Abstract

Two novel drug-conjugates based on a “coumarin linker” have been designed for the synergic release of a therapeutic agent and fluorescent probe for the potential application of theranostics. The drug conjugates; CC-RNS and CI-RNS were designed to be activated by reactive oxygen species or reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS). The fluorescence OFF-ON response was triggered by the peroxynitrite-mediated transformation of a boronic acid pinacol ester to a phenol moiety with simultaneous release of the therapeutic agents (Confirmed by HRMS). The limit of detection for peroxynitrite using CC-RNS and CI-RNS was 0.29 and 37.2 μM, respectively. Both CC-RNS and CI-RNS demonstrated the ability to visualize peroxynitrite production thus demonstrating the effectiveness of these probes for use as tools to monitor peroxynitrite-mediated drug release in cancer cell lines.

Keywords: theranostic, peroxynitrite, coumarin, chemosensor, fluorescence

Introduction

Theranostic systems, are the combination of a diagnostic and therapeutic and represent an emerging area with regard to effective cancer treatment. There have been an increasing number of examples of small-molecule theranostics which have good selectivity and high anti-tumor activity (Aulic et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2015). In this respect, new theranostic probes are required for whole organism fluorescence tumor imaging and image guided surgery (Blau et al., 2018).

Real time monitoring of drug action is a prime concern for target specific cancer treatment. Redox-responsive chemotherapy is gaining attention. In such cases, a chemotherapeutic molecule is commonly attached to a fluorophore via a sacrificial self immolative linker (i.e., disulphide) (Wu et al., 2014; Gangopadhyay et al., 2017). Disulphide linkages are selectively cleaved in cancer cells by biological reducing agents, including glutathione (GSH); owing to high levels in cellular environments (2–10 mM) (Lu, 2013). Other examples of theranostic systems include hypoxia-induced and hydrogen peroxide activatable self-immolative systems (Kumar et al., 2014, 2016).

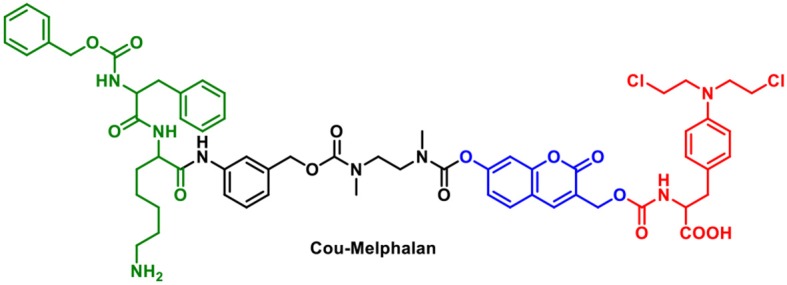

A potential problem for “multi-component” systems is that the chromophore and therapy module could be released independently. One method to circumvent this problem is to use the fluorophore as the “linker” which can be functionalized with both an activating group and a therapeutic. In seminal work, Shabat et al. designed a theranostic prodrug using a self-immolative coumarin linker (Figure 1). The drug-delivery system uses a 7-hydroxycoumarin with a hydroxymethyl substituent. The phenolic alcohol of 7-hydroxycoumarin is linked to an activating group and the hydroxymethyl substituent acts as an attachment point for a drug or targeting group. In this example; Cou-Melphalan incorporates melphalan as a therapeutic with attachments via carbamates. This theranostic was designed to be activated by Cathespin B (Weinstain et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Structure of Cou-Melphalan.

We were interested in utilizing the “coumarin linker” since they are natural products with simple preparative routes. Coumarin has important biological activities including; anti-tumor, anti-HIV and anti-bacterial properties, with multiple coumarin-derived molecules reported to cross the blood brain barrier (Borges et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2015). Various activating mechanisms for theranostics have been used; including activation by reactive oxygen species (ROS), intracellular thiols and enzymes (Chan et al., 2012). The reactive nitrogen species (RNS), peroxynitrite (ONOO−) is of interest due to its orthogonal reactivity with boronate esters and increased reactivity compared to its equivalent reactive oxygen species (ROS), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Sedgwick et al., 2016, 2017; Wu et al., 2018). To this end, we set out to design ONOO− activatable systems (Figure 2) (Yang et al., 2006; Sedgwick et al., 2016, 2018). The probes CI-RNS and CC-RNS were designed with ester linkers, in order to determine whether the same 1–8 self-immolative effect can occur, as in Shabat's system. Since, the use of an ester attachment provides access to probe-based systems using simpler synthetic procedures (Weinstain et al., 2013). The proposed disassembly mechanism is illustrated in Scheme 1.

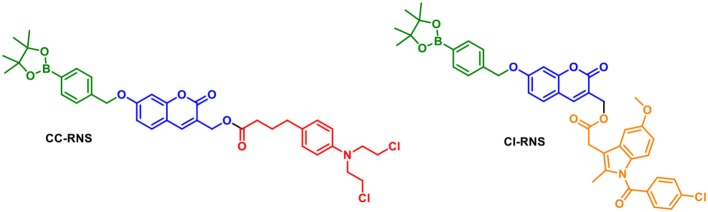

Figure 2.

Structures of CC-RNS and CI-RNS.

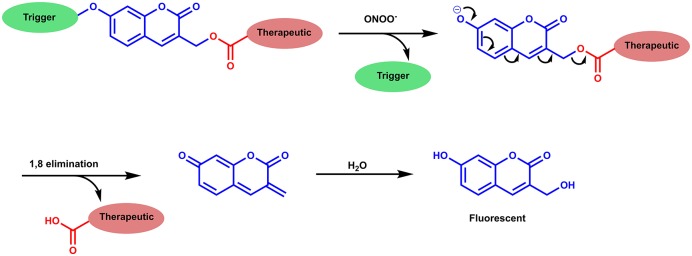

Scheme 1.

Proposed disassembly mechanism of CC-RNS and CI-RNS, adapted from Weinstain et al. (2013).

In vivo ONOO− is generated through the diffusion limited reaction of superoxide (O2•−) and nitric oxide (NO). Both O2•− and NO are non-toxic in vivo due to efficient methods to minimize accumulation (Beckman, 1996). Under proinflammatory conditions, production of O2•− and NO is activated, which inevitably increases the concentration of ONOO− (Pacher et al., 2007). Typically, in vitro studies, the concentration of ONOO− is enhanced by the ONOO− donor SIN1 or stimulation of an inflammatory response using LPS and IFN-γ. The repurposing of the boronate-based probe peroxyresorufin-1 (PR1) Miller et al. (2005) to detect ONOO− in vitro using these methods was reported by Weber et al. (2018). Interestingly, there is no reported data for loss of drug function through reaction with ONOO−. Examples of drug delivery systems which are activated by H2O2 have shown that, on release of the drug, the drug released still has the desired therapeutic response (Kumar et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017).

As therapeutic payloads we chose; chlorambucil and indomethacin, providing distinct mechanisms of action for our theranostic probes. Chlorambucil is a DNA alkylating agent from the nitrogen mustard family. It is used to treat leukemia, Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (Begleiter et al., 1996). Nitrogen mustards are generally unstable (Wang et al., 2010). Off-target reactions with proteins and biological thiols reduce drug potency, requiring higher dosages to produce a substantial therapeutic response. The repurposing and targeting of chlorambucil to enhance treatment scenarios are currently being investigated with successful preliminary studies in breast and pancreatic cancer cell lines (Millard et al., 2013; Kaur et al., 2017).

Indomethacin is primarily a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Indomethacin inhibits the cyclooxygenase enzymes which catalyze the production of prostaglandins; responsible for inflammation and pain (Lucas, 2016). More recently; the effect of indomethacin on the modulation of the inflammatory responses in cancer have been investigated. Indomethacin has been shown to reduce cell migration, invasion, and metastasis in breast and colon cancer cell lines (Ackerstaff et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2013).

Results and Discussion

CI-RNS and CC-RNS were synthesized according to Scheme 2. CI-RNS was prepared over seven steps. CC-RNS was synthesized in six steps. First, coumarin-derivative (4) was obtained using previous literature procedures (Kim et al., 2014; Behara et al., 2017). Coumarin (1) was obtained by reacting 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde with propionic anhydride in the presence of sodium propionate and piperidine. Compound 1 subsequently underwent radical bromination to afford compound 2; which was transformed into compound 3 via acetylation. Compound 3 was deprotected with potassium carbonate in MeOH to yield coumarin (4). 4-(Bromomethyl)phenylboronic acid pinacol ester was added to compound 4 in an alkylation reaction to produce compound 5 in moderate yield. To generate CI-RNS; compound 5 underwent bromination in the presence of PBr3 to produce 6. Thereafter, CI-RNS was obtained by reacting indomethacin in the presence of potassium carbonate, to afford the desired compound in 17% yield. To prepare CC-RNS; compound 5 was reacted with indomethacin using a HATU cross coupling reaction. This reaction gave the desired compound in a 9% yield.

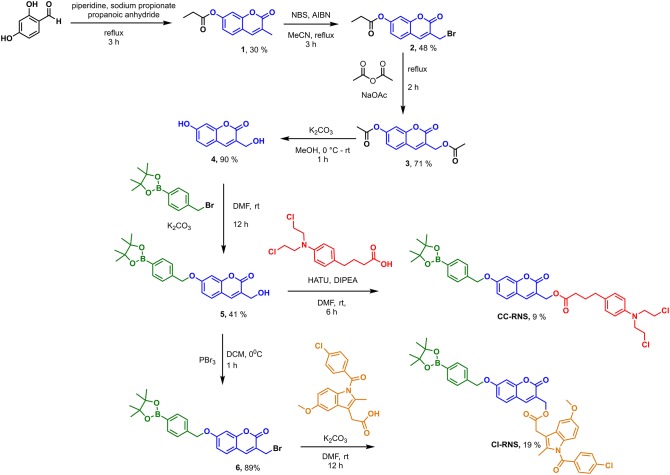

Scheme 2.

Synthesis scheme of CI-RNS and CC-RNS.

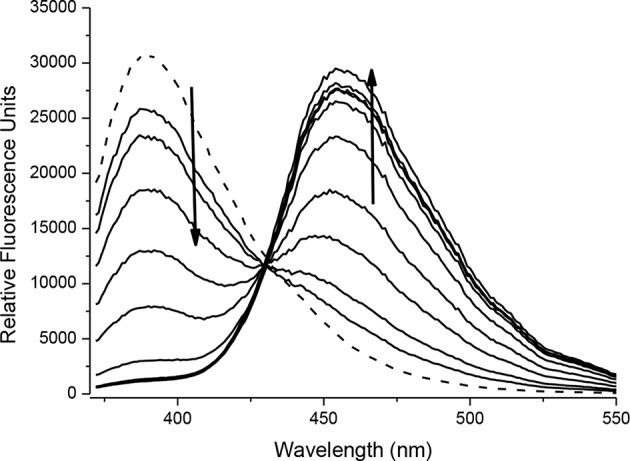

Intermediate compound 5 is an example of a ONOO− activatable molecular probe. Therefore, the reactivity of 5 with ONOO− was investigated. All measurements were recorded in a PBS buffer solution (pH = 7.3) at ambient temperature. The measurements were recorded instantly after ONOO− addition. There is no change in UV-VIS absorption maximum at 315 nm on the addition of ONOO− (20 μM) to the probe 5 (20 μM) (Supplementary Figure 1). The fluorescence spectra of probe 5 (10 μM), shows a ratiometric response. With increasing concentrations of ONOO− (0–20 μM), there is a decrease in peak at 390 nm and emergence of a new peak at 460 nm; characteristic of free coumarin (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 2). The limit of detection for 5 was calculated to be 76.5 nM (Supplementary Figure 3). The formation of free coumarin was also supported by mass spectroscopic studies; finding [M]− = 192.0417 (Supplementary Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence spectra of 5 (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 μM). The data was collected in PBS buffer, pH = 7.3 at 25°C where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. The dotted line represents probe only.

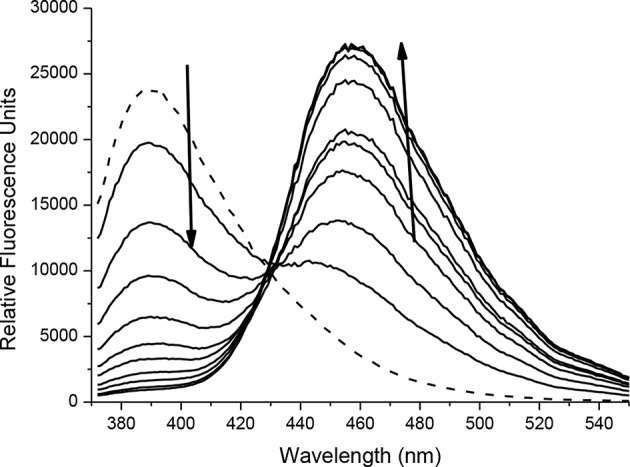

The spectroscopic properties of intermediate 6 were also investigated. 4-bromoumbelliferone shows weak fluorescence at 438 nm, therefore 6 is expected to be non-fluorescent (Thasnim and Bahulayan, 2017). This is due to the less electron-donating effect of the bromomethyl group compared to the methyl alcohol. Addition of ONOO− results in formation of 3-(bromomethyl)-7-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-one; this is confirmed by mass spectroscopic analysis; where exact mass for C10H7BrO3 [M]− = 253.9597 finds [M]− = 253.9569 (Supplementary Figure 5). There is no change in the UV-Vis response with absorption maxima at 340 nm (Supplementary Figure 6). Fluorescence studies carried out in PBS buffer pH = 7.3 at ambient temperature shows that 6 has a fluorescence emission at 390 nm. On addition of ONOO− (0–20 μM) there is a decrease in emission at 390 nm and increase in a new emission peak at 455 nm (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 7). The limit of detection for 6 was calculated to be 54.6 nM (Supplementary Figure 8).

FIGURE 4.

Fluorescence spectra of 6 (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 μM). The data was collected in PBS buffer, pH = 7.3 at 25°C where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. The dotted line represents probe only.

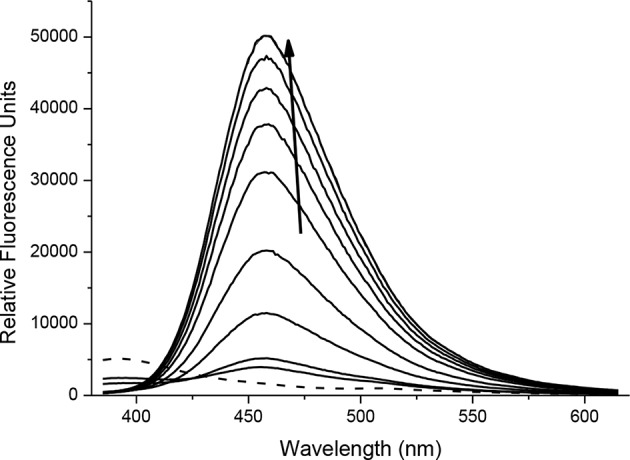

With probes CC-RNS and CI-RNS in hand, spectroscopic evaluations were performed. All measurements were recorded in PBS buffer solution (pH = 7.3) at ambient temperature. The measurements were recorded instantly after ONOO− addition. The UV-VIS spectrum of probe CC-RNS (20 μM) and CI-RNS (20 μM) were recorded with and without ONOO− (50 μM—Supplementary Figures 9, 10). From the UV-VIS spectrum the probes have an initial absorption maximum at 315 nm. On addition of ONOO−, the absorption maximum shifts to 360 nm. The redox regulated response was monitored by subjecting 10 μM of each probe, CC-RNS and CI-RNS, to increasing concentrations of the biological oxidant ONOO−. Figures 5, 6 shows that initially both probes are non-fluorescent. There is a strong increase in emission at 460 nm for both probes; ca. 22- fold for CI-RNS and 33-fold for CC-RNS with increasing concentrations of ONOO− (0–50 μM and 0–30 μM, respectively). The limit of detection (LOD) for CC-RNS is 0.29 μM and 37.2 μM for CI-RNS (Supplementary Figures 11–14).

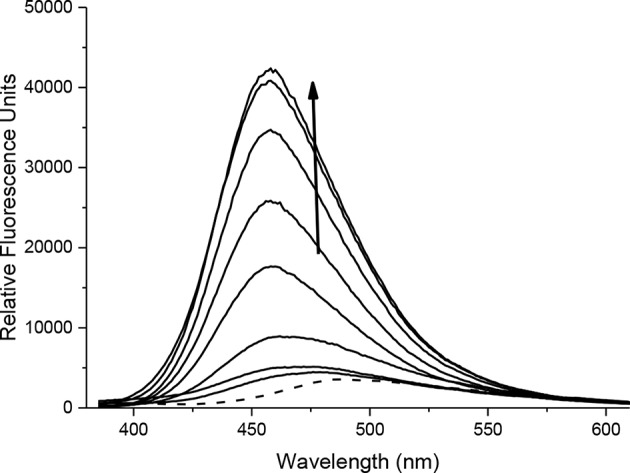

FIGURE 5.

Fluorescence spectra of CC-RNS (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (0–20 μM) in PBS buffer pH = 7.3. The data was collected at 25°C instantly after addition of peroxynitrite, where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. The dotted line represents probe only.

FIGURE 6.

Fluorescence spectra of CI-RNS (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (0, 10, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 μM). The data was collected in PBS buffer, pH = 7.3 at 25°C where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. The dotted line represents probe only.

The process of RNS triggered release of coumarin from CC-RNS and CI-RNS was supported by mass spectrometric evaluation. The experiments determined that [M]− = 192.0438 and [M]+ = 192.0387 for CC-RNS and CI-RNS, respectively (Supplementary Figures 15, 16). This mass corresponds to formation of compound 4; the expected cleavage product of the reaction. The formation of free coumarin demonstrates that these systems do release the drug payload in situ.

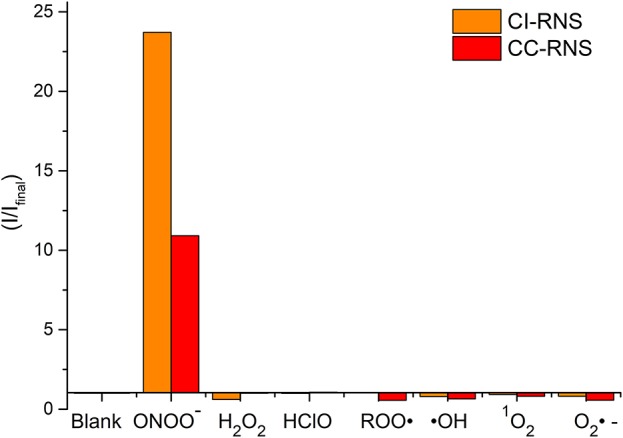

The change in fluorescent properties of potential theranostics CC-RNS, CI-RNS, probes 5 and 6 were investigated in the presence of various biologically relevant ROS; hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hypochlorite (ClO−), superoxide (O2−•), singlet oxygen (1O2), hydroxyl radical (HO•), and peroxyl radical (ROO•). Pleasingly, CC-RNS, CI-RNS, 5 and 6 are highly selective toward ONOO− (Figures 7–9, Supplementary Figures 17–20).

FIGURE 7.

Selectivity data of CC-RNS and CI-RNS (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (20 μM), H2O2 (200 μM), ClO− (200 μM), ROO· (200 μM), OH (200 μM), O2·− (200 μM), and 1O2 (200 μM) in PBS buffer pH = 7.3. The data was collected at 25°C after incubation for 15 min, where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. Fluorescence intensity points were taken at λmax = 460 nm.

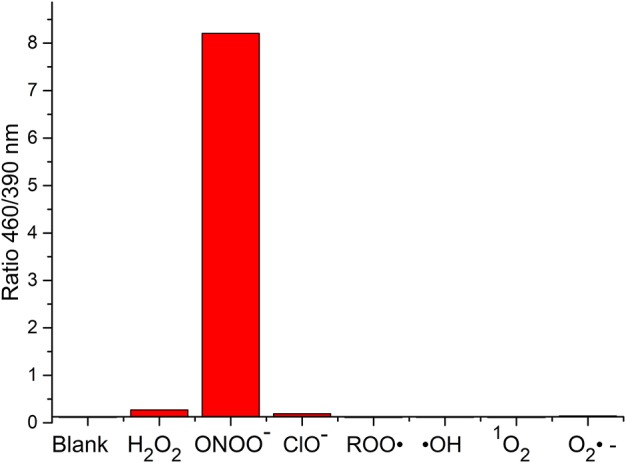

FIGURE 9.

Selectivity data of 6 (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (20 μM), H2O2 (100 μM), ClO− (100 μM), ROO· (100 μM), ·OH (100 μM), O2·− (100 μM), and 1O2 (100 μM) in PBS buffer pH = 7.3. The data was collected at 25°C after incubation for 15 min, where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. Fluorescence intensity points were taken at λmax = 455/390 nm.

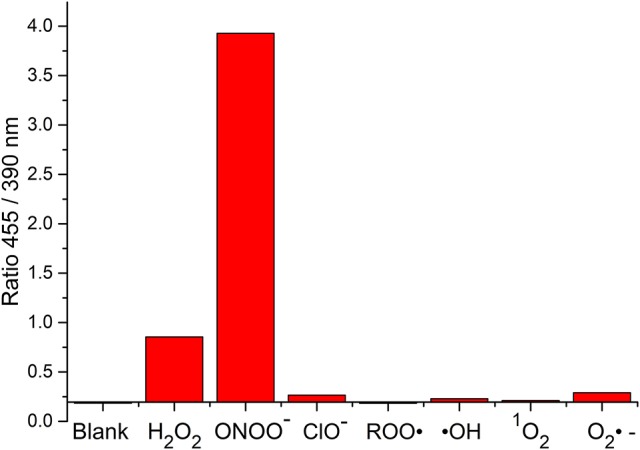

FIGURE 8.

Selectivity data of 5 (10 μM) in the presence of ONOO− (20 μM), H2O2 (100 μM), ClO− (100 μM), ROO· (100 μM), OH (100 μM), O2·− (100 μM), and 1O2 (100 μM) in PBS buffer pH = 7.3. The data was collected at 25°C after incubation for 15 min, where λex = 345 (16 bandwidth) nm. Fluorescence intensity points were taken at λmax = 460/390 nm.

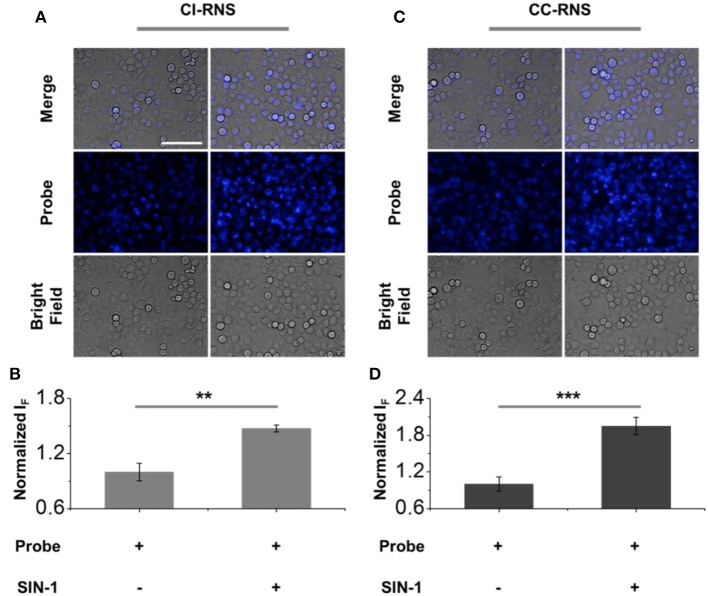

After confirming the selectivity and sensitivity of CC-RNS and CI-RNS for ONOO−, we evaluated the reaction of CC-RNS and CI-RNS with ONOO− in cells. HeLa (cervical cancer) cells were pre-treated with CI-RNS or CC-RNS. Subsequently, SIN-1 (an ONOO− donor) was added to produce intracellular ONOO−. As shown in Figure 10, the probe alone resulted in a weak fluorescence in cells. However, treatment with SIN-1 led to a significant increase in the fluorescence intensity enabling the visualization of ONOO− in living cells. Cytotoxicity studies for both CC-RNS and CI-RNS indicate that the probes are almost non-toxic to Hela cells after incubation with SIN-1 and illumination (ESI- Supplementary Figures 21, 22). Hence, no further imaging studies were undertaken.

FIGURE 10.

Fluorescence imaging and quantification of (A,B) CI-RNS (20 μM) and (C,D) CC-RNS (20 μM) in the presence of SIN-1 (500 μM) of HeLa cells. Excitation channel 360–400 nm, emission channel filtered = 410–480 nm. Scale bar = 100 μm. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Conclusion

In this work, we have developed two novel drug conjugate systems, CC-RNS and CI-RNS. The drug conjugate systems were designed to integrate a Shabat-based “coumarin linker” with an ONOO− trigger. The systems incorporated the therapeutics drug payloads of chlorambucil and indomethacin as esters for potential theranostic application. Pleasingly, for each system in solution, the probes displayed a selective turn-on response toward ONOO−. In addition, in vitro evaluation with HeLa cells demonstrated that the probes were able to successfully visualize endogenous ONOO− production, providing a potential platform to be able to monitor ONOO− mediated drug release in cancer cell lines. We are currently working on the development of longer wavelength “fluorophore linkers” using ester attachments to appropriate therapeutic units that will facilitate the use of such probes in an animal model in order to evaluate their therapeutic value.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

AS originated the idea and developed the synthetic route. JG and MO carried out synthesis. MO performed fluorescence experiments. H-HH carried out cell imaging studies under supervision from X-PH. MO wrote the manuscript with the support of SB and TJ. All authors read and approved the final manuscripts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the EPSRC and the University of Bath for funding. TJ wishes to thank the Royal Society for a Wolfson Research Merit Award. MO, JG, and AS thank the EPSRC for their studentships. X-PH wishes to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21722801), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (15540723800) and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (16QA1401400) for financial support. Characterization facilities were provided through the Material and Chemical Characterization Facility (MC2) at the University of Bath (http://go.bath.ac.uk/mc2). All data supporting this study are provided as Supplementary Information accompanying this paper.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2019.00775/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ackerstaff E., Gimi B., Artemov D., Bhujwalla Z. M. (2007). Anti-inflammatory agent indomethacin reduces invasion and alters metabolism in a human breast cancer cell line. Neoplasia 9, 222–235. 10.1593/neo.06673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulic S., Bolognesi M. L., Legname G. (2013). Small-molecule theranostic probes: a promising future in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 1–19. 10.1155/2013/150952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman J. S. (1996). The physiological and pathological chemistry of nitric oxide, in Nitric Oxide: Principles and Actions, eds Lancaster J. R. Orlando, FL:Academic, 1–82. 10.1016/B978-012435555-2/50002-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter A., Mowat M., Israels L. G., Johnston J. B. (1996). Chlorambucil in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: mechanism of action. Leuk. Lymphoma. 23, 187–201. 10.3109/10428199609054821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behara K. K., Rajesh Y., Venkatesh Y., Pinninti B. R., Mandal M., Singh N. D. P. (2017). Cascade photocaging of diazeniumdiolate: a novel strategy for one and two photon triggered uncaging with real time reporting. Chem. Commun. 53, 9470–9473. 10.1039/C7CC04635A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau R., Epshtein Y., Pisarevsky E., Tiram G., Dangoor S. I., Yeini E., et al. (2018). Image-guided surgery using near-infrared Turn-ON fluorescent nanoprobes for precise detection of tumor margins. Theranostics 8, 3437–3460. 10.7150/thno.23853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F., Roleira F., Milhazes N., Santana L., Uriarte E. (2005). Simple coumarins and analogues in medicinal chemistry: occurrence, synthesis and biological activity. Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 887–916. 10.2174/0929867053507315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J., Dodani S. C., Chang C. J. (2012). Reaction-based small-molecule fluorescent probes for chemoselective bioimaging. Nat. Chem. 4, 973–984. 10.1038/nchem.1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay M., Mengji R., Paul A., Venkatesh Y., Vangala V., Jana A., et al. (2017). Redox-responsive xanthene-coumarin-chlorambucil-based FRET-guided theranostics for “activatable” combination therapy with real-time monitoring. Chem. Commun. 53, 9109–9112. 10.1039/C7CC03241B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. C., Chang C. M., Hsu W. L., Chiu S. J., Tsai Y. T., Chou Y. H., et al. (2013). Indomethacin inhibits cancer cell migration via attenuation of cellular calcium mobilization. Molecules 18, 6584–6596. 10.3390/molecules18066584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J., Tsvetkova Y., Arroub K., Sahnoun S., Kiessling F., Mathur S. (2017). Synthesis, characterization, and relaxation studies of Gd-DO3A conjugate of chlorambucil as a potential theranostic agent. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 89, 269–276. 10.1111/cbdd.12827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. J., Bhuniya S., Lee H., Kim H. M., Cheong C., Maiti S., et al. (2014). An activatable prodrug for the treatment of metastatic tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13888–13894. 10.1021/ja5077684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Han J., Lim H.-J., Ren W. X., Lim J.-Y., Kim J.-H., et al. (2014). Mitochondrial induced and self-monitored intrinsic apoptosis by antitumor theranostic prodrug: in vivo imaging and precise cancer treatment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17836–17843. 10.1021/ja510421q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Kim E. J., Han J., Lee H., Shin W. S., Kim H. M., et al. (2016). Hypoxia-directed and activated theranostic agent: imaging and treatment of solid tumor. Biomaterials 104, 119–128. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Shin W. S., Sunwoo K., Kim W. Y., Koo S., Bhuniya S., et al. (2015). Small conjugate-based theranostic agents: an encouraging approach for cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6670–6683. 10.1039/C5CS00224A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. C. (2013). Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1830, 3143–3153. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S. (2016). The pharmacology of indomethacin. Headache 56, 436–446. 10.1111/head.12769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard M., Gallagher J. D., Olenyuk B. Z., Neamati N. (2013). A selective mitochondrial-targeted chlorambucil with remarkable cytotoxicity in breast and pancreatic cancers. J. Med. Chem. 56, 9170–9179. 10.1021/jm4012438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. W., Albers A. E., Pralle A., Isacoff E. Y., Chang C. J. (2005). Boronate-based fluorescent probe for imaging cellular hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16652–16659. 10.1021/ja054474f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P., Beckman J. S., Liaudet L. (2007). Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 87, 315–424. 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick A. C., Han H.-H., Gardiner J. E., Bull S. D., He X.-P., James T. D. (2018). The development of a novel AND logic-based fluorescence probe for the detection of peroxynitrite and GSH. Chem. Sci. 9, 3672–3676. 10.1039/C8SC00733K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick A. C., Han H. H., Gardiner J. E., Bull S. D., He X. P., James T. D. (2017). Long-wavelength fluorescent boronate probes for the detection and intracellular imaging of peroxynitrite. Chem. Commun. 53, 12822–12825. 10.1039/C7CC07845E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick A. C., Sun X. L., Kim G., Yoon J., Bull S. D., James T. D. (2016). Boronate based fluorescence (ESIPT) probe for peroxynitrite. Chem. Commun. 52, 12350–12350. 10.1039/C6CC06829D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thasnim P., Bahulayan D. (2017). Click-on fluorescent triazolyl coumarin peptidomimetics as inhibitors of human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. New J. Chem. 41, 13483–13489. 10.1039/C7NJ02712E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Q., Begum R. A., Day V. W., Bowman-James K. (2010). Sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen mustards: stability and reactivity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 10, 8786–8793. 10.1039/c2ob26482j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.-K., Cheng J., Liang X.-G., Tan C., Jiang Q., Hu Y.-Z., et al. (2017). A H2O2-responsive theranostic probe for endothelial injury imaging and protection. Theranostics 7, 3803–3813. 10.7150/thno.21068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M., Mackenzie A. B., Bull S. D., James T. D. (2018). Fluorescence based tool to detect endogenous peroxynitrite in M1-polarised murine J774.2 macrophages. Anal. Chem. 90, 10621–10627. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstain R., Segal E., Satchi-Fainaro R., Shabat D. (2013). Real-time monitoring of drug release. Chem. Commun. 46, 553–555. 10.1039/B919329D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. L., Wang Y., Weber M., Liu L. Y., Sedgwick A. C., Bull S. D., et al. (2018). ESIPT-based ratiometric fluorescence probe for the intracellular imaging of peroxynitrite. Chem. Commun. 54, 9953–9956. 10.1039/C8CC04919J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Sun X., Guo Z., Tang J., Shen Y., James T. D., et al. (2014). In vivo and in situ tracking cancer chemotherapy by highly photostable NIR fluorescent theranostic prodrug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 3579–3588. 10.1021/ja412380j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Wang H.-L., Sun Z.-N., Chung N.-W., Shen J.-G. (2006). A highly selective fluorescent probe for the detection and imaging of peroxynitrite in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6004–6015. 10.1021/ja0603756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. F., Xu W., Song W., Ye M., Yang X. W. (2015). Transport of twelve coumarins from angelicae pubescentis radix across a MDCK-pHaMDR cell monolayer-an in vitro model for blood-brain barrier permeability. Molecules 20, 11719–11732. 10.3390/molecules200711719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.