Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The objective of the present study was to systematically review the current research knowledge on hospital preparedness tools used in biological events and factors affecting hospital preparedness in such incidents in using a scoping review methodology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The review process was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guideline. Online databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) were used to identify papers published that evaluated instruments or tools for hospital preparedness in biological disasters (such as influenza, Ebola, and bioterrorism events). The search, article selection, and data extraction were carried out by two researchers independently.

RESULTS:

A total of 3440 articles were screened, with 20 articles identified for final analysis. The majority of research studies identified were conducted in the United States (45%) and were focused on CBRN incident (20%), Ebola, infectious disease and bioterrorism events (15%), mass casualty incidents and influenza pandemic (10%), public health emergency, SARS, and biological events (5%). Factors that were identified in the study to hospitals preparedness in biological events classified in seven areas including planning, surge capacity, communication, training and education, medical management, surveillance and standard operation process.

CONCLUSIONS:

Published evidences of hospital preparedness on biological events as well as the overall quality of the psychometric properties of most studies were limited. The results of the current scoping review could be used as a basis for designing and developing a standard assessment tool for hospital preparedness in biological events, and it can also be used as a clear vision for the healthcare managers and policymakers in their future plans to confront the challenges identified by healthcare institutes in biologic events.

Keywords: Biological event, biological threat, bioterrorism events, disaster, hospital preparedness, tools

Introduction

In today's societies, threats caused by chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear incidents both accidentally and deliberately have become a major concern[1] It is essential to acquire the knowledge on how to respond and manage such incidents and their complications to maintain societies and provide stability.[2] A quick and consistent response to such incidents can play an important role in reducing the harmful effects of such events on public health as well as its psychological consequences.[1] The prevalence of various diseases caused by biological incidents in the past decades, such as acute respiratory syndrome,[3] influenza[4,5] Ebola,[6,7] emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases,[8,9] bioterrorism events,[10,11] and public health emergencies.[12] In addition to the threat of high mortality, can cripple health and medical systems and significantly impair social and economic performance in society.[13] Planning and preparedness for biological disasters is essential to ensure functional continuity of the health system and other organizations involved with such incidents and can greatly reduce the economic and social costs associated with it.[14] The health sector has a special status among all the bodies involved in disaster management because the first demand and the most important concern of people is health.[2] Meanwhile, hospitals are the most important sections for the treatment, monitoring, and supervision of biological disasters, and their preparedness is an essential component for early diagnosis and management of these incidents,[12,15] and they also require special preparation, resource availability, and special skills and ability to efficiently respond to such incidents.[16] Hospitals will face numerous challenges confronting massive influx of patients suffering from bioterrorism disasters and emerging infectious diseases that may be contagious as well.[8,17] Numerous international studies have reported similar outcomes regarding the lack of preparedness of hospitals in facing biological disasters, such as weakness in planning and organizing,[5,10,18,19,20,21] communication,[7,11,22] surge capacity,[5,8,18,21,23] resources,[4,8,20,22] training and education,[6,10,19,20,21,22,23,24] infrastructure,[5,25] medical management,[7,12,22,25] supervision,[3,7,18,22] and safety and security.[7,16,24]

Emergency management programs are essential for hospitals' preparedness to deal with all probable hazards, including biological disasters and threats such as bioterrorism, emerging infectious diseases, and epidemics.[26] Failure in planning for biological disasters is due to the lack of standards or guidelines for the preparedness of health care and treatment centers.[27] The first step toward this direction is to assess the preparedness of hospitals in facing biological disasters as well as to increase the capacity and capability of hospitals in such incidents. Recognizing these gaps in hospitals will lead to identification of strengths and weaknesses and ultimately to a better preparedness in handling biological disasters.[8] In addition, the assessment of disaster preparedness to strengthen national health systems will also lead to the resiliency of health facilities.[28]

Various instruments have been developed to assess the preparedness of hospitals for emergencies and disasters, which are usually in the form of risk-based checklists, and often cannot assess the performance indicators of preparedness and response in biological disasters,[16] which may be due to unique features of the outbreak of diseases (disease dormancy periods, gradual development of symptoms, the need for monitoring systems to observe disease development and mortality, diagnosis and identification challenges, specific medicines, special protective equipment, isolation, etc.).[29] Having access to accurate information about the current status of hospital preparedness can act as a basis for systematic planning and broader discussion about relative costs, effectiveness and efficiency, environmental impacts, and overall community priorities.[21] A deep understanding of the complexities, barriers, and needs as well as sources for hospital preparation can play a significant role in preparing hospitals and health centers facing future biological events.[6] Therefore, identifying and assessing the existing instruments and extracting the effective factors in the preparedness of hospitals have a key role to play in policymaking in this field.

A scoping review is a form of scientific synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question, aimed at mapping key concepts and identifying research gaps related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge.[30] A scoping review is warranted where insufficient quantitative evidence is available and can include both quantitative and qualitative studies.[31]

Therefore, the present study systematically reviewing existing tools in this field aims to identify factors affecting the preparedness of hospitals for biological events, and the results of this study can play a significant role as a guide in designing and developing a standard assessment tool for hospital preparedness in biological events.

Methods

To determine the evaluated instruments or tools for hospital preparedness in biological disasters, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) methodological approach, as proposed by Tricco et al.[30] Scoping literature reviews are intended to be comprehensive and systematically identify the breadth and depth of a body of literature.[32] A scoping review is considered no less systematic than any other approach to mapping the literature in a particular field; but unlike meta-analyses, it does not seek to combine quantitative studies statistically nor claim to produce clear outcomes from that analysis. Rather, by including qualitative in addition to quantitative studies, this approach can allow mapping of different types of evidence and is particularly valuable if insufficient quantitative evidence is available.[31]

Eligibility criteria

Studies that used qualitative and quantitative methods focusing on measuring or evaluating instruments for hospital preparedness in biological events were included. Furthermore, articles were included for review if they met the following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed, (2) published in English language,(3) published between the years 2000 and 2017,(4) articles with full text (5) and articles that surveyed one of the biological incidents and threats (epidemics, pandemics, infectious diseases, public health emergencies, and biological agents). Exclusion criteria included studies the articles which did not have abstract and full text, as well as the duplicated articles and guidelines, book chapters, dissertations/theses, and conference.

Information sources and search

This study was conducted during December 2017 to review all published English articles in the field of evaluation instrument for hospital preparedness in biologic event. For this purpose, it has been studied databases including ISI web of science, PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, and Google Scholar. The search entered studies from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2017. Keywords used in the search were “Biological”, “CBRN”, “Biohazard,” “Biosafety,” “Mass Casualty Incidents,” “Biological Terrorism,” “Bioterrorism”, “Pandemics,” “Epidemics,” “Communicable Disease,” “Outbreak,” “Disaster,” “Incident,” “Emergency,” “Accidents,” “Event,” “Threat,” “Agent,” “Preparedness,” “Readiness,” “Vigilance,” Surge Capacity, “Operational preparedness,” “Response,” “Management,” “Hospital,” “medical facilities,” “Tool,” “Criteria,” “Standards,” “Questionnaire,” “Assessment,” “Appraisal,” “Measurement,” “Evaluation,” “Checklist.” Using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings; National Library of Medicine), synonyms of these keywords were also extracted. The strategy used combinations of keywords, Boolean operators depending on the controlled text options for each database. References in included papers and relevant excluded papers were examined for additional studies, and a nonsystematic search in Google Scholar was conducted as well. For example, the full PubMed search strategy is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search concepts and keywords in PubMed database

| Database | Controlled and natural keywords |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((((((((((((((((((((“biological event”[Title/Abstract]) OR “biological Incident*”[ Title/Abstract]) OR “biological disaster”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Biological emergency”[Title/Abstract]) OR “biological threat”[Title/Abstract]) OR “biological agent”[Title/Abstract]) OR “CBRN Incident”[Title/Abstract]) OR “CBRN emergencies”[Title/Abstract]) OR “chemical, biological”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Biohazard Releases”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Biological hazards”[Title/Abstract]) OR “biological Accidents”[Title/Abstract]) OR “CBRN Accidents”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Mass Casualty Incidents”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Biological Terrorism”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Bioterrorism”[Title/Abstract]) OR pandemics[Title/Abstract]) OR epidemics[Title/Abstract]) OR Communicable Disease[Title/Abstract]) OR outbreak[Title/Abstract] AND ((“2000/01/01”[PDat] : “2017/12/31”[PDat]) AND English[lang])) AND (((((((((((((“preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “readiness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital disaster preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “emergency preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Emergency response”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital Management”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital Response”[Title/Abstract]) OR “medical facilities preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital Surge Capacity”[Title/Abstract]) OR “operational preparedness”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital Biosafty”[Title/Abstract]) OR “vigilance”[Title/Abstract] AND ((“2000/01/01”[PDat] : “2017/12/31”[PDat]) AND English[lang])) AND (((((((((((((“evaluation tool”[Title/Abstract]) OR “readiness checklist”[Title/Abstract]) OR “tool*”[Title/Abstract]) OR “readiness tool”[Title/Abstract]) OR “preparedness Checklist”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital preparedness Tool”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Hospital Response Tool”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Criteria”[Title/Abstract]) OR “standards”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Questionnaire*”[Title/Abstract]) OR “Assessment*”[Title/Abstract]) OR “appraisal”[Title/Abstract]) OR “measurement” OR “Assessment TOOL”[Title/Abstract] AND ((“2000/01/01”[PDat] : “2017/12/31”[PDat]) AND English[lang]))) AND ((“2000/01/01”[PDat] : “2017/12/31”[PDat]) AND English[lang]) AND ((“2000/01/01”[PDat] : “2017/12/31”[PDat]) AND English[lang]) |

Selection of sources of evidence

Independent reviewers (M. A and H. R. Kh) screened abstracts and titles for eligibility. When the reviewers felt that the abstract or title was potentially useful, full copies of the article were retrieved and considered for eligibility by both reviewers. These activities helped us retrieve the most relevant articles and maintain the rigor of the study. Disparate opinions on relevance were solved through arbitration (AE).

Data charting process

After deleting articles that did not meet the criteria to enter the study, the full text of all articles that met the criteria were prepared and reviewed. A data charting form was jointly developed by two reviewers (M. A, H. R. Kh) to determine which variables to extract. In case of any difference in their opinion, a third researcher (M. F) was assisted. A pilot test was carried out with three studies, and the chosen variables were included in a.csv file. The two reviewers independently charted the data, discussed the results, and continuously updated the data charting form in an iterative process.

Data items

Finally, details from relevant studies which were extracted included first author and date of publication, participant, instrument type, evaluation method and technique, evaluation dimension and validity and reliability. After completing this form, the results obtained from reviewing the analytical articles, summed up and eventually reported.

Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

The form that has been used to assess the quality of the articles was the standard STORBE checklist.[33] It assigns 22 items to each observational study: two for the introduction and background, nine for the method, five for the results, and four for the discussion. To assess the quality of qualitative studies, the standard checklist COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies) was used.[34] This checklist with 32 items in 3 areas of research team and reflexivity with 8 questions, study design with 15 questions, and analysis and findings, assessed the qualitative articles.

Synthesis of results

We summarized the first author and date of publication, participant, instrument type, evaluation method and technique, evaluation dimension, and validity and reliability in each study. These summaries also include broad findings about factors that affect on hospital preparedness in biological event. We counted the number of studies included in the review that potentially met our inclusion criteria and noted how many studies had been missed by our search.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

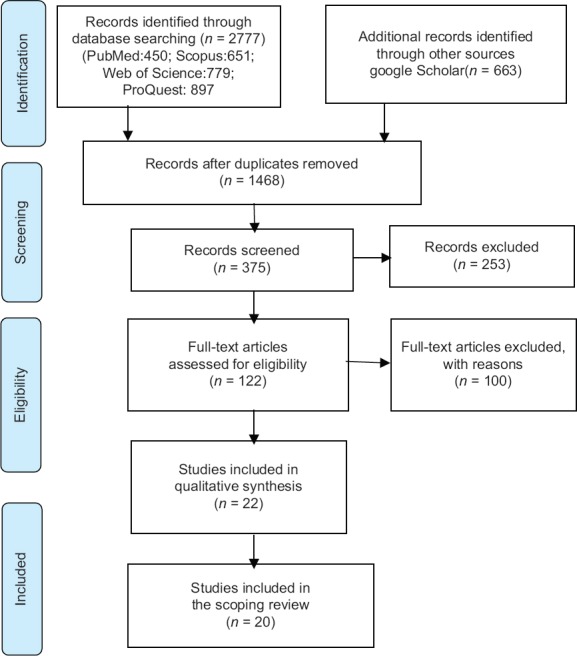

In a systematic review, during the initial search of keywords, 2777 articles were found in international sources and 663 articles were identified through the manual search of Google Scholar. As a result, the initial search contained 3440 articles. Among these articles, 1972 of them were removed due to duplicate. After studying the titles, 1093 and after reviewing abstract, 253 articles (In total 1346 articles) were excluded from the study, with 122 full text articles to be retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 100 were exuded for the following reasons: 83 did not directly quantify the effects of hospital preparedness in biological event and 15 were not considered to be original quantitative research (e.g., review articles, commentaries). We excluded 2 studies because we were unable to retrieve it. Finally, 22 articles related to the purpose of the study were selected for qualitative evaluation, full text review and data extraction, that 2 of which were excluded due to the poor quality of the external study. Reporting rates were lowest for sample size estimation, description of statistical methods, discussion of external validity, and discussion of limitations. The remaining 20 studies were considered eligible for this review. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of how the articles are identified in this study based on the PRISMA statement.[35](PRISMA) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Characteristics of sources of evidence

The information related to the assessed studies is shown in Table 2, based on first author and date of publication, participant, instrument type, evaluation method and technique, evaluation dimension and validity and reliability [Table 2].

Table 2.

An overview of characteristics of articles included

| Reference | First author date of publication | Participants | Instrument type | Evaluation methods and technique | Evaluation dimensions | Validity and reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Olivieri, 2017 Italy | 18 of experts | Assessment tool to evaluate hospital preparedness and response performance in CBRN emergencies | Methods: a cross-sectional tool Delphi technique 30 item for hospital preparedness and 59 item for hospital response | Seven categories (planning and organization, safety and security, standard operation process, communication, recourse, medical management, decontamination) | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [29] | Adini, 2014 Israel/Germmany | 228 of experts | Evaluation tool for assessing preparedness of medical facilities for biological events | Methods: a cross-sectional tool Delphi Technique, Focus groups, tabletop, functional and exercises, 172 parameter | Five categories and 15 subcategories: policy and planning, medical management, personnel, communication, and infrastructure | Reliability NO Validity NO (Only face Validity and qualitative content validity) |

| [10] | Wetter, 2001 USA | 224 of Hospital | Examined hospital preparedness for incidents involving chemical or biological weapons | Methods - cross-sectional questionnaire | Four categories (administrative plans, training, physical resources, and representative medication inventories) | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [22] | Tartari, 2015 Malta | 192 medical professionals Of 125 hospitals | Preparedness of institutions around the world for managing patients with Ebola virus disease | Methods cross-sectional questionnaire (checklist) With 76 question | Eight major sections: Administrative/operational support; Communications; Education and audit; Human resources, Supplies, Infection Prevention and Control practices and Clinical management of patients | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [18] | Higgins, 2004 USA | 118 hospitals | Instrument based on the Mass Casualty Disaster Plan Checklist and bioterrorism preparedness questionnaire based on a checklist developed for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. | Methods cross-sectional questionnaire (checklist) with 252 item | Seven major sections: Surge capacity, Emergency planning, Composite measures: (general response capability, ability to handle and control external traffic flow, preparation to deal with the news media, preparation to receive casualties and victims, preparation to deal with being out of communication or cut off from resources, and preparation to manage pharmaceuticals) WMD preparedness, Surveillance capabilities, regional planning and response, Impact of the metropolitan medical response system program | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [9] | Toyokawa, 2017 USA/Japon | 47 hospitals | Questionnaire based on that used in the PREPARE [Platform for European Preparedness Against (Re-) emerging Epidemics] | A cross-sectional study questionnaire | 5 issues: (1) Characteristics and Occupation; (2) Hospital Guidelines for Managing VHF; (3) Preparedness Activities; (4) Characteristics of Admission Rooms (5 (Human Resources and Occupational Issues | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [3] | Hopkins 2004 USA | Managers of ASTHOa, NACCHO, and CDC | SARS Preparedness Checklist for State and Local Health Officials | Methods - cross-sectional checklist with 53 item | 6 issues: Legal and Policy issues Authority, Surge capacity, Communication, Laboratory and Surveillance, Preparedness in other agencies | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [6] | Wong 2016 Canada | 85 medical directors of ED | Survey of Ebola Preparedness in ED | Methods - cross-sectional checklist | 4 sections: ED and hospital demographics, EVD training practices, understand specific challenges, attitudes toward EVD preparedness | (Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [4] | Reidy 2015 Ireland | 46 hospitals | Assess the preparedness of acute hospitals in an influenza pandemic | Methods - cross-sectional questionnaire With 42 Item | 6 issues: Pandemic emergency preparedness, Airborne isolation, Vaccines administration to healthcare workers, Stockpile of supplies | (Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [19] | Mortelmans 2014 Belgium | 138 hospitals | Preparedness of Belgian civil hospitals for chemical, biological, radiation, and nuclear incidents | Methods - cross-sectional questionnaire | 4 sections: hospital disaster planning, risk perception, availability of decontamination units, personal protective equipment, antidotes, radiation detection, Infectiologists, isolation measures, and staff training | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [5] | Dewar 2014 Australia | Hospital health managers | Hospital capacity and management preparedness for pandemic influenza in Victoria | Methods: cross-sectional, prospective study questionnaire and semi-structured interview | Main areas: hospital planning information; workforce issues; and infrastructure and surge capacity | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [25] | Mitchell 2012 United Kingdom | 50 nursing staff ED | emergency care nurses prepared for chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear or explosive incidents | Methods: cross-sectional questionnaire AND content analysis | Six key areas: (clinical waste, contaminated clothing, contaminated water and the management of the contaminated deceased), Triage, Chain of command, PODs, awareness of the range of Personal Protective Equipment and its appropriate use and the decontamination of people and equipment | Reliability YES Validity YES |

| [8] | Rebmann 2009 USA | Infection Control Professionals (ICPs) | Evaluate U.S. hospitals’ readiness to respond to a bioterrorism attack or outbreak of an emerging or reemerging infectious disease | Methods: cross-sectional questionnaire With 17 Item | : (Infectious disease emergency preparedness, Surge Capacity Plan, Negative Pressure Surge Capacity, Health care worker surge capacity, Medical equipment/supplies surge capacity) | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| [12] | Li 2008 China | 318 of hospitals | Hospital preparedness capacity for public health emergency in four regions of China | Methods: cross-sectional questionnaire with 192 item | 9 sections: hospital demographic data; PHE preparation; response to PHE in community; stockpiles of drugs and materials; detection and identification of PHE; procedures for medical treatment; laboratory diagnosis and management; staff training; and risk communication | Reliability NO Validity NO |

| First Author date of publication | Participants | Instrument type | Evaluation methods and technique | Evaluation dimensions | Validity and reliability | |

| Edwards 2008 USA[20] | 86 hospital EDs | Preparedness of Australian hospitals for disasters and incidents involving chemical, biological and radiological agents | Methods: Cross-sectional questionnaire | 4 issues: Hospital planning, available resources and training, and perceived | Reliability NO Validity NO |

|

| Reference | First author date of publication | Participants | Instrument type | Evaluation methods and technique | Evaluation dimensions | Validity and reliability |

| Thorne 2006 USA[11] | 111 hospitals from eight states | Bioterrorism Preparedness Questionnaire for Healthcare Facilities | Methods: cross-ectional questionnaire with 38 item | 5 issues: Administrative actions, Education, training, and drills, Surge capacity, Staff support, Communication Systems | Reliability NO Validity NO |

|

| Sarti 2015 Canada[7] | Hospital Staff | Hospitals preparedness and needs assessment to Ebola | Methods qualitative study focus groups, interviews and walk-throughs with 73 Item | 15 themes: Personal protective equipment; post exposure to virus; patient placement, room setup, logging and signage; intra hospital patient movement; inter hospital patient movement; critical care management; Ebola-specific diagnosis and treatment; critical care staffing; visitation and contacts; waste management, environmental cleaning and management of linens; postmortem; conflict resolution; and communication | Reliability NO Validity NO |

|

| Hui 2007 China[23] | 152 hospitals | hospitals preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks | Methods: cross-sectional questionnaire with 192 item | 6 issues: Information and their emergency plans, laboratory diagnosis capacity, medical treatment procedures for infectious diseases, stockpiles of drugs and personal protective equipment, and staff training | Reliability YES Validity YES |

|

| Bennett 2006 USA[21] | 102 licensed acute care hospitals | Preparedness of Hospitals for Managing Victims Affected by Chemical or Biological Weapons of Mass Destruction | Methods: cross-sectional self-administrated questionnaire with 53 item | 6 issues: The availability of functional preparedness plans, specific preparedness education/training, decontamination facilities, surge capacity, pharmaceutical supplies, and laboratory diagnostic capabilities of hospitals | Reliability YES Validity YES |

|

| Treat 2001 USA[24] | 30 Hospital | Hospital preparedness for weapons of mass destruction incidents | The structured interview | 6 issues: Level of preparedness, mass decontamination capabilities, training of hospital staff, and facility security capabilities | Reliability NO Validity NO |

|

CDC=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ASTHO=Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, ED=Emergency departments, NACCHO=National Association of County and City Health Officials, WMD=Weapon of mass destruction, PHE= Public health emergency, CBRN= Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear materials

Synthesis of results

Quantitative summary

The majority of research studies identified were from USA (45%, n = 9), followed by China and Canada (n = 2). Other countries with one study included Italy, Israel, Belgium, Malta, Ireland, Belgium, Australia, and United Kingdom [Table 2]. The vast majority of studies used cross-sectional analyses (90%, n = 18) and 2 of studies, use qualitative analyses (10%). Four studies out of 20 (20%, n = 4) were focused on CBRN Incident (20%), Ebola (15%, n = 3), infectious disease (15%, n = 3) and bioterrorism events (15%, n = 3), mass casualty disaster (10%, n = 2) and influenza pandemic (10%, n = 2), public health emergency (5%, n = 1), SARS (5%, n = 1) and biological events (5%, n = 1). Table 3 shows that half of the reviewed papers (n = 10, 50%) were published between 2012 and 2017, with most of the remainder being published between 2006 and 2011 (n = 6, 30%) or 2000-2005 (n = 4, 20%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

The information related to the assessed studies into Research (20 papers)

| Study characteristics | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Date of publication | ||

| 2000-2005 | 4 (20) | |

| 2006-2011 | 6 (30) | |

| 2012-2017 | 10 (50) | |

| Type of study | ||

| Cross-sectional (quantitative) | 18 (90) | |

| Qualitative | 2 (10) | |

| Incident | Reference | Frequency (%) |

| Type of incident | ||

| CBRN incident | [16,19,20,25] | 4 (20) |

| Ebola | [6,7,22] | 3 (15) |

| Infectious disease | [8,9,23] | 3 (15) |

| Bioterrorism events | [10,11,21] | 3 (15) |

| Mass casualty disaster | [18,24] | 2 (10) |

| Influenza Pandemic | [4,5] | 2 (10) |

| SARS | [3] | 1 (5) |

| Public health emergency | [12] | 1 (5) |

| Biological events | [29] | 1 (5) |

Qualitative summary (thematic analysis)

All twenty papers were subjected to qualitative content analysis of data, and based on the results from the analysis of these articles, factors affecting the preparedness of hospitals in biological events were identified. Seventy primary categories and subcategories were identified from the synthesis of the related studies.

Due to the large number of identified factors, and to have a more accurate analysis and for a better understanding, factors were classified in seven categories including planning, surge capacity (staff, equipment, resources and infrastructures), communication, training and education, medical management, surveillance, and standard operation process and other extracted categories were included within these seven categories.

The assessment tools reported in the current study considered various subcategories for each of the hospital preparedness elements. Table 4 shows the factors extracted from articles regarding hospital preparedness in biological events in terms of factor segregation.

Table 4.

Categories and subcategories of hospital preparedness in biological event: included studies organized by thematic analysis categories

| Main categories | Subcategories with references |

|---|---|

| Planning | Planning and Organization,[16] policy and planning[29], administrative plans,[10] Administrative/operational support,[22] Emergency planning,[4,18] Legal and Policy issues,[3] hospital disaster planning,[19] Regional planning and response,[18]: hospital planning information,[5] hospital planning,[20] Administrative actions,[11] information and their emergency plans,[23] functional preparedness plans,[21] |

| Surge capacity | Recourse[stuff],[6,7,9,10,12,16,22,23] Staff,[7,9,22,25,29] infrastructure,[5,6,7,19,25,29] Surge capacity[3,4,5,6,[8,18,11,18,21] |

| Communication | Communication,[7,16,29] preparation to deal with the news media,[18] Risk communication,[12] Communication Systems,[11] |

| Training and education | Education and audit,[22] Hospital Guidelines,[9] training practices,[6] staff training,[12,19,23] training,[20] Education,[11] training, and drills,[11] education/training,[21] training of hospital staff.[24] |

| Medical management | Medical management,[16,29] Clinical management of patients,[22]preparation to receive casualties and victims,[18] Triage,[25] procedures for medical treatment[12], critical care management, diagnosis and treatment; [7], medical treatment procedures[23] |

| Surveillance | Surveillance capabilities[18], Laboratory and Surveillance,[3]; laboratory diagnosis and management,[12] laboratory diagnosis capacity,[23] laboratory diagnostic capabilities[21] |

| Standard operation process | Standard operation process,[16] intra hospital patient movement; inter hospital patient movement, visitation and contacts, environmental cleaning and management of linens; postmortem,[7] waste management,[7,25] |

| Safety and security | Ability to handle and control external traffic flow,[18] availability of decontamination units,[19] personal protective equipment,[7,19,23,25] safety and security,[16] facility security capabilities.[24] |

Discussion

Various studies have been carried out on the factors affecting the preparedness of hospitals in biological events. Most of them have reported on factors affecting hospital preparedness confronting any of the various types of emergencies such as public health emergencies, infectious diseases, epidemics and bioterrorism events and incidents with large number of injuries [Table 3]. Our findings indicate a paucity of research focusing specifically on dissemination of knowledge with in hospital preparedness in biological event and a limited number of studies on implementation in this field. The identified articles showed a wide variability of factors relevant for hospital preparedness in biological event. Some of these factors may have been overlapping in one or more domains which were included in the dominant domain and were discussed accordingly. To, the factors affecting the preparedness were examined in seven areas including planning, surge capacity, communication, training and education, medical management, surveillance, and the standard operation process. This article provides an overview of the current knowledge on hospital preparedness in biological events. This scoping review of peer-reviewed studies aims to identify existing research on hospital preparedness tools used in biological events and factors affecting hospital preparedness in such incidents.

Bioterrorism attacks or outbreak of emerging and recurrent infections is considered as a serious threat to the healthcare and safety of citizens and can lead to a large financial burden on the society.[8,36] Hospital preparedness plays a vital role in early diagnosis and management of emergency cases caused by various biological events.[12] There are significant differences regarding the pathophysiology of injuries caused by these events, such as dissemination, rapid expansion, and the need for resources and special preparedness compared to other disasters and incidents.[36,37] Studies have shown that, despite the increase in emergency operation plan, information sharing technology, new equipment, communication, and monitoring systems, as well as increased preparation training programs, the level of self-esteem of treatment teams in managing certain biological events is seen to be low.[29,38]

Planning, designing, and organizing hospitals with appropriate infrastructure based on specified standards that can respond to biological and hazardous incidents as an operational and practical measure to reduce costs are considered as preventive and mitigating acts to deal with such disastrous events.[9] Planning and organizing are among the main pillars of hospital preparedness and have a major impact on hospitals' responses in confronting such events.[39] Emergency programs and plans are the basis of operational protocols related to emergencies caused by biological incidents.[40] These plans can reduce the outbreak and incidence of diseases, hospitalization, mortality rate, maintenance of essential hospital services, and the economic and social consequences of diseases caused by biological disasters.[4]

One of the characteristics of the biologic emergency centers is that they act suddenly and unpredictably. Therefore, hospitals must have plans to ensure adequate response to such incidents, including medicine preservations, medical equipment, and structural facilities.[12] In addition, a periodic review as well as updated emergency plans can increase the emergency response capacity of healthcare institutions against such incidents.[23]

One of the most important components of hospital preparation for responding to biological events is the issue of surge capacity. The ability to provide medical care during a sudden increase in the number of patients or injuries caused by emergency and disasters is one of the main concerns of healthcare systems, especially in hospitals.[41] Different studies, in addition to the use of available resources in order to manage the sudden influx of injured individuals or patients into the hospital, suggest the surge capacity as hospitals' ability to increase the available resources to respond to emergencies and disasters.[42] Each surge capacity plan has three main components that are: staff (human resources), stuff (specialized and nonspecialized) and facilities and structures (physical space).[2] There is no standard and unique criterion as the basis for assessing the hospitals' ability to increase their capacity in emergency and disasters. This difference can be due to the diversity in structural, economic, and demographic features of different countries.[43]

One of the most important parts of the program is increasing the number of staff or human resources. Studies in this area have shown that half of the healthcare staff may not contribute to biological events such as influenza.[44] The desire of each employee to respond to such events is closely related to the type of service that they deliver and the importance of understanding the role that they play in confronting such events role.[5] Among the barriers that exist in employee participation during pandemic diseases are transportation problems, employee responsibilities as caretakers, lack of awareness of employees toward the risks or their role in responding to such incidents, and employees' fear of self or family exposure to such diseases through their participation in healthcare programs.[45]

Communication is the factor that involves activities that provide accurate and reliable information to and cooperation with the public, other organizations, and community institutions responding to the disaster. Communication is considered as one of the main challenges in disasters, especially in biological events,[16] and these events are capable to create many psychological and physical problems for the general public as well as the medical staff exposed to the disease.[12] No hospital or therapeutic system can manage to cure the diseases caused by biological events without the participation of organizations involved in these incidents and public participation. Therefore, to have an effective management in such disasters, hospitals need to communicate and collaborate with other local healthcare networks as public service providers. Problems such as lack of communication, the coordination of intersections within the hospital and outsourced organizations may prevent resources from being available, limit on-time predictions as well as effective communication and respond to such incidents.[46] On the other hand, risk communication is an important part of responding to biological events, such as disasters causing public health emergencies,[12] and it is considered as the key to ensure a full, transparent and rapid exchange of information and helping hospitals to respond promptly and reduce the serious consequences of disasters. In fact, it will help people make appropriate decisions and increase their resilience.[47]

Healthcare personnel training in disaster preparedness is another factor of importance and affects maintenance and promotion of human resources. Since emergencies such as biological incident, that require a major response, happen quite infrequently, organizations and staff need to exercise the procedures and skills for these events to be prepared to respond. Therefore, training and education play an important role in the emergency preparedness of hospitals in emergencies and disasters.[25] Staff absenteeism in diseases caused by biological events such as pandemic influenza may be caused by the fear of being exposed to viruses and the uncertainty of employees to work in an unsafe environment.[48] Training and education can play an important role in reducing employee absenteeism at work, for the front line employees may not be completely aware of the preventive measures.[49] Moreover, designing and performing realistic exercises can be very effective in identifying the strengths, weaknesses, and capacity of hospital programs. There are various problems regarding the performance of exercises, especially the field exercises in hospitals, including time, cost and resource constraints, and disruptions in the routine emergency processes as well as access to emergency services.[20] Research has shown that exercises such as tabletop predisaster-based exercises, in addition to being cost-effective, will be a useful tool and will increase staff's knowledge and awareness regarding emergencies and disasters.[50]

One of the important challenges that medical staff often face in biological events is the personal protective equipment (PPE) that due to the lack of familiarity of most nurses with various types of PPE, practical training on how to use these equipment is necessary because of the fact that the proper use of this equipment, not only provides safety and security for the staff but it also is of high critical importance regarding the continuity of performance and functioning of healthcare centers in biological disasters.[25] Hence, the training of employees to take care of patients in biological events should be considered as an important task to be taken seriously by healthcare administration managers and policymakers. For this purpose, it is beneficial to utilize the contributions of the National Medical Center, World Health Organization, and other international agencies in this area and train the staff according to evidence-based methods and try to improve and develop the challenges and shortcomings that healthcare institutions face in caring such patients.

Though hazardous events (e.g., biological incidents) do not usually occur, they have a major impact on public health and resource consumption in hospitals and societies. Given the fact that biological events such as public health emergencies occur suddenly and their occurrence is relatively low, most healthcare providers do not have enough experience and preparedness in such disastrous situations.[51] Therefore, medical management in such incidents is different than other emergencies. Mortality and injury rates are largely influenced by the provision of effective medical services including general supportive care and the use of antibiotics, antidotes, isolation, decontamination, vaccination, and triage.[16] Martinese et al. (2009) and Dewar et al. also suggested that strategies such as vaccination, the provision of influenza antiviral drugs, and the training and communication of the staff in a structured way could play an important role in motivating them and reducing their absenteeism.[5] On the other hand, one of the challenges of nursing and medical staff as for the difference in biological events is the triage skill that may not be effectively implemented, and therefore, in many studies, triage is considered a key skill that requires targeted training in facing such events.[25]

An important part of public health programs in any country is to observe the contagious diseases for the purpose of prevention and control, identifying the prevalence and consequences of diseases, interventions, assessing the effectiveness of plans in terms of caretaking, management, and allocation of resources due to the importance of these diseases, and the effects which they have on public health.[52,53] Early detection and identification of biological diseases such as public health emergencies is one of the important goals of health centers to respond promptly and effectively, as well as an essential precondition for choosing appropriate measures for prevention and treatment of such incidents.[54] Collaboration and interorganizational efforts to assess local hazards, developing and completing new technology for screening new pathogens, managing large amounts of shared information, rapid and effective communication and cooperation with local communities are some of the essential components for early diagnosis and response to biological incidents.[55] Several studies mentioned the reasons for the failure in hospital reporting as the low level of medical staff awareness about the reporting system, the high workload in hospitals, the lack of a standardized reporting system, and the lack of documentation.[56] The availability of PPE and their proper use, the availability and proper use of laboratory equipment, the adequacy of staff and infrastructure requirements, including laboratory space, are among the elements related to the preparedness and accountability of the clinical laboratories. It is evident that in such circumstances, the importance of implementing an active, comprehensive, and full-scale caretaking system with the cooperation of health system staff is an essential issue in the primary healthcare and medical services system.[9]

The standard operating procedure (SOP) is a necessary component for emergency management.[16] On the other hand, the lack of familiarity of hospital staff and managers with diseases caused by biological incidents and the effective response to them requires full implementation of international standards.[6] Among these standards, there are the creation of a safe environment for the secured transportation of patients and staff, considering waiting rooms for the purpose of removing and wearing PPEs, decontamination processes, and waste management programs.[57] One of the main challenges in this regard was the lack of a SOPs and a consistent and coordinated framework for health centers.[5] Therefore, designing a SOP can play a significant role in preparedness of hospitals and staff and their respond to biological incidents.

Safety and security in biological emergencies are of highest priority for early responders such as healthcare employees.[16] Hospitals' emergency departments are patients' main entry points to the health care system and their staff are committed to provide services to all patients; therefore, it is likely that employees of such sections, especially those dealing with patients with acute illnesses, are at greater risk comparing to other health care centers.[6] Study has shown that nurses' tendency to respond to hazardous incidents such as biological events may depend on their own personal and domestic safety as well as having the required clinical competencies, and such matters should be taken into account.[25,26] There are numerous international reports regarding secondary contamination of hospital staff after incidents involving chemical and biological hazards. Therefore, employees should increase their knowledge about the standard decontamination process, managing the infected waste and contaminated bodies.[25,26,58]

Strengths and limitations

The extensive list of all potentially relevant search terms and search of multiple high-quality databases, along with strict exclusion criteria and the rigorous screening process, add to the scientific merit of this review. The review was further strengthened by the number and variety of papers included, and the use of standardized data extraction spreadsheets to ensure that all papers underwent the same data extraction process. This report was made according to the recommendations of the PRISMA-ScR. Our scoping review has some limitations. We also did not search across unpublished studies and gray literature, but only considered studies identified through database searches. The decision to include only papers published in peer-reviewed journals also presents a publication bias; thus, future studies may include gray literature.

Conclusion

This scoping review has demonstrated that hospital preparedness provides a valuable infrastructure for preparing and responding to biological disasters. We analyzed 20 articles, including reports of various studies that examined hospital preparedness and examinations of the role of hospitals in preparing for and responding to biological disasters. We reviewed both quantitative and qualitative studies on hospital preparedness in this field. The findings of the research showed that currently, there is no comprehensive tool to assess the preparedness of hospitals in biological events, and so far, no methodology was able to determine a method, tool, or comprehensive indicator that has a standard methodological approach regarding a systematic review and toolmaking as well as a comprehensive and qualitative research methodology for various aspects of hospital preparedness in biological events. Moreover, the available tools lack appropriate psychometrics, and none of the available tools has evaluated all the dimensions regarding the preparedness of hospitals in such events. Every country and organization have extended the indicators and methods that conform to its cultural background. Healthcare and treatment systems need assessment tools that have been developed based on a systematic review using the knowledge of experts and have been validated through appropriate psychometrics. The data from the present study can serve as a valuable input for hospitals' preparedness planning to improve emergency plans in biological and mass casualty incidents at the regional, state, national and country levels according to specific conditions of various countries. It can also be used as a clear vision for the healthcare managers and policymakers in their future plans and programs to confront the challenges identified by healthcare institutes in biologic events.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sandström BE, Eriksson H, Norlander L, Thorstensson M, Cassel G. Training of public health personnel in handling CBRN emergencies: A table-top exercise card concept. Environ Int. 2014;72:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khankeh H. Disaster Hospital Preparedness, National Plan. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkins RS, Misegades L, Ransom J, Lipson L, Brink EW. SARS preparedness checklist for state and local health officials. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:369–72. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reidy M, Ryan F, Hogan D, Lacey S, Buckley C. Preparedness of hospitals in the republic of Ireland for an influenza pandemic, an infection control perspective. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:847. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2025-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewar B, Barr I, Robinson P. Hospital capacity and management preparedness for pandemic influenza in victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:184–90. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CH, Stern S, Mitchell SH. Survey of ebola preparedness in Washington state emergency departments. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10:662–8. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarti AJ, Sutherland S, Robillard N, Kim J, Dupuis K, Thornton M, et al. Ebola preparedness: A rapid needs assessment of critical care in a tertiary hospital. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E198–207. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebmann T, Wilson R, LaPointe S, Russell B, Moroz D. Hospital infectious disease emergency preparedness: A 2007 survey of infection control professionals. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toyokawa T, Hori N, Kato Y. Preparedness at Japan's hospitals designated for patients with highly infectious diseases. Health Secur. 2017;15:97–103. doi: 10.1089/hs.2016.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetter DC, Daniell WE, Treser CD. Hospital preparedness for victims of chemical or biological terrorism. American Journal of Public Health. 2001 May;91(5):710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorne CD, Levitin H, Oliver M, Losch-Skidmore S, Neiley BA, Socher MM, Gucer PW. A pilot assessment of hospital preparedness for bioterrorism events. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2006 Dec;21(6):414–22. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0000412x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Huang J, Zhang H. An analysis of hospital preparedness capacity for public health emergency in four regions of China: Beijing, Shandong, Guangxi, and Hainan. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop JF, Murnane MP, Owen R. Australia's winter with the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2591–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0910445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fineberg HV. Pandemic preparedness and response – Lessons from the H1N1 influenza of 2009. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1335–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnstone MJ, Turale S. Nurses' experiences of ethical preparedness for public health emergencies and healthcare disasters: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16:67–77. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivieri C, Ingrassia PL, Della Corte F, Carenzo L, Sapori JM, Gabilly L, Segond F, Grieger F, Arnod-Prin P, Larrucea X, Violi C. Hospital preparedness and response in CBRN emergencies: TIER assessment tool. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017 Oct 1;24(5):366–70. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, DeAtley C, Barbisch D, Bogdan GM, Cantrill S. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Annals of emergency medicine. 2004 Sep 1;44(3):253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins W, Wainright C, Lu N, Carrico R. Assessing hospital preparedness using an instrument based on the mass casualty disaster plan checklist: Results of a statewide survey. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortelmans LJ, Van Boxstael S, De Cauwer HG, Sabbe MB. Terror australis 2004: Preparedness of australian hospitals for disasters and incidents involving chemical, biological and radiological agents. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10:125–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards NA, Caldicott DG, Aitken P, Lee CC, Eliseo T. Terror australis 2004: Preparedness of australian hospitals for disasters and incidents involving chemical, biological and radiological agents. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10:125–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett RL. Chemical or biological terrorist attacks: An analysis of the preparedness of hospitals for managing victims affected by chemical or biological weapons of mass destruction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2006;3:67–75. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2006030008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tartari E, Allegranzi B, Ang B, Calleja N, Collignon P, Hopman J, Lang L, Lee LC, Ling ML, Mehtar S, Tambyah PA. Preparedness of institutions around the world for managing patients with Ebola virus disease: an infection control readiness checklist. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control. 2015 Dec;4(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui Z, Jian-Shi H, Xiong H, Peng L, Da-Long Q. An analysis of the current status of hospital emergency preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks in Beijing, China. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treat KN, Williams JM, Furbee PM, Manley WG, Russell FK, Stamper CD., Jr Hospital preparedness for weapons of mass destruction incidents: An initial assessment. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:562–5. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.118009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell CJ, Kernohan WG, Higginson R. Are emergency care nurses prepared for chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear or explosive incidents? Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20:151–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rebmann T 2008 APIC Emergency Preparedness Committee. APIC state-of-the-art report: The role of the infection preventionist in emergency management. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebmann T. Pandemic preparedness: Implementation of infection prevention emergency plans. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(Suppl 1):S63–5. doi: 10.1086/655993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayntun C, Rockenschaub G, Murray V. Developing a health system approach to disaster management: A qualitative analysis of the core literature to complement the WHO Toolkit for assessing health-system capacity for crisis management. PLoS currents. 2012 Aug;22:4. doi: 10.1371/5028b6037259a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adini B, Verbeek L, Trapp S, Schilling S, Sasse J, Pientka K, Böddinghaus B, Schaefer H, Schempf J, Brodt R, Wegner C. Continued vigilance–development of an online evaluation tool for assessing preparedness of medical facilities for biological events. Frontiers in public health. 2014 Apr;14(2):35. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-scR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixon-Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A, Jones DR, Miller T, Sutton AJ, Shaw RL, Smith JA, Young B. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative research. 2006 Feb;6(1):27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1291–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnes K. Cost of anthrax attacks ''surges.''BBC News. 2001 Oct 31; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vardell E. Chemical hazards emergency medical management (CHEMM) Med Ref Serv Q. 2012;31:73–83. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2012.641852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung K, Lam E, Wong M, Wong T, Chan E, Graham C. Emergency physicians' preparedness for CBRNE incidents in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2013;20:90–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.“Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans.”. 2010:1–124. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas J. Draft Capacity Assessment Guidelines & The Program Approach. Assessment Levels and Methods. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheikhbardsiri H, Raeisi AR, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Rezaei F. Surge capacity of hospitals in emergencies and disasters with a preparedness approach: A systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017;11:612–20. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dayton C, Ibrahim J, Augenbraun M, Brooks S, Mody K, Holford D, et al. Integrated plan to augment surge capacity. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:113–9. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLia D. Annual bed statistics give a misleading picture of hospital surge capacity. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006 Oct 1;48(4):384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balicer RD, Barnett DJ, Thompson CB, Hsu EB, Catlett CL, Watson CM, et al. Characterizing hospital workers' willingness to report to duty in an influenza pandemic through threat – And efficacy-based assessment. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:436. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Strauss E, Paillard-Borg S, Holmgren J, Saaristo P. Global nursing in an ebola viral haemorrhagic fever outbreak: Before, during and after deployment. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1371427. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1371427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dooley JR, Wang JW, Bodduluri RM, West JB inventors; Accuray Inc, assignee. Flexible treatment planning. United States patent US 7,298,819. 2007 Nov 20; [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Risk Reduction and Emergency Preparedness: WHO Six-Year Strategy for the Health Sector and Community Capacity Development. World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siddle J, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Brice J. Survey of emergency department staff on disaster preparedness and training for ebola virus disease. Am J Disaster Med. 2016;11:5–18. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2016.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khorram-Manesh A, Ashkenazi M, Djalali A, Ingrassia PL, Friedl T, von Armin G, et al. Education in disaster management and emergencies: Defining a new european course. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9:245–55. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams J, Nocera M, Casteel C. The effectiveness of disaster training for health care workers: A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:211–22. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.030. 222.e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crupi RS, Asnis DS, Lee CC, Santucci T, Marino MJ, Flanz BJ. Meeting the challenge of bioterrorism: Lessons learned from west nile virus and anthrax. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:77–9. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2003.50015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keramarou M, Evans MR. Completeness of infectious disease notification in the United Kingdom: A systematic review. J Infect. 2012;64:555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiller KM, Stoneking L, Min A, Rhodes SM. Syndromic surveillance for influenza in the emergency department-a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haverkort JJ, Minderhoud AL, Wind JD, Leenen LP, Hoepelman AI, Ellerbroek PM. Hospital preparations for viral hemorrhagic fever patients and experience gained from admission of an ebola patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:184–91. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.151393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacobsen KH, Aguirre AA, Bailey CL, Baranova AV, Crooks AT, Croitoru A, et al. Lessons from the ebola outbreak: Action items for emerging infectious disease preparedness and response. Ecohealth. 2016;13:200–12. doi: 10.1007/s10393-016-1100-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ, Poole C, MacDonald PD, Maillard JM. Completeness of communicable disease reporting, North Carolina, USA, 1995-1997 and 2000-2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:23–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.100660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Healthcare E. Atlanta: Emory Healthcare; 2014. Nov, Emory healthcare Ebola preparedness protocols. https://www. emoryhealthcare. org/ebola-protocol/ehc-message. html . [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luther M, Lenson S, Reed K. Issues associated in chemical, biological and radiological emergency department response preparedness. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2006;9:79–84. [Google Scholar]