Abstract

In this work, poly(vinylpyrrolidone)-stabilized 3–5 nm Rh@Co core–shell nanoparticles were synthesized by a sequential reduction method, which was further in situ transformed into Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures on alumina supports. The studies of XRD, HAADF-STEM images with phase mappings, XPS, TPR, and DRIFT-IR with CO probes confirm that the as-synthesized Rh@Co nanoparticles were core–shell-like structures with Rh cores and Co-rich shells, and Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures are obtained by calcination of Rh@Co nanoparticles and subsequent selective H2 reduction. The Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanostructures demonstrated enhanced catalytic performance for hydrogenations of various substituted nitroaromatics relative to individual Rh/Al2O3 and illustrated a high catalytic stability during recycling experiments for o-nitrophenol hydrogenation reactions. The catalytic performance enhancement of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts is ascribed to the Rh-Co2O3 interfaces where the Rh-Co2O3 interaction not only prevents the active Rh particles from agglomeration but also promotes the catalytic hydrogenation performance.

1. Introduction

Catalytic hydrogenation of substituted nitroaromatics has been widely used to manufacture the corresponding substituted anilines, the intermediates for syntheses of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and dyes.1−4 Typically, supported noble metals such as Pd5,6 and Pt7−10 are efficient catalysts for hydrogenations of substituted nitroaromatics but with relatively low selectivity due to nonselective coordination of functional groups. To improve the catalytic performance of noble metals, bimetallic nanocatalysts are developed to exploit the metal–metal interaction to improve the catalytic selectivity.11−15 For example, bimetallic PtSn nanocatalysts exhibit enhanced selectivity of crotyl alcohol for hydrogenation of crotonaldehyde due to the Pt-Sn synergic effect.16

Among various bimetallic nanostructures with enhanced catalytic performances, nanostructures containing metals and metal oxides have been intensively studied because the metal–metal oxide interfaces are highly active for some hydrogenation reactions.7,17−21 In the traditional strong metal–support interaction catalysts (SMSI), reducible supports such as TiO2,22−25 CeO2,26−28 and ZrO229−31 are usually employed, where reducible supports are partially reduced by H2 at high temperatures and subsequently the partially reduced support species migrate onto metal surfaces to form metal–support interfaces that are highly active for some types of hydrogenation reactions.32,33 However, the requirement of reducible supports limits the use of readily available nonreducible Al2O3 or SiO2 supports in this system. To apply alumina or silica in SMSI catalysts, one methodology is to prepare alumina- or silica-supported bimetallic nanoparticles (NPs) where those bimetallic NPs are further transformed into metal–metal oxide heteroaggregate nanostructures on supports.34−36

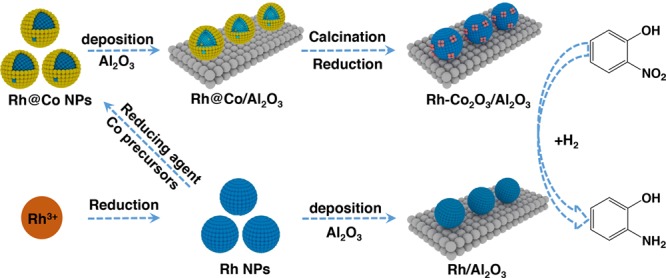

Here, we report the synthesis of alumina-supported Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 heteroaggregate nanocatalysts by in situ transformation of Rh@Co NPs. Rh has demonstrated excellent chemical and electrochemical stability37,38 and has been widely used in many catalytic and electrocatalytic reactions.39−41 However, Rh is rarely used in the catalytic hydrogenation of substituted nitroaromatics due to its lower efficiency than those Pd or Pt catalysts. In this study, to enhance its activity for nitroaromatic hydrogenations, we prepared Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures by transformation of Rh@Co NPs. The 3–5 nm Rh@Co NPs were prepared by a sequential reduction method, which was further in situ transformed into Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures by calcination and following selective H2 reduction. Scheme 1 illustrates the synthetic procedures of Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures. Hydrogenations of various substituted nitroaromatics were chosen to investigate the correlation between catalytic performance and catalyst structures. Compared with individual Rh/Al2O3 nanocatalysts, the Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 catalysts demonstrate enhanced catalytic activities as well as selectivity for hydrogenations of a series of substituted nitroaromatics. Characterization and catalytic results suggest that the synergistic effect between Co2O3 and Rh not only stabilizes the active Rh particles but also promotes the hydrogenation activity and selectivity.

Scheme 1. Schematic Illustration for the Synthesis of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Various Materials

Rh@Co core–shell-like NPs were synthesized by a seed-mediated growth method. PVP-stabilized Rh NPs were synthesized by reduction of Rh2(COOCF3)4 using EG as a reduction agent and a solvent, which was further used as a seed to deposit Co onto Rh surfaces by reduction of Co(acac)2 using NaBH4 as the reduction agent. The Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts were obtained by in situ transformation of Rh@Co/Al2O3 through calcination at 500 °C followed by H2 reduction at 250 °C.

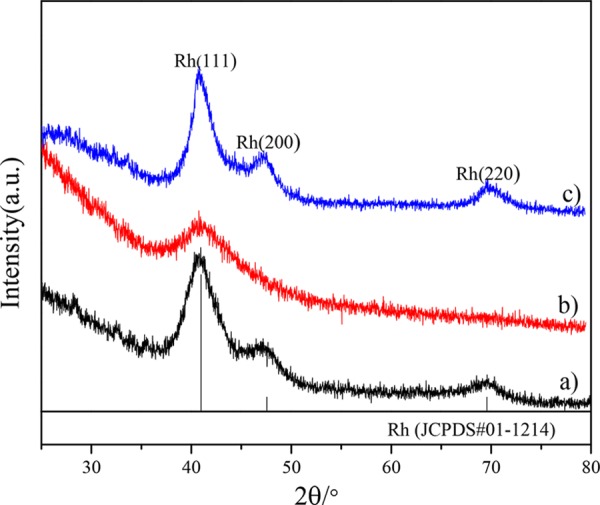

Figure 1 presents XRD patterns of Rh NPs, Rh@Co NPs, and Rh-Co2O3 NPs. The Rh-Co2O3 NPs are obtained by calcination of Rh@Co NPs at 550 °C and following H2 reduction at 250 °C. As shown in Figure 1a, the Rh NPs show well-defined fcc structures with characteristic diffractions at 41.0, 47.6, and 69.6°. While the Rh (111) diffractions in Rh@Co NPs are clearly observed in Figure 1b, the Co diffractions are not observed, which possibly suggests a core–shell-like structure with pure Rh cores and amorphous Co shells. After calcination of Rh@Co NPs and following H2 reduction, the Rh diffractions in Rh-Co2O3 NPs appear without Co2O3 diffractions, indicating heteroaggragate nanostructures consisting of Rh and amorphous Co2O3 phases. A similar phenomenon has been reported in the literature.42 The absence of Co diffractions in Rh@Co NPs and Co2O3 diffractions in Rh-Co2O3 is due to the small sizes of Co and Co2O3 phases with less crystallization, and the enrichment of the Co element in outer layers will be confirmed by HAADF-STEM with phase mappings and XPS studies.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns: (a) Rh NPs; (b) Rh@Co NPs; (c) Rh-Co2O3 NPs.

The TEM studies of Rh NPs, Rh@Co NPs, Rh/Al2O3, and Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 are shown in Figure 2a–d, respectively, and their corresponding particle size histograms are presented in Figure 3a–d, respectively. As shown in Figures 2a and 3a, the Rh NPs are relatively spherical with an average particle size of ∼4.0 nm. The inset of Figure 2a shows a lattice spacing of 0.228 nm, which is consistent with 0.227 nm of Rh (111) planes. The Rh@Co NPs in Figure 2b are spherical with an average particle size of ∼4.2 nm. The inset in Figure 2b presents the Rh (111) lattice of 0.229 nm for Rh@Co NPs, suggesting phase-pure Rh cores. The TEM images/particle size analyses of Rh/Al2O3 and Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 are illustrated in Figures 2c/3c and 2d/3d, respectively. After calcination and following reduction, the Rh particle size of Rh/Al2O3 increases from ∼4.0 nm (Figure 3a) to∼5.2 nm (Figure 3c), suggesting a size increase after thermal treatment. In contrast, the average particle size changes from ∼4.2 nm in Figure 3b to ∼4.3 nm in Figure 3d. Due to the small contrast between Co2O3 and Al2O3, the size analysis in Figure 3d is ascribed to the Rh size in Rh-Co2O3 nanostructures. The nearly same particle size before and after high-temperature treatment suggests that the Rh-Co2O3 interaction can prevent the Rh NPs from agglomeration.

Figure 2.

TEM images: (a) Rh NPs; (b) Rh@Co NPs; (c) Rh/Al2O3; (d) Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3. Scale bars in panels (a–d) are 10 nm, and those in the insets are 2 nm.

Figure 3.

Particle size analyses: (a) Rh NPs; (b) Rh@Co NPs; (c) Rh/Al2O3; (d) Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3.

To further confirm the core–shell structure of Rh@Co NPs, HAADF-STEM studies with elemental phase mappings were performed. Figure 4a–d shows the HAADF-STEM images of Rh@Co NPs and their corresponding Rh mapping, Co mapping, and the combined Rh/Co mapping, respectively. It is apparent that the Co mapping (Figure 4c) is bigger than the Rh mapping (Figure 4b), indicating the presence of Co in the shells. Moreover, the combined Rh and Co mapping in Figure 4d clearly demonstrates a core–shell structure of Rh@Co NPs with Rh cores and Co shells and is consistent with the sequential reduction method using Rh seeds. The EDS linescan of Rh@Co NPs is shown in Figure S1 and is consistent with the phase mapping, further confirming the formation of core–shell structures.

Figure 4.

(a) HAADF-STEM image of Rh@Co NPs (the red rectangle showing the selected areas for phase mappings); (b) Rh phase mapping; (c) Co phase mapping; (d) the combined Rh and Co phase mapping.

The XPS spectra of Rh@Co and Rh-Co2O3 are shown in Figure 5a,b, respectively, where Rh-Co2O3 is prepared by calcination and following reduction of as-synthesized Rh@Co NPs. The aforementioned samples were unsupported in order to obtain a better XPS signal/noise ratio. The method of Doniach and Sunjic was used for XPS curve fitting. The binding energy assignment is in accordance with those in the literature.43−45 As shown in Figure 5a, the binding energies at 307.1/311.8 and 308.1/312.8 eV in Figure 5a can be ascribed to 3d5/2/3d3/2 of metallic Rh and oxidized Rh3+ species, respectively, while the binding energies at 778.1/793.1 and 780.3/795.8 eV could be assigned to 2p3/2/2p1/2 of Co0 and Co3+ species, respectively.46−48 In addition, a broad satellite peak at 783.6/802.0 eV is assigned to 2p3/2/2p1/2 of Co2O3, suggesting that the Co ions are primarily in a high-spin electronic state.47,49,50

Figure 5.

XPS spectra: (a) as-synthesized Rh@Co NPs; (b) Rh-Co2O3 NPs.

As for the XPS spectra of Rh-Co2O3 NPs in Figure 5b, the binding energies at 307.1/311.9 and 309.0/313.7 eV can be assigned to 3d5/2/3d3/2 of Rh0 and oxidized Rh3+ species, respectively. The Co binding energies at 781.2/796.7 and 784.7/802.4 eV are ascribed to 2p3/2/2p1/2 of Co3+ and Co3+ satellite peaks, respectively. The only presence of Co3+ species is observed in Figure 5b, suggesting that calcination at 550 °C results in the complete oxidation of Co species and the following 250 °C H2 reduction cannot reduce the Co3+ species.

Table 1 summarizes the atomic ratios for different species. For Rh@Co NPs, 29.3% of Rh3+ species is observed due to the air exposure, while 77.1% of Co atoms are in the oxidation state due to air exposure. It is well known that Co is an active metal and the metallic Co NPs will be oxidized to form cobalt oxide NPs due to air exposures. Therefore, it is reasonable that the oxidized cobalt accounts for the largest percentage in XPS studies. Similarly, 30.6% of Rh3+ species is present in Rh-Co2O3 due to the surface oxidation when NPs are exposed to air. The total Co/Rh ratios of Rh@Co and Rh-Co2O3 NPs by XPS analysis are 2.3/1.0 and 2.5/1.0, respectively, while those by EDS analysis are 1.1/1.0 (1/1 ratio of the starting materials). Since XPS is a surface-sensitive technique and EDS is a bulk technique, the significantly higher Co/Rh ratios for Rh@Co and Rh-Co2O3 suggest core–shell-like structures of Rh@Co and Rh-Co2O3 NPs with nearly pure Rh cores and Co-rich shells.

Table 1. Atomic Ratios of Co/Rh by XPS and EDS Analysis.

| samples | Co0/Co3+ | Rh0/Rh3+ | Co/Rh (XPS) | Co/Rh (EDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh@Co | 22.9/77.1 | 70.8/29.3 | 2.3/1.0 | 1.1/1.0 |

| Rh-Co2O3 | 0.0/100.0 | 69.4/30.6 | 2.5/1.0 | 1.1/1.0 |

Figure 6a shows the TPO study of Rh@Co/Al2O3. The O2 consumption peaks appear below 500 °C, confirming the complete oxidation of Co and Rh in Rh@Co NPs by 500 °C calcination.51−53 H2-TPR profiles of Rh2O3-Co2O3/Al2O3 are presented in Figure 6b. A consumption peak at ∼77 °C is due to the reduction of Rh2O3.52,54,55 Moreover, H2 consumption peaks at ∼282, ∼422, and ∼658 °C are the reduction peaks of Co2O3, Co3O4, and CoO, respectively.56,57 It is concluded that only Rh will be reduced to form Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 in the reduction of Rh2O3-Co2O3/Al2O3 at 250 °C with H2, which is consistent with the XPS study of Rh-Co2O3 where only Co3+ species were observed for Rh-Co2O3 NPs.

Figure 6.

(a) O2-TPO profiles showing Rh@Co/Al2O3 materials; (b) H2-TPR profiles showing Rh2O3-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts.

Figure 7 shows DRIFT-IR spectra with CO probes of Rh/Al2O3, Rh@Co/Al2O3, and Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3. As shown in Figure 7a (Rh/Al2O3), two characteristic bands at 1906 and 2018 cm–1 are clearly observed: the former is ascribed to bridge CO on Rh sites, and the latter can be attributed to linear CO on Rh sites.58Figure 7b shows the DRIFT-IR spectrum of Rh@Co/Al2O3. The 1885 cm–1 peak for bridge CO on Rh sites and 2019 cm–1 peak for linear CO on Rh sites are clearly observed, while the bands at 1652 and 2177 cm–1 are the characteristic bands of bridged and linear CO on Co sites, respectively.59−63 The copresence of CO bands on Co and Rh sites in Figure 7b indicates that the shells are Co-rich (not pure Co). Accordingly, as shown in Figure 7c, after calcination and subsequent reduction of Rh@Co/Al2O3, the Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 shows the bands at 1640 and 2183 cm–1, which can be attributed to CO on Co sites, while the bands at 1885, 2019, and 2066 cm–1 are ascribed to CO on Rh sites.58 Again, the copresence of Co and Rh in Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 by the DRIFT-IR study indicates Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures with some naked Rh surfaces.

Figure 7.

DRIFT-IR spectra with CO probes: (a) Rh/Al2O3; (b) Rh@Co/Al2O3; (c) Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3.

2.2. Catalytic Performances of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 Nanocatalysts

Catalytic hydrogenations of various substituted nitroaromatics over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 were carried out with vigorous magnetic stirring under the reaction conditions of 45 °C and atmospheric H2 pressure. The theoretical Rh loadings Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 are both 0.5 wt %, and the real Rh loadings of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 are 0.40 and 0.47 wt %, respectively.

The hydrogenation of m-chloronitrobenzene (m-CNB) over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts with Rh/Co ratios of 2/1, 1/1, and 1/2 is shown in Table S1, and we denote the abovementioned catalysts as 2/1-Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3, Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3, and 1/2-Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3, respectively. The major product in catalytic hydrogenation of m-CNB is m-chloroaniline (m-CAN),64−66 and the main by-products are the intermediates during the hydrogenation process as well as the aniline from the hydrodechlorination reactions.67−69As shown in Table S1, compared with 2/1-Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and 1/2-Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3, the Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 catalysts illustrate a significantly enhanced performance with an m-CNB conversion of 99.6% and m-CAN selectivity of 97.0%. The comparison suggests that a ratio of Rh/Co of 1/1 is desired, and higher or lower ratios of Rh/Co result in poor catalytic performance due to a weaker Rh-Co2O3 interaction or less exposed Rh surfaces, respectively. Therefore, Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 catalysts were selected for hydrogenations of a series of substituted nitroaromatics. Moreover, as shown in Table S2, individual Co2O3/Al2O3 shows no activity, and the physical mixtures of Rh/Al2O3 and Co2O3/Al2O3 show a similar activity to that of individual Rh/Al2O3, indicating that any catalytic enhancement of Rh-Co2O3 should originate from the close-contact Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures.

Table 2 presents the catalytic performance of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 catalysts. For o- and m-CNB hydrogenations, the Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 illustrates significantly enhanced activities and selectivity relative to Rh/Al2O3. For example, the Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 shows a 99.0% o-CNB conversion with 99.8% of o-CAN selectivity even at a relatively low Rh loading, while the control Rh/Al2O3 presents 20.7% of conversion with 76.3% of selectivity. For hydrogenations of o- and p-NP, Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 also demonstrates enhanced activities and selectivity relative to control Rh/Al2O3, confirming the beneficial effect of Co2O3 on the catalytic performance due to the Rh-Co2O3 interaction. This interaction could induce a blockage effect18 where the decoration of metal oxide onto active metals will selectively facilitate the coordination of the desired functional groups, resulting in enhanced selectivity.

Table 2. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Various Substituted Nitroaromatics over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 Nanocatalysts.

Reaction conditions: reactants, 1.000 g; supported catalysts, 0.1000 g; EtOH, 25.0 mL; H2, 0.10 MPa; reaction temperature, 45 °C; speed of agitation, 500 rpm; Rh/Al2O3 (real Rh loading, 0.47 wt %); Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 (real Rh loading, 0.40 wt %).

TOF is measured as moles of reacted molecules per molar total Rh atoms per hour at a reaction time of 4 h.

The effects of reaction time on o-NP conversion and o-AP selectivity over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts are shown in Figure S2. With increasing reaction time, the conversion of o-NP increases from 8.0% at 0.5 h to 100.0% at 4.0 h, while o-AP selectivity remains at nearly 100% during the hydrogenation process, suggesting a fast process from the intermediates to the final product o-aminophenol. The effects of temperatures and catalyst weights on catalytic hydrogenation of o-NP over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts are presented in Figure 8 where the reaction time is fixed at 2.0 h. As shown in Figure 8, the conversion obviously increases with increasing temperature or catalyst weight, while the selectivity only shows a slight dependence on temperatures or catalyst weights, further confirming the fast transformation of intermediates to the final products.

Figure 8.

(a) Effect of temperatures on catalytic performance for o-NP hydrogenation over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3; (b) the effect of catalyst weights on catalytic performance for o-NP hydrogenation over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3. Reaction conditions: ambient H2 pressure; o-NP, 1.000 g; 25.0 mL of ethanol; reaction time, 2.0 h; speed of agitation, 500 rpm; Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3, 0.1000 g for (a); reaction temperature, 45 °C for (b).

2.3. Catalytic Stability of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 Nanocatalysts

Recycling experiments of o-NP catalytic hydrogenations were performed to investigate the catalytic stability of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3. During the process, no fresh catalysts were added into the systems, and less solvents and substrates are charged in the following cycles to fix the ratios of solvent/catalyst and substrate/catalyst. As shown in Table 3, from cycles 1 to 5, the o-NP conversion and selectivity over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 are highly stable with 100% of o-NP conversion and above 98.7% of o-AP selectivity, strongly suggesting a good structural stability of Rh-Co2O3 heteroaggregate nanostructures.

Table 3. Cycle to Cycle o-NP Hydrogenations over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 Catalysts.

| cycle indexa | catalyst (g) | o-NP (g) | conversion (%) | o-NP selectivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0905 | 0.905 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 2 | 0.0756 | 0.756 | 100.0 | 99.4 |

| 3 | 0.0621 | 0.621 | 100.0 | 99.3 |

| 4 | 0.0555 | 0.555 | 100.0 | 98.7 |

| 5 | 0.0465 | 0.465 | 100.0 | 99.5 |

Reaction conditions: EtOH, 22.6 mL in cycle 1; the volume of EtOH in the following cycles decreased according to the weight of o-NP at a fixed EtOH/o-NP ratio; H2, 0.10 MPa; reaction time, 4.0 h; reaction temperature, 45 °C; agitation speed, 500 rpm.

3. Conclusions

In summary, Rh@Co core–shell-like NPs were successfully prepared by a sequential reduction method, and Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 heteroaggregate nanocatalysts were synthesized by in situ transformation of Rh@Co NPs on Al2O3 supports. Various characterizations confirm that the Rh@Co NPs consist of pure Rh cores and Co-rich shells, and Rh-Co2O3 NPs are close-contact heteroaggregate nanostructures. The Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts show enhanced catalytic activity and selectivity for the hydrogenations of o-CNB, m-CNB, o-NP, m-NP, and p-NP relative to the control Rh/Al2O3 nanocatalysts, and the catalytic performance enhancement of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 is ascribed to the strong Rh-Co2O3 interaction.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemicals

Cobalt acetylacetonate (Co(acac)2, 98%), rhodium(II) trifluoroacetate dimer (Rh2(COOCF3)4, GR), sodium trifluoroacetate (NaCOOCF3, >98%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, >96%), o-nitrophenol (o-NP, >99%), m-nitrotoluene (m-NP, 98%), p-nitrophenol (p-NP, >98%), o-chloronitrobenzene (o-CNB, 99%), and m-chloronitrobenzene (m-CNB, 98%) were purchased from Aladdin. Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP-K30, GR), triethylene glycol (TREG, AR), ethylene glycol (EG, AR), absolute ethyl alcohol (AR), and acetone (AR) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Aluminum oxide powders calcined at 500 °C for 3 h were purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd. All of the reagents were used as received without further purification.

4.2. Catalyst Preparation

4.2.1. Synthesis of Rh NPs

Rh NPs were synthesized by a reported method.70 In a typical synthesis, 0.050 mmol of Rh2(COOCF3)4, 277.5 mg of PVP-K30, 1.0 mmol of NaCOOCF3, and 10.0 mL of EG were transferred into a 50 mL three-necked round-bottom flask. The system was heated to 115 °C with vigorous magnetic stirring under a nitrogen atmosphere. The color of the solution gradually changed from light blue to black, indicating the reduction of Rh precursors. After maintaining at 115 °C for 15 min, the system was further heated to and maintained at 155 °C for 75 min. The mixture was cooled to room temperature followed by centrifugation with acetone and ethyl alcohol three times to collect black solids for further characterization.

4.2.2. Synthesis of Rh@Co Core–Shell NPs

Rh@Co NPs were synthesized by a sequential reduction method. Rh NP solids (0.05 mmol Rh) dispersed in 10.0 mL of TREG and 277.5 mg of PVP-K30 were charged into a 50 mL three-necked round-bottom flask with vigorous magnetic stirring under a N2 atmosphere. The mixture was further heated to 175 °C, and then 0.05 mmol of Co(acac)2 in 1.0 mL of absolute methanol was injected into the system using a syringe followed by addition of 1.0 mmol of solid NaBH4. The mixture was maintained at 175 °C for 2 h to complete the reduction of Co precursors. The mixture was further cooled to room temperature followed by centrifugation with acetone and ethyl alcohol three times to collect black solids for further characterization.

4.2.3. Synthesis of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 Nanocatalysts

The collected Rh@Co solids were redispersed in absolute ethanol in a 100 mL three-necked round-bottom flask, and a calculated amount of alumina (a Rh theoretical loading of 0.5 wt %) was added to the abovementioned colloid. The resultant mixture was further heated to 60 °C and purged with N2 to remove ethanol to obtain the gray Rh@Co2O3/Al2O3 materials, which was then calcined at 500 °C in air for 3 h and subsequently reduced in H2 at 250 °C for 3 h with a 50 v/v H2/N2 gas to give Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts.

The synthesis of Rh/Al2O3 nanocatalysts with a Rh theoretical loading of 0.5 wt % was the same as that of Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 nanocatalysts except that the redispersed Rh ethanol colloids are used. The real metal loadings of Rh/Al2O3 and Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 were determined by ICP-OES.

4.3. Catalyst Characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Rh, Rh@Co, and Rh-Co2O3 NPs were obtained using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation in the 2θ range from 20 to 90°. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were obtained by using a JEOL 2100 transmission electron microscope operated at 200 kV. The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transition electron microscopy images (HAADF-STEM) with phase mappings were obtained using a Talos F200x, which is operated at 200 kV with 0.16 nm resolution for STEM images. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were obtained on an AXIS ULTRA DLD multifunctional X-ray photoelectron spectroscope with an Al source. The instrument was calibrated by C 1s (284.8 eV), and the XPS data were processed using a Casa XPS software. The studies of O2 temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) of Rh@Co/Al2O3 and H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) of Rh2O3-Co2O3/Al2O3 were performed on an Auto ChemII 2920 instrument. The diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectra (DRIFT-IR) with CO probes were obtained using a Nicolet-6700 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm–1 and the number of scans of 32. At first, the materials were pretreated with H2 at 100 °C for 20 min at a gas flow rate of 20 mL/min followed by cooling down to 30 °C. After the samples were purged with Ar at 30 °C for 20 min, the DRIFT-IR background spectrum was recorded. The samples were further treated with CO (99.99%) at a gas flow rate of 20 mL min–1 at 30 °C for 20 min and subsequently purged with Ar to remove the free CO before the DRIFT-IR spectra were recorded. The product analyses of catalytic hydrogenations of substituted nitroaromatics over Rh-Co2O3/Al2O3 and Rh/Al2O3 were performed by a GC 2060 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector.

4.4. Catalyst Activity Measurements

The atmospheric H2 pressure and a vigorous magnetic stirring at 500 rpm are employed for hydrogenations of various substituted nitroaromatics with H2. Various substituted nitroaromatics (1.0000 g), supported catalysts (0.1000 g), and absolute ethanol (25 mL) were charged into a 100 mL three-necked round-bottom flask. The system was heated to and kept at a desired temperature under 0.1 MPa H2 for the defined reaction time. After the reaction was done, the solid catalysts were collected by centrifugation, and the liquid products were analyzed by a gas chromatograph. For recycling experiments, after each cycle, the solid catalysts were collected by centrifugation, washed with ethyl alcohol several times, and further dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight. In the next cycle experiment, the amounts of substituted nitroaromatics and solvents were decreased according to the weights of recovered catalysts to keep the ratios of reactant/catalyst and reactant/solvent constant.

Acknowledgments

S.Z. and H.Y. thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China for financial supports (Grant Nos. 21776090 and 21571183), and this work is also partially supported by the Industrial R&D Foundation of Ningbo (Grant No. 2017B10040).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03340.

More synthesis, EDS linescan of Rh@Co NPs, and more comparison of different catalysts (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Downing R. S.; Kunkeler P. J.; Van Bekkum H. Catalytic Syntheses of Aromatic Amines. Catal. Today 1997, 37, 121–136. 10.1016/S0920-5861(97)00005-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja R.; Golovko V. B.; Thomas J. M.; Berenguer-Murcia A.; Zhou W.; Xie S.; Johnson B. F. Highly Efficient Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of Nitro-Substituted Aromatics. Chem. Commun. 2005, 2026–2028. 10.1039/b418273a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller T. E.; Hultzsch K. C.; Yus M.; Foubelo F.; Tada M. Hydroamination: Direct Addition of Amines to Alkenes and Alkynes. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3795–3892. 10.1021/cr0306788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F. Carbon-Heteroatom Bond Formation Catalysed by Organometallic Complexes. Nature 2008, 455, 314–322. 10.1038/nature07369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Lizana F.; Gómez-Quero S.; Amorim C.; Keane M. A. Gas Phase Hydrogenation of p-Chloronitrobenzene over Pd-Ni/Al2O3. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 473, 41–50. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C.; Han J.; Shen K.; Wang L.; Zhao D.; Freeman H. S. Palladium Nanoparticle Microemulsions: Formation and Use in Catalytic Hydrogenation of o-Chloronitrobenzene. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 709–713. 10.1016/j.cej.2010.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A.; Serna P.; Concepción P.; Calvino J. J. Transforming Nonselective into Chemoselective Metal Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of Substituted Nitroaromatics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8748–8753. 10.1021/ja800959g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna P.; Boronat M.; Corma A. Tuning the Behavior of Au and Pt Catalysts for the Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Top. Catal. 2011, 54, 439–446. 10.1007/s11244-011-9668-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nie R.; Wang J.; Wang L.; Qin Y.; Chen P.; Hou Z. Platinum Supported on Reduced Graphene Oxide as a Catalyst for Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. Carbon 2012, 50, 586–596. 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S.; Takeuchi Y.; Harada A.; Takagi T.; Takenaka Y.; Fukaya N.; Yasuda H.; Ohmori T.; Endo A. Microreactor Containing Platinum Nanoparticles for Nitrobenzene Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal., A 2012, 427-428, 119–124. 10.1016/j.apcata.2012.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serna P.; Concepción P.; Corma A. Design of Highly Active and Chemoselective Bimetallic Gold-Platinum Hydrogenation Catalysts through Kinetic and Isotopic Studies. J. Catal. 2009, 265, 19–25. 10.1016/j.jcat.2009.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y.; Qi Z.; Goh T. W.; Wang L.-L.; Maligal-Ganesh R. V.; MacMurdo H. L.; Zhang S.; Xiao C.; Li X.; Tao F.; Johnson D. D.; Huang W. Intermetallic Structures with Atomic Precision for Selective Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. J. Catal. 2017, 356, 307–314. 10.1016/j.jcat.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser H.-U.; Steiner H.; Studer M. Selective Catalytic Hydrogenation of Functionalized Nitroarenes: an Update. ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 210–221. 10.1002/cctc.200900129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H.; Wei X.; Yang X.; Yin G.; Wang A.; Liu X.; Huang Y.; Zhang T. Supported Au-Ni Nano-Alloy Catalysts for the Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 160–167. 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60254-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.; Shang N.; Zhou X.; Feng C.; Gao S.; Wang C.; Wang Z. High Catalytic Activity of a Bimetallic AgPd Alloy Supported on UiO-66 Derived Porous Carbon for Transfer Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes using Formic Acid-Formate as the Hydrogen Source. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9857–9865. 10.1039/C7NJ00442G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taniya K.; Yu C. H.; Takado H.; Hara T.; Okemoto A.; Horie T.; Ichihashi Y.; Tsang S. C.; Nishiyama S. Synthesis of Bimetallic SnPt-Nanoparticle Catalysts for Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Crotonaldehyde: Relationship between SnxPty Alloy Phase and Catalytic Performance. Catal. Today 2018, 303, 241–248. 10.1016/j.cattod.2017.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H.; Wang C.; Zhu H.; Overbury S. H.; Sun S.; Dai S. Colloidal Deposition Synthesis of Supported Gold Nanocatalysts based on Au-Fe3O4 Dumbbell Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4357–4359. 10.1039/b807591c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Ibrahim M.; Collière V.; Asakura H.; Tanaka T.; Teramura K.; Philippot K.; Yan N. Rh Nanoparticles with NiOx Surface Decoration for Selective Hydrogenolysis of C-O Bond over Arene Hydrogenation. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2016, 422, 188–197. 10.1016/j.molcata.2016.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A.; Serna P. Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitro Compounds with Supported Gold Catalysts. Science 2006, 313, 332–334. 10.1126/science.1128383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. R.; Kennedy G.; Van Spronsen M.; Hervier A.; Cai X.; Chen S.; Wang L.-W.; Somorjai G. A. Furfuraldehyde Hydrogenation on Titanium Oxide-Supported Platinum Nanoparticles Studied by Sum Frequency Generation Vibrational Spectroscopy: Acid-Base Catalysis Explains the Molecular Origin of Strong Metal-Support Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14208–14216. 10.1021/ja306079h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Guo X.-W.; Liang H.; Ge H.; Gu X.; Chen S.; Yang H.; Qin Y. Tailoring Pt-Fe2O3 Interfaces for Selective Reductive Coupling Reaction to Synthesize Imine. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6560–6566. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boronat M.; Illas F.; Corma A. Active Sites for H2 Adsorption and Activation in Au/TiO2 and the Role of the Support. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2009, 113, 3750–3757. 10.1021/jp808271y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewera A.; Timperman L.; Roguska A.; Alonso-Vante N. Metal-Support Interactions between Nanosized Pt and Metal Oxides (WO3 and TiO2) Studied Using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Phys.Chem.C. 2011, 115, 20153–20159. 10.1021/jp2068446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Smith S. C. Strong Interaction between Gold and Anatase TiO2 (001) Predicted by First Principle Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 3524–3531. 10.1021/jp208948x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar A.; Vannice M. A. Crotonaldehyde Hydrogenation on Pt/TiO2 and Ni/TiO2 SMSI Catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 183, 344–354. 10.1006/jcat.1999.2419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrabés N.; Föttinger K.; Llorca J.; Dafinov A.; Medina F.; Sá J.; Hardacre C.; Rupprechter G. Pretreatment Effect on Pt/CeO2 Catalyst in the Selective Hydrodechlorination of Trichloroethylene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 17675–17682. 10.1021/jp1048748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ou D. R.; Mori T.; Togasaki H.; Takahashi M.; Ye F.; Drennan J. Microstructural and Metal-Support Interactions of the Pt-CeO2/C Catalysts for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Application. Langmuir 2011, 27, 3859–3866. 10.1021/la1032898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugai J.; Subramani V.; Song C.; Engelhard M.; Chin Y. Effects of Nanocrystalline CeO2 Supports on the Properties and Performance of Ni-Rh Bimetallic Catalyst for Oxidative Steam Reforming of Ethanol. J. Catal. 2006, 238, 430–440. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youn M. H.; Seo J. G.; Jung J. C.; Park S.; Park D. R.; Lee S.-B.; Song I. K. Hydrogen Production by Auto-thermal Reforming of Ethanol over Ni Catalyst Supported on ZrO2 Prepared by a Sol-gel Method: Effect of H2O/P123 Mass Ratio in the Preparation of ZrO2. Catal. Today 2009, 146, 57–62. 10.1016/j.cattod.2008.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Ding Y.; Duan J.; Zhang Q.; Wang Z.; Lou H.; Zheng X. Transesterification of Sunflower Oil to Biodiesel on ZrO2 Supported La2O3 Catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 953–958. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.-C.; Liu Q.; Chen M.; Liu Y.-M.; Cao Y.; He; Fan K.-N. Structural Evolution and Catalytic Properties of Nanostructured Cu/ZrO2 Catalysts Prepared by Oxalate Gel-Coprecipitation Technique. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 16549–16557. 10.1021/jp075930k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tauster S. J.; Fung S. C.; Garten R. L. Strong Metal-Support Interactions. Group 8 Noble Metals Supported on Titanium Dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 170–175. 10.1021/ja00469a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tauster S. J. Strong Metal-Support Interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1987, 20, 389–394. 10.1021/ar00143a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Zhang P.; Yu H.; Ma Z.; Zhou S. Mesoporous KIT-6 Supported Pd–MxOy (M = Ni, Co, Fe) Catalysts with Enhanced Selectivity for p-Chloronitrobenzene Hydrogenation. Catal. Lett. 2015, 145, 784–793. 10.1007/s10562-015-1480-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Yu H.; Xiong C.; Zhou S. Architecture Controlled PtNi@mSiO2 and Pt-NiO@mSiO2 Mesoporous Core-Shell Nanocatalysts for Enhanced p-Chloronitrobenzene Hydrogenation Selectivity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 20238–20247. 10.1039/C5RA00429B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Yu H.; Hua D.; Zhou S. Enhanced Catalytic Hydrogenation Activity and Selectivity of Pt-MxOy/Al2O3 (M = Ni, Fe, Co) Heteroaggregate Catalysts by in Situ Transformation of PtM Alloy Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7294–7302. 10.1021/jp309548v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Bai J.; Wu X.-R.; Chen P.; Jin P.-J.; Yao H.-C.; Chen Y. Atomically ultrathin RhCo alloy nanosheet aggregates for efficient water electrolysis in broad pH range. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 16437–16446. 10.1039/C9TA05334D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J.; Han S.-H.; Peng R.-L.; Zeng J.-H.; Jiang J.-X.; Chen Y. Ultrathin Rhodium Oxide Nanosheet Nanoassemblies: Synthesis, Morphological Stability, and Electrocatalytic Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 17195–17200. 10.1021/acsami.7b04874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.; Xue Q.; Peng R.; Jin P.; Zeng J.; Jiang J.; Chen Y. Bimetallic AuRh Nanodendrites Consisting of Au Icosahedron Cores and Atomically Ultrathin Rh Nanoplate Shells: Synthesis and Light-Enhanced Catalytic Activity. NPG Asia Mater. 2017, 9, e407. 10.1038/am.2017.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S.; Liu Z.; Xue Q.; Yin S.; Li F.; Cai W.; Li S.; Chen P.; Jin P.; Yao H.; Chen Y. Rh Nanoroses for Isopropanol Oxidation Reaction. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 259, 118082. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J.; Huang H.; Li F.-M.; Zhao Y.; Chen P.; Jin P.-J.; Li S.-N.; Yao H.-C.; Zeng J.-H.; Chen Y. Glycerol Oxidation Assisted Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: Ammonia and Glyceraldehyde Co-Production on Bimetallic RhCu Ultrathin Nanoflake Nanoaggregates. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 21149–21156. 10.1039/C9TA08806G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-J.; Zhang B.-P.; Yan L.-P.; Deng W. Microstructure and Optical Absorption Properties of Au-Dispersed CoO Thin Films. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 5731–5735. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.02.154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linsmeier C.; Taglauer E. Strong Metal-Support Interactions on Rhodium Model Catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 2011, 391, 175–186. 10.1016/j.apcata.2010.07.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Óvári L.; Kiss J. Growth of Rh Nanoclusters on TiO2 (110): XPS and LEIS Studies. Appl. Catal., A 2006, 252, 8624–8629. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.11.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Qian Q.; Yan F.; Yuan G. Particle Growth and Redispersion of Monodisperse Rhodium Nanoparticles Supported by Porous Carbon Microspherules during Catalyzing Vapor Phase Methanol Carbonylation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 107, 310–316. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2007.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khassin A. A.; Yurieva T. M.; Kaichev V. V.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Budneva A. A.; Paukshtis E. A.; Parmon V. N. Metal-Support Interactions in Cobalt-Aluminum Co-Precipitated Catalysts: XPS and CO Adsorption Studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2001, 175, 189–204. 10.1016/S1381-1169(01)00216-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. F.; Xu J. B.; Zhang B.; Yu H. G.; Wang J.; Zhang X.; Yu J. G.; Li Q. Signature of Intrinsic High-Temperature Ferromagnetism in Cobalt-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2476–2480. 10.1002/adma.200600396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Yuan P.; Zhang J.; Xia H.; Cheng F.; Zhou M.; Li J.; Qiao Y.; Mu S.; Xu Q. Co2P-CoN Double Active Centers Confined in N-Doped Carbon Nanotube: Heterostructural Engineering for Trifunctional Catalysis toward HER, ORR, OER, and Zn-Air Batteries Driven Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1805641. 10.1002/adfm.201805641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-J.; Song J.-H.; Yoon Y.-S.; Kim T.-S.; Kim K.-J.; Choi W.-K. Enhancement of CO Sensitivity of Indium Oxide-based Semiconductor Gas Sensor through Ultra-Thin Cobalt Adsorption. Sens. Actuators, B 2001, 79, 200–205. 10.1016/S0925-4005(01)00876-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H.; Li K.; Guo Y.; Guo J.; Xu Q.; Zhang J. CoS2 Nanodots Trapped within Graphitic Structured N-doped Carbon Spheres with Efficient Performances for Lithium Storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 7148–7154. 10.1039/C8TA00689J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rassoul M.; Gaillard F.; Garbowski E.; Primet M. Synthesis and Characterisation of Bimetallic Pd-Rh/Alumina Combustion Catalysts. J. Catal. 2001, 203, 232–241. 10.1006/jcat.2001.3328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padeste C.; Cant N. W.; Trimm D. L. Reactions of Ceria Supported Rhodium with Hydrogen and Nitric Oxide Studied with TPR/TPO and XPS Techniques. Catal. Lett. 1994, 28, 301–311. 10.1007/BF00806060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata B.; Bosch P.; Fetter G.; Valenzuela M. A.; Navarrete J.; Lara V. H. Co(II)-Co(III) Hydrotalcite-like Compounds. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 23–29. 10.1016/S1466-6049(00)00097-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C.-P.; Yeh C.-T.; Zhu Q. Rhodium-Oxide Species Formed on Progressive Oxidation of Rhodium Clusters Dispersed on Alumina. Catal. Today 1999, 51, 93–101. 10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00011-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-López A.; Such-Basáñez I.; de Lecea C. S.-M. Stabilization of Active Rh2O3 Species for Catalytic Decomposition of N2O on La-, Pr-Doped CeO2. J. Catal. 2006, 244, 102–112. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y.; Zhao Z.; Duan A.; Jiang G.; Liu J. Comparative Study on the Formation and Reduction of Bulk and Al2O3-Supported Cobalt Oxides by H2-TPR Technique. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2009, 113, 7186–7199. 10.1021/jp8107057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van’T Blik H. F. J.; Koningsberger D. C.; Prins R. Characterization of Supported Cobalt and Cobalt-Rhodium Catalysts: III. Temperature-Programmed Reduction (TPR), Oxidation (TPO), and EXAFS of CoRhSiO2. J. Catal. 1986, 97, 210–218. 10.1016/0021-9517(86)90051-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Liu H.; Han M.; Li X.; Jiang D. Carbonylation of Methanol Catalyzed by Polymer-Protected Rhodium Colloid. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1997, 118, 145–151. 10.1016/S1381-1169(96)00387-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heal M. J.; Leisegang E. C.; Torrington R. G. Infrared Studies of Carbon Monoxide and Hydrogen Adsorbed on Silica-Supported Iron and Cobalt Catalysts. J. Catal. 1978, 314–325. 10.1016/0021-9517(78)90269-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulla M. A.; Spretz R.; Lombardo E.; Daniell W.; Knözinger H. Catalytic Combustion of Methane on Co/MgO: Characterisation of Active Cobalt Sites. Appl. Catal., B 2001, 29, 217–229. 10.1016/S0926-3373(00)00204-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzoli D.; Occhiuzzi M.; Cimino A.; Cordischi D.; Minelli G.; Pinzari F. XPS and EPR Study of High and Low Surface Area CoO-MgO Solid Solutions: Surface Composition and Co2+ Ion Dispersion. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1996, 92, 4567–4574. 10.1039/FT9969204567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielminotti E.; Coluccia S.; Garrone E.; Cerruti L.; Zecchina A. Infrared Study of CO Adsorption on Magnesium Oxide. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 1979, 75, 96–108. 10.1039/F19797500096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues E. L.; Bueno J. M. C. Co/SiO2 Catalysts for Selective Hydrogenation of Crotonaldehyde II: Influence of the Co Surface Structure on Selectivity. Appl. Catal., A 2002, 232, 147–158. 10.1016/S0926-860X(02)00090-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Tang W.; Xie Z.; Yu H.; Yin H.; Xu Y.; Zhao S.; Zhou S. Design of Highly Efficient Pt-SnO2 Hydrogenation Nanocatalysts using Pt@Sn Core-Shell Nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1583–1591. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.; Sun J.; Wang Y.; Yang J. A Fe-promoted Ni–P amorphous alloy catalyst (Ni–Fe–P) for liquid phase hydrogenation of m- and p-chloronitrobenzene. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006, 252, 17–22. 10.1016/j.molcata.2006.01.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Ma R.; Cao B.; Liang J.; Ren Q.; Song H. Effect of Co-B Supporting Methods on the Hydrogenation of m-Chloronitrobenzene over Co-B/CNTs Amorphous Alloy Catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 2016, 514, 248–252. 10.1016/j.apcata.2016.01.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahata N.; Soares O. S. G. P.; Rodríguez-Ramos I.; Pereira M. F. R.; Órfão J. J. M.; Figueiredo J. L. Promotional Effect of Cu on the Structure and Chloronitrobenzene Hydrogenation Performance of Carbon Nanotube and Activated Carbon Supported Pt Catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 2013, 464-465, 28–34. 10.1016/j.apcata.2013.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Lizana F.; Hao Y.; Crespo-Quesada M.; Yuranov I.; Wang X.; Keane M. A.; Kiwi-Minsker L. Selective Gas Phase Hydrogenation of p-Chloronitrobenzene over Pd Catalysts: Role of the Support. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1386–1396. 10.1021/cs4001943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Perret N.; Delgado J. J.; Blanco G.; Chen X.; Olmos C. M.; Bernal S.; Keane M. A. Reducible Support Effects in the Gas Phase Hydrogenation of p-Chloronitrobenzene over Gold. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 994–1005. 10.1021/jp3093836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biacchi A. J.; Schaak R. E. Ligand-Induced Fate of Embryonic Species in the Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Rhodium Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 1707–1720. 10.1021/nn506517e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.