Abstract

Background

Young adult heart transplant (HT) recipients transferring to adult care are at risk for poor health outcomes. We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to determine feasibility and test a transition intervention for young adults who underwent HT as children and transferred to adult care.

Methods

Participants were randomized to the transition intervention (4 months long, focused on HT knowledge, self-care, self-advocacy, and social support) or usual care. Self-report questionnaires and medical records data were collected at baseline and 3 and 6 months after the initial adult clinic visit. Longitudinal analyses comparing outcomes over time were performed using generalized estimating equations and linear mixed models.

Results

Transfer to adult care was successful and feasible (i.e., excellent participation rates). The average patient standard deviation of mean tacrolimus levels was similar over time in both study arms and < 2.5, indicating adequate adherence. There were no between group and within group differences in percent of tacrolimus bioassays within target range (>50%). Average overall adherence to treatment was similarly good for both groups. Rates of appointment keeping through 6 months after transfer declined over time in both groups.

Conclusions

Feasibility of the study was demonstrated. Our transition intervention did not improve outcomes.

Keywords: Heart transplantation, transition program

INTRODUCTION

The transition from childhood to adulthood, referred to as emerging adulthood (i.e., the interval between 18 and 25 years of age )1 is generally characterized by instability, vulnerability, poor judgment and decision-making, risk-taking behaviors, and emotional reactivity.2 This major life transition can be related to poor health outcomes for chronically ill young adults, especially those who have undergone solid organ transplantation.3–6 In a retrospective cohort study of primary heart transplant (HT) recipients ≤ 40 years of age, graft failure rates were highest among 17–29 year olds.5 Poor adherence to the health care regimen, especially with transfer from pediatric to adult health care, is related to poor health outcomes in young adult transplant recipients.7–13 Other factors related to outcomes during transfer from pediatric to adult care include cognitive capacity (e.g., cognitive delay and deficits), psychological factors (e.g., emotional maturity, anxiety, distress, feelings of abandonment by the pediatric healthcare team and uncertainty about the new team), social factors (e.g., parental fears, negotiating the changing role of parental support), demographic factors (e.g., age and gender), as well as inadequate planning by clinicians, and systems issues (e.g., poor communication/coordination between clinical teams and insurance issues).14–16 Interrupted use of health care services during and after transfer of care has frequently been reported.9, 17, 18

The goal of transition, defined as “a complex set of beliefs, skills, and processes that facilitate the movement from pediatric care to adult-centered care”,9, 19 is to provide comprehensive, developmentally appropriate health care in a coordinated, uninterrupted, and seamless manner across centers in partnership with patients. 20 In contradistinction, transfer of care is simply the movement to a new health care setting,20 and for our trial, indicated establishment of care with the adult HT program. The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs found that 60% of youth did not receive the services necessary to successfully transition from pediatric to adult care facilities.21 Findings from a more recent national survey were more bleak, with only 17% and 14% of youth with and without special health care needs, respectively, receiving transition planning support.22

Furthermore, the literature on transition interventions to facilitate transfer of young adults with chronic illnesses to adult care is poor or non-existent, and young adults are not well-equipped to receive care in adult healthcare systems.2, 8, 23–27 A recent Cochrane Review evaluated the effectiveness of transition interventions designed to improve transfer of care from pediatric to adult health services.28 Endpoints included disease-specific outcomes, readiness to transfer, treatment adherence, disease knowledge, health-related quality of life, and resource utilization. The authors reported that no firm conclusions could be drawn regarding effectiveness of interventions, and other models of transitional care need to be evaluated.28 Weissberg-Benchell et al.,29 reviewed three interventions to facilitate transfer of care, including transition programs, and also concluded that additional research was needed, including incorporating intervention work not only in the pediatric setting, but also in the adult care setting, and assessing post-transfer health-related outcomes and clinic attendance at adult clinics beyond the first visit.

A Consensus Conference Report from Bell et al.,8 identified critical milestones to achieve and components of successful transfer for young adult patients after solid organ transplantation prior to transfer of care. Milestones included understanding of cause of organ failure, implications of transplant on health, demonstrating responsibility for own healthcare, and readiness to move into adulthood. Components of successful transfer included assessment of readiness to transfer; development /implementation of an individualized transition plan of care (including the pediatric and adult teams and patient/family, supporting the concept of shared accountability); facilitation of primary and preventive health care; implementation of strategies to enhance medication adherence (e.g., education on medications, self-care strategies, and more frequent clinic visits early after transfer of care); and promotion of educational and vocational planning. Development of educational tools, such as printed materials or videos for self-learning were recommended. Finally, Bell and colleagues8 identified critical research questions regarding young adult solid organ recipient transfer to adult care, including: “Can a formal transition program improve medical and psychosocial outcomes (e.g., rates of acute rejection, disease knowledge, and treatment adherence)?”

In response to these critical questions, we developed and conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial, Pediatric Heart Transplantation: Transitioning to Adult Care (TRANSIT). We tested a transition intervention (i.e., a standardized, tailored transition program focused on increasing HT knowledge, self-care, and self-advocacy skills, and enhancing social support ) designed to improve outcomes (i.e., adherence to immunosuppression and the medical regimen, adverse events, and resource use) for emerging adults who underwent HT as children and transferred to adult care (ClinicalTrials.gov=NCT02090257).

METHODS

Aims and Hypotheses

Our Primary Aim was to assess feasibility of TRANSIT. We hypothesized that ≥ 84% of HT patients would be retained, ≥ 80% would fully participate in the transition program, and ≥ 80% of questionnaires would be completed at all time periods.

Our Secondary Aim was to determine the efficacy of the intervention (i.e., transition program) on the following outcomes: (1) within-participant standard deviation [SD] of average tacrolimus blood levels at specific time points (primary endpoint), (2) tacrolimus levels within target range (determined by HT cardiologists), (3) self-report of adherence to the medical regimen, (4) episodes of adverse events (including acute rejection), and (5) use of health care resources. We hypothesized that through 3 and 6 months after transfer to adult care, intervention arm patients would have (1) lower tacrolimus variability (i.e., SD <2.5),30–32 (2) >50% of tacrolimus levels within target range, (3) better self-reported adherence to the medical regimen, (4) fewer episodes of treated acute rejection, (5) higher rates of clinic attendance and calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) blood draw appointments, and (6) fewer all-cause days re-hospitalized, than patients who received usual care.

Design and Theoretical Framework

We used a prospective, multi-site, non-blinded, variable block size, 1-to-1 randomized controlled trial design. Emerging adult HT recipients (≥ 18 years) were randomized to either the transition program, conducted by pediatric and adult HT coordinators, or to usual care. HT coordinators in each trial arm had no contact with patients in the other arm. Components of our transition program and outcomes were evaluated at baseline (the final pediatric clinic visit), and 3 and 6 months after the initial adult clinic visit. While we recognize that discussions of transferring care often begin much earlier than late adolescence /emerging adulthood,8 we selected the final pediatric clinic visit for study enrollment because that was the time at which actual transfer of care was planned.

The Pai and Drotar33 Treatment Adherence Impact (TAI) model guided assessment of outcomes in our transition program ( On-line supplement 1). Adherence was assessed for two levels of TAI outcomes: (1) patient-level, most proximal to patients and considered to be the most sensitive indicator and (2) meso-level, more distal and includes health care resource utilization. Patient-level outcomes were tacrolimus levels, adverse events, and self-report of adherence to the medical regimen, and meso-level outcomes were rates of keeping appointments and re-hospitalization.

Sample / Setting / Randomization

This trial received Institutional Review Board approval at all participating institutions, and participants provided written informed consent. Study inclusion criteria, previously described, were ≥ 18years; post HT at participating Children’s Hospitals and ready to transfer care (as determined by the pediatric transplant cardiologist as per usual practice at each institution); able to speak, read, and write English; and physically able to participate.34 Young adults with developmental delays were excluded because they have the potential for additional and unique transition planning outside the scope of the intervention for this study, including a focus on level of functioning and guardianship.8, 35 We also excluded young adults with a psychiatric hospitalization within the previous 3 months, based on recommendation from a co-investigator / child psychologist on our team and supported by literature recommending that young adults with acute mental health issues transfer during a time of stability versus crisis to reduce the additional stress of meeting and becoming comfortable with a new health care team while undergoing more intense psychiatric treatment.36 Thus, our plan was to enroll young adults without these additional challenges.

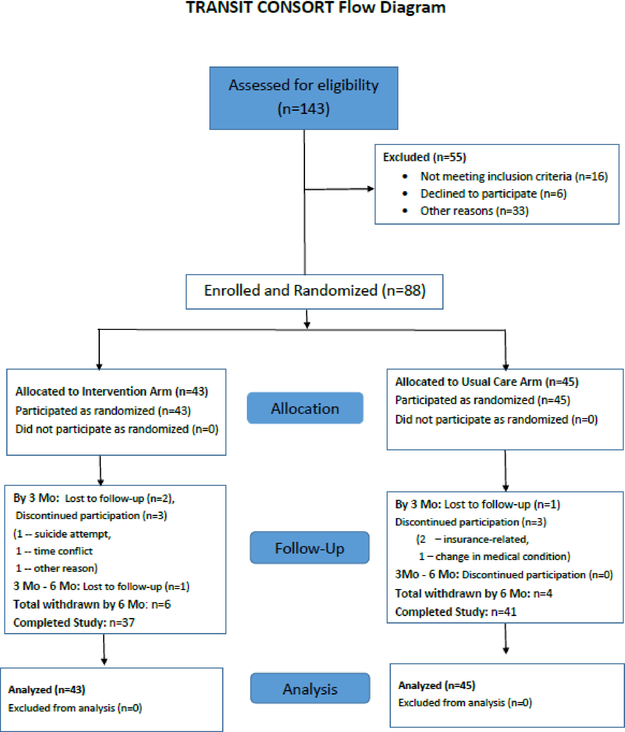

From 3/1/14 to 8/31/16, we screened 143 post HT young adults and enrolled 88 (62%) of them at six U.S. pediatric HT programs (Figure 1). Of the 55 patients not enrolled, 16 did not meet inclusion criteria, 6 declined to participate, and 33 did not participate for other reasons, including: transfer to non-partner institution (n=15); concern about health status (n=8); transfer delay due to use of multiple other pediatric services (n=5); developmental delay (n=2); insurance not accepted at the adult partner institution (n=1); concerns about adherence with the medical regimen (n=1); and psychiatric hospitalization within the previous 3 months (n=1).

Figure 1:

TRANSIT Consort Flow Diagram – This figure demonstrates flow of patients through the study.

Variable block (sizes 2 or 4) 1:1 randomization was used to allocate patients to a study arm within each clinical site (n=43 [intervention] and n=45 [usual care]). Participants transferred to the partner adult HT program for follow-up care. Most programs had a freestanding Children’s Hospital that was partnered with a separate adult hospital on the same medical school campus. For one program, the partner program was contiguous to the pediatric program. At the end of study participation, 37 patients were retained in the intervention arm and 41 in usual care arm (Figure 1).

Data Collection

Data were collected from medical records and self-report questionnaires. Medical records and resource utilization data included heart failure diagnosis, medical/surgical/psychosocial history, immunosuppression and CNI levels, adverse events and treatment, clinic visits, visits for CNI level blood draws, and re-hospitalizations. Three CNI levels prior to transfer of care were included, and up to three CNI levels through 3 months post transfer (1, 2, and 3 month blood draws) and up to five CNI levels through 6 months post transfer (1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 month blood draws) were included. Questionnaires assessed components of the intervention (i.e., HT Knowledge Questionnaire,37, 38 Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire,39 and Social Support Index40) and patient- (Assessment of Problems with the HT Regimen41) level outcomes (Table 1). Psychometric support of questionnaires was reported previously.34 Patients were given a $30 gift card after completion of each set of questionnaires.

Table 1.

Measures of components of the intervention and outcomes reflecting treatment adherence

| Area assessed | Data Source | Response Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Components of the intervention | |||

| Knowledge of heart transplant | HT Knowledge Questionnaire37,38 | 0–100 Higher score=more correct responses |

20-item tool; questions measure knowledge of medications (e.g., purpose of taking tacrolimus), follow-up care (e.g., how to schedule and prepare for the first adult clinic visit), lifestyle (e.g., identifying components of a healthy lifestyle), health status and benefits / risks of HT (e.g., identifying symptoms, benefits and medical risks), and transition to adult care (e.g., identifying components of a successful transition to adult care). |

| Readiness to transition to adult care | Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ)39 |

*2–6 Higher score=higher readiness to transfer: 2=no, I don’t know how; 3=no, I don’t know how but I want to learn; 4=no, but I am learning to do this; 5=yes, I have started doing this; and 6=yes, I always do this when I need to |

29-item survey measuring readiness to transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, with two domains: skills for self-care (e.g., filling prescriptions and scheduling clinic follow-up) and skills for self-advocacy (e.g., reporting symptoms to the healthcare team and making a list of questions prior to a clinic visit). |

| Social support | Social Support Index (SSI)40 | 1–4 1=very dissatisfied 4=very satisfied |

Questionnaire measuring satisfaction with support: emotional, tangible, and overall support for 15 illness-related tasks (e.g., personal care and taking medications). |

| Outcomes reflecting treatment adherence | |||

| Patient-level | |||

| Adherence with medical regimen | Assessment of problems with the HT regimen41 | 1–4 1=hardly ever 4=all of the time |

15-item questionnaire measuring adherence with 15 aspects of the HT medical regimen (i.e., medications [e.g., immunosuppressants], lifestyle [e.g., diet and exercise], appointment keeping [e.g., clinic attendance] and health monitoring [e.g., monitoring symptoms]). |

| Bioassays for tacrolimus and cyclosporine | Medical records | Bioassays, target range, and within target range (yes/no and individualized for patients per HT cardiologists). | |

| Adverse events | Medical records | Episodes of adverse events including specifically acute rejection. | |

| Meso-level | |||

| Health care utilization | Medical records | Clinic and CNI bioassay attendance rates and all-cause days rehospitalized. | |

| Other data | |||

| Demographic questionnaire | Demographic Data Form | Items included: age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, children, educational level, living arrangements, work, and health insurance for patients. |

HT = heart transplant

CNI = calcineurin inhibitor

if patients indicated 1=not needed for my care; those responses were not included in analyses for that item.

Intervention

The intervention (i.e., transition program) was approximately 4 months in duration and had two phases (on-line supplement 2). During Phase 1, at the pediatric site, patients were instructed to complete four education modules, focused on HT knowledge, self-care, self-advocacy, and support (on-line supplement 3) (provided on a flash drive as a power point with voice over) and a written self-test within 2 weeks of receipt of the materials, followed by a discussion with the pediatric HT coordinator. The HT education modules and self-test were developed by investigators from existing HT education materials37, 38 and reviewed by a patient education expert for content clarity, format, and reading level (determined to be at the fifth grade level).42, 43 Patients were requested to complete modules at home; expected time to complete modules and the self-test was 2 hours. If patients did not have access to a computer at home, other ways to access a computer were discussed (e.g., using a computer at the local library). After completion of the modules and self-test, patients were asked to schedule an appointment with the pediatric HT coordinator to discuss completion of these materials face-to-face (preferred) or per telephone. If the patient did not contact the pediatric HT coordinator by 2 weeks after receipt of the modules, the pediatric HT coordinator telephoned the patient to follow-up and schedule the review of materials. A maximum of three phone calls were made, as per protocol. Patients were also asked to schedule a first adult HT clinic appointment in 4 weeks.

The discussion of modules and the self-test score (including missed self-test items) was shared by the pediatric HT coordinator with the adult HT coordinator prior to the first adult HT clinic appointment in order to hand-off baseline educational strengths and deficits. Phase 2 (on-line supplement 4) began at transfer to adult care and included assessment, reinforcement, and tailoring of education module content at the first clinic visit by the adult HT coordinator. Tailoring of discussions focused on areas in which the patient had deficits. Three phone calls were made by the adult HT coordinator at 6, 8, and 10 weeks after the first visit, to further assess and tailor discussions. The intervention concluded at a 3 month clinic visit with final assessment and discussion of adequacy of self-care, self-advocacy, and support, including reinforcement of HT knowledge, as needed.

Usual Care

The usual care group received a standard transfer of care (on-line supplement 2). Patients met with the pediatric HT coordinator to discuss processes, concerns, and questions regarding transferring care and were asked to schedule a first adult HT clinic appointment in 4 weeks. At the first adult clinic visit, the adult HT coordinator provided standard adult program information. Patients were contacted via telephone, by the adult transplant usual care nurse, 6, 8, and 10 weeks later to inquire about concerns after transferring care. Final discussions about transferring care were held at the 3 month clinic visit.

Treatment Fidelity

HT coordinators at sites were trained via webinar to implement the scripted key messaging for clinic visits and telephone calls. Treatment fidelity was monitored at all sites via assessment of audio recordings of pediatric and adult HT coordinator discussions for selected patients in each study arm, followed by review of the recordings by one of the PIs or lead study coordinator with provision of feedback.44Approximately 10% of HT coordinators (including both pediatric and adult) were monitored at each site. Additional monitoring was planned, per protocol, if sites performed poorly based on assessment of audio recordings. HT coordinators followed the scripted messaging very well, and minimal directed feedback was necessary. No additional monitoring was conducted.

Statistical Analyses

Variables were summarized using the mean and SD, or median accompanied by first and third quartiles, if continuous, or counts/percentages, if categorical. Comparisons between the intervention and usual care arms were based on two-sample t-tests with unequal variances and the Satterthwaite’s approximation for the number of degrees of freedom, for continuous variables. Group comparisons of categorical variables were based on the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test (if cell count < 5). To compare percentages of within-target measurements between the two study arms, we used generalized estimating equations, given that potentially multiple assessments per patient were available at each time point. Longitudinal analyses comparing outcomes over time were performed using linear mixed models with an intercept random effect, a center random effect, and group, time and group interaction with time as fixed effects. An unstructured correlation matrix was employed to account for repeated measures recorded within each individual over time. In each model, we adjusted for the number of years since primary HT. Model coefficients for study arm and time are referred to as group and time effect, respectively. Analyses were performed in SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and significance was declared at 2-sided 5% level, with no multiplicity adjustments.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and psychosocial history (collected from medical records, as per notes by mental health professionals) did not differ significantly between groups (Table 2). Average age in both groups was 21 years, and the majority were males, white, educated, single, and living with parents. Heart failure etiology, predominantly cardiomyopathy and congenital heart disease, and time since primary transplant was similar between groups. Patients in both groups, on average, similarly took longer than expected (4 weeks) to transfer care to the adult HT program (intervention group=80 days and usual care group=64 days).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics, Clinical / Psychosocial History, Resource Utilization and Transition Time by Study Arm

| DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | Intervention N=43 | Usual care N=45 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 21.3 ± 3.2 | 21.5 ± 3.3 | 0.75 | ||

| Female gender (n/%) | 19 | (44%) | 22 | (49%) | 0.66 |

| Caucasian race (n/%) | 35 | (81%) | 34 | (76%) | 0.51 |

| Education (n/%) | 0.75 | ||||

| Some high school (9–12) | 4 | (9%) | 6 | (13%) | |

| High school graduate | 13 | (30%) | 8 | (18%) | |

| > High school education | 26 | (60%) | 31 | (68%) | |

| Current Marital Status (n/%) | 0.10 | ||||

| Married | 1 | (2%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| Partner | 4 | (9%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Single | 38 | (88%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| Working for income (n/%) | 17 | (40%) | 26 | (58%) | 0.09 |

| Living Alone (n/%) | 0.96 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | (5%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| No | 41 | (95%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| If no, living with parents | 35 | (85%) | 37 | (86%) | 0.93 |

| CLINICAL AND PSYCHOSOCIAL HISTORY | |||||

| Heart failure diagnosis (n/%) | 0.28 | ||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 21 | (48.8%) | 20 | (44.4%) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 20 | (46.5%) | 25 | (55.6%) | |

| Myocarditis | 2 | (4.7%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Medical history: co-morbidities (n/%) | |||||

| Hypertension (requiring medical therapy) | 19 | (44%) | 18 | (40%) | 0.69 |

| Cardiac allograft vasculopathy | 10 | (23%) | 12 | (27%) | 0.71 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 | (19%) | 15 | (33%) | 0.12 |

| Neoplasm (not PTLD) | 8 | (19%) | 8 | (18%) | 0.92 |

| Arrhythmia requiring pacemaker, ICD, CRT | 5 | (12%) | 2 | (4%) | 0.21 |

| Hyperlipidemia (requiring medical therapy) | 5 | (12%) | 9 | (20%) | 0.28 |

| Surgical history: | |||||

| Years since primary heart transplant (mean± SD) | 43 | 13.5 ± 7.6 | 45 | 14.8 ± 6.6 | 0.41 |

| Heart re-transplant (n/%) | 10 | (23%) | 5 | (11%) | 0.13 |

| Immunosuppression (n/%) | |||||

| tacrolimus (Prograf & Hecoria) | 30 | (70%) | 28 | (62%) | 0.46 |

| cyclosporine | 9 | (21%) | 10 | (22%) | 0.88 |

| mycophenolate (Cellcept & Myfortic) | 26 | (60%) | 23 | (51%) | 0.38 |

| azathioprine | 3 | (7%) | 5 | (11%) | 0.50 |

| sirolimus | 20 | (47%) | 22 | (49%) | 0.82 |

| Episodes of acute rejection (within 6 months prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | 0.23 | ||||

| 0 | 39 | (91%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| 1 | 4 | (9%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| 2 | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Episodes of major infection (within 6 months prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | 0.56 | ||||

| . 0 | 39 | (91%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| . 1 | 3 | (7%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| . 2 | 1 | (2%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Psychosocial history (n/%) | |||||

| Behavioral issues (e.g., poor adherence, substance abuse) | 4 | (9%) | 4 | (9%) | 0.95 |

| Mental disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) | 10 | (23%) | 8 | (18%) | 0.52 |

| Social support (limited) | 7 | (16%) | 6 | (13%) | 0.70 |

| RESOURCE UTILIZATION (events within 6 months prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | |||||

| Re-hospitalizations | 11 | (26%) | 7 | (16%) | 0.24 |

| Missed clinic visits | 8 | (19%) | 4 | (9%) | 0.18 |

| Missed CNI blood draws | 6 | (14%) | 11 | (24%) | 0.21 |

| LENGTH OF TIME TO TRANSITION | |||||

| Duration (days) (mean ± SD) | 41 | 79.9 ± 59.9 | 45 | 63.9 ± 41.3 | 0.16 |

| Duration (days) (median [Q1, Q3]) | 41 | 58 (41, 101) | 45 | 49 (35, 81) | 0.28 |

SD = standard deviation; PTLD=post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease; ICD=implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT=cardiac resynchronization therapy; CNI=calcineurin inhibitor

Feasibility

Rates of retention through 6 months post-transition were higher than the hypothesized 84%: overall (78/88 [89%]), intervention arm (37/43 [86%], usual care arm (4¼5 [91%]). Rates of participation in the intervention arm were also higher than the hypothesized 80%: phase 1 (pediatric site=90% with self-reported length of time to complete modules and self-tests =71.5+34.9 minutes and 26.4+19.6 minutes, respectively) and phase 2 (adult site: first adult clinic visit=95%, telephone follow-up [week 6=100%, week 8=93%, and week 10=97%, and 3 month clinic visit=100%). Lastly, rates of questionnaire completion were higher than the hypothesized 80%: baseline (intervention arm=4¾3 [100%] and usual care arm=45/45 [100%]), 3 months (intervention arm=37/38 [97%] and usual care arm=36/41 [88%]), and 6 months (intervention arm=30/37 [81%] and usual care arm=36/41 [88%]).

Components of the Adherence Enhancing Intervention

Significant differences were not detected across time within groups and between groups regarding overall HT-related knowledge (73–75% item-level correct responses in both groups); satisfaction with support, which was very high in both groups (3.7–3.9 in both groups, range: 1=very dissatisfied to 4 = very satisfied); and self-advocacy skills (4.4–4.5 in both groups, range: 2=no, I don’t know how to 6=yes, I always do this when I need to) (on-line supplement 5A–C. Self-advocacy scores between 4 and 5 indicate that patients are learning how or started to use these skills. Self-care skills increased significantly over time in the usual care group but not in the intervention group (4.1 to 4.4, p=0.007 and 4.2 to 4.4, p=NS, respectively) (on-line supplement 5D). HT-related knowledge subscale scores were also similar for both groups, with highest scores for lifestyle (item-level range: intervention=73.6–75.6% and usual care=75.0–77.8%) and medications (item-level range: intervention=72.4–77.6% and usual care=71.1–73.9%), and lowest scores for follow-up care (item-level range: intervention=69.0–72.9% and usual care=67.1–73.3%) and health status (item-level range: intervention=65.5–68.2% and usual care=61.1–67.4%). Small nonsignificant increases were detected over time for satisfaction with support subscales: tangible support (intervention=3.8–4.0 and usual care=3.8–3.9) and emotional support (intervention=3.8–3.9 and usual care=3.7–3.9).

Outcomes

Patient Level

Immunosuppression

The majority of patients were on tacrolimus (n=29 intervention and n=26 usual care). At baseline, the three most recent tacrolimus levels were included in analyses which included 100% of patients in both study arms. For SD estimation, only patients with two or more tacrolimus level values were included in analyses through 3 months (69% of patients in the intervention arm and 73% of patients in the usual care arm) and through 6 months (97% intervention arm, 100% usual care arm) post-transfer. Mean tacrolimus levels did not differ significantly by time and by group-time interaction (intervention 6.5–6, usual care 5.6–6 [baseline to 6 months]) (on-line supplement 6A). The average within-patient SD of tacrolimus levels was similar over time and < 2.5 in both study arms, indicating adequacy of adherence (intervention 1.6–1.5, usual care 1.3–1.4 [baseline to 6 months]) (on-line supplement 6B)). There were no significant between group and within group differences in percent of tacrolimus levels within target range over time (intervention 69–75%, usual care 72–58% [baseline to 6 months]) (on-line supplement 6C). Notably, the frequency of levels within target range was higher for the intervention group as compared to the usual care group at 3 months (intervention 83%, usual care 51%) and 6 months.

Self-reported Adherence

Average overall self-reported adherence to the treatment regimen range (1=hardly ever to 4=all of the time) was similarly good for both groups, and no significant group-time interactions were detected. Significant improvement across time was detected for the usual care group, but not the intervention group, (3.5–3.7, p=0.003, and 3.6–3.7, p=NS respectively) (on-line supplement 7A). In both groups, average self-reported adherence subscale scores were highest for medications (range 3.7–3.9) and appointment keeping (range 3.6–3.8), and lowest for lifestyle (range 2.8–3.1) and health monitoring (range 2.6–3.1) (on-line supplement 7B–E). No significant differences by time and group-time interaction were found for subscale scores, except for medications differences over time for the usual care, but not the intervention group (3.7–3.9, p=0.045 and 3.8–3.9, p=NS, respectively) (on-line supplement 7B–E).

Adverse events

The number of patients with adverse events through 3 and 6 months was low to moderate with a trend toward more adverse events in the intervention group by 6 months. (Table 3). The average number of events per patient through 3 and 6 months was similar (Table 3) in the two trial arms. Number of episodes of treated acute rejection were low through 3 and 6 months, but differed significantly between groups through 6 months (intervention=5, usual care=0, p=0.021) (Table 3), with three of the five episodes observed in one patient.

Table 3.

Patient-Level and Meso-Level Outcomes between groups

| Intervention | Usual Care | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Level Outcomes | |||

| Adverse events | |||

| Patients with adverse event through 3 months (n/%) | 13/38 (34%) | 7/41 (17%) | 0.12 |

| Patients with adverse event through 6 months (n/%) | 16/37 (43%) | 9/41 (22%) | 0.055 |

| Events per patient through 3 months (mean +SD) | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Events per patient through 6 months (mean +SD) | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.11 |

| Episodes of treated acute rejection through 3 months (n/%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.11 |

| Episodes of treated acute rejection through 6 months (n/%) | 5 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0.021 |

| Participant death (n) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Meso-Level Outcomes | |||

| Resource Utilization | |||

| Appointment keeping | |||

| Clinic attendance through 3 months (n/%) | 36/38 (95%) | 41/41 (100%) | 0.23 |

| Clinic attendance through 6 months (n/%) | 33/37 (89%) | 38/41 (93%) | 0.70 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor blood draw appointment keeping through 3 months (n/%) | 30/38 (79%) | 36/41 (88%) | 0.37 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor blood draw appointment keeping through 6 months (n/%) | 25/37 (68%) | 32/41 (78%) | 0.32 |

| Re-hospitalization | |||

| All-cause re-hospitalizations through 3 months (n/%) | 5 (13%) | 2 (5%) | 0.25 |

| All-cause re-hospitalizations through 6 months (n/%) | 8 (22%) | 4 (10%) | 0.21 |

| Patient-Level Outcomes | |||

| Adverse events | |||

| Patients with adverse event through 3 months (n/%) | 13/38 (34%) | 7/41 (17%) | 0.12 |

| Number of days re-hospitalized through 3 months (n/%) | 0.80 | ||

| 0 | 35 (92%) | 39 (95%) | |

| 1–5 | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

| 6–10 | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Number of days re-hospitalized through 6 months (n/%) | 0.17 | ||

| 0 | 32 (86%) | 39 (95%) | |

| 1–5 | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | |

| 6–10 | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 11–15 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

Meso Level

Appointment keeping and re-hospitalization

Rates of keeping clinic and CNI blood draw appointments were similar between groups through 3 months and 6 months, and declined over time (Table 3). All-cause number of re-hospitalizations was low and similar between groups through 3 and 6 months after transfer (Table 3). Number of days re-hospitalized was also similar between groups through 3 and 6 months after transfer, with the majority of re-hospitalizations being < 10 days.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot trial to directly and methodically test a transition intervention designed to improve outcomes for young adult HT recipients transferring to adult care. We concluded that conduct of our pilot trial was feasible, with excellent rates of retention and participation in the intervention. However, the hypothesis for our primary endpoint of our secondary aim was not met. Both groups had similar tacrolimus SD < 2.5, indicating adequate adherence.30–32 Additionally, there were no significant between-group differences for self-report of adherence to the medical regimen, although usual care participants had improved self-reported adherence (overall and for medications) over time. Adverse events, except episodes of acute rejection through 6 months, did not differ between groups over time. Lastly, there were no between-group differences for appointment keeping and re-hospitalization.

Insights into Findings from our Pilot Trial

While this was a negative pilot trial, it was informative, from which we learned a fair amount and offered insights into the hurdles surrounding transition planning for young adult HT recipients who transfer from pediatric to adult services, which may provide guidance for future trials and patient care. The lack of difference in tacrolimus SDs between groups over time may have been multi-factorial. At baseline, patients in both groups had tacrolimus SDs <2.5, high levels of self-reported medication adherence, modestly high HT knowledge scores regarding medication, and reported high levels of satisfaction with support. Thus, fairly high medication knowledge, high adherence, and support in both groups at baseline may have led to a ceiling effect, dampening the potential impact of our intervention on outcomes. The relationship of knowledge and support with measures of adherence has been documented in the literature.45–47

Additionally, Killian48 reported that parental factors (e.g., family composition) were related to adherence after pediatric heart and lung transplantation. The majority of HT recipients in both groups within our study were single and living with their parents. Thus, parents in both groups may have continued to manage care and not encourage self-care, which may also have contributed to a lack of difference in adherence between groups.

Motivation and clinical trial participation, as well as the Hawthorne effect, may also have influenced our negative findings. Regarding enrollment, one might question whether only young HT recipients who were “motivated” to improve outcomes joined the study. The very small increase in self-care skills in the usual care group over time may reflect enrollment by more motivated young adult HT recipients. However, this particular finding must be interpreted cautiously, as statistical significance does not always imply a clinically important difference.49

The Hawthorne effect also may have contributed to our negative pilot trial, (i.e., patients in both groups had frequent CNI bioassays [i.e., frequent monitoring of medication taking behavior] after transfer to adult care, which may have inadvertently supported good medication taking behavior in both groups). Notably, while patients in both groups had >50% of tacrolimus levels within target range after transfer, the rates were higher in the intervention group, suggesting that our intervention may have had some effect on adherence with taking immunosuppressant medication.

The decline in appointment keeping over time in both study arms is consistent with other studies.50–52 Our finding of low knowledge scores regarding follow-up care supports this idea. Finally, while rates of re-hospitalization were low in both groups, low scores regarding knowledge of health status in both groups were similar to findings from other studies.53 These results suggest the need for a stronger focus on health monitoring and follow-up care in future trials of transition planning.

Clinical and Research Implications

Transition planning should begin prior to transfer of care.54 The exact timing for initiating this dialogue remains unknown; early adolescence has been recommended by some,35 with the caveat that transfer of care should occur when patients are stable as outpatients.36, 55 Furthermore, we identified high satisfaction with support for patients transferring care in both arms of our study. Thus, family focused interventions may also be beneficial, as well as those focused on individuals. Regarding parental involvement, the literature supports gradual movement of parents from a coordinating care role to one of supporting care, thus modeling and encouraging young adult independence and self-responsibility.8, 29, 54

Inclusion of adult HT coordinators in our transition program is novel. Current transition programs involve transition planning by pediatric practitioners, who facilitate introduction to adult HT clinicians and services, but the transition planning concludes shortly after transfer to adult care.29 Our transition program included discussions with not only pediatric HT coordinators, but also with adult HT coordinators, who tailored discussions to concerns and deficits that were identified after transfer to adult services. Thus, engagement of adult clinicians in transition-related care after transfer to adult services may be beneficial in improving outcomes, but requires further study. We also recommend extending the duration of transition planning to longer than 3 months after transfer to adult care in future trials, supported by our finding that self-advocacy and self-management did not change over time for patients randomized to our intervention group. Implementation and testing of this novel synergistic approach to transition-related care requires a multidisciplinary pediatric-adult collaborative team to develop policies and protocols. Testing of the transition program and its impact on important outcomes, at both the patient- and meso-levels, later as well as early after transfer of care, are of critical importance.

Study Limitations

Our pilot trial was limited by a small sample size and short duration of follow-up after transfer of care. Also, the majority of our cohort was fairly homogeneous (i.e., single, white, > than a high school education, and living with parents), thus reducing sample diversity, potentially biasing our findings (i.e., patients being less at risk for poor adherence during transfer of care), and limiting generalizability. Additionally, readiness to transfer care to a partner adult HT program was subjective, as it was determined by pediatric transplant cardiologists. This may have introduced bias, as only the most capable patients were selected. All of our participating pediatric sites have a legacy of excellence as HT centers, and transition efforts at participating pediatric centers may have begun several months or years before actual transfer of care (at which time patients enrolled in our study), which may have impacted our findings. None of our participating centers had formal transition programs in place.

There were also potential limitations of the intervention. The education modules were completed at home without direct supervision. On-site supervision of module completion may have ensured that the full dose of the intervention was received and may have increased the potential for finding significant differences in outcomes between groups. Participant-reported length of time to module completion and self-testing were, on average, almost as long as expected. Furthermore, while our curriculum addressed important HT and general medical knowledge and skills, content not included in our curriculum may be relevant. Other teaching modalities (e.g., videos or class room learning followed by discussion) may also have been more appealing and enhanced completion of educational materials.

CONCLUSIONS

Feasibility of the study was achieved with excellent retention and participation in the intervention. However, our transition intervention did not improve the outcomes selected. Notably, proof of feasibility is an important first step that provides a platform for development of future interventions in larger randomized controlled trials.

Based on what we have learned from this informative pilot trial, we recommend that future trials of transition planning for young adult HT recipients begin earlier than the time when patients are scheduled to transfer care, and that they last longer after actual transfer to adult services. We believe that our transition content addressing knowledge, self-care, self-advocacy, and support may promote good patient- and meso- level outcomes. However, this content needs to be tested in a larger, more diverse young adult HT patient population. Furthermore, we recommend including content in the intervention directed toward facilitating change in the parental role. Use of teaching modalities that are more in tune with the way young adults learn today may enhance completion of all materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), grant number R34 HL111492. (PIs E Pahl and K Grady)

Footnotes

Relationships with industry: All authors have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000;55:469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell LE, Sawyer SM. Transition of care to adult services for pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients. Pediatr Clin North Am 2010;57:593–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keith DS, Cantarovich M, Paraskevas S, Tchervenkov J. Recipient age and risk of chronic allograft nephropathy in primary deceased donor kidney transplant. Transpl Int 2006;19:649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringewald JM, Gidding SS, Crawford SE, Backer CL, Mavroudis C, Pahl E. Nonadherence is associated with late rejection in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Pediatr 2001;139:75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster BJ, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Dharnidharka V, Ng V, Conway J. High risk of graft failure in emerging adult heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2015;15:3185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster BJ, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Platt R, Samuel S, Hanley J. Association between age and graft failure rates in young kidney transplant recipients. Transplant 2011;92(11):1237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annunziato RA, Emre S, Shneider B, Barton C, Dugan CA, Shemesh E. Adherence and medical outcomes in pediatric liver transplant recipients who transition to adult services. Pediatr Transplant 2007; 11:608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell LE, Bartosh SM, Davis CL, et al. Adolescent transition to adult care in solid organ transplantation: A consensus conference report. Am J Transplant 2008;8:2230–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredericks EM. Nonadherence and the transition to adulthood. Liver Transpl 2009; 15(suppl 2):S63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBride ME, Foushee MT, Brown RN, Ewald GA, Canter CE. Outcomes of pediatric heart transplant recipients transitioned to adult care: An exploratory study. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:1309–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuel SM, Nettel-Aguirre A, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Graft failure and adaptation period to adult healthcare in pediatric renal transplant patients. Transplant 2011;91(12):1380–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaRosa C, Glah C, Baluarte J, Meyers K. Solid-organ transplantation in childhood: Transitioning to adult health care. Pediatr 2011;127(4):742–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keuzer M, Prufe J, Oldhafer M, et al. Transitional care and adherence of adolscents and young adults after kidney transplantation in Germany and Austria. Med 2015;94(48):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Annunziato RA, Arrato N, Rubes M, Arnon R The importance of mental health monitoring during transfer to adult care settings as examined among pediatric transplant recipients. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morsa M, Gagnayre R, Deccache C, Lombrail P. Factors influencing the transition from pediatric to adult care: A scoping review of the literature to conceptualize a relevant education program. Pt Educ Counsel. 2017;100:1796–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White P, Cooley WC. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Ped. 2018;142(5):e20182587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredericks EM, Magee JC, Eder SJ, et al. Quality improvement targeting adherence during the transition from a pediatric to adult liver transplant clinic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2015;22:150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18., Mitchell T, Gooding H, News C,et al. Transition to adult care for pediatric liver transplant recipients: the Western Australia experience. Pediatr Transplant 2017;21:e12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer SM, Blair S, Bowes G. Chronic illness in adolescents: Transfer or transition to adult services? J Paediatr Child Health 1997;33:88–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callahan ST, Winitzer RF, Keenan P. Transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care: A challenge for patients with chronic disease. Curr Opin Pediatr 2001;13:310–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Service Administration MaCHB. The national survey of children with special health care needs chartbook 2005–2006. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebrun-Harris L, McManus M, Ilango S, Cyr M, McLellan S, Mann M, White P. Transition planning among US youth with and without special health care needs. Pediatr. 2018;142(4):e20180194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lotstein DS, Ghandour R, Cash A, McGuire E, Strickland B, Newacheck P. Planning for health care transitions: Results from the 2005–2006 national survey of children with special health care needs. Pediatr 2009;123:e145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heery E, Sheehan A, White A, Coyne I. Experiences and outcomes of transition from pediatric to adult health care services for young people with congenital heart disease: A systematic review. Congenit Heart Dis 2015;10(5):413–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Everitt I, Gerardin J, Rodriguez F, Book W. Improving the quality of transition and transfer of care in young adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs AH, McCrindle BW. So hard to say goodbye: Transition from paediatric to adult cardiology care. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster BJ. Heightened graft failure risk during emerging adulthood and transition to adult care. Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;29(4):CD00979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weissberg-Benchell J, Shapiro JB. A review of interventions aimed at facilitating successful transition planning and transfer to adult care among youth with chronic illness. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46(5):e182–e187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Shneider BL, et al. Improving adherence to medications in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant May 2008;12(3):316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shemesh E, Shneider BL, Savitzky JK, et al. Medication adherence in pediatric and adolescent liver transplant recipients. Pediatr April 2004;113(4):825–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stuber ML, Shemesh E, Seacord D. Washington J 3rd, Hellemann G, McDiarmid S. Evaluating non-adherence to immunosuppressant medications in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transpl May 2008;12(3):284–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pai AL, Drotar D. Treatment adherence impact: The systematic assessment and quantification of the impact of treatment adherence on pediatric medical and psychological outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol 2010; 35:383–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grady KL, Van’t Hof K, Andrei AC, et al. Pediatric heart transplantation: Transitioning to adult care (TRANSIT): Baseline findings. Pediatr Cardiol 2018;39:354–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical Report – Supporting the Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatr. 2011;128:182–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart LC, Maslow G. The medical transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care: Considerations for child and adolescent psychiatrists. Child, Adolesc, Psyciatr Clin N Am J.2018;27:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute, Heart Transplantation: A patient handbook, 2005. Pages 1–56.

- 38.Children’s Memorial Hospital. Heart Transplantation Education Handbook. 2010.

- 39.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: Validation of the traq--transition readiness assessment questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:160–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure awaiting transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C. Patient compliance at one year and two years after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:383–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lennon CB, Burdick H. The Lexile Framework as an approach for reading measurement and success. MetaMetrics, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Paperback; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellg A, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol 2004; 23(5):443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bidwell J, Higgins M, Reilly C Clark P, Dunbar S. Shared heat failure knowledge and self-care outcomes in patient-caregiver dyads. Heart Lung 2018;47(1):32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riles E, Jain A, Fendrick M. Medication adherence and heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep 2014;16:458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu JR, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Predictors of medication adherence using a multidimensionality adherence model in patients with heart failure. J Cardiac Fail. 2008;14:603–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Killian MO. Psychosocial predictors of medication adherence in pediatric heart and lung transplantation. Pediatr Transpl 2017e12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fayers PM, Machin P. Quality of life Assessment, Analysis, and Interpretation. John Wiley & Sons, LTD; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shemesh E, Annunziato R, Arnon R, Miloh T, Kerkar N. Adherence to medical recommendations and transition to adult services in pediatric transplant reciients. Curr Opin Organ Transpl 2010; 15(3):288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fredericks EM. Nonadherence and the transition to adulthood. Liver Transpl. 2009; 15 Suppl 2:S63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, et al. Current methods of transfer of young people with type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet Med. 2002;19:649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uzark K, Smith C, Donohue J, et al. Assessment of Transition Readiness in Adolescents and Young Adults with Heart Disease. J. Pediatr December 2015;167(6):1233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Putschoegl A, Dipchand A, Ross H, Chaparro C, Johnson J. Transitioning from pediatric to adult careafter thoracic transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:823–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knauth A, Verstappen A, Reiss J, Webb GD. Transition and transfer from pediatric to adult care of the young adult with complex congenital heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.