Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the associations of war and post-conflict factors with mental health among Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers as adults.

Method:

In 2002, we recruited former child soldiers from lists of soldiers (aged 10–17) served by Disarmament, Demobilization, Reintegration centers and from a random door-to-door sample in five districts of Sierra Leone. In 2004, self-reintegrated child soldiers were recruited in an additional district. At 2016/17, 323 of the sample of 491 former child soldiers were reassessed. Subjects reported on war exposures and post-conflict stigma, family support, community support, anxiety/depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Results:

72% of subjects were male; mean age, 28. 26% reported killing or injuring others; 67% reported being victims of life-threatening violence; 45% of female, 5% of male subjects, reported being raped; 32% reported death of a parent. In 2016/17 (Wave 4), 47% exceeded the threshold for anxiety/depression; 28% exceeded the likely post-traumatic stress disorder threshold. Latent class growth analysis yielded three trajectory groups based on changes in stigma and family/community acceptance; “Improving Social Integration” (n = 77) fared nearly as well as the “Socially Protected” (n = 213). The “Socially Vulnerable” group (n = 33) had increased risk of anxiety/depression above the clinical threshold and possible PTSD and were around three times more likely to attempt suicide.

Conclusion:

Former child soldiers had elevated rates of mental health problems. Post-conflict risk and protective factors related to outcomes long after the end of conflict. Targeted social inclusion interventions could benefit long-term mental health of former child soldiers.

Keywords: child soldiers, Sierra Leone, conflict, stigma, global mental health

Introduction

In some of the world’s most violent armed conflicts, the exploitation of children by armed groups has doubled in recent years. Colloquially referred to as “child soldiers,” they may face forced family separation, loss of access to school and healthcare, insecure access to food and shelter, displacement from homes and communities, death of loved ones, and sexual assault, and witness or participate in killings.1 Mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD are common among former child soldiers. Given their association with armed groups, former child soldiers may face stigma and lack of family and community acceptance.2

How war experiences operate within the post-conflict environment to shape long-term health and social functioning of former child soldiers is not well understood. Despite high rates of mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among former child soldiers,3,4 research on the topic is fraught with realities of heterogeneity in timing, severity, and type of exposure.5 Moreover, limited research on adult life outcomes is available. The limited longitudinal research in Northern Ireland,6 northern Uganda,3,7 the Democratic Republic of Congo,8 and Mozambique9 reveals a range of risk factors that influence the lives of former child soldiers.

Exposure to certain “toxic stressors” (frightening/life-threatening experiences in absence of support from attachment figures) has been associated with poor outcomes. Being a victim of sexual violence/rape was associated with increased risk of anxiety and depression4,10,11 and PTSD,12 and being beaten or threatened to be killed was also associated with increased risk of PTSD.13,14 Children who perpetrated violence had interpersonal deficits and higher hostility and aggression later in life. Child soldiers involved in armed groups at younger ages had higher levels of anxiety and depression. Overall, the prevalence, type, severity, and timing of war trauma have been associated with decreased school completion, high rates of mental health problems, and criminal involvement in adulthood. Based on evidence from studies of war-exposed youth and of children exposed to extreme and/or compound adversity, it is expected that war experiences and post-conflict risk and protective factors will shape adult mental health and life outcomes.15

Research examining the post-conflict environment reveals important leverage points that can help improve social integration among former child soldiers. In northern Uganda, research described how many of the former child soldiers with poor outcomes had encountered challenges in achieving educational and economic stability.16 Post-conflict stressors facing former child soldiers are associated with anxiety and depression problems in adulthood.17,18,19 Perceived stigma, lack of community or family acceptance, or physical abuse/neglect within the family, have been associated with poorer mental health over time. Protective factors, such as family and community acceptance, forgiveness, or traditional healing rituals and community sensitization interventions may also have a positive influence on the long-term outcomes of former child soldiers.9,20 There is evidence that despite horrific trauma positive developmental outcomes in adulthood may be possible if adequate resources and supports are available.21,22

The Longitudinal Study of War-Affected Youth (LSWAY) is a four-wave (2002–2017), prospective study of a cohort of male and female former child soldiers who participated in Sierra Leone’s eleven-year civil war (1991–2002), infamous for its involvement of child soldiers. In this study we consider if post-conflict family and community support are associated with mitigated long-term harm, and whether stigma is associated with exacerbated harm.

Method

Participants

LSWAY was launched in collaboration with a non-governmental organization (NGO) working with the Government of Sierra Leone.2 Assessments were conducted at four time points (T1: 2002, T2: 2004, T3: 2008 and T4: 2016/2017), beginning just after the cessation of hostilities. The sample (N=529) was drawn from multiple sources to capture the diversity of experiences in study participants. Subjects aged 10–17 who were involved with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) or other armed groups who had been referred to Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) programs or were on lists of self-reintegrated former child soldiers in five districts (Bo, Kenema, Kono, Moyamba, and Pujehun) were invited to participate in the study (n = 259). A random door-to-door survey of youth of similar age not served by DDR programs (n = 136) was administered in the same five regions. Additional self-reintegrated youth were added at T2 from an outreach list identified by an NGO in the Makeni region (n = 127) (see Table S1, available online, for greater detail).

Trained Sierra Leonean research assistants conducted private interviews with subjects lasting 1–3 hours (all data in the present study are from participant interviews). Consents/assents and all study protocols were administered orally in Krio, the most widely-spoken language. Subjects were given a small gift of foodstuffs and supplies for participation. Referrals were made for risk of harm situations due to suicidality or urgent mental health issues; approximately 1% needed referral at each wave. At baseline, procedures were approved by the Office of Human Research Administration at Boston University and later at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Measures

Mixed methods were used to establish culturally meaningful and valid assessments of mental health, risk and protective factors, and social functioning.23,24All measures were self-report and were selected and adapted in consultation with local staff and community members.25 Focus group discussions among youth and adults similar to the study population were used to develop items and determine the face validity and cultural appropriateness of scales. All measures were forward- and back-translated following a standard protocol.26

Items from the Child War Trauma Questionnaire27 were introduced at T2 (and at T3 or T4 for participants not interviewed at T2) to assess individual war experiences. Four war experiences were considered “toxic” exposures: 1) experiencing direct personal threat due to war violence; 2) death of a caregiver due to war; 3) being a victim of rape/sexual assault; 4) injuring or killing others. This measure also included age of abduction and length of time with fighting forces.

Mental health was assessed using the Oxford Measure of Psychosocial Adjustment (OMPA). Subscales for hostility (mean of 11 items, range 1–4, T1–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.78) and prosocial behaviors (mean of 9 items, range 1–4, T1–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.74) were used in this analysis. Beginning at T2, anxiety and depression were measured using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist/SF-25 (HSCL-25)28 (mean of 25 items, range 1–4, T2–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.90), post-traumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the 9-item version of the Child Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (PTSD-RI)29 (mean, range 0–4, T2–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.86), both of which have been used to assess children and adolescents globally.5,30 Emotion dysregulation was assessed at T4 using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)31 (mean of 24 items, range 1–5, T4 Cronbach’s α=.95).

Family and community acceptance measures were developed locally (Table S2, available online). Community Acceptance, assessed subjects’ perceived acceptance from the community at all waves (mean of six items, range 0–2, T1–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.86). Family Acceptance assessed subjects’ perceived acceptance from family beginning at T2 (mean of six items, range 0–2, T2–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.88). Stigma and perceived discrimination were assessed T2–T4 with an adaptation of the 9-item Everyday Discrimination Scale,32 capturing negative community interactions; stigma due to being a former child soldier is used in this analysis (sum, range 0–9, T2–T4 average Cronbach’s α=0.88).

Participants were asked if they were currently in school, highest grade level achieved, employment at wave of assessment, about involvement in crime, current use of alcohol and drugs, and if they had a partner. Intimate partner violence was assessed using the Conflict Tactics Scale (range 0–8, T4 Cronbach’s α=0.65).33 Demographic information such as gender and age were collected at each wave using the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.34

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sample characteristics, social functioning, and mental health outcomes in adulthood and to describe community and social factors and mental health indicators over time. We compared our participants to an age- and sex-standardized population of respondents to the nationally representative 2013 (latest available) Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) using harmonized demographic indicators (Table S3, available online).35

Next, to address the study’s aim of examining whether post-war family and community supports were associated with the reduced long-term negative consequences of the war exposures, we first used latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to sort subjects into groups based on changes over time in stigma, family acceptance, community acceptance and related group membership at T4 using a semiparametric mixture model.36 We estimated the probability that an individual belonged to a trajectory group, based on his/her observed pattern of risk and protective factors, and then assigned group membership using the highest classification probability across trajectories. Age, gender, and previous war experiences were included as time-stable covariates. These trajectories were used to characterize a participant’s “social integration.” Best fit was based on Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), average posterior probabilities (APP) of group membership, and odds of correct classification (OCC).37

Finally, we conducted logistic regression analyses to evaluate whether war experiences and social integration trajectory membership were associated with anxiety and depression, PTSD, suicide attempts, perpetration of intimate partner violence, substance use, involvement with police, primary school completion, and employment at T4, controlling for gender and age. Unless data are missing completely at random, analysis of only complete cases is likely to result in biased results.38 Missing data occurred for several reasons. In completing scales, respondents may not have supplied a response to one or more items or not responded to one or more indicator variables. At T2 some youth originally interviewed at T1 were not re-interviewed because data collection stopped prematurely due to the death of the director of the collaborating NGO in a UN helicopter crash, but many were re-contacted at T3. For descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses, we used multiple imputation methods presented by Plumpton et al.39 that allow combined imputation of item-level and scale/indicator missingness via the STATA plug-in command ice, which implements chained equations.40 We used all cases (N=529), including 38 youth who were not involved with the fighting forces, to create 30 imputed data sets. For the latent class growth analysis, full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to address missingness.41 For the present analysis we reduced the analytic data set to N=323 former child soldiers interviewed at T4 in order to have full information on adult life outcomes and mental health. We used inverse probability weighting to account for loss to follow up.42

For tests unrelated to the central aim of the paper linking social integration to mental health and social functioning at T4, we provide unadjusted p-values and 95% confidence intervals throughout the results. For the logistic regressions relating to the central aim, we provide both estimated and adjusted p-values in a supplemental table. It is worth noting, however, that lowering the type I error (i.e., α) has the effect of increasing type II error, the chance of rejecting a true effect in the population. Finding such effects is more consistent with the goals of the present study.

Results

Characteristics of the T4 Sample

Characteristics of the sample at T4 are displayed in Table 1. The sample was predominantly male (72%, n=231) and evenly divided between Christian (50%, n=160) and Muslim (50%, n=162). Most youth (86%, n=275) were abducted/forced into armed groups at a mean age of 10.9 years and remained an average of 3.0 years. About a quarter of the sample (26%, n=84) reported killing or injuring others. Two thirds (67%, n=216) reported having been victims of life-threatening violence (i.e., shot or stabbed, beaten, or violently injured); 16% (45%, n=40 of female and 5%, n=11 of male subjects) reported being raped during the war; and 32% (n=101) reported having a parent die during the war. On average, subjects reported 1.4 (s.d.=0.06) cumulative war exposures, more among female (1.8, s.d.=0.12) than male subjects (1.3, s.d.=0.06).

Table 1.

Estimated Means and Percentages (With Standard Errors) for Characteristics of Male and Female Child Soldiers, Trajectory Groups (N=323)

| Full sample (N=323) | Female Subjects (n=91) | Male Subjects (n=232) | Socially Protected (n=213) | Improving Social Integration (n=77) | Socially Vulnerable (n=33) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior War Experiences | ||||||

| Experienced the death of a parent | 32% (.03) | 38% (.05) | 29% (.03) | 27% (.03) | 40% (.06) | 50% (.09) |

| Was a victim of rape | 16% (.02) | 45% (.05) | 5% (.01) | 12% (.02) | 37% (.06) | 10% (.05) |

| Was a victim of life-threatening violence | 67% (.03) | 69% (.05) | 66% (.03) | 64% (.03) | 76% (.05) | 75% (.08) |

| Killed or injured others during the war | 26% (.02) | 23% (.04) | 28% (.03) | 19% (.03) | 32% (.06) | 66% (.09) |

| Cumulative war exposures (range 0–4) | 1.4 (.06) | 1.8 (.12) | 1.3 (.06) | 1.2 (.06) | 1.9 (.13) | 2 (.16) |

| Age of abduction/joined fighting forces (4–18) | 10.9 (.20) | 11.0 (.41) | 10.9 (.22) | 11.0 (.23) | 12.0 (.75) | 10.5 (.62) |

| Years involved with fighting forces (0.25–11) | 3.0 (.15) | 2.3 (.35) | 3.2 (.17) | 3.0 (.18) | 2.6 (.56) | 2.8 (.33) |

| Demographics at Time 4 | ||||||

| Age (21–32) | 28.0 (.21) | 27.0 (.39) | 28.4 (.24) | 27.8 (.24) | 29.2 (.92) | 27.9 (.62) |

| Male | 72% (.03) | - | - | 79% (.03) | 53% (.12) | 97% (.03) |

| Married, living with partner, or engaged | 54% (.03) | 49% (.05) | 56% (.03) | 52% (.03) | 64% (.10) | 51% (.10) |

| Has biological children | 68% (.03) | 75% (.05) | 66% (.03) | 64% (.03) | 75% (.08) | 78% (.05) |

| Adult caregivers not financially responsible for care | 70% (.03) | 69% (.05) | 70% (.03) | 67% (.03) | 85% (.07) | 76% (.05) |

| Education and Employment | ||||||

| Completed primary school | 80% (.02) | 68% (.05) | 85% (.02) | 79% (.02) | 71% (.11) | 84% (.04) |

| Currently working or self-employed | 40% (.03) | 36% (.05) | 42% (.03) | 52% (.03) | 41% (.12) | 44% (.05) |

| Currently a student | 9% (.02) | 13% (.04) | 8% (.02) | 12% (.02) | 7% (.50) | 2% (.02) |

| Community and Social Factors | ||||||

| Stigma due to being a former child soldier (0–9; α=.88) | 0.5 (.01) | 0.0 (.03) | 0.6 (.10) | 0.3 (.07) | 0.3 (.29) | 1.0 (.23) |

| Community acceptance (0–2; α=.86) | 1.5 (.02) | 1.6 (.04) | 1.5 (.02) | 1.6 (.03) | 1.6 (.48) | 1.3 (.05) |

| Family acceptance (0–2; α=.88) | 1.6 (.02) | 1.8 (.03) | 1.6 (.01) | 1.7 (.02) | 1.6 (.08) | 1.4 (.06) |

| Risk Behaviors | ||||||

| Substance use (alcohol or drug use in typical week) | 31% (.03) | 10% (.03) | 39% (.03) | 29% (.03) | 24% (.11) | 39% (.06) |

| Trouble with police/law | 5% (.01) | 2% (.02) | 6% (.02) | 3% (.01) | 11% (.06) | 11% (.04) |

| Perpetrator of IPV (assault, past year, among those with an intimate partner, n=193) | 39% (.04) | 17% (.05) | 47% (.04) | 36% (.04) | 53% (.12) | 42% (.07) |

| Mental Health | ||||||

| Prosocial attitudes (OMPA, 1–4, higher is good; α=.74) | 3.1 (.02) | 3.1 (.04) | 3.1 (.03) | 3.1 (.02) | 3.2 (.08) | 3.0 (.05) |

| Externalizing (OMPA, 1–4; α=.78) | 1.4 (.02) | 1.4 (.03) | 1.4 (.02) | 1.4 (.02) | 1.4 (.50) | 1.5 (.03) |

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (DERS, 1–5; α=.95) | 1.9 (.04) | 1.7 (.06) | 1.9 (.04) | 1.9 (.04) | 1.9 (.14) | 1.9 (.07) |

| Anxiety and Depression (HSCL, 1–4; α=.90) | 1.7 (.03) | 1.7 (.05) | 1.8 (.03) | 1.7 (.03) | 1.8 (.10) | 1.7 (.05) |

| Anxiety and Depression (% above clinical threshold, 1.75) | 47% (.03) | 43% (.05) | 49% (.03) | 46% (.03) | 43% (.10) | 47% (.06) |

| PTSD (PTSD-RI, 0–4; α=.86) | 1.2 (.04) | 1.0 (.08) | 1.4 (.06) | 0.6 (.02) | 0.7 (.08) | .6 (.04) |

| PTSD (% above clinical threshold) | 28% (.02) | 20% (.04) | 31% (.03) | 26% (.03) | 43% (09) | 28% (.05) |

| Ever attempted suicide (self-report) | 11% (.02) | 9% (.03) | 11% (.02) | 9% (.01) | 21% (.08) | 10% (.04) |

Note: Score ranges for non-dichotomous measures are provided in parentheses, followed by the average Cronbach’s alpha for all time periods at which the measure was collected. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; HSCL = Hopkins Symptoms Checklist; IPV = intimate partner violence; OMPA = Oxford Measure of Psychosocial Adjustment; PTSD-RI = Post Traumatic Stress Disorder–Reaction Index.

At T4, the mean age of participants was 28.0 (s.d.=0.21) years (range 21–32 years). Approximately half (54%, n=171) of the LSWAY sample was married, living with a partner, or engaged at T4 compared to 66% of the DHS sample who were married or partnered. Sixty-eight percent (n=219) of the youth in our sample reported having biological children, which was similar to the DHS sample (72%). Due to NGO efforts, the majority of our sample (80%, n=258; 85% of male, 68% of female subjects) had completed primary school, more than twice as many as in the DHS reference data (44% overall, 50% of male, 30% of female subjects). The mean number of years of schooling reported by each participant was 8.8 (9.3 years for male, 7.4 years for female subjects). Nine percent of our sample (n=31; 8% of male, 13% of female subjects) reported currently being a student. Only 40% (n=159; 42% of male, 36% of female subjects) of the LSWAY former child soldiers reported being currently employed (including self-employed), compared to 82% (86% of male, 72% of female subjects) in the DHS sample.

At T4 approximately 31% (n=99) of LSWAY former child soldiers (39% of male, 10% of female subjects) reported using alcohol or drugs in a typical week.43 Among those with an intimate partner (n=194), 39% (n=82; 47% of male, 17% of female subjects) reported having physically assaulted (i.e., pushed/shoved, slapped, slammed against a wall, hit with a physical object, used a knife or weapon against, or forced to have sex) their intimate partner in the past year, which is considerably higher than in the DHS sample, (13%; 16% of male and 5% of female subjects). At T4, 5% (n=16) of the sample reported ever having been in trouble with the police (no comparable DHS statistics were available).

Fifteen years following the conflict, nearly half the sample (47%, n=153; 49% of male, n=114; 43% of female subjects n=39) reported levels of anxiety and depression symptoms above conventional international cut-offs (mean score>1.75, using the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist/SF-25, HSCL-25; range 1–4). More than a quarter (28%, n=90; 31% of male, n=72; 20% of female subjects, n=18) reported PTSD symptoms above the threshold for “possible PTSD” on the nine-item version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (PTSD-RI; range 0–4).44,45 Eleven percent of the LSWAY former child soldiers (n=34; 11% of male, n=26; 9% of female subjects n=8) reported having attempted suicide.

Mean levels of social factors and mental health indicators over time

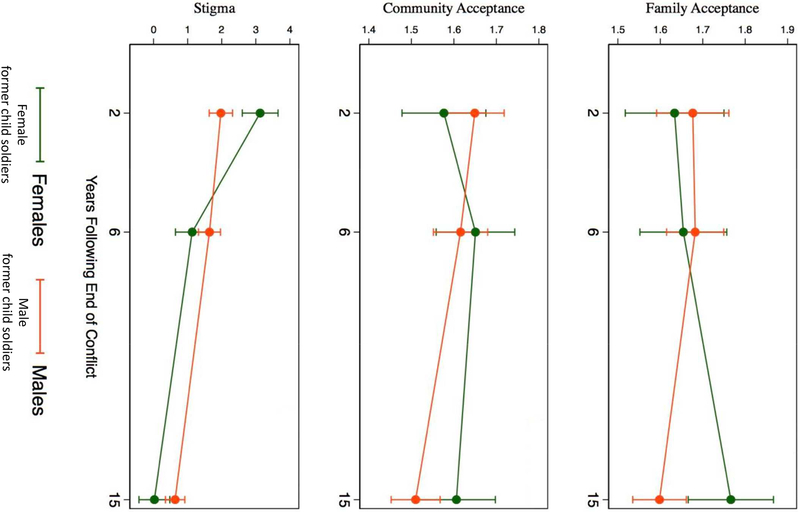

Mean levels of social factors over time are shown in Figure 1. Overall, perceived stigma due to being a child soldier diminished, from a mean of 2.3 at T2 to a mean of 0.5 at T4 (mean change per year following conflict =−0.14; 95% CI: −0.16, −0.11). Community and family acceptance diminished slightly over time. Mean community acceptance was 1.8 at T1 and fell to 1.5 at T4 (mean change per year following conflict =−0.01; 95% CI: −0.02, −0.01). Average family acceptance dropped just slightly from 1.8 at T2 to 1.6 at T4 (mean change per year following conflict =−0.00; 95% CI: −0.01, 0.01). Female former child soldiers generally reported higher stigma and lower community and family acceptance than male former combatants in earlier waves (T1–T2), but by T4 female subjects’ perceptions of community and social factors improved, such that at T4, female subjects reported lower levels of perceived stigma and higher levels of family acceptance compared to male subjects as seen in the figure.

Figure 1. Estimated Mean Levels of Community and Social Factors Over Time by Sex (N=323).

Note: Figure 1 shows estimated mean levels of family acceptance, community acceptance, and perceived stigma with 95% confidence intervals for female subsample and male subsample, using 30 multiply imputed datasets.

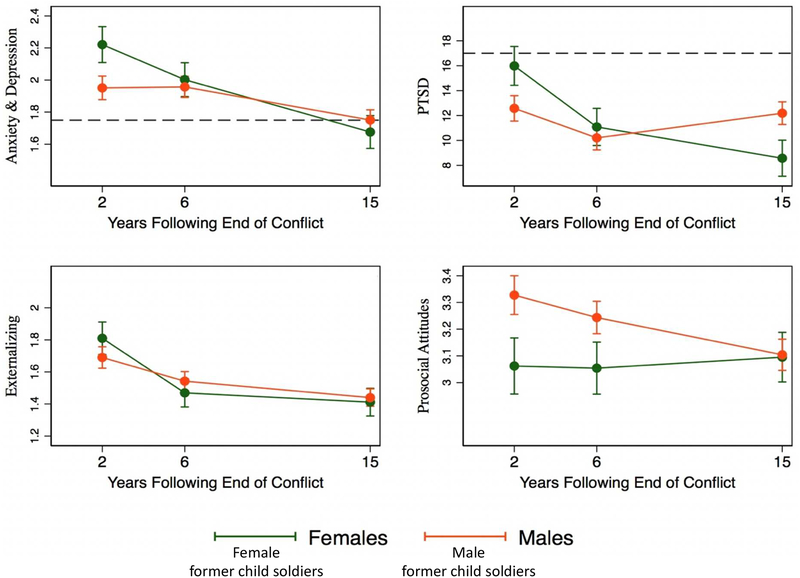

Figure 2 presents average trajectories of depression, anxiety, PTSD symptoms, and prosocial behaviors over time by sex. From T2 to T4, mean anxiety and depression scores decreased from 2.0 to 1.7 (mean change per year following conflict =−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.02); the percentage of those above the cut-off decreased from 63% at T2 to 47% at T4. Mean PTSD symptom scores decreased from 1.6 to 1.2 (mean change per year following conflict =−0.01; 95% CI: −0.01, −0.00) with 28% of the sample above the cut-off at T4, down from 36% at T2. Both male and female former child soldiers showed improvements over time in anxiety and depression to the point where the mean values were just below diagnostic cut-offs at T4. Although female former child soldiers had higher depression, anxiety, and PTSD scores compared to their male counterparts at T2, female former combatants show greater improvement in these indicators. By T4 male and female former child soldiers look similar on depression and anxiety. Externalizing behaviors abate for both sexes. While PTSD shows steady improvement for female subjects, the pattern for male subjects is less clear with T4 values looking not much improved over those observed at T2. Male former child soldiers started higher on prosocial attitudes post-conflict but dropped sharply over the three time points while their female counterparts remained steady, such that by T4 the two genders appeared about equal.

Figure 2. Estimated Mean Levels of Mental Health Problems Over Time by Sex (N=323).

Note: Figure 2 shows estimated mean levels of anxiety and depression, PTSD, externalizing behaviors, and prosocial attitudes with 95% confidence intervals for female subsample (green line) and male subsample (orange line). Horizontal dashed lines in the top graphs indicate conventional international cut-off scores.

Social integration trajectories

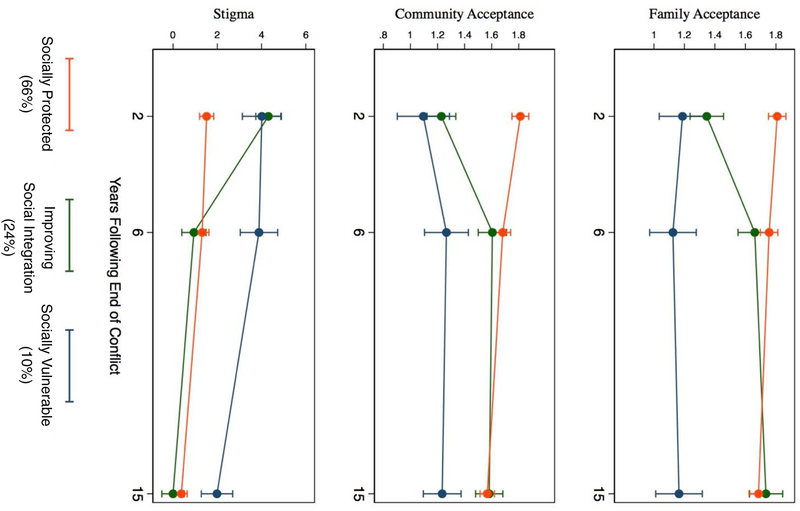

Latent classes of social integration trajectories were identified from latent class growth analyses. Based on the sample-size-adjusted BIC, the three-group solution (BIC=3802) was optimal. Model fit statistics for two-, three-, four-, and five-class solutions are presented in Supplement 1, available online. The average posterior probability (APP) of assignment for each participant into the three social integration trajectory groups ranged from .84 to .90, well above the recommended threshold of .70.43 The odds of correct classification (OCC) ranged from 7.35 to 105.09, above the standard threshold of 5.0.

The largest class of the three (66% of the sample, n=213) was categorized as “Socially Protected” indicating lower perceived stigma and higher community and family acceptance across all time points, with small but significant decreases in community acceptance (mean change =−0.13, 95% CI −0.20, −0.06) and family acceptance (mean change =−0.41, 95% CI −0.57, −0.25) over time. The next largest latent class was labeled as “Improving Social Integration” (24%, n=77) demonstrating high stigma and low community and family acceptance at T2, with a considerable decrease in stigma (mean change =−1.07, 95% CI −2.63, 0.51) and increase in family (mean change =0.21, 95% CI (−0.08,0.51) and community acceptance (mean change =0.20, 95% CI 0.04, 0.36) at T3 which leveled off between T3 and T4 for community acceptance. The smallest latent class (10% of the sample, n=33) was categorized as “Socially Vulnerable,” characterized by high stigma and low community and family acceptance at T2. Trajectories for each of these latent group classifications are displayed in Figure 3. Of the time-stable covariates, male former child soldiers had significantly greater likelihood of belonging to the Socially Vulnerable group (long-odds estimate =1.82, t(322)=3.44, p<.001).

Figure 3. Latent Group Classification of Social Integration Trajectories Estimated by Full Information Maximum Likelihood (N=323).

Note: In figure 3, estimated latent classes of social integration trajectories with 95% confidence intervals are presented by social risk (perceived stigma) and protective (family and community acceptance) factor measures. A three-group solution was optimal, based on the sample-size adjusted BIC, resulting in a “Socially Protected” group (n=213), an “Improving Social Integration” group (n=77), and a “Socially Vulnerable” group (n=33).

Table 1 presents demographics and war experiences by social integration trajectory group. The former child soldiers in the Socially Protected group experienced fewer cumulative toxic war exposures than the other two trajectory groups (p<.001 for both comparisons). Strikingly, the Improving Social Integration group was made up of a much greater proportion of female child soldiers (69%) than the sample as a whole (28%) and consequently had a higher proportion of victims of rape compared with the other two groups. In contrast, all but one of the former child soldiers in the smaller Socially Vulnerable group were male and had a high rate of perpetrating injuring or killing as compared to the other two groups.

To pursue the study’s aim of examining the relationship of social supports to long-term outcomes, logistic regressions of three latent classes of social integration trajectories on social functioning and mental health outcomes were estimated to evaluate whether group membership was associated with anxiety and depression, PTSD, suicide attempts, perpetration of intimate partner violence, substance use, involvement with police, primary school completion, and employment at T4 adjusting for cumulative toxic war experiences, gender and age. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of experiencing mental health problems, engaging in risk behaviors, and achieving positive social functioning outcomes are reported in Table 2. Former child soldiers in the Socially Vulnerable group, compared with those in the Socially Protected group, were about two times more likely to experience levels of anxiety/depression above the conventional clinical threshold (OR=2.17, 95% CI 1.01, 4.77) and possible PTSD (OR=2.41, 95% CI 1.07, 5.42), around three times more likely to have attempted suicide (OR=2.96, 95% CI 1.01, 8.69), and over four times more likely to have been in trouble with the police (OR=4.53, 95% CI 1.38, 14.86). In general, T4 adult life outcomes among the Improving Social Integration group were not significantly different compared to the Socially Protected group on theT4 outcomes examined in the present study.

Table 2.

Estimated Odds Ratios (and 95% Confidence Intervals) for Mental Health and Life Outcomes by Social Integration Trajectory Group (N=323)

| Mental Health Outcomes | Social Functioning Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/Depression | PTSD | Ever Attempted Suicide | Perpetrator of IPVa | Substance Use | Ever in Trouble with Police | Employed | Completed Primary School | |

| Trajectory Group | ||||||||

| Socially protected (n=213, 66%) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Improving social integration (n=77, 24%) | .75 | .79 | .81 | 1.36 | 1.12 | 3.39 | .55 | 1.89 |

| Socially vulnerable (n=33, 10%) | 2.17 | 2.41 | 2.96 | 2.44 | 1.72 | 4.53 | 1.12 | 1.39 |

| Male | 1.10 (.61, 1.97) | 1.70 (.90, 3.23) | 1.01 (.38, 2.70) | 5.52 (2.05, 14.83) | 5.66 (2.62, 12.23) | 5.03 (1.20, 21.05 | .66 (.37, 1.19) | 4.59 (2.20, 9.56) |

| Age at T4 | .92 (.87, .98) | .96 (.89, 1.03) | 1.03 (.92, 1.15) | .92 (.84, 1.01) | 1.02 (.95, 1.09) | 1.06 (.91, 1.24) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) | .82 (.75, .89) |

| War experiences (cumulative) | 1.02 (.81, 1.28) | 1.27 (.99, 1.63) | 1.19 (.76, 1.88) | 1.20 (.86, 1.68) | 1.06 (.80, 1.39) | 1.53 (.96, 2.43) | .94 (.74, 1.18) | .93 (.67, 1.28) |

Note: “Socially Protected” was the omitted (reference) group for logistic regressions, which also controlled for gender (male), age at T4, and cumulative war experiences. Odds ratios and confidence intervals were estimated using 30 imputed datasets. Estimated probability values and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted probability values for logistic regression predicting mental health and life outcomes by social integration trajectory group are presented in Table S4, available online. Correlation coefficient matrix for mental health and social functioning outcomes is presented in Table S5, available online. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Logistic regressions predicting intimate partner violence (IPV) were run on a subsample (n=194) of participants who reported having ever had an intimate partner.

Discussion

This study is unique in following a cohort of former child soldiers prospectively from the end of hostilities to adulthood. Nonetheless, our findings align with other studies of former child soldiers,2,8 studies of adult war veterans,46 and studies of adults who faced adversities as children.22,47,48Adult mental health and social functioning in Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers were related to their war experiences and to post-conflict risk and protective factors. The mental health trajectories suggest that while some improvement comes over time, some problems, such as anxiety and depression, are more intractable than others and that gender has an important role to play, as in the case of shifting risk patterns by gender for PTSD. Our LCGA analyses revealed that the Socially Protected group began with fewer toxic war exposures, but also had lower levels of perceived stigma, higher levels of community and family acceptance post-conflict, as well as lower odds of anxiety/depression, PTSD, attempted suicide, and involvement with police at T4. The group characterized by Improving Social Integration suffered just as harshly during the war as those on the Socially Vulnerable trajectory yet at adulthood looked comparable to the Socially Protected group on rates of mental health problems and suicidality. The Socially Vulnerable group experienced minimal improvement in stigma and acceptance over time and compared to the socially protected group demonstrated increased risk of anxiety/depression, PTSD, attempted suicide, and involvement with police.

We can only hypothesize about all the ways in which the experiences of the Socially Improving and the Socially Vulnerable group differ. Perhaps there are unmeasured differences in their war experiences, or differences in their own behaviors, such as hostility or negative affect that may affect how former child soldiers with adverse war experiences differ from one another in how they are perceived and accepted by family and community. While we find no significant differences between these groups in immediate reintegration services post-war, it is unknown what sorts of formal or informal social supports they may have experienced in the post-conflict environment. Gender may certainly play a role, but how it interacts with the post-conflict social environment is not clear.

Limitations include the use of self-reports of symptoms and functioning as this analysis has focused on youth self-reports of adult outcomes. Although our measures of mental health were adapted for use in Sierra Leone and indicators of validity and psychometric performance were good, the clinical cut-points used have not been validated with reference to diagnoses from local clinicians. We cannot make claims of causality based on these data given that the war-related experiences were reported retrospectively, and we have included both life outcomes occurring at T4 along with risk and protective factors assessed at all time points, including T4, to best characterize social integration trajectories. For example, we cannot state that the post-conflict experiences of stigma and support shaped the mental health and life outcomes. It is possible, for example, that improvements in mental health led to greater acceptance, which, in turn led to improved life outcomes.

Our trajectory analyses are relative to others within the sample and the small number of in the Socially Vulnerable trajectory group indicates that in general the trajectories in our sample were on trends of slow improvement; however, these findings must be seen in context of the continued high levels of mental health distress in the full sample. Even though just one small group in this study has been identified as experiencing greater difficulty in life outcomes compared to the other two at T4, it should not be taken to mean the other two groups are thriving. Comparisons to the DHS statistics, which themselves include former child soldiers and other war-affected youth, demonstrate that this sample of former child soldiers has had more access to education but also lower rates of favorable outcomes such as marriage and employment which may indicate difficulty integrating into larger society. Although representative national data on mental disorders in this setting are not available, we do see that using standard clinical cut-points, our sample demonstrates mental health problems at high rates with 49% of male and 43% of female subjects falling into the range of standard clinical cut-points for likely depression/anxiety and 31% of male and 20% of female subjects falling into the likely clinical range for PTSD.

Although experiences of war-related violence and loss cannot be undone, three leverageable post-conflict factors (family and community acceptance and stigma) appear related to adult outcomes and merit further study. Our analyses suggest that campaigns to reduce stigma against former child soldiers may offer promising targets to improve mental health and life outcomes. Studies have identified the value of targeted interventions, such as group-based programs addressing the mental health needs of war-affected youth in post-conflict settings and services to bolster protective opportunities, such as school and livelihood opportunities, which can improve social and family acceptance.49

Our findings on gender are informative considering several campaigns in Sierra Leone to address additional vulnerability in female former child soldiers overlooked in the early phases of Sierra Leone’s approaches to reintegration. Several different processes may help explain the change in gender-related vulnerability over time. For instance, social pressure on male former combatants may increase as they approach the transition to adulthood and are expected to make a living and provide for their families. Such factors could explain why female former child soldiers saw greater acceptance over time, while their male counterparts perceived diminished acceptance. In addition, there might be more peer pressure or social acceptance of self-destructive coping mechanisms in male former child soldiers, such as drinking, drugs, and fighting.

Our results emphasize the importance of monitoring and attending to post-conflict community and family relationships as well as underlying mental health conditions.50 Understanding the combined influence of multiple war-related and post-conflict factors is important for identifying leverage points for programs and policies. Through such investments, the resilience and human capital inherent in the lived experience surviving former child soldiers and other war-affected youth may one day be better realized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; grant 4R01HD073349-05). Dr. Gilman’s contribution was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Drs. Betancourt, Thomson, Brennan, Gilman, and VanderWeele and Ms. Antonaccio report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author’s statement: Theresa S. Betancourt (TSB) accepts full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. TSB attests that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted. TSB supervised the study and RTB contributed significantly to the acquisition of data. TSB, DLT, RTB, TV and SEG contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version. Authors declare no competing interests. All tables and figures are original and are not under copyright.

References

- 1.Betancourt TS, Thomson D, VanderWeele TJ. War-Related Traumas and Mental Health Across Generations. JAMA psychiatry. 2018;75(1):5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(6):606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Schuyten G, De Temmerman E. Post-traumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet. 2004;363(9412):861–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancourt TS, Borisova I, Rubin-Smith J, Gingerich T, Williams T, Agnew-Blais J. Psychosocial adjustment and social reintegration of children associated with armed forces and armed groups: The state of the field and future directions. Austin, TX: Psychol Beyond Borders; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betancourt TS, McBain R, Newnham EA, Brennan RT. Trajectories of internalizing problems in war-affected Sierra Leonean youth: Examining conflict and post-conflict factors. Child Dev. 2013;84(2):455–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Cairns E. Children and political violence from a social ecological perspective: Implications from research on children and families in Northern Ireland. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12(1):16–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annan J, Blattman C, Horton R. The state of youth and youth protection in Northern Uganda. Uganda: UNICEF; 2006;23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayer CP, Klasen F, Adam H. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. JAMA. 2007;298(5):555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boothby N, Crawford J, Halperin J. Mozambique child soldier life outcome study: Lessons learned in rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. Glob Public Health. 2006;1(1):87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betancourt TS, Borisova II, Williams TP, et al. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Dev. 2010;81(4):1077–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boxer P, Rowell Huesmann L, Dubow EF, et al. Exposure to violence across the social ecosystem and the development of aggression: A test of ecological theory in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Child Dev. 2013;84(1):163–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betancourt TS, Borisova II, De la Soudiere M, Williamson J. Sierra Leone’s child soldiers: war exposures and mental health problems by gender. J Adolesc Heal. 2011;49(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, Oyok T, Sondorp E. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The hidden health trauma of child soldiers. Lancet. 2004; 363(9412):831 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blattman C, Annan J. The consequences of child soldiering. Rev Econ Stat. 2010;92(4):882–898. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Tol WA, et al. Social ecology of child soldiers: child, family, and community determinants of mental health, psychosocial well-being, and reintegration in Nepal. Transcult Psychiatry. 2010;47(5):727–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Tol WA, et al. Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. JAMA. 2008;300(6):691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santacruz ML, Arana RE. Experiences and psychosocial impact of the El Salvador civil war on child soldiers. Biomedica. 2002;22(suppl 2):283–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science (80.). 2007;318(5858):1937–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson ML. Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(484):1481–1495. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. A Qualitative Study of Mental Health Problems among Children Displaced by War in Northern Uganda. Transcult Psychiatry. 2009;46(2):238–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohrt B, Jordans M, Tol W, Luitel N, Maharjan S, Upadhaya N. Validation of Cross-Cultural Child Mental Health and Psychosocial Research Instruments: Adapting the Depression Self-Rating Scale and Child PTSD Symptom Scale in Nepal. Vol 11; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacMullin C, Loughry M. Investigating Psychosocial Adjustment of Former Child Soldiers in Sierra Leone and Uganda. J Refug Stud. 2004;17(4):460–472. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, et al. Preparing Instruments for Transcultural Research: Use of the Translation Monitoring Form with Nepali-Speaking Bhutanese Refugees. Transcult Psychiatry. 1999;36(3):285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macksoud MS. Assessing war trauma in children: A case study of Lebanese children. J Refug Stud. 1992;5(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Layne CM, Olsen JA, Baker A, et al. Unpacking Trauma Exposure Risk Factors and Differential Pathways of Influence: Predicting Postwar Mental Distress in Bosnian Adolescents. Child Dev. 2010;81(4):1053–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams D, Yan Yu, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straus M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman D. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNICEF, “Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey”; 2014.

- 35.Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL) and ICF International. 2014. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Freetown, Sierra Leone and Rockville, Maryland, USA: SSL and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagin DS, Tremblay R. Parental and early childhood predictors of persistent physical aggression in boys from kindergarten to high school. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klijn SL, Weijenberg MP, Lemmens P, van den Brandt PA, Lima Passos V. Introducing the fit-criteria assessment plot – A visualisation tool to assist class enumeration in group-based trajectory modelling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;26(5):2424–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White IR, Carlin JB. Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Stat Med. 2010;29(28):2920–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plumpton CO, Morris T, Hughes DA, White IR. Multiple imputation of multiple multi-item scales when a full imputation model is infeasible. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royston P Multiple imputation of missing values: Update of ice. Stata J. 2005; Volume 05:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. Guilford Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Höfler M, Pfister H, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. The use of weights to account for non-response and drop-out. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr. 2005;40(4):291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bøås M, Hatløy A. Alcohol and drug consumption in post war Sierra Leone: an exploration. Fafo - Institute for Applied International Studies Report 496 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pynoos RS, Rodriguez N, Steinberg AS, Stauber C. UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV. UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofmann SG, Litz BT, Weathers FW. Social anxiety, depression, and PTSD in Vietnam veterans. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(5):573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dube S, Anda R, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Williamson D, Giles W. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington HL, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1135–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wessells MG. Child Soldiers: From Violence to Protection. Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Denov M, Ricard-Guay A. Girl soldiers: towards a gendered understanding of wartime recruitment, participation, and demobilisation. Gend Dev. 2013;21(3):473–488. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.