Abstract

RNA replicons are a promising platform technology for vaccines. To evaluate the potential of lipid nanoparticle-formulated replicons for delivery of HIV immunogens, we designed and tested an alphavirus replicon expressing a self-assembling protein nanoparticle immunogen, the glycoprotein 120 (gp120) germline-targeting engineered outer domain (eOD-GT8) 60-mer. The eOD-GT8 immunogen is a germline-targeting antigen designed to prime human B cells capable of evolving toward VRC01-class broadly neutralizing antibodies. Replicon RNA was encapsulated with high efficiency in 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP)-based lipid nanoparticles, which provided effective delivery in the muscle and expression of luciferase lasting ∼30 days in normal mice, contrasting with very brief and low levels of expression obtained by delivery of equivalent modified mRNA (modRNA). eOD-GT8 60-mer-encoding replicons elicited high titers of gp120-specific antibodies following a single injection in mice, and increased levels of antigen-specific germinal center B cells compared with protein immunization. Immunization of transgenic mice expressing human inferred-germline VRC01 heavy chain B cell receptors that are the targets of the eOD antigen led to priming of B cells and somatic hypermutation consistent with VRC01-class antibody development. Altogether, these data suggest replicon delivery of Env immunogens may be a promising avenue for HIV vaccine development.

Graphical Abstract

Self-replicating RNAs derived from alphaviruses have high potential for vaccine applications. Utilizing lipid nanoparticle-formulated RNA replicons as a vaccine platform to deliver self-assembling protein immunogens, Melo et al. demonstrate robust anti-HIV Env antibody production and significantly improved antigen-specific B cell activation in vaccinated mice when compared with protein immunization.

Introduction

Despite the availability of antiretroviral drugs, HIV infection remains a pandemic that will be controlled only by the development of a successful prophylactic vaccine.1, 2 A protective vaccine against HIV will likely need to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs), antibodies capable of recognizing highly conserved epitopes on the viral glycoprotein 140 (gp140) envelope spike that enable neutralization of the diverse strains of circulating virus.3, 4 Elicitation of bnAbs by vaccination has not yet been achieved despite intense research in the field because of many factors, including the shielding of epitopes on the virus by a dense layer of diverse glycans, intrinsic instability of the native envelope structure, and high mutability of much of the envelope sequence, to name a few.3, 4, 5

One strategy in preclinical development to promote the development of broadly neutralizing responses is to guide the initiation of the B cell response through so-called germline-targeting (GT) immunogens.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 GT antigens are designed to optimally engage human naive precursor B cells expressing specific lineages of B cell receptors (BCRs) known to be required for bnAbs targeting specific sites on gp140. One attractive target epitope on gp120 amenable to such an approach is the CD4 binding site. The CD4 binding site is recognized by a potent bnAb, VRC01, which is representative of a class of antibodies that share structural and genetic characteristics enabling recognition of this epitope on diverse viral strains, including usage of VH1-2 heavy chains and a short 5-amino acid CDR L3 loop.13, 14, 15 We have previously described a series of gp120 outer domain GT immunogens (GT engineered outer domains [eOD-GTs]) designed to engage B cells expressing germline BCRs of the VRC01 antibody class and initiate somatic hypermutation toward VRC01-like bnAbs. To promote responses to these immunogens, we multimerized them via fusion to a bacterial protein, lumazine synthase, which self-assembles to form an icosahedral nanoparticle displaying 60 copies of the eOD-GT antigen (eOD-GT8 60-mer).8 Recombinant eOD-GT8 60-mer protein nanoparticles activate naive B cells expressing VRC01 precursors in human inferred-germline BCR knockin mice,6, 7, 16 wild-type mice into which human inferred-germline B cells have been adoptively transferred,15 human VH gene knockin mice,17, 18 and human immunoglobulin loci transgenic mice.19

These proof-of-principle studies have all been pursued using recombinant protein antigens, but the development of efficient in vitro protein production protocols to express sufficient quantities of new immunogens for immunological studies can slow iterative testing of new immunogen designs. Thus, the creation of an effective nucleic acid-based platform for in vivo expression of these antigens would be of significant interest for future preclinical and clinical development. More importantly, GT approaches by design are intended to proceed by sequential immunization with multiple immunogens and, in some strategies, could involve as many as five different immunizations or cocktails of multiple antigens.20 Such multi-immunogen vaccine strategies would be expensive and complex for GMP production at scale for mass vaccination. By contrast, the ability to vaccinate with synthetic nucleic acids that could be produced at low cost via a common GMP pipeline may facilitate clinical translation of these concepts. In addition, heterologous prime-boost regimens employing nucleic acid vaccines as prime and protein immunogens as a boost have been shown to promote enhanced humoral and cellular immunity.21, 22, 23

Motivated by these factors, we sought to explore a nucleic acid vaccine platform for delivery of HIV immunogens such as the eOD-60-mer. Common platforms for nucleic acid vaccines include vaccination with plasmid DNA or in vitro-transcribed mRNA.24, 25, 26 However, to date, both DNA vaccines and first-generation non-optimized mRNA vaccines have suffered from poor induction of humoral immunity in humans. These poor responses are likely due to multiple factors including a low efficiency of delivery of DNA to the nucleus of cells, short lifetimes of mRNA in vivo, and/or innate immune stimulation by the nucleic acids.27 One alternative is to use modified RNA incorporating various unnatural bases or other modifications to enhance RNA expression lifetimes in vivo.28, 29, 30 A second promising alternative is the delivery of synthetic alphavirus replicon-based RNA, which undergoes self-replication on delivery to the cytoplasm via the transcription of non-structural proteins that copy the replicon RNA itself in addition to producing product “cargo” proteins.31, 32 Prior work has demonstrated the ability of replicon RNA to elicit potent immune responses in both small- and large-animal models when administered as viral replicon particles or in synthetic lipid or emulsion formulations.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 These data suggest replicon vaccines may be a promising platform for antigen delivery.

Here we demonstrate the immunogenicity of a lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-vectored alphavirus replicon encoding the GT eOD-GT8 immunogen fused to lumazine synthase, which self-assembles into a 60-mer protein nanoparticle. Replicon-encoded eOD-GT8 antigens were highly immunogenic in mice. Compared with recombinant protein immunization, replicon vaccination elicited ∼2-fold greater levels of antigen-specific germinal center (GC) B cells. In a knockin mouse model where B cells transgenically express the heavy chain of the human BCRs that are the target of the eOD-GT8 design,7 replicon immunization primed B cell responses and elicited somatic hypermutation comparable with recombinant protein vaccination. Altogether, these results suggest synthetic lipid-delivered replicon RNA is a promising platform for the development of GT and other serial immunization strategies in development for HIV and other infectious diseases.

Results

Replicon Design and Synthesis

We selected Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus as the source of a replicon backbone for our system. VEE’s genome is encoded by a single positive-strand RNA, encoding both the non-structural proteins (nsP1–4, which form the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex) and the structural proteins (replaced in the engineered replicons by target genes), separated by a subgenomic promotor, which drives further transcription of the structural protein-coding portion of the RNA and thus increases the copy number and expression of target proteins. We designed the replicon backbone as described previously38; the structural proteins of the replicon were replaced with either firefly luciferase or the eOD-GT8-lumazine synthase sequence7, 8 preceded by a Kozak sequence and a mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)-kappa signal peptide coding sequence; these sequences were inserted 30 bases downstream of the subgenomic transcription start site (SGP30). On the luciferase-expressing replicon, the 3′-translational unit ended with a truncated E1 protein (Figure 1A). Two different versions of eOD were tested: eOD-GT8 is comprised of eOD fused to a lumazine synthase sequence containing two point mutations: C37A to remove an unpaired cysteine and N102D to remove a glycosylation site.7, 8 eOD-GT8 d41m3 is comprised of eOD fused to the same lumazine synthase with two additional disulfides to stabilize the lumazine synthase protein.19 We established an in vitro transcription (IVT) and purification strategy that allowed for the production of highly pure full-length RNA transcripts (Figure 1B). Interestingly, we found maximal yields of replicon RNA were obtained using relatively low amounts of input plasmid DNA template for the IVT reaction (Figure 1B). Transfection of murine myoblast C2C12 cells with replicons encoding eOD-GT8 60-mer or eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer led to high levels of secreted eOD protein in the supernatants as detected by ELISA (Figure 1C). To confirm that eOD-GT8-lumazine synthase fusions correctly self-assembled to form the expected 60-mer nanoparticles when expressed from replicon RNA, we transfected HEK cells in serum-free medium, followed by dialysis of the culture supernatants to remove low-molecular-weight proteins and imaging by cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryoTEM). As shown in Figure 1D, nanoparticles of the expected diameter (∼32 nm) were observed in the supernatants of transfected cells, whereas no particles were detected in the supernatants of control untransfected cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Design of Replicons Encoding eOD-GT8 60-Mer Antigens

(A) Schematic of eOD-GT8 replicon constructs. (B) Representative PAGE analysis of in vitro-transcribed full-length replicon RNA in vitro transcribed from either 1.5 or 0.1 μg of starting template plasmid DNA. (C) 2C12 myoblast cells were electroporated with 100 ng of replicon RNA encoding eOD-GT8 or eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer antigens, and eOD-GT8 antigen in the culture supernatants was measured after 24 h by ELISA. (D) Representative transmission cryoelectron microscopy image of eOD-60-mer particles secreted by HEK cells transfected with eOD-60-mer replicons.

LNP Formulations of Replicons for In Vivo RNA Delivery

To promote effective delivery of replicons in vivo, we complexed the replicon RNA with PEGylated and cationic lipids to form LNPs, using an ethanol dialysis approach similar to approaches previously developed for DNA encapsulation.39 As outlined in Figure 2A, lipids in ethanol were combined with RNA in citrate buffer and emulsified, followed by dialysis to remove ethanol and promote lipid-RNA self-assembly. The resulting LNPs encapsulated ∼95% of added RNA (Figure 2B). The LNPs were largely unilamellar vesicles with a mean diameter of 75 nm as revealed by light scattering and cryoelectron microscopy (Figures 2C and 2D). Assuming a uniform population of LNPs with this size, this corresponds to ∼1 replicon RNA per particle.

Figure 2.

Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation of Replicons

(A) Schematic of LNP-replicon RNA formulation. (B) eOD-GT8 60-mer replicon RNA was formulated in LNPs. Total solution-accessible RNA was measured in the absence or presence of added Triton X-100 by Quan-iT assay as described in the Materials and Methods. (C) Histogram of LNP particle size assessed by dynamic light scattering. (D) Cryoelectron microscopy (cryoEM) image of replicon-loaded LNPs.

To define an effective route of administration, we compared injections of luciferase replicon LNPs in BALB/c mice given intradermally (i.d.) (in the ear), subcutaneously (s.c.) near the tail base, or intramuscularly (i.m.), and monitored luciferase expression over time in treated animals. Although LNPs produced reliable transfection in all immunized mice via all three routes, levels and duration of expression were quite distinct. Reporter gene expression was detected only at the injection site for s.c. and i.m. administrations, whereas some signal was observed in draining cervical lymph nodes in i.d. injected groups (ventral images, Figures 3A and 3B). Injection by all three routes led to reporter expression over 25–30 days with similar kinetics, but i.d. injection elicited an ∼100-fold lower peak in cargo gene expression (Figure 3C). We also modeled homologous boosting and reinjected the animals on day 40. All of the animals showed re-expression of luciferase following the second dosing, but the expression duration was shorter, decaying to baseline after ∼10 days (Figure 3C). Based on the high levels of expression and its acceptability as a site for vaccine administration in humans, we chose to focus further analysis on i.m. delivery. Comparing luciferase signals from replicon RNA versus the same reporter gene delivered by modified mRNA (modRNA), much higher levels and more prolonged gene expression duration were obtained with the replicon (Figure 3D). Two mutations have been reported to reduce cytopathic effects of VEE replicons, an A3G mutation in the 5′ UTR and a mutation in nsP2 (Q739L).40 We compared in vivo expression of luciferase reporter from wild-type VEE versus non-cytopathic (NCP) replicons including these two mutations, and found slightly prolonged expression from the NCP sequences (Figure 3D). We thus focused on the use of the NCP replicon backbone for subsequent immunogenicity studies.

Figure 3.

Optimization of Replicon-LNP Injection Route

(A–C) Albino C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) received an injection of 3 μg LNP-formulated replicon encoding luciferase intradermally (i.d.), subcutaneously (s.c.), or intramuscularly (i.m.), with a boost of the same amount of LNP-replicon on day 40. Shown are representative whole-animal IVIS bioluminescence images on day 3 from s.c. and i.m. injections (A), i.d. injections (B), and time courses of total bioluminescence signal (C). (D) BALB/c mice (n = 5/group) were administered 1 μg LNP-replicon encoding luciferase on either the wild-type (WT) or non-cytopathic mutant (NCP) replicon backbone sequence, or LNP-formulated modRNA (which incorporates N1-methyl pseudouridine) encoding luciferase, and bioluminescence signal was tracked over time by IVIS.

Humoral Responses to eOD-GT8 Antigens in Wild-Type Mice

To assess the immunogenicity of replicon immunization, we first characterized serum responses following vaccination with LNP-delivered replicons. Groups of BALB/c mice were primed on day 0 and then boosted at either 4 or 6 weeks with LNP-replicon encoding eOD-GT8 60-mer or eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer. Serum IgG titers were traced over time by ELISA. As shown in Figures 4A and 4B, a single injection of 3 μg LNP-replicon for either construct elicited high serum IgG responses. Boosting at week 4 did not further increase these (already high) IgG titers. However, following immunization with a lower dose of replicon (1 μg) where post-prime eOD-specific IgG levels were lower, mice did respond to boosting with 10-fold increases in antibody titers (Figure S1). Interestingly, the two eOD constructs primed different classes of IgG: immunization with the eOD-GT8.1 replicon elicited exclusively IgG2a subclass antibodies, whereas eOD-GT8 d41m3 replicons primed serum IgG1, IgG2a, and (weaker) IgG2b responses (Figures 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

LNP-Replicons Elicit Robust Humoral Immune Responses to eOD-GT8 60-Mer Antigens

C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 animals/group) were immunized i.m. with 3 μg LNP-formulated eOD-GT8- (A) or eOD-GT8 d41m3-encoding replicon (B) at 0 and 4 weeks, and serum IgG responses were monitored by ELISA over time. Background levels of IgG in unimmunized naive control mice are shown for comparison. (C and D) ELISA analysis of eOD-specific Ig titers by isotype in serum collected at 4 weeks post boost for eOD-GT8 60-mer (C) or eOD-GT8 d41m3-60-mer (D).

We next examined GC responses to replicon immunization, because active GCs are essential to somatic hypermutation that will promote evolution of bnAb-class antibodies from the GT immunogens. For these studies, we compared eOD-GT8 d41m3 replicon immunization with vaccination with the equivalent recombinant protein nanoparticle, which has previously been shown to be highly immunogenic.7, 8, 19 Preliminary dose response assessment varying the dose of the protein from 2 to 20 μg or replicon from 1 to 10 μg showed minimal impact on the magnitude of antigen-specific GC B cells (Figure S2). Following priming immunization, total GC B cell responses elicited by protein or replicon immunization were comparable and showed similar decay kinetics over 30 days (Figure 5A). However, when we stained GC B cells to detect eOD-specific responding cells, we found that replicon immunization induced ∼2-fold higher antigen-specific GC B cells across the entire time course (p < 0.01; Figures 5B and 5C; Figure S3A). GC B cells cycle between the light zone, where antigen is acquired from follicular dendritic cells, and the dark zone, where they proliferate and undergo somatic hypermutation. The proportion of eOD-specific GC B cells localized in the dark zone41 (CXCR4hiCD86lo) was higher for replicon compared with protein immunization (Figure 5D), suggesting a larger proportion of antigen-specific GC B cells proliferating at any given time for the LNP-replicon vaccination.

Figure 5.

LNP-Replicons Prime Strong Germinal Center Responses

(A–G) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) were immunized with 3 μg LNP-formulated eOD-GT8 d41m3 replicon or 2 μg eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer protein nanoparticles and an ISCOMs-like adjuvant. Groups of mice were sacrificed at serial time points and analyzed by flow cytometry. Frequencies of overall GC B cells (A), percentages of eOD-binding GC B cells (B), representative flow plots of eOD-binding GC B cells (C), percentages of dark zone GC B cells (D), percentages of total CD4+CXCR5+ Tfh cells (E), percentages of CXCR5+PD-1+ GC Tfh cells (F), and mean ICOS levels on Tfh cells (G) are shown. *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, by ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Follicular T helper (Tfh) cells play an important part in regulating the GC response, and thus we next analyzed Tfh cells induced by protein versus replicon immunization. Total (CD4+CXCR5+) Tfh cells trended toward higher levels following replicon immunization, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5E). GC Tfh cells (CD4+CXCR5hiPD-1hi) were induced at similar levels in the protein and replicon immunizations (Figure 5F; Figure S3B). Interestingly, the key costimulatory receptor ICOS that stimulates GC B cells during cognate interactions with Tfh42 was upregulated to higher levels on Tfh early in the response to the replicon versus protein immunizations (Figure 5G). Thus, replicon vaccines were immunogenic in wild-type mice and elicited equivalent or superior GC responses when compared with protein immunization.

Somatic Hypermutation Elicited by Replicon Vaccines in Germline-VRC01 Knockin Mice

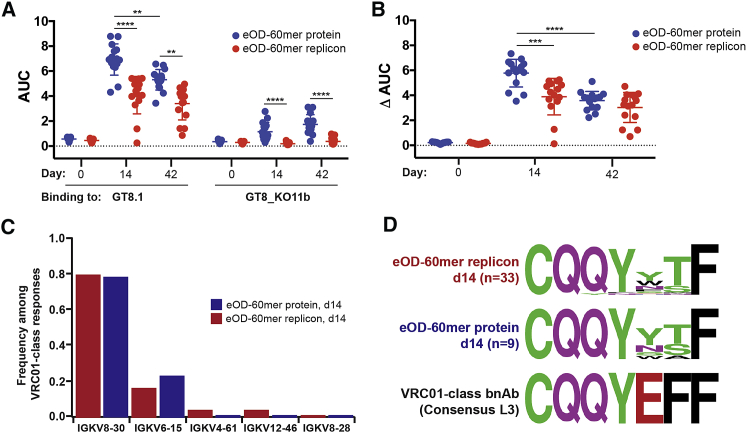

As a more rigorous test of the effectiveness of replicon immunization in priming the appropriate steps in somatic hypermutation for the GT eOD-GT8 immunogen, we finally immunized VRC01 knockin mice, whose B cells transgenically express the inferred human germline heavy chain of the VRC01 bnAb (glVRC01). This system models responses of the putative target population of naive B cells that would respond to eOD-GT8 vaccination in humans.7, 8, 15, 19 Cohorts of glVRC01 mice were immunized with recombinant eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer protein nanoparticles, or the equivalent LNP-delivered replicon. For this experiment, we increased the dose of the protein immunogen to enable comparison with our prior studies in this model.7 On days 14 and 42, sera were collected for analysis of secreted antibody responses. In parallel, on day 14 post immunization, eOD-binding B cells were sorted by flow cytometry and processed for single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of BCR sequences, to characterize somatic hypermutation occurring in the responding cells. As shown in Figure 6A, eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer protein elicited higher eOD-specific IgG responses in serum than the replicon immunization (note that this immunization was carried out using 10-fold more protein than the experiments shown in Figure 4). Interestingly, however, responses to sites outside the VRC01-class antibody footprint, detected by ELISA analysis of IgG binding to an eOD protein mutated in the CD4 binding site (GT8_KO11b), showed that the replicon elicited considerably lower off-target responses compared with the protein immunization (Figure 6A). Thus, the proportion of the ELISA response that was “on target” (ΔAUC, calculated by subtracting the ELISA area under the curve [AUC] values for eOD-GT8_KO11b binding from the AUC of IgG binding to eOD-GT8) was comparable for protein and replicon immunization by day 42 (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

LNP-Replicons Prime Responses to the CD4 Binding Site in VRC01 Germline Knockin Mice with Minimal Targeting of Other Epitopes

VRC01 gH mice (n = 5 animals/group at each time point) were immunized with either 20 μg eOD-GT8 d41m3 60-mer protein nanoparticle with Sigma Adjuvant System adjuvant or the 3-μg LNP-formulated replicon encoding the same immunogen. (A and B) Area under the curve (AUC) ELISA analysis of serum IgG binding to immobilized eOD antigen or eOD antigen-bearing mutations in the CD4 binding site (GT8_KO11b) (A) and ΔAUC, the difference in AUC binding to eOD versus the GT8_KO11b immunogen (B). (C) Ig light chain usage among VRC01-class responding B cells sorted from immunized mice at day 14. (D) Sequence motifs of LCDR3 regions of responding B cells at day 14.

Single B cell sorting and BCR sequencing revealed similar responses to protein and replicon immunogens. At day 14, 100% and 97% of protein and replicon-elicited BCRs, respectively, used the glVRC01H chain and a mouse light chain with a 5-amino acid LCDR3, appropriate for a VRC01-class antibody response; these statistics are similar to the original report of VRC01 knockin mouse immunization with eOD-60-mer protein.7 Light chain V gene usage in the responding B cells was very similar for the protein and replicon immunizations (Figure 6C). The total counts of amino acid mutations in heavy and light chains at day 14 were similar in both groups, with 2.6 ± 0.9 (n = 9) and 2.2 ± 1.1 (n = 33) mutations for protein and replicon groups, respectively. Sequence motifs in the LCDR3 regions of responding B cell light chains were nearly identical for the protein- and replicon-immunized animals at day 14 (Figure 6D). Altogether, these data suggest that replicon immunization was effective in priming VRC01-class somatic mutations in germline BCRs, comparable with immunization with the protein nanoparticle form of the immunogen.

Discussion

In order to access conserved sites on the surface of the heavily glycosylated envelope spike, broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) against HIV often have high degrees of somatic hypermutation, unusual structural features, or very restricted germline heavy and light chain usage.3, 43, 44 In addition, it has been found that when bnAbs are reverted to an inferred germline sequence, the germline BCR often does not bind to envelope.45 These characteristics have motivated vaccine development strategies based on immunization with a sequence of immunogens, beginning with a GT antigen designed to specifically engage unmutated naive B cells bearing an appropriate heavy and light chain with sufficient affinity and followed by subsequent booster immunogens that help steer the antibody response toward bnAb characteristics. The generation of a bnAb response starting from a GT immunogen has been reduced to practice in a humanized mouse model,20 demonstrating the feasibility of such an approach, but implementation of a multi-immunogen vaccine in the clinic using recombinant protein-based antigens will be challenging, because every protein requires development of a custom GMP production cell line and purification process. By contrast, an RNA platform provides a uniform, cell-free, universal manufacturing path for any immunogen,46, 47 the ability for a single GMP lot of delivery lipids to be used with RNAs encoding many different immunogens, and potent immunogenicity at low mass doses of material. Process studies at Novartis projected that a 1-L reactor can generate 5 × 105 doses of replicon RNA for human trials,48 illustrating the potential of self-replicating RNAs to impact GMP production requirements.

Here we evaluated the immunogenicity of LNP-formulated replicons encoding a promising GT gp120 immunogen, the eOD-GT8 60-mer. As a recombinant protein nanoparticle, this immunogen has previously been shown to be effective and highly immunogenic in both wild-type mice49 and transgenic mice expressing the VRC01-class human inferred germline BCRs,6, 7, 15, 16 the human VH1-2 gene,17, 18 or a broad human antibody gene repertoire.19 First, using reporter genes, we optimized the route of administration and found that our LNP-formulated replicons administered i.m. could elicit transgene expression lasting approximately 30 days. eOD-GT8 60-mer was efficiently expressed from replicons in transfected cells in culture, and LNP-replicons encoding the stabilized nanoparticle form of the immunogen, eOD-GT8 d43 m1 60-mer, elicited seroconversion in all immunized mice following a single injection. We evaluated the ability of LNP-formulated replicons to be used as a homologous boost and found that with luciferase reporter gene expression, similar peak expression levels were observed post-prime and post-boost, but the duration of expression in the boost phase was shortened to ∼10 days. Despite this contracted expression duration observed for luciferase, in immunizations with eOD-GT8 60-mer, boosting increased antibody titers ∼10-fold in response to low-dose replicon immunization (Figure S1). This is consistent with prior studies of nanoparticle-delivered replicon RNA where homologous boosting was shown to be effective in enhancing T cell and antibody responses.32 Immunization with the eOD-GT8 d41m3-60-mer-encoding replicon elicited a balanced IgG1/IgG2 humoral immune response.

A key issue for GT-based vaccines is promotion of GC responses and elicitation of appropriate somatic hypermutation toward broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb) lineages. Interestingly, LNP-replicon immunization elicited a similar Tfh cell response but increased by ∼2-fold the frequency of antigen-specific GC B cells compared with traditional protein immunization. We hypothesize this might relate to sustained provision of “fresh,” nondegraded antigen to the draining lymph nodes over time by the replicon immunization.50 Importantly, in glVRC01H transgenic mice, replicon and protein immunization elicited similar distributions of appropriate antibody light chain usage, somatic hypermutation, and LCDR3 mutations in responding B cells, suggesting that replicon immunization effectively promotes the development of VRC01-class B cell affinity maturation.

In principle, DNA- and RNA-based vaccines could share some production advantages, but the potency of DNA vaccines in large animals and humans to date has been poor, with the exception of DNA vaccines delivered by in vivo electroporation.47, 51, 52, 53 The potential of RNA to achieve more efficient transfection by requiring delivery to only the cytosol and not the nucleus, as well as the lack of concern about potential integration in the host cell, has motivated interest in RNA vaccines as an alternative. Both mRNA modified to enhance expression and stability, and alphavirus-derived self-amplifying RNAs have shown promise in animal models and early clinical trials.2, 31, 32, 33, 34, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 Alphavirus-derived replicons are attractive because even a few molecules of RNA can express the product gene at maximal levels within a few days in any cell where self-amplification occurs efficiently, and replicons (as illustrated here) can express their cargo antigen for several weeks in vivo.

In addition to the practical considerations noted above, sustained antigen expression achieved by the replicon is of interest for its potential impact on the immune response. Recent studies by us and others have demonstrated that sustained availability of antigen over time (e.g., through continuous release of vaccine from osmotic pumps) enhances Tfh and GC B cell responses, and can elicit ∼10-fold greater antibody responses compared with traditional bolus immunization.60, 61, 62 Such enhancements were also seen by administration of vaccines in an escalating dose over 2 weeks,60 a pattern similar to the escalating expression we find with replicons in vivo following administration. One theory for the effectiveness of sustained-release vaccines is that continuous arrival of fresh, fully intact antigen limits responses of B cells against proteolytic degradation products of antigen that might develop over time.50 Interestingly, we found that replicon immunization elicited GC responses that contained approximately twice as many antigen-specific B cells as immunization with the corresponding recombinant protein. We observed that peak Tfh responses occurred by day 12 following replicon immunization and decayed slowly thereafter. In interesting contrast with this finding, a recent report of immunization with HIV Env antigens designed to elicit protective T cell responses using a polymer-formulated Semliki Forest virus replicon showed that CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses were low 1 week after immunization and continued to slowly expand for ∼5–12 weeks.63 Whether these distinct kinetics reflect differences in Tfh versus Th1/CD8 priming in response to mRNA vaccination or differences in the replicon systems will be an interesting point for future study.

Formulation of RNA in synthetic lipids or polymers is an attractive strategy to avoid limitations of target cell tropism with viral vectors and anti-vector immunity that can limit the immunogenicity of the vaccine. Here we employed a simple cationic lipid formulation similar to previous reports,34 which was effective in traditional i.m. immunizations. However, enhancements in transfection efficiency and targeting of specific antigen-presenting cell subsets make further exploration of new lipid formulations of great interest for future work.

Materials and Methods

RNA Production and Purification

Replicon RNA was synthesized as previously described.38 In brief, plasmid DNA containing self-replicating RNA was propagated in Escherichia coli and purified using the Plasmid QIAprep spin mini kit (QIAGEN). The plasmid backbone sequence contains the colE1 origin, AmpR (beta-lactamase), and a ROP deletion originating from pUC19. The replicon sequence is flanked by the T7 promoter on the 5′ end and I-SceI endonuclease sites 5′ of the T7 promoter and 3′ of encoded poly(A) sequence. Templates for T7 IVT were generated via the digestion of these plasmids using I-SceI (NEB) and cleaned using the DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research). Linearized DNA templates were then transcribed using the MEGAscript T7 kit (Thermo Fisher) and purified through spin filtration using Vivaspin 500 300K molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius). RNA was post-transcriptionally capped using the ScriptCap m7G and 2′-O-methyltransferase capping system (Cellscript).

Templates for IVT of modRNA were generated by PCR amplification of the replicon open reading frame (ORF) from sequence-verified plasmid. The modRNA was produced by IVT (Invitrogen MegaScript T7 AM1333) with N1-methyl pseudouridine-5′-triphosphate (TriLink Biotechnologies) completely replacing uridine triphosphate (UTP).64 RNA was purified by LiCl precipitation and capped using a vaccinia capping enzyme and 2′-O-methyltransferase (Cellscript). Capped RNA was buffer exchanged and concentrated in 10K MWCO PES centrifugal filters (Sartorius) before loading onto HPLC for reverse-phase chromatography purification as previously described.65 RNA purity was verified by spectrophotometry using NanoDrop One equipment (Thermo Fisher). Typical absorbance ratios of RNAs used in this study were A260/280 ∼2.01–2.03 and A260/230 ∼2.1–2.18.

LNP Formulation of Replicons and LNP Characterization

1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cholesterol was obtained from Millipore-Sigma. LNPs were made by a modified ethanol dilution process39 using a molar ratio of lipid components at 40:10:48:2 DOTAP/DSPC/cholesterol/DSPE-PEG mole ratios, and an 8:1 N/P molar ratio of DOTAP nitrogen to RNA phosphate groups. In brief, equal volumes of lipid mixture (in ethanol) and replicon RNA (in 100 mM citrate buffer [pH 6.0]) were mixed by vigorous pipetting, followed by addition of equal volume of buffer. Particles are equilibrated for 1 h at room temperature in a platform rocker and subsequently dialyzed in PBS for 1 h at room temperature using a 20K MWCO Slide-A-Lyzer mini dialysis device (Thermo Fisher). Particle characterization included size measurements by light scattering using Zetasizer Nano ZSP equipment (Malvern) and cryoelectron microscopy using a JEOL 2100F transmission electron microscope in the Swanson Biotechnology Center Nanotechnology Core at the Koch Institute, MIT. Quantification of RNA encapsulation was done using the Quan-iT RiboGreen RNA assay kit (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Particles were resuspended in Tris-EDTA with or without Triton X-100 (0.5% v/v). Percent of RNA encapsulation was calculated following the formula: % encapsulation = 100 − (RNA concno Triton × 100/RNA conc+Triton).

In Vitro Transfection Analysis

C2C12 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma) up to 50% confluency. Subsequently, cells were electroporated (one pulse, 1,400 mV, 20 ms) using the Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Typically, 50,000 cells were transfected with 100 ng replicon RNA. Cells were then seeded in complete growth medium in a 24-well plate. Culture supernatants were collected after 24 h and used in ELISA assays to detect expression of eOD-GT8 60-mer. In brief, Nunc MaxiSorp 96-well plates were coated overnight with murine VRC01 chimera antibody,66 then blocked for 2 h with PBS containing 10% BSA. Supernatants from transfected cells were added at different dilutions and incubated for 2 h. GT8 protein was detected using human VRC01 antibody, followed by 1:5,000 goat anti-human IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibody conjugate (Bio-Rad). Concentration of eOD-GT8 60-mer in cell supernatants was calculated based on a standard curve done using purified eOD-GT8 60-mer protein.

To assess assembly of the eOD-GT8-lumazine synthase fusions into nanoparticles following expression from replicons, 5 × 106 HEK cells were electroplated using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10 μg replicon RNA and were seeded in Expi293 serum-free expression media. Control cells were left untransfected as controls. Forty-eight hours later, cell supernatants from transfected and control cells were collected and dialyzed against deionized H2O using a 1,000-kDa MWCO membrane to remove low-molecular-weight contaminants, followed by cryoTEM imaging on a JEOL 2100F TEM.

Animals

Female C57BL/6, albino C57BL/6 [B6(Cg)-Tyrc2-J/J], or BALB/c mice 6–8 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories and handled under state, local, and federal guidelines following an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol. Male and female VRC01 gH mice6, 7 6–8 weeks of age were housed and immunized following an IACUC-approved protocol.

Immunizations in Wild-Type Mice

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.m. with indicated doses of LNP-formulated replicons or eOD 60-mer protein nanoparticles mixed with 5 μg of an immune-stimulating complexes (ISCOMs)-like saponin adjuvant. The ISCOMs adjuvant was prepared as previously described.66 IgG responses were characterized by ELISA analysis of serum. In brief, NUNC MaxiSorp plates were coated overnight with 1 μg/mL purified recombinant eOD 60-mer in PBS. Subsequently, plates were blocked for 2 h with PBS plus 10% BSA. Mouse sera were initially diluted 50× in blocking buffer, followed by 3× serial dilutions. Diluted sera were transferred to blocked plates and incubated for 2 h. Anti-eOD IgG was detected using goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP-conjugated antibody (Bio-Rad) at 1:5,000. IgG isotypes were detected using anti-mouse IgG1 (clone RMG1-1), IgG2a (clone RMG2a-62), or IgG2b (clone RMG2b-1) biotin-conjugated antibodies (BioLegend) diluted at 1:500, followed by 1:5,000 streptavidin-HRP conjugate. All titers reported are inverse dilutions where reference wavelength (A450nm − A540nm) equals 0.08.

Luciferase Imaging

To detect expression of luciferase over time, groups of albino C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice were injected i.m. with indicated doses of LNP-formulated replicons coding for Firefly luciferase. D-luciferin suspended in PBS was injected intraperitoneally (150 mg/kg body weight) in anesthetized animals 10 min prior to bioluminescence image acquisition on a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (Caliper Life Science). Living Image software version 4.5 (Caliper Life Science) was used to acquire and quantitate bioluminescence image datasets.

GC and T Follicular Helper Cell Analysis

Groups of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized with eOD-expressing replicon as stated above or with 2 μg eOD (GT8 d41m3)-60-mer protein administered s.c. at the tail base along with 5 μg ISCOMATRIX-like saponin nanoparticle adjuvant. Saponin nanoparticle adjuvant was synthesized as previously described.67 Mice were sacrificed at days 12, 21, and 33, and their draining lymph nodes were harvested and processed into a single-cell suspension for flow cytometry analysis. Samples were stained with Live/Dead Aqua (Life Technologies) for 15 min at 25°C, then treated with anti-CD16/32 Fc block (BioLegend). Cells were then stained for 30 min at 4°C with the following antibodies acquired from BioLegend or BD Biosciences: B220 (RA3-6B2), CD38 (90), CD4 (RM4-5), CD86 (GL-1), CXCR5 (L138D7), CXCR4 (2B11), GL-7 (GL7), ICOS (7E.17G9), and PD-1 (J43). Antigen-specific GC responses were detected with Alexa Fluor 647-tagged eOD-60-mer (A20186; Thermo Fisher). Antigen-specific GC B cells were gated as (live, B220+, CD4−, CD38lo, GL7+, eOD+), and Tfh cells were gated as (live, CD4+, B220−, CXCR5hi, PD1hi).

VCR01 gH Knockin Mouse Immunizations and BCR Sequencing

Groups of 6- to 8-week-old VRC01 gH mice were immunized i.m. with eOD-expressing replicon or intraperitoneally with 20 μg of eOD (GT8 d41m3)-60-mer protein and Sigma Adjuvant System. IgG responses were characterized by ELISA at days 14 and 42. Several mice per group were sacrificed at days 14 and 35; cell preparations were made from the spleens and sacral, sciatic, lumbar, popliteal, iliac, mesenteric, and inguinal lymph nodes; B cells were purified, and single B cells were sorted as previously described,6 except that the cells were sorted as eOD-GT8 double positive (two colors) and eOD-GT8-KO11 negative (one color); BCR sequences were obtained by RT-PCR, barcoding, and next-generation sequencing as previously described.6

ELISA for Detection of Serum Antibody

ELISAs were performed to investigate the polyclonal response in sera of eOD-GT8-primed VRC01 gH mice and to verify the epitope specificity of induced antibodies to the eOD-GT8 proteins. eOD-GT8 antigens were diluted to 2 μg/mL in coating buffer (PBS [pH 7.4]; Catalog #10010-023; Thermo Scientific), and 25 μL was added to each well of ELISA plates (Corning 96-Well Half-Area Plates, Catalog #3690) and allowed to adhere overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.2% (v/v) Tween (PBST) (Tween 20; Catalog #P1379-1L; Sigma) using an automated microplate washer (405 TS Washer; BioTek Instrument). To block non-specific binding, PBST containing 5% (w/v) skim milk (BD Difco Skim Milk Catalog #232100) and 1% (v/v) FBS (Catalog #16000044; Thermo Fisher) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Following a washing step as outlined above, plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with serial dilutions of the sera in binding buffer (1% [v/v] FBS in PBST, 25 μL/well). As controls, the last row of each plate was incubated with binding buffer alone (no primary antibody). Following a washing step, plates were incubated for 1 h at RT with the Peroxidase-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (1:5,000; Catalog #115-035 166; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Plates were then washed five times with PBST and incubated with 25 μL/well of TMB Chromogen Solution (Catalog #002023; Thermo Fisher) as substrate. The reaction was terminated by addition of 25 μL of 0.5 M H2SO4, and absorbance was read at 450 and 570 nm on a VERSA max plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA). Background subtraction was performed by subtracting the 570 nm value from the corresponding 450 nm value. The data were subsequently analyzed in Prism (Prism v.7; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) that computes the AUC by the trapezoidal method, which is based on connection of a straight line between every set of adjacent points defining the curve and on a sum of the areas beneath these areas.

Author Contributions

E.P. and B.D. designed replicon backbones and synthesized RNAs. M.M., Y.Z., and M.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. N.L. performed experiments. A.L. developed and performed ELISA protocols. W.R.S. provided the immunogens. P.S. performed experiments with VRC01 gH mice. E.L., S.M., and D.S. carried out B cell sorting and sequencing. D.N. provided the VRC01 gH mice. W.R.S. provided immunogens, analyzed data, supervised research, and wrote the manuscript. D.J.I. and R.W. supervised the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

W.R.S. is a co-founder and stockholder in Compuvax, Inc., which has programs in non-HIV vaccine design that might benefit indirectly from this research.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support, specifically the Flow Cytometry, Animal Imaging & Preclinical testing, and Nanotechnology Materials Core Facilities. This work was supported in part by the NIAID under awards UM1AI100663 (to D.J.I. and W.R.S.), AI104715 (to D.J.I.), EB025854 (to D.J.I. and R.W.), and AI048240 (to D.J.I.); the Koch Institute Support (core) grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute; the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard; the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) Neutralizing Antibody Consortium (NAC) and Center (to W.R.S.); and the Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery funding for the IAVI NAC Center (to W.R.S.). IAVI’s work is made possible by generous support from many donors, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Finance of Japan in partnership with The World Bank, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the UK Department for International Development (DFID), and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The full list of IAVI donors is available at https://www.iavi.org/. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. D.J.I. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.08.007.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Fauci A.S. An HIV Vaccine Is Essential for Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic. JAMA. 2017;318:1535–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberer M., Gnad-Vogt U., Hong H.S., Mehr K.T., Backert L., Finak G., Gottardo R., Bica M.A., Garofano A., Koch S.D. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1511–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31665-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes B.F., Burton D.R. Developing an HIV vaccine. Science. 2017;355:1129–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes B.F., Mascola J.R. The quest for an antibody-based HIV vaccine. Immunol. Rev. 2017;275:5–10. doi: 10.1111/imr.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Taeye S.W., Moore J.P., Sanders R.W. HIV-1 Envelope Trimer Design and Immunization Strategies To Induce Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briney B., Sok D., Jardine J.G., Kulp D.W., Skog P., Menis S., Jacak R., Kalyuzhniy O., de Val N., Sesterhenn F. Tailored immunogens direct affinity maturation toward HIV neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2016;166:1459–1470.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jardine J.G., Ota T., Sok D., Pauthner M., Kulp D.W., Kalyuzhniy O., Skog P.D., Thinnes T.C., Bhullar D., Briney B. HIV-1 VACCINES. Priming a broadly neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1 using a germline-targeting immunogen. Science. 2015;349:156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jardine J., Julien J.P., Menis S., Ota T., Kalyuzhniy O., McGuire A., Sok D., Huang P.S., MacPherson S., Jones M. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science. 2013;340:711–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1234150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire A.T., Hoot S., Dreyer A.M., Lippy A., Stuart A., Cohen K.W., Jardine J., Menis S., Scheid J.F., West A.P. Engineering HIV envelope protein to activate germline B cell receptors of broadly neutralizing anti-CD4 binding site antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:655–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steichen J.M., Kulp D.W., Tokatlian T., Escolano A., Dosenovic P., Stanfield R.L., McCoy L.E., Ozorowski G., Hu X., Kalyuzhniy O. HIV Vaccine Design to Target Germline Precursors of Glycan-Dependent Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Immunity. 2016;45:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamatatos L., Pancera M., McGuire A.T. Germline-targeting immunogens. Immunol. Rev. 2017;275:203–216. doi: 10.1111/imr.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams W.B., Zhang J., Jiang C., Nicely N.I., Fera D., Luo K., Moody M.A., Liao H.X., Alam S.M., Kepler T.B. Initiation of HIV neutralizing B cell lineages with sequential envelope immunizations. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1732. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01336-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou T., Georgiev I., Wu X., Yang Z.Y., Dai K., Finzi A., Kwon Y.D., Scheid J.F., Shi W., Xu L. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329:811–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheid J.F., Mouquet H., Ueberheide B., Diskin R., Klein F., Oliveira T.Y., Pietzsch J., Fenyo D., Abadir A., Velinzon K. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science. 2011;333:1633–1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott R.K., Lee J.H., Menis S., Skog P., Rossi M., Ota T., Kulp D.W., Bhullar D., Kalyuzhniy O., Havenar-Daughton C. Precursor Frequency and Affinity Determine B Cell Competitive Fitness in Germinal Centers, Tested with Germline-Targeting HIV Vaccine Immunogens. Immunity. 2018;48:133–146.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosenovic P., von Boehmer L., Escolano A., Jardine J., Freund N.T., Gitlin A.D., McGuire A.T., Kulp D.W., Oliveira T., Scharf L. Immunization for HIV-1 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies in Human Ig Knockin Mice. Cell. 2015;161:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian M., Cheng C., Chen X., Duan H., Cheng H.L., Dao M., Sheng Z., Kimble M., Wang L., Lin S. Induction of HIV Neutralizing Antibody Lineages in Mice with Diverse Precursor Repertoires. Cell. 2016;166:1471–1484.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan H., Chen X., Boyington J.C., Cheng C., Zhang Y., Jafari A.J., Stephens T., Tsybovsky Y., Kalyuzhniy O., Zhao P. Glycan Masking Focuses Immune Responses to the HIV-1 CD4-Binding Site and Enhances Elicitation of VRC01-Class Precursor Antibodies. Immunity. 2018;49:301–311.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sok D., Briney B., Jardine J.G., Kulp D.W., Menis S., Pauthner M., Wood A., Lee E.C., Le K.M., Jones M. Priming HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in human Ig loci transgenic mice. Science. 2016;353:1557–1560. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escolano A., Steichen J.M., Dosenovic P., Kulp D.W., Golijanin J., Sok D., Freund N.T., Gitlin A.D., Oliveira T., Araki T. Sequential Immunization Elicits Broadly Neutralizing Anti-HIV-1 Antibodies in Ig Knockin Mice. Cell. 2016;166:1445–1458.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng S., Qiu J., Yang A., Yang B., Jeang J., Wang J.W., Chang Y.N., Brayton C., Roden R.B.S., Hung C.F., Wu T.C. Optimization of heterologous DNA-prime, protein boost regimens and site of vaccination to enhance therapeutic immunity against human papillomavirus-associated disease. Cell Biosci. 2016;6:16. doi: 10.1186/s13578-016-0080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal R., Kalyanaraman V.S., Nair B.C., Whitney S., Keen T., Hocker L., Hudacik L., Rose N., Mboudjeka I., Shen S. Immunization of rhesus macaques with a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine elicits protective antibody response against simian human immunodeficiency virus of R5 phenotype. Virology. 2006;348:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kardani K., Bolhassani A., Shahbazi S. Prime-boost vaccine strategy against viral infections: Mechanisms and benefits. Vaccine. 2016;34:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L., Petrovsky N. Molecular mechanisms for enhanced DNA vaccine immunogenicity. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2016;15:313–329. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1124762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Zhang L., Xu Z., Miao L., Huang L. mRNA Vaccine with Antigen-Specific Checkpoint Blockade Induces an Enhanced Immune Response against Established Melanoma. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:420–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalczyk A., Doener F., Zanzinger K., Noth J., Baumhof P., Fotin-Mleczek M., Heidenreich R. Self-adjuvanted mRNA vaccines induce local innate immune responses that lead to a potent and boostable adaptive immunity. Vaccine. 2016;34:3882–3893. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Beuckelaer A., Pollard C., Van Lint S., Roose K., Van Hoecke L., Naessens T., Udhayakumar V.K., Smet M., Sanders N., Lienenklaus S. Type I Interferons Interfere with the Capacity of mRNA Lipoplex Vaccines to Elicit Cytolytic T Cell Responses. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:2012–2020. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Naradikian M.S., Parkhouse K., Cain D.W., Jones L., Moody M.A., Verkerke H.P., Myles A., Willis E. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1571–1588. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Welsh F.A., Ludwig J., Kato H., Akira S., Weissman D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1833–1840. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell. 2017;169:176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljungberg K., Liljeström P. Self-replicating alphavirus RNA vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2015;14:177–194. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.965690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogers W.M., Oostermeijer H., Mooij P., Koopman G., Verschoor E.J., Davis D., Ulmer J.B., Brito L.A., Cu Y., Banerjee K. Potent immune responses in rhesus macaques induced by nonviral delivery of a self-amplifying RNA vaccine expressing HIV type 1 envelope with a cationic nanoemulsion. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;211:947–955. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brito L.A., Chan M., Shaw C.A., Hekele A., Carsillo T., Schaefer M., Archer J., Seubert A., Otten G.R., Beard C.W. A cationic nanoemulsion for the delivery of next-generation RNA vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:2118–2129. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geall A.J., Verma A., Otten G.R., Shaw C.A., Hekele A., Banerjee K., Cu Y., Beard C.W., Brito L.A., Krucker T. Nonviral delivery of self-amplifying RNA vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14604–14609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209367109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knudsen M.L., Ljungberg K., Kakoulidou M., Kostic L., Hallengärd D., García-Arriaza J., Merits A., Esteban M., Liljeström P. Kinetic and phenotypic analysis of CD8+ T cell responses after priming with alphavirus replicons and homologous or heterologous booster immunizations. J. Virol. 2014;88:12438–12451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02223-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel A.B., Lambert L., Kinnear E., Busse D., Erbar S., Reuter K.C., Wicke L., Perkovic M., Beissert T., Haas H. Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccines Give Equivalent Protection against Influenza to mRNA Vaccines but at Much Lower Doses. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granot T., Yamanashi Y., Meruelo D. Sindbis viral vectors transiently deliver tumor-associated antigens to lymph nodes and elicit diversified antitumor CD8+ T-cell immunity. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:112–122. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wroblewska L., Kitada T., Endo K., Siciliano V., Stillo B., Saito H., Weiss R. Mammalian synthetic circuits with RNA binding proteins for RNA-only delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:839–841. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffs L.B., Palmer L.R., Ambegia E.G., Giesbrecht C., Ewanick S., MacLachlan I. A scalable, extrusion-free method for efficient liposomal encapsulation of plasmid DNA. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s11095-004-1873-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrakova O., Volkova E., Gorchakov R., Paessler S., Kinney R.M., Frolov I. Noncytopathic replication of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and eastern equine encephalitis virus replicons in Mammalian cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:7597–7608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7597-7608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gitlin A.D., Nussenzweig M.C. Immunology: Fifty years of B lymphocytes. Nature. 2015;517:139–141. doi: 10.1038/517139a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simpson T.R., Quezada S.A., Allison J.P. Regulation of CD4 T cell activation and effector function by inducible costimulator (ICOS) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010;22:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burton D.R., Mascola J.R. Antibody responses to envelope glycoproteins in HIV-1 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:571–576. doi: 10.1038/ni.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sok D., Laserson U., Laserson J., Liu Y., Vigneault F., Julien J.P., Briney B., Ramos A., Saye K.F., Le K. The effects of somatic hypermutation on neutralization and binding in the PGT121 family of broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003754. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoot S., McGuire A.T., Cohen K.W., Strong R.K., Hangartner L., Klein F., Diskin R., Scheid J.F., Sather D.N., Burton D.R., Stamatatos L. Recombinant HIV envelope proteins fail to engage germline versions of anti-CD4bs bNAbs. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pascolo S. Messenger RNA-based vaccines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:1285–1294. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ulmer J.B., Mason P.W., Geall A., Mandl C.W. RNA-based vaccines. Vaccine. 2012;30:4414–4418. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulmer J.B., Mansoura M.K., Geall A.J. Vaccines ‘on demand’: science fiction or a future reality. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015;10:101–106. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.996128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokatlian T., Read B.J., Jones C.A., Kulp D.W., Menis S., Chang J.Y.H., Steichen J.M., Kumari S., Allen J.D., Dane E.L. Innate immune recognition of glycans targets HIV nanoparticle immunogens to germinal centers. Science. 2019;363:649–654. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cirelli K.M., Crotty S. Germinal center enhancement by extended antigen availability. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017;47:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalams S.A., Parker S., Jin X., Elizaga M., Metch B., Wang M., Hural J., Lubeck M., Eldridge J., Cardinali M., NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network Safety and immunogenicity of an HIV-1 gag DNA vaccine with or without IL-12 and/or IL-15 plasmid cytokine adjuvant in healthy, HIV-1 uninfected adults. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalams S.A., Parker S.D., Elizaga M., Metch B., Edupuganti S., Hural J., De Rosa S., Carter D.K., Rybczyk K., Frank I., NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network Safety and comparative immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA vaccine in combination with plasmid interleukin 12 and impact of intramuscular electroporation for delivery. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:818–829. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bagarazzi M.L., Yan J., Morrow M.P., Shen X., Parker R.L., Lee J.C., Giffear M., Pankhong P., Khan A.S., Broderick K.E. Immunotherapy against HPV16/18 generates potent TH1 and cytotoxic cellular immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:155ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Pelc R.S., Muramatsu H., Andersen H., DeMaso C.R., Dowd K.A., Sutherland L.L., Scearce R.M., Parks R. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017;543:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liang F., Lindgren G., Lin A., Thompson E.A., Ols S., Röhss J., John S., Hassett K., Yuzhakov O., Bahl K. Efficient Targeting and Activation of Antigen-Presenting Cells In Vivo after Modified mRNA Vaccine Administration in Rhesus Macaques. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2635–2647. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bahl K., Senn J.J., Yuzhakov O., Bulychev A., Brito L.A., Hassett K.J., Laska M.E., Smith M., Almarsson Ö., Thompson J. Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1316–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim D.Y., Atasheva S., McAuley A.J., Plante J.A., Frolova E.I., Beasley D.W., Frolov I. Enhancement of protein expression by alphavirus replicons by designing self-replicating subgenomic RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10708–10713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408677111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L., Wang Y., Xiao Y., Wang Y., Dong J., Gao K., Gao Y., Wang X., Zhang W., Xu Y. Enhancement of antitumor immunity using a DNA-based replicon vaccine derived from Semliki Forest virus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pyankov O.V., Bodnev S.A., Pyankova O.G., Solodkyi V.V., Pyankov S.A., Setoh Y.X., Volchkova V.A., Suhrbier A., Volchkov V.V., Agafonov A.A., Khromykh A.A. A Kunjin Replicon Virus-like Particle Vaccine Provides Protection Against Ebola Virus Infection in Nonhuman Primates. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212(Suppl 2):S368–S371. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tam H.H., Melo M.B., Kang M., Pelet J.M., Ruda V.M., Foley M.H., Hu J.K., Kumari S., Crampton J., Baldeon A.D. Sustained antigen availability during germinal center initiation enhances antibody responses to vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E6639–E6648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606050113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pauthner M., Havenar-Daughton C., Sok D., Nkolola J.P., Bastidas R., Boopathy A.V., Carnathan D.G., Chandrashekar A., Cirelli K.M., Cottrell C.A. Elicitation of Robust Tier 2 Neutralizing Antibody Responses in Nonhuman Primates by HIV Envelope Trimer Immunization Using Optimized Approaches. Immunity. 2017;46:1073–1088.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu J.K., Crampton J.C., Cupo A., Ketas T., van Gils M.J., Sliepen K., de Taeye S.W., Sok D., Ozorowski G., Deresa I. Murine antibody responses to cleaved soluble HIV-1 envelope trimers are highly restricted in specificity. J. Virol. 2015;89:10383–10398. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01653-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moyo N., Vogel A.B., Buus S., Erbar S., Wee E.G., Sahin U., Hanke T. Efficient Induction of T Cells against Conserved HIV-1 Regions by Mosaic Vaccines Delivered as Self-Amplifying mRNA. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;12:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andries O., Mc Cafferty S., De Smedt S.C., Weiss R., Sanders N.N., Kitada T. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J. Control. Release. 2015;217:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Ludwig J., Weissman D. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tokatlian T., Kulp D.W., Mutafyan A.A., Jones C.A., Menis S., Georgeson E., Kubitz M., Zhang M.H., Melo M.B., Silva M. Enhancing Humoral Responses Against HIV Envelope Trimers via Nanoparticle Delivery with Stabilized Synthetic Liposomes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16527. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34853-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morein B., Sundquist B., Höglund S., Dalsgaard K., Osterhaus A. Iscom, a novel structure for antigenic presentation of membrane proteins from enveloped viruses. Nature. 1984;308:457–460. doi: 10.1038/308457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.