Abstract

Background

Medical-related professions are at high suicide risk. However, data are contradictory and comparisons were not made between gender, occupation and specialties, epochs of times. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on suicide risk among health-care workers.

Method

The PubMed, Cochrane Library, Science Direct and Embase databases were searched without language restriction on April 2019, with the following keywords: suicide* AND (« health care worker* » OR physician* OR nurse*). When possible, we stratified results by gender, countries, time, and specialties. Estimates were pooled using random-effect meta-analysis. Differences by study-level characteristics were estimated using stratified meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicides, suicidal attempts, and suicidal ideation were retrieved from national or local specific registers or case records. In addition, suicide attempts and suicidal ideation were also retrieved from questionnaires (paper or internet).

Results

The overall SMR for suicide in physicians was 1.44 (95CI 1.16, 1.72) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 93.9%, p<0.001). Female were at higher risk (SMR = 1.9; 95CI 1.49, 2.58; and ES = 0.67; 95CI 0.19, 1.14; p<0.001 compared to male). US physicians were at higher risk (ES = 1.34; 95CI 1.28, 1.55; p <0.001 vs Rest of the world). Suicide decreased over time, especially in Europe (ES = -0.18; 95CI -0.37, -0.01; p = 0.044). Some specialties might be at higher risk such as anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners and general surgeons. There were 1.0% (95CI 1.0, 2.0; p<0.001) of suicide attempts and 17% (95CI 12, 21; p<0.001) of suicidal ideation in physicians. Insufficient data precluded meta-analysis on other health-care workers.

Conclusion

Physicians are an at-risk profession of suicide, with women particularly at risk. The rate of suicide in physicians decreased over time, especially in Europe. The high prevalence of physicians who committed suicide attempt as well as those with suicidal ideation should benefits for preventive strategies at the workplace. Finally, the lack of data on other health-care workers suggest to implement studies investigating those occupations.

Introduction

Suicide risk was increased in certain occupational groups, especially in medical-related professions [1]. Physicians, and other health-care workers such as nurses [2,3], were considered like high risk group of suicide in different countries [4,5,6], especially for women [6,7,8]. Indeed, despite considerably higher risk of suicides in men than women in the general population [9], female doctors have higher suicide rates than men [10], putatively because of their social family role [11], or a poor status integration within the profession [7]. Suicide rate in physicians was also not homogenous in all countries [12], and physicians’ satisfaction has been reported to change between different epochs of times [13]. Physicians working conditions varied substantially between countries and over contemporary times, these factors were never investigated in relationships with suicide in physicians. For example, there were tentative to regulate working time of physicians over the recent years, such as in Europe with its European Working Time Directive (EWTD) [14]. Some specialties have been suggested to be particularly at risk of suicides [15,16] with occupational factors individualized in different medical or surgical specialties: heavy workload and working hours involved in the job such as long shifts and unpredictable hours (with the sleep deprivation associated) [17], stress of the situations (life and death emergencies) [18], and easy access to a means of committing suicide [19]. To implement coordinated and synergistic preventive strategies, we need to identify physicians in mental health suffering [20], therefore statistical analyses on suicide attempts and suicidal ideation were necessary. However, robust statistics on health-care workers were desperately lacking for suicides, suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. The latest meta-analysis summarized physicians suicide risk before 2000s [6], we need for updated synthesis of literature. We hypothesized that 1) physicians are more at risk to commit suicide than the general population, 2) women physicians are more at risk to commit suicide than their male counterparts, 3) some countries would have higher rates of suicide in physicians, 4) with an improvement over time, 5) some medical or surgical specialties would be at higher risk of suicide, 6) physicians would also exhibit higher rates of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation, and 7) other health care workers would also be at risk of suicide.

Thus, we aimed to conduct a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis to provide evidence-based data for suicide risk among health-care workers, considering gender, geographic zone, epoch of time, medical and surgical specialties. Finally, we wanted to expand our study to suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

Methods

Search strategy and study eligibility

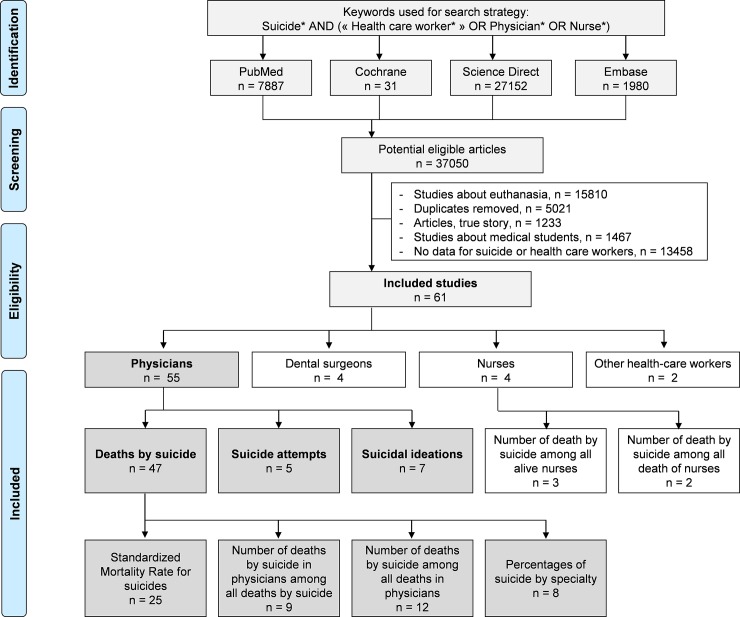

We reviewed all studies involving suicides, suicide attempts or suicidal ideation in health-care workers. Students were excluded because of the difference in responsibilities in comparisons with health-care workers, and because of the existence of previous recent meta-analyses focusing specifically on health-care students [21,22,23,24]; we included interns because they were not included in the aforementioned meta-analyses on prevalence of suicides, suicide attempts or suicidal ideation, and because they could have similar responsibilities to senior practitioners. The PubMed, Cochrane Library, Science Direct and Embase databases were searched on April 2019, with the following keywords: suicide* AND (« health care worker* » OR physician* OR nurse*). The search was not limited by years or languages. To be included, articles had to be peer-reviewed and to describe original empirical data on suicides, suicide attempt or suicidal ideation in health-care workers. When data were available, we also collected data from a control group (such as general population) for comparisons purposes. In addition, reference lists of all publications meeting the inclusion criteria will be manually searched to identify any further studies not found through digital research. The search strategy was presented in Fig 1. Three authors (Claire Aubert, Valentin Navel and Frederic Dutheil) conducted all literature searches, and separately reviewed the abstracts and decided the suitability of the articles for inclusion. Two others authors (Bruno Pereira and Martial Mermillod) have been asked to review the articles when consensus on suitability was debated. Then all authors reviewed the eligible articles.

Fig 1. Search strategy.

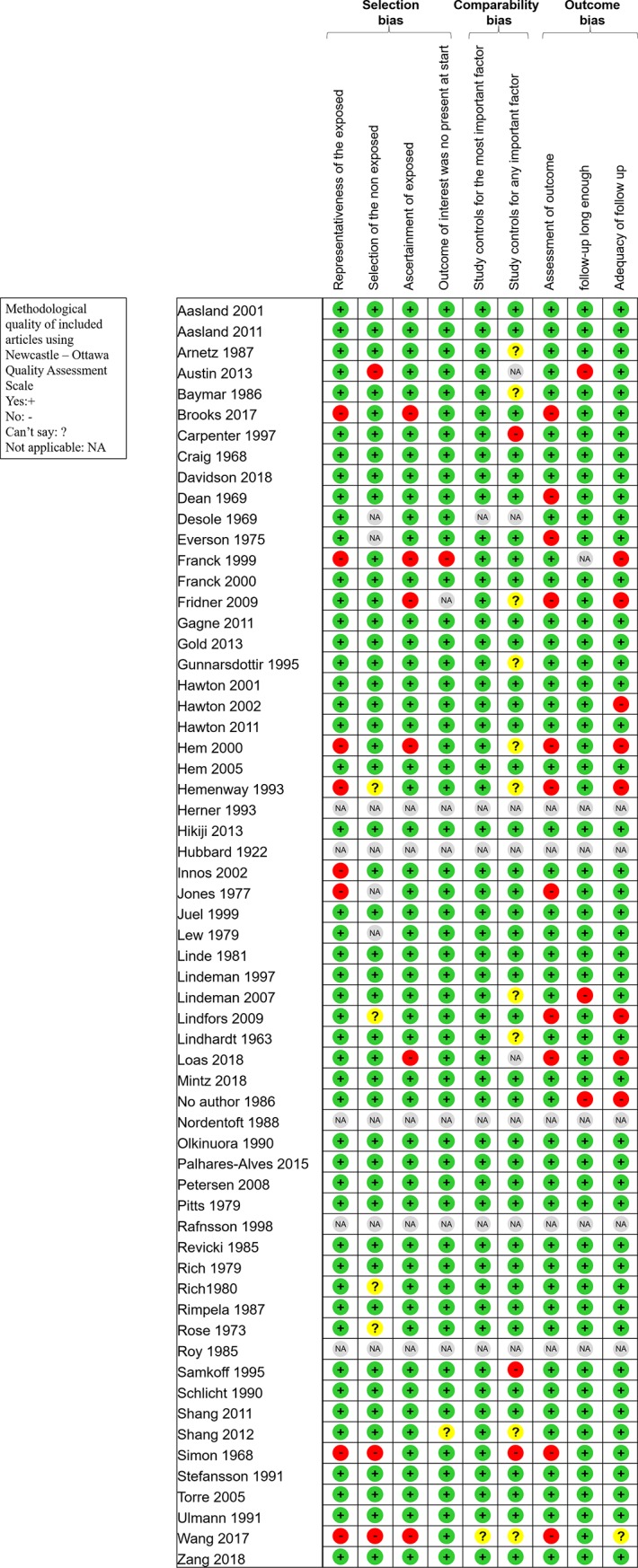

Quality of assessment

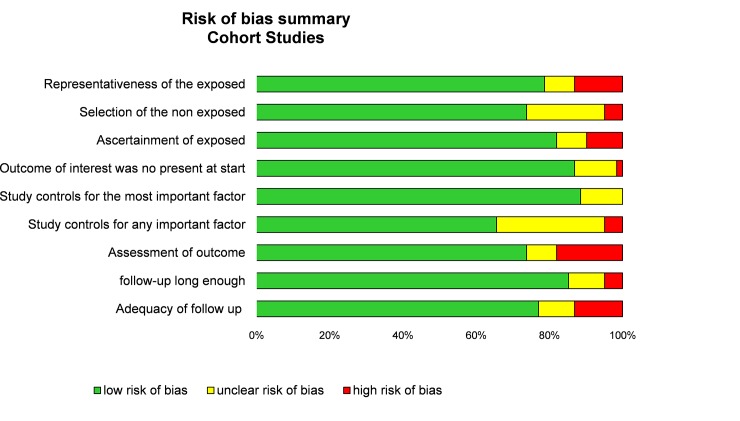

Although not designed for quantifying the integrity of studies [25], the “STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) criteria [26] and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) were used to check the quality of articles [27]. The maximum score in STROBE criteria was 30 with assessment of 22 items, in NOS criteria was 9 with assessment of 8 items (one star for each item within the selection and exposure category and a maximum of two stars for comparability) (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig 2. Methodological quality of included articles using Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.

Fig 3. Summary bias risk of included articles using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale model.

Statistical considerations

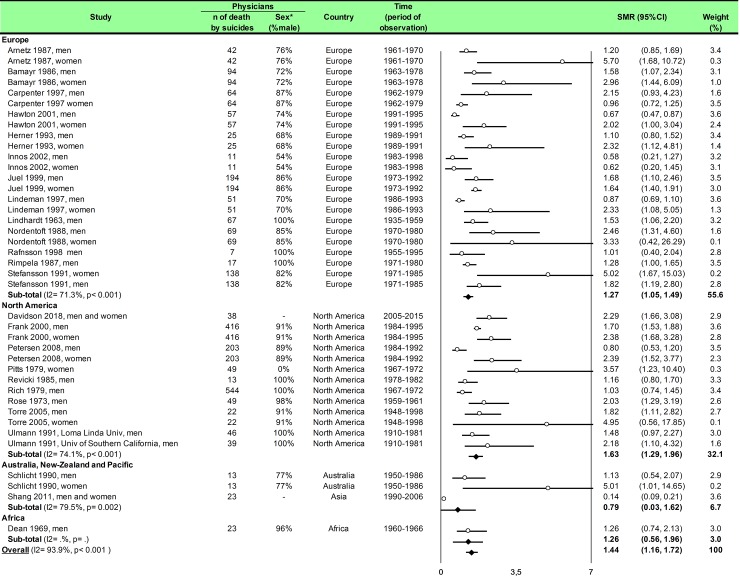

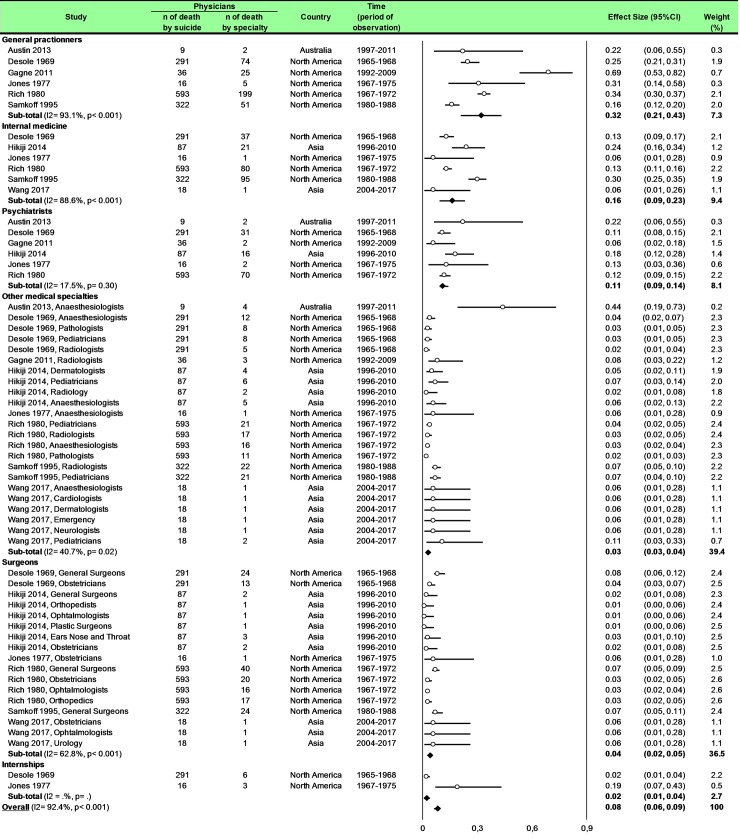

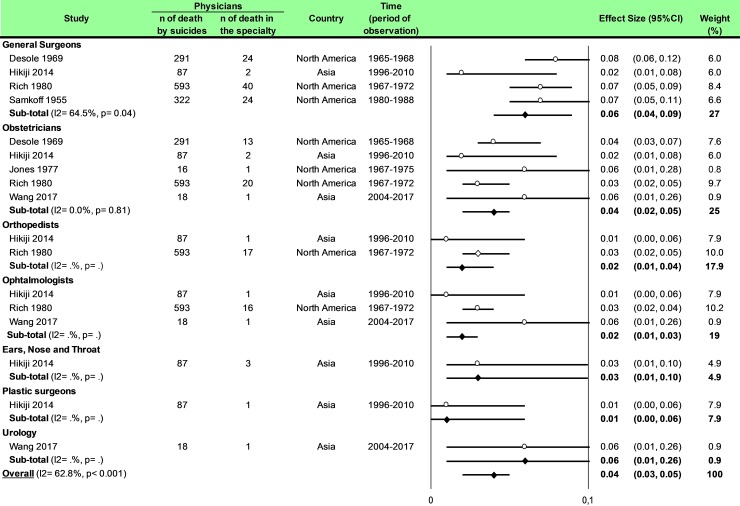

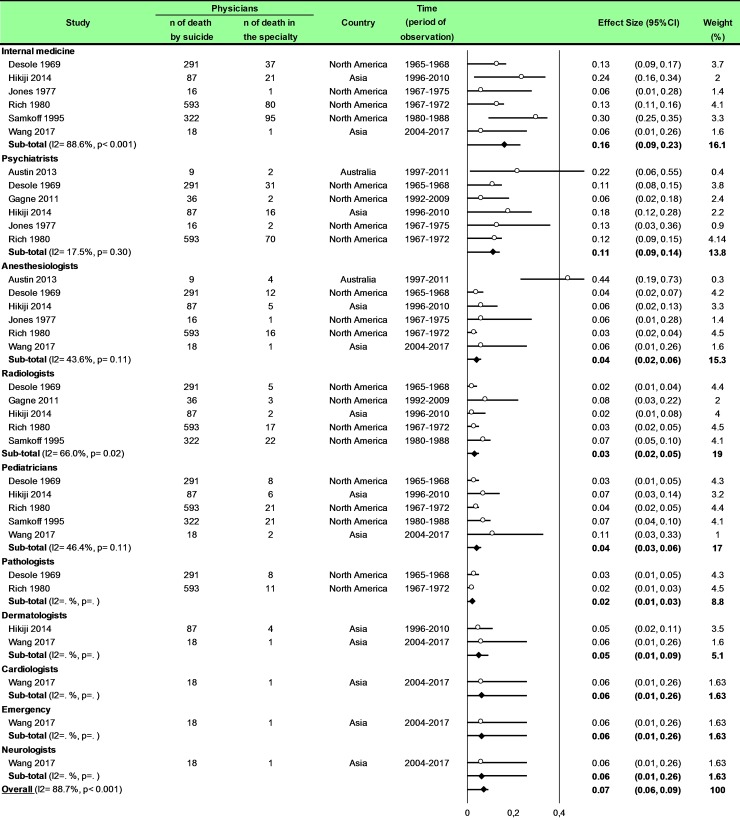

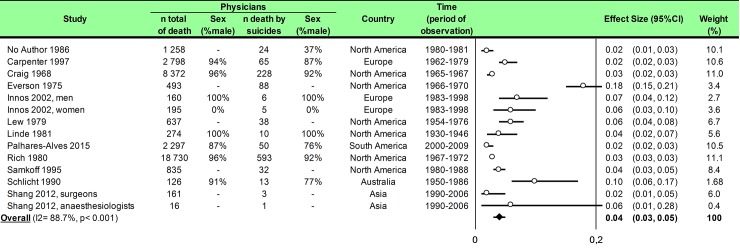

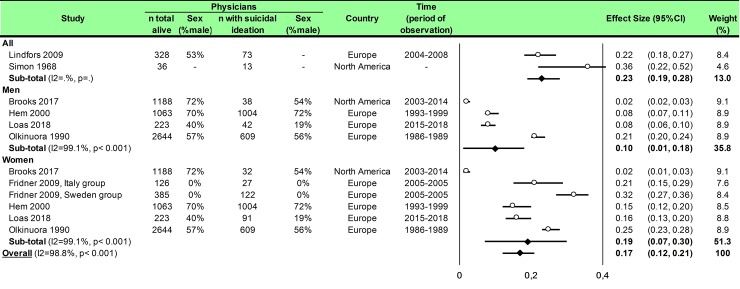

Statistical analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (version 2, Biostat Corporation) [28,29,30] and Stata software (version 13, StataCorp, College Station, US) [28,29,31]. Main characteristics were summarized for each study sample and reported as mean (standard-deviation) and number (%) for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Statistical heterogeneity between results was assessed by examining forest plots, confidence intervals (CI) and using formal tests for homogeneity based on I2 statistic, which is the most common metric for measuring the magnitude of heterogeneity between studies and is easily interpretable. I2 values range between 0% and 100% and are typically considered low for <25%, moderate for 25–50%, and high for > 50%. Random effect meta-analysis (DerSimonian and Liard approach) were conducted when data could be pooled [32]. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We conducted: 1) meta-analyses on the Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) for suicides i.e. the ratio between the observed and expected number of death among physicians, stratified by sex (Fig 4; and Fig 5 for metaregressions), geographic zones (Fig 6), epochs of time, and by categories of specialties (main groups of specialities (Fig 7 and S1 Fig), surgical specialties (Fig 8 and S2 Fig), then medical specialities (Fig 9 and S3 Fig), 2) meta-analyses on the prevalence of health-care workers died by suicide among all health-care workers death (Fig 10), 3) meta-analyses on the prevalence of health-care workers died by suicide among all the deaths by suicide in the general population (S4 Fig), 4) meta-analyses on suicide attempts (S5 Fig) and suicidal ideation (Fig 11). Effect-size was estimated for quantitative endpoints as number of physicians having done suicide attempt and number of physicians with suicidal ideation. A scale for ES has been suggested with 0.8 reflecting a large effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.2 a small effect [33]. When possible (sufficient sample size), meta-regressions were proposed to study relation between prevalence and epidemiological relevant parameters determined according to the literature: sex, geographic zone, epoch of time (for studies with a follow-up over several consecutive years, we based our statistics on the mean year of epoch of time). Results were expressed as regression coefficient and 95% CI.

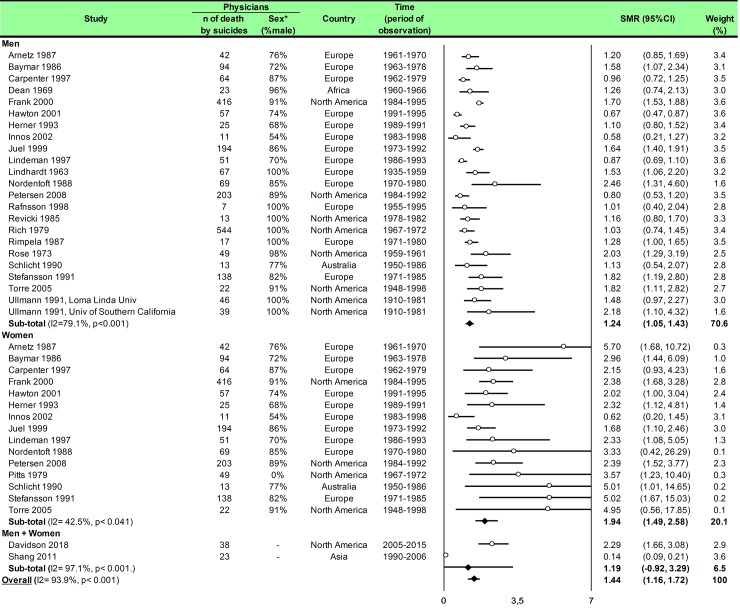

Fig 4. Meta-analysis of standardized mortality rate for suicides among physicians by gender.

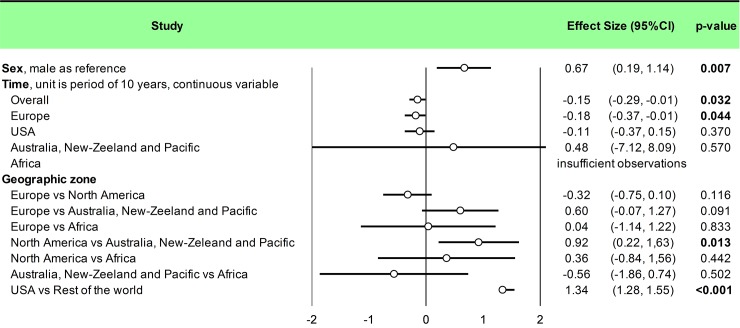

Fig 5. Meta-regression of standardized mortality rate for suicides among physicians.

Fig 6. Meta-analysis of standardized mortality rate for suicides by geographic zones.

Fig 7. Meta-analysis of percentages of suicide in physicians by group of specialties.

Fig 8. Meta-analysis of percentages of suicide in physicians by category of surgical specialties.

Fig 9. Meta-analysis of percentages of suicide in physicians by category of medical specialties.

Fig 10. Meta-analysis of prevalence of physicians died by suicide among all deaths in physicians.

Fig 11. Meta-analysis of prevalence of physicians with suicidal ideation among all the physicians.

Results

An initial search produced a possible 37050 articles (Fig 1). Removal of duplicates and use of the selection criteria reduced the search to 61 articles [1,2,5,7,8,15,16,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. In those 61 articles, 55 articles were on physicians [1,5,7,8,15,16,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,82,83,84,85], four on dental surgeons [55,56,62,70], four on nurses [2,79,80,86], and two on other health-care workers [70,87]. Among those 55 on physicians, 47 reported data on deaths by suicide [1,5,7,8,15,16,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,82,83], five on suicide attempts [47,73,75,77,85], and seven on suicidal ideation [74,75,76,77,78,84,85]. In those 47 articles on deaths by suicide among physicians, 25 described SMR for suicide [7,8,41,46,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,82], eight reported percentages of suicide by specialty [15,16,40,43,45,47,51,83], 12 reported the number of physicians died by suicide among all deaths in physicians [16,39,41,42,44,46,48,49,50,51,52,53], and nine reported the number of physicians died by suicide among all the deaths by suicide in the general population [1,5,15,34,35,36,37,38,82]. As there are few exploitable studies about dental surgeons, nurses and other health-care workers, we won’t treat them in that meta-analysis.

More details on study characteristics (Table 1), quality of articles (Figs 2 and 3), method of sampling for markers analysis, inclusion and exclusion criteria, characteristics of participants, outcomes and aims of the studies, and study designs of included articles are described in S1 Appendix.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

CI, Confidence Interval; n, Number; SMR, Standardized Mortality Ratio; USA, United States of America.

| Time Period | Total | Suicides | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Continent | Physicians–n (%) | Death–n (%) | Mortality–SMR (95CI) | Attempts—n | Thoughts—n | Specialities | ||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| Aasland 2001 | Norway | Europe | 1960–1993 | 73 (89) | 9 (11) | No specified | ||||||||

| Aasland 2011 | Norway | Europe | 1960–2000 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Arnetz 1987 | Sweden | Europe | 1961–1970 | 32 (76) | 10 (24) | 1,2 (0.85, 1.69) | 5,7 (1.68, 10.7) | No specified | ||||||

| Austin 2013 | Australia | Australia, New-Zealand and Pacific | 1997–2011 | 6 (66) | 3 (34) | Anaesthesiologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners, general surgeons | ||||||||

| Bamayr 1986 | Germany | Europe | 1963–1978 | 67 (71) | 27 (29) | 1,58 (1.07, 2.34) | 2,96 (1.44, 6.09) | No specified | ||||||

| Brooks 2017 | USA | North America | 2003–2014 | 1188 (72) | 544 (28) | 38 | 32 | No specified | ||||||

| Carpenter 1997 | Great Britain | Europe | 1962–1979 | 56 (87) | 8 (13) | 0,96 (0.72, 1.25) | 2,15 (0.93, 4.23) | No specified | ||||||

| Craig 1968 | USA | North America | 1965–1967 | 211 | 17 | No specified | ||||||||

| Davidson 2018 | USA | North America | 2005–2015 | 2,29 (1.66, 3.08) | 2,29 (1.66, 3.08) | No specified | ||||||||

| Dean 1969 | South Africa | Africa | 1960–1966 | 22 (96) | 1 (4) | 1,26 (0.74, 2.13) | No specified | |||||||

| Desole 1969 | USA | North America | 1965–1968 | General practitioners, general surgeons, internal medicine, psychiatrists, obstetricians, anaesthesiologists, pathology, paediatrics, radiology, internships | ||||||||||

| Everson 1975 | USA | North America | 1966–1970 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Frank 1999 | USA | North America | 1993–1994 | 0 | 4501 (100) | 61 | No specified | |||||||

| Frank 2000 | USA | North America | 1984–1995 | 379 (91) | 37 (9) | 1,7 (1.53, 1.88) | 2,38 (1.69, 3.28) | No specified | ||||||

| Fridner 2009 | Sweden and Italy | Europe | 2005–2005 | 0 | 385 (100) | 122 | No specified | |||||||

| Gagne 2011 | Quebec | North America | 1992–2009 | 29 (80) | 7 (20) | General practitioners, radiology, psychiatrists | ||||||||

| Gold 2013 | USA | North America | 2003–2008 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Gunnarsdottir 1995 | Iceland | Europe | 1920–1979 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Hawton 2001 | Great Britain | Europe | 1991–1995 | 42 (74) | 15 (26) | 0,67 (0.47, 0.87) | 2,02 (1.00, 3.04) | No specified | ||||||

| Hawton 2002 | England and Wales | Europe | 1994–1997 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Hawton 2011 | Danish | Europe | 1981–2006 | 131 (80) | 32 (20) | No specified | ||||||||

| Hem 2000 | Norway | Europe | 1993–1999 | 722 (72) | 282 (28) | 7 | 9 | 61 | 43 | No specified | ||||

| Hem 2005 | Norway | Europe | 1960–1990 | 98 (88) | 13 (22) | No specified | ||||||||

| Hemenway 1993 | USA | North America | 1976–1988 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Herner 1993 | Sweden | Europe | 1989–1991 | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.52) | 2,32 (1.12, 4.81) | No specified | ||||||

| Hikiji 2014 |

Japan | Asia | 1996–2010 | 68 (79) | 19 (21) | Internal medicine, dermatologists, paediatrics, psychiatrists, general surgeons, orthopaedists, ophthalmology, plastic surgeons, ENT, obstetricians, radiology, anaesthesiologists | ||||||||

| Hubbard 1922 | USA | North America | 1921 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Innos 2002 | Estonia | Europe | 1983–1998 | 6 (54) | 5 (46) | 0,58 (0.21, 1.27) | 0,62 (0.20, 1.45) | No specified | ||||||

| Jones 1977 | USA | North America | 1967–1975 | 11 | 5 | General practitioners, anaesthesiologists, internal medicine, obstetricians, psychiatrists, general surgeons, internships | ||||||||

| Juel 1999 | Danish | Europe | 1973–1992 | 168 (86) | 26 (14) | 1.64 (1.40, 1.91) | 1.68 (1.10, 2.46) | No specified | ||||||

| Lew 1976 | USA | North America | 1954–1976 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Linde 1981 | USA | North America | 1930–1946 | 274 (100) | 0 | 10 | 0 | No specified | ||||||

| Lindeman 1997 | Finland | Europe | 1986–1993 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Lindeman 2007 | Finland | Europe | 1987–1988 | 2 (28) | 5 (72) | No specified | ||||||||

| Lindfors 2009 | Finland | Europe | 2004–2008 | 175 (53) | 153 (47) | No specified | ||||||||

| Lindhardt 1963 | Denmark | Europe | 1935–1959 | 1.53 (1.06, 2.20) | No specified | |||||||||

| Loas 2018 | Belgium | Europe | 2015–2018 | 223 (40) | 334 (60) | 5 | 9 | 42 | 91 | No specified | ||||

| No Author 1986 | USA | North America | 1980–1981 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Nordentoft 1988 | Netherlands | Europe | 1970–1980 | 59 (85) | 10 (15) | 2.46 (1.02, 3.42) | 3.33 (0.42, 26.3) | No specified | ||||||

| Olkinuora 1990 | Finland | Europe | 1986–1989 | 1582 (59) | 1062 (41) | 10 | 6 | 340 | 269 | No specified | ||||

| Palhares-Alves 2015 | Brazil | South America | 2000–2009 | 38 (76) | 12 (24) | No specified | ||||||||

| Petersen 2008 | USA | North America | 1984–1992 | 181 (89) | 22 (11) | 0.8 (0.53, 1.20) | 2.39 (1.52, 3.77) | No specified | ||||||

| Pitts 1979 | USA | North America | 1967–1972 | 751 | 49 | 3.57 (1.23, 10.4) | No specified | |||||||

| Rafnsson 1998 | Island | Europe | 1955–1995 | 7 (100) | 1.01 (0.40, 2.04) | No specified | ||||||||

| Revicki 1985 | USA | North America | 1978–1982 | 13 | 1.16 (0.80, 1.70) | No specified | ||||||||

| Rich 1979 | USA | North America | 1967–1972 | 17979 | 544 | 1.03 (0.74, 1.45) | No specified | |||||||

| Rich 1980 | USA | North America | 1967–1972 | 544 (92) | 49 (8) | General practitioners, internal medicine, general surgeons, psychiatrists, obstetricians, paediatrics, radiology, anaesthesiologists, pathology, ophthalmology, orthopaedists | ||||||||

| Rimpela 1987 | Finland | Europe | 1971–1980 | 17 | 1.28 (1.01, 1.65) | No specified | ||||||||

| Rose 1973 | USA | North America | 1959–1961 | 48 (98) | 1 (2) | 2.03 (1.29, 3.19) | No specified | |||||||

| Roy 1985 | USA | North America | 1981–1974 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Samkoff 1995 | USA | North America | 1980–1988 | General practitioners, internal medicine, general surgeons, radiology, paediatrics | ||||||||||

| Schlicht 1990 | Australia | Australia, New-Zealand and Pacific | 1950–1986 | 1279 (88) | 174 (12) | 10 | 3 | 1.13 (0.54, 2.07) | 5.01 (1.01, 14.7) | No specified | ||||

| Shang 2011 | Taiwan | Australia, New-Zealand and Pacific | 1990–2006 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Shang 2012 | Taiwan | Asia | 1990–2006 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Simon 1968 | USA | North America | 1947–1967 | No specified | ||||||||||

| Stefansson 1991 | Sweden | Europe | 1971–1985 | 113 (82) | 25 (19) | 1.82 (1.19, 2.80) | 5.02 (1.67, 15.0) | No specified | ||||||

| Torre 2005 | USA | North America | 1948–1998 | 183 (91) | 18 (11) | 20 (90) | 2 (10) | 1.82 (1.11, 2.82) | 4.95 (0.56, 17.9) | No specified | ||||

| Ullmann 1991 | USA | North America | 1910–1981 | 46 | 1.48 (0.97, 2.27) | No specified | ||||||||

| Wang 2017 | China | Asia | 2004–2017 | 6 (33) | 8 (44) | Dermatologists, emergency, internal medicine, obstetricians, paediatrics, cardiology, neurology, urology, ophthalmology, anaesthesiologists | ||||||||

Meta-analysis of the standardized mortality rate for suicides among physicians

We included 25 studies. The overall SMR was 1.44 (95CI 1.16, 1.72) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 93.9%). Among the 25 included studies, 17 studies reported both male and female physicians [7,8,41,46,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,68,70,71,82], six reported only male physicians [60,64,65,66,67,72], and one only reported female physicians [63]. We found a significantly higher risk of suicide among male physicians than in the general population (SMR = 1.24; 95CI 1.05, 1.43; P < 0.001; I2 = 79.1%) and for suicide among female physicians than in the general population (SMR = 1.94; 95CI 1.49, 2.58; P < 0.041; I2 = 42.5%) (Fig 4). Meta-regressions demonstrated that women physicians had a higher risk than their counterpart men to commit suicide (0.67; 95CI 0.19, 1.14; P = 0.007) (Fig 5). We further demonstrated that the risk of suicide was not homogeneous over all the countries. SMR was 1.27 (95CI 1.05, 1.49; P < 0.001; I2 = 71.3%) in Europe, 1.63 (95CI 1.29, 1.96; P < 0.001; I2 = 74.1%) in North America, 0.79 (95CI 0.03, 1.62; P = 0.002; I2 = 79.5%) in Australia, New-Zeeland and Pacific and 1.26 (95CI 0.56, 1.96) in Africa (Fig 6). Meta-regressions demonstrated a higher risk of suicide in North America than in Australia, New-Zeeland and Pacific (0.92; 95CI 0.22, 1.63; P = 0.013) and especially higher in USA vs the rest of the world (1.34; 95CI 1.28, 1.55; P < 0.001) (Fig 5).

Finally, we demonstrated an overall time effect (-0.15; 95CI -0.29, -0.01; P = 0.032) which signify that the risk decreased over time. This relationship is significant in Europe (-0.18; 95CI -0.37, -0.01; P = 0.044) but not in USA (-0.11; 95CI -0.37, 0.15; P = 0.370) or in Australia, New-Zeeland and Pacific (-0.48; 95CI -8.09, 7.12; P = 0.570). For Africa, there were insufficient observations (Fig 5).

Meta-analysis of percentage of suicide in physicians by group of specialties

We included eight studies [15,16,40,43,45,47,51,83]. The percentage of suicide in general practitioners was 32% (95CI 21, 43; P < 0.001; I2 = 93.1%), in internal medicine was 16% (95CI 9, 23; P < 0.001; I2 = 88.6%), in psychiatrists was 11% (95CI 9, 14; P = 0.30; I2 = 17.5%), in other medical specialties was 3% (95CI 3, 4; P = 0.02; I2 = 40.7%), in surgeons was 4% (95CI 2, 5; P < 0.001; I2 = 62.8%) and in internships was 2% (95CI 1, 4) (Fig 7).

Meta-regressions demonstrated a higher risk of suicide in general practitioners than internal medicine (0.12; 95CI 0.05, 0.19; P = 0.001), than psychiatrists (0.17; 95CI 0.09, 0.24; P < 0.001), than other medical specialties (0.24; 95CI 0.18, 0.30; P < 0.001), than surgeons (0.25; 95CI 0.19, 0.30; P < 0.001) and then internships (0.24; 95CI 0.15, 0.34; P < 0.001). Moreover, a higher risk of suicide in internal medicine than in other medical specialties (0.12; 95CI 0.08, 0.17; P < 0.001), than surgeons (0.13; 95CI 0.08, 0.18; P < 0.001), and than internships (0.13; 95CI 0.03, 0.22; P = 0.008). Finally, we demonstrated a higher risk of suicide in psychiatrists than other medical specialties (0.07; 95CI 0.02, 0.13; P = 0.009) and than surgeons (0.08; 95CI 0.02, 0.13; P = 0.005) (S1 Fig).

Meta-analysis of percentages of suicide in physicians by category of surgical specialties

We included six studies [15,16,43,47,51,83]. The percentage of suicide in general surgeons was 6% i.e. (95CI 4, 9; I2 = 64.5%, P = 0.04), in obstetricians was 4% (95CI 2, 5; I2 = 0, P = 0.81), in orthopaedists was 2% (95CI 1, 4), in ears, nose and throat was 3% (95CI 0, 3) and in plastic surgeons was 1% (95CI 0, 6) (Fig 8).

Meta-regressions demonstrated a higher risk of suicide in general surgeons than obstetricians (0.03; 95CI 0.01, 0.05; P = 0.035), than orthopedists (0.04; 95CI 0.01, 0.07; P = 0.006), than ophthalmologists (0.04; 95CI 0.02, 0.07; P = 0.006) and than plastic surgeons (0.05; 95CI 0.01, 0.09; P = 0.010) (S2 Fig).

Meta-analysis of percentages of suicide in physicians by category of medical specialties

Eight studies were included [15,16,40,43,45,47,51,83]. The percentage of suicide in internal medicine was 16% (95CI 9, 23; I2 = 88.6%, P < 0.001), in psychiatrists was 11% (95CI 9, 14; I2 = 17.5%, P = 0.30), in anaesthesiologists was 4% (95CI 2, 6; I2 = 43.6%, P = 0.11), in radiologists was 3% (95CI 2, 5; I2 = 66.0%, P = 0.02), in paediatricians was 4% (95CI 3, 6; I2 = 46.4%, P = 0.11), in pathologists was 2% (95CI 1, 3), in dermatologists was 5% (95CI 1, 9), in cardiologists was 6% (95CI 1, 26), in neurologists was 6% (95CI 1, 26) and in emergency physicians was 6% (95CI 1, 26) (Fig 9). Meta-regressions demonstrated a higher risk of suicide in internal medicine than anesthesiologists (0.12; 95CI 0.06, 0.18; P = 0.001) than radiologists (0.13; 95CI 0.07, 0.19; P < 0.001), than pediatricians (0.12; 95CI 0.06, 0.18; P = 0.001) than pathologists (0.14; 95CI 0.07, 0.21; P < 0.001) and than dermatologists (0.12; 95CI 0.03, 0.21; P = 0.13). Moreover, the risk of suicide was higher in psychiatrists than anesthesiologists (0.07; 95CI 0.01, 0.13; P = 0.038), than radiologists (0.08; 95CI 0.02, 0.14; P = 0.014), than pediatricians (0.07; 95CI 0.01, 0.13; P = 0.038) and than pathologists (0.09; 95CI 0.02, 0.17; P = 0.014) (S3 Fig).

Meta-analysis of prevalence of physicians dead by suicide among all deaths in physicians

We included 12 studies [16,39,41,42,44,46,48,49,50,51,52,53], and we demonstrated a prevalence of 4% (95CI 3, 5) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 88.7%) (Fig 10).

Meta-regression on geographic zones did not retrieves any significant result. Moreover, insufficient data did not permit other meta-regression.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of deaths by suicide in physicians among all deaths by suicide in the general population

We included nine studies [1,5,15,34,35,36,37,38,82], and we demonstrated a prevalence of 1% (95CI 1, 1) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 98.0%) (S4 Fig). Insufficient data did not permit meta-regression.

Meta-analysis of the number of physicians having done suicide attempt among all the physicians

We included five studies [47,57,75,77,85]. The overall effect size was 0.01 (95CI 0.01, 0.02; p < 0.01) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 82.6%) (S5 Fig). Insufficient data did not permit meta-regression.

Meta-analysis of the number of physicians with suicidal ideation among all the physicians

We included seven studies [74,75,76,77,78,84,85]. The overall effect size was 0.17 (95CI 0.12, 0.21; p < 0.001) with an important heterogeneity (I2 = 98.8%) (Fig 11). Insufficient data did not permit meta-regression.

Other health care workers

As there are few exploitable studies about dental surgeons, nurses and other health-care workers, we didn’t treat them in that meta-analysis.

Discussion

Physicians were an at-risk profession (1.44, 95CI 1.16, 1.72), particularly women-physician (0.67, 95CI 0.19, 1.14; p = 0.007). Some countries had a high risk of suicide (USA vs Rest of the world: 1.34, 95CI 1.28, 1.55; p < 0.001) and rate of suicide in physicians decreased over time, especially in Europe (-0.18, 95CI -0.37, -0.01; p = 0.044). Some specialties were higher risk such as anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners and general surgeons. The prevalence of physicians having done suicide attempt among all the physicians were significant (0.01, 95CI 0.01, 0.02; p < 0.001) as the prevalence of physicians with suicidal ideation among all the physicians (0.17, 95CI 0.12, 0.21; p < 0.001). Finally, there were not enough exploitable data about dental surgeons, nurses and other health-care workers which are however some at-risk professions.

An at-risk profession

The high risk of suicide in physicians might be explained by several putative factors such as psychosocial working environment [18], or specific personality traits of physicians. Psychosocial work environment has been shown in the literature as an important risk factor, doctors being confronted to conflicts with colleagues, lack of cohesive teamwork and social support, leading them individually [88]. Physicians must also routinely face with breaking bad news [89], and are in frequent contact with illness, anxiety, suffering and death. Perfectionism, compulsive attention to detail, exaggerated sense of duty, excessive sense of responsibility, desire to please everyone are appreciates qualities in workplace [90,91] but increased stress and depression [92] and imprison physicians in vicious circle without seek help. They also prevent themselves to ask for help because of the culture of medical education [90,91]. In particular, we demonstrated that women physicians were particularly exposed to suicide, which might be explained by the additional strain imposed on them because of their social roles [11]. In most countries, women still have more at-home responsibilities (education of children, nursing, household care, etc) than men. Combining a full-time job as a physician and those at-home responsibilities might be particularly difficult to manage [11]. Although income gender-inequalities have not been reported in physicians[93,94], some authors suggested that the medical field was mainly dominated by the male gender and reported a poor status integration of women physicians within the profession [7]. It has been shown that female physicians/internships react by imposing themselves an additional pressure to demonstrate their male counterparts that they are as strong, self-sufficient and worthy as them [95].

Depending on countries

We showed that the risk of suicide was not homogeneous between countries, in line with inequality of job satisfaction among physicians in many countries [96,97]. Indeed, some countries such as Switzerland and Canada reported a high level of job satisfaction for physicians (>75%) [98,99]. In the United States, most obstetrician gynecologists only rated their job satisfaction as moderate [100]. Physician job satisfaction is essential for ensuring the quality and sustainability of health care provision [101,102]. Moreover, career dissatisfaction was associated with burnout and prolonged fatigue among physicians [103]. In most countries, physicians’ work conditions underwent frequent mutations, with multiple healthcare reforms initiatives promoting by local governments. Reforms are a necessary compromise between best outcomes on deliveries of care, health economics, and quality of work environment [104,105].

With a time effect

There are few data on the evolution of the rate of suicide over time and we were the first to demonstrate that, in some countries such as in Europe the suicide rate among physicians decreased significantly with time but not in the USA. During the past decade, a confluence of forces has changed the practice of medicine in unprecedented ways. Indeed, physicians have seen their autonomy reduced by increased administrative tasks and time pressure [106,107,108]. In USA, a survey showed that physicians’ satisfaction declined over the last 10 years, with less time spent per patient and for private life [13]. US physicians might also be particularly stress [109] because of medical errors that are the third leading cause of death in US [110,111] in a context of economic pressure and relationships with pharmaceutic companies [112,113], religious beliefs [114], access care difficulties for some patients [115], and legal procedure intended against physicians [116] leading them to practice a more defensive medicine [117] misleading patients in overdiagnosis [118]. The World Health Organization global strategy on human resources for health (workforce 2030) promoted the personal and professional rights of health-care workers, including safe and decent working environments [119]. Particularly in Europe, working hours of physicians decreased significantly over the last decades following official instructions such as the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) [14], which may have contributed to a decreased risk of suicides.

Some specialties are more at-risk

We showed some the most at-risk specialties were anaesthesiologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners and general surgeons. The high risk of suicides in anaesthesiologists [16,41,48,76] could be explained by an easy access to potentially lethal drugs, a high prevalence of burnout [120], a high workload with fear of harming patients and organizational burden with poor autonomy, and conflicts with colleagues [121]. For psychiatrists, the high risk of suicides has been linked by stressful and traumatic experiences such as, paradoxically, dealing with suicides of patient [16]. Next to those medical specialties, the general practitioners were an historical at-risk occupation, with moral loneliness, job interfering with family life, constant interruptions both at home and at work, increasing administrative constraints, and high levels of patients' expectations, leading to a low job satisfaction and poor mental health [122,123]. Finally, specialties with life-and-death emergencies, like surgery, are particularly stressful [124,125,126,127]. For example, it has been shown that intra-operative death increased morbidity in patients operated by the same surgeon in the subsequent 48 hours, with a more pronounced whether the death occurring during emergency surgery [128].

Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation

Suicide could be regarded as a lengthy process. Little is known about causes and transitions between suicidal ideation / attempted suicide and suicide, as well as about the factors that precipitate or protect against these transitions [129]. Because physicians might be more aware of these characteristics than the general population [75], having suicidal thoughts should be taken particularly seriously in this profession. Suicidal ideation are considered a sensitive and specific indicator of suicide risk [130,131]. Preventive strategies may include improved management of psychiatric disorders, the recognition and treatment of depression and substances abuse [65], but also measures to reduce occupational stress, and restriction of access to means of suicide when doctors are depressed [4,132]. Medical school curriculum should also include programs to increase students’ self-confidence, to express their emotional needs, and to teach that anyone may be suicidal–regardless of his status [133]. The preventive approach may consist of screening, assessment, referral and education, and to destigmatize help-seeking at-risk medical students/physicians [134].

Suicides in other health-care workers

We highlighted the lack of studies providing data on deaths by suicide and on suicidal risks in nurses and in other health-care workers. However, nurses remained at high-risk of suicide with various stressful factors comparable to those previously described for physicians, such as patients cares, team’s conflicts, heavy workload, lack of autonomy, and work-family conflicts [135,136]. As for physicians, some occupational settings were described as particularly stressful, such as working in emergency departments [137], with a high prevalence of shift work [138], exposure to aggressive and violent behavior from patients [139] and from situation relating to trauma, alcohol and intoxications [140]. Our study demonstrated the lack of data on other health-care workers such as pharmacists, dental surgeons, midwives, caregivers and hospital maids. We believe that such data are needed.

Limitations

Our study has however some limitations. Meta-analyses inherit the limitations of the individual studies of which they are composed: varying quality of studies and multiple variations in study protocols and evaluation. We highlighted that general practitioners were prone to suicide. However, comparisons between specialties may suffer from a major bias such as different number of physicians within each specialty (not the same denominator in statistical analyses—there are more suicides among general practitioners because there are more general practitioners than other individual specialties). All included studies on death by suicide in physicians were retrospective and based on health registers, and thus few studies reported details on occupation such as seniority or characteristics of practice, precluding further analyses necessary for effective preventive strategies. The studies on suicide attempts and suicidal ideation that were based on self-report questionnaire [73,74,75,77] may lack of standardized interviews or specifics criteria for diagnoses psychiatric disorders [125,[141]. Most cross-sectional studies included in our meta-analyses described a bias of self-report such as skipping questions and incomplete information, nondisclosure, and uncertainty regarding timing of questionnaire. Percentage of respondents within those studies may seem low, from 45% [74] to 76% [77], however the response rate was higher than usual [142,143,144,145,146]. The language used in countries with two official languages may also have influenced responses [74]. Only one study questioned physicians on their antidepressant treatment [121], and only one study questioned about a psychiatric disorder [74]. More data is needed regarding physician’s health. Finally, none of the studies included specified whether some physicians were retired or not.

Conclusion

Preventive strategies on the risk of suicides in physicians are strongly needed. Physicians are an at-risk profession of suicide, with a global SMR of 1.44 (95CI 1.16, 1.72), and an important heterogeneity between studies. Women were particularly at risk compared to male physicians. In addition, some countries were with a higher risk of suicide such as USA. Interestingly, the rate of suicide in physicians decreased over time, especially in Europe, suggesting improvements of working conditions of physicians. Some specialties might be at higher risk such as anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners and general surgeons. The high prevalence of physicians who committed suicide attempts as well as those with suicidal ideation should benefits for preventive strategies at the workplace. Public health policies must aim at improving social work environment and contribute to screening, assessment, referral, and destigmatization of suicides in physicians. Finally, the lack of data on other health-care workers suggest implementing studies investigating those occupations who might also be at risk of suicide.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Richard May for providing assistance in improving the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, Platt B, Mellanby RJ (2011) Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population-based registers. J Affect Disord 134: 320–326. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawton K, Simkin S, Rue J, Haw C, Barbour F, Clements A, et al. (2002) Suicide in female nurses in England and Wales. Psychol Med 32: 239–250. 10.1017/s0033291701005165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz RM (1983) Causes of death among registered nurses. J Occup Med 25: 760–762. 10.1097/00043764-198310000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M (2007) Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med 37: 1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hem E, Haldorsen T, Aasland OG, Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O (2005) Suicide rates according to education with a particular focus on physicians in Norway 1960–2000. Psychol Med 35: 873–880. 10.1017/s0033291704003344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA (2004) Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry 161: 2295–2302. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ (2001) Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979–1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 55: 296–300. 10.1136/jech.55.5.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindeman S, Laara E, Hirvonen J, Lonnqvist J (1997) Suicide mortality among medical doctors in Finland: are females more prone to suicide than their male colleagues? Psychol Med 27: 1219–1222. 10.1017/s0033291796004680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmann S (2018) Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, Lonnqvist J (1996) A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry 168: 274–279. 10.1192/bjp.168.3.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Notman MT, Nadelson CC (1973) Medicine: a career conflict for women. Am J Psychiatry 130: 1123–1127. 10.1176/ajp.130.10.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertolote JM, De Leo D (2012) Global suicide mortality rates—a light at the end of the tunnel? Crisis 33: 249–253. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray A, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Rogers WH, Inui T, Safran DG (2001) Doctor discontent. A comparison of physician satisfaction in different delivery system settings, 1986 and 1997. J Gen Intern Med 16: 452–459. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007452.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temple J (2014) Resident duty hours around the globe: where are we now? BMC Medical Education 14: S8 10.1186/1472-6920-14-S1-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hikiji W, Fukunaga T (2014) Suicide of physicians in the special wards of Tokyo Metropolitan area. J Forensic Leg Med 22: 37–40. 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich CL, Pitts FN Jr. (1980) Suicide by psychiatrists: a study of medical specialists among 18,730 consecutive physician deaths during a five-year period, 1967–72. J Clin Psychiatry 41: 261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts SE, Jaremin B, Lloyd K (2013) High-risk occupations for suicide. Psychol Med 43: 1231–1240. 10.1017/S0033291712002024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson PD, Weaver MD, Frank RC, Warner CW, Martin-Gill C, Guyette FX, et al. (2012) Association between poor sleep, fatigue, and safety outcomes in emergency medical services providers. Prehosp Emerg Care 16: 86–97. 10.3109/10903127.2011.616261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawton K, Clements A, Simkin S, Malmberg A (2000) Doctors who kill themselves: a study of the methods used for suicide. QJM 93: 351–357. 10.1093/qjmed/93.6.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(2012).

- 21.Puthran R, Zhang MW, Tam WW, Ho RC (2016) Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Med Educ 50: 456–468. 10.1111/medu.12962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. (2016) Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Jama 316: 2214–2236. 10.1001/jama.2016.17324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witt K, Boland A, Lamblin M, McGorry PD, Veness B, Cipriani A, et al. (2019) Effectiveness of universal programmes for the prevention of suicidal ideation, behaviour and mental ill health in medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health 22: 84–90. 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng W, Chen R, Wang X, Zhang Q, Deng W (2019) Prevalence of mental health problems among medical students in China: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98: e15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Costa BR, Cevallos M, Altman DG, Rutjes AW, Egger M (2011) Uses and misuses of the STROBE statement: bibliographic study. BMJ Open 1: e000048 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. (2007) Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 147: W163–194. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. (2017) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benoist d'Azy C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Chiambaretta F, Dutheil F (2016) Antibioprophylaxis in Prevention of Endophthalmitis in Intravitreal Injection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11: e0156431 10.1371/journal.pone.0156431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courtin R, Pereira B, Naughton G, Chamoux A, Chiambaretta F, Lanhers C, et al. (2016) Prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6: e009675 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ollier M, Chamoux A, Naughton G, Pereira B, Dutheil F (2014) Chest CT scan screening for lung cancer in asbestos occupational exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 145: 1339–1346. 10.1378/chest.13-2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F (2017) Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 47: 163–173. 10.1007/s40279-016-0571-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7: 177–188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Citrome L, Magnusson K (2014) Paging Dr Cohen, Paging Dr Cohen … An effect size interpretation is required STAT!: visualising effect size and an interview with Kristoffer Magnusson. Int J Clin Pract 68: 533–534. 10.1111/ijcp.12435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aasland OG, Ekeberg O, Schweder T (2001) Suicide rates from 1960 to 1989 in Norwegian physicians compared with other educational groups. Soc Sci Med 52: 259–265. 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00226-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aasland OG, Hem E, Haldorsen T, Ekeberg O (2011) Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960–2000. BMC Public Health 11: 173 10.1186/1471-2458-11-173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL (2013) Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35: 45–49. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubbard SD (1922) Suicide Among Physicians. Am J Public Health (N Y) 12: 857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindeman S, Heinanen H, Väisänen E, Lönnqvist J (2007) Suicide among medical doctors: Psychological autopsy data on seven cases. Archives of Suicide Research 4: 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 39.(1986) Physician Mortality and Suicide. Results and Implication of the AMA-APA Pilot Study. Connecticut Medicine 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Austin AE, van den Heuvel C, Byard RW (2013) Physician suicide. J Forensic Sci 58 Suppl 1: S91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carpenter LM, Swerdlow AJ, Fear NT (1997) Mortality of doctors in different specialties: findings from a cohort of 20000 NHS hospital consultants. Occup Environ Med 54: 388–395. 10.1136/oem.54.6.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig AG, Pitts FN Jr. (1968) Suicide by physicians. Dis Nerv Syst 29: 763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeSole DE, Singer P, Aronson S (1969) Suicide and role strain among physicians. Int J Soc Psychiatry 15: 294–301. 10.1177/002076406901500407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Everson RB, Fraumeni JF Jr. (1975) Mortality among medical students and young physicians. J Med Educ 50: 809–811. 10.1097/00001888-197508000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gagne P, Moamai J, Bourget D (2011) Psychopathology and Suicide among Quebec Physicians: A Nested Case Control Study. Depress Res Treat 2011: 936327 10.1155/2011/936327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Innos K, Rahu K, Baburin A, Rahu M (2002) Cancer incidence and cause-specific mortality in male and female physicians: a cohort study in Estonia. Scand J Public Health 30: 133–140. 10.1080/14034940210133735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones RE (1977) A study of 100 physician psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 134: 1119–1123. 10.1176/ajp.134.10.1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lew EA (1979) Mortality experience among anesthesiologists, 1954–1976. Anesthesiology 51: 195–199. 10.1097/00000542-197909000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linde HW, Mesnick PS, Smith NJ (1981) Causes of death among anesthesiologists: 1930–1946. Anesth Analg 60: 1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palhares-Alves HN, Palhares DM, Laranjeira R, Nogueira-Martins LA, Sanchez ZM (2015) Suicide among physicians in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, across one decade. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 37: 146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Samkoff JS, Hockenberry S, Simon LJ, Jones RL (1995) Mortality of young physicians in the United States, 1980–1988. Acad Med 70: 242–244. 10.1097/00001888-199503000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlicht SM, Gordon IR, Ball JR, Christie DG (1990) Suicide and related deaths in Victorian doctors. Med J Aust 153: 518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shang TF, Chen PC, Wang JD (2012) Disparities in mortality among doctors in Taiwan: a 17-year follow-up study of 37 545 doctors. BMJ Open 2: e000382 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnetz BB, Horte LG, Hedberg A, Theorell T, Allander E, Malker H (1987) Suicide patterns among physicians related to other academics as well as to the general population. Results from a national long-term prospective study and a retrospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 75: 139–143. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bamayr A, Feuerlein W (1986) [Incidence of suicide in physicians and dentists in Upper Bavaria]. Soc Psychiatry 21: 39–48. 10.1007/bf00585321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dean G (1969) The causes of death of South African doctors and dentists. S Afr Med J 43: 495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frank E, Biola H, Burnett CA (2000) Mortality rates and causes among U.S. physicians. Am J Prev Med 19: 155–159. 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herner B (1993) [High frequency of suicide among younger physicians. Unsatisfactory working situations should be dealt with]. Lakartidningen 90: 3449–3452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Juel K, Mosbech J, Hansen ES (1999) Mortality and causes of death among Danish medical doctors 1973–1992. Int J Epidemiol 28: 456–460. 10.1093/ije/28.3.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindhardt Marie EF, Hamtoft Henry and Mosbech Johannes (1963) Causes of death among the menidal profession in Denmark. Danish Medical Bulletin 10. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nordentoft M (1988) [Suicide among physicians]. Ugeskr Laeger 150: 2440–2443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petersen MR, Burnett CA (2008) The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med (Lond) 58: 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pitts FN Jr., Schuller AB, Rich CL, Pitts AF (1979) Suicide among U.S. women physicians, 1967–1972. Am J Psychiatry 136: 694–696. 10.1176/ajp.136.5.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rafnsson G (1998) Causes of death and cancer among doctors and lawyers in Iceland. Nordisk Medicin 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Revicki DA, May HJ (1985) Physician suicide in North Carolina. South Med J 78: 1205–1207. 10.1097/00007611-198510000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rich CL, Pitts FN Jr., (1979) Suicide by male physicians during a five-year period. Am J Psychiatry 136: 1089–1090. 10.1176/ajp.136.8.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rimpela AH, Nurminen MM, Pulkkinen PO, Rimpela MK, Valkonen T (1987) Mortality of doctors: do doctors benefit from their medical knowledge? Lancet 1: 84–86. 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rose KD, Rosow I (1973) Physicians who kill themselves. Arch Gen Psychiatry 29: 800–805. 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200060072011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shang TF, Chen PC, Wang JD (2011) Mortality of doctors in Taiwan. Occup Med (Lond) 61: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stefansson CG, Wicks S (1991) Health care occupations and suicide in Sweden 1961–1985. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 26: 259–264. 10.1007/bf00789217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Torre DM, Wang NY, Meoni LA, Young JH, Klag MJ, Ford DE (2005) Suicide compared to other causes of mortality in physicians. Suicide Life Threat Behav 35: 146–153. 10.1521/suli.35.2.146.62878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ullmann D, Phillips RL, Beeson WL, Dewey HG, Brin BN, Kuzma JW, et al. (1991) Cause-specific mortality among physicians with differing life-styles. JAMA 265: 2352–2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frank E, Dingle AD (1999) Self-reported depression and suicide attempts among U.S. women physicians. Am J Psychiatry 156: 1887–1894. 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fridner A, Belkic K, Marini M, Minucci D, Pavan L, Schenck-Gustafsson K (2009) Survey on recent suicidal ideation among female university hospital physicians in Sweden and Italy (the HOUPE study): cross-sectional associations with work stressors. Gend Med 6: 314–328. 10.1016/j.genm.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hem E, GrLnvold NT, Aasland OG, Ekeberg O (2000) The prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among Norwegian physicians. Results from a cross-sectional survey of a nationwide sample. Eur Psychiatry 15: 183–189. 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00227-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lindfors PM, Meretoja OA, Luukkonen RA, Elovainio MJ, Leino TJ (2009) Suicidality among Finnish anaesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53: 1027–1035. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Olkinuora M, Asp S, Juntunen J, Kauttu K, Strid L, Aarimaa M (1990) Stress symptoms, burnout and suicidal thoughts in Finnish physicians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 25: 81–86. 10.1007/bf00794986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simon W, Lumry GK (1968) Suicide among physician-patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 147: 105–112. 10.1097/00005053-196808000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gunnarsdottir H, Rafnsson V (1995) Mortality among Icelandic nurses. Scand J Work Environ Health 21: 24–29. 10.5271/sjweh.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hemenway D, Solnick SJ, Colditz GA (1993) Smoking and suicide among nurses. Am J Public Health 83: 249–251. 10.2105/ajph.83.2.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roy A (1985) Suicide in doctors. Psychiatr Clin North Am 8: 377–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davidson JE, Stuck AR, Zisook S, Proudfoot J (2018) Testing a Strategy to Identify Incidence of Nurse Suicide in the United States. J Nurs Adm 48: 259–265. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Y, Liu L, Xu H (2017) Alarm bells ring: suicide among Chinese physicians: A STROBE compliant study. Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brooks E, Gendel MH, Early SR, Gundersen DC (2017) When Doctors Struggle: Current Stressors and Evaluation Recommendations for Physicians Contemplating Suicide. Arch Suicide Res 22: 519–528. 10.1080/13811118.2017.1372827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loas G, Lefebvre G, Rotsaert M, Englert Y (2018) Relationships between anhedonia, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a large sample of physicians. PLoS One 13: e0193619 10.1371/journal.pone.0193619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zeng HJ, Zhou GY, Yan HH, Yang XH, Jin HM (2018) Chinese nurses are at high risk for suicide: A review of nurses suicide in China 2007–2016. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 32: 896–900. 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Suzanne MP (1999) U. S. psychologists' suicide rates have declined since the 1960s. Archives of Suicide Research: 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Firth-Cozens J (2000) New stressors, new remedies. Occup Med (Lond) 50: 199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schildmann J, Cushing A, Doyal L, Vollmann J (2005) Breaking bad news: experiences, views and difficulties of pre-registration house officers. Palliat Med 19: 93–98. 10.1191/0269216305pm996oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bressler B (1976) Suicide and drug abuse in the medical community. Suicide Life Threat Behav 6: 169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carr GD (2008) Physician suicide—a problem for our time. J Miss State Med Assoc 49: 308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McManus IC, Keeling A, Paice E (2004) Stress, burnout and doctors' attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: a twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Med 2: 29 10.1186/1741-7015-2-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smith SJ (1990) Income, Housing Wealth and Gender Inequality. Urban Studies 27: 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Finch N (2014) Why are women more likely than men to extend paid work? The impact of work-family life history. Eur J Ageing 11: 31–39. 10.1007/s10433-013-0290-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pospos S, Tal I, Iglewicz A, Newton IG, Tai-Seale M, Downs N, et al. (2019) Gender differences among medical students, house staff, and faculty physicians at high risk for suicide: A HEAR report. Depress Anxiety. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Janus K, Amelung VE, Gaitanides M, Schwartz FW (2007) German physicians "on strike"—shedding light on the roots of physician dissatisfaction. Health Policy 82: 357–365. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, Blumenthal D (2006) Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care 44: 234–242. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199848.17133.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bovier PA, Perneger TV (2003) Predictors of work satisfaction among physicians. Eur J Public Health 13: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jenkins K, Wong D (2001) A survey of professional satisfaction among Canadian anesthesiologists. Can J Anaesth 48: 637–645. 10.1007/BF03016196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bell DJ, Bringman J, Bush A, Phillips OP (2006) Job satisfaction among obstetrician-gynecologists: a comparison between private practice physicians and academic physicians. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 1474–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H (2003) National survey of job satisfaction and retirement intentions among general practitioners in England. BMJ 326: 22 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Leigh JP, Kravitz RL, Schembri M, Samuels SJ, Mobley S (2002) Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Arch Intern Med 162: 1577–1584. 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wada K, Arimatsu M, Yoshikawa T, Oda S, Taniguchi H, Higashi T, et al. (2008) Factors on working conditions and prolonged fatigue among physicians in Japan. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82: 59–66. 10.1007/s00420-008-0307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khim K (2016) Are health workers motivated by income? Job motivation of Cambodian primary health workers implementing performance-based financing. Glob Health Action 9: 31068 10.3402/gha.v9.31068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hung LM, Shi L, Wang H, Nie X, Meng Q (2013) Chinese primary care providers and motivating factors on performance. Fam Pract 30: 576–586. 10.1093/fampra/cmt026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kassirer JP (1998) Doctor discontent. N Engl J Med 339: 1543–1545. 10.1056/NEJM199811193392109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, McMurray JE, Pathman DE, Williams ES, et al. (2000) Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med 15: 441–450. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05239.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, et al. (1999) Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and a challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care 37: 1174–1182. 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leape LL (1994) Error in medicine. Jama 272: 1851–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Makary MA, Daniel M (2016) Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. Bmj 353: i2139 10.1136/bmj.i2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Anderson JG, Abrahamson K (2017) Your Health Care May Kill You: Medical Errors. Stud Health Technol Inform 234: 13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mitchell AP, Winn AN, Lund JL, Dusetzina SB (2019) Evaluating the Strength of the Association Between Industry Payments and Prescribing Practices in Oncology. Oncologist 24: 632–639. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wazana A (2000) Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? Jama 283: 373–380. 10.1001/jama.283.3.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Korup AK, Sondergaard J, Lucchetti G, Ramakrishnan P, Baumann K, Lee E, et al. (2019) Religious values of physicians affect their clinical practice: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 7 countries. Medicine (Baltimore) 98: e17265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dickman SL, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S (2017) Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet 389: 1431–1441. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Berlin L (2017) Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad. Diagnosis (Berl) 4: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, et al. (2005) Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. Jama 293: 2609–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chiolero A, Paccaud F, Aujesky D, Santschi V, Rodondi N (2015) How to prevent overdiagnosis. Swiss Med Wkly 145: w14060 10.4414/smw.2015.14060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.(2006) World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kuhn CM, Flanagan EM (2017) Self-care as a professional imperative: physician burnout, depression, and suicide. Can J Anaesth 64: 158–168. 10.1007/s12630-016-0781-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lindfors PM, Nurmi KE, Meretoja OA, Luukkonen RA, Viljanen AM, Leino TJ, et al. (2006) On-call stress among Finnish anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 61: 856–866. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rosado-Bartolome A (2014) [The moral loneliness of the General Practitioner]. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 214: 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cooper CL, Rout U, Faragher B (1989) Mental health, job satisfaction, and job stress among general practitioners. BMJ 298: 366–370. 10.1136/bmj.298.6670.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dutheil F, Boudet G, Perrier C, Lac G, Ouchchane L, Chamoux A, et al. (2012) JOBSTRESS study: comparison of heart rate variability in emergency physicians working a 24-hour shift or a 14-hour night shift—a randomized trial. Int J Cardiol 158: 322–325. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dutheil F, Marhar F, Boudet G, Perrier C, Naughton G, Chamoux A, et al. (2017) Maximal tachycardia and high cardiac strain during night shifts of emergency physicians. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dutheil F, Trousselard M, Perrier C, Lac G, Chamoux A, Duclos M, et al. (2013) Urinary Interleukin-8 Is a Biomarker of Stress in Emergency Physicians, Especially with Advancing Age—The JOBSTRESS* Randomized Trial. PLoS One 8: e71658 10.1371/journal.pone.0071658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hufnagel C, Chambres P, Bertrand PR, Dutheil F (2017) The Need for Objective Measures of Stress in Autism. Frontiers in Psychology 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Goldstone AR, Callaghan CJ, Mackay J, Charman S, Nashef SA (2004) Should surgeons take a break after an intraoperative death? Attitude survey and outcome evaluation. BMJ 328: 379 10.1136/bmj.37985.371343.EE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Diekstra RF, Garnefski N (1995) On the nature, magnitude, and causality of suicidal behaviors: an international perspective. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25: 36–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Galfalvy HC, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ (2008) Evaluation of clinical prognostic models for suicide attempts after a major depressive episode. Acta Psychiatr Scand 117: 244–252. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01162.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gyorffy Z, Adam S, Csoboth C, Kopp M (2005) [The prevalence of suicide ideas and their psychosocial backgrounds among physicians]. Psychiatr Hung 20: 370–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hawton K, Malmberg A, Simkin S (2004) Suicide in doctors. A psychological autopsy study. J Psychosom Res 57: 1–4. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00372-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Preven DW (1981) Physician suicide. Hillside J Clin Psychiatry 3: 61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Moutier C, Norcross W, Jong P, Norman M, Kirby B, McGuire T, et al. (2012) The suicide prevention and depression awareness program at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. Acad Med 87: 320–326. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824451ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Alderson M, Parent-Rocheleau X, Mishara B (2015) Critical Review on Suicide Among Nurses. Crisis: 1–11. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hawton K, Vislisel L (1999) Suicide in nurses. Suicide Life Threat Behav 29: 86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Healy S, Tyrrell M (2011) Stress in emergency departments: experiences of nurses and doctors. Emerg Nurse 19: 31–37. 10.7748/en2011.07.19.4.31.c8611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shao MF, Chou YC, Yeh MY, Tzeng WC (2010) Sleep quality and quality of life in female shift-working nurses. J Adv Nurs 66: 1565–1572. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chapman R, Styles I (2006) An epidemic of abuse and violence: nurse on the front line. Accid Emerg Nurs 14: 245–249. 10.1016/j.aaen.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Patton R, Smythe W, Kelsall H, Selemo FB (2007) Substance use among patients attending an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J 24: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hopwood CJ, Morey LC, Edelen MO, Shea MT, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, et al. (2008) A comparison of interview and self-report methods for the assessment of borderline personality disorder criteria. Psychol Assess 20: 81–85. 10.1037/1040-3590.20.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Trousselard M, Dutheil F, Naughton G, Cosserant S, Amadon S, Duale C, et al. (2016) Stress among nurses working in emergency, anesthesiology and intensive care units depends on qualification: a Job Demand-Control survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 89: 221–229. 10.1007/s00420-015-1065-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Dutheil F, Delaire P, Boudet G, Rouffiac K, Djeriri K, Souweine B, et al. (2008) [Cost/effectiveness comparison of the vaccine campaign and reduction of sick leave, after vaccination against influenza among the Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital staff]. Med Mal Infect 38: 567–573. 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Dutheil F, Kelly C, Biat I, Provost D, Baud O, Laurichesse H, et al. (2008) [Relation between the level of knowledge and the rate of vaccination against the flu virus among the staff of the Clermont-Ferrand University hospital]. Med Mal Infect 38: 586–594. 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kelly C, Dutheil F, Haniez P, Boudet G, Rouffiac K, Traore O, et al. (2008) [Analysis of motivations for antiflu vaccination of the Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital staff]. Med Mal Infect 38: 574–585. 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Lopez V, Chamoux A, Tempier M, Thiel H, Ughetto S, Trousselard M, et al. (2013) The long-term effects of occupational exposure to vinyl chloride monomer on microcirculation: a cross-sectional study 15 years after retirement. BMJ Open 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]