Abstract

Background:

Bleeding gums are one of the common complaints to visit a dentist. Mechanical removal of plaque alone is not sufficient for the reduction of gingival inflammation associated with plaque. Mouthwashes are supplemented to it as a homecare product. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of 0.2% sodium hypochlorite mouthwash on plaque and gingival inflammation and to assess the clinical parameters of gingivitis patients from baseline to 21 days with the use of 0.2% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwashes.

Materials and Methods:

This clinical trial study included 60 patients with gingival inflammation evaluated using clinical parameters such as bleeding on probing index, plaque index, and gingival index at baseline and 21 days. Group A patients were given Hi Wash mouthwash and Group B 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash with 30 patients in each group.

Results:

The scores for clinical parameters were significantly reduced after 21 days in Group A and Group B patients, and there was a reduction in plaque-associated gingival inflammation without scaling and root planning.

Conclusions:

0.2% sodium hypochlorite mouthwash is as effective as 0.2% chlorhexidine for the treatment of gingivitis as it is an adjunct to mechanical plaque removal in terms of safety, less side effects, less staining and can be used as a routine mouthwash.

Keywords: 0. 2% sodium hypochlorite, 0.2% chlorhexidine, gingivitis

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is the biofilm that adheres to the intraoral hard surfaces. It consists of microorganisms, their products, food debris, and epithelial sheddings, which is primarily responsible for biofilm-induced gingivitis and dental caries. If left untreated, gingivitis may progress to periodontitis. Periodontitis may eventually lead to loss of tooth and further discomfort to the patient. To keep up a healthy periodontium, plaque removal is necessary, and there should be a resolution of gingival inflammation.[1] Scaling and root planning is the basic treatment modality for the debridement and reduction in microbial load of plaque biofilm. Various antiseptics and antimicrobials have been tried since ancient times as an adjunct to mechanical debridement. In most cases, gingival inflammation does not subside after mechanical debridement alone[2] and the microbial flora tends to invade the gingival sulcus and pockets soon after mechanical debridement.[3] To prevent this, antiseptic agents in different forms have been advised as an adjunctive therapy and is more effective. These agents can be used as local delivery,[4] mouthwashes, gels, etc.

Chlorhexidine mouthwash is an effective mouthwash against supragingival and subgingival flora.[5] It has both bacteriostatic and bactericidal property at low and high concentrations. It is considered as the gold standard for mouthwash, but it has some disadvantages such as tendency to stain teeth and intraoral restorations if used for long term, it may alter taste sensation, may impair healing as it has some toxicity for gingival fibroblasts[6,7] and to some lesser extent promotes calculus deposition although it has antiplaque effect.[8]

The sodium hypochlorite has been used for various purposes since ages. It is a well-known bleaching agent for clothes, effective for wound cleaning, and dilute form can be used for bath intermittently in atopic dermatitis.[9] It has broad antimicrobial activity.

In dentistry, 1%–5.25% as a root canal irrigant as it can dissolve organic matter in canal. It possesses some anticaries activity against the cariogenic bacteria within dentinal tubules and also by its antiplaque action.[10,11] Slot considered dilute form of NaOCl as one of the low-cost antiseptics for periodontal treatment, and he also suggested that it does not corrode intraoral hard surfaces such as teeth and titanium implants. NaOCl was substantive enough to remain for 24 h in the oral cavity.[11] In 1984, “The American Dental Association Council on Dental Therapeutics” assigned 0.1% sodium hypochlorite as “mild antiseptic mouthrinse,” which can be applied directly on oral mucous membranes.[12]

Sodium hypochlorite has a beneficial effect on dental plaque biofilm as well. Supragingival and subgingival plaque biofilm consists of periodontal pathogens embedded in a polysaccharide matrix, renders resistance to attack by antimicrobials through its hard structure preventing penetration and reach microorganism, also deeper layers have different concentration gradient and create an acidic environment preventing further attack.[13] In water, sodium hypochlorite is hydrolyzed into hypochlorous acid and hypochlorite ion. Hypochlorous acid and nascent oxygen are split products of hypochlorous acid having the potential for its action. Hypochlorous acid can diffuse through the cell wall of microorganism and alters its redox potential thereby reduces the capacity of plaque to produce an acidic environment; hence, plaque biofilm is altered or diluted and they no longer possess the capacity to produce gingivitis. Furthermore, it can shift anaerobic to aerobic flora, which is comparatively less pathogenic. It can reduce enzymatic activity, react with proteins, nucleic acid, and lipid molecule of microorganism.[11]

It does not cause toxicity for gingival fibroblasts, so no effect on periodontal healing, no staining, nontoxicity at recommended concentrations, and cost-effective. In humans, sodium hypochlorite is naturally occurring molecule in activated neutrophils, and hence macrophages show no allergic reaction.[14]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study was conducted in the department of periodontics from September to October 2018. This study included a total of 60 patients of both genders diagnosed with gingivitis selected on the statistical basis of pilot study's result with a power of 80% and allowable error of 5 % through convenient sampling. Study patients included must be >16 years of age, with at least 20 natural teeth, bleeding index >50%, and mild-to-moderate gingivitis. Exclusion criteria were the use of systemic or topical antibiotic therapy within 6 months before the study, pregnancy and lactation, presence of systemic diseases, such as diabetes, blood dyscrasias, human immunodeficiency virus-positive or AIDS, immunosuppressive drug therapy, or use of medications affecting gingival enlargement, should not possess any deleterious habit such as smoking >10 cigarettes a day, and failure to report. Patients were thoroughly explained about the method and principle of the study and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Study design

The patients were assigned into two groups – Group A and Group B with 30 patients in each group. Group A patients were given 0.2% sodium hypochlorite (Hi Wash) mouthwash and Group B patients were given 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash for 21 days. Clinical parameters such as bleeding on probing by gingival bleeding index (Ainamo and Bay), plaque index (Silness P and Loe H 1967), and gingival index (Loe H and Silness P 1963) were recorded at baseline and 21 days. Scaling and root planning was done after the trial period of 21 days. Both the groups were advised to use 10 ml mouthwash for 1 min twice daily and asked to avoid eating or brushing for ½ h. Each patient was taught the modified bass tooth brushing technic at the baseline.

Statistical analysis

The data were evaluated for variables tested on bleeding on probing, plaque reduction, and gingival inflammation. All the variables were tested between the two different types of mouthwash on the patients at baseline and 21st day. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for intragroup comparison at baseline and at 21st day, and Mann–Whitney U-test was applied for comparison between the two Groups A and B.

RESULTS

The mean plaque index, gingival index, and gingival bleeding index were recorded for two different types of mouthwash, namely, 0.2% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine. The mean values were obtained prior and 21 days post the use of the mouthwashes and results are enlisted in the tables below.

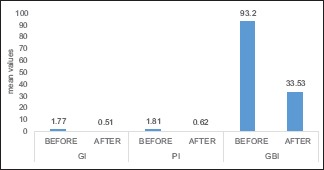

Table 1 depicts the comparison of clinical parameters before and after the use of Hi Wash mouthwash. From the statistical results, it was deduced that 0.2% aqueous solution of sodium hypochlorite containing 0.2% sodium hypochlorite mouthwash significantly decreased the amount of plaque, gingival inflammation, and gingival bleeding after the trial period of 21 days with the reduction of plaque index from 1.77 to 0.5. Gingival index was reduced to 1.81–0.62 and a notable difference in gingival bleeding from 93.2% to 33.53%. Mean of NaOCl mouthwash after 21 days is depicted in the Graph 1.

Table 1.

Plaque index, gingival index, and gingival bleeding index at baseline and after 21 days using 0.2% sodium hypochlorite mouthwash

| Parameter | Interval | Mean | SD | SEM | Mean rank | Z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | Before | 1.77 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 15.50 | −4.783 | 0.001** |

| After | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.02 | ||||

| GI | Before | 1.81 | 0.26 | 0.05 | −4.782 | 0.001** | |

| After | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.02 | ||||

| GBI | Before | 93.20 | 6.84 | 1.25 | −4.784 | 0.001** | |

| After | 33.53 | 6.56 | 1.2 |

Test applied: Wilcoxon signed-rank test; **P≤0.001 (highly significant). PI – Plaque index; GBI – Gingival bleeding index; GI – Gingival index; SD – Standard deviation; SEM – Standard error of mean; Z – Measurement of standard deviation; P – Probability value

Grpah 1.

The mean of 0.2% sodium hypochlorite before and after 21 days

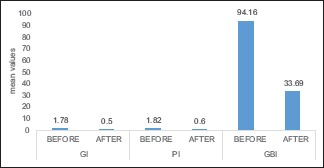

Table 2 reveals the effect of chlorhexidine on clinical parameters with a significant reduction. PI† was reduced to 0.50 from 1.78, and GI‡ was 0.60 after 21 days, and GBI§ was reduced to 33.69 from 94.16 suggesting its efficacy. Graph 2 shows the mean of chlorhexidine mouthwash after 21 days.

Table 2.

The plaque index, gingival index, and gingival bleeding index before and after the use of chlorhexidine at baseline and at 21st day

| Parameter | Interval | Mean | SD | SEM | Mean rank | Z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | Before | 1.77 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 15.50 | −4.783 | 0.001** |

| After | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.02 | ||||

| GI | Before | 1.81 | 0.26 | 0.05 | −4.782 | 0.001** | |

| After | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.02 | ||||

| GBI | Before | 93.20 | 6.84 | 1.25 | −4.784 | 0.001** | |

| After | 33.53 | 6.56 | 1.2 |

Test applied: Wilcoxon signed-rank test; **P≤0.001 (highly significant). PI – Plaque index; GBI – Gingival bleeding index; GI – Gingival index; SD – Standard deviation; SEM – Standard error of mean; Z – Measurement of standard deviation; P – Probability value

Grpah 2.

The mean of 0.2% chlorhexidine before and after 21 days

The intergroup statistical analysis comparing the decrease of PI†, GI‡, and GBI between Hi Wash and 0.2% chlorhexidine is shown in Table 3. The average results of both groups were found to be statistically nonsignificant (P > 0.05) suggesting nearly equal efficacy of both the mouthwashes. The clinical parameters and patient follow-up suggested use of 0.2% NaOCl was beneficial in plaque reduction, thereby prevent gingivitis. There were no side effects reported during or after its use apart from its bleach-like taste.

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of clinical parameters between 0.2% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash at baseline and after 21 days

| Variable | Interval | Group | Mean rank | Mann-Whitney U-value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | Before | Hi Wash | 30.20 | 441 | 0.894 |

| CHX | 30.80 | ||||

| After | Hi Wash | 31.33 | 425 | 0.710 | |

| CHX | 29.67 | ||||

| GI | Before | Hi Wash | 30.35 | 445 | 0.947 |

| CHX | 30.65 | ||||

| After | Hi Wash | 31.70 | 414 | 0.594 | |

| CHX | 29.30 | ||||

| GBI | Before | Hi Wash | 29.52 | 420.5 | 0.660 |

| CHX | 31.48 | ||||

| After | Hi Wash | 30.23 | 442 | 0.906 | |

| CHX | 30.77 |

PI – Plaque index; GBI – Gingival bleeding index; GI – Gingival index; CHX – Chlorhexidine; P – Probability value

DISCUSSION

Oral hygiene practices have been shown interest these days by the general population as a matter of fact that the people are more aware and considerate about their oral health. They try various cleaning aids including mouthwashes. It is a need of this hour to have a mouthwash that can be used on a routine basis with least side effects. 0.2% sodium hypochlorite has shown good results which suggest its use routinely. This mouthwash is a transparent liquid which is palatable with no numbness after its use, and it does not cause dryness as it is alcohol free.

In this clinical study, the use of 0.2% sodium hypochlorite was found to be efficacious, and it could resolve and maintain a healthy gingiva. Sodium hypochlorite (2%–5%) is used as an endodontic irrigant in dentistry which could even remove Enterococcus faecalis bacteria from root canals[13] and evidence support its association with periodontal microbiology, also it can dissolve the organic matter from the pulp chamber.[15] Studies have been done using sodium hypochlorite as mouthwash for gingivitis and periodontitis at different concentrations (0.05%–0.2%).[16]

The main mechanism of antimicrobial activity of NaOCl being its high pH which alters cell membrane of microorganism by irreversible inhibition of enzymes promoted by oxidation and replacement of hydrogen by chlorine ions damages the phospholipid of cell wall and modifies the metabolism of cellular biosynthesis by chloramination. It also alters the plaque composition.[17]

In 1972, Lobene used 0.5% sodium hypochlorite as one of the antiseptic solutions for subgingival irrigation in a water pressure irrigating device and water was taken as control. They selected upper canines and premolars of six college students and compared its efficacy on gingival scores. There was a 47% reduction in the gingival scores compared to water.[18,19]

Estrela et al., in 2003, compared the antimicrobial efficacy of both 2% sodium hypochlorite and 2% chlorhexidine digluconate using agar diffusion test and direct exposure test on Staphylococcus aureus, E. faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, and Candida albicans. They found that both had equally effective antimicrobial activity on the above-mentioned microorganism.[17]

There was a study conducted by De Nardo et al., in 2011, on 44 male prison inhabitants using 0.05% sodium hypochlorite and distill water as mouthrinse twice daily for 21 days on 20 participants each. They were held back from oral hygiene measures during the study. They were examined for gingival inflammation and found 56% reduction in bleeding on probing in the experimental group after 21 days.[20]

In a study by Galván et al., in 2014, in which there was a reduction in plaque and bleeding after 3 months in participants using 0.25% sodium hypochlorite as a twice weekly oral rinse for 3 months prepared from Clorox than water which was then used as a control.[21]

A review on NaOCl mouthrinse by Rich and Slots, in 2015, based on previous studies found its effectiveness against periodontal pathogens as a versatile antiseptic which is cost-effective and easily available.[22]

In 2016, Jurczyk et al. conducted an in vitro study to compare the activity of 0.95% sodium hypochlorite gel with 0.1% chlorhexidine digluconate solution on periodontopathogens. The minimal inhibitory concentrations of both were <10% in both the groups. NaOCl was the active component of the hypochlorite gel and was more effective against Gram-negative bacteria than chlorhexidine which was more effective against Gram-positive bacteria.[23]

In the above-discussed studies, it is clear that the sodium hypochlorite at different concentrations could reduce the plaque, destroy oral microorganisms, revert the inflammation of the gingiva, thereby maintaining a healthy periodontium. We have used 0.2% sodium hypochlorite as sodium hypochlorite in its dilute form is nontoxic.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of the results of the study, 0.2% sodium hypochlorite as a mouthwash is nearly effective as 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash for gingivitis. It can be used as an alternate to chlorhexidine-containing mouthwashes and as a regular mouthwash for its low cost and good patient compliance. No adverse reaction or harmful effect and staining were observed in the study participants during the study. The use of 0.2% sodium hypochlorite mouthwash further needs evaluation on large scale population with microbial sampling and long-term follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We hereby, acknowledge our gratitude to S. Goshal (Pansila “m” impact) and Alok Shukla for the provision of the mouthwash sample.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hellström MK, Ramberg P, Krok L, Lindhe J. The effect of supragingival plaque control on the subgingival microflora in human periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:934–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matesanz-Pérez P, García-Gargallo M, Figuero E, Bascones-Martínez A, Sanz M, Herrera D. A systematic review on the effects of local antimicrobials as adjuncts to subgingival debridement, compared with subgingival debridement alone, in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:227–41. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnusson I, Lindhe J, Yoneyama T, Liljenberg B. Recolonization of a subgingival microbiota following scaling in deep pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rams TE, Slots J. Local delivery of antimicrobial agents in the periodontal pocket. Periodontol 2000. 1996;10:139–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1996.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wade WG, Addy M. In vitro activity of a chlorhexidine-containing mouthwash against subgingival bacteria. J Periodontol. 1989;60:521–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.9.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flötra L, Gjermo P, Rölla G, Waerhaug J. Side effects of chlorhexidine mouth washes. Scand J Dent Res. 1971;79:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasanna SV, Lakshamanan R. Characteristics, uses and side effect of chlorhexidine: A review. J Dent Med Sci. 2016;15:57–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbrother KJ, Heasman PA. Anticalculus agents. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:285–301. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027005285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan C, Shaw RE, Cockerell CJ, Hand S, Ghali FE. Novel sodium hypochlorite cleanser shows clinical response and excellent acceptability in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:308–15. doi: 10.1111/pde.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Shen Y, Li W, Haapasalo M. Penetration of sodium hypochlorite into dentin. J Endod. 2010;36:793–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slots J. Low-cost periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:110–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Dental Association. Accepted Dental Therapeutics. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reyhani MF, Rezagholizadeh Y, Narimani MR, Rezagholizadeh L, Mazani M, Barhaghi MH, et al. Antibacterial effect of different concentrations of sodium hypochlorite on Enterococcus faecalis biofilms in root canals. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2017;11:215. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2017.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray MJ, Wholey WY, Jakob U. Bacterial responses to reactive chlorine species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:141–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102912-142520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abou-Rass M, Oglesby SW. The effects of temperature, concentration, and tissue type on the solvent ability of sodium hypochlorite. J Endod. 1981;7:376–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(81)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumgartner JC, Cuenin PR. Efficacy of several concentrations of sodium hypochlorite for root canal irrigation. J Endod. 1992;18:605–12. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estrela C, Ribeiro RG, Estrela CR, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. Antimicrobial effect of 2% sodium hypochlorite and 2% chlorhexidine tested by different methods. Braz Dent J. 2003;14:58–62. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402003000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobene RR. The effect of a pulsed water pressure cleansing device on oral health. J Periodontol. 1969;40:667–70. doi: 10.1902/jop.1969.40.11.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobene RR, Soparkar PM, Hein JW, Quigley GA. A study of the effects of antiseptic agents and a pulsating irrigating device on plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1972;43:564–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.9.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Nardo R, Chiappe V, Gómez M, Romanelli H, Slots J. Effects of 0.05% sodium hypochlorite oral rinse on supragingival biofilm and gingival inflammation. Int Dent J. 2012;62:208–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galván M, Gonzalez S, Cohen CL, Alonaizan FA, Chen CT, Rich SK, et al. Periodontal effects of 0.25% sodium hypochlorite twice-weekly oral rinse. A pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49:696–702. doi: 10.1111/jre.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich SK, Slots J. Sodium hypochlorite (dilute chlorine bleach) oral rinse in patient self-care. J West Soc Periodontol Periodontal Abstr. 2015;63:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurczyk K, Nietzsche S, Ender C, Sculean A, Eick S. In vitro activity of sodium-hypochlorite gel on bacteria associated with periodontitis. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:2165–73. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]