Abstract

Objectives: To clarify clinically challenging palpebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and to propose a novel therapeutic modality, we developed a multi-disciplinary approach for the management of AVMs with ulcer.

Approach: First, the central retinal artery was secured with embolization by the transophthalmic arterial, a terminal branch of the internal carotid artery (ICA), and then, the branches of the external carotid artery (ECA) were embolized to cause a response in the AVM vasculature followed by sclerotherapy and surgery.

Results: Over a 3-year follow-up of palpebral and periorbital AVMs in four females and one male 20 to 50 years of age with a mean age of 38 years, complete remission of the lesions were seen with no major complication, such as blindness, ptosis, or cerebral infarction, with functionally sound and esthetically acceptable results, with no recurrence or worsening even with one case of ulceration postembolization.

Innovation: Planned treatment of palpebral and periorbital AVMs, which have been often left untreated because of their complex vasculature and a risk of total blindness due to occlusion of the central retinal artery. A “wait-and-watch” approach is frequently taken.

It is important to secure the periphery to the bifurcation of the central retinal artery of the ICA, and then, embolization through the ECA results in complete remission of the lesion, followed by sclerotherapy and surgery, which are successful both in terms of function and esthetics.

Conclusion: First, securing the central retinal artery leads to safer and complete resolution of palpebral and periorbital AVMs; wounding or therapeutic complications such as skin necrosis may be seen, but this approach results in complete remission in 3 years with no major complications.

Keywords: central retinal artery, transophthalmic arterial embolization, external carotid artery, following sclerotherapy and surgery, Schobinger staging, angiographic diagram

Sadanori Akita, MD, PhD.

Introduction

Clinically, Congenital arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are categorized using Schobinger staging. Stage I is quiescence with long-term stability, and stage II is expansion followed by rapid expansion, pulsation, thrill, bruit, and tense vessels. Stage III is destruction with pain, hemorrhage, skin ulcer, tissue necrosis, and osteolysis; and stage IV is decompensation when greater AVMs with high flow lead to volume and pressure overload in circulation, leading to heart failure.1–3 Complete surgical resection of AVMs is rarely possible, except when they are small and localized in a surgically accessible area. In management in terms of Schobinger staging, even stage I progresses over 40% before adolescence and over 80% before adulthood. The probability of AVM recurrence is significantly greater with embolization alone than with resection with or without embolization in all stages, and time to recurrence is significantly shorter with embolization alone. Embolization alone was found to result in >85% recurrence within 1 year in 272 patients at a single institute over a 28-year period.4

Imaging is vital for characterizing AVMs and following treatment strategy. High-flow and fast-flow AVMs have remarkably different findings from low-flow and slow-flow vascular malformations. On MRI, AVMs appear as a complex network of dilated vessels of arteries and veins connected by linear or focal shunting. These vessel nests demonstrate flow voids on T1- and T2-weighted spin echo imaging5 and appear as hyperintense signals on T2-weighted gradient echo imaging and angiography, suggesting fast flow through the lesion. Unlike other vascular malformations, AVMs demonstrate no augmentation of adjacent soft tissue on T2-weighted imaging, except when significant edema is present.6

Aggressive treatment consisting of intra-arterial embolization combined with surgical excision is indicated to offer the best chance for cure and maximal control, but complete excision is not often possible due to the location and extent of the lesion. Complex lesions require multiple and meticulous operations, focused on individual pathology and anatomy. Embolization techniques include the use of metal coils, particles, and glue (e.g., N-butyl cyanoacrylate [NBCA]). When embolization alone is adopted, lesions, necrosis, muscle contracture, or permanent nerve paralysis may occur in the extremities, and amputation may eventually be required postoperatively.7,8

The origin and cause of superficial AVMs such as those in eyelids are unclear. Symptoms of mass, pulsation, visual blurring, thrill, discoloration, tightened sensation, and frequent ulceration necessitate treatment of eyelid AVMs, which require careful anatomical consideration to secure the central retinal arteries, and rerouting both internal and external carotid arteries (ECAs) by arterial embolization.9 Somatic MAP2K1 mutations are reported to be associated with extracranial AVMs based on whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome sequencing,10 and RAS/MAPK pathways, including KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and MAP2K1 variants, are more common in sporadic high-flow vascular malformations than in low-flow ones; malformations with the above variants respond to targeted therapy.11

To ensure safety and prevent central retinal artery occlusion, we first embolized the distal branch after bifurcation of the central retinal artery from the ophthalmic artery. This method also requires very meticulous and fine microcatheter procedures; angiographic analysis demonstrated filling of the eyelid arcades, and unpredicted occlusion of the central retinal artery can be avoided because the anastomoses between the internal and external carotid branches were well preserved. Thus, there are blunt surgical or radiological approaches from sites of the branches of the ECA.12 Therefore, permanently blocking the ophthalmic artery distal to bifurcation of the central retinal artery is pivotal in treating periorbital and eyelid AVMs before embolization, sclerotherapy, surgery, or a combination thereof.

Clinical Problem Addressed

High-volume blood flow or fast-flow AVMs are often challenging to treat and control. Clinical symptoms determined by Schobinger include warmth and discoloration in stage I, enlargement, pulsation, thrill, bruit, and twisting veins in stage II, skin dystrophy, ulcer, hemorrhage, and pain in stage III, and cardiac failure in stage IV. They can expand and often become exacerbated with time and very rarely result in regression or involution as they do in infantile hemangioma.

Treatment at earlier stages is desirable; however, once an inappropriate treatment is performed, the residual and collateral lesions may be worsened both hemodynamically and clinically. Moreover, blunt treatment in the periorbital and eyelid AVMs may cause serious complications such as blepharoptosis, ulcer, blindness, or even damage to intracranial tissues, such as the brain through the internal carotid artery (ICA). Therefore, to ensure safety, procedures to avoid occlusion of the central retinal artery, which is one of the branches of the ophthalmic artery by the ICA, should precede any therapeutic modalities. Once the central retinal artery bifurcation of the ophthalmic artery from the ICA is rerouted and secured, subsequent treatment can result in lesser comorbidity. Thus, the proposed method is highly recommended to treat periorbital and eyelid AVMs.

Patients and Methods

This clinical study was conducted in Nagasaki University Hospital, Japan, from September 1, 2013, to August 31, 2016, and continued in Fukuoka University Hospital, Japan, from September 1, 2016, to August 31, 2018. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after individual explanations of the study by the two authors, S.A. and H.I. All interventional radiologic procedures, including embolization, were performed by H.I. and S.Y., while all sclerotherapies and surgeries were performed by S.A. The follow-up periods represent the last treatment.

All embolization, sclerotherapy, and surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia and there was an interval of 2 days between embolization and sclerotherapy or surgery.

Results

Two cases have been previously embolized through the ECA. One of the patients experienced counting finger visual acuity and oculomotor nerve paralysis, because the reverse flow from the ECA occluded the central retinal artery and possible damage to the ICA to the posterior communicating artery was suspected by other physicians. The other patient, with type II cheek destructing AVMs, was treated by us by direct puncture of the shunting. None of our procedures resulted in major complications, including visual impairment, brain infarction, or other functional loss of the face. One patient experienced partial upper eyelid and temporal skin necrosis due to excessive interventional radiological occlusion from the branches of the ECA; however, levator oculi muscle function was retained and was covered with anterior auricle skin grafting. There was no cerebral infarction, loss of visual acuity, or ptosis due to our procedures.

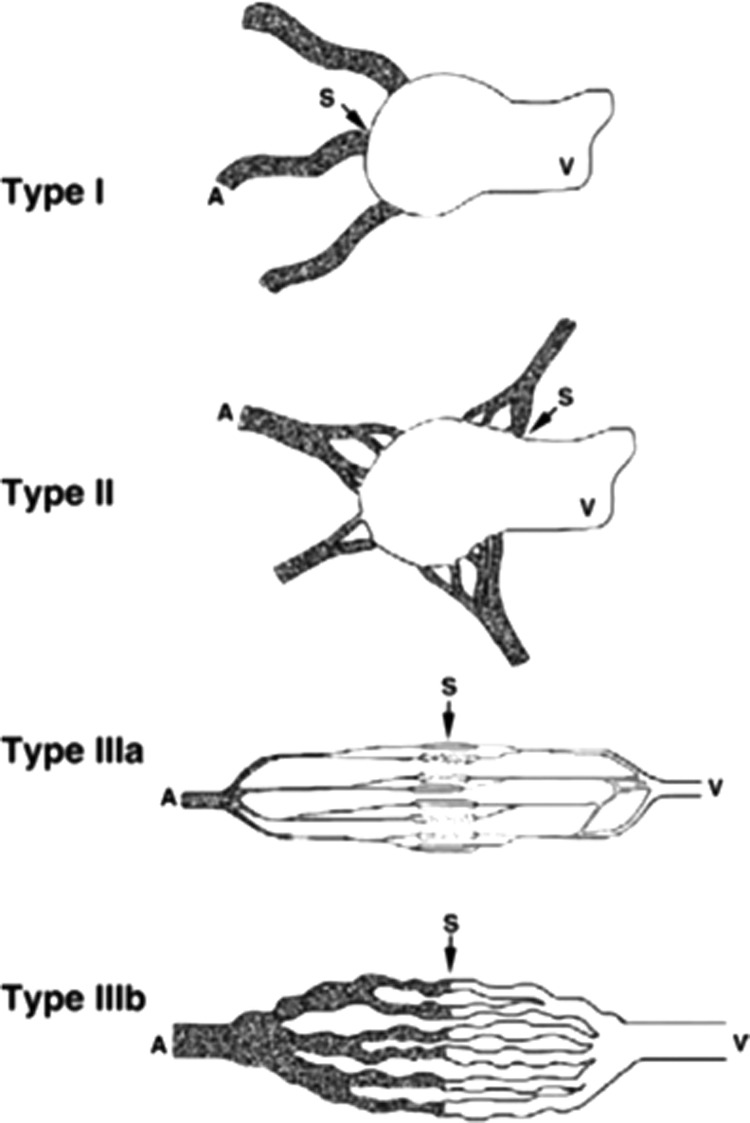

Nearly complete embolization of the lesion was achieved by intraophthalmic arterial occlusion periphery to the central retinal artery, which secured the reverse back flow by the subsequent external carotid arterial embolization, which was then followed by sclerotherapy or surgery 48 h after embolization. NBCA was used for the procedure in one patient with previous visual impairment and the other procedures were performed using coils. In terms of angiographic classification, two cases were diagnosed as type IIIa, which is an AVM with multiple nondilated fine arteriolovenulous fistulas and three cases were diagnosed as type IIIb, which is an AVM with multiple hypertrophied and dilated arteriovenulous fistulas that appear as a multiple and complex vascular network.13 In terms of approach and occlusion of the branches of the ECA, three cases of type IIIb were treated with NBCA, while two cases of type IIIa were with superabsorbent polymer microsphere beads (Fig. 1). When large AVMs were present in the upper eyelids, there were visual field aberrations, especially in upper gaze and masses, pulsations, thrills, and bruits were commonly seen in all such cases; pain and eyelid skin discoloration were observed among all three types as preoperative symptoms. The cases were followed up for more than 3 years with a mean period of 3.2 years (3 to 3.5 years), and the symptoms were found to subside with no recurrence (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

A diagram of the four types of AVMs based on nidus morphology. Type I (arteriovenous fistulae) AVMs: no more than three separate arteries shunt to the initial part of a single venous component. Type II (arteriolovenous fistulae): multiple arterioles shunt to the initial part of a single venous component, in which the arterial components show a plexiform appearance on angiography. Type IIIa (arteriolovenulous fistulae with nondilated fistula): fine multiple shunts are present between arterioles and venules and appear as a blush or fine striation on angiography. Type IIIb (arteriolovenulous fistulae with dilated fistula): multiple shunts are present between arterioles and venules and appear as a complex vascular network on angiography. In types IIIa and IIIb, multiple venulous components of the fistula unit collect to a draining vein.13 A, arterial compartment of the fistula unit; AVM, arteriovenous malformations; S, shunt; V, venous compartment of the fistula unit.

Figure 2.

A 20-year-old female with Schobinger stage II and angiographic IIIa in the left upper eyelid with mass and upper gaze visual field impairment. (A) Frontal view. Bulging in the lateral left upper eyelid with pulsation, thrill, and bruit. (B) Lateral view. Left eyelid bulging is prominent. (C) Angiographic and coil embolization. Both ICA and ECA demonstrate vasculature, and after securing the periphery to the bifurcation of the ophthalmic artery with coils, as demonstrated by a red arrow, ECA branches were embolized with superabsorbent polymer microsphere beads. There is no vascular tree in the upper eyelids postembolization. (D) Frontal view. At 48 h postembolization, the mass was nearly completely removed and was not observed in 3.2 years. (E) Lateral view. The mass subsided in 3.2 years. ECA, external carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery. Color images are available online.

Figure 3.

A 40-year-old female with Schobinger stage III and angiographic IIIb in the left upper eyelid with mass and upper gaze visual field impairment. (A) Frontal view. Bulging in the left upper eyelid with pulsation, thrill, and bruit, and skin discoloration. (B) Lateral view. Left eyelid bulging is prominent. (C) Angiographic and coil embolization. Both ophthalmic artery and ECA demonstrate vasculature and after securing the periphery to the bifurcation of the ophthalmic artery with coils, ECA branches were embolized with 25% NBCA, as demonstrated by a blue arrow. There is no vascular tree in the upper eyelids postembolization or most of the branches of ECA near the eyelid subsided. (D) Frontal view. At 48 h postembolization, the lateral upper eyelid and temporal skin were necrotized. (E) Surgical removal of the necrotic tissue; the levator muscle and conjunctiva were preserved. (F) Frontal view. After debridement of necrotic tissue, preauricular skin grafting was performed and was stabilized in 3 years. (G) Lateral view. After debridement and preauricular skin grafting, in 3 years, the bulging mass and symptoms disappeared. NCBA, N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Color images are available online.

Discussion

Early Schobinger staging of extracranial AVMs of stage I and II with bleomycin was found to be safe and effective in males over 20 months of postoperative follow-up.14 AVMs may necessitate early-stage treatment; they are likely to progress before adulthood, particularly during adolescence, and usually reexpand following treatment. Resection (with or without embolization) for early stages or localized AVMs provides the best chance for long-term control.4 The natural course of AVMs can be progressive, invasive, and destructive; attentive observation, early treatment, and radical therapy are necessary to treat AVMs.15

Current treatment for AVMs is not standardized. Surgery plays a limited role because radical resections often cause deformity or dysfunction, or because partial resection is linked to worsening or recurrence.4 In embolization, NBCA can cause recanalization and can be a focus of infection, thus removal is desirable16; therefore, embolization with or without sclerotherapy and surgery are the mainstay,17,18 even though intralesional injection of bleomycin was found to result in good outcomes in a pilot study.14 Inappropriate treatment may stimulate AVM exacerbation; therefore, selective endovascular embolization and subsequent surgical treatment are likely to result in good esthetic and functional results.19 In 23 high-flow cases of 54 facial AVMs during a 10-year-period, 21.7% were classified as stage I Schobinger, 47.9% as stage II, and 30.4% as stage III, with all requiring surgical resections following embolization.20 In facial AVMs, palpebral AVMs are rare and only less than 0.5% of orbital vascular tumors are palpebral AVMs.21 Eyelids and periorbital AVMs play an integral part in blood supply and AVMs. Eight out of nine cases were reported to be fed by the ICA such as palpebral branches of the ophthalmic artery, with only one case being fed by branches from the ECA and six cases out of nine being fed by both the ICA and ECA; furthermore, to avoid central retinal occlusion after angiography, embolization was also not performed.9 ICA angioplasty and stenting or coil embolization of paraclinoid aneurysms were found to cause branch retinal artery occlusion and visual acuity impairment.22,23 This complex vascular network might lead to severe complications in ICA branches, and it is therefore very rarely reported in the literature involving palpebral or periorbital AVM treatment.

Preprocedural angiographic findings demonstrate certain vascular territories, but the perfusion territory is often altered after intervention; thus, careful attention should be paid while embolizing the eyelid or periorbital AVMs.24 In our regimen, except one case of previous occlusion, all cases involved the use of coils to prevent reverse flow, debris, or thrombus and guarantee high rate of complete primary occlusion.25 In the orbit, six branches of the ICA, supratrochlear, supraorbital, dorsal nasal, lachrymal, anterior, and posterior ethmoidal arteries, are freely anastomosed with branches of the ECA, while the central retinal artery is the terminal branch; therefore, it is reasonable to block the periphery of the central artery with coils to prevent debris or reverse flows due to embolization by the ECA.26

Diffuse AVMs and dilated angiographic morphology of IIIb make it more challenging to obtain complete remission compared to nondilated type IIIa, regardless of embolization agents.14 However, NBCA functioned well in two of three IIIb cases and superabsorbent polymer microsphere beads were quite effective in IIIa through selective ECA branches.

Postembolization bulging, foreign material due to NBCA, and excessive tissue were corrected by surgical reconstruction and in one case of IIIb, the central retinal was secured by skin grafting. Palpebral AVMs may demonstrate skin changes and ulcer by progression of lesion stage, and may also present complications of post-treatment necrosis and ulcer.

Palpebral and periorbital AVMs were successfully treated by securing the ICA branch with coils and the NBCA periphery to the central retinal artery followed by embolization through ECA routes.

Innovation

Treatment of palpebral AVMs has been avoided because of the complex vasculature in this region and to avoid the risk of total blindness due to occlusion of the central retinal artery. When the central retinal artery is occluded, permanent blindness occurs and reverse high flow, debris, or thrombus may pass through the ICA and cause ptosis or cerebral infarction.

To treat palpebral AVMs, it is important to secure the periphery to the bifurcation of the central retinal artery of the ICA; then, embolization through the ECA results in complete remission of the lesion, followed by successful sclerotherapy and surgery in terms of both function and esthetics. The wait-and-watch approach may worsen the stage and result in development of intractable ulcers, making treatment more challenging.

More detailed procedures of transophthalmic arterial embolization will be presented and discussed in another interventional radiology publication.

Key Findings.

In the treatment of complex and high-flow palpebral AVMs, which may damage the central retinal artery, initial embolization of the periphery to the bifurcation of the ophthalmic artery is essential to prevent major complications of blindness, ptosis, or cerebral infraction.

Second, the branches of the ECA are to be embolized using glue or beads, depending on the angiographic type of the AVM.

Proper treatment of palpebral AVMs causes complete remission of the lesion and subsequent surgery can be safely performed without major complications, even when tissue necrosis occurs due to ECA embolization.

Palpebral AVMs do not need to be subject to the wait-and-watch approach, but can be aggressively treated.

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AVM

arteriovenous malformations

- ECA

external carotid artery

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- NBCA

N-butyl cyanoacrylate

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

There are no competing financial interests. The content of this article was explicitly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Hideki Ishimaru, MD, PhD, is a board-certified interventional radiologist and an assistant professor in Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University, and performed all the cases in this manuscript as a primary interventionist. Satomi Yoshimi, MD, is an interventional radiologist for all the cases in this manuscript and currently a graduate school student of Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University. Sadanori Akita, MD, PhD, is a board-certified plastic surgeon and primarily planned the treatment at Nagasaki University where his previous workplace was located, wrote the manuscript as a correspondence and is currently a chief professor in Department of Plastic Surgery, Wound Repair, School of Medicine, Fukuoka University since 2016.

References

- 1. Kohout MP, Hansen M, Pribaz JJ, Mulliken JB. Arteriovenous malformations of the head and neck: natural history and management. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:643–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Enjolras O, Logeart I, Gelbert F, et al. Arteriovenous malformations: a study of 200 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2000;127:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elluru RG, Azizkhan RG. Cervicofacial vascular anomalies. II. Vascular malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu AS, Mulliken JB, Zurakowski D, Fishman SJ, Greene AK. Extracranial arteriovenous malformations: natural progression and recurrence after treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:1185–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cahill AM, Nijs EL. Pediatric vascular malformations: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and the role of interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011;34:691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Navarro OM, Laffan EE, Ngan BY. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudo-tumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: part 1. Imaging approach, pseudotumors, vascular lesions, and adipocytic tumors. Radiographics 2009;29:887–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holt PD, Burrows PE. Interventional radiology in the treatment of vascular lesions. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2001;9:585–599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoon KW, Heo SH, Hyun D, Park KB, Do YS, Kim DI. Compartment syndrome after embolization of arteriovenous malformation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017;40:1950–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarençon F, Blanc R, Lin CJ, et al. Combined endovascular and surgical approach for the treatment of palpebral arteriovenous malformations: experience of a single center. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:148–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Couto JA, Huang AY, Konczyk DJ, et al. Somatic MAP2K1 mutations are associated with extracranial arteriovenous malformation. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:546–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Olabi L, Polubothu S, Dowsett K, et al. Mosaic RAS/MAPK variants cause sporadic vascular malformations which respond to targeted therapy. J Clin Invest 2018;128:1496–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vasilic D, Barker JH, Blagg R, Whitaker I, Kon M, Gossman MD. Facial transplantation: an anatomic and surgical analysis of the periorbital functional unit. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cho SK, Do YS, Shin SW, et al. Arteriovenous malformations of the body and extremities: analysis of therapeutic outcomes and approaches according to a modified angiographic classification. J Endovasc Ther 2006;13:527–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin Y, Zou Y, Hua C, et al. Treatment of early-stage extracranial arteriovenous malformations with intralesional interstitial bleomycin injection: a pilot study. Radiology 2018;287:194–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richter GT, Suen JY. Clinical course of arteriovenous malformations of the head and neck: a case series. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;142:184–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rao VR, Mandalam KR, Gupta AK, Kumar S, Joseph S. Dissolution of isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate on long-term follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1989;10:135–141 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee BB, Do YS, Yakes W, Kim DI, Mattassi R, Hyon WS. Management of arteriovenous malformations: a multidisciplinary approach. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:590–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee BB, Baumgartner I, Berlien HP, et al. Consensus document of the international union of angiology (IUA)-2013. Current concept on the management of arterio-venous management. Int Angiol 2013;32:9–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. López Gutiérrez JC, Ros Z, Martínez L, et al. High flow vascular malformations in children. Cir Pediatr 2002;15:145–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pompa V, Brauner E, Bresadola L, Di Carlo S, Valentini V, Pompa G. Treatment of facial vascular malformations with embolisation and surgical resection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012;16:407–413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wright JE. Orbital vascular anomalies. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1974;78:OP606–OP616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karth PA, Siddiqui S, Garbett D, Stepien KE. Branch retinal artery occlusion after internal carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2013;7:402–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choudhry N, Brucker AJ. Branch retinal artery occlusion after coil embolization of a paraclinoid aneurysm. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2014;45 Online:e26–e28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Helle M, Rüfer S, van Osch MJ, et al. Superselective arterial spin labeling applied for flow territory mapping in various cerebrovascular diseases. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013;38:496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yasumoto T, Yakushiji H, Ohira R, Ochi S, Nakata S, Hirabuki N. Superselective coaxial microballoon-occluded coil embolization for vascular disorders: a preliminary report. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015;26:1018–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agure AMR, Lee MJ, eds. Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999 [Google Scholar]