Abstract

Hypogonadism, alopecia, diabetes mellitus, mental retardation, and extrapyramidal syndrome (also known as Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome) is a rare autosomal recessive neuroendocrine and ectodermal disorder. The syndrome was first described by Woodhouse and Sakati in 1983, and 47 patients from 23 families have been reported so far. We report on an additional seven patients (four males and three females) from two highly consanguineous Arab families from Qatar, presenting with a milder phenotype of Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome. These patients show the spectrum of clinical features previously found in Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome, but lack evidence of diabetes mellitus and extrapyramidal symptoms. These two new families further illustrate the natural course and the interfamilial phenotypic variability of Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome that may lead to challenges in making the diagnosis. In addition, our study suggests that Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome may not be as infrequent in the Arab world as previously thought.

Keywords: Arab, Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome, hypogonadism, alopecia, deafness, diabetes mellitus, learning disabilities, Qatar, autosomal recessive

INTRODUCTION

Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome (WSS) (OMIM# 241080) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder, with about 47 patients reported in the literature [Woodhouse and Sakati, 1983; Devriendt et al., 1996; Gul et al., 2000; Al-Semari and Bohlega, 2007; Medica et al., 2007; Koshy et al., 2008; Schneider and Bhatia, 2008; Alazami et al., 2010; Rachmiel et al., 2011]. The cardinal features include alopecia, hypogonadism, diabetes mellitus, mental retardation, sensorineural hearing loss, and extrapyramidal signs. Additional manifestations such as seizures, white matter abnormalities of the brain, polyneuropathy, thyroid dysfunction, keratoconus, and syndactyly of the hands or feet have been described in some cases. Recently, it has been shown that mutations in the C2orf37 gene cause WSS [Alazami et al., 2008]. Herein we report seven patients from two families belonging to a highly consanguineous Bedouin Qatari tribe that have a mild phenotype of WSS and mutations in the C2orf37 gene.

CLINICAL REPORTS

Seven patients with WSS are described from two families of a consanguineous inbred Bedouin tribe.

Family 1

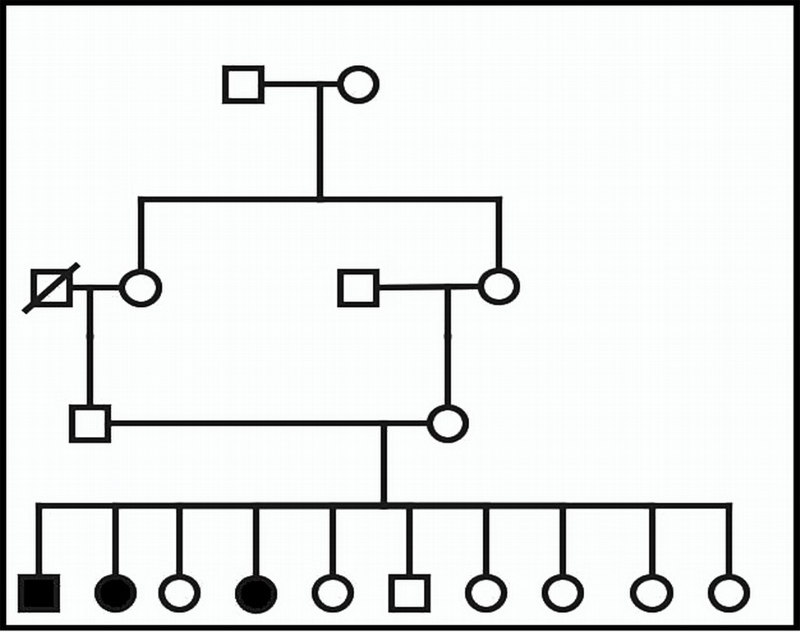

The parents are healthy first cousins and have one affected son, two affected daughters, and seven phenotypically normal children. Figure 1 illustrates the family pedigree.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of Family 1 (Patients 1–3).

Patient 1 is a 23-year-old male (Fig 3) who had an unremarkable perinatal and developmental history. He presented at the age of 16 years because of delayed puberty. Endocrine evaluation revealed that he had a low testosterone level of 1.48 nmol/L (reference range is 10.4–35) and so he was treated with testosterone injections every three months with no significant improvement. At the age of 20 years, he was found to have myopia and moderate sensorineural hearing loss. The family reported partial frontal alopecia since early childhood. Patient 1 is not attending school due to learning disabilities and poor school performance. He has an IQ of 75, suggesting borderline intellectual disability. On examination, his weight and head circumference were at the 5th centile, and his height was at the 50th centile. He had a long face, frontal alopecia, and sparse eyebrows. He had no facial, axillary or pubic hair and his Tanner stage was two. Patient 1 exhibited no involuntary movements. His bone age was delayed by 3 years, and there was no scoliosis. Hormonal studies revealed a low IGF-1 level of 117ng/ml (reference range: 187.9–400) and an HbA1C of 5.9 (reference range: 4.8–6). Other tests that showed results within normal limits included liver and thyroid function tests, lipid profile, testosterone, prolactin and growth hormone levels, glucose tolerance test and insulin levels. Scrotum ultrasound showed normal sized testes (right testis: 3.9 × 1.2 cm, left testis: 3.3 × 1.4 cm) and a mild left-sided varicocele. Finally, a brain MRI, including the pituitary gland, was also unremarkable.

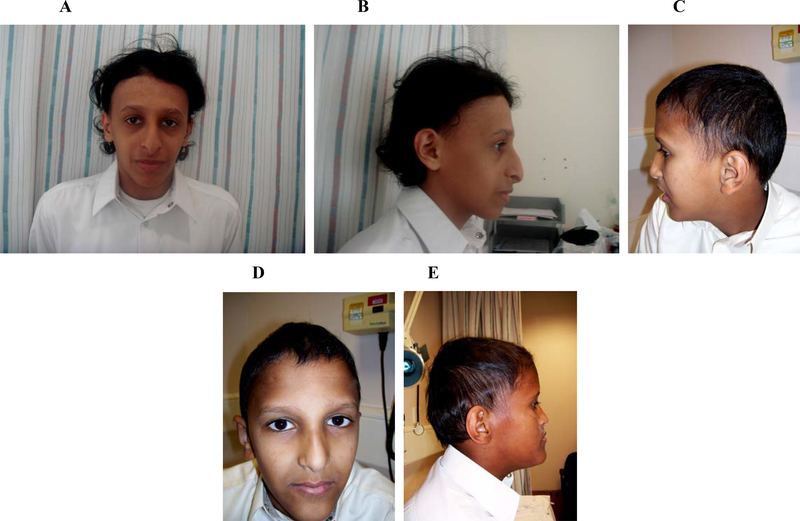

Figure 3.

Facial features and alopecia in three of our patients; A, B: Patient 1, C, D: Patient 5; E: Patient 6

Patient 2 is a 20-year-old female who presented at the age of 16 years with delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea and was reported to have had frontal alopecia since early childhood. Both antenatal and perinatal histories were normal, and her early development was said to be unremarkable. At the time of presentation, she was seen by an endocrinologist who started her on hormone replacement therapy, after which her menses began but no significant improvement in secondary sexual characteristics was noted. At 19 years of age, she was seen by an ophthalmologist for poor vision and was found to have bilateral keratoconus. A hearing assessment revealed bilateral mild sensorineural deafness. She had no involuntary movements. Currently, Patient 2 is exhibiting some learning disabilities and poor school performance. She has borderline intellectual disability with an IQ of 78. On physical examination, her weight and height were at the 5th centile and she was noted to have a long face with frontal alopecia as well as long fingers. Tanner stage was 2; she had minimal breast budding and minimal axillary and pubic hair. Bone age was delayed by 3 years and there was no scoliosis. Hormone studies showed normal growth hormone, prolactin, cortisol, LH, FSH, TSH and T4 levels. Estradiol level was found at <37 pmol/L (reference range: Follicular: 88–418, Mid Cycle: 228–1960, Luteal: 294–1102), which has since normalized as she is on hormonal therapy. Her HbA1C was normal at 5.9 (reference range: 4.8–6), and IGF-1 was low at 39.5 ng/ml (reference range: 187.9–400). Patient 2 had a normal glucose tolerance test. A pelvic MRI showed a hypoplastic uterus and non-visualized ovaries. Her brain MRI was unremarkable.

Patient 3 is a 17-year-old female who presented with primary amenorrhea and delayed puberty. She was also reported to have had alopecia and thin hair since early childhood. Her neonatal and developmental histories were reported to have been unremarkable. Patient 3 is myopic and a hearing assessment revealed mild sensorineural hearing loss. She had no abnormal movements. Currently, she has learning disabilities with fair school performance; her IQ is 71, suggesting borderline intellectual disability. On physical examination, her weight and height were at the 25th centile and her head circumference was at the 5th centile. Tanner stage was 2; she had minimal breast budding and pubic hair. Patient 3 was noted to have a long face, frontal alopecia with sparse scalp hair and eyebrows, and partial syndactyly of the second and third fingers. She had a large hyperpigmented macule extending from the left mandibular area to the left pectoral area that was well circumscribed with irregular borders. As with the other patients, bone age was delayed by 3 years and no scoliosis was seen. Hormone studies showed normal growth hormone, prolactin, cortisol, LH, FSH, TSH and T4 levels; however, estradiol was low at <37 pmol/l (reference range: Follicular: 88–418, Mid Cycle: 228–1960, Luteal: 294–1102). Her HbA1C level was 5.9 (reference range: 4.8–6) and IGF-1 was low at 32 (reference range: 187.9–400). Patient 3’s pelvic MRI also revealed a hypoplastic uterus and non-visualized ovaries.

Family 2

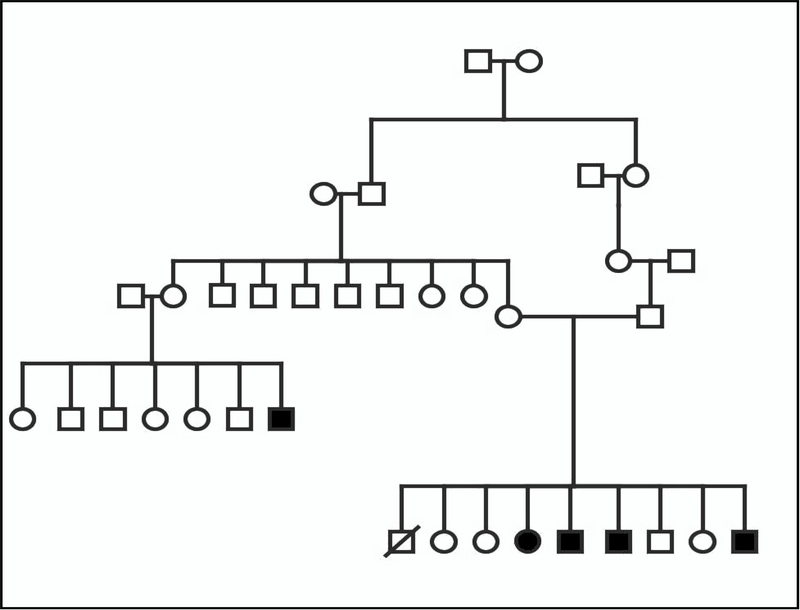

The parents are healthy second cousins who have one affected daughter, three affected sons, four unaffected children, and a history of a first trimester miscarriage. Figure 2 illustrates the family pedigree.

Figure 2.

Pedigree of Family 2 (Patients 4–7).

Patient 4 is a 19-year-old female who was born after an uneventful pregnancy and delivery. She presented at 14 years of age with primary amenorrhea and delayed puberty. She had partial alopecia and friable hair starting early in life. There was no history of abnormal movements. Her motor and cognitive development was appropriate, but she currently has learning disabilities, IQ: 71, suggestive of borderline intellectual disability. On examination, her weight and height were at the 25th centile her head circumference was at the 5th centile. Tanner stage was 2; she had minimal breast buds and no axillary or pubic hair. She was noted to have a long face, alopecia of the frontal and temporal regions with friable hair, and sparse eyebrows. There was no scoliosis. Chest and abdominal examination, as well as neurological examinations were normal. Hearing assessment showed mild sensorineural deafness, and an ophthalmological evaluation was normal. Endocrinology workup revealed a low estradiol level of <37 pmol/l, (reference range: Follicular: 88–418, Mid Cycle: 228–1960, Luteal: 294–1102) normal LH and FSH, and normal growth hormone and prolactin levels. She had a very low IGF-1 level of 15 (reference range: 187.9–400), and an elevated HbA1C of 6.9 (reference range: 4.8–6). Transperineal ultrasound showed a small uterus and tiny ovaries, and, although further evaluation by MRI was recommended, the patient declined follow-up imaging.

Patient 5 is an 18-year-old male who presented at 15 years of age with delayed puberty, hyperactivity and learning disability, IQ: 68, suggestive of mild intellectual disability. (Fig 3). Antenatal and perinatal histories were unremarkable. He had normal early gross motor development and no history of abnormal movements. On examination, his height and weight were below the 5th centile. He was noted to have a long face with deep-set eyes, partial alopecia in the frontal and temporal regions, and sparse eyebrows and eyelashes. There was no facial, axillary or pubic hair. Both testes were small and Tanner stage was 1. Patient 5 had normal hearing, vision, cardiac, abdominal, neurological and skeletal examinations. His hormone analysis revealed low normal LH and FSH levels and a low testosterone level of 2.03 nmol/l (reference range: 3.47–41.64). The IGF-1 level was also low at 67 ng/ml (reference range: 187.9–400).

Patient 6 is a 15-year-old male who was evaluated at 12 years of age for hyperactivity and poor school performance, IQ: 60, suggestive of mild intellectual disability (Fig 3). He had a normal neonatal period, unremarkable early development and no history of abnormal movements. On examination, his height and weight were at the 25th centile. He was noted to have a long face with deep-set eyes, partial alopecia in the temporal and frontal regions, and sparse eyebrows and eyelashes. There was no axillary or pubic hair, both testes were small and Tanner stage was 1. Patient 6 also had normal hearing, vision, cardiac, abdominal, neurological and skeletal examinations. His hormone analysis revealed low LH and FSH levels and a low testosterone level of 1.85 nmol/l (reference range: 3.47–41.64). The IGF-1 level was also low at 64 ng/ml (reference range: 187.9–400).Brain MRI showed diffusely increased periventricular white matter and centrum semiovale signal intensities on T2 images, suggestive of white matter hypomyelination, but was otherwise unremarkable.

Patient 7 is an 8-year-old male who was evaluated at 6 years of age for hyperactivity and poor school performance, IQ: 66, suggestive of mild intellectual disability. He had a normal neonatal period, unremarkable early development and no history of abnormal movements. The family reported that he has learning disabilities. On examination, his height and weight were at the 5th centile. He was noted to have a long face with deep-set eyes, partial alopecia in the temporal region, friable hair and sparse eyebrows. He had small testes and the Tanner stage was 1. The remainder of his physical examination was unremarkable, including his hearing and vision. Patient 7’s hormonal studies showed low LH, testosterone and IGF-1.

GENETIC STUDIES

The four affected patients from Family 2 were subjected to genome-wide SNP analysis by Illumina 550K microarray and areas of homozygosity shared by all four were tabulated. The largest area of shared homozygosity was on chromosome 2, measured 6.9cM (6.0Mb), and contained the C2orf37gene known to be associated with Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome. Given the phenotypic similarity of the affected individuals in this family to Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome, C2orf37 was sequenced. Primer3 software was used to design sequencing primers. A homozygous one base pair deletion in exon 4 of C2orf37 (c.436delC) was identified in all affected four individuals of Family 2. Subsequently, the patients from Family 1 were also identified to have the same C2orf37 mutation.

Research protocols were approved by the participating institutions, and all the research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible national and institutional committees on human subject research.

DISCUSSION

We report on seven patients from two families with Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome (WSS) and a homozygous mutation in the C2orf37 gene. The constellation of clinical features described in these patients is relatively unique to WSS. These include delayed puberty, primary amenorrhea, frontal alopecia and learning disabilities. The patients in the Family 1 also had sensorineural hearing loss and poor vision. Certain manifestations of WSS do not appear until later ages, and thus making the diagnosis in children particularly challenging. For example, none of the patients presented herein had evidence of diabetes mellitus or extrapyramidal symptoms. Though the natural history of WSS has not been completely elucidated, published cases suggest that diabetes and extrapyramidal symptoms usually do not appear until late teens or early adulthood [Al-Semari and Bohlega, 2007; Alazami et al., 2010]. The combination of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and partial alopecia should raise suspicion for WSS, but hypogonadism is usually not apparent until puberty and alopecia can be mild and become more noticeable with age [Woodhouse and Sakati, 1983]. These factors made arriving at the diagnosis of WSS initially difficult when these patients first presented.

The mutation identified in our patients, a base pair deletion in exon 4 of C2orf37, has been reported in a total of seven families from Saudi Arabia [Alazami et al., 2008], thus likely representing a founder mutation in this region. Al-Semari and Bohlega presented 26 patients with WSS from 12 families in Saudi Arabia [Al-Semari and Bohlega, 2007]. Although these families seem to share the same founder mutation and comprise a fairly genetically homogeneous population, our patients show that variability in clinical presentation exists. For example, diabetes mellitus is noted as early as 17 years of age, but in some patients may not be present after 30 years of age. Dystonia is also reported as early as 17 years, but a 43-year-old patient is reported to have no dystonia. LH and FSH are often normal, but both high and low levels have been reported. Such variable expression might suggest the presence of disease modifying factors.

Founder effect is a loss of genetic diversity in an isolated population wherein a particular mutation is thought to be the sole cause of a certain trait or disease [Aldahmesh et al, 2009]. The high incidence of consanguineous unions in this region increases allelic heterogeneity for such a rare disorder. This, according Aldahmesh et al [2009] goes counter to the founder effect, and consequently, explains the relatively low genetic variation. Additional mutations in C2orf37 have been reported from other ethnicities [Alazami et al., 2009; Alazami et al., 2010]. This suggests that mutations in C2orf37 are responsible for WSS in other ethnicities.

In conclusion, it is important to consider WSS in patients presenting with hypogonadism, frontal alopecia and learning disabilities, even in the absence of diabetes and extrapyramidal manifestations. In WSS, cognitive dysfunction is usually present early in life, but other manifestations such as diabetes and extrapyramidal symptoms might not appear until adolescence or early adulthood, and so making the diagnosis early can be difficult. Mutation analysis of C2orf37 can be used to confirm the diagnosis of WSS once suspicion is raised. Endogamy and high consanguinity contribute to the clustering of such rare autosomal recessive syndromes in the Arab world and, based on this and previous reports; it appears that WSS is probably not as rare among the Arabs as previously thought.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features for WSS of in our patients.

| Ref | Age/ Sex | Alopecia | Hypogon-adism | Mental Delay | Diabetes | Deaf | CNS | Pelvic Examination | MRI head | Ophthalmology | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 23/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | ND | N | Myopia | IQ: 75 |

| Patient 2 | 20/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | hypoplastic uterus and non-visualized ovaries. | N | Keratoconus | IQ: 78 |

| Patient 3 | 17/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | hypoplastic uterus and non-visualized ovaries. | ND | Myopia | IQ: 71 |

| Family 2 | |||||||||||

| Patient 4 | 19/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | a small uterus and tiny ovaries | ND | N | IQ: 71 |

| Patient 5 | 17/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | ND | N | IQ: 68 | |

| Patient 6 | 15/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | diffusely increased periventricular white matter and centrum semiovale signal intensities on T2 images, suggestive of white matter hypomyelination. | N | IQ: 60 | |

| Patient 7 | 8/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | ND | N | IQ: 66 |

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical features for WSS in previously reported cases

| Ref | Age/ Sex | Alopecia | Hypogon-adism | Mental Delay | Diabetes | Deaf | CNS | Pelvic Examination | MRI head | Ophthalmology | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranddall et al[1973] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 21/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | IQ:87 | ||||

| Patient 2 | 19/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | IQ:97 | ||||

| Patient 3 | 18/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | IQ:87 | ||||

| Al Awadi et al [1985] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 18/F | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | Ovaries, fallopian tubes absent | ||||

| Patient 2 | 16/F | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | Streak ovaries, hypoplastic tubes | ||||

| Patient 3 | 22?M | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | Azospermia, no germinal elements | ||||

| Devriendt et al.[1996] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 12/M | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | No | Dysarthria, Dystonia | White matter disease | |||

| Patient 2 | 14/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||

| Gul et al [2000] | NR | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 32/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Salti and Salem [1979] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 16/M | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Patient 2 | 20/M | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Patient 3 | 21/M | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Oerter et al. [1992] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 24/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Infantile uterus | ||||

| Patient 2 | 20/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Infantile uterus | ||||

| Patient 3 | 13/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Patient 1 | 18/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| Woodhouse and Sakati [1983] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 22/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Patient 2 | 17/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Pre-diabetic | ||||||

| Patient 3 | 21/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | hypoplastic uterus, Streak ovaries | |||||

| Patient 4 | 16/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Patient 5 | 40/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Patient 6 | 47/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Susanne et al [2008] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 36/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dystonia | White matter disease | |||

| Patient 2 | 22/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dystonia-seizure | Keratoconus | |||

| Alazami et al [2010] | |||||||||||

| Patient 1 | 36/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Dystonia | White matter changes | |||

| Patient 2 | 41/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Patient 3 | 15/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| Patient 4 | 12/F | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |||||

| Patient 5 | 12/F | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |||||

| Patient 6 | 58/M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dystonia | ||||

| Patient 7 | 47/F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dystonia |

Table 3.

Laboratory findings in our patients.

| Ref | FSH | LH | GH | IGF-1 | T4 | PRL | Cortisone | Testosterone | Estrogen | Insulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | N | N | Low | N | N | N | N (after treatment) | N | |

| Patient 2 | N | N | N | Low | N | N | N | Low | N | |

| Patient 3 | N | N | N | Low | N | N | N | Low | N | |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||

| Patient 4 | N | N | N | Low | N | N | N | Low | N | |

| Patient 5 | low N | low N | N | Low | N | N | N | low | N | |

| Patient 6 | Low | Low | N | Low | N | N | N | low | N | |

| Patient 7 | Low | Low | N | Low | N | N | N | low | N |

Table 4.

Laboratory findings in previously reported cases of WSS.

| Ref | FSH | LH | GH | IGF-1 | T4 | PRL | Cortisone | Testosterone | Estrogen | Insulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranddall et al[1973] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | Low | Low | NR | NR | NR | very low | NR | ||

| Patient 2 | N | Low | Low | NR | NR | NR | low | NR | ||

| Patient 3 | N | N | N | NR | NR | NR | N | NR | ||

| Al Awadi et al [1985] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | High | High | NR | NR | N | NR | N | NR | NR | |

| Patient 2 | High | High | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Patient 3 | High | N | ||||||||

| Devriendt et al.[1996] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | N | NR | NR | NR | Low normal | Low | |||

| Patient 2 | High | High | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Gul et al [2000] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | Low | NR | NR | |

| Salti and Salem [1979] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | Low | Low | N | NR | NR | N | very low | NR | ||

| Patient 2 | Low | Low | N | NR | NR | N | very low | NR | ||

| Patient 3 | High | Low | N | NR | NR | N | very low | NR | ||

| Oerter et al. [1992] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | N | Low | NR | N | N | NR | |||

| Patient 2 | N | N | Low | NR | N | N | NR | |||

| Patient 3 | N | N | Low | NR | N | N | NR | |||

| Patient 1 | N | N | Low | NR | N | N | NR | |||

| Woodhouse and Sakati [1983] | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | N | N | NR | NR | NR | Slightly high | Low | N | ||

| Patient 2 | N | N | NR | NR | NR | N | very low | |||

| Patient 3 | High | High | NR | NR | NR | N | very low | |||

| Patient 4 | High | High | NR | NR | NR | N | very low | |||

| Patient 5 | N | N | NR | NR | NR | N | N |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all patients and their families for their excellent collaboration. Special thanks go to Dr. Ganeshwaran H. Mochida, Dr. Wen-Hann Tan, Jennifer N. Partlow and Basel A. Teebi for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Al-Semari A, Bohlega S. 2007. Autosomal-recessive syndrome with alopecia, hypogonadism, progressive extra-pyramidal disorder, white matter disease, sensory neural deafness, diabetes mellitus, and low IGF1. Am J Med Genet Part A 143: 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazami AM, Al-Saif A, Al-Semari A, Bohlega S, Zlitni S, Alzahrani F, Bavi P, Kaya N, Colak D, Khalak H, Baltus A, Peterlin B, Danda S, Bhatia KP, Schneider SA, Sakati N, Walsh CA, Al-Mohanna F, Meyer B, Alkuraya FS. 2008. Mutations in C2orf37, encoding a nucleolar protein, cause hypogonadism, alopecia, diabetes mellitus, mental retardation, and extrapyramidal syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 83: 684–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazami AM, Schneider SA, Bonneau D, Pasquier L, Carecchio M, Kojovic M, Steindl K, de Kerdanet M, Nezarati MM, Bhatia KP, Degos B, Goh E, Alkuraya FS. 2010. C2orf37 mutational spectrum in Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome patients. Clin. Genet.78: 585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldahmesh MA, Abu-Safieh L, Khan AO, Al-Hassnan ZN, Shaheen R, Rajab M, Monies D, Meyer BF, Alkuraya FS. 2009. Allelic heterogeneity in inbred populations: The Saudi experience with Alström syndrome as an illustrative example. Am J Med Genet Part A, 149: 662–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriendt K, Legius E, Fryns JP. 1996. Progressive extrapyramidal disorder with primary hypogonadism and alopecia in sibs: a new syndrome? Am J Med Genet 62: 54–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gül D, Ozata M, Mergen H, Odabaşi Z, Mergen M. 2000. Woodhouse and Sakati syndrome (OMIM 241080): report of a new patient. Clin Dysmorph 9: 123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshy G, Danda S, Thomas N, Mathews V, Viswanathan V. 2008. Three siblings with Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome in an Indian family. Clin Dysmorph 17: 57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medica I, Sepcić J, Peterlin B. 2007. Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome: case report and symptoms review. Genet Counsel 18: 227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachmiel M, Bistritzer T, Hershkoviz E, Khahil A, Epstein O, Parvari R. 2011. Woodhouse-Sakati Syndrome in an Israeli-Arab Family Presenting with Youth-Onset Diabetes Mellitus and Delayed Puberty. Horm Res Paediatr. February 8 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SA, Bhatia KP. 2008. Dystonia in the Woodhouse Sakati syndrome: a new family and literature review. Mov Disord 23: 592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse NJ, Sakati NA. 1983. A syndrome of hypogonadism, alopecia, diabetes mellitus, mental retardation, deafness, and ECG abnormalities. J Med Genet 20: 216–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]