Abstract

Standardized patients (SPs), i.e. mystery shoppers for healthcare providers, are increasingly used as a tool to measure quality of clinical care, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where medical record abstraction is unlikely to be feasible. The SP method allows care to be observed without the provider’s knowledge, removing concerns about the Hawthorne effect, and means that providers can be directly compared against each other. However, their undercover nature means that there are methodological and ethical challenges beyond those found in normal fieldwork. We draw on a systematic review and our own experience of implementing such studies to discuss six key steps in designing and executing SP studies in healthcare facilities, which are more complex than those in retail settings. Researchers must carefully choose the symptoms or conditions the SPs will present in order to minimize potential harm to fieldworkers, reduce the risk of detection and ensure that there is a meaningful measure of clinical care. They must carefully define the types of outcomes to be documented, develop the study scripts and questionnaires, and adopt an appropriate sampling strategy. Particular attention is required to ethical considerations and to assessing detection by providers. Such studies require thorough planning, piloting and training, and a dedicated and engaged field team. With sufficient effort, SP studies can provide uniquely rich data, giving insights into how care is provided which is of great value to both researchers and policymakers.

Keywords: Standardized patients, quality of care

Key Messages

Standardized patients are a uniquely valuable tool for measuring quality of care.

Multiple recent studies have successfully addressed scientific, ethical and practical challenges when implementing large-N standardized patient studies in health facilities.

Future studies can not only build on the increasing expertise and experience of others but also innovate and develop the tool.

Introduction

Clinical quality of care, the process through which inputs from the health system are transformed into health outcomes (Donabedian, 1988), is arguably the most informative dimension of quality, as it is the key point where provider behaviour influences case management. However, it is also highly challenging to measure (Hanefeld et al., 2017), and many commonly used methods for measuring clinical quality have significant disadvantages. Direct observation cannot control the types of patients and cases observed (Peabody et al., 2000), clinical vignettes measure knowledge rather than practice (Leonard et al., 2007; Mohanan et al., 2015), and both suffer from Hawthorne effects (Leonard and Masatu, 2010). Medical record abstraction is usually unfeasible in LMICs especially in the private sector where record-keeping is often poor or non-existent (Aung et al., 2012). Patient exit interviews suffer from recall bias and poor response rates, and may require the patient to understand clinical procedures (Onishi et al., 2010).

A key advance in the measurement of clinical quality is the use of standardized patients (SPs) in primary care settings. Healthy people, employed by a research study, pose as real patients, responding to the clinician’s actions as a real patient would. Alternative terms include mystery client, simulated patient, covert patient and undercover careseeker. SPs have a long history in medical education (Peabody et al., 2000), where the clinician knows that she is being tested outside a real-world milieu. The method is increasingly being used as a research tool in large field studies to assess deficits in care (Das et al., 2012; Kohler et al., 2017; Christian et al., 2018), evaluate quality improvement strategies (Harrison et al., 2000; Mathews et al., 2009; Das et al., 2016a), and identify how financial incentives influence quality (Currie et al., 2014; Das et al., 2016b).

The SP method has a number of advantages. In a high-quality SP study, clinicians believe they are treating a real patient and, therefore, measures are not influenced by the Hawthorne effect (Leonard and Masatu, 2010). Because each case is completely standardized, care can be benchmarked against pre-determined standards for a specific condition. We can say that an antibiotic was incorrectly used because we know the SP presented with symptoms of a viral pharyngitis rather than pneumonia. The ability to control patient-mix avoids confounding and allows for the investigation of rarer conditions, such as tuberculosis (TB), which might otherwise require long observation periods to gather a sufficient sample (Peabody et al., 2000). Where the objective is to compare across different types of patients, the SP presentation can be altered (or different types of SPs such as men and women can present the same condition) to assess how provider behaviour responds to patient characteristics (Currie et al., 2011; Planas et al., 2015). Finally, in evaluations of interventions, SPs provide scope for double-blinding, whereby providers cannot tell which patients are SPs, and the SPs themselves are blinded to the treatment arm of providers they visit (Das et al., 2016a).

The main downsides are that the disease cases suitable for SPs are limited, thereby restricting their applicability, and developing SPs for use in the field is complex, which may limit their scalability. There is ongoing debate on the ethics of SP research, though the ‘deception’ of clinicians can be ethically justified where (1) other options cannot answer the research questions (Alderman et al., 2014); (2) risks to SPs and providers are minimal; and (3) the knowledge generated is of value to society (Rhodes and Miller, 2012).

In this article, we provide a step-by-step guide on using SPs to measure the quality of care in health facilities (dispensaries, health centres or clinics). The guide is based on a review of SP studies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (full details in Supplementary Appendix), as well as our experiences implementing this approach in public and private health facilities in China, India, Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania. The SP method is also frequently used in the retail sector, e.g. in pharmacies or informal drug sellers (Fitzpatrick and Tumlinson, 2017), but our focus on health facilities reflects the particular challenges faced in documenting clinician–patient interactions and handling requests for exams and diagnostic tests.

Step 1: choosing a suitable SP case

The first choice made when designing an SP study is case selection, i.e. the condition or symptoms SPs present to providers. The major considerations are whether the case is technically feasible, whether it is ethically acceptable to ask SPs to present the case, and whether the case will be suitable both to the local context and the purpose of the study. We list 10 questions which researchers should ask when assessing cases for inclusion in Table 1. Some cases will never be feasible and are likely to be excluded by all studies, e.g. any case requiring inpatient care would be deemed too high a risk to a fieldworker, and an SP with a wound would be practically impossible to falsify. Perceptions of feasibility may change over time; e.g. TB was once perceived as a condition which could not be measured using the SP method, but has now been validated as an assessment of quality (Das et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Ten questions to consider when assessing suitability as an SP case

| Key question | Explanation and examples |

|---|---|

| Technical feasibility | |

| Can a trained SP portray the case? | Conditions which have visible symptoms are unlikely to be suitable SP cases, as are conditions where patients would be expected to be acutely unwell. For example, an asthma SP could describe a previous attack but would not be expected to mimic one during the visit. |

| Do national or international guidelines exist for correct management or treatment? | If the aim is to assess quality of care against specific standards there will be a need for agreed-upon guidelines to provide a clear definition of the correct treatment outcome. |

| Can expected management be performed within one visit? | There is unlikely to be scope within the study design for the SP to return to the facility for follow-up visits. |

| Ethical acceptability | |

| Does the case choice minimize potential harm to fieldworkers? | Conditions should be chosen to avoid the need for invasive tests. Although cases requiring fingerprick blood tests have been used (Mathews et al., 2009), it would be inappropriate to use a suspected sexually transmitted infection (STI) case which is likely to require a genital exam, or suspected typhoid which may require a venous blood draw for a Widal test. It should be noted that unexpected invasive tests may be requested: in one study in Senegal, almost all SPs requesting family planning were told they needed a vaginal exam. Researchers should consider whether the SP can avoid such unexpected tests or exams without raising undue suspicion. |

| Does the case require the involvement of children? | Some studies may choose not to use child SPs due to concerns over potential harm to and exploitation of children. |

| Appropriateness to context and research question | |

| Is the case appropriate to the study objective? | For example, in a study to measure the effect of a quality improvement intervention, the treatment of the case chosen should be sensitive to the intervention. In addition, one might select a ‘control’ condition which should not show improvement as a result of the intervention. |

| Do stakeholders agree the case is a ‘fair test’? | Ensuring buy-in from funders, partners, implementers and government before implementation improves confidence in the validity of results and can enhance the study’s potential to inform practice and policy. |

| Is the case applicable to all health facilities and regions in the study? | Certain small or specialist facilities may offer a limited range of services. Religious faith may preclude some facilities from offering certain care (e.g. Roman Catholic run facilities might not provide family planning services). A word of caution though—we often come across facilities who say they do not provide care for certain categories of patients, but in practice do provide care when visited by the SP. Service availability should, therefore, be investigated empirically by an SP visit or a scoping exercise rather than relying on researcher assumptions or stated practices. |

| Does the case represent a public health concern? | Cases should be a public health concern at the individual or population level. This could reflect high prevalence (e.g. malaria); potentially severe consequences such as a high case fatality rate (e.g. heart attack); or the likelihood of unsafe or inappropriate treatment (e.g. overuse of antibiotics for common cold). |

| Does the case match local epidemiology? | Rare conditions may raise provider suspicion or have very low rates of recognition or correct management. |

It is useful to refer to—and sometimes replicate—SP cases developed by previous studies. We conducted a scoping review of all SP studies in LMIC health facilities up to December 2016, and identified 17 conditions across 63 articles, covering 45 studies (Table 2). One advantage of replicating such cases is the opportunities to share SP scripts and tools and learn from the experience of others. Colleagues can advise on the feasibility of implementing certain SP cases, and how effectively they measured the quality of care. Secondly, if multiple studies share SP cases, direct comparisons are possible across settings. Examples of such comparisons to date include: (1) dispensing practices for suspected TB patients in multiple settings in urban India (Miller et al., 2018) and (2) treatment of asthma, chest pain, diarrhoea and TB across China, India and Kenya (Daniels et al., 2017; Das et al., 2018). However, as Table 2 shows, the range of SP cases used is currently limited. This may reflect not only the need and scope for the development of more cases but also the challenges of identifying cases meeting the requirements discussed in Table 1.

Table 2.

Conditions used in SP studies in health facilities in LMICs

| Category | Condition | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual and reproductive health | Family planning client | 20 |

| STI symptoms | 7 | |

| HIV testing | 2 | |

| Suspected pregnancy, seeking abortion | 1 | |

| STI screening after partner notification | 1 | |

| Other infectious diseases | Common cold, respiratory tract infection or influenza-like illness | 5 |

| Malaria | 3 | |

| Tuberculosis | 1 | |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | |

| NCDs | Angina | 3 |

| Asthma | 2 | |

| Back pain | 1 | |

| Psychological | Anxiety | 2 |

| Depression | 1 | |

| Childhood infectious diseases | Diarrhoea (child absent) | 4 |

| Pneumonia (child absent) | 1 | |

| Diarrhoea (child present) | 1 |

Source: Review of SP studies in LMIC health facilities, up to December 2016. For further details see Supplementary Appendix.

If resources allow, choosing more than one case so that each provider receives multiple visits allows more quality dimensions to be assessed and increases statistical power. One might consider using a range of different SP cases, mixing:

Infectious diseases with non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

Uncommon but severe conditions with common, non-critical, but high-burden diseases

Conditions requiring laboratory diagnostics with those requiring only history taking to diagnose

Conditions for which there is typically overprovision with conditions where there is underprovision

Different stages of disease progression or experimental variants, such as some patients already having a laboratory report whereas others do not, for the same disease

Step 2: defining correct management

Once conditions are chosen, an indicator of correct management should be pre-defined for each SP case. Correct management should be based upon national standard treatment guidelines to ensure appropriateness to the study setting, but may need to incorporate international recommendations (such as WHO guidelines) where national guidelines are unavailable. A technical advisory group including clinicians and public health professionals, with knowledge of best practice and experience of local health systems, can also be convened to advise on correct management. Suggested types of outcomes are given in Table 3 covering both actions required, such as the provision of certain drugs or referral, and actions that are not only not required but also may be considered harmful to the patient, or unnecessary care which is not dangerous but nonetheless has an opportunity cost. An alternative to a binary correct management definition is to construct a continuous index by assigning points for different elements of management. However, any such measure will be critically sensitive to the weighting of the different possible correct, incorrect and neutral components of care. Our experience has shown that the types of unnecessary and harmful care provided can be highly unpredictable, so collecting outcomes based solely on a preconceived checklist of what should happen may miss much of the care that is actually provided. Researchers should therefore ensure that data collection tools are sufficiently open and flexible to collect data on all laboratory tests, medicines and recommendations provided.

Table 3.

Outcomes to consider in definition of correct management

| Outcome | Example |

|---|---|

| Prescription or dispensing of appropriate drugs | Salbutamol inhaler for asthma |

| Carrying out or ordering necessary diagnostic tests | mRDT or blood slide for suspected malaria |

| Referral for further testing (to another facility if necessary) | Suspected TB |

| No inappropriate testing | No urinalysis for cases without symptoms of urinary tract infection |

| No harmful treatments | No beta-blockers for asthma |

| No provision of unnecessary drugs | No antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infection |

If the sample includes a wide range of providers or facilities, the definition of correct management may need to accommodate a range of potentially correct outcomes, depending on provider qualifications or facility level. For example, in facilities with on-site TB testing, correct management for suspected TB should be defined as the ordering of appropriate diagnostic tests. In smaller facilities without such capacity, correct management may be defined as referral to a higher-level facility.

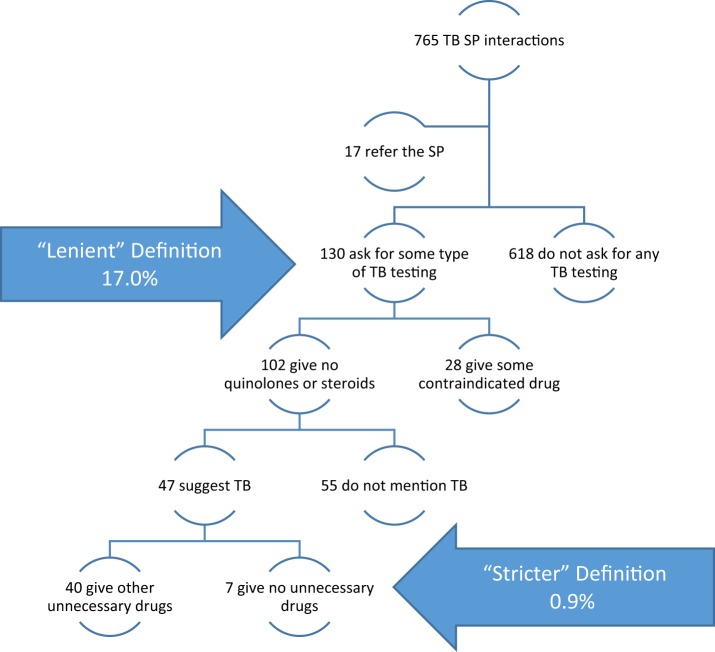

Regardless of the provider type, researchers will need to make judgements on how lenient or strict/comprehensive the definition of correct management should be, and this can have a dramatic impact on results (Sylvia et al., 2017). Box 1 uses data from Kwan et al. (2018) to construct the flowchart of provider actions for 765 SP interactions with providers without a medical degree. If we define correct management as ‘asking for a TB-related test’, 17.0% are classified as correctly managed. But, of these, 21.5% also gave a contraindicated drug, 42.3% did not mention TB to the patient and 30.8% gave unnecessary (but not contraindicated) drugs, including antibiotics. A stringent definition of correct management as ‘asked for a TB-related test without giving contraindicated or unnecessary drugs and discussed the prognosis with the patient’ reduces the fraction correctly managed to 0.9%.

Box 1. Using a lenient versus stricter definition of correct management for TB has a substantial effect on the proportion defined as correctly managed (data from Kwan et al., 2018)

Further, the classification of correct management may be conditional on the results of diagnostic tests. For example, correct management of suspected malaria has two steps, the second of which is conditional on the first: a malaria test must be carried out, then an appropriate antimalarial prescribed if the test is positive, or no antimalarial prescribed if the test is negative. Researchers may also wish to consider the true status of the patient in the definition of correct management. For example, if an SP is known not to have malaria, any antimalarial provision could be considered inappropriate even if the provider reports a positive test, though as such tests are not 100% accurate even under ideal conditions, this may identify both faults with the provider and with the test itself.

This complexity of defining correct management is not a flaw of the SP method per se; instead, it highlights the importance of paying close attention to the definitions selected, and the utility of presenting a range of definitions. Finally, while correct management is typically the primary study outcome, it is relatively easy to also collect other outcomes related to the consultation (e.g. history taking) or the patient experience (e.g. waiting time), which provide important context for understanding correct management outcomes. Some suggestions are given in Box 2.

Box 2. Other possible outcomes

Waiting time and consultation time

History taking

Correct diagnosis

Total fees paid and fees by type (consultation, laboratory tests, drugs)

Subjective outcomes such as provider manner and patient-centeredness

Intervention specific elements (e.g. voucher received)

Step 3: designing tools and planning the study

The SP scripts define each case in detail and are the primary means for standardizing the case to ensure comparability across providers. A script begins with a short opening statement which the SP delivers to each provider describing the symptoms (such as ‘Doctor, I have a cough and some fever’ for suspected TB), which is followed by scripted responses to history questions, which the provider may or may not ask. The SP must not give additional information to the provider outside this script, nor give information from the history question section unprompted. The script should also include a short biography describing the social background, age, occupation, family details and the circumstances of the illness presented.

The corresponding structured questionnaire, which the SP completes after each interaction, captures all information needed to define correct management (physical exams, diagnostic tests, drugs and other treatments), as well as other outcomes of interest and general comments on the visit. It should be completed soon after the visit, either as a self-completed questionnaire by the SP or through an interview of the SP by a supervisor. Developing these tools is an iterative process, and numerous changes will likely be made during piloting and training, with SP trainees themselves playing integral roles throughout this process. Steps to take when developing tools are described in Box 3.

Box 3. Key stages in developing scripts and questionnaires

Preliminary observation in health facilities to inform tool design

How do patients with the condition(s) of interest behave? What vernacular is used to describe symptoms and treatments?

What questions are asked of patients and what information is collected on them?

What is the route of a patient through a health facility (e.g. through reception, triage, consultation, laboratory, etc.)? Where and when do they pay (if applicable)?

Writing SP script

Decide on symptoms, history and biographical details of SP

Begin with an opening statement giving key information, which should be delivered in a natural manner

Specify answers to questions which providers typically ask

Give appropriate amount of information to enable diagnosis, but only in response to appropriate prompting

Check that language used is appropriate for a typical patient (i.e. not overly medicalized)

Developing questionnaire

Draft questionnaire content, ensuring that all required outcomes are covered

Consider using a standardized questionnaire which can be adapted to the case, allowing comparison across cases and studies

-

Decide how the questionnaire will be administered:

- Self-administered questionnaires minimize the time lag between the end of the interaction and debrief, reducing recall bias. Supervisor-administered may allow for probing and checking responses but is more resource-intensive.

- Smartphone or tablet questionnaire removes need for later data entry. In some settings, smartphones can be carried in the facility without attracting attention

Piloting

Start with observed role-plays, where a member of the study team or trusted fieldworker performs the script with a provider outside the study who has agreed to assist

Next, approach other providers outside of the study for consent to do undercover piloting

Record experiences from each visit, including history questions asked and diagnostic tests ordered, amending the script and questionnaire as necessary

Piloting visits can also be used to forecast SP fee costs for the study

Conduct repeated pilots during training

Once the design of cases and tools are underway, the researcher must define a sampling frame and decide on the unit of analysis. Analysis of SP studies can be done at the level of the clinician or the facility. Facility-level analysis is likely to be appropriate when the research questions do not relate to the performance of specific providers, e.g. when evaluating an intervention randomized at the facility level. Provider-level analysis has the advantage of allowing investigators to address additional questions such as the know-do gap of individual providers (Mohanan et al., 2015), or the effect of provider cadre or training on quality. However, provider-level data are more challenging to collect because SPs must visit specific clinicians identified a priori, which presents two practical challenges: first, the production of a sampling frame of all eligible providers (facility staff lists may be incomplete and providers may work at multiple facilities) and second, the identification of providers by SPs in contexts where name badges are rare and asking for a name may be considered unusual or rude.

Step 4: addressing ethical concerns

Ethical norms in medical research require informed, freely given consent of participants. However, the SP method, by its very nature, requires that providers do not have full information on when or how data collection occurs (Madden et al., 1997). Furthermore, because providers are likely to have substantial knowledge about the quality of their own practice, selective refusal may hamper a study’s ability to produce representative data on care real patients receive (Rhodes and Miller, 2012).

Several approaches to provider consent have been used (Table 4), though it should be noted that many studies identified in the literature review (21/45) did not report their consent process.

Table 4.

Approaches to provider consent in SP studies

| Approach | Rationale | Resource-intensiveness of consent process | Number of studiesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waiver of consent | Services are freely accessible by the public and collecting data has minimal risk to providers. Obtaining consent would increase risk of detection, thereby reducing quality of data and harming study aims. | Low:

|

4 |

| Consent from over-arching entity | If providers or facilities in the study come under the control of an entity (such as a Ministry of Health, a diocese or a chain), a representative of the organization can consent on their behalf. | Low:

|

0 |

| Consent from facility in-charge prior to SP visit | If the data collection and analysis are carried out at the facility (rather than provider) level, the owner and/or manager of the facility can give consent. | Middle:

|

8 |

| Consent from individual providers prior to SP visit | Providers are the participants whose behaviour is observed in the course of the research, and so consent should be obtained from them. This may be considered particularly important if the data collection and analysis are carried out at the provider level. | High:

|

12 |

Studies in review of SP studies in LMIC health facilities for which the consent process was described.

Where consent is obtained, researchers still need to withhold certain information from participants. The participant should be given a broad window of time during which an SP will visit, not a date or appointment. For example, if SP visits are planned six weeks after consent, the provider can be informed that the visit will occur ‘at some point in the next three months’. If the provider asks for a specific date, they should be told that to give one would compromise the nature of the research. A similar explanation should be given if they ask about the type of patient who will visit, or the condition they suffer from. To avoid providers unintentionally being given such sensitive details, ideally the team members conducting the consent process should be blinded to the SP conditions, or the consent process carried out by a senior researcher who will be able to resist pressure from providers to disclose such details. The consent process may be combined with other, non-SP aspects of a study, such as a survey of the health facility or provider knowledge.

If the waiver of consent approach is chosen, this must be justified to ethics committees, who may not be familiar with the SP method and may be wary of such waivers. Committees may only be prepared to approve such an approach if there are government approvals for the study, and/or a commitment to inform providers that they received an SP by letter or public meeting after data collection is completed. Further risks associated with using a waiver of consent are loss of the trust of a provider if an SP is discovered and risk of aggression towards that SP.

Working as an SP exposes fieldworkers to risks they would not experience during ordinary survey data collection, and it is the responsibility of the study team to minimize and mitigate these risks to the greatest possible extent. This can be achieved through two main pathways. Firstly, the study should be designed to minimize such risks. This must be considered throughout the design process, and has been discussed under other Steps, such as choosing SP conditions that minimize the risk of fieldworkers undergoing invasive tests. Secondly, fieldworkers should be trained intensively to avoid risks which cannot be removed by design (Table 5). One risk-minimizing strategy SPs will frequently need to use is the refusal of invasive tests; a particular challenge is ensuring that the reasons given for refusals come across as normal behaviour and do not raise suspicions. Despite these challenges, experience has shown that the SP method has minimal risk to fieldworkers equipped with proper training (Daniels et al., 2017) and need not inconvenience real patients (Das et al., 2015).

Table 5.

Strategies for minimizing harm to fieldworkers

| Risk | Design choices to minimize harm | Training strategies to minimize harm |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure to surface pathogens |

|

|

| Exposure to blood-borne infections | Avoiding SP cases which will require a venous blood draw |

|

| Exposure to airborne infections | Condition should not require extended period of time in areas of higher risk (e.g. TB clinics) |

|

| Harassment/abuse by providers |

|

|

| Invasive physical examinations | Avoiding SP cases which are likely to require intimate exams, e.g. STIs |

|

| Anxiety over health based on diagnoses received | Fieldworker pre-screening health form to establish no pre-existing conditions |

|

| Treatment or admission | Avoiding SP cases which are serious enough to require immediate treatment or admission |

|

Step 5: training fieldworkers and organizing fieldwork

Playing the role of an SP is more complex and demanding than standard fieldwork, so we recommend recruiting experienced and proven fieldworkers. Although some studies have recruited trained actors, experience indicates that while actors may perform well in improvisation and staying in character, adherence to protocol and precise recall of information are equally important. Many studies have, therefore, drawn from the same population they would use for any survey enumerator position and dedicated several weeks to selecting and training on SP skills.

The mix of SPs may also matter if quality is expected to vary by age, social group or other characteristics. For example, male and female SPs may receive different treatment (Borkhoff et al., 2009), so for cases relevant to both genders, hiring an even mix of men and women and randomly assigning them to facilities should be considered. Alternatively, cases may be portrayed by one gender only; this may be appropriate for cases such as family planning clients, but for other conditions may make the study less generalizable. Researchers should consider whether SPs will need a certain physical appearance to portray the case (e.g. a 60-year-old woman could not portray a family planning client), and the languages spoken by typical patients in the geographical areas of interest.

Administering a background health questionnaire at the start of training is a crucial first step for protecting fieldworkers, maintaining consistency of SP case presentation, and ensuring that real health conditions do not confound the interpretation of results. For example, the physical symptoms of poorly controlled asthma or hypertension may lead a provider to dismiss a possible diagnosis of TB in an SP with a cough and chest pain. This may require consultation with your institution’s Human Resources department to check that equal opportunity requirements are balanced with study needs.

Training should begin with an introduction to the concept of SPs, followed by fieldworkers reading and role-playing scripts. They should work in small groups to discuss the patient narrative and identify difficulties with phrasing or context-specific inconsistencies. For example, in a Tanzanian training session run by some of the authors, an initial draft of a script instructed the SP to say that they had never had an HIV test, but trainees noted that this would be implausible for female SPs with children, since HIV testing is ubiquitous in antenatal care there.

Emphasis should be placed on playing the role consistently, never giving more initial information than the opening statement, and then providing answers to only the questions the provider asks, which is essential for ensuring measurement reliability. As they learn about the study condition it can be tempting for SPs to help or guide the provider to a correct diagnosis, so training must explain why it is important to avoid this. Comparison across SP studies has confirmed that the amount of information provided heavily influences treatment choices by providers (Miller et al., 2018).

In most studies, each fieldworker performs only one SP case throughout the study. However, training fieldworkers in two roles gives the team more flexibility, though SPs should be randomly allocated to a role at each facility to avoid bias. In studies covering large geographies, it may not be possible for SPs to be randomly allocated to facilities, and an SP-specific variable should be controlled for as a fixed effect in the analysis (Das et al., 2016a). There should be no systematic differences in time of day or week of the visit by condition or SP – e.g. avoid the male SPs always visiting in the morning and female in the afternoon.

In studies in rural or remote locations, particular attention should be paid to ‘cover stories’, or how SPs explain their presence as an outsider if questioned. One resource-intensive approach is to research in advance the names of villages and people who SPs can say they are visiting, specific to every location. Alternatively, a number of stories can be developed for use in different contexts: e.g. that they are buying cash crops or livestock or researching places to sell second-hand clothing. Experience in the field has taught us that SPs should not improvise: some members of a team were detected after telling one provider they were agents for the government.

Once SPs understand their script and role, introduce them to the questionnaire. A useful training exercise is to have fieldworkers observe the same role-play, then complete the questionnaire separately. Comparing answers highlights difficult parts of the consultation to remember. The final stage of training is SPs practising their roles and questionnaires by making undercover visits to providers who have agreed to take part. It may be helpful for this to initially be done in pairs (e.g. posing as husband and wife) so that peer feedback can be provided.

If SPs are permitted to undergo certain diagnostic tests (e.g. fingerprick blood tests or urinalysis), we recommend that supervisors retest any fieldworker who receives a positive result for malaria or urinary tract infection. This will give peace of mind to the fieldworker (or allow for treatment if a true positive) and validate the facility’s test for the purpose of analysis. Supervisors can be trained to conduct malaria rapid diagnostic tests (mRDTs) and urine dipstick tests and be provided with a supply for the field.

SPs should purchase all drugs prescribed, if the budget allows, as this will reduce recall bias when recording drugs prescribed, improve the comprehensiveness of data on medicines, allow for the collection of drug costs and reduce the risk of raising provider suspicion. In addition, it may be possible to incorporate drug quality testing into the study (Wafula et al., 2017). To test the reliability of recall, SPs can carry covert audio recorders, although this may introduce additional ethical issues (Das et al., 2015).

Step 6: assessing detection

A follow-up study to assess the detection rate of SPs (i.e. the proportion of SPs identified by providers as being SPs and not genuine patients) is seen as an important step in ensuring the validity of results. Detection rates from recent health facility LMIC studies have typically varied from 0% to 5% (Das et al., 2015; Daniels et al., 2017; Sylvia et al., 2017), but there is no consensus on a maximum acceptable rate. Higher detection rates can be expected in rural settings compared with urban ones, where outsiders are likely to raise more suspicion. False-positive rates (providers report suspecting real patients to be SPs) varied from 1% to 6% in the same studies.

It may be advantageous to inform providers when obtaining consent that there will be a follow-up study and ask them to make a note of the name, description, symptoms and date if they receive any patients they suspect are SPs. This will allow for easy distinction between true and false detections at follow-up. However, priming providers in this way may increase the risk of detection, so the study team must decide whether they are willing to take this risk for the benefit of ease of classification. In addition, priming is not possible where a waiver of consent or institutional consent is used.

Dependent on setting and resources, the detection survey can be conducted as a face-to-face interview, or remotely by telephone or email. If face-to-face, the survey can be combined with other elements of the study, such as vignettes to measure provider knowledge and compare with SP performance to measure the know-do gap (Das et al., 2015; Mohanan et al., 2015; Sylvia et al., 2017). Carrying out such knowledge assessments after completion of SP visits has the advantage of being less likely to influence provider behaviour than if done before SP visits. In addition, if a waiver of consent has been used, the detection survey is an opportunity to inform providers that SP visits have taken place and allow them to ask questions and provide feedback.

The detection survey should start by briefly reminding (or in the case of a waiver of consent, informing) providers of the SP study’s aims and methods, then asking if the provider recalls receiving patients they suspected were SPs. For every suspected SP, the following information should be collected:

Date and time of visit (approximate if necessary)

Name, age (approximate) and gender of SP

Symptoms of SP

Diagnosis and treatment given by provider

The reason the provider suspected the patient was an SP

Whether the provider became suspicious during the visit or after it was complete

Whether the provider changed their treatment or confronted the SP due to their suspicions

These data should then be used to classify suspected SPs as true or false positives at the analysis stage. The stringency of a true positive definition will depend on setting, conditions and whether providers are primed. Some studies may require that the name of the SP is reported, but others may only require that the provider correctly identifies the gender and symptoms of the SP and gives a date of visit correct to within 1 week.

Conclusion

SPs are a valuable research tool, with enormous potential to improve the measurement of clinical quality in primary care settings. However, their undercover nature means that there are methodological and ethical challenges beyond those found in normal fieldwork. Moreover, SPs in health facilities are much more complex to implement than those in retail outlets. There is growing experience of developing and implementing a range of SP cases in diverse settings, and we hope that this article can help make such learning accessible to those planning similar studies.

The choices made when undertaking an SP study are highly dependent on the setting, purpose and resources. A well-designed study will draw on a thorough understanding of the health system in question. It will also capitalize on the contribution of fieldworkers during tool development, training and piloting to ensure cases are credible, rarely detected and minimize risk. The task of developing the script, backstory, symptoms and behaviour of an SP should not be underestimated. The process of implementing SPs must therefore be collaborative, incorporating both local knowledge and technical expertise on the SP method.

The absence of Hawthorne effects and the ability to observe healthcare as it is delivered, when controlling the condition and characteristics of that patient, make SPs a valuable tool, which can answer research questions no other method can. We also recognize that the SP method, as currently implemented, has its limitations. With this in mind, we conclude by offering a number of avenues for future methodological development (Box 4). These relate to challenges in investigating the continuity of care, defining correct treatment in different contexts, dealing with false-positive diagnostic tests, conducting power calculations and representativeness of the population of patients.

Box 4. Avenues for methodological developments

Can SPs be trained to make follow-up visits and, therefore, be used to investigate continuity of care in more complex conditions? The principal difficulty here is that in the first round, each SP will likely receive different recommendations, so a single SP condition can morph into multiple pathways when visits are repeated.

Should correct treatment vary by context? For instance, under what circumstances should referral to a higher-level facility be defined as correct management? Is referral a useful action in remote settings where patients are unlikely to access other facilities?

How should false positive diagnostic test results be managed? Are these accepted as part of random testing error or are they indicative of poor quality care?

How representative can SPs be of real patients and their interactions with doctors?

How can variability caused by SP characteristics be addressed in power calculations? Simulations have suggested that the number of individual SPs may be a critical factor for power calculations (Daniels et al., 2019).

Ethical approval. No ethical approval was required for this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Health Systems Research Initiative jointly funded by the Department of International Development, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (MR/N015061/1). Das acknowledges support from The World Bank’s Knowledge for Change Program. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its executive directors, or the governments they represent.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Alderman H, Das J, Rao V.. 2014. Conducting ethical economic research: complications from the field In: Demartino G, Mccloskey D (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Professional Economic Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press, 402–22. [Google Scholar]

- Aung T, Montagu D, Schlein K, Khine TM, Mcfarland W.. 2012. Validation of a new method for testing provider clinical quality in rural settings in low-and middle-income countries: the observed simulated patient. PLoS One 7: e30196.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Kreder HJ. et al. 2009. Patients’ gender affected physicians’ clinical decisions when presented with standardized patients but not for matching paper patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62: 527–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J. et al. 2017. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. The Lancet 390: 156–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian C, Gerdtham U-G, Hompashe D, Smith A, Burger R.. 2018. Measuring quality gaps in TB screening in South Africa using standardised patient analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 729.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Lin W, Meng J.. 2014. Addressing antibiotic abuse in China: an experimental audit study. Journal of Development Economics 110: 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Lin W, Zhang W.. 2011. Patient knowledge and antibiotic abuse: evidence from an audit study in China. Journal of Health Economics 30: 933–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels B, Dolinger A, Bedoya G. et al. 2017. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a pilot, cross-sectional study with international comparisons. BMJ Global Health 2: e000333.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Chowdhury A, Hussam R, Banerjee AV.. 2016a. The impact of training informal health care providers in India: a randomized controlled trial. Science 354: aaf7384.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B.. 2012. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Affairs 31: 2774–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Holla A, Mohpal A, Muralidharan K.. 2016b. Quality and accountability in health care delivery: audit-study evidence from primary care in India. American Economic Review 106: 3765–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Kwan A, Daniels B. et al. 2015. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of tuberculosis care: a pilot, cross-sectional study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 15: 1305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Woskie L, Rajbhandari R, Abbasi K, Jha A.. 2018. Rethinking assumptions about delivery of healthcare: implications for universal health coverage. The BMJ 361: k1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. 1988. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA 260: 1743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick A, Tumlinson K.. 2017. Strategies for optimal implementation of simulated clients for measuring quality of care in low- and middle-income countries. Global Health: Science and Practice 5: 108–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasziou P, Straus S, Brownlee S. et al. 2017. Evidence for underuse of effective medical services around the world. The Lancet 390: 169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanefeld J, Powell-Jackson T, Balabanova D.. 2017. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 95: 368.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Karim SA, Floyd K. et al. 2000. Syndrome packets and health worker training improve sexually transmitted disease case management in rural South Africa: randomized controlled trial. AIDS 14: 2769–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler PK, Marumo E, Jed SL. et al. 2017. A national evaluation using standardised patient actors to assess STI services in public sector clinical sentinel surveillance facilities in South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections 93: 247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan A, Daniels B, Saria V. et al. 2018. Variations in the quality of tuberculosis care in urban India: A cross-sectional, standardized patient study in two cities. PLOS Medicine 15: e1002653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Masatu MC.. 2010. Using the Hawthorne effect to examine the gap between a doctor’s best possible practice and actual performance. Journal of Development Economics 93: 226–34. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Masatu MC, Vialou A.. 2007. Getting doctors to do their best the roles of ability and motivation in health care quality. Journal of Human Resources 42: 682–700. [Google Scholar]

- Madden JM, Quick JD, Ross-Degnan D, Kafle KK.. 1997. Undercover careseekers: simulated clients in the study of health provider behavior in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine 45: 1465–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C, Guttmacher SJ, Flisher AJ. et al. 2009. The quality of HIV testing services for adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa: do adolescent-friendly services make a difference? Journal of Adolescent Health 44: 188–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Das J, Pai M.. 2018. Quality of tuberculosis care by Indian pharmacies: mystery clients offer new insights. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases 10: 6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan M, Vera-Hernández M, Das V. et al. 2015. The know-do gap in quality of health care for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia in rural India. JAMA Pediatrics 169: 349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi J, Gupta S, Peters DH.. 2010. Comparative analysis of exit interviews and direct clinical observations in Pediatric Ambulatory Care Services in Afghanistan. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 23: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M.. 2000. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 283: 1715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas ME, Garcia PJ, Bustelo M. et al. 2015. Effects of ethnic attributes on the quality of family planning services in Lima, Peru: a randomized crossover trial. PLoS One 10: e0115274.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Miller FG.. 2012. Simulated patient studies: an ethical analysis. Milbank Quarterly 90: 706–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia S, Xue H, Zhou C. et al. 2017. Tuberculosis detection and the challenges of integrated care in rural China: a cross-sectional standardized patient study. PLoS Medicine 14: e1002405.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafula F, Dolinger A, Daniels B. et al. 2017. Examining the quality of medicines at Kenyan healthcare facilities: a validation of an alternative post-market surveillance model that uses standardized patients. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 4: 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.