Abstract

Policy Points.

We offer the first systematic conceptual framework for analyzing the operation of mandatory vaccination policies.

Our multicomponent framework facilitates synthesis judgments on single issues of pressing concern to policymakers, in particular, how mandatory vaccination policies motivate people to vaccinate.

We consider the impact of each component of our framework on persons who remain unvaccinated for different reasons, including complacency, social disadvantage, and more or less committed forms of refusal.

Context

In response to outbreaks of vaccine‐preventable disease and increasing rates of vaccine refusal, some political communities have recently implemented coercive childhood immunization programs, or they have made existing childhood immunization programs more coercive. Many other political communities possess coercive vaccination policies, and others are considering developing them. Scholars and policymakers generally refer to coercive immunization policies as “vaccine mandates.” However, mandatory vaccination is not a unitary concept. Rather, coercive childhood immunization policies are complex, context‐specific instruments. Their legally and morally significant features often differ, and they are imposed by political communities in varying circumstances and upon diverse populations.

Methods

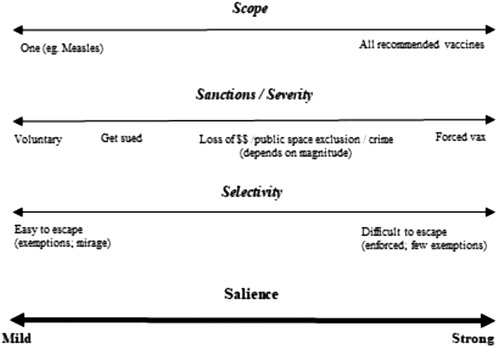

In this paper, we introduce a taxonomy for classifying real‐world and theoretical mandatory childhood vaccination policies, according to their scope (which vaccines to require), sanctions and severity (which kind of penalty to impose on vaccine refusers, and how much of that penalty to impose), and selectivity (how to enforce or exempt people from vaccine mandates).

Findings

A full understanding of the operation of a vaccine mandate policy (real or potential) requires attention to the separate components of that policy. However, we can synthesize information about a policy's scope, sanctions, severity, and selectivity to identify a further attribute—salience—which identifies the magnitude of the burdens the state imposes on those who are not vaccinated.

Conclusion

Our taxonomy provides a framework for forensic examination of current and potential mandatory vaccination policies, by focusing attention on those features of vaccine mandates that are most relevant for comparative judgments.

Political communities across the world are responding to parental refusal of routine childhood vaccines. This is a centrally important issue, since outbreaks of previously eliminated diseases recur where high vaccine coverage rates are not maintained. Societies need uniform high coverage rates of up to 95% to prevent outbreaks, and this uniformity is particularly difficult to maintain when vaccine refusers tend to cluster geographically.1 Moreover, because some people cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons—and a separate cohort of (disadvantaged) children remain unvaccinated due to poor system reach2—governments can accept only very low levels of vaccine refusal if they are to maintain community protection. Recent outbreaks of measles in North America and Europe have made it more urgent for governments to reconsider how they engage with parental decision making about vaccination.3

Abundant scholarship has focused on vaccine hesitancy and refusal in high‐income countries, and we have ample evidence about the beliefs and attitudes of parents who hesitate or refuse to vaccinate. The research literature illuminates the processes of individual and communal reasoning that contribute to vaccine rejection and the societal forces that empower parents to dismiss expert advice.4, 5, 6, 7 Governments would do well to draw on this research in their efforts to persuade parents to vaccinate their children. However, when attempts to reason with parents are ineffective—or when such attempts are too costly or too risky—governments may have good reasons to embrace more forceful measures to promote vaccination, as many societies have already done. These are “vaccine mandates” or “mandatory vaccination.”

“Mandatory vaccination” is commonly invoked but poorly defined. Recent scholarship illuminates the diverse policies to which this term is applied,3 and some scholars have used this term in ways that fail to distinguish significant differences between those diverse policies.8, 9 We can clarify our thinking about vaccine mandates by imposing a taxonomy on both real‐world and possible vaccine mandate policies and asking how, and upon whom, they operate. Recent research by us and others has engaged primarily in the identification and classification of existing vaccine mandate policies, which admit of significant diversity.3, 10 Accordingly, there is already sufficient evidence to conclude that judgments about vaccine mandates—whether they will be effective, ethical, trust‐eroding, and so forth11—cannot be well informed (or, therefore, well justified) if they do not respond to particular components of vaccine mandate policies. The current literature often glosses over these differences. It fails to adequately attend to diverse ways in which mandates can be mandatory, the different (magnitude of) negative consequences for noncompliance, and the scope of the targeted population. More systematic and methodologically rigorous approaches are needed for informed thinking about vaccination governance in light of both current policy diversity and the expanse of possible policies. In this article, we build on previous empirical work to more broadly and systematically conceptualize mandatory childhood vaccination policies.

In what follows, we introduce three primary axes along which to conceive of differences among mandatory childhood vaccination policies. These are scope (which vaccines are mandated), sanctions and their severity (what happens when you don't vaccinate), and selectivity (the management of enforcement and exemptions). As we explore each of these policy components, we engage with the important question of whether and how so‐called mandatory vaccination systems target the vaccination status of the cohorts that can be undervaccinated in a population: those who are undervaccinated due to access reasons (poor system reach) and those who have ready access to vaccines but may choose not to vaccinate based on the belief that not receiving the vaccine is a better option.2 We can further split this latter group into two subgroups—those who are considering refusing vaccines but might be swayed by mandatory policies, and committed refusers—and we consider the capacity of the policy components to work on these subgroups too.

Throughout our analysis, we also consider how specific policy components impact the timeliness of vaccination. In our penultimate section, we narrow our focus to consider how scope, sanctions and their severity, and selectivity interact at the level of individual action, which is the specific problem for which policymakers are invoking and reorganizing contemporary mandatory regimes. From this perspective, the centrally important question is whether and to what degree a vaccine mandate motivates someone to vaccinate, if they were otherwise disposed not to have done so. We call this the salience of a vaccine mandate. Whether a particular vaccine mandate leads someone to vaccinate is only one of the questions of relevance to policymakers. Accordingly, we also briefly discuss other considerations relevant to the success of a vaccine mandate. These include financial and political expediency constraints as well as larger policy goals. In our final section, we employ three case studies to demonstrate how our taxonomy provides a framework for conducting empirical work that classifies and compares different vaccine mandate regimes (between societies and over time), considering their salience for the vaccine hesitant, vaccine refusers, and the general population.

It may be helpful to note some limitations of this article. We do not focus on distinctions between the levels of state or substate government at which power can be exerted to incline people to vaccinate, nor do we address the different tools available to different levels of government. Also, we do not attend to the differences among the various means by which government may generate vaccine mandates, such as legislation, regulation, decrees, policies, and practices.3 Furthermore, we focus on how mandates operate, rather than on their origins and bureaucratic formats. Additionally, this article is not for or against vaccine mandates, both because the fundamental thesis of this article is that vaccine mandates are not homogeneous and because assessments of particular vaccine mandate policies would require empirical information that is often not available. Accordingly, we suggest that this paper's framework can be employed to design policy research into the operation of mandatory vaccination policies, to include detailed document analysis and qualitative interviews with key informants who can answer detailed and specific questions about policies’ operation and likely outcomes.

Scope: Which Vaccines?

Debates about mandatory childhood vaccination policies often seem to presume that governments either mandate or take a neutral stance toward all vaccines. In practice, though, governments make distinct and fine‐grained decisions about whether or how to promote individual vaccines. First, a government must determine whether to license a particular vaccine, to allow it to be sold and administered within its jurisdiction.12 Second, a government must decide which of the licensed vaccines it will recommend, which may include adding them to a technical schedule that identifies which vaccines should be administered at which ages. Third, a government must determine how and whether to fund (or facilitate the funding of) individual vaccines, to make them easy to access; this process usually follows elaborate vaccine‐specific cost‐benefit analyses.13 Finally, governments must decide whether to mandate individual vaccines, through one or more of the means we explore in the next section. Importantly, states do not recommend that everyone receive all the vaccines that they license, they do not provide equal funding for all of the vaccines they license or recommend, and they do not mandate all of the vaccines that they license, fund, or recommend.

Let us consider the distinction between recommending and mandating vaccines. Italy's recent reforms (which we examine in more detail in a case study later in the article) made mandatory a set of vaccines against the following long list of diseases: polio, pertussis, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B, Hib, meningococcal B, meningococcal C, measles, rubella, mumps, and varicella.14 In contrast, other countries mandate fewer vaccines, such as Belgium, which requires only polio.8 Indeed, most states recommend far more vaccines than they require. For example, the United States’ Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends children receive, in addition to seasonal influenza vaccine, at least 32 doses of 12 vaccines that protect against 15 diseases,15 but no US state mandates all of these vaccines and doses.16 Australia mandates almost all its recommended vaccines but not meningococcal B, which it does not even fund.17 France is an outlier; it has recently decided to mandate all of its recommended vaccines.18

Diverse considerations could inform a state's decision to mandate some, all, or no vaccines. The health of the vaccinated child is one consideration, the prevention of unvaccinated children from infecting others is another, and the related maintenance of community protection is a third. High immunization rates also promote a set of social and political values including fairness, education, public trust, and fiscal prudence (since vaccines prevent illnesses and outbreaks are costly for individuals and governments). On this basis, societal benefits for wide‐scope mandatory vaccination could be even more broadly construed. However, mandates negatively impact parental liberty and can contribute to political polarization and the erosion of political legitimacy. These features thus provide caution against mandates. Elsewhere, we lay out the various ethical considerations for policymakers when deciding to make one, some, or all vaccines mandatory, and our arguments draw on relevant facts about individual diseases (eg, threat, contagion) and the corresponding vaccines (whom it benefits and how).19

The relevant point for this current paper is that ethical considerations often do not appear to drive a country's decisions about which vaccines to make mandatory. Instead, historical legacies and pragmatic considerations seem to exert a dominant influence.10 With regard to historical legacies, it is common for vaccines that are made mandatory to remain mandatory, even if the society tends to only recommend additional vaccines in future years. For example, this trend toward inertial or legacy mandates seems prevalent in the histories of immunization policy in Italy and France.10 Pragmatic considerations seem even more consequential for immunization policy. For example, when France recently mandated all recommended vaccines, the decision was driven by questions about what to do when a required vaccine was available only in combination with a merely recommended vaccine.18 The divide between required and merely recommended vaccines created practical problems (as in the case of combination vaccines), but it also generated a troubling rhetorical implication: that “merely recommended” vaccines were not important. However, if societies respond to this problem by mandating all recommended vaccines, such a policy may have the opposite of its intended effect: people may come to believe that all vaccines are only as valuable as the least valuable vaccine. Nevertheless, France chose this policy option after the government investigated what would happen if they made all vaccines recommended (optional); studies showed coverage rates would drop among the most vulnerable.10 In this way, a value like health outcomes equity can play a significant role in determining which vaccines states mandate.

Sanctions and Their Severity

In the preceding section, we explored how governments either construct or inherit frameworks that determine which vaccines are mandatory. A further consideration is how political communities will make vaccines mandatory. Although some discussions of mandatory vaccination seem to take for granted that there is one means by which to “make people get vaccinated,” a critical review of the possible sanctions that could govern vaccine acceptance reveals a diversity of possible interventions. Not all of these are currently operative in political communities, but all have historical precedents or contemporary advocates. In previous research, we developed a framework for analyzing vaccine mandates along a liberty‐oriented spectrum, with complete voluntarism on one side and criminalization on the other.10 In this paper, we further complicate that framework, both by adding additional types of sanctions to the spectrum and by considering the role of the magnitude of each type of sanction. As we will demonstrate, the most severe types of sanctions (eg, criminalization) may not be so severe in application, if the magnitude of the consequence is low (eg, a trivial fine). Accordingly, accurate assessments of the relative severity of different possible vaccine mandates will require attention to the interplay between particular types and magnitudes of possible sanctions.

Forcible Vaccination

States have the capacity to compulsorily vaccinate children against their parents’ wishes and without their consent. This is the most extreme type of sanction because it forcibly brings about the desired result—the vaccination of the child—through a direct assault on the bodily integrity of the child and through an explicit violation of parental liberty. Forcible vaccination narrowly targets (potential) vaccine refusers, since parents willing to vaccinate their children will not have to be forced to do so. Whether a society will tolerate this kind of state intervention in family life will depend on its conception of the rights of parents, the rights or interests of children, and the relationship between the two. For example, the United States protects an especially wide sphere for parental sovereignty; it is the only country not to ratify the UN's Convention on the Rights of the Child.20 Other countries often recognize that the state should play a bigger role in protecting children's rights and interests, but overriding parental authority rarely extends beyond cases in which children are at significant risk of serious harms, or one‐off interventions regarding life‐saving medical treatment.21 However, forcible vaccination remains a live option for the state. We do not know conclusively of any cases where it is currently employed, but Mongolian law states that compulsory catch‐up regimes can be imposed by relevant authorities.22 What compulsory means in this circumstance is unclear, which is further evidence that forensic policy analysis is required to understand the operation of any given jurisdiction's mandatory policy. However, some states and substate units have previously employed forcible vaccination during outbreaks, though in some cases this seems not to have been sanctioned by the relevant statutes. For example, public health officials in 1890s Brooklyn, New York, and 1900s Boston, Massachusetts, sent teams of physicians and police officers on “vaccination raids” of immigrant neighborhoods. Residents often attempted to flee or fight to protect themselves or their children from being vaccinated.23, 24 Furthermore, the governments of many societies will order the vaccination of children in their custody or supervision (eg, orphans or children in foster care), or of children whose parents are legally separated or divorced and who disagree about whether to vaccinate.25, 26 However, in the latter case the vaccination is only “forcible” from the perspective of the parent withholding consent (which is provided by the other parent).

Criminalizing Nonvaccination

The next most severe sanction is for states to make it a crime not to vaccinate one's children. According to this kind of mandatory vaccination policy, those who do not vaccinate are rendered criminals, since they fail to perform an inescapable legal obligation. Criminalization divides the political community: people who vaccinate can be members in good standing, but people who do not vaccinate cannot. Criminalization targets those who are unvaccinated for access or complacency reasons as well as those who refuse vaccines. However, in practice, the threat of a criminal sanction is most likely to motivate those who are unvaccinated because they lack easy access to vaccines, are complacent about vaccination, or are only mildly hesitant. It is likely that this kind of policy will make only committed vaccine refusers into criminals. This type of sanction seems less severe than forcible vaccination, since it does not directly violate the bodily integrity or parental liberty of vaccine refusers; it does not force vaccination. However, criminalization nonetheless has the potential to be an especially severe sanction.

The severity of criminalizing vaccine refusal depends on the magnitude of the criminal sanctions. While a $10 one‐time fine for noncompliance makes vaccine refusal a crime, sanctions of this magnitude likely serve a primarily symbolic function and are likely to influence only people who are mildly hesitant about vaccination or especially reluctant to violate legal rules. In contrast, a $10,000 fine applied annually to all children who are not up to date would make vaccination necessary for all but the most committed (or wealthiest) vaccine refusers. Clearly, if criminal sanctions involved imprisonment, then criminalization would be a severe penalty, and even fines can result in imprisonment if they are not paid. However, if criminal sanctions for noncompliance consist only of minor one‐time financial penalties, then criminalization can be relatively toothless. Such penalties can even transform vaccine refusal into a purchasable commodity: pay the fine and you can be restored to good standing. In this way, criminalization is qualitatively different from forcible vaccination. While the severity of criminalization varies dramatically depending on the magnitude of the criminal sanction, the severity of forcible vaccination does not vary much at all: either the state forcibly vaccinates someone or it does not.

According to a database assembled by the Sabin Vaccine Institute, several countries fine parents who are noncompliant with childhood vaccination requirements.22 These include Belize, Bulgaria, Jamaica, Kosovo, and Mongolia. The fines vary in magnitude and there is no indication whether the fines are repeated if parents continue to fail to comply. Fines are also part of the new Italian vaccine mandate regime,10 but again, forensic policy analysis will be required to determine whether these fines are applied more than once, regarding the same children, if their parents continue to refuse vaccines. Imprisonment for vaccination noncompliance seems uncommon, but the Sabin database states that Ugandan vaccine refusers can be jailed for six months.22

There can be a strong expressive or symbolic connotation to the criminalization of certain behaviors,27, 28 but they can lose their motivational force if the consequences are minor or easily avoidable. Even “minor” criminal sanctions can either reinforce existing social norms or generate new ones over time, and they may therefore be useful policy tools. Furthermore, merely expressive or symbolic criminal sanctions for vaccine refusal can have significant longer‐term social consequences, such as for political polarization on contested policy issues, including immunization policy. For example, in 19th‐century England, refusers who objected to minor fines for noncompliance with vaccine mandates sometimes had their property seized and auctioned. This practice led to mass riots and, eventually, to the development of conscientious objector protections from vaccination laws.29

Denial of Access to Public Spaces

A further sanction that vaccine mandate policies can impose is to exclude the unvaccinated from institutions or spaces to which they would otherwise have access. As well as explicitly protecting the public by keeping the unvaccinated away from those to whom they might transmit disease, this type of exclusion can performatively express an effort to protect public goods and to ensure fair contributions to their upkeep. The concept of a public good refers to a shared resource that all members of a particular community can access without necessarily contributing to its upkeep. Economists and political scientists use this concept to inform our thinking about how to mitigate against cases in which the self‐interested acts of a set of individuals can create an outcome that no one wants. The current state of affairs with regard to global CO2 emissions is a case in point.30 Indeed, the bad consequences of free riding on public goods is a canonical instance of “market failure” for which state intervention can be justified.

Many scholars regard the community protection that results from mass vaccination to be a public good.31, 32 Community protection is a valuable resource available to all who need it, whether they are a newborn baby, a person for whom vaccines are not effective, someone who can't be vaccinated, or someone permanently or temporarily immune‐compromised. [We favor the term community protection 33 over the more familiar but inaccurate herd immunity; high immunization rates allow a community of persons (not a herd of animals) to be protected, but the community does not become immune in any literal sense.] Community protection is also available to those who do not vaccinate but live in places where almost all other people do. Since those in this latter category are free riding on the public good, and actually diminishing it by doing so, they may be committing an offense against solidarity. This is not a criminal offense against state laws, as per the criminal sanction described earlier. Rather, vaccine refusers have objected to full participation in the community's common life. Of course, the state could choose to sanction people who free ride on community protection through fines or imprisonment. But excluding vaccine refusers from spaces in which the community “does things together”—like publicly funded schools or day care—is a way to recognize that vaccine refusers have already placed themselves outside of the community. The most well‐known example of this kind of sanction is school entry requirements present in all US states. Most of them have exemptions, which we deal with in the next section, but the public solidarity logic still underlies this type of sanction. Guyana, Moldova, and Jamaica are among the other countries to also employ this type of “public solidarity” sanction.22

As noted, the forms of exclusion that public solidarity sanctions impose may also be justified by public health considerations specific to the spaces from which they are excluded. For example, the clustering of children at day care and school makes these likely locations for outbreaks, and the operators of these institutions (whether state, not‐for‐profit, or private) have a duty of care to those attending them. Therefore, this kind of sanction may be no more liberty restricting than other neutrally justified restrictions on who may enter various social spaces. For example, children must commonly be toilet‐trained before being admitted to school.

Sanctions that respond to the complementarity among public solidarity, public space, and public protection target those who are unvaccinated due to disadvantage or complacency by motivating them to get their children's vaccines up to date in order to access a public good. This leaves only parents who do not wish to vaccinate on the wrong side of the sanction, and therefore excluded from participation in some aspects of public life.

Financial Levers

Vaccine mandate sanctions can also include financial levers. Of course, fines (discussed earlier) are a financial lever, but they are instances of criminalization. Here, we focus on ways in which the state (or nonstate actors) can withhold payments to the unvaccinated as a means of excluding them from social goods to which they would otherwise be entitled.

One kind of financial lever involves the suspension of incentive payments that are delivered to parents who agree to vaccinate their children. This model was in place in Australia between 1998 and 2012, through a Maternity Immunisation Allowance paid through the federal government's social security system. It was not means‐tested.34 Some developing countries have also employed this approach, awarding incentives at the actual moment of vaccination. For example, people in Nicaragua and India who agreed to be vaccinated have been able to receive small cash payments, but people who refuse vaccines have not received those payments.35, 36 Although one might question whether such policies or approaches should be categorized as sanctions in their governance of vaccination behavior, we classify them as such in this paper, because we wish to be comprehensive about the levers that states can employ, and because denying access to incentives can function as a sanction (ie, a loss, burden, or punishment), especially for people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged.37 Incentive payments function on those undervaccinated for access reasons by prompting them to get vaccinated in order to access an entitlement. Those who do not wish to accept the vaccine potentially fall foul of the sanction.

Governments need not always use specially designed payments as financial levers. Instead, they can incorporate vaccination requirements into the conditional receipt of other financial benefits. Public solidarity reasoning, as outlined earlier, can also support this type of sanction. Public monies constitute a resource to be spent for the benefit of the nation, as determined by the value commitments and pragmatic reasoning of the government. Public funding of community goods is “something we do together.” Governments can attach vaccination requirements to various kinds of financial entitlements, such that the unvaccinated are denied financial support to which they may otherwise be entitled. Some might argue that this is an incentive, rather than a sanction, but we classify it as the latter because this is a case of the state treating the unvaccinated differently—and negatively—thus imposing punitive consequences in the hope of driving uptake. The policy logic is the same as the case of specially designated payments. Those who might otherwise remain unvaccinated due to poor system reach, complacency, or minor hesitancy will vaccinate their children in order to access the entitlement. Only committed refusers will be left on the wrong side of the sanction. The Australian government took this particular approach between 2012 and 2015, abolishing the Maternity Immunisation Allowance and instead linking an annual means‐tested Family Tax Benefit Supplement to the child's vaccination status.38 This payment operates as a form of middle‐class welfare, targeting everyone below a certain income threshold. Following some other significant adjustments to vaccination policy (outlined later in the paper), Australian policy now aligns children's vaccination status to means‐tested entitlements paid fortnightly. The Australian government also makes childcare subsidies conditional upon children being fully vaccinated.39

We will revisit Australia's vaccination policies in the next section when we describe enforcement and exemptions, and again in a case study later in the article. However, for now we note that the bundling of vaccination status and financial entitlement can have different effects on potential vaccine refusers depending on background social practices. The linkage (and potential removal) of an existing entitlement may trigger a loss‐aversion heuristic that would be more powerful than the desire to attain a new, purpose‐built incentive.40, 41 We also note that while “public money reasoning” applies to this kind of sanction, it could also be justified in terms of the financial costs to the state that result from nonvaccination, such as contact tracing and health care treatments in the event of outbreaks of disease.

Legal Responsibility for Harms Caused by Nonvaccination

The final type of sanction conceives of vaccination noncompliance as a possible instance of criminal or tortious negligence.42, 43 In this scenario, vaccination is not itself a legal obligation but is rather a legally recognized duty of care. So, the unvaccinated remain members in good standing of the political community, subject neither to criminal punishment nor to denial of access to public goods. However, if other people are harmed because of a person's failure to fulfill his or her duty to vaccinate, then that person may be subject to criminal or civil liability. Rather than using ex ante compulsion, the threat of criminal or civil liability holds the unvaccinated responsible for the harms they cause. This kind of vaccine mandate is prima facie less restrictive of liberty than are vaccine mandates that criminalize vaccine refusal, notwithstanding the scale of criminal sanctions . It also has different expressive/symbolic content, since it places vaccine refusal alongside other everyday activities—driving a car, operating a business—that are permitted by society, but for whose negative consequences one can be held responsible.

Although legal scholars have debated the viability of this model,42, 43 we do not know of any countries that have sought to impose it. It is possible that one day individuals will be able to trace the source of their or their child's infection to an unvaccinated person. They may then seek to recover their damages through a lawsuit, or the state may decide to pursue a parallel criminal investigation and indictment. In some political communities these kinds of lawsuits and prosecutions may be able to succeed even in the absence of new legislation—since common law may already provide sufficient precedents—but the state can also take various measures to facilitate these kinds of liability ascriptions. These include creating laws that alter the existing burden of proof or delineating appropriate amounts for compensation. The state and/or courts may also need to clarify the scope of a duty to care in the context of vaccination decisions. For example, persons who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons cannot have a duty to vaccinate, so they should not be subject to criminal or civil liability for infecting others, if they otherwise took reasonable means to protect themselves from becoming vectors of disease. States would also have to determine whether and how increased criminal or civil liability for infecting others should differ between persons who are unvaccinated for various reasons, eg, limited access, complacency, or vaccine refusal.

Further Considerations for All Sanction Instruments

In Table 1, we summarize and elaborate on the many kinds of sanctions policymakers may impose on parents who do not vaccinate. There are two additional key considerations that apply to all the sanction instruments we explore, which allow us to further differentiate between them. The first consideration relates to the timeliness of the sanction and its relationship to the timeliness of vaccination. The second consideration relates to which categories of person the sanction does—and does not—aim to impact.

Table 1.

Vaccination Sanction Instruments

| Sanction | Elaboration | Gradation | Example | Policy Logic | Timelines | Touchesa | Key Risks | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forcible vaccination | State forcibly vaccinates child | No—binary policy | Unknown | State seizes child responsibility | Can govern | Everybody | Trauma, overreach, public trust | Protects children (only in cases of serious risk) |

| Criminalization | Fines, imprisonment for parents | Variable severity of fines / sentence | France, Kosovo | Vaccination is a legal requirement | Can govern | Everybody | Commodify punishment | Creates social norm |

| Exclusion from public spaces | No access to school, childcare for unvaccinated | Could apply to few or many institutions; be age limited | School entry requirements (eg, California, USA) | Contribute to public solidarity in order to access products of public solidarity | May not govern timeliness in young children | Only those who use these institutions | Disadvantage for children excluded | Upholds reciprocity; limits spread of disease |

| Financial levers (purpose built or conditional) | No vaccination, no financial entitlement | Could apply to large or small amounts of money | Australia pre‐2016 | As above; also extracts potential costs of disease to state | Can govern | Depends on means testing | Disadvantage for children denied | Contributes to public solidarity |

| Legal responsibility for harms | State makes it easier to sue parents whose children spread disease | Yes—variable policy settings | Unknown | You are responsible for harms you cause | May depend on unvaccinated child's perceived ability to infect others | Everybody; greater burden on poor | Currently no causality provable | Creates social norm; reduces state's fiscal responsibility for care of victims |

Subject to exemption categories and burdensomeness.

Governments have an interest not just in children being vaccinated, but in them being vaccinated on time, according to the age milestones recommended by technical committees. Particular sanction instruments may be more or less effective in achieving timeliness. Forcible vaccination, criminalization, and financial incentives can apply to the parents of even very young children, whereas exclusions from institutions of public solidarity (day care or school) will apply at later ages and will therefore be less timely for young children.9 Legal obligations to avoid infecting others can operate as a threat at any age, but parents may also be less worried about infants spreading disease than toddlers or schoolchildren. For all of these reasons, the choice of sanction instrument may affect the timeliness of vaccination.

The categories of person touched by a sanction is potentially an even more important consideration. Forcible vaccination, criminalization, and legal obligations to avoid infecting others could theoretically apply to all parents, but the latter two sanctions would have a differential impact for families with different amounts of financial assets. Exclusions from institutions of public solidarity will only affect those who would intend to use them; on this basis there is a distinction between schools, which are generally compulsory, apart from home schooling, and day care, which is only used by some families. Moreover, families that do not use day care may do so for a variety of reasons, including financial resources (able to live on a single income or hire a nanny), social capital (family members or friends providing care), and lifestyle commitments (the choice to have a stay‐at‐home parent).44, 45 Parents’ economic class and social group identities will therefore have significant impact on whether particular kinds of sanctions will impact their immunization behaviors.

The differential operation of these kinds of exclusion can also play out with financial levers, depending on how they are designed. Non‐means‐tested special incentive payments theoretically treat everybody equally; in practice they have differential impact depending on the household's relative wealth and the difference the incentive would make to the family's financial well‐being. Meanwhile, conditional entitlement to other forms of means‐tested welfare based on vaccination status involves governments making an explicit decision: they are not going to concern themselves with the vaccination status of children whose parents earn too much money to be eligible for, or reliant upon, state payments. In this way, an entire social class goes “ungoverned” because of the choice of sanction. It seems clear that any sanction that involves money—coming in or going out—will have less impact on the wealthy. For this reason, we have heard suggestions that Australia, where cash‐ and entitlement‐based mandates have a disproportionate impact on those in lower income brackets, should impose a taxation surcharge on high‐income earners whose children are not vaccinated. Such a system, currently in operation for high‐income earners who do not take out private health insurance, would put a lever in place to govern the vaccination behavior of this economically privileged cohort.

Selectivity: Enforcement and Exemption

The previous section explored the design of mandatory vaccination policies regarding the choice of sanction. Another important component of mandatory vaccination policies is their method of enforcement and exemption.

One option is for policymakers to adopt a rule‐based form of selective enforcement that identifies general and objective conditions for excusing people from the sanctions otherwise associated with vaccine refusal. Another option is to grant officials tasked with enforcing vaccine mandates the discretion to determine whether some noncompliant persons should be exempt from sanctions. In this second kind of selective enforcement, agents of the state are empowered to weigh the benefits and costs of sanctions in individual cases. A third category of selective enforcement includes mandatory policies that appear to have been designed to make it easy for parents to avoid the consequences of mandates or that outsource enforcement decisions to third parties who are neither motivated nor required to enact them. Mandates in this third category—which we call mirage mandates—appear to have been designed not to be mandates at all, but this is usually not made explicit. Mirage mandates may result from governments’ attempts to appear tough on vaccine refusal while limiting adverse impacts on vaccine‐refusing families.

Exemptions based on legal rules excuse some people who meet particular conditions from vaccine mandate policies’ sanctions. Individuals who live in societies whose vaccine mandate policies include rule‐based exemption procedures can know in advance whether they will qualify for an exemption, since the criteria for receiving an exemption are objective and general, and they are publicly announced. The most common example of this kind of exemption is for people for whom vaccination is medically contraindicated; these are medical exemptions. It is also common to offer exemptions to people who object to vaccination for reasons of religious conviction or personal belief. These are nonmedical exemptions (NMEs).

In theory, determinations about medical and nonmedical exemptions could both be made based on whether people requesting exemptions meet the relevant objective criteria. This is common in the case of medical exemptions, which are often subjected to scrutiny. For example, political communities that allow medical exemptions usually require physicians or other health care professionals to attest that immunization is contraindicated. These communities often police the physicians and other health care professionals who make such attestations, and they sometimes punish fraud or encourage the relevant professional societies to do so.46

In contrast, people who request NMEs are often not directly interrogated about their putative reasons for refusing vaccines. This is for many reasons, including the epistemic difficulties involved in assessing the sincerity of a person's claims, the financial costs involved in conducting such an assessment, and the violations of personal information privacy and religious liberty that such an intervention might entail.47, 48, 49, 50 Therefore, in practice, NME policies usually limit the distribution of exemptions not according to whether people provide the right kinds of reasons, but whether they are willing to withstand the required bureaucratic procedures. For example, parents in Germany who seek NMEs must demonstrate that they have received medical counseling. Australia also employed this exemption model until 2016. The process is similar for parents in some US states, who must complete an education program in order to access exemptions, while parents in other US states need only to submit an official state form on which they attest to their objection.51

Exemption application processes that rely on the burdensomeness of exemption application procedures to limit the number of exemptions do not directly enforce vaccination. Instead, such policies function as nudges, since they alter the choice architecture in ways that parents can avoid with minimal effort.52 This does not mean that the burdensome aspects of an exemption program are valuable only because they deter people from applying for exemption, since education requirements may change some parents’ minds about immunization. Consider that Michigan's NME rate declined by 35% between 2014 and 2015, when new provisions were introduced requiring parental education (see case study later in the paper). Although most of that decline is likely due to fewer people applying for exemptions, some people who applied for NMEs subsequently allowed their children to receive vaccines they refused at the beginning of education sessions. For example, in one of Michigan's largest counties, 16.4% of children whose parents attended an education session received (within 18 months) at least one vaccine that their parents had previously rejected (although many of these parents were following alternative schedules and may have decided to vaccinate even in the absence of education sessions).53 However, even when an education session does not lead to increased immunization compliance, it can contribute to a parent's informed refusal of childhood vaccines, which is an important moral good.11, 54

Vaccine mandates with permissive NME criteria encourage uptake among the complacent or socially disadvantaged. These kinds of mandates are low stakes because the categories of people whom they incline to vaccinate are not firmly committed to refusing vaccines, unlike high‐stakes vaccine mandates, which involve direct conflict with committed vaccine refusers. Thus, while mandatory systems with permissive NME criteria still address the behavior of vaccine refusers, by imposing administrative burdens, they do not sanction the decision to refuse itself. We will consider the implications of this kind of selectivity in the final section.

States can decide not to identify in advance the classes of exempt individuals, as described previously, but can instead construct formal mechanisms by which representatives of the state can decide whether and when to grant exemptions. When Australia abolished financial entitlements to refusers (conscientious objectors), the new law designated that the secretary of the Department of Human Services could determine whether individuals can be regarded as meeting immunization requirements even though they are not vaccinated.38 Limited criteria apply, but the determination is made by an individual from the state.

States can also adopt informal mechanisms that allow state officials to make decisions about whether and when sanctions will apply. This informal selective enforcement operates in cases where state officials are aware that individuals are not complying, or are likely not complying, with requirements, but choose not to investigate or to impose penalties or sanctions. This was the status quo in France and Italy until their recent policy changes.10

Finally, states can construct mandatory policies whose sanctions are effectively nonenforceable. These mirage mandates may appear to include sanctions, but close examination reveals a policy that has been designed so that they barely apply or are easily avoidable. For example, a potential mirage mandate exists in the Australian state of Queensland. Like many Australian states, Queensland has a No Jab, No Play policy, which ostensibly prevents access of the undervaccinated to childcare facilities. (State‐based No Jab, No Play policies complement the federal No Jab, No Pay policy, which withdraws financial entitlements from the undervaccinated.) The Queensland policy seems to require parents to vaccinate their children or have their children excluded from childcare, but the law actually only enables childcare providers to exclude these children. However, childcare providers may have a compelling financial interest not to exclude children from their businesses. Accordingly, Queensland's form of proxy enforcement of its sanctions for vaccination noncompliance likely makes its policy a mirage mandate.

How should we make sense of different enforcement and exemption options and the diverse effects that they can have on the operation of mandatory policies? (See Table 2 for a summary.) Mandates that can be avoided through exemptions, selective enforcement, or indeed, their prior construction as mirage mandates could be defended on the grounds that they protect conscience and that they provide a relief valve for citizens who would otherwise “make trouble” for the government, particularly in ways that could put broader vaccination coverage at risk. When the state excuses from legal obligations a small group of people who would otherwise passionately resist, this can make legal obligations more stable and popular, or at least less likely to be the target of mobilized political movements. Whether such exemptions or selective enforcement is ultimately justified depends on background political and epidemiological conditions.

Table 2.

Vaccination Selectivity (Enforcement and Exemption)

| Mode | Elaboration | Example | Policy Logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad and clear exemption regimes | You can get out of vaccinating if you follow set procedures | Michigan (US): Exemption after attending education session | Govern the complacent, don't squeeze refusers |

| Engineered selectivity (individuals approve cases) | Limited decisions to allow exemptions are enacted by senior functionaries | Australia: Federal Departmental secretary grants limited exemptions | Some (minimal) flexibility to be responsive case by case |

| Informal nonenforcement | Noncompliance with stated laws or policies not investigated or punished | Italian children not excluded from school, 1999–2017 | Avoid publicity of removing mandate (may damage uptake) |

| Mirage mandates | Policy design facilitates noncompliance | Queensland (Australia): Childcare providers decide whether to exclude unvaccinated children | Appear to be taking tough action while facilitating noncompliance |

A well‐run exemption program may have ancillary benefits beyond the incentive it provides for lukewarm vaccine refusers to become vaccinated, such as mandating the receipt of education about immunization, or protecting the principle of informed consent to vaccination and vaccine refusal.55 For example, when Australia abolished conscientious objections to vaccination, Leask and Danchin noted that the previous requirement that parents sign conscientious objection forms provided a (now lost) opportunity for medical professionals to discuss parents’ vaccination decisions.11 Also, this form had allowed the government to collect data about who was and was not vaccinated, which could help researchers better identify the reasons people refused vaccines. Such data could then help governments address vaccine coverage using alternative, nonmandatory strategies. Mirage mandates cannot deliver these kinds of benefits, since they generally allow refusers to avoid consequences of all kinds, both sanctions and the bureaucratic burdens of exemption application policies.

Selective enforcement, exemptions, and even mirage mandates will be easier to justify when they excuse few enough vaccine refusers from sanctions that vaccination rates remain high. However, if too many people have reasons (or claim to have reasons) to reject vaccines, then exemption systems may inhibit the successful operation of vaccination policies in achieving community protection. Having tight enforcement and limited exemptions will squeeze parents, some of whom will object vociferously and/or find alternative ways to avoid vaccinating their children. For example, recent research describes how Australian medical exemptions doubled following the abolition of conscientious objections, such that the eligibility for them was subsequently tightened.3 A similar result ensued in California after its elimination of NMEs.10

Vaccine mandates are in the news presently because of specific changes to enforcement and exemption rather than because entirely new mandatory policies have been developed. California and Australia removed formal selective enforcement (exemption) processes from the mandatory systems already in place. France and Italy went from lax enforcement to revised regimes of requirements and consequences.10 Selectivity—exemption and enforcement—is a key component of vaccine mandates, because it has such a strong influence on compliance, regardless of the kind of sanction that is chosen. We continue discussion of this theme in the next section.

For now, we conclude this section with an additional consideration that cuts across all types of selectivity: the populations targeted by selective enforcement policies. We identify three normatively and pragmatically distinct categories of persons who could be targeted:

The undervaccinated, due to complacency or poor system reach

Persons predisposed to refuse some or all vaccines who could be convinced to vaccinate by mandates

The committed vaccine refusers, who will not vaccinate even if threatened with significant sanctions

A vaccine mandate policy's form of enforcement selectivity determines, in part, which groups the policy will incline toward vaccinating. For example, mandates with generous exemption regimes (however constructed) will predominantly affect the vaccination behaviors of those in group 1. Mandates with more restrictive exemption regimes may also nudge members of group 2 toward vaccination—by increasing the costs of vaccine refusal—but these regimes will avoid direct political conflict with the members of group 3. Mandates with limited selectivity—whose sanctions are very difficult for vaccine refusers to escape—will have the best potential to govern the vaccination behaviors of all three groups. But, as we note in the next section, the success of a mandate with such limited selectivity will depend, also, on the other components of that policy, including its scope and the type and magnitude of its sanctions.

Salience: Putting Scope, Sanctions, Severity, and Selectivity to Work

Policymakers who are considering implementing or revising vaccine mandates usually do so with the goal of increasing vaccination coverage among those who would otherwise refuse vaccines. (Some jurisdictions have also experimented with permitting greater freedom of choice, even at a cost to vaccination coverage.)56 Therefore, from the point of view of recent and ongoing debates about vaccine mandates, a centrally important question is the degree to which a particular mandatory vaccination policy impacts vaccination coverage compared to other possible policies, whether mandatory or nonmandatory. We want to know whether one policy is more likely than another policy to “make” people get vaccinated. This is a question about what we call the salience of a vaccine mandate.

In the previous three sections, this paper focused on differences in the form and substance of vaccine mandates along three axes: scope, sanctions and severity, and selectivity. This section identifies how viewing these three aspects of vaccine mandates in tandem can help answer questions about whether vaccine mandates accomplish one of their most important goals: getting people to vaccinate. Therefore, salience is not an additional free‐standing axis of analysis, since we learn about a vaccine mandate's salience only by reflecting on other features of a mandate policy. (We have illustrated the scales in Figure 1.) Furthermore, our treatment of salience does not identify a definitive aggregation that collapses all policy features to a single scale. Rather, the purpose of our salience analysis is to inform comparative judgments among past, present, and proposed versions of a single jurisdiction's mandatory vaccination policy (eg, “Australia's recent policy shifts have made its vaccination mandates more salient than they used to be”) or between two jurisdictions (eg, “California's mandates are more salient than Washington's”). To illustrate the application of salience considerations to real‐world examples, we include case studies in this section briefly exploring Australia, Italy, and Michigan; three cases on which we have recently gathered evidence. A more complete assessment of the salience of particular vaccine mandates will require attention to historical, bureaucratic, political, and cultural factors that are beyond the scope of this kind of theoretical article.

Figure 1.

Determining the Salience of Mandatory Vaccination Systems

A mandatory vaccination policy's scope, sanctions, and selectivity will each influence a vaccine mandate's salience to individuals making decisions about vaccinating their children. We must consider these components in tandem and interactively. For example, from the point of view of a mandate policy's scope, a policy that requires only one vaccine may be more likely to generate compliance than a policy that requires eleven vaccines. Also, from the point of view of a policy's sanctions, excluding children from school or day care is more likely to generate compliance than a policy that imposes a trivial one‐time fine. But what about the difference between a policy that requires one vaccine and excludes the noncompliant from school, versus a policy that requires eleven vaccines but imposes only a trivial one‐time fine? Although we suspect that the former policy will generate greater compliance, we need context‐specific information—and better empirical evidence—before confident predictions are possible.

Questions about selectivity are central to determination of salience. In particular, rule‐based NME regimes can often be so permissive as to make irrelevant—from the point of view of salience—policy differences of all other kinds. For example, it almost certainly makes little difference to vaccination behavior whether sanctions include imprisonment, fines, exclusion from public goods, or the withdrawal of benefits if there exists a permissive rule‐based exemption program. In such cases, the sanctions need not apply to anyone at all, and parents can know as much in advance. Those who wish to refuse vaccines will apply for exemptions, while parents who are content to receive vaccines will comply. If such a policy motivates anyone at all, it inclines toward vaccination only those parents whose children may have otherwise remained undervaccinated due to reasons of imperfect access, complacency, or mild hesitancy. In contrast, scope questions will remain relevant even when permissive rule‐based exemption policies exist, since it matters which vaccines a mandate policy inclines mildly hesitant parents to accept.

Case Study: Australia

Background: Since 1998, Australia has used financial incentives under federal legislation to prompt parents to keep their children up to date with vaccinations. These were specific periodic payments until 2012, when receipt of other annual payments to eligible families—as well as childcare subsidies—became conditional upon children being up to date with their vaccinations. Since 2018, vaccination status has further been linked to fortnightly payments and repackaged childcare subsidies, both of which are means tested. Eligible parents can receive federal payments for their children until they turn 20 years of age.

Scope: Australia recommends a number of infant and childhood vaccines, but not all are listed on the National Immunisation Plan. Only those on the plan are included in the mandatory vaccination scheme. The 12 vaccines included are diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, varicella, HIB, meningococcal ACWY, and pneumococcal.

Sanction and severity: Australia uses financial levers. Parents whose children are not vaccinated and who would otherwise be eligible for Family Tax Benefit A (fortnightly payment) and Child Care Subsidy have payments cut, at a possible annual penalty of up to $15,000.

Selectivity: In 2016 the Australian government removed conscientious objection, which had enabled Australian families to opt out of vaccination after lodging a form signed by a medical professional who had counseled them. This way the family could still receive financial assistance. Since 2016, only specified and tightly controlled medical exemptions are available for those seeking to receive vaccination‐linked payments.

Further considerations: Because Family Tax Benefit A applies from birth, eligible families are incentivized to vaccinate on time from the very beginning. While Australia's federal payments function as middle‐class welfare and hence apply to a large proportion of the population, they do not touch high‐income earners. Approximately a third of Australian families with dependent children receive Family Tax Benefit. Childcare Subsidy is available to parents with higher incomes (but still means tested). However, Childcare Subsidy does not prompt parents to vaccinate until their children start attending childcare. Both these mandatory options would appear salient to parents to whom they apply, with considerable financial losses for noncompliance (until the child is an adult) and very limited capacity for exemptions. However, the policy reflects a strategic government decision to leave ungoverned the vaccine behavior of higher‐income earners. This is only partly addressed by a federal government request to the states to introduce policies excluding unvaccinated children from childcare centers, which are their domain. Four states have introduced variants of such a policy.

A related salience question involves balancing the burdensomeness of sanctions with the burdensomeness of being exempted from sanctions. As we just mentioned, sanctions provide little incentive to vaccinate, regardless of their magnitude, when rule‐based exemptions are easy to acquire, or when it is widely known that state administrative or legal officials are permissive in granting exemptions. In contrast, when rule‐based exemptions are very burdensome to access, or when the decisions of state officials are uncertain, then the resulting mandate would be more salient, prompting people to vaccinate rather than routinely request exemptions.47, 57

This section has so far focused on how vaccine mandates can succeed at inclining individuals to vaccinate. But there are two further ways in which attending to the goals of vaccine mandates can inform research and deliberations about vaccine mandates. First, there are other policy levers that can influence people to vaccinate. Inasmuch as salience focuses our attention on the goals of immunization policy, it can direct us to consider alternative or complementary policies that can assist in pursuing those goals, such as implementing finely calibrated communications campaigns and addressing access barriers. Options and choices in these alternative modes of governance—scope, sanctions and their severity, and selectivity—might then inform decisions about the salience of vaccine mandates. For example, if a government employed a communications campaign as a complement to its vaccine mandate, it might be able to scale down the severity of the sanction (and hence the salience) of the mandate, while maintaining high immunization rates, if the communications campaign can increase vaccine uptake.

Case Study: Italy

Background: Some vaccinations in Italy have been classed as mandatory since their introduction last century (diphtheria, polio, tetanus, and hepatitis B), but other vaccines were merely recommended. Italy's historical mandatory system invoked both fines and school exclusion for those who declined the mandatory vaccines, but these were rarely enforced, particularly school exclusion, since 1999. Italy's vaccine policy changed in 2016 with a ministerial decree classifying an additional six vaccines as mandatory and an alteration to sanctions.

Scope: Italy's mandatory vaccines are diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, HIB, hepatitis B, and varicella.

Sanction and severity: Italy's reworked mandatory system employs two different kinds of sanction. It denies access to public spaces by preventing unvaccinated children from enrolling in daycare and preschool. (While Italy's reworked mandatory system uses enrollment in further compulsory schooling to appraise students’ vaccination status, no exclusions apply to those who are not vaccinated.) In addition, regardless of whether children are old enough to be attending compulsory schooling, parents can be fined for not vaccinating their children; fines are set nationally at €100 to €500.

Selectivity: Italy permits medical exemptions to vaccine mandates only in instances in which a child has a recognized contraindication. There are no other types of exemption available.

Further considerations: Our ongoing empirical research investigates the exact implementation of fines for nonvaccination, including how proactively these are applied in early childhood outside of the prompts of school enrollment data collection. This will determine whether the mandates govern timeliness of uptake. Italy's decentralized health system, with different regional data recording practices and no national register, is another complexity.

Second, the central goal of vaccine mandates—influencing individuals to vaccinate—is usually only an intermediate goal, meaning it is a goal that is in service to more important ends. When we focus attention on salience, we invite reflection about the further purposes served by getting more people vaccinated, for example, to minimize loss of life in our community, to globally eradicate a particular disease, to cultivate social norms surrounding immunization, to promote solidarity about public health. And these reflections can inform decisions about how to structure vaccine mandates. For example, if a particular vaccine mandate aims ultimately at saving lives, then that may be a reason to limit its scope toward only those diseases for which there is an epidemiological risk of outbreak. Or, for another example, if policymakers want to focus ultimately on cultivating social norms in support of vaccination, then they might want to prioritize sanctions that have public and performative aspects, such as the “public” nature of exclusion from schools or the use of merely symbolic criminal or civil penalties. Such considerations can and should ultimately inform the salience level of specific vaccine mandate policies.

Regardless of the particular goals governments pursue with vaccine mandates, economic realities may place significant practical or moral restrictions on the salience of such policies. First, governments making decisions about the constituent elements of vaccine mandates need to consider how the burdens of sanctions or exemption processes will be distributed among the population. For example, financial sanctions will be more burdensome for the poor. Exclusion from day care or school exclusion is likely to have a similar class‐based impact, but its differential impact will directly distinguish between parents who can and cannot care for or teach their children at home. Additional equity issues arise when considering the salience of various kinds of selectivity. If accessing an NME requires attending an education session or completing on online module, then people with less free time, or who lack Internet access, will face a disproportionate burden. Again, this is a burden likely to be borne disproportionately by the economically and socially disadvantaged. Thus decisions about the ultimate design of a vaccine mandate should be informed by the question, For whom will this mandate be salient, and who gets to dodge its consequences?

Case Study: Michigan (USA)

Background: Michigan's Public Health Code (Act 368 of 1978) requires children to be vaccinated before enrolling in school or childcare, but it allows for medical and nonmedical exemptions (NMEs). The responsibility for identifying the required vaccines and the method for applying for exemptions are delegated to a committee of the state legislature, the Joint Committee on Administrative Rules (JCAR).

Scope: For enrollment in kindergarten, Michigan requires vaccines against nine diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, and varicella.

Sanction and severity: Michigan uses denial of access to public spaces. Children who have not received the required vaccines will not be admitted to childcare, kindergarten, seventh grade, or upon their transfer into a new school district. If immunization levels in another grade become too low, as determined by the local health department, then the local school board can also require immunization for admission to that grade.

Selectivity: Applications for medical exemptions require a signed statement from a physician (medical doctor or doctor of osteopathic medicine) and may be scrutinized by local health departments. Beginning in 2015 JCAR determined that parents or guardians who wished to apply for NMEs had to (1) complete an official state form attesting to the reasons for their refusal, and (2) attend an immunization education session at a local health department.

Further considerations: Because the sanctions involved apply only at enrollment in childcare or school, they do not target children at very early ages, especially in families that do not make use of childcare. The school entry requirements apply to both public and private schools, but private schools may have a financial incentive to keep as many students enrolled as possible, and they therefore may be more willing to “provisionally” admit students who are neither vaccinated nor in possession of an exemption. Private schools may also be more likely to encourage families to acquire exemptions than to become vaccinated, since they are more directly accountable to the preferences of the families they serve. Public health advocates in the state have expressed their desire to eliminate NMEs entirely, following the lead of California, but this is not currently politically feasible, since the party that controls the state legislature is committed to preserving NMEs.

Funding considerations may also place limits on the constituent features and hence salience of a society's vaccine mandates, since all of the features we have discussed can place financial burdens on the state, from reporting procedures to exemption processes to methods of enforcement. For example, it may be much more expensive for a state to provide mandatory one‐on‐one immunization education as a condition of applying for an NME than it would be not to allow NMEs at all. Conversely, when vaccine mandates exclude more children from publicly funded schools, or when they withhold childcare payments to parents, these policies can save the state substantial sums, at least in the short term.58

Finally, it may be unethical, illegal, or otherwise destructive for societies to implement the most salient kinds of vaccine mandates, even if these are the most efficient means for promoting immunization. In particular, societies should first try to make it easier for people to choose vaccination for themselves, in light of the ethical imperative to treat coercion as a last resort in public health. Unfortunately, some societies have chosen not to prioritize access‐promoting efforts, but have resorted instead to mandates as a “quick fix.”3, 10 We therefore join previous researchers who have argued that vaccine mandates, particularly those that are more salient, are likely to be unjustified in contexts in which vaccines are not available, access to vaccines is not publicly funded or otherwise free, or when vaccines are difficult for populations to access, for example, due to time or travel.3 Moreover, governments with mandatory schemes that do not also have no‐fault compensation schemes for those injured in the course of routine vaccinations are also reneging on their end of the bargain in the “things we do together.”59

Conclusion

Mandatory vaccination is not a unitary concept. Instead, vaccine mandates are distinguished by their use of different sanctions to influence diverse populations. These policies focus on a different number of vaccines and they involve various mechanisms of enforcement and exemption. The conceptual framework we have outlined in this paper can illustrate the wide variety of real‐world and potential vaccine mandates. This framework can also be helpful for a set of additional reasons: First, it helps us to understand the salience of a particular mandatory vaccination policy, since a mandate policy's impact on the target population's vaccination behavior is centrally important in policy debates. Second, it helps us to consider how particular policy levers work and where they fall short. For example, school access mandates reach a broad population but do not directly target on‐time infant and toddler vaccination. Additional childcare access mandates only partly address this because not all families utilize out‐of‐home care. Third, the framework helps us to consider the ways in which diverse mandatory vaccination policies have different impacts on people who are undervaccinated for access reasons versus people who are more or less hesitant about vaccination. Ideally, all of these considerations should inform debates about vaccine mandates. Finally, as we noted in our introduction, it will not be sufficient to draw conclusions about any mandatory policy's operation based merely on an analysis of the text of a statute or policy document. Instead, we need to pursue empirical work and, in particular, qualitative research aimed at context‐specific populations of citizens and policymakers. The framework we introduce in this paper can structure and guide such research.

Funding/Support

Katie Attwell is recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award, funded by the Government of Australia under grant number DE190100158.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Attwell reports nonfinancial support from GSK and personal fees from Merck & Co., outside the submitted work. Dr. Navin has nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Alberto Giubilini, Roland Pierik, and Marcel Verweij for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. They also thank all the scholars who have informed their thinking on vaccine mandates, particularly Mark Largent, Julie Leask, and Saad Omer. The authors are grateful to Shevaun Drislane for her assistance in preparing the manuscript, and to the anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of the article.

References

- 1. Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M. Geographic clusters in underimmunization and vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):280‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bedford H, Attwell K, Danchin M, Marshall H, Corben P, Leask J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: the need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6556‐6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MacDonald NE, Harmon S, Dube E, et al. Mandatory infant & childhood immunization: rationales, issues and knowledge gaps. Vaccine. 2018;36(39):5811‐5818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007‐2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150‐2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763‐1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dube E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti‐vaccine movement: influence, impact, and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(1):99‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ward PR, Attwell K, Meyer SB, Rokkas PR, Leask J. Understanding the perceived logic of care by vaccine‐hesitant and vaccine‐refusing parents: a qualitative study in Australia. PloS One. 2017;12(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haverkate M, D'Ancona F, Giambi C, et al. Mandatory and recommended vaccination in the EU, Iceland and Norway: results of the VENICE 2010 survey on the ways of implementing national vaccination programmes. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(22). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee C, Robinson J. Systematic review of the effect of immunization mandates on uptake of routine childhood immunizations. J Infect. 2016;72(6):659‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Attwell K, Navin M, Lopalco PL, Jestin C, Reiter S, Omer SB. Recent vaccine mandates in the United States, Europe and Australia: a comparative study. Vaccine. 2018;19(36). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leask J, Danchin M. Imposing penalties for vaccine rejection requires strong scrutiny. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(5):439‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baylor NW. Role of the national regulatory authority for vaccines. International Journal of Health Governance. 2017;22(3):128‐137. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nolan TM. The Australian model of immunization advice and vaccine funding. Vaccine. 2010;28(S1):A76‐A83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le novità del decreto legge sui vaccini . Ministero della Salute [Ministry of Health] website. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=2951. Published May 19, 2017. Accessed June 20, 2018.

- 15. Immunization schedules . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html. Updated 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- 16. State mandates on immunization and vaccine‐preventable diseases . Immunization Action Coalition website. http://www.immunize.org/laws/. Published 2016. Accessed June 16, 2018.

- 17. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Meningococcal Vaccines for Australians: Information for Immunisation Providers. Westmead, Australia: National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance; 2019. http://ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2019-04/Meningococcal_FactSheet_April2019_Final.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ward JK, Colgrove J, Verger P. Why France is making eight new vaccines mandatory. Vaccine. 2018;36(14):1801‐1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Navin, M. and Attwell, K. Vaccine mandates, value pluralism, and policy diversity [published online August 6, 2019]. Bioethics. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12645 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) . 1989. https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- 21. Gostin L, Wiley L. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. 3rd ed Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sustainable Immunization Financing (SIF) . Program Legislative Database. Washington, DC: Sabin Vaccine Institute; n.d. https://www.sabin.org/sites/sabin.org/files/immunization_legislation_database.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albert MR, Ostheimer KG, Breman JG. The last smallpox epidemic in Boston and the vaccination controversy, 1901‐1903. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):375‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colgrove J. Between persuasion and compulsion: smallpox control in Brooklyn and New York, 1894‐1902. Bull Hist Med. 2004;78(2):349‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gordan V. Michigan appeals court rules “unfit” parent can't block kids’ vaccination. Michigan Radio. March 24, 2016. https://www.michiganradio.org/post/michigan-appeals-court-rules-unfit-parent-cant-block-kids-vaccination. Accessed March 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberts R. Vegan mother forced by High Court to vaccinate her children. The Independent. April 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]