Abstract

Drug resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is currently a clinical problem in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Homoharringtonine (HHT) is an approved treatment for adult patients with chronic- or accelerated-phase CML who are resistant to TKIs and other therapies; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In the present study, HHT treatment demonstrated induction of apoptosis in imatinib-resistant K562G cells by using MTS assay and western blotting, and BCR-ABL protein was reduced. CHX chase assay revealed that HHT induced degradation of the BCR-ABL protein, which could be reversed by autophagy lysosome inhibitors Baf-A1 and CQ. Next, HHT treatment confirmed the induction of autophagy in K562G cells, and silencing the key autophagic proteins ATG5 and Beclin-1 inhibited the degradation of the BCR-ABL protein and cytotoxicity. In addition, autophagic receptor p62/SQSTM1(p62) participated during the autophagic degradation of BCR-ABL induced by HHT, and this was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation, in which HHT enhanced the ubiquitination of the BCR-ABL protein and promoted its binding to p62. In conclusion, HHT induced p62-mediated autophagy in imatinib-resistant CML K562G cells, thus promoting autophagic degradation of the BCR-ABL protein and providing a novel strategy for the treatment of TKI-resistant CML.

Keywords: homoharringtonine, chronic myelogenous leukemia, BCR-ABL, autophagic degradation, p62/SQSTM1

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) arises from pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells by a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, forming Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) (1). The product of this genetic rearrangement consists of BCR-ABL fusion protein with deregulated tyrosine kinase activity, leading to an endless proliferation of immune precursors (2). Over the past two decades, BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have markedly improved the treatment of CML (3–5). Despite these great advances, therapy-resistant leukemic stem cells (LSCs) still persist after TKI treatment, presenting an obstacle on the road to long-term progression-free survival (PFS) in CML patients (6). Recent findings have revealed that BCR-ABL fusion protein still had leukemogenic ability without tyrosine kinase activity (7,8), and the survival of CML stem cells was independent of tyrosine kinase activity of this fusion protein (9). These findings strongly call for new targeting strategies of BCR-ABL for CML treatment.

It is well established that downregulation of the BCR-ABL protein level could suppress the growth of CML cells, and many attempts have been made to achieve this purpose. Goussetis et al revealed that autophagic degradation of BCR-ABL fusion protein was critical for the potent exhibition of the anti-leukemic effects of As2O3 (10). According to previous studies, genetic knockdown technologies, such as antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNA, have been used for the downregulation of the protein levels of BCR-ABL in CML cells (11–13). Recently, potent degraders against BCR-ABL have been developed by conjugating dasatinib to ligands for E3 ubiquitin ligases, revealing a more sustained inhibition of CML cell growth than ABL kinase inhibitor (14).

Homoharringtonine (HHT), a plant alkaloid with antitumor properties, was originally identified nearly 40 years ago (15), and has been revealed to play an important role in the treatment of CML, both before and after the clinical use of TKIs (16,17). In 2010, the use of HHT for relapsed/refractory CML was approved by the FDA (18). HHT is an alternative treatment for patients with CML who exhibit resistance or intolerance to TKIs. The drug involves a distinct mechanism and may be able to inhibit leukemic stem cells, which play a key role in the progression of CML (19). There are different theories regarding the mechanisms of HHT. First, it is widely considered that HHT exerts a role in the treatment of leukemia. This is mainly achieved by inhibiting the synthesis of proteins associated with cell apoptosis and cell survival, such as Mcl-1, XIAP, and Myc (20–22). Recently, it was reported that HHT is involved in other mechanisms. For example, it can regulate alternative splicing of Bcl-x and caspase-9 and regulate Smad3 protein tyrosine kinase phosphorylation (23,24). Therefore, understanding the mechanism of HHT is very complex and has not been fully elucidated yet. In particular, it is unclear as to how HHT regulates the oncoprotein BCR-ABL. Although it has been reported that HHT could downregulate the BCR-ABL protein by inhibiting protein synthesis (25), it is speculated that there may be more specific mechanisms involved. In the present study, it was reported that HHT promoted oncoprotein BCR-ABL degradation and cell apoptosis in the imatinib-resistant CML K562G cell line, and the p62-mediated autophagy-lysosome pathway was involved in BCR-ABL protein degradation induced by HHT. Depletion of p62 or inhibition of autophagy not only reversed HHT-induced BCR-ABL protein degradation, but also affected cytotoxicity of HHT on CML cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

K562 and K562G cells were provided by Professor Jie Jin (The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University). The cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Imatinib-resistant K562G cells was established by culturing cells in gradually increasing concentrations of imatinib and gained resistance to imatinib over several months of culture (Appendix I). However, K562G cells do not contain mutations within the TK domain. Autophagic inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1) was purchased from Abcam, autophagic inhibitor chloroquine (CQ), proteasome inhibitor MG132 and cycloheximide (CHX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). HHT was purchased from Selleckchem (cat. no. s9015). Protein A/G plus agarose beads were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (cat. no. 20423). Compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to culture media until it reaches a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO. For the vehicle control, 0.1% DMSO alone was used.

Cell viability assay

K562, K562G, and siRNA-K562G cells were seeded in 384-well plates at a density of 8,000 cells/well, and then treated with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) or HHT at concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.2, 3.1, 1.56, 0.78 and 0.39 ng/ml for 48 h. Cell proliferation was assayed using an MTS assay (Promega Corp.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using the EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer).

Western blotting and antibodies

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (pH 7.4) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). Protein concentrations of the extracts were measured by BCA™ protein assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and equal amounts (20 µg) of total protein from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and then were transferred onto NC (nitrocellulose) membrane (Millipore, Minneapolis, MN, USA). NC membranes were blocked with 10% skim milk powder dissolved in TBST buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Then, NC membranes were washed with TBST, and then incubated with a primary antibody (dilution of 1:1,000) in TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight at 4°C. Next, membranes were washed with TBST three times and incubated with an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (dilution 1:10,000; cat. no. A16096) or anti-mouse secondary antibody (dilution 1:10,000; cat. no. 31430) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The signals were detected using an ECL reagent (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All western blots were replicated in three times and the intensity of the western blot signals was analyzed using ImageJ 1.8.0 analysis software (NIH; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The primary antibodies were as follows: Antibody against C-Abl (cat. no. sc-887) and antibody against ubiquitin (Ub; cat. no. sc-166553; both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), antibodies against p62 (cat. no. PM045; MBL Beijing Biotech Co., Ltd.), antibodies against LC3B (cat. no. 2775), antibodies against ATG5 (cat. no. 2630) and antibodies against Beclin-1 (cat. no. 3495; all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), antibodies against β-tubulin (cat. no. HC101-02) and antibodies against β-actin (cat. no. HC201-02; both from Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd.), antibodies against poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP)ribose polymerase (PARP; cat. no 9542) and antibodies against cleave caspase3 (cat. no. 9664; both from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

Flow cytometry for apoptotic analysis

The K562G cells were treated with concentrations of 0, 20, 50 and 80 ng/ml HHT for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells underwent centrifugation at 100 × g centrifugation for 5 min, and then were washed twice with cold PBS. The cells were resuspended with 100 µl 1X binding buffer, followed by the addition of 5 µl Annexin V-FITC and 10 µl PI staining solution (cat. no 556547; BD Biosciences) for 15 min. Next, cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur™).

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

K562G cells were treated with HHT and harvested at different time-points (0, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h). The cells were then washed once and lysed in IP buffer for 30 min (1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) with proteases (cat. no. 04693116001; Roche Diagnostics) and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,500 × g and a fraction was saved as a loading input control. The remaining lysates were incubated with p62 or c-Abl antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein A/G beads (cat. no. 20423; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were added for another 4 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed 5–7 times in IP buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted by directly adding SDS loading buffer with 2 mM DTT. Beads and the saved lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells transfected with Ad-mcherry-GFP-LC3 (cat. no C3011; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1×105/ml, and then were treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or 50 ng/ml HHT for 8 h followed by staining with 1 nM Hoechst 33342 (nuclear stain) for 10 min at 37°C. The cells were visualized using the Operetta CLS (Perkin Elmer) at an ×40 magnification under excitation/emission filters 587/610 nm (mcherry) and 350/461 nm (Hoechst 33342). The resulting images were then analyzed using Harmony software 4.6 (Perkin Elmer) and autophagosomes were quantified by counting the number of spots per mCherry-positive cells. Data represent the mean values of puncta per cell for mCherry-positive cells, and error bars represent standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test assuming equal variances. Representative confocal microscopy images were captured using an Olympus fluorescence microscope at an ×40 magnification [Olympus IX71 (fluorescence microscope); Olympus DP71 (CCD; Olympus Corp.].

Lentiviral infection and generation of stable cell lines

K562G cells were transfected with a lentiviral expression system for siRNA. LV-NC siRNA, LV-ATG5 siRNA, LV-Beclin-1 siRNA and LV-p62 siRNA lentivirus stocks were obtained from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. K562G cells were transfected with lentiviruses targeting ATG5, Beclin-1 or p62 with 8 µg/ml of Polybrene (cat. no. H9268; Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA). Two days after transfection, the medium was changed and 2 µg/ml of puromycin was added to select stable knockdown of ATG5, Beclin-1 or p62 gene K562G cells. Cells with stable reduction of ATG5, Beclin-1 or p62 were used to assess BCR-ABL levels and analyze the apoptotic sensitivity to HHT. The targeting sequences were as follows: ATG5, GAAGTTTGTCCTTCTGCTA; Beclin-1, CTCAGGAGAGGAGCCATTT; p62, GCATTGAAGTTGATATCGAT.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student-Newman-Keuls test were used to analyze the differences in the target protein level of western blotting data from ImageJ analysis. For the cell viability assay, data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 1 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The results are expressed as the means ± standard deviation. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05, P<0.01 and P<0.001 (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 as indicated in the figures and legends).

Results

HHT induces cell apoptosis and downregulates BCR-ABL in imatinib-resistant K562G cells

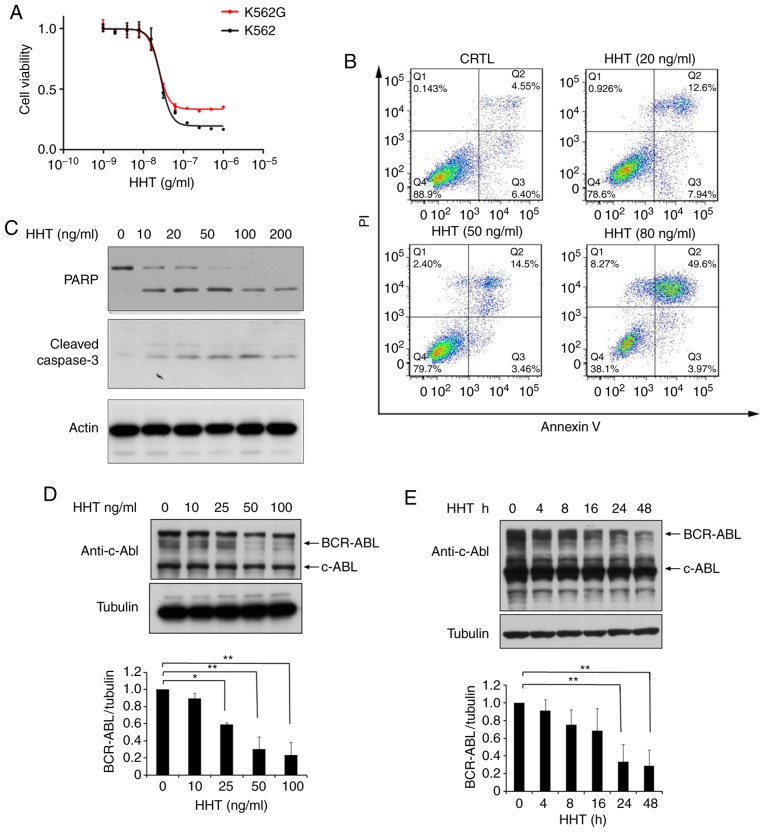

The K562G cell line was transformed from K562 cells and is widely used for leukemia research. To qualify the K562G cell line in the present study, the sensitivity of K562G cells to imatinib was verified. K562G exhibited high resistance to imatinib with a 10-fold difference compared to K562 cells (IC50, 320 nM vs. 38 nM; P<0.05; Fig. S1). The anti-proliferative effects of HHT in imatinib-sensitive K562 cells and imatinib-resistant K562G cells were compared. The two cell lines were treated with different concentrations of HHT for 48 h, respectively, and cell proliferation was assessed using MTS assay. The results revealed that the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of HHT in K562 and K562G cell lines was 27 and 24 ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 1A). HHT revealed similar cytotoxicity results in both cell lines. Subsequently, it was then investigated whether HHT could induce apoptosis in imatinib-resistant K562G cells. As revealed in Fig. 1B, K562G cells were treated with different concentrations of HHT at 0, 20, 50, 80 ng/ml for 24 h, and the apoptotic rates were 4.55, 12.6, 14.5 and 49.6%, respectively. Furthermore, it was revealed that HHT triggered a dose-dependent cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP in K562G cells (Fig. 1C), confirming the induction of cell apoptosis by HHT in imatinib-resistant K562G cells. BCR-ABL is the main pathogenic factor of CML, and thus the effects of HHT on BCR-ABL oncoprotein were examined. K562G cells were treated with different concentrations of HHT and the protein level of BCR-ABL was examined by western blotting. As anticipated, the levels of the BCR-ABL protein revealed a significant reduction by HHT treatment in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1D and E). In addition, HHT induced downregulation of BCR-ABL in K562 cells (Fig. S2). It is worth mentioning that HHT exhibited no significant effect on the c-Abl protein. These results indicated that HHT downregulated BCR-ABL oncoprotein and induced cell apoptosis in imatinib-resistant K562G CML cells.

Figure 1.

HHT induces cell apoptosis and downregulates BCR-ABL in CML cells. (A) HHT inhibited cell proliferation in K562 cells and K562G cells. K562 and K562G cells were treated with HHT at indicated concentrations for 48 h, respectively. Cell viability was determined by MTS assay. Values were presented as the means ± SD, of the three independent experiments. (B) HHT induced apoptosis in K562G cells. K562G cells were treated with 0, 20, 50, and 80 ng/ml HHT for 24 h, and cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometric analysis with Annexin-V/PI staining. (C) K562G cells were treated with different concentrations of HHT for 24 h. Cleaved PARP and caspase-3 were examined by western blotting. (D) BCR-ABL protein was downregulated by HHT in K562G cells. K562G cells were treated with HHT at indicated concentrations for 24 h. The concentrations were 0, 10, 25, 50 and 100 ng/ml. (E) K562G cells were treated with 20 ng/ml HHT at indicated time-points. Cell lysates were analyzed to determine BCR-ABL protein levels by western blotting. Densitometric values were quantified using the ImageJ software and normalized to the control. The values of the control were set to 1. Error bars represent the standard deviations for n=3 experiments and western blotting revealed representative data (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with the vehicle control). CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; HHT, homoharringtonine.

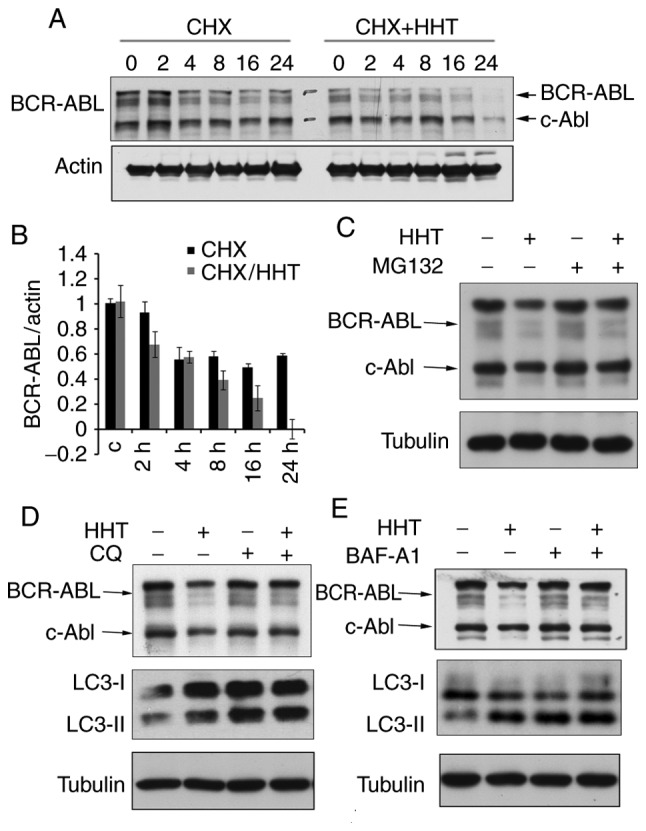

HHT promotes BCR-ABL degradation though the autophagy pathway

Since HHT could downregulate BCR-ABL oncoprotein, the next question was whether the downregulation was caused by inhibiting protein synthesis or by promoting its degradation. Some evidence has indicated that HHT downregulates BCR-ABL by inhibiting the synthesis of BCR-ABL (26). However, little attention has been paid to whether HHT affects protein degradation or not. To study the effect of HHT on BCR-ABL protein degradation, cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay was performed on HHT-treated K562G cells. The results revealed that the BCR-ABL protein levels began to decline at 2 h and were markedly decreased at 24 h in HHT-treated K562G cells, whereas in control cells, the BCR-ABL protein levels began to decline at 4 h and were maintained until 24 h (Fig. 2A and B). These results confirmed that HHT could promote BCR-ABL degradation. Protein degradation usually involves two pathways: The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the autophagy-lysosome pathway. To further investigate the mechanism of HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation, K562G cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors and autophagolysosome inhibitors, respectively and then their effects were observed on HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation. Proteasome inhibitor MG132 exhibited no obvious effect on HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation (Fig. 2C), however the autophagolysosome inhibitor CQ and Baf-A1 reversed the HHT-induced reduction of the protein levels of BCR-ABL (Fig. 2D and E). Similar results were also obtained in K562 cells (Fig. S3). These results indicated that the autophagy-lysosome pathway was involved in HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation.

Figure 2.

HHT promotes autophagic degradation of BCR-ABL in K562G cells. (A) HHT promoted BCR-ABL degradation during protein synthesis inhibition by CHX. K562G cells were treated with CHX (50 µg/ml) in the absence or presence of HHT (20 ng/ml) for different time-points followed by western blotting of the BCR-ABL protein. (B) Quantified BCR-ABL levels were normalized to β-actin. Error bars represent the standard deviations for n=3 experiments and western blotting revealed representative data. (C) Effects of proteasome inhibitors MG132 on HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation. K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for 16 h, and then co-treated with MG132 (10 µM) for 6 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. (D and E) The effects of autophagolysosome inhibitors CQ or Baf-A1 on HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation. K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for 16 h, and then co-treated with CQ (20 µM) or Baf-A1 (20 nM) for 6 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. HHT, homoharringtonine; CHX, cycloheximide; Baf-A1, Bafilomycin A1; CQ, chloroquine.

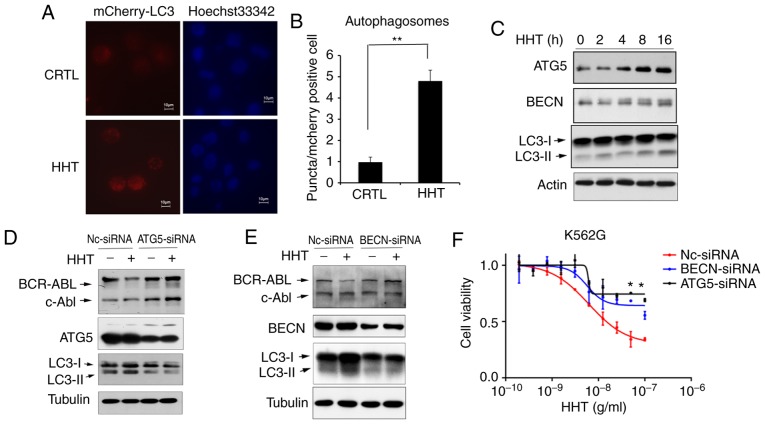

Inhibition of the autophagy pathway reversed the effect of HHT on BCR-ABL degradation and cell apoptosis in K562G cells. To confirm HHT-induced autophagy, K562G cells were transfected with Ad-mCherry-GFP-LC3B, which is considered as a well-documented model for monitoring the conversion of MAP1LC3B from a cytosolic MAP1LC3B-I form to a phagophore- and autophagosome-bound MAP1LC3B-II form. Under normal conditions, mCherry-GFP-LC3B fluorescence was diffused in the cytoplasm, while it converted to a punctate pattern when autophagy was activated. Next, treatment with 50 ng/ml of HHT for 8 h markedly increased the average number of fluorescent spots in mCherry-GFP-LC3B-positive cells (Fig. 3A and B), indicating that HHT induced autophagy in K562G cells. In addition, the levels of autophagic key proteins were detected by western blotting. The results revealed that treatment of K562G cells with HHT resulted in the upregulation of the LC3II/LC3I ratio and autophagic key factors ATG5 and Beclin-1 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the key molecules of autophagic machinery were targeted using specific siRNAs and assessed their effects on HHT-induced downregulation of the BCR-ABL protein. Selective knockdown of either Beclin-1 or ATG5 (Fig. 3D and E) reversed the suppressive effects of HHT treatment on the levels of BCR-ABL. In addition, siRNA-mediated silencing of autophagic machinery inhibited cytotoxicity of HHT on K562G cells (Fig. 3F). These results demonstrated that autophagic inhibition reversed the effect of HHT on BCR-ABL degradation and inhibited the cytotoxicity of HHT in K562G CML cells, further confirming that HHT induced BCR-ABL degradation via the autophagy pathway.

Figure 3.

HHT induces BCR-ABL degradation via the autophagy pathway. (A) Autophagosome levels in control and HHT-treated K562G cells. K562G cells were transfected with Ad-GFP-LC3B, and then treated with 50 ng/ml HHT for 8 h. Fluorescent images of mCherry-positive cells were analyzed by high-content screening. Representative images were captured on an Olympus fluorescence microscope at an ×40 magnification (Olympus IX71). (B) mCherry fluorescent puncta (autophagosomes, white arrowheads) were counted for 200 mCherry-positive cells per sample using Operetta High-Content Imaging System software (Harmony 4.6). The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that the two groups had significant differences in the number of autophagosomes (**P=0.008). Bar graphs represent the mean values and error bars represent the standard deviations (**P<0.01 vs. the vehicle control). (C) The autophagy pathway was activated by HHT in K562G cells. K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for indicated time-points, and then the cell lysates were analyzed for LC3, ATG5 and Beclin-1 by western blotting. (D) ATG5 knockdown prevented HHT-induced degradation of the BCR-ABL protein. ATG5 was stably knocked down in K562G cells (ATG5 siRNA) and control K562G cells (NC siRNA), and then the cells were treated with 20 ng/ml HHT for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting. (E) Beclin-1 knockdown prevented HHT-induced degradation of BCR-ABL protein. Beclin-1 was stably knocked down in K562G cells (BECN siRNA) and control K562G cells (NC siRNA), and then the cells were treated with 20 ng/ml HHT for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting. (F) Autophagy deficiency affected the cytotoxicity of HHT on K562G CML cells. Nc-siRNA, ATG5-siRNA and Beclin-1-siRNA K562G cells were treated with indicated concentrations of HHT for 48 h before assessing the viability by MTS assay. *P<0.05 compared to the cells transfected with NC siRNA. HHT, homoharringtonine; BECN, beclin-1.

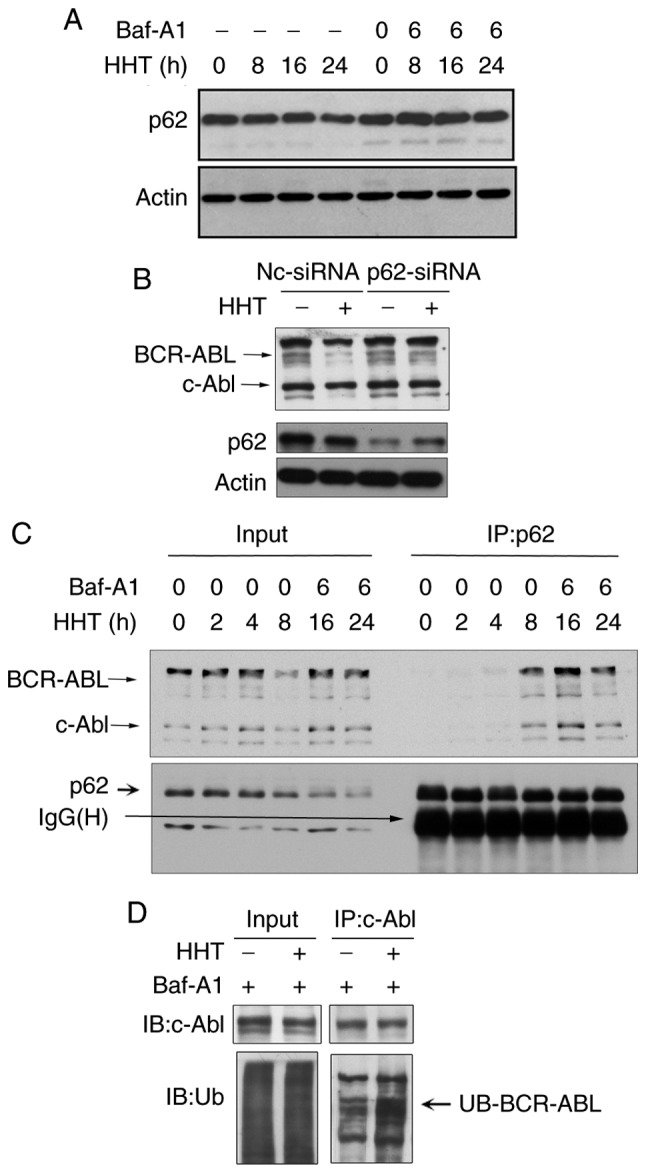

p62 is involved in HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation via the autophagy pathway

p62 plays an important role in the autophagy-lysosome pathway and was revealed to target polyubiquitinated proteins to autophagosomes for degradation by directly interacting with LC3 (27). Next, it was determined whether the classical autophagic receptor p62 was involved in HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation. Western blotting assays revealed that HHT induced a time-dependent decrease of p62 levels, whereas the autophagy inhibitor Baf-A1 inhibited the reduction of p62 (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that p62 may be related to autophagic degradation induced by HHT. Furthermore, siRNAs were designed to knockdown endogenous p62. As revealed in Fig. 4B, endogenous p62 expression was effectively inhibited with p62-siRNA, and p62 knockdown significantly reversed the decrease of BCR-ABL protein levels induced by HHT. These results confirmed that p62 was necessary for HHT-induced autophagic degradation of the BCR-ABL protein. Next, whether HHT promoted BCR-ABL to interact with p62 was assessed. K562G cells were treated with HHT for 0, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h and then were lysed, followed by immunoprecipitation with an anti-p62 antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-ABL antibody. To prevent the degradation of BCR-ABL and p62 from HHT treatment for 16 and 24 h, Baf-A1 (20 nM) was added during the last 6 h. An HHT-inducible time-dependent increase was observed during the interaction between BCR-ABL and p62 (Fig. 4C). Finally, the results revealed that ubiquitination levels of BCR-ABL were significantly increased in HHT-treated K562G cells when compared with the control group (Fig. 4D). These results indicated that HHT promoted the interaction of p62 with ubiquitinated BCR-ABL, and p62 was involved in the autophagic degradation of the BCR-ABL protein.

Figure 4.

p62 mediates HHT-induced BCR-ABL autophagic degradation. (A) K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for indicated time-points in the absence or presence of Baf-A1 (20 nM). p62 levels were analyzed by western blotting. (B) p62 knockdown reversed HHT-induced BCR-ABL degradation. p62 was knocked down in K562G cells (p62-siRNA) and control K562G cells (NC-siRNA) and then the cells were treated with 20 ng/ml HHT for 24 h and then subjected to immunoblotting. (C) HHT promoted endogenous p62 binding to BCR-ABL. K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for indicated time-points. In order to avoid degradation of BCR-ABL and p62, Baf-A1 (20 nM) was added in the last 6 h of HHT treatment for 16 and 24 h. The interaction of endogenous BCR-ABL and p62 was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-p62 antibody followed by western blotting with anti-c-Abl and anti-p62 antibodies. (D) HHT enhanced ubiquitination levels of BCR-ABL. K562G cells were treated with HHT (20 ng/ml) for 16 h, and Baf-A1 (20 nM) was added in the last 6 h. The ubiquitination was then detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl antibody followed by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin and anti-c-Abl antibodies. HHT, homoharringtonine; Baf-A1, Bafilomycin A1.

Discussion

BCR-ABL is the main oncogene of CML that causes malignant proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells. Inhibitors of ABL tyrosine kinase (TKIs) have been revealed to exhibit marked therapeutic effects on CML (28), however, mutations of several kinase domains have conferred high-level resistance to TKIs. Furthermore, TKIs cannot eliminate leukemic stem cells, as the survival of CML stem cells does not depend on the activity of BCR-ABL kinase (29). Therefore, it is necessary to explore novel therapeutic strategies to improve CML treatment.

HHT has been used in China for the treatment of hematological malignancies for over 40 years, and was approved by the FDA in the US for its use in refractory/relapsed CML in 2010. Despite its clinical efficacy, the exact underlying mechanisms are yet to be revealed. In the present study, HHT directly inhibited the protein levels of BCR-ABL by promoting the degradation of fusion protein, which was different from the previously reported mechanisms, i.e., inhibition of protein synthesis. This is considered a novel angle to investigate HHT and develop strategies to downregulate the levels of BCR-ABL, which in turn may shed new insights in the treatment of CML.

There are two major mechanisms involved in protein degradation, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagy-lysosome pathway (30). HHT activated autophagy in K562G cells in the present study. When autophagy was inhibited by ATG5 or Beclin-1 siRNA, HHT induced BCR-ABL protein degradation and apoptosis was also inhibited. In addition, autophagic lysosome inhibitors Baf-A1 and CQ reversed the degradation of BCR-ABL in K562G cells induced by HHT, however, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 did not reverse the degradation. Therefore, it is surmised that degradation of the BCR-ABL protein induced by HHT was mainly achieved through the autophagy-lysosome pathway.

Conventionally, autophagy requires membrane trafficking and remodeling for the formation of autophagosomes and delivers its internal contents to the lysosome for degradation. Although autophagy has been regarded as a random cytoplasmic degradation process, the involvement of ubiquitin as a targeting signal for selective autophagy is rapidly emerging (31,32). In addition, the selection of autophagy is mediated by autophagic receptors, such as SQSTM1/p62 and NBR1 (NBR1, autophagy cargo receptor). These autophagic receptors interact with both ubiquitin conjugated to target proteins and autophagosome-specific MAP1LC3/LC3, promoting protein autophagic degradation (33). As is well known, ubiquitin is a universal degradation signal used for protein degradation via proteasomes and autophagy (34). In the present study, HHT enhanced ubiquitination of the BCR-ABL protein, which may in turn provide signal recognition by autophagic receptor p62, and then lead to subsequent autophagic degradation. As anticipated, HHT treatment significantly facilitated the interaction of p62 with BCR-ABL. Moreover, knockdown of p62 in K562G cells reversed the effect of HHT on the degradation of BCR-ABL. These results demonstrated p62-mediated HHT-induced autophagic degradation of BCR-ABL. However, how HHT induces BCR-ABL ubiquitination and how p62 interacts with ubiquitin BCR-ABL require further study.

Collectively, these results reported that HHT induced autophagy in CML cells and promoted BCR-ABL ubiquitination. The ubiquitinated BCR-ABL was bound to p62 forming a BCR-ABL-p62 complex followed by autophagic degradation. The present study elucidated how HHT downregulated CML oncoprotein BCR-ABL, which may subsequently be a potential new strategy to overcome the resistance to TKIs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Jie Jin for providing K562 and K562G cells.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation under grant no. 81670139 to YT; and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai under grant no. 16ZR1427800 to YT.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YT and CW designed the research. SL, ZB and YJ performed the experiments. SL and XS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that accuracy or integrity of any parts of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Shtivelman E, Lifshitz B, Gale RP, Canaani E. Fused transcript of abl and bcr genes in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nature. 1985;315:550–554. doi: 10.1038/315550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druker BJ. Translation of the philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood. 2008;112:4808–4817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-077958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopade P, Akard LP. Improving outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia over time in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Use of second- and third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: An evolving treatment paradigm. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, Goldman JM, Miller CB, Ottmann OG, Schiffer CA, Talpaz M, Guilhot F, Deininger MW, et al. Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: Results of a phase II study. Blood. 2002;99:3530–3539. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson RA. Is there a best TKI for chronic phase CML? Blood. 2015;126:2370–2375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-641043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warmuth M, Bergmann M, Priess A, Hauslmann K, Emmerich B, Hallek M. The Src family kinase Hck interacts with Bcr-Abl by a kinase-independent mechanism and phosphorylates the Grb2-binding site of Bcr. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33260–33270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wertheim JA, Forsythe K, Druker BJ, Hammer D, Boettiger D, Pear WS. BCR-ABL-induced adhesion defects are tyrosine kinase-independent. Blood. 2002;99:4122–4130. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.11.4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue A, Kobayashi CI, Shinohara H, Miyamoto K, Yamauchi N, Yuda J, Akao Y, Minami Y. Chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells and molecular target therapies for overcoming resistance and disease persistence. Int J Hematol. 2018;108:365–370. doi: 10.1007/s12185-018-2519-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goussetis DJ, Gounaris E, Wu EJ, Vakana E, Sharma B, Bogyo M, Altman JK, Platanias LC. Autophagic degradation of the BCR-ABL oncoprotein and generation of antileukemic responses by arsenic trioxide. Blood. 2012;120:3555–3562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-402578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valencia-Serna J, Aliabadi HM, Manfrin A, Mohseni M, Jiang X, Uludag H. SiRNA/lipopolymer nanoparticles to arrest growth of chronic myeloid leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopham. 2018;130:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson BL, McCray PB., Jr Current prospects for RNA interference-based therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrg2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. Strategies for silencing human disease using RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:173–184. doi: 10.1038/nrg2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibata N, Shimokawa K, Nagai K, Ohoka N, Hattori T, Miyamoto N, Ujikawa O, Sameshima T, Nara H, Cho N, Naito M. Pharmacological difference between degrader and inhibitor against oncogenic BCR-ABL kinase. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13549. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31913-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu S, Wang J. Homoharringtonine and omacetaxine for myeloid hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintas-Cardama A, Cortes J. Therapeutic options against BCR-ABL1 T315I-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4392–4399. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien S, Kantarjian H, Keating M, Beran M, Koller C, Robertson LE, Hester J, Rios MB, Andreeff M, Talpaz M. Homoharringtonine therapy induces responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in late chronic phase. Blood. 1995;86:3322–3326. doi: 10.1182/blood.V86.9.3322.bloodjournal8693322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantarjian HM, O'Brien S, Cortes J. Homoharringtonine/omacetaxine mepesuccinate: The long and winding road to food and drug administration approval. Clin Lymphhoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Ustwani O, Griffiths EA, Wang ES, Wetzler M. Omacetaxine mepesuccinate in chronic myeloid leukemia. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:2397–2405. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.964642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurel G, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA. U2504 determines the species specificity of the A-site cleft antibiotics: The structures of tiamulin, homoharringtonine, and bruceantin bound to the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang MT. Harringtonine, an inhibitor of initiation of protein biosynthesis. Mol Pharm. 1975;11:511–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda J, Kamitsuji Y, Kimura S, Ashihara E, Kawata E, Nakagawa Y, Takeuichi M, Murotani Y, Yokota A, Tanaka R, et al. Anti-myeloma effect of homoharringtonine with concomitant targeting of the myeloma-promoting molecules, Mcl-1, XIAP, and beta-catenin. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:507–515. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Q, Li S, Li J, Fu Q, Wang Z, Li B, Liu SS, Su Z, Song J, Lu D. Homoharringtonine regulates the alternative splicing of Bcl-x and caspase 9 through a protein phosphatase 1-dependent mechanism. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:164. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Mu Q, Li X, Yin X, Yu M, Jin J, Li C, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Suo S, et al. Homoharringtonine targets Smad3 and TGF-β pathway to inhibit the proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40318–40326. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen R, Gandhi V, Plunkett W. A sequential blockade strategy for the design of combination therapies to overcome oncogene addiction in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10959–10966. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novotny L, Al-Tannak NF, Hunakova L. Protein synthesis inhibitors of natural origin for CML therapy: Semisynthetic homoharringtonine (Omacetaxine mepesuccinate) Neoplasma. 2016;63:495–503. doi: 10.4149/neo_2016_401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaffagnini G, Savova A, Danieli A, Romanov J, Tremel S, Ebner M, Peterbauer T, Sztacho M, Trapannone R, Tarafder AK, et al. P62 filaments capture and present ubiquitinated cargos for autophagy. EMBO J. 2018;37:e98308. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossari F, Minutolo F, Orciuolo E. Past, present, and future of Bcr-Abl inhibitors: From chemical development to clinical efficacy. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:84. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0624-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talati C, Pinilla-Ibarz J. Resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia: Definitions and novel therapeutic agents. Curr Opin Hematol. 2018;25:154–161. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikic I. Proteasomal and autophagic degradation systems. Ann Rev Biochem. 2017;86:193–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: Ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamark T, Svenning S, Johansen T. Regulation of selective autophagy: The p62/SQSTM1 paradigm. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:609–624. doi: 10.1042/EBC20170035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moscat J, Karin M, Diaz-Meco MT. P62 in Cancer: Signaling adaptor beyond autophagy. Cell. 2016;167:606–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kocaturk NM, Gozuacik D. Crosstalk between mammalian autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:128. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.