Abstract

Policy Points.

Widespread diffusion of policy innovation is the exception rather than the rule, depending as it does on the convergence of a variety of intellectual, political, economic, and organizational forces. The history of Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) provides a compelling case study of this process while also showing how conditions may shift over time, altering the scenarios for continued program expansion.

Diffusion of a program like ACT challenges government to play a nuanced role in which public endorsement and resources are used to strengthen a worthwhile service, but without suppressing flexibility and ongoing experimentation as core program values.

Acceptance as a proven form of “evidence‐based practice” is a critical element in the validation of ACT and other community mental health interventions that combine clinical and social features in novel ways. However, the use of conventional evidence‐based research as a singular gold standard of program value narrows the range of stakeholder input, as well as the evaluation methodologies and forms of data deemed worthy of attention.

Context

Originating at the county level in Wisconsin in the early 1970s, Assertive Community Treatment is one of the most influential mental health programs ever developed. The subject of hundreds of research studies and recipient of enthusiastic backing from private advocacy organizations and government agencies, the program has spread widely across the United States and internationally as a package of resources and management techniques for supporting individuals with severe and chronic mental illness in the community. Today, however, ACT is associated with a rising tide of criticism challenging the program's practices and philosophy while alternative service models are advancing.

Methods

To trace the history of the Assertive Community Treatment movement, a diffusion‐of‐innovation framework was applied based on relevant concepts from public policy analysis, organizational behavior, implementation science, and other fields. In‐depth review of the literature on ACT design, management, and performance also provided insight into the program's creation and subsequent evolution across different settings.

Findings

A number of factors have functioned to fuel and to constrain ACT diffusion. The former category includes policy learning through research; the role of policy entrepreneurs; ACT's acceptance as a normative standard; and a thriving international epistemic community. The latter category includes cost concerns, fidelity demands, shifting norms, research contradictions and gaps, and a multifactorial context affecting program adoption. Currently, the program stands at a crossroads, strained by the principle of adherence to a long‐standing operational framework, on the one hand, and calls to adjust to an environment of changing demands and opportunities, on the other.

Conclusions

For nearly 50 years, Assertive Community Treatment has been a mainstay of community mental health programming in the United States and other parts of the world. This presence will continue, but not in any static sense. A growing number of hybrid and competing versions of the program are likely to develop to serve specialized clientele groups and to respond to consumer demands and the recovery paradigm in behavioral health care.

Keywords: Assertive Community Treatment, policy diffusion, community mental health care, community support systems, deinstitutionalization, recovery model, evidence‐based practice

Assertive community treatment (act), first launched at the county level in Wisconsin in 1972, recently passed another major anniversary, its 45th year of operation as an intensive multidisciplinary program for supporting persons with severe and chronic mental health problems in the community. Marking this approach over the decades has been the painstaking refinement of foundational concepts, documentation of administrative process, a profusion of empirical evaluation in diverse settings, and expansion of the program across the United States into areas of North America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Australia‐Oceania region. More than just another helpful entry within the corpus of techniques making up the field of community mental health care, ACT has gained standing as a transformative package of services and principles, a paradigmatic solution for a sector challenged by rapid deinstitutionalization, uncoordinated bureaucracy, and inadequate resources.

Innovation is a mainspring of progress in public policy just as it is within science, business, industry, and other realms. As stated succinctly in a review of scholarly literature for the journal Health Affairs, “Over time through waves of innovations, diffusion changes societies.”1 (p184) Particularly within social systems wary of centralized problem solving and prizing local experimentation, innovation provides an attractive engine of reform by pilot testing new ideas and tools in tandem with the building of specialized expertise and constituency buy‐in. To a great extent, this pattern describes ACT as it has “changed history,” “improved lives,” and “reinvented” organizations and services inside the mental health domain.2 (p763)

There is, however, another side to this story. Proponents lament that although ACT serves a growing population within and beyond the United States, its availability fails to match the number of people who might appropriately participate. ACT, or ACT‐like programs, have now been implemented in all states, but ACT is seldom a statewide service and geographic dispersion is uneven.3 Waiting lists are common. Based on a sample of administrative data from a large urban county, one study determined that local communities should plan on sufficient ACT capacity to serve approximately 50% of individuals with severe mental illness, or about 0.06% of the adult population.4 A Japanese study, based on a survey of the directors of psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric units in general hospitals, and psychiatric clinics in the city of Sendai, as well as patient evaluations by the primary treating physicians at these same facilities, estimated that between 0.9 and 3.5 ACT teams per 100,000 population were needed, assuming 100 clients per team.5 These and other calculations, however, can only be seen as suggestive given the relevance of such considerations as the supply of resources in a given service system, notably additional alternatives to hospitalization, and provider and consumer affinity for ACT as a treatment option.

Whatever the precise need for ACT may be, few localities seemingly have met that standard. The latest study of ACT distribution in the United States concludes that, nationally, program capacity is sufficient to serve about 40% of eligible adults.6 In Europe, a 2008 survey found that 22 of 42 member countries of the World Health Organization had “policy, plans, or legislation” in place to provide assertive community outreach, a program modality closely based on ACT.7 (p65) Yet only in the United Kingdom (England and Wales) did all eligible individuals have reported access to services, while in 11 countries reporting this information the access level was no greater than 20% of those in need. In short, if ACT expansion attests to diffusion of innovation as a potent force behind mental health system change, ACT containment highlights the vicissitudes of such a movement, including the reality of countervailing influences aligned with the status quo or another prospect for reform.

Despite a number of revealing partial histories, no comprehensive portrait of the evolution of ACT exists, nor is there one specifically concerned with the factors that have stimulated and curtailed growth on an international scale. Drawing on diffusion research from organizational behavior, public policy analysis, communications, dissemination and implementation studies, and other fields, the purpose of this article is to shed light on this topic, providing context for the growing conversation over whether ACT is “here to stay” or likely to recede as other program options advance on the scene.8, 9

ACT Origins and Spread

In the history of mental health care in the United States, the era following World War II marks a watershed in which the circle of leaders, ideas, stakeholders, and bureaucratic entities underwent redefinition. For the preceding 150 years, large custodial public institutions had dominated. The turn toward the community was associated with changing intergovernmental relations; a heightened concern with active treatment and patients’ civil liberties; and the proliferation of new agencies, professional roles, and advocacy interests. In short, this was a juncture when the mental health system expanded in size, changed organizational composition, and confronted new service dilemmas created by an alternate setting of care.

It was under these circumstance that a group of senior clinicians and administrators at the Mendota Mental Health Institute in Madison, Wisconsin, set out to tackle the high rate of readmission among discharged patients.2 This problem they attributed to the inadequacies of an inpatient facility that neglected to provide the treatment and skill building necessary for coping in society. The solution would require not just upgrading services at the hospital but also inventing an unprecedented method of intervention outside the institution.10

The “Madison model” moved through a series of phases from the mid‐1960s, when services were upgraded at Mendota State Hospital to better prepare patients for discharge, to the mid‐1970s, when a full‐blown framework of psychosocial resources was in place within the county for all individuals with serious and persistent mental illness in the public sector. Individually the steps were incremental—relocating patients to the community, expanding community mental health care, adding housing, employment, and other services—but taken together these were changes in degree that amounted to a change in kind. Thompson, Griffith, and Leaf describe the process as a metamorphosis from “individual clinical interventions to systems‐oriented ones.”10 (p631) And, as program architects fleshed out this model and grew more ambitious about its objectives, the name of their venture shifted, from Total In‐Community Treatment, to Training in Community Living (TCL), to Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT). It was under this latter designation, often abbreviated in the professional literature and by adopters as ACT, that general branding of the Wisconsin approach took place.

The model was devised “to furnish the latest, most effective and efficient treatments, rehabilitation, and support services conveniently as an integrated package.”11 (p2) ACT approached the puzzle of the mental health “nonsystem” by creating “a fixed point of responsibility” for meeting all needs of its clients, doing so chiefly in vivo—that is, by going to clients where they lived. Just as important as the multifaceted nature of assistance was its continuity in order for clients to maximize retention of functional gains while averting deterioration over time. A final hallmark of ACT was its method of case management, which featured detailed individualized treatment plans; a team structure with representatives from psychiatry, nursing, psychiatric rehabilitation, social work, and other named specialties; and operational requirements concerning low staffing ratios, amount of service per client, 24/7 crisis coverage, and other explicit management benchmarks.12

Policy Learning Through Research

An essential ingredient in ACT's diffusion was applied research. Recognizing that skepticism would greet a model so challenging to the status quo and its hospital‐based interests (an entrenched administrative‐professional hierarchy, state employee unions, established budget centers), program creators conducted a randomized controlled trial of patient outcomes coincident with TCL's initial implementation.13 Subsequently, research on ACT by these and later researchers grew to prodigious proportions. By 2001, more than 25 randomized clinical trials had been conducted tracking program performance.14, 15 It has been estimated that, between 2001 and 2012, the number of experimental studies doubled again.16 More broadly, a search of the Google Scholar database yields upward of 900 articles with the term “Assertive Community Treatment” in the title. To characterize this research as abundant fails to capture its exhaustiveness or the unceasing scholarly and professional exchange that it enabled. Included are descriptions of the nature, intensity, and structure of service provision in a large collection of ACT programs; analysis of client outcomes according to such indicators as psychiatric symptomatology, use of hospital services, adherence to medications, quality of life, general health, social functioning, employment, and incarceration; and reports on the experience of disparate groups of ACT service recipients, including the young and the elderly, residents of rural communities, participants with co‐occurring mental health and substance use disorders, parents, the homeless, clients of minority cultural backgrounds, and more.

Due to the massive amount of information being gathered, secondary research reviews emerged as a prominent genre of writing about ACT.12, 15, 17, 18 The eventual appearance of a wave of studies with less favorable findings than earlier investigations will be discussed later with respect to factors inhibiting the diffusion of ACT. Here it is essential to note that an initial widespread consensus about ACT's clinical and social value was a critical force behind the program's take‐off and rapid rise in stature within the field of public psychiatry. Upon completing a literature review on behalf of the US Health Care Finance Administration and the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Lewin Group concluded in 2008 that available research “support[ed] the hypothesis that the ACT model is an effective approach to reducing hospitalization, increasing the stability of housing, and increasing the quality of life for consumers.”19 (pp36‐37) The program also produced additional positive outcomes, such as reduction in psychiatric symptoms, seemingly at least as well as rival approaches.

Professional and academic researchers, mental health providers, and public and private administrators all participated in producing studies on ACT. The research appeared in the most eminent journals in the mental health field, publications with an international reach in terms of their contributors, editorial board members, and readership. Often a blurring of roles occurred as individuals collaborated not only in measuring results, but also in starting pilot programs and engaging in policy advocacy to install ACT as a standard part of the mental health system. Johnson criticizes an “incestuous cycle” in which some of the leading researchers who conducted evidence‐based investigations of ACT were also involved with federal agencies in defining the standards for such studies.20 (p139) If the existence of overlapping relationships among researchers, funders, technical advisors, and program administrators was disconcerting to some, perhaps especially to those not included in these formal and informal networks, it illustrates the synergy of intellectual and operational capital that helped to advance applied learning in the diffusion of this innovation.

The centrality of cost cutting in the adoption and subsequent implementation of deinstitutionalization has been widely noted.21, 22, 23 Concerning the spread of ACT, it would have been disadvantageous had the program's treatment value been documented without accompanying examination of spending. An emphasis on economic analysis dating from the early rounds of ACT evaluation reflected this recognition. One of the most comprehensive reviews of studies on this subject, published in 1999, concluded that a dominant finding was the achievement of cost savings due to reduced hospitalization among ACT participants.24 Programs exhibiting the closest adherence to key organizational and staffing components of the original ACT model realized the greatest reductions.

Careful documentation of ACT not only helped spur diffusion within the United States—by 1992 an estimated total of 340 programs functioned in 34 states25—it informed implementation in other countries as well. One of the first foreign applications occurred in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, in the late 1970s. In an editorial in Hospital and Community Psychiatry, the regional mental health advisor responsible for that program wrote: “New South Wales chose the Mendota model because it offers a comprehensive system that incorporates acknowledged good principles of care, has been demonstrated by sound research to be effective and acceptable, and is economically feasible. No other model offers this combination.”26 By 2000, the British National Health Service had designated “assertive outreach” a necessary component of community mental health programming. Writing in a journal published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2 university‐based consultants affirmed that Assertive Community Treatment “has influenced service development internationally,” which they linked to “the rigorous manner” in which the program had been evaluated.27 Reports describing ACT in the Netherlands,28 South Africa,29 Japan,30 and other countries professed a similar debt to the large compendium of information on treatment principles, program design, and administrative practice.

Peterson writes that in health care, “replication of research results and the emergence of a consensus position among credible analysts make it more likely that the research‐evidence message will be heard and seriously weighed by policy makers.”31 (p368) So it was with ACT. Indeed, ACT investigations, many of them funded by the US federal government and major private foundations, were emblematic of the rise of evidence‐based research and its real‐world impact inside the health policy domain over recent decades.32

Role of Policy Entrepreneurs

Analyses of policy innovation and diffusion frequently highlight the role of “policy entrepreneurs.” According to Kingdon, a policy entrepreneur is an actor who focuses attention on a problem, molds its definition, mobilizes support behind a particular solution, and works for adoption by decision makers.33 Policy entrepreneurs can be individuals (subject matter experts, elected officials, established issue advocates) or groups (professional organizations, community organizations, a government office or agency).1, 33 Whatever the source, the function of entrepreneurship remains the same, that is, exploiting opportunities to enhance awareness of a cause while strategizing the path to institutional action.

In regard to ACT, some of the same actors responsible for launching the Madison model went on to actively promote dispersion of their technology. Most visible in playing this entrepreneurial role were Drs. Leonard Stein, Mary Ann Test, and William Knoedler and psychiatric social worker Deborah Allness. As mental health clinicians who were also experienced administrators and researchers, the group had much to share with those curious about the setup and maintenance of ACT. They wrote prolifically on this topic, lectured, gave conference presentations, responded to requests for advice, made site visits, and prepared manuals and videos, all for the purpose of bringing ACT “into the therapeutic mainstream.”2 (p762) Significantly, when authors of the program standards for ACT in the Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care in Ontario, Canada, completed their work, they thanked researchers associated with the Wisconsin initiative for permitting Canadian authorities to borrow materials from US standard setting.34

The most insightful and thorough discussion of ACT from a political science perspective is Johnson's examination of program adoption in New York and Oklahoma during the first decade of this century.20 In both settings, a major part was played by state and local policy entrepreneurs, situated inside and outside of government, who assembled strong coalitions of supporters while arguing ACT's scientific grounding, reasonable financing requirements, and operational successes elsewhere.

Undoubtedly, the most politically influential supporter of the ACT model over the years has been the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), a private advocacy group with hundreds of chapters and affiliates in the states. Founded in the late 1970s with a membership consisting “first and foremost [of] parents of mentally ill people,” NAMI's formation was a reaction against the rapid deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals that was perceived to be shifting the “major burden of care” to families of discharged patients.35 (pp99,101) The group called for expanded community support services, while advancing the tenet that “families should be involved in treatment decisions.”36 (p215) NAMI's ideology has been described as “diametrically opposed” to the views of the nascent mental‐health‐consumer movement in this period on such issues as professional authority, involuntary treatment, and self‐help, among other core questions.36 (p215) ACT won praise from NAMI for the comprehensiveness and intensiveness of its service approach as well as the focus on reducing clients’ risk of hospitalization, homelessness, and incarceration. In 1998 NAMI publicized a “PACT across America” campaign on its website, setting a goal of nationwide dissemination by 2002.20, 37 In addition to making available a technical assistance manual for ACT programs, the organization provided expert telephone and on‐site consultation for groups interested in launching ACT services.

A porous membrane separated private and public action inside this domain. In one partnership, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, a group representing state mental health agencies, contracted with NAMI to provide “targeted technical assistance” on the state level to actors interested in learning about or developing ACT.38 Similar to NAMI's use of technical assistance as a stimulus behind program expansion, SAMHSA, a federal agency, published an “Assertive Community Treatment Evidence‐Based Practices Kit.”39 As part of these materials, the agency recommended NAMI as a valuable source of additional information on program options. In time, through Title IX of the Mental Health Cures Act of 2017, SAMHSA came to possess its own modest funding stream with which to stimulate ACT program development. Under a grant program that began in 2018, it is expected the federal agency will award as many as seven grants of up to $678,000 annually over the next five years.40 In this way did policy entrepreneurship make the journey from advocacy, to the brokering of instrumental know‐how, to resource distribution. It also shows the extent to which, rather than leaving diffusion to simple contagion or advocacy at the subnational level, strategically situated national actors worked to grow the ACT program. This commitment by the federal government to usher evidence‐based services into general practice, collaborating with stakeholders in different sectors while offering information, aid, and other inducements, anticipated, on a smaller scale, the backing for new health service payment and delivery models soon to be seen under the Affordable Care Act.41

ACT's Acceptance as a Normative Standard

Innovations present both promise and risk. Even when a program like ACT is bolstered by favorable administrative reports and research findings, the question faced by a potential adopting entity is, will it be worthwhile here, for us? There is no way to resolve this quandary short of finding out firsthand. Nonetheless, the will to plunge ahead can be fortified by an authoritative consensus designating the prospective innovation as “good” policy in practical and ethical terms. Berry and Berry refer to this diffusion factor as “normative pressure.”42

An early boost for ACT came in 1974 when the Wisconsin program received the Gold Achievement Award from the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Accompanying this honor was a write‐up in the journal Hospital and Community Psychiatry that stated: “The results to date indicate that the community living program is a feasible alternative to mental hospital treatment. It has greatly reduced time spent in hospitals and the resulting social stigma, disruption of life, and reinforcement of dependency without increasing the burden to the patient's family.”43 (p672) A quarter century later, the same journal (renamed Psychiatric Services) published a glowing follow‐up proclaiming that “the Gold Achievement Award winner of 1974 has set the gold standard for creative program development, rigorous evaluation, and ongoing adaptation.”2 (p763)

APA's honor proved to be the first among many endorsements of ACT by important professional, academic, and government groups. A partial listing includes the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT),44 Dartmouth University's Evidence‐Based Research Project,45 the US Surgeon General's Report on Mental Health,46 and President George W. Bush's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.47 On the international stage, recognition has come from the World Health Organization,7 as well as the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development.48 ACT's repeated identification as a model deserving of widespread scrutiny and imitation constitutes a mainstay of its credibility, not to mention an estimable asset when the program has undergone appraisal by potential new sponsors. The PORT study was cited as a major influence behind President Clinton's decision to approve Medicaid reimbursement for ACT services in 1999.20, 49 ACT's reputation as one of the most progressive and effective modalities of community mental health programming also subsequently led to its inclusion in agreements between the Justice Department and states that were judged to be in violation of the Supreme Court's Olmstead decision of 1999 affirming the right of persons with disabilities to community‐based services.50

If compliance with normative pressure is often attributed to such explanations as learning and idealism, it also intersects with other factors in policy diffusion, those of imitation and competition.42 When NAMI produced a ranking of state mental health programs in 2009, it cited Assertive Community Treatment as an integral service in the maintenance of a “high‐quality mental health system.”51 While inclusion in a landmark national report of this kind added weight to ACT's normative standing, the assignment of comparative grades was also a strategy by NAMI for goading states into action. Going forward, those seeking to improve their performance rating—and public reputations—understood that adoption of ACT offered a means to these ends.

A Thriving Epistemic Community

Recent analysis of the transfer of public policies and programs across national boundaries has focused on the role of groupings of experts, professionals, and government actors who “form common patterns of understanding” about an issue due to information sharing and regular interaction with each other.52 This phenomenon goes beyond policy entrepreneurship because attention rests not on particular sources of advocacy and mobilization, but rather on an enduring network of actors, possessing some degree of group identification, that gives sustained consideration to a policy option while monitoring progress across different societal contexts. Epistemic community and transnational policy network are two terms that have been applied to these circumstances. Stone observes that structures of this kind “represent a soft, informal and gradual mode for the international diffusion and dissemination of ideas and policy paradigms.… Through networks, participants can build alliances, share discourses and construct consensual knowledge.”52 (p14)

ACT diffusion occurred internationally through a push‐pull dynamic in which it has often been impossible to judge where the preponderance of energy and motivation resides. On the “pull” side, interested providers and organizations seized the initiative by seeking out the copious data about ACT available in publications, on websites, and by consultation with the personnel of established programs. On the “push” side, activist groups in the mental health domain committed resources and offered opportunities meant to stimulate ACT's global spread. In the early 1980s, the Assertive Community Treatment Association (ACTA) was formed to “promote, develop, and support high quality assertive community treatment services.”53 Membership included mental health providers, service recipients and their families, public officials, and mental health advocacy groups. The organization's primary activity was an annual ACT conference. In her introductory message printed in the 2011 conference program, the ACTA executive director boasted: “This year, over 110 presenters from across the nation and around the world will share their experiences and expertise in ACT.”54 Workshops at the 2012 ACTA conference in Boston included “ACT Rocks: A Collaborative Newfoundland Perspective” and “A Comparison of Three ACT Teams in Maine and New Zealand.”55 (In 2016, ACTA disbanded and was succeeded by another group, the ACT Conference Planning Committee, dedicated to resuming an annual international conference on ACT.)

The European Assertive Outreach Foundation has now held five conferences with its first in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in October of 2011. According to the Congress Program Booklet for the latter, the aim was “to stimulate a European‐wide dialogue about the development of evidence‐based models of Assertive Outreach (AO).”56 The meeting consisted of several dozen oral and poster presentations over three days, all concerned with the structure and performance of the ACT model, its variants, and allied services. Many country examples were discussed, mostly European, although presenters from other nations also attended, including the United States, Canada, and Hong Kong (China).

Another example of transnational ACT promotion is the role played by an international public/private alliance named the International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership (IIML). IIML is a collaboration among eight countries—Australia, England, Canada, New Zealand, the Republic of Ireland, Scotland, the United States, and Sweden—for improving mental health care and addiction services on an international scale.57 IIML is a “government‐to‐government” initiative. All member countries are represented by national government agencies from the mental health and substance use domains with organizational funding by member fees. Interestingly, the IIML itself is a nonprofit American corporation. The instruments by which this group has pursued its agenda include a weeklong Leadership Exchange every 16 months, workshops and training, sharing of best practices, and research collaborations, all of which serve as valuable methods of “knowledge transfer.” One report sponsored by the group was titled International Comparative ACT Study Process and Data: How ACT Teams Compare in Toronto, Birmingham, Nashville and Auckland.58 It summarized a four‐nation project overseen by IIML and based on meetings and teleconferences with the participants.

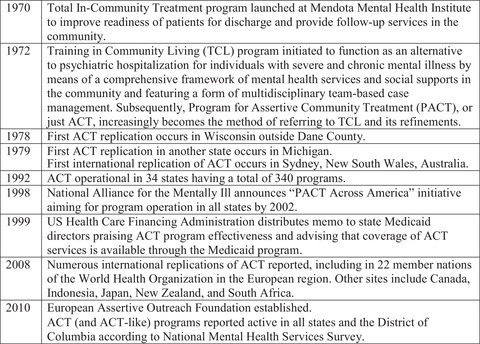

Figure 1 lists chronological highlights of ACT diffusion from 1970 to 2010.

Figure 1.

Selected Developments in the Establishment and Diffusion of Assertive Community Treatment, 1970–2010

Factors Constraining ACT Diffusion

Parallel to the constellation of forces encouraging ACT expansion, one can identify opposing factors. These include cost concerns, fidelity demands, shifting norms, and research contradictions and gaps. Past research on diffusion of innovation also indicates that a convergence of multiple conditions—political, organizational, and ideological—must typically be present for a program with high barriers to entry like ACT (novelty, complex service start‐up, multiorganizational relationships, specialized training and recruitment) to take root in new soil.

Cost Concerns

Cost‐effectiveness studies of ACT tended to approach the issue of cost from a systemic perspective whose focus was not necessarily the incidence of different forms of spending, nor affordability for the institutional actor(s) most directly involved in program adoption and operation. Therefore, despite the generally encouraging message associated with this vein of research, cost was a paramount factor limiting program diffusion from the outset, and it has remained so over time. A comprehensive guidebook to ACT published in 1998 described how program founders Leonard Stein and Mary Ann Test repeatedly encountered this issue:

Drs. Stein and Test … correctly anticipated that they would be questioned about the cost of this treatment as compared to traditional treatment. They were correct in this assumption. Indeed, the scenario that they envisioned happened over and over again: They would present their findings showing a positive clinical outcome and, inevitably, among the first questions asked after the presentation would be the following: “It all sounds well and good, but aren't the costs prohibitive?”11 (pp21‐22)

The combination of clinical and economic advantage buttressed the case for ACT far better than either factor alone could have done as program proposals moved beyond mental health practitioners and administrators to undergo scrutiny from elected officials and budgetary gatekeepers. Historically, mental health service expansion has faced a high burden of proof for necessity and affordability due to the social issue of stigma.59, 60 Over the past decade, sharp declines in the number of inpatient hospital stays have occurred within many illness areas, but not mental health and substance use.61 This development has also contributed to expectations that ACT should reduce expensive hospital stays.

The problem of how to finance ACT has, in fact, been a complex one.62 Within the US context, the adopting jurisdiction or agency must resolve such questions as: Will Medicaid be accessed? If so, by means of which available funding options or waivers? Will there be cost sharing between the state and local communities? Will other state departments, beyond the mental health authority, accept responsibility for paying for ACT services? These financing choices hinge, in turn, on an additional series of decisions about “statewideness,” whether the ACT model will be adopted in whole or in part, and phase‐in strategy for the program.

In some respects, the very pluralism of US health care works at cross purposes with the incentive of cost savings from ACT. In the absence of a consolidated structure integrating providers and payment sources, those systemic entities implementing the program may differ from those benefiting from its efficiencies.63, 64 Prospective payment, or the allocation of a fixed sum for patient care while providers determine the services delivered, is a commonly recommended remedy, although not one easy to work out when it comes to details like capitation rates, risk corridors, and protection against excessive cost cutting.

The first major hurdle in regard to ACT financing is covering start‐up expenses for the program (administrative and service infrastructure) before operations begin and hoped‐for cost savings can be obtained. Experience has shown that, once under way, programs tend to be vulnerable to rising financial pressures in such areas as hiring and retaining qualified staff, contracting for services, and meeting the demand for care.19 Even the Dane County program in Wisconsin encountered budget overruns leading to temporary layoff of staff members in the 1980s.10 ACT services have been identified as one of the mental health budget items most likely to be slashed when states enter periods of fiscal distress.51, 65 Medicaid reimbursement offers limited protection against this threat, since the program covers only some ACT services, and state matching is required. Johnson found that some state administrators welcomed Medicaid payment for ACT to the extent that it enabled cost shifting for services already provided by the state; otherwise, they favored containment of ACT‐related spending.20

On the international scene, the funding issues surrounding ACT are as varied as the national contexts in which consideration of the program has occurred. In areas of the world where resources are most scarce and poorly distributed, the cost threshold to incorporating a program like ACT into a developing health system can be insurmountable. Writes one research group from Ethiopia: “For most low‐income African countries, achieving adequate population coverage with any kind of mental health care provision has been problematic, resulting in high treatment gaps for even the most severe mental disorders.”66 In central and eastern Europe, where signs of increasing interest in ACT are present, resource‐allocation arrangements remain centered on institutional care resulting in “little flexibility and . . . little incentive for local planners to develop community‐based alternative services.”67 (p11) Even under a single‐payer system with universal coverage like Canada's, where several provinces made an early commitment to ACT and the program now exists in nearly every part of the country, waiting times for ACT services reach several months due to budgetary limitations.68, 69

Fidelity Demands

As noted, the documentation of positive results went far toward inspiring confidence in the value of ACT while hastening its replication. However, ACT diffusion also raised difficult questions for researchers. How should the program, with all its constituent elements, be defined and gauged operationally as it became established in new venues?70 Which ingredients are central, and which are peripheral, in achieving successful adoptions with desired effects? This question cuts to the heart of ACT expansion and, more broadly, the burgeoning field of dissemination and implementation science, with its defining interest in the gap between evidence‐based research and treatment practices in health care.71 It also speaks to the concerns of public and private funders who, having backed ACT research and program development, look to see results from their investment.72 As the research effort surrounding ACT matured, many investigators chose to concentrate on issues of replication, first by formulating, then by applying, fidelity as a key variable of interest in their studies. Most well known among relevant instruments was the Dartmouth ACT Fidelity Scale (DACTS).70

Fidelity's allure as a critical ACT concept traveled quickly to the oversight arena. Criteria‐driven checklists, based on recent research in conjunction with expert opinion, were embraced by numerous groups active in consulting for, monitoring, regulating, and funding the program. Illustrations include NAMI's national standard setting for PACT,73 SAMHSA's toolkit project,62 the formulation of certification and licensing guidelines by state authorities,74 federal regulations for coverage of ACT services under Medicaid,75 and the international accrediting standards of the Commission for Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities.76 This drive to codify and systematize ACT signaled a progression from evidence‐based research to “manualized practice,” or the use of manuals and workbooks to direct program replication according to precise instructions for planning, structuring, and maintaining operations.77 (p4) While the promised benefits of manualized practice for program adherence seem self‐evident—if unproven—cited disadvantages include inflexibility, an emphasis on technique over theoretical understanding, and the prioritization of management considerations over clinical judgment.

Fidelity to an original model is a classic issue in the literature on program diffusion. Careful measurement of this attribute has been recognized as fundamental in any research on the relationship between an intervention as ideally conceived and its outcomes in practice. As stated by Carroll et al., implementation fidelity “can give primary researchers confidence in attributing outcomes to the intervention; evidence‐based practitioners can be confident they are implementing the chosen intervention properly; and secondary researchers can be more confident when synthesising studies.”78 However, the failure to meet fidelity demands is not uncommon during program implementation. One reason is resistance by program adopters who make changes to enhance an intervention's compatibility with idiosyncratic conditions, or to configure it for “scaling up” to more complex and high‐demand circumstances, as when pilot research is moving into general practice. Adjustments may happen either by means of “reinvention” during the preliminary design phase of the adoption process or by “course corrections” during a program's implementation phase.1 Those who originated the innovation may not favor such alterations, but adherence expectations that are perceived to be obligatory as well as extreme can prevent new actors from giving serious consideration to an otherwise appealing option.

In her study of New York and Oklahoma, Johnson reported resentment among field staff with respect to the strenuous fidelity demands imposed on their programs, which they saw as top down, bureaucratic in nature, and often conflicting with ground‐level experience. An official in one state linked researchers and policymakers to “a new knowledge regime” in community mental health practice that was disconnected from reality.20 (p141) During the early 2000s, Knudsen compared ACT in the low‐adopting and high‐adopting states of Pennsylvania (only one program) and Michigan (approximately 50 programs).79 With respect to the former, diffusion was hampered not only by funding considerations but also by the desire to preserve a model of community treatment and support that deviated from the ACT blueprint. Ultimately, the label of ACT was avoided in Pennsylvania to sidestep fidelity standards, a strategy described by Knudsen as familiar in many programs across the country.79 (p129) The experience in Pennsylvania also suggested that, when major compatibility concerns surround ACT, the effect can be to confine adoption to partial state implementation, possibly only a pilot program, before greater systemic changes are attempted. Among dissemination and implementation researchers, the concept of fidelity is seen as “critical to understanding whether the failure of an intervention is attributable to poor or inadequate implementation … or to intervention program theory failure, or some combination thereof.”80 (p281) But the mixed record of ACT diffusion showed another side of the coin: the reality that actors in some organizations and locales saw value in something beyond evaluation research and orderly inclusion in an increasingly regulated national movement. Like the original program architects in Dane County, they desired a meaningful degree of ownership in the implantation of ACT such that it could respond creatively to observed prospects and needs.

Shifting Norms

Responding to a haphazard process of deinstitutionalization, ACT redistributed and added resources to fulfill the community mental health revolution for those having the greatest psychiatric and economic needs. It was both a medical and social intervention in which, to many observers, professional expertise and moral impulse seemed to coincide. The vision of the program, no less than its services, gained tributes. Yet times changed.

By the final decade of the 20th century, an alternate vision was recasting the mental health sector. An outgrowth of the psychiatric survivors’ movement, as well as approaches from the field of psychiatric rehabilitation, the “recovery” movement cultivated a strong consumer orientation to mental health care, emphasizing control over the goals and content of treatment by the individuals receiving assistance, along with reduced dependence on the formal service system.81 The extent to which this recovery concept has gone on to achieve standing as a new norm is indicated by its endorsement, in principle, in the final report of President Bush's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health,47 high‐profile statements from SAMHSA,82 California's Mental Health Services Act (revised),83 and the Affordable Care Act.84

Integration of the recovery model into ACT is under way, albeit with a degree of variation in methods and comprehensiveness to be expected from such a geographically diverse venture. Research evaluations have mounted in tandem with administrative retooling, but time will be needed to assess the empirical evidence and only a partial summary is possible here. An early exploration of whether ACT teams could embrace recovery‐oriented clinical and organizational practices, together with related new norms, attitudes, and values, found points of conflict with respect to mandatory versus voluntary participation in the program, client versus staff decision making, use of medications, methods of crisis intervention, length of stay in the program, the role of peer support, and other items.81 While researchers did not conclude the ACT model and recovery approach were incompatible, they stressed the challenges raised by a proposed combination of the two. A subsequent review of 16 studies focusing on the inclusion of consumer‐provider services as part of ACT identified mixed results, with generally positive outcomes for enhanced client engagement in treatment programs, promising though weaker evidence for reduced hospitalization, and unproven effects in regard to “symptomatology, or satisfaction with services.”85 (p40) Lack of rigor in the design of several studies hindered a more definitive synthesis. One study from Ontario, Canada, published in 2011 and described as “the first large‐scale empirical examination of the relationship between recovery‐oriented service delivery and client outcomes,” compiled client, family, staff, and manager ratings of the performance of 67 ACT teams.86 Given the number of variables measured across clinical, personal, and social domains, among multiple categories of respondents, the findings were complex but, overall, “modestly” indicative that “recovery‐oriented service provision is related to better client outcomes in ACT.”86 (p199) A more recent report, published in 2016, reviewed 16 empirical studies on recovery and ACT.87 These authors confirmed that the new recovery orientation of ACT programs is discernible to different stakeholder groups, if in varying ways; that improvements are occurring within fidelity tools and techniques for measuring recovery‐based ingredients; and that ACT teams consciously and specifically aim at the achievement of recovery objectives for program participants. However, they also cited a dearth of relevant literature in the area of their review: “The existing empirical literature is not sufficient in the quality of research methods or the quantity or strength of findings to unequivocally resolve the controversy concerning ACT and recovery.”87 (p224)

On the sharp edge of the recovery/ACT dispute lies the issue of coercion. Defenders of ACT reject the claim that coercion is a part of the program while conceding that instances of paternalism or “aggressive” practice may occur due to the intensity of staff involvement in clients’ lives and the need for vigorous response when dire situations of need and risk arise.88, 89 Critics of ACT maintain that coercion is intrinsic to both the service strategies and the viewpoint of the program, which render it antitherapeutic and, in the broadest sense, antirecovery. Gomory has described ACT as profoundly shaped by the public mental hospital environment from which it issued and reflecting the institutional mentality of professional dominance, limited patient rights, and patient‐blaming theories and interventions.90

ACT has always faced an amount of wariness and even resistance from clients if for no other reasons than the persistent demands of the program and the fact that the program is not, strictly speaking, always voluntary. From the outset, the program was designed to be highly intensive in terms of staff‐to‐client ratio and frequency of staff contacts, with the substance of these contacts firmly task‐specific and goal‐directed in numerous areas conceived as beneficial for ACT participants. The latter includes daily self‐care activities; family and social relationships; money management; preparing for, seeking, and maintaining employment; and compliance with health and mental health treatment recommendations, including medication. The protocol for discharge from the program is elaborate. In their review of ACT operational standards in Dane County, Wisconsin, Stein and Santos underscored that “the simple wish of the client to be discharged from the service” is not a sufficient criterion for exit, although it is “not unusual for clients in ACT programs to express a wish to be discharged.”11 (p105) They went on to advise that, when a client has protested that “he or she wants nothing further to do with the program,” it is a situation that “almost never occurs with a client who will do well without the program.” Currently, the degree to which client preferences guide discharge decision making varies in rules and regulations for ACT across the states but, aside from circumstances such as death, relocation, hospitalization, and incarceration, it is never a straightforward process if the individual has not yet achieved the treatment goals of the program. In addition, some ACT clients have entered the program under legal diversion agreements in assisted outpatient treatment decision making.91

The significance of the recovery movement is that it has supplied a coherent basis for program opposition on clinical and humanitarian grounds, offering a counterparadigm for what living with serious mental health problems could mean. Reflecting this perspective, in mid‐2000 Daniel B. Fisher and Laurie Ahern, cofounders of the National Empowerment Center, a recovery‐oriented mental health advocacy and peer‐support organization, outlined a Personal Assistance in Community Existence (PACE) program. They explained: “PACE is proposed as an alternative to PACT (Program in Assertive Community Treatment) whose emphasis on the medical model of coercion and lifetime illness interferes with recovery and prevents most consumer/survivors from seeking services.”92 (p87) As views of this kind gained traction in hearings and other advisory contexts related to ACT adoption, it has exacerbated the divisions between—and sometimes within—groups of consumers, family members, professionals, state officials, and other stakeholders. Knudsen reported in 2003: “The prevailing image of ACT program staff forcing medications and employment on consumers has dealt a deadly blow to the program's introduction in some states.”79 (p135)

Research Contradictions and Gaps

Positive research was a cornerstone in the edifice of scientific grounding and professional validation that buttressed ACT's position in the US mental health system and abroad during the latter part of the 20th century. Its extensive research record continues to be a prominently cited feature of the program. One of the latest literature summaries about ACT, prepared in 2017 for SAMHSA's National Registry on Evidence‐Based Programs and Practices, examined 11 reviews and meta‐analyses on ACT encompassing 50‐plus experimental studies from 1975 to 2010 in the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The overall conclusion was that “this vast body of experimental literature illustrates a diversity of effects produced by ACT care in mental health symptoms, hospitalization duration and frequency, substance use, housing, employment, and quality‐of‐life outcomes.”3 (p5)

Nonetheless, as the body of ACT research findings has grown, it has become varied to the point of contradiction on a number of key issues. Scholars have cast doubt on the methodological quality of prominent studies. The Lewin Group report was among the earliest to register concern that, although the ACT model overall was associated with worthwhile effects, “there is little empirical evidence indicating precisely how the program components interrelate to produce desirable outcomes.”19 (p4) This quandary is an inherent one in the study of health service programs that are “complex interventions,” as noted in the “Methodology Standards” of the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), a nonprofit foundation brought into being by the Affordable Care Act.93 Multiple program components, with disparate purposes, theoretical bases, mechanisms, and intensity, require corresponding intricacy in the conduct of process and outcome research. This standard of sophistication has not proved easy to meet within the ACT research effort even as a spate of studies has sought to clarify the program's “critical ingredients.” With researchers publishing inconsistent results, core components of the original model have sometimes fallen to the wayside, including the principle of time‐unlimited support for ACT clients.94 Increasingly, research studies have identified adaptability as an essential element in ACT functioning, although this quality can conflict with the master concept of fidelity and the oversight regime it has spawned.

McHugo et al. pointed to “myriad” weaknesses in services evaluation research on ACT, including inadequate sampling, lack of contrast between research and comparison groups, neglect of the content of services, narrow measurement of program outcomes, and deficient data analysis. For these investigators, such problems left “the relative effectiveness of ACT undecided.”95 (p258) Similarly, the validity of prior cost‐effectiveness research on ACT has come under criticism due to poor cost‐estimation procedures, small samples, the impact of any general trends in psychiatric hospitalization (aside from the impact of a community‐based intervention like ACT), and inattention to the indirect and social costs of the ACT program.3, 96 For the next generation of outcome studies, there is need for greater sophistication about the nature and precision of the comparison between ACT and other service programs. Whether that comparison group includes clients in “standard care” or some alternative innovative treatment modality, the meaningfulness of results will be limited in the absence of careful differentiation of program features and categories of participants. Another area often neglected by researchers has been the managerial and strategic challenges surrounding implementation of ACT.20, 97

A different line of questioning, not so concerned with methodology but equally fundamental from another angle, relates to the evidence‐based practice (EBP) movement. Johnson describes the monopolization of the research process that occurred when some of the same people conducting EBP research on ACT were those formulating the definition of the program.20 (pp139‐140) In her discussion of the “epistemological politics” of mental health, which applies to research on community mental health programs like ACT, Tanenbaum has expressed misgivings about EBP's restrictive definition for credible data (ie, primarily randomized clinical trials); the uncertain connection between EBP research findings and their subsequent use in clinical and programmatic activity; and disputes among researchers, providers, and patients about the core concept of treatment effectiveness.32 All of these issues are potentially problematic for ACT and the distinction it has gained as an exemplary EBP intervention. Further, Gomoroy argues that the program's major claim to empirical success—the reduction of hospitalization and inpatient costs when compared to a control group—reflects “a fairly strict administrative rule not to admit or readmit any ACT patients for hospitalization regardless of the psychiatric symptoms, but to carry out all treatment in the community” (italics in original).98 (p79) Seen in this light, the program's positive research findings would seem to derive, to some extent, from fixed protocols. The key question, then, becomes not simply “what has worked?” but “how?”

Where the controversy over ACT research has gone farthest, and had the greatest programmatic impact, is the United Kingdom and mainland Europe. By the end of the first decade of this century, a substantial number of studies, some of them involving large numbers of participants across multiple sites, failed to support pivotal claims in the ACT literature, among them the reality of reduced hospitalization rates as well as the significant role of model fidelity in producing positive program outcomes. Burns summarized, “There has been no high quality ACT trial demonstrating hospitalization reduction for over a decade and none ever in Europe.”9 (p133) The consequences for ACT implementation have ranged from abandonment, to increased investment in rival services, to the development of hybrid models combining ACT with other types of community support. A widely noted example is Flexible Assertive Community Treatment. Initiated in the Netherlands and subsequently active in other settings, the program incorporates different structural components and methods for the most severely mentally ill versus stable long‐term patients. A number of recovery‐oriented elements are also included.99, 100

A Multifactorial Process of Program Adoption

To appreciate the potential barriers to ACT diffusion, it is not sufficient to examine obstacles individually. Adoption decisions are always multifactorial in character, with acceptance requiring convergence among a variety of forces. This observation is consistent with scholarship on the dynamics of program diffusion. In his classic study, Rogers concluded that adoption outcomes depend on numerous variables, which he categorized in terms of attributes of the innovation, characteristics of adopters, and social and political context.1, 101 Further, the decision in favor of, or against, an innovation is typically a comparative one, since rarely are competing or complementary proposals absent from a given policy space. With respect to ACT, Knudsen confirmed the utility of Rogers's framework for explaining the behaviors of a high‐adopting state and a low‐adopting state, although particular factors differed in importance across the two settings.79

Johnson also emphasized the contingent nature of ACT adoption. Drawing on Kingdon's model of public policy innovation, she considered how the different “streams” of problems, policies, and politics must come together for the window of possibility to open. Her case studies of ACT in New York and Oklahoma support the principle that “policies are not made in a socioeconomic vacuum and, more importantly, require a buy‐in from institutional, cultural, political, and economic players.”20 (p51) Of critical importance is the role of situational leadership, by policy entrepreneurs and other public and private figures, in “coupling” the forces and actors at play. Similarly, context occupies a foremost place within implementation research studies and includes “the social, cultural, economic, political, legal, and physical environment, as well as the institutional setting, comprising various stakeholders and their interactions, and the demographic and epidemiological conditions.”102 From this standpoint, “The large array of contextual factors that influence implementation, interact with each other, and change over time highlights the fact that implementation often occurs as part of complex adaptive systems.”102

Early replications of the ACT model illustrate the probabilistic and opportunistic aspects of program adoption. In Wisconsin, where there was strong support from the state Office of Mental Health, it took until the mid‐1980s for staff from Madison to provide consultation to other county community mental health programs statewide, and this level of assistance was not maintained even as some new community support programs underwent deterioration and needed guidance in redeveloping services.103 In Wisconsin's neighboring state of Michigan, an intermingling of propitious circumstances—bureaucratic, budgetary, managerial, legal, and political—tipped the balance in favor of ACT.104 Key figures involved in importing the program conceded that “circumstances and timing” together determined success. In general, diffusion research distinguishes between early and late adopters of innovation, with the former possessing greater readiness for change due to their “structural position in the network of advice‐seeking and advice‐giving relationships that tie a social system—an organization, community, or virtual network—together.”1 (p186) If it is true that “laggards” face an easier decision accepting a program like ACT due to all that has come before, new reasons for rejection also come to the fore with the passage of time.

ACT Past, Present, and Future

On the macro level, empirical scholarship reveals that the vast majority of innovations fail to diffuse to a noteworthy degree.1 Many innovations that do diffuse are discontinued due to inflexible design, disappointing performance upon implementation, declining support from stakeholder groups, changing organizational leadership or capacity, and other reasons internal and external to an adopting organization.105 ACT has beat the odds with its impressive level of adoption within and across states as well as internationally. The program has managed to address a perceived need, hold wide appeal, and be judged operable in diverse settings. Recent years have even seen the offering of ACT services, on a limited basis, to those with private insurance and self‐paying patients in the United States.106

In the literature on diffusion of innovation, the dominant model is an S‐shaped curve predicting that adoptions will occur slowly at first, increase rapidly over time, and eventually decelerate.1 Underlying this model is the assumption that potential adopters are individuals in a social system with a fixed population limit. No major punctuating factors are assumed either to foster or to block diffusion. To the extent that conditions depart from this scenario, however, other models may become necessary. Similar to other instances of public policy development, heads of organizations and government officials have been the ones making program‐level adoption decisions for ACT, not individuals.42 (pp314‐317) Institutional data gathering and collective learning are consequential realities within such an adopting community. Further, the conditions facilitating innovation have shifted suddenly at times due to actions by sectoral stakeholders not directly involved in the adoption decisions. The decision by the National Alliance on Mental Illness starting in the late 1990s to promote ACT dissemination, and the choice by the US Health Care Financing Administration around this same time to encourage federal Medicaid reimbursement for ACT services, provide strong examples of the influence wielded by committed change agents. According to diffusion scholars, adaptations of the basic S curve may be warranted depending on the degree and nature of such externalities during the process of diffusion.107 As late as 2000, the Lewin Group called attention to the still relatively limited adoption of ACT, which it judged understandable in light of the magnitude of policy, cost, and service issues associated with the program.19 (p8) Viewed now, over a period of nearly half a century, the growth pattern seems striking, but the impression remains less that of a smooth S curve than a trajectory in which progressive expansion has combined with step‐like advances due to the intrusion of external stimuli.

The selected observation points concerning growth of ACT in the United States and abroad that were presented in Figure 1 do not allow this diffusion pattern to be plotted in any rigorous mathematical sense. The problems are twofold. First, the history of the program has been, to a great extent, idiosyncratic with no central research or administrative group responsible for tracking of services across local, national, and international jurisdictions. Published estimates of ACT growth, such as they exist, have been intermittent and reliant on different sources and methods, including personal involvement with the program, original databases and surveys, and the secondary compilation of numbers from miscellaneous reports. Second, as emphasized by many researchers on this topic,6, 19, 25 ACT programs differ widely in regard to administrative characteristics and service offerings, making it difficult to draw the line as to when the standard definition of “Assertive Community Treatment” has, in fact, been met.

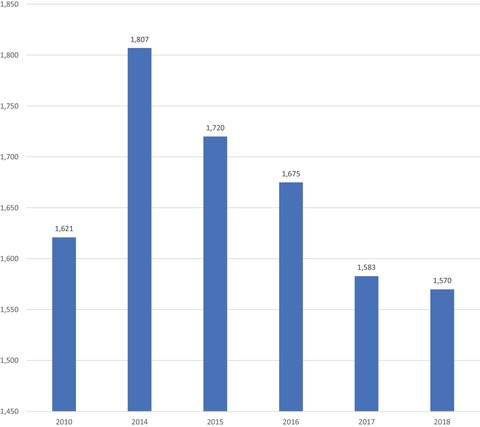

Although not a complete remedy for these data quandaries, the National Mental Health Services Survey (N‐MHSS), begun by the US Substance Abuse and Services Administration in 2010, now provides a readily accessible database on the US mental health treatment delivery system that counts ACT and ACT‐like programs.108 Figure 2 displays data from this source for the period 2010–2018 regarding the number of public and private mental health treatment facilities in the country offering ACT “services and practices.” (The definition of ACT used in this voluntary survey is “a multi‐disciplinary clinical team approach [that] helps those with serious mental illness live in the community by providing 24‐hour intensive community services in the individual's natural setting.”)

Figure 2.

Assertive Community Treatment and ACT‐like Programs Total Number of Public and Private Facilities, United States, 2010–2018

Data derived from National Mental Health Services Survey, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018.108 [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

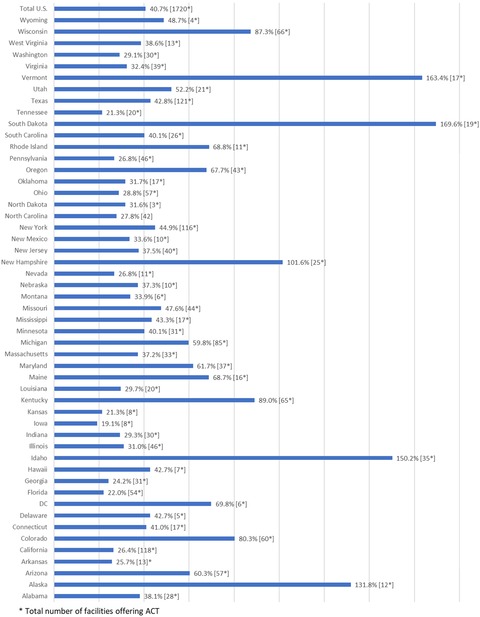

In addition, Figure 3, which is based on calculations produced by Spivak et al.,6 expresses the number of “potential available spots” in ACT programs as a percentage of the number of “ACT eligible” individuals in each state in 2015. (The latter was determined according to the same methodology of Cuddeback, Morrissey, and Meyer4 cited earlier in this paper.) The main findings from this snapshot covering the past few years are these: (1) the number of ACT programs has fluctuated between approximately 1,600 and 1,800 with recent indications of an overall modest decline; the level of unmet need for ACT services potentially remains high (ie, greater than 50%) on the national level; and there is great variation in the relationship between ACT estimated need and service availability across and within regions of the United States.

Figure 3.

Assertive Community Treatment and ACT‐like Services: Program Counts and Capacity as a Percentage of Estimated Adult Eligible Population, United States, 2015a

aData derived from Spivak, Mojtabai, Green, et al., Online Supplement.6 [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Uneven distribution of the ACT program is consistent with interstate variation in social welfare investments across a host of issue areas.109 Resorting to policy instruments such as exhortation, technical assistance, and cost sharing, the federal government has encouraged ACT's spread and done so with palpable results. By 2010, 33 states covered Assertive Community Treatment services for adults under their Medicaid programs, and eight states did so for children.110 Nonetheless, the broad range of resource availability depicted in Figure 3 reminds us that ACT adoption decisions, like most matters of mental health system programming and oversight, remain primarily the province of state actors, with all the bureaucratic, political, and economic factors that hold sway on this level.

Where is the ACT program headed over coming years? Existing empirical data offer no definitive answer to this question. There is reason to speculate that ACT may be in a mature stage of stability, possibly with a degree of contraction. Over a period of 45‐plus years, ACT has had the opportunity to saturate, to a great extent, the audience of actors both interested in and capable of adopting the program. To put this into the language of marketing science and the “product cycle,” ACT has achieved substantial market penetration to date. However, even though need for the product may not be exhausted, hindrances to further diffusion are evident.

When judging how the environment has become less receptive, one can begin on the ideological level with the rise of the recovery movement and its disagreement with ACT program methods and purposes. The significance of this challenge is not merely that it is being fueled by an increasingly articulate consumer movement across the behavioral health sector. Rather, the movement's influence has spread to other groups and institutional stakeholders involved in decision making for the community mental health system. Here it also seems meaningful that, compared to the period of the late 1990s, ACT has become less prominent on the website, conference programs, and public policy declarations of NAMI, its erstwhile champion.

A three‐page NAMI fact sheet on Assertive Community Treatment no longer appears to be available on the group's national website (although state chapters continue to distribute the document). Instead, the national organization now offers a three‐sentence description of ACT as part of a fact sheet on “psychosocial treatments” covering a total of nine different interventions that “provide support, education and guidance to people with mental health conditions and their families.”111

Searches of the NAMI website produce no results for the organization's role as an ACT Technical Assistance Center, for copies of the NAMI publication A Manual for ACT Start‐Up (1998), or for the NAMI publication The PACT Advocacy Guide (1998).

In its latest Public Policy Platform, dated 2016, NAMI addresses ACT but gives it no particular emphasis, citing the program as one item on a list of options that should be made available for outpatient treatment (section 3.5.1)112 and that also should be included in Medicare coverage expansion (section 6.3.3).113

While NAMI's statement of “federal priorities” for the 115th Congress cites ACT, it does so in the context of “end[ing] the criminalization of mental illness.”114

These website adjustments are consistent with a winding down of the “PACT across America” campaign, an effort that could be branded a success in terms of ACT's presence in all states, but not in terms of accessibility for all persons estimated to be eligible for the program. Simultaneously, over recent years, one also notes a sharpened concern with consumer interests and self‐determination in NAMI messaging. As the current Policy Platform affirms on the topic of treatment planning: “In such cases where consumers do not want their family members involved, their wishes must be respected” (section 3.7.7).112

As noted, the degree of compatibility between ACT and the recovery model remains a matter of debate among mental health advocates. One thing is for sure, however. The ability of ACT proponents to address this question of compatibility persuasively, in terms of ethos as well as pragmatic service adjustments, will play a vital role in the program's diffusion and maintenance over coming years. Of potential importance in this regard is the latest tool for measuring program fidelity, called the Tool for Measurement of Assertive Community Treatment (TMACT).115 Based on an extensive revision and expansion of the established DACTS instrument, TMACT was devised to remedy “an emphasis on structure over process” in fidelity assessment and to give increased attention to recovery philosophy and practices. First conceived and piloted in conjunction with the implementation of 10 new ACT teams in Washington State in 2007, TMACT constitutes an innovative component within the larger ACT enterprise that has now, itself, diffused to more than a dozen American states, statewide or regionally, and a small group of other countries. Rather than choosing between DACTS and TMACT, some adopting entities in the United States have retained the former for licensing, certification, or other regulatory purposes while reserving the latter as a tool for quality improvement.116 From a management perspective, the increasing rigor of fidelity measurement not only serves to confirm the presence of key ingredients within ACT program operation but also facilitates payment methodologies that focus on client outcomes, instead of minute tracking of, and billing for, service inputs. The Affordable Care Act has encouraged new payment models under Medicaid's rehabilitative services option, which is the primary resource for coverage of community mental health services with Title XIX. Bundled payments that determine an overall rate for ACT on a daily or monthly basis have surfaced in some states as a creative strategy for promoting flexible, coordinated, and efficient service delivery, although determining an appropriate payment level that prioritizes budgetary restraint without incentivizing reduced care is no simple task, and service monitoring cannot be abandoned.117, 118

The future of ACT, however, cannot be more certain than the health system in which it is embedded. Currently, that overall system is in flux. At times the Affordable Care Act seems to be hanging by a thread, its survival depending on narrow vote margins in Congress and the Supreme Court while a hostile administration calls for repeal and works to undermine the law's functioning. The availability of Medicaid funding for ACT has been a primary condition for program adoption in many parts of the country. Conversely, any rollback of the federal government's support for Medicaid expansion, or a change in Medicaid's open‐ended matching formula, could be damaging to ACT. One signature component of the Affordable Care Act, the Health Homes initiative, has provided added incentives for ACT expansion under Medicaid, although, like many optional features of the Obama health reform, varying state interest and budgetary circumstances limit take‐up.84

The striking thing is how many of the same forces that once propelled ACT forward now undercut its progress. The zeal imbuing the ACT response to deinstitutionalization had its historical moment only to be succeeded by a different kind of reformism, one centering on service pluralism, consumer choice, and increasing doubtfulness about drug treatments, active care management, and other conventional modalities of social psychiatry. The clarity of program fidelity as a road map for ACT replication is anathema to groups enamored with creative alternatives. Similarly, the vigorous research effort that previously enhanced ACT's reputation now raises questions concerning efficacy and quality. Indeed, this uncertainty has reached the point where well‐known scholars in the field observe that ACT no longer possesses “its preeminence as the most empirically supported of all community mental health treatment approaches.”94 (p241) Last, the international epistemic community that provided such a fluid conduit for ACT diffusion now facilitates critical dialogue about the program along with the spread of alternate frameworks.

One important lesson from the history of ACT concerns the nuanced role that government is challenged to play for an innovative program of this type. Government at all levels has aided and abetted ACT diffusion by means of multiple policy instruments, including information exchange, active entrepreneurship, program planning, and direct program funding. At a time when large‐scale deinstitutionalization was disrupting communities while neglecting the basic needs of individuals with severe mental illness, this represented a judicious means of intervening to serve the public good, particularly as ACT's reputation flourished with accumulating research and administrative experience. Yet the ACT program was always a reform in progress. Pressure to meet the reality of varying locations, types of clients, and therapeutic philosophies has been ongoing, notwithstanding attempts to monitor and control the tendency for adaptation. To the extent that government has, at times, favored an overly strict version of fidelity without also acknowledging flexibility, and continued experimentation, as appropriate values for ACT, it has contributed to frustration with the program in some quarters. For a program like ACT—local in origin, initially very small in scale, and steadfast in its commitment to implementing the ideal of community care—there could be no more powerful ally to enlist than government itself, the architect of deinstitutionalization. Government, however, has a bureaucratic character central to its functioning. Relevant here is the example of Medicaid. Coverage of ACT services has done much to make ACT feasible. Yet this benefit comes with the drawback of detailed structural requirements and specifications largely disconnected from, and potentially at odds with, emerging recovery‐oriented strategies.20

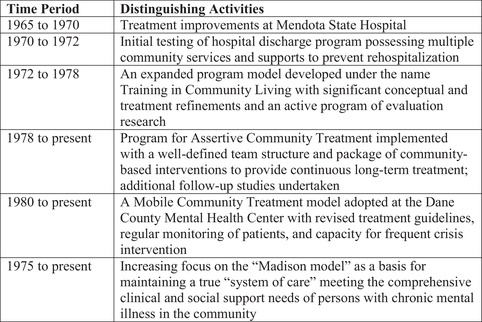

In the sole attempt by scholars to describe, in evolutionary terms, the unfolding of the “Madison model,” six distinct phases starting in 1965 have been proposed as depicted in Figure 4. The last chronological period is an open‐ended one commencing in 1975 and described thematically as the construction of a “system of care” devoted to the vision of “providing continuous and comprehensive community‐based services that addressed all the clinical needs of the chronic mentally ill in the population.”10 (p630) From the vantage point of 2019, and specifically the subject of program diffusion, it is necessary to refine this schema.

Figure 4.

Key Phases in the Madison Model of Community Mental Health Treatment and Support

Data derived from Thompson, Griffith, and Leaf, tables 1 and 2.10