Abstract

Background

Distributions of serum pepsinogen (PG) values were assessed in Helicobacter pylori-infected and non-infected junior high school students (aged 12–15 years) in Japan.

Methods

All junior high school students (1,225 in total) in Sasayama city, who were basically healthy, were asked to provide urine and serum samples, which were used to measure urine and serum H. pylori antibodies using ELISA kits and PG values. The subjects, whose urine and serum antibodies were both positive, were considered H. pylori infected.

Results

Of the 187 subjects who provided urine and blood samples, 8 were infected, 4 had discrepant results, 4 had negative serum antibody titers no less than 3.0 U/ml, and 171 were non-infected. In the H. pylori non-infected subjects, the median PG I and PG II values and PG I to PG II ratio (PG I/II) were 40.8 ng/mL, 9.5 ng/mL, and 4.4, respectively, whereas in the infected subjects, these values were 55.4 ng/mL, 17.0 ng/mL, and 3.3, respectively (each P < 0.01). In the non-infected subjects, PG I and PG II were significantly higher in males than in females (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

The PG I and PG II values were higher, and the PG I/II was lower in H. pylori infected students than in non-infected students. In H. pylori non-infected students, males showed higher PG I and PG II values than females. The distributions of PG values in junior high school students differed from those in adults.

Key words: students, urine antibody, serum antibody, serum pepsinogen

INTRODUCTION

Pepsinogen is a precursor of pepsin, and human gastric mucosa cells produce two immunochemically distinct forms of PG.1 PG I is secreted by the chief and mucus neck cells in the gastric fundic glands, and PG II is produced by these cells and by the cardiac, pyloric, and Brunner’s glands in the gastric cardia and antrum and proximal duodenum.2 PG reflects gastric mucosal atrophy and inflammation, both of which Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection provokes. Inflammation upregulates production of both PG I and PG II in gastric mucosal cells and increases the amount discharged to serum, where elevation of PG II is usually larger so that the PG I/II ratio declines. With the progression of atrophy, numbers of gastric mucosal cells producing PG I and PG II decease. As the decrease of cells producing PG I is more crucial, the PG I/II ratio declines with the progression of atrophy.3–6 In adults, PG values were used as a marker of gastric mucosal atrophy that is strongly related to gastric cancer risk.7–9 Recently, criteria of PG values to distinguish subjects with and without H. pylori infection have been proposed because PG values differ depending on the infection among adult subjects.10 Adults with H. pylori infection showed elevated PG I and PG II values and reduced PG I to PG II ratios.11

H. pylori infection causes lesions in most infected high school students (aged 15–18 years), including nodular/atrophic gastritis and duodenal erosion/ulcer,12 and a subset of infected subjects develop gastric cancer in the future.13,14

In a previous study with 454 asymptomatic junior high school students aged 12–15 years in Japan15 and another study analyzing sera from 300 asymptomatic Japanese children less than 15 years old,16 serum H. pylori antibody-positive children showed elevated PG I and PG II, and reduced PG I/II compared with the seronegative children. Thus, PG values can be used to diagnose H. pylori infection status in junior high school students, who are usually aged 12–15 years.

Nonetheless, it is still unclear whether distributions of PG values in junior high school students are similar to ones in adults with reference to H. pylori infection status. The previous studies did not focused on these points. The aim of this study was to assess the distributions of PG values in H. pylori infected and non-infected junior high school students in Japan.

METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Hyogo College of Medicine.

Subjects and collection of samples

The sample collection was conducted in Sasayama city, which is approximately 60 km north-north-west of Osaka. The population of Sasayama city is approximately 42,000, and the economy relies on agriculture and tourism. In 2012, all 1,225 students attending any of the 6 junior high schools in Sasayama city were invited to participate in the present study. They were healthy students aged 12–15 years and were asked to provide urine and serum samples. The invitation was distributed through the schools. Collection of the samples was performed in several community centers after school or on holidays. The participants went there with their parent or guardian, who were informed of the study and gave the written consent. Urine and blood samples were assayed using H. pylori IgG antibody kits. In addition, PG I and PG II levels were measured in the serum samples. The results of the tests were sent to the parents or guardians via the postal system.

Evaluation of H. pylori IgG antibodies (antibody tests) and PG I and II

For the urine antibody tests, single-void urine samples were obtained. Urinary IgG antibodies to H. pylori were determined using a urine-HpELISA kit (URINELISA, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Cut-off index (CI) values (urine antibody titer) ≥1.0 were considered positive for H. pylori, and those <1.0 were considered negative. Previous studies showed that the cutoff value gave 91.9% sensitivity and 91.6% specificity,17 or a 97.6% sensitivity and a 96.5% specificity18 for junior high school students.

For the serum antibody tests, serum H. pylori IgG antibody was quantified using a serum-HpELISA kit (E-plate EIKEN H. pylori, Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). According to the manufacturer’s instruction, serum antibody titers ≥10.0 U/mL and titers <10.0 U/mL were classified as positive and negative for H. pylori, respectively. The cutoff value gave 91.2% sensitivity and 97.4% specificity for children aged 0–17 years.19 Recently, it has been demonstrated that many subjects with current or past infection have serum antibody titers ≥3.0 U/mL and <10.0 U/mL.20 Subjects with such serum antibody titers (negative with relatively high titers) were separated from other subjects whose serum antibody titers were <3.0 U/mL (negative with relatively low titers) and were not included in the H. pylori non-infected subjects.

Quantification of PG I and II levels was conducted using the CLIA method (Architect Pepsinogen I, II; Abbott Japan Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Levels of PG I and PG II and the ratio of PG I to PG II were evaluated between positive and negative serum antibody tests. In the non-infected subjects, effect of age (among three school years aged 12–13, 13–14, and 14–15 years) and gender was evaluated.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were preformed using R version 3.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Differences of PG values were tested using the non-parametric method: the Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons of two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis Chi-squared for comparisons of three groups.

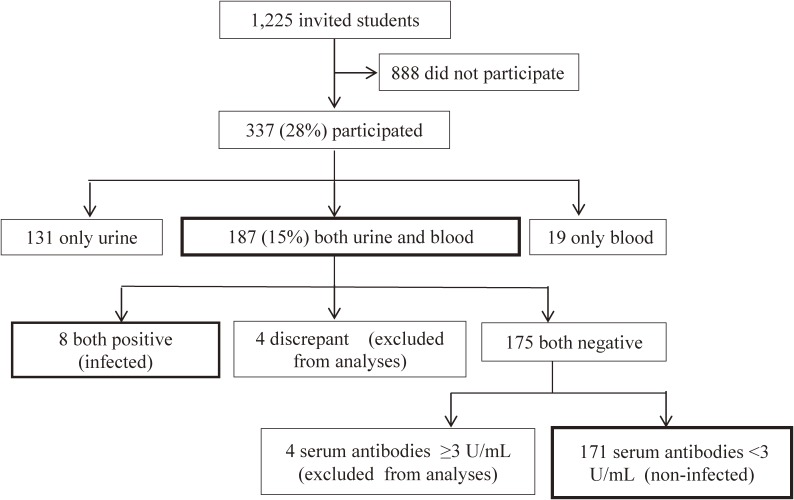

RESULTS

In this study, 337 (28% of those invited) participated, of whom 131, 187, and 19 provided only urine, urine and blood, and only blood samples, respectively (Figure 1). In the 187 students with both urine and serum antibody tests, the concordance rate was 97.9% and kappa coefficient was 0.789 (Table 1). Four students showed discrepant results between urine and serum antibody tests (Table 1 and Table 2). Three students had negative urine antibody tests but positive serum antibody tests, and the other student was urine positive but serum negative. Of the 175 subjects with negative results for both tests, four showed serum antibody titers of ≥3.0 U/mL (negative with relatively high titers). These four subjects and the four subjects who gave discrepant results of urine and serum antibody tests were excluded from further analyses. The eight subjects with positive results for both tests and the 171 subjects with negative results for both tests (Figure 1) were considered H. pylori infected and non-infected, respectively.

Figure 1. A flow chart for the selection of study subjects.

Table 1. Association of urine and serum antibody tests.

| Serum antibody test | Total | ||||

| Positive | Negative high titer | Negative low titer | |||

| (≥10.0 U/mL) | (<10.0 U/mL and ≥3.0 U/mL) | (<3.0 U/mL) | |||

| Urine antibody test | Positive | 8a | 0 | 1b | 9 |

| Negative | 3b | 4b | 171c | 178 | |

| Total | 11 | 4 | 172 | 187 | |

aConsidered positive for H. pylori infection.

bThese subjects were excluded from further analyses.

cConsidered negative for H. pylori infection.

Table 2. Lists of subjects with serum antibody titers between 3.0 and 10.0 U/mL, with discrepant results of urine and serum antibody tests, and with positive results for both tests.

| Subjects | Gender | Urine Ab CI value |

Urine Ab test | Serum Ab EV value |

Serum Ab test | PG I (ng/mL) |

PG II (ng/mL) |

PG I to PG II ratio |

| Subjects with serum antibody titers <10.0 U/mL and ≥3.0 U/mL |

F | 0.06 | − | 3 | − | 60.2 | 10.4 | 5.8 |

| M | 0.10 | − | 3 | − | 42.7 | 9.9 | 4.3 | |

| M | 0.05 | − | 3 | − | 48.5 | 9.9 | 4.9 | |

| M | 0.18 | − | 4 | − | 45.6 | 8.4 | 5.4 | |

| Subjects with discrepant results of urine and serum antibody tests |

F | 0.07 | − | 16 | + | 26 | 5.2 | 5.0 |

| F | 0.05 | − | 11 | + | 160 | 71.9 | 2.2 | |

| F | 0.04 | − | 13 | + | 18.8 | 5.3 | 3.5 | |

| M | 1.36 | + | <3 | − | 38.2 | 12.7 | 3.0 | |

| Subjects with positive results for both urine and serum antibody tests (Assumed as H. pylori infected) |

M | 10.08 | + | 67 | + | 38.1 | 11.4 | 3.3 |

| F | 9.78 | + | 63 | + | 46.3 | 13.1 | 3.5 | |

| F | 1.20 | + | 24 | + | 99.9 | 46.0 | 2.2 | |

| M | 2.82 | + | 19 | + | 49.3 | 14.8 | 3.3 | |

| M | 2.51 | + | 36 | + | 62.2 | 19.2 | 3.2 | |

| F | 10.59 | + | 78 | + | 63.6 | 33.9 | 1.9 | |

| M | 9.73 | + | ≥100 | + | 61.5 | 30.2 | 2.0 | |

| F | 8.14 | + | 57 | + | 44.9 | 13.5 | 3.3 | |

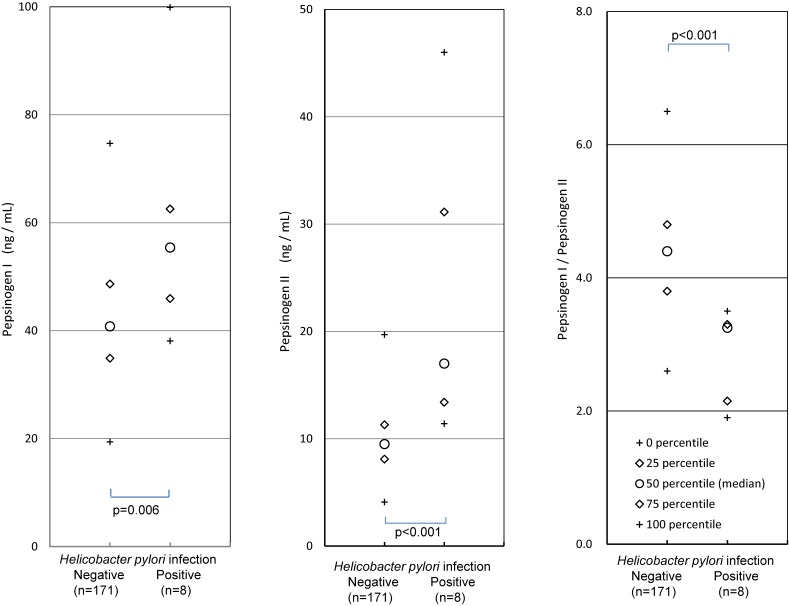

In the H. pylori non-infected subjects, the medians of PG I, PG II, and the PG I/II ratio were 40.8 ng/mL, 9.5 ng/mL, and 4.4, respectively, whereas in the infected subjects, these values were 55.4 ng/mL, 17.0 ng/mL, and 3.3, respectively (P-values all <0.01; Figure 2). Percentiles of PG values in H. pylori non-infected subjects are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2. Comparison of PG values between H. pylori infected and non-infected subjects.

Table 3. Pepsinogen values in H. pylori non-infected 171 junior high school students.

| Percentile | |||||

| 0% | 25% | Median | 75% | 100% | |

| PG I (ng/mL) | 19.4 | 34.9 | 40.8 | 48.7 | 74.7 |

| PG II (ng/mL) | 4.1 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 11.3 | 19.7 |

| PG I to II ratio | 2.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 6.5 |

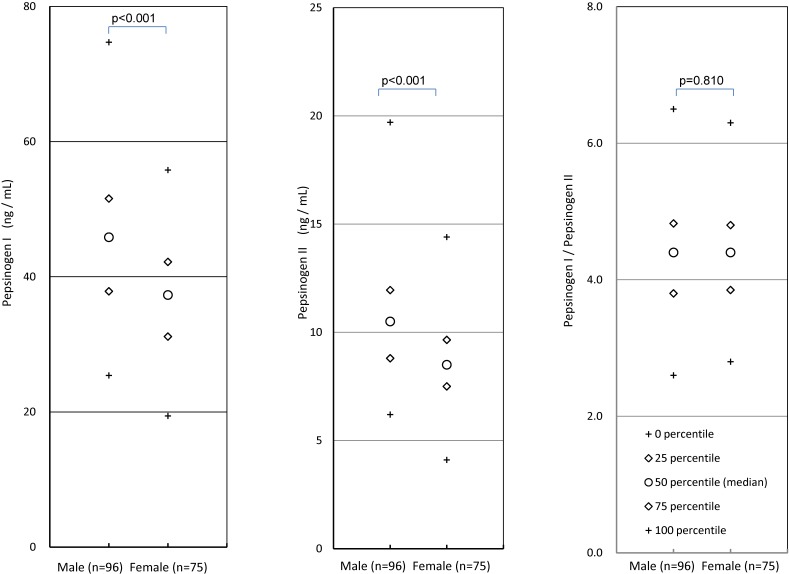

In the H. pylori non-infected subjects, school year (age) did not affect PG I, PG II, or the PG I/II ratio (data not shown), with P-values of 0.57, 0.08, and 0.11, respectively. The males showed higher PG I and PG II values than the females, whereas no gender difference was observed regarding the PG I/II ratio (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of PG values between males and females in H. pylori non-infected subjects.

To evaluate the effect of excluding the eight subjects, sensitivity analyses were performed, where the four subjects with discrepant results between urine and serum tests were considered infection positive and the four subjects with serum antibody titers 3 or 4 U/mL (negative with relatively high titers) were considered infection negative. When these eight subjects were added, the medians of PG I, PG II, and the PG I/II ratio were 41.0 ng/mL, 9.5 ng/mL, and 4.4, respectively, in the H. pylori infected negative subjects, whereas in the infected subjects, these values were 47.8 ng/mL, 14.2 g/mL, and 3.4, respectively. Inclusion of the eight subjects slightly affected PG I and PG II in the H. pylori infected subjects.

DISCUSSION

Eight junior high school students with positive results for both the urine and serum antibody tests were considered H. pylori infected, and 171 students with negative urine antibody results and serum antibody titers of <3.0 U/mL were considered non-infected. In the H. pylori non-infected subjects, the medians of PG I, PG II, and the PG I/II ratio were 40.8 ng/mL, 9.5 ng/mL, and 4.4, respectively, whereas in the infected subjects, these values were 55.4 ng/mL, 17.0 ng/mL, and 3.3, respectively (each P < 0.01; Figure 2). In the previous studies with asymptomatic Japanese children,15,16 the elevated PG I and PG II levels and the decreased PG I/II ratio in H. pylori infected subjects were consistent with the present study. In asymptomatic children aged 0–4 years in Chile, similar results were obtained, while the PG I/II ratio was elevated in the H. pylori seropositive children aged 5–9 years.21 In symptomatic children abroad, PG I and II were elevated and the PG I/II ratio was decreased in H. pylori seropositive children,22,23 although a few exceptional results were reported, where PG I was not affected24,25 or the PG I/II ratio was not affected.26 The elevated PG I and PG II and decreased PG I/II ratio in H. pylori infected children seem to be consistent, although several exceptions exist. The change in PG values in the infected children were similar to those of adult subjects without severe mucosal atrophy.4,5

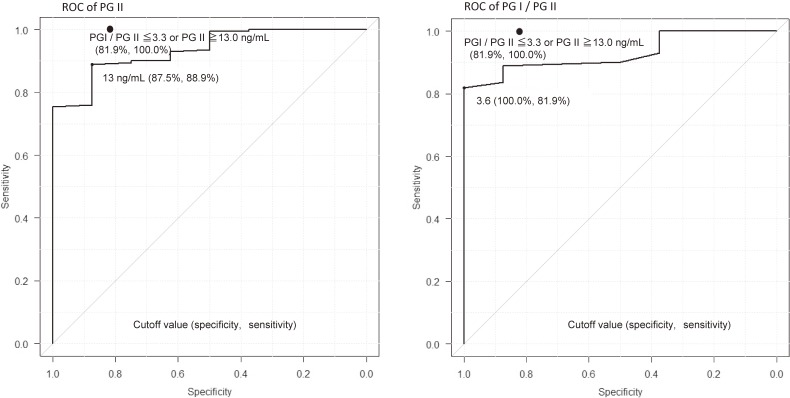

PG I and PG II values can be affected by the kits that are used and the different criteria are proposed.10,27 One study that used the same kit as the present study reported a 96.3% sensitivity and 82.8% specificity in adult subjects when a PG II value of ≥10 ng/mL or a PG I/II ratio of ≤5.0 were considered positive for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection.10 Under that criterion, the eight H. pylori infected children who were diagnosed as positive in our study were considered positive, indicating 100% sensitivity, whereas 146 of the 171 non-infected children were diagnosed as positive, indicating 14.6% specificity (data not shown). These criteria for adult subjects are not appropriate for young subjects. Nonetheless, 100% sensitivity and 81.9% specificity are obtained when PG II values of ≥13 ng/mL or PG I/II ratios of ≤3.3 are used to determine H. pylori infection status (Figure 4), which was obtained as below. ROC of PG II indicates 13 ng/mL was the optimal cutoff value, which an infected subject did not satisfy. If the condition that the PG I/PG II ratio was ≤3.3 was added, 100% sensitivity was obtained whereas specificity decreases from 88% to 82%. Thus, PG values can be a good marker for H. pylori infection in junior high school students and can be used with a serum antibody test as another marker of the infection to improve the diagnostic accuracy. Nonetheless, the optimal criteria may differ from those for adults. Further study is necessary to determine the optimal criteria for practical use in junior high school students. There are gender differences regarding PG I and PG II, but not in the PG I/II ratio. The gender differences of the medians were 8.6 ng/mL for PG I and 2.0 ng/mL for PG II, whereas they were 5.4 and 0.2 ng/mL in adult subjects, respectively.10 Clear gender differences in PG I and PG II values may exist among junior high students, which should be considered when optimal criteria of PG values for H. pylori infection are determined.

Figure 4. ROC (receiver operating characteristics) curves of PG II and PG I/PG II for H. pylori infection. The optimal criterion using both PG II and PG I/PG II is shown as closed circle (for more details see text).

There are several limitations in the present study. First, the sample size of H. pylori positive subjects was very small because of the low H. pylori prevalence in this age group in Japan. The small sample size might make the results unstable. The results of the present study regarding H. pylori positive subjects were consistent with other studies.15,16 The effect of H. pylori infection on PG values may be typical, and the small sample size may not have a large effect. Second, the participation rate was low. The collection of blood samples can cause pain, which may be a hurdle preventing the subjects from participating. Most subjects or their guardians did not know the H. pylori infection status or PG values of the subjects when they decided to participate. Therefore, the low participation rate may not affect the difference in distributions of PG values between H. pylori non-infected and infected subjects, between genders, or between students and adults observed in the present study. However, it may provoke a little bias on H. pylori prevalence because family history of H. pylori infection and the related disease may be a motive for the participation and intra-familial infection is thought to be the main infection route in Japan.28 The local government performed a H. pylori urine antibody screening program in 2014 for junior high school students aged 12–13 years in the area, which 355 (97%) of 366 invited students attended. The urine antibody prevalence was 5.4% and prevalence considering the results of urea breath test was 2.8–4.2% (unpublished data), which are not so different from the observed prevalence 4.5%, suggesting that selection bias may be small. Third, the students were evaluated using only urine and serum tests to identify whether a subject is H. pylori infected. Some reports have suggested that the antibody test is inaccurate for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection in children,29,30 but the both serum and urine antibody kits showed a good diagnostic accuracy.17–19 On the other hand, a strength of the present study is that both urine and serum antibody tests were performed for H. pylori infection diagnosis. We excluded four subjects with discrepant results and four subjects with negative high titers of serum antibody (Table 1). The exclusion decreased subjects with possible misdiagnoses and consequently may have elevated the accuracy of diagnosis.

In conclusion, PG I and PG II values were higher and the PG I/II ratio was lower in H. pylori infected junior high school students compared to non-infected students. In H. pylori non-infected students, males showed higher PG I and PG II values than females. The distributions of PG values differed from those in adults, and separate criteria must be determined for practical use in junior high school students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express sincere gratitude to the participants and their guardians, and also to the staffs of the schools and the city government for their great help to collect the samples.

This project was supported by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant (Research for Promotion of Cancer Control H26-political-general-019) and a JPSP Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (C), Grant number JP22590614.

Conflicts of interest: Kato M received scholarship grants from Abott Japan Co., Ltd. Okuda M received lecture fee from Otsuka Pharmacy Co. Ltd. The other authors declare none of them have conflict of interest regarding the present study. The authors alone are responsible for the content of the paper.

Author contribution: Okuda M, Kikuchi S, Mabe K and Kato M designed the study; Okuda M and Kikuchi S collected the data and gave explanations to the subjects; Kikuchi S, Okuda M, Miyamoto R and, Lin Y analyzed the data; and Okuda M, Kikuchi S, Okumura A, Osaki T and Kamiya S wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samloff IM. Cellular localization of group I pepsinogens in human gastric mucosa by immunofluorescence. Gastroenterology. 1971;61:185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotter JI, Wong FL, Samloff IM, et al. Evidence for a major dominance component in the variation of serum pepsinogen I levels. Am J Hum Genet. 1982;34:395–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miki K, Ichinose M, Shimizu A, et al. Serum pepsinogens as a screening test of extensive chronic gastritis. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1987;22:133–141. 10.1007/BF02774209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi S, Kurosawa M, Sakiyama T, et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on serum pepsinogens. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:471–476. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00969.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuta T, Kaneko E, Baba S, Arai H, Futami H. Percentage changes in serum pepsinogens are useful as indices of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue K, Fujisawa T, Haruma K. Assessment of degree of health of the stomach by concomitant measurement of serum pepsinogen and serum Helicobacter pylori antibodies. Int J Biol Markers. 2010;25:207–212. 10.5301/JBM.2010.6087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikuchi S, Wada O, Miki K, et al. Serum pepsinogen as a new marker for gastric carcinoma among young adults. Research Group on Prevention of Gastric Carcinoma among Young Adults. Cancer. 1994;73:2695–2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Yamaki G, Miki K, et al. Meta-analysis on the validity of pepsinogen test for gastric carcinoma, dysplasia or chronic atrophic gastritis screening. J Med Screen. 2004;11:141–147. 10.1258/0969141041732184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miki K, Ichinose M, Ishikawa KB, et al. Clinical application of serum pepsinogen I and II levels for mass screening to detect gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993;84:1086–1090. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02805.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikuchi S, Kato M, Mabe K, et al. Optimal criteria and diagnostic ability of serum pepsinogen values for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Epidemiol. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20170094 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.2188/jea.JE20170094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner S, Haruma K, Gladziwa U, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum pepsinogen A, pepsinogen C, and gastrin in gastritis and peptic ulcer: significance of inflammation and effect of bacterial eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1211–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akamatsu T, Ichikawa S, Okudaira S, et al. Introduction of an examination and treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in high school health screening. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1353–1360. 10.1007/s00535-011-0450-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi S, Wada O, Nakajima T, et al. Prevention of gastric carcinoma among young adults: serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and gastric cancer among young adults. Cancer. 1995;75:2789–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikuchi S, Nakajima T, Kobayashi O, et al. Effect of age on the relationship between gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:774–779. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01012.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakayama Y, Lin Y, Hongo M, Hidaka H, Kikuchi S. Helicobacter pylori infection and its related factors in junior high school students in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12363. 10.1111/hel.12363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuda Y, Isomoto H, Ohnita K, et al. Impact of CagA status on serum gastrin and pepsinogen I and II concentrations in Japanese children with Helicobacter pylori Infection. J Int Med Res. 2003;31:247–252. 10.1177/147323000303100401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuda M, Kamiya S, Booka M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine-based kits for detection of Helicobacter pylori antibody in children. Pediatr Int. 2013;55:337–341. 10.1111/ped.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mabe K, Kikuchi S, Okuda M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine Helicobacter pylori antibody test in junior and senior high school students in Japan. Helicobacter. 2017;22. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hel.12329. 10.1111/hel.12329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueda J, Okuda M, Nishiyama T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serum antibody kit (E-plate) in the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japanese children. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:47–51. 10.2188/jea.JE20130078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikuchi S. Background of and process to “Warning from Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research on positive or negative decision by serum Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody tests (Dec. the 25th, 2014)”. Jpn J Helico Res. 2015;17:21–24 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhsen K, Lagos R, Reymann MK, Graham DY, Pasetti MF, Levine MM. Age-dependent association among Helicobacter pylori infection, serum pepsinogen levels and immune response of children to live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83999. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guariso G, Basso D, Bortoluzzi CF, et al. Gastro Panel: evaluation of the usefulness in the diagnosis of gastro-duodenal mucosal alterations in children. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;402:54–60. 10.1016/j.cca.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalach N, Legoedec J, Wann AR, Bergeret M, Dupont C, Raymond J. Serum levels of pepsinogen I, pepsinogen II, and gastrin-17 in the course of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in pediatrics (Letter to Editor). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:568–569. 10.1097/00005176-200411000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Angelis GL, Cavallaro LG, Maffini V, et al. Usefulness of a serological panel test in the assessment of gastritis in symptomatic children. Dig Dis. 2007;25:206–213. 10.1159/000103886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koilvusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Kolho KL. Is GastroPanel serum assay useful in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated gastritis in children? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:35–38. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes AI, Palha A, Lopes T, et al. Relationship among serum pepsinogens, serum gastrin, gastric mucosal histology and H-pylori virulence factors in a paediatric population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:524–531. 10.1080/00365520500337098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitamura Y, Yoshihara M, Ito M, et al. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis by serum pepsinogen levels. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1473–1477. 10.1111/jgh.12987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuda M, Osaki T, Lin Y, et al. Low prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a population-based study in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:133–138. 10.1111/hel.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khanna B, Cutler A, Israel NR, et al. Use caution with serologic testing for Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:460–465. 10.1086/515634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunnerstam B, Kjerstadius T, Jansson L, et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in a pediatric patient population: comparison of three commercially available serological tests and one in-house enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3328–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]