Abstract

John Tyler Bonner’s call to re-evaluate evolutionary theory in light of major transitions in life on Earth (e.g. from the first origins of microbial life, to the evolution of sex and the origins of multicellularity) resonate with recent discoveries on epigenetics and the concept of the hologenome. Current studies of genome evolution often mistakenly focus only on the inheritance of DNA between parent and offspring. These are in line with the widely accepted Neo-Darwinian framework that pairs Mendelian genetics with an emphasis on natural selection as explanations for the evolution of biodiversity on Earth. Increasing evidence for widespread symbioses complicates this narrative, as is seen in Scott Gilbert’s discussion of the concept of the holobiont in this series: organisms across the tree of life coexist with substantial influence on one another through endosymbiosis, symbioses and host-associated microbiomes. The holobiont theory, coupled with observations from molecular studies, also requires us to understand genomes in a new way -- by considering the interactions underlain by the genome of a host plus its associated microbes, a conglomerate entity referred to as the hologenome. We argue that the complex patterns of inheritance of these genomes coupled with the influence of symbionts on host gene expression make the concept of the hologenome an epigenetic phenomenon. We further argue that the hologenome challenges aspects of the modern evolutionary synthesis, which requires updating to remain consistent with Darwin’s intent of providing natural laws that underlie the evolution of life on Earth.

Keywords: holobiont, symbiosis, microbiome, evolutionary theory, epigenomics

Introduction

A common response to the question, ‘how many chromosomes are in a human cell?’ is 46, but this is inaccurate, as human cells actually have at least 47 when we include the circular chromosomes in our mitochondria. Similarly, every plant cell has three genomes that act in concert: in the nucleus, mitochondrion and chloroplast. These widely studied endosymbiotic events demonstrate how genome interactions change the evolutionary trajectories of all organisms involved. In highly intimate endosymbiotic relationships, symbiogenesis creates a new individual from multiple lineages (Martin & Kowallik, 1999; Mereschkowsky, 1910; Nowack & Melkonian, 2010). Clearly in the case of mitochondria and plastids, host and symbiont genomes evolve and function together following endosymbiosis, changing the template for evolutionary processes.

Similar to the connections among genomes following endosymbiosis, the interactions between symbionts and hosts more broadly led to the concept of the hologenome (e.g. Rosenberg, Koren, Reshef, Efrony, & Zilber-Rosenberg, 2007; Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008) and challenge our traditional understanding of an individual’s genome. Because symbionts can impact patterns of expression and inheritance of host genomes, we argue that these relationships are inherently epigenetic as they are consistent with Denise Barlow’s broad definition of epigenetics as “all the weird and wonderful things that cannot [yet] be explained by genetics” (McVittie, 2006). We do not mean to suggest that hologenomes are outside of evolutionary theory but instead, as Bonner (2019) reminds us, consideration of microbes as well as plants and animals provides valuable insights that expand evolutionary theory. Here, we discuss data on genome interactions between hosts and symbionts, highlighting the varying degrees of intimacies, to emphasize the importance of the hologenome concept and its implications for evolutionary biologists.

The hologenome

The concept of the hologenome (e.g. Rosenberg et al., 2007; Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008) emerges in part from the concept of the holobiont (e.g. Gilbert, 2019; Gilbert et al., 2010; Herre, Knowlton, Mueller, & Rehner, 1999) because inherited symbionts change host gene expression and genomes over time. Symbioses are very common in nature (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2010; McFall-Ngai, 2002) and, as a result, many eukaryotes (e.g. plants, animals, ciliates, amoebae) contain heritable symbionts that “contribute to the anatomy, physiology, development, innate and adaptive immunity, and behavior and finally also to genetic variation and to the origin and evolution of species” (Rosenberg & Zilber-Rosenberg, 2016). To realistically encompass the genetic ‘individual’ created by a host and its microbiome, Rosenberg et al. (2007) first introduced the hologenome as the sum of the genomes of a host and its symbionts, in essence, a conglomerate genome. Within a hologenome, complex patterns of inheritance and epigenetic relationships drive the evolution of both a host and its symbionts (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2010; Herre et al., 1999; Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008). In other words, eukaryotic genomes evolve in concert with the vast number of microbial symbionts (e.g. microbiomes) harbored within lineages, though at varying scales of interrelatedness.

Before exploring the various degrees of intimacy between hologenome partnerships, we will address a few misconceptions about hologenomes themselves. Some have questioned the concept of the hologenome as a unit of selection because of the variation in both the nature of interactions and patterns of inheritance among its members (reviewed in Moran & Sloan, 2015). To view a hologenome as a single evolving unit would be inaccurate, as interactions between members are not necessarily mutualistic and hence, a hologenome may have negative or neutral consequences for one or more of the organisms involved (see ‘intimacy’ section below). Additionally, there is confusion between the concepts of the hologenome and the metagenome: the hologenome implies an interaction between a host and its symbionts whereas a metagenome can also describe a community within a non-living environment like soil (Bordenstein & Theis, 2015). Douglas and Werren (2016) go further to suggest that the focus should not be on the individual players; we should instead focus on host-microbe interactions through a wider ecological lens. We disagree with this view and instead believe that the concept of the hologenome expands our views on the genetic complexity of ‘individuals’. As the hologenome has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (e.g. Brucker & Bordenstein, 2013; Dale & Moran, 2006; Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008), we provide only a few examples here to explore how different hologenomes function along a continuum of intimacy as a way to exemplify the power of the concept.

Hologenomes: A Spectrum of Intimacy

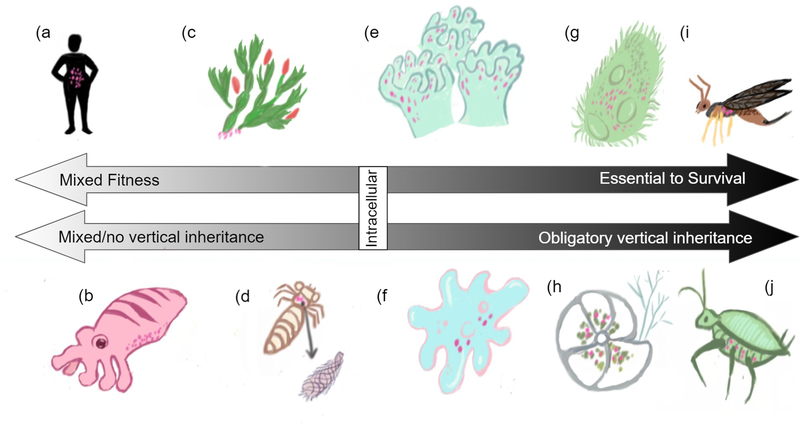

Hologenomes vary in intimacy and complexity, as the impact of symbiotic relationships on the survival of its members can be seen to vary across a sliding scale (Fig. 1). Here, we array interactions based on the degree of intimacy and the potential impact on fitness for the organisms involved. Hologenome symbioses range from the least intimate hologenomes, like the human microbiome (Kumar et al., 2014; Stilling, Bordenstein, Dinan, & Cryan, 2014), to moderately intimate hologenomes, including bacteria that provide heat resistance in plants (Gilbert et al., 2010; McLellan et al., 2007), to the most intimate hologenomes like those in aphids that have outsourced portions of the production of their protein building-blocks to their symbionts (Fig. 1; Wilson et al., 2010). Because the microbiome may be able to react more quickly to the environment than the host, microbiomes have the potential to impact host adaptation and evolution (Romano, 2017; Rosenberg & Zilber-Rosenberg, 2016; Stilling, Bordenstein, et al., 2014; Stilling, Dinan, & Cryan, 2014), though at varying degrees depending on the intimacy of the relationship such as the pattern of inheritance.

Figure 1:

Symbiotic relationships exist on a spectrum of intimacy and contribute to the concept of the hologenome. This spectrum is simply a tool to compare relative intimacies of symbiotic relationships. a) Human health is dependent on the microbiomes in the gut and other places on the body (Postler & Ghosh, 2017); b) Animals acquire fitness advantages from bacterial symbionts like Vibrio fischeri which cause Euprymna to glow (Gilbert et al., 2010); c) Symbiotic fungi provide a protein inhibitor that prevents Heat Shock Protein (HSP-90) in the Christmas Cactus Opuntia leptocaulis, allowing the plant to maintain its cells in various heat conditions (Gilbert et al., 2010; McLellan et al., 2007); d) Diversity of the communities of eukaryotic excavate symbionts in termite guts reflects the environment of their host communities (Duarte et al., 2018); e) Hermatypic coral are dependent on dinoflagellate Symbiodinium for 95% of their energy (Gilbert et al., 2010). f) Acanthamoebae are hosts to amoeba-resistant-bacteria like Legionella pneumophila which have evolved to resist digestion and become resistant to human macrophages (Greub & Raoult, 2004; Loret & Greub, 2010); g) Ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia hosts bacteria Caedibacter taeniospiralis in its cytoplasm which can kill non-host P. tetraurelia and protect current hosts from its killer mechanism (Grosser et al., 2018); h) Single-cellular foraminifera can ‘steal’ chloroplasts from the diatoms and algae they eat to use for photosynthesis -- a phenomenon known as kleptoplasty (Clark et al., 1990; Jauffrais et al., 2016); i) Parasitic wasp Asobara tabida needs Wolbachia bacteria to develop into adulthood and form its ovaries properly (Gilbert et al., 2010). j) Acrythosiphon pisum, otherwise known as pea aphids, need endosymbiotic bacterium Buchnera aphidicola to make essential amino acids it doesn’t get from its diet of sap (Wilson et al., 2010).

At the less intimate end of the spectrum, host genomes interact with and respond to relationships with other organisms in the holobiont and are not fully interdependent (Fig. 1 a & b). One example of this type of casual symbiosis includes digestion adaptations in the human gut microbiome (Fig. 1a, Postler & Ghosh, 2017). For example, gut symbionts (e.g. Bifidobacterium) fluctuate in response to changing levels of lactose and impact the expression of the human LCT gene, a gene that also contributes to lactose digestion (Blekhman et al., 2015). Further, expressions of immunity-related human genes like HLA-DRA and TLR1 have been respectively linked to the abundance of Selenomonas in the throat and Lautropia on the tongue (Blekhman et al., 2015). Another ‘relaxed’ hologenome relationship is the bioluminescent predator defense in squid. The squid allows colonies of a bioluminescent bacteria, Vibrio fischeri, to colonize and illuminate its light organ to ward off predators (Fig. 1b, Gilbert et al., 2010; McFall-Ngai, 2002). Genetic mechanisms in the squid’s immune defense system are hypothesized to regulate this bacterial defense mechanism, allowing the colonization of the light organ by helpful V. fischeri and preventing against pathogenic bacteria (McFall-Ngai, 2002).

As we move to the right on the spectrum of symbiotic intimacy (Fig. 1 c–i), products expressed by each member of the holobiont are essential to host and endosymbiont survival. For example, extracellular fungi express genes that inhibit a heat shock protein in the Christmas cactus Opuntia leptocaulis, preventing the cactus’s cells from deteriorating in hot environments (Fig. 1c, Gilbert et al., 2010; McLellan et al., 2007). Additionally, the survival of an amoebae host ensures the survival of its amoebae-resistant bacterial symbionts (Greub & Raoult, 2004; Loret & Greub, 2010). Pathogenic bacteria Legionella pneumophila has adapted its surface protein expression and other aspects of its genome to avoid digestion and instead to survive inside both free-living amoebae and human macrophage hosts (Fig 1f, Greub & Raoult, 2004).

In some cases, acquired symbiont genomes can increase host fitness by changing the methods of metabolic function and inflicting harm on non-hosts. Single-celled foraminifera switch from heterotrophy to phototrophy in nutrient-poor environments by stealing chloroplasts from their food (Fig. 1h, Clark, Jensen, & Stirts, 1990; Jauffrais et al., 2016; Pillet, de Vargas, & Pawlowski, 2011). Other holobionts make themselves more dangerous by inflicting harm on non-hosts. Caedibacter taeniospiralis, a bacterial symbiont of ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia, release a toxin that kills ciliates without the bacterium while genetically protecting their host from the toxin’s harm (Fig 1g, Grosser et al., 2018). Caedibacter taeniospiralis also up-regulates heat shock genes and metabolism enzymes for an additional fitness advantage to P. tetraurelia hosts (Grosser et al., 2018).

Some of the most intimate symbiotic relationships involve bidirectional interactions whereby host and symbiont genomes each provide different pieces of genetic pathways necessary for survival (Fig. 1 i & j). This is seen in sap-eating insects and their bacterial symbionts where gene pathways for metabolism, replication, transcription and translation are derived from products of endosymbiotic bacteria that are vertically inherited (Fig 1j, Bennett & Moran, 2013; Gilbert et al., 2010; Husnik et al., 2013; Provorov & Onishchuk, 2018). For example, Buchnera protein HisC can replace the function of the branched‐chain amino acid transaminase in the aphid, while phenylalanine 4‐monooxygenase and aspartate transaminase in the aphid may replace Tyrosine A and Tyrosine B enzymes absent in Buchnera (Wilson et al., 2010). The hologenome of the aphid and bacteria require each to contribute pieces to the other’s genome for the organisms to survive, and inheritance is vertical in this intimate relationship.

The genetic dependencies in hologenomes can be complicated by interactions among many players. The endosymbiotic Wolbachia bacteria in pea aphids gained the wCle gene from another endosymbiont, Cardinium or Rickettsia, through lateral gene transfer (Nikoh et al., 2014). This wCle gene synthesizes biotin for the host, which is now essential to the aphid’s survival and ability to reproduce (Nikoh et al., 2014). Some eukaryotic symbionts even live within other symbionts, like a Russian nesting doll. Neoparamoeba sp. parasitize salmon and other marine animals, and the amoeba themselves are host to Perkinsela sp., a kinetoplastid that has evolved in tandem with the amoeba, possibly due to metabolic relationships (Nowak & Archibald, 2018).

Some vertically-inherited symbiont phylogenies trace the evolution of their hosts from vertical inheritance for more than 100–200 million years (Dale & Moran, 2006; Douglas, 2011). This intimacy can also be observed in parasitic wasps (Asobara tabida). These wasps pass down their endosymbiotic bacteria through their eggs to the next generation because, without the bacteria, the wasp ovaries cannot develop properly (Fig. 1i, Gilbert et al., 2010). The wasps are trapped in an epigenetic hostage situation, ensuring the Wolbachia are passed onto future generations. Intriguingly, there are parallels in the mechanisms that the Wolbachia uses to destroy cells the wasp as bacterium Legionella pneumophila uses to burst its host cells. Wolbachia, the wasp’s bacterial symbiont, programs a similar apoptosis in the wasp’s ovaries, ensuring any non-hosts are unable to reproduce (Pannebakker, Loppin, Elemans, Humblot, & Vavre, 2007).

The epigenetic implications of the hologenome

The hologenome is, by definition, epigenetic; interactions within the hologenome can both lead to changes in gene expression without changes in DNA sequences (a textbook definition of epigenetics) and be interpreted in light of Denise Barlow’s definition of ‘weird and wonderful things’ (see above and McVittie, 2006). Regardless of the definition one adheres to, the impact of symbionts on host genomes is clearly outside of our traditional Mendelian view of transmission genetics.

The connection between the hologenome and epigenetics has been suggested by others either because of the influence of symbionts on host genetics (e.g. Douglas, 2011; Moran & Sloan, 2015; Zilber-Rosenberg & Rosenberg, 2008), or in light of the intergenerational impacts of symbionts on human phenotypes (e.g. Romano, 2017; Stilling, Dinan, et al., 2014). This interaction led Stilling, Dinan, et al. (2014) to introduce the term ‘holo-epigenome’ to explicitly acknowledge the epigenetic qualities of genomic interactions between hosts and symbionts.

Some canonical epigenetic functions have been observed in the human hologenome. For example, the diverse community of microbes within the human gut has been found to modulate host DNA methylation, changing patterns of gene expression (reviewed in Cureau, AlJahdali, Vo, & Carbonero, 2016). Further, in a preliminary study on the microbiota of pregnant women, significant differences in DNA methylation patterns were found based on the dominant bacteria that made up their microbiota (Kumar et al., 2014). As just one example, women whose predominant microbiotic fauna were in the phyla Firmicutes experienced differential methylation with regards to lipid metabolism and the inflammatory response, with downstream implications for obesity and cardiovascular disease (Kumar et al., 2014).

Symbiont-expressed microRNAs (miRNAs), have also been identified as a potential epigenetic mechanism between the microbiome and the host genomes (Liu, Du, Huang, Gao, & Yu, 2017; Williams, Stedtfeld, Tiedje, & Hashsham, 2017; Xue et al., 2011). Small non-coding RNAs of symbionts can regulate gene expression by repressing the translation of target mRNAs from the host genome (Cannell, Kong, & Bushell, 2008). For example, miRNA-10a levels, which coordinate the innate immune response, were shown to be downregulated by the presence of certain microbiota in mice (Xue et al., 2011). This is thought to promote homeostasis and prevent an immune response to commensal gut bacteria (Xue et al., 2011). Recent evidence also indicates that the miRNA-coordinated epigenetic communication between the host and microbiome is reciprocal, with host genetics able to shape the gut microbiome (Liu et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2017). For example, host extracellular miRNAs secreted by epithelial intestinal cells of mice may be regulating bacterial gene expression and ultimately bacterial growth within the intestine, (Liu et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2017), serving as a potential mechanism for molecular communication within the hologenome.

The concept of the hologenome is at odds with some aspects of Neo-Darwinism

The interwoven, epigenetic relationship between the genomes of host and symbionts complicates our current understanding of evolutionary theory. Today, when students open introductory biology textbooks, they will likely find the definition of evolution referred to as the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis, a combination of Darwin’s natural selection and Mendel’s particulate inheritance genetics. As a main proponent of this evolutionary lens, Mayr (1980) rejects the effect of any “soft inheritance”, defined as “the belief in a gradual change of the genetic material itself, either by use and disuse, or by some internal progressive tendencies, or through the direct effect of the environment” (Mayr, 1980). In contrast to this view, we argue that by excluding soft inheritance, the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis cannot account for the robust observations of epigenetics resulting from symbiotic relationships involving diverse lineages from across the Tree of Life (Table 1). Instead, we believe understanding evolution through the hologenome provides a more complete depiction of genome evolution, one that expands the traditional views on evolutionary theory.

Table 1:

Example of hologenomes exist among organisms in many eukaryotic clades, in diverse lineages of eukaryotes (See also figure 1).

| Host Clade | Host(s) | Example symbiont | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opisthokonta | Homo sapiens | Various including Bifidobacterium | (Blekhman et al., 2015; Romano, 2017; Stilling, Dinan, et al., 2014) |

| Euprymna (Bobtail squid) | Vibrio fischeri | (Gilbert et al., 2010) | |

| Asobara tabida (Wasp) | Wolbachia | (Gilbert et al., 2010), | |

| Acrythosiphon pisum (Pea aphid) | Buchnera aphidicola | (Wilson et al., 2010) | |

| Corals | Symbiodinium (Alveolata) | (Pillet et al., 2011; Rosenberg et al., 2007) | |

| Termites | Various Excavata | (Duarte, Nobre, Borges, & Nunes, 2018) | |

| Plantae | Opuntia leptocaulis (Christmas cactus) | Paraphaeosphaeria. Chaetomium, (Fungi) | (Gilbert et al., 2010; McLellan et al., 2007) |

| Legumes | Rhizobia (Bacteria in root nodules) | (Gage, 2004; Oldroyd, Murray, Poole, & Downie, 2011) | |

| Amoebozoa | Acanthamoeaba | Diverse bacteria | (Greub & Raoult, 2004; Loret & Greub, 2010) |

| Neoparamoeba sp | Perkinsela sp. (Excavata) | (Nowak and Archibald, 2018) | |

| Rhizaria | Foraminifera | Dinoflagellates, diatoms | (Jauffrais et al., 2016; Pillet et al., 2011) |

| Alveolata | Paramecium tetraurelia | Caedibacter taeniospiralis | (Grosser et al., 2018) |

Our discussion of how hologenomes epigenetically shape evolution is only one component of the broadening of the Modern Synthesis. New information from current explorations of non-genetic inheritance calls for a multidimensional reshaping of the Modern Synthesis. Because of our newfound appreciation of complex epigenetic mechanisms and their impact on evolution, we suggest use of a more inclusive and dynamic theory called the Extended Modern Synthesis – a conceptual expansion to the classical Modern Synthesis theories that includes an understanding of “soft inheritance” (Danchin et al., 2011; Pigliucci & Finkelman, 2014). As new discoveries broaden our understanding of evolutionary theory (Mendelian inheritance, natural selection), Novick and Doolittle (2019) implore us to expand our evolutionary theory ‘toolbox’ to account for the complexity of hologenomes and other epigenetic phenomena. Darwin’s original theory was built on understanding the natural world he observed. By excluding certain truths, like those we observe from symbiosis, we stray from Darwin’s original aim of an evolutionary model that captures the whole of nature (Raoult & Koonin, 2012). We need to remain open-minded and allow new evidence to reshape our theories. As Bonner (2019) points out, evolution has been evolving since the beginning of time. If our goal is to truly understand it, we must continue evolving our understanding of evolution as well.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to members of the Fall 2018 Epigenetics class at Smith College for conversation and inspiration. L.A.K. is supported by NSF grants DEB 1651908 and DEB-1441511.

REFERENCES

- Bennett GM, & Moran NA (2013). Small, smaller, smallest: the origins and evolution of ancient dual symbioses in a Phloem-feeding insect. Genome Biol Evol, 5(9), 1675–1688. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekhman R, Goodrich JK, Huang K, Sun Q, Bukowski R, Bell JT, … Clark AG (2015). Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol, 16, 191. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JT (2019). The evolution of evolution. Journal of Experimental Zoology B: Mol Dev Evol. [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein SR, & Theis KR (2015). Host Biology in Light of the Microbiome: Ten Principles of Holobionts and Hologenomes. PLoS Biol, 13(8), e1002226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brucker RM, & Bordenstein SR (2013). The capacious hologenome. Zoology (Jena), 116(5), 260–261. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell IG, Kong YW, & Bushell M (2008). How do microRNAs regulate gene expression? Biochem Soc Trans, 36(Pt 6), 1224–1231. doi: 10.1042/BST0361224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KB, Jensen KR, & Stirts HM (1990). Survey for functional kleptoplasty among west Atlantic Ascoglossa (= Sacoglossa) (Mollusca, Opisthobranchia). Veliger, 33(4), 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Cureau N, AlJahdali N, Vo N, & Carbonero F (2016). Epigenetic mechanisms in microbial members of the human microbiota: current knowledge and perspectives. Epigenomics, 8(9), 1259–1273. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale C, & Moran NA (2006). Molecular interactions between bacterial symbionts and their hosts. Cell, 126(3), 453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danchin É, Charmantier A, Champagne FA, Mesoudi A, Pujol B, & Blanchet S (2011). Beyond DNA: integrating inclusive inheritance into an extended theory of evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics, 12, 475. doi: 10.1038/nrg3028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE (2011). Lessons from studying insect symbioses. Cell Host Microbe, 10(4), 359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE, & Werren JH (2016). Holes in the Hologenome: Why Host-Microbe Symbioses Are Not Holobionts. Mbio, 7(2), e02099. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02099-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte S, Nobre T, Borges PAV, & Nunes L (2018). Symbiotic flagellate protists as cryptic drivers of adaptation and invasiveness of the subterranean termite Reticulitermes grassei Clement. Ecology and Evolution, 8(11), 5242–5253. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage DJ (2004). Infection and invasion of roots by symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing rhizobia during nodulation of temperate legumes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 68(2), 280–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.280-300.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SF (2019). Holobiont - this volume. J Exp Zool B. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SF, McDonald E, Boyle N, Buttino N, Gyi L, Mai M, … Robinson J (2010). Symbiosis as a source of selectable epigenetic variation: taking the heat for the big guy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 365(1540), 671–678. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greub G, & Raoult D (2004). Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 17(2), 413–+. doi: 10.1128/Cmr.17.2.413-433.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser K, Ramasamy P, Amirabad AD, Schulz MH, Gasparoni G, Simon M, & Schrallhammer M (2018). More than the “Killer Trait”: Infection with the bacterial endosymbiont Caedibacter taeniospiralis causes transcriptomic modulation in Paramecium host. Genome Biol Evol, 10(2), 646–656. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herre EA, Knowlton N, Mueller UG, & Rehner SA (1999). The evolution of mutualisms: exploring the paths between conflict and cooperation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 14(2), 49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01529-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnik F, Nikoh N, Koga R, Ross L, Duncan RP, Fujie M, … McCutcheon JP (2013). Horizontal gene transfer from diverse bacteria to an insect genome enables a tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. Cell, 153(7), 1567–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauffrais T, Jesus B, Metzger E, Mouget JL, Jorissen F, & Geslin E (2016). Effect of light on photosynthetic efficiency of sequestered chloroplasts in intertidal benthic foraminifera (Haynesina germanica and Ammonia tepida). Biogeosciences, 13(9), 2715–2726. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-2715-2016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Lund R, Laiho A, Lundelin K, Ley RE, Isolauri E, & Salminen S (2014). Gut microbiota as an epigenetic regulator: pilot study based on whole-genome methylation analysis. Mbio, 5(6). doi: 10.1128/mBio.02113-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PL, Du L, Huang Y, Gao SM, & Yu M (2017). Origin and diversification of leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase (LRR-RLK) genes in plants. Bmc Evolutionary Biology, 17. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0891-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loret JF, & Greub G (2010). Free-living amoebae: Biological by-passes in water treatment. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 213(3), 167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, & Kowallik K (1999). Annotated English translation of Mereschkowsky’s 1905 paper ‘Über Natur und Ursprung der Chromatophoren imPflanzenreiche’. European Journal of Phycology, 34(3), 287–295. doi: 10.1080/09670269910001736342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr E (1980). Prologue: Some Thoughts on the History of the Evolutionary Synthesis. In Mayr E & Provine W (Eds.), The Evolutionary Synthesis (pp. 1–48). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McFall-Ngai MJ (2002). Unseen forces: The influence of bacteria on animal development. Developmental Biology, 242(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan CA, Turbyville TJ, Wijeratne EMK, Kerschen A, Vierling E, Queitsch C, … Gunatilaka AAL (2007). A rhizosphere fungus enhances Arabidopsis thermotolerance through production of an HSP90 inhibitor. Plant Physiology, 145(1), 174–182. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVittie B (2006). What is Epigenetics. Retrieved from http://epigenome.eu/en/1,1,0

- Mereschkowsky K (1910). Theorie der zwei Plasmaarten als Grundlage der Symbiogenesis, einer neuen Lehre von der Ent‐stehung der Organismen. Biol Centralbl, 30, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Moran NA, & Sloan DB (2015). The hologenome concept: helpful or hollow? PLoS Biol, 13(12), e1002311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Moriyama M, Oshima K, Hattori M, & Fukatsu T (2014). Evolutionary origin of insect-Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(28), 10257–10262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409284111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick A, & Doolittle WF (2019). How microbes “jeopardize” the modern synthesis. PLoS Genet, 15(5), e1008166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack ECM, & Melkonian M (2010). Endosymbiotic associations within protists. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 365(1541), 699–712. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak BF, & Archibald JM (2018). Opportunistic but Lethal: The Mystery of Paramoebae. Trends Parasitol, 34(5), 404–419. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE, Murray JD, Poole PS, & Downie JA (2011). The rules of engagement in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis. Annu Rev Genet, 45, 119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannebakker BA, Loppin B, Elemans CP, Humblot L, & Vavre F (2007). Parasitic inhibition of cell death facilitates symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(1), 213–215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607845104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M, & Finkelman L (2014). The extended (evolutionary) synthesis debate: where science meets philosophy. BioScience, 64(6), 511–516. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillet L, de Vargas C, & Pawlowski J (2011). Molecular identification of sequestered diatom chloroplasts and kleptoplastidy in foraminifera. Protist, 162(3), 394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postler TS, & Ghosh S (2017). Understanding the Holobiont: How Microbial Metabolites Affect Human Health and Shape the Immune System. Cell Metabolism, 26(1), 110–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provorov NA, & Onishchuk OP (2018). Microbial Symbionts of Insects: Genetic Organization, Adaptive Role, and Evolution. Microbiology, 87(2), 151–163. doi: 10.1134/s002626171802011x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D, & Koonin EV (2012). Microbial genomics challenge Darwin. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2, 127. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M (2017). Gut microbiota as a trigger of accelerated directional adaptive evolution: acquisition of herbivory in the context of extracellular vesicles, microRNAs and inter-Kingdom crosstalk. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, & Zilber-Rosenberg I (2007). The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol, 5(5), 355–362. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E, & Zilber-Rosenberg I (2016). Microbes drive evolution of animals and plants: the hologenome concept. Mbio, 7(2), e01395. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01395-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilling RM, Bordenstein SR, Dinan TG, & Cryan JF (2014). Friends with social benefits: host-microbe interactions as a driver of brain evolution and development? Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilling RM, Dinan TG, & Cryan JF (2014). Microbial genes, brain & behaviour - epigenetic regulation of the gut-brain axis. Genes Brain Behav, 13(1), 69–86. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MR, Stedtfeld RD, Tiedje JM, & Hashsham SA (2017). MicroRNAs-based inter-domain communication between the host and members of the gut microbiome. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ACC, Ashton PD, Calevro F, Charles H, Colella S, Febvay G, … Douglas AE (2010). Genomic insight into the amino acid relations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, with its symbiotic bacterium Buchnera aphidicola. Insect Molecular Biology, 19, 249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X, Feng T, Yao S, Wolf KJ, Liu CG, Liu X, … Cong Y (2011). Microbiota downregulates dendritic cell expression of miR-10a, which targets IL-12/IL-23p40. J Immunol, 187(11), 5879–5886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilber-Rosenberg I, & Rosenberg E (2008). Role of microorganisms in the evolution of animals and plants: the hologenome theory of evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 32(5), 723–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]