Abstract

The development of hydrogels for protein delivery requires protein–hydrogel interactions that cause minimal disruption of the protein’s biological activity. Biological activity can be influenced by factors such as orientational accessibility for receptor binding and conformational changes, and these factors can be influenced by the hydrogel surface chemistry. (Hydroxyethyl)methacrylate (HEMA) hydrogels are of interest as drug delivery vehicles for keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) which is known to promote re-epithelialization in wound healing. The authors report here the surface characterization of three different HEMA hydrogel copolymers and their effects on the orientation and conformation of surface-bound KGF. In this work, they characterize two copolymers in addition to HEMA alone and report how protein orientation and conformation is affected. The first copolymer incorporates methyl methacrylate (MMA), which is known to promote the adsorption of protein to its surface due to its hydrophobicity. The second copolymer incorporates methacrylic acid (MAA), which is known to promote the diffusion of protein into its surface due to its hydrophilicity. They find that KGF at the surface of the HEMA/MMA copolymer appears to be more orientationally accessible and conformationally active than KGF at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer. They also report that KGF at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer becomes conformationally unfolded, likely due to hydrogen bonding. KGF at the surface of these copolymers can be differentiated by Fourier-transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry in conjunction with principal component analysis. The differences in KGF orientation and conformation between these copolymers may result in different biological responses in future cell-based experiments.

I. INTRODUCTION

The development of hydrogels as clinically translatable protein delivery devices involves engineering a delicate balance of efficient, localized, and controlled protein release, while retaining the native conformation and orientation of protein in order for it to perform its biological function. (Hydroxyethyl)methacrylate (HEMA) hydrogels have been of interest for several decades as drug delivery vehicles since adsorption and diffusion of biomolecules into their porous network structure was observed in contact lens research, and due to their water content properties similar to those of biological tissues.1,2 While the development of HEMA or alternative hydrogel-based small molecule delivery has been extensively studied given the ease of diffusion into the hydrogel porous network, protein delivery poses more complex issues.3 We aim to design a hydrogel that maintains the native conformation of the protein and presents the protein in an orientation allowing for binding to its target cell surface receptors.

Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, is of interest in the treatment of chronic and traumatic wounds.4–6 Hydrogels for biomaterial-based delivery allow for localized, controlled, and extended delivery.7–11 Upon traumatic injury, the epithelium initiates an intraepithelial repair process which involves the expression of mitogenic and motogenic proteins such as KGF.11 Prior work from our labs and other labs has shown that exogenous addition of KGF in in vitro and in vivo wound models can expedite the wound closure process.4,8,12

Binding of KGF to the KGF receptor, which is a cell surface signal transducing receptor of the tyrosine kinase family, occurs during the re-epithelialization process.13 This binding event leads to cell division and migration of epithelial cells to the wound site and aids the wound healing process. KGF binding to the KGF receptor is mediated by KGF binding to glycosaminoglycans on the cell surface such as heparan sulfate and heparin prior to receptor binding. This eventually results in the formation of a KGF-heparin/heparan sulfate-KGF receptor complex.13–16 Therefore, the heparin/heparan sulfate binding ability of KGF is an initial indicator of its biological activity, and KGF must retain its native conformation and orientation in order to carry out this role.13 KGF binding to heparin/heparan sulfate is mediated by electrostatic interactions due to the presence of sulfate groups.13 We hypothesize that this interaction can be mimicked through electrostatic interactions with the hydroxyl groups of HEMA. By copolymerizing HEMA with molecules that adjust surface electrostatics, we aim to identify effects on KGF orientation and conformation. Introduction of these molecules is also known to affect adsorption and diffusion mechanisms at the surface.17,18

Protein adsorption on biomaterial surfaces has been viewed as an issue to understand and prevent; certain materials of interest as biomedical implants have been shown to cause adsorption of common blood proteins.19 These blood proteins such as serum albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor adsorb in orientations that allow for binding to cell surface receptors which leads to the activation of pathways involved in clotting and potential thrombus formation.19–33 While the activation of thrombus formation by blood proteins due to adsorption onto implant surfaces is not ideal and potentially catastrophic, we want to promote KGF orientations at our hydrogel surface that are able to bind heparin/heparan sulfate and the KGF cell surface receptor. However, surfaces of interest as implants such as polystyrene, polycarbonate, titanium, polymethyl methacrylate, etc. rarely possess characteristics of a drug delivery device such as the ability to load proteins into a material, and release and deliver proteins over time. It is possible that a copolymer of a material promoting adsorption with HEMA, such as HEMA with methyl methacrylate (HEMA/MMA), may lead to a receptor accessible orientation of KGF at the surface.

Hydrophilicity of HEMA hydrogels promotes diffusion of water and solutes into the porous network. Carboxylic acid-containing monomers such as methacrylic acid (MAA) have been reported to increase hydrophilicity.34–38 A HEMA/MAA copolymer may promote increased diffusion of KGF and potentially increase the concentration of KGF at the hydrogel surface. However, this may be negated by stronger electrostatic interactions between KGF and the copolymer, which could lead to potential unfolding of KGF at the hydrogel surface, resulting in KGF unable to bind its receptor.

Our approach to the development and evaluation of HEMA copolymers that will be designed to deliver biologically active protein involves the incorporation of (1) MMA, which is known to promote protein adsorption, and (2) MAA, which promotes increased protein diffusion.39 For the reasons we have argued above, MMA and MAA containing HEMA hydrogels were also extensively studied in contact lens applications in studies on preventing protein adsorption.40–43 We have chosen to incorporate concentrations of MMA and MAA into the copolymers that are known to limit changes to the viscoelastic properties of the copolymers and result in hydrogels suitable for delivery to tissues.39 Our efforts in understanding the effects of these varied copolymer surfaces on KGF orientation and conformation utilize Fourier-transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR) spectroscopy and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) in conjunction with principal component analysis (PCA).

Vibrational spectroscopic techniques such as FTIR-ATR spectroscopy and sum frequency vibrational generation spectroscopy have been utilized in studying dynamic changes in the protein secondary structure.44–49 FTIR-ATR spectroscopy is our method of choice in this study due to the presence of characterized spectra of proteins homologous to KGF from the FGF family.50 Previous work by Byler et al. on the amide I region (1600–1700 cm−1) of the FTIR-ATR spectrum of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) deduced the secondary structures indicated by peaks in the spectrum through comparisons with the x-ray crystallographic structure.52 KGF and bFGF share 40% homology, and both are growth factors containing five extended strands with reverse turns, disordered/irregular regions, a receptor binding loop, and a sixth disordered extended strand.50 Therefore, peak assignments of bFGF secondary structures in the FTIR-ATR spectrum have been used to guide peak assignments of the secondary structures in the KGF spectrum.

The amide I region of protein FTIR-ATR spectra consists of many overlapping bands corresponding to distinct secondary structures.48 Advancements in resolution enhancement techniques such as Fourier self-deconvolution have improved the level of information regarding the protein structure that can be deduced from the FTIR-ATR spectrum.50

Fourier self-deconvolution of FTIR spectra consists of transforming a region of interest back to its interferogram stage, correcting for exponential decay in the corresponding Lorentzian cosine waves that are revealed, and applying the Fourier transformation to convert the spectrum back to the frequency domain, thereby recreating the original spectrum but now with significantly narrowed bandwidths.51 Fourier self-deconvoluted amide I regions allow for improved peak assignments corresponding to the secondary structure.52 In this work, we compare the FTIR-ATR spectrum of active and heat-denatured KGF in order to model conformational changes that occur upon the unfolding of KGF. Spectral characteristics of Fourier self-deconvoluted active and heat-denatured protein can then be monitored via ATR spectra of proteins at the copolymer interfaces.40–42,52

PCA of positive ToF-SIMS spectra of amino acids has been used to analyze and compare the orientation of proteins at interfaces.20,23,25,30,53–59 Since KGF is not limited to only orientational changes, which has been a constraint used in previous investigations,45 PCA results must be interpreted as describing both changes in KGF orientation and conformation that occur at the surfaces of the three copolymers.

We report the surface characterization of these hydrogel copolymers, as well as differences in KGF conformation observed by FTIR-ATR spectroscopy in conjunction with Fourier self-deconvolution and differences in both orientation and conformation observed by ToF-SIMS in conjunction with PCA.

II. EXPERIMENT

2-(Hydroxyethyl)methacrylate (HEMA, contains ≤50 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor, SKU 477028), MAA (contains 250 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor, SKU 155721), MMA (≤30 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor, SKU 55909), trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTMA, contains 600 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor, SKU 246808), 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN, SKU 441090), benzoin methyl ether (BME, 96%, SKU B8703), chlorotrimethylsilane (SKU 386529), phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, liquid, sterile filtered, and suitable for cell culture, SKU 806552), and glycerol (SKY G9012) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Human recombinant KGF was purchased from Prospec, and the Alexa Fluor™ 488 Microscale Protein Labeling Kit was purchased from Invitrogen (catalog #A30006).

A. Hydrogel copolymer preparation

0.5% crosslinked HEMA hydrogels were prepared by using HEMA, 0.5 vol. % TMPTMA, and 0.2% BME dissolved in glycerol. The components were then mixed, degassed, and injected in between silanized glass slides that were separated by a 1.1 mm thick Teflon spacer and allowed to polymerize under UV light for 30 min. HEMA/MMA and HEMA/MAA hydrogels were prepared using 5.89 mol. % of MMA and 5.89 mol. % MAA, respectively, and 0.5 vol. % TMPTMA, 94.1 mol. % HEMA, and 0.128 mol. % AIBN. The components were then mixed and injected in between silanized glass slides that were separated by a 1.1 mm thick Teflon spacer and were cured for 12 h at 50 °C and then for 24 h at 70 °C. All hydrogels were removed from the glass slides and washed three times at 70 °C in triply distilled water. Glass slides were silanized in a dessicator under vacuum using chlorotrimethylsilane. Hydrogels were cut into 1 × 1 cm2 pieces and oven and vacuum dried for ToF-SIMS experiments.

B. FTIR-ATR measurements

Spectra of KGF in solution and KGF at the surfaces of the HEMA, HEMA/MMA, and HEMA/MAA hydrogels were acquired using a Spectrum Two™ FTIR Spectrometer equipped with a Universal ATR accessory containing a diamond/ZnSe crystal. Sixty-four scans were acquired for each sample at 4 cm−1 resolution and scanned from 500 to 4000 cm−1. The spectrum software was used for the conversion of spectra from transmittance to absorbance, baseline correction, normalization, and ATR correction. KGF solutions were prepared at a concentration of 25 μM in PBS. KGF was heat-denatured by heating at 90 °C for 30 min. KGF spectra were determined by background subtraction of PBS. Hydrogels were prepared by incubation in 250 nM KGF solutions in PBS for 2 h, and spectra of hydrated samples were acquired. KGF spectra were determined by background subtraction using hydrogels that had been incubated in PBS only. Crystallographic data reported in the protein data bank (PDB) were collected using a Δ23 mutant due to its stability.16 The first 14 of the 23 residues are a loop structure. Our studies have been done with the full length construct.

C. Deconvolution of FTIR-ATR data

The amide I region of the obtained spectra was Fourier self-deconvoluted using origin pro 2017. Parameters for deconvolution were 0.5 for gamma and 0.1 for smoothing. Peaks in deconvoluted data were identified using the peak analysis tool.

D. ToF-SIMS

1 × 1 cm2 hydrogels were incubated with 125 nM KGF in PBS for 2 h. In order to remove salts and loosely bound KGF, all hydrogels were rinsed in stirred triply distilled water twice for 30 s each. Hydrogels were then oven dried at 50 °C for 2 h and vacuum dried overnight. KGF reconstituted in the presence of NaCl and PBS (Prospec formulation) has been reported to retain its native structure up to 60 °C.15,60 Hydrogels without KGF were also oven dried and vacuum dried. Positive secondary ion spectra were acquired on an ION-TOF V instrument (IONTOF, GmbH, Munster, Germany) using a Bi3+ primary ion source kept under static conditions (primary ion dose <1012 ions/cm2). Three positive spectra from two samples per copolymer type were collected from 100 × 100 μm regions (128 × 128 pixels). A pulsed flood gun was used for charge compensation. The ion beam was moved to a new spot on the sample after acquiring each spectrum. Spectra were acquired using high current bunched mode over a range of 0–1000 m/z. Mass resolution (m/Δm) at an m/z of 27 was between 5500 and 7000 for all samples. Copolymer samples without KGF were mass calibrated using CH3+, C2H3+, and C3H5+, and copolymer samples with KGF were mass calibrated using CH3+, C2H3+, C3H5+, and C5H10N+. Mass calibration errors were kept below 20 ppm.

E. Multivariate analysis

Peak lists were compiled for PCA analysis using the ion-tof surfacelab software. PCA analysis of the hydrogel copolymers with KGF used a peak list of reported amino acid fragments in the 0–200 m/z range.61 Only a list of amino acid fragments allowed for visualization of differences in conformation and orientation. Amino acid fragments that overlapped with fragments from HEMA, MMA, or MAA were eliminated from the peak list and resulted in a final list of 11 amino acids [Table S1 (Ref. 73)]. PCA analysis of the hydrogel copolymers without KGF used a peak list consisting of all peaks in the 0–200 m/z range greater than three times the background. Representative spectra of the copolymers can be found in Figs. S2(a)–S2(c).73 Peak lists were imported into the NESAC/BIO NBToolbox “spectragui” program written for matlab (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA).62 Data sets were normalized using the sum of selected peaks, mean centered, and square root transformed prior to PCA analysis. Amino acid intensities for the analysis of the KGF receptor binding site (serine and threonine) were normalized to the sum of all selected amino acids peaks in order to account for any existing variations in protein surface concentration. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of samples was computed using origin pro 2017.

III. RESULTS

A. Surface characterization of the hydrogel copolymers by ToF-SIMS and PCA

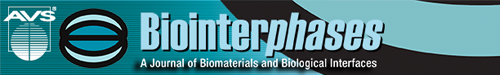

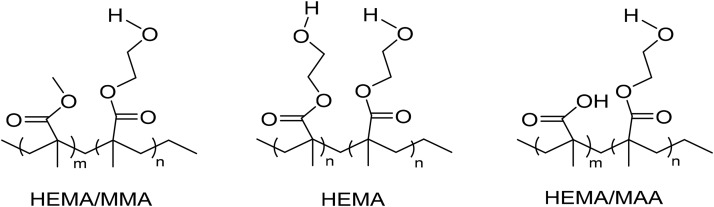

Figure 1 indicates the structures of the copolymers of interest. PCA was performed in order to determine whether the surfaces were distinguishable. Figure 2(a) of PC1 scores shows that PC1 captured 61% of the variance in the data set, and the HEMA/MAA and HEMA/MMA surfaces were distinguishable, while the HEMA/MAA and HEMA surfaces were not distinguishable and the HEMA/MMA and HEMA were distinguishable at the 95% confidence level. PC1 loadings in Fig. 2(b) showed that the HEMA/MMA copolymer was distinguished from the HEMA/MAA and HEMA copolymers by C2H6+, C3H8O+, C5H10+, and C4H9O+, while the HEMA/MAA and HEMA copolymers are distinguished from the MMA copolymer by C4H10+ and C4H11+. The PCA scores also show that the HEMA/MMA samples appear relatively homogeneous while heterogeneity was seen in the HEMA/MAA and HEMA copolymers. PC2 captures 19% of the variance and the three copolymers are not distinguishable at the 95% confidence interval as seen in Fig. S3(a) of the supplementary material. However, the HEMA/MAA copolymer exhibits both positive and negative scores while the HEMA/MMA and HEMA copolymers only exhibit positive scores. The peak with the most prominent negative loading in PC2 was due to C2H5O+ as seen in Fig. S3(b), which is a previously reported characteristic fragment of HEMA,63 and it is indicated in PC2 to be a major constituent of all three copolymers.

Fig. 1.

Structures of hydrogel copolymers that were crosslinked for the formation of pores.

Fig. 2.

(a) PC1 confidence limits at the 95% confidence level of the three hydrogel copolymer surfaces and (b) PC1 loadings.

The surface percent of the 5.89 mol. % MMA in HEMA copolymer was determined by calculating the peak area ratio of the highest PC1 loading, C4H9O+ [Fig. 2(b)], to the sum of C4H9O+ and the characteristic HEMA fragment C2H5O+, which gives a MMA surface concentration of 5% ± 2%. Principal component (PC) loadings have been previously used to determine distinguishing fragments at polymer surfaces.64–66 This approach fails in the calculation of the surface percent of the 5.89 mol. % MAA in HEMA copolymer because PC1 scores and loadings indicate that the HEMA/MAA and HEMA hydrogel copolymers do not show distinguishable fragmentation at the 95% confidence level. Therefore, while C4H10+ has the highest negative PC1 loading, it is not able to provide information regarding the MAA surface concentration of the HEMA/MAA hydrogel copolymer. In order to get around this issue, we have relied on previous literature reporting the characteristic fragmentation of MAA (Ref. 67) which reports C4H9+ and have calculated the peak area ratio of C4H9+ to the sum of C4H9+ to C2H5O+ which gives us a MAA surface concentration of 5% ± 2% as well.

While the HEMA/MAA and HEMA copolymer surfaces are not distinguishable by PCA analysis, differences in protein orientation and conformation at the surfaces of these copolymers are still of interest. High standard deviations in surface concentrations also indicate that our copolymerization process does not guarantee homogeneity at these surfaces; therefore, additional factors such as phase segregation and topography may contribute to differences observed in protein orientation and conformation at the surface and are the subject of future investigations.

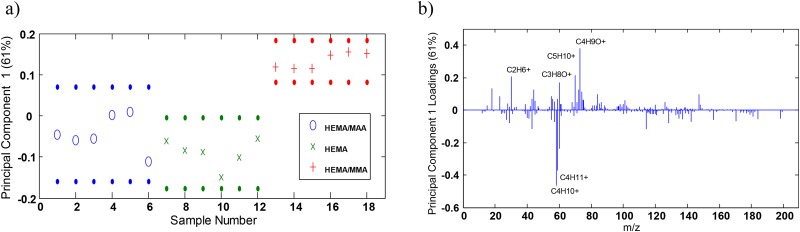

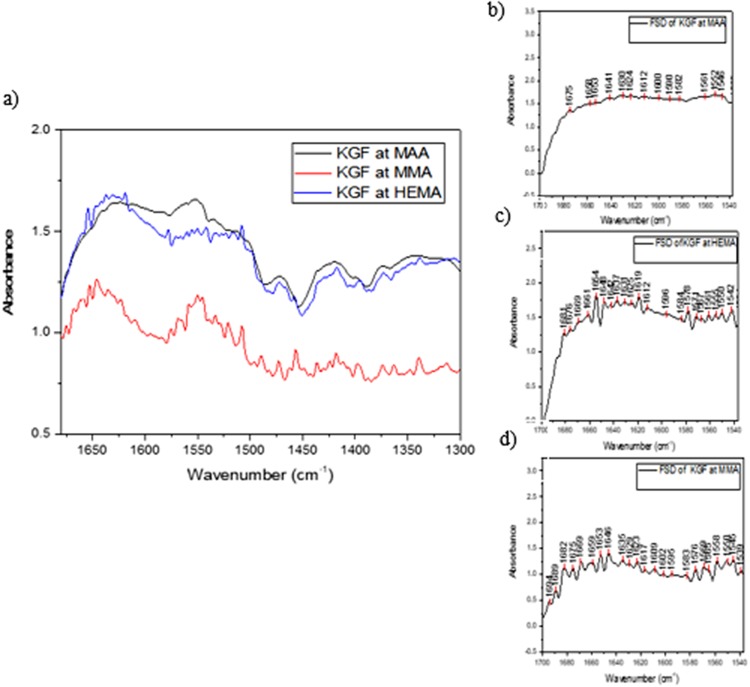

B. KGF conformation: KGF at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer appears to be unfolded; Fourier self-deconvolution analysis

KGF secondary structural elements were assigned in the amide I region of the FTIR-ATR spectrum of KGF in aqueous solution. Complexities in the interpretation of the amide II band (1500–1600 cm−1) due to factors such as concentration, particularly across our KGF spectra collected under different conditions, make it unsuitable for analysis. Peaks were assigned by Fourier self-deconvolution and comparison to existing peak assignments of bFGF (Table I).50 Differences between the structures of active and heat-denatured KGF were deduced by Fourier self-deconvolution of the respective spectra. Original spectra (1300–1700 cm−1) and deconvoluted spectra of the amide I region are shown in Figs. 3(a)–3(c). Deconvolution revealed that heat-denaturation results in changes to the extended strands (1637 cm−1), irregular/disordered regions (1647 cm−1), and loops (1654 cm−1) indicated in Fig. 3(b). All three peaks exhibit a shift to lower wavenumbers (1634, 1640, and 1651 cm−1 in the heat-denatured form), as well as an overall shift in the maxima of the amide I region to lower wavenumbers (from 1637 to 1628 cm−1), as seen in Fig. 3(c). Additionally, the active form of KGF shows that the three peaks have relatively similar absorbance-related intensity. In contrast, the heat-denatured form of KGF exhibits a much lower absorbance-related intensity for 1651 cm−1 relative to the peaks at 1634 and 1640 cm−1. Using these guidelines for structural changes in KGF due to unfolding, we have analyzed how the HEMA, HEMA/MMA, and HEMA/MAA surfaces influence KGF conformation.

Table I.

Assignments of secondary structural elements in KGF spectrum by comparison to reported bFGF spectrum.

| KGF peaks (cm−1) (PBS) |

bFGF peaks (cm−1) (D2O)a |

Assignmenta |

|---|---|---|

| 1619 | 1620 | Extended strands |

| 1637 | 1634 | Extended strands |

| 1647 | 1644 | Irregular/disordered |

| 1654 | 1650 | Loops |

| — | 1656 | Loops |

| 1661 | 1662 | Reverse turns |

| 1669 | 1668 | Reverse turns |

| 1676 | 1674 | Extended strands |

| 1682 | 1681 | Reverse turns |

| 1687 | 1687 | Reverse turns |

| 1696 | 1696 | Turns/carboxyl C=O |

Reference 50—the secondary structure of two recombinant human growth factors, platelet-derived growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor, as determined by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy.

Fig. 3.

(a) FTIR-ATR spectrum of active and heat-denatured KGF in PBS, (b) Fourier self-deconvoluted FTIR-ATR spectrum of active KGF in PBS, and (c) Fourier self-deconvoluted FTIR-ATR spectrum of heat-denatured KGF in PBS.

Figures 4(a)–4(d) show the amide I region of normalized FTIR-ATR spectra corresponding to KGF conformation at the three different hydrogel surfaces. The highest concentration is seen at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer, potentially due to increased protein diffusion at the surface and into the porous network due to additional hydrogen bonding from the carboxylic acid in MAA. The HEMA-only hydrogel shows a similar KGF surface concentration. The HEMA/MMA copolymer presents the lowest KGF surface concentration.

Fig. 4.

(a) FTIR-ATR spectra of KGF at the copolymer surfaces, (b) Fourier self-deconvoluted spectrum of KGF at the HEMA/MAA surface, (c) Fourier self-deconvoluted spectrum of KGF at the HEMA surface, and (d) Fourier self-deconvoluted spectrum of KGF at the HEMA/MMA surface.

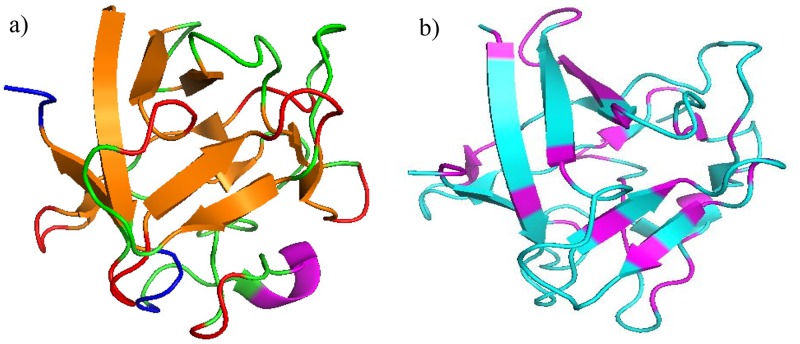

A lower absorbance-related intensity in comparison to the peaks at 1630 and 1641 cm−1 is seen at 1653 cm−1, which corresponds to the loops of KGF,52 at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer [Fig. 4(b)]. A shift in the maxima to lower wavenumbers as seen in heat-denatured KGF [Fig. 3(c)] is also seen in Fig. 4(b). There are two loops in KGF; the receptor (heparin)-binding loop and the loop at the beginning of the protein that is right next to an additional heparin binding site [Fig. 5(a), second loop not in the crystal structure].15 Therefore, it is possible that the HEMA/MAA copolymer is disrupting the loops through KGF-heparin/heparan sulfate mimicking interactions, resulting in an unfolded conformation. The HEMA/MMA copolymer alternatively appears to target hydrophobic regions of KGF. For example, in the extended strands region between 1622 and 1634 cm−1, the 1635 cm−1 has a lower absorbance-related intensity to the 1646 and 1653 cm−1, while the 1646 cm−1 (irregular/disordered) and 1653 cm−1 (loops) have similar absorbance-related intensities as seen in the active KGF spectrum. The crystal structure of KGF shows that the extended strands create a tightly bound core [Figs. 5(a) and 5(b)].15 KGF at the surface of HEMA also appears to develop an extra peak at 1646 cm−1 in the irregular/disordered region. Overall, KGF adopts a native conformation on the surfaces of the HEMA and HEMA/MMA copolymers after a 2-h incubation, while it appears to unfold at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer.

Fig. 5.

(a) Crystal structure of KGF with secondary structural elements labeled created in PyMol: red—reverse turns, orange—extended strands, blue—disordered, pink—heparin binding loop, green—unassigned, (b) crystal structure of KGF with hydrophobic (pink) and hydrophilic amino acids labeled (blue) [PDB ID: 1QQK (Ref. 68)].

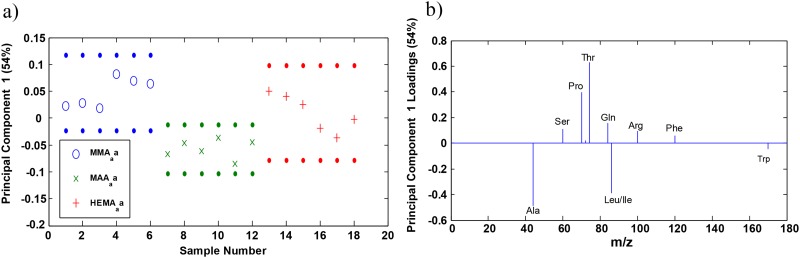

C. KGF orientation and conformation: ToF-SIMS and PCA show that KGF hydrophobic amino acids are exposed at the HEMA/MAA copolymer surface while hydrophilic amino acids are exposed at the HEMA/MMA copolymer

Given that the FTIR-ATR results indicate that conformational differences in KGF occur on the three types of copolymer surfaces, we must attribute differences in KGF seen in the ToF-SIMS results to both orientational and conformational changes. Differences in KGF orientation/conformation at the surface of the hydrogel copolymers due to MMA and MAA addition were studied by PCA of the ToF-SIMS results.

Figure 6(a) of PC1 scores shows that PC1 captures 54% of the variance in the data at the 95% confidence level. KGF orientation/conformation at the HEMA/MMA and HEMA/MAA copolymer surface regions is distinguishable at the 95% confidence level.58 KGF orientation and conformation at the HEMA surface regions displays characteristics seen in both the HEMA/MMA and HEMA/MAA copolymers.

Fig. 6.

(a) PC1 confidence limits of protein orientation/conformation on the hydrogel surfaces and (b) PC loadings at the 95% confidence level.

Amino acids used in the peak list [Table S1 (Ref. 73)] were characterized as hydrophilic and hydrophobic in order to determine whether the PC1 loadings indicated a pattern for KGF orientation. Hydrophilic amino acids were found to have positive loadings while hydrophobic amino acids had negative loadings. PC1 loadings shown in Fig. 6(b) indicate that the hydrophobic amino acids alanine, isoleucine/leucine, and tryptophan were detected in high intensities at the surface of the HEMA/MAA copolymer while hydrophobic amino acids, with the exception of phenylalanine (a hydrophilic amino acid), serine, threonine, glutamine, and arginine, were detected in high intensities at the surface of the HEMA/MMA copolymer. Phenylalanine may have loaded positively due to electrostatic repulsion with MMA, similar to the repulsion leading to phase separation in styrene/MMA blends,69 which ultimately resulted in the phenylalanine facing away from the MMA surface and being detected. These results suggest that hydrophobic amino acids are oriented outwards while mostly hydrophilic amino acids interact with the HEMA/MAA surface, and that mostly hydrophilic amino acids are oriented outwards while hydrophobic amino acids interact with the HEMA/MMA surface.

Interestingly, hydrophilic amino acids are found both (1) buried within the extended strands away from the solvent exposed reverse turns and (2) also in the solvent exposed loops and disordered regions.15 This suggests that in the HEMA/MMA copolymer, both the hydrophobic nature of MMA and hydrophilic nature of HEMA may be contributing to interactions with different parts of KGF. This is backed up by the fact that the orientation/conformation of KGF at the HEMA surface is not distinguishable from the orientation/conformation of KGF at the HEMA/MMA surface at the 95% confidence level, even though KGF orientation/conformation at the HEMA/MAA and HEMA/MMA surfaces is distinguishable [Fig. 6(a)].

PC2 captures 37% of the variance at the 95% confidence level and creates a distinction between the two different HEMA/MMA samples that were studied [three different regions studied on each sample; Figs. S4(a) and S4(b)]. PC2 scores indicate that there is heterogeneity in protein orientation among the HEMA/MMA samples. This suggests the possibility of different amounts of phase segregation at the surface caused by the formulation method that may be causing minor differences in protein orientation among the HEMA/MMA samples. The HEMA/MAA and HEMA copolymers appear homogenous in PC2, and PC2 loadings indicate no clear pattern distinguishing orientation at the surface of the HEMA/MMA copolymer.

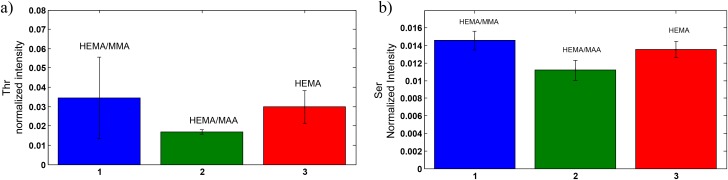

Of particular importance are the positive loadings of serine and threonine in PC1 [Fig. 6(b)]. Mutations in residues T126 and S122 to alanine correspond to the biological activity being reduced to 70% and 60% when evaluated based on tritiated thymidine uptake in Balb/MK cells.15 These residues are in the receptor binding loop (residues 122–132). Threonine does not have a higher normalized intensity at the HEMA/MMA surface at the 0.05 level [Fig. 7(a)] but does have a higher normalized intensity when three of the unexpectedly small values of threonine intensity are omitted from the ANOVA analysis. In this case, threonine has a statistically significant higher normalized intensity at the HEMA/MMA surface in comparison to the HEMA and HEMA/MAA surfaces as indicated by one-way ANOVA at the 0.05 level (F2,12 = 10.46, p < 0.05). Precedence for this omission is the previously mentioned heterogeneity at the HEMA/MMA surface likely due to the formulation method. The threonine values of samples 1–3 were omitted because Fig. 6(a) shows that samples 1–3 contain significant overlap with KGF orientation/conformation at the HEMA surface. Serine has a statistically significant higher normalized intensity at the HEMA/MMA surface in comparison to the HEMA/MAA surface as indicated by one-way ANOVA at the 0.05 level (F2,15 = 16.42, p < 0.05) as seen in Fig. 7(b). High normalized intensities of serine and threonine at the HEMA/MMA surface indicate that KGF at the HEMA/MMA surface may be in an orientation/conformation more likely to bind the KGF receptor in comparison to KGF at the HEMA or HEMA/MAA surface.

Fig. 7.

Peak intensities of (a) threonine and (b) serine when normalized by the sum of selected peaks.

The KGF crystal structure in Fig. 5(b) is labeled with hydrophobic (pink, Ala, Gly, Val, Ile, Leu, Trp) and hydrophilic (blue, all remaining) amino acids labeled and shows that hydrophobic amino acids are mostly found to flank the beginning and end of the six beta sheets near the solvent exposed reverse turns, while the hydrophilic amino acids are found in the middle of the beta sheets. Though only 11 (12 including Ile/Leu) amino acids are included in the PCA, we believe that our results are representative of the system because Fig. 5(b) shows that hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids tend to localize separately in KGF. Given this knowledge, we believe that the inclusion of the remaining amino acids in the PCA would be beneficial but is not possible due to the fragmentation of the hydrogels; hence, we are comfortable forming the conclusions discussed below.

The results suggest that the HEMA/MAA copolymer interacts with hydrophilic amino acids of the beta sheets near solvent exposed regions and does not allow for accessibility of residues involved in receptor binding at the surface, while the HEMA/MMA copolymer specifically interacts with hydrophobic amino acids and exposes hydrophilic amino acids found within the receptor binding loop and beta sheets at the surface.

IV. DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that copolymers of HEMA made to adjust the surface chemistry affect protein orientation and conformation differentially. Our results suggest that the HEMA/MMA copolymer is likely to allow for KGF to remain in its native conformation and be receptor accessible, while the HEMA/MAA copolymer causes KGF to unfold and does not allow for KGF to be receptor accessible.

PCA of copolymer surfaces has been previously reported to distinguish small changes in composition which can then be used to explain differences in biological response, such as cell adhesion at these surfaces.64,66,70,71 Similarly, we are able to use PCA to show that the HEMA/MMA and HEMA/MAA copolymers are distinguishable surfaces while the HEMA/MAA and HEMA surfaces are not, and that our formulation method for copolymers results in heterogeneities at these surfaces. Our PCA scores regarding KGF orientation/conformation are in agreement with PCA of the copolymers because orientation/conformation at the HEMA/MMA surface is distinguishable from the HEMA/MAA surface but neither is distinguishable from the HEMA surface. Heterogeneity in orientation/conformation can potentially be explained by the heterogeneities in the surface composition.

FTIR-ATR analysis as well as other forms of vibrational spectroscopy has been used in conjunction with PCA analysis to interpret changes in orientation and conformation at different copolymer surfaces.31,72 Our FTIR-ATR results of KGF at the surfaces of the three copolymers show that KGF appears to adapt an unfolded conformation similar to that of heat-denatured KGF at the HEMA/MAA surface but remains in its native conformation at the surface of HEMA and HEMA/MMA. There is also a higher surface concentration of KGF at the HEMA/MAA and HEMA surfaces in comparison to the HEMA/MMA surface. PCA of the ToF-SIMS spectra indicates that the surface of the HEMA/MMA copolymer has hydrophobic amino acids interacting with the surface and hydrophilic amino acids oriented away outwards while the HEMA/MAA copolymer has hydrophilic amino acids interacting with the surface and hydrophobic amino acids oriented outwards. Our observations regarding the orientation and conformation of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids have been previously observed in AFM studies of bovine serum albumin (BSA) adsorbed at the surface of MMA/AA (acrylic acid) block copolymers.18 Hydrophilic groups of BSA were oriented away from the MMA surface and this was detected by differences in adhesive force between BSA hydrophilic/hydrophobic groups and the AFM tip.

Comparison of intensities of receptor binding site amino acids has previously informed regarding receptor binding capability of adsorbed proteins.23 In our results, high normalized intensities of serine and threonine at the HEMA/MMA surface suggest that KGF is in an orientation/conformation likely to bind the KGF receptor.

To summarize our interpretation of the results of this study, we believe that the HEMA/MAA copolymer possesses characteristics that are beneficial in obtaining a high surface concentration of KGF. However, this strong interaction likely leads to a less accessible orientation/conformation of KGF at the surface with receptor binding amino acids facing toward the hydrogel surface. The ability of the HEMA/MAA copolymer to act as a drug delivery vehicle therefore depends on the strength of the HEMA/MAA interaction with KGF in comparison to the strength of the KGF receptor interaction in the presence of epithelial cells containing the KGF receptor. We believe that the interaction between HEMA/MAA and KGF is potentially too strong, which leads to KGF unfolding. The HEMA/MMA copolymer does not disrupt the conformation of KGF and unfolding is avoided potentially due to these weaker protein–material interactions, and the PCA results suggest that more regions of KGF are oriented away from the HEMA/MMA surface and are more receptor accessible. This interaction is possibly beneficial in the development of the ideal drug delivery device.

V. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

We have characterized the abilities of HEMA/MMA and HEMA/MAA hydrogels to promote adsorption and diffusion at their surface related to KGF orientation and conformation combining ToF-SIMS/PCA of the hydrogels, ToF-SIMS/PCA of KGF orientation, and FTIR-ATR spectra of KGF conformation. While neither polymethacrylic acid nor polymethyl methacrylate are ideal drug delivery vehicles, this approach has allowed for the characterization of differences in KGF orientation/conformation caused by new properties of the modified HEMA surfaces. We believe that differences in receptor binding and efficacy in wound closure among the copolymers will likely be due to differences in KGF orientation and conformation. We aim to focus future studies defining the role of formulation-dependent phase segregation and porous topography on KGF localization and orientation/conformation, and we will evaluate the effects of KGF orientation, conformation, and localization on receptor binding and wound closure through in vitro heparin binding assays and previously developed in vivo wound closure assays.4–6,8

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the undergraduate student Zoe Vaughn in her support in hydrogel synthesis as well as the members of the Gardella group for thoughtful discussions. These studies were supported by funding from the John and Frances Larkin Endowment awarded to J.A.G. The authors also thank Dan Graham, Ph.D., for developing the NESAC/BIO Toolbox used in this study and NIH Grant No. EB-002027 for supporting the toolbox development.

References

- 1.Hoare T. R. and Kohane D. S., Polymer 49, 1993 (2008). 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.01.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.am Ende M. T. and Peppas N. A., J. Control. Release 48, 47 (1997). 10.1016/S0168-3659(97)00032-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao J. K., Ramesh D. V., and Rao K. P., Biomaterials 15, 383 (1994). 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90251-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp J. et al. , Mol. Ther. 10, 86 (2004). 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marti G. P., Mohebi P., Liu L., Wang J., Miyashita T., and Harmon J. W., Methods Mol. Biol. 423, 383 (2008). 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen T. T., Thao D. T., and Thuoc T. L., Protein Pept. Lett. 21, 306 (2014). 10.2174/09298665113206660115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns S. A. and Gardella J. A., Appl. Surf. Sci. 255, 1170 (2008). 10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.05.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns S. A., Hard R., W. L. Hicks, Jr., Bright F. V., Cohan D., Sigurdson L., and J. A. Gardella, Jr., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 94A, 27 (2010). 10.1002/jbm.a.32654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho E. J., Tao Z., Tang Y., Tehan E. C., Bright F. V., Hicks W. L., Gardella J. A., and Hard R., Appl. Spectrosc. 56, 1385 (2002). 10.1366/00037020260377661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho E. J., Tao Z., Tang Y., Tehan E. C., Bright F. V., Hicks W. L., Gardella J. A., and Hard R., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 66A, 417 (2003). 10.1002/jbm.a.10598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.W. L. Hicks, Jr., L. A. Hall, III, Hard R., Gardella J., Bright F., Parasharama N., Lwebuga-Mukasa J., and Sigurdson L., Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 130, 446 (2004). 10.1001/archotol.130.4.446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez P. A. and Rampy M. A., J. Surg. Res. 81, 238 (1999). 10.1006/jsre.1998.5501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu Y.-R. et al. , Biochemistry 38, 2523 (1999). 10.1021/bi9821317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ornitz D. M., BioEssays 22, 108 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osslund T. D. et al. , Protein Sci. 7, 1681 (2008). 10.1002/pro.5560070803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye S. et al. , Biochemistry 40, 14429 (2001). 10.1021/bi011000u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu D. E., Kotsmar C., Nguyen F., Sells T., Taylor N. O., Prausnitz J. M., and Radke C. J., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 18109 (2013). 10.1021/ie402148u [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palacio M. L. B., Schricker S. R., and Bhushan B., J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 630 (2011). 10.1098/rsif.2010.0557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratner B. D., Biomaterials 28, 5144 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunkemeier J. M., Tsai W. B., Alexander M. R., Castner D. G., and Horbett T. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 51, 669 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry M., Dupont-Gillain C., and Bertrand P., Langmuir 19, 6271 (2003). 10.1021/la034081z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kempson I. M., Martin A. L., Denman J. A., French P. W., Prestidge C. A., and Barnes T. J., Langmuir 26, 12075 (2010). 10.1021/la101253g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tronic E. H., Yakovenko O., Weidner T., Baio J. E., Penkala R., Castner D. G., and Thomas W. E., Biointerphases 11, 029803 (2016). 10.1116/1.4943618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai W.-B., Grunkemeier J. M., and Horbett T. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 67A, 1255 (2003). 10.1002/jbm.a.20024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner M. S., Tyler B. J., and Castner D. G., Anal. Chem. 74, 1824 (2002). 10.1021/ac0111311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y., Zhang M., Hauch K. D., and Horbett T. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 85A, 829 (2007). 10.1002/jbm.a.31505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M. and Horbett T. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 89A, 791 (2008). 10.1002/jbm.a.32085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng X., Canavan H. E., Graham D. J., Castner D. G., and Ratner B. D., Biointerphases 1, 61 (2006). 10.1116/1.2187980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hugoni L., Montaño-Machado V., Yang M., Pauthe E., Mantovani D., and Santerre J. P., Biointerphases 11, 029809 (2016). 10.1116/1.4950887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmüser L., Encinas N., Paven M., Graham D. J., Castner D. G., Vollmer D., Butt H. J., and Weidner T., Biointerphases 11, 031007 (2016). 10.1116/1.4959237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sommerfeld J., Richter J., Niepelt R., Kosan S., Keller T. F., Jandt K. D., and Ronning C., Biointerphases 7, 55 (2012). 10.1007/s13758-012-0055-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stallard C. P., McDonnell K. A., Onayemi O. D., O’Gara J. P., and Dowling D. P., Biointerphases 7, 31 (2012). 10.1007/s13758-012-0031-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thyparambil A. A., Wei Y., and Latour R. A., Biointerphases 10, 019002 (2015). 10.1116/1.4906485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anirudhan T. S. and Mohan A. M., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 110, 167 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowersock T. L., Shalaby W. S. W., Levy M., Blevins W. E., White M. R., Borie D. L., and Park K., J. Control. Release 31, 245 (1994). 10.1016/0168-3659(94)90006-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozlovskaya V., Kharlampieva E., Mansfield M. L., and Sukhishvili S. A., Chem. Mater. 18, 328 (2006). 10.1021/cm0517364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vo T. N., Kasper F. K., and Mikos A. G., Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 1292 (2012). 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelikin A. N., Price A. D., and Städler B., Small 6, 2201 (2010). 10.1002/smll.201000765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvarez-Lorenzo C., Hiratani H., Gómez-Amoza J. L., Martínez-Pacheco R., Souto C., and Concheiro A., J. Pharm. Sci. 91, 2182 (2002). 10.1002/jps.10209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bohnert J. L., Horbett T. A., Ratner B. D., and Royce F. H., Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 29, 362 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo E. J., Koenig J. L., Andersen J. M., and Lo J., Biomaterials 5, 319 (1984). 10.1016/0142-9612(84)90014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castillo E. J., Koenig J. L., and Anderson J. M., Biomaterials 7, 89 (1986). 10.1016/0142-9612(86)90062-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castillo E. J., Koenig J. L., Anderson J. M., and Jentoft N., Biomaterials 7, 9 (1986). 10.1016/0142-9612(86)90081-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baio J. E., Weidner T., Ramey D., Pruzinsky L., and Castner D. G., Biointerphases 8, 18 (2013). 10.1186/1559-4106-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baugh L., Weidner T., Baio J. E., Nguyen P. C., Gamble L. J., Stayton P. S., and Castner D. G., Langmuir 26, 16434 (2010). 10.1021/la1007389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J., Buck S. M., and Chen Z., J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 11666 (2002). 10.1021/jp021363j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castillo E. J., Koenig J. L., Anderson J. M., and Lo J., Biomaterials 6, 338 (1985). 10.1016/0142-9612(85)90089-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chittur K. K., Biomaterials 19, 357 (1998). 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt M. P. and Martínez C. E., Langmuir 32, 7719 (2016). 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prestrelski S. J., Arakawa T., Kenney W. C., and Byler D. M., Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 285, 111 (1991). 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90335-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipp E. D., Appl. Spectrosc. 40, 1009 (1986). 10.1366/0003702864507954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Byler D. M. and Susi H., Biopolymers 25, 469 (1986). 10.1002/bip.360250307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J. L. S. and Gilmore I. S., Surface Analysis—The Principal Techniques (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanni O. D., Wagner M. S., Briggs D., Castner D. G., and Vickerman J. C., Surf. Interface Anal. 33, 715 (2002). 10.1002/sia.1438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao L., Chang M., Lee C.-Y., Castner D. G., Sukavaneshvar S., Ratner B. D., and Horbett T. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 81A, 827 (2007). 10.1002/jbm.a.31091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foster R. N., Harrison E. T., and Castner D. G., Langmuir 32, 3207 (2016). 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b04743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michel R., Pasche S., Textor M., and Castner D. G., Langmuir 21, 12327 (2005). 10.1021/la051726h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner M. S. and Castner D. G., Langmuir 17, 4649 (2001). 10.1021/la001209t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H., Castner D. G., Ratner B. D., and Jiang S., Langmuir 20, 1877 (2004). 10.1021/la035376f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsu E., Osslund T., Nybo R., Chen B.-L., Kenney W. C., Morris C. F., Arakawa T., and Narhi L.O., Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 145 (2006). 10.1093/protein/gzj013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Samuel N. T., Wagner M. S., Dornfeld K. D., and Castner D. G., Surf. Sci. Spectra 8, 163 (2001). 10.1116/11.20020301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graham D., see http://www.nb.uw.edu/mvsa/multivariate-surface-analysis-homepage.

- 63.Wagner M. S., Anal. Chem. 77, 911 (2005). 10.1021/ac048945c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hook A. L., Anderson D. G., Langer R., Williams P., Davies M. C., and Alexander M. R., Biomaterials 31, 187 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Urquhart A. J., Taylor M., Anderson D. G., Langer R., Davies M. C., and Alexander M. R., Anal. Chem. 80, 135 (2008). 10.1021/ac071560k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang J. et al. , Biomaterials 31, 8827 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davies M. C., Lynn R. A. P., Hearn J., Paul A. J., Vickerman J. C., and Watts J. F., Langmuir 12, 3866 (1996). 10.1021/la960169j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., and Bourne P. E., Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235 (2000). 10.1093/nar/28.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harirchian-Saei S., Wang M. C., Gates B. D., and Moffitt M. G., Langmuir 29, 10838 (2012). 10.1021/la301298p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mei Y. et al. , Adv. Mater. 21, 2781 (2009). 10.1002/adma.200803184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mei Y. et al. , Nat. Mater. 9, 768 (2010). 10.1038/nmat2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sofia S. J., Premnath V., and Merrill E. W., Macromolecules 31, 5059 (1998). 10.1021/ma971016l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.See supplementary material at 10.1116/1.5051655E-BJIOBN-13-318806 for the peak list of amino acids used for PCA, representative ToF-SIMS spectra of the copolymers, and additional PC scores and loadings from Results sections A and C. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at 10.1116/1.5051655E-BJIOBN-13-318806 for the peak list of amino acids used for PCA, representative ToF-SIMS spectra of the copolymers, and additional PC scores and loadings from Results sections A and C. [DOI]