Abstract

Background:

Electronic health (e-health) tools may support patients’ self-management of chronic kidney disease. We aimed to identify preferences of patients with chronic kidney disease, caregivers and health care providers regarding content and features for an e-health tool to support chronic kidney disease self-management.

Methods:

A patient-oriented research approach was taken, with 6 patient partners (5 patients and 1 caregiver) involved in study design, data collection and review of results. Patients, caregivers and clinicians from across Canada participated in a 1-day consensus workshop in June 2018. Using personas (fictional characters) and a cumulative voting technique, they identified preferences for content for 8 predetermined topics (understanding chronic kidney disease, diet, finances, medication, symptoms, travel, mental and physical health, work/school) and features for an e-health tool.

Results:

There were 24 participants, including 11 patients and 6 caregivers, from across Canada. The following content suggestions were ranked the highest: basic information about kidneys, chronic kidney disease and disease progression; reliable information on diet requirements for chronic kidney disease and comorbidities, renal-friendly foods; affordability of medication, equipment, food, financial resources and planning; common medications, adverse effects, indications, cost and coverage; symptom types and management; travel limitations, insurance, access to health care, travel checklists; screening and supports to address mental health, cultural sensitivity, adjusting to new normal; and support to help integrate at work/school, restrictions. Preferred features included visuals, the ability to enter and track health information and interact with health care providers, “on-the-go” access, links to resources and access to personal health information.

Interpretation:

A consensus workshop developed around personas was successful for identifying detailed subject matter for 8 predetermined topic areas, as well as preferred features to consider in the codevelopment of a chronic kidney disease self-management e-health tool. The use of personas could be applied to other applications in patient-oriented research exploring patient preferences and needs in order to improve care and relevant outcomes.

Plain language summary: Electronic health (e-health) tools such as websites and mobile apps may help patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers manage their health and well-being. We aimed to identify the preferences of patients with chronic kidney disease, caregivers and health care providers regarding content and features for an e-health tool to support self-management of chronic kidney disease. Our study team included 6 patient partners, researchers, clinicians and decision-makers. The patient partners were involved in all phases of the research. We invited the participants to discuss content preferences for 8 predetermined topics and features for an e-health tool. Participants wanted access to general and concise information about the kidneys, chronic kidney disease and disease progression; diet requirements for chronic kidney disease and related conditions; affordable food, medication, financial resources and finance planning; reasons for and adverse effects of medications; symptom management; travel limitations and insurance; mental health screening and supports; and work/school guidance. They wanted an e-health tool that can be accessed “on-the-go,” displays information visually and provides links to resources, and enables the user to enter and track health information, and interact with health care providers. These findings will help guide codevelopment of an e-health tool for self-management for adult patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers.

The focus on person-centred care has prompted changes in patient engagement in their health, as well as their contribution in research. Patients with chronic kidney disease and their caregivers embark on a lifelong journey that entails dealing with complex medical issues and balancing medical management of kidney disease with demands of their daily lives. For the approximately 9% of Canadian adults with chronic kidney disease, these issues often include management of diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, and strategies to slow progression of their chronic kidney disease to delay or avoid development of end-stage kidney disease.1 The unique expertise that patients with chronic kidney disease develop in managing their illness is invaluable to the research processes.

A national project to set research priorities involving patients, caregivers and stakeholders identified the need to enhance patient-targeted strategies for self-managing chronic kidney disease.2 Self-management, a complex set of processes that involves acquiring knowledge, skills and confidence to manage a chronic disease,3 has the potential to positively affect clinical outcomes and quality of life for patients with chronic kidney disease.4 There is the opportunity to involve patients in the development of self-management support interventions that meet their needs, specifically around the areas of knowledge, how they receive knowledge and timeliness of the information.5

Traditionally, self-management interventions for patients with chronic kidney disease have included education and support through face-to-face interactions, with minimal use of electronic health (e-health) tools (e.g., websites, mobile apps, short-messaging service).6 The use of e-health tools, including the Internet, mobile-phone–based apps, computer-based tools and mixed-mode tools, may enhance patient self-management. Although e-health tools will not replace the provider–patient relationship, they are a potential platform to augment support for chronic kidney disease self-management.

The current study is part of a national multiphase project involving patients, caregivers, health care providers, researchers and policy-makers (Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease [Can-SOLVE CKD] Network).7 Five patient partners and 1 caregiver were engaged in the previous phases of this work, including a scoping review, a survey of chronic kidney disease clinics, analysis of behaviours of patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers by means of the Theoretical Domains Framework and a qualitative study.5,6,8,9 This has laid the foundation for the present study. Based on the qualitative study, 8 topic areas were identified — understanding chronic kidney disease, diet, medications, symptoms, finances, mental and physical health, travel and work/school — as well as features including mixed-content formats (e.g., visuals, text, user-generated content). Using a consensus workshop and personas, we aimed to address the following question: What are the preferences for content for the 8 predetermined topic areas and features for a self-management e-health tool for patients with chronic kidney disease?

Methods

Study design

We used a 1-day consensus workshop format to engage participants in identifying content preferences for the 8 topic areas and features of a self-management e-health tool for patients with chronic kidney disease. The workshop comprised a combination of small- and large-group exercises using personas, facilitated by people with experience in group-facilitation techniques. In the final phase of the workshop, we used a cumulative voting technique (dot democracy)10 approach whereby participants used dots to delineate their preferences. We used the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and Public (GRIPP2)11 to report this work.

Persona cocreation

Personas are fictitious descriptions of users that facilitate and guide the creation of interactive systems. They have been used in the fields of human–computer interaction and marketing.12 For the purpose of our workshop, personas were used to represent hypothetical patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers, with the aim of facilitating discussion among all participants. We developed the personas as an archetypical representation of real and potential e-health tool users to illustrate their characteristics (e.g., needs, skills, behaviours, motivations, frustrations and goals). The general principles of persona development include the use of empirical evidence (quantitative and qualitative data), the concept of “particularity” (i.e., user characteristics and behaviours) and the use of a collaborative approach, with engagement of relevant stakeholders.12,13

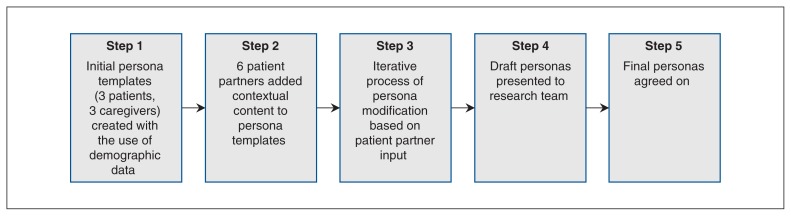

Figure 1 shows the multistep process used for cocreation of the 6 personas (3 patients and 3 caregivers). We initially created a skeleton persona using quantitative and qualitative data from our prior work including demographic description (e.g., age, diagnosis, hobbies, life experiences), goals (e.g., lifestyle) and challenges (e.g., frustrations, concerns).5,8 In consultation with our 6 patient partners, using an iterative process, we modified persona features, including names, goals, challenges, technical ability (computer literacy, Internet use/availability) and health behaviour characteristics (health literacy, support networks, knowledge of health status, readiness for change). The revised personas were reviewed at an in-person research team meeting and were finalized through discussion and agreement. General comments from our patient partners regarding persona cocreation included “I felt I could give meaningful input and be involved in this step of the research” and “We had the opportunity to make them [personas] real — ‘persona-fying’ my experience.” An example of a patient persona is provided in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E713/suppl/DC1).

Figure 1:

Persona cocreation process.

Participants and setting

The study was conducted from April to September 2018. English-speaking people aged 18 years or more who were able to provide informed consent and were aware of their diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (categories 1–5, not receiving dialysis), regardless of disease etiology or duration, were eligible to participate in the workshop. Informal caregivers (e.g., family members, friends) of people with chronic kidney disease, researchers, clinicians and policy-makers with an interest in chronic kidney disease care were also eligible. Through email invitation, participants were recruited from the Can-SOLVE CKD Network, as well as from among prior focus group and interview participants5 who had provided consent to be contacted for future phases of this work. We purposefully sampled to ensure we had diversity from all stakeholder groups. Two weeks before the consensus workshop, participants received materials including a reflective questionnaire developed by the study team that asked them to 1) reflect on their personal experiences with chronic kidney disease based on their stakeholder roles, 2) what questions they would have regarding managing or understanding chronic kidney disease, finances, symptoms, medication, work/school, travel, diet, and mental and physical health and 3) what would be the best way of providing information regarding chronic kidney disease topics and resources. The purpose of the questionnaire was to capture participants’ individual self-management perspectives before asking them to take on a persona perspective at the workshop.

Data collection

At the beginning of the workshop, held on June 13, 2018, the main facilitator (M.D.) presented background information, including results from a scoping review of support interventions for chronic kidney disease self-management,8 a survey of Canadian chronic kidney disease clinics to identify their resources used6 and findings of a qualitative study of needs of patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers.5 Facilitators moderated 4 heterogeneous small groups (representatives from all stakeholder groups) using a discussion guide (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E713/suppl/DC1), directing participants to assume a persona lens and provide input regarding the persona’s needs for each topic area and e-health feature category. Small-group discussions were captured by a note taker and were also audio recorded. They were followed by a large-group discussion, during which a representative from each group provided a summary of the group’s ideas. Subject matter from the small- and large-group discussions was recorded and categorized on flip charts by the facilitators under each of the 8 topic areas and general e-health features. We used cumulative dot voting to identify preferences for content and features. All participants were provided with 5 dots to vote on 5 individual content ideas/suggestions under each of the 8 topic areas and 3 dots for each of the feature categories that they considered “important to people with chronic kidney disease and those that care for them.” All participants completed a satisfaction survey at the end of the workshop (Appendix 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E713/suppl/DC1).

Patient engagement

Six patient partners (G.H., C.A.L., C.L.L., B.W., M.L.D., D.S.) from across Canada are collaborators on the chronic kidney disease self-management research team. One is a caregiver, and 5 are patients with chronic kidney disease. The patient partners were involved in the study design (i.e., co-planning consensus workshop and materials), participated in data collection (i.e., study participants at consensus workshop), reviewed final outputs, and contributed to manuscript preparation and dissemination (i.e., conferences).

Data analysis

We used descriptive analysis for demographic and workshop data. To rank preferences for each of the content suggestions under the 8 topic areas and general features, we tallied the dots and ranked the content ideas as high (≥ 10 dots), medium (3–9 dots) or low (< 3 dots) priority. To ensure all subject matter was captured, 2 team members (B.R.H. and M.D.), clinician-researchers with an interest in chronic kidney disease care, independently reviewed the list of preferences, reflective questionnaire responses, field notes and flip chart data. They then reviewed and finalized the wording for the content suggestions for the 8 topic areas and general features.

Four weeks after the workshop, participants were provided the results and were offered the opportunity to submit feedback via email.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board. Participants provided written informed consent before participating.

Results

Workshop

The workshop included 24 participants from across Canada: 11 patients, 6 caregivers, 2 nurses, 1 dietitian, 1 pharmacist, 1 policy-maker, 1 primary care physician and 1 nephrologist. The majority of participants were female (19 [79%]), under the age of 65 years (20 [83%]), married (15 [62%]) and employed (19 [79%]), had at least a postsecondary education (21 [88%]) and lived in an urban setting (15 [62%]) (Table 1). The majority of patient participants had an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or greater (8 [73%]) and had received their diagnosis within the previous 10 years (7 [64%]).

Table 1:

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants n = 24 |

|---|---|

| Role | |

| Patient | 11 (46) |

| Caregiver | 6 (25) |

| Health care professional* | 7 (29) |

| Female sex | 19 (79) |

| Age, yr | |

| < 50 | 11 (46) |

| 50–64 | 9 (38) |

| 65–74 | 3 (12) |

| ≥ 75 | 1 (4) |

| Marital status | |

| Common-law | 5 (21) |

| Divorced | 2 (8) |

| Married | 15 (62) |

| Single | 2 (8) |

| Geographical location (population) | |

| < 500 000 (rural) | 9 (38) |

| ≥ 500 000 (urban) | 15 (62) |

| Province | |

| British Columbia | 5 (21) |

| Alberta | 14 (58) |

| Saskatchewan | 1 (4) |

| Manitoba | 1 (4) |

| Ontario | 2 (8) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 (4) |

| Level of education | |

| Primary (grade 12 or less) | 3 (12) |

| Postsecondary (college, university, trade school) | 12 (50) |

| Graduate school | 9 (38) |

| Level of employment | |

| Full-time | 11 (46) |

| Part-time | 8 (33) |

| Retired | 4 (17) |

| Student | 1 (4) |

| Self-reported patient clinical characteristics (n = 11) | |

| Time since chronic kidney disease diagnosis, yr | |

| ≤ 5 | 5 (45) |

| 6–10 | 2 (18) |

| ≥ 11 | 4 (36) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | |

| 30–60 | 5 (45) |

| 15–29 | 3 (27) |

| < 15 | 1 (9) |

| Unknown | 2 (18) |

Two nurses, 1 dietitian, 1 pharmacist, 1 primary care physician, 1 nephrologist and 1 decision-maker.

Within the 8 topic areas, the following content suggestions were ranked the highest (≥ 10 dots): understanding chronic kidney disease: basic information about kidneys, chronic kidney disease and disease progression; diet: reliable information on diet requirements for chronic kidney disease and comorbidities, renal-friendly foods; finances: affordability of medication, equipment, food, financial resources and planning; medication: common medications, adverse effects, indications, cost and coverage; symptoms: types, management; travel: limitations, insurance, access to health care, travel checklists; mental and physical support: screening and supports to address mental health, cultural sensitivity, adjusting to new normal; and work/school: support to help integrate, restrictions (Table 2).

Table 2:

Chronic kidney disease self-management topics and features of electronic health tool, with content suggestions and corresponding dot counts

| Variable | Priority | Content suggestions | Dot count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic* | |||

| Understanding chronic kidney disease | High | Basic information about chronic kidney disease

|

20 |

| Basic information about kidneys and what they do | 17 | ||

| How to slow progression | 15 | ||

| Medium | Where to find credible and reliable information on chronic kidney disease | ||

| Low | How to prevent chronic kidney disease | 2 | |

| Timing of symptoms in relation to chronic kidney disease progression | 1 | ||

| Learning new skills to manage chronic kidney disease | 1 | ||

| Fertility and family planning | 0 | ||

| Diet | High | Reliable information on diet and nutritional requirements | 18 |

| Dietary changes required for chronic kidney disease and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes) | 17 | ||

| Renal-friendly/-unfriendly foods (what to eat/not to eat) | 15 | ||

| Medium | How to read food labels | 7 | |

| Meal planning (e.g., how to make modifications) | 7 | ||

| Low | Diet-tracking tools | 2 | |

| How to identify renal-friendly food that is affordable | 2 | ||

| Cooking classes | 0 | ||

| Symptoms | High | How to manage symptoms and when to seek help | 18 |

| What the symptoms of chronic kidney disease are, what causes them, what to expect as chronic kidney disease progresses | 14 | ||

| When to act on symptoms, severity of symptoms | 12 | ||

| Considerations for comorbidities and impact of treatment for other conditions | 11 | ||

| Medium | Fatigue | 6 | |

| Symptom expectations | 6 | ||

| Low | How to slow progression of symptoms | 2 | |

| Lack of symptoms (“silent disease”) | 1 | ||

| Medications | High | Common medications for chronic kidney disease, adverse effects to watch for and how to manage them | 22 |

| Indications for medications | 20 | ||

| Cost, coverage, insurance for medications | 18 | ||

| Medium | Long-term use of medications and implications | 4 | |

| Low | Medication interactions | 3 | |

| Interactions between Western and alternative therapies | 2 | ||

| How to facilitate pill-taking | 0 | ||

| Medication diary | 0 | ||

| Mental and physical health | High | Recognition of mental health issues as a symptom of chronic kidney disease | 19 |

| Support for patients and broader circle (e.g., family, caregivers) for mental and physical wellness | 13 | ||

| Recognition of cultural sensitivity | 11 | ||

| Screening for depression | 10 | ||

| Addressing how to adjust to “new normal” | 10 | ||

| Medium | Resources and support for mental health issues (e.g., anxiety, guilt, coping with burden) | 5 | |

| Finances | High | Affordability and accessibility of medications, equipment, food | 23 |

| Financial coverage and resources | 22 | ||

| Long-term financial planning | 21 | ||

| Low | Budgeting | 2 | |

| Travel | High | Travel limitations | 18 |

| Travel insurance | 17 | ||

| Accessing health care abroad | 14 | ||

| What to bring on work/leisure trips | 10 | ||

| Medium | Medications for travel/letter of support | 7 | |

| Travel to appointments and how to minimize travel burden | 5 | ||

| Low | Support for caregiver travel | 1 | |

| Volunteer drivers and supported transit | 1 | ||

| Work and school | High | Accommodating work/school environment | 18 |

| Integrating diet and medications into lifestyle (e.g., work and school environment) | 16 | ||

| Supports and considerations for returning to work/school | 15 | ||

| Restrictions for work/school | 11 | ||

| Low | Arranging for respite | 1 | |

| Features of electronic health tool | High | Pictures and visuals | 15 |

| Ability to enter and track health information | 13 | ||

| Accessible/“on-the-go” access to information | 12 | ||

| Links to resources | 12 | ||

| Ability to interact virtually with health care team | 12 | ||

| Access to electronic personal health information | 12 | ||

| Medium | Matrix style (ability to drill down to more detailed information) | 9 | |

| Simple tool | 9 | ||

| Ability to build own profile | 9 | ||

| Quick tips and tools | 8 | ||

| Online chat group | 8 | ||

| Caregiver section | 7 | ||

| Multimedia format (multiple features) | 7 | ||

| Regular updates | 6 | ||

| Reminders, alerts | 6 | ||

| Secure messaging | 6 | ||

| Privacy considerations | 5 | ||

| Low | Multiple languages | 4 | |

| Mobile app | 3 | ||

| Information organized by disease stage | 3 | ||

| Different sensory needs (e.g., visual, hearing) acknowledged | 2 | ||

| Reliable, credible information | 2 | ||

| Ability to download or save content | 2 | ||

| Searchable feature | 2 | ||

| Personal/patient stories | 2 | ||

| Stage of readiness to learn considered | 2 | ||

| Virtual coach | 2 | ||

| Tinder-like application | 1 | ||

| Favourites option | 1 | ||

| Print feature | 1 | ||

| Forum to submit questions | 1 | ||

| Filters | 1 | ||

| Podcasts/audio files | 1 | ||

| Hierarchical format | 0 | ||

| Ability to share calendar | 0 | ||

| Decision aids | 0 | ||

| Help feature (tool-use training) | 0 | ||

Topics were not ranked.

Generally, participants indicated that the e-health tool should be interactive, with multimedia (e.g., text, images, graphics) components. Preferred features included visuals, the ability to enter and track health information and interact with health care providers, on-the-go access, links to resources and access to personal health information. In the large-group discussion, there was support for features that were ranked as medium priority. These included a matrix visual (i.e., set of cells that contain visual and textual elements for users to choose from) versus a list of topics, as well as a layering feature by which users can “drill down for specifics” (i.e., go through content step by step based on their needs).

Respondent comments 4 weeks after the workshop validated the findings, with no changes required.

Workshop satisfaction survey

All participants completed the workshop satisfaction survey. Most (> 95%) strongly agreed that the workshop goal was clear, the material was well-organized and the facilitators were knowledgeable. Twenty-three participants (96%) strongly agreed that the personas aided in topic discussions. Participant comments included “Personas great because I related with all of them,” “Personas, excellent way to focus the conversations and gain multiple perspectives” and “Personas were great in aiding with workshop objectives.”

Interpretation

Our patient-oriented research study showed how patient partners are able to provide important input to study processes. This input included the creation of personas to engage participants at a consensus workshop and the use of those personas to determine preferences for content and features for a self-management e-health tool for patients with chronic kidney disease. The output from the consensus workshop was to identify key subject matter for 8 predetermined topic areas and feature elements relevant for a chronic kidney disease self-management e-health tool.

There is limited literature on the cocreation of personas with patient partners for health research. The persona-based methodology has been described in the medical informatics literature13 and has been studied by a handful of health researchers.14,15 Those studies suggest that personas are useful in informing the design and implementation of health technologies. Using a multimethod structured approach and including patient partners and research team members in all aspects of the current project enabled us to capture and present the broad self-management needs of both patients and caregivers. The multidimensional personas allowed participants to critically reflect on how patients with chronic kidney disease or caregivers think, feel and behave. In the context of self-management, the personas demonstrated life complexities for both patients and caregivers, along with issues that determine a person’s ability to engage in managing chronic kidney disease and living with a chronic disease. The personas were an effective tool to advocate for patients and caregivers, facilitate communication among workshop participants and provide rich descriptions of otherwise complex scenarios in order to prioritize content and features for an e-health tool.

The consensus workshop allowed us to capture unique details around the broad topic areas to support chronic kidney disease self-management and identify preliminary features for an e-health tool. Compared to other techniques (e.g., focus groups, surveys), the dot democracy approach was efficient and created a receptive environment, enabling all workshop participants to participate equally. The content items identified for each topic area are similar to those from prior literature reviews, including information about understanding chronic kidney disease, medications, lifestyle modification and dietary advice.16,17 We also considered additional needs that patients and caregivers have identified as important for self-management,5 including travel, work/school, finances, symptoms, and mental and physical support, as well as features of an e-health tool. Through the consensus workshop, we were able to delve into specifics for each of these areas and identify preferences for information and resources that should be considered.

Limitations

The majority of participants were recruited through the Can-SOLVE CKD Network and were past participants from our previous studies, which suggests that they may be more engaged in self-management. Our findings may not be reflective of the preferences of the broader population. Although the personas were comprehensive, they may not have represented a variety of demographic and biopsychosocial characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease and caregivers. In addition, all our participants were English speaking, and most were women with postsecondary education. The results may not be applicable to people who do not possess these characteristics. Finally, social desirability (e.g., peer pressure) may have played a factor in the final preferences.

Lessons learned from patient engagement

Our findings are grounded in the experiences of our patient partners, who had varying levels of lived experience with chronic kidney disease and of knowledge and skills with research-related activities. We used strategies and contextual factors to help ensure that their experiences and skills were included. Our patient partners were involved in the research processes of previous studies for this multiphase research project, which ensured that they were integral in decision-making along the way. Meaningful recognition through shared power and meaningful collaboration through face-to-face team meetings and informal one-on-one talks were fundamental to mutual learning. Ultimately, patient partner engagement will continue to inform this multiphase project, with the aim of achieving a positive impact on the quality of life and health care for patients with chronic kidney disease.

Conclusion

Our study illustrates success using personas in a consensus workshop to determine preferences for content and features of an e-health tool to support chronic kidney disease self-management. The use of personas could be applied to other applications in patient-oriented research exploring patient preferences and needs in order to improve care and relevant outcomes. The output from the consensus workshop will inform further codevelopment of a self-management e-health tool for patients with chronic kidney disease through continued patient engagement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, caregivers and health care providers from across Canada who participated in the study. They also thank Sarah Gil and Sarah Baay, who assisted in the consensus workshop planning.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Matthew James reports grants from Amgen Canada, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Maoliosa Donald, Brenda Hemmelgarn, Meghan Elliott, Juli Finlay and Helen Tam-Tham acquired the data. Maoliosa Donald and Brenda Hemmelgarn analyzed and interpreted the data. Maoliosa Donald drafted the manuscript. All of the authors conceived and designed the study, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work is a project of the Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease [Can-SOLVE CKD] Network, which is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research grant 20R26070.

Disclaimer: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; data collection, analysis and interpretation; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E713/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemmelgarn BR, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:847–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havas K, Douglas C, Bonner A. Meeting patients where they are: improving outcomes in early chronic kidney disease with tailored self-management support (the CKD-SMS study) BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:279. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-1075-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donald M, Beanlands H, Straus S, et al. Identifying needs for self-management interventions for adults with CKD and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74:474–82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donald M, Gil S, Kahlon B, et al. Overview of self-management resources used by Canadian chronic kidney disease clinics: a national survey. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5 doi: 10.1177/2054358118775098. 2054358118775098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin A, Adams E, Barrett BJ, et al. Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD): form and function. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5 doi: 10.1177/2054358117749530. 2054358117749530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donald M, Kahlon BK, Beanlands H, et al. Self-management interventions for adults with chronic kidney disease: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019814. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baay S, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, et al. Understanding adults with chronic kidney disease and their caregivers’ self-management experiences: a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2019;6 doi: 10.1177/2054358119848126. 2054358119848126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dot-voting. Wikipedia; [accessed 2019 Feb 11]. [updated 2018 Oct 19]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-voting. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miaskiewicz T, Kozar KA. Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Des Stud. 2011;32:417–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeRouge C, Ma J, Sneha S, et al. User profiles and personas in the design and development of consumer health technologies. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:e251–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vosbergen S, Mulder-Wiggers JM, Lacroix JP, et al. Using personas to tailor educational messages to the preferences of coronary heart disease patients. J Biomed Inform. 2015;53:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valaitis R, Longaphy J, Nair K, et al. Persona-scenario exercise for codesigning primary care interventions. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:294–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Howell M, et al. Educational interventions for patients with CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:353–70. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havas K, Bonner A, Douglas C. Self-management support for people with chronic kidney disease: patient perspectives. J Ren Care. 2016;42:7–14. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.