Abstract

This study addresses whether asthma and/or hay fever predict fertility and impaired fecundity. The lifetime number of pregnancies (fertility) and spontaneous pregnancy losses (impaired fecundity) in 10,847 women representative of the U.S. population 15 to 44 years of age with histories of diagnosed asthma and/or hay fever are analyzed in the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth using multivariable Poisson regression with multiple covariates and adjustments for complex sampling. Smokers have significantly increased fertility compared to nonsmokers. Smokers with asthma only have significantly increased fertility compared to other smokers. Higher fertility is associated with impaired fecundity (ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, stillbirth). Women with asthma (with and without hay fever) have significantly higher pregnancy losses than women without asthma. With increasing number of pregnancies, smokers have increased pregnancy losses compared to nonsmokers. Smokers, especially those with asthma only, have increased fertility and require special attention as to their family planning needs, reproductive health, and smoking cessation. Women with asthma, regardless of number of pregnancies, and smokers with higher numbers of pregnancies have high risk pregnancies that require optimal asthma/medical management prenatally and throughout pregnancy. Whether a proinflammatory asthma endotype underlies both the increased fertility and impaired fecundity associated with age and smoking is discussed.

Subject terms: Infertility, Asthma

Introduction

The increased prevalence of allergic respiratory disease worldwide1–3 is attributed in part to atopic women having more pregnancies resulting in live births than nonatopic women4 as both successful pregnancy5,6 and allergic diseas7,8 are associated with a type 2 (T2) immune response endotype i.e., group 2 innate lymphoid/adaptive T helper 2 cell immune response9,10. The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) is a cross-sectional survey representative of the U.S. population of women of reproductive age11. Questions pertaining to asthma and hay fever were requested by one of the authors (PCT) to be included in the 1995 NSFG to explore the relationship of allergic phenotype to fertility/fecundity. Fertility is defined as the capacity to establish a clinical pregnancy12. Fecundity is defined as the capacity to have a live birth12.

Although prior studies addressed fertility in women with asthma, these studies conceptualized fertility from different perspectives, analyzing live birth rates13, currently defined as fecundity12 or analyzing time to pregnancy >1 year14, currently defined as infertility12. While both of these approaches provide important information, they do not address the process leading from pregnancy to pregnancy loss and thus are not comparable to the current analysis.

We previously studied predictors of spontaneous pregnancy losses in women with asthma and/or hay fever based on their most recent singleton pregnancy15. The current study conceptualizes birth outcomes as a two-step process, becoming pregnant and carrying the pregnancy to term. Our previous study included only one pregnancy and its outcomes, it did not consider the possible contribution of asthma to the process of becoming pregnant or evaluate the contribution of the number of previous pregnancies to these outcomes. As a prior study indicated that the numbers of previous pregnancies increase the risk of pregnancy losses16, the current study analyzes the contributions of asthma and hay fever to the predictors of pregnancy loss controlling for the number of previous pregnancies.

Materials and Methods

NSFG design

The survey methodology is previously described11. In brief, data are drawn from the 1995 NSFG, a multistage probability sampling of the civilian non-institutionalized population of women 15 to 44 years of age, yielding estimates that are representative of the U.S population of women in this age range. The 1995 NSFG sample was drawn from a larger sample of households previously interviewed for the 1993 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). A complex stratified cluster sampling design was employed with oversampling of underrepresented groups. The 1993 NHIS respondent sample included data from 109,671 persons in 43,007 households selected from around the U.S. In all, a national probability sample of 14,000 women was drawn from the 1993 NHIS. This sampling methodology, used in conjunction with the sampling weights provided by the NSFG (see statistics section below), produced a nationally representative sample. Exclusions from the NSFG included not being born between April 1, 1950 – March 31, 1980, failing to respond or not complete the interview, parental consent not given if ages 15–17, leaving 10,847 women who completed the NSFG interview. Twenty-three women were excluded from this study due to missing asthma/hay fever data. The 1995 NSFG is the only one to include questions related to asthma and/or hay fever. Between January 1995 and October 1995 in-home interviews (90 minute) were conducted providing pregnancy and asthma/hay fever data for 10,824 women 15 to 44 years of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

NSFG 1995 Respondent Sample with Representation of U.S. Population of Women (15–44 years old).

| Characteristic | Range | NSFG Sample | US Population Represented | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SEM | ||

| Age at Interview (years) | 14–45 | 30.59 | 8.31 | 30.09 | 0.091 |

| Income (% Poverty Index)* | 12–998 | 315.35 | 219.59 | 331.06 | 2.91 |

| Number of Male Partners* | 0–21 | 4.9278 | 5.35 | 4.7953 | 0.07225 |

| Number of Pregnancies | 0–15 | 1.97 | 1.85 | 1.77 | 0.024 |

| Characteristic | N | Percent | Frequency | Frequency SE | |

| Total | 10,824 | 100.00% | 60,042,017.62 | 1,236,495.57 | |

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever | |||||

| Hay Fever Only | 1,339 | 12.30% | 7,410,212.758 | 257,315.408 | |

| Asthma Only | 584 | 5.40% | 3,269,640.363 | 156,235.741 | |

| Both | 540 | 5.00% | 3,015,416.326 | 162,835.575 | |

| Neither | 8,361 | 77.20% | 4,6346,748.17 | 1,000,351.235 | |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 2,511 | 14.00% | 8,445,847.71 | 385,472.47 | |

| White | 7,726 | 80.00% | 47,836,294.18 | 1,087,051.30 | |

| Other | 587 | 6.00% | 3,759,875.73 | 297,244.69 | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 1,549 | 11.00% | 6,686,275.83 | 438,992.52 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 5,290 | 49.40% | 29,669,734.41 | 677,835.715 | |

| Previously Married | 1,552 | 13.10% | 7,844,111.637 | 277,260.887 | |

| Never Married | 3,982 | 37.50% | 22,528,171.57 | 620,086.081 | |

| Geographic Region | |||||

| Northeast | 2,028 | 19.10% | 11,487,883 | 536,788.971 | |

| Midwest | 2,582 | 24.10% | 14,459,014.4 | 520,912.278 | |

| South | 3,742 | 33.60% | 20,169,863.1 | 549,600.568 | |

| West | 2,472 | 23.20% | 13,925,257.12 | 792,537.716 | |

| High School Diploma/GED** | 8,532 | 88.00% | 47,583,004.97 | 972,455.74 | |

| Pelvic Inflammatory Disease | 903 | 7.60% | 4,558,407.43 | 198,558.30 | |

| Diabetes (non-gestational) | 186 | 2.00% | 994,546.27 | 85,749.50 | |

| Hypertension | 891 | 7.0% | 4,377,586.23 | 196,425.32 | |

| BMI Category | |||||

| Underweight | 497 | 6.00 | 3,031,351.29 | 161,358.98 | |

| Normal Weight | 6,808 | 63.00% | 40,216,338.63 | 899,488.38 | |

| Overweight | 2,075 | 19.00% | 10,116,057.66 | 292,938.86 | |

| Obese | 1,444 | 13.00% | 6,678,270.04 | 202,392.44 | |

| Smoker (≥100 Lifetime Cigarettes) | 4,428 | 42.00% | 25,010,736.61 | 629,665.50 | |

| Had at Least 1 Pregnancy | 7,759 | 66.80% | 40,095,621.69 | 899,739.68 | |

| Number of Times Pregnant | |||||

| N | Percent | ||||

| 0 | 3,079 | 33.30% | 20,048,297.45 | 552,895.60 | |

| 1 | 1,777 | 16.40% | 9,893,230.44 | 314,673.16 | |

| 2 | 2,292 | 20.30% | 12,191,434.53 | 326,874.10 | |

| 3 | 1,702 | 14.20% | 8,551,352.35 | 285,268.12 | |

| 4 | 1,015 | 8.30% | 4,974,282.69 | 223,056.42 | |

| 5 | 507 | 3.90% | 2,323,131.31 | 121,537.23 | |

| 6 | 236 | 1.90% | 1,136,489.11 | 90,756.84 | |

| 7 | 123 | 0.90% | 536,492.65 | 53,971.42 | |

| 8 | 46 | 0.30% | 192,817.30 | 33,335.16 | |

| 9 | 28 | 0.20% | 148,972.52 | 29,542.86 | |

| 10 | 17 | 0.10% | 74,971.45 | 24,476.70 | |

| 11 | 6 | 0.00% | 25,902.09 | 11,016.81 | |

| 12 | 4 | 0.00% | 20,339.39 | 10,664.98 | |

| 13 | 3 | 0.00% | 12,304.49 | 7,941.76 | |

| 14 | 2 | 0.00% | 9,242.17 | 6,558.79 | |

| 15 | 1 | 0.00% | 4,659.22 | 4,659.22 | |

| Total Lifetime Pregnancies | 21,325 | 106,538,565.37 | 5,537,931.46 | ||

†Estimates of population represented based on sampling scheme and weighting used in NSFG 199511.

*Winsorized to 998 for income above 998% of poverty index and 21 for >=21 partners;

**General Equivalency Diploma.

Study variables

Pregnancy outcomes

The history of number of previous pregnancies, live births, spontaneous pregnancy losses (ectopic or tubal pregnancy, miscarriage, stillbirth), and induced abortions are obtained for each woman during the interview. Fertility is operationally defined as the number of previous pregnancies. Fecundity is operationally defined as the number of previous live births. Impaired fecundity is operationally defined as the number of previous spontaneous pregnancy losses. Number of pregnancies was also used as a predictor of impaired fecundity.

Lifetime history of asthma and/or hay fever

Lifetime histories of asthma and hay fever are based on responses to questions included in the NHIS that were added to the 1995 NSFG: “Has a doctor or other medical care provider ever told you that you had asthma (yes/no)”/”Has a doctor or other…….ever told you that you had hay fever (yes/no)”17. The responses are operationalized into four mutually exclusive categories: asthma only, hay fever only, asthma and hay fever, and neither asthma nor hay fever using three dummy variables with neither asthma nor hay fever as the reference group. The phenotypes, asthma and hay fever and hay fever only, are categorized differently from asthma only based on their significant association with allergen skin test positivity/sensitization18, especially during the early reproductive years (≤24 years old), whereas asthma only has a significantly lower association19. Self-reported histories of doctor diagnosed hay fever are also highly associated with aeroallergen skin test positivity, whereas self-reported histories of doctor diagnosed asthma are not19.

Lifetime history of smoking

The response to the question “In your entire life, have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes? (yes/no)” was used to differentiate lifetime nonsmokers (<100) from smokers (>100)17.

Demographics and health history

The demographic variables obtained included: age at interview, race and Hispanic origin, marital status, region of residence, high school graduation/general equivalency diploma (GED), and income defined as percent federal poverty index at time of interview. The health variables included the biological variables of history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), history of diabetes, history of high blood pressure, and Body Mass Index (BMI) classified as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (>/=30 kg/m2)17. The health behavior variable of number of male partners since puberty was also obtained.

Statistics

Initial descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Because the average age of first heterosexual vaginal intercourse is 1520, the number of years of a woman’s potential to become pregnant is calculated by subtracting 15 years from the age at interview. This is akin to mean centering to ensure estimates do not go beyond applicable age ranges. The number of pregnancies per year exposed is calculated for each woman. This rate is used as the fertility outcome. The number of live births per year exposed is calculated for each woman. This rate is the fecundity outcome. The number of spontaneous pregnancy losses per year exposed is calculated for each woman. This rate is used as the impaired fecundity outcome.

Demographic and health variables were added to the analyses as covariates/confounders. Confounders include smoking, age, BMI, race/ethnicity, percent federal poverty index, high school education/GED, and region of residence. Smoking increases the risk of asthma only, decreases the risk of hay fever only21 while increasing the risk of pregnancy loss22. Age impacts the ability to both become pregnant and maintain pregnancy while also influencing the risk of asthma in women23. Obesity increases the risk in women of asthma only15 as well as pregnancy loss24. As there is a nonlinear relationship between BMI and pregnancy outcomes, BMI categories were included as covariates with normal weight as the reference group. Race/ethnicity is associated with increased asthma prevalence in blacks, increased prevalence in whites of hay fever only21 as well as influencing fertility and fecundity25. Percent federal poverty index is related to risk of asthma21 as well as fertility and fecundity26. High school graduation/GED status is related to diagnosis of asthma27 as well as risk of pregnancy loss15. Region of residence influences risk of asthma21 as well as fecundity28. Covariates include number of male partners, marital status, PID, hypertension, and diabetes. Number of male partners and marital status are associated with fertility. Marital status15, PID15, hypertension29, and diabetes30 are associated with the risk of pregnancy loss.

Poisson regression was used to examine the contribution of asthma and/or hay fever to fertility after controlling for covariates/confounders. Covariates and confounders in the analysis included: smoking, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, region, high school education/GED, income as % poverty index, history of PID, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, BMI, and number of male partners. The potential moderating effect of smoking on the relationship of asthma to fertility was examined by including interaction terms between smoking and asthma/hay fever phenotype into this analysis.

Stratified multivariable Poisson regression analysis was conducted according to smoking status: non-smokers (smoked less than 100 cigarettes in the lifetime) and smokers (smoked 100 or more cigarettes in the lifetime). The analysis of women nonsmokers provided an opportunity to evaluate the relation between asthma/hay fever phenotypes and fertility not confounded by smoking. This analysis included all covariates/confounders from the previous analysis with the exception of the smoking-related variables. The number of smokers/nonsmokers in each asthma/hay fever phenotype ranged between 244 to 775.

Another set of Poisson regression analysis was used to evaluate the contributions of asthma and or hay fever to impaired fecundity. The analysis included only women who had at least one pregnancy that did not end in induced abortion. Initial analyses included examination of the contribution of fertility and of asthma and/or hay fever to impaired fecundity. These were followed by models that included demographic, health, and behavior covariates in addition to these variables. For these analyses, number of pregnancies was a key predictor along with asthma/hay fever phenotype. The covariates/confounders in this set of analyses included: smoking, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, region, high school education/GED, income as % poverty index, history of PID, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, BMI, and number of male partners.

The potential moderating role of asthma only in the relationship between fertility and impaired fecundity was examined in Poisson regression models by adding an interaction term between asthma only (dichotomous) and number of pregnancies per woman year to Poisson regression with asthma only and number of pregnancies as predictors. The graphs illustrate the interactions of fertility with asthma-hay fever status and with smoking status as predictors of impaired fecundity. These analyses controlled for the covariates and confounders included above. These graphs include estimates of pregnancy losses for 70 and 170 pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years, the 25th (NP25) and 75th percentiles (NP75) respectively.

STATA version 12 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) statistical software program svy was used for multivariable analyses. It computes accurate variances that account for the stratified cluster sampling and oversampling of some subgroups in the sampling design of the NSFG. The NSFG data set variable PANEL was included as the cluster variable, COL_STR as the strata variable, and POST_WT as the sampling weight in all analyses. Estimated marginal means were compared using t-tests with Holm’s sequential Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons.

Ethics

The 1995 NSFG survey was carried out in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. The 1995 NSFG survey protocols were reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Institutional Review Board/NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or if subjects were under 18 years old from a parent or legal guardian.

Results

Demographics

A total of 10,824 women in the NSFG represents approximately 60 million US women aged 15–44 years. Of these 66.8% have at least one pregnancy by the time of their interview experiencing a total of 21,325 pregnancies, with the number of pregnancies ranging from 0 to 15 per woman. Demographic, health, and behavioral data for the sample and the population they represent are presented in Table 1.

Fertility (number of pregnancies per woman-year)

Women experienced a mean fertility rate of 106.14 pregnancies per 1000 woman-years (95% CI = 103.0, 109.3). In Poisson regression with all aforementioned covariates, asthma only is a significant independent predictor of more pregnancies compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever. No significant differences in number of pregnancies are observed in women with asthma and hay fever or hay fever only compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever. (Table 2). Younger age, lower income, and less education (no high school diploma/GED) independently predict higher number of pregnancies per fertile year after controlling for asthma/hay fever and all other covariates. Being married or previously married (compared with never married), Hispanic or non-Hispanic black (compared with non-Hispanic white), being overweight (compared with normal weight), smoking (≥lifetime 100 cigarettes), and having more male partners since puberty also independently predict higher number of pregnancies after controlling for all other covariates/confounders (Table 2). Smoking is also associated with higher fertility (Table 2). Based on these findings, the interactions between smoking and the asthma and hay fever variables were added to the Poisson regression model.

Table 2.

Fertility in All Women: Results of Poisson regression examining the independent contributions of asthma/hay fever categories and other predictors to number of pregnancies per woman-year in women aged 15–44 years in the NSFG (*N = 9,284).

| Characteristic | Coeff. | Std. Error | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever | |||||

| Asthma Only | 0.1196 | 0.0482 | 2.48 | 0.014 | 0.0245, 0.2148 |

| Hay Fever Only | 0.0053 | 0.0320 | 0.17 | 0.868 | −0.0578, 0.0685 |

| Asthma & Hay Fever | 0.0203 | 0.0452 | 0.45 | 0.654 | −0.0688, 0.1093 |

| Neither | (ref) | ||||

| Age | −0.0204 | 0.0016 | −12.9 | <0.001 | −0.0235, −0.0173 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.1625 | 0.0311 | 5.23 | <0.001 | 0.1012, 0.223 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.3935 | 0.0276 | 14.28 | <0.001 | 0.3392, 0.4479 |

| Non-Hispanic Others | 0.0641 | 0.054 | 1.19 | 0.234 | −0.0417, 0.1700 |

| Non-Hispanic White | (ref) | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 0.8643 | 0.0386 | 22.41 | <0.001 | 0.7882, 0.9403 |

| Previously Married | 0.6572 | 0.0440 | 14.95 | <0.001 | 0.5704, 0.7439 |

| Never Married | (ref) | ||||

| Region | |||||

| North East | 0.0077 | 0.0319 | 0.24 | 0.810 | −0.0553, 0.0706 |

| Midwest | −0.0407 | 0.0354 | −1.15 | 0.251 | −0.1105, 0.0290 |

| South | −0.1515 | 0.0289 | −5.24 | <0.001 | −0.2086, −0.0945 |

| West | (ref) | ||||

| High School Grad or GED | −0.3651 | 0.0275 | −13.28 | <0.001 | −0.4193, −0.3108 |

| % Poverty Index | −0.0012 | 0.0011 | −20.01 | <0.001 | −0.0014, −0.0011 |

| PID | 0.0602 | 0.0321 | 1.87 | 0.063 | −0.0032, 0.1236 |

| Diabetes | −0.1410 | 0.0902 | −1.56 | 0.120 | −0.3190, 0.0370 |

| Hypertension | −0.0708 | 0.0386 | −1.84 | 0.068 | −0.1469, 0.0053 |

| BMI Category | |||||

| Underweight | <0.0015 | 0.0485 | 0.01 | 0.992 | −0.0951, 0.0961 |

| Overweight | 0.0889 | 0.0205 | 4.33 | <0.001 | 0.0484, 0.1294 |

| Obese | 0.0504 | 0.0262 | 1.92 | 0.056 | −0.0014, 0.1021 |

| Normal Weight | (ref) | ||||

| Smoker | 0.1265 | 0.0191 | 6.61 | <0.001 | 0.0887, 0.1642 |

| Number Male Partners | 0.0226 | 0.0018 | 12.78 | <0.001 | 0.0191, 0.0261 |

| Constant | −1.709 | 0.0684 | −24.99 | <0.001 | −1.8439, −1.5741 |

GED general equivalency diploma; ref reference group.

*N reduced due to missing data.

Fertility in smokers/nonsmokers with asthma/hay fever phenotypes

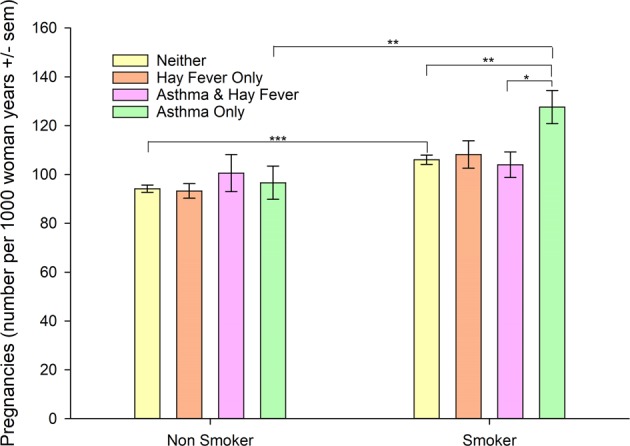

The significant interaction between asthma only and smoking (β = 0.1590, t = 1.97, 95% CI = 0.0000, 0.3180, p = 0.05) indicates that the presence of both is associated with increases in the number of pregnancies (Table 2). None of the other asthma/hay fever interactions with smoking were significant. Estimates of fertility (number of pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years) in smokers and non-smokers according to asthma/hay fever status and smoking status, controlling for all other covariates shown in Table 2, are included in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Estimated fertility (number of pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years) according to asthma/hay fever diagnosis and smoking status controlling for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, region, education, income, pelvic inflammatory disease, diabetes, hypertension, BMI, and number of male partners from the NSFG (N = 9,284). Estimates based on complex samples analysis in Table 2 adjusted for multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In smokers, there is no significant difference in fertility between women with hay fever only compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever. Among non-smokers there is also no significant difference in fertility in women with hay fever only or asthma and hay fever compared to women nonsmokers with neither asthma nor hay fever (Fig. 1). The pattern of the significance of the relationships of the other covariates from age to number of male partners (Table 2) to number of pregnancies did not change.

The moderation effect of smoking on the relationship of asthma/hay fever status to number of pregnancies is evaluated using stratified multivariable Poisson regression analyses performed on non-smokers (Table 3) and smokers (Table 4). Among women who smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes (non-smokers), asthma only is not a significant independent predictor of the number of pregnancies per woman year compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever (Table 3). The relationships of the other covariates to number of pregnancies remains relatively unchanged except for hypertension which predicts lower numbers of pregnancies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fertility in Women Nonsmokers: Results of Poisson regression examining the independent contributions of asthma/hay fever categories and other predictors to number of pregnancies per woman-year in nonsmokers (<100 lifetime cigarettes) aged 15–44 years in the NSFG (N = 5,197).

| Characteristic | Coeff. | Std. Error | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever | |||||

| Asthma Only | 0.0324 | 0.0665 | 0.49 | 0.626 | −0.0988, 0.1637 |

| Hay Fever Only | −0.0194 | 0.0345 | −0.56 | 0.576 | −0.08751, 0.0487 |

| Asthma & Hay Fever | 0.0684 | 0.0762 | 0.90 | 0.370 | −0.0819, 0.2187 |

| Neither | (ref) | ||||

| Age | −0.0113 | 0.0019 | −5.85 | <0.001 | −0.0151, −0.0075 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.1157 | 0.0420 | 2.75 | 0.007 | 0.0328, 0.1986 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.4673 | 0.0355 | 13.17 | <0.001 | 0.3973, 0.5373 |

| Non-Hispanic Others | 0.0101 | 0.0656 | 0.15 | 0.877 | −0.1194, 0.1396 |

| Non-Hispanic White | (ref) | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 1.026 | 0.0509 | 20.17 | <0.001 | 0.9257, 1.1265 |

| Previously Married | 0.6865 | 0.0568 | 12.08 | <0.001 | 0.5744, 0.7986 |

| Never Married | (ref) | ||||

| Region | |||||

| North East | 0.0309 | 0.0433 | 0.71 | 0.476 | −0.0545, 0.1162 |

| Midwest | −0.0230 | 0.0470 | −0.49 | 0.625 | −0.1158, 0.0697 |

| South | −0.1391 | 0.0431 | −3.23 | 0.001 | −0.2240, −0.0541 |

| West | (ref) | ||||

| High School Grad or GED | −0.3922 | 0.0385 | −10.19 | <0.001 | −0.4682, −0.3163 |

| % Poverty Index | −0.0015 | 0.0011 | −16.67 | <0.001 | −0.0017, −0.0013 |

| PID | 0.0939 | 0.0491 | 1.91 | 0.058 | −0.0031, 0.1908 |

| Diabetes | −0.0443 | 0.1525 | −0.29 | 0.772 | −0.3452, 0.2566 |

| Hypertension | −0.1143 | 0.0449 | −2.54 | 0.012 | −0.2029, −0.0256 |

| BMI Category | |||||

| Underweight | −0.0817 | 0.0761 | −1.07 | 0.285 | −0.2319, 0.0685 |

| Overweight | 0.0659 | 0.0315 | 2.09 | 0.038 | 0.0037, 0.1281 |

| Obese | 0.0590 | 0.0373 | 1.58 | 0.115 | −0.0145, 0.1326 |

| Normal weight | (ref) | ||||

| Number Male Partners | 0.0255 | 0.0031 | 8.34 | <0.001 | 0.0195, 0.0315 |

| Constant | −2.0227 | 0.0928 | −21.79 | <0.001 | −2.2059, −1.8396 |

GED general equivalency diploma; ref reference group.

Table 4.

Fertility in Women Smokers: Results of Poisson regression examining the independent contributions of asthma/hay fever categories and other predictors to number of pregnancies per woman-year in smokers (≥100 lifetime cigarettes) aged 15–44 years in the NSFG (N = 4,037).

| Characteristic | Coeff. | Std. Error | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever | |||||

| Asthma Only | 0.1934 | 0.0563 | 3.44 | 0.001 | 0.0824, 0.3044 |

| Hay Fever Only | 0.0228 | 0.0504 | 0.45 | 0.652 | −0.0767, 0.1222 |

| Asthma & Hay Fever | −0.0303 | 0.0521 | −0.58 | 0.562 | −0.1331, 0.0726 |

| Neither | (ref) | ||||

| Age | −0.0292 | 0.0024 | −12.41 | <0.001 | −0.0339, −0.0246 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.2086 | 0.0410 | 5.08 | <0.001 | 0.1277, 0.2896 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.3258 | 0.0409 | 7.97 | <0.001 | 0.2451, 0.4065 |

| Non-Hispanic Others | 0.1516 | 0.0889 | 1.71 | 0.090 | −0.0238, 0.3270 |

| Non-Hispanic White | (ref) | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 0.6790 | 0.0504 | 13.47 | <0.001 | 0.5796, 0.7785 |

| Previously Married | 0.5734 | 0.0592 | 9.68 | <0.001 | 0.4565, 0.6903 |

| Never Married | (ref) | ||||

| Region | |||||

| North East | −0.0240 | 0.0402 | −0.60 | 0.550 | −0.1034, 0.0553 |

| Midwest | −0.0671 | 0.0453 | −1.48 | 0.141 | −0.1565, 0.0224 |

| South | −0.1715 | 0.0367 | −4.68 | <0.001 | −0.2438, −0.0991 |

| West | (ref) | ||||

| High School Grad or GED | −0.3506 | 0.0373 | −9.40 | <0.001 | −0.4242, −0.2770 |

| % Poverty Index | −0.0010 | 0.0000 | −12.50 | <0.001 | −0.0011, −0.0008 |

| PID | 0.0344 | 0.0439 | 0.79 | 0.443 | −0.0521, 0.1210 |

| Diabetes | −0.1621 | 0.0836 | −1.94 | 0.054 | −0.3271, 0.0029 |

| Hypertension | −0.0341 | 0.0565 | −0.60 | 0.547 | −0.1455, 0.0773 |

| BMI Category | |||||

| Underweight | 0.0737 | 0.0657 | 1.12 | 0.263 | −0.0559, 0.2033 |

| Overweight | 0.1071 | 0.0279 | 3.84 | <0.001 | 0.0521, 0.1623 |

| Obese | 0.0197 | 0.0378 | 0.46 | 0.645 | −0.0572, 0.0921 |

| Normal Weight | (ref) | ||||

| Number Male Partners | 0.0175 | 0.0021 | 9.10 | <0.001 | 0.0155, 0.0240 |

| Constant | −1.2141 | 0.0884 | −13.73 | <0.001 | −1.389, −1.040 |

GED general equivalency diploma; ref reference group.

Among smokers, asthma only is a significant independent predictor of increased number of pregnancies per woman year compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever (Table 4). In smokers, hay fever only and asthma and hay fever are not significant independent predictors of the number of pregnancies compared to women with neither asthma nor hay fever (Table 4). The relationships of the other covariates to number of pregnancies in smokers remains relatively unchanged (Table 4) compared to the analysis of all women (Table 2).

Fecundity (number of live births per woman-year)/Impaired Fecundity (number of spontaneous pregnancy losses per woman-year)

Fecundity and impaired fecundity were examined using pregnancies that did not end in induced abortions. Pregnancy losses and number of pregnancies (excluding abortion) are available from 7,658 respondents who had been pregnant at least once, representing approximately 39,413,900 women. Women experienced 135.0 pregnancies per 1000 woman-years (95% CI = 132.1, 138.1) that did not end in induced abortion. Among these women were 401 respondents, representing approximately 2.5 million women, who reported zero pregnancies that did not end in abortion. The pregnancies resulted in 110.33 live births per 1000 woman-years and 25.0 spontaneous pregnancy losses per 1000 woman-years (95% CI = 23.1, 26.3) occurring in 18.5% of pregnancies reported. Five thousand four hundred eighty-five (5,485) respondents (71.6%), representing approximately 28 million women, did not experience spontaneous pregnancy losses.

Asthma phenotypes and impaired fecundity

Asthma only is analyzed as a contributor to the relationship of number of pregnancies and pregnancy losses. In bivariate Poisson regression analyses, asthma only, operationalized as a dichotomous variable, predicts both higher number of pregnancies (β = 0.2957, t = 6.76, 95% CI = 0.2094, 0.3819, p < 0.001) and higher pregnancy losses (β = 0.6807, t = 5.37, 95% CI = 0.4308, 0.9306, p < 0.001).

The role of asthma only as a moderator of the relationship between pregnancy and pregnancy losses is examined using Poisson regression. With the number of pregnancies per woman-year, asthma only and their interaction as predictors of spontaneous losses per woman-year, their interaction is a significant independent predictor (β = 0.9330, t = 2.03, 95% CI = 0.0283, 1.8380, p = 0.043). The greater the number of pregnancies, the greater the contribution of asthma only to pregnancy losses.

Smoking and impaired fecundity

The role of smoking as a moderator of the relationship between pregnancies and pregnancy losses is examined in Poisson regression. With the number of pregnancies per woman-year, smoking and their interaction as predictors of pregnancy losses per woman-year, their interaction is a significant independent predictor (β = −1.5709, t = −3.42, 95% CI = −2.4760, −0.6658, p = 0.001). The greater the number of pregnancies, the lesser the relationship of smoking to pregnancy losses. The relationship of number of pregnancies to the number of pregnancy losses is lower in smokers than in non-smokers.

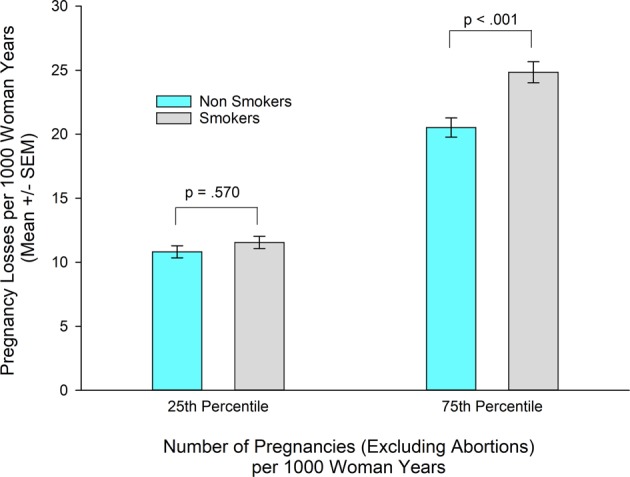

Rates of pregnancy losses in smokers/nonsmokers

The association of the interaction of smoking and number of pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years with spontaneous pregnancy losses per 1,000 woman-years is illustrated in Fig. 2. The estimate of the rate of pregnancy losses among smokers at NP75 is significantly higher than among nonsmokers after controlling for all covariates/confounders. In contrast, there is no significant difference in rates of pregnancy losses of smokers compared to nonsmokers at NP25.

Figure 2.

Estimated impaired fecundity (number of pregnancy losses per 1000 woman-years) according to smoking status and number of pregnancies per thousand woman years, controlling for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, region, education, income, pelvic inflammatory disease, diabetes, hypertension, BMI, number of male partners and number of pregnancies as well as the interaction between asthma/hay fever status and number of pregnancies from the NSFG (N = 9,284). Estimates based on complex samples analysis in Table 5 adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Asthma phenotypes/smoking and impaired fecundity

A multivariable Poisson regression analysis of number of spontaneous pregnancy losses that includes the four categories of asthma and/or hay fever and all the previous covariates/confounders plus interaction terms for asthma/hay fever categories with number of pregnancies and for smoking with number of pregnancies is present in Table 5. The interaction of asthma only with number of pregnancies per woman year and the interaction of smoking with number of pregnancies, each are independent predictors of greater number of pregnancy losses per woman-year. None of the other asthma/hay fever categories had significant interactions with number of pregnancies as predictors of number of pregnancy losses. Other significant predictors of pregnancy losses are the number of pregnancies, being older, never being married, having a high school diploma, higher income, PID, and more male partners (Table 5). These findings suggest independent roles of asthma only and smoking in the process leading from number of pregnancies to pregnancy losses.

Table 5.

Association of fertility with impaired fecundity: Results of Poisson regression examining the independent contributions of pregnancies per woman-year (excluding abortion), asthma only, smoking, the interactions of asthma and of smoking with number of pregnancies and other predictors to number of spontaneous pregnancy losses per woman-year (excluding abortion) in women aged 15–44 years in the NSFG (*N = 7,239).

| Characteristic | Coeff. | Std. Error | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pregnancies (P) | 6.4854 | 0.2780 | 23.33 | <0.001 | 5.9369, 7.0340 |

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever | |||||

| Asthma Only | 0.4240 | 0.1452 | 2.92 | 0.004 | 0.1375, 0.7105 |

| Hay Fever Only | 0.0229 | 0.1274 | 0.18 | 0.858 | −0.2286, 0.2743 |

| Asthma & Hay Fever | 0.3496 | 0.1203 | 2.91 | 0.004 | 0.1123, 0.5869 |

| Neither | (ref) | ||||

| Smoke | −0.0253 | 0.0688 | −0.37 | 0.714 | −0.1611, 0.1105 |

| Asthma and/or Hay Fever X† P | |||||

| Asthma Only X P | −1.1133 | 0.3811 | −2.92 | 0.004 | −1.8651, −0.3615 |

| Hay Fever Only X P | −0.0954 | 0.6940 | −0.14 | 0.891 | −1.4646, 1.2738 |

| Asthma & Hay Fever X P | −0.9257 | 0.4924 | −1.88 | 0.062 | −1.8970, 0.0456 |

| Smoke X P | 1.3020 | 0.3130 | 4.16 | <0.001 | 0.6846, 1.9194 |

| Age | 0.0228 | 0.0046 | 4.96 | <0.001 | 0.0137, 0.0318 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | −0.0811 | 0.0711 | −1.14 | 0.255 | −0.2213, 0.0591 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.1286 | 0.0791 | −1.62 | 0.106 | −0.2846, 0.0276 |

| Non-Hispanic Others | −0.0617 | 0.1444 | −0.43 | 0.670 | −0.3465, 0.2231 |

| Non-Hispanic White | (ref) | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | −0.2169 | 0.0872 | −2.49 | 0.014 | −0.3890, −0.0449 |

| Previously Married | −0.2221 | 0.0967 | −2.30 | 0.023 | −0.4128, −0.0313 |

| Never Married | (ref) | ||||

| Region | |||||

| North East | −0.0076 | 0.0708 | −0.11 | 0.915 | −0.1473, 0.1322 |

| Midwest | −0.1018 | 0.0847 | −1.20 | 0.231 | −0.2689, 0.0654 |

| South | 0.0192 | 0.0731 | 0.26 | 0.793 | −0.1250, 0.1634 |

| West | (ref) | ||||

| High School Grad or GED | 0.2237 | 0.0652 | 3.43 | <0.001 | 0.0951, 0.3522 |

| % Poverty Index | 0.0010 | 0.0001 | 8.40 | <0.001 | 0.0007, 0.0012 |

| PID | 0.3044 | 0.0712 | 4.27 | <0.001 | 0.1639, 0.4449 |

| Diabetes | −0.0479 | 0.2445 | −0.20 | 0.845 | −0.5302, 0.4344 |

| Hypertension | −0.0058 | 0.0930 | −0.06 | 0.951 | −0.1891, 0.1776 |

| BMI Category | |||||

| Underweight | 0.0904 | 0.0993 | 0.91 | 0.364 | −0.1055, 0.2863 |

| Overweight | 0.0352 | 0.0591 | 0.60 | 0.552 | −0.0814, 0.1517 |

| Obese | 0.1031 | 0.0828 | 1.25 | 0.214 | −0.0601, 0.2664 |

| Number Male Partners | 0.0088 | 0.0045 | 1.98 | 0.050 | 0.0000, 0.0768 |

| Constant | −6.1463 | 0.2041 | −30.11 | <0.001 | −6.5490, −5.7436 |

X† = interaction; GED general equivalency diploma; ref reference group.

*N reduced due to missing data.

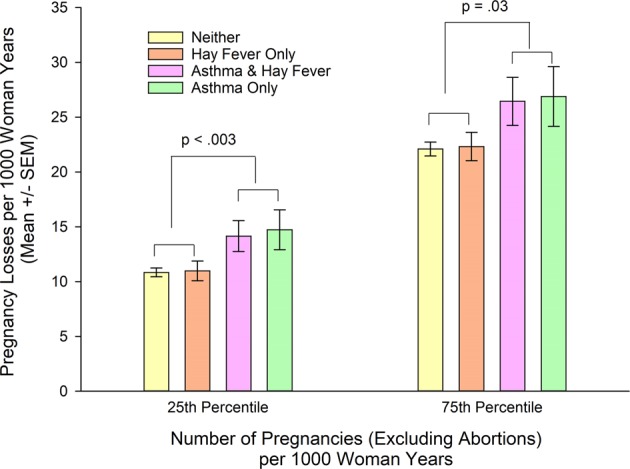

Rates of pregnancy losses in asthma/hay fever phenotypes

The association of the interactions of asthma and/or hay fever and number of pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years with spontaneous pregnancy losses per 1,000 woman-years is illustrated in Fig. 3. At NP75, neither of the estimates of rates of pregnancy losses with asthma only (26.90 ± 2.73) nor of asthma and hay fever (26.45 ± 2.20) are significantly different from the estimate for women with neither asthma nor hay fever [22.10 ± 0.63); t(5924) = 1.84, p = 0.065 and t(5935) = 1.72, p = 0.17, respectively]. In contrast, the estimate of rates of pregnancy losses in women with asthma only at NP25 (14.74 ± 1.81) is significantly higher compared to women with neither [10.84 ± 0.40, t(5924) = 2.38, p = 0.017], whereas the rate in women with asthma and hay fever (14.16 ± 1.41) is not significantly different from women with neither [10.84 ± 0.40; t(5935) = 2.09, p = 0.074]. Although not reaching statistical significance, the rates of spontaneous pregnancy losses for asthma and hay fever are similar to asthma only (Fig. 3). The contribution of number of pregnancies to pregnancy losses depends on asthma (with and without hay fever) [β = 0.9977, t = 2.97, 95% CI = 0.3359, 1.6596, p = 0.003]. After grouping asthma only and asthma and hay fever together, asthma predicts significantly increased rates of spontaneous pregnancy losses compared with women without asthma after controlling for interactions and covariates/confounders. Figure 3 illustrates estimated spontaneous pregnancy losses at NP25 and NP75.

Figure 3.

Estimated impaired fecundity (number of pregnancy losses per 1000 woman-years) according to asthma/hay fever status and number of pregnancies per thousand woman years, controlling for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, region, education, income, pelvic inflammatory disease, diabetes, hypertension, BMI, number of male partners, and number of pregnancies as well as the interaction of number of pregnancies with smoking from the NSFG (N = 9,284). Estimates based on complex samples analysis in Table 5 adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

Fertility findings in the current analysis are consistent with U.S. data. The overall fertility rate of 106.14 pregnancies per 1,000 woman-years is similar to that previously reported31. Asthma only, smoking, and younger age are predictors of significantly higher fertility (Table 2) consistent with the highest U.S. pregnancy rate (1976–1996) in the age 20–24 cohort25. The differing asthma/hay fever phenotypes and their associated endotypes provide an immunologic rationale for the association of smoking and asthma only smokers with increased fertility. Asthma/hay fever phenotypes differ by age and smoking in their association with allergen skin test positivity19. During the early reproductive years (≤24 years old), the clinical phenotypes hay fever only, regardless of smoking, and asthma and hay fever in nonsmokers are significantly associated with aeroallergen skin test positivity (number of positive skin tests)19. Skin test positivity to either ragweed or rye grass in the U.S. population (<24 years old) increases the odds of hay fever only 160–200% and skin test positivity to Alternaria increases the odds of asthma and hay fever 860%32. Proteases in ragweed, rye grass, and Alternaria aeroallergens can activate a T2 immune response33. These clinical phenotypes are atopic, consistent with T2 inflammatory endotypes, respectively termed T2 immune response rhinitis9,10 and T2-high asthma34,35. T2-high asthma is associated with eosinophilia36. The asthma and hay fever phenotype accounts for about 50% of asthma prevalence37 in women (Table 1) and has been characterized as being mild to moderate in severity34.

In contrast, the prevalence of asthma only (without hay fever) in the early reproductive years as well as during the later reproductive years (25–49 years of age) in nonsmokers has a significantly lower association with aeroallergen skin test positivity19 and include endotypes classified as T2-low asthma37–39/non-T2 Type 1 (T1) asthma34,40. The nonatopic phenotype, asthma only, also accounts for about 50% of asthma39,41 and “…may be highly prevalent in mild to moderate asthmatics in the general population”.42

Immune deviation from a T2-high asthma to a T2-low asthma/T1 endotype is characterized by biomarkers of neutrophil recruitment e.g., IL-1alpha, IL-6, IL-843, innate immune response dysregulation e.g., IL-23, TNF alpha, interferon, IL-1744–48, and includes neutrophilic noneosinophilic asthma49. Neutrophilic asthma is significantly increased in smokers with asthma compared to nonsmokers with asthma50 and in previous smokers with severe asthma compared to never smokers with severe asthma51.

The proinflammatory T2-low asthma endotype has similar biomarker characteristics to the fetal-maternal interface during implantation. Prior to implantation52,53 and in the peri-implantation period the fetal-maternal interface is also characterized by immune deviation to a proinflammatory54 (IL-1beta, IL-6, LIF, PGE2, CXCL8, IL-17A, TNF) T2-low endotype55–57. Insemination, exposure to semen, initiates a short lived neutrophilic inflammatory (IL-1beta, TNF alpha, CxCL1, IL-17A) internal genital response58–60. The placental cytokines, IL-1beta, IL-6, TNFalpha, as well as increased PGE261,62, are also associated with early onset (2 weeks after fertilization) pregnancy symptoms e.g., nausea/vomiting62. PGE2, a negative regulator of type 2 innate lymphoid cell response63, is a mediator of cough variant asthma64,65 in whom half studied are nonatopic and nearly two-thirds women66,67. Soluble HLA-G is both a biomarker of the T2-low asthma endotype68 and a tolerance inducing MHC molecule that facilitates implantation at the fetal-maternal interface69. It is found in T2-low severe asthma in whom two-thirds studied were women and fifty percent on oral glucocorticosteroids68.

Smoking significantly increases the risk of asthma only in the U.S population21 and elicits a systemic proinflammatory response70–72 including IL-1beta and IL-17 shifted cytokine profiles73. Thus deviation towards a T2-low endotype in smokers and smokers with asthma only may be permissive for embryo implantation in the early and prime reproductive years underlying the significantly positive interaction observed between smoking and asthma only (see Results) that predicts an even greater increase in fertility for asthma only smokers compared to other smokers (Fig. 1) and significantly increased fertility in smokers compared to nonsmokers. In healthy women, there is a balance of T2-high and T2-low endotypes during embryo implantation74.

Predictors of fertility are consistent with previous studies. Proximate behavioral determinants of fertility include sexual exposure e.g., number of partners, marital/cohabiting status, and contraception75. Increased fertility of married women, of non-Hispanic blacks, of Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites, lower income, and educational attainment (Tables 2–4) have been reported26,76. In this respect, sexually active Hispanic, non-Hispanic black women, and women with lower education or lower income report lower use of contraceptives77. Differences in fertility associated with overweight/obesity may be due to behavioral factors as obese women utilize sterilization as a method of contraception more often78, have decreased marriage rates79, and a significantly higher risk of lifetime childlessness than overweight women80. Smoking is associated with risky sexual/health behaviors81, sexually transmitted diseases82–85, number of sexual partners85,86, and failure to use contraception86.

The covariates/confounders significantly associated with spontaneous pregnancy losses in the current study (Table 5) are consistent with those in previous reports. The percent of women (28.4%) experiencing a spontaneous pregnancy loss (see Results: Fecundity) is similar to the 28% recently reported87. Predictors of spontaneous pregnancy losses previously reported include increased age15,88, history of PID15,89,90, high school graduate15 (or equivalent)16/higher education88, never having married15,88, higher income16,88, prior pregnancies88, smoking22, and number of male partners91.

The number of pregnancies is a significant independent predictor of pregnancy losses (Table 5). Women with pregnancy losses i.e., impaired fecundity are less likely to use contraceptives and more likely to have unintended pregnancies92. In interviews of women with impaired fecundity who had unintended pregnancies, over 60% of those who became pregnant believe they could not become pregnant or didn’t mind becoming pregnant92. As ovulation resumes 20 days (median) after a spontaneous pregnancy loss and before the next menses, women may not have the necessary reproductive health information to be aware they may be able to conceive shortly after miscarriage93,94. Thus women with impaired fecundity may not be prepared to use contraception sufficiently early after a miscarriage95 or have information pertinent to the most effective contraceptive methods96.

This study which analyzes history of previous pregnancy losses contrasts with our previous analyses of pregnancy loss based on the most recent singleton pregnancy. In that study, women (including smokers) with asthma only, but not women with asthma and hay fever, experienced an 80% increased odds of spontaneous pregnancy loss compared to those who had neither asthma nor hay fever15. Nonsmokers with either asthma only or asthma and hay fever, in that study, also did not have increased pregnancy loss15. Similarly, in this study, when individual phenotypes are analyzed, only women with asthma only at the lower number of previous pregnancies (NP25) have significantly increased rates of pregnancy losses (see Results: Rates of pregnancy losses in asthma/hay fever phenotypes). Common to both studies, smoking is an independent predictor of increased fertility (Table 2) in this study and a mediator with asthma of spontaneous pregnancy loss based on the most recent singleton pregnancy15. This pattern of pregnancy loss in our prior study in which the significant increase in pregnancy loss is observed only in women with asthma only that included smokers is similar to the pattern of fertility in this study in which the significant increase in fertility is observed only in asthma only smokers (Fig. 1) suggesting that the population of women selected based on their most recent singleton pregnancy may be representative of women with the highest fertility.

Increasing age and the moderation of smoking by number of pregnancies predict impaired fecundity (Table 5). This finding may be related to age and smoking associated endotypic changes in asthma/hay fever phenotypes. During the later reproductive years (>24 years old), the association of allergen skin test positivity with the prevalence of hay fever only increases, regardless of smoking19. In contrast, there is decreased association of allergen skin test positivity with the prevalence of asthma only as well as asthma and hay fever in nonsmokers after age 24 years compared to earlier reproductive years19. These findings suggest greater importance of nonallergic asthma etiologies as contributors to impaired fecundity in women with asthma and hay fever as they age as well as with asthma only.

Examples of nonallergic etiologies of asthma/asthma exacerbations, in addition to smoking, that are also associated with spontaneous pregnancy loss include infectious agents97,98, outdoor air pollution99–101, and indoor air pollution102,103. Indoor air contaminated by phthalates, ubiquitous semi-volatile endocrine-disrupting chemicals e.g., di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate used as plasticizers in polyvinyl chloride plastics and ingredients in personal care products/cosmetics104,105, result in higher phthalate exposure in women106 and women of color107. Phthalate exposure is associated with an increased risk of endometriosis108. Endometriosis also increases the risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss109 and women with asthma also have an increased risk of endometriosis110. The sexually dimorphic increased incidence of nonallergic asthma in young women following puberty111 has been attributed to fluctuations in endogenous sex hormones as menarche, menstrual irregularity, pregnancy, and menopause as well as exogenous sex hormones (oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy) influence asthma exacerbations/remissions112. Phthalates in addition to being studied in association with spontaneous pregnancy loss103 have also been detected in intrafollicular fluid during oocyte retrieval for fertility treatment113. Intrafollicular and serum phthalate levels are associated with alterations in levels of serum reproductive hormones e.g., decreased anti-Mullerian hormone114 as well as follicular ovarian reserve hormones113. Decreased anti-Mullerian hormone is associated with increased risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss115.

The incidence of nonallergic asthma remains significantly higher in women than men throughout their reproductive years (>20 years old), with both higher incidence and prevalence of nonallergic asthma observed in the later reproductive years (>35 years old)116. Nonallergic asthma in young adults is also significantly increased in women and is associated with decreased allergen sensitization and decreased T2 markers consistent with T2-low asthma117. Older age, decreased allergen sensitization, and absence of allergic rhinitis are also associated with more severe asthma118. Nonallergic asthmatics have increased asthma exacerbations during pregnancy119,120. Airway reactivity associated with sputum neutrophilia is increased in asthmatic women during pregnancy119.

Although asthma severity is not associated with increased risk of spontaneous pregnancy losses, uncontrolled asthma (emergency room visits/hospitalization/systemic corticosteroids), especially in women >34 years old is121. IL-8 is a biomarker of uncontrolled asthma and is associated with increased blood122 and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) neutrophils123, oral/parenteral glucocorticoid unresponsiveness122, and reduced pulmonary function122,123. Endotypes of treatment resistant severe asthma include neutrophilic T2-low asthma43,49,124 e.g., T2-low/Th17-low43, T1/Th17125,126 which are associated with subclinical bronchial infection, increased IL-843, lower airway dysbiosis127, and systemic inflammation128.

Immune deviation towards a T2-low asthma endotype in women as they age with asthma and hay fever and with asthma only provides an immunologic rationale for these asthma/hay fever phenotypes being associated with impaired fecundity. Immune deviation away from a T2 endotype129 at the fetal-maternal interface after implantation contributes to spontaneous abortion and recurrent miscarriage130–132. Thus the nonallergic asthma phenotype, asthma only, which includes T2-low endotypes, might be permissive for embryo implantation facilitating fertility in younger women (Fig. 1), but not support gestation (Fig. 3). As there is decreased allergen skin test positivity associated with the prevalence of asthma and hay fever during the later (>24 years old) reproductive years19 and as older age is a significant predictor of impaired fecundity (Table 5), the increased prevalence of nonallergic etiologies, T2-low endotypes, of asthma and hay fever in adult women may account for the increased rate of pregnancy losses in women with asthma and hay fever that is similar to asthma only (Fig. 3).

Severe neutrophilic asthma that skew towards a Th17 mediated immune response is also observed in a subset of asthma patients133,134. An imbalance in the ratio/function of Th17 (increased) with respect to Treg (decreased) has been observed in asthma135,136 including neutrophilic asthma137 as well as in recurrent spontaneous pregnancy loss138.

Immune deviation towards a T2-high endotype at the fetal-maternal interface after implantation contributes to maintaining immune tolerance of the semiallogeneic fetus during normal pregnancy139–141. Thus hay fever only, a T2-high endotype, is consistent with preserved fecundity in women with hay fever only (Fig. 3).

This study demonstrates the epidemiologic differences associated with fertility and impaired fecundity. Limitations of the 1995 NSFG include self-reports of pregnancies and diagnosed medical conditions, both subject to recall bias. The NSFG data do not include contraceptive use prior to each prior pregnancy, medications used, severity of asthma symptoms, adequacy of asthma treatment, tests of pulmonary function, menstrual irregularity, or polycystic ovary syndrome. Influence of age of menarche and endometriosis are not included in this analysis. The 1995 NSFG did not obtain laboratory samples/biomarkers precluding hormonal or endotype assessment.

Within the broad phenotype/endotype categories discussed, there are complex heterogenous subtypes of asthma142 including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap143 as well as subtypes of allergic rhinitis144 that will need to be studied in relation to fertility/fecundity. Although subsequent NSFGs have not included questions pertinent to asthma and hay fever, the estimated prevalence of asthma and hay fever from the 1995 NSFG and the other risk factors associated with fertility and/or fecundity observed in this study are consistent with literature cited subsequent to the 1995 NSFG.

Conclusions

Asthma only is associated with the increased risks of both becoming pregnant and failing to maintain a viable pregnancy. These effects are confounded by increased fertility and pregnancy losses associated with smoking. The 1995 NSFG sharpens the focus on women smokers with asthma only who have both significantly increased fertility and impaired fecundity compared to other smokers. Women who have asthma or smoke require special attention to reproductive health education, family planning, and smoking cessation as well as optimal asthma/medical management145,146 of their high risk pregnancies prenatally and throughout gestation.

Author contributions

P.C.T. conceived the idea, interpreted the data, drafted, and revised the manuscript. E.F. analyzed, interpreted the data, prepared figures and tabes, and drafted the manuscript. R.F.L. interpreted the data, revised and edited the manuscript. K.H. participated in the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NSFG Cycle 5 (1995): Public Use Data Files, Codebooks, and Documentation, [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_cycle5.htm].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Backman H, et al. Increased prevalence of allergic asthma from 1996 to 2006 and further to 2016 — results from three population surveys. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2017;47:1426–1435. doi: 10.1111/cea.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Rossen LM, Fakhouri THI, Simon AE, Kit BK. Contribution of weight status to asthma prevalence racial disparities, 2–19 year olds, 1988–2014. Ann. Epidemiol. 2017;27:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol. Today. 1993;14:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polese B, et al. The endocrine milieu and CD4 T-lymphocyte polarization during pregnancy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2014;5:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez-Varea A, et al. The Maternal Cytokine and Chemokine Profile of Naturally Conceived Gestations Is Mainly Preserved during In Vitro Fertilization and Egg Donation Pregnancies. J Immunol Res. 2015;128616:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/128616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker JA, Mckenzie ANJ. TH2 cell development and function. Nat. Rev Immunol. 2018;18:121–133. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster PS, et al. Modeling TH2 responses and airway inflammation to understand fundamental mechanisms regulating the pathogenesis of asthma. Immunol Rev. 2017;278:20–40. doi: 10.1111/imr.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraro A, Lemanske RF, Hellings PW, Akdis CA, Bieber T. Precision medicine in patients with allergic diseases: Airway diseases and atopic dermatitis — PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;137:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavagnero K, Doherty TA. Cytokine and Lipid Mediator Regulation of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC2s) in Human Allergic Airways Disease. J Cytokine Biol. 2017;2:1–17. doi: 10.4172/2576-3881.1000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly JE, Mosher WD, Duffer APJ, Kinsey SH. Plan and operation of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 1997;1:1–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zegers-Hochschild F, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care. Fertil. Steril. 2017;108:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tata LJ, et al. Fertility Rates in Women with Asthma, Eczema, and Hay Fever: A General Population-based Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1023–1030. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gade EJ, et al. Asthma affects time to pregnancy and fertility: a register-based twin study. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43:1077–1085. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00148713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turkeltaub PC, Cheon J, Friedmann E, Lockey RF. The Influence of Asthma and/or Hay Fever on Pregnancy: Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017;5:1679–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemminki E, Forssas E. Epidemiology of miscarriage and its relation to other reproductive events in Finland. Am J Obs. Gynecol. 1999;181:396–401. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70568-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwell D, Collins J, Coles R. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 1997. Vital Heal. Stat Series. 2002;10:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siroux V., Ballardini N., Soler M., Lupinek C., Boudier A., Pin I., Just J., Nadif R., Anto J. M., Melen E., Valenta R., Wickman M., Bousquet J. The asthma-rhinitis multimorbidity is associated with IgE polysensitization in adolescents and adults. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1447–1458. doi: 10.1111/all.13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gergen PJ, Turkeltaub PC. The association of allergen skin test reactivity and respiratory disease among whites in the US population. Data from the Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1976 to 1980. Arch. Intern. Med. 1991;151:487–492. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400030053009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gartrell NK, Bos HMW, Goldberg NG. Adolescents of the U. S. National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Sexual Orientation, Sexual Behavior, and Sexual Risk Exposure. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:1199–1209. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9692-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turkeltaub PC, Gergen PJ. Prevalence of upper and lower respiratory conditions in the US population by social and environmental factors: data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1976 to 1980 (NHANES II) Ann. Allergy. 1991;67:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pineles BL, Park E, Samet JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179:807–823. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pignataro F, Bonini M, Forgione A, Melandri S, Usmani O. Asthma and gender: the female lung. Pharmacol Res. 2017;119:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalcante MB, Sarno M, Peixoto AB, Júnior EA, Barini R. Obesity and recurrent miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019;45:30–38. doi: 10.1111/jog.13799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ventura S, Mosher W, Curtin S, Abma J, Henshaw S. Trends in Pregnancies and Pregnancy Rates by Outcome: Estimates for the United States, 1976–1996. Vital Heal. Stat. 2000;Series 21:1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abma J, Chandra A, Mosher W, Peterson L, Piccinino L. Fertility, Family Planning, and Women’s Health: New Data From the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Heal. Stat. 1997;Series 23:1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahni S, Talwar A, Khanijo S, Talwar A. Socioeconomic status and its relationship to chronic respiratory disease. Adv Resp Med. 2017;85:97–108. doi: 10.5603/ARM.2017.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin JA, et al. Births: Final Data for 2006. Natl. Vital Stat. Reports. 2009;57:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panaitescu AM, Syngelaki A, Prodan N, Akolekar R, Nicolaides KH. Chronic hypertension and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2017;50:228–235. doi: 10.1002/uog.17493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger H, et al. Diabetes in Pregnancy. J Obs. Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventura SJ, Abma JC, Mosher WD, Henshaw S. Estimated Pregnancy Rates for the United States, 1990–2000: An Update. Natl. Vital Stat. Reports. 2004;52:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gergen PJ, Turkeltaub PC. The association of individual allergen reactivity with respiratory disease: Data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992;90:579–588. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90130-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cayrol C, et al. Environmental allergens induce allergic inflammation through proteolytic maturation of IL-33. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:375–385. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenzel SE. Emergence of Biomolecular Pathways to Define Novel Asthma Phenotypes Type-2 Immunity and Beyond. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:1–4. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0141PS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muehling LM, Lawrence MG, Woodfolk JA. Pathogenic CD4+ T cells in patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;140:1523–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung KF. Asthma phenotyping: a necessity for improved therapeutic precision and new targeted therapies. J Intern. Med. 2016;279:192–204. doi: 10.1111/joim.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodruff PG, et al. T-helper Type 2 – driven Inflammation Defines Major Subphenotypes of Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma - present in most, absent in many. Nat. Rev Immunol. 2015;15:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nri3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guibas GV, Mathioudakis AG, Tsoumani M, Tsabouri S. Relationship of Allergy with Asthma: There Are More Than the Allergy ‘ Eggs’ in the Asthma ‘ Basket’. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oriss TB, et al. IRF5 distinguishes severe asthma in humans and drives Th1 phenotype and airway hyperreactivity in mice. JCI Insight. 2017;2:1–16. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.91019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galeone C, et al. Precision Medicine in Targeted Therapies for Severe Asthma: Is There Any Place for (Omics) Technology? Biomed Res. Int. 2018;23(July 20):1–15. doi: 10.1155/2018/4617565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semprini R, et al. Type 2 biomarkers and prediction of future exacerbations and lung function decline in adult asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018;6:1982–1988.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, et al. Mechanism of T H 2/T H 17-predominant and neutrophilic T H 2/T H 17-low subtypes of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;139:1548–1558.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samitas K, Zervas E, Gaga M. T2-low asthma: current approach to diagnosis and therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23:48–55. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Svenningsen S, Nair P. Asthma endotypes and an Overview of Targeted Therapy for Asthma. Front Med. 2017;4:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agache I, Akdis CA. Endotypes of allergic diseases and asthma: An important step in building blocks for the future of precision medicine. Allergol. Int. 2016;65:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson D. Revisiting Type 2-high and Type 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:161–175. doi: 10.1111/cea.12880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhakta NR, et al. Interferon-Stimulated Gene Expression, Type-2 Inflammation and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:313–324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1070OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung K. Diagnosis and Management of Severe Asthma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:91–99. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dima E, Rovina N, Gerassimou C, Roussos C, Gratziou C. Pulmonary function tests, sputum induction, and bronchial provocation tests: diagnostic tools in the challenge of distinguishing asthma and COPD phenotypes in clinical practice. Int J COPD. 2010;5:287–296. doi: 10.2147/copd.s9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westerhof GA, et al. Predictors of frequent exacerbations in (ex) smoking and never smoking adults with severe asthma. Respir Med. 2016;118:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J. Implantation in eutherians: Which came first, the inflammatory reaction or attachment? PNAS. 2018;115:E1–E2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716675115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffith OW, Chavan AR, Protopapas S, Maziarz J, Romero R. REPLY TO LIU: Inflammation before implantation both in evolution and development. PNAS. 2018;115:E3–E4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1221:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffith OW, Chavan AR, Protopapas S, Maziarz J, Romero R. Embryo implantation evolved from an ancestral inflammatory attachment reaction. PNAS. 2017;114:E6566–E6575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701129114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brighton PJ, et al. Clearance of senescent decidual cells by uterine natural killer cells in cycling human endometrium. Elife. 2017;11:1–23. doi: 10.7554/eLife.31274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chavan AR, Griffith OW, Wagner P. The inflammation paradox in the evolution of mammalian pregnancy: turning a foe into a friend. Curr Opin Gen Devel. 2017;47:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharkey DJ, Tremellen KP, Jasper MJ, Gemzell-danielsson K, Robertson SA. Seminal Fluid Induces Leukocyte Recruitment and Cytokine and Chemokine mRNA Expression in the Human Cervix after Coitus. J Immunol. 2012;188:2445–2454. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song Z, Li Z, Li D, Fang W, Liu H. Seminal plasma induces inflammation in the uterus through the γδ T/IL-17 pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Polese B, et al. Accumulation of IL-17+ Vgamma6+ gammadelta T cells in pregnant mice is not associated with spontaneous abortion. Clin Transl Immunol. 2018;7:e1008. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead A, Grammatoppouos D, Gadsby P. Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy: An Association between Symptoms and Maternal Prostaglandin E2. Gynecol Obs. Invest. 2000;50:149–152. doi: 10.1159/000010314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bustos M, et al. Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy-What’s New? Aut. Neurosci. 2017;202:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y, Wang W, Zhao C, Wang Y, Wu H. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits group 2 innate lymphoid cell activation and allergic airway inflammation Through E-Prostanoid 4-cyclic adenosine Monophosphate signaling. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birring SS, et al. Induced Sputum Inflammatory Mediator Concentrations in Chronic Cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:15–19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1092OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okazaki A, Hara J, Ohkura N, Fujimura M, Sakai T. Role of prostaglandin E 2 in bronchoconstriction-triggered cough response in guinea pigs. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;48:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujimura M, Ogawa H, Nishizawa Y, Nishi K. Comparison of atopic cough with cough variant asthma: is atopic cough a precursor of asthma? Thorax. 2003;58:14–18. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cao C, et al. Proteomic analysis of sputum reveals novel biomarkers for various presentations of asthma. J Transl Med. 2017;15:171–9. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1264-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White S, Nicodemus-Johnson J, Laxman B, Denner D. Elevated levels of soluble humanleukocyte antigen-G in the airways are a marker for a low-inflammatory endotype of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:857–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferreira LMR, Meissner TB, Tilburgs T, Strominger JL. HLA-G: At the Interface of Maternal – Fetal Tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:272–286. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim RY, et al. In flammasomes in COPD and neutrophilic asthma. Thorax. 2015;70:1199–1201. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luetragoon T, Rutqvist LE, Tangvarasittichai O, Usuwanthim K, Lewin N. Interaction among smoking status, single nucleotide polymorphisms, and markers of systemic inflammation in healthy individuals. Immunology. 2017;154:98–103. doi: 10.1111/imm.12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selvarajah S, et al. Multiple Circulating Cytokines Are Coelevated in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;3604842:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2016/3604842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raedler D, Ballenberger N, Klucker E, Bock A. Identification of novel immune phenotypes for allergic and nonallergic childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang P, Diao L, Huang C, Lian R. The pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in peripheral blood of women with recurrent implantation failure. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2015;31:823–826. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bongaarts J. A Framework for Analyzing the Proximate Determinants of Fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1978;4:105–132. doi: 10.2307/1972149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ventura SJ, Mosher WD, Curtin SC, Abma JC. Trends in Pregnancy Rates for the United States, 1976–97: An Update. Natl. Vital Stat. Reports. 2001;49:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chandra, A., Martinez, G., Mosher, W., Abma, J. & Jones, J. Fertility, Family Planning, and Reproductive Health of U. S. Women: Data From the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Heal. Stat. Ser. 23, Programs Collect. Proced. 1–160 (2005). [PubMed]

- 78.Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke A. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20-44 years of age in the United States: Results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) Contraception. 2017;5(Dec):1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Black N, Kung CSJ, Peeters A. For richer, for poorer: the relationship between adolescent obesity and future household economic prosperity. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 2018;111:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frisco M, Weden M. Early Adult Obesity and U.S. Women’s Lifetime Childbearing Experiences. J Marriage Fam. 2014;75:920–932. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson CD, Jones S, Paranjothy S. Reducing low birth weight: prioritizing action to address modifiable risk factors. J Public Heal. 2017;39:122–131. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haar K, et al. Risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in adolescents: results from a representative population- based survey in Germany, 2003–2006. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:1–10. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.34.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Unemo M, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17:e235–e279. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rob F, et al. Concordance of HPV-DNA in cervical dysplasia or genital warts in women and their monogamous long-term male partners. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1662–1670. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Daling J, et al. Human Papillomavirus, Smoking, and Sexual Practices in the Etiology of Anal Cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edelman N, Cassell J, de Visser R, Prah P, Mercer C. Can psychosocial and socio-demographic questions help identify sexual risk among heterosexually-active women of reproductive age? Evidence from Britain’s third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3918-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buck Louis GM, et al. Lifestyle and pregnancy loss in a contemporary cohort of women recruited before conception: The LIFE Study. Fertil. Steril. 2016;106:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rossen LM, Ahrens K, Branum A. Trends in Risk of Pregnancy Loss Among US Women, 1990 – 2011. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018;32:19–29. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chayachinda C, Rekhawasin T. Reproductive outcomes of patients being hospitalised with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Obs. Gynaecol. 2017;37:228–232. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2016.1234439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Trent M, Bass D, Ness R, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, Subsequent STI, and Reproductive Health Outcomes: Findings from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:879–881. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31821f918c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maconochie N, Doyle P, Prior S, Simmons R. Risk factors for first trimester miscarriage — results from a UK-population-based case – control study. BJOG. 2006;114:170–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mosher W, Jones J, Abma J. Nonuse of contraception among women at risk of unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception. 2015;92:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Donnet M, Howie P, Marnie M, Cooper W, Lewis M. Return of Ovarian Function Following Spontaneous Abortion. Obs. Gyne Surv. 1991;46(1):63–65. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stoddard A, Eisenberg DL. Controversies in Family Planning: Timing of Ovulation after Abortion and the Conundrum of Post-Abortion IUD Insertion. Contraception. 2011;84:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]