Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that mitochondria play a critical role in driving innate immune responses against bacteria and viruses. However, it is unclear if differential reprogramming of mitochondrial function contributes to the fine tuning of pathogen specific immune responses. Here, we found that TLR3 and TLR4 engagement on murine bone marrow derived macrophages was associated with differential remodeling of electron transport chain complex expression. This remodeling was associated with differential accumulation of mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS, which were required to support ligand specific inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production. We also found that the magnitude of TLR3, but not TLR4, responses were modulated by glucose availability. Under conditions of low glucose, TLR3 engagement was associated with increased ETC complex III expression, increased mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS and increased inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production. This amplification was selectively reversed by targeting superoxide production from the outer Q-binding site of the ETC complex III. These results suggest that ligand specific modulation of the ETC may act as a rheostat that fine tunes innate immune responses via mitochondrial ROS production. Modulation of these processes may represent a novel mechanism to modulate the nature as well as the magnitude of antiviral vs. inflammatory immune responses.

Subject terms: Toll-like receptors, Monocytes and macrophages

Introduction

The innate immune system, including tissue macrophages, represent the first line of defence against invading microbial pathogens. Early recognition depends on a variety of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect evolutionarily conserved structures termed pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)1,2. Key players in this process are Toll-like receptors (TLR), which are capable of detecting a range of PAMPs from viruses and bacteria1–5. Among the best characterized are TLR3 and TLR4. TLR3 recognizes double stranded RNA (dsRNA), a common PAMP associated with viral infections6. TLR4 primarily recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the core component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria7. Both TLR3 and TLR4 differentially and dynamically modulate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factory 3 (IRF3) signaling following receptor engagement. While TLR3 activates NF-κB and IRF3 signaling via TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β protein (TRIF), TLR4 signals through both Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) and TRIF1. Differential activation of these signaling pathways plays a critical role in fine tuning pathogen specific antiviral and antibacterial responses1.

Cellular metabolism has emerged as a key regulator of macrophage function. Metabolic reprogramming is required to meet the bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands of the cell and to drive effector functions8–10. Alterations in metabolites and other bioactive metabolic products have also been shown to activate and regulate gene expression, signal transduction and epigenetic profiles9,11–14. Among the best characterized examples of metabolic reprogramming occurs following LPS stimulation9,14–18. Almost immediately after TLR4 engagement, macrophages downregulate oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) activity and dramatically increase glycolysis to support rapid ATP production14,15,17–19. This repurposing of mitochondrial function also increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, which drives inflammatory cytokine production9,15,17. ROS production is driven by the combined effects of increased mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and the oxidation of succinate by complex II of the electron transport chain (ETC)15 suggesting flux through the ETC may play a central role in this process. However, it is still unclear if the dynamic modulation of ETC complexes and increased ROS production contributes to signaling events following engagement of other TLRs and if differential reprogramming of these processes contributes to ligand specific immune responses.

Mitochondria are known to play an important role in innate immune responses against RNA viruses20–23. Recognition of cytosolic viral RNA by retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLR) and their downstream processes have been shown to require the participation of mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS), a mitochondrial outer membrane adaptor protein20,24,25. MAVS acts as a scaffold and recruits effector molecules to the mitochondrial outer membrane leading to the activation of NF-κB and IRF320. More recent studies have shown that mitochondria also contribute to antiviral signaling via MAVS independent mechanisms. Tal et al. found that mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) potentiates RLR signaling. This signaling is regulated by autophagy and clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria26. Alternatively, Yoshizumi et al. found that RLR mediated antiviral responses are dependent on OXPHOS activity. This dependence is regulated by the mitochondrial fusion protein optic atrophy 1 (OPA1)23. These findings suggest that other aspects of mitochondrial function, independent of MAVS mediated scaffolding, may play a central role in facilitating antiviral responses.

While both TLR3 and RLR recognize and respond to virally derived RNAs, they signal through distinct transduction pathways to trigger antiviral immune responses27,28. To date, the role of the mitochondria in driving TLR3 mediated responses in macrophages remains poorly understood. Previous studies have shown that engagement of TLR3 on hepatocytes and dendritic cells (DCs) causes a shift from OXPHOS towards aerobic glycolysis for energy production29–32. In DCs, this shift is driven predominately by the de novo production of type I interferons (IFN) and therefore is required to rapidly meet the increased energy demands of these activated cells30–32. Macrophages stimulated with high concentrations (10 μg/mL) of the synthetic TLR3 agonist polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C) or PIC) have been shown to downregulate Complex I-associated ATP production under standard culture conditions33. However, the functional consequences of this ETC reprogramming has yet to be elucidated.

In the current study, we used murine bone marrow derived macrophages (BMM) to evaluate how reprogramming of mitochondrial function contributes to TLR3 and TLR4 signaling and cytokine production and how glucose availability affected these responses. We found that modulation of flux through the ETC and associated ROS production plays a critical role in cytokine production following TLR engagement. This reprogramming is ligand specific and may have differential effects on the expression of individual cytokines (e.g. accumulation of mitochondrial vs. cytosolic ROS). Further, low glucose conditions resulted in differential reprogramming of mitochondrial function following TLR3 engagement. This reprogramming upregulated complex III expression and associated mitochondrial ROS production, which amplified inflammatory and antiviral signaling and cytokine production. Collectively, these findings suggest that the ETC may act as a selective rheostat of innate immune responses that differentially regulates ligand specific responses based on nutrient availability.

Results

Differential production of pro-inflammatory and antiviral cytokines in PIC- and LPS-stimulated BMM

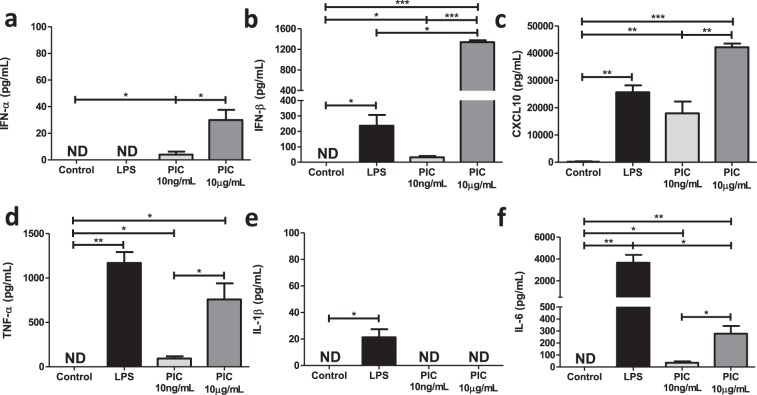

Despite activating the same transcription factors (e.g. NF-κB and IRF3), signaling through TLR3 and TLR4 are associated with distinct inflammatory and antiviral cytokine profiles. To evaluate these differences in our model system, we stimulated BMM with PIC (10 ng/ml and 10 μg/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 18 hours and assessed inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and antiviral (IFN-α, IFN-β and CXCL10) cytokine production in culture supernatants. PIC concentrations were selected to emulate responses in early (low levels of virus) and late stages of infection (high levels of virus), where Lin et al. found that only high (≥10 μg/ml) concentrations of PIC can induce robust inflammatory cytokine production34. The LPS concentration was selected based on its ability to repurpose mitochondrial function to support ROS production15. As previously reported15, LPS induced a strong inflammatory response, produced intermediate levels of IFN-β and CXCL10 and no IFN-α (Fig. 1). Alternatively, stimulation with low concentrations of PIC induced low levels of antiviral and inflammatory production. Increasing the PIC concentration (10 μg/ml) significantly increased both inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

High, but not low, concentrations of Poly(I:C) are associated with pro-inflammatory cytokine production. BMMs were treated with either 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS), 10 ng/mL or 10 μg/mL Poly(I:C) (PIC) for 18 hours. Supernatant was collected and assessed for antiviral (IFN-α, IFN-β, CXCL10) (a–c) and pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) (d–f) cytokine expression. Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

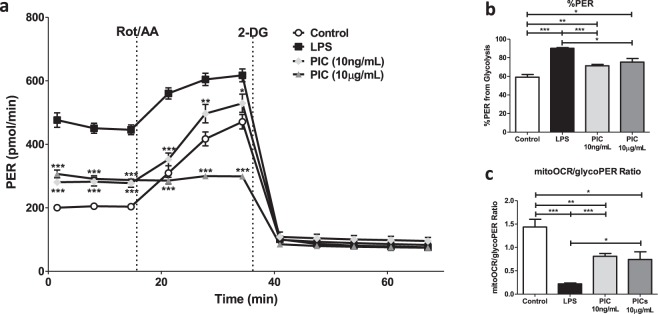

BMM stimulated with low versus high concentrations of PIC differ in their ability to ramp up glycolytic activity under stress

Next, we evaluated the differential effects of LPS and PIC stimulation on cellular metabolism using the Seahorse extracellular efflux analyser. As described above, BMM were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml), low (10 ng/ml) or high (10 μg/ml) concentrations of PIC for 18 hours. Changes in proton efflux rate (PER) at baseline and in response to rotenone + antimycin (ROT/AA) and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) injections were used to evaluate changes in glycolytic parameters. As previously described9,35, LPS stimulation increased PER levels at baseline, increased the %PER derived from glycolysis and decreased the mitoOCR/glycoPER ratio suggesting a strong shift away from OXPHOS activity towards aerobic glycolysis (Fig. 2). Stimulation with both concentrations of PIC also increased PER levels at baseline and the %PER derived from glycolysis, but this increase was significantly lower than that observed following LPS-stimulation (P < 0.001). Further, the reduction in the mitoOCR/glycoPER ratio was less pronounced suggesting that PIC-stimulated cells maintain higher levels of OXPHOS activity (Fig. 2c). Despite similar basal PER levels, low and high concentrations of PIC differentially affected the ability of BMM to ramp up glycolysis following stress with Rot/AA. While cells stimulated with lower concentrations maintained their ability to increase glycolytic activity following exposure to Rot/AA, cells stimulated with higher concentrations were unable to do so, suggesting they may be functioning at their maximum glycolytic capacity (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Macrophages activated using higher concentrations of Poly(I:C) are functioning near their maximum glycolytic capacity. BMMs were seeded onto Seahorse XFp miniplates and treated with 100 ng/mL LPS, 10 ng/mL or 10 μg/mL PIC for 18 hours. Glycolytic activity, indicated by the proton efflux rate (PER) was measured using sequential injections of rotenone plus antimycin A (Rot/AA) and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (a), determining the %PER dependent on glycolysis (b) and the ratio of mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (mitoOCR) to glycolytic PER (c). Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice. The levels of significance shown in (a) represent pairwise comparisons against LPS-treated macrophages (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

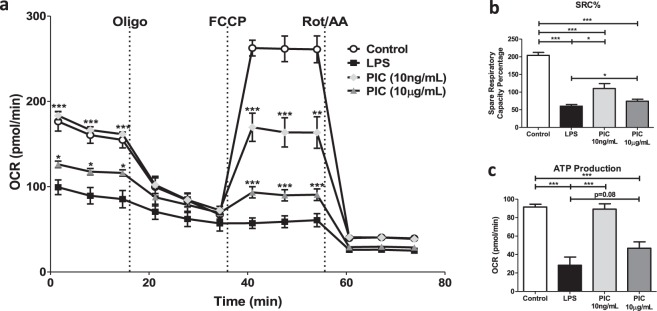

Maintenance of OXPHOS activity is an important feature of PIC but not LPS stimulation

To evaluate specific changes in OXPHOS activity, we used the Cell Mito Stress Test kit from Agilent. Features of OXPHOS activity were calculated based on changes in oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in response to successive injections of oligomycin (Oligo), carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and ROT/AA. Consistent with the literature9,19,36, LPS stimulation dramatically reduced basal respiration, reduced mitochondrial ATP production and reduced the ability of cells to increase oxygen consumption (e.g. spare respiratory capacity [SRC]) following FCCP treatment (Fig. 3). High concentrations of PIC also reduced levels of basal respiration, ATP production and SRC compared to untreated cells but this impairment was less severe than that observed for LPS (basal respiration p < 0.05, SRC p < 0.01, ATP production P = 0.08). Interestingly, low concentrations of PIC did not alter basal respiration or ATP production but significantly reduced SRC suggesting these cells may have a reduced capacity to deal with stress37. Given these differences in glycolysis and oxygen consumption, the remaining experiments were performed using low concentration PIC (10 ng/ml).

Figure 3.

Poly(I:C) stimulation is linked to low sustained levels of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Macrophages were plated onto Seahorse XFp miniplates and subsequently stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS, 10 μg/mL or 10 ng/mL PIC for 18 hours. OXPHOS function was assessed via successive Oligomycin (Oligo), Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), and Rot/AA injections (a), quantifying the spare respiratory capacity percentage (SRC%) (b) and ATP production (c). Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice. The levels of significance shown in (a) is based on pairwise comparisons to LPS-treated macrophages (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

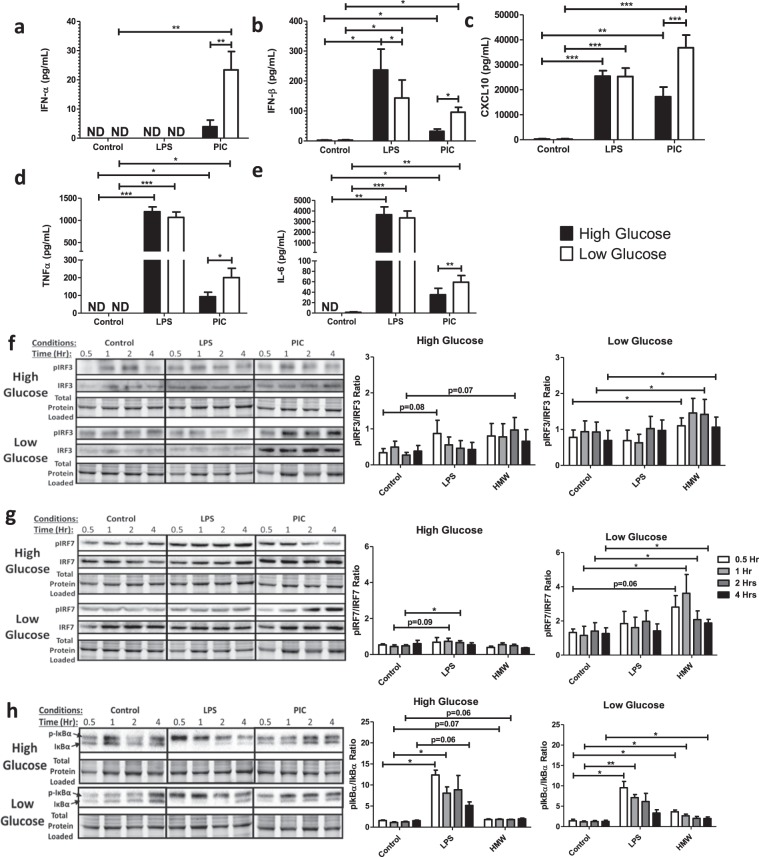

Reduced glucose availability is associated with increased inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production in PIC- but not LPS stimulated BMM

Macrophages are highly plastic cells whose responses are modified by environmental cues including nutrient availability38–41. A recent study in BMM showed that macrophages are less dependent on OXPHOS activity under condition of high glucose (>10 mM) and preferentially use aerobic glycolysis to rapidly produce ATP23. Given the differential ability of BMM to reprogram OXPHOS activity based on glucose availability, we next evaluated how glucose levels affected TLR3 and TLR4 signaling and cytokine production. Most studies have been performed in standard culture conditions, which represent supra-physiological concentrations of glucose. For these studies, BMM were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and PIC (10 ng/ml) in standard (25 mM) and low glucose (0.5 mM) conditions. For the remainder of this paper, standard culture conditions will be referred as high glucose. Glucose levels had no effect on pro-inflammatory cytokine production in LPS stimulated cells (Fig. 4) suggesting that even low glucose levels are sufficient to support TLR4 responses. Conversely, low glucose conditions increased pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6) and IFN-associated cytokine production (IFN-α, IFN-β, CXCL10) following PIC stimulation suggesting that glucose availability may fine tune the magnitude of the TLR3 response. Interestingly, we found that high levels of glucose increase baseline OCR levels, spare respiratory capacity and ATP production in untreated/resting cells. However, following PIC stimulation, high glucose further reduced basal OCR, spare respiratory capacity and ATP production suggesting these conditions may alter TLR3 associated mitochondrial reprogramming (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 4.

Low glucose conditions are associated with increased IRF activation and increased type I IFN production. Macrophages were stimulated with either 100 ng/mL LPS or 10 ng/mL PIC for 18 hours under high glucose (25 mM) or low glucose (0.5 mM) media conditions. Supernatant was collected for assessing antiviral (IFN-α, IFN-β, CXCL10) (a–c) and pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6) cytokine (d,e) expression. Cell lysates were harvested to quantify p-IRF3 and total IRF3 (f), p-IRF7 and total IRF7 (g) and p-Iκbα and total Iκbα (h) expression via immunoblotting. Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). For visualization purposes, the western blot images were cropped, but full-length blots and gel images can be found in Supplemental Fig. S5.

To determine if this amplification was associated with altered signaling, we next evaluated alterations in TLR3 and TLR4 adaptor protein expression and transcription factor phosphorylation following stimulation with LPS and PIC under high and low glucose conditions. While TRIF and TRAF6 expression was not affected by glucose levels (Supplementary Fig. S2), low glucose was associated with a dramatic increase in phosphorylated IRF3 relative to total IRF3 in PIC-stimulated BMM after 0.5, 2 and 4 hours (Fig. 4f). Consistent with its more downstream role in TLR3 signaling42,43, we also found IRF7 phosphorylation was significantly elevated in low glucose conditions during the first four hours of activation (Fig. 4g). Furthermore, we found that levels of phosphorylated IκBα were increased in low glucose conditions in PIC but not LPS-stimulated cells, which may explain the increased TNF-α and IL-6 production following TLR3 engagement (Fig. 4h). Collectively, these results suggest that high glucose may limit mitochondrial reprogramming and associated antiviral and pro-inflammatory signaling and cytokine production in a TLR3 specific manner.

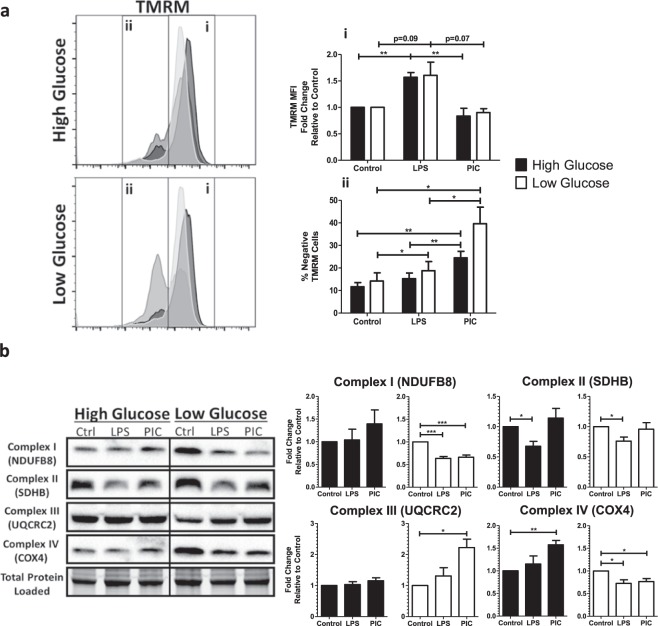

Reduced glucose availability is associated with altered MMP and ETC complex expression following TLR engagement

To better understand how glucose levels affect TLR3 associated alterations in OXPHOS activity, we examined alterations in MMP and ETC complex expression in high and low glucose conditions. MMP was assessed using the fluorescent dye Tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM). As previously described15, LPS stimulation was associated with increased sequestration of TMRM by activated mitochondria (TMRM Mean Fluorescence Intensity [MFI]) in both high and low glucose conditions (Fig. 5a). Alternatively, PIC stimulation did not significantly increase levels of TMRM sequestration in positive cells. Instead, PIC was associated with a significant increase in the number of cells expressing low levels of TMRM, which further increased under low glucose conditions (24% vs. 38%, p = 0.09). To evaluate if altered ETC flux contributes to altered membrane potential, we examined ETC complex expression following LPS and PIC stimulation in high versus low glucose conditions. In high glucose conditions, alterations in expression were highly variable across animals. LPS stimulation moderately decreased complex II (SDHB) expression whereas PIC increased complex IV (COX4) (Fig. 5b). Alterations in ETC complex expression were more pronounced in low glucose conditions. Specifically, both LPS and PIC were associated with decreased expression of complexes I and IV. The only alteration unique to PIC in the low glucose condition was the significant increase in complex III (Fig. 5b). In addition to its role as a proton pump, complex III is a major generator of mtROS44 and may contribute to the amplification of inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production following TLR3 engagement.

Figure 5.

Poly(I:C) activation is linked to altered mitochondrial activity under low glucose conditions. BMMs treated with LPS or PIC for 18 hours under high glucose or low glucose media conditions were characterized for differences in mitochondrial function. Tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM) staining was used to measure, via flow cytometry, mitochondrial membrane potential. (a) Core protein levels of Complexes I-IV of the electron transport chain was quantified via immunoblotting. (b) Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). For visualization purposes, the western blot images were cropped, but full-length blots and gel images can be found in Supplemental Fig. S6.

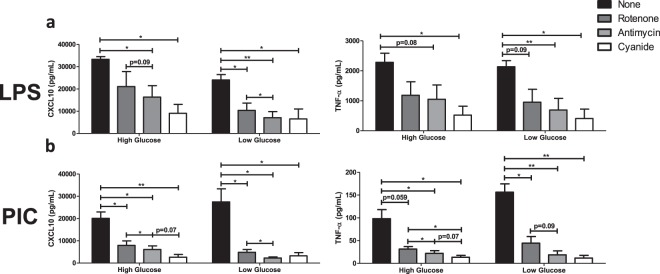

Flux through the ETC chain is required for inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production following TLR engagement

To evaluate the relative contribution of specific ETC complexes on cytokine production, BMM were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and PIC (10 ng/ml) under high and low glucose conditions in the presence or absence of Rotenone (Complex I inhibitor), Antimycin (Complex III inhibitor) and Cyanide (Complex IV inhibitor). Inhibition of Complex III and IV significantly reduced CXCL10 (III: ↓51%; IV: ↓72%) and TNF production (III: ↓54%; IV: ↓77%) following LPS stimulation (Fig. 6a). Under low glucose conditions, inhibition of Complex I also limited LPS-associated cytokine production (CXCL10: ↓57%; TNF: ↓55%). Similarly, inhibition of Complexes I, III and IV significantly reduced inflammatory (TNF) and antiviral cytokine production (IFN-α, IFN-β, CXCL10) following PIC stimulation (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. S3). The magnitude of this inhibition was further amplified under low glucose conditions, particularly for complex III (CXCL10: ↓70% vs. ↓92%; TNF-α: ↓78% vs. ↓89%; IFN-β: ↓79% vs. ↓88%). These results suggest that ETC flux is required for inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production and that under low glucose conditions, alterations in complex III expression may play a central role in the amplification of these responses following TLR3 engagement.

Figure 6.

Targeting ETC activity reduces type I IFN-mediated responses during Poly(I:C) activation. LPS- (a) or PIC- (b) stimulated BMMs were co-treated with a panel of ETC inhibitors (Rotenone, Antimycin, Cyanide) to assess the importance of mitochondrial function for antiviral responses. CXCL10 and TNF-α cytokine secretion was measured after 18 hours in high glucose or low glucose media conditions. Data represents mean ± SEM of three individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

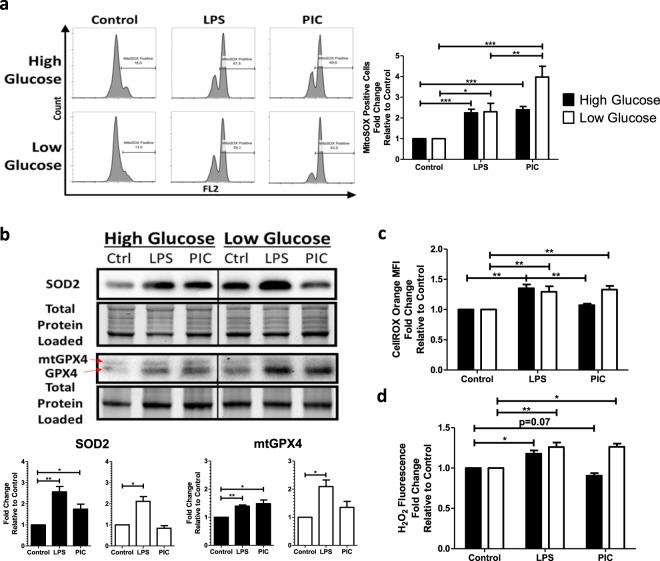

Mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS accumulate in PIC stimulated BMM under low glucose conditions

Given the central role of complexes I and III in driving mitochondrial ROS production, we next quantified mitochondrial superoxide production using the fluorescent probe MitoSOXTM Red. As previously reported45, LPS stimulation was associated with increased mitochondrial superoxide production compared to untreated BMM. This increase was unaffected by glucose availability (Fig. 7a). PIC stimulation was also associated with increased mitochondrial superoxide production (Fig. 7a); however, its production was further increased under low glucose conditions. To determine if this superoxide accumulation was associated with altered antioxidant expression, cellular levels of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase 4 (mtGPX4) were evaluated via western blots. In high glucose conditions, both LPS and PIC stimulated cells significantly increased SOD2 (LPS-FC = 2.56 ± 0.44; PIC-FC = 1.75 ± 0.40) and mtGPX4 expression (LPS-FC = 1.40 ± 0.07; PIC-FC = 1.48 ± 0.22) levels (Fig. 7b). Alternatively, while LPS upregulated both antioxidant proteins under low glucose conditions (SOD2-FC = 2.11 ± 0.40; mtGPX4-FC = 2.09 ± 0.41), levels of SOD2 (FC = 0.83 ± 0.22) and mtGPX4 (FC = 1.35 ± 0.38) were not altered following PIC. This may contribute to the accumulation of superoxide in the mitochondria. To evaluate if these alterations affect the accumulation of cytosolic ROS, we used CellROXTM Orange and quantified H2O2 levels in cell lysates. CellROXTM Orange has a high affinity for hydroxyl radicals, H2O2 and superoxide. BMM treated with LPS exhibit increased levels of cytosolic ROS in both high and low glucose conditions (Fig. 7c). Conversely, increased cytosolic ROS was only observed in low glucose conditions following PIC stimulation (Fig. 7c,d). These results suggest that low glucose conditions are associated with increased mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS accumulation following PIC stimulation, which may contribute to the amplification of the cytokine response.

Figure 7.

Poly(I:C) activation promotes mitochondrial ROS production and accumulation. Macrophages treated either with LPS or PIC for 18 hours under high glucose or low glucose media conditions were examined for differences in redox metabolism. Mitochondrial superoxide production was measured using MitoSOX RedTM (a). Protein levels of antioxidant proteins superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase 4 (mtGPX4) were measured via immunoblotting (b). Cytosolic ROS production was measured using CellROX Orange (c). Hydrogen peroxide levels were quantified using the Cell-based Hydrogen Peroxide Assay kit (d). Data represents mean ± SEM of four individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). For visualization purposes, the western blot images were cropped, but full-length blots and gel images can be found in Supplemental Fig. S7.

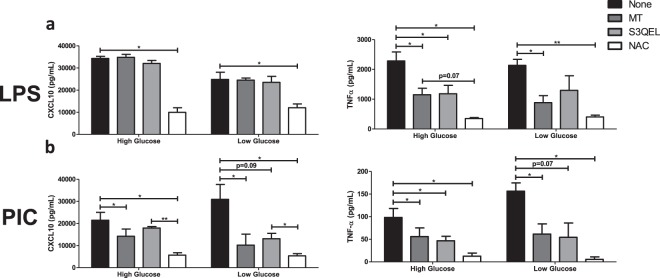

Mitochondrial and cellular ROS play a central role in TLR3 and TLR4 associated cytokine production

To evaluate if ROS contributes to cytokine production following TLR3 and TLR4 engagement, cells were stimulated with either LPS (100 ng/ml) or PIC (10 ng/ml) under high and low glucose conditions in the presence or absence of antioxidants (MitoTEMPO, N-acetylcysteine) or an inhibitor of superoxide production (S3QEL). MitoTEMPO (MT) is a mitochondria-specific antioxidant that selectively scavenges mitochondrial superoxide. Alternatively, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) boosts glutathione synthesis reducing total overall cellular ROS production. S3QEL selectively inhibits superoxide production from the outer Q-binding site of the ETC complex III without altering OXPHOS. Inhibition of mitochondrial ROS had differential effects on cytokine production following LPS stimulation (Fig. 8a; Supplementary Fig. S4). Whereas TNF-α (MT: ↓50%; S3QEL: ↓48%) and IFN-β levels (MT: ↓60%; S3QEL: ↓61%) were decreased following MT and S3QEL production, CXCL10 levels were unaffected. CXCL10 production was only reduced following NAC treatment (CXCL10: ↓71%) suggesting cytosolic ROS may play a more important role in its production following LPS stimulation. Alternatively, inhibition of mitochondrial ROS significantly reduced TNF-α, CXCL10, IFN-α and IFN-β production in PIC-activated macrophages (Fig. 8b; Supplementary Fig. S4). The magnitude of S3QEL inhibition was further amplified under low glucose conditions (TNF-α: ↓54% vs. ↓66%; CXCL10: not significant vs. ↓66%, IFN-β: ↓61% vs. ↓73%) suggesting complex III plays an important role in the amplification of the TLR3 responses. Similar to LPS, NAC treatment had the most pronounced effects on cytokine production in both and high low glucose conditions suggesting that both mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS contribute to TLR3 mediate cytokine production.

Figure 8.

Type I IFN production can be inhibited by altering mtROS generation during Poly(I:C) activation. LPS (a) or PIC (b) stimulated BMMs were co-treated with a panel of mtROS (MT, S3QEL, NAC) modulators to assess the importance of mitochondrial function for antiviral responses. CXCL10 and TNF-α cytokine secretion was measured after 18 hours in high glucose or low glucose media conditions. Data represents mean ± SEM of three individual mice (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that mitochondria play a critical role in driving innate immune responses against bacteria and viruses15,16,20–23,33. However, it is unclear if specific features of mitochondrial reprogramming contribute to pathogen specific immune responses or how nutrient availability may affect these processes. In the current study, we found that TLR3 and TLR4 engagement uniquely remodeled ETC complex expression, resulting in differential accumulation of mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS. This differential ROS production is required to support ligand specific inflammatory and antiviral cytokine profiles. We also found that the magnitude of TLR3 but not TLR4 responses were modulated by glucose availability. Under conditions of low glucose, TLR3 engagement was associated with increased ETC complex III expression, increased mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS and increased inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production. This increased cytokine production was selectively reversed by targeting superoxide production from the outer Q-binding site of the ETC complex III. Collectively, these findings suggest that the ETC may act as a selective rheostat of macrophage function that regulates not only the nature (antibacterial vs. antiviral) but the magnitude of the response, which may depend on nutrient availability.

It is widely accepted that inflammatory macrophages undergo metabolic reprogramming to support cytokine production and effector functions. In LPS-stimulated cells, reprogramming is associated with a near complete inhibition of OXPHOS and an increased reliance on aerobic glycolysis to support rapid energy production9,15,17,36,46. This switch is driven by altered flux through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA), which repurposes mitochondrial function to support superoxide production and drive intracellular anti-bacterial responses15,17. While it was initially assumed all “inflammatory” stimuli induce similar responses, increasing evidence suggests this may not be the case22,23,47. In the current study, we found that PIC stimulation inhibited OXPHOS activity in a dose dependant manner. However, even at its highest concentrations (10 μg/ml), PIC did not completely inhibit OXPHOS activity and some level of cellular respiration was maintained. Consistent with these findings, Yoshizumi et al. found that RLR-mediated responses in macrophages are dependent on OXPHOS both in vitro and in vivo. In BMM, disruption of cellular respiration severely impaired RLR induced interferon and proinflammatory cytokine production23. In mice, inhibition of OXPHOS was found to increase susceptibility to viral infection and induce significant inflammation in the lung23. Wu et al. found that TLR9 engagement and type I IFN production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells was associated with increased OXPHOS activity. This increase was fueled by fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and was required for full cellular activation48. In vivo, inhibition of FAO resulted in a diminished capacity to control lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus48. Several IFN-stimulated genes, such as ISG15, have also been linked to the regulation of mitochondrial function during viral infection suggesting a secondary wave of mitochondrial reprogramming may occur following the TLR engagement and the induction of type I IFN responses49. Collectively, these studies suggest that some level of OXPHOS activity may be required to mount functional antiviral immune responses but that these responses may vary by ligand and cell type.

In addition to altered cellular respiration, LPS and PIC stimulation were associated with alterations in MMP. MMP is generated by the proton pumps of the ETC (Complexes I, III and IV) to support mitochondrial ATP production50. Various studies have reported altered MMP following macrophage activation. Mills et al. found that LPS stimulation was associated with increased MMP via reverse electron flow (RET). This RET was required to drive electrons back towards Complex I in order to support mitochondrial ROS production and antimicrobial effector functions15. Koshiba et al., have found MMP is required for MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling. Specifically, they found that inhibition of mitochondrial fusion resulted in a widespread loss of MMP. This loss in MMP correlated with the level of inhibition of RLR-induced antiviral responses22. Unlike LPS, we found that PIC stimulation was associated with decreased MMP in a subset of cells. While it is unclear what exactly these cells represent, Tal et al. reported that when autophagy is inhibited, increased accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria results in increased mitochondrial ROS production, which drives excess RLR signaling26. Further studies are required to determine if this subset of TMRM low cells are the main producers of ROS in our model system.

Recent studies have provided evidence that changes in the ETC, particularly in complex I and II, contribute to the regulation of antibacterial immune responses15,33 however, it is unclear if similar remodeling occurs during antiviral responses. Here, we found that PIC stimulated cells undergo differential remodeling of the ETC, particularly with limited glucose availability. Standard cell culture conditions represent supra-physiological levels of glucose (25 mM vs. 5–7 mM in fasting blood from non-diabetic individuals51) and may alter mitochondrial reprogramming in vitro52. Under low glucose conditions, both LPS and PIC were found to downregulate complex I and IV expression. Interestingly, only PIC stimulation also increased complex III expression. This increased expression was associated with the amplification of the TLR3 cytokine production, which was reversed by the selective inhibition of ROS production by complex III. In support of our results, others have linked complex III to immune activation and function. In T cells, Sena et al. demonstrated that specific deletion of Rieske iron-sulfur protein (RISP), an essential component of Complex III, reduced mtROS production, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) activation, IL-2-mediated T cell activation and antigen-specific expansion in vivo53. Alternatively, ablation of complex III in regulatory T cells has been shown to reduce their inhibitory capacity without altering cell proliferation and survival54. In macrophages, listeria infection has been shown to increase ROS production via complex III, which drives NF-kappa-B essential modulator (NEMO) dimerization, increasing inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase (IKK) activation, NF-κB signaling and cytokine production47 Our study is among the first to identify associations between complex III mediated ROS production and TLR3 antiviral immune responses.

While ROS are generally considered toxic and damaging, increasing evidence suggests they also influence cellular signaling55,56. Superoxide and its more stable derivative hydrogen peroxide have been shown to regulate a variety of biological responses such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration55. In the current study, we found that both mitochondrial superoxide and cytosolic ROS contribute to inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production following TLR engagement and that differential accumulation of ROS across these compartments may contribute to pathogen specific responses. Furthermore, under low glucose conditions, we found PIC but not LPS was associated with increased mitochondrial superoxide and cytosolic ROS production, which consequentially amplified cytokine production in these cells. These results suggest that the dynamic regulation of ROS production, likely through the modulation of complex III, may act as a rheostat that regulates the magnitude of antiviral immune responses. Consistent with these findings, Agod et al. found that mitochondrial superoxide drives increased MAVS protein expression in plasmacytoid DCs, increasing Akt and IRF3 activation and subsequent type I IFN production57. Wang et al. showed shRNA knockout of SOD2 in cell lines increased viral replication and reduced antiviral responses58, likely a result of decreased mitochondrial H2O2 production, a known redox-sensitive activator of NF-κB and IRF signalling47,59–61. While we believe that mitochondrial superoxide and associated hydrogen peroxide production are the main drivers of cytokine production in our system, we cannot exclude the possibility that alternative cytosolic sources of ROS may also contribute. NADPH oxidase (NOX)-generated ROS during respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections can activate both NF-κB and IRF signalling60,61. Similarly, Yang et al. reported that high concentrations of PIC increase NOX2 activity and ROS production in BMMs, which was required for signal transduction and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)-mediated signalling62. A similar phenomenon was observed by To et al. using TLR7 ligands63. Further studies are required to determine the specific contribution of mitochondrial vs. cytosolic derived ROS in driving these processes and the distinct roles of superoxide vs. hydrogen peroxide on signaling and effector function.

Taken together, our results suggest that dynamic remodeling of the ETC complex expression represents a mechanism by which macrophages modulate cytokine production following TLR engagement. We found that this remodeling was associated with differential accumulation of mitochondrial vs. cytosolic ROS, which may drive ligand specific cytokine profiles. We hypothesize that this differential accumulation may be driven by dependence on complex I (LPS) versus complex III (PIC) for ROS production. Specifically, that LPS associated ROS production depend on RET whereas PIC depends on the maintenance of low levels of OXPHOS activity. Interestingly, we also found that TLR3 but not TLR4 associated mitochondrial reprogramming was dependent on glucose availability in the microenvironment. Supra-physiological levels of glucose have been shown to decrease a cell’s dependence on mitochondria for energy production52,64. Similarly, our results suggest high glucose conditions may also alter mitochondrial reprogramming associated with TLR3 engagement. Accordingly, it is important to develop a detailed understanding of these processes in a variety of bacterial and viral infections to identify new therapeutic approaches to help boost specific and functional effector functions.

Methods

Reagents

A list of all reagents, chemicals or kits used in this study can be found in Table S1. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and high molecular weight Poly(I:C) (PIC) were purchased from InvivoGen. MitoTEMPO (MT), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), antimycin A (AA), rotenone (ROT), potassium cyanide, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), oligomycin (OM) and carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich while S3QEL-2 was purchased from Cedarlane. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and CXCL10 ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems. The IFN-α/IFN-β 2-Plex Mouse ProcartaPlexTM Luminex Panel kit used was from Invitrogen. Tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester (TMRM), MitoSox Red and CellROX Orange probes were from ThermoFisher. Antibodies against Complex II (SDHB) was from Abcam while antibodies recognizing SOD2 was purchased from Cell Signalling Technology. Antibodies targeting IRF3, pIRF3 (Ser385), IRF7, pIRF7 (Ser477), GPX4, Iκbα, Complexes I (NDUFB8), III (UQCRC2) and IV (COX4) were purchased from ThermoFisher.

BMM culturing and stimulation

Total bone marrow cells were collected from the tibias and femurs of 6–13-week-old C57BL/6 mice, cryopreserved in a 90% FBS/10% DMSO solution, and frozen until use. All animal procedures were approved by the Carleton University Animal Care Committee and were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Canadian Council for Animal Care. Cells were cultured for ten days in DMEM media with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 15% L929 fibroblast cell-conditioned medium on a 100 mm Petri dish as previously described65. On day 10, differentiated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were detached, counted and plated into tissue-culture treated plates at 1 × 106 cells/mL. BMMs were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS, 10 ng/mL or 10 μg/mL PIC under high (DMEM medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose) or low glucose conditions (DMEM medium supplemented with 0.5 mM glucose). The relative contribution of the ETC and ROS production on BMM inflammatory and antiviral cytokine production were assessed by co-treating stimulated cells with 1 μM ROT, 5 μM AA, 5 mM cyanide, 500 μM MT, 5 mM NAC, or 5 μM S3QEL-2.

Cytokine quantification

After the 18-hour stimulation, cytokine production was assessed in culture supernatants. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and CXCL10 levels were assessed by ELISAs according to the manufacture's instructions (R&D Systems). IFN-α and IFN-β levels were measured using IFN-α/IFN-β 2-Plex Mouse ProcartaPlexTM Luminex Panel (Invitrogen).

Western blot analysis

Untreated and stimulated BMMs (1 × 106 cells) were lysed directly in the cell culture vessel using Pierce RIPA buffer (ThermoFisher) supplemented with HALTTM Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor (ThermoFisher). Total protein was quantified using the DC assay (Bio-Rad) and resolved on a TGXTM FastCastTM Acrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). Gels were imaged directly using the Stain-Free application of a ChemiDoc XR (Bio-Rad) prior to transferring onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked overnight in 5% non-fat dry milk (w/v), washed and incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibody. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and ClarityTM Western ECL Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad) were used to visualize specified protein bands. Protein densitometry was analyzed according to previously described methodology66. In brief, band intensity of target proteins was normalized relative to the total protein levels in each respective lane using the Bio-Rad Stain-Free application. Expression of most target proteins were normalized relative to the control sample and presented as a fold change value. Alterations in phosphorylated protein expression were calculated as the increase in phosphorylation as proportion of the total protein. Levels were then compared between the control vs. the treated groups (LPS and PIC) under low and high glucose conditions.

Assessment of mitochondrial function by flow cytometry

BMMs were plated on 100 mm Petri dishes and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS or 10 ng/mL and 10 μg/mL PIC for 18 hours. Cells were then washed and stained with fluorescent probes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (30 mins treatment at 37 °C in select solutions). Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using 10 nM TMRM. Mitochondrial and Cellular ROS were monitored using 2.5 μM MitoSOX Red in PBS and 5 μM CellROX Orange in both high and low glucose conditions, respectively. Cellular levels of fluorescence were quantified using an Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (ThermoFisher) and the results were analyzed using FlowJo Software. Results are reported as the percentage of positive cells and as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), the latter being used to describe the level of expression on a population of positive cells.

Quantification of cellular hydrogen peroxide production

BMMs were plated onto 96-well black plates at 50,000 cells/well and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS or 10 ng/mL PIC under high or low glucose conditions for 1 hour. Cells were then washed before using the Cell-based Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit (Abcam) to measure H2O2 production. Cells were incubated with the AbGreen H2O2 indicator for 30 minutes before monitoring the relative difference in fluorescence using a fluorescence microplate reader (490 nm Ex/520 nm Em).

Metabolic extracellular flux analysis

BMMs were plated onto Seahorse XFp cell culture miniplates at 50,000 cells/well (Seahorse Bioscience) and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS or 10 ng/mL and 10 μg/mL PIC for 18 hours. Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) were evaluated using a XFp Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Baseline ECAR and changes in glycolytic rate were assessed using the Seahorse XFp Glycolytic Rate Assay Kit (Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Basal respiration, ATP production-coupled respiration, maximal and reserve capacities and non-mitochondrial respiration were assessed using the Seahorse XFp Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent).

Statistical analyses

Data used in this study was analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. Values shown represent the mean ± SEM of biological replicates, where the number of replicates are reported in the figure legends. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Funding provided by a research development grant provided by the Carleton University Research Office and NSERC.

Author contributions

A.J., A.E. and A.A. isolated the bone marrow progenitor cells from mice. D.A., A.K., A.G. and E.C. designed the experiments. D.A. conducted the experiments. D.A., D.R., A.K., A.G. and E.C. analyzed the data and interpreted all the results. D.A., D.R., A.J., A.E., A.A., A.K., A.G. and E.C. all contributed to the writing and revising of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55295-4.

References

- 1.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–825. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heil F, et al. Species-Specific Recognition of Single-Stranded RNA via Toll-like Receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemmi H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund JM, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-[kappa]B by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow JC, Young DW, Golenbock DT, Christ WJ, Gusovsky F. Toll-like Receptor-4 Mediates Lipopolysaccharide-induced Signal Transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Infantino V, Iacobazzi V, Palmieri F, Menga A. ATP-citrate lyase is essential for macrophage inflammatory response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;440:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tannahill GM, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Errea A, et al. Lactate Inhibits the Pro-Inflammatory Response and Metabolic Reprogramming in Murine Macrophages in a GPR81-Independent Manner. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kesarwani P, Murali AK, Al-Khami AA, Mehrotra S. Redox regulation of T-cell function: from molecular mechanisms to significance in human health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;18:1497–1534. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, et al. Negative regulation of Hif1a expression and TH17 differentiation by the hypoxia-regulated microRNA miR-210. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:393–401. doi: 10.1038/ni.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirai T, et al. The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:337–354. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palsson-McDermott EM, et al. Pyruvate Kinase M2 Regulates Hif-1α Activity and IL-1β Induction and Is a Critical Determinant of the Warburg Effect in LPS-Activated Macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21:65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills EL, et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase Supports Metabolic Repurposing of Mitochondria to Drive Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell. 2016;167:457–470.e413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly B, Tannahill GM, Murphy MP, O’Neill LAJ. Metformin Inhibits the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species from NADH:Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase to Limit Induction of Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Boosts Interleukin-10 (IL-10) in Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated Macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20348–20359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AK, et al. Network Integration of Parallel Metabolic and Transcriptional Data Reveals Metabolic Modules that Regulate Macrophage Polarization. Immunity. 2015;42:419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampropoulou V, et al. Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase with Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2016;24:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodríguez-Prados J, et al. Substrate Fate in Activated Macrophages: A Comparison between Innate, Classic, and Alternative Activation. J. Immunol. 2010;185:605–614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea C-K, Chen ZJ. Identification and Characterization of MAVS, a Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein that Activates NF-κB and IRF3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castanier C, Garcin D, Vazquez A, Arnoult D. Mitochondrial dynamics regulate the RIG‐I‐like receptor antiviral pathway. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:133. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koshiba T. Mitochondrial-mediated antiviral immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshizumi T, et al. RLR-mediated antiviral innate immunity requires oxidative phosphorylation activity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5379. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05808-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai T, et al. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu L-G, et al. VISA Is an Adapter Protein Required for Virus-Triggered IFN-β Signaling. Mol Cell. 2005;19:727–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tal MC, et al. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen species-dependent amplification of RLR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807694106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai T, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meylan E, Tschopp J. Toll-Like Receptors and RNA Helicases: Two Parallel Ways to Trigger Antiviral Responses. Mol Cell. 2006;22:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Djafarzadeh S, Vuda M, Takala J, Ochs M, Jakob SM. Toll-like receptor-3-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cultured human hepatocytes. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantel A, et al. Direct Type I IFN but Not MDA5/TLR3 Activation of Dendritic Cells Is Required for Maturation and Metabolic Shift to Glycolysis after Poly IC Stimulation. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everts B, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKK[epsiv] supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu W, et al. Differential outcome of TRIF-mediated signaling in TLR4 and TLR3 induced DC maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510760112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garaude J, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory-chain adaptations in macrophages contribute to antibacterial host defense. Nature immunology. 2016;17:1037–1045. doi: 10.1038/ni.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin B, Dutta B, Fraser IDC. Systematic Investigation of Multi-TLR Sensing Identifies Regulators of Sustained Gene Activation in Macrophages. Cell Syst. 2017;5:25–37.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krawczyk CM, et al. Toll-like receptor–induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van den Bossche J, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016;17:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sriskanthadevan Shrivani, Jeyaraju Danny V., Chung Timothy E., Prabha Swayam, Xu Wei, Skrtic Marko, Jhas Bozhena, Hurren Rose, Gronda Marcela, Wang Xiaoming, Jitkova Yulia, Sukhai Mahadeo A., Lin Feng-Hsu, Maclean Neil, Laister Rob, Goard Carolyn A., Mullen Peter J., Xie Stephanie, Penn Linda Z., Rogers Ian M., Dick John E., Minden Mark D., Schimmer Aaron D. AML cells have low spare reserve capacity in their respiratory chain that renders them susceptible to oxidative metabolic stress. Blood. 2015;125(13):2120–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-594408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neill LAJ, Pearce EJ. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei J, Raynor J, Nguyen T-LM, Chi H. Nutrient and Metabolic Sensing in T Cell Responses. Front Immunol. 2017;8:247. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langston PK, Shibata M, Horng T. Metabolism Supports Macrophage Activation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:61. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covarrubias AJ, Aksoylar HI, Horng T. Control of macrophage metabolism and activation by mTOR and Akt signaling. Semin Immunol. 2015;27:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Honda K, et al. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Type I Inteferon Gene Induction by the Interferon Regulatory Factor Family of Transcription Factors. Immunity. 2006;25:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, et al. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as novel therapy for inflammatory diseases and cancers. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.West AP, et al. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472:476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan Z, et al. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1 Participates in Macrophage Polarization via Regulating Glucose Metabolism. J Immunol. 2015;194:6082. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herb M, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species enable proinflammatory signaling through disulfide linkage of NEMO. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaar5926. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aar5926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu D, et al. Type 1 Interferons Induce Changes in Core Metabolism that Are Critical for Immune Function. Immunity. 2016;44:1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baldanta S, et al. ISG15 governs mitochondrial function in macrophages following vaccinia virus infection. Plos Pathog. 2017;13:e1006651. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zorova LD, et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Analytical biochemistry. 2018;552:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Diabetes A. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S62–S67. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKee TJ, Komarova SV. Is it time to reinvent basic cell culture medium? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2017;312:C624–C626. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00336.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sena LA, et al. Mitochondria Are Required for Antigen-Specific T Cell Activation through Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling. Immunity. 2013;38:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinberg SE, et al. Mitochondrial complex III is essential for suppressive function of regulatory T cells. Nature. 2019;565:495–499. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holmström KM, Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:411. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nathan C, Cunningham-Bussel A. Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist’s guide to reactive oxygen species. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13:349. doi: 10.1038/nri3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agod Z, et al. Regulation of type I interferon responses by mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Redox Biol. 2017;13:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W, Jin Y, Zeng N, Ruan Q, Qian F. SOD2 Facilitates the Antiviral Innate Immune Response by Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species. Viral Immunol. 2017;30:582–589. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takada Y, et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Activates NF-κB through Tyrosine Phosphorylation of IκBα and Serine Phosphorylation of p65: Evidence for the Involvement of IκBα Kinase and Syk Protein-Tyrosine Kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24233–24241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Indukuri H, et al. Ikkepsilon regulates viral-induced interferon regulatory factor-3 activation via a redox-sensitive pathway. Virology. 2006;353:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonzalez-Dosal R, et al. HSV Infection Induces Production of ROS, which Potentiate Signaling from Pattern Recognition Receptors: Role for S-glutathionylation of TRAF3 and 6. Plos Pathog. 2011;7:e1002250. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang C-S, et al. TLR3-Triggered Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Inflammatory Responses by Activating Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription-1. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190:6368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.To EE, et al. Endosomal NOX2 oxidase exacerbates virus pathogenicity and is a target for antiviral therapy. Nature Communications. 2017;8:69. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00057-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ackermann T, Tardito S. Cell Culture Medium Formulation and Its Implications in Cancer Metabolism. Trends in Cancer. 2019;5:329–332. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weischenfeldt J, Porse B. Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMM): Isolation and Applications. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008:pdb.prot5080. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor SC, Berkelman T, Yadav G, Hammond M. A Defined Methodology for Reliable Quantification of Western Blot Data. Mol Biotechnol. 2013;55:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s12033-013-9672-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.