Abstract

Almost half of young American children live in low-income families, many with unmet needs that negatively impact health and life outcomes. Understanding which needs, proactively addressed, would most improve their lives would allow maternal and child health practitioners and social service providers to generate collaborative solutions with the potential to affect health in childhood and throughout the life course. 2-1-1 referral helplines respond to over 16 million inquiries annually, including millions of low-income parents seeking resources. Because 2-1-1 staff members understand the availability of community resources, we conducted an online survey to determine which solutions staff believed held most potential to improve the lives of children in low-income families. Information and referral specialists, resource managers, and call center directors (N = 471) from 44 states, Puerto Rico, and Canada ranked needs of 2-1-1 callers with children based on which needs, if addressed, would help families most. Child care (32%), parenting (29%) and child health/health care (23%) were rated most important. Across all child care dimensions (e.g., quality affordable care, special needs care), over half of respondents rated community resources inadequate. Findings will help practitioners develop screeners for needs assessment, prioritize resource referrals, and advocate for community resource development.

Keywords: life course health development, child health, health, family health, health disparities, low income

INTRODUCTION

Almost half of young children in the United States now live in low-income families (Jiang et al., 2017). Given the deleterious and potentially lifelong effects of poverty and its associated stressors on physical and mental health, cognitive development, educational achievement, and other life course outcomes (Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health et al. 2012; Hair et al., 2015; Carter, 2014; Park et al., 2011), it is critical to take proactive steps to support the security and development of disadvantaged children.

One place to address these issues is in the pediatric care setting. Pediatric health providers are directed to address social needs in addition to health (Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health et al., 2012; Council on Community Pediatrics, 2013). Researchers argue that individual and population level health across the lifespan can be enhanced by integration of health care and community social services (Pullon et al., 2015; Halfon et al., 2014). Brief screenings by pediatric providers can be effective in identifying basic and social needs and connecting families to helping resources (Fierman et al., 2016; Garg et al., 2015), but the success of these efforts is complicated by hardships low-income families face in daily life. Parents who experience intergenerational poverty may be less likely to seek parenting support (Smith et al., 2015), and parents who are not U.S. citizens, who are unemployed, or who have a high school education or less may have lower awareness of community resources (Yu et al., 2005). Low-income parents who seek support from community agencies may also have mixed feelings about the support they receive (Silverstein et al., 2008).

Maternal and child health providers grappling with how best to serve low-income families can benefit from the insights and experience of social service agencies that routinely interact with low-income callers facing a spectrum of unmet needs. Unique among such agencies is the 2-1-1 helpline, an information and referral service that serves predominantly low-income families in the U.S. and Canada and receives over 16 million calls per year and millions more digital inquiries (Daily, 2012; Kreuter et al. 2012). 2-1-1 is a Federal Communications Commission-designated 3-digit telephone exchange similar to 9-1-1. It links callers with health and social services in their community through more than 200 call centers serving all 50 U.S. states and reaching 93% of the U.S. population (www.211.org) as well as seven provinces and one territory in Canada (http://211.ca/).

Services such as 2-1-1 have the potential to serve as a bridge, both between families and the resources they need and between health care practices and community resources that might help their patients (Fierman et al. 2016). A large majority of callers to 2-1-1 are women, and more than half report living with children under age 18 (Purnell et al., 2012). Compared with general population estimates, 2-1-1 callers have lower education levels, higher unemployment rates, and are less likely to have health insurance; the overwhelming majority call 2-1-1 seeking assistance with basic human needs such as finding or paying for shelter, heat, electricity, or food (Alcaraz et al., 2012; Eddens et al., 2011; Kreuter et al., 2012; Purnell et al., 2012; http://211counts.org). Callers also use clinical preventive services at rates significantly lower than national averages (Purnell et al., 2012). However, callers are receptive to answering brief needs assessments and receiving referrals for services such as cancer screening (Eddens et al., 2011; Kreuter et al., 2012), HPV vaccination, smoking cessation programs, smoke-free homes information (Purnell et al., 2012), and identification of developmental issues in children of callers (Roux et al., 2012). In addition to providing these health-related referrals to people who call 2-1-1 directly, the Health Care Delivery Subcommittee of the Academic Pediatric Association Task Force on Child Poverty has suggested health care practices could provide referrals to 2-1-1 and similar organizations when screenings suggest patients face poverty-related problems (Fierman et al., 2016).

In order for such partnerships to be effective, however, it is important to understand both the current availability of community resources to meet poverty-related needs and also potential interventions that could be developed to improve the lives of families living in poverty. To that end, we conducted the first national survey of 2-1-1 call center staff. These trained professionals routinely engage with both low-income families and social service agencies, and they have extensive experience listening to low-income callers every day and searching for resources to help them. They understand from first-hand accounts the daily life challenges of low-income families and are thus uniquely positioned to suggest potential solutions. We sought to determine staff members’ perspectives about which needs of 2-1-1 callers with children were most important to address, what resources would be most helpful in addressing those needs, how comfortable staff would be initiating proactive screening for those needs, and the availability of relevant resources in their community.

METHODS

Sample and Recruitment Procedures

We recruited 2-1-1 professionals from three job categories: information and referral (I&R) specialists, who take calls from those seeking assistance, assess their needs, and provide referrals; resource managers, who maintain the 2-1-1 database of helping resources available in each community; and center or state directors, who oversee the operation of a local 2-1-1 helpline or all 2-1-1s in a state.

Working in partnership with the Alliance of Information and Referral Systems (AIRS, the professional association of information and referral providers), we approached potential respondents in two ways. First, AIRS sent e-mail letters to its state directors group (n = 110) that included a link to the online survey. Recipients were encouraged to complete the survey if they were call center directors and also forward survey information to other call center directors within the state, who could then recruit additional respondents from each call center (ideally one lead administrator, one resource manager, and three I&R specialists). Second, additional letters including the survey link were sent a listserv of AIRS members (n = 600).

The survey was available from February 25 to March 31, 2013 and was administered using Qualtrics, an online survey system. During this period, AIRS e-mailed four reminders to each e-mail list. The Qualtrics system prevented respondents from taking the survey multiple times. Upon survey completion, respondents could opt into a lottery to win one of two iPads. Due to the nature of the data collected, the university’s Human Research Protections Office considered this research exempt according to the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations and allowed participants to view a study information sheet online in lieu of providing verbal or written consent.

Survey

The survey was designed with input from AIRS officials and scholars in public health and social work. Based on a review of the literature and prior work with 2-1-1 helplines, the research team developed a draft set of general priorities and more specific dimensions and activities associated with each priority (see Online Supplement). Two focus groups made of up a total of approximately 20 professors of social work and public health at Washington University in St. Louis were conducted with the goal of ensuring the survey covered the most important services, topics, and needs. Focus group participants were shown draft topics and categories and were asked to add anything that they thought was important. Once the survey was drafted, it was then reviewed by AIRS leadership to ensure face validity and clarity.

Survey questions asked respondents about their professional role, the state/province of their call center, and the population served by their 2-1-1 helpline (Table 1). Respondents then answered questions about what would most improve the lives of callers. Separate questions were asked about adult callers and adult callers with children. This paper focuses only on the latter.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for staff at 2-1-1 call centers in the U.S. and Canada who completed the online survey (N = 471).

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Role at 2-1-1 | |

| Information & referral specialist | 56% (263) |

| Resource manager | 19% (91) |

| Call center director | 25% (117) |

| Location served | |

| United States | 98% (459) |

| Canada | 3% (12) |

| Coverage area | |

| Entire state/province | 25% (120) |

| Local or regional area within state/province | 69% (327) |

| Regional area across 2 or more states/provinces | 5% (24) |

| Urbanicity | |

| Mostly or entirely urban | 27% (127) |

| Equally urban and rural | 50% (235) |

| Mostly or entirely rural | 22% (104) |

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding. Due to missing data, N = 466 for urbanicity.

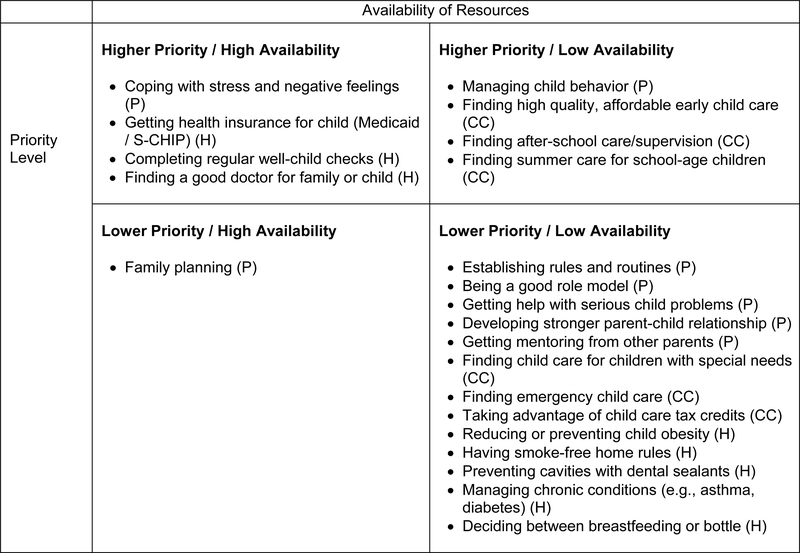

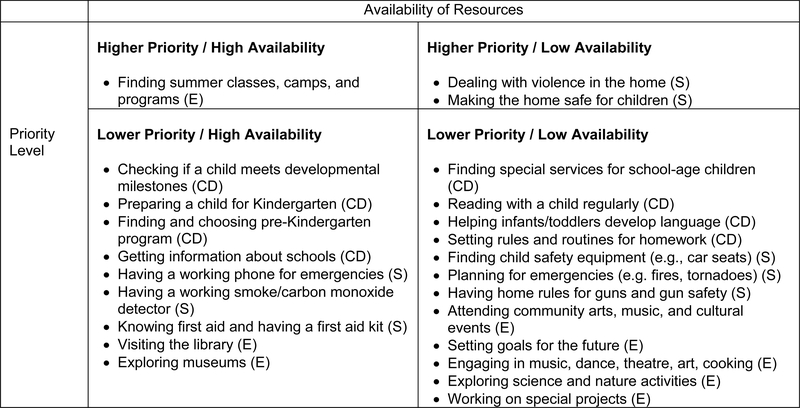

Respondents first viewed a list of six general need categories: parenting, child health and health care, child care, child development and learning, home and child safety, and enrichment activities (see Online Supplement). They were asked, “Of these six needs, which three are the most important for improving the lives of children of your 2-1-1 callers?” Next, for each of the three needs they selected, they were shown a list of 6–8 dimensions of each need (see Table 2) and asked to select the three that were most important for improving the lives of children. Respondents were instructed to answer both questions based both on callers’ directly expressed needs, as well as “hidden” needs that may emerge over the course of conversations. Finally, for each dimension selected, respondents were asked to rate the availability of helping resources in their community (“How would you rate the number of resources available to your callers for this priority?”; adequate/inadequate/I don’t know) and acceptability of proactive screening for the need (“How comfortable would you feel bringing up this subject with your callers?”: very comfortable/comfortable/uncomfortable/very uncomfortable). Table 2 reports the values for 46 different dimensions of the six need areas. Figure 2 classifies these dimensions for the three top needs based on availability and acceptability, and Figure 3 does the same for the three lower need areas.

Table 2.

Respondents’ perceptions of general priorities and activities that could best help 2-1-1 callers with children. Participants (N = 471) were asked to rank their top three general priorities from six major categories. For each general priority, participants who selected it then chose the three activities they thought would be most helpful for callers with children, rated the availability of resources to support those activities, and rated their comfort discussing the topic with 2-1-1 callers.

| Chosen a priority | Adequate resources | Comfortable with topic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n/number responding) |

% (n/number responding) |

|

| Parenting (n = 345) | 73% (345) | ||

| Coping with stress and negative feelings | 60% (207) | 51% (106/206) | 89% (184/206) |

| Managing child behavior | 57% (197) | 44% (86/196) | 82% (159/195) |

| Getting help with serious child problems | 49% (168) | 39% (65/168) | 84% (141/167) |

| Developing stronger parent-child relationship | 42% (144) | 44% (62/142) | 85% (120/141) |

| Establishing rules & routines | 28% (97) | 28% (27/96) | 74% (70/94) |

| Family planning | 27% (94) | 54% (51/94) | 71% (66/93) |

| Being a good role model | 25% (85) | 19% (16/85) | 58% (47/81) |

| Getting mentoring from other parents | 10% (34) | 35% (12/34) | 88% (30/34) |

| Child Health and Health Care (n = 325) | 69% (325) | ||

| Getting health insurance for child (Medicaid/S-CHIP) | 77% (249) | 74% (184/248) | 96% (234/245) |

| Completing regular well-child checks | 59% (192) | 64% (123/191) | 92% (175/191) |

| Finding a good doctor for family or child | 58% (187) | 51% (96/187) | 92% (172/186) |

| Managing chronic conditions (e.g. asthma, diabetes) | 30% (97) | 44% (42/96) | 89% (83/93) |

| Reducing or preventing child obesity | 22% (73) | 27% (20/73) | 74% (54/73) |

| Preventing cavities with dental sealants | 14% (47) | 44% (20/46) | 84% (38/45) |

| Having smoke-free home rules | 11% (35) | 17% (6/35) | 59% (19/32) |

| Deciding between breastfeeding or bottle | 2% (5) | 40% (2/5) | 40% (2/5) |

| Child Care (n = 317) | 67% (317) | ||

| Finding high-quality, affordable early child care | 85% (270) | 35% (95/270) | 90% (239/267) |

| Finding after-school care/supervision | 62% (198) | 39% (77/198) | 90% (173/193) |

| Finding summer care for school-age children | 51% (163) | 37% (61/163) | 94% (150/160) |

| Finding child care for child w/special needs | 37% (118) | 29% (34/118) | 80% (94/117) |

| Finding emergency child care | 26% (83) | 12% (10/83) | 83% (69/83) |

| Taking advantage of child care tax credits | 9% (27) | 46% (12/26) | 88% (23/26) |

| Child Development and Learning (n = 230) | 49% (230) | ||

| Checking if a child meets developmental milestones | 49% (112) | 63% (71/112) | 88% (98/111) |

| Finding special services for school-age children | 46% (105) | 43% (45/105) | 88% (92/104) |

| Reading with a child regularly | 42% (96) | 43% (41/96) | 77% (72/94) |

| Preparing a child for Kindergarten | 40% (91) | 54% (49/91) | 88% (78/89) |

| Finding and choosing pre-Kindergarten programs | 36% (82) | 59% (48/82) | 91% (74/81) |

| Helping infants/toddlers develop language | 35% (81) | 47% (38/81) | 79% (62/78) |

| Getting information about schools | 26% (60) | 63% (38/60) | 88% (53/60) |

| Setting rules and routines for homework | 25% (57) | 28% (16/57) | 77% (43/56) |

| Home and Child Safety (n = 97) | 21% (97) | ||

| Dealing with violence in the home | 65% (63) | 34% (19/56) | 89% (49/55) |

| Making the home safe for children | 60% (58) | 43% (23/54) | 83% (44/53) |

| Finding child safety equipment (e.g. car seats) | 43% (42) | 30% (12/40) | 95% (37/39) |

| Having a working phone for emergencies | 24% (23) | 52% (11/21) | 100% (20/20) |

| Having a working smoke/carbon monoxide detector | 19% (18) | 56% (10/18) | 89% (16/18) |

| Knowing first aid and having a first aid kit | 18% (17) | 53% (8/15) | 86% (12/14) |

| Planning for emergencies (e.g. fires, tornadoes) | 16% (16) | 44% (7/16) | 94% (15/16) |

| Having home rules for guns and gun safety | 12% (12) | 18% (2/11) | 64% (7/11) |

| Enrichment Activities (n = 93) | 20% (93) | ||

| Finding summer classes, camps, and programs | 62% (58) | 53% (30/57) | 93% (52/56) |

| Attending community arts, music, & cultural events | 49% (46) | 48% (22/46) | 86% (38/44) |

| Setting goals for the future | 44% (41) | 24% (10/41) | 78% (32/41) |

| Engaging in music, dance, theatre, art, cooking | 43% (40) | 38% (15/39) | 89% (34/38) |

| Exploring science and nature activities | 32% (30) | 41% (12/29) | 72% (21/29) |

| Visiting the library | 32% (30) | 90% (27/30) | 97% (28/29) |

| Working on special projects | 15% (14) | 21% (3/14) | 86% (12/14) |

| Exploring museums | 9% (8) | 63% (5/8) | 50% (4/8) |

Note: Variability in denominators in the second and third columns reflects a small amount of missing data due to participants’ skipping questions. Comfort raising the topics with callers was measured as percentage of respondents who said they were “comfortable” or “very comfortable” with a topic.

Figure 2.

Resource availability for high and low priority activities that might address key areas of need for parenting, child care, and child health/health care. Each activity/skill was classified as higher priority if more than 50% of respondents who chose a particular general category ranked that activity/skill in the top 3; otherwise, the activity/skill was classified as lower priority. Resources were classified as high availability if more than 50% of respondents indicated that community resources for that activity/skill were adequate; otherwise, the resources were classified as low availability.

Note: (P) Parenting, (CC) Child care, (H) Child health and health care

Figure 3.

Resource availability for high and low priority activities that might address key areas of need for child development and learning, home and child safety, and enrichment activities. Each activity/skill was classified as higher priority if 50% or more respondents who chose a particular general category ranked that activity/skill in the top 3; otherwise, the activity/skill was classified as lower priority. Resources were classified as high availability if more than 50% of respondents indicated that community resources for that activity were adequate; otherwise, the resources were classified as low availability.

Note: (CD) Child development, (S) Home and child safety, (E) Enrichment activities

We examined stratified responses to determine whether priority rankings varied by respondents’ 2-1-1 job category (i.e., I&R specialist, resource manager, center/state director). Because helping resources are often more widely available in densely populated areas, we also examined differences by urban-rural service areas. We found no significant differences for either variable and thus report non-stratified results below.

RESULTS

Six hundred fifty respondents began the survey. Of these, 611 (94%) completed any of the questions about adult needs, and 471 (72%) completed the questions about the needs of children; this latter group is the focus of this study. Respondents represented 2-1-1 helplines in 44 states, Puerto Rico, and one Canadian province. Most respondents were I&R specialists (56%) and worked at 2-1-1 helplines serving an even mix of urban and rural populations (50%) (Table 1). Most I&R specialists (57%) reported speaking with 150 or more callers per week. Most center or state directors (84%) spoke with fewer than 25 callers weekly. The majority of resource managers (52%) reported speaking with 10–24 service agencies or other organizations weekly.

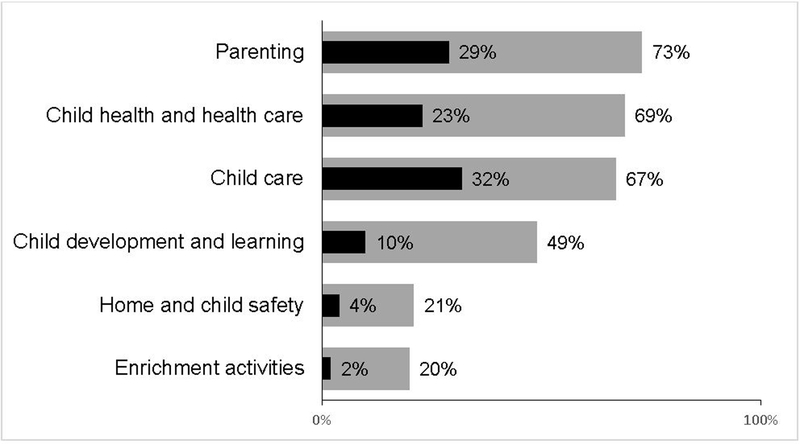

Each respondent selected three high priority general needs for 2-1-1 callers with children. The needs most often selected were parenting (chosen by 73% of respondents), child health and health care (69%), and child care (67%). Examining only respondents’ top choice or “most important priority” of the three selected, child care was ranked most important by 32% of respondents, followed by parenting (29%) and child health and health care (23%). Figure 1 presents these data for all six need areas.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents (N = 471) who chose each category as one of the top 3 priorities (gray bars) and as the top priority (black bars).

Within each need area selected as a priority, respondents identified the three most important dimensions of the need area, as well as the availability of community resources to address that dimension and the acceptability of proactively asking callers about this need (Table 2). Among respondents rating parenting a priority, many reported that coping with stress and negative feelings (selected by 60% of respondents) and managing child behavior (57%) were most important for improving the lives of families with children. Just over half (51%) thought community resources were adequate for coping with stress, and 44% believed resources were adequate for managing child behavior. In nearly all instances, large majorities of respondents reported that they would be comfortable or very comfortable asking 2-1-1 callers about parenting needs.

Among respondents who rated child health and health as a priority, getting health insurance through Medicaid/ CHIP (77%), completing regular well-child check-ups (59%), and finding a good doctor for the family or child (58%) were rated most important. Most respondents (51–74%) believed there were adequate resources available in their communities to address these needs, and nearly all respondents (92–96%) felt comfortable or very comfortable asking callers about these needs.

Among respondents who rated child care a priority, finding high-quality, affordable early child care (85%); finding after-school care or supervision (62%); and finding summer care or supervision for school-age children (51%) were rated most important. Only 35–39% of respondents believed there were adequate resources available in their communities to address these needs. A large majority of respondents (90–94%) felt comfortable or very comfortable asking callers about these needs.

Figures 2 and 3 classify all individual dimensions of the general need areas by respondents’ ratings of importance and availability of community resources to support those dimensions.

DISCUSSION

Recommendations for improving the health and lives of low-income families and children often point to root-cause determinants such as poverty, joblessness, and inequality. These determinants are clearly important, but they are difficult-to-solve problems that require long-term, systemic change. that may not result in short-term improvement in the lives of low-income families and children. This study explored more immediate solutions and identified specific priority needs that could be screened for proactively among low-income parents by medical or social service providers. The study builds on previous work about 2-1-1 helplines (e.g. Boyum et al., 2016; Purnell et al., 2012) by soliciting information directly from 2-1-1 staff about the needs of callers and the resources available in communities.

There was clear consensus among respondents about the highest priority needs faced by low-income families with children. At least two-thirds of respondents rated parenting, child health and health care, and child care as important for improving the lives of low-income callers with children. Large proportions of respondents felt comfortable addressing these topics proactively with 2-1-1 callers. Availability of community resources, however, varied widely across different dimensions of these problems. For example, nearly three-quarters of respondents (74%) believed that their communities had adequate resources to get health insurance for a child through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which provide insurance coverage to the majority of children living in or near poverty in the U.S. (Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, 2017). Far fewer believed there were adequate resources for helping with serious child problems (39%), finding quality, affordable child care (35%), or preventing child obesity (27%).

Respondents believed that addressing parenting and child care needs was at least as important for low-income families as addressing health and health care needs. Given the high correlation between material hardships and children’s physical and mental health, safety, cognitive development, and academic achievement (Gershoff et al., 2007), brief screenings for needs and provision of referrals for domains outside of medicine could substantially alter the life course of children. Contemporary life course health development frameworks posit that exposure to adverse versus supportive experiences at key points in human development may have cumulative effects across the life course (Halfon et al., 2014; Kuh, 2003), launching children on either positive or negative outcome trajectories (Elder & Shanahan, 2006). Prior work has found that child care and parenting resources may be especially important for altering these trajectories and affecting multiple domains of parent and child wellbeing (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014; Child Care Aware, 2015).

Consistent with other work on 2-1-1 (Boyum et al., 2016), our findings suggest that a major barrier to implementing solutions for certain types of needs (e.g., child care) may lie in the availability of helping resources. Findings from this study suggest two broad strategies for action to address needs of low-income families with children. First, for needs that were rated as high priorities and for which there were adequate community resources (Figures 2 and 3), universal proactive screening and referral should be considered. Second, for high priority needs that lack adequate community resources, advocacy efforts are needed to establish, expand, or redirect resources. Our finding that child care resources were generally not perceived to be adequate, for example, suggests further investment in these resources may be needed to help low-income children reach their potential.

This potential lack of resources also means that success of parent connections to resources should be monitored when referrals are given. It is important for clinicians to consider parents’ perceptions of community resources, as well as the trade-offs families may make when seeking help (e.g. balancing need for resources with the desire for privacy) (Dworkin, 2008; Silverstein et al., 2008). In addition, the meaning of “inadequate resources” may vary. In some cases, it could mean that no agencies are addressing a particular need. Alternatively, it could mean that the agencies addressing this need lack sufficient resources. A recent study of health and social service referrals through a state 2-1-1 call center found that 80–90% of callers successfully contacted referrals for their needs, but only about one-third actually received assistance from those organizations or agencies (Boyum et al., 2016).

The finding of a high need for parenting resources is troubling in light of prior work showing that parenting can mediate the relationship between poverty and adverse child outcomes (Gershoff et al., 2007). Food insecurity and other challenges experienced by low-income families may create a level of stress for parents that overshadows their efforts to improve the lives of their children, negatively affecting both parent and child health (Knowles et al., 2015). Evidence-based parenting support programs that aim to reduce parental stress and promote positive parenting exist, but access to them is often limited (Spoth & Redmond, 2000). Our findings suggest that such programs should address specific content such as coping with stress and negative feelings, managing child behavior, and getting help with serious child problems.

Child care was named the highest priority by nearly one-third of respondents, and one of the top three priorities by the majority of respondents. Lack of quality, affordable child care has been well-documented in the U.S. (Gould & Cooke, 2015). Very few children receive the type of high quality child care that produces the best outcomes later in the life course (Child Care Aware, 2015). Difficulty in paying for child care is especially acute for low-income families, but access to child care assistance can help parents maintain stable employment (Child Care Aware, 2015). Our results show that low-income parents are most in need of assistance with finding consistent daily care for young children and school-age children. Clearly, this is an area in which maternal and child health providers and social service agencies must advocate for increased resources. Our findings emphasize that these resources are inadequate in many communities and suggest that enhancing these resources could benefit low-income families.

Recently, “two-generation programs” have sought to address poverty by simultaneously stabilizing and improving the lives of both children and their parents (e.g., Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014). 2-1-1 call centers may be uniquely situated to inform both arms of this approach to intervention because they connect callers (many of whom are also medically underserved) to resources for both parents and children. Collaboration between maternal and child health providers and staff at 2-1-1 or similar agencies could serve to educate practitioners about agency services and community resources. In addition, such collaboration could involve additional training for I&R specialists about maternal and child health priorities, as well as information about assessing and meeting the needs of parents and children simultaneously. Although 2-1-1 staff reported being comfortable raising many potentially sensitive topics with callers, they may also benefit from the development of scripts for raising sensitive issues, as well as education about brief screeners that can be used to identify problems.

The current study has several strengths. Collectively, the respondents to this survey reported interacting with approximately 44,000 callers and 1,400 service agencies every week in their work at an information and referral helpline that serves low-income individuals. This is the first study to capture insights from this unique professional group, and it both validates and extends findings reported elsewhere that were derived from other sources. These findings underscore the promise of 2-1-1 as a means of connecting low-income parents to resources and also suggest that lack of services may be a constraining factor in many communities.

Certain limitations of this study should be noted. Although effort was made to recruit a range of respondents, 2-1-1 staff who completed the survey may differ in systematic ways from staff who did not respond. In addition, these results may not be generalizable to low-income people in areas not served by 2-1-1. Providing respondents with close-ended categories from which to choose may have prevented us from capturing some callers’ needs or from exploring why 2-1-1 staff responded in the manner they did. Respondents’ perceptions of what is most important for helping callers, and their perceptions of available resources, may not accurately reflect the needs of callers or community availability of resources; future work should determine whether social service staff assessments are consistent with more objective measures of resource availability, as well as whether investments in such resources help alleviate child poverty. Finally, survey questions did not ask respondents about the needs of children of different ages (e.g. infants or teenagers). It is possible that priority rankings may have differed had respondents been asked to differentiate between the needs of various age groups.

Prior work has shown that when low-income people’s basic needs are met through referrals, they are more likely to follow through on additional referrals for needs related specifically to health (Thompson et al., 2016). Further study should determine whether meeting the basic needs of parents is associated with their follow-through on child-focused referrals or with reductions in child poverty. In addition, researchers should determine how maternal and child health providers rate priority need areas for their low-income patients. Doing so would help generate a list of consensus priorities for maternal and child health providers and social service providers, which would constitute an important step toward “horizontal integration” of medical and community services (Halfron et al., 2014). A shared agenda could also help maternal and child health providers and social service providers advocate in the policy arena for increased parenting and child care resources both to help low-income families cope with daily challenges and to reduce the prevalence of child poverty (Block et al., 2013). Taken together, this collaborative work could alter the health trajectories of low-income children and improve their daily lives and their outcomes across the life course.

Supplementary Material

Author acknowledgements:

This study was funded by NCI Grant P50 CA095815 (PI: Matthew Kreuter).

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alcaraz KI, Arnold LD, Eddens KS, et al. (2012) Exploring 2-1-1 service requests as potential markers for cancer control needs American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(6): S469–S474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey Foundation (2014) Creating opportunity for families: A two-generation approach. Available at: http://www.aecf.org/resources/creating-opportunity-for-families/ (accessed 12 July 2017).

- Block RW, Dreyer BP, Cohen AR, et al. (2013) An agenda for children for the 113th Congress: Recommendations from the Pediatric Academic Societies Pediatrics, 131(1): 109–119. 10.1542/peds.2012-2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyum S, Kreuter MW, McQueen A et al. (2016). Getting help from 2-1-1: A statewide study of referral outcomes Journal of Social Service Research, 42(3): 402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B (2014) Child poverty: Limiting children’s life chances Journal of Child Health Care 18(1): 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Care Aware of America. (2015). Parents and the high cost of child care: 2015 report. Available at: http://usa.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Parents-and-the-High-Cost-of-Child-Care-2015-FINAL.pdf (accessed 12 July 2017).

- Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Garner AS, et al. (2012) Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health Pediatrics, 129(1): e224–e231. 10.1542/peds.2011-2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Community Pediatrics (2013) Community pediatrics: Navigating the intersection of medicine, public health, and social determinants of children’s health Pediatrics, 131(3): 623–628. 10.1542/peds.2012-3933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daily LS (2012) Health research and surveillance potential to partner with 2-1-1. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(6): S422–S424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin PH (2008) A possible reason for failure to access community services? Pediatrics, 122(6): 1371–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddens K, Kreuter MW and Archer K (2011) Proactive screening for health needs in United Way’s 2-1-1 information and referral service Journal of Social Service Research, 37(2): 113–123. 10.1080/01488376.2011.547445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH and Shanahan MJ (2006) The life course sand human development In: Lerner RM (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development, pp. 665–715). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fierman AH, Beck AF, Chung EK, et al. (2016) Redesigning health care practices to address childhood poverty Academic Pediatrics 16(3): S136–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, et al. (2015) Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: A cluster RCT Pediatrics 135(2): e296–e304. 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgetown University Health Policy Institute (2017) United States: Snapshot of children’s health care coverage Available at https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ccs_factsheet_unitedstates.pdf (accessed 5 February 2018)

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, et al. (2007) Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development Child Development 78(1): 70–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E and Cooke T (2015) High quality child care is out of reach for working families. Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief, 404 Available at: http://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/ (accessed 12 July 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Hair NL, Hanson JL, Wolfe BL, et al. (2015) Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement JAMA Pediatrics 169(9): 822–829. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N and Hochstein M (2002) Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research Milbank Quarterly 80(3): 433–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, et al. (2014) Lifecourse health development: Past, present and future Maternal and Child Health Journal 18(2): 344–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Granga MR and Koball H (2017) Basic facts about low-income children: Children under 6 years, 2015. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; Available at: http://www.nccp.org/publications/pdf/text_1172.pdf (accessed 12 July 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Knowles M, Rabinowich J, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. (2015) “Do you wanna breathe or eat?”: Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Maternal and Child Health Journal 20(1): 25–32. 10.1007/s10995-015-1797-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Eddens KS, Alcaraz KI, et al. (2012). Use of cancer control referrals by 2-1-1 callers American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(6): S425–S434. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D (2003) Life course epidemiology Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 57(10): 778–783. 10.1136/jech.57.10.778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Fertig AR, and Allison PD (2011) Physical and mental health, cognitive development, and health care use by housing status of low-income young children in 20 American cities: A prospective cohort study American Journal of Public Health 101(S1): S255–S261. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullon S, McKinlay B, Yager J, et al. (2015) Developing indicators of service integration for child health: Perceptions of service providers and families of young children in a region of high need in New Zealand. Journal of Child Health Care, 19(1), 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell JQ, Kreuter MW, Eddens KS, et al. (2012) Cancer control needs of 2-1-1 callers in Missouri, North Carolina, Texas, and Washington Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23(2): 752–767. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Herrera P, Wold CM, et al. (2012) Developmental and autism screening through 2-1-1: Reaching underserved families American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(6 suppl 5): S457–63. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Lamberto J, DePeau K, et al. (2008) “You get what you get”: Unexpected findings about low-income parents’ negative experiences with community resources Pediatrics 122(6): e1141–e1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Stagnitti K, Lewis AJ, et al. (2015). The views of parents who experience intergenerational poverty on parenting and play: a qualitative analysis Child: Care, Health and Development 41(6): 873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R and Redmond C (2000) Research on family engagement in preventive interventions: Toward improved use of scientific findings in primary prevention practice Journal of Primary Prevention 21(2): 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Kreuter MW and Boyum S. (2016) Promoting health by addressing basic needs: Effect of problem resolution on contacting health referrals. Health Education & Behavior 43(2): 201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH, et al. (2005) Parental awareness of health and community resources among immigrant families Maternal and Child Health Journal 9(1): 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.