 14 .

In the current study, UI-EWD was also found to have an excellent immediate hemostatic effect (96.4 %), but the rebleeding rate was only 3.7 % (2/54). We attribute this low rate to use of a Schiff base reaction between the hydrogel and tissue 9 . In previous reports, hydrogels produced using other commercially available hemostatic powders were not observed by second-look endoscopy 3 days after endoscopic treatments 13 15 , whereas we found UI-EWD hydrogel was still present at 70.2 % ( 33 of 47 patients) of bleeding sites by second-look endoscopy at 24 hours and at 39.4 % (15 of 38 patients) of bleeding sites at 3 days after procedures. We believe this extended residence of UI-EWD provides more effective tissue sealing and mechanical tamponade and increases effectiveness of hemostasis. However, the hemostatic effect of UI-EWD on spurting arterial bleeding was not investigated because no case of Forrest type Ia bleeding was included. In a previous study, UI-EWD was found not to satisfactorily arrest spurting arterial bleeding (50 %), and it was suggested a method other than UI-EWD be used to address this type of bleeding 9 . We suggest a further well-designed prospective study be undertaken to determine the efficacy UI-EWD in cases of spurting arterial bleeding.

Ideally, endoscopic hemostasis should immediately stop active bleeding, prevent recurrent bleeding, and be easily applied to lesions in any location in the gastrointestinal tract. Although the delivery systems used for currently available hemostatic powders have been improved, they are probably not optimal. Endoscopists must be careful when delivering the agent and should avoid contacting tissue with the delivery catheter tip because of risk of clogging. In addition, if application is conducted too close to the lesion, powder-in-air suspensions may impair adequate visualization 16 . To address this limitation, we used a fluidized bed granulator to modify the water absorption capacity of UI-EWD powder and applied it as a liquid coating, which allowed us to deliver the agent to bleeding areas without catheter clogging or powder scattering 9 . Actually, the catheter clogging rate was only 3.6 % (2/56) in the current study, and adequate visualization was achieved during UI-EWD application in almost all cases.

Some limitations of the current study warrant consideration. First, it is inherently limited by its retrospective design. Second, the majority of bleeding cases were caused by post-interventional bleeding and the bleeding lesions in the stomach body or antrum, which is a convenient position in which for the clinician to spray UI-EWD. In particular, spurting arterial bleeding was excluded, which suggests the possibility that our results do not well reflect the performance UI-EWD for classic ulcer bleeding. Third, because the current study was conducted in tertiary care settings, patients may have exhibited bias toward ost-interventional bleeding (82.1 %). In our clinical experience, post-interventional bleeding is easier to control than classic peptic ulcer bleeding because the focus of bleeding can be identified more easily and UI-EWD is able to splay more effectively against the bleeding focus. This tendency may have affected immediate hemostasis rate of UI-EWD as well as rebleeding rate. In other words, there would be a risk that the effect of UI-EWD has been overestimated. Therefore, we suggest that prospective, multicenter studies be conducted to confirm the efficacy of UI-EWD in daily endoscopic practice.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of UI-EWD monotherapy for treatment of NVUGIB. Based on our results, we suggest it is worth considering UI-EWD as the initial hemostatic method in emergency NVUGIB cases not suitable for traditional hemostatic endoscopic treatments, such as clipping or thermal therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by INHA UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Research Grant.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Lee developed UI-EWD and founded Nextbiomedical Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Hearnshaw S A, Logan R F, Lowe D et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327–1335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkun A N, Bardou M, Kuipers E J et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yau A HL, Ou G, Galorport C et al. Safety and efficacy of Hemospray ® in upper gastrointestinal bleeding . Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:72–76. doi: 10.1155/2014/759436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith L A, Stanley A J, Bergman J J et al. Hemospray application in nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of the Survey to Evaluate the Application of Hemospray in the Luminal Tract. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:e89–e92. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Barkun A, Nolan S. Hemostatic powder TC-325 in the management of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a two-year experience at a single institution. Endoscopy. 2015;47:167–171. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulz M C, Frei R, Meyenberger C et al. Routine use of Hemospray for gastrointestinal bleeding: prospective two-center experience in Switzerland. Endoscopy. 2014;46:619–624. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahyadi O, Bauder M, Meier B et al. Effectiveness of TC-325 (Hemospray) for treatment of diffuse or refractory upper gastrointestinal bleeding – a single center experience. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E1159. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddara S, Jacques J, Lecleire S et al. A novel hemostatic powder for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study (the “GRAPHE” registry) Endoscopy. 2016;48:1084–1095. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-116148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park J, Bang B W, Hong S J et al. Efficacy of a novel hemostatic adhesive powder in patients with refractory upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2019;5:458–462. doi: 10.1055/a-0809-5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang R, Pan Y, Hui N et al. Polysaccharide hemostatic system for hemostasis management in colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:63–68. doi: 10.1111/den.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurt M, Akdogan M, Onal I K et al. Endoscopic topical application of Ankaferd Blood Stopper for neoplastic gastrointestinal bleeding: A retrospective analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung J, Luo D, Wu J et al. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:291–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith L A, Stanley A J, Bergman J J et al. Hemospray application in nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of the Survey to Evaluate the Application of Hemospray in the Luminal Tract. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:e89–e92. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aslanian H R, Laine L. Hemostatic powder spray for GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:508–510. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung J, Luo D, Wu J et al. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:291–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barkun A. New topical hemostatic powders in endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2013;9:744–746. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]