Abstract

Background:

There are limited data on the characteristics of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and their mothers from the general population in the United States.

Methods:

During the 2012 and 2013 academic years, first-grade children in a large urban Pacific Southwest city were invited to participate in a study to estimate the prevalence of FASD. Children who screened positive on weight, height or head circumference ≤ 25th centile or on parental report of developmental concerns were selected for evaluation, along with a random sample of those who screened negative. These children were examined for dysmorphology and neurobehavior and their mothers or collateral sources were interviewed. Children were classified as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), alcohol related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), or No FASD.

Results:

A total of 854 children were evaluated; 5 FAS, 44 pFAS, 44 ARND, and 761 no FASD. Children with FAS or pFAS were more likely to have dysmorphic features, and 32/49 (65.3%) of those met criteria for neurobehavioral impairment on cognitive measures with or without behavioral deficits. In contrast, 28/44 (63.6%) of children with ARND met criteria on behavioral measures alone. Mothers of FASD children were more likely to recognize pregnancy later, be unmarried, and report other substance use or psychiatric disorders, but did not differ on age, socioeconomic status, education or parity. Mothers of FASD children reported more drinks/drinking day each trimester. The risk of FASD was elevated with increasing number of drinks/drinking day prior to pregnancy recognition, even at the level of 1 drink per day (adjusted odds ratio 3.802, 95% confidence interval 1.634, 8.374).

Conclusion:

Data from this general population sample in a large urban region in the U.S. demonstrate the variability of expression of FASD, and point to risk and protective factors for mothers in this setting.

Keywords: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, prevalence, pregnant women, prenatal alcohol use

INTRODUCTION

In response to the lack of credible national prevalence estimates for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in the United States, the Collaboration on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Prevalence (CoFASP) study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). This study involved an active case ascertainment approach for estimation of the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), alcohol related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) and the combined prevalence of FASD among first-grade children in four different regions of the United States, including one site in the Pacific Southwest. At that site, over two academic years beginning in 2012 and 2013, 4,409 children were invited to participate in the study, and 922 were evaluated for dysmorphology, growth, neurobehavior and prenatal alcohol exposure (May et al., 2018).

The most conservative estimate of the prevalence of FASD in the Pacific Southwest sample, based on the denominator of all eligible children, was 18.8 per 1,000 children in the first year (95% confidence interval [CI] 16.1–21.8), and in the second year, 22.6 per 1,000 children (95% CI 19.5–25.9) (May et al., 2018). Across all four regional sites in that study, the most conservative estimates ranged from 11 per 1,000 to 50 per 1,000. Less conservative prevalence estimates, based on a denominator of only those children who received a comprehensive evaluation, were considerably higher. In the Pacific Southwest site in the first year, they were 90.0 per 1,000 (95% CI 65.9–118.6), and in the second year 84.4 per 1,000 children (95% CI 61.2–112.3). Furthermore, in subsequent sensitivity analyses based on population-based survey data on any alcohol use in pregnancy and race/ethnic group from women in the Pacific Southwest region, the prevalence estimates for FASD ranged from 87.3 per 1,000 (95% CI 63.3 to 115.9) to 82.3 per 1,000 (95% CI 56.9–115.9) (Xu et al., 2019).

As these data provide a cross-sectional snapshot of FASD in a single community, we sought to describe the variability in expression of FASD as well as maternal risk and protective factors for mothers of affected children in a large urban city in the Pacific Southwest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the Study Community

Based on 2015 population estimates, 1,406,630 persons resided in the Pacific Southwest city selected for the study. The majority of residents (58.9%) were self-reported as white non-Hispanic, while 28.8% were Hispanic or Latino (Table 1). The residents had a median household income of $66,116, which was above the U.S. average; however, 15.4% were at the poverty level, also above the U.S. average. Per capita alcohol consumption in the State of California was 2.33 gallons per year in 2009 compared to the U.S. average of 2.30 gallons per year. Among adults in the State, 15.6% reported binge drinking (5 drinks per occasion for men and 4 drinks per occasion for women) compared to the U.S. average of 16.8% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected Characteristics of Pacific Southwest City Compared to the United States

| Descriptor | Pacific Southwest City | United States |

|---|---|---|

| Population (7/2015) (% of U.S.)a | 1,406,630 (0.44%) |

321,418,820 (100%) |

| Population change (%) since 2010a | 8.1% | 4.1% |

| Race/Ethnicity (2010)a | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 58.9% | 63.7% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6.7% | 12.6% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.6% | 0.9% |

| Asian | 15.9% | 4.8% |

| Two or more races | 5.1% | 2.9% |

| Hispanic | 28.8% | 16.3% |

| Foreign born personsa | 26.6% | 13.1% |

| Median age (years)a | 33.6 | 37.2 |

| Median household valuea | $463,000 | $176,700 |

| Education (% of those 25 years or older)a | ||

| High School graduate or higher | 87.3% | 86.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 43.0% | 29.3% |

| Economica | ||

| Per capita income last 12 months (2014 $) | $33,902 | $28,555 |

| Median household income | $66,116 | $53,482 |

| Persons in poverty | 15.4% | 14.8% |

| Health Behaviorb | ||

| Overall state health rank U.S. | 15–19 | Median 25 (Range 1–50) |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| Binge drinkingc State % (US rank)b | 15.6% (21) | 16.8% (25) |

| Excessive drinkingd, State % (US rank)b | 17.2% (22) | 17.4% (Median 25) |

| Excessive drinking, countye | 20.0% | |

| Heavy drinkingf, citye | 5.7% | 16.8% (Mean) |

| State per capita alcohol consumption (2009)g | 2.33 gallons 8.82 liters |

2.30 gallons 8.71 liters |

U.S. Census data (2015)

United Health Foundation, American’s Health Rankings 2015

In past 30 days, 5 or more drinks men, 4 or more women on an occasion

Combination of binge and chronic drinking; heavy drinking

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More than 2 drinks a day for men, more than 1 drink a day womeng

The overall CoFASP study design has been described in detail elsewhere (May et al., 2018). In brief, in the two academic years 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, 29 public and private primary schools in the Pacific Southwest city were selected for participation based on willingness of the school principal to collaborate, diversity of children attending the schools, and an overall enrollment of first-graders sufficient to meet the required pool of approximately 4,000 eligible participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California San Diego and by the local School District.

Sampling Design, Screening and Recruitment

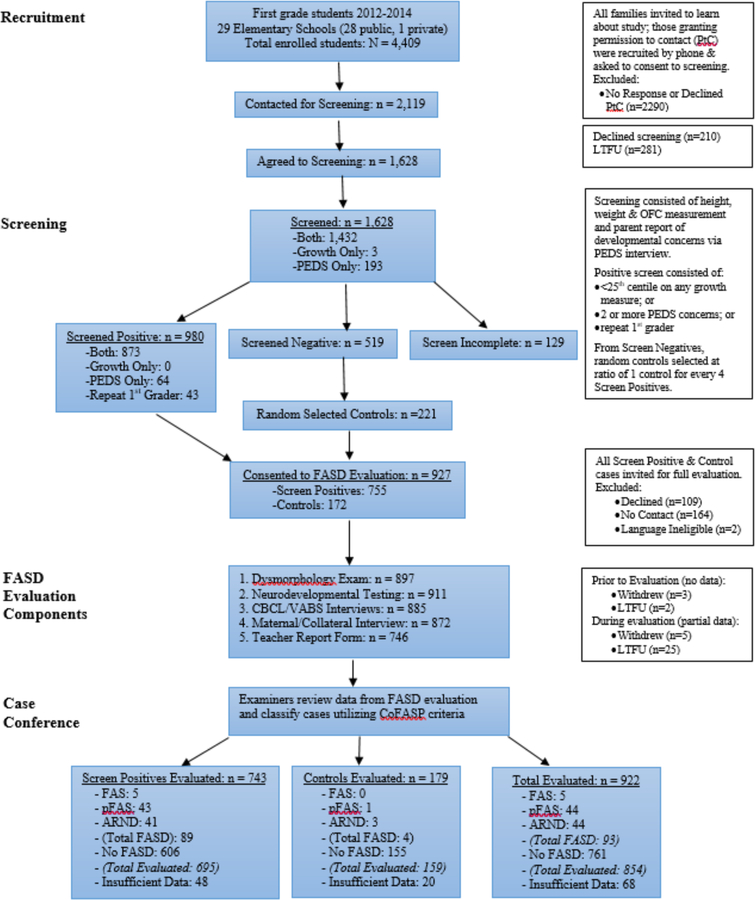

At all participating schools, parents or guardians were asked for permission to be contacted to learn more about the study. Those who agreed to be contacted, and consented for screening of their child, completed a telephone questionnaire on developmental concerns, the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status or PEDS (Woolfenden et al, 2014), and the child was measured for weight, height and head circumference. Those children who screened positive on any growth measurement ≤ 25th centile using standard growth curves, or who had two or more developmental concerns reported on the PEDS, or who were repeating first grade, were invited for a full evaluation. A random sample of children who screened negative on both growth and the PEDS were also invited for a full evaluation. The consort diagram describing the flow of participants for recruitment and evaluation is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sampling Methodology for Prevalence of FASD in a Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

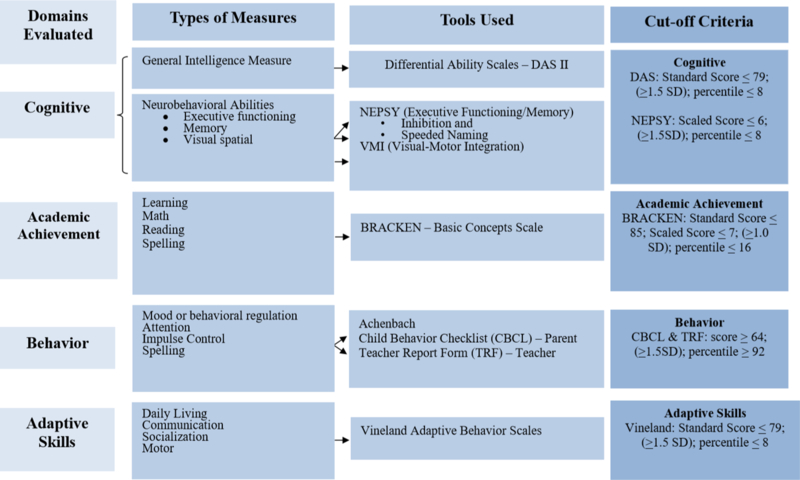

Those children whose parents/guardians provided consent for the full evaluation were assessed for growth and a checklist of minor physical anomalies using a structured face-to-face assessment conducted by trained dysmorphologists/geneticists who were blinded to the child’s prenatal alcohol history or neurobehavioral performance. These children also participated in a study-specific neurobehavioral testing battery conducted in English or Spanish by a trained psychometrist under the supervision of a neuropsychologist, both of whom were blinded to the prenatal alcohol history or dysmorphology examination results for that child. The neurobehavioral testing battery was designed to evaluate domains known to be affected by prenatal alcohol including global intellectual ability, executive functioning, visual spatial, and academic achievement. As part of this battery, parents also completed telephone-administered measures of the child’s behavior and adaptive functioning, and the child’s teacher was also invited to complete a report of child behavior concerns (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CoFASP Cut Off Criteria Set for all Domains: Neurobehavioral Testing Battery

Finally, mothers or collateral reporters also completed a telephone interview in English or Spanish to capture demographic, pregnancy history, comorbidities, substance use information, and history of social or legal problems due to alcohol. The maternal/collateral interview included questions about current alcohol consumption, alcohol use prior to recognition of the index pregnancy, alcohol use after pregnancy recognition and in each subsequent trimester. Alcohol information was collected with sufficient detail to calculate number of standard drinks per day and per drinking day in each time period in pregnancy.

Classification of FASD

Criteria for classification of FASD in the CoFASP study were selected by consensus of the CoFASP Steering Committee based on being generally consistent with established diagnostic schema and on feasibility of application in a one-time assessment of a cross-sectional sample of children in the first-grade age range. Of note, the CoFASP criteria established cut-offs for neurobehavioral impairment in the presence of sufficient physical features to classify a child as FAS or pFAS with or without confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure; whereas the criteria used to classify a child as ARND established more restrictive neurobehavioral cut-offs and required confirmed alcohol exposure at a pre-specified level (Hoyme et al., 2016).

The criteria for “risky” alcohol exposure was established by consensus, and required documentation of maternal or collateral report of three or more standard drinks per occasion on at least two occasions in pregnancy, or six or more standard drinks per week for at least two weeks in pregnancy, or report of social or legal problems related to alcohol in the period of pregnancy.

Case Conferences for FASD Classification

Classification for each child enrolled in the study was made based on available information reviewed in multidisciplinary case conferences involving the study investigators who represented dysmorphology, neuropsychology and epidemiology. The findings for each child were reviewed along with digital photo images of the child’s face (frontal and profile views). Criteria for classification as FAS, pFAS, ARND or No FASD were based on the pre-specified criteria as outlined in Hoyme et al 2016. Validation of these classifications was conducted by de-identified exchange of data with the other CoFASP sites’ research team to ensure that criteria were consistently being applied.

Statistical Analysis

Variables of interest were summarized within each of the FASD classification groups: FAS, pFAS, ARND, and No FASD. Children for whom there was insufficient data to classify as FASD or not were excluded. For categorical variables, the count and percentage in each category of the variable was reported. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation of the variables were reported. The distributions of each categorical variable across the FASD groups were compared using chi square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Correlation analyses were computed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Logistic regression was used to characterize the association between FASD and number of drinks per drinking day while controlling for other substance use. A p-value of 0.05 was used as a cut-off to evaluate associations. However, to account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was also applied to the significance threshold to maintain a familywise error rate of 0.05. Analyses were carried out using R version 3.4.1. Partial correlation values and tests were computed using the ppcor package using Dunnett’s correction for pairwise comparisons (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Child Characteristics

Eligible participants in both academic years combined consisted of 4,409 children enrolled in the normal first grade classes at the participating schools. After screening and evaluation, a total of 854 children were available for this analysis. As shown in Figure 1, 5 children met criteria for FAS, 44 met criteria for pFAS, 44 met criteria for ARND and 761 were classified as No FASD. Race/ethnic categories were based on maternal self-report, and mothers/children were classified as Hispanic (of any race) and non-Hispanic, by race. There were differences across groups in the race/ethnic distribution (p = 0.014); however, all race/ethnic categories were represented in those children with FASD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of race/ethnicity by fetal alcohol spectrum disorders classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity – n (%) |

0.014* |

|||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (20.0) | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.3) | 90 (11.9) | 95 (11.2) | |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.1) | 20 (2.6) | 25 (3.0) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (80.0) | 25 (61.0) | 18 (40.9) | 442 (58.4) | 489 (57.7) | |

| Other/Multiracial | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.1) | 21 (2.8) | 25 (3.0) | |

| White | 0 (0.0) | 12 (29.3) | 17 (38.6) | 184 (24.3) | 213 (25.1) | |

P-values below 0.05 are indicated by an *

As shown in Table 3, among pFAS and ARND cases, male children were more likely to be classified as FASD, but the four group comparison did not meet the Bonferroni-corrected p-value cutoff of 0.0028. There were significant differences across the four groups in current height, weight, and body mass index centile, and in the presence or absence of the classical facial features that are part of the diagnostic criteria, including smooth philtrum, thin vermilion border of the upper lip and shorter palpebral fissure length. As expected, these findings were more common in those with FAS and pFAS. However, other minor anomalies were also more prevalent in children with FASD, including ptsosis and strabismus, particularly among those with FAS and pFAS. In addition, the distribution of several other minor anomalies varied across the groups but did not meet the criteria for p-valued corrected significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Selected characteristics, growth, and dysmorphic features by FASD classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| Child Characteristica | FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – n (%) | 0.008 | |||||

| Male | 1 (20.0) | 28 (63.6) | 31 (70.5) | 384 (50.5) | 444 (52.0) | |

| Female | 4 (80.0) | 16 (36.4) | 13 (29.5) | 377 (49.5) | 410 (48.0) | |

| Age – months, mean (SD) | 85.2 (8.2) | 85.9 (6.9) | 85.4 (8.1) | 85.4 (7.0) | 85.4 (7.0) | 0.968 |

| Preterm Birth – n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 7 (17.1) | 6 (13.6) | 76 (10.1) | 92 (10.9) | 0.010 |

| Birth Weight - gm (SD) | 2177.2 (983.4) | 2791.3 (754.3) | 3186.2 (612.7) | 3095.8 (614.5) | 3080.1 (630.8) | <0.001* |

| Current Height Centile (SD) | 13.0 (14.9) | 33.8 (27.0) | 54.6 (26.4) | 48.0 (28.5) | 47.4 (28.6) | <0.001* |

| Current Weight Centile (SD) | 7.6 (4.7) | 33.5 (29.9) | 58.8 (27.3) | 53.3 (30.1) | 52.3 (30.4) | <0.001* |

| Current BMI Centile (SD) | 21.2 (20.8) | 42.4 (30.6) | 60.3 (32.3) | 57.5 (30.9) | 56.7 (31.2) | <0.001* |

| Current OFC Centile (SD) | 4.8 (3.3) | 30.9 (28.7) | 57.4 (31.2) | 48.6 (29.9) | 47.9 (30.3) | <0.001* |

| Left PFL Centile (SD) | 7.2 (5.5) | 14.1 (12.8) | 28.9 (15.5) | 26.5 (15.9) | 25.9 (16.0) | <0.001* |

| Right PFL Centile (SD) | 7.2 (5.5) | 14.6 (12.8) | 29.9 (14.8) | 26.9 (15.7) | 26.3 (15.8) | <0.001* |

| Smooth Philtrum – n (%) | 5 (100.0) | 38 (86.4) | 1 (2.3) | 143 (19.0) | 187 (22.2) | <0.001* |

| Thin Vermilion – n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 37 (84.1) | 5 (11.6) | 123 (16.4) | 168 (19.9) | <0.001* |

| IPD Centile (SD) | 39.2 (24.4) | 48.5 (30.2) | 59.8 (26.6) | 57.5 (25.4) | 57.1 (25.8) | 0.048 |

| OCD Centile (SD) | 11.4 (8.8) | 27.5 (24.0) | 36.0 (21.7) | 33.6 (21.1) | 33.3 (21.4) | 0.026 |

| Maxillary Arc - cm (SD) | 23.6 (1.3) | 24.8 (1.1) | 25.3 (1.3) | 25.1 (1.2) | 25.1 (1.2) | 0.010 |

| Mandibular Arc - cm (SD) | 24.4 (2.1) | 26.0 (1.2) | 26.5 (1.4) | 26.3 (1.3) | 26.2 (1.4) | 0.006 |

| Ptosis – n (%) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (2.3) | 23 (2.8) | <0.001* |

| Strabismus – n (%) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 7 (0.9) | 12 (1.4) | <0.001* |

| Low set ears – n (%) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 15 (2.1) | 18 (2.2) | 0.036 |

| Single transverse palmar crease – n (%) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.3) | 15 (2.0) | 19 (2.3) | 0.008 |

| Hypoplastic thenar crease – n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0.006 |

| Decreased pronation/supination – n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (9.5) | 0 | 21 (2.8) | 26 (3.1) | 0.017 |

| Heart murmur – n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (2.3) | 14 (1.9) | 18 (2.2) | 0.055 |

| Heart defect – n (%) | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.023 |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; OFC = occipital frontal diameter; PFL = palpebral fissure length; IPD = interpupillary distance; OCD = outer canthal distance

Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is 0.0028; p-values below this cut-off are indicated by an *

Child Cognitive and Behavioral Performance

Among children with FAS or pFAS, 32/49 (65.3%) met criteria for neurobehavioral impairment on cognitive measures, with or without behavioral deficits. In contrast, 28/44 (63.6%) of children with ARND met criteria for neurobehavioral impairment on behavioral measures only (Table 4). Comparing mean scores across groups in the intellectual, executive functioning, learning and visual spatial domains, only the spatial cluster percentile, the speeded naming combined scaled score, and the visuomotor combined scale score differed across groups (p’s<0.05), although none of these comparisons met the stricter cut-off for multiple testing.

Table 4.

Selected neurobehavioral domains and child testing results by FASD classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| Criteria Met for Neurobehavior – n (%) | FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualified for FASD on Cognitive with/without Behavior | 3 (60.0) | 29 (65.9) | 16 (36.4) | -- | 48 (51.6) | 0.015* |

| Qualified for FASD on Behavior Alone | 2 (40.0) | 15 (34.1) | 28 (63.6) | -- | 45 (48.4) | 0.015* |

| Domain and Measure – mean (SD)a | FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pc |

| Intellectual | ||||||

| General Cognitive Abilities Percentile | 30.5 (31.8) | 39.7 (26.0) | 44.0 (27.8) | 49.0 (25.9) | 48.1 (26.1) | 0.175 |

| Verbal Cluster Percentile | 46.5 (27.6) | 42.0 (28.5) | 46.7 (32.3) | 48.2 (29.5) | 47.8 (29.5) | 0.759 |

| Nonverbal Reasoning Cluster Percentile | 22.0 (14.1) | 39.6 (24.6) | 41.3 (23.0) | 46.4 (23.4) | 45.6 (23.5) | 0.164 |

| Spatial Cluster Percentile | 35.0 (43.8) | 41.3 (24.2) | 46.2 (30.5) | 53.1 (23.3) | 52.0 (24.0) | 0.030 |

| Executive Functioning | ||||||

| INN (Naming) Combined Scaled Score | 9.4 (2.3) | 9.3 (3.7) | 8.7 (4.2) | 9.4 (3.6) | 9.3 (3.6) | 0.690 |

| INN vs. INI Contrast Scaled Score | 8.4 (5.1) | 8.8 (3.5) | 8.9 (3.6) | 9.6 (3.3) | 9.5 (3.4) | 0.269 |

| INI (Inhibition) Combined Scaled Score | 8.2 (4.8) | 8.7 (3.7) | 8.4 (3.7) | 9.4 (3.5) | 9.3 (3.6) | 0.199 |

| INS (Switching) Combined Scaled Score | 10.5 (3.5) | 8.6 (3.0) | 8.9 (3.3) | 9.1 (3.2) | 9.0 (3.2) | 0.831 |

| Speeded Naming Combined Scaled Score | 10.6 (4.7) | 7.6 (3.0) | 8.7 (3.3) | 8.9 (3.2) | 8.8 (3.2) | 0.047 |

| Learning | ||||||

| BBCS School Readiness Composite Scaled Score | 11.0 (3.7) | 10.1 (3.0) | 11.2 (2.9) | 10.6 (3.1) | 10.6 (3.1) | 0.442 |

| BBCS Readiness Composite Standard Score | 105.6 (18.1) | 100.2 (15.2) | 105.7 (14.9) | 102.9 (15.2) | 102.9 (15.2) | 0.436 |

| Visual Spatial | ||||||

| VMI Standard Score | 90.4 (9.6) | 90.6 (8.9) | 91.8 (8.0) | 93.4 (8.1) | 93.1 (8.1) | 0.082 |

| Visuomotor Precision Combined scaled score | 11.6 (5.0) | 8.9 (3.2) | 9.1 (3.5) | 10.0 n(3.3) | 9.9 (3.3) | 0.044 |

| Mood Regulation | ||||||

| CBCL Anxious/Depressed t-score | 56.2 (8.8) | 57.6 (7.2) | 60.6 (9.4) | 56.3 (7.1) | 56.6 (7.3) | 0.001 |

| TRF Anxious/Depressed t-score | 55.4 (6.2) | 53.9 (7.2) | 54.8 (6.1) | 52.6 (5.5) | 52.8 (5.6) | 0.053 |

| CBCL Withdrawn/Depressed t-score | 55.2 (6.4) | 58.3 (7.6) | 59.5 (8.7) | 56.0 (7.2) | 56.3 (7.4) | 0.004 |

| TRF Withdrawn/Depressed t-score | 52.0 (3.1) | 53.1 (4.6) | 55.4 (6.4) | 53.2 (5.8) | 53.3 (5.8) | 0.159 |

| CBCL Internalizing Problems t-score | 50.0 (14.3) | 56.5 (8.3) | 58.2 (9.8) | 53.1 (9.6) | 53.5 (9.6) | <0.001* |

| TRF Internalizing Problems t-score | 49.4 (11.4) | 47.4 (11.0) | 51.2 (10.6) | 46.1 (9.5) | 46.5 (9.7) | 0.017 |

| CBCL Externalizing Problems t-score | 51.6 (15.3) | 56.3 (9.9) | 64.5 (8.8) | 52.7 (10.3) | 53.5 (10.5) | <0.001* |

| TRF Externalizing Problems t-score | 54.8 (9.0) | 48.4 (9.6) | 56.4 (9.7) | 48.6 (8.7) | 49.0 (9.0) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Affective Problems t-score | 56.4 (6.8) | 57.5 (7.4) | 59.0 (8.4) | 55.7 (6.8) | 56.0 (7.0) | 0.008 |

| TRF Affective Problems t-score | 53.0 (6.7) | 54.1 (6.1) | 56.9 (6.8) | 52.8 (5.7) | 53.1 (5.8) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Anxiety Problems t-score | 56.8 (7.8) | 58.7 (8.0) | 60.4 (8.5) | 56.5 (7.1) | 56.8 (7.3) | 0.002 |

| TRF Anxiety Problems t-score | 57.2 (11.0) | 53.9 (6.4) | 55.6 (7.9) | 52.8 (5.6) | 53.1 (5.8) | 0.011 |

| Attention | ||||||

| CBCL Attention Problems t-score | 61.4 (10.1) | 59.2 (9.9) | 65.7 (10.2) | 56.8 (8.1) | 57.4 (8.6) | <0.001* |

| TRF Attention Problems t-score | 59.6 (6.9) | 55.0 (7.0) | 58.9 (7.7) | 53.6 (6.1) | 54.0 (6.3) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems t-score | 76.4 (18.4) | 73.7 (18.7) | 87.6 (13.7) | 69.1 (17.8) | 70.3 (18.2) | <0.001* |

| TRF Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems t-score | 61.6 (7.9) | 55.3 (7.0) | 59.3 (7.2) | 53.8 (6.0) | 54.2 (6.3) | <0.001* |

| Impulse Control | ||||||

| CBCL Rule-breaking Behavior t-score | 55.4 (7.0) | 56.2 (6.4) | 61.3 (8.4) | 55.1 (5.9) | 55.4 (6.3) | <0.001* |

| TRF Rule-breaking Behavior t-score | 52.8 (4.1) | 52.9 (5.6) | 57.1 (6.9) | 52.8 (5.3) | 53.0 (5.5) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Aggressive Behavior t-score | 57.6 (10.4) | 59.0 (8.8) | 66.3 (10.0) | 56.2 (7.9) | 56.9 (8.4) | <0.001* |

| TRF Aggressive Behavior t-score | 57.2 (5.9) | 53.9 (6.4) | 58.2 (7.9) | 53.1 (6.4) | 53.5 (6.6) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Oppositional Defiant Problems t-score | 58.4 (8.6) | 59.3 (8.3) | 66.4 (8.7) | 56.5 (7.6) | 57.2 (8.0) | <0.001* |

| TRF Oppositional Defiant Problems t-score | 57.8 (6.0) | 53.4 (5.9) | 57.0 (7.2) | 52.8 (5.4) | 53.1 (5.6) | <0.001* |

| CBCL Conduct Problems t-score | 56.8 (8.7) | 56.4 (7.3) | 62.8 (9.7) | 55.5 (6.7) | 55.9 (7.1) | <0.001* |

| TRF Conduct Problems t-score | 53.0 (4.5) | 52.9 (6.1) | 57.8 (8.6) | 52.8 (5.9) | 53.1 (6.2) | <0.001* |

| Adaptive Behavior | ||||||

| Vineland (Parent) VABS Communication Standard Score | 105.8 (25.7) | 97.5 (14.1) | 92.8 (12.5) | 101.1 (13.2) | 100.5 (13.4) | <0.001* |

| Vineland (Parent) VABS Daily Living Skills Standard Score | 107.0 (13.6) | 95.9 (10.5) | 97.8 (11.3) | 100.7 (10.6) | 100.3 (10.7) | 0.005 |

| Vineland (Parent) VABS Socialization Standard Score | 102.4 (17.0) | 97.8 (10.4) | 92.9 (9.2) | 100.4 (11.0) | 99.9 (11.1) | <0.001* |

Abbreviations: BBCS = Bracken Basic Concept Scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; TRF = Teacher Report Form; VABS = Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale

p-values below 0.05 are indicated by an *

Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is 0.0012; p-values below this cut-off are indicated by an *

In contrast, in the behavioral domains of mood regulation, attention, and impulse control, mean scores on most measures differed across groups. Both the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Teacher Report Form (TRF) mean scores for externalizing and anxiety problems, as well as the CBCL for internalizing problems and the TRF for affective problems differed significantly across groups (p’s<0.001). All impulse control measures on the CBCL and the TRF differed significantly across groups, particularly among children with ARND (p’s<0.001) (Table 4).

Maternal Alcohol and Other Substance Use

Among the 49 children with FAS or pFAS, 24 (49.0%) of their mothers reported consuming alcohol prior to pregnancy recognition. As risky alcohol exposure was a required criterion for ARND, 100% of the 44 mothers of those children reported consuming alcohol before recognition of pregnancy in contrast to 21.4% of the No FASD group (p<0.001) (Table 5). Any drinking in the period after pregnancy recognition or in the 3rd trimester, as well as the frequency of drinking days before pregnancy recognition and in the 2nd trimester, differed significantly across groups (p’s<0.001). Comorbid use of other substances in pregnancy was also more common in the FASD groups, particularly ARND. These differences were found for any drug use, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and prescription drug abuse (p’s<0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Maternal alcohol and other substance use by FASD classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| Substance Use – n (%) or mean (SD)a | FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drank BPR | 2 (40.0) | 22 (57.9) | 31 (100.0) | 154 (21.4) | 209 (26.4) | <0.001* |

| Drinks/usual drinking day BPR | 3.0 (0.0) | 2.8 (2.1) | 3.1 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.7) | 0.023 |

| Frequency drinking days BPR | <0.001* | |||||

| Every day or almost every day | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | 6 (19.4) | 9 (5.8) | 18 (8.6) | |

| 3–4 times/week | 0 (0.0) | 5 (22.7) | 8 (25.8) | 11 (7.1) | 24 (11.5) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 0 (0.0) | 7 (31.8) | 7 (22.6) | 44 (28.6) | 58 (27.8) | |

| 2–3 times/month | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.1) | 9 (29.0) | 18 (11.7) | 29 (13.9) | |

| 1 times/month or less | 2 (100.0) | 5 (22.7) | 1 (3.2) | 72 (46.8) | 80 (38.3) | |

| Had days drank more BPR | 0 (0.0) | 4 (18.2) | 11 (35.5) | 23 (14.9) | 38 (18.2) | 0.072 |

| Drank APR 1st Trimester | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.9) | 10 (27.0) | 21 (2.9) | 34 (4.2) | <0.001* |

| Drinks/usual drinking day APR 1st Trimester | - | 1.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (3.1) | 1.9 (2.5) | 2.3 (2.7) | 0.228 |

| Frequency drinking days APR 1st Trimester | 0.004 | |||||

| Every day or almost every day | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (58.3) | 2 (9.5) | 9 (25.0) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (28.6) | 9 (25.0) | |

| 2–3 times/month | 0 (−) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (8.3) | |

| 1 times/month or less | 0 (−) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (8.3) | 12 (57.1) | 15 (41.7) | |

| Drank 2nd Trimester | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.9) | 8 (22.2) | 38 (5.2) | 49 (6.1) | 0.004 |

| Drinks/usual drinking day 2nd Trimester | - | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.9) | 0.008 |

| Frequency drinking days 2nd Trimester | <0.001* | |||||

| Every day or almost every day | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (2.6) | 6 (12.0) | |

| 3–4 times/week | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 0 (−) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (13.2) | 7 (14.0) | |

| 2–3 times/month | 0 (−) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (10.0) | |

| 1 times/month or less | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 30 (78.9) | 31 (62.0) | |

| Drank 3rd Trimester | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) | 10 (27.8) | 44 (6.1) | 58 (7.2) | <0.001* |

| Drinks/usual drinking day 3rd Trimester | - | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.6) | <0.001* |

| Frequency drinking days 3rd Trimester | 0.005 | |||||

| Every day or almost every day | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (10.0) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 0 (−) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (9.1) | 5 (8.3) | |

| 2–3 times/month | 0 (−) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (9.1) | 7 (11.7) | |

| 1 times/month or less | 0 (−) | 3 (75.0) | 4 (33.3) | 35 (79.5) | 42 (70.0) | |

| Drank in past 30 days | 1 (20.0) | 19 (50.0) | 19 (61.3) | 304 (42.2) | 343 (43.2) | 0.103 |

| Max drinks/24 hrs in past 30 days | 2.0 (−) | 2.1 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.3) | 0.143 |

| Other substances used in pregnancy | ||||||

| Tobacco | 0 (0.0) | 8 (20.0) | 20 (48.8) | 52 (7.1) | 80 (9.7) | <0.001* |

| Any Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.3) | 17 (39.5) | 30 (4.0) | 51 (6.1) | <0.001* |

| Marijuana | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 11 (27.5) | 24 (3.2) | 37 (4.5) | <0.001* |

| Heroin | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.005 |

| Cocaine/Crack | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (16.7) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (1.0) | <0.001* |

| Methamphetamine | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.3) | 9 (23.1) | 7 (0.9) | 20 (2.4) | <0.001* |

| Club Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Hallucinogens | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Inhalants | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Prescription Medications | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | <0.001* |

| Anabolic Steroids | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1.000 |

| Other Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.051 |

| Other Substances Used Lifetime | ||||||

| Any Drugs | 1 (20.0) | 23 (63.9) | 24 (77.4) | 249 (34.6) | 297 (37.5) | <0.001* |

| Marijuana | 1 (20.0) | 21 (58.3) | 24 (77.4) | 236 (32.8) | 282 (35.6) | <0.001* |

| Heroin | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 0.016 |

| Cocaine/Crack | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.9) | 10 (32.3) | 57 (7.9) | 72 (9.1) | <0.001* |

| Methamphetamine | 0 (0.0) | 7 (19.4) | 11 (35.5) | 41 (5.7) | 59 (7.5) | <0.001* |

| Club Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.1) | 8 (25.8) | 60 (8.3) | 72 (9.1) | 0.021 |

| Hallucinogens | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.9) | 7 (23.3) | 62 (8.6) | 74 (9.4) | 0.043 |

| Inhalants | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.3) | 3 (10.0) | 18 (2.5) | 24 (3.0) | 0.030 |

| Prescription Medications | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (3.3) | 12 (1.7) | 15 (1.9) | 0.205 |

| Anabolic Steroids | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1.000 |

| Other Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 0.136 |

Abbreviations: BPR = Before pregnancy recognition; APR = after pregnancy recognition; (−) indicates missing value

Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is 0.0013; p-values below this cut-off are indicated by a *

Maternal Demographic and Health Risk Factors

Demographic characteristics and pregnancy history including maternal age, paternal age, socioeconomic status as measured by household income, maternal educational attainment, gravidity, parity, previous number of spontaneous abortions or stillbirths, birth order of the index child and maternal body size did not differ across groups (Table 6). However, marital status did, with the mothers in the FASD groups less likely to be married (p<0.001). Particularly in the ARND group, pregnancy tended to be recognized on average 1–2 weeks later in gestation. Mothers of children in the FASD groups were more likely to have reported any lifetime diagnosis of a psychiatric condition, particularly in the ARND group (p = 0.004) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Maternal demographic and health characteristics by FASD classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| Characteristica | FAS | pFAS | ARND | No FASD | Overall | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery | 31.7 (4.4) | 29.7 (5.8) | 29.5 (6.3) | 29.2 (6.3) | 29.2 (6.2) | 0.773 |

| Maternal height (cm) – current | 156.2 (6.6) | 160.1 (8.4) | 162.8 (6.1) | 160.4 (8.5) | 160.5 (8.4) | 0.279 |

| Maternal weight (kg) – current | 61.2 (8.0) | 70.9 (13.8) | 71.8 (19.7) | 71.3 (16.6) | 71.3 (16.5) | 0.593 |

| Maternal BMI – current | 25.0 (1.9) | 27.9 (5.8) | 26.9 (6.9) | 27.8 (6.5) | 27.8 (6.4) | 0.685 |

| Maternal weight (kg) - before pregnancy | 58.4 (10.0) | 63.9 (12.5) | 64.2 (13.4) | 63.4 (13.4) | 63.5 (13.3) | 0.839 |

| Asthma – lifetime | 0.817 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 4 (10.5) | 4 (12.9) | 90 (12.5) | 99 (12.5) | |

| No | 4 (80.0) | 34 (89.5) | 27 (87.1) | 630 (87.5) | 695 (87.5) | |

| Stomach Ulcers - lifetime | 0.069 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 3 (7.9) | 3 (9.7) | 31 (4.3) | 38 (4.8) | |

| No | 4 (80.0) | 35 (92.1) | 28 (90.3) | 687 (95.7) | 754 (95.2) | |

| Neurological Conditions – lifetime | 0.455 | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 47 (6.5) | 49 (6.2) | |

| No | 5 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 29 (93.5) | 673 (93.5) | 745 (93.8) | |

| Liver Problems - lifetime | 0.051 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (6.7) | 17 (2.4) | 21 (2.7) | |

| No | 4 (80.0) | 36 (97.3) | 28 (93.3) | 703 (97.6) | 771 (97.3) | |

| Psychiatric Conditions - lifetime | 0.004 | |||||

| Yes | 2 (40.0) | 9 (23.7) | 16 (51.6) | 164 (22.7) | 191 (24.0) | |

| No | 3 (60.0) | 29 (76.3) | 15 (48.4) | 557 (77.3) | 604 (76.0) | |

| Gravidity | 4.0 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.7) | 3.4 (1.7) | 0.372 |

| Parity | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.2) | 0.754 |

| Previous number miscarriages | 1.0 (1.2) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.402 |

| Previous number elective abortions | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.002* |

| Previous number stillbirths | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.721 |

| Birth order index child | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.2 (0.9) | 1.7 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 0.231 |

| Weeks’ gestation at pregnancy recognition | 3.8 (1.5) | 6.4 (3.9) | 7.8 (5.7) | 6.0 (3.5) | 6.0 (3.6) | 0.023 |

| Vitamins/supplements in pregnancy | 0.078 | |||||

| Yes | 5 (100.0) | 38 (95.0) | 32 (86.5) | 714 (95.8) | 789 (95.4) | |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.0) | 5 (13.5) | 31 (4.2) | 38 (4.6) | |

| First prenatal visit | 0.057 | |||||

| 0–3 months | 5 (100.0) | 34 (89.5) | 29 (93.5) | 679 (95.0) | 747 (94.7) | |

| 4–6 months | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.9) | 1 (3.2) | 34 (4.8) | 38 (4.8) | |

| 7–9 months | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | |

| At delivery | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Medical problems in pregnancy | 0.261 | |||||

| Yes | 2 (40.0) | 25 (62.5) | 23 (63.9) | 381 (51.7) | 431 (52.7) | |

| No | 3 (60.0) | 15 (37.5) | 13 (36.1) | 356 (48.3) | 387 (47.3) | |

| Accidents in pregnancy | 0.647 | |||||

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (13.5) | 83 (11.1) | 94 (11.3) | |

| No | 4 (80.0) | 35 (87.5) | 32 (86.5) | 666 (88.9) | 737 (88.7) | |

| Postpartum depression | 0.110 | |||||

| Yes | 3 (60.0) | 7 (18.4) | 11 (33.3) | 173 (23.4) | 194 (23.8) | |

| No | 2 (40.0) | 31 (81.6) | 22 (66.7) | 567 (76.6) | 622 (76.2) | |

| Gestational age at delivery | 35.6 (4.3) | 38.0 (3.2) | 39.1 (1.9) | 39.0 (2.3) | 38.9 (2.4) | <0.001* |

| Father of index child’s age | 37.0 (4.8) | 31.2 (7.5) | 29.0 (7.0) | 31.0 (6.8) | 31.0 (6.8) | 0.084 |

| Maternal Education | 0.494 | |||||

| No formal schooling | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.0) | 8 (1.0) | |

| 8th grade or less | 1 (20.0) | 6 (15.8) | 2 (6.5) | 98 (13.6) | 107 (13.5) | |

| Some high school | 0 (0.0) | 8 (21.1) | 2 (6.5) | 106 (14.7) | 116 (14.6) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 2 (40.0) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (6.5) | 115 (16.0) | 124 (15.6) | |

| Some college/2 year degree | 2 (40.0) | 6 (15.8) | 12 (38.7) | 156 (21.7) | 176 (22.2) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.8) | 9 (29.0) | 4 (12.9) | 147 (18.5) | |

| Some graduate school | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.9) | 14 (1.8) | |

| Graduate/professional school | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (12.9) | 92 (12.8) | 102 (12.8) | |

| Household income in pregnancy | 0.451 | |||||

| $0–10k | 0 (0.0) | 5 (14.3) | 1 (3.3) | 33 (5.2) | 39 (5.6) | |

| $10–15k | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.4) | 4 (13.3) | 54 (8.5) | 62 (8.9) | |

| $15–20k | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (3.3) | 63 (10.0) | 68 (9.7) | |

| $20–25k | 0 (0.0) | 5 (14.3) | 1 (3.3) | 66 (10.4) | 72 (10.3) | |

| $25–35k | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (16.7) | 84 (13.3) | 91 (13.0) | |

| $35–50k | 1 | 2 (5.7) | 3 (10.0) | 84 (13.3) | 90 (12.9) | |

| $50–75k | 1 | 4 (11.4) | 2 (6.7) | 88 (13.9) | 95 (13.6) | |

| $75k or more | 1 | 9 (25.7) | 13 (43.3) | 160 (25.3) | 183 (26.1) | |

| Household Income – current | 0.324 | |||||

| $0–10k | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.5) | 1 (3.3) | 28 (4.1) | 34 (4.5) | |

| $10–15k | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.5) | 2 (6.7) | 59 (8.7) | 66 (8.8) | |

| $15–20k | 2 (40.0) | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | 72 (10.6) | 78 (10.4) | |

| $20–25k | 1 (20.0) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (10.0) | 76 (11.2) | 83 (11.1) | |

| $25–35k | 1 (20.0) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (6.7) | 89 (13.1) | 95 (12.7) | |

| $35–50k | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.1) | 6 (20.0) | 78 (11.5) | 87 (11.6) | |

| $50–75k | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (13.3) | 78 (11.5) | 86 (11.5) | |

| $75k or more | 1 (20.0) | 10 (27.0) | 12 (40.0) | 198 (29.2) | 221 (29.5) | |

| Marital Status – current | <0.001* | |||||

| Married | 1 (20.0) | 21 (55.3) | 17 (54.8) | 451 (62.6) | 490 (61.7) | |

| Unmarried/living with partner | 1 (20.0) | 3 (7.9) | 4 (12.9) | 102 (14.2) | 110 (13.9) | |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 8 (1.1) | 9 (1.1) | |

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 6 (19.4) | 58 (8.1) | 65 (8.2) | |

| Separated | 1 (20.0) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (6.5) | 42 (5.8) | 46 (5.8) | |

| Single/never married | 2 (40.0) | 12 (31.6) | 1 (3.2) | 59 (8.2) | 74 (9.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is 0.0018; p-values below this level are indicated by a *

The FAS group had missing values for some outcomes, this is denoted by a ‘-’ in place of the mean

Correlation Between Selected Child Performance Measures and Timing and Dose of Maternal Alcohol Consumption

Representative measures of intellectual ability, executive functioning, and behavior were examined in association with maternal drinking behaviors, including timing of exposure and drinks per drinking day, using partial Spearman correlation coefficients adjusted for tobacco and other drug use (Table 7). The Global Cognitive Abilities score was associated with drinking and number of drinks per drinking day prior to pregnancy recognition and in the 3rd trimester, at p-values <0.05. The NEPSY inhibition INN vs. INI contrast measure was only associated with drinking prior to pregnancy recognition, and the TRF Rule Breaking measure was associated only with any drinking and drinks per drinking day prior to pregnancy recognition (p’s<0.05). Any FASD classification vs. No FASD was significantly associated with any drinking and drinks per day prior to pregnancy recognition (p’s<0.001), but was also associated with drinking after pregnancy recognition and 3rd trimester drinking (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation between child performance measures and reported timing and dose of maternal alcohol consumption, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combined

| Pregnancy Recognition (weeks) | Drank BPR | Drinks/DD BPR | Drank 1st Trimester APR | Drinks/DD 1st Trimester APR | Drank 2nd Trimester | Drinks/DD 2nd Trimester | Drank 3rd Trimester | Drinks/DD 3rd Trimester | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Cognitive Abilities | |||||||||

| Partial r | −0.068 | 0.122 | 0.106 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.113 | 0.118 |

| p-value | 0.161 | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.643 | 0.658 | 0.811 | 0.765 | 0.019 | 0.014 |

| N | 431 | 431 | 431 | 436 | 436 | 436 | 435 | 436 | 435 |

| INN vs INI Contrast | |||||||||

| Partial r | −0.043 | 0.075 | 0.061 | −0.013 | −0.011 | 0.025 | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.01 |

| p-value | 0.239 | 0.040 | 0.090 | 0.719 | 0.771 | 0.497 | 0.399 | 0.905 | 0.792 |

| N | 755 | 755 | 755 | 769 | 768 | 764 | 762 | 763 | 761 |

| TRF Rule-Breaking | |||||||||

| Partial r | −0.005 | 0.08 | 0.081 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.037 | 0.04 | 0.024 | 0.021 |

| p-value | 0.897 | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.973 | 0.917 | 0.345 | 0.309 | 0.552 | 0.589 |

| N | 630 | 630 | 630 | 644 | 643 | 640 | 638 | 639 | 638 |

| TRF Attention Problems | |||||||||

| Partial r | 0.039 | 0.057 | 0.068 | −0.007 | −0.014 | −0.005 | −0.014 | 0.001 | −0.005 |

| p-value | 0.335 | 0.153 | 0.088 | 0.868 | 0.727 | 0.895 | 0.731 | 0.986 | 0.899 |

| N | 630 | 630 | 630 | 644 | 643 | 640 | 638 | 639 | 638 |

| FASD vs no-FASD | |||||||||

| Partial r | 0.027 | 0.313 | 0.348 | 0.094 | 0.079 | 0.042 | 0.016 | 0.082 | 0.069 |

| p-value | 0.457 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.009 | 0.026 | 0.244 | 0.651 | 0.021 | 0.053 |

| N | 774 | 775 | 775 | 790 | 788 | 785 | 782 | 784 | 782 |

Abbreviations: BPR - before pregnancy recognition; APR - after pregnancy recognition; drinks/dd - drinks per drinking day

Partial Spearman correlation coefficients are adjusted for tobacco and illicit drug use during pregnancy.

The Bonferroni-adjusted significance level is 0.0011; p-values below this level are indicated by a *

Further exploration of the association between increasing number of drinks per drinking day prior to pregnancy recognition and FASD classification was conducted using logistic regression, with adjustment for any tobacco use and any other drug use in pregnancy. As shown in Table 8, although confidence intervals were wide, there was a general dose-response relationship between increasing number of drinks per drinking day and FASD. At 1 drink per drinking day compared to none, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for FASD was 3.802 (95% CI 1.634, 8.374); at 2 drinks per drinking day, the aOR for FASD was 7.678 (95% CI 3.307, 17.263); and at 3 drinks per drinking day, the aOR for FASD was 24.908 (95% CI 11.175, 54.462) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Association between maternal report of number of drinks per drinking day before pregnancy recognition and child FASD classification, Pacific Southwest City, Samples 2012, 2013 Combineda

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (reference group) | −3.388 | 0.234 | <0.001* | 1.000 | - |

| 1 drink per drinking day | 1.336 | 0.412 | 0.001* | 3.802 | (1.634, 8.374) |

| 2 drinks per drinking day | 2.038 | 0.418 | <0.001* | 7.678 | (3.307, 17.263) |

| 3 drinks per drinking day | 3.215 | 0.411 | <0.001* | 24.908 | (11.175, 56.462) |

| 4 drinks per drinking day | 3.234 | 0.634 | <0.001* | 25.386 | (7.171, 90.204) |

| 5 or more drinks per drinking day | 2.715 | 0.515 | <0.001* | 15.103 | (5.323, 40.971) |

| Used tobacco during pregnancy | 0.429 | 0.386 | 0.266 | 1.536 | (0.706, 3.226) |

| Used any illicit drugs during pregnancy | 0.136 | 0.501 | 0.786 | 1.146 | (0.410, 2.974) |

Logistic regression; p-values below 0.05 are indicated by a *

DISCUSSION

Using active case ascertainment in a sample of first grade children in a large diverse and urban Pacific Southwest city, we previously reported a conservative prevalence estimate for FASD of 18.8 per 1,000 children in the first academic year, and 22.6 per 1,000 children in the second year, with overlapping confidence intervals. Thus, at a minimum, approximately 2% of children in the normal first grade in school were classified as FASD (May et al., 2018).

In this analysis, 854 children and their mothers from the CoFASP Pacific Southwest urban site participated in a comprehensive evaluation of dysmorphology, growth, neurobehavior, and prenatal alcohol use. These data allowed for descriptive analyses within the sample to better understand the variability and range of clinical presentation of FASD in the general population in one region of the U.S. The data also supported comparisons between FASD children and their mothers to their unexposed or unaffected peers in the same sample to help inform future strategies for primary and secondary prevention and intervention.

Key Findings

There were some differences in race/ethnic distribution across the FASD categories, but all race/ethnic groups in the sample were represented among FASD cases. More males vs. females were identified particularly in the ARND category compared to no FASD. As expected, children with FAS and pFAS were, on average, more likely to be born preterm, had lower birth weights, and were smaller on current height, weight and head circumference. They were also more likely to exhibit classic alcohol-related facial features and other minor anomalies than children with ARND or no FASD.

With respect to neurobehavioral performance, in this sample of children, those with FAS or pFAS were more likely to meet criteria for that classification based on cognitive performance measures, whether or not they had associated behavioral deficits. The opposite pattern was noted with ARND, where behavioral deficits described the majority. However, in examining differences in mean scores on measures in intellectual, executive functioning, learning, and visual spatial domains, there was limited evidence that a narrow number of specific measures were clearly the defining deficits in children with an FASD classification. Instead, there was variability in which specific neurobehavioral functions were impaired within and across groups in the sample (Table 4).

From the perspective of prenatal alcohol exposure, there was some evidence that any maternal drinking and drinks per drinking day before pregnancy recognition, and drinks per drinking day in the 3rd trimester were predictive of child performance, after accounting for other drug and tobacco use in pregnancy (Table 7).

Deficits in behavior, including mood regulation, attention, and impulse control were based on parent or teacher ratings, and were the most consistently differentiating measures across groups. Notably, these differences were largely driven by mean scores in the ARND group, where 63.6% of the 44 affected children met criteria based on findings in the behavioral domains and not on cognitive measures (Table 4).

Similarly, with respect to maternal characteristics, other drug and tobacco use were more common in the FASD group, again, largely driven by reported substance use by mothers of children in the ARND classification. For example, among mothers of children with ARND, 48.8% reported tobacco use in pregnancy and 27.5% reported marijuana use in pregnancy compared to 7.1% and 3.2% in the no FASD group, respectively. Nevertheless, after adjustment for other drug and tobacco use in pregnancy, increasing number of drinks per drinking day prior to pregnancy recognition was strongly predictive of FASD in a dose-response fashion (Table 8).

The U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health survey reported on risk factors for alcohol use among 13,488 pregnant women, ages 15–44, in the U.S. from 2002–2014 (Shmulewitz and Hasin, 2019). Higher risk for any drinking and binge drinking was observed among pregnant women with other substance use including tobacco (aORs 2.9–25.9), depression (aOR 1.6), and unmarried status (aORs 1.6–3.2). Higher risk for any drinking was observed in those with higher education and income. However, higher risk was observed for binge drinking in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters among Blacks (aOR 3.3) and those with lower income and less education (Shmulewitz and Hasin, 2019).

To the extent that these patterns of alcohol consumption directly translate to the incidence of FASD, previous studies in South Africa have also suggested that lower educational attainment and low socioeconomic status are associated with increased risk for FASD. In addition, these previous studies have found FASD to be associated with older maternal age, higher parity, lower body mass index, and tobacco use but not other drugs (May et al., 2017). U.S. survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015–2017 strongly correlated unmarried status with current drinking and binge drinking among pregnant women (Denny et al., 2019). However, data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth demonstrated that 4,303 non-pregnant women were more likely to be at risk of an alcohol-exposed pregnancy if they were married or cohabiting, current smokers, or had a higher education level (Green et al., 2016).

In this Pacific Southwest setting, the picture was somewhat different. We found no indication that the mothers’ socioeconomic status, educational attainment, age, parity or body mass index were important predictors of FASD in their children. However, we did find that marital status, slightly later gestational age on average at pregnancy recognition, history of psychiatric disorders, tobacco and other substance use were reported more frequently by mothers of FASD children than comparison children. These data suggest that it is relevant to determine local or region-specific patterns of risky drinking and associated risk factors for FASD.

Among the 93 children classified as FASD in this analysis, it is important to note that 44 (47%) met criteria for ARND using guidelines established by consensus in preparation for conducting this study (Hoyme et al., 2016). The ARND diagnostic category within the FASD spectrum is currently the least well characterized. For this reason, the study investigators were specifically charged with attempting to better describe how ARND might manifest in children with documented risky prenatal alcohol exposure. To that end, at the Pacific Southwest site, we incorporated developmental concerns in addition to growth in the initial screening criteria. In addition, as children who would be classified as ARND would lack cardinal facial features, the neurobehavioral criteria for ARND were designed to be more stringent than those required for FAS or pFAS (Figure 2). Nevertheless, it is notable that more than half of the ARND children in this sample qualified on behavioral deficits alone. Further work is needed to better delineate the characteristics of children in the ARND group to help guide screening and intervention, as these children may be less likely to be identified as having an alcohol-related deficit.

Strengths and Limitations

The overall eligible school sample size was selected to allow for the expected participation rate. Among 4,409 eligible children in the two academic years combined, 48.1% agreed to be contacted to learn more about the study, and 36.9% of parents/guardians of eligible children consented to screening. Among the 1,201 children who either screened positive or were randomly selected from the screen negatives, 77.2% consented to the full evaluation and 847 had sufficient data to contribute to this analysis.

It is not possible to know how those children and parents who participated did or did not differ from those who declined. Potential participation bias was addressed to some extent in the overall FASD prevalence study by using the conservative denominator of all eligible children to derive the prevalence estimate. However, in the analysis of the characteristics of children and mothers in this report, it is unknown to what extent those who completed the full evaluation are representative of the population from which they were drawn. From the standpoint of internal validity, however, all evaluations of children were completed without the parent, child or examiner being aware of the results of other aspects of the child’s evaluation. And the extensive assessments for dysmorphology, growth, neurobehavior and alcohol history were systematically conducted by experienced and trained examiners.

It is also possible that maternal or collateral report of alcohol use in pregnancy was innacurate. Techniques were used in interviewing mothers or collateral reporters, such as inquiring about usual drinking prior to knowledge of pregnancy, that are thought to be less stigmatizing. Nevertheless, we did have cases of FAS and pFAS where maternal exposure to risky drinking could not be documented. Across the sample, however, we found that 26.4% of women reported any drinking in pregnancy (Table 5) which is consistent with California and national survey data (Tan et al., 2015; Denny et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019).

Informing Prevention and Intervention

The minimum prevalence of FASD estimated for the Pacific Southwest region in the CoFASP study was 1.9–2.3% over the two academic years of the study. Even with active case ascertainment as applied in this general population sample, this conservative prevalence figure is likely an underestimate. In part, this is due to the fact that the method for calculating the conservative estimate assumed that there were no cases of FASD in non-participants in the study. However, in addition, this study sample did not include special populations of children who are likely at higher risk of FASD but also likely to be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed (Chasnoff et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, in both years of the CoFASP study, our conservative estimates exceeded the much older previous estimate of 1% for a County in the Pacific Northwest (Sampson et al., 1997), as well as those derived from recent meta-analyses (Lange et al., 2017; Roozen et al., 2016).

From the standpoint of prevention in this community, the findings of our study suggest that drinking before pregnancy recognition, the most common gestational time period for alcohol exposure in pregnancy, carries a risk for FASD. Prevention of FASD should focus on primary care as well as population health strategies (Green et al., 2016). Individual interventions using a variety of methods can help women recognize and modify drinking patterns prior to conception even, and especially, if pregnancy is not planned (Denny et al., 2019). In this Pacific Southwest community, women with a history of psychiatric problems, tobacco and other substance use who drink alcohol and have the potential to become pregnant may represent a particularly vulnerable group. Importantly, however, specific prevention activities in the community should focus on providing and offering appropriate assistance to at-risk women, irrespective of their age, socioeconomic status, educational level, race/ethnic group, or intention to become pregnant.

What is Known on This Subject:

The characteristic physical features, growth deficiency, and neurobehavioral impairment that comprise the fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) have been well-described. However, the full spectrum of effects encompassed under the umbrella term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) has been less well characterized. Similarly, there have been several maternal characteristics described as risk or protective factors for FASD, but few studies have examined these factors in general U.S. population samples of mothers and their children with or without FASD.

What This Study Adds:

In a large, urban and diverse Pacific Southwest city, active case ascertainment methods were used to comprehensively evaluate a sample in the general population of children in normal first grade in school over two academic years. Children in the sample who were classified as FAS or partial FAS were more likely to exhibit dysmorphic features and were more likely to meet criteria for neurobehavioral impairment on cognitive measures with or without behavioral deficits. In contrast, children who met criteria for alcohol related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) were more likely to meet criteria for impairment on behavioral measures. Mothers of children in the sample classified as FASD were more likely to have recognized pregnancy later in gestation, to have delivered preterm, to be unmarried, and to have a history of other substance use or psychiatric conditions compared to mothers of children not meeting criteria for FASD. However, there were no differences between groups in maternal educational attainment or socioeconomic status. Number of standard alcoholic drinks consumed per drinking day in the period before recognition of pregnancy was strongly predictive of FASD, accounting for tobacco and other substance use.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse, and Alcoholism (NIAAA), grant UO1 AA019879. We extend our thanks to the children, mothers and families who participated; and to the school districts, teachers and principals who made this study possible. We also thank the members of the NIAAA staff and the Steering Committee for their advice and contributions to the study, including Marcia Scott, Ph.D., Kenneth Warren, Ph.D., Judith Arroyo, Ph.D., Michael Charness, M.D., William Dunty, Ph.D., Daniel Falk, Ph.D., Dale Herald, M.D., Ph.D., and Edward Riley, Ph.D.

Funding Source: This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant UO1AA019879 as part of the Collaboration on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Prevalence (CoFASP) consortium.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationship relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, & King L (2016) Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses in foster and adopted children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics 135 (2): 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny CH, Acero CS, Naimi TS, Kim SY (2019) Consumption of alcohol beverages and binge drinking among pregnant women aged 18–44 years - United States, 2015–2017. MMWR 68 (16):365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PP, McKnight-Eily LR, Tan CH, Mejia R, Denny CH (2016) Vital signs: alcohol-exposed pregnancies-United States, 2011–2013. MMWR 65 (4):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme HE, Kalberg WO, Elliott AJ, Blankenship J, Buckley D, Marais AS., Manning MA, Robinson LK, Adam MP, Abdul-Rahman O, Jewett T, Coles CD, Chambers C, Jones KL, Adnams CM, Shah PE, Riley EP, Charness ME, Warren KR, May PA (2016) Updated clinical guidelines for diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 13 (2):e20154256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J, Burd L, Popova S (2017) Global prevalence of fetal alcohol ppectrum disorder among children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 171(10), 948–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVallee RA and Yi H-y (2011) Surveillance Report #92 Apparent per capit alcohol consumption: national, state and regional trends, 1977–2009. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alocholism.

- May PA, De Vries MM, Marais AS, Kalberg WO, Buckley D, Adnams CM, Hasken JM, Tabachnick B, Robinson LK, Manning MA, Bezuidenhout H, Adam MP, Jones KL, Seedat S, Parry CDH, Hoyme HE (2017) Replication of high fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevalence rates, child characteristics, and maternal risk factors in a second sample of rural communities in South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14 (5):522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Chambers CD, Kalberg WO, Zellner J, Feldman H, Buckley D, Kopald D, Hasken JM, Xu R, HOnerkamp-Smith G, Taras H, Manning M, Robinson LK, Adam MP, Abdul-Rahman O, Vaux K, Jewett T, Elliot AJ, Kable JA, Akshoomoff N, Falk D, Arroyo JA, Hereld D, Riley EP, Charness ME, Coles CD, Warren KR, Jones KL, & Hoyme HE (2018) Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in 4 US communities. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 319(5), 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozen S, Peters GJ, Kok G, Townend D, Nijhuis J, Curfs L (2016) Worldwide prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a systematic literature review including meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40 (1):18–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Little RE, Clarren SK, Dehaene P, Hanson JW, Graham JM Jr (1997) Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology 56 (5):317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D and Hasin DA (2019) Risk factors for alcohol use among pregnant women, ages 15–44, in the United States, 2002 to 2017. Prev Med 124:75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, Sniezek JE, Kanny D (2015) Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age-United States, 2011–2013. MMWR 64 (37):1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings. Available at: http://www.americashealthrankings.org. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- US Census Bureau. State & County Quick Facts for 2015. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218. Accessed April 1, 2018

- Woolfenden S, Eapen V, Williams K, Hayen A, Spencer N, Kemp L (2014) A systematic review of the prevalence of parental concerns measured by the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) indicating developmental risk. BMC Pediatr 14: 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Honerkamp-Smith G, Chambers CD (2019) Statistical sensitivity analysis for the estimation of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevalence. Reproductive Toxicology 86:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]