Key Points

Emicizumab prophylaxis achieved substantial efficacy and was well tolerated in children with hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

Emicizumab may offer a new standard of care that reduces treatment burden in young patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors.

Abstract

Emicizumab, a bispecific humanized monoclonal antibody, bridges activated factor IX (FIX) and FX to restore the function of missing activated FVIII in hemophilia A. Emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors was investigated in a phase 3 trial (HAVEN 2). Participants, previously receiving episodic/prophylactic bypassing agents (BPAs), were treated with subcutaneous emicizumab: 1.5 mg/kg weekly (group A), 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks (group B), or 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks (group C). Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy (including an intraindividual comparison of participants from a noninterventional study) were evaluated. Eighty-five participants aged <12 years were enrolled. In group A (n = 65), the annualized rate of treated bleeding events (ABRs) was 0.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.17-0.50), and 77% had no treated bleeding events. Intraindividual comparison of 15 participants who previously took BPA prophylaxis showed that emicizumab prophylaxis reduced the ABR by 99% (95% CI, 97.4-99.4). In groups B (n = 10) and C (n = 10), ABRs were 0.2 (95% CI, 0.03-1.72) and 2.2 (95% CI, 0.69-6.81), respectively. The most frequent adverse events were nasopharyngitis and injection-site reactions; no thrombotic events occurred. Two of 88 participants developed antidrug antibodies (ADAs) with neutralizing potential, that is, associated with decreased emicizumab plasma concentrations: 1 experienced loss of efficacy, and, in the other, ADAs disappeared over time without intervention or breakthrough bleeding. All other participants achieved effective emicizumab plasma concentrations, regardless of the treatment regimen. Emicizumab prophylaxis has been shown to be a highly effective novel medication for children with hemophilia A and inhibitors. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02795767.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Congenital hemophilia A results from mutations in the factor VIII (FVIII) gene (F8) with consequent deficiency of coagulation FVIII, which leads to a lifelong bleeding tendency. Frequent and recurrent bleeding into joints, muscles, and potentially life-threatening locations (central nervous system) can result in significant long-term sequelae.1 Regular prophylactic IV infusions of FVIII are the standard-of-care treatment of pediatric persons with hemophilia A, and early prophylaxis improves long-term clinical outcomes.2-6 However, up to 30% of previously untreated persons with hemophilia A develop neutralizing anti-FVIII antibodies (inhibitors), which render replacement therapy ineffective. This leads to significant medical complications, increased morbidity and mortality, and decreased health-related quality of life.7,8 Inhibitors typically develop within the first 50 exposure days to FVIII therapy and therefore early in life (median age, 1.7-3.3 years).9-11 Current management options for children with hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors include immune tolerance induction (ITI) to eradicate inhibitors, and episodic or prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs; activated prothrombin complex concentrates [aPCCs], recombinant FVIIa [rFVIIa]), whose efficacy can be suboptimal and unpredictable.12-16 Furthermore, because children with inhibitors frequently require high-volume infusions, they are more likely to require central venous access devices (CVADs) and as a result are prone to catheter-related complications, including infection and/or thrombosis.17,18 More effective prophylactic options with reduced treatment burden are needed for pediatric persons with hemophilia A with inhibitors.

Emicizumab, a bispecific humanized monoclonal antibody, bridges activated FIX and FX, thereby restoring the function of missing FVIIIa in hemophilia A.19-21 Emicizumab has demonstrated efficacy in bleed prevention when administered weekly, every 2 weeks, and every 4 weeks in adolescent/adult persons with hemophilia A with and without inhibitors.22-24 In a phase 3 trial, we assessed the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of emicizumab prophylaxis in pediatric persons with hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is an ongoing phase 3, multicenter, nonrandomized, open-label trial, investigating emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A with inhibitors. To enable direct comparisons of outcomes with prior BPAs vs emicizumab prophylaxis, all participants from a noninterventional study (NIS; clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02476942) who met the eligibility criteria for this study were permitted to enroll in HAVEN 2 (group A) and were included in an intrapatient comparison. These patients were selected by site investigators based on their availability and eligibility. Individuals aged 2 to 11 years with congenital hemophilia A and a history of high-titer FVIII inhibitors (≥5 Bethesda units/mL), and who were receiving episodic or prophylactic treatment with BPAs, were eligible to participate. Adolescents aged 12 to 17 years weighing <40 kg were also permitted to enroll, provided they met the other eligibility criteria. Infants/toddlers aged <2 years and determined by the investigator to have a high unmet medical need could potentially be enrolled, depending on results of an interim analysis (further information on the interim analysis can be found later in this section). Participants were required to have adequate hematological, hepatic, and renal function. Patients were ineligible for the study if they had ongoing/planned ITI therapy. Comprehensive eligibility criteria are listed in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

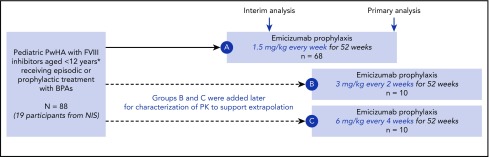

Participants received emicizumab prophylaxis subcutaneously with 4 once-weekly loading doses of 3 mg/kg body weight followed by a maintenance regimen of 1.5 mg/kg weekly (group A; Figure 1). Patients were provided with exact weight-based doses, without rounding for either loading or maintenance dosing; emicizumab was discarded if need be.

Figure 1.

Study design. Loading dose of 3 mg/kg/week for 4 weeks in all cohorts; maintenance dose starting week 5. *With additional inclusion of persons with hemophilia A (PwHA) 12 to 17 years old weighing <40 kg. No PwHA <2 years old or 12 to 17 years old could enroll in groups B and C. A, group A; B, group B; C, group C; NIS, noninterventional study; PK, pharmacokinetics.

As this was a first-in-child study, a joint monitoring committee (JMC) comprising external experts and sponsor members was established to review interim analysis results after the first 10 participants had completed ≥12 weeks of treatment. This review was performed to determine whether the maintenance dose was appropriate in children, and whether participants aged <2 years could be recruited. Both were considered appropriate. To investigate the possibility of flexible dosing frequencies, maintenance regimens of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks (group B) and 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks (group C) were subsequently added to the study (Figure 1). Recruitment to groups B and C occurred in parallel after group A was fully enrolled. Alternate group allocation was performed via an interactive voice/web response system (S-Clinica Sprl, Brussels, Belgium).

Participants could receive episodic treatment with BPAs as needed (eg, for management of breakthrough bleeds; see supplemental Methods for details). Following identification of thrombotic events (TEs) and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) cases in participants enrolled in the HAVEN 1 study who received multiple doses of aPCC while receiving emicizumab, the HAVEN 2 protocol was amended to recommend avoiding the use of aPCC in combination with emicizumab in participants who had the option of using other BPAs to treat bleeds. If aPCC was the only available BPA, the lowest dose expected to achieve hemostasis was to be prescribed, with ≤50 U/kg administered as an initial dose. Study treatment was administered for ≥52 weeks; participants could then continue in this study or switch to commercial emicizumab if available.

Using an electronic handheld device, the primary caregivers of participants recorded all bleeding events and information about these events as soon as they occurred, in addition to administration of hemophilia-related medications and emicizumab. Definitions of bleeding events and collection of records via a Bleed and Medication Questionnaire were as described previously.23 Data on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were collected during clinic visits prior to emicizumab dosing at week 1 and every 12 weeks thereafter. Participants aged ≥8 years used the Haemophilia-Quality of Life-Short Form (Haemo-QoL-SF) questionnaire.25 Caregivers reported their perception of their child’s HRQoL, and on aspects of caregiver burden via the Adapted Health-Related Quality of Life in Haemophilia Patients with Inhibitors (Inhib-QoL) questionnaire; the Inhib-QoL tool was field tested and validated in a group of caregivers of children with inhibitors.26 Numbers of days missed by participants from daycare/school due to hemophilia-related problems were also collected.

With the exception of minor surgeries such as CVAD removals and tooth extractions, planned surgeries were prohibited during the study. However, unplanned surgeries did occur. Perioperative management was determined by the treating physician.

The trial was initiated in July 2016 and conducted at 27 centers in 10 countries across North America, Central America, Europe, Africa, and Asia (supplemental Methods) in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the relevant independent ethics committee/institutional review board at each center. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legally acceptable representatives, and assent was obtained from children (aged 8-11 years) and adolescents (aged 12-17 years).

End points

HAVEN 2 was designed to be a descriptive study; as such, no primary or secondary end points were defined. Efficacy end points were (1) the rate of treated bleeding events (hereafter referred to as the bleeding rate), all bleeding events (treated and untreated), and spontaneous, joint, and target joint bleeding events; (2) intraindividual comparisons of bleeding rates in participants aged <12 years with well-documented BPA prophylaxis from participation in the NIS; and (3) HRQoL of children aged 8 to 17 years and caregiver-reported HRQoL and aspects of caregiver burden.

The presence of target joints was recorded at trial entry. Target joints were defined as major joints (eg, hip, elbow, shoulder, knee, ankle) in which ≥3 bleeding events occurred over a 24-week period. Target joint resolution was defined as ≤2 bleeding events in a 52-week period in a joint previously defined as a target joint27 (supplemental Methods).

Safety end points were adverse events, serious adverse events, thrombotic events, injection-site reactions, abnormal laboratory values (hematology and serum chemistries), and the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs). In the absence of a neutralizing ADA assay, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles were used to identify ADAs with neutralizing potential (see supplemental Methods). Laboratory abnormalities were assessed at screening, every 2 weeks during weeks 2 to 4, every 4 weeks during weeks 7 to 49, and every 12 weeks from week 57 onwards. Antiemicizumab antibodies were assessed predose at weeks 1, 5, 17, 33, and 49, and every 12 weeks from week 57 onward. The pharmacokinetic objective was to characterize emicizumab exposure over time to confirm the appropriate pediatric dose. Pharmacokinetic sampling was performed prior to drug administration on day 1, every week during weeks 1 to 4, every 2 weeks during weeks 5 to 9, every 4 weeks during weeks 13 to 37, every 8 weeks during weeks 41 to 57, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Depending on recruitment feasibility and clinical considerations, ∼60 eligible participants were to be enrolled in group A. Participants aged <2 years were enrolled in group A following the interim analysis and JMC review; recruitment remained open for participants aged <2 years after the group was fully accrued. Ten participants each were enrolled in groups B and C to support pharmacokinetic characterization; the study was not designed for efficacy comparisons across regimens. No formal statistical hypothesis testing was planned. All analyses are descriptive. The primary analysis for all arms was performed 52 weeks after all participants in the primary population of group A (aged ≥2 years) had enrolled or withdrawn prematurely, whichever occurred first. At the primary analysis, 59 participants had completed >52 weeks of the study. The clinical cutoff date for this analysis was 30 April 2018.

Efficacy and HRQoL analyses were performed in treated participants aged <12 years; all participants aged <12 years who had been followed in the NIS and subsequently enrolled into group A were involved in the intraindividual analysis; results are presented for those previously treated with prophylactic BPAs. A negative binomial regression model, accounting for different follow-up times, was used to characterize bleed-related end points and compare bleed rates in the intraindividual comparison. The efficacy period was defined by the number of days between the first dose of emicizumab and the clinical cutoff date or the participant’s withdrawal from the study (whichever occurred earlier). The mean proportion of days missed of school/daycare was calculated by dividing the number of patients who missed any day at school/daycare by the number of respondents to the questionnaire.

Safety was analyzed in all participants who received ≥1 dose of emicizumab. Trough emicizumab plasma concentrations (mean and 95% confidence intervals [CI]) were calculated and presented by regimen.

Data analysis was conducted by the trial statistician and a pharmacologist (employed by the sponsor) who vouched for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses. Data were available to all authors, who confirm adherence to the protocol and the statistical analysis plan.

Results

Participant demographics

Overall, 88 male participants were enrolled (n = 68 in group A; n = 10 in group B; n = 10 in group C) with a median age of 7 years (range, 1-15 years). Eighty-five participants were aged <12 years, and 3 were aged ≥12 years. The majority of participants had severe hemophilia A (97%), had previously undergone ITI (72%), and were receiving treatment with prophylactic BPAs (75%). Thirty-four of 88 participants (39%) had target joints at baseline (Table 1). Among the 19 who participated in the NIS, 18 participants were <12 years; of those 15 were managed with prior BPA prophylaxis and 3 with prior BPA on-demand.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Demographic | Group A: emicizumab once weekly, n = 68 | Group B: emicizumab every 2 wk, n = 10 | Group C: emicizumab every 4 wk, n = 10 | Total, N = 88 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 68 (100) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 88 (100) |

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (range) | 6.0 (1-15) | 8.0 (2-10) | 9.0 (2-11) | 7.0 (1–15) |

| 0 to <2 | 8 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 8 (9.1) |

| 2 to <6 | 19 (27.9) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | 24 (27.3) |

| 6 to <12 | 38 (55.9) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (80.0) | 53 (60.2) |

| ≥12 | 3 (4.4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 39 (57.4) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (80.0) | 54 (61.4) |

| Asian | 10 (14.7) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 13 (14.8) |

| African American | 11 (16.2) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 12 (13.6) |

| Multiple | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3) |

| Unknown | 6 (8.8) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 7 (8.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (7.4) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 7 (8.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 61 (89.7) | 9 (90.0) | 9 (90.0) | 79 (89.8) |

| Not stated | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Hemophilia severity at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Mild | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3) |

| Moderate | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Severe | 65 (95.6) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 85 (96.6) |

| Previous regimen, n (%) | ||||

| Episodic | 16 (23.5) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | 22 (25.0) |

| Prophylactic | 52 (76.5) | 8 (80.0) | 6 (60.0) | 66 (75.0) |

| Median no. of bleeds in 24 wk prior to study entry (IQR) | 6 (4-9) | 5 (3-10) | 6 (3-8) | 6 (3.5-9) |

| Median time from FVIII inhibitor diagnosis (range), mo | 56.4 (0.5-142.4) | 71.4 (23.3-120.0) | 66.5 (15.0-120.0) | 58.4 (0.5-142.4) |

| Participants with target joints at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| No target joints present | 44 (64.7) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | 54 (61.4) |

| Target joints present | 24 (35.3) | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | 34 (38.6) |

| Highest historical inhibitor titer, BU/mL | ||||

| n | 66 | 10 | 10 | 86 |

| Median (IQR) | 200 (64-614) | 953 (197-1861) | 133 (29-275) | 200 (64-854) |

| Baseline FVIII inhibitor titer | ||||

| ≥5 BU/mL | 50 (73.5) | 8 (80.0) | 5 (50.0) | 63 (71.6) |

| ≥0.6 BU/mL and <5 BU/mL | 13 (19.1) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 17 (19.3) |

| <0.6 BU/mL | 4 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (4.5) |

| Previously treated with ITI, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 45 (66.2) | 10 (100) | 8 (80.0) | 63 (71.6) |

| No | 23 (33.8) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 25 (28.4) |

BU, Bethesda units; IQR, interquartile range.

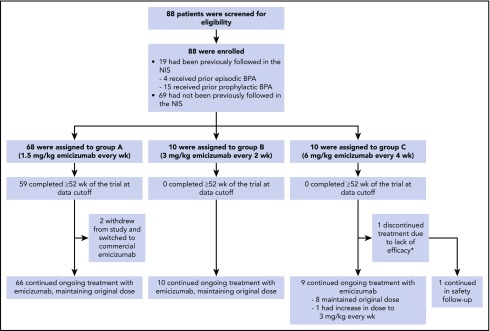

At data cutoff, 59 participants (87%) enrolled in group A had completed 52 weeks of treatment. Three participants discontinued from study treatment due to switching to commercial emicizumab (n = 2, group A) or lack of efficacy (n = 1, group C; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participant disposition. All participants received the same loading dose of emicizumab 3 mg/kg per week for 4 weeks. *Participant discontinued study treatment due to ADAs with neutralizing potential and subsequent lack of efficacy following a dose uptitration to 3 mg/kg per week (starting at week 9) and remained on study for safety follow-up.

Efficacy

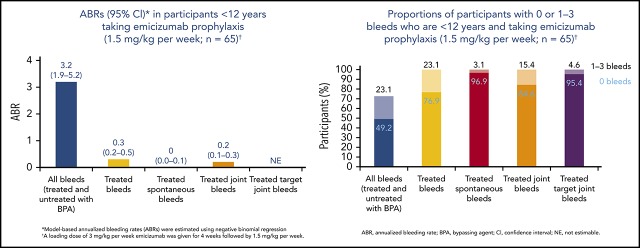

The median duration (range) of the efficacy period in participants receiving the once-weekly regimen (group A) was 57.6 weeks (17.9-92.6 weeks). In the 65 participants aged <12 years in this group, the annualized bleed rate (ABR) was 0.3 (95% CI, 0.17-0.50), and 77% of participants had zero treated bleeding events. The rates of other bleed-related end points (all bleeding events, and treated spontaneous, joint, or target joint bleeds) were low (Table 2). Overall, 22 treated bleeding episodes were reported in 15 of 65 group A participants aged <12 years, 91% of which were traumatic; the locations of these bleeds are reported in supplemental Table 1. In the subset of patients in cohort A with target joints, who had completed at least 48 weeks on study, the mean ABR in the first 24 weeks was 3.3 (95% CI, 0.7-9.2) whereas in the second 24 weeks, the mean ABR was 0 (not applicable to 3.7), suggesting that even in patients with a more severe phenotype, bleed rates continued to decrease with ongoing emicizumab treatment.

Table 2.

ABR among participants younger than 12 years of age treated with emicizumab 1.5 mg/kg per week (group A)

| Group A: emicizumab once weekly, n = 65 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bleed result | 95% CI | |

| Efficacy period | ||

| Median duration (range), wk | 57.6 (17.9-92.6) | NA |

| Bleeding events treated with BPA | ||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.3 | 0.17-0.50* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 50 (76.9) | 64.8-86.5 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 65 (100) | 94.5-100 |

| All bleeding events, regardless of treatment with BPA | ||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 3.2 | 1.94-5.22* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.6 (0.00-2.92) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 32 (49.2) | 36.6-61.9 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 47 (72.3) | 59.8-82.7 |

| Treated events of spontaneous bleeding | ||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.0 | 0.01-0.10* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 63 (96.9) | 89.3-99.6 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 65 (100) | 94.5-100 |

| Treated events of joint bleeding | ||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.2 | 0.08-0.29* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 55 (84.6) | 73.5-92.4 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 65 (100) | 94.5-100 |

| Treated events of target joint bleeding | ||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | Not estimable | Not estimable* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 62 (95.4) | 87.1-99.0 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 65 (100) | 94.5-100 |

A loading dose of 3 mg/kg emicizumab was given for 4 weeks followed by 1.5 mg/kg per week.

NA, not applicable. See Table 1 for expansion of other abbreviations.

Model-based annualized rates were estimated using negative binomial regression.

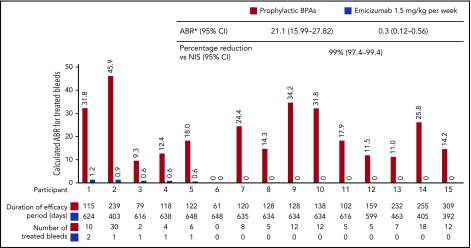

Among the 15 participants aged <12 years receiving BPA prophylaxis who had participated in the NIS, intraindividual comparisons showed a substantially lower bleeding rate with once-weekly emicizumab compared with prior standard prophylaxis, which included aPCC for 13 participants and rFVIIa for 2 (see Figure 3 for individual patient treatment duration). The ABR with emicizumab was 0.3 (95% CI, 0.12-0.56) vs 21.1 (95% CI, 15.99-27.82) with prior BPA, representing a 99% (95% CI, 97.4-99.4) reduced risk of bleeding with emicizumab (Figure 3). The median duration (range) of the efficacy period among these 15 participants was 89.1 weeks (56.0-92.6 weeks).

Figure 3.

Intraindividual treated ABR comparison in participants <12 years receiving emicizumab prophylaxis who had participated in the NIS and then enrolled in HAVEN 2 (group A). *Model-based ABRs estimated using negative binomial regression, which accounts for different follow-up times on previous treatment vs emicizumab. Comparison of ABR for treated bleeds in individual participants receiving emicizumab 1.5 mg/kg once weekly during HAVEN 2 vs BPA prophylaxis in the NIS. The efficacy periods within NIS and HAVEN 2 for individual patients are described below the x-axis. Participants exposed to emicizumab started with loading dose 3 mg/kg per week for 4 weeks followed by 1.5 mg/kg per week. Treated bleed is defined as a bleed followed by treatment of bleed. Bleeds due to surgery/procedure are excluded.

The median duration (range) of the efficacy period in participants receiving emicizumab every 2 weeks (group B) or every 4 weeks (group C) was 21.3 weeks (18.6-24.1 weeks) and 19.9 weeks (8.9-24.1 weeks), respectively. ABRs in these groups were 0.2 (95% CI, 0.03-1.72) and 2.2 (95% CI, 0.69-6.81), with 90% and 60% of participants having reported zero treated bleeding events, respectively (Table 3). The numerically higher ABR in group C was primarily driven by 2 participants; 1 participant had 6 target joint bleeds in the 24 weeks prior to enrollment, and experienced 3 target joint bleeds at the data cutoff date. The second participant developed ADAs with neutralizing potential resulting in undetectable levels of emicizumab within the first 8 weeks of treatment. No participant from groups A, B, or C reported >3 treated bleeding events during the efficacy period (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Efficacy analyses for participants younger than 12 years of age treated with emicizumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks (group B) and 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks (group C)

| Group B: emicizumab every 2 wk, n = 10 | Group C: emicizumab every 4 wk, n = 10 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleed result | 95% CI | Bleed result | 95% CI | |

| Efficacy period | ||||

| Median duration (range), wk | 21.3 (18.6-24.1) | NA | 19.9 [8.9-24.1] | NA |

| Bleeding events treated with BPA | ||||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.2 | 0.03-1.72* | 2.2 | 0.69-6.81* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA | 0.0 (0.00-3.26) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 | 6 (60.0) | 26.2-87.8 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 |

| All bleeding events, regardless of treatment with BPA | ||||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 1.5 | 0.62-3.40* | 3.8 | 1.42-10.11* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-2.81) | NA | 1.6 (0.00-4.84) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 6 (60.0) | 26.2-87.8 | 5 (50.0) | 18.7-81.3 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 |

| Treated events of spontaneous bleeding | ||||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | Not estimable | Not estimable* | 0.8 | 0.05-12.00* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 |

| Treated events of joint bleeding | ||||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.2 | 0.03-1.72* | 1.7 | 0.60-4.89* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA | 0.0 (0.00-3.26) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 | 6 (60.0) | 26.2-87.8 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 |

| Treated events of target joint bleeding | ||||

| Annualized rate of bleeding events | 0.2 | 0.03-1.72* | 0.5 | 0.05-5.88* |

| Median annualized rate of bleeding events (IQR) | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA | 0.0 (0.00-0.00) | NA |

| 0 bleeds, n (%) | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 | 9 (90.0) | 55.5-99.7 |

| 0-3 bleeds, n (%) | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 | 10 (100) | 69.2-100 |

In 23 participants receiving emicizumab prophylaxis for ≥52 weeks who had target joints at baseline, 45 of 45 target joints (100%) were resolved. Twenty of 23 participants (87%) had no target joint bleeding events while on emicizumab, including 2 participants who had 3 and 5 target joints, respectively, at baseline.

Of 43 participants who started the study with a CVAD, 21 (49%) underwent CVAD removals while on study (supplemental Figure 1). Seventeen (81%) of these procedures were performed without the administration of BPA prophylaxis; only 1 resulted in a postoperative treated bleeding event. Information on surgical procedures performed in phase 3 studies of emicizumab, including HAVEN 2, will be presented in a future report.

HRQoL

Near-maximal improvements were observed and sustained across multiple domains of the Haemo-QoL-SF and Adapted Inhib-QoL questionnaires, whose scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores reflecting better HRQoL. Clinically meaningful differences are 10 points for the score on the physical health subscale. In patients receiving emicizumab prophylaxis, the week 25 physical health domain score reflected a change from baseline of −11.3 (95% CI, −18.2, −4.37; n = 20) by the Haemo-QoL-SF and a change of −31.6 (95% CI, −36.8, −26.3; n = 58) by the Adapted Inhib-QoL. These changes in the physical health domain of both questionnaires represent near-maximal improvement from baseline in group A, with scores approaching the minimum score possible on the scales. In groups B and C, improvements were seen up to week 13 in almost all domains (supplemental Figure 2).

In group A, of the 89% of participants’ caregivers who completed the Adapted Inhib-QoL questionnaire at baseline, 28% reported that their child had not missed any days at daycare/school during the 4 weeks prior to the questionnaire completion; this increased to 61% by week 13 of emicizumab treatment.

At baseline, the mean proportion of days missed of daycare/school was 0.41 (95% CI, 0.29-0.53); following emicizumab treatment, this decreased to 0.25 (95% CI, 0.01-0.49) at week 13 and remained low at all subsequent time points.

Safety

Overall, 712 adverse events were reported in 82 of 88 participants (Table 4). The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis (33 participants [37.5%]) and local injection-site reactions (27 participants [30.7%]; supplemental Table 2); all were nonserious and resolved without treatment. No participant discontinued emicizumab due to injection-site reactions. Of the 21 serious adverse events reported, only 1 (ADAs with neutralizing potential) was assessed by the investigator as being related to emicizumab. No TE, cases of TMA, or fatalities were reported.

Table 4.

Overview of HAVEN 2 adverse events

| Emicizumab | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: once weekly, n = 68 | Group B: every 2 wk, n = 10 | Group C: every 4 wk, n = 10 | Total, N = 88 | |

| Participants with ≥1 adverse event, n (%) | 63 (96.2) | 9 (90.0) | 10 (100) | 82 (93.2) |

| Total adverse events, n | 615 | 43 | 54 | 712 |

| Participants with ≥1 adverse event, n (%) | ||||

| Adverse event with fatal outcome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious adverse event | 14 (20.6) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 17 (19.3)* |

| Adverse event leading to treatment withdrawal | 0 | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (1.1)† |

| Adverse event leading to dose modification/interruption | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade ≥3 adverse event | 11 (16.2) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 15 (17.0)‡ |

| Related adverse event | 22 (32.4) | 2 (20.0) | 6 (60.0) | 30 (34.1)§ |

| Local injection-site reaction | 19 (27.9) | 2 (20.0) | 6 (60.0) | 27 (30.7)‖ |

| Adverse events of special interest, n (%) | ||||

| Systemic hypersensitivity/anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction¶ | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Thromboembolic event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TMA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Multiple occurrences of the same adverse event in 1 individual are counted only once except for in the “Total adverse events” row, in which multiple occurrences of the same adverse event are counted separately.

Seventeen participants experienced 21 events: device-related infection (n = 2), muscle hemorrhage (n = 2), hemorrhage (n = 2), asthma (n = 2), mouth hemorrhage (n = 1), appendicitis (n = 1), bronchiolitis (n = 1), catheter site infection (n = 1), epididymitis (n = 1), clavicle fracture (n = 1), fall (n = 1), head injury (n = 1), ligament sprain (n = 1), mouth injury (n = 1), positive for ADAs with neutralizing potential (n = 1), ketoacidosis (n = 1), and headache (n = 1).

One participant withdrew from emicizumab treatment due to ADAs with neutralizing potential and subsequent lack of efficacy.

Fifteen participants experienced 19 events: asthma (n = 3), hemorrhage (n = 2), appendicitis (n = 1), catheter site infection (n = 1), device-related infection (n = 1), epididymitis (n = 1), sinusitis (n = 1), sleep apnea syndrome (n = 1), mouth hemorrhage (n = 1), chest pain (n = 1), clavicle fracture (n = 1), positivity for ADAs with neutralizing potential (n = 1), diabetes mellitus (n = 1), ketoacidosis (n = 1), pain in extremity (n = 1), and headache (n = 1).

Thirty participants experienced 67 events: injection-site reaction (n = 57), indeterminable ABO blood type (n = 3), eosinophil count increased (n = 1), positive for ADAs with neutralizing potential (n = 1), ecchymosis (n = 1), erythema (n = 1), urticaria (n = 1), nausea (n = 1), and cough (n = 1).

All but 2 of the injection-site reactions were grade 1 in intensity and resolved within 1 to 5 days without treatment. No participant discontinued due to injection-site reactions.

The numbers for systemic hypersensitivity/anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction using the Sampson criteria include all participants who experienced indicative symptoms. One participant experienced symptoms of abdominal pain and cough that were identified as a potential systemic hypersensitivity/anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction using the protocol-defined search criteria; however, medical review of the case confirmed that this was not indicative of a systemic hypersensitivity, anaphylactic, or anaphylactoid reaction.

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

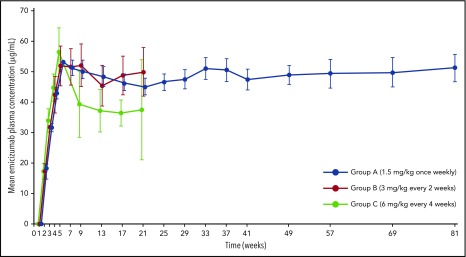

Mean trough plasma concentrations of emicizumab slightly above 50 μg/mL were observed at week 5 following 4 loading doses for all groups (Figure 4). Mean steady-state trough concentrations were maintained at effective levels across all dosing regimens until the time of analysis: ∼50, 48, and 38 μg/mL in groups A, B, and C, respectively. Emicizumab concentrations above 30 μg/mL are predicted to provide clinically meaningful control of bleeding.28 Pharmacokinetic profiles were consistent across age groups and body weights (supplemental Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

Trough plasma concentrations of emicizumab over time with administration once weekly, every 2 weeks, or every 4 weeks. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Sampling time points are indicated on the x-axis. Values are slightly offset from each other at each time point for clarity. Participants in all groups received the same loading dose of 3 mg/kg emicizumab for 4 weeks (weeks 2-5), followed by the maintenance dose indicated.

Four participants tested positive for ADAs, 2 of whom had ADAs with neutralizing potential based on pharmacokinetics, decreased reported FVIII activity, and prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). ADAs were detected at week 5 (at the end of the loading dose period) in 1 of these participants; subsequently, emicizumab plasma concentrations rapidly declined to undetectable levels within 4 weeks of ADA positivity, reported FVIII activity using a human reagent-based chromogenic assay dropped to ∼1%, and aPTT was prolonged. This participant discontinued emicizumab due to lack of efficacy. The other participant experienced a gradual decrease in emicizumab plasma concentrations to low but detectable levels; ADA positivity was detected at week 32 with a corresponding reduction in reported human reagent-based chromogenic FVIII activity, however, aPTT remained within normal values. This participant remained on study without modifying the treatment regimen and did not experience any bleeding events. Data collected after the clinical cutoff date (48 weeks after initial detection of ADAs) showed that he had become ADA-negative, with restoration of anticipated emicizumab plasma concentrations. No clear risk factors for developing ADAs were identified, though 1 patient had a history of high-titer FVIII inhibitor at time of inhibitor diagnosis. ADAs without neutralizing potential did not impact efficacy, and no ADA was associated with hypersensitivity or anaphylaxis. Further details are provided in the supplemental Results.

Discussion

In the HAVEN 2 study, once-weekly subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis resulted in a very low bleeding rate in children with hemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors, with 77% of participants having no treated bleeding events. Furthermore, 100% of all evaluable target joints resolved during the study period. Intraindividual comparison demonstrated a 99% reduction in bleeding rate with emicizumab vs BPA prophylaxis in a preceding NIS, which provided a robust standard-of-care comparator that controlled for participant-related confounders in this otherwise descriptive study.

Efficacy was maintained with less frequent emicizumab dosing; all participants experienced 3 or fewer treated bleeding events, regardless of dosing schedule received. These outcomes appear consistent with, or in fact better than, those from adolescents/adults with or without inhibitors, who received emicizumab weekly, every 2 weeks, or every 4 weeks, which likely reflects the worse joint disease on older patients.22-24 The numerically higher ABR in group C compared with groups A or B was primarily driven by 2 participants in this small sample. One participant had multiple active target joints at baseline and experienced 3 bleeding events into these joints over ∼20 weeks of emicizumab treatment (ABR of 7.9). The second participant developed ADAs with neutralizing potential following the loading period, and experienced 2 bleeding events within the first 8 weeks of treatment when emicizumab plasma concentration was near minimal (ABR of 11.8). As the ABRs in children dosed every 4 weeks were numerically higher in this small sample with a short follow-up, health care professionals may consider following patients on this regimen more closely.

One of the most frequent minor surgeries in children with hemophilia is CVAD procedures,29 either to secure access for lifesaving coagulation factor, or due to complications with the CVAD itself (eg, infection, dysfunction). By far the most common procedure that occurred on HAVEN 2 was a CVAD removal, with nearly one-half of patients who started the study with a CVAD removing it by the end. Notably, 17 of 21 CVAD removals (81%) were performed without the administration of BPA prophylaxis, and resulted in just 1 treated bleed.

HAVEN 2 represents the largest prospective bleed prevention study in pediatric persons with hemophilia A and inhibitors to date, demonstrating lower bleeding rates compared with those previously reported in this population with BPA prophylaxis14,15,30 Indeed, bleeding rates reported here are more in range of those achieved in pivotal studies of FVIII prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A without inhibitors (supplemental Table 3). Notably, this is the first report of a treatment resolving target joints in an inhibitor population, which until now has only been reported when using FVIII products in patients without inhibitors.31,32 These findings translated into improvements in participants’ HRQoL, particularly in the physical health domain scores. Young children stand to benefit most, as they are less likely to have developed permanent joint damage compared with adolescents or adults; preventing bleeding or resolving target joints may yield lifelong benefit by maintaining joint health until adulthood.

Emicizumab had a favorable safety profile in children, with no TE or TMA events. This may be related to low bleed rate and low concomitant aPCC exposure (use of concomitant aPCC treatment was low, with only 2 patients treated with a single dose of <50 U/kg each).23 As expected for a humanized monoclonal antibody, ADAs were observed; the frequency was low and consistent with rates observed across 3 other HAVEN studies.33 Both participants who reported ADAs with neutralizing potential exhibited distinctive clinical courses, 1 experiencing loss of efficacy, and the other spontaneous resolution of ADA with recovery of expected pharmacokinetic exposure. Importantly, ADAs without neutralizing potential were not associated with higher bleeding rates, and the safety profile in participants testing positive for ADAs was similar to those without ADAs.

Effective trough concentrations of emicizumab were sustained with all maintenance regimens throughout the study, consistent across a wide range of ages and body weights. Slightly lower trough concentrations with maintenance dosing every 4 weeks were as expected based on pharmacokinetic simulations,34 and efficacy was comparable with adolescent/adult participants as predicted by pharmacokinetic-efficacy simulations.34,35 Following the approved prescribing information (eg, regarding a strict weight-based dosing regimen) is recommended for clinical practice.

Limitations of this study are characteristic of pediatric hemophilia trials, which are often descriptive in nature and constrained by recruitment challenges. The later addition of groups B and C resulted in smaller numbers and shorter follow-up in those groups, although overall this study enrolled a relatively large number of participants worldwide, representative of pediatric inhibitor patients reported in prior studies.15,30 Furthermore, additional studies are under way or are required to characterize the use of emicizumab in pediatric patients <1 year of age, including previously untreated patients, as well as those on ITI therapy. In conclusion, emicizumab prophylaxis is well tolerated, and can prevent or substantially reduce bleeds in children with hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors. Clinically meaningful efficacy and pharmacokinetic results were achieved with all 3 dosing regimens assessed, suggesting the potential for reduced treatment burden. Despite a rapidly evolving treatment landscape in hemophilia, children have been largely excluded from recent trials of novel agents; thus, emicizumab stands to become the next-generation standard of care for pediatric persons with hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Maria Alfaradhi and Rebecca A. Bachmann of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications. Sylvia Von Mackensen is the developer of the Haemo-QoL-SF and Adapted Inhib-QoL questionnaires.

This work was supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. Editorial assistance was funded by F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd.

Footnotes

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level data through the clinical study data request platform (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com). Further details on Roche’s criteria for eligible studies are available here (https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/study-sponsors/study-sponsors-roche.aspx). For further details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: G.Y., T.C., J.O., J.M., R.K.-J., M.U., C.S., G.G.L., and M.S. contributed to the study design; G.Y., R.L., R.S., J.O., V.J.-Y., J.M., R.K.-J., M.W., M.S., and M.E.M. collected data for the study; G.Y., R.L., T.C., R.S., V.J.-Y., M.U., M.Y.D., L.Y.W., C.S., G.G.L., and M.E.M. participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript, approved the final version, and support this publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.Y. has received honoraria and consulting fees from Alnylam, Bayer, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Genentech/Roche, Grifols, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk, Shire, Spark, and uniQure, and an investigator-initiated grant award from Genentech. R.L. has consulted for CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Octapharma, Sobi/Biogen, Baxalta/Shire, Grifols, and Bayer. T.C. and L.Y.W. are employed by Genentech. R.S. has consulted for Bayer, Pfizer, UniQure, BioMarin, Novo Nordisk, Shire, Genentech/Roche, Spark, Octapharma, Grifols, Kedrion, and Bioverativ, and has investigator-initiated grant funding from Bioverativ, Kedrion/Grifols, Genentech, and Octapharma. J.O. has received honoraria and consulting fees from Chugai, CSL Behring, Grifols, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Roche, Sobi, and Shire, and grants from CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, and Shire. V.J-Y. has received grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Shire, Bayer, Pfizer, Grifols, Sobi, and Octapharma, and personal fees from CSL Behring and Roche. J.M. has received research grant support from Bayer, Biogen, Biomarin, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Sobi, Roche, and uniQure; personal fees from Amgen, Bayer, Biotest, Biogen, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Catalyst Biosciences, Chugai, Freeline, LFB, Novo Nordisk, Roche, and Spark; and has been a member of a speaker’s bureau for Alnylam, Bayer, Biotest, Biogen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sobi, Shire, Roche, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the World Federation of Hemophilia. R.K.-J. has consulted for CSL Behring, Genentech/Roche, Grifols, and Pfizer, and has received research funding from CSL Behring, Genentech/Roche, and Pfizer. M.W. has consulted for Bayer Healthcare, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Roche/Genentech, and HEMA Biologics. M.U. is employed by Roche. M.Y.D. and C.S. are employed by and hold stock with Roche. G.G.L. is employed by Genentech and holds stock with Roche. M.S. has received grants and personal fees from Shire, Bioverativ, Chugai, Novo Nordisk, and Bayer; grants from Roche, CSL Behring, and Pfizer; and personal fees from Sysmex. M.E.M. has received personal fees from Bayer, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Octapharma, Pfizer, Sobi/Biogen, Bioverativ, Baxalta/Shire, Biotest, and Grifols.

Correspondence: Guy Young, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Mail Stop 54, Los Angeles, CA 90027; e-mail: gyoung@chla.usc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. ; Treatment Guidelines Working Group on Behalf of The World Federation Of Hemophilia . Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19(1):e1-e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astermark J, Petrini P, Tengborn L, Schulman S, Ljung R, Berntorp E. Primary prophylaxis in severe haemophilia should be started at an early age but can be individualized. Br J Haematol. 1999;105(4):1109-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer K, Collins PW, Ozelo MC, Srivastava A, Young G, Blanchette VS. When and how to start prophylaxis in boys with severe hemophilia without inhibitors: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(5):1105-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valentino LA, Mamonov V, Hellmann A, et al. ; Prophylaxis Study Group . A randomized comparison of two prophylaxis regimens and a paired comparison of on-demand and prophylaxis treatments in hemophilia A management. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(3):359-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren BB, Thornhill D, Stein J, et al. Early prophylaxis provides continued joint protection in severe hemophilia A: results of the Joint Outcome Continuation Study [abstract]. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):382. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):535-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Angiolella LS, Cortesi PA, Rocino A, et al. The socioeconomic burden of patients affected by hemophilia with inhibitors. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(4):435-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh CE, Soucie JM, Miller CH; United States Hemophilia Treatment Center Network . Impact of inhibitors on hemophilia A mortality in the United States. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(5):400-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvez T, Chambost H, Claeyssens-Donadel S, et al. ; FranceCoag Network . Recombinant factor VIII products and inhibitor development in previously untreated boys with severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2014;124(23):3398-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouw SC, van der Bom JG, Ljung R, et al. ; PedNet and RODIN Study Group . Factor VIII products and inhibitor development in severe hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):231-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouw SC, van der Bom JG, Marijke van den Berg H. Treatment-related risk factors of inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with hemophilia A: the CANAL cohort study. Blood. 2007;109(11):4648-4654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antunes SV, Tangada S, Stasyshyn O, et al. Randomized comparison of prophylaxis and on-demand regimens with FEIBA NF in the treatment of haemophilia A and B with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):65-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay CR, DiMichele DM; International Immune Tolerance Study . The principal results of the International Immune Tolerance Study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood. 2012;119(6):1335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konkle BA, Ebbesen LS, Erhardtsen E, et al. Randomized, prospective clinical trial of recombinant factor VIIa for secondary prophylaxis in hemophilia patients with inhibitors. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(9):1904-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leissinger C, Gringeri A, Antmen B, et al. Anti-inhibitor coagulant complex prophylaxis in hemophilia with inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1684-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santagostino E, Morfini M, Auerswald GK, et al. Paediatric haemophilia with inhibitors: existing management options, treatment gaps and unmet needs. Haemophilia. 2009;15(5):983-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valentino LA, Ewenstein B, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Central venous access devices in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2004;10(2):134-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Dijk K, Van Der Bom JG, Bax KN, Van Der Zee DC, Van Den Berg MH. Use of implantable venous access devices in children with severe hemophilia: benefits and burden. Haematologica. 2004;89(2):189-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genentech, Inc Emicizumab. Prescribing information. 2017. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/hemlibra_prescribing.pdf. Accessed 4 September 2019.

- 20.Kitazawa T, Igawa T, Sampei Z, et al. A bispecific antibody to factors IXa and X restores factor VIII hemostatic activity in a hemophilia A model. Nat Med. 2012;18(10):1570-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roche Emicizumab. Summary of product characteristics (SmPC). 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/hemlibra-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 4 September 2019.

- 22.Mahlangu J, Oldenburg J, Paz-Priel I, et al. Emicizumab prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A without inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(9):811-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldenburg J, Mahlangu JN, Kim B, et al. Emicizumab prophylaxis in hemophilia A with inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):809-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pipe SW, Shima M, Lehle M, et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of emicizumab prophylaxis given every 4 weeks in people with haemophilia A (HAVEN 4): a multicentre, open-label, non-randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(6):e295-e305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollak E, Mühlan H, Von Mackensen S, Bullinger M; HAEMO-QOL GROUP . The Haemo-QoL Index: developing a short measure for health-related quality of life assessment in children and adolescents with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2006;12(4):384-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Mackensen S, Riva S, Khair K, et al. Development of an inhibitor-specific questionnaire for the assessment of health-related quality of life in haemophilia patients with inhibitors (INHIB-QoL) [abstract]. Value Health. 2013;16(3):A196. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchette VS, Key NS, Ljung LR, Manco-Johnson MJ, van den Berg HM, Srivastava A; Subcommittee on Factor VIII, Factor IX and Rare Coagulation Disorders of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis . Definitions in hemophilia: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(11):1935-1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson F, Schmitt C, Petry C, Mercier F, Frey N, Retout S. Exposure-response modeling of emicizumab for the prophylaxis of bleeding in haemophilia A patients with and without inhibitors against factor VIII [abstract]. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(suppl 1). Abstract PB0325. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ljung RC, Knobe K. How to manage invasive procedures in children with haemophilia. Br J Haematol. 2012;157(5):519-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young G, Auerswald G, Jimenez-Yuste V, et al. PRO-PACT: retrospective observational study on the prophylactic use of recombinant factor VIIa in hemophilia patients with inhibitors. Thromb Res. 2012;130(6):864-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oldenburg J, Kulkarni R, Srivastava A, et al. Improved joint health in subjects with severe haemophilia A treated prophylactically with recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein. Haemophilia. 2018;24(1):77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro AD, Srivastava A, Ragni MV, et al. Clinical outcomes of weekly prophylaxis with rFVIIIFc: longitudinal analysis of the A-LONG and ASPIRE study population [abstract]. Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1):2368. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paz-Priel I, Chang T, Asikanius E, et al. Immunogenicity of emicizumab in people with hemophilia A (PwHA): results from the HAVEN 1-4 studies [abstract]. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):633. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoneyama K, Schmitt C, Kotani N, et al. A pharmacometric approach to substitute for a conventional dose-finding study in rare diseases: example of phase III dose selection for emicizumab in hemophilia A. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(9):1123-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoneyama AK, Schmitt C, Chang T, Levy GG. Model-informed dose selection for pediatric study of emicizumab in hemophilia [abstract]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(suppl 1):S94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.