Abstract

Introduction

We present a case of an Asian variant of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma associated with systemic and central nervous system hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) with multiple neurologic manifestations.

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old, previously healthy, Korean woman presented with a 4-week history of fever and weight loss. She had pancytopenia with neutropenia, a ferritin level of 5030 μg/L, and elevated liver enzyme levels. Bone marrow, liver biopsy specimens, and cerebrospinal fluid demonstrated hemophagocytosis. The patient was treated with the HLH-2004 protocol, but her disease relapsed 3 months later. A repeated liver biopsy specimen confirmed the initially missed diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, a known driver of HLH in patients of Asian origin. She was then treated with lymphoma-directed therapy and had a prompt resolution of fever and neurologic symptoms as well as normalization of her blood cell counts and ferritin level.

Discussion

This case serves as a reminder that patients with an Asian variant of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma frequently present with HLH and neurologic manifestations, including seizures, strokes, and cognitive deficits. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis and initiation of lymphoma-directed therapy.

Keywords: central nervous system (CNS), hematology, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL), histiocytes, lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare entity that is typically seen in the Asian variant of the condition.1 When present in adults, HLH is most commonly caused by underlying infection, autoimmune disease, or malignancy. Malignancy-associated HLH represents up to one-fourth of secondary HLH cases. Among these, the most common are hematologic malignancies, especially T-cell/natural killer-cell lymphoma or leukemia. In the Asian variant of IVLBCL, about 25% of patients can present with a broad range of neurologic symptoms, including seizures, strokes, and cognitive deficits that can serve as important clues toward the diagnosis.2 IVLBCL can prove to be a diagnostic challenge for clinicians and pathologists if the presentation is subtle or nonspecific, but it should be considered when a secondary cause of HLH is not detected.

CASE PRESENTATION

Presenting Concerns

A 68-year-old Korean woman came to the Emergency Department in April 2018 with a 4-week history of recurrent fever, weight loss, and generalized weakness. She had been previously healthy until she experienced a viral illness in the winter, after which she noticed that her appetite and weight had decreased. She lost approximately 10 kg during a 2-month period. Her family noted that she had become confused and forgetful. Her temperature was peaking at 39°C on a nightly basis. She had no medical problems before this illness. She had no history of travel before this presentation and no contact with sick individuals.

On physical examination, her temperature was 39.3°C, pulse was 95/min, blood pressure was 105/67 mmHg, respiratory rate was 15/min, and oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Her liver was palpable below the right costal margin.

A complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell count of 1300/μL, hemoglobin level of 9.5 g/dL, and platelet count of 86,000/μL. Her liver enzyme levels were mildly elevated, with an alanine aminotransferase value of 75 IU/L and aspartate aminotransferase value of 67 IU/L. Results from her basic metabolic panel were normal. Her international normalized ratio was 1.7. The ferritin level was 5030 μg/L, and the lactate dehydrogenase level was 1699 IU/L. Results of computed tomography scans with contrast enhancement of the abdomen and pelvis showed mild hepatomegaly, with no other abnormalities and with a normal-appearing spleen. Hepatitis B surface antigen, core antibody, surface antibody, and hepatitis C antibody results were negative. Results of viral studies, including Epstein-Barr virus polymerase chain reaction and cytomegalovirus polymerase chain reaction, were negative. Fungal studies, including β-D-glucan and Aspergillus antigen testing, yielded negative results. Blood cultures were obtained, and empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated. Results of blood and urine cultures remained negative.

Therapeutic Intervention and Treatment

Because of the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was performed. The bone marrow was hypercellular with normal trilineage hematopoiesis and markedly increased histiocytes, which included hemophagocytic histiocytes. A liver biopsy specimen was obtained and demonstrated sinusoidal histiocytic inflammation with no malignancy. The overall picture of fever, pancytopenia, elevated ferritin level, and presence of hemophagocytosis in both the bone marrow and liver specimens was diagnostic of HLH. Although no clear infectious, autoimmune, or malignant cause was identified, given the patient’s age, our suspicion for an underlying malignant process remained high.

The patient was started on the HLH-2004 treatment protocol that included etoposide and dexamethasone upfront, with the omission of cyclosporine. On day 5 after initiation of chemotherapy, the patient had 2 generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Results of brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed new scattered diffusion restriction and T2 hyperintensity of the right hemisphere as well as the medial left occipital lobe and pons, without any contrast enhancement (Figure 1). A cerebrospinal fluid sample obtained to rule out infection revealed an increased number of histiocytes/macrophages, many showing hemophagocytosis (Figure 2). These findings in the cerebrospinal fluid suggested a diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) involvement of HLH. Treatment with intrathecal methotrexate and hydrocortisone was initiated and given weekly for 4 doses.

Figure 1.

Axial cut of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence of the brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates T2 hyperintensity (arrow) in the left occipital region.

Figure 2.

Cerebrospinal fluid demonstrates hemophagocytosis with red blood cells present in the cytoplasm of a macrophage.

On day 30, the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility but required readmission to the hospital 1 week later because of aphasia and altered mental status. Results of magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated embolic-appearing infarcts in the left middle cerebral artery territory. Her strokes were attributed to possible paradoxical emboli in the setting of hypercoagulability caused by immobility (Figure 3), but this suspicion could not be confirmed. She was started on anticoagulation therapy with apixaban. She completed HLH-directed therapy in July 2018. During treatment, her fevers subsided, blood cell counts recovered, and ferritin levels normalized.

Figure 3.

Axial cut of the diffusion-weighted sequence of the brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates multifocal embolic-appearing infarcts (arrow) in the left middle cerebral artery distribution.

In October 2018, she was hospitalized again, with fever, poor appetite, and confusion. She was found to have recurrent pancytopenia and elevated ferritin levels up to 2000 μg/L, suggestive of relapsed HLH. At this time, a second core needle biopsy of the liver was undertaken to confirm relapse of HLH.

Pathologic Findings

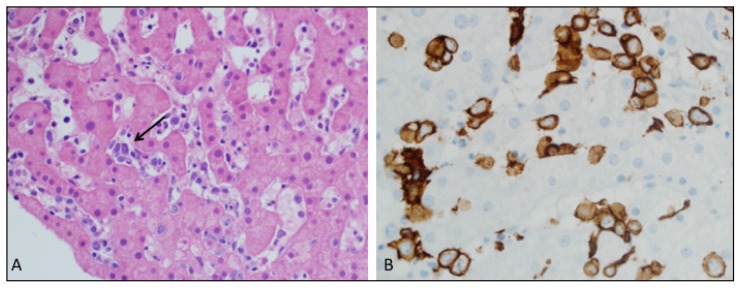

Results of the repeated liver biopsy revealed prominent sinusoidal hemophagocytosis (Figure 4). Apart from the sinusoidal histiocytic inflammation, large atypical-appearing cells exhibiting a B-cell immunophenotype were noted on this sample (Figures 5A and 5B). Results of a repeated bone marrow biopsy similarly revealed large B cells in the bone marrow sinusoids. A diagnosis of IVLBCL was made.

Figure 4.

Hematoxylin-eosin-stained section from the liver biopsy specimen demonstrates prominent sinusoidal hemophagocytosis (arrow) (100× magnification).

Figure 5.

A. Liver sinusoids also demonstrate scattered large atypical-appearing cells and occasional small aggregates of abnormal cells (arrow) suggestive of lymphoma (40× magnification). B. Stain for CD20 highlights large B cells present in the liver sinusoids (60× magnification).

Follow-up and Outcomes

Lymphoma-directed therapy was initiated with 6 cycles of a combination of intravenous rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone. Vincristine was omitted because of her preexisting neuropathy that developed with etoposide therapy. Intravenous methotrexate was used for 3 cycles to prevent CNS relapse. Within 7 days of the start of treatment, her fever resolved, mental status normalized, and blood cell counts recovered. Her aphasia slowly improved during the ensuing months. She completed chemotherapy in January 2019 and is without evidence of disease recurrence systemically or in the CNS as of June 2019. A timeline of the case appears in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of the case

| Relevant medical history and interventions A 68-year-old South Korean woman with no personal history of medical problems and a family history of pancreatic cancer (father), CVA at age 29 (mother), and Hashimoto disease (sister) developed intermittent confusion and unintentional weight loss after a viral upper respiratory tract infection in February 2018. She was given multiple courses of antibiotics, without improvement. Patient originally from South Korea but has lived in Arizona for 30 years. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Summaries from initial and follow-up visits | Diagnostic testing | Interventions |

| Late April 2018 | Patient was admitted with fevers, mostly at night; cognitive deficits and confusion; generalized weakness; and lack of appetite | Laboratory values: White blood cell count, 1300/μL; hemoglobin, 9.5 g/dL; platelet count, 86,000/μL; ferritin, 5030 μg/L; ALT, 75 IU/L; AST, 67 IU/L | HLH-directed treatment with etoposide and dexamethasone, completed in July 2018 |

| Bone marrow biopsy specimen (April 30, 2018): Increased histiocytes with hemophagocytic histiocytes | |||

| Liver biopsy no. 1: Sinusoidal hemophagocytosis, but no sign of malignancy | |||

| May 2018 | Patient had generalized tonic-clonic seizures | Brain MRI no. 1: New scattered diffusion restriction and T2 hyperintensity of right hemisphere and medial left occipital lobe and pons, without any contrast enhancement | Antiepileptic treatment started; seizures controlled with lacosamide, 100 mg twice a day; levetiracetam, 1500 twice daily; and phenytoin, 100 mg 3 times a day |

| CSF analysis: Increased number of histiocytes/macrophages, many showing hemophagocytosis | Intrathecal methotrexate and hydrocortisone therapy for CNS involvement with HLH, weekly for 4 doses | ||

| June 2018 | Patient’s seizures were controlled and there were no recurrent fevers; she was deconditioned and discharged to rehabilitation facility | ||

| July 2018 | Patient was readmitted with a stroke alert for new-onset aphasia and altered mental status | Brain MRI no. 2: Embolic-appearing infarcts in the left MCA territory; no obvious source | Anticoagulation therapy with apixaban, 10 mg twice a day for the loading dose, followed by 5 mg twice daily |

| Echocardiogram was normal | Completed HLH treatment course | ||

| October 2018 | Patient was readmitted with recurrent symptoms of fever and confusion; HLH relapse diagnosed | Ferritin, 2000 μg/L | Lymphoma-directed therapy with 6 cycles of IV rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone |

| Liver biopsy no. 2: Large atypical-appearing B cells in liver sinusoids suggestive of lymphoma | CNS prophylaxis with 3 cycles of IV methotrexate | ||

| January 2019 | Patient presented for follow-up | Chemotherapy completed | |

| June 2019 | Patient was stable and recovering as an outpatient | ||

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; IV = intravenous; MCA = middle cerebral artery; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

DISCUSSION

IVLBCL is a rare, clinically aggressive form of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma characterized by preferential growth of neoplastic lymphocytes in blood vessels. Diagnosis can be elusive because of its constellation of nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as fevers and pain, in addition to CNS and skin involvement.2 Similarly, there are no pathognomonic radiologic changes to support the diagnosis.3 More than half (52%) of patients present with neurologic symptoms, including cognitive impairment, strokelike episodes, seizures, or focal motor weakness.2 Multifocal cerebral infarcts, as described in our patient, have also been reported with IVLBCL.4

HLH is a life-threatening condition that most commonly occurs in adults because of an underlying infection, autoimmune disease, or malignancy. The clinical diagnosis of HLH is based on the criteria used in the HLH-2004 trial, requiring 5 of the following 8 clinical findings: Fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia in at least 2 cell lines, hypertriglyceridemia or hypofibrinogenemia, tissue demonstration of hemophagocytosis, low or loss of natural killer cell activity, elevated serum ferritin level, and an elevated soluble CD25 level.5 Although studies report CNS involvement in HLH ranging anywhere from 30% to 73%, the larger and more systematic studies suggest that approximately two-thirds of patients with HLH have neurologic symptoms.6

Our patient’s initial clinical symptoms and diagnostic findings were consistent with HLH. On initial presentation, the primary cause of the HLH was unclear. An extensive infectious and autoimmune workup was unrevealing in its results. It was only after she had relapse of HLH that a second biopsy specimen revealed IVLBCL, the probable driving condition for her initial presentation of HLH. A review of the first biopsy specimen showed IVLBCL as well, confirming the hypothesis that IVLBCL was present at the beginning of her illness. Malignancy-associated HLH represents 27% of secondary HLH cases.7 Of those, IVLBCL-associated HLH is a rare entity that is typically seen in patients from Asian countries. Most patients (73%–100%) present with typical features of HLH, such as bone marrow involvement, fevers, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenias, with neurologic presentations being relatively common.1 The hematologic findings are less likely observed in the classic or cutaneous variants of IVLBCL and represent important clues to aid in diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Primary HLH is extremely rare in adults, and a secondary cause should be carefully investigated. Our case serves as a reminder that IVLBCL is truly a “chameleon with multiple faces.”2 The Asian variant of IVLBCL is associated with HLH and not uncommonly involves the CNS. Prompt diagnosis of IVLBCL in the appropriate clinical scenario may lead to improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Alyx Porter, MD, is a member of a data safety monitoring committee for a glioblastoma study for Syneos Health.

The other author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors had access to the data, had a role in writing the manuscript, and have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Murase T, Nakamura S, Kawauchi K, et al. An Asian variant of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: Clinical, pathological and cytogenetic approaches to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2000 Dec;111(3):826–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2000.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: A chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018 Oct 11;132(15):1561–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonkem E, Dayawansa S, Stroberg E, et al. Neurological presentations of intravascular lymphoma (IVL): Meta-analysis of 654 patients. BMC Neurol. 2016 Jan 16;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0509-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruto C, Taipa R, Monteiro C, Moreira I, Melo-Pires M, Correia M. Multiple cerebral infarcts and intravascular central nervous system lymphoma: A rare but potentially treatable association. J Neurol Sci. 2013 Feb 15;325(1–2):183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henter J-I, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Feb;48(2):124–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Y, Pei R-J, Wang Y-N, Zhang J, Wang Z. Central nervous system involvement in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: A retrospective analysis of 96 patients in a single center. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018 Apr 5;131(7):776–83. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.228234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George MR. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Review of etiologies and management. J Blood Med. 2014 Jun 12;5:69–86. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S46255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]