Abstract

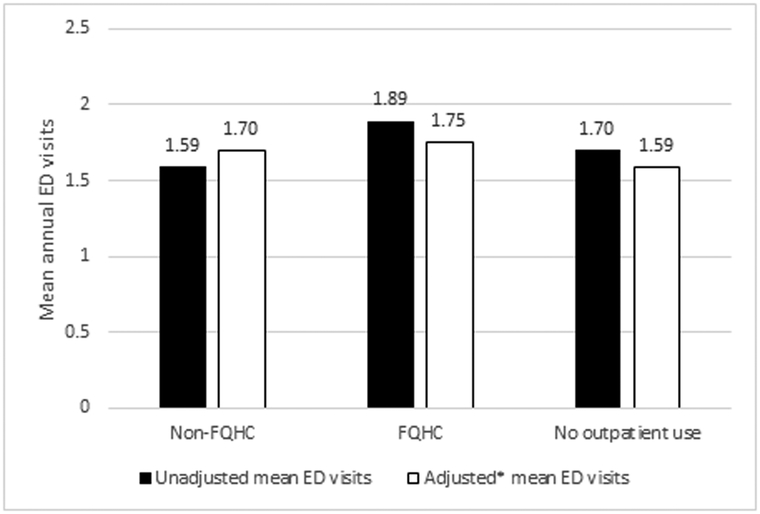

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) have long been important sources of care for publicly insured people living with HIV. FQHC users have historically used emergency departments (EDs) at a higher-than-average rate. This paper examines whether this greater use relates to access difficulties in FQHCs or to characteristics of FQHC users. Zero-inflated Poisson models were used to estimate how FQHC use related to the odds of being an ED user and annual number of ED visits, using claims data on 6,284 HIV-infected California Medicaid beneficiaries in 2008-2009. FQHC users averaged significantly greater numbers of annual ED visits than non-FQHC users and those with no outpatient usage (1.89, 1.59, and 1.70, respectively; P=0.043). FQHC users had higher odds of being ED users (OR=1.14; 95%CI 1.02-1.27). In multivariable analyses, FQHC clients had higher odds of ED usage controlling for demographic and service characteristics (OR=1.15; 95%CI 1.02-1.30) but not when medical characteristics were included (OR=1.08; 95%CI 0.95-1.24). Among ED users, FQHC use was not significantly associated with the number of ED visits in our models (rate ratio (RR)=1.00; 95%CI 0.87-1.15). The overall difference in mean annual ED visits observed between FQHC and non-FQHC groups was reduced to insignificance (1.75; 95% CI 1.59-1.92 vs 1.70; 95%CI 1.54-1.85) after adjusting for demographic, service, and medical characteristics. Overall, FQHC users had higher ED utilization than non-FQHC users, but the disparity was largely driven by differences in underlying medical characteristics.

Keywords: HIV, Federally Qualified Health Center, California, Medicaid, emergency department

Introduction

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are safety net health providers of primary care services to medically underserved communities. First established in 1991 under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, FQHCs are required to provide comprehensive services, serve a designated medically underserved area or population, and offer a sliding fee scale to persons with incomes below two hundred percent of the federal poverty level(Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 13- Rural Health Clinic (RHC) and Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Services, 2014). In 2011, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allocated $11 billion over five years to fund community health centers (a type of FQHC) to help meet the anticipated increased health care demand following the ACA’s insurance expansion(The Affordable Care Act and Health Centers, 2012). FQHCs have had an important part in the health care of people living with HIV (PLWH) since HIV disproportionately affects lower income communities. In 2009, there were 427,797 encounters in community health centers nationwide among 94,972 patients with HIV/AIDS(“HIV Screening and Access to Care: Exploring the Impact of Policies on Access to and Provision of HIV Care,” 2011). Furthermore, since an AIDS diagnosis often confers disability status, many low income PLWH received health coverage through Medicaid, and sought care in FQHCs. It was estimated that in 2009, 40.3% of PLWH in the US receiving outpatient care had Medicaid coverage(Blair et al., 2014).

Given their continued expansion, it is important to assess how successful FQHCs are in keeping populations healthy and decreasing utilization of emergency services. This issue is especially relevant to PLWH, who have higher ED visit rates with more diagnostic and screening tests, higher likelihood of being admitted, and longer duration of stay, than non-HIV-infected patients(Mohareb, Rothman, & Hsieh, 2013).

Comparisons of ED utilization among FQHC and non-FQHC users who are HIV-infected are lacking. However, a study done among dual-eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries (not limited to HIV) from 2008-2010 found higher ED utilization and hospitalizations among FQHC users across all racial groups(Wright, Potter, & Trivedi, 2015). A similar study in Colorado showed that Medicaid beneficiaries who used FQHCs had higher rates of ED utilization, but their odds of ED utilization were actually lower when adjusted for age, sex, rural residence, and disability status(Rothkopf, Brookler, Wadhwa, & Sajovetz, 2011). An ecological study found that counties with community health centers and rural health clinics had lower rates of hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (those in which primary care of acceptable quality can reduce the frequency of hospitalization) (Probst, Laditka, & Laditka, 2009).

This study seeks to determine how FQHC usage by PLWH enrolled in California’s Medicaid program (also known as Medi-Cal) relates to ED use. We hypothesized that patients receiving care at FQHCs would have higher ED utilization, even after accounting for known risk factors. Studying this question in the Medicaid population is particularly relevant because public insurance has been found to be associated with increased ED utilization(Josephs, Fleishman, Korthuis, Moore, & Gebo, 2010; Ondler, Hegde, & Carlson, 2014). This study provides a unique opportunity to test this hypothesis while accounting for substance abuse disorders, which have been found to be important predictors of increased ED utilization(Braden et al., 2010; Castner, Wu, Mehrok, Gadre, & Hewner, 2015). We use 2009 data because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) redacted substance abuse diagnoses from more recent Medicaid claims public use data due to confidentiality concerns; thus omitted variable bias, where the effect of omitted variables is misattributed to the included variables, might limit the conclusions from more recent data.

Methods

Overview and Study Cohort.

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of beneficiaries enrolled in Medi-Cal using data obtained through a confidential data use agreement with CMS. HIV diagnosis was defined by a previously developed and validated algorithm(Leibowitz & Desmond, 2015) designed to capture those with strong evidence of HIV diagnosis. The sample included only beneficiaries who were enrolled for the entire 24 months of 2008 and 2009 since some of our variables, including service and medical characteristics, were abstracted from the year prior (2008) to ED utilization in 2009 to minimize the potential bias of reverse causality. Pregnant and dual-eligible Medicare and Medicaid patients were excluded. The UCLA Office of the Human Research Protection Program determined that the project does not meet the definition of human subjects research and no IRB review was required (IRB#10-000823).

Measures

Outcome Measure: Emergency Department Utilization.

The number of ED visits was defined as the total number of claims on separate days associated with an ED for each beneficiary from January 1 to December 31, 2009. We examine both the probability of ED use and the number of ED visits.

Covariates

Federally Qualified Health Center Status.

Beneficiaries were divided into three groups by FQHC status: 1) FQHC users had any outpatient evaluation/management (E&M) claims at a FQHC during 2008; 2) Non-FQHC users had at least one outpatient E&M claim, but none at a FQHC; 3) The “no outpatient use” group consisted of those with no outpatient E&M claims in 2008.

Demographics.

Age, gender, and race were included in the model. Race was reported by CMS and was stratified as non-Hispanic white (reference group), African American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other/unknown. Rural vs urban residence was determined by the ZIP code of residence in 2009, using the Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes. These were further dichotomized into rural and urban according to the University of Washington schema (Categorization C)(RUCA data: Using RUCA data). Neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) and education level were represented by the median income(U.S. Census Bureau, 2011b) and the percentage of high school and college graduates in the ZIP code of residence in 2009, respectively, as reported in the American Community Surveys(U.S. Census Bureau, 2011a).

Service Characteristics.

Enrollment in a Medi-Cal managed care plan for any part of 2008 was included. Provider HIV volume was ascertained by determining the number of unique beneficiaries with HIV (ICD-9 codes 042 or v08) in any diagnosis field in 2008 for each provider across Medi-Cal and Medicare databases. To assess access to HIV expertise, patients were divided into three groups according to the highest number of HIV patients seen by any of their E&M providers: <5 (including patients with zero E&M visits), 5-49, and ≥50 HIV-infected patients.

Medical Characteristics.

Mental health and substance abuse diagnoses were defined using the ICD-9 codes designed by the Clinical Classifications Software for ICD-9-CM (CCS)(Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM), while tobacco usage was determined by tobacco-related diagnosis codes. Medical comorbidities were determined using standard ICD-9 codes for the comorbidities that comprise the Charlson Comorbidity Index(Quan et al., 2005). AIDS was excluded in order to capture the effect of comorbidities aside from HIV. Because 71.3% of the subjects did not have any comorbidities, the variable was dichotomized to reflect the presence or absence of any Charlson comorbidity. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) usage was based on the presence of any ART claims in 2008. All comorbidities and diagnoses were counted only if they appeared on ≥1 inpatient or ED claim, or ≥2 outpatient claims.

Statistical analysis

Zero-inflated Poisson regression (ZIPR)(Lambert, 1992) was used to model the impact of FQHC status on the number of ED visits. A ZIPR model was used because >50% of 2009 beneficiaries had zero ED visits. Its appropriateness was confirmed by the Vuong statistic(Vuong, 1989) (z=19.08, p<0.0001). A bivariate model was first used to estimate the association between FQHC usage and ED utilization (Model A). Then demographic (age, sex, race, income, education) and service characteristics (managed care, provider HIV experience) were added to form a multivariable model (Model B). Finally, medical characteristics (mental health, substance abuse, tobacco, medical comorbidity, ART usage) were added to create a final multivariable model (Model C). This sequential approach was undertaken to better understand the contributions of each group of covariates on the FQHC association found in Model A. The ZIPR model allowed us to model two aspects of ED utilization. The logistic portion models the odds of being an ED non-user. For easier interpretation, we present the inverse of the odds ratios (OR), reflecting the odds of being an ED user. The conditional count (Poisson) portion models the number of annual ED visits among potential ED users. Associations are presented as rate ratios (RR). As a sensitivity analysis we removed the top 1% of ED users (≥18 ED visits) to verify that results were not unduly affected by extreme ED utilization. Predictive margins were calculated to show the combined association of FQHC usage on ED utilization. All analyses were conducted with Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp), using a two-tailed .05 level of significance and robust standard errors. The first diagnosis code associated with each 2009 ED visit was abstracted and the top ten diagnoses were tabulated.

Results

Patient characteristics

Almost 40% of the 6,284 HIV-infected Medi-Cal beneficiaries were seen in FQHCs in 2008 (Table 1). FQHC users had a median of 7 FQHC visits in 2008 (interquartile range 4-12). ED utilization was similar for the three groups overall, with >50% of each group having zero 2009 ED visits, though the mean number of ED visits was highest among FQHC users compared to non-FQHC users and those with no outpatient usage (1.89, 1.59, and 1.70 visits respectively, P=0.04). The study population had a mean age of 47.0 years, was mostly men (66.6%), and comprised a large minority population (33.1% African American, 20.7% Hispanic, 10.9% other/unknown). FQHC and non-FQHC users lived in neighborhoods with similar percentages of high school and college graduates. Several notable differences were found among the three groups. FQHC users were slightly older and more likely to be male. They were more likely to reside in rural areas and neighborhoods with lower income. Their service characteristics were also notably different. FQHC patients were more likely to have seen providers with ≥50 HIV-infected patients, and were much less likely to have been enrolled in managed care in 2008. In terms of medical characteristics, FQHC users were more likely to have mental health and substance abuse diagnoses. Both FQHC and non-FQHC users were significantly more likely to have medical comorbidities than those with no outpatient usage; FQHC users were less likely to be on ART compared to non-FQHC users.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Study Subjects, Stratified by 2008 Federally Qualified Health Center Status (n=6284)

| Characteristics | Non-FQHC n=3517 n(%) |

FQHC n=2445 n(%) |

No outpatient use n=322 n(%) |

Overall n=6284 n(%) |

P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: | |||||

| Number of ED visits, 2009: mean(SD) | 1.59 (4.39) | 1.89 (4.77) | 1.70 (4.12) | 1.72 (4.53) | 0.043 |

| 0 | 1949 (55.4%) | 1266 (51.8%) | 177 (55.0%) | 3392 (54.0%) | 0.083 |

| 1-5 | 1323 (37.6%) | 968 (39.6%) | 118 (36.7%) | 2409 (38.3%) | |

| 6-9 | 143 (4.1%) | 117 (4.8%) | 16 (5.0%) | 276 (4.4%) | |

| ≥10 | 102 (2.9%) | 94 (3.8%) | 11 (3.4%) | 207 (3.3%) | |

| Demographics2: | |||||

| Mean Age (SD) | 46.8 (9.7) | 47.6 (9.0) | 45.1 (9.3) | 47.0 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| 18-29 | 197 (5.6%) | 105 (4.3%) | 18 (5.6%) | 320 (5.1%) | <0.001 |

| 30-39 | 467 (13.3%) | 299 (12.2%) | 63 (19.6%) | 829 (13.2%) | |

| 40-49 | 1427 (40.6%) | 964 (39.4%) | 143 (44.4%) | 2534 (40.3%) | |

| 50-59 | 1146 (32.6%) | 889 (36.4%) | 75 (23.3%) | 2110 (33.6%) | |

| ≥60 | 280 (8.0%) | 188 (7.7%) | 23 (7.1%) | 491 (7.8%) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 1255 (35.7%) | 733 (30.0%) | 113 (35.1%) | 2101 (33.4%) | |

| Male | 2262 (64.3%) | 1712 (70.0%) | 209 (64.9%) | 4183 (66.6%) | |

| Race | 0.373 | ||||

| White | 1277 (36.3%) | 841 (34.4%) | 102 (31.7%) | 2220 (35.3%) | |

| African American | 1143 (32.5%) | 829 (33.9%) | 108 (33.5%) | 2080 (33.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 730 (20.8%) | 496 (20.3%) | 76 (23.6%) | 1302 (20.7%) | |

| Asian/other/unknown3 | 367 (10.4%) | 279 (11.4%) | 36 (11.2%) | 682 (10.9%) | |

| Urban residence | 3421 (97.3%) | 2304 (94.2%) | 312 (96.9%) | 6037 (96.1%) | <0.001 |

| Mean ZIP code income (SD) | $49284 (1791) | $47752 (1992) | $48525 (1877) | $48649 (1877) | 0.008 |

| Mean % HS graduates in ZIP code (SD) | 76.2 (13.8) | 76.8 (13.2) | 76.5 (13.1) | 76.5 (13.5) | 0.235 |

| Mean % college graduates in ZIP code (SD) | 26.6 (16.4) | 29.3 (18.0) | 27.9 (17.7) | 27.6 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| Service characteristics2: | |||||

| Enrolled in managed care | 1042 (29.6%) | 90 (3.7%) | 95 (29.5%) | 1227 (19.5%) | <0.001 |

| Provider HIV experience | <0.0015 | ||||

| <5 patients4 | 470 (13.4%) | 65 (2.7%) | 322 (100%) | 857 (13.6%) | |

| 5-49 patients | 1343 (38.2%) | 487 (19.9%) | N/A | 1830 (29.1%) | |

| ≥50 patients | 1704 (48.5%) | 1893 (77.4%) | N/A | 3597 (57.2%) | |

| Medical characteristics2: | |||||

| Any mental health diagnosis | 767 (21.8%) | 824 (33.7%) | 52 (16.2%) | 1643 (26.2%) | <0.001 |

| Any substance abuse diagnosis | 397 (11.3%) | 431 (17.6%) | 34 (10.6%) | 862 (13.7%) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco6 | 127 (2.0%) | 0.428 | |||

| Any medical comorbidity | 1158 (32.9%) | 801 (32.8%) | 41 (12.7%) | 2000 (31.8%) | <0.001 |

| On ART | 3249 (92.4%) | 2186 (89.4%) | 284 (88.2%) | 5719 (91.0%) | <0.001 |

P values from comparisons of non-FQHC, FQHC, and no outpatient use categories. For continuous variables, comparisons use ANOVA (or Kruskal-Wallis tests for skewed distributions). For categorical variables, comparisons use Chi-squared tests

Demographics are from 2009, service and medical characteristics are from 2008

Asian/Pacific Islander and other/unknown were combined because CMS prohibits publication of cell sizes <11

Includes patients with zero outpatient visits

Comparison of non-FQHC to FQHC.

At least one cell size was too small to be reportable per CMS limits. There was not a significant difference in tobacco use across groups.

Abbreviations: FQHC: Federally Qualified Health Center, ED: emergency department, HS: high school, ART: antiretroviral therapy.

Odds of being an ED user

In the bivariate model (A), FQHC users had significantly higher odds of being an ED user compared to non-FQHC users (OR=1.14; 95%CI 1.02-1.27) (Table 2). This relationship remained significant when demographic and service characteristics were adjusted for (B). FQHC users were not significantly greater users of EDs when medical characteristics were added into the model (C) (OR 1.08; 95%CI 0.95-1.24). Several demographic characteristics were found to be significant in the full model (C). Older patients (50-59 years old (OR 0.73; 95%CI 0.55-0.97) and ≥60 years old (OR 0.51; 95%CI 0.36-0.71)), males (OR 0.73; 95%CI 0.64-0.83), and Asian/Pacific Islanders (OR 0.64; 95%CI 0.41-0.98) had lower odds of being ED users, while African Americans (OR 1.19; 95%CI 1.03-1.37) and those with higher percentages of high school graduates in their ZIP code (OR 1.011; 95%CI 1.003-1.019) had higher odds. Service characteristics were not significant predictors. Among the medical characteristics, mental health (OR 1.20; 95%CI 1.05-1.37), substance abuse (OR 2.00; 95%CI 1.69-2.36), tobacco (OR 1.68; 95%CI 1.14-2.47), and medical comorbidities (OR 1.66; 95%CI 1.47-1.88) were all associated with higher odds of being an ED user, while ART usage was associated with lower odds (OR 0.73; 95%CI 0.61-0.87).

Table 2.

Relationship Between Predictors and Odds of Being an ED User in 20091 (n=6284)

| Bivariate model (A) | Multivariable model with demographics & service characteristics (B) |

Full multivariable model (C) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR (95%CI) |

P value |

OR (95% CI) |

P value |

OR (95% CI) |

P value |

| FQHC status2: | ||||||

| Non-FQHC | ref | ref | ref | |||

| FQHC | 1.14 (1.02-1.27) | 0.019 | 1.15 (1.02-1.30) | 0.026 | 1.08 (0.95-1.24) | 0.238 |

| No outpatient use | 1.01 (0.79-1.28) | 0.959 | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | 0.302 | 0.94 (0.68-1.29) | 0.682 |

| Demographics2: | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-29 | ref | ref | ||||

| 30-39 | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | 0.916 | 0.99 (0.73-1.34) | 0.928 | ||

| 40-49 | 0.89 (0.69-1.14) | 0.353 | 0.83 (0.63-1.10) | 0.192 | ||

| 50-59 | 0.81 (0.63-1.05) | 0.115 | 0.73 (0.55-0.97) | 0.027 | ||

| ≥60 | 0.56 (0.41-0.76) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.36-0.71) | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | ref | ref | ||||

| Male | 0.70 (0.62-0.79) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.64-0.83) | <0.001 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | ref | ref | ||||

| African American | 1.23 (1.08-1.41) | 0.002 | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 0.021 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.84 (0.71-0.99) | 0.034 | 0.86 (0.71-1.03) | 0.102 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.56 (0.38-0.83) | 0.004 | 0.64 (0.41-0.98) | 0.042 | ||

| Other/unknown | 1.05 (0.85-1.29) | 0.677 | 1.04 (0.83-1.30) | 0.752 | ||

| Urban residence | 0.85 (0.62-1.17) | 0.318 | 0.78 (0.55-1.10) | 0.155 | ||

| ZIP code income (per $10000) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.175 | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | 0.471 | ||

| % HS graduates in ZIP code | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.005 | ||

| % College graduates in ZIP code | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.139 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.144 | ||

| Service characteristics2: | ||||||

| Enrolled in managed care | 1.04 (0.89-1.22) | 0.637 | 1.06 (0.89-1.26) | 0.504 | ||

| Provider HIV experience | ||||||

| <5 patients | ref | ref | ||||

| 5-49 patients | 0.78 (0.63-0.96) | 0.021 | 0.81 (0.64-1.01) | 0.065 | ||

| ≥50 patients | 0.92 (0.75-1.14) | 0.462 | 0.95 (0.76-1.19) | 0.666 | ||

| Medical characteristics2: | ||||||

| Any mental health diagnosis | 1.20 (1.05-1.37) | 0.006 | ||||

| Any substance abuse diagnosis | 2.00 (1.69-2.36) | <0.001 | ||||

| Tobacco | 1.68 (1.14-2.47) | 0.008 | ||||

| Any medical comorbidity | 1.66 (1.47-1.88) | <0.001 | ||||

| On ART | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) | <0.001 | ||||

| Model constant | 0.85 (0.79-0.92) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.45-1.69) | 0.686 | 1.03 (0.49-2.13) | 0.944 |

Based on inverted odds ratios from logistic portion of zero-inflated Poisson models, relating to any/no ED use.

Demographics are from 2009; FQHC status, service and medical characteristics are from 2008

Abbreviations: OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, FQHC: Federally Qualified Health Center, HS: high school, ART: antiretroviral therapy

Annual count of ED visits

Although FQHC users overall had greater numbers of ED visits, this difference was not significant among potential ED users in the bivariate model (A) (RR 1.11; 95%CI 0.97-1.27); the association remained insignificant in the full model (C) (RR 1.00; 95%CI 0.87-1.15) (Table 3). Few demographic characteristics were associated with the number of ED visits, but Asian/Pacific Islanders had fewer ED visits (RR 0.62; 95%CI 0.40-0.92), while urban residents had more (RR 1.46; 95%CI 1.14-1.88). Managed care enrollees (RR 0.83; 95%CI 0.71-0.98) and patients with high volume providers (RR 0.72; 95%CI 0.54-0.96) had fewer ED visits. Finally, all of the medical characteristics except ART usage (mental health (RR 1.43; 95%CI 1.27-1.61), substance abuse (RR 1.58; 95%CI 1.38-1.81), tobacco (RR 2.12; 95%CI 1.40-3.20), and medical comorbidities (RR 1.51; 95%CI 1.35-1.69)) were associated with increased rates of ED visits. Results were robust to dropping the top 1% of ED users in the sensitivity analysis.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Predictors and Number of ED Visits in 20091 (n=6284)

| Bivariate model (A) | Multivariable model with demographics & service characteristics (B) |

Full multivariable model (C) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | RR (95%CI) |

P value |

RR (95% CI) |

P value |

RR (95% CI) |

P value |

| FQHC status2: | ||||||

| Non-FQHC | ref | ref | ref | |||

| FQHC | 1.11 (0.97-1.27) | 0.135 | 1.11 (0.96-1.28) | 0.169 | 1.00(0.87-1.15) | 0.997 |

| No outpatient use | 1.07 (0.81-1.40) | 0.65 | .87 (0.58-1.32) | 0.516 | 0.97 (0.67-1.38) | 0.847 |

| Demographics2: | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-29 | ref | ref | ||||

| 30-39 | 1.10 (0.81-1.49) | 0.545 | 1.05 (0.78-1.43) | 0.732 | ||

| 40-49 | 1.03 (0.80-1.31) | 0.832 | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | 0.915 | ||

| 50-59 | 0.95 (0.73-1.23) | 0.685 | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | 0.249 | ||

| ≥60 | 0.88 (0.65-1.19) | 0.406 | 0.80 (0.59-1.10) | 0.167 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | ref | ref | ||||

| Male | 0.91 (0.79-1.04) | 0.170 | 0.94 (0.82-1.07) | 0.346 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | ref | ref | ||||

| African American | 1.12 (0.97-1.30) | 0.131 | 1.12 (0.98-1.29) | 0.104 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.92 (0.70-1.20) | 0.528 | 0.99 (0.76-1.27) | 0.913 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.59 (0.40-0.89) | 0.012 | 0.62 (0.40-0.94) | 0.025 | ||

| Other/unknown | 1.02 (0.82-1.28) | 0.845 | 1.11 (0.88-1.40) | 0.379 | ||

| Urban residence | 1.53 (1.19-1.95) | 0.001 | 1.46 (1.14-1.88) | 0.003 | ||

| ZIP code income (per $10000) | 0.96 (0.90-1.02) | 0.181 | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | 0.159 | ||

| % HS graduates in ZIP code | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.292 | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 0.132 | ||

| % College graduates in ZIP code | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.998 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.569 | ||

| Service characteristics2: | ||||||

| Enrolled in managed care | 0.79 (0.66-0.94) | 0.010 | 0.83 (0.71-0.98) | 0.029 | ||

| Provider HIV experience | ||||||

| <5 patients | ref | ref | ||||

| 5-49 patients | 0.81 (0.59-1.12) | 0.203 | 0.80 (0.60-1.07) | 0.133 | ||

| ≥50 patients | 0.74 (0.53-1.05) | 0.088 | 0.72 (0.54-0.96) | 0.026 | ||

| Medical characteristics2: | ||||||

| Any mental health diagnosis | 1.43 (1.28-1.61) | <0.001 | ||||

| Any substance abuse diagnosis | 1.58 (1.38-1.81) | <0.001 | ||||

| Tobacco | 2.12 (1.40-3.20) | <0.001 | ||||

| Any medical comorbidity | 1.51 (1.35-1.69) | <0.001 | ||||

| On ART | 0.85 (0.71-1.02) | 0.076 | ||||

| Model constant | 3.46 (3.15-3.80) | <0.001 | 2.83 (1.43-5.62) | 0.003 | 2.02 (1.00-4.09) | 0.049 |

Based on Poisson portion of zero-inflated Poisson models; relating to visit counts among potential ED users

Demographics are from 2009; FQHC status, service and medical characteristics are from 2008

Abbreviations: RR: rate ratio, CI: confidence interval, FQHC: Federally Qualified Health Center, HS: high school, ART: antiretroviral therapy

Adjusted mean annual ED visits and top ED diagnoses

Adjusting for demographic, service, and medical characteristics rendered differences in mean ED visits observed between FQHC and non-FQHC groups insignificant (1.75; 95% CI 1.59-1.92 vs 1.70; 95%CI 1.54-1.85) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean Number of 2009 ED Visits among HIV-Infected California Medicaid Beneficiaries, by FQHC status.

*Adjusted for age, gender, race, urban residence, ZIP code income, percent high school and college graduates in ZIP code, managed care, provider HIV volume, mental health diagnoses, substance abuse, tobacco use, medical comorbidities, and being on ART.

The most prevalent diagnoses identified at ED visits included chest pain, not otherwise specified (n=504); pre-operative exam, unspecified (n=311); and abdominal exam, unspecified site (n=288). HIV disease ranked at number 4 (n=274); the remaining diagnostic codes can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Top ED Diagnosis Codes among HIV-infected California Medicaid Beneficiaries, 2009

| ICD-9 code | n | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78650 | 504 | Chest pain NOS |

| 2 | V7284 | 311 | Preop exam unspecified |

| 3 | 78900 | 288 | Abdominal pain unspecified site |

| 4 | 042 | 274 | Human Immunodeficiency Virus disease |

| 5 | 486 | 245 | Pneumonia, organism NOS |

| 6 | 7840 | 235 | Headache |

| 7 | 78605 | 235 | Shortness of breath |

| 8 | 7862 | 169 | Cough |

| 9 | 78659 | 164 | Chest pain NEC |

| 10 | 7295 | 154 | Pain in limb |

Abbreviations: ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, NOS: Not otherwise specified; NEC: Not elsewhere classified

Discussion

Our study shows that, on average, FQHC users have higher odds of being ED users at all, rather than having more annual visits, given any ED use. However, after adjusting for demographic, service, and medical characteristics, the difference in any ED use was no longer statistically significant. Our findings indicate that the medical characteristics of FQHC patients (their mental health, substance abuse, tobacco use, and medical comorbidities), rather than the characteristics of the FQHC setting (such as differences in quality of care, access to specialists, or wait times), are responsible for the increased ED utilization among FQHC patients.

Other studies of Medicaid beneficiaries’ use of EDs have shown mixed results. Some have documented increased(Wright et al., 2015) ED utilization among FQHC patients, while others have shown decreased ED use(Rothkopf et al., 2011). However, these studies included patients with heterogeneous diagnoses and medical needs. Our study examined only HIV-infected Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, the aforementioned studies(Rothkopf et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2015) did not account for the medical characteristics of the patients, which were some of the strongest predictors of ED use in our study. The finding that medical characteristics were significant predictors in both parts of the model, emphasizes their importance as drivers of overall ED utilization, consistent with prior studies that have found an association between mental health(Choi, DiNitto, Marti, & Choi, 2016; Leserman et al., 2005) and substance abuse(Boyd, Song, Meyer, & Altice, 2015; Josephs et al., 2010) and ED utilization in PLWH. This study is the first to show the important role of tobacco and medical comorbidities in this setting.

Consistent with prior studies, we found that younger age(Kerr, Duffus, & Stephens, 2014) and female gender(Josephs et al., 2010; Kerr et al., 2014) were associated with increased ED utilization. We found a slight impact of greater high school (but not college) graduation rates on ED use. The second part of the model also identified some notable associations. Higher ZIP code income was associated with decreased rate of ED utilization, while urban residence was associated with a higher rate of ED utilization, possibly due to access and proximity to EDs in urban areas. Managed care was associated with a decreased rate, likely due to improved access to a coordinated network of care. Finally, those who see providers with more HIV experience also had lower rates of ED utilization, which emphasizes the importance of provider HIV experience in achieving optimal outcomes.

Our study has some limitations due to the lack of clinical data such as HIV viral load, CD4 counts, and adherence to ART, which were not available as our data were not linked to medical records. As in other studies of claims data, we relied on neighborhood characteristics to proxy an individual’s income and education (Choi et al., 2016; Monuteaux, Mannix, Fleegler, & Lee, 2016). Also, our population only includes California HIV-infected Medicaid beneficiaries, and excludes dual-eligible Medicare-Medicaid patients. Generalizations should not be extended to populations not studied here, who may have different utilization patterns. Finally, the data are from 2008-2009 and do not represent the current trends in ED use among PLWH, but the data are still informative because they provide an important reference point for future studies of PLWH enrolled in the Medicaid and FQHC programs under the ACA.

In a 2014 representative survey of all 58 counties in California, 16.8% of participants reported an ED visit in the last year(UCLA Center for Health Policy Research), whereas close to 50% of our study participants had at least one ED visit, emphasizing the high ED utilization of our study group compared to the general population. Moreover, our data emphasize the large role that FQHCs play in treating HIV-infected Medicaid beneficiaries– close to 40% of our study population received care at a FQHC. In contrast, a nationwide study found that about 14% of 2009 Medicaid beneficiaries received care from FQHCs(Nath, Costigan, & Hsia, 2016). With the implementation of the ACA and the increase in federal funding for FQHCs, it is increasingly crucial to understand the health care utilization of FQHC patients. The ACA’s Medicaid Expansion and Health Insurance Exchanges have given many previously uninsured PLWH access to care from private providers and FQHCs outside of Ryan White sites. Indeed, the proportion of Californians using FQHCs increased by 71.3% between 2005 and 2014(Nath et al., 2016). Our study sets an important baseline for examining changes that the ACA has delivered.

To conclude, our study found that, on average, FQHC users had 0.30 more ED visits per year than non-FQHC users, but this difference was mitigated once medical characteristics were accounted for. Although this unadjusted difference seems small, the average cost of an ED visit was $1233 in 2008(Caldwell, Srebotnjak, Wang, & Hsia, 2013); thus efforts to decrease ED visits could lead to substantial savings at the payer(Medicaid) and clinic (FQHC) level. Our study suggests that successful outpatient management of mental health, substance abuse, tobacco, and chronic medical conditions may be the keys to decreasing ED utilization in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (CHRP) of the University of California (grant RP11-LA-020). This work was also supported by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant P30MH058107; the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) grant 4P30AI028697; and the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000124. Dr. Chow was supported by a NIMH training grant [5T32MH080634-09].

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- The Affordable Care Act and Health Centers. (2012). Retrieved from https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/about/news/2012tables/healthcentersacafactsheet.pdf

- Blair JM, Fagan JL, Frazier EL, Do A, Bradley H, Valverde EE, … Tb Prevention, C. D. C. (2014). Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection - Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2009. MMWR Suppl, 63(5), 1–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd AT, Song DL, Meyer JP, & Altice FL (2015). Emergency department use among HIV-infected released jail detainees. J Urban Health, 92(1), 108–135. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9905-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, & Sullivan MD (2010). Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med, 170(16), 1425–1432. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, & Hsia R (2013). “How much will I get charged for this?” Patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS One, 8(2), e55491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner J, Wu YW, Mehrok N, Gadre A, & Hewner S (2015). Frequent emergency department utilization and behavioral health diagnoses. Nurs Res, 64(1), 3–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BY, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, & Choi NG (2016). Impact of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders on Emergency Department Visit Outcomes for HIV Patients. West J Emerg Med, 17(2), 153–164. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.1.28310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM.). Retrieved from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- HIV Screening and Access to Care: Exploring the Impact of Policies on Access to and Provision of HIV Care. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13057/hiv-screening-and-access-to-care-exploring-the-impact-of [PubMed]

- Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, & Gebo KA (2010). Emergency department utilization among HIV-infected patients in a multisite multistate study. HIV Med, 11(1), 74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00748.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J, Duffus WA, & Stephens T (2014). Relationship of HIV care engagement to emergency department utilization. AIDS Care, 26(5), 547–553. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.844764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D (1992). Zero-Inflated Poisson Regression, with an Application to Defects in Manufacturing. Technometrics, 34(1), 1–14. doi: Doi 10.2307/1269547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz AA, & Desmond K (2015). Identifying a sample of HIV-positive beneficiaries from Medicaid claims data and estimating their treatment costs. Am J Public Health, 105(3), 567–574. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Whetten K, Lowe K, Stangl D, Swartz MS, & Thielman NM (2005). How trauma, recent stressful events, and PTSD affect functional health status and health utilization in HIV-infected patients in the south. Psychosom Med, 67(3), 500–507. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000160459.78182.d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 13- Rural Health Clinic (RHC) and Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Services. (2014). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/bp102c13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mohareb AM, Rothman RE, & Hsieh YH (2013). Emergency department (ED) utilization by HIV-infected ED patients in the United States in 2009 and 2010 - a national estimation. HIV Med, 14(10), 605–613. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monuteaux MC, Mannix R, Fleegler EW, & Lee LK (2016). Predictors and outcomes of pediatric firearm injuries treated in the emergency department: Differences by mechanism of intent. Acad Emerg Med. doi: 10.1111/acem.12986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath JB, Costigan S, & Hsia RY (2016). Changes in Demographics of Patients Seen at Federally Qualified Health Centers, 2005-2014. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondler C, Hegde GG, & Carlson JN (2014). Resource utilization and health care charges associated with the most frequent ED users. Am J Emerg Med, 32(10), 1215–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst JC, Laditka JN, & Laditka SB (2009). Association between community health center and rural health clinic presence and county-level hospitalization rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: an analysis across eight US states. BMC Health Serv Res, 9, 134. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, … Ghali WA, (2005). Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care, 43(11), 1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkopf J, Brookler K, Wadhwa S, & Sajovetz M (2011). Medicaid patients seen at federally qualified health centers use hospital services less than those seen by private providers. Health Aff (Millwood), 30(7), 1335–1342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUCA data: Using RUCA data.). Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2011a). American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1501. Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2011b). American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1903. Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov [Google Scholar]

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Visited emergency room in the past 12 months (California). Retrieved April 21, 2016, from UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; http://ask.chis.ucla.edu [Google Scholar]

- Vuong QH (1989). Likelihood Ratio Tests for Model Selection and Non-Nested Hypotheses. Econometrica, 57(2), 307–333. doi: Doi 10.2307/1912557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright B, Potter AJ, & Trivedi A (2015). Federally Qualified Health Center Use Among Dual Eligibles: Rates Of Hospitalizations And Emergency Department Visits. Health Aff (Millwood), 34(7), 1147–1155. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]