Abstract

Background:

The regulation and maintenance of intracellular pH are critical to diverse metabolic functions of the living cells. Fluorescence time-resolved techniques and instrumentations have advanced rapidly and enabled the imaging of intracellular pH based on the fluorescence lifetimes.

Methods:

The frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and fluorophores displaying appropriate pH-dependent lifetime sensitivities were used to determine the temporal and spatial pH distributions in the cytosol and vesicular compartment lysosomes.

Results:

We found that cytosolic pH levels are different in 3T3 fibroblasts, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and MCF-7 cells when using the pH probe carboxy-SNAFL2. We also tracked the transient cytosolic pH changes in the living CHO cells after treatments with proton pump inhibitors, ion exchanger inhibitors, and weak base and acid. The intracellular lysosomal pH was determined with the acidic lifetime probes DM-NERF dextrans, OG-514 carboxylic acid dextrans, and Lyso-Sensor DND-160. Our results showed that the resting lysosomal pH value obtained from the 3T3 fibroblasts was between 4.5 and 4.9. The increase of lysosomal pH induced by the treatments with proton pump inhibitor and ionophores also were observed in our FLIM measurements.

Conclusions:

Our lifetime-based pH imaging data suggested that FLIM can measure the intracellular pH of the resting cells and follow the pH fluctuations inside the cells after environmental perturbations. To improve the z-axis resolution to the intracellular lifetime-resolved images, we are investigating the implementation of the pseudo-confocal capability to our current FLIM apparatus.

Key terms: fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, pH imaging, cytosolic pH, lysosomes, DM-NERF, Oregon Green 514 carboxylic acid, carboxy-SNAFL2

The appropriate hydrogen ion activities maintained inside and between living cells are critical to diverse cell functions. For example, environmental pH changes can induce specific signaling pathways in fungi, yeasts, and some parasites to activate the expression of certain genes to respond to the environmental stresses (1–4). In some mammalian cells, the morphology and transportation activities of the cellular acidic vesicles are strongly dependent on the pH gradients across the vesicular membranes (5–7). Several studies on multidrug-resistant cells also implicate the correlation between intracellular pH gradients and cellular activity in expelling chemotherapeutic drugs to the endocytic vesicles (8–10). Moreover, neuronal disorders such as seizure and cytotoxic edema are reported to connect to pathologic changes of the pH in glial cells (11,12). Hence, the development of high-resolution imaging tools to follow the cellular and subcellular pH gradients is strongly desirable.

Fluorescence sensing techniques have been widely used to map the intracellular pH. In the past decade, ratiometric fluorescence microscopy became the most popular method to characterize pH regulatory mechanisms in different cellular compartments (13–15). Fluorescence time-resolved techniques recently have advanced rapidly and support a different fluorescence imaging strategy, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), to follow the physiologic changes inside living cells (16–21). FLIM measurements can be performed as time-domain and frequency-domain methods, and both methods can be adapted to confocal and multiphoton microscopies. These extensive capabilities of FLIM provide the appropriate lifetime resolutions to track the fluorescent tags in living cells (22–25) and to characterize intramolecular interactions (22,26–29).

Carboxy- (C-) SNAFL1, C-SNAFL2, fluorescein, and C-fluorescein are fluorescent indicators showing the fluorescence lifetime sensitivity at different pH ranges. They have been used to determine the cytosolic pH distribution in mammalian cells (30–32), the phagosomal pH evolution in macrophages (21), and the pH gradients in cultured microbial biofilms (33). However, very limited numbers of lifetime probes have been shown to be sensitive to low pH environments (34), and only a few reports have described time-resolved pH imaging in acidic cellular compartments. In this study, we present pH images obtained from the cytosol and lysosomes of living cells loaded with neutral and acidic pH lifetime probes, respectively, and attempt to correlate the observed intracellular pH changes with specific cellular physiologic events based on frequency-domain FLIM measurements.

C-SNAFL2, a lifetime-based fluorescent indicator responsive to the neutral pH range, was used to image the cytosolic pH of resting 3T3 fibroblasts, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Different cytosolic pH levels (pH 7.40–7.15) were determined from these cell lines. We also tracked the transient cytosolic pH changes in living CHO cells after different pH perturbation steps. The observed pH response curves obtained from the lifetime-resolved FLIM measurements were comparable to those derived from intensity-based imaging measurements (35–37). In contrast, intracellular lysosomal pH was measured with the fluorescent indicator DND-160 and the dextran conjugations of DM-NERF and OG-514. These pH probes were loaded into living cells by spontaneous pinocytosis. The lysosomal pH values measured from the resting 3T3 fibroblasts were between 4.5 and 4.9. The susceptibility of the lysosomal pH to the proton pump inhibitors and ionophores also was evaluated. The treated cells generally displayed an average increase of 0.5 U of pH in the lysosomes of resting fibroblasts. In general, our FLIM instrumentations produced precision and sensitivity comparable to the traditional fluorometric techniques in imaging intracellular pH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Cultures

Three adherent cell lines were raised for FLIM measurements. 3T3-Swiss albino (CCL-92, ATCC, Manassas, VA) was grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum. CHO-K1 (CCL-61, ATCC) was grown in Ham’s F-12K medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. MCF-7 (HTB-22, ATCC) was grown in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium containing Earle’s balanced salt saline, nonessential amino acids, bovine insulin, and 10% fetal bovine serum. All media, sera, and supplements for cell cultures were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MD). The cells were routinely cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and plated onto glass-bottom microwell dishes (Mattek Corp., Ashland, MA) 2 to 3 days before FLIM measurements.

Cell Labeling

Fluorescent pH indicators were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR.) without further purification. The stock solution of C-SNAFL2 diacetate in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was prepared at the concentration of 12 mM and kept desiccated at −20°C. The final working concentration of C-SNAFL2 diacetate was 15 μM in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cells were rinsed with HBSS and then incubated with C-SNAFL2 diacetate at 37°C for 20 to 40 min. C-SNAFL2 diacetate diffused across the cell membranes spontaneously, hydrolyzed into C-SNAFL2 by intracellular esterase, and localized in the cytosol. The extracellular probes then were rinsed off with HBSS. The loaded C-SNFAL2 stayed inside the cells for at least 2 h when the acquisitions were performed at the room temperature. Raising the incubation temperature to 37°C increased cell activities and hastened the release of C-SNAFL2 to the extracellular medium. Therefore, the intensified background degraded the resolution of the lifetime images.

The lysosomes were stained with the fluorescent probes by spontaneous pinocytosis of the fibroblasts. Dextran-conjugated DM-NERF (dx-DMNERF) and OG-514 carboxylic acid (dx-OG514) of 70 kD were dissolved at the concentration of 1 mg/ml in HBSS and then incubated with the cells at 37°C for 2 h. Afterward the cells were gently rinsed with clean HBSS and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The second incubation step exhausted the fluorophores kept inside the recycling endosomes and avoided the background increase during the measurements. Lyso-Sensor Yellow/Blue DND-160 (DND-160) is a membrane-permeable probe and can rapidly highlight the acidic compartments within 5 min. Nevertheless, DND-160 also leaked out the cells in a short time and quickly increased the image background. To obtain better lysosomal images, we also used the longer incubation procedures originally used for the dextran-conjugated probes to load DND-160 into cells.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy

The principles of our homodyne FLIM were described in detail elsewhere (20,38). In general, the object being imaged is exposed to a laser excitation, with its intensity harmonically modulated at an angular frequency of ω = 2πf:

| (1) |

where mE is the degree of modulation. The periodic excitation causes the fluorescent object to emit a delayed light, F(t), with the same modulation frequency, ω. Relative to the excitation light, the modulated emission displays a spatially dependent phase lag, ϕF(r), and a decreased modulation mF(r):

| (2) |

The observed phase lag, ϕF(r), and demodulation ratio, m = mF(r)/mE(r), depend on all lifetime components of the emission. The emission is projected farther onto a image intensifier, and the electronic gain, G(t), of the image intensifier is modulated at a radiofrequency of ω + Δω:

| (3) |

In equation 3, ϕDr and mD represent the phase lag and demodulation of the image intensifier, respectively. Because the time constant of the phosphor screen is determined by the millisecond lifetime of phosphorous, all high-frequency components of the emission are time averaged, and the amplified image is intensity-modulated at a low frequency, Δω:

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

In the homodyne FLIM method, the gain of the image intensifier is modulated at the same frequency as the excitation light, i.e., Δω = 0, so a constant image is observed on the phosphor screen:

| (6) |

Intensity I(r) depends on the demodulations of the detector and emission and on the phase shift between fluorescence and detector. During one acquisition cycle, a stack of intensity images is collected at several ϕD values between 0 and 2π. Because these phase-sensitive images contain information on phase shift and demodulation at each pixel, the lifetime images can be constructed by extracting the ϕF(r) and mF(r) values through the Fourier transform and the linear least-squares fit.

The optical and electrical schematics of the FLIM instrumentation is shown in Figure 1. The excitation source was a mode-locked argon ion laser (output, 514 nm), with the intensity modulated at 75.47 MHz and its harmonics at 75.47 MHz. The laser beam was attenuated further by a neutral density filter and directed into a fluorescence microscope Axiovert 135TV (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) by quartz optical fibers. A mechanical shutter (UniBlitz D122, Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY) was placed in front of the optical fibers to synchronize the illumination and acquisition. The epi-illumination was accomplished by a dichroic beam splitter (515DRLP, Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT). The emission light was collected by a waterimmersion objective (C-Apochromat, 40× objective, 1.2 W; Carl Zeiss) and an interference filter centered at 635 nm (model 635DF55, Omega Optical) and further focused onto an image intensifier unit (C5825, Hamamatsu Corp., Bridgewater, NJ). The images were finally digitized on a slow-scan, fast frame-shift charged coupled device (PXL37, Photometrics, Tucson, AR). The gain of the image intensifier was modulated at different frequencies depending on the output of the PTS300 synthesizer (Programmed Test Sources, Littleton, MA). The frequency was set at 75.47 MHz for imaging dx-DMNERF and dx-OG514 and at 150.936 MHz for C-SNAFL2. The other function of the PTS synthesizer is to digitally shift the phase angle of the detector within an acquisition cycle of 360 degrees. The phase-sensitive images recorded in one cycle were processed in a Unix workstation. The imaging setup for DND-160 was slightly modified. The light source was a pyridine dye laser pumped by an argon ion laser, with its output at 360 nm and repetition rate at 113.2 MHz. The frequency 113.2 MHz is the harmonics of the base frequency (37.734 MHz) provided by the mode locker. The dichroic beam splitter and the interference filter were models FT395 (Carl Zeiss) and 450DF65 (Omega Optical), respectively. The gain of the image intensifier also was modulated at 113.2 MHz.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy instrumentations. CCD, charged coupled device; MCP, microchannel plate photomultiplier; ND, neutral density.

Data Analysis and Image Processing

After Fourier transformation, the eight intensity images collected in one cycle were converted into the phase and modulation images. In this article, only the modulation images were used to represent the lifetime results. The preliminary modulation images were then calibrated against the lifetime standards to obtain the absolute modulation images. The lifetime standards used were pyridine-1 in propylene glycol (0.78 ns) for C-SNAFL2, rhodamine B in water (1.68 ns) for dx-DMNERF and dx-OG514, and p-bis(o-methyl styryl)benzene in propylene glycol for DND-160. These homogeneously distributed lifetime standards also assisted the corrections of uneven illumination and spatial heterogeneity on the image intensifier. The noisy background signals were suppressed further by the application of masks to the modulation images. The final pH images were constructed based on in vivo calibration curves obtained on the same day.

pH Calibration Curves

The pH calibration curves were constructed based on the in vivo modulation responses acquired from cells in which the intracellular proton ion activities were clamped so that they would be the same as those in the extracellular buffers with the nigericin/high K+ method (39). The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The extracellular buffer contained 5 mM glucose, 20 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES) or piperazine-N, N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 120 mM KCl, and 20 mM NaCl. Concentrated Tris-base solution was used to adjust the buffer pH to between 6 and 8. Nigericin was diluted to a final concentration of 5 μM from the 10-mM stock solution in absolute ethanol. PIPES buffers were used when the desired pH values were below 6.7. Cells were incubated with the nigericin/high K+ buffers at different pH values for 10 min before the collection of pH calibration points. Prolonged incubation with the ionophores can degrade cell viability and affect the imaging results.

The intracellular pH calibration curves were also determined from the lysosomal images. The lysosomal pH was clamped to the pH value of the 2-(N-morpholino)ethane sulfonic acid (MES) buffer in the presence of 20 μM of monensin and 10 μM nigericin. Monensin is a kind of Na+/H+ ionophore, and its stock solution was prepared in absolute ethanol. The MES buffered sodium saline consisted of 5 mM glucose, 20 mM MES, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 130 mM NaCl, and 10 mM KCl.

Perturbation of the Intracellular pH

CHO cells are used as the model system to examine the perturbation effects to the cytosolic pH. The first strategy we used was to pulse the cells with a membrane-permeable weak base, NH3/NH4+, or a weak acid, CO2/HCO−3, and then follow the compensation and recovery of the cytosolic pH. The NH3/NH+4 solution was prepared by dissolving NH4Cl crystal in HBSS to the desired working concentrations without changing the original pH HBSS value of 7.3. The weak acid CO2/HCO−3 solution was prepared with 5 mM glucose, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 17 mM NaHCO3. The pH value of the CO2/HCO−3 solution decreased from 9.0 to 7.3 after the 30-min incubation with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The second strategy was to apply 2 μM nigericin to the extracellular buffers that contained no sodium and potassium ions. Nigericin was diluted in the N-methyl-D-glucammonium chloride (NMGCl) solution, which contained 140 mM NMGCl, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM HEPES. Concentrated HCl was added to the solutions to adjust the pH to 7.4. In the pH recovery step, bovine albumin (BA) was added to the NMGCl solution to the final concentration of 5 mg/ml to scavenge nigericin from the cell membranes. The second NMGCl solution was prepared by replacing 50 mM NMGCl salt with the same amount of NaCl. The addition of Na+ activated the Na+/H+ exchangers on the cell membranes and raised the cytosolic pH. Afterward, cytosolic alkalization was stopped by the addition of 0.1 mM amiloride, an inhibitor to the Na+/H+ exchanger proteins. The perturbation effects to lysosomal pH were examined by incubating the resting cells with 10 μM monensin, 600 nM bafilomysin A1 (BafA1), or 120 nM concanamycin A (ConA) for 1 h. The stock solutions of BafA1 and ConA were prepared in DMSO.

RESULTS

Determination of the Resting Cytosolic pH of Different Cell Lines

We previously reported the pH-dependent intensity decays of several commonly used pH indicators, seminaphtofluoresceins, seminaphthorhodafluors, and 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5(and 6)-carboxy-fluorescein (40). A list of the potential pH indicators suitable for lifetime-based pH imaging has been suggested. However, in the simulated cytoplasm with 2% BA, most pH indicators do not display adequate pH-dependent lifetime sensitivities (data not shown). The decrease of lifetime sensitivity is likely due to the association of BA with the pH probes. In fact, the lifetime sensitivities of many ion-sensitive indicators are seriously affected by their interactions with proteins (16,32,41). In the present study, C-SNAFL2 was chosen to measure the cytosolic pH because of its substantial pH-dependent modulation sensitivity in the presence of BA and its high absorbance at the 514-nm output of the argon ion laser.

The membrane-permeable diacetate derivative of C-SNAFL2 was applied to living cells to monitor the in vivo pH-dependent fluorescent signals at the red emission range (635 ± 50 nm). The cytosolic pH was adjusted to different levels according to the nigericin/K+ method (39). The intensity images and the corresponding modulation images of fibroblast cells loaded with C-SNAFL2 are shown in Figure 2. When the cytosolic pH was increased from 6.60 to 7.30 and 7.80, the intracellular fluorescence intensities did not change significantly, but the cellular modulation responses increased gradually to 35% for pH 7.30 and to 50% for pH 7.80. This observation was consistent with the steady state fluorescent results shown in Figure 3, where only minor pH-dependent intensity changes were observed in the red emission region of C-SNAFL2.

FIG. 2.

Intensity images (top) and corresponding modulation images (bottom) of living fibroblasts stained with carboxy-SNAFL2. The cytosolic pH values were clamped at pH 6.60, 7.30, and 7.80 individually with the high K+/nigericin method.

FIG. 3.

The in vitro pH-dependent emission spectra of carboxy-SNAFL2 and its pH-dependent modulation responsive curves (in vivo and in vitro) obtained at the red emission region (635 ± 25 nm).

The pH-dependent modulation responses of C-SNAFL2 obtained from the pH buffers and from the 3T3 fibroblast cells are shown in the inset in Figure 3. The in vivo calibration points and the corresponding standard errors were calculated from at least three independent cellular imaging results. Similar pH calibration curves for C-SNAFL2 were established from the CHO cells and MCF-7 cells. Based on the in vivo calibration curves, the resting cytosolic pH values determined from 3T3 fibroblasts, CHO cells, and MCF-7 cancer cells were 7.40, 7.20, and 7.15, respectively (Table 1). In fact, the measurement errors for the pH values reported in this article were overestimated and expressed in linear scales. The distinct cytosolic pH levels of these cell lines are shown in Figure 4. Compared with other fluorescence imaging methods, the cytosolic pH values determined by our FLIM measurements produced smaller experimental errors and decreases in the physiological pH range (Table 1). The slightly lower cytosolic pH values observed for MCF-7 cells agreed well with those reported for malignant cells (42–44). The lower cytosolic pH is a characteristic of certain cancer cells and might be related to their susceptibility to chemotherapeutic drugs. From our cytosolic pH imaging results, we concluded that the FLIM instrumentation can distinguish pH differences as small as 0.1 pH unit in living cells when using appropriate pH lifetime probes.

Table 1.

Comparison of Resting Cytosolic pH Levels of Adherent Cells Obtained From Different Fluorospectrometric Methods

| Adherent cells | Cytosolic pH* | |

|---|---|---|

| From FLIM | From the literature (reference) | |

| 3T3 Fibroblasts | 7.40 ± 0.05 | 7.40 (32) 6.83 ± 0.38 (56) |

| CHO cells | 7.20 ± 0.04 | 7.10 (32) 7.3 ± 0.2 (31) |

| MCF-7 cells | 7.15 ± 0.03 | 6.65 ± 0.4 (8) 6.80 (42) |

The standard errors of the measured pH values are expanded in estimated linear scales to include all possible measurement errors. CHO, chinese hamster ovary; FLIM, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy.

FIG. 4.

Different adherent cell lines display different levels of cytosolic pH. The average cytosolic pH values were 7.40 for 3T3 cells (a), 7.20 for Chinese hamster ovary cells (b), and 7.15 for MCF-7 cells (c).

Manipulations of the Cytosolic pH in CHO Cells

Maintenance of the steady-state intracellular pH is critical to cell viability and cellular physiologic events. For example, the influx and efflux of protons in neurons have been shown to be connected to the recycling of neurotransmitters (12). Moreover, the steady-state intracellular pH differs from cell line to cell line and is determined by the buffering capacity of cytosol, the permeability of plasma membranes, and the activities of the acid and base transporters on the cell membranes. To demonstrate that FLIM is a useful method to monitor cytosolic pH variation, the cytosolic pH of the CHO cells was manipulated with several strategies, and the pH perturbations tracked by the FLIM measurements were compared with those reported in the literature.

The strategies that we used to manipulate the cytosolic pH were to pulse the living cells with basic and acidic media, incubate cells with ionophores, and inhibit the activity of acid and base transporters on cell membranes. These methods have been widely used in the literature to study the pH regulatory mechanisms of different cell types (12,45,46). The time courses of the cytosolic pH evolution in CHO cells are depicted in Figure 5. In Figure 5a, the cytosolic pH immediately increased from 7.20 to 7.80 after the bathing solution was changed to 20 mM NH3/NH4+ in HBSS. This rapid pH change was due to the fast diffusion of NH3 molecules across the cell membranes and its rapid association with the intracellular protons to form NH4+. In less than 5 min, the pH increase reached a plateau phase, which probably resulted from the delayed entry of NH4+ and the activation of cellular acid-loading mechanisms to counterbalance the cellular alkalinized effects. When the extracellular NH3/NH4+ stress was removed by rinsing the cells with clean HBSS, the cytosolic pH rapidly decreased to a level even below the initial resting pH. This phenomenon of cytosolic acidification was caused by the dissociation of intracellular NH4+ into NH3 and protons to compensate for the fast efflux of NH3. In a slow process, the acid-extrusion machinery, such as the Na+/H+ exchanger proteins, brought the cytosolic pH back to the normal physiologic value.

FIG. 5.

a–d: Time course of cytosolic pH fluctuations in Chinese hamster ovary cells after different manipulation steps. BA, bovine albumin; HBSS, Hank’s balanced salt solution.

The effect of acid loading on cytosolic pH is shown in Figure 5b. The cells were incubated with the CO2/HCO3− medium, and the increased intracellular CO2 level resulted in a transient decrease of cytosolic pH. Shortly after the decrease in pH, the HCO3−-dependent acid extrusion mechanisms were activated and tried to overcome the acute acidification effect to the cells. As a consequence, the cytosolic pH steadily increased. Ten minutes later, the cells were rinsed with clean saline to remove the extracellular CO2/HCO3−. The trapped CO2 molecules were then rapidly released from the cytosol, and then the cytosolic pH increased accordingly. The magnitude of the pH increase was not as significant as that reported in literature because we did not have a micro-incubator system to acquire the pH fluctuations right after the medium change and in real time (45). The cytosolic pH level slowly recovered to the physiologic value. The possible acid-extrusion mechanisms during the recovery step included the activations of HCO3−/Cl− and K+/H+ exchanger proteins and the metabolic generation of protons inside the cytosol.

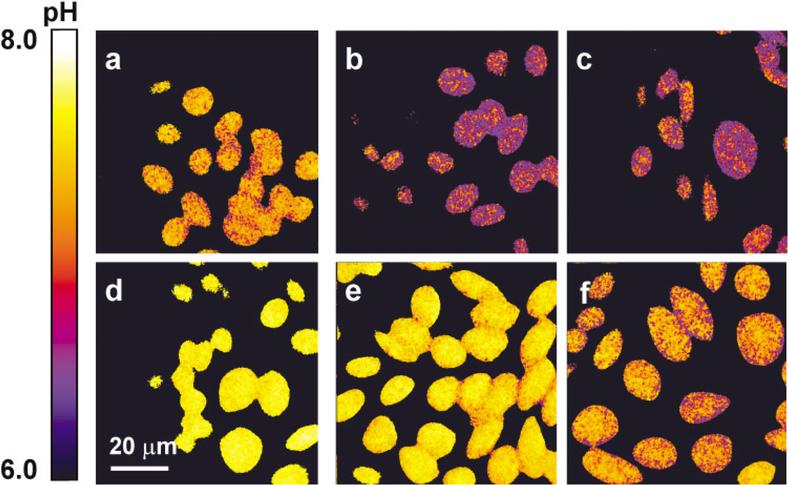

The perturbations of the cytosolic pH after the treatments of ionophores and transporter inhibitors were followed by the FLIM measurements (Fig. 5c,d). At the beginning, the incubation medium HBSS was replaced with a solution in which the Na+ and K+ ions were completely substituted with NMG+. The cytosolic pH gradually decreased after the application of 2 μM nigericin. Nigericin is a K+/H+ ionophore that assists in the exchange of protons and potassium ions across the cell membranes. Because the extracellular K+ was depleted in the NMG+ solution, the presence of nigericin on the cell membranes could facilitate the efflux of K+ and the influx of protons and decrease the cytosolic pH level. BA was then added to the incubation medium to scavenge nigericin and stop the decrease of pH. The subsequent steps were the incubation of the nigericin-treated cells with the weak base NH3/NH+4 solution followed by a rinse in clean HBSS, which induced a similar response of rapid pH increase and slow recovery (see Fig. 5a). In contrast, a gradual increase of the cytosolic pH was observed (Fig. 5d) when 50 mM NMG+ was substituted with Na+ in the NMG solution after treatment with nigericin. The increase was due to the activation of the Na+/H+ exchangers on the plasma membranes after the addition of sodium ions. A type of Na+/H+ exchanger inhibitor, amiloride, was immediately added to the medium to block the increase in pH. The cytosolic pH was steadily restored to the resting level after rinsing off the amiloride. A series of pH images obtained from the different manipulation steps shown in Figure 5c are shown in Figure 6. These images clearly reflect the cytosolic pH fluctuations at different stages. Our measurements demonstrated the capability of FLIM to track the fluctuations of intracellular pH.

FIG. 6.

Treatments of ionophores and weak bases perturb cytosolic pH levels of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. a: CHO cells were bathed in the NMG+ solution. b: Nigericin was added to the solution and incubated with CHO cells for 5 min. c: Nigericin was scavenged after the addition of bovine albumin, to 5 mg/ml. Incubation of CHO cells with 20 mM NH3/NH4+ for 2 (d) and 10 (e) min. f: CHO cells were rinsed and incubated with Hank’s balanced salt solution for 20 min.

Determination of the Lysosomal pH of Living 3T3 Fibroblasts

Very few fluorescent indicators have been reported for the fluorometric determinations of vesicular pH. The fluorescent emissions of most pH probes are strongly quenched in acidic environments, and it is difficult to introduce the pH probes into the acidic organelles. The preferred indicators chosen for endosomal pH imaging are fluorescein and C-fluorescein (39,47). However, these fluorophores are easily photo-bleached and are insensitive to pH values below 5. Recently, different types of fluorescein derivatives such as Oregon Green carboxylic acid and Rhodol Green carboxylic acid have been developed and widely employed to measure lysosomal and endosomal pH (13,48). These probes exhibit better photostability than does fluorescein and have pKa values between pH 4 and 6. Moreover, substantial pH-dependent lifetime sensitivities of these probes have been observed from frequency-domain intensity decay measurements (34). Another novel acidic probe, DND-160, has been suggested as a potential pH lifetime probe in acidic environments (49). No lifetime-resolved pH imaging data have been reported with these acidic probes. In the following section, the lysosomal pH distributions in 3T3 fibroblasts obtained from the intracellular lifetime responses of these novel acidic probes are described.

The intensity and lifetime images of one 3T3 fibroblast cell with its the acidic compartments highlighted by DND-160 are shown in Figure 7. Because of its substantial pH-dependent spectral shifts (Fig. 7), DND-160 originally was reported as an excitation/emission ratio probe (50); however, substantial pH-dependent lifetime changes were measured from its blue emission region in the buffer solutions (49). DND-160 immediately diffused across the membrane and accumulated in the acidic organelles after incubation with the cells. However, the cellular stain obtained by this diffusion process faded rapidly, likely due to the depletion of DND-160 through the exocytosis pathway. As a result, it was very difficult to acquire the lysosomal images and construct the in vivo pH calibration curve of DND-160 when using a short labeling time.

FIG. 7.

In vitro pH-dependent spectral shifts and lifetime responsive curves of DND-160 and the intensity and pH images of a DND-160–stained 3T3 fibroblast.

To obtain good image contrast for the DND-160– stained cells, the pinocytosis activity of fibroblasts was used to load DND-160 into the cells. In principle, living fibroblasts can actively internalize the extracellular probes and specifically transport them into acidic organelles such as endosomes and lysosomes. The cells need to be incubated with the probe-free saline for another hour to deplete the fluorophores residing in the recycling endosomes. The stained cells were incubated further with the high K+ medium containing nigericin and monensin to obtain the pH-calibrated lifetime responses (Fig. 7). The corresponding in vitro calibration curve is also shown in Figure 7. Based on the pH calibration curves, the average lysosomal pH of the living 3T3 fibroblasts was 4.6 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Lysosomal pH Levels Derived From our FLIM Measurements With Those From Other Fluorospectrometric Methods*

| Low pH indicator | Lysosomal pH | |

|---|---|---|

| From FLIMa | From the literatureb (reference) | |

| OG-514 carboxylic acid dextrans | 4.9 ± 0.1 | N/A |

| DM-NERF dextrans | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3–4.7 (52) |

| DND-160 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.4–4.5 (50) |

| Fluorescein dextrans | N/A | 5.14 (51) |

| 4.7–4.8 (47) | ||

| Carboxy-fluorescein dextrans | N/A | 4.5–4.9 (57) |

| OG-488 dextrans/Texas Red polystyrene | N/A | 4.7–4.9 (58) |

FLIM, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy; N/A, not available.

Mean ± standard error.

Range.

In contrast to C-SNAFL2, the modulation sensitivity of DND-160 to pH was significantly reduced inside the cells, and the lysosomal pH maps of the DND-160–stained cells were very heterogeneous (Fig. 7). The blue emission of DND-160 at neutral to alkaline pH also was strongly quenched, which hindered the acquisition of reliable calibration points. The likely explanations for the heterogeneous pH maps are the nonspecific binding of DND-160 to the various cellular components and its nonspecific accumulation in different acidic compartments. In the presence of 2% BA, the pH-dependent lifetime sensitivity of DND-160 was seriously reduced (data not shown). In addition, the distinctly stained structures disappeared, and the fluorescence of DND-160 was observed with the entire cell after the treatments with ionophores and high K+. Another possibility is the autofluorescence of the cellular NAD(P)H and flavins because their excitation and emission wavelengths overlapped with those of DND-160. However, the control signals collected from the nonstained cells were only at the noise level. As a result, the binding of DND-160 to the different cellular components and its nonspecific distribution within the cells appear to be the most likely reasons for the decreased pH resolution in the lysosome images.

To minimize the interactions of the loaded fluorescent indicators with the cellular components and to properly image the lysosomal pH, the pH indicators dx-DMNERF and dx-OG514 were used to image 3T3 fibroblasts. The pH-dependent lifetime sensitivities of DM-NERF and OG-514 were characterized previously and found to have suitable pH working ranges to image the acidic vesicles (34). Conjugation of the highly charged, high-molecularweight dextran molecules to the acidic probes facilitates the internalization of probes into cells and retains them within the lysosomes (Fig. 8). In addition, the special α−1,6-polyglucose linkage of dextrans is resistant to the hydrolysis of glycosidases and protects the pH indicators from being degraded inside the lysosomes. The pH-dependent intensity and modulation images of a dx-DMNERF– loaded 3T3 fibroblast cell are shown in Figure 8. The lysosomal pH value was adjusted from 4.4 to 5.5 with the high K+/ionophore pH clamp method, and the corresponding modulation response decreased from 60% to 50%.

FIG. 8.

Intensity images (top) and corresponding modulation images (bottom) of living 3T3 fibroblasts loaded with DM-NERF dextrans. In the presence of monensin and nigericin, lysosomal pH levels of cells were adjusted to the pH values of the incubation 2-(N-morpholino ethane sulfonic acid buffers: 4.40, 4.90, and 5.50.

The in vivo pH calibration curves established from the intracellular modulation responses to dx-DMNERF and dx-OG514 are shown in Figure 9. According to these curves, the average lysosomal pH values of the resting 3T3 fibroblasts were determined and are listed in Table 2. The results obtained from the FLIM measurements on DND-160, dx-DMNERF, and dx-OG514 were comparable to the lysosomal pH values acquired from the intensity-based measurements (Table 2). The vesicular pH determined from the dx-DMNERF–stained cells generally displayed greater uncertainties (standard error > 0.2) than did the dx-OG514–stained cells, probably due to the higher pKa value of dx-DMNERF (5.4) in comparison with the resting lysosomal pH (~4.7). In contrast, dx-OG514 behaved as a useful lysosomal pH indicator for its substantial lifetime sensitivity between 4.0 and 5.0 and its bright emission at the low pH range. As summarized from the lifetime-based imaging results of DND-160, dx-DMNERF, and dx-OG-514, the lysosomal pH of resting 3T3 fibroblast should fall between 4.5 and 4.9.

FIG. 9.

The pH-dependent modulation responses of DM-NERF dextrans and OG-514 dextrans and changes in lysosomal pH detected by these probes after treatments of the proton pump inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) and the ionophore monensin. Left: In vitro and in vivo pH calibration curves of DM-NERF and OG-514 established in buffers and cells. Right: Lysosomal pH levels of 3T3 fibroblasts increase after treatments with BafA1and monensin.

Effects of Ionophores and Proton Pump Inhibitors on Lysosomal pH

The acidic environment inside the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatuses, secretory vesicles, endosomes, and lysosomes are critical to intracellular transportation and degradation functions of living cells (42,51–53). In general, the vesicular acidification is accomplished by activations of the vacuolar-type H+ pumps and the proton and cation exchangers on the vesicular membranes. It has been widely reported in the literature that treatments of specific ionophores and proton pump inhibitors can stop the vesicular acidifications and significantly increase lysosomal and phagosomal pH (8,54). With the use of similar inhibitory strategies, we manipulated the lysosomal pH of 3T3 fibroblasts and evaluated the performance of FLIM to follow lysosomal alkalization.

As shown in Figure 9, a significant increase in lysosomal pH was observed for dx-DMNERF– and dx-OG514–loaded fibroblast cells after the 1-h incubation of BafA1 and monensin. BafA1 is an effective inhibitor to the vacuolar-type proton pump and monensin is a K+/H+ exchanger. In the dx-DMNERF–loaded cells, treatments with BafA1 and monensin increased the lysosomal pH from the resting value of 4.4 ± 0.3 to 5.0 ± 0.1 and 5.1 ± 0.1, respectively. A similar phenomenon was observed for the dx-OG514– stained lysosomes, in which lysosomal pH increased from 4.9 ± 0.1 to 5.9 ± 0.5 and 5.5 ± 0.5 after treatments with BafA1 and monensin, respectively. The standard errors were calculated based on the number of measurements. Although significant pH increases in lysosomes were observed after the BafA1 and monensin treatments, the absolute increase determined from the dx-DMNERF–stained cells were relatively lower than that obtained from the dx-OG514-stained cells. The substantial pH differences between the control and drug-treated cells are shown in Figure 10.

FIG. 10.

Lysosomal pH images of 3T3 fibroblasts loaded with OG-514 dextrans. a: A resting 3T3 fibroblast. Cells treated with monensin (b) and bafilomycin A1 (c) for 1 h. The average lysosomal pH values derived from images a, b, and c were 4.9, 5.5, and 5.9, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the performance of FLIM in imaging pH distributions in cytosol and lysosomes. We used the term pH to represent the hydrogen ion activity of the continuous aqueous phase within the cellular compartments. The fluorescent indicators used in this study were characterized previously and showed appropriate pH-dependent lifetime sensitivities (34,40,49). In other words, these indicators displayed distinct fluorescence lifetimes at their protonated and de-protonated states. C-SNAFL2 was chosen as the cytosolic pH indicator because of its significant in vivo lifetime sensitivity and strong red emission. Another widely used fluorescent pH indicator, C-SNARF1, could not be used in the FLIM measurements because its lifetime sensitivity is strongly reduced inside cells. The association of C-SNARF1 to intracellular proteins was found to significantly modify its pH-dependent lifetime responses (32). DND-160 also is not a suitable probe for lysosomal pH imaging. The cellular distribution of DND-160 is nonspecific, and its interactions with the cellular components greatly reduce its lifetime sensitivity. The dextran-conjugated acidic pH indicators DM-NERF and OG-514 are preferable to the membrane-permeable DND-160 for lysosomal pH imaging. Dextran conjugation not only facilitates the internalization of the probes through the fluid phase pinocytosis but also protects the probes from intracellular enzymatic digestion. As a result, good pH indicators for intracellular lifetime-based imaging should have very weak interactions with the cellular components and should be able to be loaded into the destined cellular compartments with the least invasive strategies.

We demonstrated that the changes in cytosolic pH result from different manipulation steps that can be followed by FLIM measurements. The pH responsive curves we obtained were comparable to the results reported in the literature when using fluorescence intensity ratio methods. However, we did not have a micro-incubation system for the cells and, hence, could not track intracellular pH fluctuations in real time. This instrumentation can accommodate the stained living cells and synchronize the microscopy acquisitions and environmental changes. The instant detection of the cellular pH fluctuations is necessary to studies of the regulatory determinants of cellular pH such as the buffering powers of cytosol and the activities of the acid and base transporters.

Compared with the cytosolic pH images, the lysosomal pH images obtained from the FLIM measurements showed greater degrees of heterogeneity. There are several possible explanations for this result. First, pH heterogeneity is greater in individual lysosomes. The resolution of our widefield microscope cannot resolve every lysosome to assign its pH value; it can only represent the average values from the highlighted lysosomal regions surrounding the nucleus. Second, the contributions of the out-of-focus fluorescence and the scattering become more significant when the signals are collected from the delicate vesicular structures rather than from the entire cytoplasm. Third, the standard error of the measured lysosomal pH is definitely higher than the cytosolic pH because the lysosomal signals are obtained from a smaller number of pixels.

The sensitivity of vesicular pH to treatments with inhibitors to proton pumps depends on the cell type. After BafA1 treatment, the changes in lysosomal pH in epidermoid carcinoma cells were much higher than those obtained from our measurements on fibroblasts (51). Another well-known inhibitor to the vacuolar-type proton pumps, ConA, did not effectively change the lysosomal pH of 3T3 fibroblasts in our experiments (data not shown) but did show a very strong inhibitory effect on the breast cancer cells (8,55)

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

This life-based imaging study demonstrated the capability of FLIM to measure the resting cytosolic and lysosomal pH values of different cell types. FLIM followed the pH fluctuations in cytosol and lysosomes after the application of weak bases, weak acids, ionophores, and proton pump inhibitors. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use fluorescence lifetime imaging to resolve the pH distributions in acidic vesicles with pH indicators other than fluorescein or C-fluorescein.

To explore the possible pH gradients existing in cytosol and to resolve pH variations across acidic vesicles, we need to identify more fluorescent pH indicators with substantial lifetime sensitivities at the desired pH ranges. In addition, implementation of pseudo-confocal capability to FLIM is necessary to improve the spatial resolution of the time-resolved images to the submicron level. One possibility is to install the multiphoton multifocal microscope (19) in our present FLIM instrument, which we are exploring.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Garlapati S, Dahan E, Shapira M. Effect of acidic pH on heat shock gene expression in leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1999;100:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denison SH. pH Regulation of gene expression in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 2000;29:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vriesema AJ, Dankert J, Zaat SA. A shift from oral to blood pH is a stimulus for adaptive gene expression of Streptococcus gordonii CH1 and induces protection against oxidative stress and enhanced bacterial growth by expression of msrA. Infect Immun 2000;68:1061–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdineaud JP. At acidic pH, the diminished hypoxic expression of the SRP1/TIR1 yeast gene depends on the GPA2-cAMP and HOG pathway. Res Microbiol 2000;151:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashiro DJ, Maxfield FR. Regulation of endocytic processes by pH. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1988;9:190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henkel JR, Popovich JL, Gibson GA, Watkins SC, Weisz OA. Selective perturbation of early endosome and/or ?trans-Golgi network pH but not lysosome pH by dose-dependent expression of influenza M2 protein. J Biol Chem 1999;274:9854–9860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu F, Aniento F, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. Functional dissection of COP-I subunits in the biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. J Cell Biol 1997;139:1183–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altan N, Chen Y, Schindler M, Simon SM. Defective acidification in human breast tumor cells and implications in chemotherapy. J Exp Med 1998;187:1583–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crivellato E, Candussio L, Rosati AM, Decorti G, Klugmann FB, Mallardi F. Kinetics of doxorubicin handling in the LLC-PK1 kidney epithelial cell line is mediated by both vesicle formation and Pglycoprotein drug transport. Histochem J 1999;31:635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz SJ, Terashima M, Mizunuma N, Slapak CA. Vesicular anthracycline accumulation in doxorubicin-selected U-937 Cells: participation of lysosomes. Blood 1997;89:3745–3754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow SY, Yen-Chow YC, Woodbury DM. Studies on pH regulatory mechanisms in cultured astrocytes of DBA and C57 mice. Epilepsia 1992;33:775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deitmer JW, Rose CR. pH Regulation and proton signalling by glial cells. Prog Neurobiol 1996;48:73–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn K, Maxfield FR, Whitaker JE, Haugland RP, Haugland RP. Fluorescence excitation ratio pH measurements of lysosomal pH using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Biophys J 1991;59:345a. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn KW, Mayor S, Myers JN, Maxfield FR. Application of ratio fluorescence microscopy in the study of cell physiology. FASEB J 1994;8:573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitetaker JE, Haugland RP, Prendergast FG. Spectral and photophysical studies of benzo[c]xantene dyes: dual emission pH sensors. Anal Biochem 1991;194:330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Despa S, Stells P, Ameloot M. Fluorescence lifetime microscopy of the sodium indicator sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate in Hela cells. Anal Biochem 2000;280:227–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlsson K, Liljeborg A. Simultaneous confocal lifetime imaging of multiple fluorophores using the intensity-modulated multiple-wavelength scanning (IMS) technique. J Microsc 1998;191:119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Squire A, Bastiaens PIH. Three dimensional images restoration in fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. J Microsc 1999;193:36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strub M, Hell SW. Fluorescence lifetime three-dimensional microscopy with picosecond precision using a multifocal multiphoton microscopy. Appl Phys Lett 1998;73:1769–1771. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Lederer WJ, Kirby MS, Johnson M. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of intracellular calcium in COS cells using Quin-2. Cell Calcium 1994;15:7–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.French T, So PTC, Weaver DJJ, Coelho-Sampaio T, Gratton E, Voss EW, Carrero J. Two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy of macrophage-mediated antigen processing. J Microsc 1997;185: 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastiaens PIH, Jovin TM. Microspectroscopic imaging tracks the intracelluar processing of a signal transduction protein: fluorescentlabeled protein kinase CβI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:8407–8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepperkok R, Squire A, Geley S, Bastiaens PIH. Simultaneous detection of multiple green fluorescence proteins in live cells by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Curr Cell Biol 1999;9:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wouters FS, Bastiaens PIH. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of receptor tyrosine kinase activity in cells. Curr Biol 1999;9:1127–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakobs S, Subramanian V, Schönle A, Jovin TM, Hell SW. EGFP and DsRed expressing cultures of Escherichia coli imaged by confocal, two-photon and fluorescence lifetime microscopy. FEBS Lett 2000; 479:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gadella TWJ Jr, Jovin TM. Oligomerization of epidermal growth factor receptors on A431 cells studied by time-resolved fluorescence imaging microscopy. A stereochemical model for tyrosine kinase receptor activation. J Cell Biol 1995;129:1543–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nett W, Deitmer JW. Simultaneous measurement of intracellular pH in the leech giant cell using 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5,6-carboxyfluorescein and ion-sensitive microelectrodes. Biophys J 1996;71: 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastiaens PIH, Majoul IV, Verveer PJ, Söling H-D, Jovin TM. Imaging the intracellular trafficking and state of the AB5 quaternary structure of cholera toxin. EMBO J 1996;15:4246–4253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Fernandez M, Tobin M, Clarke D, Gregory C, Jones G. A high sensitivity time-resolved microfluorimeter for real-time cell biology. Rev Sci Instrum 1996;67:3716–3721. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlsson K, Liljeborg A, Andersson RM, Brismar H. Confocal pH imaging of microscopic specimens using fluorescence lifetimes and phase fluorometry: influence of parameter choice on system performance. J Microsc 2000;199:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders R, Draaijer A, Gerritsen HC, Houpt PM, Levine YK. Quantitative pH imaging in cells using confocal fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Anal Biochem 1995;227:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srivastava A, Kirshnamoorthy G. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy could correct for probe binding while estimating intracellular pH. Anal Biochem 1997;249:140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vroom JM, Grauw KJd, Gerritsen HC, Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Watson GK, Birmingham JJ, Allison C. Depth penetration and detection of pH gradients in biofilms by two-photon excitation microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999;65:3502–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin H-J, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR. Lifetime-based pH sensors: indicators for acidic environments. Anal Biochem 1999;269:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nordstrom T, Rotstein OD, Romanek R, Asotra S, Heersche JDM, Manolson MF, Brisseau GF, Grinstein S. Regulation of cytoplasmic pH in osteoclast. J Biol Chem 1995;270:2203–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaturapanich G, Ishibashi H, Dinudom A, Young JA, Cook DI. H+ transporters in the main excretory duct of the mouse mandibular salivary gland. J Physiol 1997;503:583–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demaurex N, Downey GP, Waddell TK, Grinstein S. Intracellular pH regulation during spreading of human neutrophils. J Cell Biol 1996; 133:1391–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Johnson ML. Calcium imaging using fluorescence lifetime and long-wavelength probes. J Fluoresc 1992; 2:47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas JA, Buchsbaum RN, Zimniak A, Racker E. Intracellular pH measurements in ehrich ascites tumor cells utilizing spectroscopic probes generated in situ. Biochemistry 1979;18:2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR. Optical measurements of pH using fluorescence lifetimes and phase-modulation fluorometry. Anal Chem 1993;65:1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson RM, Carlsson K, Liljeborg A, Brismar H. Characterization of probe binding and comparison of its influence on fluorescence lifetime of two pH-sensitive benzo[c]xanthene dyes using intensity-modulated multiple-wavelength scanning techniques. Anal Biochem 2000;283:104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schindler M, Grabski S, Hoff E, Simon SM. Defective pH regulation of acidic compartments in human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) is normalized in adriamycin-resistant cells (MCF-7adr). Biochemistry 1996;35: 2811–2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon S, Roy D, Schindler M. Intracellular pH and the control of multidrug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:1128–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman MM, Wei LY, Roepe PD. Are altered pHi and membrane potential in huMDR 1 transfectants sufficient to cause MDR proteinmediated multidrug resistance? J Gen Physiol 1996;108:295–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bevensee MO, Boron WF. Manipulation and regulation of cytosolic pH. Methods Neurosci 1995;27:252–273. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grinstein S, Cohen S, Rothstein A. Cytoplasmic pH regulation in thymic lymphocytes by an amiloride-sensitive Na+/H+ antiport. J Gen Physiol 1984;1984:341–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1978;75:3327–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitetaker JE, Haugland RP, Ryan D, Dunn K, Maxfield FR. Dual excitation, pH sensitive conjugates of dextran and transferrin for pH measurement during endocytosis utilizing 514nm to 488nm excitation ratios. Biophys J 1991;59:358a. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin H-J, Herman P, Kang J-S, Lakowicz JR. Fluorescence lifetime characterization of novel low pH probes. Anal Biochem 2001;294: 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diwu Z, Chen C-S, Zhang C, Klaubert DH, Haugland RP. A novel acidotropic pH indicator and its potential application in labeling acidic organelles of live cells. Chem Biol 1999;6:411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y, Futai M, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. J Biol Chem 1991;266:17707–17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee RJ, Wang S, Low PS. Measurement of endosome pH following folate receptor-mediated endocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996; 1312:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D’Souza S, Garcia-Cabado A, Yu F, Teter K, Lukacs G, Skorecki K, Moore H-P, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. The epithelial sodium-hydrogen antiporter Na+/H+ exchanger 3 accumulates and is functional in recycling endosomes. J Biol Chem 1998;273:2035–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lukacs GL, Rotstein OD, Grinstein S. Determinants of the phagosomal pH in macrophages. In situ assessment of vacuolar H+-ATPase activity, counterion conductance, and H+ “leak”. J Biol Chem 1991;266: 24540–24548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hackam DJ, Rotstein OD, Zhang W-J, Demaurex N, Woodside M, Tsai O, Grinstein S. Regulation of phagosomal acidification. J Biol Chem 1997;47:29810–29820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanasugarn L, McNeil P, Reynolds GT, Tayor DL. Microspectrofluorometry by digital image processing: measurement of cytoplasmic pH. J Cell Biol 1984;98:717–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zen K, Biwersi J, Periasamy N, Verkman AS. Second messengers regulate endosomal acidification in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1992;119:99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ji J, Rosenzweig N, Griffin C, Rosenzweig Z. Synthesis and application of submicrometer fluorescence sensing particles for lysosomal pH measurements in murine macrophages. Anal Chem 2000;72:3497–3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]