Abstract

Background

Chemotherapeutic agents such as topotecan can be used as salvage treatment in epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC). The effects of using topotecan as a therapeutic agent have not been previously been systematically reviewed.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of topotecan for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), (Issue 6, 2015); Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group (CGCRG) Specialised Register (Cochrane Library Issue 6, 2015); MEDLINE (January 1990 to 30 September 2015); EMBASE (January 1990 to 30 September 2015); The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) database (to 30 September 2015); CBM (Chinese Biomedical Database) (January 1990 to 30 September 2015).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which randomise participants with ovarian cancer to single or combined use of topotecan versus interventions without topotecan.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted and analysed data.

Main results

Six multicentre pre‐market RCTs involving 5640 participants were included in this review. We considered three studies to be at a low risk of bias and three studies to be at an unclear or moderate risk of bias due to inadequate reporting. Survival results were inconsistently presented across study reports and comparisons and types of participants differed between studies, therefore we were unable to pool these data. In the seven studies, the median overall survival (OS) of participants treated with topotecan ranged from 39.6 weeks to 63 weeks. One study was conducted in women with primary advanced‐stage ovarian cancer; the others were conducted in women with relapsed ovarian cancer. No significant difference in OS was found in studies comparing topotecan with paclitaxel (one study, P = 0.44), or topotecan plus thalidomide (one study, P = 0.67). No significant difference in OS was found in the study comparing topotecan with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) (one study, P = 0.341), however in the platinum‐sensitive subgroup of this study, topotecan was associated with a shorter median survival time than PLD (70 weeks versus 108 weeks). Topotecan was associated with a significantly longer OS compared with treosulfan (one study, P = 0.0023).

Median progression‐free survival (PFS) with topotecan ranged from 16 to 23 weeks in the included studies. There was no statistically significant difference in PFS when topotecan was compared with PLD (P = 0.095); In one of two studies of topotecan compared with paclitaxel, topotecan delayed progression more effectively (median 14 weeks versus 23.1 weeks; Risk Ratio (RR) 0.587, 95% CI P = 0.0021) and treosulfan (median 12.7 weeks versus 23.1 weeks, P = 0.0020); however, the PFS for topotecan alone was significantly shorter than for topotecan plus thalidomide (four months versus six months, P = 0.02). One study compared topotecan with no further cytotoxic or non‐cytotoxic treatment and found no significant difference in OS (P = 0.30) or PFS (HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.23; P = 0.31) between study arms.

Topotecan was associated with more severe haematological toxicity compared with paclitaxel (RR 1.03 to 14.46), PLD (RR 1.73 to 27.12), and treosulfan (50% versus 12%)This evidence ranges from low to moderate quality.

Authors' conclusions

For women with platinum‐resistant ovarian cancer, topotecan may be as effective as paclitaxel and PLD for OS, and may delay disease progression better than paclitaxel, however more evidence is needed. Topotecan plus thalidomide appears to be more effective in delaying progression than topotecan alone, but the combination does not improve OS compared with topotecan alone. Topotecan appears to be associated with improved survival compared with treosulfan. For women with platinum‐sensitive ovarian cancer, topotecan appears to be less effective than PLD, and treatment with topotecan after receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel,has no additional survival benefits. Topotecan is associated with severe haematological toxicity and this needs to be considered when evaluating treatment options. Large, high quality, post‐market RCTs are required to confirm that topotecan is effective and safe.

Plain language summary

Topotecan is an active second line chemotherapeutic drug, used to treat patients with relapsed ovarian carcinoma

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common malignancies of the female genital tract which accounts for approximately 3% of all cancer in women, and is the leading cause of death from gynecological cancer in developed country. Appropriate initial surgical management by a gynaecologic oncologist is important for survival. Patients with early stage, low‐risk tumours may be cured with surgery alone. Current first‐line management for advanced ovarian cancer consists of cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy. The majority of patients relapse between 18 to 22 months later. Management of recurrent ovarian cancer remains a challenge. Goals for treating relapsed ovarian cancer include improving symptoms, enhancing quality of life (QOL), and prolonging survival. Agents that are potentially well suited for extended treatment intervals may include such properties as absence of cumulative toxicity, non cross resistance, positive benefit on QOL, and convenient schedule. Of the agents available for the treatment of relapsed ovarian carcinoma, topotecan is one of the most widely studied and characterised. This review aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topotecan in the management of ovarian cancer.

Six multicentre, well designed pre‐market studies including 5640 participants were eligible for this review. Pooling analysis did not performed in four trials due to the data not similar enough, but conducted for two trials. Topotecan appears to have a similar level of effectiveness as paclitaxel, topotecan plus thalidomide, and superior than treosulfan, but shorter overall survival than pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Topotecan delays progression of disease than paclitaxel, treosulfan; topotecan plus thalidomide superior than topotecan alone on PFS, but topotecan alone significantly shorter than topotecan plus thalidomide. Further consolidation treatment with topotecan does not improve PFS for participants with advanced ovarian cancer who respond to initial chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Evidence from three studies were high quality, the remaining studies were low or moderate due to poor reporting of the methodology. For gaining the better representativeness, more large, well‐designed randomised controlled trials of post‐market drug are required in the future.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Ovarian cancer accounts for approximately 3% of all cancer in women. A woman's risk of having ovarian cancer during her lifetime is 1.7% or about 1 in 58. Her lifetime chance of dying from ovarian cancer is 1 in 98. The median age at diagnosis is 63 years and the incidence increases with age, peaking in the eighth decade. Ovarian cancer ranks fourth in cancer deaths among women, accounting for more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system. Approximately 85 to 90% of ovarian cancers are epithelial ovarian carcinomas (EOCs) which are classified by different cell features under the microscope into serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, Brenner, mixed, and undifferentiated carcinomas (ACS 2005; Winter‐Roach 2012). Primary ovarian cancer is given a grade (1 to 3) and stage (I to IV). Grade 1 closely resembles normal tissue and tends to have a better prognosis than grade 3. The stage of tumour spread can be ascertained during surgery (See Table 6: FIGO Staging of Primary Ovarian Cancer).

1. Table 01. FIGO Staging of Primary Ovarian Cancer.

| Stage | Description |

| Stage | Description |

| Stage I | Growth of the cancer is limited to the ovary or ovaries. |

| Ia | Growth is limited to one ovary and the tumour is confined to the inside of the ovary. There is no cancer on the outer surface of the ovary. There are no ascites present containing malignant cells. The capsule is intact. |

| Ib | Growth is limited to both ovaries without any tumour on their outer surfaces. There are no ascites present containing malignant cells. The capsule is intact. |

| Ic | The tumour is classified as either Stage IA or IB and one or more of the following are present: (1) tumour is present on the outer surface of one or both ovaries; (2) the capsule has ruptured; and (3) there are ascites containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings. |

| Stage II | Growth of the cancer involves one or both ovaries with pelvic extension. |

| IIa | Disease spread to involve the fallopian tubes and/or uterus . |

| IIb | The cancer has extended to other pelvic organs. |

| IIc | The tumour is classified as either Stage IIA or IIB and one or more of the following are present: (1) tumour is present on the outer surface of one or both ovaries;(2) the capsule has ruptured; and (3) there are ascites containing malignant cells or with positive peritoneal washings. |

| Stage III | Growth of the cancer involves one or both ovaries, and one or both of the following are present: (1) the cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to the lining of the abdomen; and (2) the cancer has spread to lymph nodes. The tumour is limited to the true pelvis but with histologically proven malignant extension to the small bowel or omentum. |

| IIIa | During the staging operation, the practitioner can see cancer involving one or both of the ovaries. No cancer is grossly but microscopic visible in the abdomen and it has not spread to lymph nodes. |

| IIIb | The tumour is in one or both ovaries, and deposits of cancer are present in the abdomen that are large enough for the surgeon to see but not exceeding 2 cm in diameter. The cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes. |

| IIIc | The tumour is in one or both ovaries, and one or both of the following is present: (1) the cancer has spread to lymph nodes; (2) the deposits of cancer exceed 2 cm in diameter and are found in the abdomen. |

| Stage IV | Disease affecting the liver parenchyma, thorax or more distally |

Due to the often asymptomatic nature of the early stages of the disease, almost 70% of women with common epithelial ovarian cancer are not diagnosed until the disease is at an advanced stage ‐ i.e. has spread to the upper abdomen (stage III) or beyond (stage IV). The five year survival rate for these women is 15% to 20%, whereas the five year survival rate for stage I disease patients approaches 90% and for stage II approaches 70% (ACS 2005; NOCC 2004).

Since stage IIb and IIc are often treated similarly to more advanced disease, a stricter definition of early stage disease may be to include all of stage I and stage IIa (Winter‐Roach 2012). Access to appropriate initial surgical management by a gynaecologic oncologist is important because treatment and survival are affected by appropriate surgical staging and debulking of the tumour. Patients with early stage, low‐risk tumours may be cured with surgery alone (Hensley 2002). Current first‐line management for advanced primary ovarian cancer consists of cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy, usually with a platinum/taxane combination. Although this approach has been shown to achieve overall response rates of 70% to 80% in clinical trials, the majority of patients relapse between 18 to 22 months later.

The management of relapsed ovarian cancer remains a challenge to the clinician (Ahmad 2004; Jablonska 2004). The goals for treating relapsed ovarian cancer include improving symptoms, enhancing quality of life (QOL), and prolonging survival. Agents that are potentially well‐suited for extended treatment intervals should include such properties as absence of cumulative toxicity, non cross resistance, positive benefit on QOL, and convenient scheduling (Herzog 2004). Platinum‐derivatived monotherapy (carboplatin) appears to be the most adequate treatment for relapsed platinum‐sensitive ovarian cancer (defined as having an initial response of at least six months to platinum‐based chemotherapy). Patients with platinum‐refractory (relapse within one month of platinum‐based therapy), platinum‐resistant (relapse within six months of platinum‐based therapy), as well as advanced platinum‐sensitive ovarian cancer can be considered for radiotherapy and non‐platinum agents such as oral etoposide, topotecan, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) depending on the stage of the disease (Ahmad 2004; Jablonska 2004; Johnston 2004; Ledermann 2004). Of the agents available for the treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer, topotecan is one of the most widely studied and characterised (Ahmad 2004).

Description of the intervention

Topotecan was semi‐synthesized as a camptothecin derivative in 1990. It prevents DNA replication in cancer cells by inhibiting the enzyme topoisomerase I. The main toxicities associated with topotecan are haematological, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anaemia; however, these toxicities are usually predictable, of short duration, noncumulative, and manageable with dose reduction and dose delay (Bochennek 2013; Safra 2013; Zighelboim 2013). Non haematological toxicity is generally mild and mainly consists of gastrointestinal events, hair loss and fatigue (Bokkel 1997;Herzog 2002). The standard dosing regimen is 1.5 mg/m²/day on days 1 to 5 of a 21‐day cycle, with response rates ranging from 13% to 33%. Although the resulting hematologic toxicities are reversible and noncumulative, this schedule is associated with significant myelosuppression (Morris 2002). Thus, in order to develop an optimal schedule of topotecan and to find a balanced point of its benefits and harms in treating ovarian cancer, new administration formulations of different doses, schedules and routes, such as weekly topotecan (Bhoola 2004; Levy 2004; Stathopoulos 2004; Stathopoulos 2004), every two week topotecan (Kakolyris 2001), three day topotecan (Miller 2003), oral topotecan (Clarke‐Pearson 2001; Markman 2004), decreased dosage (Gordon 2004a) and low dose continuous infusion of topotecan (Denschlag 2004) have been explored in a number of studies.

Why it is important to do this review

Topotecan as a therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer has not previously been systematically reviewed.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of topotecan in the management of ovarian cancer for first and second line treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs in all languages were eligible for inclusion in the review. Studies published only in abstract form or non‐peer reviewed journals whereby no further or insufficient information could be procured from the authors were excluded.

Types of participants

Patients over 18 years of age with ovarian cancer at any stage

Patients who were previously untreated or had ceased previous chemotherapy regimens for at least four weeks

Patients complicated with severe disorder or infection in other organs (heart, lung, kidney, bone marrow, etc) were excluded.

Types of interventions

Single‐agent topotecan versus other agents as second‐line treatment;

Single‐agent topotecan versus topotecan plus other agents;

Topotecan plus other agents versus the other agents alone or other drug combinations.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

(1) Overall survival (OS) (2) Progression‐free survival (PFS)

Secondary outcomes

(1) QOL (2) Adverse effects (including adverse reactions of drugs, hospitalisation, death) (3) Symptom control, or overall response

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group (CGCRG) search strategy. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), (Issue 6, 2015); Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group (CGCRG) Specialised Register (Cochrane Library Issue 6, 2015); MEDLINE (January 1990 to 30 September 2015); EMBASE (January 1990 to 30 September 2015); The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) database (to 30 September 2015); CBM (Chinese Biomedical Database) (January 1990 to 30 September 2015).

A comprehensive and exhaustive search strategy was formulated in an attempt to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress), using the following terms in combination with the search strategy defined by the Cochrane Collaboration and detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions 5.1.0. (Higgins 2011).

We also searched World Health Organization International Clinical Trial Registration Platform for ongoing trials (http://www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/).

We identified additional studies by searching the reference lists of relevant trials and reviews identified searched electronically .

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (MA and WTX) searched the databases for published articles in the field and analysed the data.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MA and WTX) scanned the titles and abstracts from the initial search. The full texts of potentially relevant studies were then obtained for independent assessment of eligibility by both assessors. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third review author when necessary.

According to the empirical evidence (Jadad 1996; Juni 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995), we assessed the methodological quality as described by Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011):

Generation of allocation sequence: e.g. computer generated random numbers, coin tossed etc

Concealment of treatment allocation schedule: e.g, by telephone randomisation, or use of consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

Blinding of outcome assessment (for clinician, participant, and outcome assessor).

Whether loss to follow‐up was accounted for (no more than 20%); whether intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses (understood to mean that participants were analysed in the groups to which they were initially assigned, regardless of which treatment they actually received) was performed.

We recorded problems in respect of these issues in full, and for individual studies each criteria was assigned a label of 'adequate', 'unclear' or 'inadequate'. It is acknowledged that blinding in some trials may be difficult to assess and therefore we placed the main emphasis on other methodological quality criteria.

Based on these criteria, studies were broadly subdivided into the following three categories: Low risk of bias ‐ all quality criteria met Unclear risk of bias ‐ no information about the methodological issues, or quality criteria only partly met High risk of bias ‐ one or more criteria not met

Each trial was assessed independently by two review authors (MA and WTX). There were no disagreements recorded.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MA and WTX) independently extracted data using a pre‐designed data extraction form. Data were extracted on study characteristics including methods, study quality, participants, interventions, outcomes and duration of follow‐up. No disagreements were recorded.

Where possible we extracted data to allow an ITT analysis (the analysis should include all the participants in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned). For time to event data (overall and disease free survival) we planned to abstract the hazard ratio (HR) and its variance from trial reports; if these were not present, we attempted to abstract the data required to estimate them using Parmar's (Parmar 1998) methods e.g. number of events in each arm and log‐rank P‐value comparing the relevant outcomes in each arm, or relevant data from Kaplan‐Meier survival curves. If it was not possible to estimate the HR, we abstracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of participants assessed, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR). If the number randomised and the numbers analysed were inconsistent, we calculated the percentage loss‐to‐follow‐up and reported this information in the text. For other binary outcomes such as adverse events, we recorded the number of participants experiencing the event and the number of participants assessed in each group of the trial. For continuous outcomes, such as QOL, we extracted the arithmetic means and standard deviations for each group at the end of follow‐up. If the data were reported using geometric means we extracted standard deviations on the log scale. Medians and ranges were extracted and reported in tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

There were insufficient similar studies to perform meta‐analysis therefore we were unable to evaluate statistical heterogeneity. Results are presented as a narrative description only.

Data synthesis

We did not perform meta‐analysis, If more studies are included in future versions of this review we will pool data using the random effects method in RevMan 5.2.

For time‐to‐event data, we will pool HRs using the generic inverse variance facility of RevMan 5.2.

For any dichotomous outcomes, we will pool the RRs.

For continuous outcomes, we will pool the MDs between the treatment arms at the end of follow‐up if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale, otherwise we will to pool standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to perform subgroup analysis according to type of interventions (single agent versus combination agents) and type of EOC (primary versus recurrent), however this was not possible due to insufficient data.

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to conduct sensitivity analysis according to the risk of bias of included studies. This was not possible due to insufficent data. Sensitivity analysis may be possible In future updates of this review.

Results

Description of studies

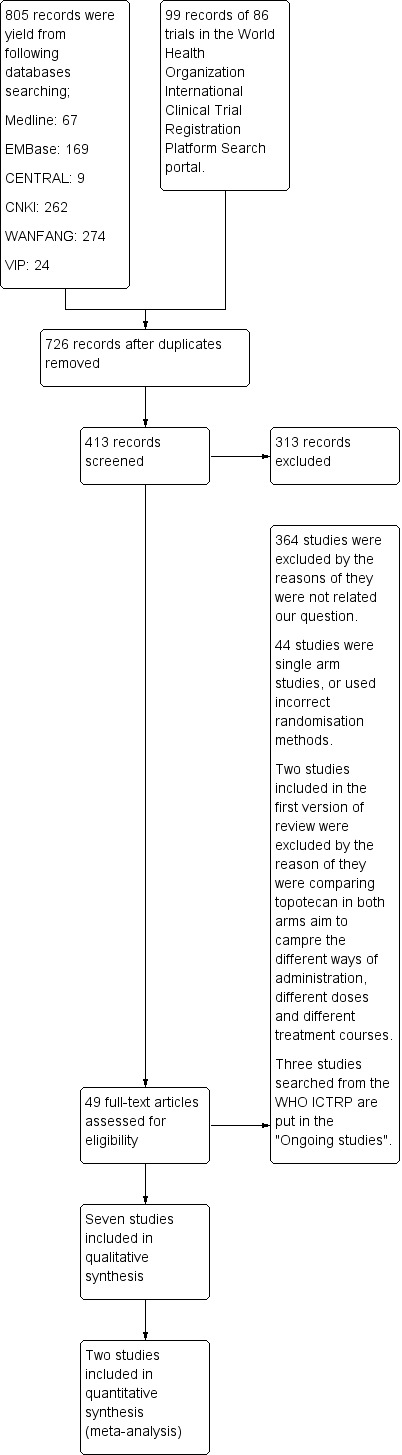

The initial search strategy yielded 805 records, of which 49 full‐text articles were retrieved for further eligibility assessment. 44 studies were excluded primarily due to duplicate, lack of control group, or incorrect methods of randomisation; other two studies (Gore 2002; Hoskins 1998) included in the first version of this review aimed to compare different ways of administration, or different doses of topotecan were also excluded (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table). Three ongoing studies were searched from WHO ICTRP (Rosalind G 2013; Song 2011; Xian‐Janssen 2013); Six studies were included in this review for qualitative or quantitative analysis (Bookman 2009; Downs 2008; Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004; Meier 2009; Placido 2004)(Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Design

All trials were multicentre, parallel arm RCTs. The sites included hospitals or healthcare centres in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Italy, United States, Canada and Germany.

Participants

A total of 5,640 participants aged from 18 years to 87 years were enrolled in the six trials. Participant numbered 75 (Downs 2008), 481 (Gordon 2004a), 225 (Huinink 2004), 274 (Meier 2009), 273 (Placido 2004) and 4312 (Bookman 2009), respectively. The Bookman 2009 and Placido 2004 trials were conducted in women with primary disease, the other studies were conducted in women with recurrent or persistant disease. Bookman 2009 involved participants with stage III/IV disease, while participants in Placido 2004 were mainly staged II/III (77%). One trial reported tumour grade (Huinink 2004) with participants having mainly grade 2/3 tumours. Performance status was reported in Gore 2001a and Huinink 2004 for most participants to be between 0 to 1.

One trial (Gordon 2004a) reported the absence or presence of bulky disease without specifying tumour size. One trial (Placido 2004) recruited participants mainly with a tumour size less than 1cm (66.3%). One trial (Huinink 2004) reported various percentages of participants with a tumour size larger than 5 cm. Of the seven included trials, platinum sensitivity to prior chemotherapy was mentioned in two trials (Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004). Two trials (Downs 2008; Placido 2004), reported the percentage of participants sensitive to platinum‐based chemotherapy and this varied from 40% to 46.9%, which was balanced between two intervention arms.

Interventions

Bookman 2009: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan was one of five regimens compared in this study in women with primary disease. Other triplet regimens incorporated gemcitabine or methoxypolyethylene glycosylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD). These triplet regimens were compared with standard treatment (carboplatin/paclitaxel doublet) (see Table 7). There were 702 participants in the topotecan arm and 687 participants in the standard treatment arm.

2. Table 2. Bookman 2009: Treatment plan.

| Variable | Treatment Arm | ||||

| I (Reference) | II | III | IV | V | |

| Carboplatin, C1-4 | AUC6 D1 | AUC5 D2 | AUC5 D1 | AUC5 D3 | AUC6 D8 |

| Paclitaxel, C1-4 | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gemcitabine, C1‐8 | ‐ | 800mg/m2 D1, 8(30 minutes) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gemcitabine, C1‐4 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1000mg/m2/d D1,8 |

| PLD, C1, 3, 5, 7 | ‐ | ‐ | 30mg/m2D1 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Topotecan, C1‐4 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1.25mg/m2/dD1,2,3 | ‐ |

| Carboplatin, C5‐8 | AUC6 D1 | AUC5 D1 | AUC5 D1 | AUC6 D1 | AUC6 D1 |

| Paclitaxel, C5‐8 | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) |

Each arm included eight cycles of triplet or sequential‐doublet chemotherapy, which provided a minimum of four cycles that incorporated experimental treatments while maintaining at least four cycles with carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Placido 2004: All participants received carboplatin (area under the curve of 5) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m²) on day 1 every 21 days for six cycles. After randomisation, women in the control arm received no further cytotoxic or non‐cytotoxic treatment until disease progression, whereas women in the experimental arm received topotecan 1.5 mg/m² on days 1 to 5, four cycles, every three weeks.

Downs 2008: Topotecan at a dose of 1.25 mg/m² was adminstered intravenously as a 30‐minute infusion for five consecutive days every 21 days plus oral thalidomide versus the topotecan infusion alone.

Gordon 2004a: Topotecan 1.5 mg/m²/d administered intravenously for five consecutive days every three weeks versus PLD 50 mg/m² as a one‐hour infusion every four weeks.

Huinink 2004: Topotecan (1.5mg/m²/d) administered intravenously for five days of 21‐day cycle versus paclitaxel (175mg/m²/d) administered over three hours of 21‐day cycle.

Meier 2009: Topotecan 1.5 mg/m²/d as a 30‐minute infusion for five consecutive days every 21 days versus treosulfan 7 g/m2 over 30 minutes every 21 days.

Outcomes

Overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) were reported in all studies but not consistently reported as time‐to‐event data.

Overall survival (OS) was reported in all included trials; progression free survival (PFS) was reported in all studies; QOL was reported in one study (Meier 2009); Time to progression was mentioned in three trials (Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004; Placido 2004); Adverse effects (toxicity) were reported in all trials except two (Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004). Two trials (Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004) conducted a three‐year and five‐year long‐term follow‐up, respectively.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation

All trials reported the total number of patients randomised. Randomisation in each trial was performed as follows:

Bookman 2009: Central randomisation with stratified block random assignment to balance treatment assignments within coordinating centres.

Downs 2008: Computer‐generated randomisation.

Huinink 2004: A central randomisation system was used but the precise method was not described.

Meier 2009: Central randomisation with stratification.

Placido 2004: Computer‐generated randomisation with minimisation

Gordon 2004a did not provide any details on how randomisation was performed.

Allocation concealment

Three studies (Bookman 2009; Huinink 2004; Meier 2009) used central randomisation and allocation was therefore considered to be adequate. The others did not describe allocation concealment.

Blinding

Gordon 2004a was reported as an open‐label study. Blinding was not reported in any of the other included trials.

Withdraw/drop‐out/loss to follow‐up/intention‐to‐treat

Gordon 2004a did not report the percentage of the participants that withdrew from or were lost to follow‐up in the trials; for the other trials the percentage of withdrawal ranged from 0% to 10.6%. ITT analysis was used in four trials (Bookman 2009; Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004; Placido 2004), one trial used both ITT and per‐protocol analyses (Placido 2004), another trial used per‐protocol analysis (Downs 2008).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings 1. Topotecon+Carboplatin+Paclitaxel compared to Carboplatin+Paclitaxel for ovarian cancer.

| Topotecon+Carboplatin+Paclitaxel compared to Carboplatin+Paclitaxel for ovarian cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with ovarian cancer Settings: Intervention: Topotecon+Carboplatin+Paclitaxel Comparison: Carboplatin+Paclitaxel | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Carboplatin+Paclitaxel | Topotecon+Carboplatin+Paclitaxel | |||||

| Overall Survival clinical observation Follow‐up: 3 years | Study population | HR 1.02 (0.97 to 1.06) | 1998 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 646 per 1000 | 654 per 1000 (635 to 668) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Progress free survival Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | HR 1.03 (1.03 to 1.03) |

1998 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1 Low |

||

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Substancial statistical heterogeneity existed in pooling analysis (I2 =92%).

Summary of findings 2. Topotecon compared to PLD for EOC.

| Topotecon compared to PLD for EOC | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with EOC Settings: Intervention: Topotecon Comparison: PLD | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| PLD | Topotecon | |||||

| Survival Hazard Ratio (platium‐sensitive) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | See comment | See comment | 220 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| Survival Hazard Ratio (Platium‐resistant) Follow‐up: 3 years | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.35 to 1.38) | 255 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 138 per 1000 | 96 per 1000 (48 to 191) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Progression free survival (platium‐sensitive) Follow‐up: median 5 years | See comment | See comment | 220 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| Progression free survival (platium‐resistant) Follow‐up: median 5 years | See comment | See comment | 220 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Lack of description about the randomisation method, allocation method and blinding. 2 The confidence interval is rather wide.

Summary of findings 3. Topotecon compared to paclitaxel for EOC.

| Topotecon compared to paclitaxel for EOC | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with EOC Settings: Intervention: Topotecon Comparison: paclitaxel | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Paclitaxel | Topotecon | |||||

| Survival Scale from: 1 to 226.3. Follow‐up: median 5 years | See comment | See comment | 226 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| Time to progression Scale from: 1 to 137.3. | See comment | See comment | 226 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Summary of findings 4. Topotecon compared to Topotecon+thalidomide for EOC.

| Topotecon compared to Topotecon+thalidomide for EOC | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with EOC Settings: Intervention: Topotecon Comparison: Topotecon+thalidomide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topotecon+thalidomide | Topotecon | |||||

| Progreesion free survival Follow‐up: mean 5 years | See comment | See comment | 73 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| Overall response Follow‐up: mean 5 years | Study population | RR 0.47 (0.23 to 0.99) | 75 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| 412 per 1000 | 194 per 1000 (95 to 408) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 ITT and PP analysis showed results showed inconsistance: ITT: RR=0.47, 95%CI 0.23 to 0.99; PP: RR=0.50, 95%CI 0.24 to 1.04

Summary of findings 5. Topotecan compared to treosulfan for EOC.

| Topotecan compared to treosulfan for EOC | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with EOC Settings: Intervention: Topotecan Comparison: treosulfan | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Treosulfan | Topotecan | |||||

| Overall survival | See comment | See comment | 274 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| Progression free survival | See comment | See comment | 274 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| Response to treatment | Study population | RR 1.76 (1.06 to 2.94) | 274 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 138 per 1000 | 242 per 1000 (146 to 405) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unclear risk on blinding

We conduct pooling analysis for two trials (Bookman 2009, Placido 2004) for overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS); descriptive analysis for remain four trials (Downs 2008, Gordon 2004a, Huinink 2004, Meier 2009) due to the data were not similar enough or not suite for combination.

Primary outcomes/overall survival

Topotecan plus standard treatment (carboplatin/paclitaxel) versus standard treatment in primary EOC

In study Bookman 2009, 702 participants in the standard treatment plus topotecan arm and 687 participants in the standard treatment arm (see Analysis 1.1). Two hundred and seventy three participants were analysed in study Placido 2004 (see Analysis 1.2). Pooling analysis of two trials shown that there was no statistically significant difference on overall survival (OS) when topotecan was added to the standard carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen compared with standard treatment alone (HR 1.02, 95%CI 0.99, 1.06)(see Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 1: Overall survival (Bookman 2009)

| Overall survival (Bookman 2009) | ||||||

| Study | Outcomes | CP (n=864) | CPG (n=864) | CPD (n=862) | CT‐CP (n=861) | CG‐CP (n=861) |

| Bookman 2009 | Proportion OS >3 years | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| No. | 426 | 424 | 425 | 413 | 395 | |

| Proportion OS >5 years | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.30 | |

| No. | 72 | 70 | 80 | 73 | 66 | |

| Median OS, months | 44.1 | 44.1 | 44.2 | 40.2 | 39.6 | |

| Adjusted HR OS | 1.00 | 1.006 | 0.952 | 1.051 | 1.114 | |

| 95%CI | 0.885 to 1.144 | 0.836 to 1.085 | 0.925 to 1.194 | 0.982 to 1.264 | ||

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 2: Overall survival (Placido 2004)

| Overall survival (Placido 2004) | ||

| Study | hazard ratio | 95% CI |

| Placido 2004 | 1.051 | 0.93 to 1.19 |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 3: Pool analysis of OS HR

Topotecan versus paclitaxel in recurrent EOC

Huinink 2004 (226 participants) compared topotecan with paclitaxel as salvage therapy in women with recurrent ovarian cancer found no significant differences between the two arms in terms of median survival time: at 4 years post‐randomisation, median survival in the topotecan group was 63.0 weeks (range <1 to 238.4+ weeks; 20.5% censored) and in paclitaxel group was 53.0 weeks (range <1 to 226.3+ weeks; 12.3% censored); P = 0.44.

A survival curve was presented in Huinink 2004 but no time‐to‐event data were available.

When survival data were stratified by platinum sensitivity, platinum‐resistant patients in the topotecan group, the Median survival time was 28.4 weeks; for early/interim relapse patients, 71.9 weeks; for late relapse patients, 63.4 weeks; in the paclitaxel group, median survival time for refractory patients was 39.7 weeks; for early/interim relapse patients, 35.0 weeks; for late relapse patients, 85.1 weeks.

Platinum‐sensitive participants (late relapse) in the topotecan group had median survival time of 63.4 weeks and 85.1 weeks in the paclitaxel group. See Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Topotecan versus paclitaxel, Outcome 1: Survival

| Survival | ||||

| Study | Topotecan group | Paclitaxel group | RR | P value |

| Survival (median/range by week) | ||||

| Huinink 2004 | 63.0 (range <1 to 238.4+ weeks; 20.5% censored) | 53.0 (range <1 to 226.3+ weeks; 12.3% censored) | 0.44 | |

| Long‐term median survival‐platium‐refractory (by week) | ||||

| Huinink 2004 | 28.4 | 39.7 | ||

| long‐term median survival‐platium‐early/interim relapse (by week) | ||||

| Huinink 2004 | 71.9 | 35.0 | ||

| Long‐term median survival‐platium‐late relapse(by week) | ||||

| Huinink 2004 | 63.4 | 85.1 | ||

Topotecan versus PLD for recurrent EOC

One trial (Gordon 2004a) was eligible for the comparison. Totally, participants treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) showed significant benefit on the term of median survival time than topotecan: 62.7 weeks in the PLD group and 59.7 weeks in the topotecan group (HR = 1.216, 95%CI 1.000 ‐ 1.478, P = 0.050). When the participants were divided to platinum‐sensitive group and platinum resistant group, a dramatic result appeared: PLD group had a significant longer median survival time than topotecan group, 107.9 weeks versus 70.1 weeks (HR = 1.432, 95%CI 1.066 ‐ 1.923; P = 0.017)(see Analysis 3.1); but in platinum resistant patients group, there was no significant difference (41.3 weeks in the topotecan group and 35.6 weeks in the PLD group; P = 0.455)(Analysis 3.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Topotecan versus PLD, Outcome 1: Hazard Ratio of Survival

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Topotecan versus PLD, Outcome 2: Survival

| Survival | |||

| Study | Topotecan group | PLD group | p value |

| Median survival (by week) | |||

| Gordon 2004a | 59.7 | 62.7 | |

| median survival‐platium‐sensitive(by week) | |||

| Gordon 2004a | 70.1 | 107.9 | |

| median survival‐platium‐resistant(by week) | |||

| Gordon 2004a | 41.3 | 35.6 | 0.455 |

Long‐term survival, which was also counted as the survival rate at the end of three‐year follow‐up, still favoured PLD; participants in the topotecan group were less likely to survive (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.99). When data were stratified by platinum sensitivity, in the platinum‐sensitive group, PLD had a slight advantage over topotecan (RR 0.6, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.01), no significant difference was found in the platinum‐resistant group (RR 0.69, 95%CI 0. 35 to 1.38)(see Analysis 3.2 and Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Topotecan versus PLD, Outcome 3: Survival

Topotecan versus topotecan/thalidomide in recurrent EOC

In Downs 2008, the median OS was 14.8 months (95% CI 13.2 to 28.0) for women who were receiving topotecan and 18.8 months (95% CI 13.9 to 33.1) for women who were receiving topotecan and thalidomide, there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.67).

Topotecan versus treosulfan in recurrent EOC

In Meier 2009, by the end of the observation period, 246 (89.8%) participants died. Median overall survival was significantly longer in participants treated by topotecan (55.0 weeks, 95% CI 50.0‐65.6) than by treosulfan (41.0 weeks, 95%CI 34.0‐58.4)(P = 0.0023).

For stratum 1 (platinum‐resistant) participants, there was no significant different between two groups, the median overall survival in topotecan was 48.7 week (95% CI 31.9‐54.4), and in treosulfan was 31.6 weeks (95% CI 27.4‐35.4), respectively (P = 0.1111).

For stratum 2 (platinum‐sensitive) participants with relapse after 6‐12 months, topotecan showed superior overall survival, median 69.1 weeks (95% CI 55.3‐88.7), than treosulfan, median 59.3 weeks (95% CI 41.0‐74.6)(P = 0.0068)(see Analysis 5.1)

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Topotecan versus treosulfan, Outcome 1: Overall survival

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Study | Groups | Median (weeks) | 95% CI | P value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Meier 2009 | Overall | Topotecan | 55.0 | 50.0 ‐ 65.6 | 0.0023 | 1.49 (95% CI 1.15 ‐ 1.93) |

| Treosulfan | 41.0 | 34.0 ‐ 58.4 | ||||

| Stratum 1 | Topotecan | 48.7 | 31.9 ‐ 54.4 | 0.1111 | ||

| (platinum‐resistant participants) | Treosulfan | 31.6 | 27.4 ‐ 35.4 | |||

| Stratum 2 | Topotecan | 69.1 | 55.3 ‐ 88.7 | 0.0068 | ||

| (platinum‐sensitive participants) | Treosulfan | 59.3 | 41.0 ‐ 74.6 | |||

Time to progression and progression free survival

Topotecan plus standard treatment versus standard treatment alone in primary EOC

One trial (Placido 2004) reported time to progression that was 18.2 months (73 weeks) in topotecan group and 28.4 months (114 weeks) in non‐treatment group, no P‐value was presented (see Analysis 1.4). This trial performing a multivariable analysis to calculate the HR of PFS, and a PFS curve was presented which was no significant difference in PFS curve (P = 0.83)(see Analysis 1.6).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 4: Time to progression (Placido 2004)

| Time to progression (Placido 2004) | ||

| Study | Topotecan group | Non‐treatment group |

| Median time to progression(by month) | ||

| Placido 2004 | 18.2 | 28.4 |

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 6: PFS (Placido 2004))

| PFS (Placido 2004)) | ||

| Study | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI |

| Placido 2004 | 1.18 | 0.86‐ 1.63 |

One trial (Bookman 2009) reported median PFS in two groups, 15.4 months and 16 months, respectively, there was no statistical significant (adjusted HR 1.066, 95%CI 0.958 to 1.186)(see Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 5: PFS (Bookman 2009)

| PFS (Bookman 2009) | ||||||

| Study | Outcome | CP (n=864) | CPG (n=862) | CPD (n=862) | CT‐CP (n=861) | CG‐CP (n=861) |

| Bookman 2009 | Proportion PFS >1 year | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.67 |

| Proportion PFS >2 year | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.31 | |

| Median PFS, months | 16.0 | 16.3 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 15.4 | |

| Adjusted HR PFS | 1.00 | 1.028 | 0.984 | 1.066 | 1.037 | |

| 95%CI | 0.924 to 1.143 | 0.884 to 1.095 | 0.958 to 1.186 | 0.932 to 1.153 | ||

Pooling analysis of two trials (Bookman 2009, Placido 2004) shown that there was no statistically significant difference on PFS between topotecan plus standard carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen versus standard treatment alone (HR 1.04, 95%CI 1.03, 1.05)(see Analysis 1.7.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 7: Pool analysis of PFS HR

Topotecan versus paclitaxel in recurrent EOC

One trial with 226 participants (Huinink 2004) reported a trend in favour of topotecan as median time to progression of this group was 18.9 weeks (ranging from <1 to 92.6 weeks) compared with 14.7 weeks (ranging from 0.1 to 137.3 weeks; 12.3% censored) for the paclitaxel group. (P = 0.076)

Topotecan versus PLD in recurrent EOC

One trial (Gordon 2004a) was eligible for the comparison. No significant difference was found between the two regimens, participants in the topotecan group had 16.1 weeks of PFS and 17 weeks in the PLD group (P = 0.095). When data were stratified by platinum sensitivity, survival data in the platinum‐sensitive group showed a trend in favour of PLD (28.9 weeks compared with 23.3 weeks in participants receiving topotecan; P = 0.037), participants resistant to platinum‐based chemotherapy had a PFS of 9.1 weeks in the topotecan group and 13.6 weeks in the PLD group (P = 0.733), when the data were stratified by bulky disease, no difference was found. A PFS curve was present in the trial (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Topotecan versus PLD, Outcome 4: progression free survival

| progression free survival | ||||

| Study | topotecan | PLD | RR | P value |

| progression free survival | ||||

| Gordon 2004a | 16.1 | 17.0 | not given | 0.095 |

| progression free survival(platium‐sensitive) | ||||

| Gordon 2004a | 23.3 | 28.9 | not given | 0.037 |

| progression free survival(platium‐resistant) | ||||

| Gordon 2004a | 13.6 | 9.1 | not given | 0.733 |

Topotecan versus topotecan/thalidomide in recurrent EOC

In Downs 2008, progression‐free survival was estimated by Kaplan‐Meier estimates. All patients were followed to disease progression, and there were no censored events. The median PFS for women who were receiving topotecan was 4 months (95% CI, 2.9 to 5.1 months) compared with 6 months (95% CI, 4.2 to 7.7 months) for women who were receiving topotecan with thalidomide, there was statistically significant difference (P = 0.02)(Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Topotecan versus Topotecan/thalidomide, Outcome 1: Progression free survival

| Progression free survival | ||||

| Study | Group | Median (month) | 95% CI | P value |

| Downs 2008 | Topotecan | 4 | 2.9 to 5.1 | |

| Topotecan with thalidomide | 6 | 4.2 to 7.7 | 0.02 | |

Topotecan versus treosulfan in recurrent EOC

In Meier 2009, progression‐free survival for topotecan was 23.1 weeks (95% CI 19.9‐27.7), compared to 12.7 weeks (95% CI 9.9‐17.7) for treosulfan, there was statistically significant difference (P = 0.0020)(Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Topotecan versus treosulfan, Outcome 2: Progression‐free survival

| Progression‐free survival | ||||||

| Study | Groups (N =, E = ) | Median (weeks) | 95% CI | P value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Meier 2009 | Stratum 1 | Topotecan (N = 136, E = 127) | 18.1 | 12.7 ‐ 21.0 | 0.0476 | 1.43 (95% CI 1.12 ‐ 1.83) |

| Treosulfan (N = 138, E = 135) | 9.4 | 8.9 ‐ 11.0 | ||||

| Stratum 2 | Topotecan (N = 136, E = 127) | 28.9 | 26.1 ‐ 33.6 | 0.0163 | 1.44 (95% CI 1.00 ‐ 2.07) | |

| Treosulfan (N = 138, E = 135) | 21.4 | 15.0 ‐ 25.3 | ||||

For stratum 1 (platinum‐resistant) participants, topotecan group showed significantly longer progression‐free survival than treosulfan (median 18.1 weeks, 95% CI 12.7‐21.0 for topotecan, and median 9.4 weeks, 95% CI 8.9‐11.0 for treosulfan, P = 0.0476, respectively; Hazard ratio = 1.44, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.07).

For stratum 2 (platinum‐sensitive) participants with relapse after 6‐12 months, topotecan showed significantly longer progression‐free survival than treosulfan (median 28.9 weeks, 95% CI 26.1‐33.6, and median 21.4 weeks, 95% CI 15.0‐25.3, P = 0.0163; Hazard ratio = 1.43, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.83)(Analysis 5.2).

Secondary outcomes/QOL

Topotecan versus PLD

Only one trial (Gordon 2004a) reported the results of health‐related QOL and no significant differences were found between the arms in any of the measured scores. HQL questionnaire was used at baseline and after treatment to compare QOL.

Topotecan versus treosulfan

In Meier 2009, the data set available for meaningful quality of life analysis showed a substantial drop‐out rate, finally, 107 (78.7%) participants receiving topotecan and 104 (75.4%) treosulfan qualifies for quality of life analysis. There was no differences between the two groups on the quality of life.

Adverse effects

Topotecan versus paclitaxel

Participants in the topotecan group had a significantly higher frequency of haematological adverse events except for overall anemia incidence, pooled analysis revealed that RRs of all other hematological adverse events (overall neutropenia; grade 3/4 neutropenia; overall thrombocytopenia; grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia; grade 3/4 anemia, grade 3/4 leukopenia) ranged from 1.18 to 17.74 and all with 95% CIs revealing that topotecan is more likely than paclitaxel to induce hematological toxicity. There was no evidence of gross statistical heterogeneity in the trial Huinink 2004 (chi‐square (8) was 0.13, 0.03, 0.56, p = 0.72, 0.86, 0.45 respectively) reporting data of grade 3/4 neutropenia, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, grade 3/4 anemia that could be pooled. Incidences of nausea,vomiting and fatigue were less likely to occur in paclitaxel group (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.16; RR 1.82,95% CI 1.41 to 2.35;RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.95 respectively), while patients in the topotecan group were less likely to report alopecia, arthralgia, paresthesia, skeletal pain, flushing, neuropathy etc. based on the results of meta‐analysis (see RRs in analyses)(Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Topotecan versus paclitaxel, Outcome 3: Toxicity

Topotecan versus PLD

Topotecan was associated with significant haematological toxicity compared with PLD including more overall leukopenia, grade 3/4 leukopenia, overall neutropenia, grade 3/4 neutropenia, overall thrombocytopenia, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, overall anemia, grade 3/4 anemia(see Analysis 3.5). Topotecan resulted in a higher rate of alopecia compared with PLD (RR 3.05 CI, 95% 2.22 to 4.20). PPE and stomatitis occurred less in the topotecan group (RR 0.02; 95% CI 0.00 to 0.07, RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.53, respectively)(Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Topotecan versus PLD, Outcome 5: Toxicity

Topotecan versus non‐treatment

The incidence of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia of all grades were significantly lower than the counterparts of other trials using identical topotecan regimens. Similar trends were found for non‐hematological toxicity, which could be partially explained by the characteristics of enrolled patients (The trial recruited stage IC to IV patients and the majority had a complete response to platinum‐based chemotherapy) (Placido 2004). WHO criteria were used for toxicity evaluation while NCI criteria was used in other trials included in this review (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Topotecan versus paclitaxel, Outcome 4: Symptom control(response)

Topotecan versus topotecan/thalidomide

Downs 2008 reported all hematologic and non‐hematologic toxicities, grade 3 or 4 toxicities experienced by >20% of patients in either arm were considered hematologic toxicities. Of the toxicities, grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia was observed with greater frequency in women who were receiving thalidomide than topotecan alone, none of the episodes of thrombocytopenia resulted in dose reductions or dose delays; the rates of other hematologic toxicities were similar. Fatigue and somnolence were experienced at similar rates in the control and experimental arms. Lightheadedness or dizzy feelings, neurotoxicity, and syncope were experienced in 10% of women in the control arm and 33% of women in the thalidomide arm, and the most frequent was grade 1 or 2 lightheadedness. In topotecan arm, the rate of 51% (20/39) women were observed had grade 1 or 2 constitutional toxicity, while in topotecan and thalidomide group was 60% (18/30); 2 women on each arm had grade 3 or 4 constitutional toxicity. The incidence of constipation and gastrointestinal toxicity was similar between the arms.

Other problem by receiving thalidomide may be toward increased incidence of peripheral neuropathy and rash. One participant on the topotecan and thalidomide arm was diagnosed with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in her third cycle of chemotherapy and was observed had disease progression, and she was removed from the protocol (Analysis 4.2, Analysis 4.3, Analysis 4.4).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Topotecan versus Topotecan/thalidomide, Outcome 2: Toxicity(1)

| Toxicity(1) | |||||

| Study | Toxicity | TopotecanGrade 1, 2 n(%) | TopotecanGrade 3, 4 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 1, 2 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 3, 4 n(%) |

| Downs 2008 | Neutropenia | 3(8) | 28(72) | 1(3) | 26(87) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 14(36) | 14(36) | 19(63) | 6(20) | |

| Anemia | 20(51) | 9(23) | 21(70) | 4(13) | |

| Auditory/hearing | 0 | 0 | 3(10) | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular | 0 | 0 | 2(7) | 0 | |

| Constitutional | 20(51) | 2(5) | 18(60) | 2(7) | |

| Dermatology | 6(15) | 0 | 5(17) | 1(3) | |

| Endocrine | 2(5) | 0 | 1(3) | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 15(38) | 4(10) | 12(40) | 1(3) | |

| Genitourinary | 2(5) | 1(3) | 0 | 0 | |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Topotecan versus Topotecan/thalidomide, Outcome 3: Toxicity(2)

| Toxicity(2) | |||||

| Study | Toxicity | TopotecanGrade 1, 2 n(%) | TopotecanGrade 3, 4 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 1, 2 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 3, 4 n(%) |

| Downs 2008 | Hemorrhage | 1(3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 0 | 3(8) | 2(7) | 2(7) | |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 4(10) | 0 | 2(7) | |

| Lymphatics | 1(3) | 0 | 1(3) | 0 | |

| Metabolic | 1(3) | 1(3) | 1(3) | 0 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 3(8) | 0 | 3(10) | 0 | |

| Neurologic | 4(10) | 0 | 7(23) | 4(13) | |

| Peripheral neurophathy | 2(5) | 0 | 4(13) | 0 | |

| Ocular/visual | 2(5) | 0 | 2(7) | 1(3) | |

| Pain | 8(21) | 2(5) | 8(27) | 0 | |

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Topotecan versus Topotecan/thalidomide, Outcome 4: Toxicity(3)

| Toxicity(3) | |||||

| Study | Toxicity | TopotecanGrade 1, 2 n(%) | TopotecanGrade 3, 4 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 1, 2 n(%) | Topotecan/thalidomideGrade 3, 4 n(%) |

| Downs 2008 | Pulmonary | 4(10) | 2(5) | 4(13) | 3(10) |

| Thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(3) | |

Topotecan versus treosulfan

In Meier 2009, overall hematologic toxicity in the topotecan arm was non‐cumulative and well manageable, in the treosulfan treatment group hematologic toxicity was not cumulative, too. The only hematologic toxicity showing a non balanced distribution was alopecia. This relevant toxicity occur significantly more often in the topotecan arm (50% versus 12.2%). Non‐hematological toxicity was generally mild for both groups.

Symptom control / overall response

The information of age, stage, tumour grade, severity status of conditions, residual tumour bulk, histology were provided in most trials however given the different interventions of different trials, few could be pooled. One trial (Gordon 2004a) stratified patients by bulky disease, yet, no significant difference was found in any outcome parameter. Huinink 2004 reported that participants with smaller tumour size were more likely to respond topotecan (RR 3.11, 95% CI 1.34 to 7.14). Platinum‐sensitive participants were more likely to respond to any intervention arm: overall response rate, irrespective of agents given, ranged from 19.0% to 35.7% in platinum‐sensitive participants and from 6.78% to 13.3% of platinum‐resistant participants. Survival time was also significantly longer in platinum‐sensitive participants (with median survival time ranging from 63.4 to 107.9 weeks with any intervention) than in the platinum‐resistant group (median survival time ranged from 28.4 to 71.9 weeks in any intervention arm) irrespective of the interventions given (Gordon 2004a; Gore 2001a; Huinink 2004). The analysis of PFS in one trial (Gordon 2004a) yielded similar results:the platinum‐sensitive participants had a median survival time ranging from 23.3 weeks to 28.9 weeks with any intervention,while the platinum‐resistant patients had median survival time ranging from 9.1 weeks to 13.6 weeks.

Downs 2008 reported overall response rate in participants administrated topotecan along was 21% (8/39), and 49% (14/30) in topotecan plus thalidomide, which showed combination use of topotecan and thalidomide significantly superior than topotecan alone (P = 0.0039)(see Analysis 4.5).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Topotecan versus Topotecan/thalidomide, Outcome 5: Response to treatment

| Response to treatment | |||

| Study | Response | Topotecan, n=39 | Topotecan/Thalidomide, n=30 |

| Downs 2008 | Complete response | 7(18) | 9(30) |

| Partial response | 1(3) | 5(17) | |

| Overall response* | 8(21) | 14(47) (* P = 0.036) | |

| Stable disease | 5(17) | ||

| Progressive disease | 24(62) | 9(30) | |

| Not evaluated | 2(5) | 2(7) | |

Meier 2009 reported overall response rate that was 27.5% for topotecan and 16.0% for treosulfan (P = 0.0307)(see Analysis 5.3).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Topotecan versus treosulfan, Outcome 3: Response to treatment

| Response to treatment | |||||||||

| Study | Response | Topotecan |

Overall N (%) |

Platinum resistant N (%) |

Platinum sensitive N (%) |

Treosulfan |

Overall N (%) |

Platinum resistant N (%) |

Platinum sensitive N (%) |

| Meier 2009 | n = | 120 | 57 | 63 | 119 | 57 | 62 | ||

| CR | 6 (5.0) | 2 (3.5) | 4 (6.3) | 7 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (11.3) | |||

| PR | 27 (22.5) | 9 (15.8) | 18 (28.6) | 12 (10.1) | 4 (7.0) | 8 (12.9) | |||

| NC | 37 (30.8) | 14 (24.6) | 23 (36.5) | 25 (21.0) | 10 (17.6) | 15 (24.2) | |||

| PD | 35 (29.2) | 26 (45.6) | 9 (14.3) | 56 (47.1) | 32 (56.1) | 24 (38.7) | |||

| Not assessable | 15 (12.5) | 6 (10.5) | 9 (14.3) | 19 (16.0) | 11 (19.3) | 8 (12.9) | |||

| CR + PR* (P = 0.0307) | 33 (27.5) | 11 (19.3) | 22 (34.9) | 19 (16.0) | 4 (7.0) | 15 (24.2) | |||

Discussion

Summary of main results

Six studies including 5640 participants were eligible for this review. We were able to pooling data from Bookman 2009 in which only topotecan and standard arms data were used, and Placido 2004. We did not pool data from other studies due to every study compared different regimes with topotecan, or insufficient similar data, respectively.

Overall, the effect of topotecan on overall survival and PFS did not substantially differ from other agents, except in subgroup of participants with platinum‐sensitive ovarian cancer in which PLD had significantly better HR for OS than topotecan (Gordon 2004a).

Present results for primary treatment and secondary treatment separately (regimens are different). Summarise the results, e.g. Results show that adding topotecan to standard platinum‐based chemotherapy for primary ovarian cancer does not improve survival and is associated with significantly more severe adverse effects. When used as single‐agent treatment for recurrent disease, topotecan resulted in similar PFS to paclitaxel and PLD single‐agent treatment, but overall survival was better with PLD, particularly for the platinum‐sensitive subgroup (Gordon 2004a). Topotecan is associated with more severe adverse effects than the other paclitaxel and PLD, particularly haematological adverse effects.

The median overall survival of ovarian cancer participants treated by topotecan were various from 39.6 t0 63 weeks, no significant difference was found in comparing with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD)(Bookman 2009; Gordon 2004a), paclitaxel (Bookman 2009; Huinink 2004), topotecan plus thalidomide (Downs 2008), respectively; but significantly superior than treosulfan (Meier 2009).

The progression‐free survival (PFS) in the participants treated by topotecan was 16 to 23 weeks, similar as those participants treated by PLD (Bookman 2009; Gordon 2004a); more effectively delayed disease progression than paclitaxe (Huinink 2004), and than treosulfan (Meier 2009), but the PFS significantly shorter than combine use topotecan with thalidomide (Downs 2008).

Topotecan was more hematologically toxic compared with paclitaxel, PLD, treosulfan, relative risks (RRs) of hematological events ranged from 1.03 to 14.46 and 1.73 to 27.12, or incidence were 50% versus 12.2%, respectively. Small tumour diameter, sensitivity to platinum‐based chemotherapy was associated with better prognosis. It should be noted that Placido 2004 reported less adverse events than other five trials, which could be explained by the recruitment of FIGO IC to IV patients and the majority of participants had complete response to platinum‐based chemotherapy plus the fact that WHO criteria were used for toxicity evaluation while NCI criteria was used in other three trials included of this review (Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004). The present evidence failed to prove whether topotecan could improve QOL of patients with ovarian cancer to a greater extent than the other agents.

Placido 2004 found that consolidation treatment by topotecan given at full dose for four cycles after surgery and first‐line chemotherapy with carboplatin plus paclitaxel for patients with advanced ovarian cancer who achieve a complete response does not prolong the PFS and the median overall survival, compared to no consolidation treatment, the P=0.31, HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.23 (PFS) and P=0.30 (OS), respectively.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

One (Downs 2008) of included studies was phase II trial, other five were phase III trials (Bookman 2009; Gordon 2004a; Huinink 2004; Meier 2009; Placido 2004). Lack of post‐market trials may impact the representativeness of the results. By the way, only one study in each comparison may also impact the representativeness, too. These may become a source of the reasons cause inconsistence outcome when topotecan to be used in clinical practice in different ovarian cancer populations.

In clinical practice, topotecan is used as an established, efficacious agent for recurrent ovarian cancer, especially for patients who had responded poorly to first‐line platinum‐based chemotherapy (Swisher 1997). It remains one of the single agents considered effective as a combination chemotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer especially for well‐defined categories of patients (Sessa 2005). The established daily‐times‐five arm of a 21‐day cycle is stable in term of efficacy (overall response rate) across the trials included in this review (ranging from 13.1% to 22.6%), and toxicity is generally tolerated and non‐cumulative. QOL and symptom palliation should be considered when selecting chemotherapy for patients with late stage ovarian cancer. A continuous 21‐day infusion of topotecan reportedly led to a response rate of 10.5% and 43% in two separate trials (Hochster 1996; Johnson 1997). Lastly, the adjunctive role of topotecan as first‐line therapy needs additional investigation on the basis of studied published (Guppy 2004; Hochster 2006; Mirchandani 2005; Tiersten 2006), all these innovative therapies should be translated into a well‐designed, large‐sampled RCTs.

Quality of the evidence

Due to the included studies were of pre‐market studies which were conducted with the Good Clinical Practice guideline, the quality of methodology totally high. Three studies with lower risk of bias, remain four studies unclear due to poor reporting of the methodology. Insufficient evidence, unclear risk of bias of individual studies, lack of consistent reporting of data, no post‐market studies, therefore evidence quality ranged from low, moderate and high (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5).

Potential biases in the review process

Our review had drawbacks in several aspects, first, our search was mainly restricted to trials published in English, good‐quality articles in other language may be omitted and thus undermine the validity of the findings in this review. We extracted data from the published articles without further contact with the authors to get access to raw data which could be more readily interpreted into informative conclusions. Our strategy, which did not find grey literature (unpublished trials, or confidential reports) may make this systematic review susceptible to publication bias. Considering the large number of trials other than RCTs studying topotecan at present, the inclusion of observational studies or non‐controlled trials in other forms of systematic review might aid readers to get a more comprehensive view of this topic.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review (Edwards 2015) which included a same trial Gordon 2004a reported a same result that in the non‐platinum‐based treatments, PLD monotherapy and trabectedin plus PLD significantly superior than topotecan monotherapy on OS, but PFS not.

This updated review does not changed the results of original version of the review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

While topotecan is used frequently for the treatment of recurrent and advanced ovarian cancer, data from RCTs were inadequate to find possible differences in effectiveness and safety when compared with other agents. The present evidence implies that topotecan, as with other second line chemotherapeutic agents is an effective agent in the treatment of ovarian cancer. No evidence support the consolidation treatment with topotecan given at full dose for four cycles for patients who achieved a complete response after surgery and first‐line chemotherapy with carboplatin plus paclitaxel.

Implications for research.

Larger RCTs comparing topotecan of established regimen (Berek 2000) with other agents of different regimens are urgently required to further evaluate whether the effectiveness of topotecan is similar to or superior than other second‐line agents, whether in single or combined use; or when combined with platinum‐based treatments. Different routes, doses and schedules should be evaluated in these trials. Likewise, they should use standardised outcomes for reporting dichotomous, continuous and survival data with variability and informative statistical illustrations. The time of follow‐up should be specified. The reporting of the trials should following CONSORT guidelines (Moher 2010; Schulz 2010).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 July 2020 | Review declared as stable | Intervention not used frequently in UK. No update planned. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2006 Review first published: Issue 2, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 June 2016 | New search has been performed | This updated review included three new trials (Bookman 2009, Downs 2008, Meier 2009), and excluded two phase II studies which were included in the previous version (Gore 2002, Hoskins 1998). The latter were excluded asthey did not match the inclusion criteria (assessed the different doses and administration schedules of topotecan). |

| 6 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 February 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Our thanks are given to Gail Quinn, Dr C Williams, and all members of The Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group. Thanks also to Kathie Godfrey, N Johnson, J Kavanagh, and H Dickinson, peer reviewers, for their help and comments to write and amend the review.

We also thank Dr. Peng LH, Chen XY contributed to the primary version of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

The following search terms were used, the strategy below was adapted appropriately for use in different electronic bibliographic databases. 1.randomized controlled trial.pt. 2.controlled clinical trial.pt. 3.randomized controlled trials.sh. 4.random allocation.sh. 5.double blind method.sh. 6.single blind method.sh. 7.or/1‐6 8.(animal not human).sh. 9.7 not 8 10.clinical trial.pt. 11.exp clinical trials/ 12.(clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab,sh. 13.(singl$ or double$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$).ti,ab,sh. 14.placebo$ 15.placebos.ti,ab,sh. 16.random$ ti,ab,sh. 17.research design.sh. 18.or/10‐17 19.18 not 8 20.19 not 9 21.comparative study.sh. 22.exp evaluation studies/ 23.follow up studies.sh. 24.prospective studies.sh. 25.(control$ or prospectiv$).mp or volunteer$.ti,ab. 26.or/21‐25 27.26 not 8 28.27 not (9 or 20) 29.9 or 20 or 28 30.genital neoplasms, female/ or ovarian neoplasms/ 31.ovari$ or ovary.ti,ab. 32.cancer$ or carcino$ or tumour$ or tumor$ or neoplas$ or malig$ 33.exp Carcinoma/ 34.32 or 33 35.31 and 34 36.30 or 35 37. topotecan or Hycamtin 38. explode "Topotecan"/ all subheadings 39. 37 or 38 40.36 and 39 and 29

Search strategy in Chinese databases:

1. 拓扑替康

2. 卵巢癌

3. 1 AND 2

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Overall survival (Bookman 2009) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.2 Overall survival (Placido 2004) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.3 Pool analysis of OS HR | 2 | Hazard Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.99, 1.06] | |

| 1.4 Time to progression (Placido 2004) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.4.1 Median time to progression(by month) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.5 PFS (Bookman 2009) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.6 PFS (Placido 2004)) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.7 Pool analysis of PFS HR | 2 | Hazard Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [1.03, 1.03] | |

| 1.8 toxicity (Placido 2004) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.8.1 leukopenia‐overall | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 189.62 [11.89, 3022.93] |

| 1.8.2 leukopenia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 80.41 [4.99, 1294.66] |

| 1.8.3 neutropenia‐overall | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 179.69 [11.27, 2865.82] |

| 1.8.4 neutropenia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 130.05 [8.13, 2080.23] |

| 1.8.5 thrombocytopenia‐overall | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 134.02 [8.38, 2143.07] |

| 1.8.6 thrombocytopenia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 52.62 [3.24, 854.79] |

| 1.8.7 anemia‐overall | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 157.85 [9.89, 2520.16] |

| 1.8.8 anemia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.85 [1.23, 352.28] |

| 1.8.9 fever | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 12.91 [0.73, 226.87] |

| 1.8.10 nausea/vomitting | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 110.20 [6.88, 1766.00] |

| 1.8.11 diarrhea | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 22.83 [1.36, 383.66] |

| 1.8.12 mucositis | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.85 [1.23, 352.28] |

| 1.8.13 cutaneous | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.98 [0.12, 72.47] |

| 1.8.14 liver | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.85 [1.23, 352.28] |

| 1.8.15 cystitis | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.95 [0.36, 133.27] |

| 1.8.16 peripheral neurophathy | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 40.70 [2.49, 666.29] |

| 1.8.17 hypersensitivity | 1 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.96 [0.24, 102.44] |

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Carboplatin/paclitaxel/topotecan versus Carboplatin/paclitaxel, Outcome 8: toxicity (Placido 2004)

Comparison 2. Topotecan versus paclitaxel.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Survival | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.1.1 Survival (median/range by week) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.1.2 Long‐term median survival‐platium‐refractory (by week) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.1.3 long‐term median survival‐platium‐early/interim relapse (by week) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.1.4 Long‐term median survival‐platium‐late relapse(by week) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.2 Time to progression | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.2.1 Time to progression (median/range by week) | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 2.3 Toxicity | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.3.1 neutropenia(overall) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 2.3.2 neutropenia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.83 [1.52, 2.20] |

| 2.3.3 thrombocytopenia(overall) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 2.3.4 thrombocytopenia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.66 [6.01, 57.91] |

| 2.3.5 anemia‐overall | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 2.3.6 anemia‐grade 3/4 | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.54 [3.08, 13.89] |

| 2.3.7 nausea | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [1.38, 2.18] |

| 2.3.8 vomiting | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.06 [1.51, 2.81] |

| 2.3.9 diarrhea | 1 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.75, 1.44] |