Abstract

Leishmania is the aethiological agent responsible for the visceral leishmaniasis, a serious parasite-borne disease widely spread all over the World. The emergence of resistant strains makes classical treatments less effective; therefore, new and better drugs are necessary. Naphthoquinones are interesting compounds for which many pharmacological properties have been described, including leishmanicidal activity. This work shows the antileishmanial effect of two series of terpenyl-1,4-naphthoquinones (NQ) and 1,4-anthraquinones (AQ) obtained from natural terpenoids, such as myrcene and myrceocommunic acid. They were evaluated both in vitro and ex vivo against the transgenic iRFP-Leishmania infantum strain and also tested on liver HepG2 cells to determine their selectivity indexes. The results indicated that NQ derivatives showed better antileishmanial activity than AQ analogues, and among them, compounds with a diacetylated hydroquinone moiety provided better results than their corresponding quinones. Regarding the terpenic precursor, compounds obtained from the monoterpenoid myrcene displayed good antiparasitic efficiency and low cytotoxicity for mammalian cells, whereas those derived from the diterpenoid showed better antileishmanial activity without selectivity. In order to explore their mechanism of action, all the compounds have been tested as potential inhibitors of Leishmania type IB DNA topoisomerases, but only some compounds that displayed the quinone ring were able to inhibit the recombinant enzyme in vitro. This fact together with the docking studies performed on LTopIB suggested the existence of another mechanism of action, alternative or complementary to LTopIB inhibition. In silico druglikeness and ADME evaluation of the best leishmanicidal compounds has shown good predictable druggability.

Keywords: Leishmania infantum, Terpenylquinones, Naphthoquinones, Anthraquinones, Acridinequinone, DNA-Topoisomerase IB

Abbreviations: VL, Visceral Leishmaniasis; LTopIB, Leishmania Type IB DNA Topoisomerase; AMB, Amphotericin B deoxycholate; MTF, Miltefosine; CPT, Camptothecin; iRFP, Infrared Fluorescent Protein; FBS, Foetal Bovine Serum; SI, Selectivity Index; NQ, Naphthoquinone; AQ, Anthraquinone; BAcQ, Benzoacridinequinone

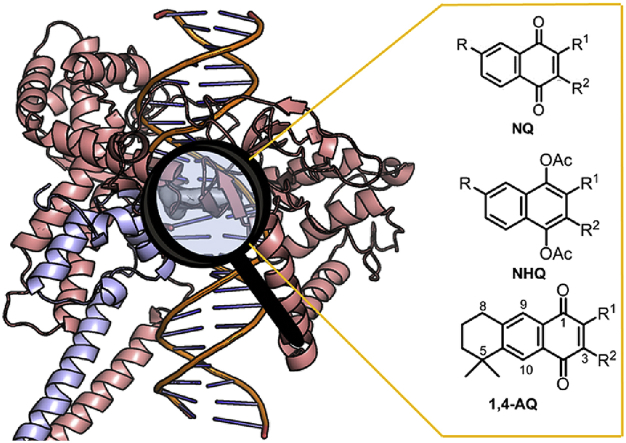

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

15 out of 37 compounds arrested L. infantum amastigotes at EC50 < 10 μM.

-

•

Naphthoquinones showed better antileishmanial activity than anthraquinones.

-

•

Those from myrcene showed good antiparasitic efficiency and low cytotoxicity.

-

•

Docking predicted good LTopIB interaction, and a few members inhibited the enzyme.

-

•

In silico drug-likeness evaluation predicts good druggability and low in vivo toxicity.

1. Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a serious parasite-borne disease widely spread all over the World and responsible of ca. 400,000 new cases per year, mostly in Eastern Africa and Indian subcontinent (Dorlo et al., 2017). Leishmania donovani and L. infantum are the pathogens responsible of VL in the Old World, whereas L. (Viannia) infantum chagasi is the pathogen responsible in the New World. The first-line treatment against VL is based on compounds of pentavalent antimony (SbV), as meglumine antimonate and sodium stibogluconate, whose activity is decreasing due to its massive use and other environmental factors in the Indian subcontinent (Burza et al., 2018). Therefore, the emergence of resistant strains of L. donovani in the northeastern Indian state of Bihar, recommended the substitution of SbV-based drugs by the administration of a single dose of the polyene antifungal amphotericin B (AMB) formulated in liposomes (Sundar et al., 2010). Nowadays, despite the efforts made by all the stakeholders involved, there is not an antileishmanial drug free of side effects, easily administrable and affordable for the impoverished economies of the endemic countries (Monge-Maillo and López-Vélez, 2013; Shakya et al., 2011; Aït-Oudhia et al., 2011). Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), an International organization founded by “Médecins sans Frontières” and the public sector of some endemic countries, has promoted the application of several treatments based on the specific target profiles of the disease in Africa and India, using combinations of the current drugs in clinical use. Far to be a definitive solution, novel and more friendly medicines are urgently needed to face this disease (Barrett and Croft, 2012).

The identification of primary and selective drug targets is in the pipeline of early drug discovery against VL (Reguera et al., 2014; Balaña-Fouce et al., 2019). Naphthoquinones (NQs) are natural compounds found in different families of plants, including Bignoniaceae and Verbenaceae. These substances contain a double conjugated α,β-dienedione (quinone) system in a base skeleton of naphthalene. Lapachol, α-lapachone and β-lapachone are well known NQs used in medicinal chemistry studies (De Moura et al., 2001; Pinto and de Castro, 2009). Such compounds, besides being obtained from natural sources, can be easily synthesized and have inspired the synthesis of many other substances with potential pharmacological activities, including some drug candidates against neglected diseases (Ferreira et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2013b). The oxidant stress activity of quinone-bearing compounds is well-known and can partly explain the leishmanicidal of these compounds (Araújo et al., 2017; Teixeira et al., 2001; Ali et al., 2011). However, it has been reported that certain NQs can primary interact with eukaryotic type IB DNA topoisomerases (TopIB), which may lead to apoptosis-like death in Leishmania (Araújo et al., 2019).

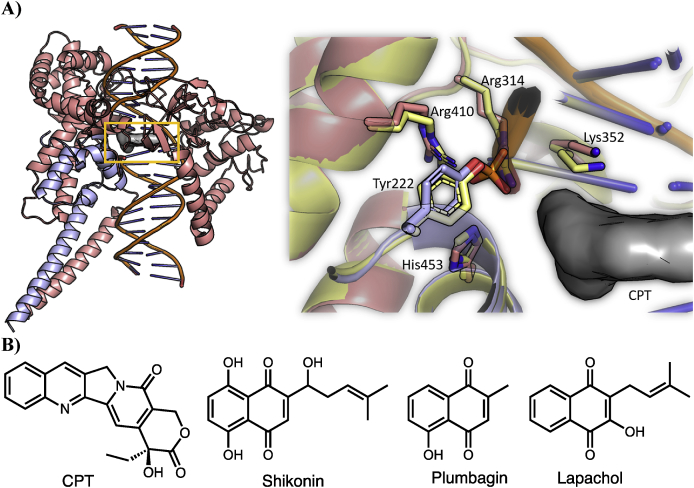

Two reasons support the robustness of TopIB as an attractive druggable target in Leishmania (Bodley et al., 2003): i) Leishmania TopIB (LTopIB) is differentially expressed during the infection process within the host, and more striking ii) LTopIB differs in structure from its human counterpart (Balaña-Fouce et al., 2014; Reguera et al., 2006; Villa et al., 2003). Fig. 1A shows the active site of LTopIB superimposed to human TopIB (hTopIB) in the presence of camptothecin (CPT, Fig. 1B) a specific TopIB poison (Ioanoviciu et al., 2005; Pommier et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

A) Structure of LTopIB interaction complexes. LTopIB, unlike human's, is atypically composed of two different subunits, which have to be assembled in the pathogen to reconstitute the enzyme activity. One of the subunits contains the four amino acids of the active site and the other contains the catalytic amino acid (Tyr222), which acts by breaking one DNA strand into a specific nucleotide sequence (Villa et al., 2003). Left: Structure of the Leishmania TopIB-DNA-CPT ternary complex. The model was built based on PDB: 1T8I structure (See methods for further details). The two subunits are displayed with different colors (salmon and blue) and CPT, which is intercalated between base pairs of DNA, is shown as a grey surface. The active site of LTopIB is located inside the yellow rectangle. Right: Structure of the active site of LTop1B. The important catalytic residues are displayed atomistically, and CPT is displayed as a grey surface. The color scheme is the same used for the left panel. To show the structural similarity between the active site of hTopIB and LTopIB, the structure of the human isoform is shown in yellow (PDB 1TL8). Tyr222 is phosphorylated in our model, the same as in the hTopIB structure. B) Structures of several inhibitors of topoisomerase IB. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Several reports show that NQs, such as the anticancer drugs of natural origin shikonin and plumbagin (Fig. 1B) are good inhibitors of TopIB preventing the formation of the enzyme-DNA covalent complex and inducing apoptosis (Chen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Beretta et al., 2017). Similarly, β-lapachone and lapachol inhibited TopIB but did not stabilize the cleavable complex, indicating a mechanism of action associated to catalytic inhibition (Li et al., 1993; Xu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016).

Thus, the present study aims to evaluate the leishmanicidal activity of terpenyl-1,4-NQ, 1,4-anthraquinone (1,4-AQ) and benzoacridinequinone (BAcQ) derivatives and several related naphthalene and anthracene analogues previously synthesized at our laboratory (Castro et al., 2013a; Castro et al., 2015; Miguel del Corral et al., 1998; Miguel del Corral et al., 2001; Miguel del Corral et al., 2007; Chamorro, 2002; Rodríguez, 2006). In this study, we assess the antileishmanial effects of these compounds against both stages – free-living promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes – of L. infantum, one of the aethiological agent responsible for VL in humans and dogs in the Old World. For this purpose, an intracellular screening on macrophages isolated from infected BALB/c mice with an infrared-emitting L. infantum strain was used (Calvo-Álvarez et al., 2015b). This method has the advantage of using host-infected cells under natural conditions, where the immune cells of spleen are still playing their role (Calvo-Álvarez et al., 2015a). Furthermore, we have explored the potential role played by LTopIB as putative target of these compounds.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemistry

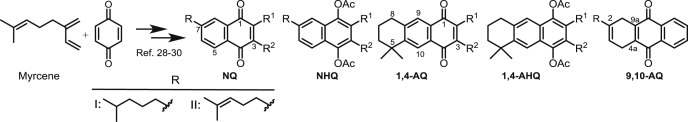

The structures of quinone and hydroquinone derivatives evaluated in this work are summarized in Table 1, Table 2. The syntheses of these compounds were made according to previous reports. Compounds showed in Table 1 are derived from myrcene. Derivatives 1–20 and 25 were obtained after an initial catalysed Diels-Alder condensation between myrcene and p-benzoquinones (Castro et al., 2013a; Castro et al., 2015; Miguel del Corral et al., 1998), generating terpenyl-1,4-naphthoquinones (NQ, 1–6), terpenyl-1,4-naphthohydroquinones (NHQ, 7–11), 1,4-anthraquinones (1,4-AQ, 12–17), 1,4-anthrahydroquinones (1,4-AHQ, 18–20) and compound 25. Similar condensation between 1,4-NQ and myrcene led to 9,10-anthraquinone derivatives (9,10-AQ, 21–24). Compounds shown in Table 2 were similarly obtained from the Diels-Alder condensation between the diterpenoid myrceocommunic acid and p-benzoquinone or 1,4-NQ generating diterpenylnaphthohydroquinone derivatives (DNHQ, 26–37) (Miguel del Corral et al., 2001; Miguel del Corral et al., 2007; Chamorro, 2002; Rodríguez, 2006).

Table 1.

Structures and bioactivity data for terpenyl-quinone/hydroquinone derivatives obtained from myrcene.

| Comp. | Type | R | R1 | R2 | EC50 (μM) |

CC50 (μM) |

SIp | SIa | IC50 (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. infantum promastigotes | L. infantum amastigotes | Human HepG2 | Leishmanial TopIB |

|||||||

| 1 | NQ | I | Cl |  |

22.8 ± 0.6 | >100 | 50.1 ± 2.4 | 2.2 | <0.50 | 23.5 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | NQ | I | Br | Br | 11.7 ± 0.1 | 90.0 ± 4.3 | 14.7 ± 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.16 | 13.5 ± 0.6 |

| 3 | NQ | I | Br |  |

>100 | 12.8 ± 1.5 | 160 ± 12 | <1.6 | 12 | >100 |

| 4 | NQ | I |  |

H | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 7.74 ± 0.07 | 10.8 ± 0.8 | 18.9 | 1.4 | 50.1 ± 5.0 |

| 5 | NQ | II | Cl | H | 18.8 ± 0.6 | >100 | 104 ± 8 | 5.5 | <1.0 | >100 |

|

6 |

NQ |

II |

Cl |

|

11.4 ± 0.5 |

28.8 ± 1.4 |

131 ± 6 |

11.5 |

4.5 |

73.5 ± 3.4 |

| 7 | NHQ | II | H | H | 7.19 ± 0.17 | 7.18 ± 0.28 | 4.33 ± 0.28 | 0.6 | 0.60 | >100 |

| 8 | NHQ | II | CH3 | H | 12.7 ± 0.3 | 5.71 ± 0.59 | 28.0 ± 1.2 | 2.2 | 4.9 | >100 |

| 9 | NHQ | II | OCH3 | H | 15.3 ± 0.3 | 50.3 ± 0.3 | 28.6 ± 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.57 | >100 |

| 10 | NHQ (5,8-dihydro) | II | CH3 | H | 10.9 ± 0.5 | 3.61 ± 0.69 | > 200 | >18.3 | > 55 | >100 |

|

11 |

NHQ |

|

H |

H |

6.19 ± 0.03 |

17.8 ± 1.2 |

7.66 ± 0.26 |

1.2 |

0.43 |

>100 |

| 12 | 1,4-AQ | – | H | H | 1.20 ± 0.08 | 23.0 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 1.3 | 11.2 | 0.58 | 10.7 ± 2.2 |

| 13 | 1,4-AQ | – | OCH3 | H | 7.56 ± 0.14 | 14.2 ± 2.5 | 29.7 ± 1.3 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 91.8 ± 8.2 |

| 14 | 1,4-AQ | – | OEt | H | 16.1 ± 0.8 | 14.8 ± 1.9 | 199 ± 14 | 12.4 | 13 | >100 |

| 15 | 1,4-AQ | – | NHEt | H | 19.9 ± 1.7 | 33.8 ± 5.2 | 149 ± 9 | 7.5 | 4.4 | >100 |

| 16 | 1,4-AQ | – | NHEt | Cl | 12.5 ± 0.0 | 66.6 ± 3.3 | > 200 | 16.0 | >3.0 | >100 |

|

17 |

1,4-AQ |

– |

|

H |

13.5 ± 0.4 |

16.3 ± 2.1 |

> 200 |

14.8 |

> 12 |

>100 |

| 18 | 1,4-AHQ (9,10-dihydro) | – | H | H | 15.9 ± 1.1 | 1.22 ± 0.01 | 37.0 ± 2.1 | 2.3 | 30 | >100 |

| 19 | 1,4-AHQ | – | H | H | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 2.64 ± 0.01 | 5.94 ± 0.31 | 1.8 | 2.3 | >100 |

|

20 |

1,4-AHQ |

– |

OCH3 |

H |

16.6 ± 0.4 |

19.3 ± 1.6 |

54.6 ± 5.3 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

>100 |

| 21 | 9,10-AQ | II | H | H | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 21.5 ± 1.1 | 57.8 ± 1.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 57.9 ± 4.1 |

| 22 | 9,10-AQ |  |

H | H | 57.5 ± 0.2 | 44.8 ± 1.6 | 147 ± 11 | 2.5 | 3.3 | >100 |

| 23 | 9,10-AQ (4a,9a-dihydro) | II | H | H | 69.6 ± 8.4 | >100 | 82.9 ± 5.3 | 1.2 | >0.83 | >100 |

| 24 | 9,10-AQ (4a,9a-dihydro) |  |

H | H | 85.4 ± 2.5 | 21.6 ± 2.4 | >200 | 2.3 | >9.3 | >100 |

|

25 |

BAcQ |

|

39.0 ± 4.3 |

24.9 ± 0.30 |

124 ± 8 |

3.2 |

5.0 |

41.4 ± 7.4 |

||

| MTF | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 2.40 ± 0.21 | 50.4 ± 4.3 | 8.5 | 21 | nt | ||||

| AMB | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | nt | un | un | nt | ||||

SIp: Selectivity Index for promastigotes (CC50 HepG2/EC50 promastigotes); SIa: Selectivity Index for amastigotes (CC50 HepG2/EC50 amastigotes); MTF: Miltefosine; AMB: Amphotericin B deoxycholate; nt: not tested; un: undefined. Significant values (EC50: ≤10 μM, SI: ≥ 10, and CC50 ≥ 100 μM) are bolded for comparison purposes.

Table 2.

Structures and bioactivity data for terpenyl-quinone/hydroquinone derivatives obtained from diterpenoids.

| Comp. | Type | R | EC50 (μM) |

CC50 (μM) |

SIp | SIa | IC50 (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. infantum promastigotes | L. infantum amastigotes | Human HepG2 | Leishmanial TopIB |

|||||

| 26 | DNHQ |  |

11.7 ± 0.3 | 4.01 ± 0.50 | 10.5 ± 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.6 | >100 |

| 27 | DNHQ |  |

0.33 ± 0.01 | 4.34 ± 0.49 | 1.95 ± 0.26 | 5.9 | 0.45 | >100 |

| 28 | DNHQ |  |

0.29 ± 0.01 | 2.56 ± 0.16 | 3.38 ± 0.33 | 11.6 | 1.3 | >100 |

| 29 | DNHQ |  |

0.66 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.05 | 2.24 ± 0.38 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 78.4 ± 17.1 |

| 30 | DNHQ |  |

3.45 ± 0.03 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 1.59 ± 0.08 | 0.5 | 1.1 | >100 |

| 31 | DNHQ |  |

0.29 ± 0.01 | 4.24 ± 0.53 | 3.40 ± 0.36 | 11.7 | 0.80 | >100 |

| 32 | DNHQ |  |

2.28 ± 0.02 | 2.46 ± 0.10 | 0.95 ± 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.39 | >100 |

| 33 | DNHQ |  |

2.95 ± 0.20 | 1.92 ± 0.01 | 11.3 ± 2.0 | 3.8 | 5.9 | >100 |

| 34 | DNHQ |  |

76.0 ± 8.1 | 54.6 ± 5.6 | 182 ± 6 | 2.4 | 3.3 | >100 |

| 35 | DNHQ |  |

5.97 ± 0.13 | 11.8 ± 1.6 | 10.4 ± 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.88 | >100 |

| 36 | DAQ |  |

>100 | 30.9 ± 3.7 | 96.6 ± 5.9 | <1 | 3.1 | >100 |

| 37 | HetNQ |  |

14.0 ± 0.5 | 7.23 ± 0.23 | 87.6 ± 4.3 | 6.3 | 12 | >100 |

| MTF | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 2.40 ± 0.21 | 50.4 ± 4.3 | 8.5 | 21 | nt | ||

| AMB | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | nt | un | un | nt | ||

SIp: Selectivity Index for promastigotes (CC50 HepG2/EC50 promastigotes); SIa: Selectivity Index for amastigotes (CC50 HepG2/EC50 amastigotes); MTF: Miltefosine; AMB: amphotericin B deoxycholate; nt: not tested; un: undefined. Significant values (EC50: ≤10 μM, SI: ≥ 10 and CC50 ≥ 100 μM) are bolded for comparison purposes.

2.2. In vitro assays

All compounds were assayed in vitro against L. infantum BCN150 iRFP promastigotes (iRFP-L. infantum), a genetically modified strain that constitutively produces the infrared fluorescent protein (iRFP) for near infrared detection (Calvo-Álvarez et al., 2015b). Promastigotes were cultured in M199 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 6.9, 7.6 mM hemin, 10 mM glutamine, 0.1 mM adenosine, 0.01 mM folic acid, 1xRPMI 1640 vitamin mix (Sigma), 10% (v/v) heat inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Cultures of iRFP-L. infantum promastigotes with a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, were dispensed into 96-well optical bottom black plates (Thermo Scientific), 180 μL per well. Each compound was tested adding 20 μL of different stock solutions to the inoculated wells. Stock solutions were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and serially diluted in M199 media (0.01–200 μM final concentrations). The viability of promastigotes to calculate the 50% effective concentration (EC50) values was assessed measuring their fluorescence at 713 nm in an Odyssey (Li-Cor) infrared imaging system after 72 h exposure at 26 °C. All compounds and controls were assayed by triplicate. Plots were fitted by nonlinear analysis using the Sigma Plot 10.1 statistical package.

2.3. Ex vivo murine splenic explant cultures

Primary infected splenic explants were obtained inoculating intraperitoneally 108 iRFP-L. infantum metacyclic promastigotes to female BALB/c mice. After five weeks, mice were sacrificed and spleens were aseptically extracted, washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cut in small pieces and incubated with 5 mL of 2 mg/mL collagenase D (Sigma) prepared in buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1.8 mM CaCl2) for 20 min, so as to obtain a single cell suspension. The cell suspension was passed through a 100 μm-mesh cell strainer, harvested by centrifugation (500×g for 7 min at 4 °C), washed twice with PBS and resuspended in RPMI medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1xRPMI 1640 vitamin mix, 10% (v/v) FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Different concentrations of the tested compounds (0.01–200 μM) were added to these cells seeded in 384-well black optical bottom plates at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. The viability of iRFP-L. infantum amastigotes infecting macrophages was calculated by recording the fluorescence at 713 nm by an Odyssey (Li-Cor) infrared imaging system. The EC50 value was calculated by plotting the infrared fluorescence emitted by viable amastigotes against different concentrations of the tested compounds after 72 h of exposure. Plots were fitted by nonlinear analysis using the Sigma Plot 10.1 statistical package.

2.4. Selectivity index (SI) determination

Each compound was tested on human hepatocarcinoma cell HepG2 line (ATCC HB-8065) as a suitable in vitro toxicity model system of human hepatocytes. HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. The Glutamax Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Gibco) was used as cultured medium, supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Serial dilutions of each compound ranging from 0.01 to 200 μM were added to the cultures and the viability of HepG2 cells after 72 h of exposure was measured using the Alamar Blue staining method, according to manufacturer's recommendations (Invitrogen). The resulting plots of cell viability vs the concentration of each compound were adjusted by non-linear analysis using the Sigma Plot 10.1 statistical package and used to calculate the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50). Selectivity indexes (SI) for each compound were calculated as the ratio between the CC50 values obtained for HepG2 cells and the EC50 values for promastigotes (SIp) and for amastigotes obtained with ex vivo murine splenic explant cultures (SIa).

2.5. Purification of leishmanial DNA topoisomerase IB (LTopIB)

Expression and purification of LTopIB was carried out as described previously (Villa et al., 2003). Briefly, LTopIB was purified from yeast strain EKY3 deficient in TopIB activity (MATα, ura3-52, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, top1Δ:TRP1 ), that carries the bicistronic expression vector pESC-URA containing both subunits of LTopIB. Yeast were grown in yeast synthetic drop-out medium without uracil (Sigma) supplemented with 2% raffinose (w/v) to OD600: 0.8–1 and induced for 10 h with 2% galactose (w/v). Cells were harvested, washed with cold TEEG buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol) and resuspended in 15 mL of 1 x TEEG buffer supplemented with 0.2 M KCl and a protease inhibitors cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Protein extract, obtained lysing yeast cells, was loaded on a 5 mL P-11 phosphocellulose column (Whatman International Ltd. England). LTopIB protein was eluted at 4 °C with a discontinuous gradient of KCl (0.2, 0.4, 0.6 M) in TEEG buffer. The fractions eluted with 0.6 M KCl in TEEG buffer were supplemented with 50% glycerol and stored at −20 °C prior to using in enzyme assays.

2.6. TopIB relaxation activity assay

LTopIB activity was measured by the relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA. One unit of purified LTopIB (enzyme needed to relax 0.5 μg of supercoiled DNA during 30 min at 37 °C) was incubated with different concentrations of each compound for 15 min at 4 °C. Then, in a final volume of 20 μL was added the reaction mixture containing 0.5 μg of supercoiled pBluescript SK(−) plasmid, 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 15 μg/mL bovine serum albumin and 150 mM KCl. Reaction mixtures were incubated 30 min at 37 °C and stopped by the addition of 4 μL loading buffer (5% sarkosyl, 0.12% bromophenol blue, 25% glycerol). The topoisomers were resolved in 1% agarose gels by electrophoresis in 0.1 M Tris borate EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at 2 V/cm for 16 h and visualized with UV illumination after ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) staining. The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) values of LTopIB inhibition were determined as the 50% reduction of supercoiled DNA, plotting the percentage of supercoiled DNA vs drug concentrations. Plots were fitted by nonlinear analysis using the Sigma Plot 10.1 statistical package.

2.7. Molecular docking studies

Our model for LTopIB was based on the PDB structure 1T8I (Staker et al., 2005) corresponding to the ternary complex of hTopIB-DNA-CPT. Homology modeling of the two subunits of LTopIB was carried out using SWISS-Model (Bienert et al., 2017; Waterhouse et al., 2018) and the aforementioned 1T8I structure as a template. The LTopIB-DNA-CPT complex was placed in the centre of a cubic water box large enough to contain the protein complex and at least 15 Å of solvent on all sides. To mimic the intracellular conditions, K+ and Cl− were added to the system to account for a 0.15 M KCl concentration. Coordinates of the hydrogen atoms were generated with CHARMM (Brooks et al., 2009) using standard protonation states for all the titrable residues, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were run using NAMD (Phillips et al., 2005), the CHARMM36 force-field (Hart et al., 2012; Best et al., 2012), and Particle Mesh Ewald method to account for the electrostatics of the periodic boundary conditions (Darden et al., 1993). A 2 fs time step and the ShakeH algorithm were used (Ryckaert et al., 1977). Throughout the 20 ns of MD simulations at constant temperature (303.15 K) and pressure (1 bar) the structure was stable, and CPT did not leave its pocket, intercalated between the DNA chains. The coordinates of the protein and DNA chains of last frame of the MD simulations were extracted for the subsequent docking stage.

Docking of compounds 1–25 was carried out using Autodock-Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010). To further validate our model, we extracted the coordinates or the most stable poses for AQ 12 and AQ 17 to carry out further 50 ns MD simulations for the AQ 12 (or AQ 17)-TopIB-DNA complex at the same conditions described above. Throughout these simulations the ligands remained in the active site, close to their docking conformations (in particular AQ 17 as its size is significantly larger). Parameters for CPT, AQ 12, and AQ 17 were assigned using ParamChem (accessible at https://cgenff.umaryland.edu) (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2010).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Activity of terpenylquinones against L. infantum

A family of thirty-seven NQ, AQ and BAcQ derivatives synthesized and previously evaluated as antifungals and antineoplastics (Castro et al., 2013a; Castro et al., 2015; Miguel del Corral et al., 1998; Miguel del Corral et al., 2001; Miguel del Corral et al., 2007; Chamorro, 2002; Rodríguez, 2006) were assessed in vitro against free-living axenic promastigotes and ex vivo against amastigotes infecting mouse splenic cells. In this regard, we used a recombinant iRFP-L. infantum strain that constitutively produces the infrared fluorescent protein (iRFP) and emits near infrared fluorescence at 713 nm without the necessity of adding external substrates. The ability of this parasitic strain to evaluate the in vitro and ex vivo efficacy of other series of compounds has been proven in previous works by the authors (Escudero-Martínez et al., 2017).

To go further into the potential usefulness of these quinone/hydroquinones as antileishmanial agents, the viability of mammalian HepG2 cancer cell line, a human model for studies of liver drug toxicity, was assessed after exposing the cells to the compounds and the corresponding cytotoxic concentration CC50 values were determined. Ex vivo infected splenocytes, free-living promastigotes and HepG2 liver cells were incubated with the testing compounds as described in Materials and methods. After drug treatments, the parasite viability was determined by the infrared fluorescence emitted by living parasites, whereas Alamar Blue was added to assess the percentage of viable hepatic cells. The EC50 values, defined as the concentrations of the compounds that resulted in 50% parasite growth arrest, were compared to the CC50 values obtained from HepG2 cells to calculate selectivity index values (SI) (Table 1, Table 2).

Compounds tested are listed in Table 1, Table 2 grouped according their terpenic precursor (monoterpenoid or diterpenoid) and their quinone/hydroquinone nature. Table 1 includes terpenylnaphtho-quinones/hydroquinones (NQ/NHQs 1–11), anthra-quinones/hydroquinones (1,4-AQ/1,4-AHQs 12–20, 9,10-AQs 21–24) and the benzoacridinequinone (BAcQ) 25, all of them obtained from the monoterpenoid myrcene. Considering as potential “hit” those compounds that inhibit the 50% growth of intra-macrophage amastigotes at concentrations below 10 μM, six compounds out of twenty-five (4, 7, 8, 10, 18 and 19) were able to arrest the growth of this parasite form. In addition, derivatives 4, 7 and 19 together with three other compounds (11–13) showed EC50 values below 10 μM for promastigotes.

Considering the oxidation degree of the quinone moiety, the diacetylated hydroquinone derivatives, NHQs and 1,4-AHQs, provided better results than those analogues with an unmodified quinone ring, NQs, 1,4-AQs and 9,10-AQs. Five out of those six hits mentioned above belong to the NHQ and 1,4-AHQ groups. The NHQs 7 (EC50 = 7.18 μM), 8 (EC50 = 5.71 μM) and 10 (EC50 = 3.61 μM) and more actively, the 1,4-AHQs 18 (EC50 = 1.22 μM) and 19 (EC50 = 2.64 μM) reduced the amastigotes growth below 10 μM and, in addition, compound 18 was twice as potent as miltefosine (MTF) used as reference drug against amastigotes. Interestingly, the 2-methyl-NHQ 10 and the 1,4-AHQ 18 were relatively safe with CC50 > 200 μM and 37.0 μM respectively, for host's HepG2 cells, yielding SIa values > 55 and 30. In addition to their significance about the relative toxicity of the compounds tested, the SI values turn out to be useful to make comparisons of bioactivity within each and between both series of compounds. Compounds with SI greater than 10 can be considered possible candidates to be optimized in order to improve their efficacy and selectivity, and thus be included in future biopharmaceutical and preclinical studies (Katsuno et al., 2015).

Among the NQ and AQ derivatives, only NQ 4, bearing a dimethoxyphenoxy substituent, had an EC50 below 10 μM, being much more potent against promastigotes (EC50 = 0.57 μM) than against intracellular amastigotes (EC50 = 7.74 μM). In fact, the potency of this compound against promastigotes was in the same range as that of AMB, the most potent antileishmanial reference drug used in the study.

Regarding the size of the quinone moiety, the introduction of an additional ring, from NQ to AQ systems either 1,4-AQ or 9,10-AQ, did not enhance the antiparasitic activity. In general, the compounds tested were barely toxic on HepG2 hepatocytes, being of interest those compounds with SI values over 10, as the already mentioned compounds 10 and 18 with SIa > 55 and 30 on the amastigote form of the parasite, respectively. Other interesting derivatives were the NQ 3 and the 1,4-AQs 14 and 17 with SIa values of 12, 13 and > 12 respectively, despite presenting EC50 values on amastigotes over 10 μM (EC50 = 12.8, 14.8 and 16.3 μM, respectively); so they could be considered relatively safe for human HepG2 cells (CC50 160, 199 and > 200 μM). Compounds 10, 14 and 17 had also a SI > 10 on promastigotes with values of SIp > 18.3, 12.4 and 14.8, respectively.

The structures of those naphthohydroquinone derivatives obtained from the diterpenoid myrceocommunic acid are listed in Table 2 (DNHQs 26–37). Different modifications were introduced in the diterpenyl moiety, mainly in the carboxylic group at C-4 position, in the double bond Δ8(17) and in the chain joining the decaline rest to the naphthohydroquinone core.

With the exception of 36, the only AQ derivative in this series, all of them were active against both promastigotes and amastigotes within the μM or lower range. Unfortunately, the cytotoxicity of these compounds for host HepG2 cells was undifferentiable from the effect on the parasite forms, yielding SI values around one. Only the DNHQ 28 and 31 showed a SIp values close to 12. Table 2 include also the pyrazole-fused NQ 37, which is the only derivative in this series with an interesting SIa value of 12.

3.2. Inhibition of leishmanial DNA topoisomerase IB

The presence of polycyclic systems in the structure of these compounds aimed us to assess their inhibitory potential on purified recombinant LTopIB measuring the relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA as described in Material and methods section. In this regard, all terpenylquinone derivatives were assessed for LTopIB inhibition through the prevention of DNA relaxation of a circular plasmid DNA. All compounds were tested at a single concentration of 100 μM, to discard those compounds that did not prevent DNA relaxation by LTopIB. After this initial test, potential inhibitors dose/response curves were performed to obtain their IC50 values.

First, as it could be expected, only some compounds that conserve the oxidized quinone system were able to prevent the relaxation of supercoiled DNA, but none of the diacetylated hydroquinones inhibited the enzyme (Table 1, Table 2). Considering the terpenylquinone derivatives obtained from myrcene, the group with more inhibitors found was the integrated by NQ derivatives. Within this group, four out of six molecules were LTopIB inhibitors, getting the best IC50 value for the dibrominated NQ 2 (IC50 = 13.5 μM) followed by the anilino-chloro disubstituted NQ 1 (IC50 = 23.5 μM). Among the compounds with some LTopIB inhibition effect, the lowest IC50 value corresponded to the unsubstituted 1,4-AQ 12 (IC50 = 10.7 μM). Any structural modifications applied to this molecule led to a reduction of the LTopIB inhibition. The NQ 4, the 9,10-AQ 21 and the BAcQ 25 weakly inhibited LTopIB in vitro, being the weakest inhibitors NQ 6 and 1,4-AQ 13. Several efforts to find correlations between antileishmanial activity and LTopIB inhibition were unsuccessful, with only NQ 4 showing a good leishmanicidal activity with weak LTopIB inhibition. These facts suggest the probable existence of alternative mechanisms of action or different targets that need further research.

3.3. Molecular docking study on LTopIB

Attempting to prove if the planar or quasi-planar quinonic compounds could intercalate into DNA and simultaneously inhibit the catalytic effect of LTopIB, and trying to understand the lack of correlations between the antileishmanial activity and the LTopIB inhibition, the terpenylquinones derived from myrcene 1–25 were subjected to a molecular docking analysis on a model system of LTopIB. This model was built using the ternary complex of TopIB-DNA-CPT as a template (PDB code: 1T8I (Staker et al., 2005), and was further equilibrated through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Details of the system preparation are described in Material and methods section.

Docking of the terpenylquinones 1–25 was carried out using Autodock-Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010), obtaining the results displayed in Table 3 and Table S1 (Supplementary material) and Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Figs. S1–S2. Most of the compounds behaved as virtual intercalating agents similar as CPT, where the aromatic rings of the terpenylquinones interact strongly with the DNA base pairs through π-stacking interactions. Accordingly, terpenylquinones could be considered as enzymatic poisons. Moreover, the ligands also interact with the protein through H-bonds and other binding contacts as shown in Table 3, in which the binding free energy values have also been compiled, and in the interaction complexes 2D maps shown in Fig. S1. Overall, the terpenylquinones interact strongly with the DNA-LTopIB complex showing binding energies (ΔG) between −8.3 and −11.6 kcal/mol. The average ΔG is 10.1 ± 0.9 kcal/mol, and the largest deviations could be explained based on the different molecular weight of the ligands. Indeed, ligands with larger π-systems show larger ΔG.

Table 3.

Docking interactions, calculated free energy values and in vitro inhibition values on LTopIB for selected terpenylquinones.

| Compd. | H-bonds | Other binding contactsa |

ΔG (kcal/mol)b | IC50 (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| 1 | Arg190 | + | – | + | + | −9.5 | 23.5 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | - | + | – | + | – | −8.8 | 13.5 ± 0.6 |

| 4 | - | + | – | + | + | −10.6 | 50.1 ± 5.0 |

| 6 | Arg190 | – | – | + | – | −10.2 | 73.5 ± 3.4 |

| 12 | Arg190 | + | – | + | – | −9.6 | 10.7 ± 2.2 |

| 13 | Arg190 | + | – | + | – | −10.2 | 91.8 ± 8.2 |

| 14 | Arg190 | + | – | + | – | −10.3 | >100 |

| 15 | Arg190 | + | – | + | – | −10.3 | >100 |

| 17 | Arg190, Asn221 | + | + | + | + | −11.6 | >100 |

| 21 | Arg190 | – | – | + | – | −8.7 | 57.9 ± 4.1 |

| 25 | Arg190 (dual) | – | + | – | + | −11.5 | 41.4 ± 7.4 |

| CPT | Arg190, Asp353 | – | + | – | + | −12.2 | 2.8* |

Enzyme fragments involved in LTopIB - quinone contacts: region A: Ala177-Lys200; region B: Thr217-Asn221; region C: Met250-Pro257; region D: Lys352-Asp353. See Suppl. Material, Table S1 and Fig. S1, for more detailed information.

Best free energy values and best experimental results are in bold for better comparisons. *CPT IC50 was obtained from reference (Roy et al., 2008).

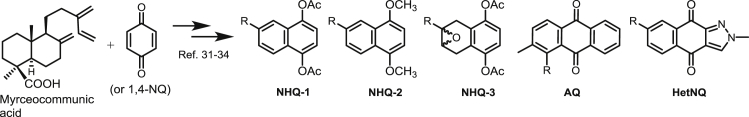

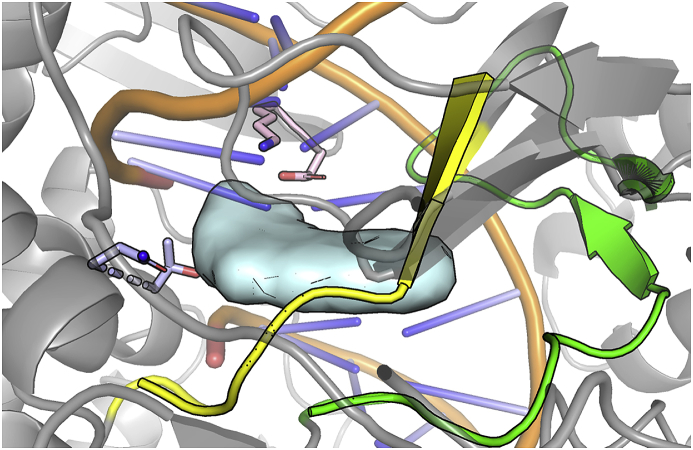

Fig. 2.

Conformation of the CPT pocket. CPT structure is shown as a cyan surface and, around them, the different regions that interact with the terpenylquinones have been highlighted. Region A, residues between Ala177 and Lys200, is shown as green cartoon. Region B includes Thr217 and Asn221, which are shown as blue sticks. Region C, residues between Met250 and Pro257, is shown as yellow cartoon. Region D is formed by the residues Lys352 and Asp353, that are shown as pink sticks. It should be noticed that all these residues belong to the large subunit of LTop1B, but Thr217 and Asn221 belong to the small subunit. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

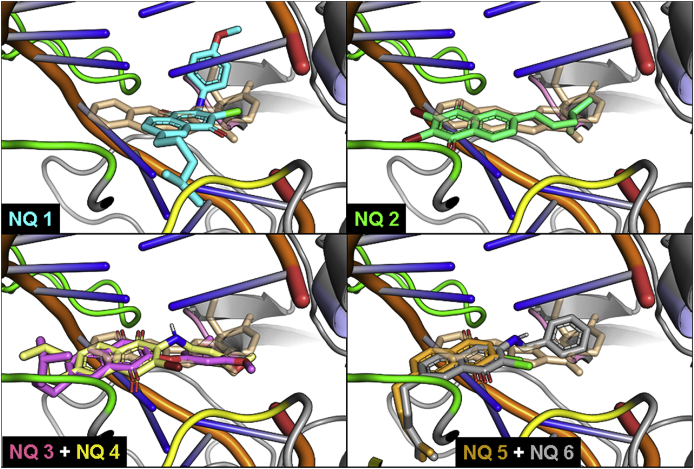

Fig. 3.

Superimposed docking complexes of naphthoquinones NQs 1–6 and CPT with DNA-LTopIB complex. The structures shown correspond to the most stable pose predicted by Autodock-VINA for NQs 1–6. Both CPT and the tested ligands are shown atomistically, with CPT displayed as transparent wheat sticks. The regions A-D (see Fig. 2), are shown as green, blue, yellow, and pink cartoons, with the rest of the protein shown as grey cartoons. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

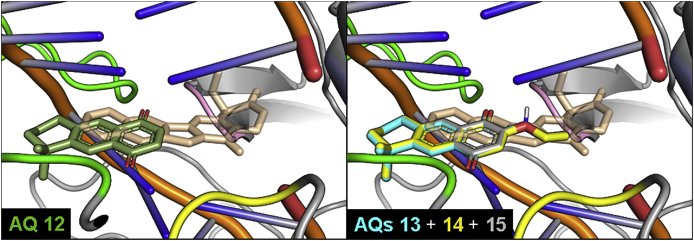

Fig. 4.

Superimposed docking complexes of 1,4-anthraquinones 12 and 13–15 and CPT with DNA-LTopIB complex. The structures shown correspond to the most stable pose predicted by Autodock-VINA for AQs 12–15. Structures are shown and colored as in Fig. 3.

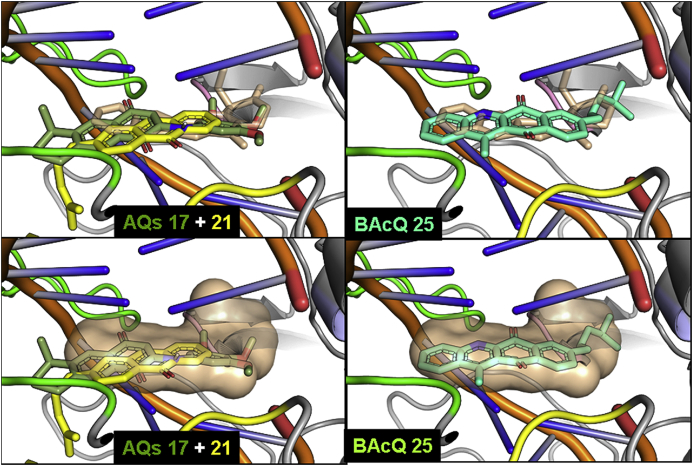

Fig. 5.

Superimposed docking complexes of the 1,4-AQ 17, the 9,10-AQ 21 and CPT (left column) and BAcQ 25 and CPT (right column) with DNA-LTopIB complex. Structures are colored according to Fig. 3, Fig. 4. Images in the bottom row represent the CPT as a surface to better observe the arrangement of the three different quinones 17, 21 and 25 in the space delimited by the docked reference drug.

In Fig. 2 and Table 3, the amino acids involved in H-bonding interactions with the quinones can be observed, while complete specific interactions are shown in Table S1 and in the 2D maps (Fig. S1). As it is illustrated in Fig. 2, the ligands and the enzyme interact through four different regions: the Ala177 - Lys200 region (region A), in which H-bonds between Arg190 and most of the quinones stand out; the region delimited by Thr217 - Asn221 (region B), with a H-bond between Asn221 and the trimethoxyphenyl derivative AQ 17, while displaying only soft contacts with CPT; the Met250 - Pro257 region (region C), which generates binding contacts with several NQs and AQs, but not with CPT; and finally, the region constituted by Lys352 and Asp353 (region D), associated by H-bonding to CPT and by other contacts to several NQs and AQs.

The compounds with the highest docking binding energies (ΔG) were the NQs 4 and 6, the AQs 13, 14, 15 and 17, and the BAcQ 25, however most of them showed low or null experimental inhibition of LTopIB despite having similar interactions as CPT, which is used as model. Actually, the differences in the docking energies are caused by the strength of the ligand-DNA interaction (π-π stacking formed between the aromatic rings of the DNA basis and the ligands). Accordingly, we cannot rule out the possibility that the ligand intercalate between the DNA strands without binding to LTopIB. The most stable docking poses for the selected quinones in the CPT site of the DNA-LTopIB complex are shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Fig. S2.

Fig. 3 contains the docking complexes for NQs 1–6 and CPT. It can be observed that the NQ moiety common to all the NQs intercalates into DNA, in a disposition almost coplanar with the polycyclic system of CPT, though with differences in the accommodation of the flexible lipophilic and less interactive aliphatic prenyl side-chain, and most notably in the case of NQ 1, due to the presence of the bulkier and more rigid p-methoxyanilino substituent at the quinone ring.

Fig. 4 contains the ternary complexes of several AQs and CPT. It can be observed that the molecules are fairly displaced with respect to the polycyclic system of CPT, and even somewhat outside the intercalating area of DNA, due to the hindrance caused by the dimethyl substitution at the third non-planar ring.

In the left column of Fig. 5, the differences between the most stable docking poses of 1,4- and 9,10-AQs can be observed. The isoprenyl chain of AQ 21, more flexible than the dimethyl substitution of AQ 17, though lying outside the DNA helix, allows a better and more centered intercalation of the AQ into DNA. Nevertheless, the binding energy of AQ 17 (11.6 kcal/mol) results much stronger than that of AQ 21 (8.7 kcal/mol), surely due to the presence of the trimethoxyphenyl group in the former and its expected interactions with the nucleic bases, reinforced by the H-bonding between one methoxy group and the TopIB amino acid Asn221 (Table 3). In the right column of Fig. 5, the complexes of CPT and the BAcQ 25 can be observed, to show the similarity of docking of both compounds, with a good fitting of BAcQ 25 into the CPT surface. This fact, together with the actual leishmanicidal activity of 25, would support the interest for the opening of a new research line with BAcQ 25 as the lead compound.

As another relevant fact, docking studies predicted that AQ 17 should be a better LTopIB inhibitor than AQ 12. However, our measurements showed that a significant experimental inhibition was found for AQ 12 but not for AQ 17. To find out the origin of this discrepancy, we calculated throughout the MD simulation the interaction energy between the ligands and the DNA-protein-solvent system by computing the non-bonding interaction using the force field parameters. Throughout the simulations the ligands did not move outside the active site, and the interaction energies calculated showed that the interaction between AQ 17 and the DNA-LTopIB complex is stronger than between AQ 12 and the complex (104 ± 9 kcal/mol vs – 60 ± 5 kcal/mol respectively). We compared these results with the interaction energies obtained for a model system where the ligand was located in the centre of a cubic box of water. In the latter case the interaction energies between the ligands and water were −88 ± 9 kcal/mol for AQ 17 and only −44 ± 5 kcal/mol for AQ 12. The large difference between these two values could be explained in terms of the relatively large difference of size between the two ligands. If we calculate the ratio between the interaction energies in LTopIB and water we obtain 1.18 for AQ 17 and 1.35 for AQ 12, showing that the equilibrium is more displaced towards the formation of the complex for AQ 12 than for AQ 17. This simple analysis does not consider the effect of the entropy. To take it into account we should carry out binding free energy simulations that are beyond the scope of the present work. In addition, we must consider that there could be another, yet undefined, alternative or complementary mechanism of action for those quinones experimentally active as LTopIB inhibitors, but with low calculated binding energy values, as NQs 1, 2 and 12; whereas for those inactive and less active quinones displaying high binding energy values, as AQ 17 and BAcQ 25, possible difficulties of accessing to the Top IB-DNA interaction site could be the reason. In all, further virtual and experimental confirming studies, including the consideration red-ox and Michael electron-acceptor properties of quinones, should be done in order to characterize completely the mechanism of action for this family of compounds.

3.4. In silico pharmacokinetic and toxicity evaluation

Compounds with best leishmanicidal activity and weak cytotoxic effect on HepG2 cells (SI > 10) were submitted to in silico pharmacokinetic properties and adverse effects prediction. To predict the druggability of the selected hits, we analysed the parameters related to Lipinski's rule of five, absorption, metabolism and toxicity, provided by SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php), preADMET (https://preadmet.bmdrc.kr/) and admetSAR (http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar1/predict/) servers, freely accessible web-based applications. The data obtained are collected in Table S2 (supplementary material). All the compounds showed good druggability since they fulfilled Lipinski's rule of five and showed acceptable non-rotatable bond (n-ROTB) values (≤10). Predicted human intestinal absorption (HIA) and Caco2 absorbability were positive for all compounds. In the case of metabolism, various isoforms of cytochrome P450 (CYP) were evaluated, showing different patterns for NQ 3, NHQ 10, AQs 14 and 17 than for AHQ 18 and pyrazole-fused NQ 37. In terms of toxicity, none of the compounds showed mutagenic toxicity in the AMES test nor rodent carcinogenic effects.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the antileishmanial properties of a family of terpenylquinone/hydroquinone derivatives were examined both in vivo and ex vivo against the transgenic iRFP-L. infantum strain. As a general conclusion, the NQ/NHQ derivatives showed better antileishmanial activity than the larger AQ/AHQ derivatives, and among them, those compounds with an acetylated hydroquinone moiety provided better results than those corresponding unaltered quinones. Regarding the size of the terpenic precursor, those compounds obtained from the commercial monoterpenoid myrcene displayed good antiparasitic efficiency and low cytotoxicity for mammalian cells, whereas those derived from the isolated natural diterpenoid myrceocommunic acid showed better antileishmanial activity, but without selectivity.

Parallel studies were carried out to explore their mechanism of action. To this end, all the compounds were tested as potential inhibitors of LTopIB, but only several quinones were able to inhibit the recombinant enzyme in vitro. The compounds that inhibited LTopIB were those that displayed less safety in vitro, thus pointing to a common interaction target in both Leishmania and host cells. Attempts to correlate the antileishmanial properties of the compounds tested with the LTopIB inhibition were unsuccessful, and only NQ 4 resulted as good antileishmanial against both stage of L. infantum and weak LTopIB inhibitor simultaneously. Several docking studies performed on LTopIB concluded that those terpenylquinones with the best binding energies were the NQs 4 and 6, the AQs 13, 14, 15 and 17, and the BAcQ 25. Regrettably most of them showed low or null experimental inhibition of LTopIB despite having similar interactions at the active site compared with CPT used as model. These results clearly suggest that inhibition of LTopIB is just a complementary/additional target in killing Leishmania parasites and a major mechanism of action, probably affecting the parasite anti-oxidant toolbox, is involved (García-Barrantes et al., 2013; Bolton et al., 2000; Awasthi et al., 2016).

Moreover, the compounds of choice displayed good predictable druggability and low in vivo toxicity, as reflected by the absence of genotoxicity and carcinogenicity and the fulfilment of the ADMET properties. Finally, it should to be mentioned that further studies are necessary to determine their exact mechanisms of action and consider the possibility to improve efficiency using them in combined therapies.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article (Table S1, Table S2, Fig. S1 and Fig. S2) can be found online.

Note

Supplementary data associated with this article.

Acknowledgments

Financial support came from Spanish MINECO (CTQ2015-68175-R, AGL2016-79813-C2-1-R, AGL2016-79813-C2-2-R and SAF2017-83575-R), ISCIII-RICET Network (RD12/0018/0002) and Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Castilla y León (LE020P17) co-financed by the Fondo Social Europeo of the European Union (FEDER-EU). P. G. J. acknowledges funding by Fundación Salamanca Ciudad de Cultura y Saberes (’‘Programme for attracting scientific talent to Salamanca’‘)

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpddr.2019.10.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aït-Oudhia K., Gazanion E., Vergnes B., Oury B., Sereno D. Leishmania antimony resistance: what we know what we can learn from the field. Parasitol. Res. 2011;109:1225–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A., Assimopoulou A.N., Papageorgiou V.P., Kolodziej H. Structure/antileishmanial activity relationship study of naphthoquinones and dependency of the mode of action on the substitution patterns. Planta Med. 2011;77:2003–2012. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo I.A.C., de Paula R.C., Alves C.L., Faria K.F., Oliveira M.M., Mendes G.G., Dias E.M.F.A., Ribeiro R.R., Oliveira A.B., Silva S.M.D. Efficacy of lapachol on treatment of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2019;199:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo M.V., David C.C., Neto J.C., de Oliveira L.A., da Silva K.C., dos Santos J.M., da Silva J.K., de A Brandão V.B., Silva T.M., Camara C.A., Alexandre-Moreira M.S. Evaluation on the leishmanicidal activity of 2-N,N'-dialkylamino-1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives. Exp. Parasitol. 2017;176:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi B.P., Kathuria M., Pant G., Kumari N., Mitra K. Plumbagin, a plant-derived naphthoquinone metabolite induces mitochondria mediated apoptosis-like cell death in Leishmania donovani: an ultrastructural and physiological study. Apoptosis. 2016;21:941–953. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaña-Fouce R., Alvarez-Velilla R., Fernández-Prada C., García-Estrada C., Reguera R.M. Trypanosomatids topoisomerase re-visited. New structural findings and role in drug discovery. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2014;4:326–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaña-Fouce R., Pérez Pertejo M.Y., Domínguez-Asenjo B., Gutiérrez-Corbo C., Reguera R.M. Walking a tightrope: drug discovery in visceral leishmaniasis. Drug Discov. Today. 2019;24:1209–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M.P., Croft S.L. Management of trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Br. Med. Bull. 2012;104:175–196. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta G.L., Ribaudo G., Menegazzo I., Supino R., Capranico G., Zunino F., Zagotto G. Synthesis and evaluation of new naphthalene and naphthoquinone derivatives as anticancer agents. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 2017;350 doi: 10.1002/ardp.201600286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best R.B., Zhu X., Shim J., Lopes P.E.M., Mittal J., Feig M., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert S., Waterhouse A., de Beer T.A.P., Tauriello G., Studer G., Bordoli L., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository—new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D313–D319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodley A.L., Chakraborty A.K., Xie S., Burri C., Shapiro T.A. An unusual type IB topoisomerase from African trypanosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:7539–7544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1330762100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J.L., Trush M.A., Penning T.M., Dryhurst G., Monks T.J. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Mackerell A.D., Jr., Nilsson L., Petrella R.J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., Caflisch A., Caves L., Cui Q., Dinner A.R., Feig M., Fischer S., Gao J., Hodoscek M., Im W., Kuczera K., Lazaridis T., Ma J., Ovchinnikov V., Paci E., Pastor R.W., Post C.B., Pu J.Z., Schaefer M., Tidor B., Venable R.M., Woodcock H.L., Wu X., Yang W., York D.M., Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burza S., Croft S.L., Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392:951–970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Álvarez E., Álvarez-Velilla R., Fernández-Prada C., Balaña-Fouce R., Reguera R.M. Trypanosomatids see the light: recent advances in bioimaging research. Drug Discov. Today. 2015;20:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Álvarez E., Stamatakis K., Punzón C., Álvarez-Velilla R., Tejería A., Escudero-Martínez J.M., Pérez-Pertejo Y., Fresno M., Balaña-Fouce R., Reguera R.M. Infrared fluorescent imaging as a potent tool for in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo models of visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.A., Gamito A.M., Tangarife-Castaño V., Roa-Linares V., Miguel del Corral J.M., Mesa-Arango A.C., Betancur-Galvis L., Francesch A.M., San Feliciano A. New 1,4-anthracenedione derivatives with fused heterocyclic rings: synthesis and biological evaluation. RSC Adv. 2015;5:1244–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.A., Gamito A.M., Tangarife-Castaño V., Zapata B., Miguel del Corral J.M., Mesa-Arango A.C., Betancur-Galvis L., San Feliciano A. Synthesis and antifungal activity of terpenyl-1,4-naphthoquinone and 1,4-anthracenedione derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;67:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro S.L., Emery F.S., da Silva E.N., Jr. Synthesis of quinoidal molecules: strategies towards bioactive compounds with an emphasis on lapachones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;69:678–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro P. University of Salamanca; Salamanca, Spain: 2002. Síntesis, reordenamiento y evaluación citotóxica de nuevas diterpenyl-1,4-naftohidroquinonas. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Shanmugasundaram K., Rigby A.C., Kung A.L. Shikonin, a natural product from the root of Lithospermum erythrorhizon, is a cytotoxic DNA-binding agent. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;49:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- De Moura K.C.G., Emery F.S., Neves-Pinto C., Pinto M.C.F.R., Dantas A.P., Salomão K., De Castro S.L., Pinto A.V. Trypanocidal activity of isolated naphthoquinones from Tabebuia and some heterocyclic derivatives: a review from an interdisciplinary study. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2001;12:325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Dorlo T.P.C., Kip A.E., Younis B.M., Ellis S.J., Alves F., Beijnen J.H., Njenga S., Kirigi G., Hailu A., Olobo J., Musa A.M., Balasegaram M., Wasunna M., Karlsson M.O., Khalil E.A.G. Visceral leishmaniasis relapse hazard is linked to reduced miltefosine exposure in patients from Eastern Africa: a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:3131–3140. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero-Martínez J.M., Pérez-Pertejo Y., Reguera R.M., Castro M.A., Rojo M.V., Santiago C., Abad A., García P.A., López-Pérez J.L., San Feliciano A., Balaña-Fouce R. Antileishmanial activity and tubulin polymerization inhibition of podophyllotoxin derivatives on Leishmania infantum. Int. J. Parasit. Drugs Drug Resist. 2017;7:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S.B., Salomão K., de Carvalho da Silva F., Pinto A.V., Kaiser C.R., Pinto A.C., Ferreira V.F., de Castro S.L. Synthesis and anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of β-lapachone analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:3071–3077. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Barrantes P.M., Lamoureux G.V., Pérez A.L., García-Sánchez R.N., Martínez A.R., San Feliciano A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel ferrocene-naphthoquinones as antiplasmodial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;70:548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart K., Foloppe N., Baker C.M., Denning E.J., Nilsson L., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Optimization of the CHARMM additive force field for DNA: improved treatment of the BI/BII conformational equilibrium. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:348–362. doi: 10.1021/ct200723y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioanoviciu A., Antony S., Pommier Y., Staker B.L., Stewart L., Cushman M. Synthesis and mechanism of action studies of a series of norindenoisoquinoline topoisomerase I poisons reveal an inhibitor with a flipped orientation in the ternary DNA-enzyme-inhibitor complex as determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4803–4814. doi: 10.1021/jm050076b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuno K., Burrows J.N., Duncan K., van Huijsduijnen R.H., Kaneko T., Kita K., Slingsby B.T. Hit and lead criteria in drug discovery for infectious diseases of the developing world. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nrd4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.J., Averboukh L., Pardee A.B. Beta-lapachone, a novel DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor with a mode of action different from camptothecin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22463–22468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel del Corral J.M., Castro M.A., Rodríguez M.L., Chamorro C., Cuevas C., San Feliciano A. New cytotoxic diterpenylnaphthohydroquinone derivatives obtained from a natural diterpenoid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:5760–5774. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel del Corral J.M., Gordaliza M., Castro M.A., Mahiques M.M., San Feliciano A., García-Grávalos M.D. Further antineoplastic terpenylquinones and terpenylhydroquinones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1998;6:31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)10007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel del Corral J.M., Gordaliza M., Castro M.A., Mahiques M.M., Chamorro P., Molinari A., García-Grávalos M.D., Broughton H.B., San Feliciano A. New selective cytotoxic diterpenylquinones and diterpenylhydroquinones. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:1257–1267. doi: 10.1021/jm001048q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge-Maillo B., López-Vélez R. Therapeutic options for visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs. 2013;73:1863–1888. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J.C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R.D., Kalé L., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A.V., de Castro S.L. The trypanocidal activity of naphthoquinones: a review. Molecules. 2009;14:4570–4590. doi: 10.3390/molecules14114570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y., Leo E., Zhang H., Marchand C. DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reguera R.M., Calvo-Álvarez E., Alvarez-Velilla R., Balaña-Fouce R. Target-based vs. phenotypic screenings in Leishmania drug discovery: a marriage of convenience or a dialogue of the deaf? Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2014;4:355–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reguera R.M., Redondo C.M., Gutierrez de Prado R., Pérez-Pertejo Y., Balaña-Fouce R. DNA topoisomerase I from parasitic protozoa: a potential target for chemotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1759:117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M.L. University of Salamanca; Salamanca, Spain: 2006. Síntesis de nuevas naftoquinonas citotóxicas a partir de diterpenoides naturales. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Das B.B., Ganguly A., Bose-Dasgupta S., Khalkho N.V.M., Pal C., Dey S., Giri V.S., Jaisankar P., Dey S., Majumder H.K. An insight into the mechanism of inhibition of unusual bi-subunit topoisomerase I from Leishmania donovani by 3,3'-di-indolylmethane, a novel DNA topoisomerase I poison with a strong binding affinity to the enzyme. Biochem. J. 2008;409:611–622. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Shakya N., Bajpai P., Gupta S. Therapeutic switching in leishmania chemotherapy: a distinct approach towards unsatisfied treatment needs. J. Parasit. Dis. 2011;35:104–112. doi: 10.1007/s12639-011-0040-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staker B.L., Feese M.D., Cushman M., Pommier Y., Zembower D., Stewart L., Burgin A.B. Structures of three classes of anticancer agents bound to the human topoisomerase I−DNA covalent complex. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:2336–2345. doi: 10.1021/jm049146p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S., Chakravarty J., Agarwal D., Rai M., Murray H.W. Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:504–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M.J., de Almeida Y.M., Viana J.R., Holanda Filha J.G., Rodrigues T.P., Prata J.R., Jr., Coêlho I.C., Rao V.S., Pompeu M.M. In vitro and in vivo leishmanicidal activity of 2-hydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone (lapachol) Phytother Res. 2001;15:44–48. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200102)15:1<44::aid-ptr685>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K., Hatcher E., Acharya C., Kundu S., Zhong S., Shim J., Darian E., Guvench O., Lopes P., Vorobyov I., MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. https://cgenff.umaryland.edu CGenFF interface is accessible at paramchem.org: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa H., Otero-Marcos A.R., Reguera R.M., Balaña-Fouce R., García-Estrada C., Pérez-Pertejo Y., Tekwani B.L., Myler P.J., Stuart K.D., Bjornsti M.A., Ordóñez D. A novel active DNA topoisomerase I in Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3521–3526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F.T., de Beer T.A.P., Rempfer C., Bordoli L., Lepore R., Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Chen Q., Wang H., Xu P., Yuan R., Li X., Bai L., Xue M. Inhibitory effects of lapachol on rat C6 glioma in vitro and in vivo by targeting DNA topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35:178. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0455-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Qu Y., Niu B. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of lapachol derivatives possessing indole scaffolds as topoisomerase I inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016;24:5781–5786. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.L., Wang P., Liu Y.H., Liu L.B., Liu X.B., Li Z., Xue Y.X. Topoisomerase I inhibitors, shikonin and topotecan, inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of glioma cells and glioma stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.