Abstract

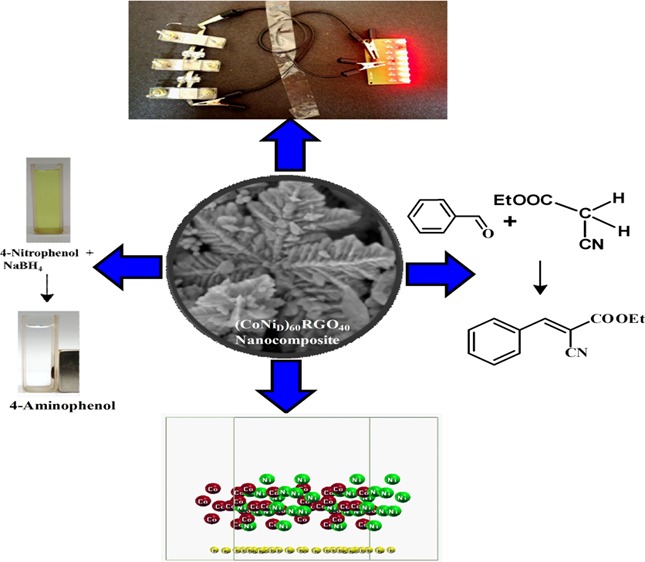

In this paper, a simple “one pot” methodology to synthesize snowflake-like dendritic CoNi alloy-reduced graphene oxide (RGO) nanocomposites has been reported. First-principles quantum mechanical calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) have been conducted to understand the electronic structures and properties of the interface between Co, Ni, and graphene. Detailed investigations have been conducted to evaluate the performance of CoNi alloy and CoNi-RGO nanocomposites for two different types of applications: (i) as the catalyst for the reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol and Knoevenagel condensation reaction and (ii) as the active electrode material in the supercapacitor applications. Here, the influence of microstructures of CoNi alloy particles (spherical vs snowflake-like dendritic) and the effect of immobilization of CoNi alloy on the surface of RGO on the performance of CoNi-RGO nanocomposites have been demonstrated. CoNi alloy having a snowflake-like dendritic microstructure exhibited better performance than that of spherical CoNi alloy, and CoNi-RGO nanocomposites showed improved properties compared to CoNi alloy. The kapp value of the (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol is 20.55 × 10–3 s–1, which is comparable and, in some cases, superior to many RGO-based catalysts. The (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed Knoevenagel condensation reaction showed the % yield of the products in the range of 80–93%. (CoNiD)60RGO40 showed a specific capacitance of 501 F g–1 (at 6 A g–1), 21.08 Wh kg–1 energy density at a power density of 1650 W kg–1, and a retention of ∼85% of capacitance after 4000 cycles. These results indicate that (CoNiD)60RGO40 could be considered as a promising electrode material for high-performance supercapacitors. The synergistic effect, derived from the hierarchical structure of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites, is the origin for its superior performance. The easy synthetic methodology, high catalytic efficiency, and excellent supercapacitance performance make (CoNiD)60RGO40 an appealing multifunctional material.

1. Introduction

Bimetallic nanoparticles have gained immense attraction from the researchers because of their plethora of applications in diverse fields such as catalysis, optical, magnetic, biomedical, magnetic devices, etc.1 In many cases, the physicochemical properties of the bimetallic alloys, particularly in their nanostructure form, are superior to those of the constituent metals. The alteration of the electronic structures of the metals, which occurs due to their alloy formation, is responsible for the improvement of the properties of the alloys.1

Though compared to bulk materials, nanostructured materials exhibit exotic properties and superior performance in many applications (e.g., catalysis, magnetic, electrical, optical, etc.), but the agglomeration of nanoparticles due to their high surface energy quite often poses a major challenge. To overcome this limitation, the immobilization of the nanoparticles on a suitable support appeared as an attractive strategy. For the past couple of years, graphene or reduced graphene oxide (RGO) has attracted the attention of the scientists as an interesting support material for immobilization of a variety of nanoparticles for different applications.2,3 The unique properties of graphene, such as large specific surface area (∼2600 m2 g–1),4,5 chemical stability, mechanical flexibility with Young’s modulus (∼1 TP),6 high adsorption capacity of different ions on its surface, etc., make it a very promising support material and broaden the horizons of applications of graphene-based nanocomposites. The additional advantage that graphene offers as a support matrix is that it possesses high electrical conductivity and its π electrons affect the electronic structure of the nanoparticles, which are immobilized on its surface and in turn influence their properties.

Our current work deals with the catalytic and electrochemical properties of CoNi alloy and CoNi-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites. CoNi alloy is an important transition metal alloy system that has been widely used for catalysis, magnetic devices, microwave absorption, etc.7 It has already been reported that CoNi alloy exhibit a superior catalytic and electrochemical property to the monometallic counterpart.8 The CoNi alloy system exhibits richer faradic redox reactions, higher electrical conductivity, stability, and enhanced electrochemical performance due to the synergistic effect arising from the intimate coexistence of Ni and Co in the alloy.8,9 The electrochemical performances of various types of CoNi-based systems (such as CoNi oxides, CoNi hydroxides, NiCo chalcogenides, CoNi phosphides, etc.) have been reported by several researchers where the improved electrochemical properties of the bimetallic systems have been demonstrated.9−13

Several synthetic methodologies, such as electrodeposition, hydro/solvothermal, sol–gel, spray pyrolysis, polyol process, microemulsion, mechanical alloying, etc., have been reported by several researchers for the preparation of CoNi alloy with different microstructures (e.g., Ni49Co51 sphere, NiCo dumbbells, Ni70Co30 nanorings, NiCo nanochains, NiCo nanowire, handkerchief-like Ni82Co18, CoNi nanoneedle, Ni19Co81 nanotube array, etc.).14 Wu et al.14 have reported a solution-phase reduction method to prepare NiCo alloy having a dendritic structure. They have shown that the presence of sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate resulted in the formation of flower-like microstructures, whereas cetyltrimethylammonium bromide produced dendritic Ni33.8Co66.2 alloy.14 Rashid et al. have synthesized chain-like CoNi nanostructures by employing a polymer-assisted methodology, where poly(vinyl methyl ether) was used.1

Here, we report the synthesis of CoNi alloy particles with a snowflake-like dendritic structure and the nanocomposites (CoNi-RGO), where the surface of the nanometer-thin RGO sheets are decorated with these CoNi alloy nanoparticles. We have evaluated the performance of these materials as the catalyst for two important reactions: (i) reduction of 4-nitrophenol to 4-aminophenol in the presence of NaBH4 and (ii) Knoevenagel condensation reaction between an aromatic aldehyde and ethyl cyanoacetate. We have also studied the electrochemical properties of these materials to explore the possibility of the use of these materials as an electrode material for high-performance supercapacitor applications. We have chosen to investigate the abovementioned applications of the synthesized CoNi-RGO nanocomposites for the following reasons:

-

(i)

Reduction of 4-nitrophenol reaction: The reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) to 4-aminophenol (4-AP) in the presence of an excess of NaBH4 in an aqueous medium was chosen as a model reaction because this is simple and trustworthy, can easily monitor the reaction, and yields a single product. This reaction has been extensively used by the researchers across the globe to evaluate the catalytic property of the nanostructured catalysts developed by them.15,16 Moreover, nitrophenols and their derivatives are used/produced during the commercial production of a variety of chemicals (e.g., synthetic dyes, herbicides, insecticides, pesticides, etc.), and 4-NP is used in numerous industries such as pharmaceutical, textile, leather, steel manufacturing, refinery, etc. The effluents from these industries contain a considerable amount of 4-NP, which causes water pollution due to its toxicity. It has detrimental effects on the central nervous system, kidney, liver, and blood for both humans and animals.17 On the other hand, 4-AP, which is produced from the reduction of 4-NP, is a useful chemical for polymer, pharmaceutical, herbicide, etc., production industries.15,16,18 Several types of nanocatalysts, including noble metals, coinage metals, and catalysts where various metal nanoparticles are supported on solid supports (e.g., silica, alumina, polymer, dendrimer, etc.), graphene/RGO-supported catalysts, magnetic nanoparticle (such as ferrites)-based nanocomposites, etc., have been reported for the reduction reaction of 4-NP in the presence of excess of NaBH4.19,20 In Table S1, several nanocatalysts (including Co, Ni, and CoNi alloy catalysts), which were reported for the reduction of 4-NP in an aqueous medium in the presence of excess NaBH4, and the associated rate constants for the catalysis reaction are listed.

-

(ii)

Knoevenagel condensation reaction: Knoevenagel condensation reaction is one of the important and widely used carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions. This reaction involves the condensation between a carbonyl compound and a compound having an active methylene group containing one or two electron-withdrawing groups (such as nitrile, acyl, and nitro). This reaction is extensively used for the commercial production of many cosmetics, perfumes, coumarin derivatives, fine chemicals, pharmaceutical chemicals, etc.21 Traditionally, this reaction is performed in the presence of different bases (e.g., ammonia, ethylenediamine, piperidine, etc.) and their salts.22 However, quite often, the use of homogeneous catalysts causes the problem in the purification of the product and demands tedious workup procedures.23 Therefore, some heterogeneous catalysts like Al2O3,24 zeolite,25 ionic liquids,26 metal–organic frameworks, metal ion-based coordination polymers, mesoporous silica-based catalysts, etc., have been developed for the Knoevenagel condensation reaction.27 However, some of the disadvantages often experienced during the use of these catalysts are the harsh reaction conditions, low yield of the product, need of toxic/expensive organic solvents, low reusability of the catalysts, etc. Examples of some of the metal nanoparticle-based catalysts, which have been reported for the Knoevenagel reaction are Fe powder, Cu powder, Co powder, C/Co, C/Fe, Ag powder, Au powder, Ni nanoparticles, etc.22,23 As nanosized catalysts are difficult to separate from the reaction mixture, development of magnetically separable catalysts has been adopted by several researchers as a promising strategy. NiFe2O421 and CoFe2O428 nanoparticles have been reported as magnetically separable catalysts for the Knoevenagel reaction.

-

(iii)

Supercapacitor: Supercapacitors are of immense interest due to their applications in varieties of energy storage and conversion systems, such as electric vehicles, uninterruptible power supplies, laptop, solid-state devices, mobile phones, load leveling, intermittent wind, solar energy systems, etc.29 The use of supercapacitors in the emergency doors of an Airbus A380 is one of many of its commercial applications. In the supercapacitors, the charging or discharging process generally takes place in seconds. Though supercapacitors possess a lower energy density (∼5 Wh kg–1) than batteries, they can provide higher power density (∼10 kW kg–1) for shorter times.30 Electrical double layer (EDL) electrodes and pseudocapacitor electrodes are the two major classes of supercapacitors based on their different charge storage mechanisms. In EDL electrodes, which are mostly carbon-based materials, energy storage occurs via fast ion adsorption on the electrode surface. As this process is highly dependent on the available surface area of the active electrode materials, porous carbon and graphene-based electrodes exhibit high power density and long shelf life but low energy density.31 Fast redox reactions at the electrode/electrolyte interface are the origin of the high capacitance of pseudocapacitor electrodes. Several metals oxides, conducting polymers, etc., have been reported as electrode materials to construct pseudocapacitor electrodes.32,33 However, one of the limitations associated with pseudocapacitor electrodes is their poor cycling performance, which might be due to the structural instability of electrode materials in the reaction process.34 To achieve a supercapacitor with high capacitor performance, design of composites, composed of carbon-based materials and redox-active materials, is an attractive strategy, where the advantages of EDLCs and pseudocapacitor electrodes can be exploited at the same time.29,30 Several scientists have explored a variety of graphene-based nanocomposites, transition metal (e.g, Fe, Co, and Ni)-based metal–organic framework materials, and silica-based composites for energy storage applications (such as supercapacitors, an electrode for Li-ion battery, etc.).35−40

In this paper, we report a “one pot” method to prepare nanocomposites, which are composed of varying amounts of snowflake-like dendritic CoNi alloy particles and RGO. To understand the electronic structures of CoNi alloy and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice, first-principles quantum mechanical calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) have been performed. We have evaluated the performance of CoNi alloy and CoNi-RGO nanocomposites for two different types of applications: (i) as the catalyst for the reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol and Knoevenagel condensation reaction and (ii) as the active electrode material in the supercapacitor applications. The influence of microstructures of CoNi alloy particles (spherical vs snowflake-like dendritic) and the effect of immobilization of CoNi alloy on the surface of RGO on the catalytic and supercapacitive properties have been investigated in detail. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the demonstration of the multifunctional nature of CoNi-RGO nanocomposites by showing its application as a catalyst for two different types of reactions and as an active electrode material for supercapacitors and the determination of its electronic structures and electronic properties by a DFT study have been reported.

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Formation of the Materials and Their Characterizations

Two wet chemical methods were used to prepare CoNi alloy particles. In both of these synthesis methodologies (Method-I and Method-II), CoNi alloy particles were formed due to the reduction of Co2+ and Ni2+ in alkaline medium. In Method-I, ethylene glycol and N2H4 acted as the reducing agents. The reduction of Co2+ and Ni2+ by ethylene glycol and N2H441,42 can be presented by the reactions given below (reaction 1–4)

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where M2+ = Co2+, Ni2+ .

Pure Co and Ni nanoparticles were also synthesized by employing Method-I and Method-II. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) micrographs of the synthesized materials are illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1a shows the nanometer-thin RGO sheets, and the X-ray diffraction (XRD) of pure RGO is shown in Figure S1.43Figure 1b reveals that the pure Ni particles (NiS), which were obtained from Method-I, are spherical in nature and the diameter of the spheres lies in the range of 80–100 nm. Figure S1 shows the XRD pattern of NiS. Figure 1c shows that the pure Co particles, which were synthesized by Method-II, possess a dendritic microstructure (CoD). The XRD pattern of CoD is presented in Figure S1. The FESEM micrograph (Figure 1d) of the CoNiS particles (prepared by Method-I) shows their spherical nature, and the diameter of the spheres is in the range of 230–500 nm. EDS analysis (Figure S2a) of these spheres confirms the presence of both Co and Ni in each sphere in the desired weight ratio, indicating the formation of CoNi alloy due to the simultaneous reduction of Ni2+ and Co2+. Elemental color mapping of the spheres also supports this result (Figure S2b). XRD analysis of CoNiS (Figure 1i) shows a diffraction peak at 2θ = 44.37°, which corresponds to (111) and (002) planes of Ni and Co, respectively.1 However, the weak intensity of this peak and the absence of other diffraction peaks of Co and Ni indicate the poor crystallinity of CoNiS. In Method-II, the CoNiD particles were formed from the reduction of Co2+ and Ni2+ by N2H4 (reaction 4). FESEM micrographs illustrate that CoNiD particles possess a snowflake-like dendritic microstructure (Figure 1e,f).

Figure 1.

FESEM micrographs of the synthesized materials (a) RGO, (b) NiS (Method I), (c) CoD (Method II), (d) CoNiS (Method I), (e) CoNiD (Method II), (f) enlarged micrograph of CoNiD, (g) (CoNiD)60RGO40, (h) enlarged micrograph of (CoNiD)60RGO40 showing the CoNiD particle on the surface of RGO, and (i) XRD patterns of CoNiS, CoNiD, and (CoNiD)60RGO40.

EDS analysis of CoNiD particles shows that the dendritic structure is composed of both Co and Ni (Figure S3a), and the elemental color mapping of these particles also supports this observation (Figure S3b). The XRD pattern of CoNiD (Figure 1i) shows the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 41.71°, 44.71°, 47.54°, and 76.19°, which can be assigned to (100), (002), (101), and (110) planes of CoNi alloy with the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) phase of Co.14 In this synthesis method, CTAB acts as a microstructure directing agent. According to Wu et al., CTAB controls the growth rate kinetics of (100), (110), and (010) planes of CoNi alloy and interacts with the faces via the adsorption–desorption process and facilitates the growth of the dendritic structure.14

Investigations on the catalysis property and electrochemical properties were performed for both the spherical CoNiS and dendritic CoNiD. It was observed that the CoNiD exhibited superior properties to CoNiS. For further improvement of these properties, we have synthesized CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites by using a “one pot” method where dendritic CoNiD particles were immobilized on the surface of RGO. In this method, the formation of dendritic structured CoNi alloy particles (CoNiD) and transformation of GO to RGO occur simultaneously. FESEM micrographs of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites (Figure 1g,h) reveal the presence of snowflake-like dendritic CoNiD particles on the surface of nanometer-thin RGO sheets. EDS analysis and elemental color mapping (Figure S4a,b) also confirm the immobilization of CoNiD on the RGO surface in CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites. The CoNiD particles in CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites are to some extent smaller in size in comparison with pure CoNiD particles. In the composite, the presence of RGO might have restricted the growth of the CoNiD particles. In the XRD pattern of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites (Figure 1i), the presence of diffraction peaks at 2θ = 41.71°, 44.71°, 47.54°, and 76.19° indicates the presence of CoNiD. In this XRD pattern, the absence of peaks at 2θ = 9.76° and 42.14°, which are the characteristic peaks of (001) and (101) planes of GO (Figure S5), is noticed.18 This could be due to the transformation of GO to RGO during the formation of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites. In this “one pot” methodology, the conversion of Co2+ and Ni2+ to CoNiD alloy and reduction of GO to RGO occurred simultaneously. Raman spectra of the CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite and pure GO are shown in Figure S6. The Raman spectra of GO shows that the peaks corresponding to D and G bands appear at 1342 and 1582 cm–1, respectively, whereas, for CoNiD-RGO, these bands red-shifted to 1336 and 1585 cm–1. This shifting of D and G bands in the nanocomposite can be attributed to the conversion of GO to RGO. The ID/IG ratio of the nanocomposite (ID/IG = 1.10) is greater than that of GO (ID/IG = 0.96), and this increase in ID/IG might be due to the decrease in the average size of sp2 domains upon the reduction of GO during the formation of the CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite.18

2.2. First-Principles Calculations of Electronic Structure

We have performed the first-principles quantum mechanical calculations based on DFT to understand the interfacial interactions between Co, Ni, and graphene in the CoNi alloy and Co-Ni-graphene superlattices. Geometrical optimization was performed for each system before the calculation of DOS (density of states), TDOS (total density of states), and band structure. The superlattice structures of Co, Ni, graphene, Co–Ni interface, and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice before and after full relaxation are shown in Figure S7a,b. The obtained lattice parameters for the hcp unit cell of Co are a = b = 2.50 Å and c = 4.06 Å ,and those for the fcc Ni unit cell are a = b = c = 3.52 Å. The lattice parameter values thus obtained match well with the previously reported values.44,45

In the Co-Ni-graphene superlattice, the lattice distortion is observed after relaxation with a ∼2.3% expansion in the z direction of the Co–Ni interface. In this superlattice, the binding energy between the Co–Ni interface and graphene is −3.49 eV. These results indicate the existence of strong interactions between the Co–Ni interface and graphene. The equilibrium interlayer distance between them is 2.96 Å.

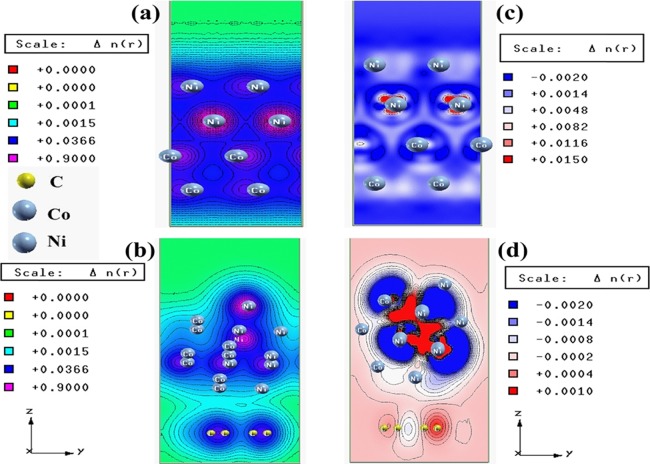

The DOS and TDOS analysis for both Co and Ni unit cells show (Figures S8 and S9) that, in both cases, the valence bands and conduction bands originated mainly from the contribution of their 3d and 3p orbitals. Figure S10 shows the contributions from Ni 3d and Co 3d in the valence band region near the Fermi level in the TDOS of the Co–Ni interface. The presence of Ni 3d and Co 3d states across the Fermi level indicates its metallic nature. In the case of Co-Ni-graphene, the TDOS (Figure S11) shows the contribution from C 2p, Ni 3d, and Co 3d orbitals across the Fermi level and the asymmetric nature of the spin up and spin down phase. These facts clearly indicate the metallic nature and the ferromagnetic nature of Co-Ni-graphene.46,47 The band structure of graphene (Figure S12) clearly shows its zero band gap nature.48 The band structures of Co, Ni, Co-Ni, and Co-Ni-graphene also indicates their metallic character. The band structure of the hcp Co unit cell (Figure S8) and fcc Ni unit cell (Figure S9) match well with the previously reported band structures.45,49,50 In the band structure of the Co–Ni interface (Figure S10), the appearance of new bands near the Fermi level in comparison with the band structures of individual Co and Ni unit cells indicates the occurrence of hybridization between 3d states of Co and Ni. In the band structure of Co-Ni-graphene (Figure S11), the appearance of new bands at both valence and conduction band regions occurs due to the hybridization between C 2p states of graphene, Ni 3d, and Co 3d states. The charge density plot and difference charge density interface and the electron plot of the Co–Ni interface and Co-Ni-graphene are shown in Figure 2a,b. In the Co–Ni interface, the density of some of the Co centers becomes relatively less in comparison with pure Co. This could be due to the orbital level interactions between Co and Ni in the interface and higher electronegativity of Ni (1.91) than that of Co (1.88). The difference charge density plot of the Co–Ni interface also shows this depletion of the electron density of Co. Figure 2c,d shows the interaction between Co–Ni, C–Ni, and C–Co in the interface in Co-Ni-graphene. These DFT calculations clearly demonstrate the existence of strong orbital level hybridization between Co, Ni, and graphene in Co-Ni-graphene. From this hybridization point of view, we can predict that the conductivity of Co-Ni-RGO nanocomposite will be higher than that of Co-Ni alloy. EIS measurements of the synthesized materials support this prediction by showing the lower Rct (charge transfer resistance) value of (CoNiD)60RGO40 (0.53 Ω) compared to CoNiD (1.61 Ω). This fact indicates that the incorporation of RGO causes the enhancement of the conductivity of the nanocomposites. The detailed discussion on the results obtained from EIS measurements is provided in Section 2.4.

Figure 2.

Charge density plots of the (a) Co–Ni interface and (b) Co–Ni graphene interface and difference charge density plot of the (c) Co–Ni interface and (d) Co–Ni graphene interface (where the red color represents charge accumulation and the blue color represents charge depletion in the difference charge density plot).

2.3. Catalysis Reactions

2.3.1. Reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP

We have performed the room temperature reduction of 4-NP in an aqueous medium in the presence of aqueous NaBH4 using the synthesized materials as catalysts. We have also performed this reaction without using any catalyst and observed that no reaction has occurred. This reaction was monitored by using UV–Vis spectroscopy. 4-NP in aqueous medium shows the maximum absorption (λmax) at 317 nm, and the addition of NaBH4 solution to 4-NP solution causes a red shift of this λmax to 400 nm due to the formation of dark yellow-colored phenolate ions.16,51,52 With the progress of the reaction, the color of 4-nitrophenolate starts to fade. With the increasing reaction time, the intensity of λmax(4-NP) at 400 nm gradually decreases. Simultaneously, a new peak at λmax = 300 nm grows, which indicates the formation of 4-aminophenol due to the reduction of 4-nitrophenol. This reduction reaction is a pseudo-first-order reaction. As a representative, time-dependent UV–Vis spectra of CoNiS-, CoNiD-, and (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed reaction are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent UV–Vis spectra of the reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol catalyzed by (a) CoNiS, (b) CoNiD, and (c) (CoNiD)60RGO40 and (d) pseudo-first-order kinetic plot of this reaction.

To understand the role of individual Co, Ni, and RGO in the CoNi-RGO catalyst, we have performed the reaction with pure RGO, NiS, CoS (spherical), and CoD (dendritic structure) (Figure S13). The induction time, reaction completion time, and the value of kapp, which were observed for the reactions catalyzed by different synthesized materials, are listed in Table S3. In the present reaction condition, pure RGO does not show any catalytic activity. The values of kapp for pure NiS- and CoS-catalyzed reactions are 2.93 × 10–3 and 2.23 × 10–3 s–1, respectively. The use of CoD as the catalyst results in a decrease in both the induction time (from 6 to 3 min) and the reaction completion time (32 to 24 min) compared to the CoS nanoparticle. kapp increases significantly due to the use of spherical CoNiS (kapp = 4.33 × 10–3 s–1) as the catalyst instead of pure Co or Ni nanoparticle. This fact clearly indicates the beneficiary effect of the use of CoNi alloy as a catalyst instead of pure Co or Ni. The influence of the microstructure of the catalyst on the reaction kinetics was investigated by performing the reaction using spherical CoNiS and snowflake-like dendritic CoNiD as the catalyst. For the CoNiD catalyst, the value of kapp (6.11 × 10–3 s–1) is higher than that of CoNiS (kapp = 4.33 × 10–3 s–1), and the reaction completion time reduces from 21 to 17 min. These results indicate that CoNiD acts as a better catalyst than CoNiS. To develop a catalyst having enhanced efficiency, we have synthesized nanocomposites by immobilizing different amounts of CoNiD on the surface of RGO. Figure S13 shows the higher catalytic activity of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites than that of CoNiD. The catalyst containing 60 wt % CoNiD and 40 wt % RGO,(CoNiD)60RGO40 exhibits the highest catalytic activity with almost no initiation time and the minimum reaction completion time of 4 min with the highest kapp of 20.55 × 10–3 s–1 (Figure 3).

The reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP is a six-electron transfer reaction.53 The metal nanoparticle-catalyzed reduction reaction of 4-NP to 4-AP proceeds via an electron transfer (ET)-induced hydrogenation mechanism. In the initial stage, BH4– ions are adsorbed on the surface of metal nanoparticles. Electron transfer from BH4– to metal nanoparticles resulted in the production of active hydrogen atoms, and these hydrogen atoms reduce 4-NP to 4-AP. Here, the metal nanoparticles act as storage of electrons after ET from BH4–.16,54 Ballauff et al. have proposed the Langmuir–Hinshelwood mechanism for the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP on Au nanoparticles55 where both the reactants were adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst before the reaction. The reconstruction of the surface of the metal nanoparticles occurs when BH4– reacts with it and forms metal-H bonds.15,56 The reaction between metal-H and adsorbed 4-NP results in the formation of 4-AP. This reaction proceeds as 4-nitrophenol → 4-nitrosophenol → 4-hydroxyaminophenol → 4-aminophenol.57 The possible mechanism of the (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed reaction of 4-nitrophenol can be schematically presented as Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Plausible mechanism for the (CoNiD)60RGO40-Catalyzed Reduction Reaction of 4-Nitrophenol in the Presence of Excess NaBH4 in an Aqueous Medium.

In the present investigation, the following important points were noted: (i) Co-Ni alloy exhibits better catalytic activity than that of individual pure Ni and pure Co. DFT calculation shows the generation of electron deficiency in Co in the Co–Ni system. These electron-deficient Co sites might act as better electron-storing sites during the electron transfer process from BH4– than pure metal nanoparticles. (ii) CoNiD with a snowflake-like dendritic structure exhibits better catalytic activity than that of spherical CoNiS. This could be due to the fact that, in CoNiD, the electron transfer occurs more efficiently via a fast ballistic charge transfer mechanism due to its well-defined sharp-edged dendritic microstructure, whereas in spherical CoNiS, the electron transfer proceeds via a relatively slow diffusion-controlled pathway. (iii) Immobilization of CoNiD on the surface of RGO enhances the catalytic activity of the catalyst. (CoNiD)60RGO40 demonstrates better catalytic efficiency than that of CoNiD. As the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP is a six-electron transfer reaction, the electrical conductivity of the catalyst plays a crucial role in this reaction. The EIS measurements of the catalysts clearly show that the conductivity of (CoNiD)60RGO40 is higher than that of CoNiD. DFT calculation also shows the existence of orbital level hybridization in the interface between Co, Ni, and C in the Co–Ni graphene system. Due to this orbital level hybridization between Co–Ni, Co–C, and Ni–C, the conductivity of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite becomes higher than that of CoNiD. Due to this enhanced conductivity, the electron transfer process occurs more efficiently in the RGO-containing catalysts, and they show greater catalytic activity. Moreover, (CoNiD)60RGO40 possesses a high adsorption capacity of 4-NP.18 According to Rout et al., the strong adsorption of 4-NP on the surface of RGO causes stretching of the N=O bond of the −NO2 group of 4-NP (from 1.23 to 1.28 Å), and this stretching of bond activates −NO2 for the reduction reaction.58 These factors enhance the catalytic efficiency of (CoNiD)60RGO40 toward the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP.

2.3.2. Knoevenagel Reaction

As the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite exhibits the highest catalytic activity amongst the synthesized materials toward the reduction of 4-nitrophenol to 4-aminophenol, we have explored the utilization of this nanocomposite as a catalyst for the Knoevenagel condensation reaction. Here, we have performed the condensation of an aromatic aldehyde with ethyl cyanoacetate in ethanol medium in the presence of (CoNiD)60RGO40. To validate the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite as a catalyst for this reaction, we have used several aromatic aldehydes with different substitutions in the −Ph ring and obtained ∼80–93% product yield depending upon the aldehyde. In Table 1, the percentages of the yield of the obtained products are listed. The purity and chemical structures of the obtained products were verified by using FTIR, DSC (for melting point determination), LC–MS, and 1H NMR analysis (Figures S14–S17).21,28

Table 1. (CoNiD)60RGO40-Catalyzed Knoevenagel Condensation Reaction of an Aromatic Aldehyde and Ethyl Cyanoacetatea.

Reaction condition: 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (1 mmol), ethyl cyanoacetate (1.2 mmol), ethanol (4 mL), catalyst dose (25 mg), reaction temperature: 50 °C, reaction time: 12 h.

A plausible mechanism for the Knoevenagel condensation reaction is presented in Scheme 2 on the basis of reported mechanisms.21,23,59 The CoNi alloy nanoparticles act as the catalytically active centers in the catalyst. A DFT study shows that the interfacial interactions between Co, Ni, and RGO in the Co-Ni-RGO interface generate electron-deficient Co centers. The interaction between the carbonyl group of the aromatic aldehyde and Co causes the polarization of this group and the electrophilic character of the carbonyl carbon atom increases. This polarization helps in the attack of methylene carbon of ethyl cyanoacetate to the carbonyl carbon of the aromatic aldehyde. The cyano group of ethyl cyanoacetate also interacts with Co, which enhances the acidity of methylene carbon of ethyl cyanoacetate and helps in the formation of nucleophilic species via deprotonation of methylene carbon of ethyl cyanoacetate. The attack of this nucleophilic carbon to the carbonyl carbon of aromatic aldehyde results in the formation of a new C–C bond. In the protic solvent, this intermediate dissociates from the catalyst. Dehydration of this intermediate generates the final product, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound. In the present catalyst (CoNiD)60RGO40, the presence of RGO offers the following advantages: (i) nanometer-thin RGO sheets provide a strong but mechanically flexible support to host the catalytically active centers (i.e., CoNiD), (ii) immobilization of CoNiD nanoparticles on the surface of RGO helps to prevent their agglomeration, therefore the reactant molecules get better accessibility to the catalytically active sites, (iii) the high surface area of RGO helps to absorb the reactant molecules on the surface of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 catalyst via π–π stacking interaction, and (iv) the conducting nature of the RGO support enhances the electron transfer process of the catalysis reactions.

Scheme 2. Plausible Mechanism for the (CoNiD)60RGO40-Catalyzed Knoevenagel Condensation Reaction of an Aromatic Aldehyde and Ethyl Cyanoacetate in Ethanol Medium.

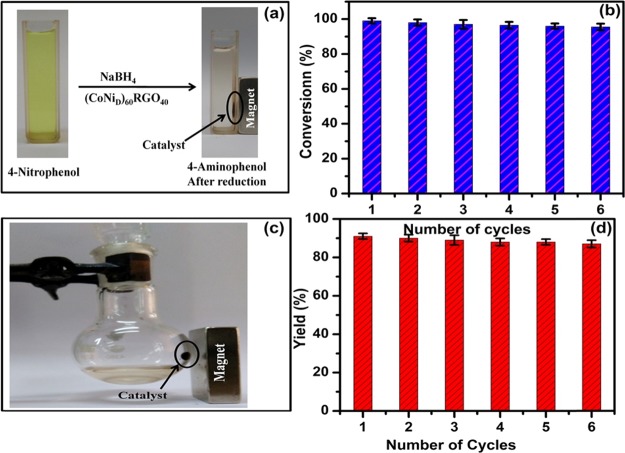

2.3.3. Magnetic Separation and Reusability Test of the Catalyst

A VSM was used to determine the magnetic property of (CoNiD)60RGO40, which shows its saturation magnetization (Ms) and coercivity (Hc) values are 65 emu g–1 and 300 Oe (Figure S18), respectively. By exploiting the magnetic character of this catalyst, its separation from the reaction mixture was conducted by using a permanent magnet externally (Figure 4a,c). To test the reusability of the catalyst, we have recycled the catalyst up to six reaction cycles. Figure 4b,d demonstrates that the recovered catalyst retains almost the same efficiency even up to the six cycles. The examination of the recovered catalyst by XRD and FESEM shows no significant change in its crystal structure and microstructure (Figure S19) and indicates the structural robustness of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 catalyst.

Figure 4.

Magnetic separation of (CoNiD)60RGO40 catalyst from the reaction mixture and performance of recycles catalyst for (a, b) reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol and (c, d) Knoevenagel condensation reaction.

2.4. Electrochemical Properties

As (CoNiD)60RGO40 demonstrated its efficient performance as a catalyst, we have now explored the capability of this nanocomposite as an active electrode material for the supercapacitor application. To evaluate the electrochemical properties of the synthesized nanocomposites, CV and GCD measurements were performed. CV measurements were conducted to understand the electrochemical reactions, which are occurring on the surface of the electrodes in the presence of aqueous 3 M KOH solution as the electrolyte. To investigate the effect of microstructure of the active electrode materials on their electrochemical properties, working electrodes were prepared with CoNiS and CoNiD. The electrochemical reactions of Co and Ni in the alkaline medium have been investigated by several researchers and several reactions have been proposed, and reactions can be presented as follows:60−63

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

According to Behl and Toni, during the electro-oxidation reaction of Co in the KOH medium, a thin film of Co(OH)2 forms on the surface of Co, which is subsequently oxidized to Co3O4 and CoOOH.61 In the case of Ni, the formation of Ni(OH)2 and NiOOH occurs during the electro-oxidation process.62,63

In the present case, the CV curves of CoNiS and CoNiD show a distinct pair of redox peaks within the potential window of 0–0.55 V versus Hg/HgO, and the anodic peak appears at ∼0.38 V and the cathodic peak at ∼ 0.30 V (Figure 5). The redox peaks around this potential range can be attributed to the conversion of Ni2+/Co2+ to Ni3+/Co3+, and the corresponding electrochemical reactions can be presented as reactions 7 and 9.64 The identical nature of anodic and cathodic peaks indicates the reversibility of the electrochemical process.65 The presence of distinct redox peaks in CoNiS and CoNiD electrodes within the potential window of 0–0.55 V versus Hg/HgO indicates the faradic behavior (i.e., pseudocapacitive) of these electrodes in the electrochemical process. Comparison of the CV profiles of pure Co and pure Ni (Figure S20) with that of CoNi alloy shows that the redox peaks for the pure Co and pure Ni electrodes appear at ∼0.38/0.30 V and 0.50/0.32 V, respectively, and in the case of CoNi alloy, overlapping of these redox peaks causes the broadening of the oxidation and reduction peak.62Figure 5 shows that the area under the CV curve for CoNiD is larger than that of CoNiS and indicates that the specific capacitance of CoNiD is greater than that of CoNiS. This could be due to the difference in the microstructure between CoNiD and CoNiS. The sharp-edged dendritic structure of CoNiD offers more active sites for the electrochemical reactions and better electron transfer ability to the electron collector.66Figure S21 presents the CV profile of pure RGO, and the quasi-rectangular shape of this CV curve indicates the EDLC feature of RGO.67Figure 5a also illustrates that the peak area under the CV curve of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite is even larger than that of CoNiD, demonstrating the higher specific capacitance of (CoNiD)60 RGO40 than that of CoNiD. The redox peaks of (CoNiD)60RGO40 appear almost in the same positions, where they appear for CoNiD. This fact indicates that the electrochemical reactions, which are happening for the CoNiD electrode, are also occurring for (CoNiD)60RGO40. The CV curves of the electrodes, which were measured at different scan rates (10–100 mV s–1), are presented in Figures S22–S24, which shows the effect of the increase in scan rate on the peak potential and the peak current. With the increase in scan rate, the shifting of the anodic and cathodic peaks toward anodic and cathodic directions, respectively, can be observed in these CV profiles. This could be due to the development of an overpotential, which limited the faradic reactions occurring on the surface of the electrodes. The increase in peak current with increasing scan rate indicates the excellent rate capability of electrode materials.30,68 The Randles–Sevcik plots of the electrodes are shown in Figure 5b, which shows a linear increase in peak current with the progressive increase in scan rate. This could be due to the influence of scan rate on the migration and diffusion of electrolytic ions into the electrode.

Figure 5.

(a) CV curves of the synthesized materials at 10 mV s–1 in 3 M KOH and (b) Randles–Sevcik plots.

When the scan rate is relatively low, a thick diffusion layer of ions forms on the surface of the electrode, which restricts the migration of electrolyte ions into the electrode and resulted in the lowering of peak current. On the other hand, at a relatively high scan rate, this diffusion layer cannot grow on the electrode surface. Therefore, the migration of ion increases into the electrodes and ultimately enhances the peak current.69 The specific capacitance (Cs) values of the electrodes were calculated from the GCD curves of CoNiS (Figure S25), CoNiD (Figure 6a), and (CoNiD)60RGO40 (Figure 6b) at different current densities from 1 to 10 A g–1 under an applied potential between 0 and 0.55 V. In 3 M KOH, CoNiS, CoNiD, and (CoNiD)60RGO40 shows the Cs values of 89, 130, and 278 F g–1, respectively, at a current density of 1 A g–1. The dendritic CoNiD possesses higher Cs than that of spherical CoNiS, and the Cs value has further increased when CoNiD nanoparticles are immobilized on RGO in (CoNiD)60RGO40. The synergistic effect arising from the combination of the EDLC nature of RGO and the pseudocapacitance feature of CoNiD are responsible for the outstanding performance of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite. The energy density (E) and power density (P) of the electrodes were determined from the GCD. CoNiS, CoNiD, and (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrodes exhibit the energy densities of 3.74, 5.5, and 11.68 Wh kg–1, respectively, at a power density of 275 W kg–1 in 3 M KOH, and a decreasing trend of energy density value with increasing power density. Figure S26a (Ragone Plot) illustrates this decrease in energy density with increasing power density. The cyclic behavior of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode was evaluated at a constant current density of 7 A g–1 within a potential window of 0–0.55 V in 3 M KOH and presented as Figure S26b, which shows the retention of ∼85% capacitance up to 4000 cycles. The XRD pattern and FESEM micrograph of (CoNiD)60RGO40 after charge–discharge cycles exhibit the almost retention of its crystalline phase and microstructure (Figure S27), indicating its structural stability.

Figure 6.

Galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of (a) CoNiD and (b) (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrodes at different current densities (1–10 A g–1) in 3 M KOH in a three-electrode system.

The addition of a complementary redox couple with matching potential (e.g., [Fe(CN)6]4–/[Fe(CN)6]3– (0.20/0.37 V)) in the electrolyte system has been adopted by the researchers to enhance the specific capacitance of the electrode.70 We have added 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] aqueous solution to the 3 M KOH solution. In this condition, along with the faradic reactions of Co and Ni, an additional redox reaction, which is offered by [Fe(CN)6]4–/[Fe(CN)6]3–, occurs. Figure 7a shows the CV curves of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode when measurements were conducted with 3 M KOH and 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] mixture. The CV curves clearly show that the addition 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] in 3 M KOH electrolyte solution causes the increase in the area under the CV curve and indicates the enhancement of Cs. The [Fe(CN)6]4–/[Fe(CN)6]3– redox couple acts as an electron buffer source in the redox reactions at the electrode/electrolyte interface, which enhances the specific capacitance. The addition of 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] to 3 M KOH electrolyte solution results in the increase in Cs of (CoNiD)60RGO40 to 501 F g–1 at a current density of 6 A g–1 (Figure 7b). This value of Cs decreases to 334 F g–1 when the current density increases to 20 A g–1 showing ∼66.7% retention of Cs and indicates its good rate capability. In this electrolyte system, the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite exhibits an energy density of 21.08 Wh kg–1 at a power density of 1650 W kg–1. Figure S28a presents the Ragone plot, which shows the decrease in energy density up to 14.05 Wh kg–1 when the power density increases to 5500 W kg–1. Figure S28b demonstrates the cyclic behavior of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 and shows the retention of ∼85% capacitance after 4000 cycles when the testing was performed at a current density of 7 A g–1.

Figure 7.

(a) CV curves of (CoNiD)60RGO40 at 10 mV s–1 in 3 M KOH electrolyte and 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte. (b) GCD curves of (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte.

To mimic a supercapacitor device, a two-electrode symmetric cell was devised using (CoNiD)60RGO40 as an electrode material though it is a well-known fact that two-electrode systems show a lower Cs value than that of a three-electrode system.71 The reason for the lower capacitance value in the case of the two-electrode system as compared to the three-electrode system is due to the difference in the packaging and configuration of the cells. In a three-electrode system, only one working electrode contains the active material being analyzed, whereas in the case of a two-electrode system, two symmetric working electrodes where both the electrodes contain the active material are used, which leads to a difference in the applied voltage and charge transfer across a single electrode in comparison to two electrodes.72 Also, in a symmetrical two-electrode cell, the potential differences applied to each electrode are equal to each other and are one-half of the values of the applied voltage potential.72 CV and GCD measurements of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode in a two-electrode symmetric system to choose the appropriate operating potential window measurements were conducted using different potential windows at a scan rate of 10 mV s–1, and it was observed that a stable voltammogram was obtained when the operating window was 0–0.8 V.73Figure 8 shows the CV profile and GCD plot of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode when measurements were conducted in the two-electrode system using 3 M KOH, and 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte solutions in a potential window of 0–0.8 V. The Cs values thus obtained are 125 F g–1 at a current density of 1 A g–1 in 3 M KOH and 405 F g–1 at a current density of 3 A g–1 in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6]. Figure S29 presents the specific capacitance and Coulombic efficiency of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode as a function of current density in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte solution. It was observed that, though the specific capacitance of the electrode is decreased with increasing current density, the Coulombic efficiency is found to be increased from 50 to 90% when the current density is increased from 3 to 10 A g–1.74−78 (CoNiD)60RGO40 also exhibits the value of energy density of 9 Wh kg–1 when the power density is 1200 W kg–1in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] and energy density decreases with increasing power density. The energy density becomes 4 Wh kg–1 when the power density is 8000 W kg–1.

Figure 8.

(a, b) GCD curves of (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode in (a) 3 M KOH electrolyte and (b) 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte. (c) CV curves of (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode at 10 mV s–1 in 3 M KOH and 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte in a two-electrode symmetric cell system.

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed for the synthesized materials to determine their charge transfer resistance (Rct) and internal resistance (Rs). Nyquist plots were generated, and an equivalent circuit was constructed to fit the impedance data. In the Nyquist plot, the intercept of Z′ (real axis) in the high-frequency region provides the value of Rs. The combination of the following effects is the origin of Rs: (i) the contact resistance between the electrode material and the current collector, (ii) the intrinsic resistance of the electrode materials, and (iii) the ionic resistance of the electrolyte.79 In the Nyquist plot, the diameter of the semicircle at the intermediate frequency range indicates the value of Rct, and Rct indicates the faradic pseudocapacitance of the electrode materials. The Nyquist plots of the synthesized materials are shown in Figure 9a, and Rct and Rs values are listed in Table S3. EIS analysis revealed that (i) Rct and Rs values of CoNiD are lower than those of spherical CoNi, (ii) immobilization of CoNiD on the surface of RGO causes a further decrease in Rct and Rs values, and (iii) Rct and Rs values of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite are lower than those of pure RGO. This could be due to the fact that the charge transfer occurs more efficiently in CoNiD because of its well-defined sharp-edged dendritic structure. In this case, the charge transfer occurs via a ballistic charge transport mechanism, which is faster than that of a diffusive transport mechanism that occurs in spherical CoNiS, (iv) the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite possesses higher conductivity than that of pure RGO and CoNiD. In the nanocomposite, CoNiD nanoparticles are in close contact with RGO. Strong interfacial interaction between CoNiD and electron-rich RGO provides a shorter transport path to the electrons, which helps to enhance the conductivity of the CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite.

Figure 9.

(a) Electrochemical impedance spectra of the synthesized materials, and the insets show the high-frequency region and equivalent circuit used for the fitting of Nyquist plot. (b) |Z| versus frequency plot, (c) Phase angle versus frequency plots.

To understand the capacitive behavior and determine the “knee frequency”, Bode plots were generated by plotting |Z| versus frequency (Figure 9b) and phase angle versus frequency (Figure 9c). In the |Z| versus frequency plots, the materials with a higher conductivity show relatively lower |Z| value at the low frequency. Figure 9b shows a lower |Z| value of CoNiD (|Z| = 32.48 Ω) than that of CoNiS (|Z| = 38.91 Ω), indicating the higher conductivity of CoNiD. (CoNiD)60RGO40 (|Z| = 24.56 Ω) also shows a lower |Z| value than that of pure RGO (|Z|= 31.14 Ω) and CoNiD, which also indicates the enhanced conducting nature of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite compared to CoNiD and RGO.

In the phase angle versus frequency plot, the phase angle of 90° in the low frequency suggests the ideal capacitive behavior of the electrode, and the phase angle of 0° indicated the pure resistance behavior.80,81 The knee frequency (fo) is the frequency at the phase angle of 45°, and in this frequency, the capacitive and resistive impedance are equal. In Figure 9c, the higher fo value of (CoNiD)60RGO40 compared to CoNiS and CoNiD indicates the high rate capability of this nanocomposite. The higher relaxation time (τ = fo–1) of (CoNiD)60RGO40 (4.1 × 10–3 s) than those of CoNiS (7.3 × 10–3 s) and CoNiD (5.7 × 10–3 s) indicates that, in the nanocomposite, the immobilization of dendritic CoNiD particles on the surface of RGO creates shorter ion transport paths, which helps to increase its electrical conductivity by decreasing the internal resistance. The enhanced conductivity of (CoNiD)60RGO40 is one of the important factors that are responsible for its superior supercapacitive nature than CoNiS or CoNiD.

Investigation of the electrochemical properties of the synthesized materials revealed that the Cs value of CoNiD is greater than that of CoNiS and this value further increases when (CoNiD)60RGO40 is used as an electrode material. (CoNiD)60RGO40 shows a Cs of 501 F g–1 at a current density of 6 A g–1 along with the good retention of the capacitance and rate capability property. It also possesses an energy density of 21.08 Wh kg–1 at a power density of 1650 W kg–1 in a three-electrode system and an energy density of 9 Wh kg–1 when the power density is 1200 W kg–1 in a two-electrode symmetric system, which are comparable to the commercial supercapacitors (3–9 Wh kg–1 at 3000–10,000 W kg–1).30,82Figure 10 shows the illumination of seven red LED bulbs when three pair of electrodes were connected in series to construct the two-electrode system. The illumination of seven red LED bulbs for over 3 min demonstrates the potential of (CoNiD)60RGO40 to be used as an active electrode material for the construction of a supercapacitor.

Figure 10.

Demonstration of the lighting of a series of red light-emitting diode (LED; 3 V each) powered by three (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrodes connected in series. (a–d) Glowing LEDs at different time intervals.

3. Conclusions

We have reported a simple “one-pot” methodology to synthesize snowflake-like dendritic CoNi alloy-RGO nanocomposites. The effect of microstructure on the catalytic property and the electrochemical property of CoNi alloy has been demonstrated here. Compared to spherical CoNiS, snowflake-like dendritic structure CoNiD has exhibited better performance as a catalyst for the reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol and Knoevenagel reaction and as an active electrode material for supercapacitor applications. The nanocomposite that was prepared by immobilizing (60 wt %) CoNiD on the surface of RGO (40 wt %) showed superior performance in the aforesaid applications than CoNiD and CoNiS. The synergistic effect, which arises from the coexistence of CoNiD and RGO in the hierarchical structure of the CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite, is responsible for its superior performance than the individual components. First-principles calculations based on DFT provided insight into the interfacial interactions between Co, Ni, and graphene in the Co-Ni-graphene superlattice. The obtained electronic structures of the Co–Ni interface and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice were helpful to understand why CoNi alloy showed better performance than that of pure Co and Ni and why the CoNi-RGO nanocomposite did exhibit improved properties compared to CoNi alloy. (CoNiD)60RGO40 demonstrated its multifunctional character by exhibiting its high efficiency as a magnetically separable catalyst for two important reactions and as an excellent electrode material for high-performance supercapacitors. The kapp value for the (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol is 20.55 × 10–3 s–1, which is comparable and, in some cases, superior to many RGO-based catalysts. The % yield of the products obtained for the (CoNiD)60RGO40-catalyzed Knoevenagel condensation reaction between several aromatic aldehydes and ethyl cyanoacetate lies in the range of 80–93%. In addition to showing this versatile catalytic activity, (CoNiD)60RGO40 also offers an advantage of its easy magnetic separation by the use of an external magnet. This overcomes the separation-related limitations that many nanostructured catalysts encounter. The recycled catalysts also showed satisfactory performance. The specific capacitance value of (CoNiD)60RGO40 was 501 F g–1 at a current density of 6 A g–1. Along with good rate capability and ∼85% retention of capacitance, it also exhibited 21.08 Wh kg–1 energy density at a power density of 1650 W kg–1. These results indicate that (CoNiD)60RGO40 could be considered as a favorable electrode material for the construction of high-performance supercapacitors. The easy synthetic methodology, high catalytic efficiency, and excellent supercapacitance performance make (CoNiD)60RGO40 an appealing multifunctional material.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Synthesis of Materials

Two wet chemical methods have been used to prepare CoNi alloy particles possessing two distinct types of morphology. These two methods were also used to prepare pure Co and pure Ni nanoparticles. A simple but novel “one-pot” method was employed to prepare CoNi-RGO nanocomposites.

4.1.1. Method-I: Synthesis of Spherical CoNi Alloy Particles (CoNiS)

In this method, a calculated amount of CoCl2·6H2O and NiCl2·6H2O was dissolved in a mixture of ethylene glycol and polyvinylpyrrolidone (molar ratio 2:1). To this mixture, NaOH pellets were dissolved till the pH of the solution became ∼10 and then N2H4 was added to it (metal ion/N2H4 molar ratio 1:40). This reaction mixture was refluxed at 85 °C for 15 min. After cooling it at room temperature, the precipitate thus formed was separated, washed, and dried. As the alloy particles, which were formed in this method were spherical in shape, now onward, we will refer them as CoNiS.

4.1.2. Method-II: Synthesis of Dendritic CoNi Alloy Particles (CoNiD)

In this methodology, a coprecipitation-reduction technique was used in the presence of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB).14 CoNi alloy particles were synthesized by using CoCl2·6H2O and NiCl2·6H2O (molar ratio 2:1) as starting materials. The metal chloride salts were mixed with a solution of CTAB (0.1 mmol) in ethanol. After stirring this mixture thoroughly, it was heated at 55 °C, and then a solution containing NaOH and N2H4 was added to it. This reaction mixture was refluxed for 30 min at 55 °C. The black precipitate thus formed was separated, washed with distilled water, and dried. As the FESEM micrograph of these particles revealed their snowflake-like dendritic structure, now onward, these CoNi alloy particles will be referred to as CoNiD.

4.1.3. Synthesis of CoNiD-RGO Nanocomposites

A “one-pot” synthetic methodology was employed to prepare the CoNiD-RGO nanocomposites having a different amount of CoNiD and RGO. First, graphene oxide (GO) was prepared by using a modified Hummers method.83 Then, in a round-bottom flask, a calculated amount of GO was dispersed in a mixture of ethanol and CTAB. In this mixture, an appropriate amount of CoCl2·6H2O and NiCl2·6H2O (molar ratio 2:1) was added. This mixture was heated at 55 °C with continuous stirring. A solution containing NaOH and N2H4 was added to it dropwise, and then it was refluxed at 55 °C for 30 min. After reflux, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool down at room temperature. The precipitate thus formed was separated, washed, and finally dried at 60 °C. The flow chart for the synthesis of CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite is presented as Scheme 3.

Scheme 3. Schematic Presentation of the Synthesis of (CoNiD)-RGO.

4.2. Catalytic Activity Tests

4.2.1. Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol to 4-Aminophenol

For evaluating the catalytic property of the as-prepared catalysts, the reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) to 4-aminophenol (4-AP) was conducted in the presence of excess NaBH4 in an aqueous medium. In a typical run, 4.5 mL of 9 × 10–2 mM aqueous solution of 4-NP was mixed with 0.5 mL of H2O and 1 mL of 0.2 M NaBH4 solution followed by the addition of a 2 mL aqueous suspension of the catalyst (0.1 g L–1). Four milliliters of this mixture was transferred immediately in a quartz cuvette, and the absorbance spectra of the solution were recorded using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at an interval of 1 min. The progress of the reduction reaction of the 4-NP was monitored by following the decrease in the intensity of the λmax peak at 400 nm of the 4-NP with time. In the reaction, the concentration of NaBH4 was in excess, and it remained almost constant throughout the reaction. It is a well-proven fact that, in the aqueous medium, the nanoparticle-catalyzed reduction reaction of 4-nitrophenol in the presence of excess NaBH4 follows the pseudo-first-order kinetics.16,53 As the absorbance of 4-NP at λmax is proportional to its concentration, the ratio of the absorbance of 4-NP At (measured at time t) to A0 (at t = 0) is equal to Ct/C0 (where C0 is the initial concentration and Ct is the concentration at time t of 4-NP). The apparent rate constant (kapp) was determined using the following equations:

| 10 |

| 11 |

The value of kapp was calculated from the slope of the ln(At/A0) versus time plot.

4.2.2. Knoevenagel Condensation Reaction

Different aromatic aldehydes and ethyl cyanoacetate were used as starting materials. In a typical reaction, an aldehyde and ethyl cyanoacetate (1:1 molar ratio) were dissolved in 4 mL of ethanol in a round-bottom flask. To this reaction mixture, 25 mg of catalyst was added and refluxed at 50 °C for 12 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored by using thin layer chromatography (TLC).

After completion of the reaction, the catalyst was separated with the help of an external magnet, and ethanol was evaporated from the reaction mixture. Ten milliliters of ethyl acetate was added to it, and the product was obtained by crystallization. The product was further purified by column chromatography using a mixture of ethyl acetate and petroleum ether as the eluent.

4.2.3. Recycling of the Catalyst

After each reaction cycle, the catalyst was recovered from the reaction mixture by applying the magnetic separation technique using a permanent magnet (N35 grade NdFeB magnet having an energy product BHmax = 33–36 MGOe) externally. After separation, the recovered catalyst was washed with distilled water and ethanol. Then, the catalyst was dried and used for the next reaction cycle.

4.3. Electrochemical Testing

To determine the electrochemical properties of the synthesized materials, cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements were performed by using a three-electrode system. The synthesized materials (e.g., CoNiS, CoNiD, pure RGO, and CoNiD-RGO nanocomposite) were used as active electrode materials for the fabrication of working electrodes. To prepare the working electrodes, a viscous paste was prepared by mixing 10 wt % poly(vinylidene fluoride), 10 wt % acetylene black, and 80 wt % active material in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone. This paste was cast on (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm) nickel foam (thickness, ∼0.2 mm). After casting the electrode material, the residual solvent was removed from the electrode by drying the electrode at 60 °C for 24 h in a vacuum oven. In the working electrode, the weight of the active materials was ∼3 mg. A double junction Hg/HgO electrode was used as the reference electrode and a gold electrode as the counter electrode. The electrochemical measurements were performed in two electrolytes: (i) 3 M KOH aqueous solution and (ii) a mixture of 3 M KOH and 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6]. All the CV measurements were recorded using a potential window of 0–0.55 V at different scan rates ranging from 10 to 100 mV s–1. Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements were performed at different current densities ranging from 1 to 20 A g–1. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out in the frequency range of 0.01–10,000 Hz at an open circuit potential with an alternating current amplitude of 0.01 V.

Specific capacitance (Cs), energy density (E), and power density (P) of the synthesized materials were determined from the GCD measurements by using the following equations

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

where i (A) represents the charge or discharge current, ΔE (V) is the applied potential window, m (g) is the mass of the active electrode material, Δt (s) is the discharge time, E is the energy density (Wh kg–1), Cs (F g–1) is the specific capacitance based on the mass of the electroactive material, V is the potential window of discharge (V), P is the power density (W kg–1), and Δt is the discharge time (s).

Coulombic efficiency of the synthesized material was calculated by using the following equation

| 15 |

where η is the Coulombic efficiency, tD is the discharging time (s), and tC is the charging time (s).

The synthesized materials were characterized by using an X-ray diffractometer, field emission scanning electron microscope, Raman spectrometer, and vibrating sample Magnetometer (VSM). UV–Vis spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), and 1H NMR were used to monitor the catalysis reactions and characterize the products obtained from these reactions. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was used to study the electrochemical properties of the synthesized materials. Details of the chemicals and the instruments used for this purpose are provided in the Supporting Information.

4.4. First-Principles Calculations

To perceive the electronic structures of Co unit cell, Ni unit cell, Co–Ni interface, and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice, we have conducted the first-principles quantum mechanical calculations based on DFT. Quantum ESPRESSO computational package51,84 was used to calculate the ground-state structures, binding energy, density of states (DOS), projected density of states (PDOS), and total density of state (TDOS) using a plane-wave set and pseudopotentials.51,84 DFT was used with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) and parameterized by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE).85 Kohn–Sham orbitals were expanded in a plane-wave basis set up to the kinetic energy cutoff 30 Ry (408.17 eV). The convergence criterion for the self-consistent calculation was 10–7 Ry per Bohr (0.0257 eV Å–1). For calculating the final electronic properties of the structures, an empirical dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT-D2) approach, which was proposed by Grimme, was employed.53,86 Grimme-D2 corrections were used to account for the intermolecular interactions and van der Waals (vdW) interactions.86

In the present study, five systems were investigated: (i) pure Co having a hexagonal close packing structure (space group P63/mmc), (ii) pure Ni having a face-centered cubic structure (space group Fm3̅m), (iii) graphene superlattice, (iv) Co–Ni interface, and (v) Co-Ni-graphene superlattice. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials for these systems were constructed by using 15, 16, and 4 electrons for Co (3p63d74s2), Ni (3p63d84s2), and C (2s22p2), respectively. From the Quantum ESPRESSO website, the pseudopotentials of Co, Ni, and C were chosen.87 To select the k-point mesh, the Monkhorst–Pack approach88 was used, and the details of k points for each system are provided in the Computational details section in the Supporting Information. The Brillouin zone integration of these systems was performed with Methfessel–Paxton smearing technique89 for Co and Ni unit cells. The Marzari–Vanderbilt90 smearing technique was used for graphene, Co–Ni interface, and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice. Here, the smearing parameter was 0.005 Ry. The binding energy of the Co-Ni-graphene superlattice was calculated from the difference between the total energy of the Co-Ni-graphene superlattice and the sum of each system alone (Co-Ni interface and graphene). The sizes of the unit cells of the simulated systems are listed in Table S4. The details of the sample input files for the geometric optimization of Co, Ni, graphene, Co–Ni, and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice are provided in the Computational details section in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

N.N.G. is thankful to the Central Sophisticated Instrumentation Facility (CSIF) of BITS Pilani K K Birla Goa campus for providing the FESEM facility.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b02861.

(Table S1) Comparison of the catalytic efficiency of different reported catalysts for the reduction reaction of 4-NP in the presence of NaBH4; (Figure S1) XRD pattern of RGO, pure CoD, and NiS; (Figure S2a) EDS spectra of synthesized CoNiS nanocomposites; (Figure S2b) FESEM micrographs and elemental color mapping of synthesized CoNiS nanocomposites; (Figure S3a) EDS spectra of synthesized CoNiD nanocomposites; (Figure S3b) FESEM micrographs and elemental color mapping of synthesized CoNiD nanocomposites; (Figure S4a) EDS spectra of synthesized (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposites; (Figure S4b) FESEM micrographs and elemental color mapping of synthesized (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposites; (Figure S5) room temperature wide-angle powder XRD pattern of GO; (Figure S6) Raman spectra of GO and the (CoNiD)60RGO40 nanocomposite; (Figure S7a) the initial structure of Co unit cell, Ni unit cell, Co–Ni interface, Co-Ni-graphene superlattice, and graphene; (Figure S7b) the optimized structure of Co unit cell, Ni unit cell, Co–Ni interface, Co-Ni-graphene superlattice, and (e) graphene; (Figure S8) the band structure and density of states of Co unit cell; (Figure S9) the band structure and density of states of Ni unit cell; (Figure S10) the band structure and density of states of Co–Ni interface; (Figure S11) the band structure and density of states of Co-Ni-graphene superlattice; (Figure S12) the band structure and density of states of graphene; (Figure S13) time-dependent UV–Vis spectral changes of the reaction mixture of 4-NP catalyzed by NiS, CoS, CoD, (CoNiD)90RGO10, (CoNiD)80RGO20, (CoNiD)70RGO30, (CoNiD)50RGO50, and (CoNiD)40RGO60, pseudo-first-order kinetic plot of 4-NP reduction reaction with pure NiS, CoS, CoD, (CoNiD)90RGO10, (CoNiD)80RGO20, (CoNiD)70RGO30, (CoNiD)50RGO50 and (CoNiD)40RGO60; (Table S2) details of completion time and rate constant of the synthesized catalyst for reduction of 4-nitrophenol in the presence of NaBH4; product of Knoevenagel condensation reaction (Table 1); (Figure S14) FTIR spectra of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-phenyl acrylate, (E)-ethyl 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(p-tolyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylate, and (E)-ethyl 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S15) DSC of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-phenylacrylate, (E)-ethyl 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(p-tolyl)acrylate, (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylate, and (E)-ethyl 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S16a) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-phenylacrylate; (Figure S16b) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S16c) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylate; (Figure S16d) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)acrylate; (Figure S16e) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(p-tolyl)acrylate; (Figure S16f) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylate; (Figure S16g) LC–MS full scan of (E)-ethyl 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S17a) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-phenylacrylate; (Figure S17b) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S17c) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylate; (Figure S17d) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(p-tolyl)acrylate; (Figure S17e) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)acrylate; (Figure S17f) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 2-cyano-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylate; (Figure S17g) 1H NMR spectrum of (E)-ethyl 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-cyanoacrylate; (Figure S18) room temperature magnetic hysteresis loop of (CoNiD)60RGO40; (Figure S19) FESEM images and XRD of the recycled (CoNiD)60RGO40 catalyst; (Figure S20) cyclic voltammetry curves of pure Co and pure Ni electrodes at different scan rates in 3 M KOH electrolyte; (Figure S21) cyclic voltammetry curve of RGO in 3 M KOH in the three-electrode system; (Figure S22) cyclic voltammetry curves of CoNiS in 3 M KOH at different scanning rates (10–100 mV s–1); (Figure S23) cyclic voltammetry curves of CoNiD in 3 M KOH at different scanning rates (10–100 mV s–1); (Figure S24) cyclic voltammetry curves of CoNiD)60RGO40 in 3 M KOH at different scanning rates (10–100 mV s–1); (Figure S25) Galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of CoNiS electrodes at different current densities (1–10 A g–1) in 3 M KOH in a three-electrode system; (Figure S26) Ragone plots of CoNiS, CoNiD, and (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrodes and cyclic stability of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode in 3 M KOH showing the capacitance retention after 4000 cycles using a charge–discharge at a constant current density of 7 A g–1; (Figure S27) XRD pattern and SEM micrograph of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode after charge–discharge cycles; (Figure S28) Ragone plots of (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrodes in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] and cyclic stability of the (CoNiD)60RGO40 electrode in 3 M KOH + 0.1 M K4[Fe(CN)6] showing the capacitance retention after 4000 cycles using a charge–discharge at a constant current density of 7 A g–1; (Figure S29) a plot of Coulombic efficiency and specific capacitance of (CoNiD)60RGO40 as a function of current density; (Table S3) fitting results of the EIS data of all the synthesized nanocomposites; Materials, Characterization and Instrumentation, and Computational details sections; (Table S4) the sizes of the unit cells of simulated systems; and details of the input files for geometric optimization of the Co unit cell, Ni unit cell, graphene superlattice, Co–Ni interface, and Co-Ni-graphene superlattice (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rashid M. H.; Raula M.; Mandal T. K. Polymer assisted synthesis of chain-like cobalt-nickel alloy nanostructures: magnetically recoverable and reusable catalysts with high activities. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 4904–4917. 10.1039/c0jm03047c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kady M. F.; Shao Y.; Kaner R. B. Graphene for batteries, supercapacitors and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16033. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu B.; Xing M.; Zhang J. Recent advances in three-dimensional graphene based materials for catalysis applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2165–2216. 10.1039/C7CS00904F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller M. D.; Park S.; Zhu Y.; An J.; Ruoff R. S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3498–3502. 10.1021/nl802558y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra D.; Chandel M.; Ghosh B. K.; Jani R. K.; Patra M. K.; Vadera S. R.; Ghosh N. N. A simple ‘in situ’ co-precipitation method for the preparation of multifunctional CoFe2O4–reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: excellent microwave absorber and highly efficient magnetically separable recyclable photocatalyst for dye degradation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 76759–76772. 10.1039/C6RA17384E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton O. C.; Nguyen S. T. Graphene Oxide. Highly Reduced Graphene Oxide, and Graphene: Versatile Building Blocks for Carbon-Based Materials. Small 2010, 6, 711–723. 10.1002/smll.200901934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S.; Shen X.; Zhu G.; Li M.; Xi H.; Chen K. In situ growth of NixCo100–x nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide nanosheets and their magnetic and catalytic properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2378–2386. 10.1021/am300310d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surendran S.; Shanmugapriya S.; Sivanantham A.; Shanmugam S.; Kalai Selvan R. Electrospun carbon nanofibers encapsulated with NiCoP: a multifunctional electrode for supercapattery and oxygen reduction, oxygen evolution, and hydrogen evolution reactions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800555. 10.1002/aenm.201800555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H.; Xia C.; Jiang Q.; Gandi A. N.; Schwingenschlögl U.; Alshareef H. N. Low temperature synthesis of ternary metal phosphides using plasma for asymmetric supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2017, 35, 331–340. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-M.; Liu M.-C.; Hu Y.-X.; Yang Q.-Q.; Kong L.-B.; Kang L. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of porous nickel cobalt phosphides with high conductivity for advanced energy conversion and storage. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 215, 114–125. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.08.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Chen S.; Fan M.; Li C.; Chen D.; Tian G.; Shu K. Bimetallic nickel cobalt selenides: a new kind of electroactive material for high-power energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 23653–23659. 10.1039/C5TA08366D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Xue M.; Li Y.; Pan Y.; Zhu L.; Qiu S. Rational design and synthesis of NixCo3–xO4 nanoparticles derived from multivariate MOF-74 for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 20145–20152. 10.1039/C5TA02557E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Wang G.; Sun H.; Lu F.; Yu M.; Lian J. Morphology controlled high performance supercapacitor behaviour of the Ni–Co binary hydroxide system. J. Power Sources 2013, 238, 150–156. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K.-L.; Wei X.-W.; Zhou X.-M.; Wu D.-H.; Liu X.-W.; Ye Y.; Wang Q. NiCo2 alloys: controllable synthesis, magnetic properties, and catalytic applications in reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 16268–16274. 10.1021/jp201660w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Feng X.; Huang D.; Yang G.; Astruc D. Basic concepts and recent advances in nitrophenol reduction by gold-and other transition metal nanoparticles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 287, 114–136. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aditya T.; Pal A.; Pal T. Nitroarene reduction: a trusted model reaction to test nanoparticle catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 9410–9431. 10.1039/C5CC01131K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T.-L.; Yong K.-F.; Yu J.-W.; Chen J.-H.; Shu Y.-Y.; Wang C.-B. High efficiency degradation of 4-nitrophenol by microwave-enhanced catalytic method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 366–372. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra D.; Ghosh B. K.; Chandel M.; Ghosh N. N. Synthesis of a BiFeO3 nanowire-reduced graphene oxide based magnetically separable nanocatalyst and its versatile catalytic activity towards multiple organic reactions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 97941–97952. 10.1039/C6RA22077K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh R.; Venkatesan R. Encapsulation of silver nanoparticles into graphite grafted with hyperbranched poly (amidoamine) dendrimer and their catalytic activity towards reduction of nitro aromatics. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2012, 359, 88–96. 10.1016/j.molcata.2012.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh B. K.; Hazra S.; Naik B.; Ghosh N. N. Preparation of Cu nanoparticle loaded SBA-15 and their excellent catalytic activity in reduction of variety of dyes. Powder Technol. 2015, 269, 371–378. 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Wang X.; Yu Y.; Chen Y.; Dai L. Tailoring a magnetically separable NiFe2O4 nanoparticle catalyst for Knoevenagel condensation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 72, 8358–8363. 10.1016/j.tet.2016.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Dewan M.; Saxena A.; De A.; Mozumdar S. Knoevenagel condensation catalyzed by chemo-selective Ni-nanoparticles in neutral medium. Catal. Commun. 2010, 11, 679–683. 10.1016/j.catcom.2010.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E. M.; Zeltner M.; Kränzlin N.; Grass R. N.; Stark W. J. Base-free Knoevenagel condensation catalyzed by copper metal surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 10695–10698. 10.1039/C5CC02541A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski P.; Weber J.; Thomas A.; Goettmann F. A mesoporous poly (benzimidazole) network as a purely organic heterogeneous catalyst for the Knoevenagel condensation. Catal. Commun. 2008, 10, 243–247. 10.1016/j.catcom.2008.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy T. I.; Varma R. S. Rare-earth (RE) exchanged NaY zeolite promoted Knoevenagel condensation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1721–1724. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00180-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav J. S.; Reddy B. V. S.; Basak A. K.; Narsaiah A. V. [Bmim] BF4 ionic liquid: a novel reaction medium for the synthesis of β-amino alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 1047–1050. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)02735-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez F.; Orcajo G.; Briones D.; Leo P.; Calleja G. Catalytic advantages of NH2-modified MIL-53 (Al) materials for Knoevenagel condensation reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 246, 43–50. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senapati K. K.; Borgohain C.; Phukan P. Synthesis of highly stable CoFe2O4 nanoparticles and their use as magnetically separable catalyst for Knoevenagel reaction in aqueous medium. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011, 339, 24–31. 10.1016/j.molcata.2011.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]