ABSTRACT

Background

Mendelian randomization studies in adults suggest that abdominal adiposity is causally associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease in adults, but its causal effect on cardiometabolic risk in children remains unclear.

Objective

We aimed to study the causal relation of abdominal adiposity with cardiometabolic risk factors in children by applying Mendelian randomization.

Methods

We constructed a genetic risk score (GRS) using variants previously associated with waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for BMI (WHRadjBMI) and examined its associations with cardiometabolic factors by linear regression and Mendelian randomization in a meta-analysis of 6 cohorts, including 9895 European children and adolescents aged 3–17 y.

Results

WHRadjBMI GRS was associated with higher WHRadjBMI (β = 0.021 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.016, 0.026 SD/allele; P = 3 × 10−15) and with unfavorable concentrations of blood lipids (higher LDL cholesterol: β = 0.006 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.011 SD/allele; P = 0.025; lower HDL cholesterol: β = −0.007 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.012, −0.002 SD/allele; P = 0.009; higher triglycerides: β = 0.007 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.002, 0.012 SD/allele; P = 0.006). No differences were detected between prepubertal and pubertal/postpubertal children. The WHRadjBMI GRS had a stronger association with fasting insulin in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity (β = 0.016 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.032 SD/allele; P = 0.037) than in those with normal weight (β = −0.002 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.010, 0.006 SD/allele; P = 0.605) (P for difference = 0.034). In a 2-stage least-squares regression analysis, each genetically instrumented 1-SD increase in WHRadjBMI increased circulating triglycerides by 0.17 mmol/L (0.35 SD, P = 0.040), suggesting that the relation between abdominal adiposity and circulating triglycerides may be causal.

Conclusions

Abdominal adiposity may have a causal, unfavorable effect on plasma triglycerides and potentially other cardiometabolic risk factors starting in childhood. The results highlight the importance of early weight management through healthy dietary habits and physically active lifestyle among children with a tendency for abdominal adiposity.

Keywords: abdominal adiposity, children, waist-to-hip ratio, cardiovascular disease risk, cardiometabolic risk, Mendelian randomization, meta-analysis, ALSPAC

Introduction

Childhood obesity has increased worldwide during the last 4 decades (1) and is associated with cardiometabolic impairments, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in young age (2). Obesity during childhood often tracks into adulthood where it is associated with an increased risk and earlier onset of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (3). It is crucial to fully understand the factors that contribute to increased cardiometabolic risk starting in childhood, in order to develop early interventions and treatment strategies for at-risk groups.

Observational studies in adults suggest that obesity is a heterogeneous condition and that for any given amount of body fat, its regional distribution, particularly when located within the abdominal cavity, is an independent risk factor for cardiometabolic disease (4). In this regard, waist circumference has been shown to add to BMI in risk assessment. A study implementing a Mendelian randomization approach suggested that the link between abdominal adiposity and cardiometabolic risk may be causal (5). Mendelian randomization utilizes the random assortment of genetic variants at conception to reduce and limit confounding and reverse causality (6). When using a genetic risk score (GRS) comprising 48 known variants for waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) adjusted for BMI (WHRadjBMI) (7), a genetically instrumented increase in WHRadjBMI was associated with higher concentrations of triglycerides and 2-h glucose, and higher systolic blood pressure, as well as an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease, suggesting that the relation between abdominal adiposity and cardiometabolic risk may be causal in adults (5). As in adults, increased WHR indicates abdominal adiposity in childhood (8), and gene variants increasing WHRadjBMI have been associated with a higher ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat in children and adolescents (9). However, it remains unclear whether abdominal adiposity is causally linked to increased concentrations of blood lipids and higher levels of insulin resistance and blood pressure among children and adolescents (10–13).

In the present study, we aimed to examine the causal relations of abdominal adiposity with cardiometabolic risk factors by applying Mendelian randomization in a meta-analysis of 9895 children and adolescents from the United Kingdom, Finland, and Denmark.

Methods

Study populations

The present study includes 1) 5474 children 8–11 y of age from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) (14, 15); 2) 2099 Finnish children and adolescents 3–18 y of age from the Cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study (YFS) (16); 3) 705 Danish children and adolescents 3–18 y of age with overweight or obesity as well as a population-based control sample consisting of 361 Danish children and adolescents 6–17 y of age from The Danish Childhood Obesity Biobank (17)—hereafter named TDCOB cases and controls, respectively; 4) 470 Finnish adolescents 14–15 y of age from the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project (STRIP) (18); 5) 460 Finnish children 6–9 y of age from the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) study (19); and 6) 326 Danish children 3 y of age from the Småbørns Kost Og Trivsel (SKOT) I and II studies (20) (Supplemental Figure 1). Details on the recruitment, inclusion criteria, and ethical approvals of the participating studies are presented in the Supplemental Methods.

Children with a history of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, mental or developmental disorders, or monogenic obesity; children with medication for hypercholesterolemia or hypertension; and children of non-European genetic ancestry based on genome-wide principal component analysis (YFS, TDCOB, STRIP, and SKOT) or self-reported ethnicity (ALSPAC, PANIC) were excluded. For twin-pairs, 1 twin was excluded. The categories of self-reported ethnicity in the ALSPAC cohort were “black,” “yellow,” and “white.” The categories of self-reported ethnicity in the PANIC cohort were “Caucasian” and “non-Caucasian.” We excluded all ALSPAC participants whose self-reported ethnicity was “black” or “yellow,” and PANIC participants whose self-reported ethnicity was “non-Caucasian,” owing to these ethnicities being considered to represent non-European genetic ancestry for which the genetic architecture (allele frequencies, effect sizes) differs from European genetic ancestry. The analytic codes for the exclusion of participants in the ALSPAC and PANIC cohorts based on self-reported ethnicity are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Measurements of body size and composition, cardiometabolic risk factors, and pubertal status

Body height and body weight were measured in all studies; BMI was calculated as kg/m2. BMI SD score (BMI-SDS) was calculated according to UK (ALSPAC) (21), Finnish (PANIC, STRIP, and YFS) (22), and Danish (SKOT, TDCOB cases, and TDCOB controls) (23) national reference values. Waist circumference was measured at mid-distance between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest. Hip circumference was measured at the level of the greater trochanters. Body fat mass, body lean mass, and body fat percentage were measured using bioimpedance analysis (STRIP, SKOT) or DXA (PANIC, ALSPAC, TDCOB). Blood pressure was measured manually using calibrated sphygmomanometers (PANIC, YFS) or an oscillometric device (ALSPAC, TDCOB, STRIP, SKOT). Blood samples were taken after an overnight fast in the ALSPAC, YFS, TDCOB, STRIP, and PANIC studies and after >2 h fasting in SKOT. Plasma glucose was measured using the hexokinase method and serum insulin was analyzed by immunoassays. Triglycerides and total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol were measured enzymatically. Overweight and obesity were defined using the age- and sex-specific BMI cutoffs of the International Obesity Task Force (24). In the YFS, TDCOB cases, STRIP, and the PANIC study, the research physician or the study nurse assessed pubertal status using the 5-stage criteria described by Tanner (25, 26). Boys were defined as having entered clinical puberty if their testicular volume assessed by an orchidometer was ≥4 mL (Tanner Stage ≥ 2). Girls were defined as having entered clinical puberty if their breast development had started (Tanner Stage ≥ 2). Among TDCOB controls, pubertal staging was obtained via a questionnaire with pictorial pattern recognition of the 5 different Tanner stages accompanied by a text describing each category. To divide children and adolescents into pre–puberty-onset and onset/postonset groups, children with Tanner Stage 1 were considered preonset and all others were considered onset/postonset. Children in the SKOT study (aged 3 y) were all considered preonset. Children 8–11 y of age in the ALSPAC were excluded from analyses using puberty stratification owing to insufficient information on puberty. These assessments have been previously described in detail for each study population (18, 27–31).

Genotyping, imputation, and GRS construction

Children in the YFS, TDCOB, and SKOT were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium HumanCoreExome BeadChip (Illumina) (32). Children in the STRIP were genotyped using the Illumina Cardio-MetaboChip (33). Children in the PANIC study were genotyped using the Illumina HumanCoreExome Beadchip and the Illumina Cardio-MetaboChip, and the genotypes from the 2 arrays were combined. Children in the ALSPAC were genotyped using the Illumina HumanHap550 Quad chip. In all studies, genotype imputation was performed using the 1000 Genomes reference panel (34).

To construct the WHRadjBMI GRS, we used 49 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) known to associate with WHRadjBMI in the largest available genome-wide association study (GWAS) published at the time of the present analyses, including ≤224,459 adults from the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits consortium (7) (Supplemental Table 1). One of the SNPs, rs7759742, was not available in all 6 studies of the present meta-analysis and was therefore excluded from the final GRS. The established WHRadjBMI variants were extracted either as alleles from the genotyped data sets or as dosages from the imputed data sets of each cohort. The GRS was then calculated as the sum of the number of WHRadjBMI-increasing alleles or dosages: WHRadjBMI GRS = SNP1 + SNP2 + SNP3 + … SNPn; where SNP is the number of alleles or dosage of the WHRadjBMI-raising allele (i.e., ranging from 0 to 2 WHRadjBMI-raising alleles per locus).

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses and construction of the GRS were performed using R software version 3.3.1 (R core team). Linear regression models for inverse normally transformed residuals, adjusted for age, sex, puberty (YFS, TDCOB, STRIP, PANIC), and study group, if needed (SKOT, STRIP), and the first 3 genome-wide principal components were used to examine the associations of WHRadjBMI GRS with cardiometabolic risk factors. For WHR, we further adjusted the residuals for BMI. For systolic and diastolic blood pressure, we further adjusted the residuals for height. Variables were rank inverse normally transformed to approximate normal distribution with a mean of 0 and an SD of 1. Thus, the effect sizes are reported in SD units of the inverse normally transformed traits. We also studied the associations of WHRadjBMI GRS with cardiometabolic risk factors stratified by puberty (preonset compared with onset/postonset). The results from the different studies were pooled by fixed-effect meta-analyses using the “meta” package of the R software, version 4.6.0 (35). Independent-samples t test was used to compare differences in the effects of the GRS for cardiometabolic risk factors between groups. The associations of the WHRadjBMI GRS with potential confounding lifestyle factors were examined by linear regression adjusted for age and sex in ALSPAC. We estimated the causal effects of WHRadjBMI on cardiometabolic risk factors using 2-staged least-squares regression analyses, implemented in the “AER” R-package (version 1.2-6), including all studies from which information on WHR was available (ALSPAC, TDCOB, STRIP, and PANIC). We tested for differences between the estimates from linear regression and instrumental variable analyses using the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test and assessed the strength of the genetic instrument by calculating the F statistic (36). We tested for potential directional pleiotropy in the genetic instrument using the intercept from Egger regression implemented in the “MendelianRandomization” R-package (version 0.3.0). Hereby, deviation of the Egger intercept from zero provides evidence for pleiotropy (37). Using the same package, we performed additional sensitivity analyses to confirm that the direction of effect that we observed in least-squares regression analysis was consistent with effect estimates based on multiple genetic variants derived from Egger regression and weighted median methods.

Results

Characteristics

Of the 9895 children and adolescents, 50% were girls and 22% exhibited overweight or obesity (Table 1). The mean age was 10.0 y (range: 2.7–18.0 y). Altogether, 54% of the children and adolescents were defined as prepubertal after excluding participants of the ALSPAC study owing to lack of information on their pubertal status.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of children and adolescents in the studies included in the present meta-analyses1

| ALSPAC | YFS | TDCOB cases | TDCOB controls | STRIP | PANIC | SKOT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (total) | 5474 | 2099 | 705 | 361 | 470 | 460 | 326 |

| Girls, n (%) | 2754 (50) | 1139 (54) | 415 (59) | 238 (66) | 227 (48) | 219 (48) | 154 (47) |

| Prepubertal,2n (%) | NA | 1244 (51) | 314 (45) | 73 (22) | 0 (0) | 448 (97) | 326 (100) |

| Overweight/obese,3n (%) | 1088 (20) | 161 (8) | 699 (99) | 46 (13) | 54 (12) | 56 (12) | 34 (10) |

| Age, y | 9.9 ± 0.32 | 9.8 ± 4.0 | 11.5 ± 2.9 | 13.0 ± 3.1 | 15.0 ± 0.0 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| Body height, cm | 139.6 ± 6.3 | 137 ± 25 | 152 ± 16 | 157 ± 16 | 170 ± 8 | 129 ± 6 | 96.2 ± 3.6 |

| Body weight, kg | 34.7 ± 7.3 | 35.1 ± 16.5 | 64.9 ± 23.9 | 48.4 ± 15.3 | 61.3 ± 6.9 | 26.7 ± 4.8 | 14.9 ± 1.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.7 ± 2.8 | 17.4 ± 2.8 | 27.0 ± 5.3 | 19.1 ± 3.2 | 20.5 ± 3.3 | 16.1 ± 2.0 | 16.1 ± 1.2 |

| BMI-SDS | 0.29 ± 1.11 | −0.29 ± 1.00 | 2.90 ± 0.66 | 0.31 ± 1.05 | −0.08 ± 0.97 | −0.20 ± 1.1 | 0.43 ± 0.92 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 62.9 ± 7.7 | NA | 93 ± 15 | 70 ± 9 | 73 ± 8 | 57 ± 5 | 47 ± 4 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.85 ± 0.0 | NA | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.1 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.0 | NA |

| Total body lean mass, kg | 24.6 ± 3.2 | NA | NA | NA | 45 ± 9 | 21 ± 2 | NA |

| Total body fat mass, kg | 8.5 ± 5.0 | NA | 28.0 ± 12.2 | NA | 12.7 ± 7.5 | 5.6 ± 3.3 | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| Body fat percentage, % | 23.2 ± 9.0 | NA | 43.6 ± 5.2 | NA | 20.9 ± 9.3 | 20 ± 8 | 17.4 ± 4.3 |

| Insulin, mU/L | NA | 9.2 ± 5.8 | 6.9 ± 7.2 | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 3.2 ± 3.5 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | NA | NA | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.6 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.65 ± 0.29 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.85 ± 0.42 | 0.60 ± 0.25 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 103 ± 9 | 111 ± 12 | 114 ± 12 | 114 ± 10 | 117 ± 12 | 100 ± 7 | 96 ± 8 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 57 ± 6 | 68 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | 62 ± 7 | 61 ± 9 | 61 ± 7 | 61 ± 7 |

| GRSWHRadjBMI, 48 SNPs (number of WHRadjBMI-increasing risk alleles) | 46.1 ± 4.3 | 47.8 ± 4.4 | 46.4 ± 4.3 | 46.2 ± 4.3 | 46.6 ± 4.8 | 48.2 ± 4.2 | 46.5 ± 4.4 |

1Values are means ± SDs or n (%). ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; BMI-SDS, BMI SD score; GRS, genetic risk score; NA, not available; PANIC, Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children; SKOT, Småbørns Kost Og Trivsel; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; STRIP, Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project; TDCOB, The Danish Childhood Obesity Biobank; WHRadjBMI, waist-to-hip ratio–adjusted BMI; YFS, Cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study.

2Children with Tanner Stage 1 were considered preonset and all others were considered onset/postonset (25, 26).

3Overweight and obesity were defined using the age- and sex-specific BMI cutoffs of the International Obesity Task Force (24).

Association of the WHRadjBMI GRS with cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents

A key assumption of the Mendelian randomization approach is that genetic variants used as an instrument are associated with the exposure variable. In a meta-analysis of all 9895 children and adolescents from the 6 studies, we found that the WHRadjBMI GRS, calculated as the unweighted sum of the number of WHRadjBMI-raising alleles (7), was robustly associated with higher WHRadjBMI (β = 0.021 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.016, 0.026 SD/allele; P = 3 × 10−15) (Supplemental Table 2).

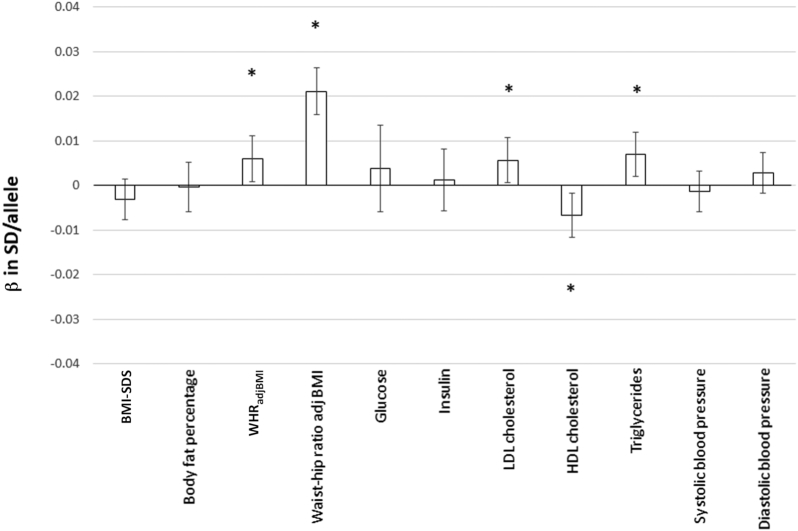

The primary outcome variables of the present analyses were circulating LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides; fasting glucose; fasting insulin; systolic blood pressure; and diastolic blood pressure. We found that the WHRadjBMI-increasing GRS was associated with unfavorable concentrations of blood lipids (higher LDL cholesterol: β = 0.006 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.011 SD/allele; P = 0.025; lower HDL cholesterol: β = −0.007 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.012, −0.002 SD/allele; P = 0.009; higher triglycerides: β = 0.007 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.002, 0.012 SD/allele; P = 0.006). There were no associations between the WHRadjBMI GRS and fasting glucose, fasting insulin, systolic blood pressure, or diastolic blood pressure (P > 0.05) (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Linear regression analysis to test the association of the WHRadjBMI-increasing GRS with cardiometabolic variables in all children and adolescents (n = 9895). The results are expressed as β values (95% CIs) of the inverse normally transformed traits, showing their association with the WHRadjBMI-increasing allele of the GRS. All analyses are adjusted for age, puberty, and the first 3 genome-wide principal components. The effects were pooled using fixed-effects meta-analyses. The numerical values for βs, SEs, P values, and sample sizes are presented in Supplemental Table 2. *P values < 0.05. BMI-SDS, BMI SD score; GRS, genetic risk score; WHRadjBMI, waist-to-hip ratio–adjusted BMI; β in SD/allele, effect on the inverse normally transformed trait per allele increase.

In the original GWAS for WHRadjBMI in adults, 20 of the 49 WHRadjBMI loci showed sexual dimorphism, 19 of which displayed a stronger effect in women (7). In sex-stratified analyses, we found that the WHRadjBMI GRS had a comparable effect on WHRadjBMI in boys and girls but the effect on waist circumference was found only in girls (β = 0.013 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.020 SD/allele; P = 0.001) and not in boys (β = −0.002 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.009, 0.005 SD/allele; P = 0.599) (P for difference = 0.006). The WHRadjBMI GRS was also associated with decreased BMI-SDS in boys (β = −0.008 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.015, −0.002 SD/allele; P = 0.016) but had no effect on BMI-SDS in girls (β = 0.002 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.004, 0.009 SD/allele; P = 0.450) (P for difference = 0.022). Finally, we also found a difference between sexes (P for difference = 3 × 10−4) in the effect of the WHRadjBMI GRS on diastolic blood pressure; the WHRadjBMI GRS had a blood pressure–increasing effect in girls (β = 0.0109 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.017 SD/allele; P = 0.001) but not in boys (β = −0.006 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.013, 0.001 SD/allele; P = 0.072). No differences were found in other cardiometabolic risk factors between girls and boys (P > 0.05).

A previous Mendelian randomization study in adults (5) found a significant inverse association between the WHRadjBMI GRS and BMI and thus performed sensitivity analyses using a WHRadjBMI GRS where all variants associated with BMI (P < 0.05) were excluded. We only found a significant inverse association between the WHRadjBMI GRS and BMI in boys, and thus performed boys-specific sensitivity analyses using a GRS constructed of only those 19 WHRadjBMI SNPs that have not been associated with BMI in the largest GWAS thus far published in adults (P > 0.05) (38). Comparing the results between the 19-SNP GRS and the full 48-SNP GRS in boys (Supplemental Table 3), we found very similar effect sizes in the associations of the 2 scores with cardiometabolic risk traits, except for the expected differences in BMI and related adiposity measures. The results were similar when comparing effect sizes between the 19-SNP GRS and the 48-SNP GRS in all children (Supplemental Table 4).

Puberty has a major effect on body fat distribution (39). We performed additional analyses stratified by puberty status to test whether the relation between WHRadjBMI GRS and cardiometabolic risk factors is established before puberty, but no differences were found (P > 0.05).

A previous study in the TDCOB cohort suggested that there may be differences in genetic influences on body fat distribution between children who are overweight/obese and those who are normal weight (40). We performed analyses stratified by weight status to test whether the effect of the WHRadjBMI GRS on body fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk is modified by overweight/obesity. The WHRadjBMI GRS was associated with fasting insulin in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity (β = 0.016 SD/allele; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.032 SD/allele; P = 0.037) but not in those with normal weight (β = −0.002 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.010, 0.006 SD/allele; P = 0.564) (P for difference = 0.034). Furthermore, the WHRadjBMI GRS was also associated with HDL cholesterol in children with overweight and obesity (β = −0.018 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.030, −0.006 SD/allele; P = 0.036) but not in children with normal body weight (β = −0.004 SD/allele; 95% CI: −0.010, 0.001 SD/allele; P = 0.121) (P for difference = 0.036). No differences were found in other cardiometabolic risk factors between children with overweight/obesity and those with normal body weight (P > 0.05).

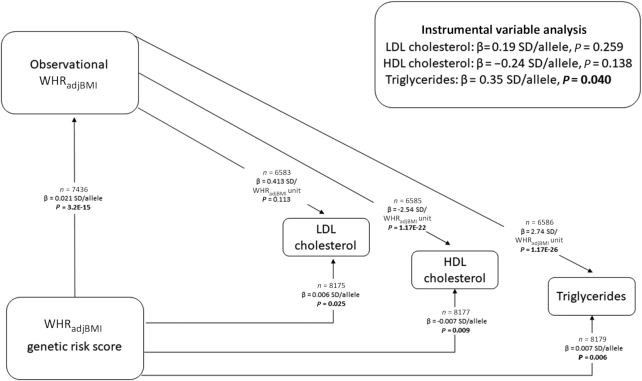

Instrumental variable analyses

We estimated the causal effects of WHRadjBMI on the 3 traits that the WHRadjBMI GRS was significantly associated with (triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol) (Supplemental Table 2) using 2-staged least-squares regression analyses. The observational associations of WHRadjBMI with cardiometabolic risk factors are shown in Supplemental Table 5. In 2-stage least-squares regression analysis, each genetically instrumented 1-SD increase in WHRadjBMI increased circulating triglycerides by 0.17 mmol/L (0.35 SD per allele, P = 0.040) (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 3), indicating a causal relation. No difference was found between the observational results and genetically instrumented results in the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test (PALSPAC > 0.05). There was no evidence of pleiotropy in the genetic instrument using the Egger intercept test (estimate = −0.001; 95% CI: −0.011, 0.009; Pintercept for triglycerides = 0.841). The estimates from Egger regression and weighted median regression were directionally consistent with those derived from the 2-stage least-squares method. The 2-stage least-squares regression analyses did not suggest that a genetically instrumented increase in WHRadjBMI has a causal effect on HDL cholesterol (−0. 24 SD/allele, P = 0.138) or LDL cholesterol (0.19 SD/allele, P = 0.259) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mendelian randomization analysis to test the causal effect of childhood abdominal adiposity on LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. The figure shows associations of the WHRadjBMI genetic risk score with LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and observational WHRadjBMI, as well as the associations of the observational WHRadjBMI with LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. The results of the instrumental variable analysis are obtained from 2-staged least-squares regression analyses. β values are expressed as units of SD of the inverse normally transformed traits. P values < 0.05 are shown in bold. WHRadjBMI, waist-to-hip ratio–adjusted BMI; β in SD/allele, effect on the inverse normally transformed trait per allele increase.

To conduct a valid Mendelian randomization analysis, the instrumental variable must not be associated with possible confounders that could bias the relation between the exposure and the outcome, and it must relate to the outcome phenotype only through its association with the exposure and not through pleiotropy (6). Some lifestyle and environmental factors, for example physical activity and dietary habits, have been associated with body fat distribution (4) and cardiometabolic risk, and could therefore confound the association between WHRadjBMI and cardiometabolic risk factors. However, we did not find an association between the WHRadjBMI GRS and any of the potential confounders we tested in the ALSPAC cohort, including objectively measured physical activity (P = 0.508), sedentary time (P = 0.580), family socioeconomic status (P = 0.676), total energy intake (P = 0.744), and dietary intakes (in energy percentage) of protein (P = 0.661), total fat (P = 0.193), saturated fat (P = 0.413), monounsaturated fat (P = 0.168), polyunsaturated fat (P = 0.306), carbohydrates (P = 0.467), and added sugar (P = 0.201). We acknowledge that unobserved confounders could still be present that we were not able to control for.

Discussion

In the present study, genetic predisposition to higher WHRadjBMI was associated with higher triglycerides, lower HDL cholesterol, and higher LDL cholesterol in children and adolescents. The associations of the WHRadjBMI GRS with lipids were similar between prepubertal and pubertal/postpubertal children and adolescents, indicating that this relation is established already before puberty. Instrumental variable analyses indicated that higher WHRadjBMI may be causally associated with higher triglycerides.

Sex and age have major effects on WHRadjBMI (39). Sexual dimorphism in body composition emerges primarily during pubertal development and is driven by the action of sex steroids (41). Women typically have overall higher body fat content, whereas men have a more central body fat distribution. The WHRadjBMI GRS, constructed from the 49 loci, also shows a stronger effect on WHRadjBMI in women than in men (7). In contrast to adults, we observed that the WHRadjBMI GRS had a comparable effect on WHRadjBMI in children regardless of sex. However, the effect on waist circumference was higher in girls than in boys. Previous studies have shown that sexual dimorphism in body fat distribution is already distinct by 6 y of age, characterized by an average smaller waist and larger hip circumference in girls (42). However, unlike in adulthood, the difference at this age is more pronounced for waist circumference than for hip circumference (42), which could partly explain why the genetic influences on waist circumference seem more pronounced in girls than in boys during childhood but not in adulthood.

The effects of the WHRadjBMI GRS on fasting insulin and HDL cholesterol were more pronounced among children and adolescents with overweight/obesity than among those with normal body weight, indicating that higher overall adiposity may enhance the harmful effect of genetic predisposition to abdominal adiposity on insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Although the biological mechanisms for this enhancement are uncertain, we speculate that higher overall adiposity may lead to a suppressed capacity of subcutaneous fat tissue to store additional fat and a higher deposition of fat in visceral and other ectopic storage sites. The metabolically active visceral fat releases a number of inflammatory cytokines as well as a flux of free fatty acids into the portal circulation. This may, in turn, impair hepatic metabolism, thereby leading to reduced hepatic insulin clearance, increased production of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, and increased hepatic glucose production (43, 44). Thus, increased visceral fat has a central role in the development of insulin resistance. Higher overall adiposity also results in greater storage of abdominal subcutaneous fat which has a high lipolytic activity and increases the flux of free fatty acids, contributing to insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease risk (45). This impact may be particularly relevant in children who have a relatively large volume of abdominal subcutaneous fat compared with visceral fat (12, 13).

Previous studies in adults support the role for gradually increasing visceral fat as a determinant of unfavorable changes in plasma lipid concentrations with advancing age (46). Although the effect sizes of the GRS for WHRadjBMI on WHRadjBMI and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents in the present study were generally weaker than in adults (7), it remains unclear how age plays into the observed causal relations because partly different variants may associate with WHRadjBMI at different ages.

The strength of the present study is the comprehensive data on anthropometry, cardiometabolic risk factors, and genetic variation from several European child cohorts. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the causal associations of abdominal adiposity with cardiometabolic risk factors by Mendelian randomization in children. Limitations of the study are the use of adult GWAS-based variants for WHRadjBMI, which may not all be associated with abdominal adiposity in children. Furthermore, we did not address the possibility of bidirectional relations between WHRadjBMI and cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Despite the large sample size, our study may have been underpowered to detect a difference for the studied outcome traits. In the present analysis, we did not correct for multiple testing owing to many of the outcome traits being correlated, and we acknowledge that adjustment of the significance threshold could reduce the statistical power further. Finally, because our study only included children of European genetic ancestry, the results cannot be generalized to other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, our results suggest that there may be a causal, unfavorable effect of abdominal adiposity on plasma triglycerides in childhood, providing new insights into the relation between body fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk in young age. The results underscore the importance of early weight management through healthy dietary habits and physically active lifestyle among children with a tendency for abdominal fat accumulation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in ALSPAC (University of Bristol), the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. We also especially express our thanks to the participating children and adolescents as well as their parents that were part of the YFS (Universities of Helsinki, Turku, Tampere, Kuopio and Oulu), TDCOB (Copenhagen Univesity Hospital Holbaek), STRIP (University of Turku), PANIC (University of Eastern Finland), and SKOT (Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre) studies. We are also grateful to all members of these research teams for their skillful contribution in performing the studies.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—AV and TMS: researched the data; AV: wrote the paper and had primary responsibility for the final content; TOK: designed the research; NP, MH, TRHN, KP, MA, MVL, SH, C F-B, CEF, NG, MK, GDC, AL, OP, KFM, TAL, JCH, TL, OR, and TH: conducted the research and/or provided essential materials; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Notes

Supported by the European Union (EU)’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 796143 (to AV), the Orion Research Foundation (to AV), the Emil Aaltonen Foundation (to AV), Danish Council for Independent Research grant DFF—6110-00183, and Novo Nordisk Foundation grants NNF17OC0026848 (to TOK) and NNF18CC0034900. UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust grant 102215/2/13/2 and the University of Bristol provide core support for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). ALSPAC genome-wide association study data were generated by Sample Logistics and Genotyping Facilities at Wellcome Sanger Institute and LabCorp (Laboratory Corporation of America) using support from 23andMe. A comprehensive list of grant funding (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf) is available on the ALSPAC website. This research was specifically funded by Wellcome Trust grant 086676/Z/08/Z. The Cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study was supported by Academy of Finland grants 286284, 134309 (Eye), 126925, 121584, 124282, 129378 (Salve), 117787 (Gendi), and 41071 (Skidi); the Social Insurance Institution of Finland; Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Kuopio, Tampere, and Turku University Hospitals grant X51001; the Juho Vainio Foundation; Paavo Nurmi Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Finnish Cultural Foundation; The Sigrid Juselius Foundation; Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation; Emil Aaltonen Foundation; Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Diabetes Research Foundation of the Finnish Diabetes Association; EU Horizon 2020 grant 755320 (for TAXINOMISIS); European Research Council grant 742927 (for the MULTIEPIGEN project); and the Tampere University Hospital Supporting Foundation. The Danish Childhood Obesity Biobank study is part of the research activities in TARGET (The Impact of our Genomes on Individual Treatment Response in Obese Children) and BIOCHILD (Genetics and Systems Biology of Childhood Obesity in India and Denmark). The study is part of The Danish Childhood Obesity Biobank (NCT00928473). The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent Research Center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (www.cbmr.ku.dk). The study was supported by Danish Innovation Foundation grants 0603-00484B and 0603-00457B, Novo Nordisk Foundation grant NNF15OC0016544, and the Region Zealand Health and Medical Research Foundation. The Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project was supported by Academy of Finland grants 206374, 294834, 251360, and 275595; the Juho Vainio Foundation; Finnish Cultural Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Sigrid Jusélius Foundation; Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation; Novo Nordisk Foundation; Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture; Special Governmental Grants for Health Sciences Research, Turku University Hospital; and the University of Turku Foundation. The Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland, Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Finnish Cultural Foundation, Juho Vainio Foundation, Foundation for Paediatric Research, Paavo Nurmi Foundation, Paulo Foundation, Diabetes Research Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, Research Committee of the Kuopio University Hospital Catchment Area (State Research Funding), Kuopio University Hospital (EVO funding number 5031343), and the city of Kuopio. The Småbørns Kost Og Trivsel (SKOT)-I study was supported by grants from The Danish Directorate for Food, Fisheries, and Agri Business as part of the “Complementary and young child feeding (CYCF)—impact on short- and long-term development and health” project. The SKOT-II study was supported by grants from the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation and contributions from the research program “Governing Obesity” by the University of Copenhagen Excellence Program for Interdisciplinary Research (www.go.ku.dk).

Supplemental Figures 1–3, Supplemental Methods, and Supplemental Tables 1–5 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

AV and TMS contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used: ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; BMI-SDS, BMI SD score; GRS, genetic risk score; GWAS, genome-wide association study; PANIC, Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children; SKOT, Småbørns Kost Og Trivsel; STRIP, Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project; TDCOB, The Danish Childhood Obesity Biobank; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; WHRadjBMI, waist-to-hip ratio–adjusted BMI; YFS, Cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study.

References

- 1. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bastien M, Poirier P, Lemieux I, Despres JP. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity to cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56:369–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, Srinivasan SR, Daniels SR, Davis PH, Chen W et al.. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tchernof A, Després JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:359–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emdin CA, Khera AV, Natarajan P, Klarin D, Zekavat SM, Hsiao AJ, Kathiresan S. Genetic association of waist-to-hip ratio with cardiometabolic traits, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2017;317:626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:R89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, Ferreira T, Locke AE, Magi R, Strawbridge RJ, Pers TH, Fischer K, Justice AE et al.. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santos S, Severo M, Lopes C, Oliveira A. Anthropometric indices based on waist circumference as measures of adiposity in children. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26:810–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monnereau C, Santos S, van der Lugt A, Jaddoe VWV, Felix JF. Associations of adult genetic risk scores for adiposity with childhood abdominal, liver and pericardial fat assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(4):897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garnett SP, Baur LA, Srinivasan S, Lee JW, Cowell CT. Body mass index and waist circumference in midchildhood and adverse cardiovascular disease risk clustering in adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawlor DA, Benfield L, Logue J, Tilling K, Howe LD, Fraser A, Cherry L, Watt P, Ness AR, Davey Smith G et al.. Association between general and central adiposity in childhood, and change in these, with cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spolidoro JV, Pitrez Filho ML, Vargas LT, Santana JC, Pitrez E, Hauschild JA, Bruscato NM, Moriguchi EH, Medeiros AK, Piva JP. Waist circumference in children and adolescents correlate with metabolic syndrome and fat deposits in young adults. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ali O, Cerjak D, Kent JW, James R, Blangero J, Zhang Y. Obesity, central adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents: a family-based study. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:e58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, Henderson J, Macleod J, Molloy L, Ness A et al.. Cohort profile: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:97–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Davey Smith G. Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:111–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Åkerblom HK, Uhari M, Pesonen E, Dahl M, Kaprio EA, Nuutinen EM, Pietikäinen M, Salo MK, Aromaa A, Kannas L. Cardiovascular risk in young Finns. Ann Med. 1991;23:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holm JC, Gamborg M, Bille DS, Grønbæk HN, Ward LC, Faerk J. Chronic care treatment of obese children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simell O, Niinikoski H, Rönnemaa T, Raitakari OT, Lagström H, Laurinen M, Aromaa M, Hakala P, Jula A, Jokinen E et al.. Cohort profile: the STRIP study (Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project), an infancy-onset dietary and life-style intervention trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:650–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eloranta AM, Lindi V, Schwab U, Kiiskinen S, Kalinkin M, Lakka HM, Lakka TA. Dietary factors and their associations with socioeconomic background in Finnish girls and boys 6–8 years of age: the PANIC Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:1211–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andersen LB, Pipper CB, Trolle E, Bro R, Larnkjaer A, Carlsen EM, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF. Maternal obesity and offspring dietary patterns at 9 months of age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73:25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. New Finnish growth references for children and adolescents aged 0 to 20 years: length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index-for-age. Ann Med. 2011;43:235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nysom K, Mølgaard C, Hutchings B, Michaelsen KF. Body mass index of 0 to 45-y-old Danes: reference values and comparison with published European reference values. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Falaschetti E, Hingorani AD, Jones A, Charakida M, Finer N, Whincup P, Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Sattar N, Deanfield JE. Adiposity and cardiovascular risk factors in a large contemporary population of pre-pubertal children. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:3063–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Rönnemaa T, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Räsänen L, Pietikäinen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, Taittonen L, Jokinen E, Marniemi J et al.. Cohort profile: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fonvig CE, Chabanova E, Ohrt JD, Nielsen LA, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Thomsen HS, Holm JC. Multidisciplinary care of obese children and adolescents for one year reduces ectopic fat content in liver and skeletal muscle. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Viitasalo A, Laaksonen DE, Lindi V, Eloranta AM, Jääskeläinen J, Tompuri T, Väisänen S, Lakka HM, Lakka TA. Clustering of metabolic risk factors is associated with high-normal levels of liver enzymes among 6- to 8-year-old children: the PANIC study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10(5):337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Madsen AL, Schack-Nielsen L, Larnkjaer A, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF. Determinants of blood glucose and insulin in healthy 9-month-old term Danish infants; the SKOT cohort. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teo YY, Inouye M, Small KS, Gwilliam R, Deloukas P, Kwiatkowski DP, Clark TG. A genotype calling algorithm for the Illumina BeadArray platform. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2741–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Voight BF, Kang HM, Ding J, Palmer CD, Sidore C, Chines PS, Burtt NP, Fuchsberger C, Li Y, Erdmann J et al.. The metabochip, a custom genotyping array for genetic studies of metabolic, cardiovascular, and anthropometric traits. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA, 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casale FP, Rakitsch B, Lippert C, Stegle O. Efficient set tests for the genetic analysis of correlated traits. Nat Methods. 2015;12:755–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pierce BL, Ahsan H, Vanderweele TJ. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:740–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pulit SL, Stoneman C, Morris AP, Wood AR, Glastonbury CA, Tyrrell J, Yengo L, Ferreira T, Marouli E, Ji Y et al.. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for body fat distribution in 694 649 individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wells JC. Sexual dimorphism of body composition. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:415–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Graae AS, Hollensted M, Kloppenborg JT, Mahendran Y, Schnurr TM, Appel EVR, Rask J, Nielsen TRH, Johansen MØ, Linneberg A et al.. An adult-based insulin resistance genetic risk score associates with insulin resistance, metabolic traits and altered fat distribution in Danish children and adolescents who are overweight or obese. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stevens J, Katz EG, Huxley RR. Associations between gender, age and waist circumference. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Fekkes M, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Wit JM. Are age references for waist circumference, hip circumference and waist-hip ratio in Dutch children useful in clinical practice?. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blüher S, Schwarz P. Metabolically healthy obesity from childhood to adulthood — does weight status alone matter?. Metabolism. 2014;63:1084–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Björntorp P. “Portal” adipose tissue as a generator of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel P, Abate N. Role of subcutaneous adipose tissue in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. J Obes. 2013;2013:489187. doi: 10.1155/2013/489187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DeNino WF, Tchernof A, Dionne IJ, Toth MJ, Ades PA, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Contribution of abdominal adiposity to age-related differences in insulin sensitivity and plasma lipids in healthy nonobese women. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:925–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.