Abstract

Numerous studies have demonstrated a physiological interaction between the mu opioid receptor (MOR) and delta opioid receptor (DOR) systems. A few studies have shown that dual MOR-DOR agonists could be beneficial, with reduced tolerance and addiction liability, but are nearly untested in chronic pain models, particularly neuropathic pain. In this study, we tested the MOR-DOR agonist SRI-22141 in mice in the clinically relevant models of HIV Neuropathy and Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN). SRI-22141 was more potent than morphine in the tail flick pain test, and had equal or enhanced efficacy vs. morphine in both neuropathic pain models, with significantly reduced tolerance. SRI-22141 also produced no jumping behavior during naloxone-precipitated withdrawal in CIPN or naïve mice, suggesting that SRI-22141 produces little to no dependence. SRI-22141 also reduced Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Cyclooxygenase-2 in CIPN in the spinal cord, suggesting an anti-inflammatory mechanism of action. The DOR-selective antagonist naltrindole strongly reduced CIPN efficacy and anti-inflammatory activity in the spinal cord, without affecting tail flick antinociception, suggesting the importance of DOR activity in these models. Overall, these results provide compelling evidence that MOR-DOR agonists could have strong efficacy with reduced side effects and an anti-inflammatory mechanism in the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Mu Opioid Receptor, Delta Opioid Receptor, Neuropathic Pain, HIV Neuropathy, Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathy, Tolerance, Dependence, Anti-Inflammatory, Neuroinflammation

Introduction:

Pharmacological studies over the past few decades have demonstrated physiological interactions between the mu opioid receptor (MOR) and delta opioid receptor (DOR) systems. Inhibition of the DOR by various means had the effect of reducing MOR-mediated side effects like tolerance and dependence.1, 44, 51 Numerous other studies have shown altered activity of MOR- and DOR-selective ligands when the reciprocal receptor is inhibited.29, 35 It is thus clear that the MOR and DOR systems extensively modulate each other, but the mechanisms are not known.

While the mechanisms remain unknown, numerous studies have confirmed that the therapeutic profile of opioids could be improved by simultaneous modulation of the MOR and DOR.1, 44, 51 This led several groups, including the Schiller, Mosberg, and Ananthan groups, to develop MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist compounds.4, 5, 19, 20, 38, 39 These compounds produced anti-nociception in acute pain models with decreased tolerance and dependence, validating the approach.3, 5 Intriguingly however, dual MOR-DOR agonists have also been shown to be beneficial in a small number of studies. The dual agonist MMP-2200 produced anti-nociception with reduced tolerance, dependence, locomotor activation, and self-administration.24, 26, 43 Other MOR-DOR dual agonists have been developed,15, 16, 27, 28, 34 and two showed efficacy in acute tail flick,28, 34 inflammatory,34 and nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain;28, 34 however, they were only tested in acute administration, and opioid side effects were not evaluated.34 This evidence suggests that dual MOR-DOR agonists and MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonists could produce anti-nociception with reduced side effects.

A significant limitation in these studies, however, is that the compounds were mostly tested in acute pain models like tail flick, and not by chronic administration in chronic pain models. In addition, MOR-DOR agonists and MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist compounds could have different efficacy in pain models with an inflammatory component. Neuropathic pain states including Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN) and HIV neuropathy manifest in part through CNS inflammation in the spinal cord and/or brain.49, 50 Relatedly, the DOR has been shown to have a strong anti-inflammatory role in neurons and neuronal tissue.2, 41. These concepts together suggest that MOR-DOR dual agonists could have enhanced efficacy with reduced side effects in pain states with an inflammatory component due to the anti-inflammatory effect mediated by the DOR. This hypothesis has not been tested in the literature, although 2 MOR-DOR dual agonists did show high efficacy with acute administration in inflammatory and neuropathic pain.28, 34

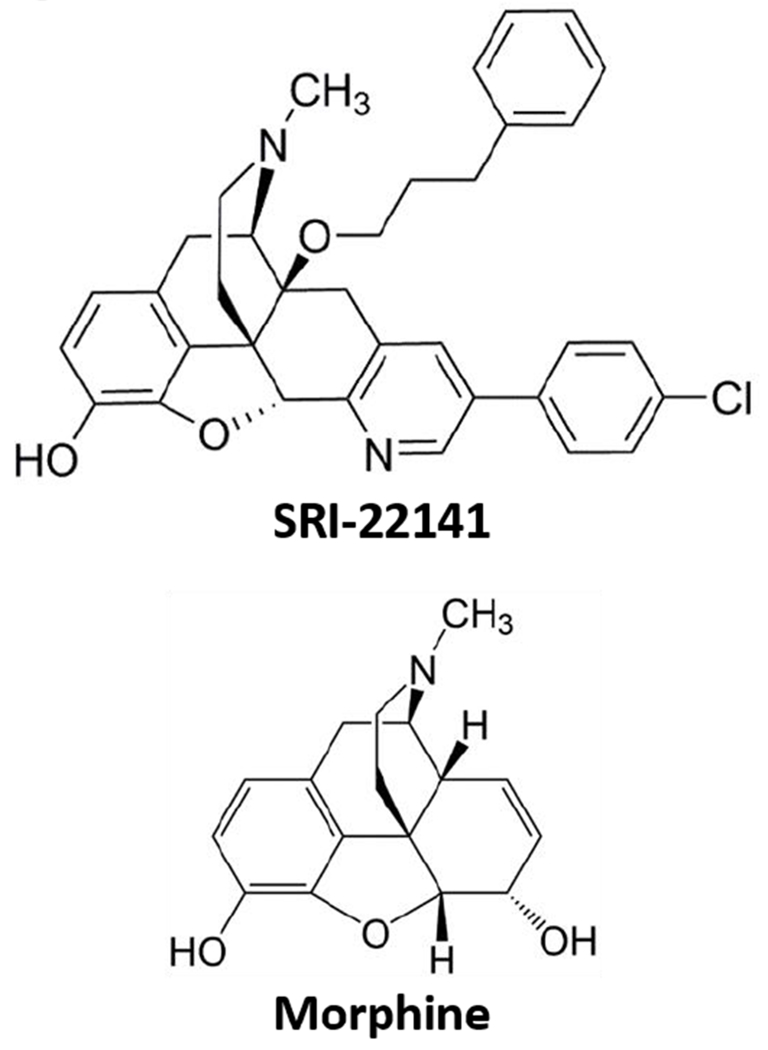

Based on this literature, we hypothesized that a MOR-DOR dual agonist would display high antinociceptive efficacy with anti-inflammatory activity and reduced side effects with chronic administration in neuropathic pain models. We thus evaluated a small molecule dual agonist, SRI-22141 (Figure 1, “17h” in 5), in mouse models of CIPN and HIV neuropathy. SRI-22141 was chosen over the very similar compound 17g from our earlier paper due to the presence of KOR antagonist activity, which may be beneficial.7, 48 We found enhanced anti-nociceptive efficacy with reduced tolerance and significantly reduced dependence/withdrawal, along with an anti-inflammatory effect in CIPN in the spinal cord, although our data did not establish that the anti-inflammatory activity contributed to the efficacy in CIPN. Efficacy in CIPN and anti-inflammatory activity in the spinal cord was strongly reduced by the DOR-selective antagonist naltrindole, without altering tail flick antinociception, suggesting a DOR-mediated mechanism of action in these models. Our findings thus support our hypothesis, and further support the development of MOR-DOR agonists as novel therapeutics with an improved profile for treating neuropathic pain.

Figure 1:

Chemical Structure of SRI-22141

Methods:

Reagents and Materials

SRI-22141 (5′-(4-Chlorophenyl)-6,7-didehydro-4,5α-epoxy-3-hydroxy-17-methyl-14-(3-phenylpropoxy)pyrido[2′,3′:6,7]morphinan) was synthesized and characterized as described previously (5, purity ≥ 95%). DAMGO (#1171), SNC80 (#0764), U50,488 (#0495), Naltrindole (#0740), and Naloxone (#0599) were obtained from Tocris (subsidiary of Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN). Paclitaxel (#J62734MC) was from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Morphine sulfate pentahydrate was obtained from the NIDA Drug Supply Program. Gpl20 IIIb protein was obtained from SPEED BioSystems, LLC (#YCP1549, Gaithersburg, MD). 3H-diprenorphine (NET1121250UC) and 35S-GTPγS (NEG030H250UC) were obtained from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). A βarrestin2-EGFP fusion protein DNA vector was a kind gift from Dr. Larry Barak at the Duke University Addiction Research GPCR Assay Bank. Standard lab chemicals (buffers, etc.) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH) with a minimum purity of ≥ 95%. The vehicles used were: 0.1% DMSO in assay buffer for all drugs in the in vitro experiments; 16.7% cremophor and 16.7% ethanol in USP saline for the paclitaxel; water for icv injections and USP saline for it and ip injections of naloxone and naltrindole; and 10% DMSO, 10% Tween80, 80% USP saline for sc injections of morphine and SRI-22141.

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The MOR-Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell line was purchased from PerkinElmer (#ES-542-C). The DOR-CHO cell line was created and characterized in our lab, as reported in 42 The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) cell line was also created in our lab; an N-terminal 3×-hemagglutinin tagged human KOR expression clone from Genecopoeia was electroporated into parental CHO cells and selected with 500 μg/mL G418. The resulting selected population was enriched for receptor expression by live cell labeling with anti-HA-Alexa488 antibody and separating the top 2% of the population by flow cytometry. This high expressing population was characterized by immunocytochemistry and Western blot to establish receptor expression and expected signal transduction activation. All 3 cell lines were characterized by saturation radioligand binding with 3H-diprenorphine, and the measured KD used in competition binding experiments to calculate the KI (MOR = 5.23 nM; DOR = 0.93 nM; KOR = 1.81 nM; all the mean of N ≥ 3 independent experiments). The MOR- and DOR-βarr2EGFP-U20S cell lines were a kind gift from Dr. Larry Barak as above, and were used by our lab in 43. The MOR-DOR co-expressing CHO cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Jia Bei Wang at the University of Maryland, and is described in 37 The MOR (#93-0213C3) and DOR (#93-0400C3) PathHunter arrestin recruitment lines were obtained from DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA).

CHO cells were maintained in 50:50 DMEM/F12 media, while U20S cells were maintained in MEM media, all with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1× penicillin/streptomycin supplement (all Gibco/ThermoFisher brand) in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere. The PathHunter cells were maintained according to manufacturer’s instructions. Propagation cultures of the MOR-, DOR-, and KOR-CHO cells were further maintained in 500 μg/mL G418; the MOR- and D0R-βarr2EGFP-U20S cells were maintained in 200 μg/mL G418 and 100 μg/mL Zeocin; and the MOR-DOR coexpressing CHO cells were maintained in 500 μg/mL G418 and 250 μg/mL of hygromycin. Cultures were propagated for no more than 20 passages before discarding. All cell lines were monitored for mycoplasma contamination by DAPI staining and confocal microscopy; all experiments reported here were mycoplasma-free.

Competition Radioligand Binding

Competition radioligand binding experiments were performed as reported in 42. Cell pellets of MOR-, DOR-, and KOR-CHO cells for experiments were prepared by growing the cells in 15 cm plates, harvesting with 5 mM EDTA in dPBS (no calcium or magnesium). The cell pellets were stored at −80°C prior to use. Membrane preparations of MOR-, DOR-, or KOR-CHO cells were combined with a fixed concentration of 3H-diprenorphine and a concentration curve of competitor ligand. These reactions were miniaturized to a 200 μL volume in 96 well plates. The reaction proceeded at room temperature for 60 minutes. The reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through 96 well format GF/B filter plates (PerkinElmer) with cold water, washed, dried, and Microscint PS (PerkinElmer) added. The plates were read in a MicroBeta2 96 well format 6 detector scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). The data were normalized to the specific binding caused by 3H-diprenorphine alone (100%) or non-specific binding determined by a 10 μM concentration of known competitor ligand (0%). KI values were calculated using the IC50 of each competitor ligand and the previously established KD of 3H-diprenorphine in each cell line (GraphPad Prism 7.0).

35S-GTPγS Coupling

Agonist mode 35S-GTPγS coupling was also performed as reported in 42. Membrane preparations from cell pellets as above from MOR- and DOR-CHO cells were combined with concentration curves of agonist drug and 0.1 nM 35S-GTPγS in a 200 μL volume. The assay buffer further contained 0.1% BSA and 0.01% Tween80. The reactions were incubated for 60 minutes at 30°C. The reactions were terminated and data collected as above. The data were normalized to the stimulation caused by positive control compound (100%; DAMGO for MOR and SNC80 for DOR) and vehicle (0%). Potency (EC50) and efficacy (EMAX) values were calculated after a 3 variable curve fit using Prism 7.0 (GraphPad).

βarrestin2 Recruitment Assays

Qualitative βarrestin2 (βarr2) recruitment was measured using MOR- and D0R-βarr2EGFP-U20S cells.6 The assays were performed as described in 43. The cells were plated onto bovine collagen type I-coated glass bottom microscopy dishes, and recovered overnight. The cells were serum starved for 1 hour in phenol red- and serum-free culture media. The cells were live-imaged with a Leica SP6 confocal microscope before and 5 minutes after addition of 10 μM of drug. βarr2 recruitment was visualized by the formation of bright green punctae. For the MOR-DOR co-expressing CHO cells, the cells were electroporated with 10 μg per cuvette of βarr2-EGFP DNA vector using a BioRad (Hercules, CA) Gene Pulser XCell, followed by plating, recovery, and imaging as above.

For the quantitative βarr2 recruitment assay using MOR- and DOR-U20S PathHunter cells from DiscoveRx, the manufacturer’s protocol was followed for all steps. The cells were treated with varying concentrations of agonist in 384 well black walled, clear bottomed plates, and the data collected using a BioTek (Winooski, VT) Synergy plate reader. The data were normalized to the stimulation caused by positive control agonist (100%; DAMGO for MOR and SNC80 for DOR) and vehicle (0%). Potency (EC50) and efficacy (EMAX) values were calculated after a 3 variable curve fit using Prism 7.0 (GraphPad).

Animals

Male CD-1 (a.k.a. ICR) mice from 4-8 weeks of age were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). This mouse strain is very commonly used in opioid pharmacology studies (e.g. 5). The mice were habituated to the animal facility for at least 5 days after shipment, and housed no more than 5 per cage in the University of Arizona’s AAALAC-accredited vivarium. Standard lab chow and water were available ad libitum, with temperature and humidity control and a 12 hour light/dark cycle. Laboratory and veterinary staff monitored animals daily for signs of distress. All procedures were approved by the University of Arizona IACUC, and were in accordance with the NUT Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as well as ARRIVE guidelines.

Mouse Behavioral Assays

All behavioral assays were carried out by a single experimenter, who was blinded to treatment group by the delivery of coded drug vials which were not decoded until after all data were collected. Animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups. All behavioral experiments were carried out at the same approximate time of day, in the middle of the animals’ light cycle.

Tail Flick Test

The mouse tail flick test was performed as described in our earlier work,22 with 52°C water and a 10 second cutoff time to prevent tissue damage. SRI-22141 (0.32-10 mg/kg) or morphine (10 mg/kg) was delivered by the subcutaneous (sc) route and tail flick latencies recorded over a time course. For a subset of experiments, naloxone was delivered by the intraperitoneal (30 mg/kg, ip), intrathecal (10 nmol, it), or intracerebroventricular (10 nmol, icv) route, or naltrindole (10 mg/kg) by the ip route, prior to SRI-22141 injection by the sc route and measurement as above. The procedures for it and icv injections are described in 22.

Rotarod Test

The Rotarod test was performed as described in our earlier work.22 The mice were trained for 3 sessions as described on day 0, with drug testing on day 1. On day 1, the mice were tested in a 3 minute trial in an accelerating 4-16 rpm task, and their latency to fall recorded (baseline). The mice were then injected with vehicle, morphine (10 mg/kg), or SRI-22141 (3.2-10 mg/kg), and tested again after 30 minutes, the peak effect time measured in the experiments below.

HIV Neuropathy

Human gp120 protein was injected it for 3 days as described in our published work.22 Mechanical thresholds were measured using Von Frey filaments and the up-down method as described in 13 and our published work.17, 22 Pre-gp120 and pre-opioid injection baselines were also measured. On day 15 after the first injection, SRI-22141 (1-10 mg/kg) or morphine (10 mg/kg) was injected sc twice daily, 8 hours apart, for 3 days. Mechanical thresholds were measured in a time course after each morning injection.

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy

CIPN was induced by the injection of 2 mg/kg paclitaxel ip on days 1, 3, 5, and 7. Opioid treatment began on day 8. Mechanical thresholds were measured as above, including pre-CIPN and pre-opioid injection baseline measurements. SRI-22141 (0.32-10 mg/kg) or morphine (10 mg/kg) was injected sc twice daily, 8 hours apart, for 4 days, with thresholds measured after each morning injection in a time course. In a separate set of experiments, naltrindole (10 mg/kg) was injected ip 5 minutes prior to every SRI-22141 injection during the 4 day time course.

Dependence and Withdrawal

Dependence and withdrawal was measured in the CIPN mice used above (10 mg/kg dose for SRI-22141 and morphine) at the end of the final time course, or in pain-naïve mice injected twice daily with 10 mg/kg sc morphine or SRI-22141 for 4 days. Withdrawal was induced by the injection of 30 mg/kg naloxone ip, as performed in the literature 5 and our previous work,22 3 (CIPN) or 4 (naïve) hours after the final opioid injection. Jumping behavior and gastrointestinal (GI) output was measured over a 20 minute observation period as we previously reported.22

Quantitative RT-PCR

For the qRT-PCR studies, paclitaxel or vehicle control was injected as above, with final testing on day 8. 10 mg/kg of morphine, SRI-22141, or vehicle control was then injected sc with a 4 hour treatment period. In a subset of experiments, naltrindole (10 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected ip 5 minutes prior to the SRI-22141 injection. The mice were sacrificed by rapid cervical dislocation, and the spinal cords removed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. All procedures were performed with all animals from all treatment groups at the same time by the same experimenter to prevent inter-experiment variability. Total RNA was extracted from the spinal cords using TriReagent solution (#AM9738) from Ambion (Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol, with final reconstitution of the RNA in nuclease-free water and storage at −80°C. The RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop TM 2000/2000c Spectrophotomer (Thermo Fisher). 1 μg of total RNA from each animal was reverse transcribed using cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (#43-874-06) from Fisher Scientific, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The qPCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (#A25741) from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) with a Lightcycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Life Science, Indianapolis, IN). The program used was 95°C for 5 min., followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec. and 60°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 2 min. and a melt curve analysis. The primers used were: Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNFα)-F – 5’ CTC TTC AAG GGA CAA GGC TG 3’; TNFα-R – 5’ TGG AAG ACT CCT CCC AGG TA 3’; Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-F – 5’ CCA GAT GCT ATC TTT GGG GA 3’; COX-2-R – 5’ CGC CTT TTG ATT AGT ACT GTA G 3’; Glyceraldehyde Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-F – 5’ TCC TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA G 3’; GAPDH-R – 5’ GAT GAC CTT GCC CAC AGC CTT G 3’. Primers were designed to flank intronic sequences to identify genomic DNA contamination, and analyzed by BLAST to confirm target selectivity. The melt curves were analyzed to confirm one peak per product in each sample to confirm product selectivity, which was further confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis of the products to confirm one product of the correct size. Cycle thresholds (CT) of each target were normalized to the CT of GAPDH for each animal, which was performed together in the same qPCR run. The resulting normalized CTs were transformed by 1/2^CT to generate a relative quantity for each target in each sample.

Data Analysis

All data are reported as the mean ± SEM, with sample sizes and technical replicates reported in the Figure and Table Legends. For the in vitro experiments, replicate wells within a single independent experiment were averaged to generate a mean value considered as N = 1. Affinity, potency, and efficacy values were also calculated separately for each independent experiment, and reported as the mean ± SEM of the independent experiments. For the tail flick and neuropathy time course experiments, the data were analyzed by 2 Way ANOVA (time vs. treatment) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. For the dependence and withdrawal data, the treatment groups (SRI-22141 vs. morphine) were compared within each output measure (jumps and GI) by an unpaired 2-tailed t test. For the Rotarod experiment, the baseline and post-injection groups for each drug were compared using a paired 2-tailed t test. For the qPCR, the treatment groups for each target were compared with a 1 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. In all cases, significance was set as p < 0.05. Tolerance was analyzed in the neuropathy models by generating area under the curve (AUC) values for each drug on each day with the associated SEM using Prism 7.0. These AUC values were plotted for each drug over the 3-4 day time course, and then linear regression analysis performed (Prism 7.0). The calculated x-intercept with associated 95% confidence interval for each regression was used as the estimated time in days to 0 efficacy for each drug in each neuropathy model, and used as the output measure for drug tolerance. Tolerance values were considered significantly different if their confidence intervals did not overlap. For construction of dose/response curves, the maximum possible effect (MPE) was calculated as (((Peak Effect − Baseline)/(Max Effect − Baseline))* 100), and plotted vs. the Log[mg/kg] dose. Linear regression was then performed using Prism 7.0, and the A50 value with associated 95% confidence interval calculated using the method reported in our previous work.22 The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology.14

Results

Molecular Pharmacology Analysis of SRI-22141

We re-tested the molecular pharmacology profile of the putative MOR-DOR dual agonist SRI-22141, which was first characterized and reported as “17h” in 5, using competition radioligand binding and 35S-GTPγS coupling in CHO cells expressing the human MOR, DOR, and KOR. We found that SRI-22141 displayed high affinity orthosteric binding at the DOR (5.1 ± 1.6 nM), MOR (19.7 ± 0.9 nM), and KOR (9.4 ± 2.4 nM; Table 1). Based on these results, we further tested SRI-22141 functional activity at the MOR and DOR, which demonstrated low nM to sub-nM potency (1.3 ± 0.1 nM at DOR; 0.2 ± 0.01 nM at MOR) and high efficacy (73 ± 1.5% at DOR and 118 ± 1.0% at MOR) at both receptors (Table 1). SRI-22141 switches the affinity/potency order at MOR vs. DOR in binding vs. GTPγS; this may reflect a higher intrinsic efficacy for the MOR vs. DOR.9 These results confirm SRI-22141 as a high potency and efficacy MOR-DOR dual agonist.

Table 1: SRI-22141 Displayed High Affinity, Potency, and Efficacy at the MOR and DOR.

Affinity (KI), potency (EC50), and efficacy (EMAX) values at the MOR, DOR, and KOR derived as reported in the Methods. The reported efficacy values were normalized to the stimulation caused by positive control compound (100%; SNC80 for DOR and DAMGO for MOR) and vehicle (0%). Data reported as the mean ± SEM from N = 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate. The positive control compounds (naloxone, U50,488, SNC80, DAMGO) returned expected values in each assay, validating the results.

| Ligand | Binding Affinity – KI (nM) | 35S-GTPγS Agonist Activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOR | MOR | ||||||

| DOR | MOR | KOR | EC50 (nM) | EMAX (%) | EC50 (nM) | EMAX (%) | |

| SRI-22141 | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 19.7 ± 0.9 | 9.4 ± 2.4 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 73 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 118 ± 1.0 |

| Naloxone | 35.8 ± 7.0 | 31.0 ± 1.9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| U50,488 | - | - | 23.9 ± 5.3 | - | - | - | - |

| SNC80 | - | - | - | 112 ± 8.0 | 100 | - | - |

| DAMGO | - | - | - | - | - | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 100 |

Studies on the signaling regulator βarr2 suggest that compounds biased against recruiting this signaling molecule should produce enhanced anti-nociception with reduced side effects, including tolerance and dependence.10, 36, 40 To evaluate βarr2 bias as a potential explanation for SRI-22141 activity, we analyzed the ability of SRI-22141 to recruit βarr2 downstream of the MOR and DOR. Using a qualitative βarr2-EGFP transfluor assay,6 we found that SRI-22141 produced equivalent βarr2 recruitment to the positive control compounds DAMGO and SNC80 in cells expressing the MOR, DOR, or co-expressed MOR and DOR (Figure S1). We further confirmed this finding in a quantitative βarr2 enzyme complementation assay (DiscoveRx PathHunter, as in 8), which demonstrated SRI-22141 βarr2 recruitment at MOR and DOR with high efficacy and potency values within ~2 fold of the positive control compounds DAMGO and SNC80 (Figure S2). These results suggest that SRI-22141 is not a biased agonist, and that its therapeutic profile is not due to βarr2 bias.

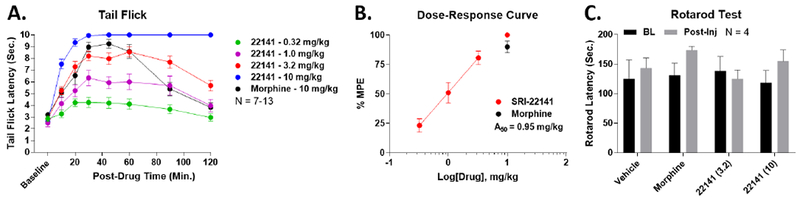

SRI-22141 Induced Potent and Efficacious Anti-Nociception when Administered Systemically

SRI-22141 has only previously been tested once in vivo, with icv administration in mice.5 As systemic administration is far more clinically relevant than icv administration, we tested 4 doses of SRI-22141 delivered sc in acute tail flick pain. We found that SRI-22141 produced efficacious and long-lasting tail flick antinociception with an A50 value of 0.95 mg/kg (Figure 2A–B). By contrast, morphine produced maximal antinociception only at 10 mg/kg, with a general A50 from the literature around 3.2 mg/kg (e.g. 46) We also found that 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 produced very high efficacy anti-nociception, up to the 10 second threshold by 30 minutes, which remained elevated to the 10-second ceiling at the 2 hour time point (Figure 2A). SRI-22141 also produced no apparent motor impairment by Rotarod testing with either 3.2 or 10 mg/kg SRI-22141; morphine also produced no impairment under these conditions (Figure 2C).

Figure 2: Systemic SRI-22141 Produced Potent, Efficacious, and Long-Lasting Acute Anti-Nociception.

CD-1 mice were injected sc with 0.32-10 mg/kg SRI-22141 or 10 mg/kg morphine, and their tail flick latencies recorded over a 2 hour time course (52°C, 10 sec. cutoff). N = 7-13 mice per group, performed in 3 independent technical replicates by the same experimenter. Raw latencies in seconds reported as the mean ± SEM. A) Time courses shown for all doses. 3.2 mg/kg SRI-22141 produced a similar anti-nociceptive profile to 10 mg/kg morphine, while 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 produced maximal anti-nociception in all animals by 30 minutes that persisted for 2 hours. B) The data from A was transformed into % MPE, and graphed as a dose/response curve. The 3 doses in the linear range for SRI-22141 were fit by linear regression, which was used to calculate the potency (A50 = 0.95 mg/kg; 0.64 – 1.31 95% Cl). C) Mice were tested for Rotarod latency to fall in seconds, measured as a baseline and 30 minutes after Vehicle, 10 mg/kg morphine, or 3.2-10 mg/kg SRI-22141 sc injection. N = 4 mice per group performed in 1 technical replicate, reported as the mean ± SEM. No drug treatment caused any significant change in Rotarod latency (p > 0.05).

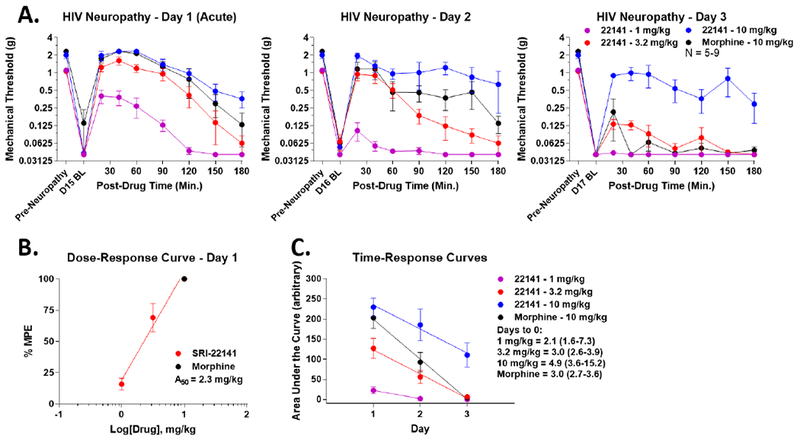

SRI-22141 Induced Efficacious Anti-Nociception with Reduced Tolerance in HIV Neuropathy

To test our hypothesis that MOR-DOR dual agonists possess an improved therapeutic profile in neuropathic pain, we established an HIV neuropathy model (see Methods and 22, 50). The mice displayed very strong mechanical allodynia on day 15 of the pain state, validating the model (baseline measurements in Figure 3A; daily baselines not altered by opioid treatment). We found that on day 1, which would be the first acute injection, both SRI-22141 and morphine produced efficacious and time-dependent anti-nociception that brought the animals back to the pre-gp120 baselines (Figure 3A). On day 1, SRI-22141 demonstrated an A50 potency of 2.3 mg/kg (Figure 3B). The 10 mg/kg morphine and 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 curves completely overlapped on day 1, showing no difference between the drugs. However, on days 2 and 3, while the efficacy of both drugs progressively dropped, morphine dropped much more quickly than SRI-22141. By day 3, morphine had zero efficacy, while SRI-22141 still produced anti-nociception (Figure 3C). Constructing time-response curves for both drugs revealed an estimated time in days to zero efficacy of 3.0 days for morphine and 4.9 days for 10 mg/kg SRI-22141, an increase of 60% for SRI-22141 (Figure 3C, Table 2). These results suggest that while morphine and SRI-22141 have the same initial efficacy in HIV neuropathy pain, SRI-22141 produces much less tolerance.

Figure 3: SRI-22141 Produced Efficacious Anti-Nociception with Reduced Tolerance in HIV Neuropathic Pain.

CD-1 mice had neuropathic pain induced by it injection of gpl20 protein over 3 days (see Methods). On day 15, morphine (10 mg/kg) or SRI-22141 (1-10 mg/kg) were injected sc twice daily, separated by 8 hours, for 3 days. Mechanical thresholds were measured using Von Frey filaments prior to and in a time course after each morning injection. Day 15 baselines were strongly reduced to near-zero levels from pre-gpl20 baselines, validating the pain state. Opioid treatment did not change the daily baselines (p > 0.05). N = 5-9 mice/group, performed in 2 technical replicates. Data reported as the mean ± SEM. A) Morphine vs. SRI-22141 time courses are shown for each day. Day 1 represents an acute injection and response without any chronic opioid treatment. 10 mg/kg Morphine and 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 had the same efficacy and time course on day 1, but morphine dropped off rapidly while SRI-22141 dropped more slowly over time. B) The data from A was transformed into %MPE and used to calculate the acute potency of SRI-22141 on day 1 as for the tail flick experiment above in Figure 2. A50 = 2.3 mg/kg; 1.7 – 3.0 95% CI. C) AUC data were calculated from each time course curve for both drugs, and reported as the mean ± SEM over the 3 day period. Linear regression was performed, and the x-intercept with 95% CI for each drug curve used as the estimate of time in days to 0 efficacy. 10 mg/kg Morphine = 3.0 (2.7-3.6) days, SRI-22141 = 4.9 (3.6-15.2) days, a significant increase of 60%, demonstrating less tolerance by SRI-22141. Potency and tolerance values summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of In Vivo Potency and Tolerance Values for SRI-22141.

Potency (A50) and tolerance (days to zero efficacy) values calculated from Figures 2–4. Values reported with 95% CI.

| Pain Model | Acute A50 mg/kg (95% CI) | Tolerance – Days to Zero Efficacy (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRI-22141 0.32 mg/kg |

SRI-22141 1 mg/kg |

SRI-22141 3.2 mg/kg |

SRI-22141 10 mg/kg |

Morphine 10 mg/kg |

||

| Tail Flick | 0.95 (0.64–1.3) | - | - | - | - | - |

| HIV Neuropathy | 2.3 (1.7-3.0) | - | 2.1 (1.6-7.3) | 3.0 (2.6-3.9) | 4.9 (3.6-15.2)# | 3.0 (2.7-3.6) |

| CIPN | 0.83 (0.70-0.97) | 2.1 (1.7-7.2) | 2.3 (1.9-3.7) | 4.3 (3.8-5.2)#& | 5.2 (4.3-9.4)#& | 2.2 (1.9-3.3) |

Significantly different from morphine comparison (non-overlapping CI).

Significantly different from 1 mg/kg SRI-22141 in same pain type (non-overlapping CI).

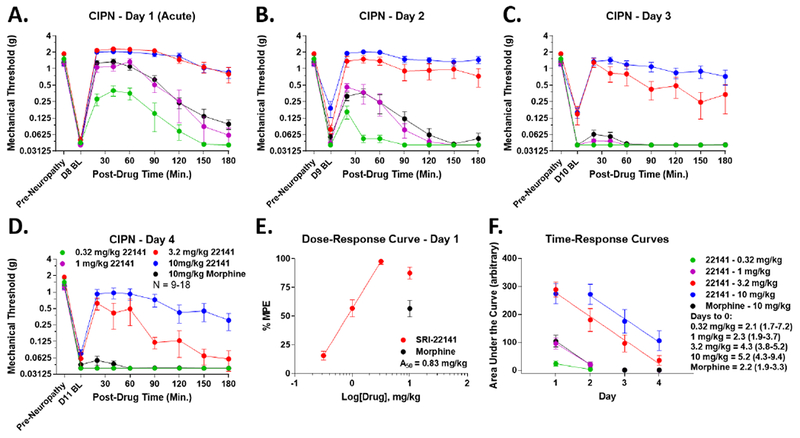

SRI-22141 Demonstrated Enhanced Efficacy with Reduced Tolerance in CIPN

We next tested SRI-22141 in an alternate neuropathy model, the highly clinically relevant CIPN pain model (see 49). The mice displayed strong mechanical allodynia on day 8, validating the model, and daily baselines were not altered by opioid treatment (Figure 4A–D). Interestingly, during the acute injection stage on day 1, both doses of SRI-22141 showed strongly enhanced anti-nociception with a dose-ceiling effect, implying that both doses have maximal efficacy in increasing anti-nociception over morphine (Figure 4A, AUC increase of 165.2% for 3.2 mg/kg and 151.9% for 10 mg/kg of SRI-22141 over 10 mg/kg morphine). This was despite SRI-22141 showing equivalent efficacy to 10 mg/kg morphine in the tail flick test at 3.2 mg/kg (Figure 2) and in HIV neuropathy at 10 mg/kg (Figure 3), suggesting that SRI-22141 is highly efficacious and more potent than morphine in this neuropathic pain type. The day 1 acute potency A50 of SRI-22141 in CIPN pain was 0.83 mg/kg, supporting this conclusion (Figure 4E). The efficacy of morphine rapidly dropped to near zero effect on day 2, while the efficacy of SRI-22141 remained elevated and slowly declined, still producing modest antinociception on day 4 at some doses (Figure 4A–D). Time-response curve analysis revealed a time to zero efficacy of 2.2 days for morphine, 4.3 days for 3.2 mg/kg SRI-22141 (95.5% increase), and 5.2 days for 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 (136.4% increase; Figure 4F, Table 2), both significantly different from morphine. The 0.32 and 1 mg/kg doses were not significantly different from morphine (Figure 4F, Table 2) These results suggest that SRI-22141 induces both higher anti-nociceptive efficacy and much less tolerance than morphine in CIPN pain.

Figure 4: SRI-22141 Produced Enhanced Efficacy with Reduced Tolerance in CIPN.

CD-1 mice had CIPN induced by ip injection of 2 mg/kg paclitaxel on days 1, 3, 5, and 7. On day 8, 0.32-10 mg/kg SRI-22141 or 10 mg/kg morphine was injected sc twice daily, separated by 8 hours, for 4 days. Mechanical thresholds were measured using Von Frey filaments prior to and in a time course after each morning injection. Day 8 baselines were strongly reduced to near-zero levels from pre-CIPN baselines, validating the pain state. Opioid treatment did not change the daily baselines (p > 0.05). N = 9-18 mice/group, performed in 2 or 4 independent technical replicates by the same experimenter. Data reported as the mean ± SEM. A-D) Morphine vs. SRI-22141 time courses are shown for each day. Day 1 represents an acute injection and response without any chronic opioid treatment. The 3.2 and 10 mg/kg doses of SRI-22141 demonstrated enhanced efficacy vs. morphine on day 1 (AUC increase of 165.2% for 3.2 mg/kg and 151.9% for 10 mg/kg of SRI-22141 over 10 mg/kg morphine). Morphine dropped to near-zero efficacy on day 2, while the 3.2 and 10 mg/kg doses of SRI-22141 fell more slowly, with 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 staying elevated over 3.2 mg/kg on days 2-4. E) The data from A-D was transformed into %MPE and used to calculate the acute potency of SRI-22141 on day 1 as for the tail flick experiment above in Figure 2. A50 = 0.83 mg/kg; 0.70 – 0.97 95% CI. F) AUC data were calculated from each time course curve for both drugs and all doses, and reported as the mean ± SEM over the 4 day period. Linear regression was performed using dose and time points in the linear time-response range, and the x-intercept with 95% Cl for each drug curve used as the estimate of time in days to 0 efficacy. Morphine = 2.2 (1.9-3.3) days, 3.2 mg/kg SRI-22141 = 4.3 (3.8-5.2) days (95.5% increase), and 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 = 5.2 (4.3-9.4) days (136.4% increase); both doses are significantly increased vs. morphine, while the 0.32 and 1 mg/kg doses were not significantly different. Potency and tolerance values summarized in Table 2.

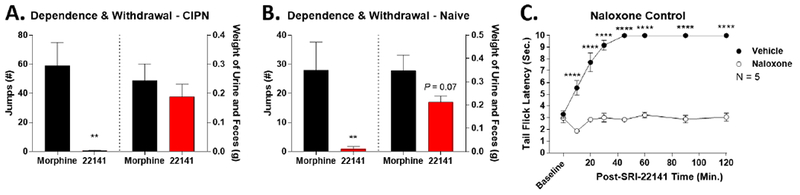

SRI-22141 Produced Very Little Dependence and Withdrawal

While SRI-22141 produced maintained or enhanced efficacy with reduced tolerance in neuropathic pain, this would be of limited therapeutic benefit if other opioid-mediated side effects were also increased. We thus tested SRI-22141 for the propensity to produce dependence and naloxone-precipitated withdrawal. We tested the 10 mg/kg morphine and SRI-22141 groups to maximize the chances of detecting dependence. The morphine treated CIPN mice produced a robust jumping and GI output response, suggesting robust dependence and withdrawal (Figure 5A, also see 22 among others). In contrast, SRI-22141 produced almost no jumping behavior in naloxone injected mice, with equivalent GI output to the morphine mice (Figure 5A). We also tested whether pain-naïve mice would react similarly to repeated SRI-22141 treatment. Similarly to the CIPN mice, morphine produced robust jumping and GI output behavior, while SRI-22141 again produced almost no jumping behavior (Figure 5B). There was a trend for SRI-22141 to produce less GI output in the naïve withdrawal mice, but this effect did not rise to the level of significance (p = 0.07; Figure 5B). Lastly, as SRI-22141 at 10 mg/kg produced a very strong effect in the tail flick test (Figure 2), we performed a control experiment to test whether 30 mg/kg naloxone was capable of blocking SRI-22141 at 10 mg/kg from interacting with the MOR. We found that 30 mg/kg naloxone ip completely prevented 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 from producing tail flick anti-nociception, validating our withdrawal dose of naloxone (Figure 5C). These results suggest that SRI-22141 produces strongly reduced dependence and withdrawal behavior, further supporting SRI-22141 as a neuropathic pain therapeutic with reduced side effects.

Figure 5: SRI-22141 Produced Very Little Dependence and Withdrawal.

A) The CIPN mice from Figure 4 treated with 10 mg/kg morphine or 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 were injected with 30 mg/kg naloxone ip at the end of the behavioral time course, 3 hours after the final opioid injection. Withdrawal behaviors were observed and quantified for 20 minutes. Data reported as the mean ± SEM of N = 9-10 mice/group, performed in 2 independent technical replicates by the same experimenter. ** = p < 0.01 vs. morphine group by unpaired 2-tailed t test. SRI-22141 produced essentially no jumping behavior, but the same GI output as morphine. B) Pain-naïve CD-1 mice were injected twice daily with 10 mg/kg morphine or SRI-22141, 8 hours apart, for 4 days – the same injection regimen as in A except without the pain state. Four hours after the final injection on day 4, the mice were injected with naloxone and recorded as above. Data reported as the mean ± SEM of N = 9-10 mice/group, performed in 2 independent technical replicates by the same experimenter. ** = p < 0.01 vs. morphine group by unpaired 2-tailed t test. SRI-22141 produced essentially no jumping behavior, with a near-significant trend to produce less GI output than morphine (p = 0.07). C) As a control for the ability of 30 mg/kg naloxone to block 10 mg/kg SRI-22141, naïve CD-1 mice were injected with 30 mg/kg naloxone or vehicle ip, with a 10 minute treatment period, followed by 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 sc and a tail flick time course performed as in Figure 2. Data reported as the mean ± SEM of N = 5 mice/group performed in 1 technical replicate. **** = p < 0.0001 vs. same time point naloxone group by 2 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test.

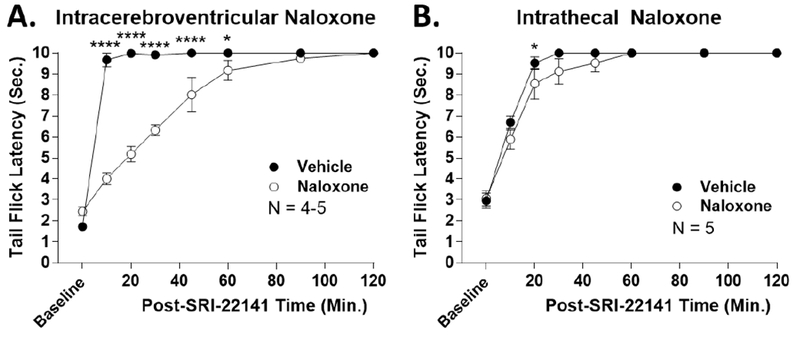

SRI-22141 Penetrates Into the CNS

In all our evaluations, SRI-22141 was injected sc, which does not test whether SRI-22141 penetrates into the CNS or produces its effects via central or peripheral mechanisms. We thus tested for CNS penetration by icv or it delivery of 10 nmol of naloxone to the brain or spinal cord followed by 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 sc and the tail flick test. We found that icv naloxone strongly reduced SRI-22141 tail flick anti-nociception at the earliest time point of 15 minutes; however this effect was nearly gone by 60 minutes and naloxone had no inhibitory effect beyond 60 minutes (Figure 6A). By contrast, it naloxone had almost no inhibitory effect on SRI-22141; there was a significant difference at the 20 minute time point, but the AUC effect size was very small (vehicle group = 100%; naloxone group = 95.4%, a 4.6% decrease; Figure 6B). These results are elaborated further in the Discussion, but do strongly suggest that SRI-22141 can penetrate into the CNS to produce anti-nociception.

Figure 6: SRI-22141 Penetrates Into the CNS to Produce Anti-Nociception.

CD-1 mice were icv (A) or it (B) injected with 10 nmol naloxone or vehicle with a 10 minute treatment time, followed by 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 sc and a tail flick time course as in Figure 2. Data reported as the mean ± SEM with one technical replicate performed for each experiment. *, **** = p< 0.05, 0.0001 vs. same time point naloxone group by 2 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. A) Icv injection group, N = 4-5 mice/group. Naloxone produced strong reversal of anti-nociception at early time points, but the effect progressively diminished over time and was gone after 60 minutes. B) It injection group, N = 5 mice/group. Naloxone produced essentially no blockade of anti-nociception. There was a significant difference at the 20 minute time point, but the effect size was very small – the naloxone group had an AUC of 95.4% of the vehicle group, only a 4.6% reduction.

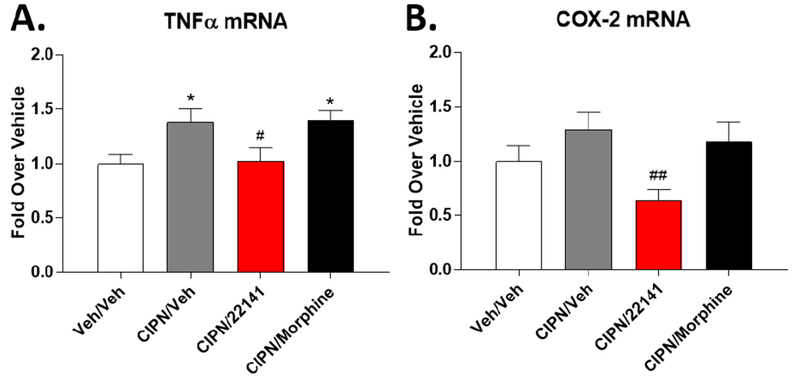

SRI-22141 Causes an Anti-Inflammatory Effect in the Spinal Cord

Per our hypothesis, we tested for the ability of SRI-22141 to reduce inflammation in a neuropathic pain state. We found that TNFα mRNA was increased by CIPN, and morphine injection did not alter this increased inflammatory mRNA level; by contrast, SRI-22141 treatment reduced TNFα mRNA levels to vehicle sham control levels, suggesting that SRI-22141 has an anti-inflammatory effect in CIPN (Figure 7A). COX-2 mRNA levels showed a similar pattern, with SRI-22141 strongly reducing COX-2 mRNA vs. the CIPN/Vehicle and CIPN/Morphine groups; however, while increased, CIPN/Vehicle and CIPN/Morphine groups were not significantly different from Vehicle/Vehicle controls (Figure 7B). These results suggest that SRI-22141 has a unique anti-inflammatory effect vs. the standard MOR agonist morphine, further supporting our hypothesis that MOR-DOR dual agonists may produce anti-nociception with reduced side effects in neuropathic pain via DOR-mediated anti-inflammation, although these results do not causally establish this link.

Figure 7: SRI-22141 Reduces Inflammatory Activation in the Spinal Cord in CIPN.

CD-1 mice were injected with paclitaxel or vehicle as in Figure 4 to produce CIPN (CIPN/ groups) or a sham pain state (Veh/Veh group). On day 8, mice were injected with vehicle, 10 mg/kg morphine, or 10 mg/kg SRI-22141 sc with a 4 hour treatment period, followed by spinal cord removal and analysis by qRT-PCR (see Methods). Inflammatory marker mRNA was normalized to GAPDH levels within each animal and further normalized to the Veh/Veh group. Data reported as the mean ± SEM of N = 5 mice/group performed in 1 technical replicate. * = p < 0.05 vs. Veh/Veh group; #, ## = p < 0.05, 0.01 vs. CIPN/Veh and CIPN/Morphine groups, both by 1 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. A) Quantification of TNFα mRNA. CIPN induces TNFα mRNA levels over the Veh/Veh group. Morphine does not change the TNFα level in CIPN, but SRI-22141 reduces TNFα mRNA levels back to that seen in the Veh/Veh group. B) Quantification of COX-2 mRNA. CIPN/Veh and CIPN/Morphine have a trend to increase COX-2 levels over the Veh/Veh group in a similar pattern to that seen in A, but the effect is not significant. However, SRI-22141 in CIPN strongly decreases COX-2 mRNA vs. the CIPN/Veh and CIPN/Morphine groups (p < 0.01), demonstrating an anti-inflammatory effect of SRI-22141 in CIPN. The mean in the CIPN/22141 group is below that of the Veh/Veh group.

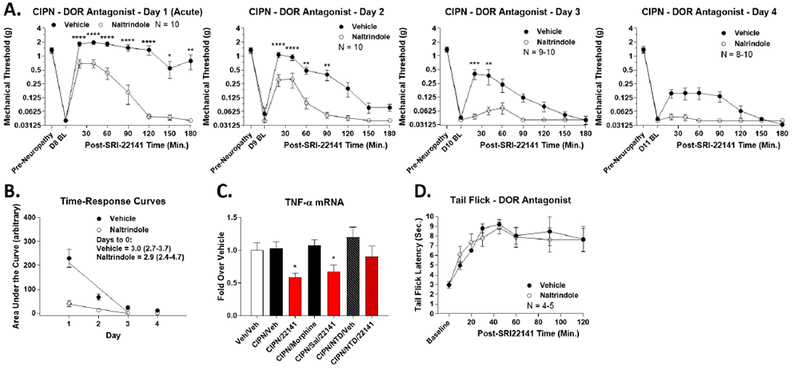

SRI-22141 Acts Through the DOR to Promote CIPN Anti-Nociception and Anti-Inflammation

The effects observed above are consistent with our hypothesis that the DOR is anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive in neuropathic pain, but the link has not been directly established. We thus tested the impact of the DOR-selective antagonist naltrindole (10 mg/kg, ip) on the activity of SRI-22141. First, we tested the impact of naltrindole on SRI-22141 anti-nociception and tolerance in CIPN. We found that even with acute injection on day 1, naltrindole treatment strongly reduced the anti-nociception caused by 3.2 mg/kg SRI-22141 (Figure 8A). This difference persisted throughout the 4 day treatment period. Time-response analysis over the treatment period revealed a time to zero efficacy of 3.0 days with Vehicle and 2.9 days with Naltrindole treatment, which were not significantly different (Figure 8B). This may suggest that naltrindole blocks antinociception without blocking tolerance, although the efficacy of SRI-22141 is very strongly reduced by naltrindole, meaning the tolerance analysis may not be accurate. We next tested the impact of naltrindole on SRI-22141 anti-inflammatory activity in the spinal cord. We found that naltrindole alone had no effect, but reversed the decrease in TNFα caused by SRI-22141 back to baseline (Figure 8C). This data supports our hypothesis that SRI-22141 has anti-inflammatory activity in the spinal cord through activating the DOR. Lastly, we tested the impact of naltrindole on SRI-22141 anti-nociception in naïve tail flick pain. We found no impact of naltrindole on this type of anti-nociception, suggesting that SRI-22141 acts through DOR in neuropathic pain but not naïve pain, and further helps to support this dose of naltrindole as DOR-selective (Figure 8D).

Figure 8: SRI-22141 Acts Through the DOR to Promote Anti-Nociception and Anti-Inflammatory Activity in CIPN.

CD-1 mice used for all experiments, data reported as the mean ± SEM. A) CIPN was induced and measured with drug injected as in Figure 4. Naltrindole (10 mg/kg, ip) or Vehicle was injected 5 minutes prior to each SRI-22141 (3.2 mg/kg, sc) injection. N = 8-10 mice/group performed in 2 independent technical replicates by the same experimenter. Naltrindole treatment caused a strong reduction in SRI-22141 anti-nociception with the first acute treatment that persisted throughout the 4 day treatment period. *, **, ***, **** = p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 vs. same time point Naltrindole group by 2 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. B) AUC data from A was used to create time-response curves, analyzed as in Figures 3–4, with x-intercept with 95% Cl used to estimate the time to zero efficacy. Vehicle = 3.0 (2.7-3.7) days; Naltrindole = 2.9 (2.4-4.7) days; not significantly different. C) CIPN or Sham was established, followed by Naltrindole (10 mg/kg, ip) or Vehicle for 5 minutes, then morphine or SRI-22141 (10 mg/kg, sc) for 4 hours, and TNFα mRNA measured in the spinal cord by qPCR, all as in Figure 7. N = 4-5 mice/group in 1 technical replicate. * = p < 0.05 vs. Veh/Veh group by 1 Way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post-hoc test. Naltrindole treatment reverses the decrease in TNFα mRNA caused by SRI-22141. D) Naïve mice injected with Naltrindole (10 mg/kg, ip) or Vehicle followed by SRI-22141 (3.2 mg/kg, sc) and tail flick analysis performed as in Figure 2. N = 4-5 mice/group in 1 technical replicate. No differences between treatment groups (p > 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we report that the MOR-DOR dual agonist morphinan compound SRI-22141 is a promising potential therapeutic to develop for neuropathic pain. SRI-22141 induces potent and long-lasting anti-nociception when administered systemically (Figure 2), and displays sustained efficacy in HIV neuropathic pain (Figure 3) and strongly enhanced efficacy in CIPN (Figure 4). SRI-22141 further produces significantly less tolerance in both pain states, along with strongly reduced dependence and withdrawal (Figure 5). SRI-22141 penetrates the CNS to produce anti-nociception (Figure 6), and reduces inflammatory activation caused by CIPN in the spinal cord (Figure 7). SRI-22141 also promotes anti-nociception in CIPN and anti-inflammatory activity in the spinal cord through activating the DOR (Figure 8). These findings support our hypothesis that MOR-DOR dual agonists are efficacious in neuropathic pain at least in part through DOR-mediated anti-inflammation, although this link was not directly tested in this study. These findings also suggest that MOR-DOR dual agonists could potentially be developed as therapeutics for neuropathic pain with enhanced efficacy and reduced side effects. However, not all side effects are absent in SRI-22141, suggesting that DOR modulation is beneficial, but cannot overcome all negative effects. This limitation should be kept in mind for further development of this compound class.

The few earlier in vivo studies with MOR-DOR dual agonists have either studied side effects like tolerance and dependence in pain-naïve mice using assays such as tail flick,21, 24 or administered the agonists acutely in chronic pain states like nerve injury-induced neuropathy without chronic agonist administration or side effect testing.28, 34 Other MOR-DOR dual agonists have been reported, but were not tested in vivo.27 Notably, the MOR-DOR dual agonist UFP-505 was recently published in the British Journal of Pharmacology, and showed no improvement in opioid tolerance; this could be due to the fact that UFP-505 is a partial agonist at the DOR instead of a full agonist as in most other studies.16 To our knowledge, our current study is the first one to test a MOR-DOR dual agonist with chronic administration in clinically relevant pain states (Figures 3–4), profile tolerance and dependence/withdrawal in these chronic pain states (Figures 3–5), and demonstrate an anti-inflammatory effect of a MOR-DOR dual agonist (Figure 7). Our study is also the first one to demonstrate significantly increased efficacy of a MOR-DOR dual agonist in a neuropathic pain state (Figure 4). Our study thus advances significantly beyond the earlier studies and provides strong support for the development of MOR-DOR agonists as therapeutics for neuropathic pain with reduced side effects.

Our molecular pharmacology analysis of SRI-22141 (Table 1) is in close agreement with the initial characterization first reported in the literature.5 Our binding values are somewhat shifted to a lower affinity, but still in the low nanomolar range, and further agree with the earlier findings that demonstrate little selectivity between the MOR, DOR, and KOR for SRI-22141. Our functional 35S-GTPγS analysis also closely matches these earlier findings, including confirming DOR efficacy in the 70-80% range and enhanced MOR efficacy in the range of 120%. This enhanced MOR efficacy bears further investigation, and could potentially be partly responsible for the enhanced efficacy observed in CTPN (Figure 4); although this may be less likely as the DOR antagonist naltrindole very strongly reduced SRI-22141 anti-nociception in CTPN (Figure 8). This earlier study also identified SRI-22141 as a KOR antagonist, which should also be investigated as a potential source of enhanced anti-nociception and/or reduced side effects in certain pain states such as migraine; although our results with naltrindole suggest that the DOR can explain much if not all of the efficacy of SRI-22141 in CIPN anti-nociception and anti-inflammation (Figure 8).30, 48

Our further molecular pharmacology analysis suggested that SRI-22141 potently and efficaciously recruited βarr2 downstream of the MOR and DOR, ruling out bias as a mechanism for improved side effects (Figures S1–S2). The earlier study with SRI-22141 also showed that the compound produced tolerance in in vitro models, as well as cAMP overshoot, an in vitro marker for dependence liability.5 Despite these in vitro results, we found that SRI-22141 produced less tolerance and strongly reduced dependence and withdrawal in vivo (Figures 3–5). These results are highly reminiscent of the MOR-DOR dual agonist MMP-2200, which we found in an earlier study efficaciously recruited βarr2 downstream of the MOR and DOR, and also produced in vitro tolerance and cAMP overshoot, and yet also showed reduced tolerance and dependence in vivo.24, 43 This disparity between the in vitro and in vivo results for these MOR-DOR dual agonists suggests that their improved profile may not be due to molecular interactions with the receptors in a single cell, but due to higher order interactions, perhaps at the circuit level, or perhaps due to the anti-inflammatory activity we have identified (Figure 7). Interestingly, a MOR agonist/DOR antagonist compound did show a lack of tolerance and cAMP overshoot in in vitro models, potentially identifying a significant mechanistic difference between these classes of compounds.5

We also observed a disparity in the dependence and withdrawal produced by SRI-22141 in that the drug produced almost no jumping behavior, but the same GI output after withdrawal as morphine (Figure 5). Jumping behavior is the most robust sign associated with opioid withdrawal, and was linked to the amygdala in early studies;12, 45 while GI output (diarrhea, etc.) has also been linked to brain structures in these early studies, the main site of action is thought to be the intestines.11, 18 This disparity of site of action in withdrawal and comparison to our data suggests that SRI-22141 produces a beneficial MOR-DOR interaction in the brain to eliminate jumping withdrawal behavior, but this beneficial interaction is not present in the intestines. Thus in clinical use SRI-22141 might be expected to produce constipation therapeutically, and GI activation upon withdrawal, but not brain symptoms of dependence and withdrawal analogous to jumping behavior in mice.

Our CNS penetration test revealed interesting differences between the brain and spinal cord (Figure 6). Brain delivered naloxone did strongly block SRI-22141 anti-nociception, although this effect was fully reversed past one hour (Figure 6A). This reversal is likely due to the fact that naloxone has a short duration of action with icv delivery, typically gone by 1 hour (e.g. 25), while SRI-22141 at 10 mg/kg produced full antinociception past 2 hours (Figure 2). This result strongly suggests that SRI-22141 can penetrate into the CNS, and produces anti-nociception, at least in part, through binding to MOR and/or DOR in the brain; however, the test does not rule out partial peripheral activity by SRI-22141. On the other hand, spinal cord delivered naloxone had essentially no effect on SRI-22141 anti-nociception (Figure 6B). This result however does not invalidate the importance of the anti-inflammatory effects we detected by SRI-22141 in the spinal cord (Figure 7). First, our intrathecal naloxone testing was in tail flick pain, which might produce different results in neuropathic pain; this is supported by our finding that naltrindole strongly reduced SRI-22141 anti-nociception in CIPN but had no impact on tail flick (Figure 8). Second, an anti-inflammatory effect in the spinal cord still could have an anti-nociceptive effect in neuropathic pain by decreasing spinal sensitization at the afferent or interneuronal synapses, without producing direct anti-nociception in the spinal cord through MOR and/or DOR.47 Either way, the main CNS site for producing direct, acute tail flick anti-nociception by SRI-22141 appears to be the brain.

Lastly, the anti-inflammatory effect we observed in the spinal cord (Figure 7) is consistent with the observed role for the DOR in reducing inflammation; this is further supported by our finding that naltrindole blocked the anti-inflammatory effect of SRI-22141 (Figure 8).2, 41 This effect is consistent with our hypothesis that MOR-DOR dual agonists could act in part through an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Neuropathic pain states, including HIV neuropathy and CIPN, have been shown to induce inflammation with similar effect sizes to that we observed.49, 50 Reducing inflammation in neuropathic pain states, such as by activating cannabinoid type-2 receptors, has been shown to reduce the duration or extent of the pain state and/or produce antinociception.31 Importantly, both opioid tolerance and dependence have been shown to be associated with neuroinflammation, and reducing this inflammation reduces the tolerance and dependence.23, 32 Applying this background to our results suggests that SRI-22141, and perhaps other MOR-DOR dual agonists, could produce high efficacy agonism in neuropathic pain with reduced tolerance and dependence through MOR-DOR direct anti-nociception combined with DOR-mediated anti-inflammation. One caveat is that SRI-22141 could potentially produce less tolerance through its very high efficacy at MOR (Table 1) as opposed to any action at DOR; high MOR efficacy has been shown to reduce tolerance.33 Future studies will be needed to identify the mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effect we observed, and whether it enhances efficacy and reduces tolerance and dependence in neuropathic pain. Meanwhile, these results provide support for further preclinical and clinical development of SRI-22141 and other MOR-DOR dual agonists as novel treatments for neuropathic pain with significantly reduced side effects.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A Mu-Delta Opioid agonist SRI-22141 displays enhanced efficacy in neuropathic pain.

SRI-22141 displays greatly reduced tolerance and dependence vs. morphine.

SRI-22141 also has an anti-inflammatory effect in chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

Efficacy and anti-inflammation effects are mediated by the Delta Opioid Receptor.

Perspective:

This study demonstrates that a MOR-DOR dual agonist given chronically in chronic neuropathic pain models has enhanced efficacy with strongly reduced tolerance and dependence, with a further anti-inflammatory effect in the spinal cord. This suggests that MOR-DOR dual agonists could be effective treatments for neuropathic pain with reduced side effects.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Gabriella Molnar for technical assistance with the binding and 35S-GTPγS coupling.

Disclosures: Dr. Streicher and Dr. Ananthan report grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DA008883; R01DA038635), during the conduct of the study; a grant from Depomed, Inc., grant from Stealth Biotherapeutics, and an ownership stake in Teleport Pharmaceuticals, LLC, outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Ananthan has a patent US 9,163,030 issued. Institutional funds from the University of Arizona (to JMS) also supported this work.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- βarr2

βarrestin2

- CIPN

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy

- CT

Cycle Threshold

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- MOR, DOR, KOR

Mu, Delta, and Kappa Opioid Receptors

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Abdelhamid EE, Sultana M, Portoghese PS, Takemori AE. Selective blockage of delta opioid receptors prevents the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 258:299–303, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhter N, Nix M, Abdul Y, Singh S, Husain S. Delta-opioid receptors attenuate TNF-alpha-induced MMP-2 secretion from human ONH astrocytes. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 54:6605–6611, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand JP, Boyer BT, Mosberg HI, Jutkiewicz EM. The behavioral effects of a mixed efficacy antinociceptive peptide, VRP26, following chronic administration in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 233:2479–2487, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananthan S, Kezar HS 3rd, Carter RL, Saini SK, Rice KC, Wells JL, Davis P, Xu H, Dersch CM, Bilsky EJ, Porreca F, Rothman RB. Synthesis, opioid receptor binding, and biological activities of naltrexone-derived pyrido- and pyrimidomorphinans. J Med Chem. 42:3527–3538, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ananthan S, Saini SK, Dersch CM, Xu H, McGlinchey N, Giuvelis D, Bilsky EJ, Rothman RB. 14-Alkoxy- and 14-acyloxypyridomorphinans: mu agonist/delta antagonist opioid analgesics with diminished tolerance and dependence side effects. J Med Chem. 55:8350–8363, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barak LS, Ferguson SS, Zhang J, Caron MG. A beta-arrestin/green fluorescent protein biosensor for detecting G protein-coupled receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 272:27497–27500, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beardsley PM, Howard JL, Shelton KL, Carroll FI. Differential effects of the novel kappa opioid receptor antagonist, JDTic, on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking induced by footshock stressors vs cocaine primes and its antidepressant-like effects in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 183:118–126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beguin C, Potuzak J, Xu W, Liu-Chen LY, Streicher JM, Groer CE, Bohn LM, Carlezon WA, Jr., Cohen BM. Differential signaling properties at the kappa opioid receptor of 12-epi-salvinorin A and its analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 22:1023–1026, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black JW, Leff P. Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 220:141–162, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science. 286:2495–2498, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohn LM, Raehal KM. Opioid receptor signaling: relevance for gastrointestinal therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 6:559–563, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvino B, Lagowska J, Ben-Ari Y. Morphine withdrawal syndrome: differential participation of structures located within the amygdaloid complex and striatum of the rat. Brain Res. 177:19–34, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 53:55–63, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA, Gilchrist A, Hoyer D, Insel PA, Izzo AA, Lawrence AJ, MacEwan DJ, Moon LD, Wonnacott S, Weston AH, McGrath JC. Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol. 172:3461–3471, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietis N, McDonald J, Molinari S, Calo G, Guerrini R, Rowbotham DJ, Lambert DG. Pharmacological characterization of the bifunctional opioid ligand H-Dmt-Tic-Gly-NH-Bzl (UFP-505). British journal of anaesthesia. 108:262–270, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietis N, Niwa H, Tose R, McDonald J, Ruggieri V, Filaferro M, Vitale G, Micheli L, Ghelardini C, Salvadori S, Calo G, Guerrini R, Rowbotham DJ, Lambert DG. In vitro and in vivo characterisation of the bifunctional MOP/DOP ligand UFP-505. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards KA, Havelin JJ, McIntosh MI, Ciccone HA, Pangilinan K, Imbert I, Largent-Milnes TM, King T, Vanderah TW, Streicher JM. A Kappa Opioid Receptor Agonist Blocks Bone Cancer Pain Without Altering Bone Loss, Tumor Size, or Cancer Cell Proliferation in a Mouse Model of Cancer-Induced Bone Pain. J Pain. 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fei G, Raehal K, Liu S, Qu MH, Sun X, Wang GD, Wang XY, Xia Y, Schmid CL, Bohn LM, Wood JD. Lubiprostone reverses the inhibitory action of morphine on intestinal secretion in guinea pig and mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 334:333–340, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harland AA, Bender AM, Griggs NW, Gao C, Anand JP, Pogozheva ID, Traynor JR, Jutkiewicz EM, Mosberg HI. Effects of N-Substitutions on the Tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) Core of Mixed-Efficacy mu-Opioid Receptor (MOR)/delta-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Ligands. J Med Chem. 59:4985–4998, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harland AA, Yeomans L, Griggs NW, Anand JP, Pogozheva ID, Jutkiewicz EM, Traynor JR, Mosberg HI. Further Optimization and Evaluation of Bioavailable, Mixed-Efficacy mu-Opioid Receptor (MOR) Agonists/delta-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Antagonists: Balancing MOR and DOR Affinities. J Med Chem. 58:8952–8969, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horan PJ, Mattia A, Bilsky EJ, Weber S, Davis TP, Yamamura HI, Malatynska E, Appleyard SM, Slaninova J, Misicka A. Antinociceptive profile of biphalin, a dimeric enkephalin analog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 265:1446–1454, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei W, Mullen N, McCarthy S, Brann C, Richard P, Cormier J, Edwards K, Bilsky EJ, Streicher JM. Heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) promotes opioid-induced anti-nociception by an ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) mechanism in mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 292:10414–10428, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Csakai A, Jin J, Zhang F, Yin H. Therapeutic Developments Targeting Toll-like Receptor-4-Mediated Neuroinflammation. ChemMedChem. 11:154–165, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowery JJ, Raymond TJ, Giuvelis D, Bidlack JM, Polt R, Bilsky EJ. In vivo characterization of MMP-2200, a mixed delta/mu opioid agonist, in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 336:767–778, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunzer MM, Yekkirala A, Hebbel RP, Portoghese PS. Naloxone acts as a potent analgesic in transgenic mouse models of sickle cell anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:6061–6065, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mabrouk OS, Falk T, Sherman SJ, Kennedy RT, Polt R. CNS penetration of the opioid glycopeptide MMP-2200: a microdialysis study. Neurosci Lett. 531:99–103, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnus P, Ghavimi B, Coe JW. Access to 7beta-analogs of codeine with mixed mu/delta agonist activity via 6,7-alpha-epoxide opening. BioorgMed Chem Lett. 23:4870–4874, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto K, Narita M, Muramatsu N, Nakayama T, Misawa K, Kitajima M, Tashima K, Devi LA, Suzuki T, Takayama H, Horie S. Orally active opioid mu/delta dual agonist MGM-16, a derivative of the indole alkaloid mitragynine, exhibits potent antiallodynic effect on neuropathic pain in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 348:383–392, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthes HW, Smadja C, Valverde O, Vonesch JL, Foutz AS, Boudinot E, Denavit-Saubie M, Severini C, Negri L, Roques BP, Maldonado R, Kieffer BL. Activity of the delta-opioid receptor is partially reduced, whereas activity of the kappa-receptor is maintained in mice lacking the mu-receptor. J Neurosci. 18:7285–7295, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J Neurosci. 23:5674–5683, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naguib M, Xu JJ, Diaz P, Brown DL, Cogdell D, Bie B, Hu J, Craig S, Hittelman WN. Prevention of paclitaxel-induced neuropathy through activation of the central cannabinoid type 2 receptor system. Anesthesia and analgesia. 114:1104–1120, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Y, Sun X, Jiang L, Hu L, Kong H, Han Y, Qian C, Song C, Qian Y, Liu W. Metformin reduces morphine tolerance by inhibiting microglial-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 13:294, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawar M, Kumar P, Sunkaraneni S, Sirohi S, Walker EA, Yoburn BC. Opioid agonist efficacy predicts the magnitude of tolerance and the regulation of mu-opioid receptors and dynamin-2. Eur J Pharmacol. 563:92–101, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podolsky AT, Sandweiss A, Hu J, Bilsky EJ, Cain JP, Kumirov VK, Lee YS, Hruby VJ, Vardanyan RS, Vanderah TW. Novel fentanyl-based dual mu/delta-opioid agonists for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. Life Sci. 93:1010–1016, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu C, Sora I, Ren K, Uhl G, Dubner R. Enhanced delta-opioid receptor-mediated antinociception in mu-opioid receptor-deficient mice. Eur JPharmacol. 387:163–169, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 314:1195–1201, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutherford JM, Wang J, Xu H, Dersch CM, Partilla JS, Rice KC, Rothman RB. Evidence for a mu-delta opioid receptor complex in CHO cells co-expressing mu and delta opioid peptide receptors. Peptides. 29:1424–1431, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiller PW. Opioid peptide-derived analgesics. AAPS J. 7:E560–565, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiller PW, Fundytus ME, Merovitz L, Weltrowska G, Nguyen TM, Lemieux C, Chung NN, Coderre TJ. The opioid mu agonist/delta antagonist DIPP-NH(2)[Psi] produces a potent analgesic effect, no physical dependence, and less tolerance than morphine in rats. J Med Chem. 42:3520–3526, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmid CL, Kennedy NM, Ross NC, Lovell KM, Yue Z, Morgenweck J, Cameron MD, Bannister TD, Bohn LM. Bias Factor and Therapeutic Window Correlate to Predict Safer Opioid Analgesics. Cell. 171:1165–1175 e1113, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shrivastava P, Cabrera MA, Chastain LG, Boyadjieva NI, Jabbar S, Franklin T, Sarkar DK. Mu-opioid receptor and delta-opioid receptor differentially regulate microglial inflammatory response to control proopiomelanocortin neuronal apoptosis in the hypothalamus: effects of neonatal alcohol. J Neuroinflammation. 14:83, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stefanucci A, Lei W, Hruby VJ, Macedonio G, Luisi G, Carradori S, Streicher JM, Mollica A. Fluorescent-labeled bioconjugates of the opioid peptides biphalin and DPDPE incorporating fluorescein-maleimide linkers. Future Med Chem. 9:859–869, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevenson GW, Luginbuhl A, Dunbar C, LaVigne J, Dutra J, Atherton P, Bell B, Cone K, Giuvelis D, Polt R, Streicher JM, Bilsky EJ. The mixed-action delta/mu opioid agonist MMP-2200 does not produce conditioned place preference but does maintain drug self-administration in rats, and induces in vitro markers of tolerance and dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 132:49–55, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki T, Ikeda H, Tsuji M, Misawa M, Narita M, Tseng LF. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to delta opioid receptors attenuates morphine dependence in mice. Life Sci. 61:PL 165–170, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tremblay EC, Charton G. Anatomical correlates of morphine-withdrawal syndrome: differential participation of structures located within the limbic system and striatum. Neurosci Lett. 23:137–142, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wesolowska A, Young S, Dukat M. MD-354 potentiates the antinociceptive effect of clonidine in the mouse tail-flick but not hot-plate assay. Eur JPharmacol. 495:129–136, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wigerblad G, Huie JR, Yin HZ, Leinders M, Pritchard RA, Koehrn FJ, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ, Huganir RL, Ferguson AR, Weiss JH, Svensson CI, Sorkin LS. Inflammation-induced GluA1 trafficking and membrane insertion of Ca(2+) permeable AMPA receptors in dorsal horn neurons is dependent on spinal tumor necrosis factor, PI3 kinase and protein kinase A. Exp Neurol. 293:144–158, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie JY, De Felice M, Kopruszinski CM, Eyde N, LaVigne J, Remeniuk B, Hernandez P, Yue X, Goshima N, Ossipov M, King T, Streicher JM, Navratilova E, Dodick D, Rosen H, Roberts E, Porreca F. Kappa opioid receptor antagonists: A possible new class of therapeutics for migraine prevention. Cephalalgia. 333102417702120, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Zhang L, Xie M, Li Y, Huang P, Saunders TL, Fox DA, Rosenquist R, Lin F. Role of Complement in a Rat Model of Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan SB, Shi Y, Chen J, Zhou X, Li G, Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, Carlton SM, Ferguson MR, Tan A, Sarna SK, Tang SJ. Gp120 in the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus-associated pain. Ann Neurol. 75:837–850, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Y, King MA, Schuller AG, Nitsche JF, Reidl M, Elde RP, Unterwald E, Pasternak GW, Pintar JE. Retention of supraspinal delta-like analgesia and loss of morphine tolerance in delta opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuron. 24:243–252, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.