Abstract

Introduction

Palmoplantar psoriasis (PPP) is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and/or soles. Although PPP is a disabling and therapeutically challenging condition, its epidemiology is poorly defined.

Aim

To assess the prevalence of PPP locations (palms, soles or both), and to analyse epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the disease.

Material and methods

Two bibliographic databases (MEDLINE and SCOPUS) were used as data sources searched from inception to October 2017. The selection of articles was limited to human subjects and English or French languages.

Results

A search resulted in a total of 293 articles, out of which 24 were utilized for the current systematic review and 21 for meta-analysis. All listed studies comprised a total of 2083 patients with PPP, with more males than females. According to the results of meta-analysis, majority of patients had the highest prevalence of both palms and soles involvement (95% CI: 47–67), with an almost equal prevalence showing palmar (21%; 95% CI: 13–30) or plantar (20%; 95% CI: 12–29) involvement. The most prevalent type of PPP was plaque/hyperkeratotic, followed by the pustular type.

Conclusions

Almost three-fifths (59%) of all PPP patients had involvement of both palms and soles, while exclusive palmar or plantar involvement was seen in 21% and 20% of patients, respectively. Future research should be performed to elucidate basic epidemiological and clinical characteristics of PPP, which would be helpful for proper consideration of this condition.

Keywords: palmoplantar psoriasis, prevalence, epidemiology, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Palmoplantar psoriasis (PPP) is a variant of psoriasis located on the palms and/or soles which often occurs along with psoriasis elsewhere on the body and less commonly may be the only skin manifestation [1, 2]. The prevalence of PPP in psoriasis patients varies between studies from 2.8% to 40.9% [3]. The lesions of PPP are typically bilaterally symmetrical, although unilateral involvement may be seen [3]. PPP can express many different morphologic patterns ranging from thick hyperkeratotic plaques to pustular lesions with a spectrum of overlapping of both [1, 4, 5]. Unlike chronic plaque psoriasis, PPP has a significant discordance between body surface area (BSA) involvement and impact on health-related quality of life (QoL) [1]. Even though PPP involves a small percentage of the BSA, patients with this condition are more likely to suffer from greater QoL impairment than those with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [6], and have significantly higher impairment at work/hobbies [7]. According to Pettey et al. [8], the unique impact of PPP involvement beyond common plaque psoriasis is primarily physical with a greater physical dysfunction and physical discomfort. Only a few studies compared QoL between patients with PPP on the palms and the soles. In the study of American psoriasis patients, QoL was overall more impaired due to psoriasis on the palms than on the soles [9], while the opposite was true in the study of Serbian psoriasis patients [10].

Although PPP is a disabling variant of psoriasis and therapeutically challenging condition which is often recalcitrant to various topical and systematic therapy [11–13], its epidemiology is poorly defined.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the prevalence of PPP for each single location (palms or soles or both) and to find out which one is the most prevalent. In addition, we were interested to know the gender more affected by the PPP and the most common morphological type of this condition.

Material and methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14].

Identification of studies

The MEDLINE (via PubMed), and Elsevier’s abstract and citation database SCOPUS were searched from inception to October 2017 by two independent investigators (Sojević Timotijević Z, Trajković G). The following search terms were used: psoriasis[ti] palmoplantar*[ti]. Searching was restricted to English and French language articles. There was no restriction on the type of psoriasis and patients age. We manually searched the references of all selected articles to identify other relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria of the selected studies were: (1) at least one sample of psoriatic patients designated as palmoplantar psoriasis; (2) published data on absolute frequency or proportion of number of patients with psoriasis involvement of (a) palms, (b) soles, and (c) both, or possibility to reconstruct such numbers based on the available data. The criterion for exclusion was the inability to find numbers or proportions of patients with PPP by single locations (palms, soles, or both).

Data extraction and analysis

While the titles and abstracts met the inclusion criteria, full-text articles were searched and screened independently by two investigators (Sojević Timotijević Z, Trajković G) to confirm eligibility and any disagreement was resolved by consensus or a third opinion (Janković S).

The following information was extracted: first author, year of publication, origin of the study, study design, study date, study population (sample size, percentage of men and women, mean age and/or age range of subjects), clinical type of psoriasis, PPP involvement of palms, soles, and both, involvement of the rest of the body, and baseline disease measures.

We used qualitative analysis to aggregate findings from selected studies and the random effects weighted analysis to obtain the pooled proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of affected sites (palms, soles, and both), illustrated in a forest plot. The method of Barendregt and Doi [15] for meta-analysis of multiple categories was applied.

Results

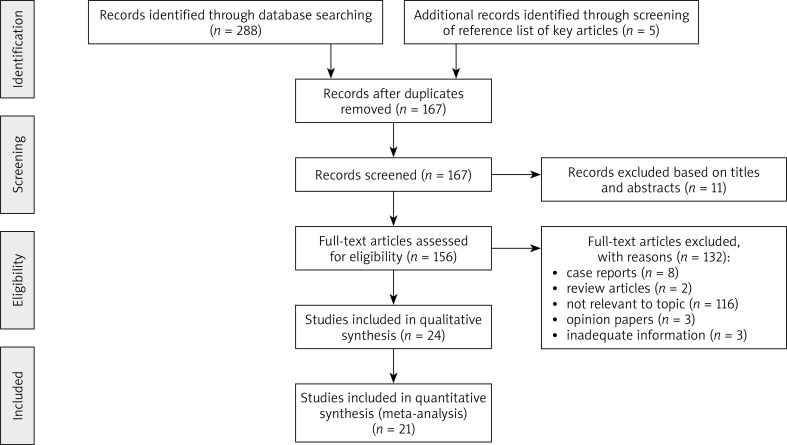

In total 293 relevant articles that fit our search strategy were identified. The procedure for identifying and selecting eligible studies is shown in Figure 1. After removal of duplicates (126 records), 167 articles remained for screening. A further 11 articles were excluded through abstract screening. Of 156 articles available for full-text reading, 132 articles were excluded according to exclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 24 articles that fulfilled criteria were included in our systematic review [1, 3, 12, 16–36]. Out of 24 studies, 21 were included in the meta-analysis, while three studies did not fulfil the inclusion criteria [1, 16, 25] since data on involvement of palms and/or soles could not be precisely extracted for all PPP cases.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study identification, inclusion and exclusion criteria

The basic characteristics of all 24 studies included in the review are presented in Table 1. Seven studies were intervention studies; the remaining 17 were observational in design. The included studies were conducted in 13 different countries (8 studies were from India, 2 from the USA, 2 from Israel, 2 from Austria, 2 from Germany and one study from each of the following countries: Japan, Canada, Kuwait, France, England, Italy, and Turkey). One study was a joint study from Italy and Austria.

Table 1.

Description of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis of palmoplantar psoriasis

| First author, year | Country | Type of study | Study dates | Study population | Clinical type | Palms/soles involved, n (%) | Rest body involved | Disease measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adişen, 2009* | Turkey | Retrospective cohort study | 2003–2007 | 114 patients Age range: 10–72 y 50 males and 64 females |

Plaque or hyperkeratotic Pustular |

P or S: 22 (19.2) PS: 92 (80.7) |

NA | NA |

| Al-Mutairi, 2014 | Kuwait | Case-series | January 2011 to January 2013 | 103 patients Mean age: 37.4 y; range: 15–71 y† 62 males and 41 females |

Plaque Pustular |

P: 14 (13.6) S: 22 (21.4) PS: 67 (65) |

Yes | NA |

| Angelovska, 2014 | Germany | Case-series | 2007–2012 | 6 patients Age range: 41–57 y 5 males and 1 female |

Hyperkeratotic Pustular |

P: 5 (83.3) S: 0 (0) PS: 1 (16.7) |

Yes | NA |

| Bissonnette, 2011 | Canada | Randomized double blind trial | February 2007 to July 2008 | 24 patients 9 males and 15 females |

Plaque | P: 2 (8.3) S: 2 (8.3) PS: 20 (83.4) |

Yes | PPSA ≥ 10%; m–PPPASI ≥ 8; PGA; DLQI |

| Brunasso, 2010 | Austria | Case-series | January 2005 to December 2009 | 19 patients Mean age: 58.5 y; range: 41–79 y 8 males and 11 females |

Pustular | P: 6 (31.6) S: 4 (21.0) PS: 9 (47.4) |

Yes | PGA score ≤ 2 outside the PPSA |

| Brunasso, 2013 | Italy and Austria | Retrospective case-series | January 2005 to January 2010 | 90 patients, mean age: 57.7 y; range: 11–82 y 45 males and 45 females |

Plaque Pustular |

P: 21 (23.3) S: 19 (21.1) PS: 50(55.6) |

Yes | BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 5%; PGA score ≤ 2 outside the PPSA |

| Coleman, 1989 | United States | Retrospective cohort study | April 1986 to November 1987 | 11 patients Age range: 32–69 y 5 males and 6 females |

Plaque Pustular |

P: 3 (27.2 ) S: 4 (36.4) PS: 4 (36.4) |

NA | Four point scale score |

| Farley, 2009* |

United States | Retrospective cohort study | August 2006 to March 2008 | 150 patients | Hyperkeratotic Pustular Hyperkeratotic/pustular Indeterminate |

P: 21 (14.0) S: 10 (7.0) P or S: 27 (18.0) PS: 92 (61.0) |

Yes | PPSA ≥ 50%; BSA outside the PPSA; PPQoLI |

| Haseena, 2017 | India | Open trial | October 2009 to September 2010 | 28 patients, mean age: 42.2 y; range: 14–68 y 17 males and 11 females |

Plaque or hyperkeratotic | P: 8 (28.6) S: 13 (46.4) PS: 7 (25) |

Yes | PPSA > 30%; BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 5%; ESIF score |

| Hofer, 2006 | Austria | Randomized trial | NA | 8 patients Mean age: 50 y, range: 26–65 y 3 males and 5 females |

Pustular Hyperkeratotic | P: 2 (25.0) S: 0 (0) PS: 6 (75.0) |

NA | SI (erythema, infiltration, scaling and vesicles) |

| Janagond, 2013 | India | Randomized trial | January 2011 to February 2012 | 100 patients Age range: 17–53 y 59 males and 41 females |

Plaque | P: 3 (3.0) S: 1 (1.0) PS: 96 (96.0) |

Yes | PPSA ≥ 50%; m-PPPASI |

| Khandpur, 2011* | India | Case-series | 2006–2008 | 154 patients, age range: 21–50 y (for 67% of patients) 111 males and 43 females |

NA | P: 24 (15.6) S: 22 (14.3) P or S: 33 (21.4) PS: 75 (48.7) |

Yes | NA |

| Kumar, 1997 | India | Randomized trial | NA | 28 patients Age range: 8–60 y 12 males and 16 females |

Plaque | P: 4 (14.3) S: 9 (32.1) PS: 15 (53.6) |

Yes | PPSA ≥ 30%; BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 5%; ESI score |

| Kumar, 2002 | India | Retrospective cohort study | 1993–2000 | 532 patients Age range 6–73 y† 282 males and 250 females |

Plaque/hyperkeratotic Pustular |

P: 43 (8.1) S: 236 (44.4) PS: 253 (47.5) |

Yes | BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 30% |

| Kumar, 2004 | India | Open trial | NA | 14 patients Mean age: 41.5 y; range: 18–52 y 11 males and 3 females |

Plaque | P: 2 (14.3) S: 2 (14.3) PS: 10 (71.4) |

NA | PPSA ≥ 30%; ESIF score |

| Lawrence, 1984 | England | Randomized double blind trial | NA | 20 patients | Hyperkeratotic Pustular | P: 0 (0) S: 5 (25.0) PS: 15 (75.0) |

Yes | NA |

| Lior, 2010 | Israel | Open trial | NA | 7 patients Mean age: 47 y;range: 27–68 y 4 males and 3 females |

Plaque | P: 3 (42.9) S: 1 (14.2) PS: 3 (42.9) |

Yes | NA |

| Lozinski, 2016 | Israel | Retrospective cohort study | 2010–2012 | 248 patients Age range: 10–87 y 143 males and 105 females |

Plaque | P: 23 (9.3) S: 16 (6.4) PS: 209 (84.3) |

Yes | NA |

| Nisticò, 2006 | Italy | Open trial | NA | 54 patients Mean age: 48 y 29 males and 25 females |

NA | P: 27 (50.0) S: 19 (35.2) PS: 8 (14.8) |

Yes | BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 30%; PASI |

| Ravi Kumar, 1999 | India | Case-series follow-up | NA | 15 patients Age range: 22–65 y 9 males and 6 females |

Plaque | P: 1 (6.7) S: 5 (33.3) PS: 9 (60.0) |

Yes | PPSA > 30%; BSA outside the PPSA ≤ 5%; ESIF score |

| Redon, 2010 | France | Case-series | November 2001 to April 2008 | 92 patients Mean age: 47 y 54 males and 38 females |

Plaque/pustular | P: 43 (46.7) S: 7 (7.6) PS: 42 (45.7) |

NA | NA |

| Tanaka, 2000 | Japan | Case-series | NA | 9 patients Age range: 25–80 y 4 males and 5 females |

Pustular | P: 0 (0) S: 2 (22.2) PS: 7 (77.8) |

NA | PASI |

| Venkatesan, 2015 | India | Cross-sectional hospital based study | January to June 2014 | 236 patients Age range: 20–60 y† 142 males and 94 females |

Plaque | P: 66 (28.0) S: 47 (19.9) PS: 123 (52.1) |

Yes | NA |

| Wilkinson, 1979 | Germany | Case-series | NA | 21 patients Age range: 31–75 y 8 males and 13 females |

Plaque or hyperkeratotic Pustular | P: 7 (33.3) S: 4 (19.0) PS: 10 (47.7) |

NA | NA |

Not included in meta-analysis, †for all psoriasis patients, PP – palmoplantar psoriasis, P – palms, S – soles, PS – both palms and soles, NA – not available, y – year, BSA – body surface area, PPSA – palmoplantar surface area, PGA – physician’s global assessment, m-PPPASI – modified palmoplantar (pustular) psoriasis area and severity index, DLQI – dermatology life quality index, PPQoLI – palmar-plantar quality of life index, PASI – psoriasis area and severity index, SI – severity index, ESI – erythema, scaling, induration, ESIF – erythema, scaling, induration, fissuring.

All listed studies comprised a total of 2083 patients with PPP. According to available data from 22 studies, more males (1072) than females (841) were affected by PPP. For 170 patients from two studies, gender data were not available. The statistically significant predominance of men was noted in nine studies, while the predominance of women was seen in two studies. Ages of patients ranged from 8 [26] up to 87 years [30], whereas the mean age ranged from 37.4 years [17] to 58.5 years [20]. With the exception of two studies [25, 31], all the remaining studies reported a clinical type/s of PPP as plaque/hyperkeratotic, pustular or mixed. The most common was the plaque/hyperkeratotic type.

In most studies (20) all three locations: palms, soles and both were affected by psoriasis, whereas in 4 remaining studies only two locations in each study were affected: palms and both palms and soles [18, 24], and soles and both palms and soles [28, 34]. Most studies (17) confirmed the involvement of the rest of the body, while data were not available in 7 studies.

To assess severity of PPP, different measures were used, such as involved palmoplantar surface area (PPSA), involved BSA outside the palmoplantar region, physician’s global assessment (PGA) score for extra-palmoplantar lesions, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), modified palmoplantar (pustular) psoriasis area and severity index (m-PPPASI), severity index (SI), erythema, scaling and induration (ESI) score; and erythema, scaling, induration and fissuring (ESIF) score. In addition, two QoL instruments were used: dermatology life quality index (DLQI), and palmar-plantar QoL index (PPQoLI). For the body involvement with psoriasis, different cutoff levels were reported: four cutoff levels for the involvement of PPSA: ≥ 10% [19], ≥ 30% [26, 27], > 30% [23, 32], and ≥ 50% [1, 12]; and two cutoff levels for the involvement of BSA outside the palms and soles: ≤ 5% [21, 23, 26, 32], and ≤ 30% [3, 31]. PGA score for extra-palmoplantar lesions was used in three studies [19–21], and m-PPPASI was used in two studies [12, 19]. Most studies used more than one measure. Only six studies [3, 23–25, 35, 36] reported data on unilateral/bilateral distribution of lesions on palms and soles, with more frequent bilateral lesions.

Prevalence of PPP in all psoriasis patients

The prevalence of PPP as a part of a larger study on psoriasis was noted in six studies included in this analysis [1, 3, 12, 16, 17, 35]. It ranged from 10.1% [17] to 59% [35], and even to 76% [12] of all psoriasis patients.

Prevalence of PPP locations

Most studies (18) reported that the prevalence of PPP of both palms and soles was higher (ranging from 15% to 96%), than the prevalence of palmar or plantar single location (ranging from 0 to 50% and from 0 to 44%, respectively) (Table 1).

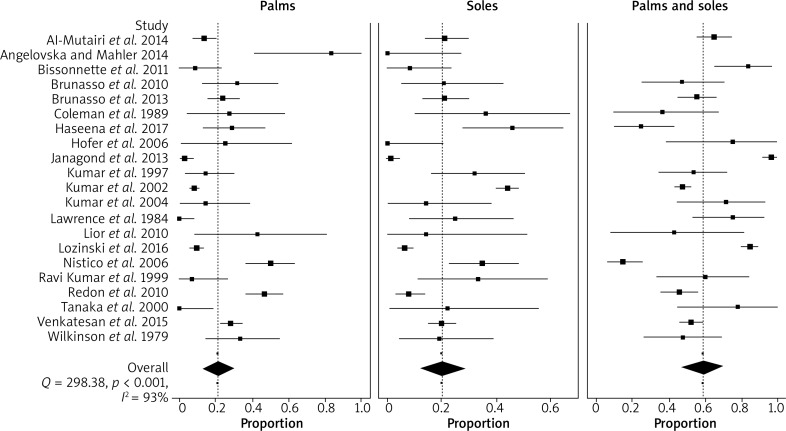

When considering the 21 studies included in the meta-analysis, the highest PPP prevalence was seen for both palms and soles involvement (59%; 95% CI: 47–67). The prevalence of each single location, i.e. of palms (21%; 95% CI: 13–30), and of soles (20%; 95% CI: 12–29) involvement was almost equal. Random effects pooling was used due to significant heterogeneity (Q = 298.38; p < 0.001, I 2 = 93%). The proportions of PPP in individual studies and their weighted average by specific locations are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot depicting proportions with their confidence intervals from the studies comparing involvement of affected sites in patients with palmoplantar psoriasis

Discussion

The prevalence of PPP locations showed high variability between studies varying from 15% to 96% when considering both palms and soles, while the palms and soles involvement was seen from 0% to 50%, and from 0% to 44%, respectively.

The meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of PPP of both palms and soles (59%) was almost three times higher than the prevalence of any single location of PPP, i.e. either palms (21%) or soles (20%) involvement. However, there was no statistically significant difference between palmar and plantar involvement (80% vs. 79%), which is in accordance with several studies from the West [37, 38]. In contrast, Indian authors reported that plantar involvement in their patients was twice more common than palmar involvement, and attributed this to the Indian custom of walking barefoot or wearing open slippers most of the time [3, 39].

There is a paucity of information about gender differences in psoriasis [40], especially in localized psoriasis variants such as PPP [41]. Our results suggest that more males than females were affected by PPP. This topic should deserve more attention in the future, with special focus on the practical implications that gender-specific characteristics may have on the prognosis and therapy of PPP [40].

According to the results of this review, ages of patients ranged from 8 to 87 years, which is in accordance with the previous finding that PPP affects individuals of all ages [41]. In the study by Chung et al. [6], patients with PPP were older than patients with plaque psoriasis with mean ages of 53.8 years vs. 48.7 years, respectively.

PPP can be seen in many different clinical forms [5]. It features hyperkeratotic, pustular, or mixed morphologies [41]. In this review, patients displayed predominantly plaque/hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lesions, followed by pustular lesions and their combination (plaque/pustular). Only in two studies [20, 34], pure palmoplantar pustulosis is recognised as a subtype of psoriasis, which is in agreement with other studies [42, 43]. The results of a study conducted by Brunasso et al. [21] suggest a close relationship between PPP and palmoplantar pustulosis and that the existing data concerning epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, histopathology and pathogenesis do not permit a clear distinction between these two entities. However, most genetic studies in last two decades have provided evidence that palmoplantar pustulosis is a disease distinct from psoriasis [44–49]. According to a recently published systematic review of palmoplantar pustulosis, there are no sufficient data to exclude this condition from the psoriasis group [50]. Future studies are needed to elucidate this still controversial issue.

PPP may exist separately or may be associated with psoriasis elsewhere on the body [5]. Almost 40% of the patients from 15 studies included in this review had an isolated form of PPP without lesions elsewhere. Kumar et al. [3] reported the highest percentage of the patients (almost 70%) with isolated PPP as a consequence of longer persistence/refractory nature of lesions at palms and/or soles.

There is no universally accepted definition of mild, moderate and severe PPP. It is well known that PPP severity appeared independent from the degree of BSA involvement [1] and that even mild psoriasis located on the palms and/or soles frequently needs more intensive therapy than does psoriasis elsewhere [4]. For the assessment of PPP severity, different traditional measures with different cutoff levels were used in the studies included in this review. However, the researchers agreed that the level of functional impairment should be taken into account, rather than relying on traditional measures [1, 4, 6]. Two assessment tools specifically tailored to patients with PPP were developed to help clinicians to measure the severity of PPP and response to treatment: m-PPPASI [19, 51] and PPQoLI [1].

The lesions of PPP are almost always bilaterally symmetrical, which was well illustrated in all studies with available data, with a high percentage of patients showing this pattern (100% in the studies by Wilkinson et al. [36], Hofer et al. [24], and Haseena et al. [23]; and between 79% and 96% in the studies by Khandpur and Sharma [25], Venkatesan et al. [35], and Kumar et al. [3].

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the PPP prevalence according to the affected locations and basic epidemiological and morphological characteristics. However, the results of this review should be considered in light of some limitations. Our sample was not comprehensive. We focused in our literature search on the terms “palmoplantar” and “psoriasis”, and only papers written in English and French language were considered.

Conclusions

According to our results, even three fifths of all PPP patients had involvement of both palms and soles (59%), while two fifths of them had either the palm (21%) or sole (20%) involvement. Males were more affected by PPP than females. The data concerning the percentage of involved PPSA and BSA outside the PPSA, as well as data concerning unilateral/bilateral involvement of the palms and/or soles, were lacking in most studies. Also there is no consistency between studies in determining disease measures used as inclusion criteria, and their cutoff values. Future research should be performed to elucidate basic epidemiological characteristics of PPP and to assess which location of PPP (palms or soles) causes greater physical discomfort and functional disability which probably would be helpful for proper consideration of this debilitating and therapeutically challenging condition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (project No. 175025).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, Menter A. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths CE, Christophers E, Barker JN, et al. A classification of psoriasis vulgaris according to phenotype. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:258–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar B, Saraswat A, Kaur I. Palmoplantar lesions in psoriasis: a study of 3065 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:192–5. doi: 10.1080/00015550260132488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menter A, Griffiths CE. Current and future management of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:272–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engin B, Aşkın Ö, Tüzün Y. Palmoplantar psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung J, Callis Duffin K, Takeshita J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis is associated with greater impairment of health-related quality of life compared with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:623–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Living with psoriasis: prevalence of shame, anger, worry, and problems in daily activities and social life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:299–303. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettey AA, Balkrishnan R, Rapp SR, et al. Patients with palmoplantar psoriasis have more physical disability and discomfort than patients with other forms of psoriasis: implications for clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:271–5. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb A, Sullivan J, van Doorn M, et al. Secukinumab shows significant efficacy in palmoplantar psoriasis: results from GESTURE, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sojević Timotijević Z, Janković S, Trajković G, et al. Identification of psoriatic patients at risk of high quality of life impairment. J Dermatol. 2013;40:797–804. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapp SR, Feldaman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janagond AB, Kanwar AJ, Handa S. Efficacy and safety of systemic methotrexate vs. acitretin in psoriasis patients with significant palmoplantar involvement: a prospective, randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e384–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sezer E, Erbil AH, Kurumlu Z, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of local narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) phototherapy versus psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) paint for palmoplantar psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:435–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA. Meta XL User Guide, version 5.3 [Computer software] 2016. Available at https://epigear.com/index_files/metaxl.htmlaccessed 29 May 2018).

- 16.Adisen E, Tekin O, Gulekon A, Gürer MA. A retrospective analysis of treatment responses of palmoplantar psoriasis in 114 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:814–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Mutairi N, Abdalla TO, Nour TM. Resistant palmoplantar lesions in patients of psoriasis: evaluation of the causes and comparison of the frequency of delayed-type hypersensitivity in patients without palm and sole lesions. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:561–7. doi: 10.1159/000365573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelovska I, Mahler V. Occupational palmoplantar psoriasis: a clinical case series with consideration of the S1 guidelines on expert medical assessments of occupational psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:697–708. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bissonnette R, Poulin Y, Guenther L, et al. Treatment of palmoplantar psoriasis with infliximab: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1402–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunasso AM, Massone C. Can we really separate palmoplantar pustulosis from psoriasis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:619–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunasso AM, Puntoni M, Aberer W, et al. Clinical and epidemiological comparison of patients affected by palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a case series study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1243–51. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman WR, Lowe NJ, David M, Halder RM. Palmoplantar psoriasis: experience with 8-methoxypsoralen soaks plus ultraviolet A with the use of a high-output metal halide device. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:1078–82. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haseena K, George S, Riyaz N, et al. Methotrexate iontophoresis versus coal tar ointment in palmoplantar psoriasis: a pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:569–73. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_185_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer A, Fink-Puches R, Kerl H, et al. Paired comparison of bathwater versus oral delivery of 8-methoxypsoralen in psoralen plus ultraviolet: a therapy for chronic palmoplantar psoriasis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2006.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khandpur S, Sharma VK. Comparison of clobetasol propionate cream plus coal tar vs. topical psoralen and solar ultraviolet A therapy in palmoplantar psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:613–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar B, Kumar R, Kaur I. Coal tar therapy in palmoplantar psoriasis: old wine in an old bottle? Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:309–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar B, Sandhu K, Kaur I. Topical 0.25% methotrexate gel in a hydrogel base for palmoplantar psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:798–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence CM, Marks J, Parker S, Shuster S. A comparison of PUVA-etretinate and PUVA-placebo for palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:221–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb07471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lior S, Grigory K, Pnina S, et al. Therapeutic hotline. Alefacept in the treatment of hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:556–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozinski A, Barzilai A, Pavlotsky F. Broad-band UVB versus paint PUVA for palmoplantar psoriasis treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:221–3. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1093588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Stefanescu S, Chimenti S. A 308-nm monochromatic excimer light in the treatment of palmoplantar psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:523–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravi Kumar BC, Kaur I, Kumar B. Topical methotrexate therapy in palmoplantar psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1999;65:270–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redon E, Bursztejn AC, Loos C, et al. A retrospective efficacy and safety study of UVB-TL01 phototherapy and PUVA therapy in palmoplantar psoriasis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka N, Fujioka A, Tajima S, et al. Levels of proelafin peptides in the sera of the patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and pustulosis palmoplantaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesan A, Aravamudhan R, Perumal SK, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis- ahead in the race – a prospective study from a tertiary health care centre in South India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:WC01–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11716.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson JD, Ralfs IG, Harper JI, Black MM. Topical methoxsalen photochemotherapy in the treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1979;(Suppl 59):193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molin L. Psoriasis. A study of the course and degree of severity, joint movements, socio-medical conditions, general morbidity and infuences of selection factors among previously hospitalized psoriatics. Acta Derm Venereol. 1972;53(Suppl 72):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farber EM, Nall ML. The natural history of psoriasis in 5,600 patients. Dermatologica. 1974;148:1–18. doi: 10.1159/000251595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Natural history of psoriasis: a study from the Indian subcontinent. J Dermatol. 1997;24:230–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colombo D, Cassano N, Bellia G, Vena GA. Gender medicine and psoriasis. World J Dermatol. 2014;3:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miceli A, Schmieder J. Palmoplantar psoriasis. StatPearls [Internet] Publishing LLC. 2017. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448142/ [PubMed]

- 42.Christophers E, Mrowietz U. Psoriasis. In: Burgdorf WHC, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Landthaler M, editors. Braun Falco’s Dermatology. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 506–26. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bissonnette R, Suárez-Farińas M, Li X, et al. Based on molecular profiling of gene expression, palmoplantar pustulosis and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis are highly related diseases that appear to be distinct from psoriasis vulgaris. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asumalahti K, Ameen M, Suomela S, et al. Genetic analysis of PSORS1 distinguishes guttate psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:627–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mossner R, Kingo K, Kleensang A, et al. Association of TNF-238 aand -308 promoter polymorphisms with psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis but not with pustulosis palmoplantaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:282–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Waal AC, van de Kerkhof PC. Pustulosis palmoplantaris is a disease distinct from psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:102–5. doi: 10.3109/09546631003636817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marsland AM, Chalmers RJ, Hollis S, et al. Interventions for chronic palmoplantar pustulosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD001433. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001433.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ammoury A, El Sayed F, Dhaybi R, Bazex J. Palmoplantar pustulosis should not be considered as a variant of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:392–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto T. Extra-palmoplantar lesions associated with palmoplantar pustulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1227–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Misiak-Galazka M, Wolska H, Rudnicka L. What do we know about palmoplantar pustulosis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:38–44. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunasso AM, Salvini C, Massone C. Efalizumab for severe palmoplantar psoriasis: an open-label pilot trial in five patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:415–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]