Abstract

Distress is defined in the NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management as a multifactorial, unpleasant experience of a psychologic (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment. Early evaluation and screening for distress leads to early and timely management of psychologic distress, which in turn improves medical management. The panel for the Distress Management Guidelines recently added a new principles section including guidance on implementation of standards of psychosocial care for patients with cancer.

Overview

In the United States, it is estimated that there are more than 16.9 million individuals with a history of cancer, with a total of 1,762,450 new cancer cases estimated to occur in 2019.1 All patients experience some level of distress associated with the cancer diagnosis and the effects of the disease and its treatment, regardless of disease stage. Distress can result from the reaction to the cancer diagnosis and to the various transitions throughout the trajectory of the disease, including during survivorship. Clinically significant levels of distress occur in a subset of patients, and identification and treatment of distress are of utmost importance.

These NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management discuss the identification and treatment of psychosocial problems in patients with cancer. They are intended to assist oncology teams to identify patients who require referral to psychosocial resources and to give oncology teams guidance on interventions for patients with mild distress. These guidelines also provide guidance for social workers, certified chaplains, and mental health professionals by describing treatments and interventions for various psychosocial problems as they relate to patients with cancer.

Psychosocial Problems in Adult Patients With Cancer

In recent decades, dramatic advances in early detection and treatment options have increased the overall survival rates in patients of all ages with cancer. At the same time, these improved treatment options are also associated with substantial long-term side effects, such as fatigue, pain, anxiety, and depression, that interfere with patients’ ability to perform daily activities. In addition, the physiologic effects of cancer itself and certain anticancer drugs can also be nonpsychologic contributors to distress symptoms.2–4 Furthermore, patients with cancer may have preexisting psychologic or psychiatric conditions that affect their ability to cope with cancer. Survivors of cancer are about twice as likely to report medication use for anxiety and depression as adults who do not have a personal history of cancer.5

Overall, surveys have found that 20% to 52% of patients show a significant level of distress.6–8 The prevalence of psychologic distress in individuals varies by the type and stage of cancer and by patient age, gender, and race.9 Further, the prevalence of distress, depression, and psychiatric disorders has been studied in many stages and sites of cancer.10–15 Cancers of the head and neck may be particularly distressing because treatment may be disfiguring and associated with impacts on essential functions such as eating, swallowing, breathing, and speaking.16 Depression is also common in pancreatic cancer, a disease often associated with a poor prognosis.17

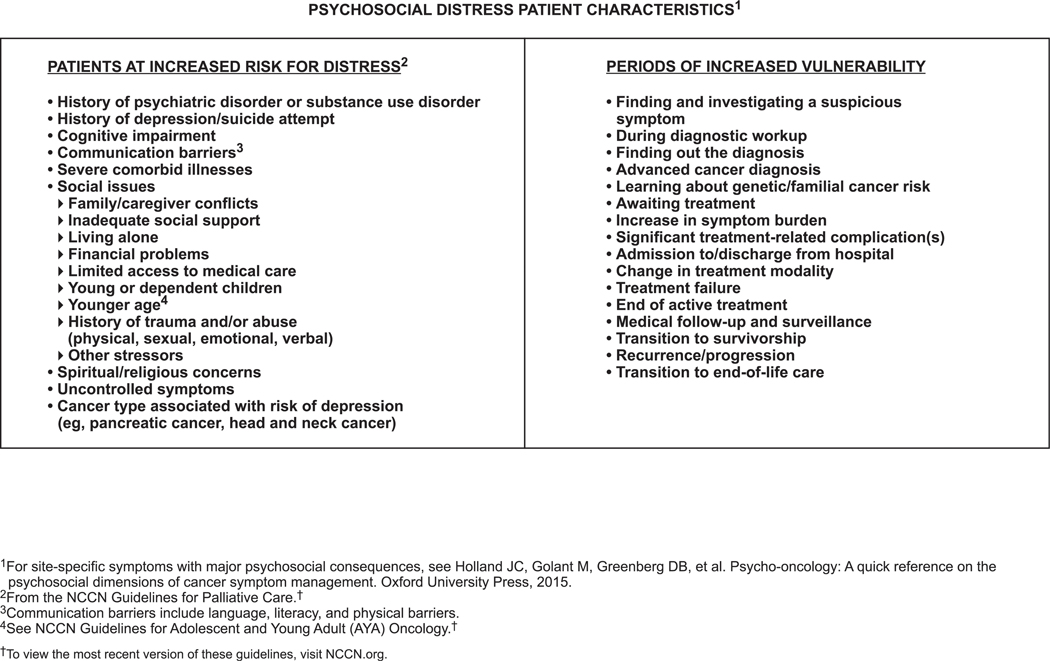

The NCCN panel identified characteristics associated with psychosocial distress, and these are listed on DIS-B (page 1235). Patients at increased risk for moderate or severe distress are those with a history of psychiatric disorder, current depression, or substance use disorder and those with cognitive impairment, severe comorbid illnesses, uncontrolled symptoms, communication barriers, or social issues. Social issues/risk factors include younger age, living alone, having young children, and prior trauma and/or abuse (physical, sexual, emotional, and/or verbal). Learning about genetic/familial risk of cancer is also associated with distress.18,19

Distress is a risk factor for nonadherence to cancer treatment.20,21 In addition to decreased adherence to treatment, failure to recognize and treat distress may lead to several problems: patients may have trouble making decisions about treatment and may make extra visits to the physician’s office and emergency room, which takes more time and causes greater stress to the oncology team.22,23 An analysis of 1,036 patients with advanced cancer showed that distress is associated with longer hospital stays (P=.04).24 Distress in patients with cancer also leads to poorer quality of life and may even negatively affect survival.25–28 Furthermore, survivors with untreated distress have poorer compliance with surveillance screenings and are less likely to exercise and quit smoking.29

Early evaluation and screening for distress leads to early and timely management of psychologic distress, which in turn improves medical management.30,31 A randomized study showed that routine screening for distress, with referral to psychosocial resources as needed, led to lower levels of distress at 3 months than did screening without personalized triage for referrals.32 Those with the highest level of initial distress benefitted the most. Overall, early detection and treatment of distress lead to better adherence to treatment, better communication, fewer calls and visits to the oncologist’s office, and avoidance of patients’ anger and development of severe anxiety or depression.

Barriers to Distress Management in Cancer

Many patients with cancer who are in need of psychosocial care are not able to get the help they need because of the under-recognition of patients’ psychologic needs by the primary oncology team and lack of knowledge of community resources.33 The need is particularly acute in community oncologists’ practices, where there are often fewer psychosocial resources.

An additional barrier to patients’ receiving the psychosocial care they require is the stigma associated with psychologic problems. For many centuries, patients were not told their diagnosis of cancer due to the stigma attached to the disease. Since the 1970s, this situation has changed, and patients are well aware of their diagnosis and treatment options.34 Many patients, however, may be reluctant to reveal emotional problems to the oncologist. The words “psychological,” “psychiatric,” and “emotional” maybe as stigmatizing as the word “cancer.” The word “distress” is less stigmatizing and more acceptable to patients and oncologists, but psychologic issues remain stigmatized even in the context of coping with cancer. Consequently, patients often do not tell their physicians about their distress and physicians do not inquire about the psychologic concerns of their patients. The recognition of patients’ distress has become more difficult as cancer care has shifted to the ambulatory setting, where visits are often short and rushed. These barriers prevent distress from receiving the attention it deserves, despite the fact that distress management is a critical component of the total care of the person with cancer.

NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management

A major milestone in the improvement of psychosocial care in oncology was made by NCCN when it established a panel to develop clinical practice guidelines, using the NCCN format. The panel began to meet in 1997 as an interdisciplinary group. The clinical disciplines involved were oncology, nursing, social work and counseling, psychiatry, psychology, and clergy. A patient advocate was also on the panel. Traditionally, clergy have not been included on NCCN Guidelines panels, but NCCN recognized that many distressed patients prefer to speak with a certified chaplain.35 NCCN Guidelines for the management of distress in patients with cancer were first published in 1999. This accomplishment provided a benchmark, which has been used as a framework in the handbook for oncology clinicians published by the IPOS (International Psycho-Oncology Society) Press.36

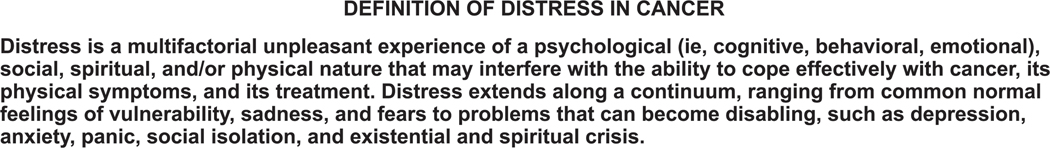

The panel defines distress as a multifactorial, unpleasant experience of a psychologic (ie, cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment (see DIS-2, page 1230). Distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common, normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis.

Recommendations in the guidelines are based on evidence and on consensus among panel members. In addition to the guidelines for oncologists, the panel established guidelines for social workers, certified chaplains, and mental health professionals (psychologists, psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, and psychiatric nurses).

The New Standard of Care for Distress Management in Cancer

Psychosocial care had not been considered as an aspect of quality cancer care until the publication of a 2007 National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) report, “Cancer Care for the Whole Patient,”37 which is based on the pioneering work of the NCCN panel. Psychosocial care is part of the standard for quality cancer care and should be integrated into routine care.37–39 The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) report supported the work of the NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management by proposing a model for the effective delivery of psychosocial health services that could be implemented in any community oncology practice:

Screening for distress and psychosocial needs;

Making and implementing a treatment plan to address these needs;

Referring to services as needed for psychosocial care; and

Reevaluating, with plan adjustment as appropriate.

In August 2012, the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons released new accreditation standards for hospital cancer programs. Their patient-centered focus now includes screening all patients with cancer for psychosocial distress. These standards are required for accreditation, were enacted in 2015, and were updated in 2016 (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards). According to the updated accreditation standards, institutions are expected to document and monitor their distress screening process.

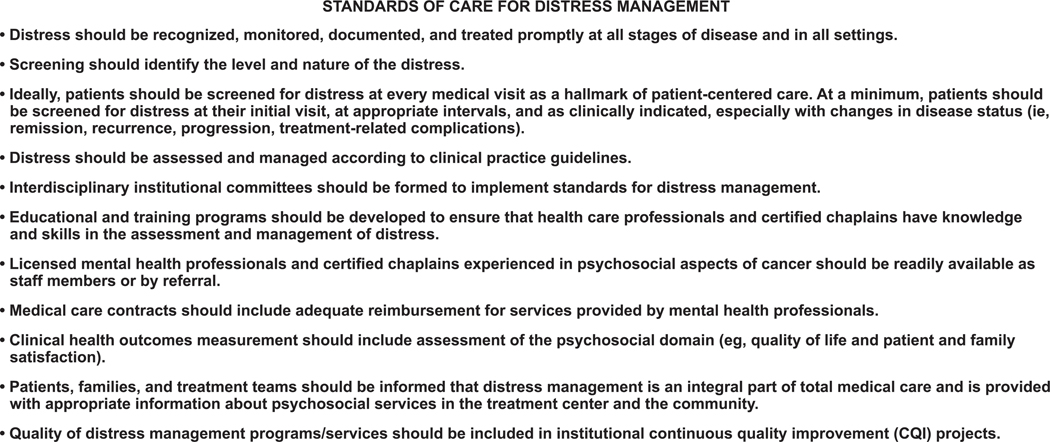

The standards of care for managing distress proposed by the NCCN Distress Management Panel are broad in nature and should be tailored to the particular needs of each institution and group of patients. The overriding goal of these standards is to ensure that no patient with distress goes unrecognized and untreated. The panel based these standards of care on quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of pain.40 The standards of care developed by the NCCN Distress Management Panel are described on DIS-3 (page 1231) and are as follows:

Distress should be recognized, monitored, documented, and treated promptly at all stages of disease and in all settings.

Screening should identify the level and nature of the distress.

Ideally, patients should be screened for distress at every medical visit as a hallmark of patient-centered care. At a minimum, patients should be screened to ascertain their level of distress at the initial visit, at appropriate intervals, and as clinically indicated, especially with changes in disease status (eg, remission, recurrence, or progression; treatment-related complications).

Distress should be assessed and managed according to clinical practice guidelines.

Interdisciplinary institutional committees should be formed to implement standards for distress management.

Educational and training programs should be developed to ensure that health care professionals and certified chaplains have knowledge and skills in the assessment and management of distress.

Licensed mental health professionals and certified chaplains experienced in the psychosocial aspects of cancer should be readily available as staff members or by referral.

Medical care contracts should include adequate reimbursement for services provided by mental health professionals.

Clinical health outcomes measurements should include assessment of the psychosocial domain (eg, quality of life; patient and family satisfaction).

Patients, families, and treatment teams should be informed that distress management is an integral part of total medical care and includes appropriate information about psychosocial services in the treatment center and in the community.

Finally, the quality of distress management programs/services should be included in institutional continuous quality improvement projects.

Patients and families should be made aware that this standard exists and that they should expect it in their oncologist’s practice. The website for the Alliance for Quality Psychosocial Cancer Care, a coalition of professional and advocacy organizations whose goal is to advance the recommendations from the NAM report, has hundreds of psychosocial resources for healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers, searchable by state (http://www.wholecancerpatient.org/).

Recommendations for Implementation of Standards and Guidelines

A 2013–2014 survey of applicants for a distress screening cancer education program, spanning 70 institutions, showed that fewer than half of these institutions had not yet begun implementation of a distress screening program.41 A 2014 survey of 55 cancer centers in the United States and Canada showed that adherence to an institution’s distress screening protocol (ie, screening with appropriate documentation) occurred 63% of the time.31 Another 2014 survey of 2,134 members of the Association of Oncology Social Work who were also employees of a CoC-accredited cancer program showed that most programs now have procedures in place to address psychosocial care and are successful in identifying psychosocial needs in patients and appropriately addressing these needs.42 However, programs tend to be less successful with follow-up of psychosocial care and training of providers regarding psychosocial care. A 2012 survey completed by 20 NCCN Member Institutions showed most institutions do not formally keep track of the number of patients who use psychosocial care and/or services, which limits the ability to ensure that centers are adequately implementing standards of psychosocial care.43

The MD Anderson Cancer Center published a 2010 report on its efforts to implement the integration of psychosocial care into clinical cancer care.44 The authors outline strategies they used to accomplish the required cultural shift and describe the results of their efforts. Other groups have also described their efforts toward implementing psychosocial screening in various outpatient settings.45–53 Surveys of clinical staff have identified barriers to adoption of distress screening and found that time, staff uncertainties, competing demands, and ambiguous accountability are some of the biggest barriers.54,55 A survey of oncology nurses also found that nurses who were familiar with these NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management were more comfortable discussing distress.54

Institutions should have a framework in place to deliver psychosocial care, to effectively manage distress in patients who would benefit from psychosocial services. Some initiatives have been developed to assist institutions with implementation of standards for distress screening and psychosocial care. Quality indicators can be used to determine the quality of psychosocial care given by a clinic or office. The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) was started in 2002 by ASCO as a pilot project (http://qopi.asco.org/program.html)56 and became available to all ASCO member medical oncologists in 2006. A 2008 manuscript showed that practices participating in QOPI demonstrated improved performance, with initially low-performing practices showing the greatest improvement.57 Blayney et al58 from the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center reported that QOPI can be adapted for use in practice improvement at an academic medical center.

Additional guidance for the implementation and dissemination of the new NAM standards has been published.53,59–65 In Canada, routine psychosocial care is part of the standard of care for patients with cancer; emotional distress is considered the sixth vital sign that is checked routinely along with pulse, respiration, blood pressure, temperature, and pain.22,66 A national approach has been used to implement screening for distress in Canada. Its strategies have been described in the extant literature.67,68 Groups in Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Japan have also described results of their preliminary efforts toward the implementation of psychosocial distress screening.69–72

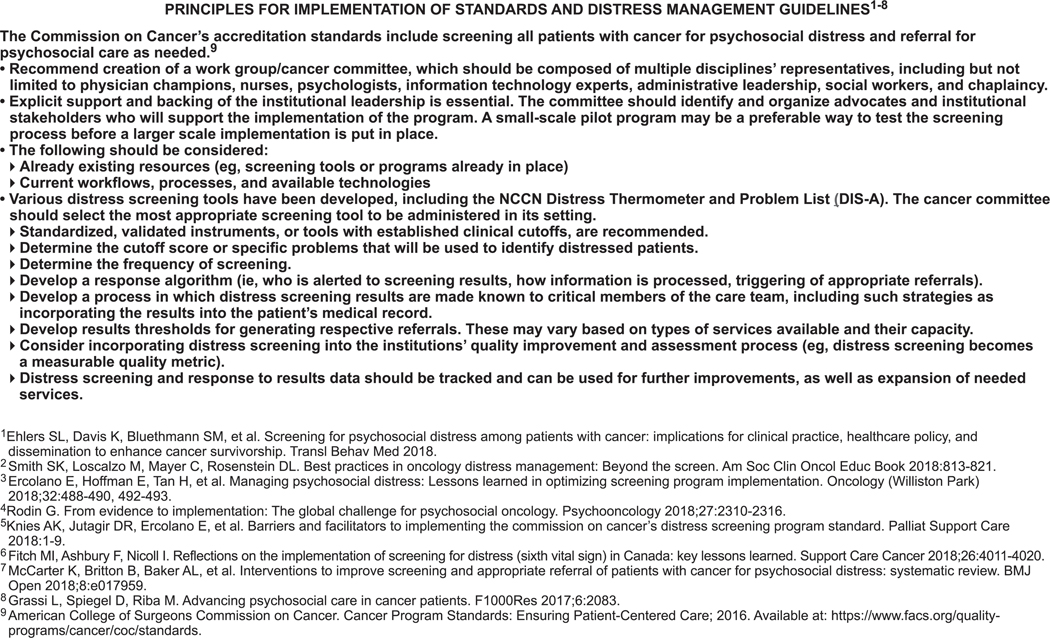

The panel has identified some principles of implementation to guide institutions in development of a distress screening protocol and process for appropriate referral and follow-up. These principles include the following (see DIS-27, page 1239):

Creation of an interdisciplinary work group/committee, which ideally would include physicians, nurses, psychologists, information technology experts, social workers, chaplains, and administrative leadership;

Mandatory support from institutional leadership;

Development and execution of a pilot program before any large-scale implementation; and

Consideration of the institution’s already existing resources and current workflow/processes.

Distress screening should be considered a measurable quality metric. Therefore, distress screening can be incorporated into institutions’ quality improvement and assessment processes. Some results have caused doubt regarding the efficacy of distress screening for improving patient outcomes. For instance, a systematic review failed to find evidence that screening improved distress levels over usual care in patients with cancer.73 Criticisms of this review include the inappropriately narrow inclusion criteria and the focus on only distress as an outcome.74 An unblinded, 2-arm, parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT) that used the Distress Thermometer (DT) and Problem List (discussed subsequently) as a screening tool versus usual care found no differences in psychologic distress at 12 months between the arms.75 However, no specific triage algorithms were followed, and inadequate staff training may have prevented effective referral and treatment.76 Another systematic review found that trials reporting a lack of benefit of distress screening in patients with cancer lacked appropriate follow-up care of distressed patients, and trials that linked screening with mandatory referral or intervention showed improvements in patient outcomes.77

Overall, results of these studies show that screening, although a critical component of psychosocial care, is not sufficient to impact patient outcomes without adequate follow-up referrals and treatment. Indeed, an RCT examining the effects of screening on 568 patients with cancer receiving radiotherapy showed that screening alone does not significantly affect distress and quality of life, but earlier referral to mental health professionals was associated with better outcomes (ie, greater health-related quality of life, less anxiety).78 For implementation of a distress screening protocol, an ideal frequency of screening should be identified, and institutions should develop a process for generating referrals and alerting the appropriate staff based on screening results. Whether screening is occurring, how often, and whether appropriate referrals are generated should be tracked. This information can be used by institutions to implement improvements in the process and potentially expand needed services.

Screening Tools for Distress and Meeting Psychosocial Needs

Identification of a patient’s psychologic needs is essential to develop a plan to manage those needs.39 In routine clinical practice, time constraints and the stigma related to psychiatric and psychologic needs often inhibit discussion of these needs. It is critical to have a fast and simple screening method that can be used to identify patients who require psychosocial care and/or referral to psychosocial resources. The NCCN Distress Management Panel developed such a rapid screening tool, as discussed subsequently.

Screening tools have been found to be effective and feasible in reliably identifying distress and the psychosocial needs of patients.79–81 Completion of a psychosocial screening instrument may lead to earlier referral to social work services.82 Mitchell et al83,84 reported that ultrashort screening methods (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] or the DT) were acceptable to about three quarters of clinicians. Other screening tools have also been described.85 Automated touch screen technologies, interactive voice response, and web-based assessments have also been used for psychosocial and symptom screening of patients with cancer.86–89

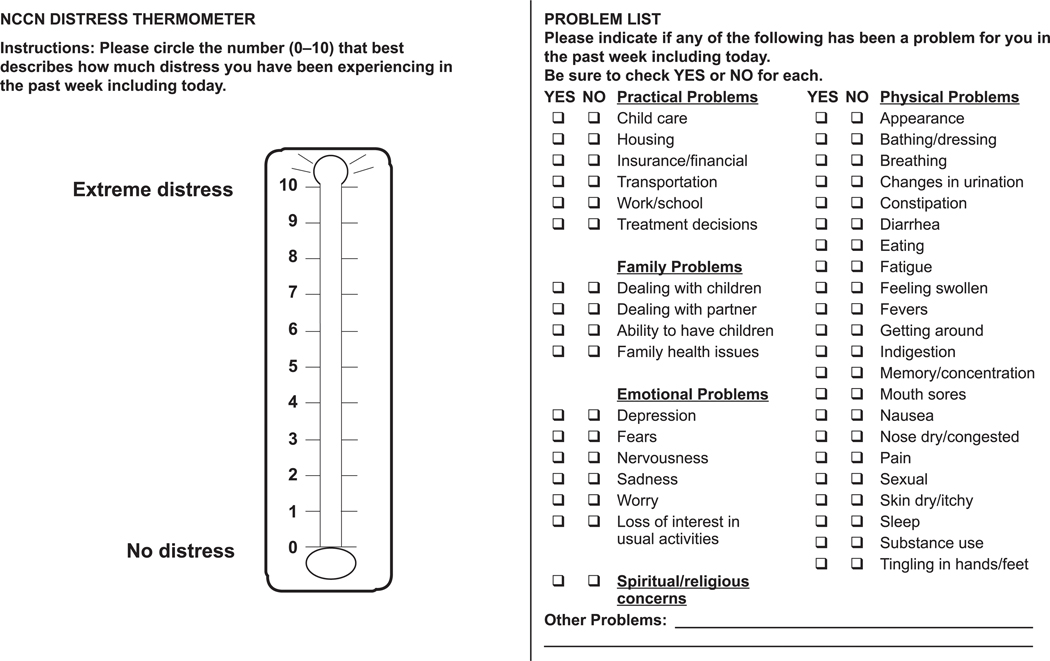

The Distress Thermometer

The NCCN Distress Management Panel developed the DT, a now well-known tool for initial screening, using 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), which is similar to the successful rating scale used to measure pain. The DT serves as an initial, single-item question screen, which identifies distress coming from any source, even if unrelated to cancer. The DT can be administered in a variety of settings, such as through a patient portal or given by a receptionist or medical assistant.

Patients are asked to indicate the number that best describes how much distress they have experienced over the past week, on a scale of 0 to 10. If the patient’s distress level is mild (score is <4 on the DT), the primary oncology team may choose to manage the concerns with usual clinical supportive care. If the patient’s distress level is ≥4, a member of the oncology team looks at the Problem List (discussed in the next section) to identify key issues of concern and asks further questions to determine the best resources (psychiatry, psychology, social work, or chaplaincy professionals) to address the patient’s concerns.

The DT has been validated by many studies in patients with different types of cancer, in different settings, and in different languages, cultures, and countries. The DT has shown good sensitivity and specificity. A meta-analysis of 42 studies with >14,000 patients with cancer found the pooled sensitivity of the DT to be 81% (95% CI, 0.79–0.82) and the pooled specificity to be 72% (95% CI, 0.71–0.72) at a cut-off score of 4.90 However, an analysis including 181 Dutch women who completed the DT within 1 month after breast cancer diagnosis showed that sensitivity was 95% and specificity was only 45% when the recommended cut-off score of 4 was used.91 Study investigators suggested that a cut-off score of 7 was optimal, with sensitivity being 73% and specificity being 84%. Using a higher cut-off score would reduce the number of false positives.

Although the DT is not a screening tool for psychiatric disorders, it has shown concordance with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 92–102 and the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21.103 A study including 463 patients with cancer showed that the DT does not accurately detect mood disorders (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria; area under the curve [AUC] = 0.59), compared with the PHQ-2 (AUC = 0.83 with a cut-off score ≥3) and PHQ-9 (AUC=0.85 with a cut-off score >9), which are both validated for screening patients with depressive symptoms.104

The NCCN DT and Problem List (see DIS-A, page 1234) are freely available for noncommercial use. In addition, the NCCN patient website includes a patient-friendly description of distress with a copy of the tool (available at http://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/distress.aspx). NCCN also has verified translations of the DT and Problem List in various languages that are freely available online (available at https://www.nccn.org/global/international_adaptations.aspx).

The Problem List

The screening tool developed by the NCCN Distress Management Panel includes a 39-item Problem List, which is on the same page as the DT (see DIS-A, page 1234). The Problem List asks patients to identify their problems in 5 different categories: practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious, and physical. The panel notes that the Problem List may be modified to fit the needs of the local population.

An analysis of the DT and Problem List including principal component analysis, logistic regression, and classification and regression tree analyses showed that endorsement of Problem List items associated with emotion (ie, sadness, worry, depression, fears, nervousness, sleep), physical function (ie, transportation, bathing/dressing, breathing, fatigue, getting around, memory/concentration, pain), and support (ie, spiritual/religious concerns, insurance/finances, dealing with partner) were significantly associated with moderate or severe distress (P<.001, P=.003, and P=.013, respectively).105

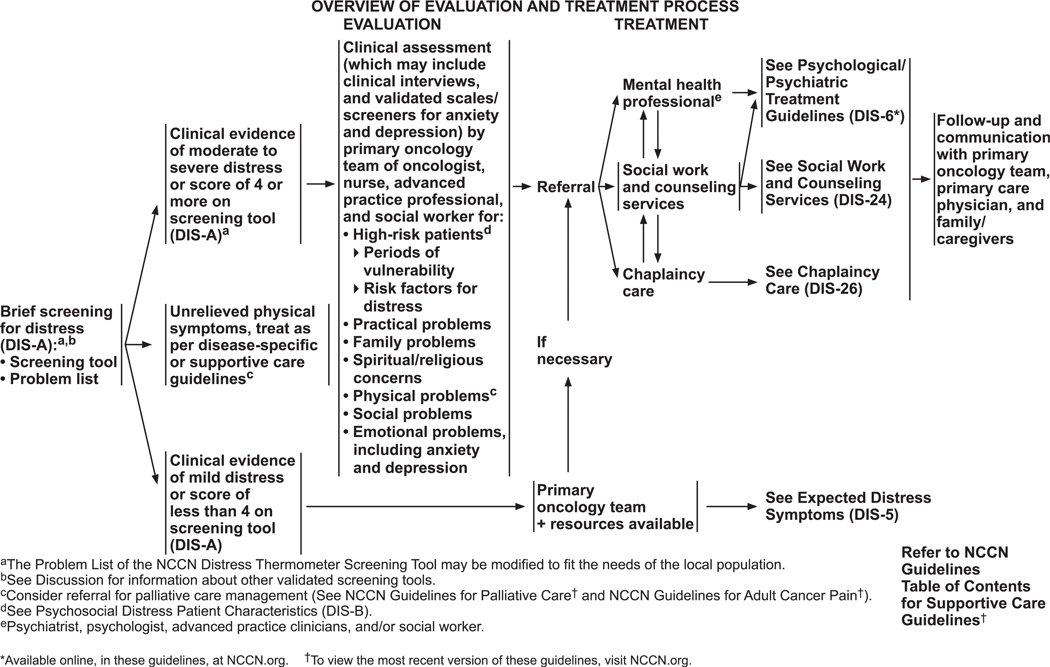

Initial Screening by Oncology Team

The process of distress screening is summarized on DIS-4 (page 1232). The panel recommends that all patients be screened before clinical visits using a simple tool. Although there are several types of screening tools, the DT and the accompanying Problem List are recommended to assess the level of distress and to identify causes of distress. If the patient’s distress is moderate or severe (DT score ≥4), the oncology team must recognize that score as a trigger to a second level of questions, including clinical interviews and/or validated scales/screeners for anxiety and depression. A positive screen should prompt referral to a mental health professional, social worker, or spiritual counselor, depending on the problems identified in the Problem List. Common symptoms that require further evaluation are excessive worries and fears, excessive sadness, unclear thinking, despair and hopelessness, severe family problems, social problems, and spiritual or religious concerns. Any unrelieved physical symptoms should be treated based on NCCN’s disease-specific guidelines, and referral for palliative care management may also be considered (see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care, available at NCCN.org).

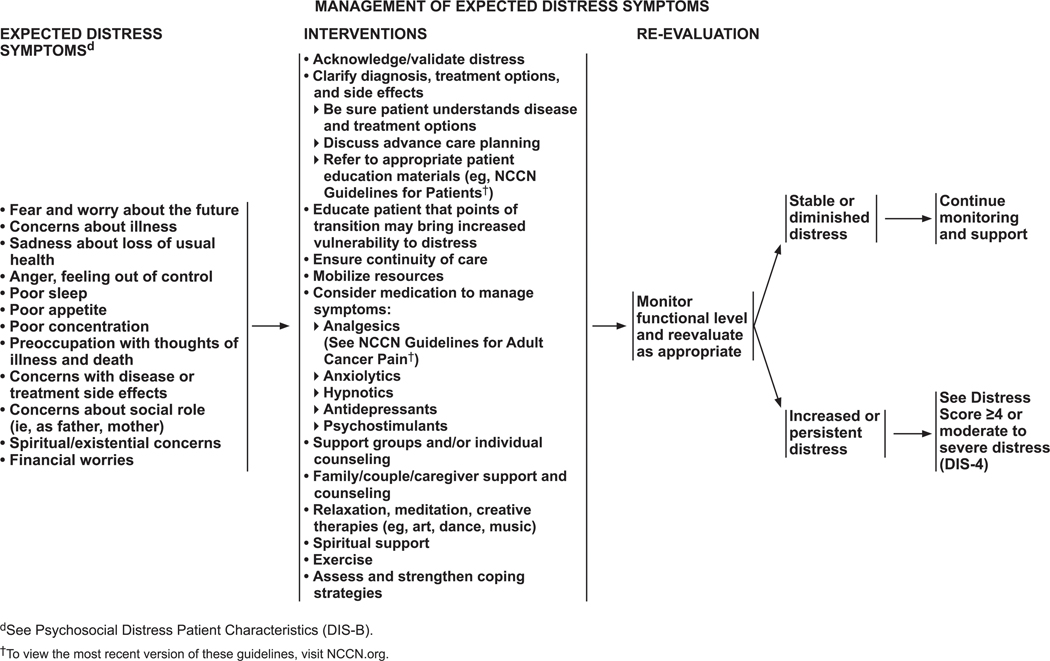

Mild distress (DT score <4) is routinely managed by the primary oncology team and represents what the panel terms “expected distress” symptoms. The symptoms that the team manages are fear and worry about the future; concerns about the illness; sadness about loss of good health; anger and the feeling that life is out of control; poor sleep, poor appetite, and poor concentration; preoccupation with thoughts of illness, death, treatment, and side effects; concerns about social roles (eg, mother, father); and spiritual or existential concerns. Many patients experience these symptoms at the time of diagnosis and during arduous treatment cycles. They might persist long after the completion of treatment. For instance, minor physical symptoms are often misinterpreted by survivors as a sign of recurrence, which causes fear and anxiety until they are reassured.

The primary oncology team is the first to deal with these distressing problems. The oncologist, nurse, and social worker each have a critical role. First and foremost, a critical component is the quality of the physician’s communication with the patient, which should occur in the context of a mutually respectful relationship so that the patient can learn the diagnosis and understand the treatment options and side effects. Adequate time should be provided for the patient to ask questions and for the physician to put the patient at ease. When communication is done well at diagnosis, the stage is set for future positive trusting encounters. It is important to ensure that the patient understands what has been said. Information may be reinforced with drawings or by recording the session and giving the recording to the patient. Communication skills training programs, for example, that teach oncology professionals how to discuss prognosis and unanticipated adverse events and how to reach a shared treatment decision, may be very helpful. In fact, in an RCT, it was found that patients of oncologists who had communication skills training were less depressed at follow-up than patients of oncologists from the control group (P=.027).106 For a comprehensive review of communication skills training see Kissane et al.107

It is important for the oncology team to acknowledge and validate that cancer presents a unique challenge and that distress is normal and expected. Being able to express distress to the staff helps provide relief to the patient and builds trust. The team needs to ensure that social supports are in place for the patient and that he or she knows about community resources such as support groups, teleconferences, and help lines. The NAM report contains a list of national organizations and their toll-free numbers.37 Some selected organizations that provide free information services to patients with cancer are:

American Cancer Society: www.cancer.org

American Institute for Cancer Research: www.aicr.org

American Psychosocial Oncology Society: http://apos-society.org/

Cancer Support Community: http://www.cancer-supportcommunity.org (Cancer Support Community provides the Cancer Support Helpline at 888.793.9355)

CancerCare: www.cancercare.org

National Cancer Institute: www.cancer.gov

Cancer.net, sponsored by ASCO: www.cancer.net

Follow-up at regular intervals or at transition points in illness is an essential part of the NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management and the NAM model for care of the whole patient.

Psychologic/Psychiatric Treatment by Mental Health Professionals

Management of expected distress symptoms is described on DIS-5 (page 1233).

Psychosocial Interventions

Psychosocial interventions have been effective in reducing distress and improving overall quality of life among patients with cancer.37,38 The 2007 NAM report noted that a strong evidence base supports the value of psychosocial interventions in cancer care.37 The review examined the range of interventions (psychologic, social, and pharmacologic) and their impact on any aspect of quality of life, symptoms, or survival. The extensive review found randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses supporting the conclusion that psychosocial aspects must be integrated into routine cancer care to give quality cancer care. More recent meta-analyses have come to similar conclusions, although more research is clearly needed.108–111 To date, psychosocial interventions for patients with cancer have disproportionately targeted women with breast cancer.108,109 More interventions targeting patients with other cancer types, or inclusion of mixed types, should be developed and evaluated. A meta-analysis including 53 studies of psychosocial interventions for patients with cancer (n= 12,323) showed that patients were more willing to participate in interventions delivered over the telephone versus in-person (P=.031) and when intervention is offered shortly after diagnosis versus later (P=.018).112 Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive psychotherapy, and family and couples therapy are 3 key types of psychotherapies discussed in the NAM report.37

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT involves practicing relaxation techniques, enhancing problem-solving skills, and identifying and correcting inaccurate thoughts associated with feelings. In randomized clinical trials, CBT and cognitive-behavioral stress management have been shown to effectively reduce psychologic symptoms (anxiety and depression) as well as physical symptoms (pain and fatigue) in patients with cancer.113–118 A Cochrane systematic review including 28 RCTs (n=3,940) showed that CBT interventions favorably address anxiety, depression, and mood disturbance in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer.119 The quality of the evidence was low for anxiety and depression and moderate for mood disturbance, however, indicating the need for studies to use higher quality intervention methods and validated instruments for measuring outcomes. Another meta-analysis including 14 articles on 10 RCTs on mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive therapy for 1,709 patients with breast cancer showed that these interventions have short-term effects on anxiety and depression, but effect sizes were small.120 A small RCT including 60 patients with cancer showed that a web-based CBT intervention may improve health-related quality of life, cancer-related distress, and anxious preoccupation after diagnosis.121

Ferguson et al122 have developed a brief CBT intervention (Memory and Attention Adaptation Training [MAAT]) aimed at helping breast cancer survivors manage cognitive dysfunction associated with adjuvant chemotherapy. In a randomized study, the investigators found that patients in the intervention arm had improved verbal memory performance and spiritual well-being.123 A randomized trial in which MAAT delivered through video conference was compared with supportive therapy in 47 survivors of breast cancer showed that MAAT improved self-reported perceived cognitive impairments (P=.02) and neuropsychological processing speed (P=.03), compared with supportive therapy.124

Supportive Psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy, aimed at flexibly meeting patients’ changing needs, is widely used. Different types of group psychotherapy have been evaluated in clinical trials among patients with cancer. Supportive-expressive group therapy has been shown to improve mood and pain control in patients with metastatic breast cancer.125 Hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors (n=264) who were experiencing survivorship problems and were randomized to an expressive helping intervention reported less distress, compared with survivors randomized to receive peer helping and neutral writing interventions (P<.05).126 Meaning-centered group psychotherapy, designed to help patients with advanced cancer sustain or enhance a sense of meaning, peace, and purpose in their lives (even as they approach the end of life), has also been shown to reduce psychologic distress among patients with advanced cancer.127–130 Dignity therapy has been assessed in an RCT of patients with a terminal diagnosis (not limited to cancer).131 Although no significant improvement was seen in levels of distress in patients receiving dignity therapy as measured by several scales, significant improvements in depression and self-reported aspects of quality of life were seen. An RCT for patients with renal cell carcinoma (n=277) showed that expressive writing reduces self-reported cancer-related symptoms (eg, pain, nausea, fatigue) and improves physical functioning.132 Secondary analyses from this study showed that the patients who benefited the most from the expressive writing intervention had both greater depressive symptoms and greater social support, as measured at baseline.133

Interventions incorporating internet support groups have become popular,134 with a Cochrane review including 6 studies with 492 women with breast cancer showing a small to moderate effect on depression, based on low-quality evidence.135 None of the 6 studies included in the review assessed emotional distress specifically, and results from 2 studies showed no significant effect on anxiety when comparing the intervention and control groups. Results of an RCT that included an internet support group with a prosocial component showed that this intervention did not reduce depression and anxiety in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer (n=184).136

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducational interventions are those that offer education to those with specific psychologic disorders or physical conditions. Psychoeducational interventions for patients with cancer may be general, such as providing information regarding stress management and healthy living (eg, nutrition, exercise),137,138 whereas other interventions may be more specific to the cancer type. A meta-analysis examining 19 psychoeducational interventions with 3,857 patients with cancer showed small posttreatment effects overall for emotional distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life.108 The only significant effects at long-term follow-up were for quality of life. Another meta-analysis including 11 studies of psychoeducational interventions for patients with gynecologic cancers showed effectiveness for depressive symptoms.139 Psychoeducation interventions that offer education regarding symptom management may also be effective when delivered via the internet.140–142

Family and Couples Therapy

A cancer diagnosis causes distress in partners and family members as well as the patient. Psychosocial interventions aimed at patients and their families together might lessen distress more effectively than individual interventions. In a longitudinal study of couples coping with early-stage breast cancer, mutual constructive communication was associated with less distress and more relationship satisfaction for both the patients and partners compared with demand/withdraw communication or mutual avoidance, suggesting that training in constructive communication would be an effective intervention.143

Family and couples therapy has not been widely studied in controlled trials. In an RCT in which 62 couples (patients with localized prostate cancer and their partners) were randomly assigned to receive cognitive existential couples therapy or usual care, adaptive and problem-focused coping was improved in couples receiving the therapy sessions, which in turn improved relationship cohesion, as well as relationship function in younger patients.144 In a pilot study, a telephone-based dyadic intervention for patients with advanced lung cancer and their families (n=39) improved depression, anxiety, and caregiver burden.145 In addition, an RCT showed that family-focused grief therapy can reduce the morbid effects of grief in families with terminally ill patients with cancer.146

Some systematic reviews have been performed to assess the efficacy of therapy involving patients’ close others. A meta-analysis including 12 RCTs showed that couple-based interventions for patients with cancer and their spouses improved depression, anxiety, and marital satisfaction, compared with control groups.147 A systematic review of 23 studies that assessed the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for couples affected by cancer found evidence that couples therapy might be at least as effective as individual therapy.148 Another systematic review examining the effects of 10 interventions for couples coping with breast cancer showed that, though results are mixed, these interventions tend to yield at least some benefit.149

Pharmacologic Interventions

Research suggests that antidepressants and antianxiety drugs are beneficial in the treatment of depression and anxiety in adult patients with cancer,150–153 though a recent Cochrane systematic review did not find a significant difference between antidepressants and placebo for treatment of depressive symptoms, based on low quality evidence.154 A systemic review including 38 studies showed that antidepressants are prescribed to 15.6% (95% CI, 13.3–18.3) of cancer patients, with prescriptions being common in women (22.6%; 95% CI, 16.0–31.0) and in patients with breast cancer (22.6%; 95% CI, 16.0–30.9).155 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, fluoxetine, paroxetine) are widely used for depression and anxiety symptoms, though tricyclic agents (eg, desipramine, doxepin) may also be used in patients with depression.154 Withdrawal from pharmacologic agents (eg, benzodiazepines, opioids, antidepressants, antianxiety drugs) should be managed with care and will vary based on the specific agent. Psychiatrists play a valuable role in the administration of and withdrawal from pharmacologic agents.

Exercise

Exercise during and after cancer treatment can improve cardiovascular fitness and strength and can have positive effects on balance, body composition, and quality of life.156–158 Small RCTs have shown that exercise may also improve mental health outcomes in patients with cancer and cancer survivors.159–161 A Cochrane systematic review including 9 RCTs (n=818) showed that aerobic exercise for patients with hematologic malignancies may reduce depression (standardized mean difference [SMD], 0.25; 95% CI, 0.00–0.50; P=.05) but not anxiety (P=.45).162 However, the quality of the evidence in this area is low, and larger RCTs and longer follow-up periods are needed. Cancer-related fatigue, which may be exacerbated by distress, is also positively impacted by exercise (see the NCCN Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue, available at NCCN.org).163,164

Complementary and/or Integrative Therapies

Regarding complementary and/or integrative therapies for patients with cancer, a systematic review showed that meditation, yoga, relaxation with imagery, massage, and music therapy may be helpful for patients with depressive disorders who have breast cancer.165,166 Music therapy, meditation, and yoga may also be used to reduce anxiety in patients with breast cancer.165,166 A systematic review including 52 randomized and quasi-randomized trials with 3,731 patients showed that music therapy benefits patients with anxiety (P<.001).167 Findings from this review also indicated that music therapy may positively affect patients with depression, but the quality of the evidence was low.

A meta-analysis including 16 RCTs with 930 patients with breast cancer showed that yoga may reduce depression (SMD, −0.17; 95% CI, −0.32 to −0.01; P<.001) and anxiety (SMD, −0.98; 95% CI, −1.38 to −0.57; P<.001) in these patients.168 However, the methodologic quality of the studies included in this review was generally low. A Cochrane review showed that, when compared with psychosocial or educational interventions, yoga may have at least short-term effects on depression (pooled SMD, −2.29; 95% CI, −3.97 to −0.61) and anxiety (pooled SMD, −2.21; 95% CI, −3.90 to −0.52).169 Large randomized studies are needed to investigate the potential impact of yoga on distress.

Based on this evidence, the panel recommends relaxation, meditation, and creative therapies such as art and music for patients experiencing distress.

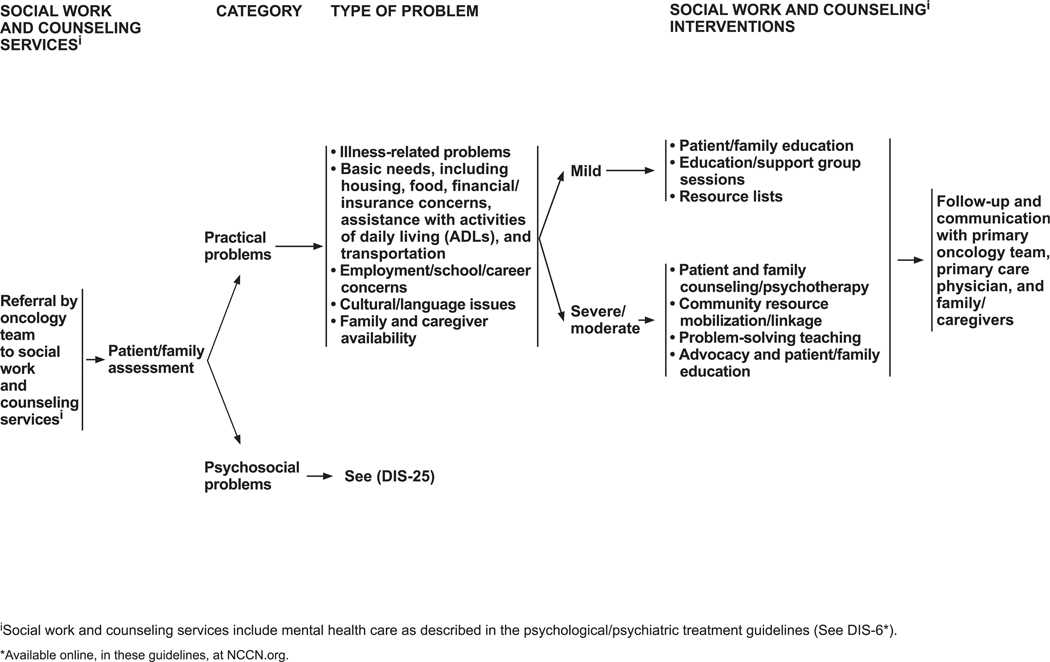

Social Work and Counseling Services

Social work and counseling interventions are recommended when a patient has a psychosocial or practical problem. Practical problems are illness-related concerns; basic needs (eg, housing, food, financial/insurance concerns, help with activities of daily living, transportation); employment, school, or career concerns; cultural or language issues; and family/caregiver availability. The guidelines outline interventions that vary according to the severity of the problem (see DIS-24, page 1236).

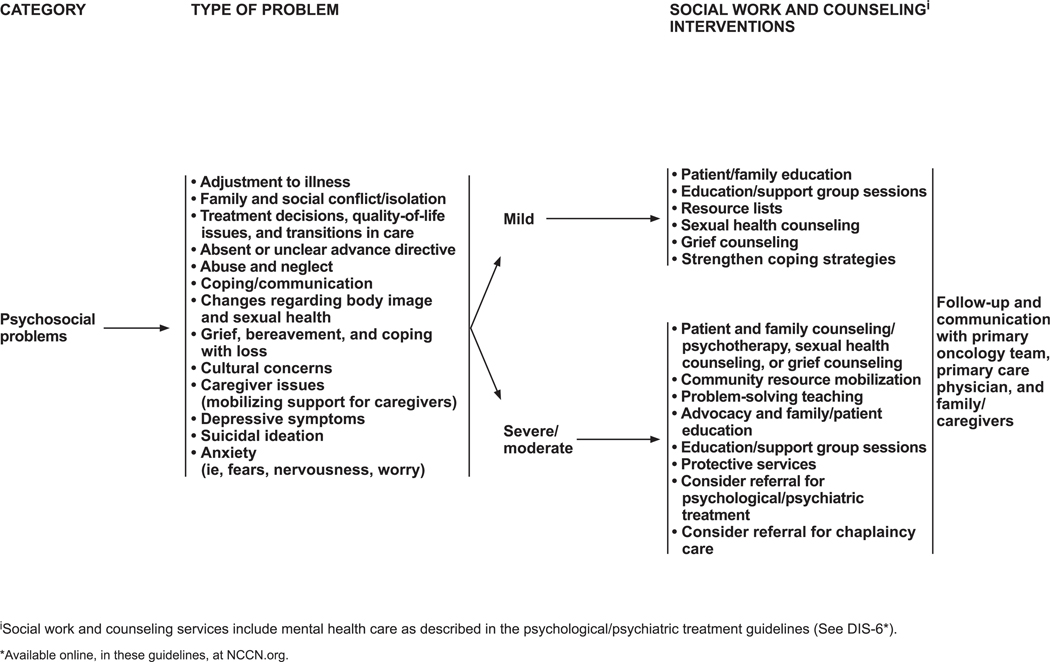

Common psychosocial problems are adjustment to illness; family conflicts and social isolation; difficulties in treatment decision-making; quality-of-life issues; difficulties with transitions in care; absent or unclear advance directive or other concerns about advance directives; domestic abuse and neglect; poor coping or communication skills; concerns about functional changes (eg, body image, sexual health); depressive symptoms and/or suicidal ideation; fears, nervousness, and worry; and issues pertaining to end of life and bereavement (including cultural and caregiver concerns).

Social work and counseling interventions for psychosocial problems are summarized on DIS-25 (page 1237). Social workers intervene in mild psychosocial problems by using patient and family education, support groups, and/or sexual health or grief counseling and by suggesting available local resources. Social workers can also help foster healthy coping strategies, such as problem solving, cognitive restructuring, and emotional regulation.170 For moderate to severe psychosocial problems, counseling and psychotherapy are used (including sexual health and grief counseling); community resources are mobilized; problem solving is taught; and advocacy, education, and protective services are made available.

Spiritual and Chaplaincy Care

Religiousness and spirituality are positively associated with mental health in patients with cancer,171 and attendance at religious services is associated with lower cancer-related mortality.172 Many patients use their religious and spiritual resources to cope with illness,173 and many cite prayer as a major help. In addition, the diagnosis of cancer can cause an existential crisis, making spiritual support of critical importance. Balboni et al174 surveyed 230 patients with advanced cancer treated at multiple institutions for whom first-line chemotherapy failed. Most patients (88%) considered religion as somewhat or very important. Nearly half of the patients (47%) reported receiving very minimal or no support at all from their religious community, and 72% reported receiving little or no support from their medical system.174 Importantly, patients receiving spiritual support reported a higher quality of life. Religiousness and spiritual support have also been associated with improved satisfaction with medical care. Astrow et al175 found that 73% of patients with cancer had spiritual needs, and that patients whose spiritual needs were not met reported lower quality of care and lower satisfaction with their care. A multi-institution study of 75 patients with cancer and 339 oncologists and nurses (the Religion and Spirituality in Cancer Care Study) found that spiritual care had a positive effect on patient-provider relationships and the emotional well-being of patients.176 However, a survey conducted in 2006 through 2009 found that most patients with advanced cancer never receive spiritual care from their oncology team.177 Spiritual needs may include searching for the meaning and purpose of life; searching for the meaning in experiencing a disease like cancer; being connected to others, a deity, and nature; maintaining access to religious/spiritual practices; spiritual well-being; talking about death and dying; making the most of one’s own life; and being independent and treated like a “normal person.”178

A meta-analysis including 12 studies with 1,878 patients showed that spiritual interventions improve quality of life (d=0.50; 95% CI, 0.20–0.79), but the effect was small at 3-to 6-month follow-up (d=0.14; 95% CI, −0.08–0.35).179 Another meta-analysis including 24 studies showed that existential interventions positively affected existential well-being, quality of life, hope, and self-efficacy, though results were moderated by intervention characteristics (eg, therapist’s professional background, intervention setting).180

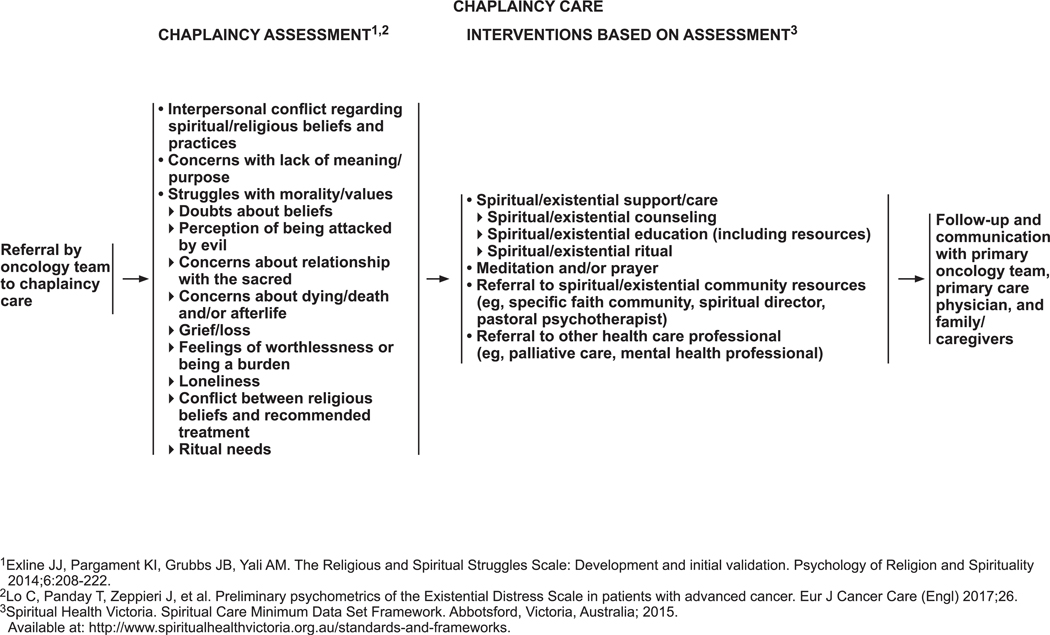

The panel has included chaplaincy care as part of psychosocial services (see DIS-26, page 1238). All patients should be referred to a chaplaincy professional when their problems are spiritual or religious in nature or when they request it. Guided by the Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale181 and the Existential Distress Scale,182 the panel identified issues that should be included as part of evaluation by a chaplain: interpersonal conflict regarding spiritual/religious beliefs and practices; concerns with lack of meaning and purpose; struggles with morality and values; doubts about beliefs; perceptions of being attacked by evil; concerns about one’s relationship with the sacred; concerns about death, dying, and the afterlife; grief and loss; feeling worthless or like a burden; loneliness; conflict between religious beliefs and treatment options; and ritual needs.

The panel has identified interventions that may be carried out based on this assessment (see DIS-26, page 1238). These interventions, which are based on recommendations by Spiritual Health Victoria (www.spiritualhealthvictoria.org.au/standards-and-frameworks), include spiritual/existential counseling, education, and rituals; meditation and/or prayer; referral to appropriate spiritual/existential community resources; and referral to other health care professionals (eg, palliative care, mental health professional) as needed.

The following guidelines on religion and spirituality in cancer care may also be useful for clinicians and patients:

National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Fourth Edition, 2018. These guidelines provide a framework to acknowledge the patient’s religious and spiritual needs in a clinical setting. Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care are included as 1 of the 8 clinical practice domains.

The National Cancer Institute’s comprehensive cancer information database (PDQ) has information on “Spirituality in Cancer Care” for patients (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/spirituality/Patient) and for health care professionals (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/spirituality/HealthProfessional).

Summary

Psychosocial care is an integral component of the clinical management of patients with cancer. The CoC’s accreditation standards include distress screening for all patients and referral for psychosocial care as needed. Screening for and treating distress in cancer benefits patients, their families/caregivers, and staff and helps improve the efficiency of clinic operations. For patients with cancer, integration of mental health and medical services is critically important. Spirituality and religion also play an important role in coping with the diagnosis and the illness for many patients with cancer.

The NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management recommend that each new patient be rapidly evaluated in the office or clinic waiting room for evidence of distress using the DT and Problem List as an initial global screen. A score of 4 or greater on the DT should trigger further evaluation by the oncologist or nurse and referral to an appropriate resource, if needed. The choice of which supportive care service is needed depends on the problem areas specified on the Problem List. Patients with practical and psychosocial problems should be referred to social workers; those with emotional or psychologic problems should be referred to mental health professionals including social workers; and those with spiritual concerns should be referred to certified chaplains. Physical concerns may be best managed by the medical team.

Education of patients and families is equally important to encourage them to recognize that control of distress is an integral part of their total cancer care. The patient version of the NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management is a useful tool to accomplish this (available at NCCN.org).

Individual Disclosures for the NCCN Distress Management Panel

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support/Data Safety Monitoring Board |

Scientific Advisory Boards, Consultant, or Expert Witness |

Promotional Advisory Boards, Consultant, or Speakers Bureau |

Specialties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbara Andersen, PhD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Ilana Braun, MD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| William S. Breitbart, MDa | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology; Internal Medicine; and Supportive Care |

| Benjamin W. Brewer, PsyD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Luke O. Buchmann, MD | None | None | None | Surgery/Surgical Oncology |

| Matthew M. Clark, PhD | None | Roche Laboratories, Inc. | None | Psychiatry/Psychology, and Supportive Care |

| Molly Collins, MD | None | None | None | Supportive Care |

| Cheyenne Corbett, PhD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Kristine A. Donovan, PhD, MBA | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Stewart Fleishman, MD | None | None | None | Supportive Care, and Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Sofia Garcia, PhD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Donna B. Greenberg, MD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology, and Internal Medicine |

| George F. Handzo, MA, MDiv | None | None | None | Supportive Care |

| Laura Hoofring, MSN, APRN | None | None | None | Nursing; Psychiatry/Psychology; and Medical Oncology |

| Chao-Hui Huang, PhD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Robin Lally, PhD, MS, RN | Pfizer Inc. | NIH/NINR Study Section, and Oncology Nursing Society Foundation | None | Nursing |

| Sara Martin, MD | None | None | None | Supportive Care |

| Lisa McGuffey, PhD, JD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| William Mitchell, MD | None | None | None | Medical Oncology, and Supportive Care |

| Laura J. Morrison, MD | None | None | None | Supportive Care |

| Megan Pailler, PhD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Oxana Palesh, PhD, MPH | None | Adsalutem; Medable, Inc.; Shook Hardy and Bacon; and Yasamin Miller Group (YSM) SAMSHA | None | Psychiatry/Psychology, and Supportive Care |

| Francine Parnes, JD, MA | None | None | None | Patient Advocacy |

| Janice P. Pazar, PhD, RN | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology, and Supportive Care |

| Laurel Ralston, DO | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Michelle B. Riba, MD, MSa | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Jaroslava Salman, MD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Moreen M. Shannon-Dudley, MSW | None | None | None | Supportive Care |

| Alan D. Valentine, MD | None | None | None | Psychiatry/Psychology |

The NCCN Guidelines Staff have no conflicts to disclose.

The following individuals have disclosed that they have an employment/governing board, patent, equity, or royalty:

William S. Breitbart, MD: Oxford University Press

Michelle B. Riba, MD, MS: Springer Publishing

NCCN CATEGORIES OF EVIDENCE AND CONSENSUS

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

PLEASE NOTE

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of evidence and consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representations or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

The complete NCCN Guidelines for Distress Management are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

© National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2019. All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Disclosures for the NCCN Distress Management Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines Panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Distress Management Panel members can be found on page 1249. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available at NCCN.org.)

The complete and most recent version of these guidelines is available free of charge at NCCN.org.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller K, Massie MJ. Depression and anxiety. Cancer J 2006;12:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins NA, Soman A, Buchanan Lunsford N, et al. Use of medications for treating anxiety and depression in cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funk R, Cisneros C, Williams RC, et al. What happens after distress screening? Patterns of supportive care service utilization among oncology patients identified through a systematic screening protocol. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2861–2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebber AM, Jansen F, Cuijpers P, et al. Screening for psychological distress in follow-up care to identify head and neck cancer patients with untreated distress. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2541–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MehnertA Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, et al. One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology 2018;27:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traeger L, Cannon S, Keating NL, et al. Race by sex differences in depression symptoms and psychosocial service use among non-Hispanic black and white patients with lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32: 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlsen K, Jensen AB, Jacobsen E, et al. Psychosocial aspects of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2005;47:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer 2006;107:2924–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol 2010;8:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 2012;141:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW, Carey ML, et al. Prevalence and associates of psychological distress in haematological cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:4413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfonsson S, Olsson E, Hursti T, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical variables associated with psychological distress 1 and 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2016;24: 4017–4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howren MB, Christensen AJ, Karnell LH, et al. Psychological factors associated with head and neck cancer treatment and survivorship: evidence and opportunities for behavioral medicine. J ConsultClin Psychol 2013;81:299–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes AF, Yeo TP, Leiby B, et al. Pancreatic cancer-associated depression: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas 2018;47: 1065–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringwald J, Wochnowski C, Bosse K, et al. Psychological distress, anxiety, and depression of cancer-affected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: a systematic review. J Genet Couns 2016;25:880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirschberg AM, Chan-Smutko G, Pirl WF. Psychiatric implications of cancer genetic testing. Cancer 2015;121:341–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mausbach BT, Schwab RB, Irwin SA. Depression as a predictor of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) in women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin C, Clark R, Tu P, et al. Breast cancer oral anti-cancer medication adherence: a systematic review of psychosocial motivators and barriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;165:247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BultzBD HollandJC. Emotional distress in patients with cancer :the sixth vital sign. Community Oncol 2006;3:311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: making the case for economic analyses. Psychooncology 2004;13:837–849., discussion 850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Moran SM, et al. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2017;123: 4720–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004;2004:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kissane D. Beyond the psychotherapy and survival debate: the challenge of social disparity, depression and treatment adherence in psychosocial cancer care. Psychooncology 2009;18:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1310–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batty GD, Russ TC, Stamatakis E, et al. Psychological distress in relation to site specific cancer mortality: pooling of unpublished data from 16 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2017;356: j108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmack CL, Basen-Engquist K, Gritz ER. Survivors at higher risk for adverse late outcomes due to psychosocial and behavioral risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:2068–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Cancer distress screening. Needs, models, and methods. J Psychosom Res 2003;55:403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Bybee D, et al. A practice-based evaluation of distress screening protocol adherence and medical service utilization. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson LE, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, et al. Screening for distress in lung and breast cancer outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4884–4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 2001;84: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland JC. American Cancer Society Award lecture. Psychological care of patients: psycho-oncology’s contribution. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21(23, Suppl)253s–265s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland JC, (ed), Spiritual assessment, screening, and intervention in Psycho Oncology. Oxford University Press, New York: 1998:pp. 790-. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland JC, Greenberg DB, Hughes MK. Quick Reference for Oncology Clinicians: The Psychiatric and Psychological Dimensions of Cancer Symptom Management Oncology. IPOS Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adler NE, Page NEK. Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2008. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobsen PB, Jim HS. Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: achievements and challenges. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:214–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holland JC, Lazenby M, Loscalzo MJ. Was there a patient in your clinic today who was distressed? J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13: 1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon DB, Dahl JL, Miaskowski C, et al. American pain society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1574–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazenby M, Ercolano E, Grant M, et al. Supporting commission on cancer-mandated psychosocial distress screening with implementation strategies. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:e413–e420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Padgett L, et al. Institutional capacity to provide psychosocial oncology support services: A report from the Association of Oncology Social Work. Cancer 2016;122:1937–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deshields T, Kracen A, Nanna S, et al. Psychosocial staffing at National Comprehensive Cancer Network member institutions: data from leading cancer centers. Psychooncology 2016;25:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez MA, Tortorella F, St John C. Improving psychosocial care for improved health outcomes. J Healthc Qual 2010;32:3–12, quiz 12–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frost GW, Zevon MA, Gruber M, et al. Use of distress thermometers in an outpatient oncology setting. Health Soc Work 2011;36:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fulcher CD, Gosselin-Acomb TK. Distress assessment: practice change through guideline implementation. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2007; 11:817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammelef KJ, Friese CR, Breslin TM, et al. Implementing distress management guidelines in ambulatory oncology: a quality improvement project. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18(Suppl):31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammonds LS. Implementing a distress screening instrument in a university breast cancer clinic: a quality improvement project. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendrick SS, Cobos E. Practical model for psychosocial care. J Oncol Pract 2010;6:34–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loscalzo M, Clark KL, Holland J. Successful strategies for implementing biopsychosocial screening. Psychooncology 2011;20:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehta A, Hamel M. The development and impact of a new Psychosocial Oncology Program. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1873–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner LI, Spiegel D, Pearman T. Using the science of psychosocial care to implement the new american college of surgeons commission on cancer distress screening standard. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11: 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ercolano E, Hoffman E, Tan H, et al. Managing psychosocial distress: lessons learned in optimizing screening program implementation. Oncology (Williston Park) 2018;32:488–490, 492–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavernier SS, Beck SL, Dudley WN. Diffusion of a Distress Management Guideline into practice. Psychooncology 2013;22:2332–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knies AK, Jutagir DR, Ercolano E, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing the commission on cancer’s distress screening program standard. Palliat Support Care 2019;17:253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neuss MN, Desch CE, McNiff KK, et al. A process for measuring the quality of cancer care: the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6233–6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobson JO, Neuss MN, McNiff KK, et al. Improvement in oncology practice performance through voluntary participation in the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1893–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blayney DW, McNiff K, Hanauer D, et al. Implementation of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative at a university comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3802–3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1160–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fann JR, Ell K, Sharpe M. Integrating psychosocial care into cancer services. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lazenby M. The international endorsement of US distress screening and psychosocial guidelines in oncology: a model for dissemination. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2014;12:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lowery AE, Holland JC. Screening cancer patients for distress: guidelines for routine implementation. Community Oncol 2011;8:502–505. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Groff S, Holroyd-LeducJ, White D, et al. Examining the sustainability of Screening for Distress, the sixth vital sign, in two outpatient oncology clinics: A mixed-methods study. Psychooncology 2018;27:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ehlers SL, Davis K, Bluethmann SM, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship. Transl Behav Med 2018;9:282–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith SK, Loscalzo M, Mayer C, et al. Best practices in oncology distress management: beyond the screen. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018; 38:813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Emotional distress: the sixth vital sign in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6440–6441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bultz BD, Groff SL, Fitch M, et al. Implementing screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: a Canadian strategy for changing practice. Psychooncology 2011;20:463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fitch MI, Ashbury F, Nicoll I. Reflections on the implementation of screening for distress (sixth vital sign) in Canada: key lessons learned. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:4011–4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dolbeault S, Boistard B, Meuric J, et al. Screening for distress and supportive care needs during the initial phase of the care process: a qualitative description of a clinical pilot experiment in a French cancer center. Psychooncology 2011;20:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grassi L, Rossi E, Caruso R, et al. Educational intervention in cancer outpatient clinics on routine screening for emotional distress: an observational study. Psychooncology 2011;20:669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Okuyama T, Kizawa Y, Morita T, et al. Current status of distress screening in designated cancer hospitals: a cross-sectional nationwide survey in Japan. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016;14:1098–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Nuenen FM, Donofrio SM, Tuinman MA, et al. Feasibility of implementing the ‘Screening for Distress and Referral Need’ process in 23 Dutch hospitals. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meijer A, Roseman M, Delisle VC, et al. Effects of screening for psychological distress on patient outcomes in cancer: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bultz BD, Carlson LE. A commentary on ‘effects of screening for psychological distress on patient outcomes in cancer: a systematic review’. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hollingworth W, Metcalfe C, Mancero S, et al. Are needs assessments cost effective in reducing distress among patients with cancer? A randomized controlled trial using the Distress Thermometer and Problem List. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3631–3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carlson LE. Screening alone is not enough: the importance of appropriate triage, referral, and evidence-based treatment of distress and common problems. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3616–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitchell AJ. Screening for cancer-related distress: when is implementation successful and when is it unsuccessful? Acta Oncol 2013;52: 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Braeken AP, Kempen GI, Eekers DB, et al. Psychosocial screening effects on health-related outcomes in patients receiving radiotherapy. A cluster randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology 2013;22: 2736–2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4670–4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shinn EH, Valentine A, Baum G, et al. Comparison of four brief depression screening instruments in ovarian cancer patients: Diagnostic accuracy using traditional versus alternative cutpoints. Gynecol Oncol 2017;145:562–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Syrjala KL, Sutton SK, Jim HS, et al. Cancer and treatment distress psychometric evaluation over time: a BMT CTN 0902 secondary analysis. Cancer 2017;123:1416–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Braeken AP, Lechner L, Eekers DB, et al. Does routine psychosocial screening improve referral to psychosocial care providers and patient-radiotherapist communication? A cluster randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mitchell AJ, Kaar S, Coggan C,et al. Acceptability of common screening methods used to detect distress and related mood disorders-preferences of cancer specialists and non-specialists. Psychooncology 2008;17:226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mitchell AJ. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: a review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wells-Di Gregorio S, Porensky EK, Minotti M, et al. The James Supportive Care Screening: integrating science and practice to meet the NCCN guidelines for distress management at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Psychooncology 2013;22:2001–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Berry DL, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Electronic self-report assessment for cancer and self-care support: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, et al. Online screening for distress, the6th vital sign, in newly diagnosed oncology outpatients: randomised controlled trial of computerised vs personalised triage. Br J Cancer 2012; 107:617–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loscalzo M, Clark K, Dillehunt J, et al. Support Screen: a model for improving patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw2010;8:496–504. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lundy JJ, Coons SJ, Aaronson NK. Testing the measurement equivalence of paper and interactive voice response system versions of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 2014;23:229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma X, Zhang J, Zhong W, et al. The diagnostic role of a short screening tool-the distress thermometer: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1741–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ploos van Amstel FK, Tol J, Sessink KH, et al. A specific distress cutoff score shortly after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Nurs 2017;40: E35–E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chambers SK, Zajdlewicz L, Youlden DR, et al. The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. Psychooncology 2014;23: 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deng YT, Zhong WN, Jiang Y. Measurement of distress and its alteration during treatment in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2014;36:1077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grassi L, Johansen C, Annunziata MA, et al. Screening for distress in cancer patients: a multicenter, nationwide study in Italy. Cancer 2013; 119:1714–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. The Distress Thermometer and its validity: a first psychometric study in Indonesian women with breast cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e56353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lim HA, Mahendran R, Chua J, et al. The Distress Thermometer as an ultra-short screening tool: a first validation study for mixed-cancer outpatients in Singapore. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55:1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martínez P, Galdón MJ, Andreu Y, et al. The Distress Thermometer in Spanish cancer patients: convergent validity and diagnostic accuracy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3095–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thalén-Lindström A, Larsson G, Hellbom M, et al. Validation of the Distress Thermometer in a Swedish population of oncology patients; accuracy of changes during six months. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17: 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang Y, Zou L, Jiang M, et al. Measurement of distress in Chinese inpatients with lymphoma. Psychooncology 2013;22:1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, et al. Screening cancer patients’ families with the distress thermometer (DT): a validation study. Psychooncology 2008;17:959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lotfi-Jam K, Gough K, Schofield P, et al. Profile and predictors of global distress: can the DT guide nursing practice in prostate cancer? Palliat Support Care 2014;12:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Olesen ML, Hansen MK, Hansson H, et al. The distress thermometer in survivors of gynaecological cancer: accuracy in screening and association with the need for person-centered support. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Linehan K, Fennell KM, Hughes DL, et al. Use of the Distress Thermometer in a cancer helpline context: can it detect changes in distress, is it acceptable to nurses and callers, and do high scores lead to internal referrals? Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017;26:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wagner LI, Pugh SL, Small W Jr., et al. Screening for depression in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: Feasibility and identification of effective tools in the NRG Oncology RTOG 0841 trial. Cancer 2017;123: 485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]