Abstract

Introduction

Expressive writing, the process of self-expression through writing, appears to have beneficial effects. Our hospital’s narrative medicine group developed an expressive writing tool, the Three-Minute Mental Makeover (3MMM).

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of the 3MMM to reduce stress and optimize communication between health care practitioners and their patients/families.

Methods

Patients and families were recruited from a Chicago-area children’s hospital from December 2016 through July 2017, from the neonatal intensive care unit, pediatric intensive care unit, inpatient pediatric unit, and outpatient pediatric clinics. Health care practitioners included a pediatric cardiologist, pediatric residents, child development specialists, and pediatric nurses. Practitioner and patient family participants completed prestudy and poststudy surveys to assess perceived stress and communication levels. Using a standardized script, practitioners led the 3MMM activity, writing concurrently with patients/families. Participants then shared their responses. Presurvey and postsurvey data were compared using nonparametric tests.

Results

Eight practitioners led 96 patient/family members in 3MMM activities and study surveys. At baseline, all patients, family members, and practitioners reported experiencing 1 or more symptoms of stress. After participating in the 3MMM, patients/family members and practitioners reported reduced stress compared with baseline (p < 0.001). A significant improvement in communication was reported by practitioners (p < 0.001). Eighty-eight percent of patients/families reported that the 3MMM activity was helpful, even though only 35% had used writing or journaling in the past.

Conclusion

The 3MMM is a short writing exercise that reduces stress for practitioners, patients, and families. Future studies may help determine long-term effects of the 3MMM.

Keywords: expressive writing, narrative medicine, pediatrics, stress reduction

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that there is a strong association between illness and stress.1–4 In addition to the relationship between stress and disease in the patient1,3 and the patient’s family,2,5,6 health care practitioners are subject to stress and burnout.7–11 One method used to help cope with stress is expressive writing (EW), defined as writing about topics such as traumatic or stressful experiences, thoughts and feelings.12–14 Several guided EW techniques have been described to help people manage stress in a wide variety of settings.15–19

To introduce EW in a children’s hospital, our narrative medicine group developed the Three-Minute Mental Makeover (3MMM), a short writing tool for use in clinical practice.20 This was done within the framework of narrative medicine, defined as medicine practiced “with these narrative skills of recognizing, interpreting, and being moved by these stories of illness.”21 The narrative medicine approach aims to improve the effectiveness of care by encouraging empathy, by promoting authentic dialogue, and by creating a shared experience for health care practitioners and patients.22–24 Many authors have recommended incorporating narrative medicine as part of the education of medical students,24–30 residents,31,32 and practicing health care practitioners.22–24,33 However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have used EW in a dyad consisting of both the health care practitioner and the patient/family.

After using the 3MMM with hundreds of patients and families with apparent success, we wanted to measure its effectiveness. We hypothesized that the 3MMM would reduce perceived stress and improve communication for patients, family members, and health care practitioners. This study was approved by the institution’s institutional review board.

METHODS

The 3MMM consists of the health care practitioner and the patient/family writing concurrently, using the following prompts: “1. Write 3 things you are grateful for (be specific). 2. Write the story of your life in 6 words. 3. Write 3 wishes you have.” After writing, the practitioner invites the patient/family participants to join in sharing what they have written.

Seven health care practitioners, including 2 resident physicians, 3 nurses, 1 clinical psychologist, and 1 learning behavioral specialist, volunteered to be trained in the use of the 3MMM. Training sessions for this study started with a brief introduction to the 3MMM activity. The practitioner being trained participated in the 3MMM, writing along with the trainer. Next, the trainee used a standardized script to lead others in the 3MMM activity, until a level of comfort was established. Providers were instructed to incorporate thoughts about and hopes for patient/family members into their writing as a way to enhance connection. Training sessions lasted 15 to 30 minutes each.

Patients and families were recruited from inpatient and outpatient areas of a metropolitan Chicago-area children’s hospital from December 2016 through July 2017, including from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (ICU), Pediatric ICU, inpatient pediatric unit, and outpatient pediatric clinics. Practitioners identified patients and families under their direct care who appeared to be experiencing stress, either by appearance (looking tired, angry, or sad) or by exhibiting behaviors commonly associated with stress (restlessness, lack of focus, or emotional outbursts) and who met the eligibility criteria, which included fluency in English. Families were related to the index patients (the patients being cared for). When the index patients were deemed by the practitioner to be healthy enough and able to write, they were invited to participate in the study.

Using the standardized script, practitioners offered the 3MMM to eligible patients and/or family members. After verbal consent was obtained, the practitioner assigned the patient/family participants a study identification number, which was placed on the packet containing all study materials. All participants (patients/family members and the practitioner) then completed a preactivity survey on paper ranking their perceived level of stress and communication on a scale of 1 to 5; 1 indicated strongly disagree, and 5 indicated strongly agree (see Sidebar: Preactivity and Postactivity Surveys on Three-Minute Mental Makeover [3MMM]). Signs and symptoms of stress were derived from established criteria.34,35

Preactivity and Postactivity Surveys on Three-Minute Mental Makeover (3MMM).

Pre-3MMM survey:

I feel burned out/stressed: (Likert scale 1–5).a

I have experienced these symptoms of burnout/stress in the last _____ (no. of) months.

I feel good about the communication between me and my health care team (Likert scale 1–5).a,b

Post-3MMM survey:

I feel burned out/stressed (Likert scale 1–5).a

I feel good about the communication between me and my health care team (Likert scale 1–5).a,b

In the past, I have used writing or journaling to help cope with difficult situations (Likert scale 1–5).a

This writing exercise was helpful to me (Likert scale 1–5).a

How did this activity change the relationship with your practitioner?b

What did you like?

What didn’t you like?

Any suggestions to improve the activity?

If all identifying information is removed, I give permission to share my writing (signature).

Likert scale: 1) strongly disagree, 2) disagree, 3) neither disagree nor agree, 4) agree, 5) strongly agree.

Provider surveys contained same statement in relation to the patient and/or patient’s family.

Next, practitioners guided the 3MMM activity at the bedside of the index patient or in the examination room for outpatients. Practitioners, family members, and practitioners followed the writing prompts of the 3MMM, writing concurrently. Practitioners and patient/family participants were then given an opportunity to share what they wrote.

After sharing responses, participants completed a postactivity paper survey, assessing past use of expressive writing, the helpfulness of the 3MMM activity, and again ranking stress and communication levels (see Sidebar: Preactivity and Postactivity Surveys on Three-Minute Mental Makeover [3MMM]). Patient/family surveys were not reviewed by the practitioner at the time of completion. All surveys were placed back into the study packet. If permission was given, the practitioner retained copies of the patient’s and family member’s writing. At the conclusion of the activity, patients and family members received a brochure that described the activity and listed resources available at the hospital for addressing stress for patients/family members, such as social work, pastoral care, and Child Life services. This brochure was provided so participants could repeat the activity on their own if they found it helpful and to provide guidance if the activity elicited feelings that they wanted to explore further.

Demographic and other clinical information related to the index patient was collected from the medical record. Survey responses and study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Advocate Children’s Hospital. Analysis was completed using SPSS (Version 25.0 for Windows, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Likert-type rated survey responses, before and after the activity, were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges and were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Spearman rank correlation was used to examine the relationship between survey responses, and the correlation coefficient ρ was reported. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 152 surveys were completed, with 96 surveys by patient/family participants (56 index patients) and 56 surveys by 8 practitioners. Practitioners often led the 3MMM activity with more than 1 family member of an individual patient. The age of index patients ranged from newborn to 24 years. The index patients included inpatients in the Neonatal ICU, Pediatric ICU, and the general pediatrics unit, as well as pediatric outpatients (Table 1). The primary diagnosis of index patients included prematurity, congenital heart disease, neurodevelopmental disorders, anxiety, cystic fibrosis, and other disorders (Sidebar: Patients’ Primary Diagnoses).

Table 1.

Patient demographics (n = 56)

| Demographic characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Male | 24 (42.8) |

| Female | 32 (57.2) |

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.83 (7.99) |

| Range | 0–24.1 |

| LOS, d (n = 43; inpatients only) | |

| Mean (SD) | 35.13 (47.15) |

| Range | 0–245 |

| LOS (survey), d (n = 43; inpatients only) | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.62 (38.55) |

| Range | 0–214 |

| Race, no. (%) | |

| White | 36 (64.3) |

| Asian | 6 (10.6) |

| African American | 3 (5.3) |

| Other | 2 (3.7) |

| Not available | 9 (16.1) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (7.1) |

| Non-Hispanic | 36 (64.3) |

| Unknown | 16 (28.6) |

| Insurance, no. (%) | |

| Public | 9 (16.1) |

| Private | 47 (83.9) |

| Unit of care, no. (%) | |

| Inpatient, Neonatal ICU | 20 (35.7) |

| Inpatient, Pediatric ICU | 9 (16.1) |

| Inpatient, pediatrics | 11 (19.6) |

| Outpatient | 16 (28.6) |

ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay; SD = standard deviation.

Patients’ Primary Diagnoses.

Behavioral health (depression, anxiety)

Cancer

Cardiac disorder (PDA, myocarditis, tachycardia)

Cystic fibrosis

Educational difficulties

Holoprosencephaly

Hydronephrosis

Neurodevelopmental disorder (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, autism)

Prematurity

Traumatic injury

Oncology

Of 102 patients/family members who were initially offered the opportunity to participate in the 3MMM activity, 96 (94%) completed the activity. Patient/family participants in the study included 19 patients (aged 8 to 24 years), 69 parents (49 mothers, 20 fathers), 7 other relatives, and 1 family friend.

Reasons given for not participating in the writing activity included: “I don’t like writing” (n = 3), “My child is too sick for me to concentrate” (n = 2), and “I don’t have time” (n = 1).

Among the 152 patients, family participants, and practitioners who participated in the 3MMM activity, all completed preactivity and postactivity surveys. All 8 practitioners (100%) and 95 (99%) of 96 patient/family participants chose to share their responses.

Stress

In the preactivity surveys, all patient/family participants and practitioners reported experiencing stress, with a variety of symptoms (Table 2). Patient/family participants and practitioners identified exhaustion and not sleeping enough as top symptoms of stress. Patient/family participants reported high levels of frustration and irritability; many practitioners reported increased caffeine intake.

Table 2.

Reported symptoms of stress

| Symptom of stress | Patient/family (n = 96), % | Practitioner (n = 56), % |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased concentration | 48 | 29 |

| Exhaustion | 72 | 84 |

| Eating too much | 17 | 9 |

| Not eating enough | 34 | 20 |

| Forgetfulness | 40 | 23 |

| Frustration | 60 | 34 |

| Getting sick more often | 15 | 7 |

| Increased caffeine intake | 24 | 75 |

| Increase in unhealthy choices | 20 | 7 |

| Increased irritability | 44 | 20 |

| Less time for exercise | 45 | 27 |

| Low motivation level | 32 | 7 |

| Poor job performance | 11 | 0 |

| Sleeping too much | 9 | 2 |

| Not sleeping enough | 66 | 84 |

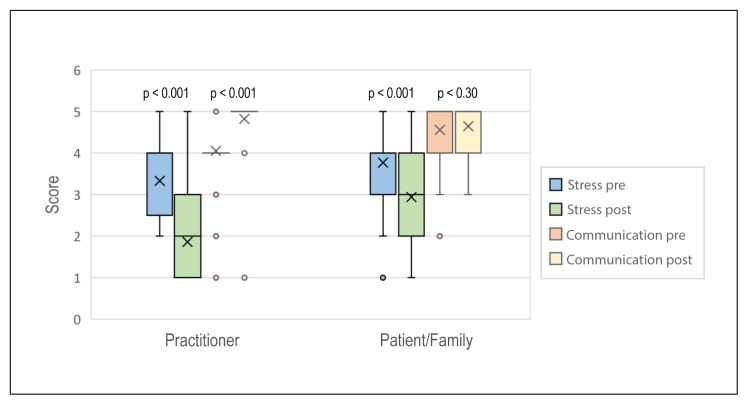

Compared with the preactivity surveys, in the postactivity surveys, patients/family members (median score = 4 vs 3, p < 0.001) and practitioners (median score = 4 vs 2, p < 0.001) reported a significant reduction in stress (Figure 1). Patients/families (ρ = 0.41, p < 0.01) and practitioners (ρ = 0.45, p < 0.01) with greater baseline stress had a greater reduction in stress after the 3MMM activity. Although changes in stress did not differ by patient type/unit among patients/families, practitioners experienced the most substantial reduction in stress in the Neonatal ICU (median preactivity vs postactivity score = 3 vs 1, p < 0.001) and outpatient areas (median preactivity vs postactivity score = 3.5 vs 2, p < 0.001). Among patients/families, there was an inverse correlation between historical use of writing and reduction in stress (ρ = −0.22, p = 0.03). That is, there was greater improvement in stress levels among those who had not previously used journaling to help deal with stress. Among health care practitioners, there was a positive correlation between historical use of writing and reduction in stress (ρ = 0.43, p = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Results of preactivity and postactivity survey responses on the Three-Minute Mental Makeover (3MMM).a

a Percentages in left graph do not total to 100% because of rounding.

X (in bars) = median.

Communication

Patients/families reported good communication with the health care team both before and after participating in the 3MMM (median preactivity vs postactivity score = 5 vs 5 [maximum score of 5]). Practitioners reported improved communication with patients/families after the 3MMM activity (median preactivity vs postactivity score = 4 vs 5, p < 0.001; Figure 1). When analyzed by patient type/unit, perceived communication after the 3MMM activity improved significantly among families only in the Neonatal ICU (median change = 0, interquartile range = 0–1, p = 0.008).

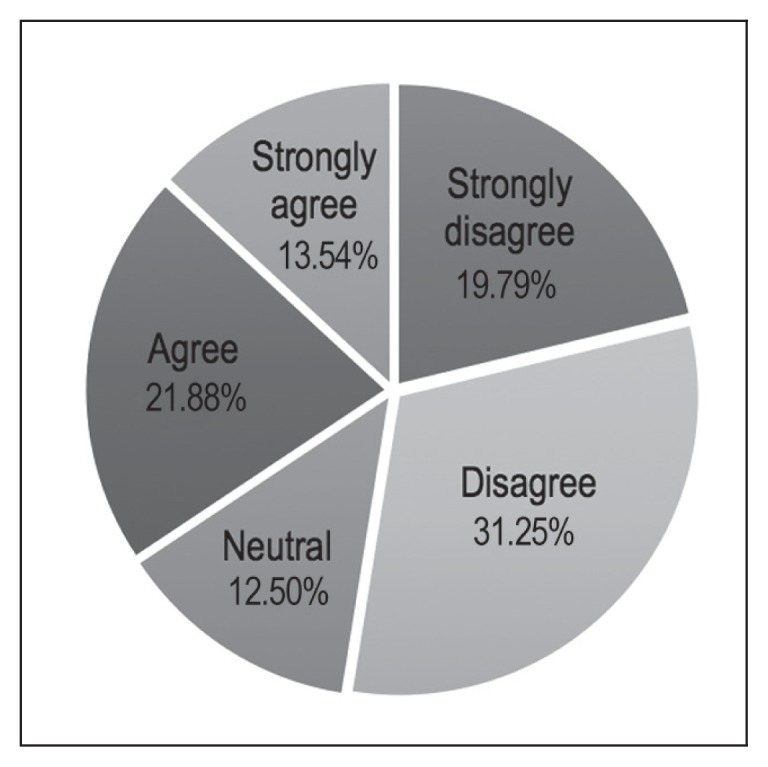

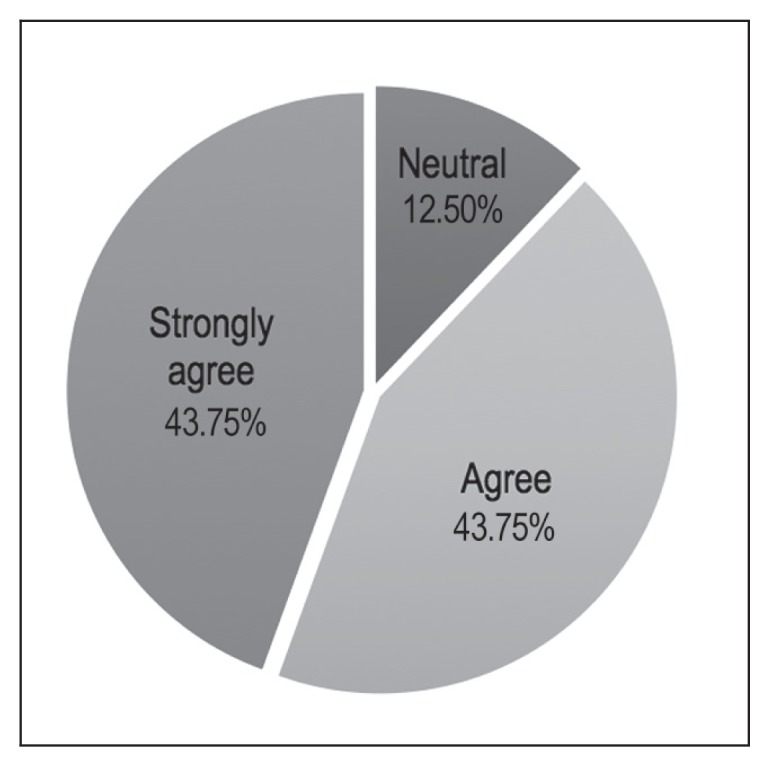

Eighty-eight percent of patients/families reported that the 3MMM activity was helpful, 12% were neutral, and no patients/families reported that the activity was not useful (Figure 2). This positive response to writing occurred even though only 35% of patients/families had previously used writing to cope with difficult situations (Figure 2).

Figure 2A.

Percentages of patient/family responders who reported use of writing in the past.

Written comments by families and patients about the 3MMM were generally positive. The Sidebar: Written Comments of Patient/Family Members describes selected comments by patient/family participants.

Written Comments of Patient/Family Members.

How did the writing exercise change your relationship with your practitioner?

Deeper, more personal. Feel like a real team.

One hour ago he was a stranger. Now I have confided some of my deepest secrets and trust him with my daughter’s care.

I think it helped my son and myself be more at ease with the doctor. It was nice to see my son actually share information.

What did you like about the writing exercise?

Time, true sincerity, care, concern, passion.

I was able to write something down that I usually don’t share.

Made me think of things other than the present.

It’s easy to do.

It’s short.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study is that a brief, shared writing exercise is efficacious in enhancing communication and reducing self-perceived stress for patients and health care practitioners in the medical setting.

EW has previously been shown to improve mental health, including depression,36–38 postpartum depression,39–42 and posttraumatic stress disorder in ICU settings,43,44 as well as to increase resiliency in caregivers of chronically ill people.45–47 Additionally, EW can improve physical health in a variety of other health conditions, including asthma and rheumatoid arthritis,48,49 hypertension,50 wound healing,51,52 and HIV.53 In previous studies of health care practitioners, EW has been shown to promote resiliency, enhance empathy, and decrease burnout.24–27,30,32,54

Most EW techniques described in the literature require a very large investment of time in training and execution,12–19 which could be a limitation for busy clinicians who may believe they do not have the expertise to use writing with their patients. Although some authors found benefits after participating in short gratitude writing exercises55–57 and others found improvements after writing for just 2 minutes on 2 consecutive days,58 we found no reports of writing techniques used by health care practitioners with their patients in clinical practice.

Unlike previous EW techniques, the 3MMM was designed to be used by practitioners with their patients in clinical settings. Patients, families, and health care practitioners all reported lower stress after participating in this time-limited, guided writing exercise. Most patients and families thought the 3MMM writing exercise was helpful, independent of past use of journaling to cope with stress. The 3MMM activity appears to be different from most previously reported EW techniques in 3 important respects: It is brief, it involves guidance by the practitioner, and it features concurrent participation in a dyad of practitioner and patient/family member.

Because it is brief, the 3MMM may be used within the constraints of a busy clinical practice. Although the 3MMM does involve a small investment in time, our experience is that using the 3MMM often improves overall efficiency because highly stressed patients and families can take up an inordinate amount of practitioners’ time. By offering patients and family members a structured way to feel heard, the 3MMM can promote team building, improve overall care, and cut down on the number of “unanswerable,” repetitive questions that are often posed by patients and families in difficult medical situations.

The 3MMM is guided by practitioners who know their patients/families well, so they can initiate the 3MMM for those who are most stressed and build on and improve the existing therapeutic relationship. In our opinion, this is preferable to being guided by a writing “expert” who does not know the patient/families, as is the case in most previous studies of therapeutic use of EW.12–18,36,37

A distinctive feature of the 3MMM is concurrent writing: Practitioners writing alongside and about the patient/family. It was our impression that positive feelings, for both the practitioner and patient/family, were enhanced when the practitioner wrote something about the patient/family. We believe this simultaneous writing and partner sharing was crucial to the positive findings, and may have helped channel and develop the therapeutic relationship.

The success of the 3MMM in reducing perceived stress for patients, families, and practitioners may be explained by “common factors” such as alliance, collaboration, and empathy, which have been noted in psychology studies to be important for developing an effective therapeutic relationship.59–61 These common factors may have encouraged a collaborative approach among practitioner and patient/family members, as suggested by patient/family participants’ and practitioners’ perception of high levels of communication even at baseline (see Sidebar: Preactivity and Postactivity Surveys on Three-Minute Mental Makeover [3MMM]). Practitioners reported that the 3MMM improved communication with patients and families. Written comments suggested patient/family participants experienced feelings associated with common factors, which would be expected to enhance any therapeutic relationship (see Sidebar: Written Comments of Patient/Family Members). Although this connection is positive and desirable, it may also have influenced the postsurvey responses because patient/family participants may have not wanted to disappoint their practitioner’s expectations of helping them relieve stress. To limit the influence of this potential limitation, surveys were not reviewed by practitioners at the time of the study interaction.

Most practitioners in the current study had no previous experience leading writing activities, yet after a short training session, all were successful in guiding their patients in the 3MMM activity in clinical settings. Results of the current study suggest it would be possible for many health care practitioners to incorporate the 3MMM into their clinical practices.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, there was no control group in this study. It is possible that any expression of compassion by the practitioner may have yielded similar benefits. This was not measured in this study. Future studies might include control patients/families who participate in a neutral writing exercise or who do not participate in any writing exercise, and compare similar prewriting and postwriting responses with those who participate in the 3MMM activity.

A second limitation is the subjective nature of the surveys. That is, the surveys reflect self-reported evaluations of stress and relationships. Future research to evaluate more objective measures of stress might be helpful, such as measurement of cortisol or catecholamine levels. Finally, a third limitation is that because the study required fluency in English, populations who spoke other languages were not included.

It is unknown what the long-term effects of the 3MMM exercise are, whether those who participate in the 3MMM subsequently use journaling to reduce stress and process life events, or how the 3MMM might best be used by practitioners for hospital and outpatient settings. We are currently conducting a follow-up study to assess the long-term effects of participating in a single 3MMM exercise.

CONCLUSION

In an age of time constraints in most clinical settings, the 3MMM is a simple, brief writing exercise that can be used by health care practitioners in a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings. The 3MMM was helpful even for people who had not used journaling or EW in the past. The 3MMM is a new way to help patients and families better cope with stress. Health care practitioners who write alongside their patients may decrease their own stress and improve communication for all participants.

Figure 2B.

Percentages of patient/family responders who reported finding Three-Minute Mental Makeover (3MMM) activity helpful.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Rosa Wills for her administrative support and assistance with data entry. Thanks to all the practitioner participants in this study: William Nelson, RN; Kathryn Frazier, RN; Robin Van Sickel, RN; Emily Dudek, MD; as well as the authors. Thanks to Victoria Koren, MLS, Manager, Advocate Aurora Library Network; and Eileen Greene, Library Technical Assistant, for their help obtaining reference articles.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions

David G Thoele, MD, conceptualized and developed the 3MMM writing tool, designed and implemented the study, participated as a practitioner in the study, and directed manuscript development.

Cemile Gunalp assisted with the study and survey design, collected data, and assisted with manuscript development.

Danielle Baran, PhD; Jamie Harris, MD; and Marjorie A Getz, PhD; assisted with tool and study design, participated as practitioners in the study, and contributed to manuscript development.

Douglas Moss collected data, and assisted with manuscript development.

Yi Li, MD, provided statistical assistance and also guidance in content and interpretation of the manuscript.

Ramona Donovan, MS, RD, CCRC, assisted with study design and implementation, and contributed to manuscript development.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Mishel M. Perceived uncertainty and stress in illness. Res Nurs Health. 1984 Sep;7(3):163–71. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke SO, Costello EA, Handley-Derry MH. Maternal stress and repeated hospitalizations of children who are physically disabled. Child Health Care. 2010 Spring;18(2):82–90. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc1802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehnet A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. Psychooncology. 2007 Mar;16(3):181–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 Jul-Aug;22(4):261–9. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. FAMIREA Study Group. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2005 May 1;171(9):987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wightman A, Zimmerman CT, Neul S, Lepere K, Cedars K, Opel D. Caregiver experience in pediatric dialysis. Pediatrics. 2019 Feb;143(2):e20182102. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Mar 5;136(5):358–67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff (Milwood) 2011 Feb;30(2):202–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014 Mar;89(3):443–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct 8;172(18):1377–85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tawfik DS, Phibbs GS, Sexton JB, et al. Factors associated with practitioner burnout in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2017 May;139(5):e20164134. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth JM, Pennebaker JW. Sharing one’s story: Translating emotional experiences into words as a coping tool. In: Snyder CR, editor. Coping: The psychology of what works. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennebaker JW. Expressive writing in psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018 Mar;13(2):226–9. doi: 10.1177/1745691617707315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennebaker JW, Seagal JD. Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. J Clin Psychol. 1999 Oct;55(10):1243–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986 Aug;95(3):274–81. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.95.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing: Connections to physical and mental health. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford handbook of health psychology. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 417–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.L’Abate L, Kern R. Workbooks: Tools for the expressive writing paradigm. In: Lepore SL, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 239–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennebaker JW, Evans JF. Expressive writing: Words that heal. Enumclaw, WA: Idyll Arbor Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennebaker JW, Smyth JM. Opening up by writing it down: How expressive writing improves health and eases emotional pain. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoele D, Gunalp J, Getz M, et al. Families and health care practitioners writing together: An evidence-based activity for everyday clinical practice. Poster presented at: American Academy of Pediatrics Annual Meeting; November 3, 2018; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charon R. The sources of narrative medicine. In: Charon R, editor. Narrative medicine: Honoring the stories of illness. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charon R. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001 Oct 17;286(15):1897–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charon R. What to do with stories: The sciences of narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007 Aug;53(8):1265–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy JW, Franz BA. Narrative medicine in a hectic schedule. Med Health Care Philos. 2016 Dec;19(4):545–51. doi: 10.1007/s11019-016-9718-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoyt MA, Austenfeld J, Stanton AL. Processing coping methods in expressive essays about stressful experiences: Predictors of health benefit. J Health Psychol. 2016 Jun;21(6):1183–93. doi: 10.1177/1359105314550347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wald HS, Haramati A, Bachner YG, Urkin J. Promoting resiliency for interprofessional faculty and senior medical students: Outcomes of a workshop using mind-body medicine and interactive reflective writing. Med Teach. 2016 May;38(5):525–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chretien KC, Swenson R, Yoon B, et al. Tell me your story: A pilot narrative medicine curriculum during the medicine clerkship. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jul;30(7):1025–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3211-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly W, Neubauer B, Hemann B, LaRochelle J, O’Neill JT. Innovative pre-clerkship clinical experience (CLINEX) Med Educ. 2016 May;50(5):581. doi: 10.1111/medu.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balmer D, Gill A, Nuila R. Integrating narrative medicine into clinical care. Med Educ. 2016 May;50(5):581–2. doi: 10.1111/medu.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller E, Balmer D, Herman N, Graham G, Charon R. Sounding narrative medicine: Studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014 Feb;89(2):339–42. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winkel AF, Feldman N, Moss H, Jakalow H, Simon J, Blank S. Narrative medicine workshops for obstetrics and gynecology residents and association with burnout measures. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct;128(Suppl 1):27S–33S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diorio C, Nowaczyk M. Half as sad: A plea for narrative medicine in pediatric residency training. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183109. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009 Sep 23;302(12):1284–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stress effects: How is stress affecting you? [Internet] Weatherford, TX: American Institute of Stress; 1979–2018. [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: www.stress.org/stress-effects/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stress symptoms: Effects on your body and behavior [Internet] Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic; 1998–2018. [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress-symptoms/art-20050987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gortner E-M, Rude SS, Pennebaker JW. Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behav Ther. 2006 Sep;37(3):292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, Deldin PJ, Askren MK, Jonides J. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: The benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013 Sep 25;150(3):1148–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: An online randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):310–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Blasio P, Camisasca E, Caravita SC, Ionio C, Milani L, Valtolina GG. The effects of expressive writing on postpartum depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychol Rep. 2015 Dec;117(3):856–82. doi: 10.2466/02.13.PR0.117c29z3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horsch A, Tolsa J-F, Gilbert L, du Chene JL, Mueller-Nix C, Bickle Graz M. Improving maternal mental health following preterm birth using an expressive writing intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016 Oct;47(5):780–91. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Blasio P, Ionio C, Confalonieri E. Symptoms of postpartum PTSD and expressive writing: A prospective study. J Prenat Perinat Psychol Health. 2009;24:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Graaff LF, Honig A, Van Pampus MG, Stramrood CA. Preventing post-traumatic stress disorder following child-birth and traumatic birth experiences: A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018 Jun;97(6):648–56. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kadivar MK, Seyedfatemi N, Akbari N, Haghani H, Fayaz M. Evaluation of the effect of narrative writing on the stress sources of the parents of preterm neonates admitted to the NICU. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017 Jul;28(13):938–43. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1219995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadivar MK, Seyedfatemi N, Akbari N, Haghani H. The effect of narrative writing on maternal stress in neonatal intensive care settings. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015 May;30(8):1616–20. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.937699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harvey J, Sanders E, Ko L, Manusov V, Yi J. The impact of written emotional disclosure on cancer caregivers’ perceptions of burden, stress, and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Health Commun. 2018 Jul;33(7):824–32. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1315677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riddle JP, Smith HE, Jones CJ. Does written emotional disclosure improve the psychological and physical health of caregivers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2016 May;80:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cash TV, Lageman SK. Randomized controlled expressive writing pilot in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. BMC Psychol. 2015 Nov 30;3:44. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1999 Apr 14;281(14):1304–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lumley MA, Leisen JC, Partridge RT, et al. Does emotional disclosure about stress improve health in rheumatoid arthritis? Randomized, controlled trials of written and spoken disclosure. Pain. 2011 Apr;152(4):866–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckwith McGuire KM, Greenberg MA, Gevirtz R. Autonomic effects of expressive writing in individuals with elevated blood pressure. J Health Psych. 2005 Mar;10(2):197–209. doi: 10.1177/1359105305049767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koschwanez HE, Kerse N, Darragh M, Jarrett P, Booth RJ, Broadbent E. Expressive writing and wound healing in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2013 Jul-Aug;75(6):581–90. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829b7b2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson H, Jarrett P, Vedhara K, Broadbent E. The effects of expressive writing before or after punch biopsy on wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2017 Mar;61:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.11.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004 Mar-Apr;66(2):272–5. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116782.49850.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen P-J, Huang CD, Yeh S-J. Impact of a narrative medicine programme on healthcare practitioners’ empathy scores over time. BMC Med Educ. 2017 Jul 5;17(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rippstein-Leuenberger K, Mathner O, Sexton JB, Schwendimann R. A qualitative analysis of the Three Good Things intervention in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2017 Jun 13;7(5):e015826. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Killen A, Macaskill A. Using a gratitude intervention to enhance well-being in older adults. J Happiness Stud. 2015 Aug;16(4):947–64. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9542-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lai ST, O’Carroll RE. “The Three Good Things”—The effects of a gratitude practice on wellbeing: A randomised controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2017 Mar;26(1):10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burton CM, King LA. Effects of (very) brief writing on health: The two-minute miracle. Br J Health Psychol. 2008 Feb;13(Pt 1):9–14. doi: 10.1348/135910707X250910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenzweig S. Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1936 Jul;6(3):412–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1936.tb05248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry. 2015 Oct;14(3):270–7. doi: 10.1002/wps.20238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wampold BE, Budge SL. The 2011 Leona Tyler Award address: The relationship—and its relationship to the common and specific factors of psychotherapy. Couns Psychol. 2012 May 1;40(4):601–23. doi: 10.1177/0011000011432709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]