Abstract

While the national HIV infection rate is decreasing, the highest rates of infections continue among men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly minority MSM. It is important to understand attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors surrounding HIV prevention methods, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In the present study, we created a snapshot of the PrEP continuum of care and identified participant demographic and sources of PrEP awareness factors that were associated with PrEP initiation. Data were collected using anonymous paper–based surveys employing a venue intercept procedure. A total of 188 HIV–negative men completed the survey at Miami Gay Pride 2018. Participants answered questions regarding demographics, PrEP use, and sources of PrEP awareness. The sample was majority Hispanic (55.4%), gay (83.0%), and single (57.7%). The constructed PrEP continuum revealed that a low proportion of those identified as PrEP naïve (n = 143) for HIV infection had PrEP interest (49/143). Moreover, among those who initiated PrEP (n = 45), a high proportion were retained in a PrEP program (37/45), with approximately half achieving medication adherence (25/45). Age group, PrEP knowledge, and source of PrEP awareness were all significantly associated with PrEP initiation. In areas with high HIV infection rates, studies like these offer crucial insight on how public health practitioners should proceed in the goal of decreasing HIV transmission rates. More research is needed to increase PrEP uptake and adherence.

Keywords: PrEP, HIV prevention, Surveillance, MSM

Introduction

In 2017, 38,281 people in the United States (US) were newly diagnosed with HIV [1]. While the national HIV infection rate decreased from 2012 to 2017, the highest number of infections continues to occur in men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly minority MSM [1]. Florida is no exception to these trends, where from 2013-2017, the highest increases of new HIV infections occurred amongLatino and Black MSM (37.4% and 20.0%, respectively) [2]. In response to these rising rates of HIV infection, it becomes important to understand methods in HIV prevention, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

PrEP, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for the prevention of HIV [3], is more than 90% effective when taken every day [4, 5]. However, initial uptake of this biomedical prevention strategy has been slow [6]. In 2012, the first-year post-FDA approval, there were 8,768 PrEP users [7]. In 2017, there were a total of 100,282 PrEP users and 7.6% of those users were in Florida.[7]. An additional 1.1 million Americans are estimated to be candidates for PrEP including 300,000 Latinos [8]. Of the Latino population that could benefit from PrEP (greater than 220,000 are estimated to be Latino MSM), only 3% were prescribed PrEP [8]. Past research suggests that if PrEP were provided to 80% of MSM at risk of HIV, approximately 40% of new HIV infections could be averted in the following 10 years [9].

One suggested mechanism in the tracking of PrEP initiation is known as the PrEP continuum of care. To quantify and describe at which level of care PrEP needs are being met, several PrEP care continuums have been developed [10–13]. The PrEP continuum developed by Liu et al. (2014) describes a continuum based on community metrics, with steps including the following: (1) At risk for HIV infection, (2) Identified as PrEP candidate, (3) Interested in PrEP, (4) Linked to PrEP Program, (5) Initiated PrEP, (6) Retained in PrEP program, and (7) Achieve adherence and persistence [10]. (Fig. 1) Our study utilizes a modified version of the PrEP continuum developed by Liu et al. (2014) to model the responses provided by our sample

Fig. 1.

The PrEP continuum of care

A community level assessment of PrEP awareness among MSM descriptively demonstrated that as PrEP awareness increased so did PrEP uptake [14]. Common sources of PrEP awareness in research have highlighted the media, internet, friends, primary care providers, and sex partners [15, 16]. Previous research has pointed to age [17], race [17, 18], ethnicity [17–19], education [20], income [21], and location [18, 22] as significant demographic predictors and number of sexual partners [14, 19, 20], condom use [14, 21–23], STI history [14, 20–22], and drug use (i.e., methamphetamine and poppers) [14, 19, 21] as significant behavioral predictors of PrEP uptake. Previously identified health belief barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence include the following: health concerns surrounding the short-term and long-term use of PrEP, PrEP’s impact on drug resistance, and PrEP efficacy [24] in addition to cost, access, and adherence to the PrEP regimen [22, 25].

Our study had two aims. Our first aim was to describe the PrEP continuum of care in Pride attending, HIV-negative men. Our second aim was to identify key demographic factors and sources of PrEP awareness that are correlated with PrEP initiation. Identifying demographic and sources of PrEP awareness will help inform public health practice on which populations they may be missing in their current PrEP messaging and what modes of communication may lead to the best outcomes of PrEP initiation.

Methods

Setting and Procedures

Data were collected during Miami Beach Gay Pride 2018. To be eligible for the survey, participants had to be male sex, 18 years or older, and must have been aware of PrEP prior to being approached by recruiters. We collected data using anonymous, paper-based surveys employing a venue intercept procedure reported in previous studies on similar topics [26]. Trained recruiters approached all potentially eligible participants (i.e., cis-gendered-appearing men and appearance of ≥ 18 years of age) that passed by to reduce selection bias. Once participants crossed, the recruiter asked if participants had ever heard of PrEP. If yes, participants were asked questions assessing their potential eligibility status for the study and if they had ever initiated PrEP. If potential participants were traveling with a group, group members who appeared to fit recruitment criteria were also approached. If eligible, participants were invited to complete a written survey about PrEP beliefs and experiences that would take approximately 5–7 min to complete. Participants were given slightly different surveys based on whether they had ever initiated PrEP. In order to probe variables that were dependent on participant’s use of PrEP, non-PrEP users were asked more questions about barriers to PrEP and PrEP interest, and PrEP users were asked questions about adherence and where they receive their PrEP. Participants were compensated $5 for completing the survey. If ineligible, research staff thanked the participant for their time, but did not reveal reasons for ineligibility to deter false reporting.

To keep records of recruitment, study staff followed recruiters to record the number of participants who agreed/disagreed to participate in the study and how many participants were ineligible for the study, and if so, for what reasons. This study was approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sociodemographic

Participants were asked to provide their age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, do not know/questioning, other), education level (1 = ≤ high school to 4 = graduate level degree), relationship status, and ZIP code. Age was asked using an open response and converted to condensed categories used by Federal and State reports [1, 2]. Race and ethnicity were asked separately, but due to the high correlation of being of White race and Hispanic ethnicity, all participants that identified as Hispanic were classified as Hispanic regardless of race. The question regarding relationship status was inclusive of findings in past research on gay couples [27–29], so the ability to indicate an open relationship or an exclusive relationship was available. Three participants identified as a non-male gender; thus, gender was not used as a predictor variable in our models. ZIP code was utilized to create a binary variable of those living in Florida (1) and those not living in Florida (0).

Frequency of Alcohol and Marijuana Use

Alcohol use frequency was assessed using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuses and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recommended question, “During the last 12 months, how often did you usually have any kind of drink containing alcohol? [30]” Following the NIAAA format, marijuana use frequency was assessed using the question, “During the last 12 months, how often did you use marijuana?” For both alcohol and marijuana use frequency, answers could range from every day to never in the past 12 months. Alcohol use frequency was stratified into three categories: ≥ weekly, < weekly and ≥ monthly, and < monthly. Marijuana use frequency was stratified into three categories: ≥ weekly, < weekly and > never, and never.

PrEP Continuum of Care

We assembled our PrEP continuum of care using 5 of the 7 pillars of the PrEP continuum proposed by Liu et al. (2014), including the following: (1) At risk for HIV infection (modified to PrEP Naïve), (2) Interested in PrEP, (3) Initiated PrEP, (4) Retained in PrEP program, (5) Achieve adherence and persistence. We utilized a modified version of this model to maintain the brevity and avoid sensitive sexual behavior topics as to not overwhelm participants which we hoped would increase study participation interest. Below are more detailed descriptions of each pillar’s metric and how the self-reported information was collected on eligible participants.

PrEP Naïve(1)

Classified as the proportion of participants that verbally responded “No” to the question, “Have you ever used PrEP?”

Interested in PrEP(2)

Classified as the proportion of participants that verbally responded “No” to the question “Have you ever used PrEP?” and responded “Yes” to the question, “Are you interested in starting PrEP?”

Initiated PrEP(3)

Classified as the proportion of participants that verbally responded “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever used PrEP?”

Retained in PrEP Program(4)

Classified as the proportion of participants that verbally responded “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever used PrEP?” and responded, “I am currently on PrEP and have a PrEP provider” to the question, “Please mark the following statement that applies to your PrEP care.”

Achieve Adherence and Persistence(5)

Classified as the proportion of participants that verbally responded “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever used PrEP?” and responded, “I am currently on PrEP and have a PrEP provider” to the question, “Please mark the following statement that applies to your PrEP care,” and indicated 95% PrEP adherence calculated from the question, “Approximately how many PrEP pills have you missed in the past month?”

Source of PrEP Awareness and PrEP Knowledge

The source of participant PrEP awareness was assessed categorically (i.e., primary care provider (PCP), newspaper, social media), using the question “Where did you first learn about PrEP?” PrEP knowledge was assessed by using an 8-item True/False scale created by the investigators. Questions were appropriately coded where a correct answer to an item scored 1 and incorrect value scored 0. Scores could range from 0 to 8, where higher scores indicated higher PrEP knowledge. Some of the items used in this scale included the following: “PrEP is only for men”, “PrEP is more than 90% effective when taken as directed”, and “PrEP is a pill that you take every day.”

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS (v9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Descriptive data were used to report sample characteristics, information on the source of PrEP awareness, and scores from the PrEP knowledge scale. Additionally, a graph was constructed to display the PrEP continuum. Crude logistic regression models were conducted to assess the relationship of demographic factors, source of PrEP awareness, and PrEP knowledge on the odds of ever initiating PrEP. All variables p < 0.20 in the crude regression were added to the final adjusted logistic regression analysis, with α < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive Demographics

Demographic and PrEP knowledge characteristics for the participants are displayed in Table 1. Our sample was majority Hispanic (57.9%), gay (83.0%), single (57.7%), and Florida residents (79.7%). The age ranged from 18 to 66 years with a mean age of 29.6 ± 9.2 years. The most common sources of PrEP awareness were friends (25.7%) and social media (23.0%). PrEP knowledge ranged from 1 to 8 with a mean score of 6.3 ± 1.7 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Miami Gay Pride 2018 sample demographics

| Variable name | Study sample (N = 188) |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 63 (33.5%) |

| 25–29 | 57 (30.3%) |

| 30–39 | 40 (21.3%) |

| 40–49 | 19 (10.1%) |

| 50 + | 9 (4.8%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 49 (27.5%) |

| Black | 21 (11.8%) |

| Hispanic | 103 (57.9%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5 (2.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Cis-gender | 185 (98.4%) |

| Transgender | 0 (0.0%) |

| Othera | 3 (1.6%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 156 (83.0%) |

| Otherb | 32 (17.0%) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High school degree | 17 (9.4%) |

| Some college | 72 (38.3%) |

| 4-year degree | 58 (30.9%) |

| Graduate degree | 41 (21.8%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 108 (57.7%) |

| Exclusive relationship | 47 (25.1%) |

| Open relationship | 16 (8.6%) |

| Other | 16 (8.6%) |

| Florida resident | |

| No | 35 (20.4%) |

| Yes | 137 (79.7%) |

| Frequency of marijuana use | |

| ≥ Weekly | 46 (24.6%) |

| > Never, < weekly | 54 (28.9%) |

| Never | 87 (46.5%) |

| Frequency of alcohol use | |

| ≥ Weekly | 120 (64.2%) |

| ≥ Monthly, < weekly | 50 (26.7%) |

| < Monthly | 17 (9.1%) |

| First heard of PrEP | |

| Social media | 43 (23.0%) |

| Internet | 30 (16.0%) |

| Friends | 48 (25.7%) |

| Doctor | 26 (13.9%) |

| Otherc | 39 (21.0%) |

| PrEP knowledge | 6.33 ± 1.70 |

aOther includes the following: non-binary and femme gender identification

bOther includes the following: heterosexual, bisexual, questioning/do not know, and other responses

cOther includes the following: newspapers or magazines, sex partners, or other responses

PrEP Continuum Demographics

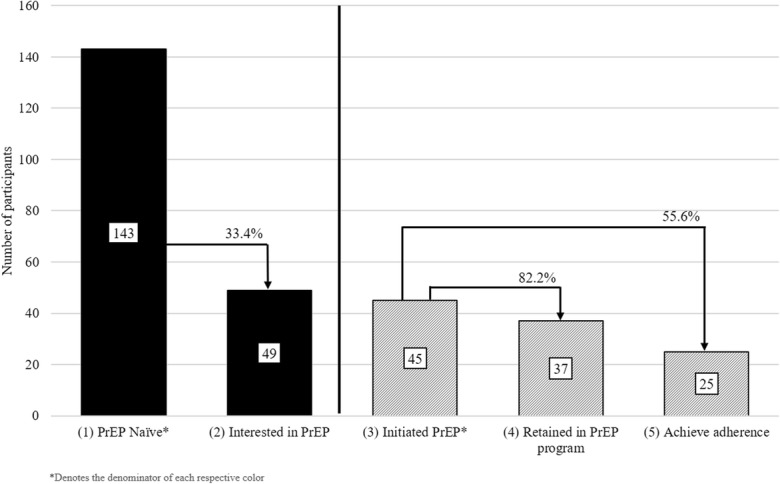

Of the 379 potential participants approached for our study, 355 were eligible (93.7%) as they previously were aware of PrEP. Of those eligible, 200 were successfully recruited into the study (56.3%). Some reasons for non-participation included not having time to participate and not wanting to be associated with a study on PrEP. Those who identified as living with HIV in the survey (n = 12) were removed from analysis as they are not eligible to receive PrEP, leaving our final sample at n = 188. From our total sample, 143 participants were identified as PrEP naïve(1) and 45 participants were identified as initiating PrEP(3). Of those identified as PrEP naïve (1), 49 participants (34.3%) were identified as interested in PrEP(2). Of those who initiated PrEP(3), 37 participants (82.2%) were identified as retained in a PrEP program(4), and 25 participants (55.6%) were identified as achieved adherence and persistence(5) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Surveillance of the PrEP Continuum of Care: Miami Pride 2018

Crude Logistic Regression Model

In the crude logistic regression model, those aged between 25–29, 30–39, and 40–49 years had significantly higher odds of ever initiating PrEP than those aged between 18 and 24 years (crude odds ratio (COR) = 2.86; p = 0.036, COR = 4.80; p = 0.002, and COR = 3.69; p = 0.040, respectively). Additionally, non-gay-identifying men had significantly lower odds of ever initiating PrEP than those who identified as gay (COR = 0.18; p = 0.021). PrEP knowledge was also seen as a significant variable in the crude regression, where each unit increase in PrEP knowledge showed an increased odds of ever initiating PrEP (COR = 2.06; p < 0.001). Moreover, the source of PrEP awareness was seen as significant, where first hearing about PrEP from a friend (COR = 4.02; p = 0.024) or from a PCP (COR = 18.42; p < 0.001) had significantly higher odds of ever initiating PrEP than those who first became aware of PrEP through social media. Although relationship status and education level were not seen as statistically significant, their significance levels were p ≤ 0.20 and they were therefore included in the adjusted model. Race/ethnicity, frequency of alcohol use, frequency of marijuana use, and Florida residence were not found to be significant at p ≤ 0.20 and were dropped from the final model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted logistic regression models of sample characteristics on ever initiating PrEP

| Variable name | Crude odds ratio | Confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 25–29 | 2.86 | 1.07, 7.63 | 3.23 | 0.81, 12.86 |

| 30–39 | 4.80 | 1.74, 13.22 | 7.75 | 1.65, 36.44 |

| 40–49 | 3.69 | 1.06, 12.84 | 2.63 | 0.40, 17.10 |

| 50 + | 2.29 | 0.39, 13.24 | 2.50 | 0.20, 32.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | – | – |

| Black | 0.87 | 0.26, 2.84 | – | – |

| Hispanic | 0.80 | 0.36, 1.74 | – | – |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.69 | 0.07, 6.78 | – | – |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Gay | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Othera | 0.18 | 0.04, 0.77 | 0.38 | 0.07, 2.06 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High school degree | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some college | 1.97 | 0.41, 9.59 | 2.54 | 0.34, 19.26 |

| 4-year degree | 3.38 | 0.70, 16.33 | 2.69 | 0.34, 21.59 |

| Graduate degree | 2.42 | 0.47, 12.45 | 1.41 | 0.17, 11.49 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Exclusive relationship | 0.50 | 0.20, 1.24 | 0.33 | 0.08, 1.39 |

| Open relationship | 0.66 | 0.18, 2.49 | 1.15 | 0.22, 6.13 |

| Other | 2.22 | 0.76, 6.53 | 1.14 | 0.20, 6.48 |

| Florida resident | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | – | – |

| Yes | 0.67 | 0.29, 1.50 | – | – |

| Frequency of marijuana use | ||||

| Never | Ref. | Ref. | – | – |

| < Weekly, > never, | 0.84 | 0.38, 1.89 | – | – |

| ≥Weekly | 0.93 | 0.40, 2.13 | – | – |

| Frequency of alcohol use | ||||

| < Monthly | Ref. | Ref. | – | – |

| < Weekly, ≥ monthly | 0.76 | 0.17, 3.34 | – | – |

| ≥ Weekly | 1.92 | 0.52, 7.11 | – | – |

| First heard of PrEP | ||||

| Social media | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Internet | 1.50 | 0.34, 6.54 | 2.88 | 0.47, 17.50 |

| Friends | 4.02 | 1.21, 13.36 | 4.52 | 0.95, 21.43 |

| Primary care provider (PCP) | 18.42 | 4.98, 68.14 | 16.34 | 2.68, 99.71 |

| Otherb | 1.72 | 0.45, 6.61 | 1.42 | 0.22, 9.07 |

| PrEP knowledge | 2.06 | 1.42, 3.00 | 1.67 | 1.09, 2.53 |

p < 0.05–italicized

aOther includes the following: heterosexual, bisexual, questioning/do not know, and other responses

bOther includes the following: newspapers or magazines, sex partners, or other responses

Adjusted Logistic Regression Model

In the adjusted logistic regression model, those aged between 30 and 39 years had significantly higher odds of ever initiating PrEP than those aged 18–24 (AOR = 7.75;p = 0.010); whereas being aged 25–29 and 40–49 were not statistically significant in the adjusted model (AOR = 3.23; p = 0.096 and AOR = 2.63; p = 0.312, respectively). PrEP knowledge also remained significant in the adjusted regression, where each unit increase in PrEP knowledge showed an increased odds of ever initiating PrEP (AOR = 1.67; p = 0.019). Additionally, becoming aware of PrEP from a PCP had significantly higher odds of ever initiating PrEP than those who became aware of PrEP through social media (AOR = 16.34; p = 0.003). Becoming aware of PrEP from a friend, sexual orientation, relationship status, and education level were not statistically significant in the adjusted logistic regression models (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this project is the first to use a PrEP continuum of care construct in a non-clinical sample. Moreover, the recruited sample was majority Latino (55.4%), which is novel as the majority of research on PrEP uptake has been conducted in majority white MSM. [17–20, 23] This finding is significant as this could provide a snapshot of what diverse men are thinking and doing about PrEP in a non-clinical sample. Our constructed PrEP continuum of care revealed that those identified as PrEP naïve(1) had a relatively low proportion of interest in PrEP(2). Our construct also showed that among those who initiated PrEP(3), a high proportion were retained in a PrEP program(4), and about half were achieving 95% PrEP adherence. These findings demonstrate the feasibility of constructing a PrEP continuum of care in larger, cross-sectional studies conducted in the future.

Our study also found significant differences in demographic and sources of PrEP awareness factors, and their correlation with PrEP initiation. Being aged 30–39 (vs aged 18–24), having higher PrEP knowledge, and becoming aware of PrEP from a care provider (vs social media) were all significant predictors of whether someone has ever initiated PrEP. Only one other identified study has shown age as significant in multivariate models [17] while other past research has not shown age to be a significant factor in PrEP uptake [14, 18, 19, 21–23, 31]. This finding is mixed as PrEP initiation is high among the second largest HIV incident age group (aged 30–39) between 2012 and 2016 (27.8% increase) [2], yet there were no significant differences seen in those aged 25–29 (vs aged 18–24), the highest age group increase in HIV between the same years (47.7% increase) [2]. Additionally, this finding could highlight a potential future gap in PrEP initiation in those aged 18–24 as they age and enter the highest risk age category. These findings suggest that community organizations should monitor levels of PrEP initiation in key populations to more immediately target those at highest risk of HIV, and preventatively target those who will be joining the highest HIV–risk group in the future. Finding factors correlated to the initiation of PrEP care is an important addition to the constructed PrEP continuum of care as these findings can help inform more tailored PrEP interventions.

Knowing the source of PrEP awareness and its difference in PrEP initiation could help inform where future advertisement funds should be spent. Our study found becoming aware of PrEP from a PCP yielded higher odds of ever using PrEP in comparison to becoming aware of PrEP through social media. This finding may be a reflection of increased inclusivity of our sample’s providers and its importance in the improvement in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities, including HIV prevention [32, 33]. Past research has shown a significant difference in PrEP initiation between those who have had HIV prevention discussions with their care provider and those who have not [23]. More research needs to be done on the awareness and willingness of PrEP prescription and LGBT care inclusivity among care providers and its effects on PrEP initiation among patients.

Our study also found that increased PrEP knowledge was correlated with increased odds of ever initiating PrEP. This finding mirrors past research that has shown higher PrEP initiation among those with past PrEP knowledge [34]. This could imply that interventions that aim to improve the practical understanding of PrEP through education could be useful in improving PrEP uptake. Gaps remain in the literature on the effects of PrEP knowledge on PrEP acceptability and initiation and the presence of a standardized tool that measures PrEP knowledge. More research needs to be done to develop a standardized tool for PrEP knowledge that is tested among various high-risk populations.

Limitations

Firstly, our study used a convenience sampling method of men at Miami Gay Pride which could mean that our sample only consisted of men comfortable enough to be seen at a gay associated event. Due to PrEP’s high association to gay culture, we infer that men who are not comfortable with their sexuality may have greater barriers to PrEP than the men in this study. Secondly, we only approached people that looked like they fit recruitment criteria (i.e., cis-gendered men) which limited the number of non-cis-gender individuals, who are also at high risk for HIV, considered for this study. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we were unable to infer causality between PrEP initiation and the factors that were found to be correlated with PrEP initiation. However, the correlations that were found should be explored and further examined in future studies. Longitudinal studies that look at the effects of care provider–driven PrEP education should be undertaken to determine if the social variables found as significant in this study are causal. The classification of participants into the PrEP continuum of care were based on self-report and could have been prone to reporting bias. Moreover, the PrEP knowledge scale utilized in this study has not yet been validated and was used because there are currently no existing validated scales that measure PrEP knowledge. Finally, researchers were unable to gather information on sexual risk and therefore some of those classified as PrEP naïve may not be appropriate for PrEP (i.e., in a sexually monogamous relationship, not sexually active, consistent condom use). Due to the lack of privacy at a Gay Pride event, researchers wanted to save participants from answering questions on sensitive topics such as sexual behavior and some substance use. Despite the study’s limitations, we were able to show the feasibility of the surveillance of the PrEP continuum of care in a diverse, non-clinical sample.

Recommendations

In order to address the HIV burden in areas with high HIV incidence, it becomes increasingly important to tailor messaging to those most at risk for HIV. Based on our modeling of the PrEP continuum of care among Pride-attending HIV-negative men, researchers suggest exploring a transition from making people aware of PrEP to interventions that target interest in PrEP as only 34.3% of people PrEP naïve(1) were interested in PrEP(2). Additionally, researchers suggest future studies that examine the low achievement of PrEP adherence and persistence as 44.4% of people who had initiated PrEP(3) were not currently using PrEP(4) or not reaching 95% PrEP adherence(5). Based on our demographic findings from the models and stratified HIV infection rate data in South Florida, this intervention should more closely target those aged 18–24, aged 25–29, and people that identify as racial and ethnic minorities. Based on our findings on the source of PrEP awareness, we suggest that new interventions should prioritize increasing care provider PrEP awareness and knowledge because our findings show that when a care provider is the source of PrEP awareness, participants had higher odds of PrEP initiation. Researchers at the University of California San Francisco are conducting an intervention study that will increase primary care provider’s knowledge and willingness to prescribe PrEP [35]. There are two main components to the intervention, including the following: (1) the implementation of PrEP-Rx, which is an Internet-based PrEP management tool and (2) the implementation a clinical support staff serving as a PrEP coordinator [35]. In addition to future interventions, more research surrounding PrEP initiation in different settings and populations in high HIV incident areas in the U.S. is needed, particularly among transgender women.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated the feasibility of measuring PrEP-associated variables that can be modeled by a PrEP continuum of care. Our study identified several major gaps in the PrEP continuum of care among Pride attending, HIV-negative men and identified important correlates in PrEP initiation within our sample. Combined, these findings could be used to develop future intervention strategies. PrEP initiation interventions should focus on PrEP education guided by health care providers of young racial and ethnic minority patients. Studies like these that focus on the importance of PrEP in areas with high-incident HIV infections in the U.S. could offer crucial insight on how public health practitioners should proceed in the goal of decreasing rates of HIV incidence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Isis Monzon for her assistance in the data collection of this study. We would also like to acknowledge the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant number 1R01DA042069-01A1 (PI:Cook) for funding this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Angel B. Algarin, Phone: (330) 272-4294, Email: aalga016@fiu.edu

Cho Hee Shrader, Email: cxs939@miami.edu.

Chintan Bhatt, Email: chintan.bhatt@fiu.edu.

Benjamin T. Hackworth, Email: Bhackworth@unitedwaybroward.org

Robert L. Cook, Email: cookrl@ufl.edu

Gladys E. Ibañez, Email: gibanez@fiu.edu

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2017. 2018; 29; Retrieved From: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

- 2.Florida Department of Health. Epidemiologic profile report. 2018; Retrieved From: http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/epi-profiles/index.html. Accessed 30 Apr 2019.

- 3.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection. 2012; Retrieved From: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112032741/http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm312210.htm. Accessed 15 Sept 2018.

- 4.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, Goicochea P, Casapía M, Guanira-Carranza JV, Ramirez-Cardich ME, Montoya-Herrera O, Fernández T, Veloso VG, Buchbinder SP, Chariyalertsak S, Schechter M, Bekker LG, Mayer KH, Kallás EG, Amico KR, Mulligan K, Bushman LR, Hance RJ, Ganoza C, Defechereux P, Postle B, Wang F, McConnell J, Zheng JH, Lee J, Rooney JF, Jaffe HS, Martinez AI, Burns DN, Glidden DV, iPrEx Study Team Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, Sullivan AK, Clarke A, Reeves I, Schembri G, Mackie N, Bowman C, Lacey CJ, Apea V, Brady M, Fox J, Taylor S, Antonucci S, Khoo SH, Rooney J, Nardone A, Fisher M, McOwan A, Phillips AN, Johnson AM, Gazzard B, Gill ON. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantell Joanne E., Sandfort Theo G.M., Hoffman Susie, Guidry John A., Masvawure Tsitsi B., Cahill Sean. Knowledge and Attitudes About Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among Sexually Active Men Who Have Sex with Men and Who Participate in New York City Gay Pride Events. LGBT Health. 2014;1(2):93–97. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AIDSVu. Tools & Resources: Datasets. Retrieved From: https://aidsvu.org/resources/#/. Accessed 30 Apr 2019.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevention pill not reaching most Americans who could benefit – especially people of color. NCHHSTP Newsroom 2018; Retrieved From: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2018/croi-2018-PrEP-press-release.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2018.

- 9.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, Smith A, Goswami P, Sanchez J. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu A, Colfax G, Cohen S, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV prevention: proposal for a PrEP cascade. 2012; Retrieve From: http://iapac.org/AdherenceConference/presentations/ADH7_80040.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2018.

- 11.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, Sanchez T, del Rio C, Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1590–1597. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, Mayer KH, Mimiaga M, Patel R, Chan PA. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS. 2017;31(5):731–734. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield THF, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2017;74(3):285–292. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood JE, Buskin SE, Dombrowski JC, Kern DA, Barash EA, Katz DA, Golden MR. Dramatic increase in preexposure prophylaxis use among MSM in Washington state. AIDS. 2016;30(3):515–519. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauermeister JA, Meanley S, Pingel E, Soler JH, Harper GW. PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men in the United States. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):520. doi: 10.2174/1570162X12666140129100411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolezal C, Frasca T, Giguere R, Ibitoye M, Cranston RD, Febo I, Mayer KH, McGowan I, Carballo-Diéguez A. Awareness of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is low but interest is high among men engaging in condomless anal sex with men in Boston, Pittsburgh, and San Juan. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(4):289–297. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snowden JM, Chen Y, McFarland W, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of users of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2014 in a cross-sectional survey: implications for disparities. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(1):52–55. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, Doblecki-Lewis S, Postle BS, Feaster DJ, Matheson T, Trainor N, Blue RW, Estrada Y, Coleman ME, Elion R, Castro JG, Chege W, Philip SS, Buchbinder S, Kolber MA, Liu AY. High interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV-infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439–448. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landovitz RJ, Tseng C, Weissman M, et al. Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):729–739. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer KH, Oldenburg CE, Novak DS, Elsesser SA, Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ. Early adopters: correlates of HIV chemoprophylaxis use in recent online samples of US men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1489–1498. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holloway IW, Dougherty R, Gildner J, Beougher SC, Pulsipher C, Montoya JA, Plant A, Leibowitz A. Brief report: PrEP uptake, adherence, and discontinuation among California YMSM using geosocial networking applications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):15–20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, Hosek S, Mosquera C, Casapia M, Montoya O, Buchbinder S, Veloso VG, Mayer K, Chariyalertsak S, Bekker LG, Kallas EG, Schechter M, Guanira J, Bushman L, Burns DN, Rooney JF, Glidden DV, iPrEx study team Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Mitty JA, White JM, Mayer KH. Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York city. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(4):248–254. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, Eddy JA, Halkitis PN. Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: the P18 study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(2):112–125. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, Maksut J. Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among Black and White men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1236–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1690-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford JM, Rodden P, Kippax S, van de Ven P. Negotiated safety and other agreements between men in relationships: risk practice redefined. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(3):164–170. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoff CC, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Relationship characteristics and motivations behind agreements among gay male couples: differences by agreement type and couple serostatus. AIDS Care. 2010;22(7):827–835. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with HIV risk among a sample of gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):404–411. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Recommended alcohol questions. 2003; Retreived From: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions. Accessed 15 Sept 2018.

- 31.Chan Philip A, Mena Leandro, Patel Rupa, Oldenburg Catherine E, Beauchamps Laura, Perez-Brumer Amaya G, Parker Sharon, Mayer Kenneth H, Mimiaga Matthew J, Nunn Amy. Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19(1):20903. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenway Institute. Building patient-centered medical homes for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients and families. 2016; Retrieved From: https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/Building-PCMH-for-LGBT-Patients-and-Families.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

- 33.Landry J. Delivering culturally sensitive care to LGBTQI patients. J Nurse Pract. 2017;13(5):342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2016.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, Cohan D, Weber S, Sachdev D, Buchbinder S. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saberi Parya, Berrean Beth, Thomas Sean, Gandhi Monica, Scott Hyman. A Simple Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Optimization Intervention for Health Care Providers Prescribing PrEP: Pilot Study. JMIR Formative Research. 2018;2(1):e2. doi: 10.2196/formative.8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]