miR-23~27~24 regulates TFH cells through targeting multiple genes including TOX, a key transcription factor for TFH cell biology.

Abstract

Follicular helper T (TFH) cells are essential for generating protective humoral immunity. To date, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as important players in regulating TFH cell biology. Here, we show that loss of miR-23~27~24 clusters in T cells resulted in elevated TFH cell frequencies upon different immune challenges, whereas overexpression of this miRNA family led to reduced TFH cell responses. Mechanistically, miR-23~27~24 clusters coordinately control TFH cells through targeting a network of genes that are crucial for TFH cell biology. Among them, thymocyte selection–associated HMG-box protein (TOX) was identified as a central transcription regulator in TFH cell development. TOX is highly up-regulated in both mouse and human TFH cells in a BCL6-dependent manner. In turn, TOX promotes the expression of multiple molecules that play critical roles in TFH cell differentiation and function. Collectively, our results establish a key miRNA regulon that maintains optimal TFH cell responses for resultant humoral immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, a specialized T cell subset known as follicular helper T (TFH) cells has been under intense scrutiny for their crucial role in helping B cells mount effective humoral immune responses (1, 2). Inside the B cell follicles, the interaction between TFH and B cells via many different receptor/ligand pairs leads to the formation of the germinal center (GC) and the subsequent generation of high-affinity antibody (Ab)–producing plasma cells and long-lived memory B cells. Defects in TFH cell differentiation or function could severely compromise or even completely abolish GC responses, resulting in the loss of protective humoral immunity to harmful pathogens. On the other hand, aberrant GC reactions caused by dysregulated TFH cell responses would also lead to the development of many autoimmune disorders. Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that govern the differentiation and function of TFH cells is immensely important to human health so that better strategies may be developed to induce stronger immune responses against infection and to attenuate unwanted autoimmunity through targeting this specific T cell subset.

The discovery of B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), as a master transcription regulator for TFH cell differentiation, provided the key to studying the complex biology of this cell population (3–5). Expression of BCL6 is induced and maintained in T cells receiving sequential inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS) signals through interacting with dendritic and B cells (6). Upon induction, BCL6 ensures the development of TFH cells through antagonizing the differentiation of other helper T cell lineages while instructing TFH cells to express the appropriate chemotactic receptors enabling them to migrate into B cell follicles and GCs (7). Although BCL6 is necessary to maintain the expression of CXCR5, a defining feature of TFH cells, the initial up-regulation of CXCR5 in TFH cells was shown to be BCL6 independent and that achaete-scute complex-like 2 (ASCL2), a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, is required to promote CXCR5 expression (8). Similarly, the production of interleukin-21 (IL-21), a key TFH cell–secreted cytokine critical for both GC formation and proper TFH cell development, was driven by another ICOS-inducing transcription factor, c-MAF (9, 10). Like ASCL2 and c-MAF, many other transcription factors have also recently been shown to play important roles in regulating different aspects of TFH cell biology (2). Together, these studies demonstrate the complex nature of TFH cell differentiation processes and suggest that TFH cells are coordinately controlled by multiple transcription factors.

In addition to transcriptional regulation, it is now well appreciated that development and effector functions of the immune system are also regulated posttranscriptionally, particularly by a class of short regulatory noncoding RNAs, so-called microRNAs (miRNAs) (11). To date, several miRNAs have been studied for their roles in either promoting or restricting TFH cell responses (12). Previously, we have identified miR-23~27~24 clusters as a main miRNA family in regulating T cell immunity (13–15). However, their role in controlling TFH cell responses has yet to be determined. Here, by using both loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches, we show that loss of miR-23~27~24 clusters in T cells results in elevated frequencies of TFH and GC B cells upon different immunological challenges, whereas T cell–specific overexpression of this miRNA family led to reduced TFH cell responses. Mechanistically, members of the miR-23~27~24 family cooperatively repress both known [e.g., T cell factor 1 (TCF1) (15–17) and c-REL (9, 14)) as well as previously uncharacterized targets [e.g., c-MAF, ICOS, and IL-21 (9)] that play critical roles in controlling multiple aspects of TFH biology. Moreover, we demonstrate that a newly identified miR-23~27~24 target, thymocyte selection–associated HMG-box protein (TOX), functions as a central transcription regulator in TFH cells. Ectopic expression of TOX in T cells increased TFH cell numbers, while reduction of TOX impaired TFH cell responses. The elevated expression of TOX in TFH cells is driven by BCL6 in both mouse and human. In turn, TOX was able to promote expression of multiple molecules including TCF1, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) that are crucial for TFH cell biology. Together, our results establish a key miRNA regulon that ensures optimal TFH cell responses for resultant humoral immunity. Moreover, our study of the miR-23~27~24–mediated gene regulation allows us to find a novel molecular player, TOX in controlling TFH cell differentiation and function.

RESULTS

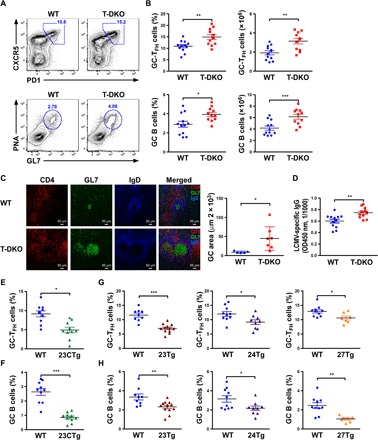

Elevated humoral immune responses in mice with T cell–specific deletion of the miR-23~27~24 family

Recently, we and others have demonstrated that the miR-23~27~24 family (including both miR-23a~27a~24-2 and miR-23b~27b~24-1 clusters) restricts T helper 2 (TH2) responses during airway allergic reaction (13, 18). In addition to the augmented production of allergenic immunoglobulin E (IgE) as previously reported, upon asthma induction, we could also detect increased total serum IgG levels and observed considerably more and larger GCs with elevated numbers of infiltrating TFH cells in the spleens of mice with T cell–specific deletion of miR-23~27~24 clusters (T-DKO) (fig. S1, A and B). Consistent with these findings, allergen-sensitized T-DKO mice harbored significantly increased frequencies and numbers of both TFH cells and GC B cells, suggesting that the miR-23~27~24 family could also play an important role in regulating TFH cell responses and the resultant humoral immunity (fig. S1, C and D). To further examine this possibility, we sought to study TFH cells in mice in the context of acute infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). It has been well established that upon LCMV infection, mice develop strong LCMV-specific TFH cell responses and that defects in TFH cell frequencies result in failure to control this pathogen (3, 19). While T-DKO mice appeared to harbor normal numbers of TFH and GC B cells in the absence of any immune challenge in young age, similar to what we have shown in the asthmatic condition, upon LCMV infection elevated total and LCMV-specific TFH cell responses, along with clear increases in GC B cell frequencies and numbers, were easily detected in T-DKO mice (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S2). Supporting these findings, we also detected heightened GC responses with increased numbers of infiltrating TFH cells in the spleens of LCMV-infected T-DKO mice (Fig. 1C). Consequently, T-DKO mice produced substantially greater amounts of LCMV-specific Abs compared to their wild-type (WT) littermates upon LCMV infection (Fig. 1D and fig. S3). It should be noted that the miR-23~27~24 family regulates TFH cell responses not only in a T cell–intrinsic manner but also in a TFH cell–intrinsic manner. To this end, significantly increased frequencies of CXCR5+BCL6+ GC-TFH cells could be detected in T cells devoid of miR-23~27~24 clusters in mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice where BM cells from T-DKO mice or WT littermates were mixed with BM cells from congenically marked Ly5.1+ B6 mice at a 1:1 ratio into irradiated Rag1-deficient mice (fig. S4). Further supporting the TFH cell–intrinsic role of miR-23~27~24 clusters in controlling TFH cell responses, we have detected elevated expressions of the entire miR-23~27~24 family in TFH cells similar to what was reported about miR-146a, another miRNA that is highly up-regulated in TFH cells to limit their responses (fig. S5) (20). Last, the finding from our mixed BM chimeras study also suggested that the aberrant TFH cell and GC B cell responses observed in T-DKO mice did not result from impaired regulatory T (Treg) cell–mediated immune regulation, although the role of the miR-23~27~24 family in Treg cells has been previously implicated (13, 14).Consistently, LCMV-infected mice with Treg cell–specific deletion of the miR-23~27~24 family (Treg-DKO) harbored equivalent numbers of TFH and GC B cells compared to their WT littermates (fig. S6).

Fig. 1. Members of the miR-23~27~24 family collaboratively limit TFH cell responses.

(A) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses, (B) frequencies and numbers of CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells and PNA+GL7+ GC B cells in the spleen from ~8-week-old T-DKO mice or their WT littermates 8 days after LCMV infection. (C) Immunohistological analyses of GC reactions in LCMV-infected spleen that were cryocut and stained with CD4 (red), GL7 (green), and IgD (blue). (D) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analyses of total serum LCMV-specific IgG levels from LCMV-infected T-DKO mice or WT littermates. OD450 nm, optical density at 450 nm. Frequencies of (E) CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells and (F) PNA+GL7+ GC B cells in the spleen from ~8-week-old 23CTg mice or their WT littermates 8 days after LCMV infection. Frequencies of (G) CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells and (H) PNA+GL7+ GC B cells in the spleen from ~8-week-old 23Tg, 24Tg, or 27Tg mice and their corresponding WT littermates 8 days after LCMV infection. Data are representative of three to four independent experiments. Each symbol represents a mouse, and the bar represents the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Individual miR-23~27~24 family members collaboratively regulate TFH cell responses

Individual members of the miR-23~27~24 family were previously shown to antagonize each other to fine-tune the responses of other T cell lineages (13, 15). To determine the impact of individual miR-23~27~24 family members on TFH cells, we took advantage of the mice that we previously generated in which the whole miR-23a~27a~24-2 cluster (23CTg) or individual members (23Tg, 24Tg, or 27Tg) were selectively overexpressed in T cells (13). In contrast to the enhanced TFH cell responses seen in T-DKO mice, LCMV-infected 23CTg mice harbored reduced TFH cell frequencies along with diminished GC B cell responses (Fig. 1, E and F, and fig. S7). Further analysis in 23Tg, 24Tg, and 27Tg mice revealed that, unlike other T cell lineages, TFH cell responses are collaboratively controlled by the entire miR-23~27~24 family, as mice with T cell–specific overexpression of individual miR-23~27~24 family members all exhibited compromised TFH cell and GC B cell responses upon LCMV infection (Fig. 1, G and H).

miR-23~27~24 clusters target multiple genes associated with TFH cell biology

To date, many targets of the miR-23~27~24 family have been identified as contributors to the regulatory effects on different aspects of T cell immunity (13–15, 18). While the impact of miR-23~27~24 family–mediated gene regulation on TFH cells has not been previously studied, several previously identified targets were known to regulate TFH cell biology. For example, TCF1, a transcription factor that is targeted by miR-24 to promote TH1 and TH17 effector function, was recently demonstrated to be crucial for establishing the transcriptional program of TFH cells (16, 17). It is therefore possible that miR-24 could control TFH cells through modulating the amount of TCF1. Similarly, in addition to the reported role of c-REL in miR-27–mediated regulation of Treg cell differentiation and homeostasis (14), miR-27 could also limit TFH cell responses by targeting c-REL as it was previously shown to promote the generation and function of TFH cells through driving the expression of IL-21 and CD40L (21, 22). Nevertheless, it remains unclear as to how miR-23 regulates TFH cells. Moreover, to ensure their biological impact, it is also likely that the miR-23~27~24 family controls TFH cell biology through targeting multiple genes required for the differentiation and function of TFH cells similar to the way they regulate TH2 immunity (13, 18).

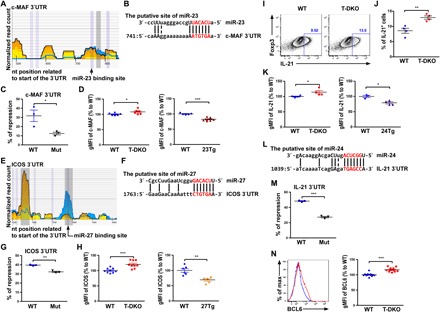

To search for new targets that could account for miR-23~27~24 family–mediated regulation of TFH cell responses, we took advantage of a previously reported high-throughput sequencing of RNAs isolated by cross-linking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) database generated in in vitro activated CD4+ T cells (23). As miRNAs direct Argonaute (AGO) proteins to posttranscriptionally repress their mRNA targets, through searching miRNA seed matches within the HITS-CLIP–identified AGO-bound regions, we have identified TFH cell–associated genes with putative bindings of miR-23, miR-24, or miR-27. Next, by performing luciferase reporter assays and/or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, the direct regulatory effects on those potential targets from this miRNA family were examined. As shown in Fig. 2 (A to D), we have identified c-MAF as a direct miR-23 target. It has been previously shown that c-MAF induced by ICOS signaling promotes TFH cell differentiation and function by inducing IL-21 production (9). Therefore, miR-23 could contribute to TFH cell regulation through targeting c-MAF. Moreover, our studies also revealed that ICOS itself could be directly repressed by miR-27, thus adding ICOS as another miR-27 target that is involved in TFH cell differentiation (Fig. 2, E to H). Considering the fact that both ICOS and c-MAF are regulated by the miR-23~27~24 family, it is expected that significantly more IL-21–producing T cells, with increased expression of IL-21 on a per-cell basis, were detected in T-DKO mice compared with their WT littermates (Fig. 2, I to K). Further analysis of IL-21 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) revealed a putative miR-24 binding site despite having no positive AGO binding signal from the HITS-CLIP analysis (Fig. 2L). Nevertheless, our luciferase reporter assay confirmed that miR-24 can indeed directly repress IL-21 (Fig. 2M), suggesting that minimal IL-21 expression in T cells used for the HITS-CLIP study might likely be responsible for the lack of positive readings (23). Last, as both ICOS and IL-21 signaling have been previously shown to induce BCL6 expression (4, 6), although BCL6 itself is not a direct target of this miRNA family, T-DKO TFH cells expressed significantly increased BCL6 amount on a per-cell basis compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 2N). Thus, despite the observation that the regulatory effect of the miR-23~27~24 clusters on each target did not appear to be large, members of this miRNA family can control the expression of BCL6 and the TFH cell differentiation program by cooperatively regulating a network of genes crucial for TFH cell biology.

Fig. 2. Multiple TFH cell–associated genes are targeted by the miR-23~27~24 family.

(A) HITS-CLIP analysis and (B) sequence alignment of putative miR-23 site in the 3′UTR of c-MAF. (C) Ratios of repressed luciferase activity of cells in the presence of c-MAF 3′UTR with or without mutations in the seed sequences in the presence of miR-23 compared with cells transfected with control miRNA. (D) Percentage of c-MAF geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) in CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells from T-DKO or 23Tg mice over WT littermates. (E) HITS-CLIP analysis and (F) sequence alignment of the putative miR-27 site in the 3′UTR of ICOS. (G) Ratios of repressed luciferase activity of cells in the presence of ICOS 3′UTR with or without mutations in the seed sequences in the presence of miR-27 compared with cells transfected with control miRNA. (H) Percentage of ICOS gMFI in CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells from T-DKO mice or 27Tg mice over WT littermates. (I) FACS analysis, (J) frequencies, and (K) percentage of IL-21 gMFI in in vitro–activated CD4+ T cells from T-DKO or 24Tg mice over WT littermates. (L) Sequence alignment of the putative miR-24 site in the 3′UTR of IL-21. (M) Ratios of repressed luciferase activity of cells in the presence of IL-21 3′UTR with or without mutations in the seed sequences in the presence of miR-24 compared with cells transfected with control miRNA. (N) FACS analysis and percentage of BCL6 gMFI in CXCR5+PD1+TFH cells from T-DKO or 24Tg mice over WT littermates. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Each symbol represents a mouse or cell sample, and the bar represents the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. nt, nucleotide.

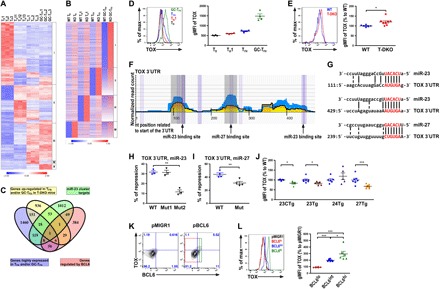

TOX, a target of miR-23 and miR-27, is highly up-regulated in TFH cells by BCL6

Having elucidated the miR-23~27~24 family targets that are known for their roles in TFH cells, we next sought to explore whether this miRNA family could control TFH cell responses through regulating genes that have yet to be associated with TFH cell biology. To this end, we first performed transcriptome analysis of four populations of T cells including CD44−CD4+ naïve T cells (Tn), CD44+PSGL1hiCXCR5−CD4+ T cells (TH1), CD44+PSGL1intCXCR5+CD4+ T cells (TFH), and CD44+PSGL1loCXCR5+CD4+ T cells (GC-TFH) isolated from LCMV-infected T-DKO mice or WT littermates as described previously (fig. S8) (16). Genes that were specifically up-regulated in TFH and/or GC-TFH were selected for further analysis (clusters III, IV, and V in Fig. 3A and tables S1 to S3). Next, to identify the miR-23~27~24 family targets in TFH cells, we first examined genes that are significantly up-regulated in T cells devoid of the miR-23~27~24 family–mediated repression. As shown in Fig. 3B, more genes were found to be up-regulated in TFH and GC-TFH cells compared to Tn and TH1 cells isolated from T-DKO mice, which is in agreement with the observed role of this miRNA family in restricting TFH cell responses (clusters I and II; tables S4 and S5). Since this list of genes also includes ones that were indirectly repressed by this miRNA family, an unbiased analysis of the aforementioned HITS-CLIP results was further performed to identify all genes that could be directly recognized by the miR-23~27~24 family (tables S6 to S8). Last, given that BCL6 serves as a defining transcriptional regulator of TFH cells (7, 24), we reasoned that genes directly targeted by BCL6 are likely to be more functionally relevant in regulating TFH cell biology and so were included in our final analysis. Together, through performing Venn diagram analysis on our generated RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) results combined with the aforementioned HITS-CLIP analysis on putative miR-23~27~24 family binding sites and a publically available chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) study on BCL6-bound genes in mouse TFH cells (24), Tox was revealed to be the only overlapping gene in all four datasets (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. miR-23 and miR-27 jointly repress TOX, a transcription factor that is highly up-regulated by BCL6 in TFH cells.

(A) RNA-seq analysis of genes that were differentially expressed in Tn1, TH1, TFH, and GC-TFH cells isolated from WT B6 mice 8 days after LCMV infection. (B) Genes that were up-regulated in different T-DKO T cell subsets compared to their corresponding WT counterparts were shown. (C) Venn diagram analysis of genes enriched in TFH and/or GC-TFH cells, further up-regulated in T-DKO TFH and/or GC-TFH cells, containing putative targets of the miR-23~27~24 family by HITS-CLIP and bound by BCL6 in TFH cells. FACS analysis and gMFI of TOX protein amounts in (D) different T cell subsets from WT B6 mice or (E) PSGLloCXCR5+ GC-TFH cells from T-DKO mice or WT littermates. (F) HITS-CLIP analysis and (G) sequence alignment of putative miR-23 and miR-27 sites in the 3′UTR of TOX. Ratios of repressed luciferase activity of cells in the presence of TOX 3′UTR with or without corresponding mutations in the seed sequences in the presence of (H) miR-23 or (I) miR-27 compared with cells transfected with control miRNA. (J) gMFI of TOX protein amounts in PSGLloCXCR5+ GC-TFH cells from 23CTg, 23Tg, 24Tg, or 27Tg mice and their corresponding WT littermates. (K) FACS analysis of TOX protein expression in BCL6-deficient T cells transduced with BCL6-expressing or control retroviral vectors. Cells that expressed different BCL6 amounts (lo, int., or hi) were individually gated. (L) FACS analysis and percentage of TOX gMFI in BCL6 lo, int., and hi populations from BCL6-reexpressing T cells over T cells transduced with control vector were shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Each symbol represents a mouse or cell sample, and the bar represents the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

TOX, a member of a larger HMG-box superfamily, is known to be crucial for CD4+ T cell development in the thymus (25). In the periphery, however, its role in CD4+ T cells has yet to be defined. To this end, we first confirmed our RNA-seq results by examining the TOX protein levels in various T cell subsets. Consistent with our RNA-seq results, we found that TOX was expressed at low levels in both Tn and TH1 cells but was induced in TFH cells and further up-regulated in GC-TFH cells (Fig. 3D). Moreover, TFH cells from T-DKO mice also expressed more TOX compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 3E). In addition, in agreement with the results from the HITS-CLIP analysis (Fig. 3F), our luciferase reporter data demonstrated that Tox can be directly repressed by miR-23 and miR-27 despite the fact the first miR-23 binding site did not seem to be functional (Fig. 3, G to I). In further support of these findings, diminished TOX protein expression on a per-cell basis could be detected in TFH cells with overexpression of miR-23 alone, miR-27 alone, or the entire miR-23~27~24 family but not in cells with overexpression of miR-24 (Fig. 3J and fig. S9). Last, to confirm that the expression of TOX is indeed regulated by BCL6 as suggested by a previous report (24), we retrovirally introduced BCL6 into BCL6-ablated CD4+ T cells (tamoxifen-treated T cells isolated from CD4Ert2creBcl6fl/fl mice) and examined TOX expression. As shown in Fig. 3 (K and L), not only did the reexpression of BCL6 lead to TOX induction, but the amounts of TOX also showed a positive correlation with the amounts of BCL6 in cells. Together, we identified TOX as a novel target of miR-23 and miR-27 that is highly up-regulated in TFH cells in a BCL6-dependent manner.

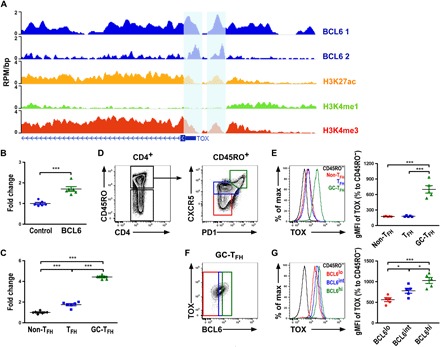

The BCL6-TOX axis is conserved in human TFH cells

While many cell differentiation programs and functional features are shared between murine and human TFH cells, the differences in TFH cells between these two species are also well recognized (26). Therefore, it is uncertain whether our finding of the BCL6-TOX axis in mouse TFH cells is also conserved in the human counterpart. Previously, a ChIP-seq study on BCL6-bound cis-regulatory regions with transcriptome and epigenome analysis in human primary tonsillar GC-TFH cells was conducted to examine the impact of BCL6 on human TFH cell biology (7). In this study, two significant BCL6 bindings to the promoter region of the TOX locus in GC-TFH cells were identified, a result that we have confirmed by reanalyzing this dataset (Fig. 4A). These bindings occur along with the apparent enrichment of H3K27ac and H3K4me3, a signature characteristic of actively transcribed genes (Fig. 4A). While BCL6 is normally considered to function as a transcriptional repressor, our analysis of the aforementioned gene expression profiling study in human CD4+ T cells clearly demonstrated an increase in TOX expression in cells with enforced BCL6 expression (Fig. 4B) (7). Moreover, consistent with our findings in mice, the highest levels of TOX expression were found in human GC-TFH cells compared to the non–TFH cell population with TFH cells exhibiting intermediate TOX transcript levels (Fig. 4C). Last, we sought to examine TOX protein levels in human CD4+ T cells. Consistent with our findings in the mouse study, in human lymph nodes, we have observed the highest amount of TOX in CD45RO+CXCR5hiPD1hiCD4+GC-TFH cells compared to those in TFH and non-TFH cells (Fig.4, D and E). Moreover, within the GC-TFH cell population, a significant increase in TOX protein expression proportionally to the amounts of BCL6 was also detected (Fig. 4, F and G).Thus, the BCL6-TOX axis in TFH cells is conserved between human and mice and likely other species.

Fig. 4. BCL6 targets TOX in human TFH cells.

(A) ChIP-seq analysis of BCL6 (two replicates) or histone H3 acetylated at Lys27 (H3K27ac), monomethylated at Lys4 (H3K4me1), or trimethylated at Lys4 (H3K4me3) with input controls at TOX in human GC-TFH cells presented as reads per million per nucleotide (RPM/bp). Previously identified BCL6-positive bindings were marked. Fold changes of TOX expression in (B) T cells transduced with BCL6-expressing lentiviral vector compared to non-TFH cells or T cells transduced with control vector and in (C) human non-TFH, TFH, or GC-TFH cells, respectively. FACS analysis of (D) CD4+CD45RO− T cells and CD4+CD45RO+ T cells from human lymph nodes (LNs). CXCR5hiPD1hi GC-TFH, CXCR5intPD1intTFH, and CXCR5−PD1− non-TFH cells (in CD4+CD45RO+ T cells) were gated for (E) FACS analysis, and percentages of TOX gMFI over CD4+CD45RO− T cells are shown. (F) CXCR5hiPD1hi GC-TFH cells that expressed different BCL6 amounts (lo, int., or hi) were individually gated. (G) FACS analysis and percentage of TOX gMFI in BCL6 lo, int., and hi populations from CD4+CD45RO+CXCR5hiPD1hi GC-TFH cells over CD4+CD45RO− T cells are shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Each symbol represents a human donor, and the bar represents the mean. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.01.

Modulation of TOX levels in T cells affects TFH cell responses

Given that TOX is induced in TFH cells by BCL6, we next sought to determine whether TOX plays a functional role in regulating TFH cell responses in vivo. To this end, we first transduced CD4+ T cells isolated from SMARTA mice (which express an I-Ab–restricted T cell receptor specific for LCMV glycoprotein amino acids 66 to 77) with a retroviral vector expressing a short hairpin RNA specific for TOX (shTOX) along with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter (27). Expression of shTOX in SMARTA CD4+ T cells resulted in a small but appreciable reduction (~25%) of TOX expression (fig. S10A). Next, we transferred sorted shTOX-transduced GFP+Ly5.1+ SMARTA CD4+ T cells into congenically marked Ly5.2+ B6 hosts and analyzed the recipient mice 7 days after acute infection with LCMV. As shown in fig. S10B, we could observe reduced frequencies of SMARTA SLAMloCXCR5+TFH cells or BCL6+CXCR5+ GC-TFH cells in mice receiving SMARTA CD4+ T cells retrovirally transduced with shTOX-expressing vector compared to the ones with pMDH control vector. Moreover, when Tox was disrupted through using a recently established plasmid-based RNA-guided CRISPR system (28), further decreases in both TFH and GC-TFH cells could be observed (Fig. 5, A and B). Next, to further examine the role of TOX in promoting TFH cell responses, we took a gain-of-function approach by retrovirally transducing SMARTA CD4+ T cells with a TOX-expressing GFP reporter containing vector. In contrast to what was shown in the aforementioned TOX loss-of-function study, enforced TOX expression in SMARTA CD4+ T cells led to significantly higher frequencies of both TFH and GC-TFH cells during LCMV infection (Fig. 5, C and D). It should be noted that modulations of TOX amounts in T cells did not seem to affect general T cell homeostasis as similar frequencies of SMARTA+ cells with TOX overexpression or ablation within the total CD4+ T cell population were observed compared to their corresponding controls (fig. S11). Thus, our data clearly demonstrated a cell-intrinsic role of TOX in driving TFH cell responses and that the level of TOX expression needs to be tightly regulated to ensure optimal TFH cell responses.

Fig. 5. Modulation of TOX levels in T cells affects TFH cell responses.

(A) FACS analysis and percentage of TOX gMFI in CD4+ SMARTA T cells electroporated with a Tox guide RNA (gRNA)/Cas9–expressing plasmid over cells transduced with a control plasmid are shown. (B) FACS analysis and frequencies of SLAMloCXCR5+TFH or BCL6+CXCR5+ GC-TFH cells in the B6 recipients transferred with congenically marked GFP+Tox-gRNA+CD4+ SMARTA T cells or control cells 7 days after LCMV infection. (C) FACS analysis and percentage of TOX gMFI in CD4+ SMARTA T cells retrovirally transduced with TOX-expressing vector over cells transduced with control vector are shown. (D) FACS analysis and frequencies of SLAMloCXCR5+TFH cells or BCL6+CXCR5+ GC-TFH cells in the B6 recipients transferred with congenically marked GFP+pTOX+CD4+ SMARTA T cells or control cells 7 days after LCMV infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Each symbol represents a mouse, and the bar represents the mean. ***P < 0.001.

TOX promotes the expression of multiple TFH cell–associated molecules

Recently, a study in CD8+ T cells during central nervous system inflammation suggested that the expression of TOX could confer the tissue-destructive ability to CD8+ T cells through inhibiting the activity of ID2. It was shown that TOX can directly target Id2 and that loss of TOX led to increased Id2 expression in CD8+ T cells (27). Considering the previously reported role of ID2 in restricting TFH cell differentiation (29), we aimed to determine whether TOX could also promote TFH cell responses through repressing Id2. To this end, we examined Id2 mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells retrovirally transduced with the aforementioned TOX-expressing vector. Unexpectedly, despite a clear increase in TOX expression, comparable (if not higher) Id2 expression in TFH cells was observed (fig. S12A), which is seemingly inconsistent with the previous CD8 study (27). It should be noted that, however, while higher levels of Id2 was detected in TOX-deficient CD8+ T cells by the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis in that study (27), opposite results were obtained when their RNA-seq dataset from TOX-deficient and TOX-sufficient CD8+ T cells was reanalyzed (fig. S12B). The latter finding was further supported by another study in which TOX was shown to be crucial for early development of the innate lymphoid cell (ILC) lineage (30). Not only were Tox and Id2 found to be coexpressed in the common ILC progenitors, but loss of TOX also resulted in a significant down-regulation of Id2 expression (fig. S12C). Similar results were also demonstrated in CD4SP thymocytes in which expression of Id2 was significantly decreased in the absence of TOX (31). Together, these results along with our findings in TFH cells argue against a transcriptional repressor role of TOX in regulating Id2 expression and suggest that TOX does not likely promote TFH cells through repressing Id2.

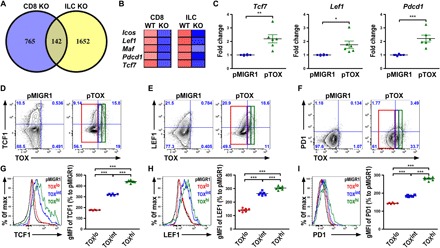

To gain further molecular insights into TOX-dependent TFH cell differentiation, we performed Venn diagram analysis of the aforementioned gene expression profiling studies in CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors (27, 30). We reasoned that the core TOX-dependent genes identified in the datasets generated from two distinct immune cell populations would have a higher probability of being commonly regulated by TOX in TFH cells. To this end, 142 genes were shown to be co-regulated by TOX in both CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors (Fig. 6A and table S9). Among them, five genes (Icos, Lef1, Maf, Pdcd1, and Tcf7) that were previously shown to be critical in TFH cell biology were identified to have significantly lower expression in TOX-deficient cells compared to their corresponding WT counterparts (Fig. 6B) (2). Next, we performed the qPCR analysis to confirm whether the expression of those molecules could also be driven by TOX in CD4+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 6C and fig. S12 (D and E), while expression of Icos and Maf were unaltered in CD4+ T cells with TOX overexpression, significant increases in Tcf7, Lef1, and Pdcd1 expression were easily detected. Moreover, TOX-dependent up-regulation of TCF1 (encoded by Tcf7), LEF1, and PD1 (encoded by Pdcd1) were further supported by the observation of positive correlation between the amounts of TOX and those molecules in TOX-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6, D to I). Together, these data suggest that TOX could promote TFH cell responses through inducing the expression of multiple genes that are critical for TFH cell differentiation and function (16, 32).

Fig. 6. TOX promotes the expression of multiple genes crucial for TFH cell differentiation and function.

(A) Venn diagram analysis of genes that were differentially expressed between TOX-deficient and TOX-sufficient cells in CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors. RNA-seq data for CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors were derived from GenBank under accession GSE93804 and GSE65850, respectively. KO, knockout. (B) TFH-associated genes that were down-regulated in both TOX-deficient CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors (compared to their respective control groups) are shown. (C) qPCR analysis of expression of Tcf7, Lef1, and Pdcd1 in T cells with TOX overexpression. FACS analysis of (D) TCF1, (E) LEF1, and (F) PD1 protein expression in TOX-overexpressing T cells compared to corresponding controls. Cells that expressed different TOX amounts (lo, int., or hi) were individually gated. FACS analysis and percentage of (G) TCF1, (H) LEF1, and (I) PD1 gMFI in TOX lo, int., and hi populations from TOX-overexpressing T cells over control cell populations are shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Each symbol represents a mouse, and the bar represents the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Immune responses are tightly controlled by many different cellular and molecular players. Within a given immune cell type, expression of different sets of genes dictates the outcome of developmental transitions or cellular activation status. Among different transregulators of gene expression, transcription factors and miRNAs are probably the most important and are extensively studied for their roles in not only the immune system but also other biological processes. Unlike transcription factors, miRNAs are generally thought to fine-tune rather than drastically alter the expressions of their targets. Nevertheless, through repressing a set of genes that are in a shared pathway or protein complex, miRNAs can increase their impact on gene regulation and the resultant biology. In this study, we demonstrated that an miRNA family, miR-23~27~24 clusters, can control the differentiation and function of TFH cells, a key T cell subset essential for the generation of protective humoral immunity. While the regulatory effect of the miR-23~27~24 clusters on each target seemed to be modest, this miRNA family regulates TFH cell responses through collaboratively targeting a network of genes including a transcription factor, TOX, whose role in TFH cells has not been previously recognized. TOX and other miR-23~27~24 family targets, in turn, control other critical components crucial for TFH cell biology. Collectively, our work illustrates a coordinated regulation by miRNAs and transcription factors that ensure the production of appropriate immune responses during different immunological challenges.

Previously, our work has already established the miR-23~27~24 clusters as a key miRNA family in controlling T cell immunity (13–15). However, one of the major puzzles in our earlier studies was the notion that individual members in this miRNA family do not seem to work together to regulate a given T cell response. For example, unlike miR-27, which plays a negative role in regulating all T cell lineages, miR-23 appears to be functionally dispensable for controlling TH1 and TH2 immunity (13). On the other hand, while miR-24 limits TH2 cell responses together with miR-27, it actually antagonizes miR-27 on TH1 and TH17 regulation through promoting the production of corresponding effector cytokines (15). The fact that TFH cells but not other T helper cells are collaboratively regulated by all three members suggests that TFH cell responses need to be more tightly controlled. One might question what makes TFH cells more unique than other T helper cell lineages. After all, each T cell subset plays their individual role in protecting the host from various types of pathogens, and dysregulation of any T helper cell responses would lead to corresponding autoimmune diseases. Nevertheless, this is not the first time that differential regulation of different T helper cell subsets has been reported (33). It has been shown that TH2 immunity is more strongly regulated by Treg cells than the TH1 counterpart, as even moderate Treg cell numbers were capable of efficiently quenching a TH2 cell response. Therefore, while the same cellular (e.g., Treg cells) or molecular players (e.g., miR-23~27~24 clusters) can control multiple T cell lineages, they can also preferentially regulate a specific type of T cell response. While the precise reason behind this specialized regulation remains to be clarified, it offers an opportunity to develop targeted therapeutic strategies against a selected disease driven by a given T cell lineage.

TOX was initially characterized as a key transcription factor in thymocyte development. Later, it was shown to play a more specific role in CD4+ T cell development, as mice with TOX deficiency exhibited severely impaired CD4+ T cell development, while the CD8+ T cell compartment was only minimally affected (25). Outside T cell lineages, TOX has also been shown to be critical for the generation of natural killer cells and other ILC subsets (30, 34). Together, these results seemed to indicate a large role of TOX in regulating the development of different immune subsets. Nevertheless, the function of TOX in controlling peripheral effector cell responses has only recently begun to be appreciated (27). One of the most interesting findings in our current study is the identification of TOX as a central transcription regulator in controlling TFH cell differentiation and function. Moreover, elevated expression of TOX in GC-TFH cells (and in TFH cells to a lesser degree) is induced by BCL6 in both human and mice. Considering that BCL6 was previously shown to function mostly as a transcriptional repressor rather than an activator (7), this result is rather unexpected. However, it should be noted that the aforementioned study in BCL6-bound cis-regulatory regions revealed that the bulk of BCL6 binding in GC-TFH cells occurs in promoters enriched in histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac) of actively transcribed genes (7). Therefore, while BCL6 might predominantly repress gene expression, similar to what has been described in FOXP3-mediated gene regulation in Treg cells (35), it could also function as a transcriptional activator for certain targets when forming complexes with different sets of binding partners as suggested previously (7). Nevertheless, it remains probable that BCL6 could still promote Tox expression through repressing other unknown negative regulators of TOX. Further studies are needed to directly test this possibility.

Mechanistically, we initially hypothesized that TOX could promote TFH cell responses through inhibiting Id2 expression as suggested by the aforementioned study in CD8+ T cells (27). However, inconsistent with their findings, our results did not support TOX as a transcriptional repressor in regulating Id2 expression in TFH cells. Moreover, considering the presence of conflicting results in different studies (27, 30, 31), the precise role of TOX on Id2 regulation remains to be further clarified, as TOX might act in a multimodal fashion to activate or repress Id2 expression in a cell type– and context-dependent manner. On the other hand, while TCF1, LEF1, and PD1 were identified to be driven by TOX to promote TFH cell responses, other TOX targets might also be involved in TOX-dependent TFH cell biology. For example, CD40L, a molecule that is vital for TFH cell–B cell interaction during GC responses, has been previously shown to be down-regulated in TOX-deficient CD4SP cells and ILC progenitors (30, 31), but it was not included in our analysis since it was not a differentially expressed gene in TOX-deficient CD8+ T cells (27). Thus, future studies including gene expression profiling and/or ChIP-seq analysis on TOX-regulated genes specifically in TFH cells are crucial to gain further mechanistic insights into TOX-mediated control of TFH cell biology.

We have previously shown that in other T cell subsets, miR-23~27~24 clusters seem to primarily repress their targets at the protein level (13–15). As such, targets whose mRNA expression was unaltered between WT and DKO cells would not be included in the current study. Similarly, considering the central role of BCL6 in orchestrating TFH cell differentiation program, our work focused on the genes that are directly targeted by BCL6. Consequently, genes that are not BCL6 bound but crucial for TFH cell biology, such as ASCL2, would also be excluded from our analysis. Nevertheless, our approaches allowed us to identify TOX as a novel miR-23~27~24 family target that could play a major role in TFH cell regulation by this miRNA family. Together with other targets whose roles have been previously associated with TFH cell biology, our study demonstrates an miRNA regulon that coordinately controls different aspects of TFH cell differentiation and functional program. Nevertheless, further in-depth exploration of this miRNA family–mediated control of TFH cell responses is needed to fully understand how humoral immunity is regulated in many different immunological diseases like autoimmunity and infection where a strong TFH cell–dependent humoral immune response could be either detrimental or beneficial to host health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Through crossing to CD4-cre mice, mice with T cell–specific deletion of miR-23~27~24 clusters (T-DKO) or mice that selectively overexpress the whole miR-23a cluster (23CTg) or individual members (23Tg, 24Tg, and 27Tg) in T cells (13) as well as CD4Ert2cre (36), Bcl6fl/fl (37), and SMARTA mice (38) have been described previously. Treg cell–specific deletion of both miR-23 clusters was achieved by breeding miR-23~24~27a/bfl/fl mice to Foxp3cre mice. C57BL/6J (B6), B6.SJL (Ly5.1+ B6), and Rag1−/−mice were from the Jackson laboratory. All mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen–free conditions. Unless otherwise indicated, 8- to 12-week-old mice of both sexes were used, and only WT littermates of the same gender served as controls in each experiment. Specifically, both cre− flox/flox and cre+-only mice were included as “WT” control mice as they did not show any clear difference in our studies. All mice were maintained and handled in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines of University of California, San Diego and National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

LCMV infection and allergic airway inflammation

LCMV Armstrong viral stocks were prepared and quantified as described previously (19). Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 106 plaque-forming unit (PFU) viruses for GC response study, or 2 × 105 PFU viruses for SMARTA CD4+ T cell transfer study, and were euthanized at day 8 or 7, respectively. Sera were collected for virus-specific Ab measurement. For induction of allergic airway inflammation, mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin (Worthington) as previously described (13).

Generation of mixed BM chimeras

T cell–depleted BM cells isolated from femurs and tibiae of Ly5.2+T-DKO mice or their WT littermates were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with T cell–depleted BM cells taken from Ly5.1+ WT B6 mice (2.5 × 106 each) and intravenously injected into irradiated (950 cGy) Rag1−/− mice. Mice were kept on antibiotic water for 4 weeks. Eight weeks after BM transfer, mice were subjected to LCMV infection studies.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The concentrations of total IgG in serum from asthmatic mouse model were evaluated with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioLegend). For measurement of Ab to LCMV, purified LCMV antigen (0.5 μg/ml) was coated onto a 96-well Costar assay plate (Corning). Plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and serial dilutions of sera in 1% BSA in PBS were applied to the plates and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. After washing, plates were incubated for 2 hours with the horseradish peroxidase–conjugated Ab against total mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and then with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (BioLegend) for color development. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Immunophenotyping and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens by slide mechanical grind. For all FACS analysis, cells were first stained with Ghost Dye Red 780 (Tonbo Biosciences) to exclude dead cells, followed by subsequent staining. Surface staining includes Abs against CD4, CD8α, CD44, PD1, ICOS, CD3ε, B220, GL7, and SLAM (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific), and peanut agglutinin (PNA) (Vector Laboratories). For CXCR5 staining, cells were stained with purified Ab against CXCR5 (BD Biosciences) for 1 hour, followed by staining with biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min, and then surface staining was performed with indicated Abs as well as fluorescence-labeled streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). LCMV-specific CD4+ T cells were stained with a GP66–77:I-Ab tetramer provided by the National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core Facility (Emory Vaccine Center, Atlanta, GA) prior to surface staining. A FOXP3/ Transcription Factor Staining kit was used for intracellular staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Tonbo Biosciences). Intracellular staining of FOXP3, c-MAF, IL-21, TOX (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific), LEF1, TCF1 (both from Cell Signaling Technology), and BCL6 (BD Biosciences) was performed after fixation and permeabilization. For IL-21 detection, FACS-sorted CD4+CD25−CD62Lhi naïve T cells in the spleen from 6- to 8-week-old WT and T-DKO mice were stimulated for 4 days with plated-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 Abs (Bio X Cell), and recombinant IL-6 (PeproTech) (20 mg/ml) in the presence of anti–IL-4 (10 μg/ml) and anti–interferon-γ (Bio X Cell). For human lymphocyte staining, Abs specific against human CD4, CXCR5 and PD1 (BioLegend), and CD45RO (Tonbo Biosciences) were used. Data were collected by BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and evaluated using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC).

Immunostaining

Freshly dissected spleens were rapidly frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (Sakura). Sections 10 μm in thickness were cut with CryoStar NX50 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), attached on glass slides, and fixed in cold acetone for 20 min, followed by air drying. After washing in PBS three times, sections were stained with anti–IgD-PB for labeling the follicular mantle zone, anti–CD4-phycoerythrin (PE) for identifying T cells, anti–GL7–fluorescein isothiocyanate, or anti–IgD–eFluor 450 (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific) for probing the GC region for 30 min at room temperature. Images were acquired on an LSM 700 system (Carl Zeiss Inc.).

Luciferase reporter assay

The 3′UTR regions of ICOS, c-MAF, IL-21, and TOX were amplified from WT mouse genomic DNA and cloned into psiCHECK-2 Vector (Promega). miR-23a, miR-24, miR-27a, and miR-155 sequences were respectively cloned into the pMDH-PGK–enhanced green fluorescent protein retroviral vector. To generate ICOS, c-MAF, IL-21, and TOX 3′UTR mutants, site-directed mutagenesis was performed (Agilent Technologies). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were plated on a 24-well plate 1 day before transfection. psiCHECK-2 bearing WT 3′UTR or corresponding mutant 3′UTR were cotransfected along with a control vector (miR-155) or miR-23~27~24 family miRNA expressing plasmid to HEK293T cells using FuGENE 6 (Promega). Luciferase activities were assessed at 20 hours after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitative real-time PCR

For detecting gene expression levels in BCL6- or TOX-overexpressed T cells, total RNA of FACS-sorted retroviral infected GFP+ cells were extracted by using the miRNeasy kit (QIAGEN), complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were generated by the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR kits (Applied Biosystems). For confirming the expression levels of miR-23 clusters by qPCR, TaqMan (Thermo Fisher Scientific) stem-loop real-time reverse transcription PCR was performed. All real-time reactions were run on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers are shown in table S10.

Retroviral production and transduction

For BCL6 overexpression, pMSCV-BCL6-IRES-GFP, a gift from H. Ye [Addgene plasmid number 31391 (39)], was used. Retroviruses were produced by transfection of the HEK293T cell line, as described previously (13). FACS-sorted T naïve cells from CD4Ert2creBcl6fl/fl mice were stimulated for 24 hours in 24-well plates precoated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence of 0.5 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) and IL-2 (50 U/ml), followed by retroviral spin infection for 90 min at 2000 rpm in the presence of Polybrene (8 μg/ml) (Millipore). TOX expression in gated GFP+ population was examined 3 days after transduction by FACS. For TOX modulation, full-length TOX and shTOX (OriGene) were cloned into the pMIGR1 or pMDH vectors, respectively. FACS-sorted CD4+CD25−CD62Lhi T naïve cells from WT or SMARTA mice were stimulated in anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml)– and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml)–coated wells for 24 hours with IL-2 (25 U/ml), followed by retroviral spin infection as described above. After 3 days of retroviral transduction, cells were harvested, and GFP+ T cells were stained with selected sets of Abs for FACS analysis or sorted for SMARTA cell transfer study. For the latter study, a total of 5 × 104 GFP+ cells (for both single and cotransfer studies) were transferred intravenously into the congenically marked recipient.

CRISPR-based gene editing in primary murine CD4+ T cells

Cbh promoter–driven GFP expressing CRISPR-Cas9 vector was generated from the modification of the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP vector [Addgene, pX458 plasmid number 48138 (40)] with cloning Tox guide RNA (gRNA) into the vector. The GFP marker acts as the indicator for the CRISPR-targeted cells. The gRNA sequences were designated targeting Exon2: “ggctggctggcacatagtcc.” The design and cloning of gRNAs into CRISPR-Cas9 vectors were performed as described previously (41).

FACS-sorted CD4+CD25−CD62Lhi T naïve cells from SMARTA mice were stimulated in anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml)– and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml)–coated wells for 24 hours with IL-2 (50 U/ml), followed by electroporation with a Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen) under the following conditions: voltage (1400 V), width (50 ms), pulses (one), 100-μl tip, and Buffer T. Cells were transfected with 6 μg of empty plasmid pX458 or pX458 with Tox gRNA. After electroporation, cells were plated in a 24-well plate in 1 ml of cRPMI 1640 with IL-2 (50 U/ml) in the presence of aforementioned plate-bound monoclonal Abs for 1 day and further expanded in a six-well plate in 4 ml of cRPMI 1640 with IL-2 (50 U/ml) without activating Abs for an additional 2 days. GFP+ cells were FACS-sorted 3 days after electroporation and injected immediately into the congenically marked recipient mice for the SMARTA cell transfer study.

Gene expression profiling and ChIP-seq data analysis

CD4+CD25−CD44− naïve T (Tn) cells, CD4+CD25−CD44+CXCR5−PSGL1hi TH1 cells, CD4+CD25−CD44+CXCR5+PSGL1intTFH cells, and CD4+CD25−CD44+CXCR5+PSGL1lo GC-TFH cells in the spleen from LCMV-infected T-DKO mice, and WT controls were sorted on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) followed by total RNA isolation using a miRNeasy Kit (QIAGEN). Poly-A RNA-seq was performed using three biological replicates for each cell population, similar to what was described previously (13). Sequenced reads were trimmed or filtered out for low-quality sequence or shorter sequence by FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit), then aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm9), and obtained RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of transcript, per Million mapped reads) values per gene using Tophat/Cufflinks (42). Gene information was obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/). We transformed the raw measurement into Z scores, the relative expression of a gene in all WT samples. The genes with consistent value in three times of TFH and/or GC-TFH and/or Tn and/or TH1 were selected. To classify that the genes are higher in T-DKO than WT cells, only those genes with P <5% and the value of log2 fold change more than 0.05 in TFH and/or GC-TFH and/or Tn and/or TH1 are selected. Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus) was used to generate gene expression heatmaps. Putative target sites of different miR-23~27~24 family members were identified on the basis of the presence of perfect seed complementarity between positions 2 and 7 of the corresponding miRNAs with positive AGO binding peaks in the HITS-CLIP database (23). Venny 2.1.0 (bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny) was used to show all possible relations among different datasets. Gene expression profiling data in CD8+ T cells and common ILC progenitors were derived from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): GSE93804 (27) and GEO: GSE65850 (30), respectively.

ChIP-Seq analyses of human GC-TFH cell BCL6, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac data were derived from GEO GSE59933. To identify the regulatory network between transcription factor and gene, we integrated ChIP-seq experiments and the profiles of histone modifications. Last, the WashU Epigenome Browser was used to visualize public ChIP-seq data from ChIP-Atlas (http://chip-atlas.org/) (43).

Human lymph nodes (LNs) and cell preparation

Because of ethical considerations, human LNs were obtained from patients with head and neck cancer undergoing lymphadenectomy as a diagnostic procedure. This project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Chang Gung Medical Foundation (no. 1812210039). All samples were obtained after informed consent. Mononuclear cell suspension was obtained immediately after surgery by mechanically crushing the sample using a scalpel and Frosted Microscope Slides followed by syringing through a 23-gauge needle. All steps were performed on ice. The cell suspension was washed in cold PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), resuspended at 107 cells/ml, and used for immunostaining.

Statistical analyses

Unpaired Student’s t test with a 95% confidence interval was performed using Prism software (GraphPad). Paired Student’s t test was applied to SMARTA CD4+ T cell cotransfer study. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in all data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of our laboratory for discussions. We thank S. Hedrick, A. Goldrath at UCSD, and Y. Zheng at Salk Institute for providing CD4Ert2creBcl6fl/fl and SMARTA mice. Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants AI089935, AI103646, AI108651, and AI123782 (L.-F.L.), by the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology funding from Shenzhen City and Longgang District (H.-Y.H.), by Universidad Catolica San Antonio de Murcia and The Moxie Foundation (J.C.I.B.), and by a grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital: CMRPD1D0411~3 (M.-L.K.). Author contributions: Conceived and designed the experiments: C.-J.W. and L.-F.L. Performed the experiments: C.-J.W., S.C., C.-H.L., J.R., L.O.C., F.F.d.C., M.-C.C., L.-L.L., L.M.W., J.B., and D.T.U. Analyzed the data: C.-J.W., S.C., H.-Y.H., S.Q., and L.-F.L. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: H.-Y.H., H.-K.L., N.O.S.C., D.Z., J.C.I.B., L.-C.C., S.-F.H., and M.-L.K. Wrote the paper: C.-J.W., L.M.W., and L.-F.L. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: The authors declare that the data and materials supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and are available upon reasonable requests to the authors. Specifically, mice with conditional alleles of miR-23~27~24 clusters or mice that selectively overexpress the whole miR-23a cluster (23CTg) or individual members can be provided by UCSD pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for the aforementioned mouse lines should be submitted to: lifanlu@ucsd.edu. RNA-seq data for different T cell subsets from T-DKO mice and WT littermates are available from the GEO database (GEO GSE118698).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/12/eaaw1715/DC1

Fig. S1. Mice with T cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family exhibited enhanced TFH and GC B cell responses during airway allergic reaction.

Fig. S2. Elevation in the frequency of TFH cells in the LCMV-specific T cell population upon LCMV infection.

Fig. S3. Enhanced LCMV-specific Ab responses in mice with T cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family.

Fig. S4. TFH cell–intrinsic role of the miR-23~27~24 family in regulating TFH cell responses.

Fig. S5. Elevated expressions of the miR-23~27~24 family in GC-TFH cells.

Fig. S6. Treg cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family led to any alteration in TFH and GC B cell responses upon LCMV infection.

Fig. S7. Exaggerated regulation by the miR-23~27~24 family in T cells led to reduced TFH cell responses.

Fig. S8. Presence of distinct T cell subsets in mice during LCMV infection.

Fig. S9. TOX was repressed by miR-23 and miR-27 but not miR-24.

Fig. S10. TOX knockdown led to impaired TFH cell responses.

Fig. S11. Modulations of TOX amounts in T cells did not affect T cell homeostasis.

Fig. S12. Id2, Icos, and Maf are not regulated by TOX in TFH cells.

Table S1. Gene list III: Genes are significantly up-regulated in both TFH and GC-TFH cells.

Table S2. Gene list IV: Genes are significantly up-regulated in TFH cells.

Table S3. Gene list V: Genes are significantly up-regulated in GC-TFH cells.

Table S4. Gene list I: Genes are significantly up-regulated in T-DKO GC-TFH cells.

Table S5. Gene list II: Genes are significantly up-regulated in T-DKO TFH cells.

Table S6. miR-23 targets by HITS-CLIP.

Table S7. miR-24 targets by HITS-CLIP

Table S8. miR-27 targets by HITS-CLIP.

Table S9. Gene list: Common elements in “GSE93804” and “GSE65850.”

Table S10. Primer list.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Crotty S., Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 621–663 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinuesa C. G., Linterman M. A., Yu D., MacLennan I. C., Follicular helper T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34, 335–368 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston R. J., Poholek A. C., DiToro D., Yusuf I., Eto D., Barnett B., Dent A. L., Craft J., Crotty S., Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science 325, 1006–1010 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nurieva R. I., Chung Y., Martinez G. J., Yang X. O., Tanaka S., Matskevitch T. D., Wang Y.-H., Dong C., Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science 325, 1001–1005 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu D., Rao S., Tsai L. M., Lee S. K., He Y., Sutcliffe E. L., Srivastava M., Linterman M., Zheng L., Simpson N., Ellyard J. I., Parish I. A., Ma C. S., Li Q. J., Parish C. R., Mackay C. R., Vinuesa C. G., The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity 31, 457–468 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi Y. S., Kageyama R., Eto D., Escobar T. C., Johnston R. J., Monticelli L., Lao C., Crotty S., ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity 34, 932–934 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatzi K., Nance J. P., Kroenke M. A., Bothwell M., Haddad E. K., Melnick A., Crotty S., BCL6 orchestrates Tfh cell differentiation via multiple distinct mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 212, 539–553 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X., Chen X., Zhong B., Wang A., Wang X., Chu F., Nurieva R. I., Yan X., Chen P., van der Flier L. G., Nakatsukasa H., Neelapu S. S., Chen W., Clevers H., Tian Q., Qi H., Wei L., Dong C., Transcription factor achaete-scute homologue 2 initiates follicular T-helper-cell development. Nature 507, 513–518 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauquet A. T., Jin H., Paterson A. M., Mitsdoerffer M., Ho I. C., Sharpe A. H., Kuchroo V. K., The costimulatory molecule ICOS regulates the expression of c-Maf and IL-21 in the development of follicular T helper cells and TH-17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 167–175 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spolski R., Leonard W. J., IL-21 and T follicular helper cells. Int. Immunol. 22, 7–12 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C.-J., Lu L.-F., MicroRNA in Immune Regulation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 410, 249–267 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maul J., Baumjohann D., Emerging roles for MicroRNAs in T follicular helper cell differentiation. Trends Immunol. 37, 297–309 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho S., Wu C.-J., Yasuda T., Cruz L. O., Khan A. A., Lin L.-L., Nguyen D. T., Miller M., Lee H.-M., Kuo M.-L., Broide D. H., Rajewsky K., Rudensky A. Y., Lu L. F., miR-23∼27∼24 clusters control effector T cell differentiation and function. J. Exp. Med. 213, 235–249 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz L. O., Hashemifar S. S., Wu C.-J., Cho S., Nguyen D. T., Lin L.-L., Khan A. A., Lu L.-F., Excessive expression of miR-27 impairs Treg-mediated immunological tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 530–542 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho S., Wu C.-J., Nguyen D. T., Lin L.-L., Chen M. C., Khan A. A., Yang B.-H., Fu W., Lu L.-F., A novel miR-24–TCF1 axis in modulating effector T cell responses. J. Immunol. 198, 3919–3926 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi Y. S., Gullicksrud J. A., Xing S., Zeng Z., Shan Q., Li F., Love P. E., Peng W., Xue H.-H., Crotty S., LEF-1 and TCF-1 orchestrate TFH differentiation by regulating differentiation circuits upstream of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Nat. Immunol. 16, 980–990 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu L., Cao Y., Xie Z., Huang Q., Bai Q., Yang X., He R., Hao Y., Wang H., Zhao T., Fan Z., Qin A., Ye J., Zhou X., Ye L., Wu Y., The transcription factor TCF-1 initiates the differentiation of TFH cells during acute viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 16, 991–999 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pua H. H., Steiner D. F., Patel S., Gonzalez J. R., Ortiz-Carpena J. F., Kageyama R., Chiou N. T., Gallman A., de Kouchkovsky D., Jeker L. T., McManus M. T., Erle D. J., Ansel K. M., MicroRNAs 24 and 27 suppress allergic inflammation and target a network of regulators of T helper 2 cell-associated cytokine production. Immunity 44, 821–832 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harker J. A., Lewis G. M., Mack L., Zuniga E. I., Late interleukin-6 escalates T follicular helper cell responses and controls a chronic viral infection. Science 334, 825–829 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pratama A., Srivastava M., Williams N. J., Papa I., Lee S. K., Dinh X. T., Hutloff A., Jordan M. A., Zhao J. L., Casellas R., Athanasopoulos V., Vinuesa C. G., MicroRNA-146a regulates ICOS–ICOSL signalling to limit accumulation of T follicular helper cells and germinal centres. Nat. Commun. 6, 6436 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen G., Hardy K., Bunting K., Daley S., Ma L., Shannon M. F., Regulation of the IL-21 gene by the NF-κB transcription factor c-Rel. J. Immunol. 185, 2350–2359 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W.-H., Kang S. G., Huang Z., Wu C.-J., Jin H. Y., Maine C. J., Liu Y., Shepherd J., Sabouri-Ghomi M., Gonzalez-Martin A., Xu S., Hoffmann A., Zheng Y., Lu L.-F., Xiao N., Fu G., Xiao C., A miR-155–Peli1–c-Rel pathway controls the generation and function of T follicular helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 213, 1901–1919 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loeb G. B., Khan A. A., Canner D., Hiatt J. B., Shendure J., Darnell R. B., Leslie C. S., Rudensky A. Y., Transcriptome-wide miR-155 binding map reveals widespread noncanonical microRNA targeting. Mol. Cell 48, 760–770 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X., Lu H., Chen T., Nallaparaju K. C., Yan X., Tanaka S., Ichiyama K., Zhang X., Zhang L., Wen X., Tian Q., Bian X. W., Jin W., Wei L., Dong C., Genome-wide analysis identifies Bcl6-controlled regulatory networks during T follicular helper cell differentiation. Cell Rep. 14, 1735–1747 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aliahmad P., Seksenyan A., Kaye J., The many roles of TOX in the immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 173–177 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crotty S., T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 41, 529–542 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page N., Klimek B., de Roo M., Steinbach K., Soldati H., Lemeille S., Wagner I., Kreutzfeldt M., di Liberto G., Vincenti I., Lingner T., Salinas G., Brück W., Simons M., Murr R., Kaye J., Zehn D., Pinschewer D. D., Merkler D., Expression of the DNA-binding factor TOX promotes the encephalitogenic potential of microbe-induced autoreactive CD8+ T cells. Immunity 48, 937–950.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornete M., Marone R., Jeker L. T., Highly efficient and versatile plasmid-based gene editing in primary T cells. J. Immunol. 200, 2489–2501 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw L. A., Bélanger S., Omilusik K. D., Cho S., Scott-Browne J. P., Nance J. P., Goulding J., Lasorella A., Lu L.-F., Crotty S., Goldrath A. W., Id2 reinforces TH1 differentiation and inhibits E2A to repress TFH differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 17, 834–843 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seehus C. R., Aliahmad P., de la Torre B., Iliev I. D., Spurka L., Funari V. A., Kaye J., The development of innate lymphoid cells requires TOX-dependent generation of a common innate lymphoid cell progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 16, 599–608 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aliahmad P., Kadavallore A., de la Torre B., Kappes D., Kaye J., TOX is required for development of the CD4 T cell lineage gene program. J. Immunol. 187, 5931–5940 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi J., Hou S., Fang Q., Liu X., Liu X., Qi H., PD-1 controls follicular T helper cell positioning and function. Immunity 49, 264–274.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian L., Altin J. A., Makaroff L. E., Franckaert D., Cook M. C., Goodnow C. C., Dooley J., Liston A., Foxp3+ regulatory T cells exert asymmetric control over murine helper responses by inducing Th2 cell apoptosis. Blood 118, 1845–1853 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aliahmad P., de la Torre B., Kaye J., Shared dependence on the DNA-binding factor TOX for the development of lymphoid tissue-inducer cell and NK cell lineages. Nat. Immunol. 11, 945–952 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon H.-K., Chen H.-M., Mathis D., Benoist C., Different molecular complexes that mediate transcriptional induction and repression by FoxP3. Nat. Immunol. 18, 1238–1248 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghajani K., Keerthivasan S., Yu Y., Gounari F., Generation of CD4CreERT2 transgenic mice to study development of peripheral CD4-T-cells. Genesis 50, 908–913 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollister K., Kusam S., Wu H., Clegg N., Mondal A., Sawant D. V., Dent A. L., Insights into the role of Bcl6 in follicular Th cells using a new conditional mutant mouse model. J. Immunol. 191, 3705–3711 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oxenius A., Bachmann M. F., Zinkernagel R. M., Hengartner H., Virus-specific MHC-class II-restricted TCR-transgenic mice: Effects on humoral and cellular immune responses after viral infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 390–400 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu R. Y., Wang X., Pixley F. J., Yu J. J., Dent A. L., Broxmeyer H. E., Stanley E. R., Ye B. H., BCL-6 negatively regulates macrophage proliferation by suppressing autocrine IL-6 production. Blood 105, 1777–1784 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D. A., Zhang F., Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao H.-K., Gu Y., Diaz A., Marlett J., Takahashi Y., Li M., Suzuki K., Xu R., Hishida T., Chang C.-J., Esteban C. R., Young J., Belmonte J. C. I., Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system as an intracellular defense against HIV-1 infection in human cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 6413 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho S., Lee H.-M., Yu I.-S., Choi Y. S., Huang H.-Y., Hashemifar S. S., Lin L.-L., Chen M.-C., Afanasiev N. D., Khan A. A., Lin S.-W., Rudensky A. Y., Crotty S., Lu L.-F., Differential cell-intrinsic regulations of germinal center B and T cells by miR-146a and miR-146b. Nat. Commun. 9, 2757 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X., Maricque B., Xie M., Li D., Sundaram V., Martin E. A., Koebbe B. C., Nielsen C., Hirst M., Farnham P., Kuhn R. M., Zhu J., Smirnov I., Kent W. J., Haussler D., Madden P. A., Costello J. F., Wang T., The Human Epigenome Browser at Washington University. Nat. Methods 8, 989 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/12/eaaw1715/DC1

Fig. S1. Mice with T cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family exhibited enhanced TFH and GC B cell responses during airway allergic reaction.

Fig. S2. Elevation in the frequency of TFH cells in the LCMV-specific T cell population upon LCMV infection.

Fig. S3. Enhanced LCMV-specific Ab responses in mice with T cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family.

Fig. S4. TFH cell–intrinsic role of the miR-23~27~24 family in regulating TFH cell responses.

Fig. S5. Elevated expressions of the miR-23~27~24 family in GC-TFH cells.

Fig. S6. Treg cell–specific ablation of the miR-23~27~24 family led to any alteration in TFH and GC B cell responses upon LCMV infection.

Fig. S7. Exaggerated regulation by the miR-23~27~24 family in T cells led to reduced TFH cell responses.

Fig. S8. Presence of distinct T cell subsets in mice during LCMV infection.

Fig. S9. TOX was repressed by miR-23 and miR-27 but not miR-24.

Fig. S10. TOX knockdown led to impaired TFH cell responses.

Fig. S11. Modulations of TOX amounts in T cells did not affect T cell homeostasis.

Fig. S12. Id2, Icos, and Maf are not regulated by TOX in TFH cells.

Table S1. Gene list III: Genes are significantly up-regulated in both TFH and GC-TFH cells.

Table S2. Gene list IV: Genes are significantly up-regulated in TFH cells.

Table S3. Gene list V: Genes are significantly up-regulated in GC-TFH cells.

Table S4. Gene list I: Genes are significantly up-regulated in T-DKO GC-TFH cells.

Table S5. Gene list II: Genes are significantly up-regulated in T-DKO TFH cells.

Table S6. miR-23 targets by HITS-CLIP.

Table S7. miR-24 targets by HITS-CLIP

Table S8. miR-27 targets by HITS-CLIP.

Table S9. Gene list: Common elements in “GSE93804” and “GSE65850.”

Table S10. Primer list.