Abstract

Background

Even low levels of substance misuse by people with a severe mental illness can have detrimental effects.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions for reduction in substance use in people with a serious mental illness compared with standard care.

Search methods

The Information Specialist of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group (CSG) searched the CSG Trials Register (2 May 2018), which is based on regular searches of major medical and scientific databases.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing psychosocial interventions for substance misuse with standard care in people with serious mental illness.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently selected studies, extracted data and appraised study quality. For binary outcomes, we calculated standard estimates of risk ratio (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) between groups. Where meta‐analyses were possible, we pooled data using a random‐effects model. Using the GRADE approach, we identified seven patient‐centred outcomes and assessed the quality of evidence for these within each comparison.

Main results

Our review now includes 41 trials with a total of 4024 participants. We have identified nine comparisons within the included trials and present a summary of our main findings for seven of these below. We were unable to summarise many findings due to skewed data or because trials did not measure the outcome of interest. In general, evidence was rated as low‐ or very‐low quality due to high or unclear risks of bias because of poor trial methods, or inadequately reported methods, and imprecision due to small sample sizes, low event rates and wide confidence intervals.

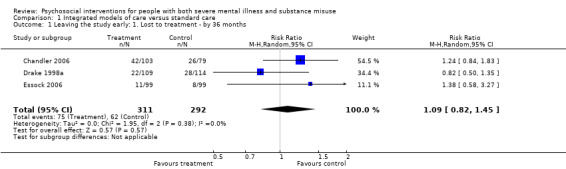

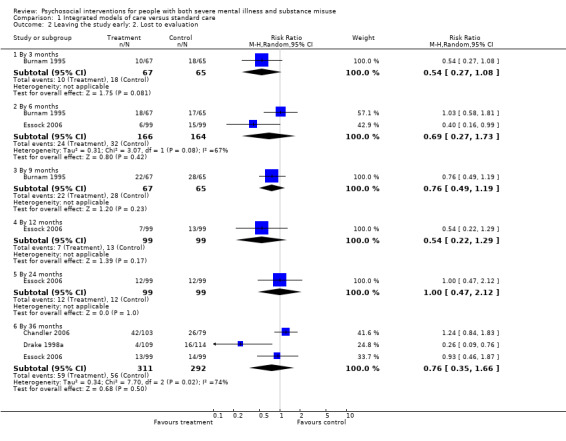

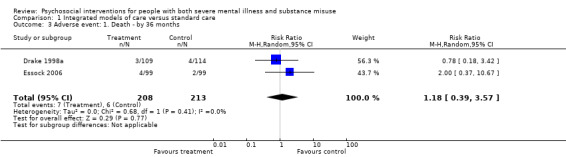

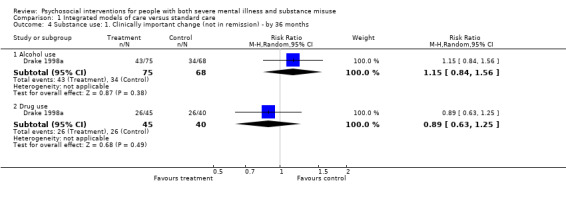

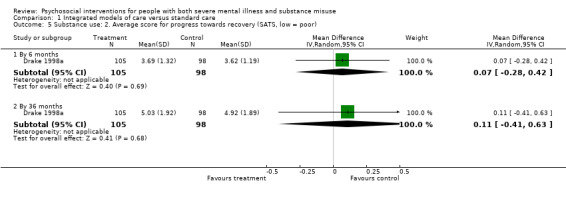

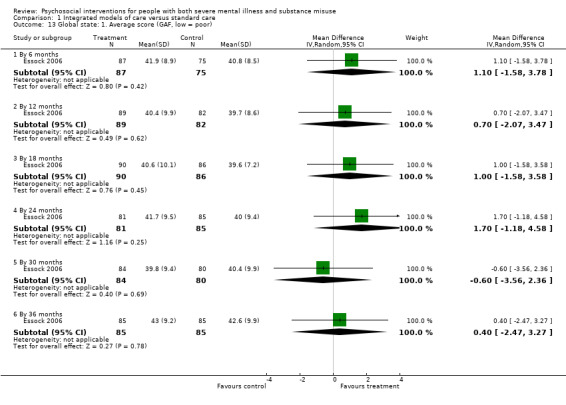

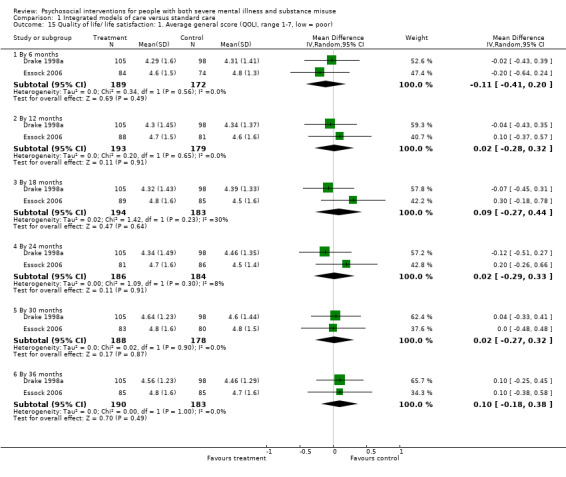

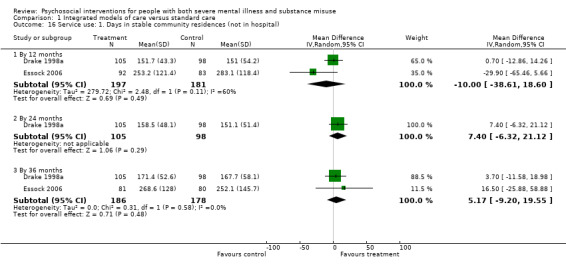

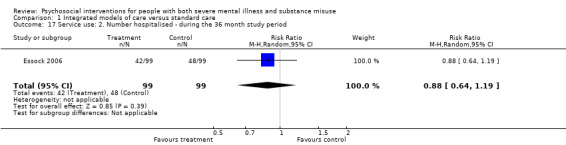

1. Integrated models of care versus standard care (36 months)

No clear differences were found between treatment groups for loss to treatment (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.45; participants = 603; studies = 3; low‐quality evidence), death (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.39 to 3.57; participants = 421; studies = 2; low‐quality evidence), alcohol use (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.56; participants = 143; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence), substance use (drug) (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.25; participants = 85; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence), global assessment of functioning (GAF) scores (MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐2.47 to 3.27; participants = 170; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence), or general life satisfaction (QOLI) scores (MD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.38; participants = 373; studies = 2; moderate‐quality evidence).

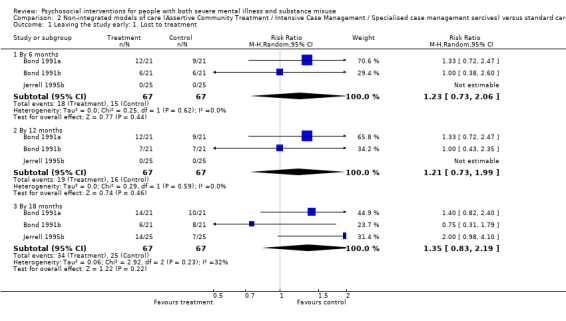

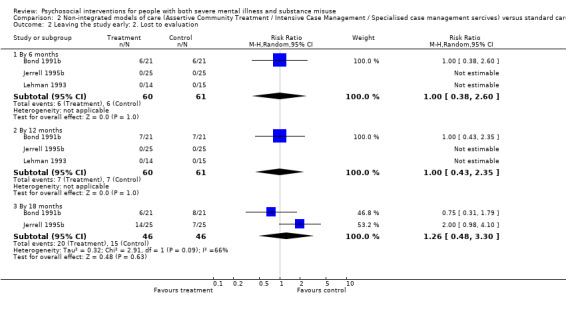

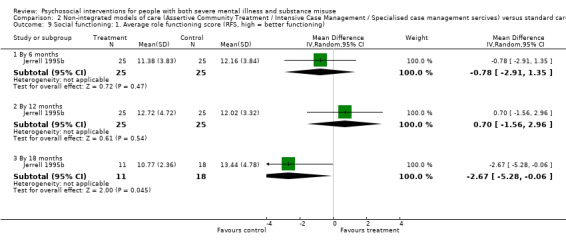

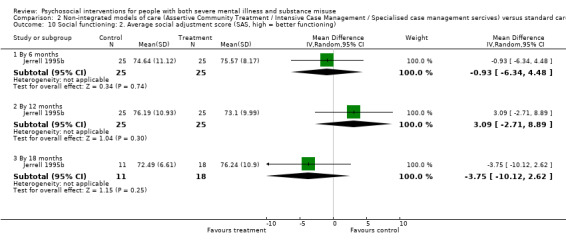

2. Non‐integrated models of care versus standard care

There was no clear difference between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment at 12 months (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.99; participants = 134; studies = 3; very low‐quality evidence).

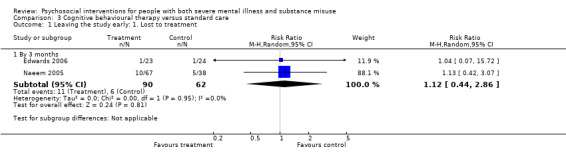

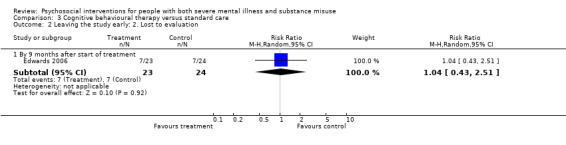

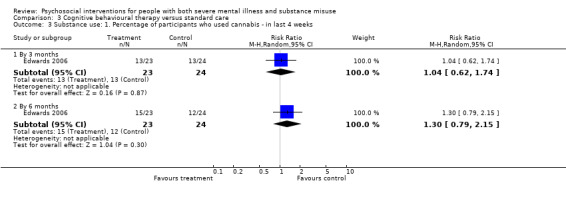

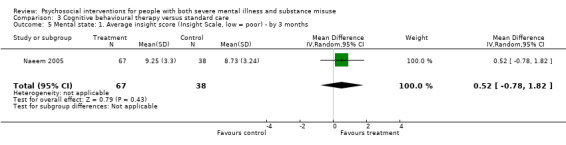

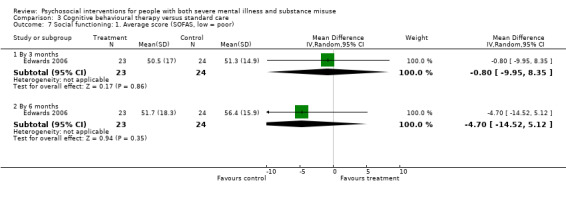

3. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care

There was no clear difference between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment at three months (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.86; participants = 152; studies = 2; low‐quality evidence), cannabis use at six months (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.15; participants = 47; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence) or mental state insight (IS) scores by three months (MD 0.52, 95% CI ‐0.78 to 1.82; participants = 105; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence).

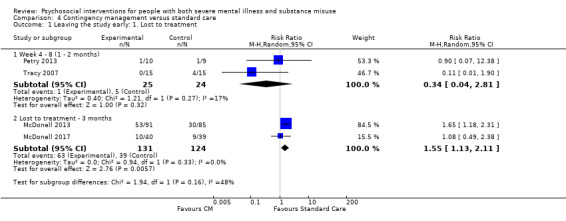

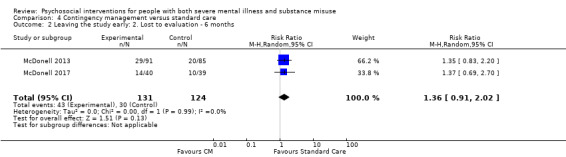

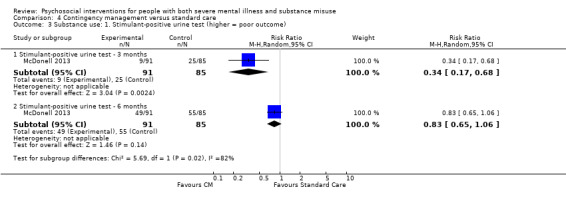

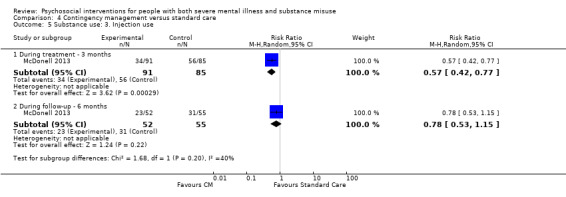

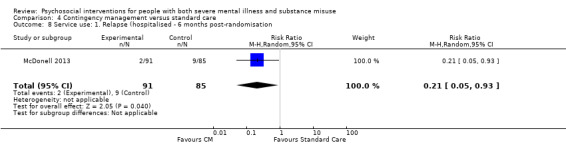

4. Contingency management versus standard care

We found no clear differences between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment at three months (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.11; participants = 255; studies = 2; moderate‐quality evidence), number of stimulant positive urine tests at six months (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.06; participants = 176; studies = 1) or hospitalisations (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.93; participants = 176; studies = 1); both low‐quality evidence.

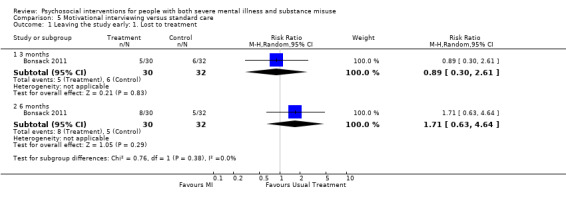

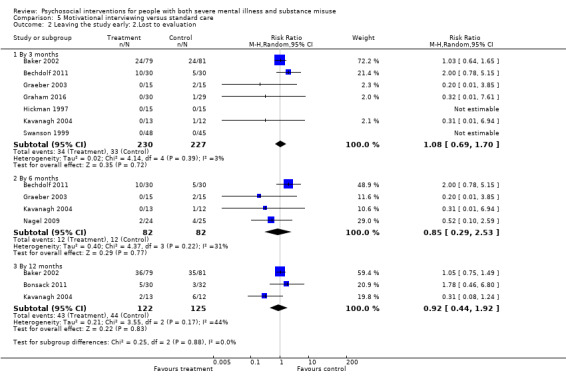

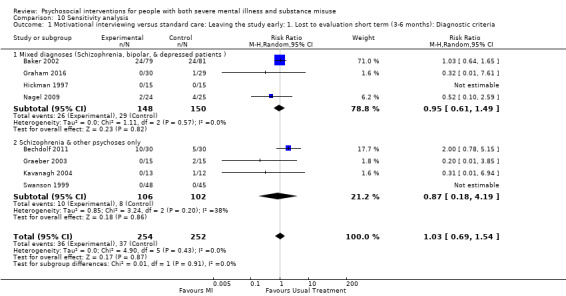

5. Motivational interviewing (MI) versus standard care

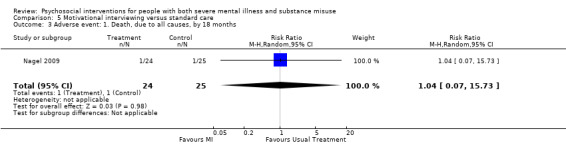

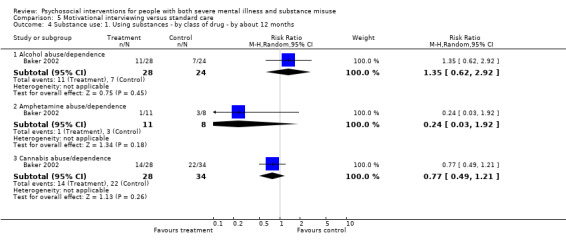

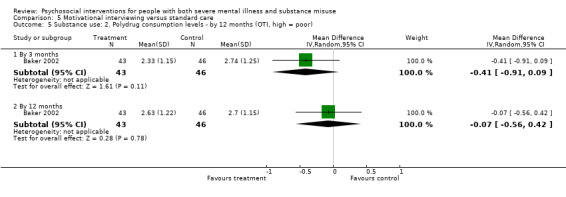

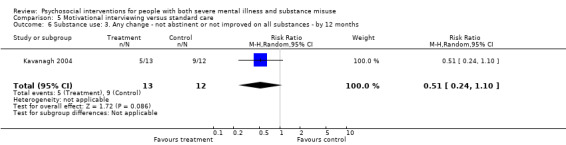

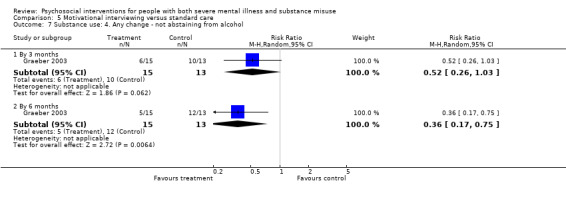

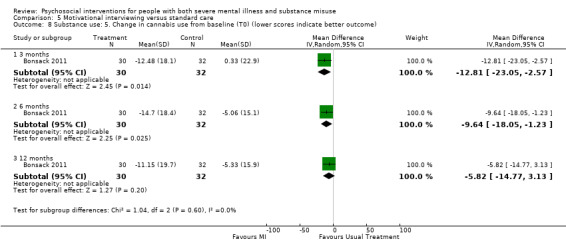

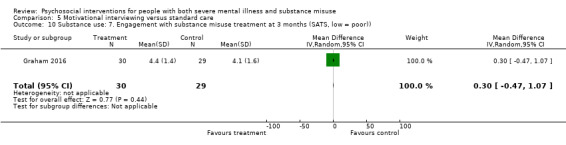

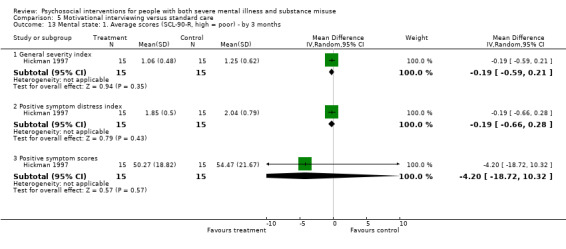

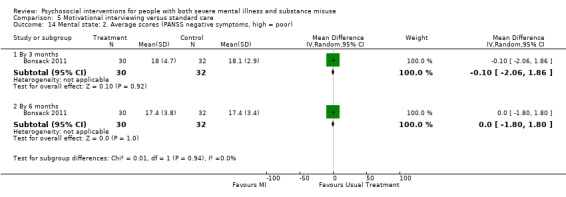

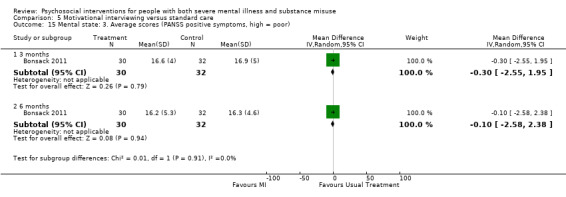

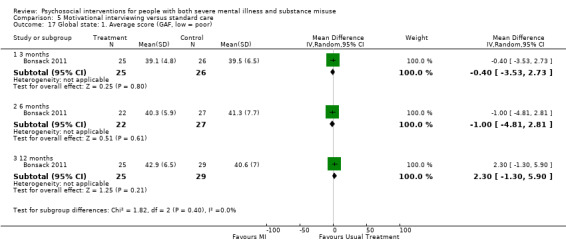

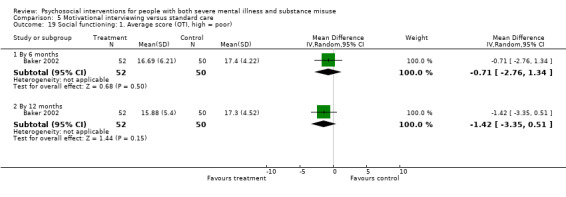

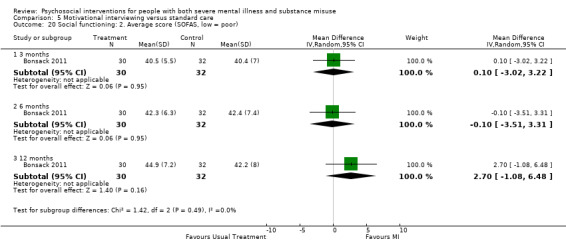

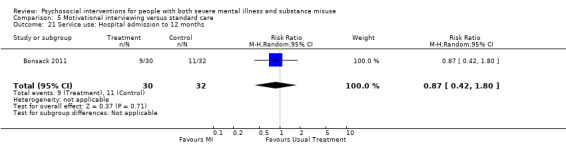

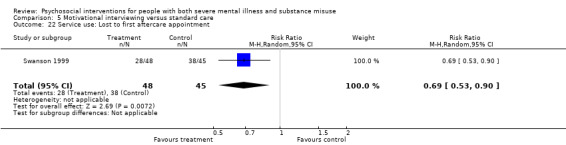

We found no clear differences between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment at six months (RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.63 to 4.64; participants = 62; studies = 1). A clear difference, favouring MI, was observed for abstaining from alcohol (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.75; participants = 28; studies = 1) but not other substances (MD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 0.42; participants = 89; studies = 1), and no differences were observed in mental state general severity (SCL‐90‐R) scores (MD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.21; participants = 30; studies = 1). All very low‐quality evidence.

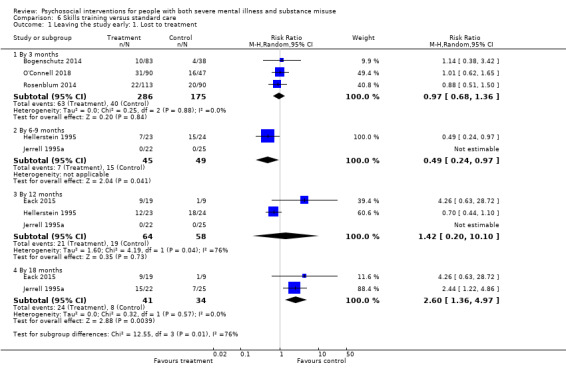

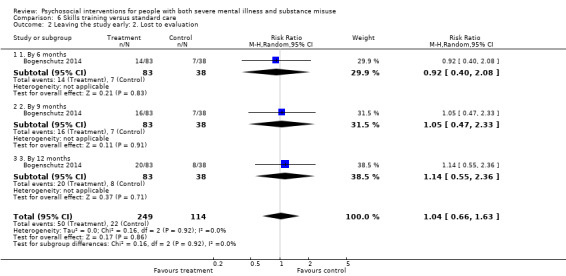

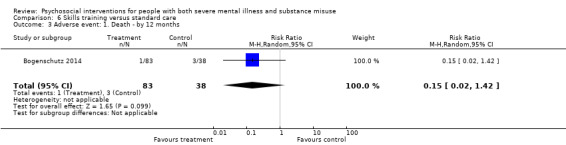

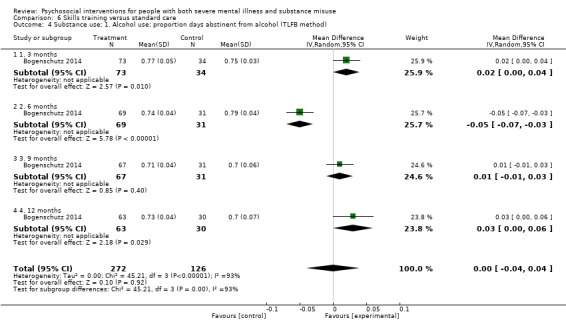

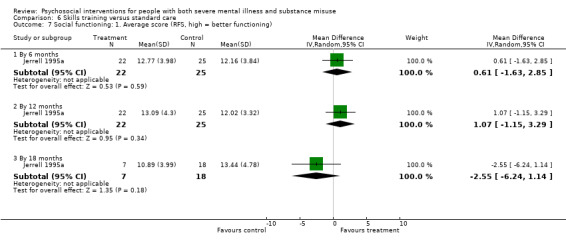

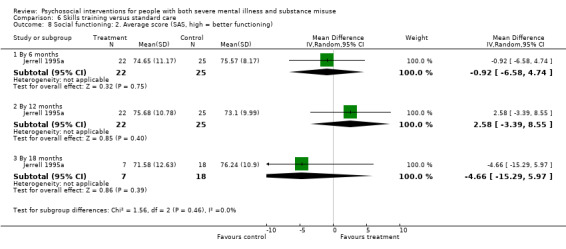

6. Skills training versus standard care

At 12 months, there were no clear differences between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.20 to 10.10; participants = 122; studies = 3) or death (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.42; participants = 121; studies = 1). Very low‐quality, and low‐quality evidence, respectively.

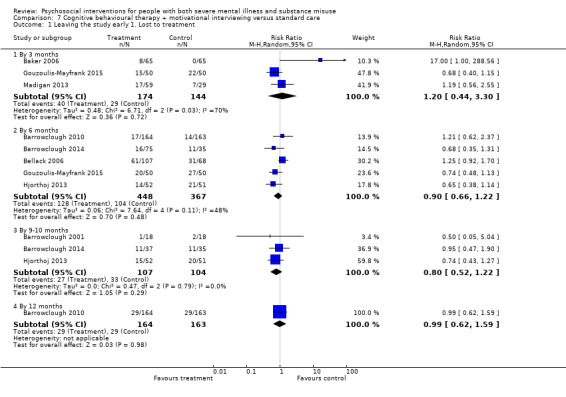

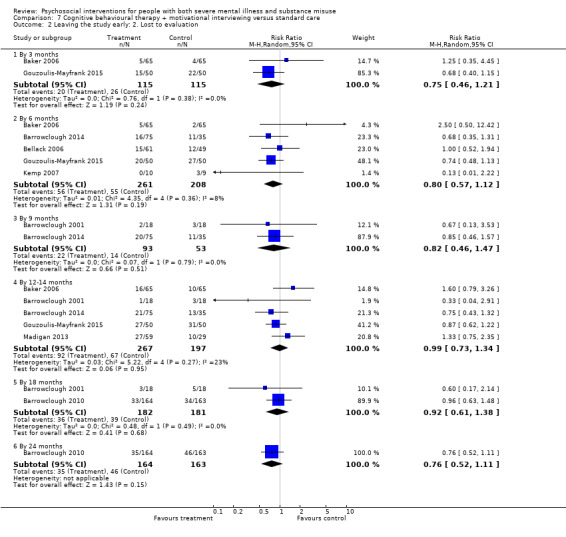

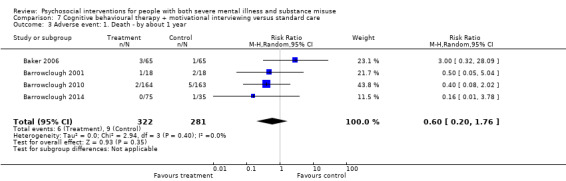

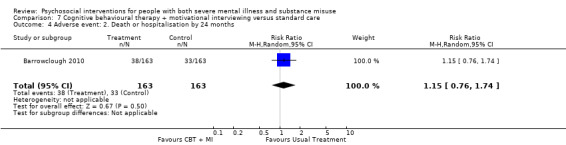

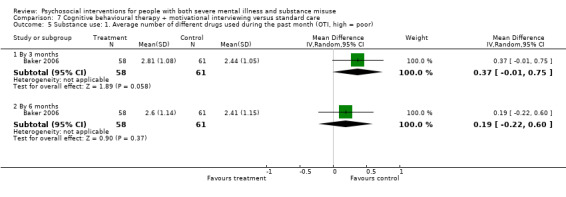

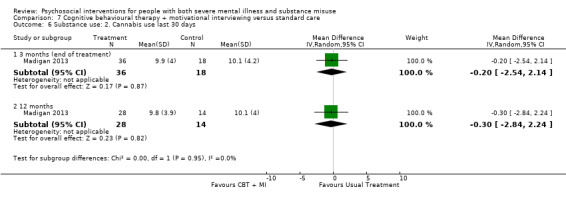

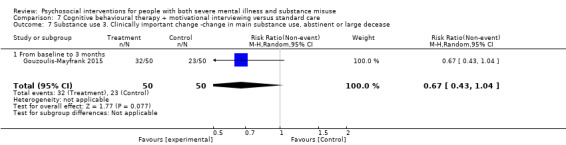

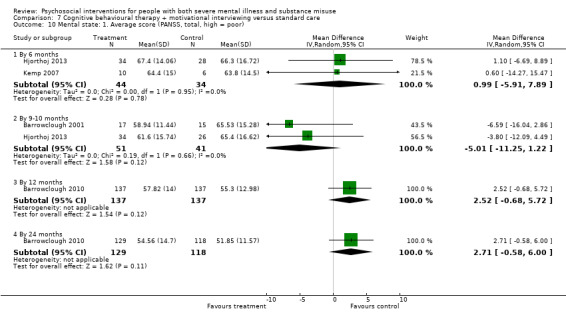

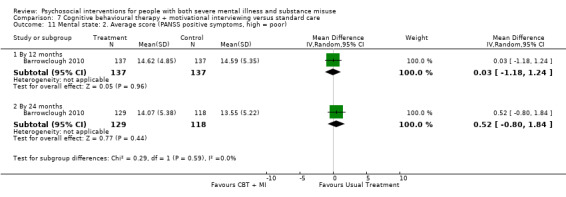

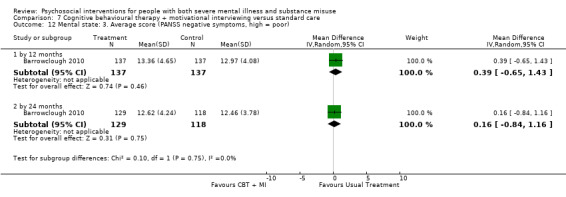

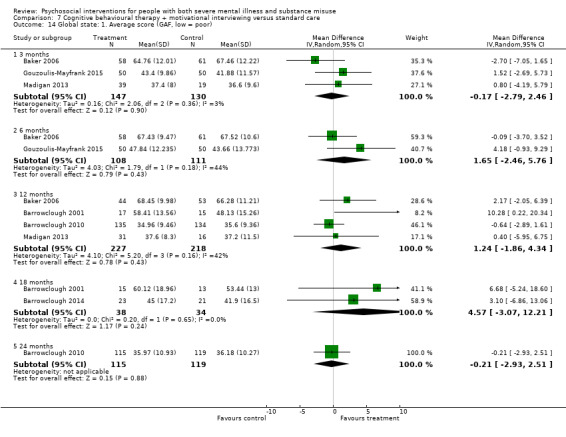

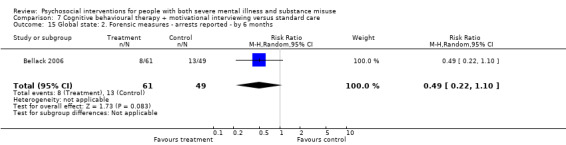

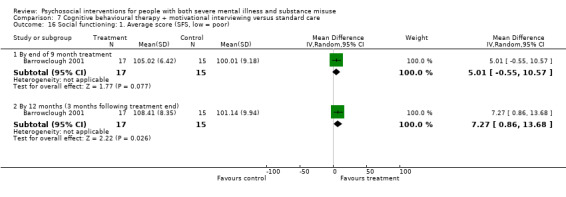

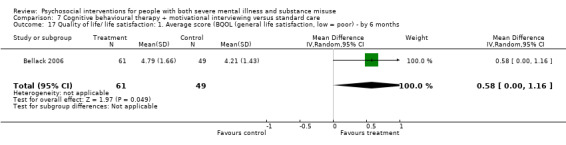

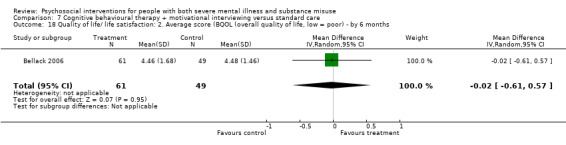

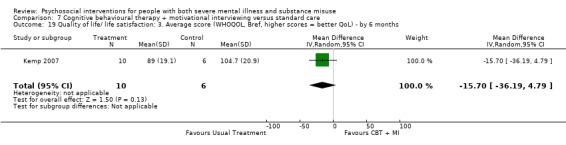

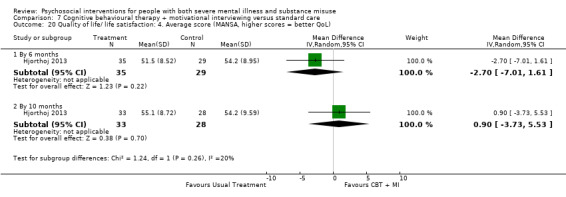

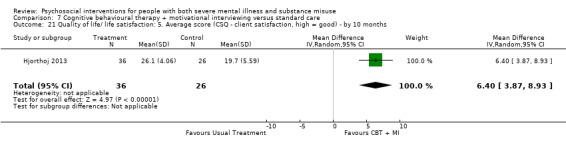

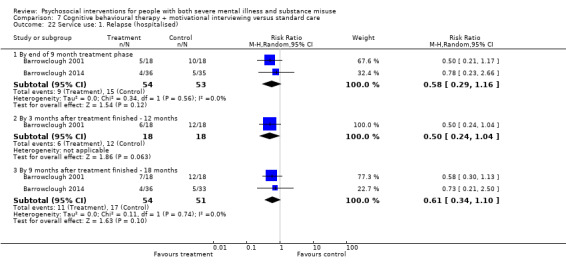

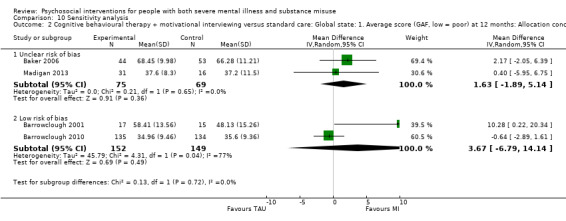

7. CBT + MI versus standard care

At 12 months, there was no clear difference between treatment groups for numbers lost to treatment (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.59; participants = 327; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence), number of deaths (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.76; participants = 603; studies = 4; low‐quality evidence), relapse (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.04; participants = 36; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence), or GAF scores (MD 1.24, 95% CI ‐1.86 to 4.34; participants = 445; studies = 4; very low‐quality evidence). There was also no clear difference in reduction of drug use by six months (MD 0.19, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.60; participants = 119; studies = 1; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We included 41 RCTs but were unable to use much data for analyses. There is currently no high‐quality evidence to support any one psychosocial treatment over standard care for important outcomes such as remaining in treatment, reduction in substance use or improving mental or global state in people with serious mental illnesses and substance misuse. Furthermore, methodological difficulties exist which hinder pooling and interpreting results. Further high‐quality trials are required which address these concerns and improve the evidence in this important area.

Plain language summary

Psychosocial interventions for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse.

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review is to find out if psychosocial interventions aimed at reducing substance abuse in people with a serious mental illness improve patient outcomes compared to standard care. Researchers in the Cochrane collected and analysed all relevant studies that randomly allocated people with severe mental illness and substance misuse to a psychosocial treatment or standard care to answer this question and found 41 relevant studies.

Key message

From these 41 studies we did not find any high‐quality evidence to support any one psychosocial intervention over standard care. However, the differences in study designs made comparisons between studies problematic.

What was studied in the review?

“Dual” diagnosis is the term used to describe people who have a mental health problem and also have problems with drugs or alcohol. In some areas, over 50% of all those with a serious mental illness (these include schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and major depression) will have problems with drugs or alcohol that have negative and damaging effects on the illness symptoms and the way their medication works. People who have substance misuse problems can be treated via a variety of psychosocial interventions. These include motivational interviewing, or MI, that looks at people’s motivation for change; cognitive behavioural therapy, or CBT, which helps people adapt their behaviour by improving coping strategies; contingency management which rewards patients to abstain from taking substances, psycho‐education for patients and their carers or family, group and individual skills training. Other interventions include provider‐oriented long‐term interventions unifying services to provide integrated treatment so patients do not have to negotiate separate mental health and substance abuse treatment programmes. Integrated care is often linked to assertive community treatment (ACT) for patients with a dual diagnosis. There are a variety of psychosocial interventions that can be added to routine care and these can be provided individually or in various combinations. Currently, we do not know if any psychosocial treatment is better or worse than standard care or if they work better given in combination or individually.

What are the main results of the review?

The review found 41 relevant studies with a total of 4024 people. These studies looked at a variety of different psychosocial interventions (including CBT, MI, skills training, integrated models of care and contingency management) and compared them to standard care (the care a participant in the trial would normally receive). Main results showed there was:

1. no real difference in terms of numbers lost to treatment (low‐quality evidence);

2. no real difference in terms of death (low‐quality evidence);

3. no real difference in alcohol or substance used (low‐quality evidence);

4. no real difference in global functioning or general life satisfaction (low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence).

In addition, studies had high numbers of people leaving early, differences in outcomes measured, and differing ways in which psychosocial interventions were delivered. More large‐scale, high‐quality and better reported studies are required to address these shortcomings. This will better address whether psychosocial interventions are effective for people with serious mental illness and substance misuse problems.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to October 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Substance misuse among people with a severe mental illness is a major concern, with prevalence rates over 50%. This figure varies across studies, depending on location, methodologies and by the way substance misuse problems and severe mental illness are defined (Brunette 2018; Carra 2009; Green 2007; Gregg 2007; Hartz 2014; Lai 2012a; Lai 2012b; Lowe 2004; Morgan 2017; Regier 1990; Todd 2004). Recent meta‐analyses have shown high rates of co‐morbidity between substance use disorders (SUD) and schizophrenia (Hunt 2018), bipolar disorders (Hunt 2016) and major depression (Lai 2015). Improving services for people with a serious mental illness (often labelled as having a 'dual diagnosis') is a priority as using drugs or consuming alcohol, even at low levels, is associated with a range of adverse consequences, including higher rates of non‐adherence, relapse, suicide, HIV, hepatitis, homelessness, aggression, incarceration, and fewer social supports or financial resources (Donald 2005; Green 2007; Hunt 2002; Khokhar 2018; Pettersen 2014; Schmidt 2011; Tsuang 2006). Further, co‐morbidity places an additional burden on families, psychiatric and government resources and is particularly challenging to those providing services as these patients have lower rates of treatment completion and higher rates of relapse (Khokhar 2018; Mueser 2013; Siegfried 1998; Tyrer 2004; Warren 2007).

Description of the intervention

It is important that co‐occurring substance use is detected as early as possible and that appropriate and effective treatment is provided (Green 2007; Mueser 2013). Treatment has traditionally been complicated by different approaches and philosophies among mental health and drug services as they may differ in their theoretical underpinnings, policies and protocols. Separate treatment programmes have been offered in parallel or sequentially by different clinicians, which may result in less than optimum patient care with the patient having to negotiate two separate treatment systems (De Witte 2014; Drake 2008; Green 2007). Another approach to care is the integrated treatment model where mental health and substance use treatments are brought together simultaneously by the same service, clinician or team of clinicians who are competent in both service areas and place similar importance on both (Drake 2004). Basic elements include an assertive style of engagement, techniques of close monitoring, comprehensive services (including inpatient, day hospital, community team and outpatient care), supportive living environments, flexibility and specialisation of clinicians, step‐wise treatment, and a long‐term perspective and optimism (Bond 2015; Drake 1993; Drake 2008). Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) and residential programmes are generally long term and can form a basis for integrated programmes (Mueser 2013).

How the intervention might work

As many substance users in the general population have benefited from a range of psychosocial interventions, it would follow that these same interventions should also benefit people with psychosis when their mental health problems are taken into account (Barrowclough 2006a). Most, if not all, substances of abuse increase dopaminergic activity in the brain (Koob 2010). Given that schizophrenia and other forms of psychosis are characterised by heightened dopaminergic transmission and that neuroleptics decrease activity or block dopamine receptors (Kapur 2005), it stands to reason that most substances of abuse increase symptoms, the risk of relapse and compromise the beneficial effects of neuroleptics (Khokhar 2018; Large 2014; LeDuc 1995; Seibyl 1993). This is especially true for stimulant drugs like amphetamine, cocaine and concentrated forms such as crack cocaine and methamphetamine ('ice') that can exacerbate or mimic psychotic symptoms and elevate risk of readmission (Callaghan 2012; Lappin 2016; McKetin 2013; Pluddemann 2013; Romer Thomsen 2018; Sara 2015). Substance use is also related to poor adherence with treatment, further increasing the risk of relapse (Hunt 2002). Interventions that reduce substance use are likely to improve symptoms, relapse rates, recovery and other outcomes (Cleary 2009a; Drake 2008; Horsfall 2009). Common psychosocial interventions to reduce substance use and misuse include Twelve‐Step recovery, which adopts a supportive approach such as that used by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA); motivational interviewing, which aims to increase an individual's motivation for change; group and individual skills training; family psycho‐education regarding the signs and effects of substance use; and individual or group psychotherapy involving cognitive or behavioural principles, or both, which aim to increase coping strategies, awareness and self‐monitoring behaviour (Mueser 2013). All of these interventions can vary in intensity and duration, and can be offered in a variety of settings, either individually or as part of an integrated programme. Integrated treatment ensures mental health and substance misuse services are available in the same setting and delivered in a coherent fashion.

Why it is important to do this review

While encouraging, results of trials assessing the effectiveness of these psychosocial interventions for mental health consumers are equivocal (for reviews, see: Bennett 2017; Bogenschutz 2006; Cleary 2009a; De Witte 2014; Dixon 2010; Drake 1998b; Drake 2004; Drake 2008; Horsfall 2009; Ley 2000; Mueser 2005; Mueser 2013; NICE 2011). Many studies have been hampered by small heterogeneous samples, poor experimental design (for example non‐random assignment), high attrition rates, short follow‐up periods, lack of accuracy of measuring substance use, skewed data, use of non‐standardised outcome measures and unclear descriptions of treatment components (Barrowclough 2006a; Cleary 2008; Hunt 2013). When assessing integrated programmes, it can also be difficult to determine exactly which part of the programme is the most effective, and control groups (particularly in the USA) may involve a certain level of service integration, making interpretations difficult (Drake 1996). Moreover, study methodologies, interventions and outcome measures vary across studies, as do patterns of participants' readiness to change, severity and type of illness and substance use, all of which make combining results in a review problematic (De Witte 2014; Donald 2005; Drake 2008).

This current review updates the 2013 Cochrane Review on "Psychosocial treatment programmes for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse". The previous review (Hunt 2013) included any programme of substance misuse treatment and located 32 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The authors from three previous reviews found no evidence to support any one substance misuse programme as being superior to another (Cleary 2008; Hunt 2013; Ley 2000). We felt an update of this review was warranted as there are several new studies that have been conducted in the last five years.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions for reduction in substance use by people with a serious mental illness compared with standard care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with or without blinding if they utilised a psychosocial intervention to reduce substance use in people with severe mental illness and substance misuse compared with standard care. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those where allocation was alternate or sequential.

Types of participants

We included people diagnosed with a severe mental illness (for example, mixed patient populations with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression and other psychosis) and concurrent problem of substance misuse. We have defined people with 'severe' illness as those with a chronic mental illness like schizophrenia who present to adult services for long‐term care. Those with an organic disorder, non‐severe mental illness (for example, personality disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms based on scores from a scale) or those who solely abused tobacco were, if possible, excluded. Trials that included a mixture of patients with a severe mental illness diagnosis were included if a large proportion had a schizophrenia‐like illness or psychosis (see Characteristics of included studies). Studies were excluded if all of the participants had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder from 2013 on, so they do not overlap with affective disorder reviews.

Types of interventions

We anticipated that studies included in the review would use a wide variety of psychosocial interventions for substance misuse, making direct comparisons difficult. In order to enhance the utility of the review, we developed a priori categories within which we made planned comparisons. These categories were developed from theoretical models of the types of behavioural and psychosocial interventions offered to clients and the context in which they are delivered. The types of interventions were grouped in two strata, based on duration and intensity of treatment. The first stratum describes long‐term interventions for dual diagnosis patients that offered an array of services with different levels of integration and assertive outreach (taking place over years rather than weeks or months), and the second describes stand‐alone psychosocial interventions that clients received over shorter periods. We did not include interventions for informal carers (partner or family members) as separate categories, though we did sometimes include them as part of the treatments mentioned below.

1. Provider‐oriented long‐term interventions: integrated and non‐integrated care by community mental health teams for dual diagnosis populations

1.1 Integrated models of care with assertive community treatment (ACT)

Integrated treatment models for patients with a dual diagnosis unify services at the provider level rather than forcing clients to negotiate separate mental health and substance abuse treatment programmes (Drake 1993; Drake 2008; Mueser 2013). The range of services provided varies according to client needs and should be able to handle patients at differing stages of readiness to change (Tsuang 2006). Substance abuse treatments are integrated into an array of direct services, such as frequent home visits, crisis intervention, housing skills training, vocational rehabilitation, medication monitoring, and family psycho‐education. Integrated treatment means that the same clinicians or teams of clinicians in the one setting provide long‐term treatments in a co‐ordinated fashion (Barrowclough 2006a; Green 2007). Teams consist of three to six clinicians and attempt to remain faithful to a specified model of care. To the client, the services should appear seamless with a consistent approach, philosophy and set of recommendations. Usually the caseloads of dual diagnosis teams are lower (approximately 10 to 15 clients shared within a team) than for standard case managers (approximately 20 to 30). Integrated treatment is a process that takes place over years rather than weeks or months. Studies included in this category must have clearly demonstrated the following: 1) assertive community outreach to engage and retain clients and to offer services to reluctant or uncooperative clients, 2) staged interventions to reduce substance use, and 3) adherence to the integrated team philosophy. The intervention could be community‐based or provided for special populations, such as homeless people or forensic patients.

1.2 Non‐integrated models of care (ACTO) or intensive case management

Non‐integrated treatment entails similar interventions by community teams, as described above, except the same members do not deliver them in a co‐ordinated fashion and assertive community outreach is not included. Normally, case managers in this category are better trained and have higher clinical qualifications and better therapeutic skills than standard case managers. Intensive case management is defined as lower case load size (approximately 10 to 15 clients) than for standard case managers and tends to have a 'psychodynamic' flavour (see Marshall 1998; Mueser 2013). To be included in this category, part of the intervention had to address the client's drug and alcohol misuse.

2. Patient or client focused short‐term interventions for substance misuse

These interventions can be broadly grouped into individual and group modalities. They are offered in addition to routine care (treatment as usual, standard case management) and are based on different theoretical models. Although they could be part of the provider‐oriented packages described above, studies included here were easier to evaluate since they described a simplified intervention that can be easily reproduced. As some studies used more than one intervention (for example, cognitive behavioural therapy combined with motivational interviewing), these were included in a separate category.

2.1 Individual approaches

2.1.1 Cognitive behavioural therapies

Cognitive behavioural approaches include a variety of interventions (Rector 2012; Work Group 2007). The defining features are: 1) emphasis on functional analysis of drug use, understanding the reasons for use and consequences; and 2) skills training for recognising the situations where a person is most vulnerable to drug use and avoiding these situations. A cognitive behavioural intervention seeks to establish links between drug misuse, irrational beliefs, and misperceptions at a personal level and endeavours to correct the thoughts, feelings and actions of the recipient with respect to and the promotion of alternative ways of coping (Jones 2004; Jones 2012; Thoma 2015). The target symptom that is usually focused on is reducing problematic substance use or harm minimisation, such as reducing the risk of contracting HIV.

2.1.2 Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing takes a non‐confrontational approach to treating substance misuse and is intended to enhance the individual's intrinsic motivation for change, in patients who often find it difficult to commit to change (Tsuang 2006). It matches the patient's level of problem recognition to change with specific strategies and goals and can be delivered in brief sessions or over a number of weeks. It is based on four key principles: 1) expressing empathy, 2) developing discrepancy, 3) supporting self‐efficacy, and 4) rolling with resistance (Chanut 2005); and is directed at five stages: 1) pre‐contemplation, 2) contemplation, 3) preparation, 4) action, and 5) maintenance (Tsuang 2006). A key hypothesis is that the patient's perspective on the importance of change is fundamental to the patient's readiness to address the problem. Developing the patient's confidence in their ability to achieve the desired change is also a key issue of motivational interviewing. This treatment is delivered individually or in small group settings.

2.1.3 Contingency management

Based on principals of operant conditioning, contingency management (CM) offers incentives or rewards to reinforce specific goals (reduced substance use, risky behaviours etc). Typically, rewards are provided if a negative substance test is provided (urine test or breath test). Rewards can vary widely, ranging from encouraging statements ('keep up the good work') to large or small financial prize (vouchers for food, cash etc). This approach has shown consistent success with various drug use disorders: cannabis, opiate and cocaine dependence and polysubstance use disorders (Dutra 2008). Contingency management has also been added with other psychosocial interventions, for example, motivational interviewing plus cognitive behavioural therapies (Bellack 2006). Thus, contingency management was added to the previous review due to the number of current and ongoing trials using this intervention.

2.2 Group approaches

2.2.1 Social skills training

These groups are aimed at helping clients develop interpersonal skills for establishing and maintaining relationships with others, dealing with conflict, and handling social situations involving substance misuse (Mueser 2004; Mueser 2013). They are taught in a highly structured way by using role play, corrective feedback and homework. This usually occurs in a group format, although the methods can also be employed in individual work as a type of cognitive behavioural counselling.

3. Standard care

For this review, standard care or 'treatment as usual' or 'routine' care was defined as the care that a person would normally receive had they not been included in the research trial. This could include standard case management (e.g. see Dieterich 2017Mas‐Esposito 2015). Standard care varies between settings and can be supplemented by additional components, including psycho‐educational material, family therapy, or referral to self‐help groups (for example, Alcoholics Anonymous) or other agencies for substance abuse treatment.

Types of outcome measures

We intended to group data into short‐, medium‐ and long‐term outcomes. However, this would have resulted in much data loss as outcome periods varied and therefore, we reported for the following time periods: 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months (where applicable).

We endeavoured to report binary outcomes, recording clear and clinically meaningful degrees of change (e.g. global impression of much improved, or more than 50% improvement on a rating scale ‐ as defined within the trials) before any others. Thereafter we listed other binary outcomes and then those that are continuous*.

We only extracted data from valid scales (see Data collection and analysis).

For outcomes measured and scales used by included studies see (Included studies).

Primary outcomes

1. Leaving the study early

1.1 Lost to treatment: this is a measure of stability and engagement (number of participants who did not continue with the treatment following randomisation; however, some may have provided data for the study. This varies with study design as some treatments are ongoing for the study duration and some are short term. When studies reported exactly the same data for both lost to treatment and lost to evaluation (see below), and if there were no other studies with which to pool data, then we only reported the numbers lost to treatment (to reduce the number of comparison tables). We did not adjust numbers lost to treatment for death (see below).

2. Substance use: changes in substance use (alcohol or drugs, or both) as defined by each of the studies

2.1 Clinically important change or any change in substance use 2.2 Average endpoint or change score on substance use scale

3. Mental state (mental health symptoms)

3.1 Clinically important change or any change in mental state 3.2 Average endpoint or change score on mental state scale

Secondary outcomes

1. Leaving the study early

1.1 Lost to evaluation (number of people lost to the study who did not provide data at particular time points). 1.1.1. For any reason 1.1.2 For specific reason

2. Adverse events

2.1 Death (all causes)

Some studies may not have reported on the number of participants dying over the treatment or evaluation period. If reported, we recorded death in a separate table, but these cases were retained in the lost to treatment and lost to evaluation figures as it is often unclear when the death occurred or the cause of death was not stated as unlikely to be linked to the intervention.

3. Global state (a clinical measure of patient's psychological, social and occupational functioning in a single measure)

3.1 Clinically important change or any change in global state 3.2 Average endpoint or change score on global state scale

4. Social functioning (social assessment measures and basic skills necessary for community living)

4.1 Clinically important change or any change in social functioning 4.2 Average endpoint or change score on quality of life/life satisfaction scale

5. Quality of life/life satisfaction (objective and subjective quality of life satisfaction measures, measures of global patient satisfaction with daily living and services provided)

5.1 Clinically important change or any change in quality of life/life satisfaction 5.2 Average endpoint or change score on quality of life/life satisfaction scale

6. Service use (including relapse)

Relapse is often used as an outcome measure. Relapse can be measured as a dichotomous event (re‐admitted to hospital), or continuous measure such as number of admissions over a specified period or time to admission (number of weeks, days).

6.1 Re‐admission to hospital 6.2 Number of admissions 6.3 Number of days in community

7. Homelessness: homelessness is common in this patient population. It is often used to measure a favourable outcome if a person finds stable living accomodation over a specified period

7.1 Number of days in stable living accomodation 7.2 Number of days on street

8. Economic outcomes

8.1 Direct costs: e.g. costs to the patient for supplying a drug‐free urine sample 8.2 Indirect costs: e.g. savings based on number of days living in the community, versus costs of inpatient treatment or days in jail

9. Compliance with treatment and medication (as defined by individual studies)

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011); and used GRADEpro GDT to export data from our review to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rate as important to patient care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Leaving the study early: numbers lost to treatment (medium term: 12 months; if these data were not available we used the short‐term data).

Adverse event: death.

Substance use: alcohol use (as measured in the trials). Described as a clinically important reduction in alcohol use.

Substance use: drug use (as measured in the trials). Described as a clinically important reduction in illicit drug use.

Mental state: (as measured in the trials, and if no specific scale assessment was done we reported on relapse or hospitalisation).

Global state: (as measured in the trials) described as a clinically important change in functioning.

Quality of life ‐ life satisfaction: (as measured in the trials) described as a clinically important change in satisfaction.

If data were not available for these pre‐specified outcomes but were available for ones that were similar, we presented the closest outcome to the pre‐specified one in the table but took this into account when grading the finding*.

* see Differences between protocol and review Note 5.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 2 May 2018, the Information Specialist searched the register using the following search strategy:

(*{PSY}* in Intervention) AND (*Substance Use* in Healthcare Condition) of STUDY

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics (Shokraneh 2017).

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (AMED, BIOSIS, CENTRAL, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.Gov, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, WHO ICTRP) and their monthly updates, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I and its quarterly update, Chinese databases (CBM, CNKI, and Wanfang) and their annual updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group's website). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

For previous searches, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference lists

We searched all references of articles selected for inclusion, major review articles (Baker 2012; Bennett 2017; De Witte 2014; Dixon 2010; Drake 2008; Dutra 2008; Galletly 2016; Horsfall 2009; Kelly 2012), as well as recent guidelines (NICE 2011; Hasan 2015) on this topic for further relevant trials.

2. Journal databases

Further searches were completed (September 2018) by the principal review author (GEH) using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (daily update, PREMEDLINE), and PsycINFO. A separate search for randomised trials using contingency management was completed as this was an additional intervention category for the previous update. We also searched MEDLINE for recent articles (2013 to 2018) by the first authors of all included studies in order to get a more complete list of recent publications.

We also did 'forward' searches to identify trials that cited previously included RCTs using Web of Science and Scopus. Scopus was used to identify trials that cited the most recent versions of this review (Cleary 2008, Hunt 2013) up to October 2018.

3. Trials registries

In addition, web sites and journals that list ongoing trials in the USA, UK, Australia and various European countries were searched for RCTs through the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register. The principal review author (GEH) searched www.clinicaltrials.gov for protocols of current and previously included studies for proposed outcome measures to assess selective reporting bias.

4. Personal contact

We contacted the first author (or corresponding author) of newly included studies for this update regarding their knowledge of ongoing or unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Methods for data collection and analysis methods employed for the 2018 search are below. For data collection and analysis methods in earlier versions see Appendix 2 and Appendix 4.

Selection of studies

Review authors GEH and MC inspected all citations from the new electronic search and identified relevant abstracts, full‐text articles and trials against the inclusion criteria. To ensure reliability, KM inspected all full‐text articles for inclusion. Where there were uncertainties or disagreements, two additional review authors provided resolution (NS and CB‐S). Where disputes could not be resolved, these studies remained as awaiting assessment or ongoing studies and we contacted the authors for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

GEH and KM extracted data from the included studies. We resolved disputes by discussion and adjudication from the other review authors (NS and MC) when necessary. If it was not possible to extract data or if further information was needed, we attempted to contact the authors. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but the data were included only if two review authors independently had the same result. When further information was necessary, we contacted authors of studies in order to obtain missing data or for clarification of methods.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b) the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; c) the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning and not sub‐scores which are not, in themselves, validated or shown to be reliable. However there are exceptions, we included sub‐scores from mental state scales measuring positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Ideally the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, we noted in Description of studies if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis as we preferred to use mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Deeks 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to relevant data before inclusion.

Please note, we entered data from studies of at least 200 participants in the analysis, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We also entered all relevant change data as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not.

For endpoint data from studies < 200 participants:

(a) when a scale starts from zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value was lower than 1, it strongly suggests a skew and we excluded these data. If this ratio was higher than one but below 2, there is suggestion of skew. We entered these data and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion change the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio was larger than 2 we included these data, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

(b) if a scale starts from a positive value such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), which can have values from 30 to 210, we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

2.5 Common measure

Where relevant, to facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we converted continuous outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this can be considered as a clinically important response (Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the psychosocial intervention. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved'), we presented data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome and noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors (GEH, NS, CB‐S) independently assessed risk of bias within the included studies by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011a). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus with all review authors. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies contacted in order to obtain further information. If non‐concurrence occurred, we reported this.

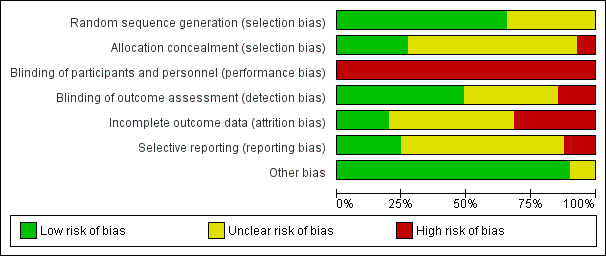

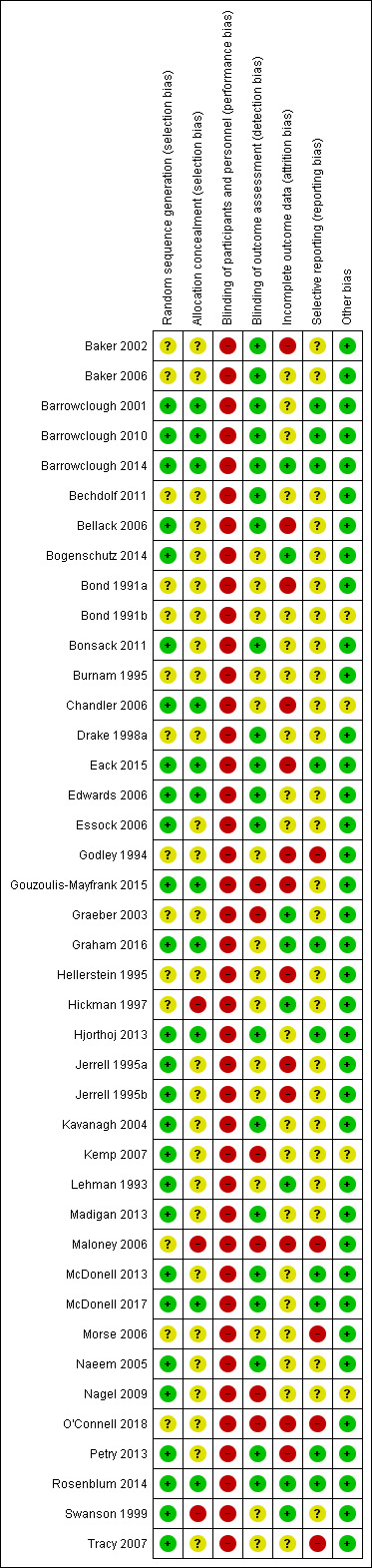

We noted the level of risk of bias in the text of the review and in Figure 1; Figure 2 and 'Summary of findings' tables.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios as odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference SMD). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

None of the presently included trials used cluster randomisation. For the purposes of future updates of this review, where clustering is not accounted for in primary studies we planned to present data in a table with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review, should we include cluster‐RCTs, we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we plan to present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study but adjust for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC (design effect = 1 + (m ‐ 1)*ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported we will assume it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If we had identified cluster trials, we would have analysed them taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report. Synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

None of the presently included studies employed a cross‐over trial design. For the purposes of future updates of the review, a major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (for example, pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we proposed to only use the data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary we simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we combined data following the formula in Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not use data where the additional treatment arms were not relevant.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by down‐rating quality. We also planned to downgrade quality within the 'Summary of findings' tables should loss be 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome is between 0% and 50% and where these data are not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). We assumed all those leaving the study early to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed ‐ except for the outcomes of death and adverse effects ‐ for these outcomes we used the rate of those who stayed in the study (in that particular arm of the trial) for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change by comparing data only from people who completed the study to that point to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

We reported and used data where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either 'P' value or 't' value available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). The Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, we preferred to use the more sophisticated approaches. (e.g. MMRM or multiple‐imputation) and only presented completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we addressed this issue in the item "incomplete outcome data" of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we fully discussed these.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on: i) magnitude and direction of effects, and ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (for example, P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for the heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Chapter 10. of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011).

1. Protocol versus full study

We tried to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies are of similar size. In future versions of this review, if funnel plots are possible, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies, even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose the random‐effects model for main analyses (see also Sensitivity analysis)

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses ‐ only primary outcomes

1.1 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of psychosocial interventions for people with schizophrenia and other psychoses, in general. In addition, however, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we have reported this. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successively removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur, with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present the data. If not, then we did not pool the data and discussed the issues. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off, but we use prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We do not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses on outcomes of comparisons with four or more trials where studies with different quality were combined to ascertain if there were substantial differences in the results when lesser quality trials or those comprising participants with schizophrenia (or other psychoses) were compared to trials of higher quality or using mixed diagnostic groups. We applied all sensitivity analyses to the primary outcomes based on randomised sequence, allocation concealment and blinding of outcome measurement. We only conducted sensitivity analyses on comparisons with four or more studies as analyses with less than four trials would provide unclear decisions on whether there have been any possible biases in the estimate of effects.

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way so as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with a better description of randomisation then we entered all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumptions and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we reported the results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing sSD data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumptions and when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to test how prone results were to change when completer‐only data were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcomes. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

A sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials was not carried out as there are no cluster‐randomised trials included in the review.

5. Fixed‐ and random‐effects

We synthesised data using a random‐effects model; however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcomes using fixed‐effect method to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results.

If we noted substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome but presented them separately.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

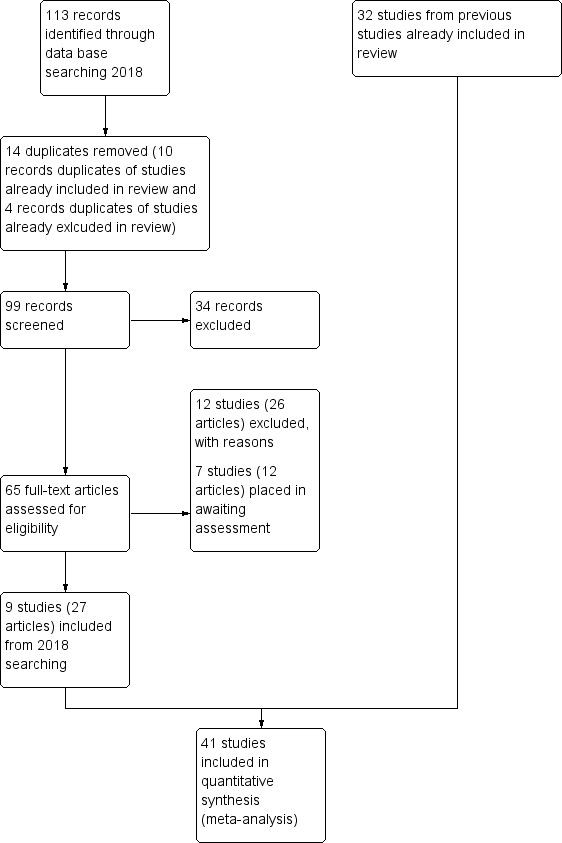

A total of 4866 citations were found using the search strategy devised for the original version of this review. The inclusion of the word 'drug' in the search strategy produced a vast number of irrelevant references. For the current update 113 additional relevant records were scrutinised which resulted in an additional nine studies considered for inclusion (Barrowclough 2014; Bogenschutz 2014; Eack 2015; Gouzoulis‐Mayfrank 2015; Graham 2016; McDonell 2017; O'Connell 2018; Petry 2013; Rosenblum 2014). Together with the 32 studies from previous reviews, the current review included 41 studies. See also Figure 3.

3.

Study flow diagram for 2018 search

Included studies

In the previous review (Hunt 2013), 32 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were selected for inclusion. Three studies (Godley 1994; Maloney 2006; Morse 2006) from the first update (Cleary 2008) contained only skewed data (shown as 'other data' within the Data and analyses). The remaining trials provided usable data (either dichotomous or continuous parametric data). For the current update, nine new trials were selected for inclusion thus in total, 41 RCTs were included in the current review.

1. Design

Three trials were set exclusively in hospital (Baker 2002; Bechdolf 2011; Swanson 1999) and 26 in the community. Ten trials recruited patients or were conducted in both the community (outpatients) and in hospital (Bellack 2006; Bonsack 2011; Gouzoulis‐Mayfrank 2015; Graeber 2003; Graham 2016; Hellerstein 1995; Hjorthoj 2013; Kavanagh 2004; Madigan 2013; Naeem 2005), and two were set in the community and in jail (Chandler 2006; Maloney 2006).

Most studies randomly allocated participants to one of two treatment conditions; the exceptions were Barrowclough 2014; Burnam 1995; Jerrell 1995a; Jerrell 1995b; Maloney 2006; Morse 2006 and O'Connell 2018). These trials randomly allocated participants to one of three or four (Maloney 2006) interventions. We have used only two of the intervention arms in Burnam 1995 as the other did not fit into any a priori category described for inclusion in this review. Data are shown in additional tables. Study durations ranged from three months to three years and the length of the interventions ranged from less than one hour to three years. There were 25 trials from the USA, six from Australia, five from the UK, two from Germany and one each from Denmark, Ireland and Switzerland.

2. Participants

A total of 4024 people participated in the trials after giving informed consent and were randomised into one of the treatment arms. All participants were adults (aged 18 to 65 years) who were 'severely mentally ill' with the majority having a diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis (affective and non‐affective). All had a current diagnosis of substance use disorder or had documented evidence of substance misuse. Some were homeless or had a history of unstable accommodation (Burnam 1995; Essock 2006; Morse 2006; Tracy 2007), and some were incarcerated at the time of the study (Chandler 2006; Maloney 2006).

3. Interventions

Integrated models of care (four RCTs).

Non‐integrated models of care (four RCTs).

Combined cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing (nine RCTs).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (two RCTs).

Motivational interviewing (nine RCTs).

Skills training (six RCTs).

Contingency management (four RCTs).

4. Outcomes

Where possible, we included dichotomous data relating to loss to treatment, loss to evaluation, death, abstinence or reduced substance use, relapse, attendance at aftercare, and arrests.

All of the outcome scales and their abbreviations are listed in Table 10, together with the reference of the source of the scale. See below for descriptions of the continuous data scales that reported data used in the analyses. For a full list of the scales mentioned in each of the studies see Characteristics of included studies.

1. List of scales and abbreviations used in included studies.

| Name of tool | Abbreviation | Source of scale ‐ reference |

| Diagnostic tools | ||

| Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition | DSM‐IV | DSM‐IV |

| The classification of mental and behavioural disorders | ICD‐10 | ICD‐10 |

| Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis | SCID | Spitzer 1990 |

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), computerised scoring for DSM‐III‐R criteria | C‐DIS‐R | DSM III‐R |

| Substance use scales | ||

| Addiction Severity Index | ASI | McLellan 1980; McLellan 1992 |

| Alcohol Use Inventory | AUI | Horn 1987 |

| Alcohol Use Scale | AUS | Mueser 1995 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test | AUDIT | Saunders 1993 |

| Brief Drinker Profile | BDP | Miller 1987 |

| Drug and Alcohol Problem Scale | DAPS | adapted non‐peer reviewed version of this scale used; see Bond 1991a |

| Drug Use Scale | DUS | Mueser 1995 |

| Opiate Treatment Index | OTI | Darke 1991 |

| Change Questionnaire‐Cannabis | RTCQ‐C | Rollnick 1992 |

| Substance Abuse Treatment Scale | SATS | McHugo 1995 |

| Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry | SCAN | Wing 1990 |

| Substance Use Severity Scale | USS | Carey 1996 |

| Mental state scales | ||

| Addiction Severity Index (psychiatric subscale) | ASI | McLellan 1980 |

| Beck Depression Inventory ‐ Short Form | BDI‐SF, BDI‐11 | Beck 1972 |

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | BPRS | Lukoff 1986 |

| Brief Scale for Anxiety | BSA | Tyrer 1984 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory | BSI | Derogatis 1983a |

| Calgary Depression Scale | CDS | Addington 1992 |

| Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale | CPRS | Asberg 1978 |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | HAM ‐ D | Hamilton 1960 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depresion Scale | HADS | Zigmond 1983 |

| Insight Scale | David 1992 | |

| Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale | MADRS | Montgomery 1979 |

| Positive & Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia | PANNS | Kay 1987 |

| Psychiatric Epidemiologic Research Interview | PERI | Dohrenwend 1980 |

| Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms | SANS | Andreasen 1982 |

| Scale for the assessment of Positive Symptoms | SAPS | Norman 1996 |

| Symptom Checklist 90 | SCL‐90 | Derogatis 1973; Derogatis 1975 |

| Symptom Checklist 90‐revised | SCL‐90‐R | Derogatis 1983b |

| Schizophrenia Change Scale | SCR | Montgomery 1978 |

| Young Mania Rating Scale | YMRS | Young 1978 |

| General function scales | ||

| Global Assessment of Functioning | GAF | DSM‐IV |

| Health of the Nation Outcome Scale | HoNOS | Wing 1996 |

| Role Functioning Scale | RFS | Green 1987 |

| Social Adjustment Scale for the Severely Mentally Ill | SAS‐SMI | Wieduwilt 1999 |

| Social Functioning Scale | SFS | Birchwood 1990 |

| The Social and Occupational Functioning Scale | SOFAS | Goldman 1992 |

| Quality of life scales | ||

| Brief Quality of Life Scale | BQOL | Lehman 1995 |

| Life Satisfaction Checklist | LSC | Bond 1988; Bond 1990 |

| Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life | MANSA | Priebe 1999 |

| Quality of Life Interview | QOLI | Lehman 1988 |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | SLS | Stein 1980 |

| World Health Organization's Quality of Life assessment scale, short version | WHOQOL‐BREF | Skevington 2004 |

| Other | ||

| Client Satisfaction Questionnaire | CSQ | Larsen 1979 |

| Medication Adherence Rating Scale | MARS | Thompson 2000 |

| The Service Utilization Rating Scale | SURS | Mihalopoulos 1999 |

4.1 Substance use scales

a. Drug and alcohol scales from Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

The ASI (McLellan 1980) provides two summary scores of problems of functioning in seven areas, including psychiatric problems, and those concerning drug and alcohol use. Severity ratings range from zero to nine and are assessments of lifetime and current problem severity derived by the interviewer. Composite scores are mathematically derived and are based on client responses to a set of items based on the last 30 days. Although difficulties have been reported concerning the use of the ASI with people who have severe mental illness (Corse 1995), the psychometric properties of the subscales with this population have been reported by a number of authors (Appleby 1997; Hodgins 1992; Zanis 1997). Given that the problems encountered by the scale are likely to be encountered by any other similar instrument based on self‐reports of those with severe and persistent mental illness, it was decided to include data obtained with the ASI (used in Barrowclough 2001; Bechdolf 2011; Bellack 2006; Drake 1998a; Eack 2015; Essock 2006; Hellerstein 1995 and Lehman 1993).

b. Alcohol Use Inventory (AUI)

This inventory assesses alcohol use (Horn 1987) (used by Hickman 1997).

c. Alcohol Use Scale (AUS)

A five‐point scale based on clinicians' ratings of severity of disorder, ranging from one (abstinence) to five (severe dependence) (Mueser 1995). This was used in Drake 1998a and Essock 2006.

d. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The AUDIT is a 10‐item questionnaire covering the domains of alcohol consumption, drinking behaviour and alcohol‐related problems (Saunders 1993). Responses to each question are scored from zero to 4. A sum score of 8 or more indicates hazardous or harmful alcohol use. This was used in Graham 2016.

e. Cannabis and Substance Use Assessment Schedule (CASUAS) (modified from the SCAN)

This measures cannabis use and includes similar information to the ASI, such as percentage of days using cannabis in the past four weeks, frequency of cannabis use, and an index of severity (range zero to 4) with higher scores indicating greater severity (Wing 1990) (used by Edwards 2006).

f. Drug Use Scale (DUS)

A five‐point scale based on clinicians' ratings of severity of disorder, ranging from one (abstinence) to five (severe dependence) (Mueser 1995) (used in Drake 1998a and Essock 2006).

g. Opiate Treatment Index (OTI)

The OTI has six domains reflecting treatment outcomes of: drug use, HIV risk‐taking behaviour, social functioning, criminality, health status and psychological adjustment (Darke 1991; Darke 1992). The drug use domain consists of 11 items measuring drug use over the last three days (recent drug use) or previous month (28 days) for alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates and other drugs. Clients are asked to estimate the number of drinks or usage of drugs on the two most recent use days in the previous month. The quantity over the two days (q1 + q2) is divided by day interval (t1 + t2). Thus, an OTI score of 1.0 indicates one drink, injection or joint per day; 0.14 to 0.99 more than once a week; 0.01 to 0.13 once a week or less, and 2.0 or more indicates use more than once a day. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of dysfunction or substance use. Baker 2002 and Baker 2006 used the OTI to measure substance use over the previous month.

h. Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS)

An eight‐point scale indicating progression toward recovery ranging from one (early stages of engagement) to eight (relapse prevention). Higher scores indicate greater progression (McHugo 1995). This was used by Drake 1998a, Essock 2006 and Graham 2016.

i. Alcohol and drug use disorders section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐III‐R (Patient Edition) (SCID)

Items relate to substance use in the past month (Spitzer 1990). Higher scores indicate a greater degree of dysfunction (used by Baker 2002).

j. Substance Use Severity Scale (USS)

This is a five‐point scale, ranging from one (not using) to five (meets criteria for severe use) (Carey 1996), used by Morse 2006.

4.2 Mental state assessment

a. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

This contains 21 self‐report items which measure the severity of depression (Beck 1972). Each item comprises four statements (rated from zer to 4) describing increasing severity on how they felt over the preceding week. Scores range from zero to 84, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms (used in Baker 2006; Edwards 2006 used the short form of this scale (BDI‐SF)).

b. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

Used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms (Lukoff 1986), the scale has 24 items, of which 14 are based on the person's self‐report in the last two weeks and 10 on the person's behaviour during the interview. Each item can be defined on a seven‐point scale from one (not present) to seven (extremely severe). Total scoring ranges from 24 to 168 and there are five subscales with minimum scores ranging from three to four depending on the subscale (used in Baker 2006; Drake 1998a; Eack 2015; Edwards 2006; and Essock 2006).

c. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

This measures psychiatric symptomatology (Derogatis 1983a). A brief rating scale is used by an independent rater to assess severity of psychiatric symptoms. Scores range from zero to 4 with higher scores indicating more symptoms (used by Baker 2002, Bogenschutz 2014, McDonell 2013, McDonell 2017 and Petry 2013).

d. Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (CPRS)

This is an interview rating scale covering a wide range of psychiatric symptoms, and can be used in total or as subscales. The Montgomery Asperg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Brief Scale for Anxiety (BSA) and the Schizophrenia Change Scale (SCR) are all subscales of the CPRS. It comprises 65 items that cover the range of psychopathology over the preceding week (40 symptom items are rated by the participant) (Asberg 1978). Each item is rated on a zero to 3 scale, varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', with high scores indicating more severe symptoms and a worse outcome (used by Naeem 2005).

Global state: (a clinical measure of patient's psychological, social and occupational functioning in a single measure)

e. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

The Global Assessment of Functioning is a revised version of the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (Endicott 1976). The (GAF) scale allows the clinical progress of the patient to be expressed in global terms using a single measure. The GAF allows the clinician to express the patient's psychological, social and occupational functioning on a continuum extending from superior mental health, with optimal social and occupational performance, to profound mental impairment when social and occupational functioning is precluded. Developed by DSM‐IV to report global assessment of functioning on the Axis V (DSM‐IV), it ranges from 1 to 100 (zero is used to acknowledge inadequate information). Higher scores indicate a better outcome; scores ranging from 1 to 20 indicate a person unable to function independently; 21 to 40 indicate major impairment, severely impaired by delusions; 41 to 60 moderately impaired, having serious symptoms and these patients usually need continuous treatment in a partial hospitalisation or outpatient setting; 61 to 80 indicate slight or mild impairment with transient symptoms; and 81 to 100, good or superior functioning. Baker 2006, Barrowclough 2001, Barrowclough 2010, Barrowclough 2014, Bechdolf 2011, Bonsack 2011, Essock 2006, Gouzoulis‐Mayfrank 2015 and Madigan 2013 used this scale.

f. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS is a 14‐item self‐assessment scale developed to detect states of depression and anxiety (Zigmond 1983). Each of the items is rated on a four‐point Likert scale (zero to 3) with half of the items rated on a reverse scale (I feel cheerful, I can sit at ease and feel relaxed). Scale scores can be categorised into non‐cases (scores of zero to 7), doubtful cases (8 to 10) and definite cases (>11) for depression (HADS‐D) and anxiety (HADS‐A) (used by Graham 2016).

g. Health of the Outcome Nation Outcomes Scale (HoNOS)

HoNOS is a 12‐item instrument on a scale of zero to 4 used to rate patients' symptoms and progress towards health (Wing 1996). Item 3 can be used to rate drug and alcohol use (zero = no problem, 1 = some over‐indulgence but within social norm, 2 = loss of control, 3 = marked craving, 4 = incapacitated by alcohol or drug problem) and other items can be used to assess social functioning. Thus, ratings range from zero to 48 and higher scores indicate a poorer outcome (used by Naeem 2005).

h. Insight Scale

This is used to assess the patient's level of insight about their illness (David 1992). Seven self‐report items are scored from zero = no insight to 2 = full insight. One additional self‐report item is scored zero to 4 (used by Graham 2016 and Naeem 2005).

i. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The PANSS was developed from the BPRS and the Psychopathology Rating Scale (Kay 1987). It is used as a method for evaluating positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. The scale has 30 items and each item can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system, varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme), so total scores range from 30 to 210. This scale can be divided into three subscales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology (range 16 to 112), positive symptoms (PANSS‐P, range 7 to 49) and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N, range 7 to 49). A low score indicates low levels of symptoms. This was used by Barrowclough 2001, Barrowclough 2010, Barrowclough 2014, Bechdolf 2011, Bonsack 2011, Gouzoulis‐Mayfrank 2015, Kemp 2007, McDonell 2017 and O'Connell 2018.

j. Psychiatric scale from Addiction Severity Index (ASI‐psychiatric)

Psychiatric subscores (McLellan 1980) were reported in Lehman 1993 and Hellerstein 1995. See the ASI scoring above.

k. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

The scale assesses negative symptoms for schizophrenia (Andreasen 1982). This assesses five symptoms complexes to obtain the clinical rating of negative symptoms over the preceding week. They are affective blunting, alogia, apathy, anhedonia and disturbance of attention. Each item uses a six‐point scale ranging from zero (not at all) to 5 (indicating severe). High scores indicate a worse outcome (used by Edwards 2006).

l. Symptom Checklist 90 (revised) (SCL‐90‐R)

Used to measure psychiatric symptoms (Derogatis 1983b), the scale has 90 self‐report items designed to measure nine symptom dimensions. Each item has a five‐point Likert scale ranging from zero (mild or not at all) to 4 (severe or extremely distressing), with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology (used by Hickman 1997).

4.3 Quality of life and client satisfaction; quality of life scales measure objective and subjective quality of life satisfaction and global patient satisfaction with daily living and services provided (see Results, section 4.3).

a. The Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) and the Brief Quality of Life Scale (BQOL)

The QOLI contains 153 items that measure global life satisfaction as well as objective and subjective quality of life (Lehman 1988; Lehman 1995). It has eight domains (for example, living situations, daily activities and functioning, family relations, social relations). Rated on a seven‐point scale (1 = terrible, 2 = unhappy, 3 = mostly dissatisfied, 4 = equally satisfied and dissatisfied, 5 = mostly satisfied, 6 = pleased, and 7 = delighted), with higher scores indicating better quality of life. It was used by Baker 2006, Bellack 2006, Drake 1998a, Essock 2006 and Lehman 1993.

b. World Health Organization's Quality of Life scale (WHOQOL‐BREF)