Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the present systematic review was to examine the scientific evidence for the efficacy of stabilized stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrice in relation to dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis and staining.

Data and sources

Medline OVID, Embase.com, and the Cochrane Library were searched from database inception until June 2017. Six researchers independently selected studies, extracted data, and assessed methodological quality. A meta-analysis of the 6-month gingivitis studies was done. Risk of bias was estimated using a checklist from the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment (SBU, 2018).

Study selection

Two studies on dental calculus, 21 on dental plaque and gingivitis, 4 on halitosis, and 5 on stain met the inclusion criteria. Risk of bias was high for the studies on dental calculus, halitosis, and stain, and varied for the dental plaque and gingivitis studies. Significant reductions in dental calculus and in halitosis were reported for the SnF2 dentifrice; no differences in stain reduction were noted. A meta-analysis on gingivitis found better results for the SnF2 dentifrice compared to other dentifrices, though the results of the individual trials in the meta-analyses showed a substantial heterogeneity.

Conclusions

The present review found that stabilized SnF2 toothpaste had a positive effect on the reduction of dental calculus build-up, dental plaque, gingivitis, stain and halitosis. A tendency towards a more pronounced effect than using toothpastes not containing SnF2 was found. However, a new generation of well conducted randomized trials are needed to further support these findings.

Clinical relevance

Adding a SnF2 toothpaste to the daily oral care routine is an easy strategy that may have multiple oral health benefits.

Keywords: Dentistry, Stabilized stannous fluoride, Dental calculus, Dental plaque, Gingivitis, Halitosis, Stain

Dentistry; Stabilized stannous fluoride; Dental calculus; Dental plaque; Gingivitis; Halitosis; Stain.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, awareness of the importance of oral health in relation to well-being and general health has grown [1]. Dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis, and stain are all conditions of great concern in both objective and subjective perspectives. Gingivitis, inflammation of the gum, is one of the most common diseases in the world [2]. Prevalence is high and varies extensively due to assessment method, population, and age group [3, 4]. The primary causative factor of gingivitis is dental plaque, a biofilm formed by bacteria that have been colonizing on the teeth for a prolonged period of time [5, 6]. Plaque-induced gingivitis can be prevented with good oral hygiene, which includes regular tooth brushing and interproximal cleaning [7, 8]. Moreover, patient-administered mechanical plaque control is an effective preventive measure.

Tooth stain may be due to several factors, for example, coffee, tea, tobacco, and wine. If dental plaque is not removed, it may lead to calculus formation, halitosis, and eventually periodontal disease [9, 10]. Dental calculus forms when non-mineralized biofilms rich in oral bacteria become mineralized with calcium phosphate mineral salts [11, 12]. This mineralized biofilm may develop both supra- and subgingivally. The significance of dental calculus in the initiation and progression of periodontitis has been demonstrated [12]. Similar to gingivitis, bacterial plaque may also induce inflammation around dental implants, that is, peri-implant mucositis [13], which can develop into peri-implantitis.

Halitosis (bad breath, malodor) has a mean prevalence of 31.8 % [14] ranging from 1.5% to 100%, depending on how the condition has been assessed or defined [15]. The degree of halitosis varies throughout the day, with higher levels often occurring in morning breath. The etiological factors are primarily related to the bacterial degradation of proteins, which creates high concentrations of volatile sulphur compounds [16]. Halitosis may also originate from pathological conditions such as throat infections, tonsillitis, and lung disease [16]. Today, subjective and objective methods are available for assessing VSCs in exhaled air. Halitosis treatment is focused on oral hygiene, in particular tooth brushing, as well as tongue cleaning. Mouth rinses and dentifrices containing various active ingredients, such as metal salts, essential oils, and chlorhexidine have also been found to be effective in reducing VSC levels [17].

In home dental care, the most widely used method to clean teeth efficiently is tooth brushing with dentifrices [18, 19]. Today, numerous commercial dentifrices are available, and they are composed of different active ingredients, each with a special function, for example, anti-calculus agents, anti-bacterial agents, and anti-cavity agents. Fluorides have, in general, been considered the most important active ingredient in a toothpaste. Over the years, various fluoride formulations have been used, for example, sodium fluoride (NaF), sodium monofluorophosphate (SMFP), amine fluoride, and stannous fluoride (SnF2). The first toothpaste with a clinically proven anti-cavity effect contained SnF2 and was introduced in the 1950s [20]. However, the SnF2 formula had some limitations, such as the potential to cause extrinsic tooth staining.

Aside from purported effects on gingivitis, caries, dental plaque, halitosis, and stain, dentifrices with an anti-calculus effect have been a focus of interest for many years. The first toothpaste to have a clinically proven anti-calculus effect was introduced in 1985 and contained sodium pyrophosphate as the anti-calculus ingredient [21].

A longer chain variant of pyrophosphate, sodium hexametaphosphate (SHMP) with increased anti-staining and anti-calculus effects, was added to dentifrice formulations [22, 23]. This addition overcame the staining problem caused by SnF2.

Since SnF2 is still considered to be superior compared to other fluoride compounds, a literature review for evidence of its effect on various oral conditions is valuable. The aim of this review was to systematically examine the scientific evidence for the efficacy of stabilized SnF2 dentifrice in relation to dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis, and stain.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Eligibility

A Population/Problems, Intervention, Comparison/Control, Outcome (PICO) process was used to develop the inclusion criteria: studies must be in vivo or in situ; the publication language, English; and publication year 1990 or later. Inclusion criteria concerning intervention, comparisons and outcome variables were specified for each category:

2.1.1. Population/problem

Individuals with, or at risk for, one or more of five dental problems: dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis, and stain.

2.1.2. Intervention

Tooth cleaning with a manual or electric tooth brush and a stabilized SnF2 dentifrice, or with experimental slurries containing stabilized SnF2.

2.1.3. Comparison

Tooth brushing twice daily with another fluoridated or non-fluoridated dentifrice, a placebo, or no treatment.

2.1.4. Outcome

Dental calculus: the Volpe-Manhold Calculus Index [24]; dental plaque: various plaque indices [25, 26, 27]; gingivitis: the Gingival Index [28, 29], the Modified Gingival Index [30], the Gingival Bleeding Index [31], or the Bleeding Index [32]; halitosis: a reduction in volatile sulphur compounds [33]; and stain: the Lobene stain index [34].

2.2. Exclusion criteria

Duplicates, reviews, in vitro studies, animal studies, and non-controlled studies were omitted. Other exclusion criteria were (i) the test dentifrice contained stannous chloride or SnF2 in combination with potassium nitrate or amino fluorides, (ii) the SnF2 formulation was applied in a gel, (iii) ionic or laser toothbrushes were used, (iv) a mouthwash was used (Table 1), (v) outcome data regarding dental plaque, gingivitis, stain, or halitosis were unclear.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) |

| Controlled clinical trials (CCTs) |

| In the control group: no limitation |

| In the test group: stannous fluoride (SnF2) or combinations: 0.454 % SnF2 0.454 % SnF2 + SHMP (sodium hexametaphosphate) 0.454 % SnF2 + 5% sodium polyphosphate 0.454 % SnF2 + calcium pyrophosphate 0.454 % SnF2 + 350 ppm NaF (sodium fluoride) |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Articles published before 1990 |

| Only abstract/Erratum |

| Reviews |

| Animal studies |

| In vitro studies |

| No control group |

| No relevant outcome variable |

| Mouth rinse or gel |

| Ionized toothbrush or laser in the treatment with SnF2 |

| SnF2 + 5% KNO3 (potassium nitrate) |

| SnF2 + AmF (amine fluoride) |

| SnCl2 (stannous chloride) |

2.3. Literature search strategy

We searched Medline OVID (including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations), Embase.com, and the Cochrane Library using medical subject headings (MeSH) associated with SnF2, dentifrices, the dental problems being assessed in this review, and related dental problems. The MeSH terms identified in Medline were adapted to Embase and Cochrane. We also used free-text terms and, when appropriate, truncated and/or combined the search terms with proximity operators.

The following search terms were used: gingivitis, dental plaque, dental plaque index, plaque control, gingival hemorrhage, bleeding on probing, biofilms, inflammation, dental calculus, anti-calculus, calcificat, tartar, dental, tooth, teeth, tooth discolorations, stain, halitosis, malodor odor, breath, fetor oris, fetor ex, or foetor, periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, chronic periodontitis, periodontal pocket, periapical abscess, periapical granuloma, peri-implantitis, tin fluorides, stannic, fluoride, difluoride, tetrafluoride, stannofluoride, snf, dentifrices, paste, and toothpaste; the free-text terms we used were crest pro health, crest gum care, and crest plus gum care.

Information specialists at the university library at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm searched from database inception until January 2018 (dental calculus, dental plaque/gingivitis, stain, halitosis) according to the PRISMA flow chart (http://prisma-statement.org/). The authors also conducted searches by hand after reading the reference lists of retrieved full-text papers to identify additional articles.

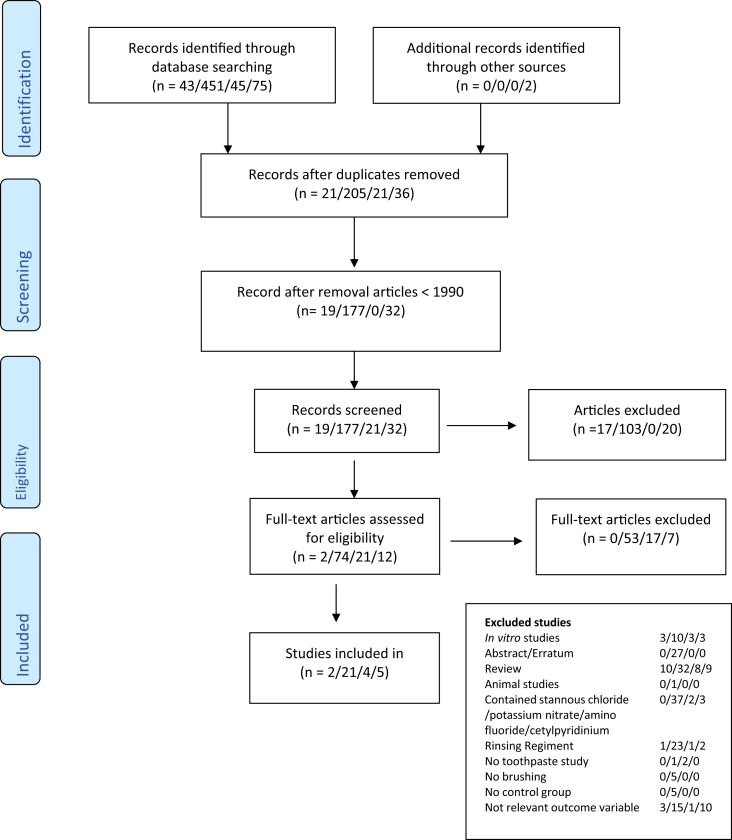

2.4. Study selection

The reviewers formed pairs. Each pair reviewed one of the problem categories: dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis, and stain. Each of the reviewers in a pair independently screened all titles and abstracts for a category to identify potentially eligible studies. The reasons for excluding a study were noted (Table 1). Studies that met the inclusion criteria were obtained in full text and assessed for eligibility. When the two reviewers disagreed, consensus was reached by discussion. The reviewers were not blinded to authorship or journal. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search and article selection in a flow chart.

Figure 1.

Flow chart presenting the literature search for dental calculus, dental plaque/gingivitis, halitosis and stain. (n = dental calculus/dental plaque + gingivitis/halitosis/stain).

2.5. Data extraction

Data were extracted and tabularized from all studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). The present review reports only baseline and final results. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) or standard errors (SEs) were extracted from the studies.

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

Each reviewer in a pair independently scored the methodological quality of the included studies. Quality was rated using a risk bias assessment checklist developed by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment [35]. The SBU risk bias checklist is similar to the Cochrane checklist (http://www.cochrane.org/). In short, selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias were rated. Based on this information, risk of bias was judged as low, medium, or high.

2.7. Data analysis

The outcome of the intervention compared to placebo was of interest for estimating treatment efficacy. Since few studies were available to form the same pairwise comparisons, a random-effect meta-analysis was applied only for 6-month gingivitis studies. All SE values were recalculated into SD using the formula Since some studies used different indices to measure gingivitis the means and SDs of assessments of gingival inflammation reported at 6 months were used to estimate the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Heterogeneity was quantified using I2 and tested using Cochran's Q statistic. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

The literature search identified 42 articles referring to dental calculus, 451 to dental plaque and gingivitis, 45 to halitosis, and 75 to stain (Figure 1). After duplicates were excluded, 279 abstracts remained and were screened. Two papers on dental calculus, 21 on dental plaque/gingivitis, 4 on halitosis, and 5 on stain were reviewed in full text. Hand searching yielded no additional articles.

3.1. Dental calculus

The two included studies (Table 2) were published between 2005 and 2007. Both were double-blinded, randomized, and parallel-grouped 6-month trials representing 222 participants (age range 19–63 y) with 113 patients in test groups and 109 in control groups. The test toothpaste in both studies was 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP. One study used a positive control (0.243% NaF +0.3% triclosan; [36], and one a negative (0.243% NaF; [37]. After 6 months, the Volpe-Manhold Calculus Index showed 55%–56% lower values for the test toothpaste than either of the positive or negative controls. The differences were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies on dental calculus.

| Authors |

Study design |

Study population |

Intervention (I) |

Control (C ) |

Treatment/ |

Outcome |

Comments |

Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (year) |

Methods |

Number (gender) |

Toothpaste |

Positive/negative |

brushing |

of bias |

||

| Duration |

Age (range) |

|||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| Schiff et al | randomized | n=80 (49 male/31 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Brushing twice | BL: | No drop outs | High |

| 2005 | double-blind | 27.5 (19-45) yrs. | positive control | daily for for 1 min. | I: 16.66 | |||

| parallel group | C: 15.88 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| I=40 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| V-MI | C=40 | 6M | ||||||

| USA | I: 5.41 | Superior anti-calculus | ||||||

| 6 M | C: 15.79 | effect for SnF2 | ||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||

| I vs C: 56% (p<0.0001) | ||||||||

| Winston et al | randomized | n=142 (70 male/72 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF | Brushing twice | BL: | Drop-out=4 | High |

| 2007 | double-blind | daily for for 1 min. | I: 27.21 | |||||

| parallel group | 34 (19-63) yrs. | negative control | C: 27.84 | Sponsored by | ||||

| Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| V-MI | USA | 6M: | ||||||

| I: 9.27 | Superior anti-calculus | |||||||

| 6 M | C: 20.78 | effect for SnF2 | ||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||

| I: vs C 55 (p<0.001) | ||||||||

BL (baseline), I (intervention), C (control), NaF (Sodium fluoride), SnF2 (Stannous fluoride), TCN (Triclosan), SHMP (Sodium hexametaphosphate), V-MI (Volpe-Manhold index).

3.2. Dental plaque and gingivitis

Twenty-one full-text articles published between 1995 and 2013 met the inclusion criteria (Table 2). Table 3 presents the study design, characteristics, outcome variables, results, and risk of bias of the included studies in detail.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies on dental plaque and gingivitis.

| Authors |

Study design |

Study population |

Intervention (I) |

Control (C ) |

Treatment/ |

Outcome |

Outcome |

Outcome |

Comments |

Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (year) |

Methods |

Number (gender) |

Toothpaste |

Positive/negative |

brushing |

Plaque Index |

Gingival Index |

Gingival Bleeding |

of bias |

|

| Duration |

Age (range) |

|||||||||

| Country | ||||||||||

| Archila et al | randomized | n= 186 | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.234% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Baseline prophylaxis. | GI: (mean ±SD) | GB: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=11 | Medium | |

| 2004 | double-blind | I: n= 95 (33 male/ 63 female) | positive control | Brushing twice | BL: | BL: | ||||

| parallel | 30.7±10.0 (17-65) yrs. | daily for for 1 min. | I: 0.51±0.32 | I: 40.0±25.7 | Sponsored by | |||||

| single center | Supervised twice- | C: 0.50±0.25 | Cl: 39.8±20.3 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||

| C: n= 91 (30 male/ 61 female) | daily 3 days/week | |||||||||

| GI: (Löe & Silness 1963) | 29.4±9.1 (30 male/61 female) | 3M (mean ±SE) | 3 M (mean ±SE) | |||||||

| GB: Gingival Bleeding | I: 0.18±0.01 | I: 13.9±1.05 | ||||||||

| ( no of sites) | USA | C: 0.31±0.01 | C: 24.6±1.07 | |||||||

| 6 M | 6M (mean ±SE) | 6M (mean ±SE) | ||||||||

| I: 0.27±0.02 | I: 21.0±1.46 | |||||||||

| Cl: 0.37±0.02 | C: 28.9±1.49 | |||||||||

| GI Reduction (%) | GB reduction (%) | |||||||||

| 3M: 42.6% p< 0.001 | 3M: 43.4% p=0.001 | |||||||||

| 6M: 25.8% p=0.001 | 6M: 27.4% p=0.001 | |||||||||

| Barnes et al | randomized | n=25 | I: 0.454% SnF2 + | C: 0.234% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Baseline prophylaxis | MGMPI: (mean ±SD) | No drop outs | High | ||

| 2010 | double-blind | R: 18-65 yrs. | SHMP/ZN- lactate | positive control | Scaling and prophylaxis, | Study 1 | ||||

| cross-over | remove dental plaque | I: 22.05± 12.42 | Sponsored by | |||||||

| 3 studies – conducted with | and dental calculus | C: 14.14± 8.02 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| Modified Gingival Margin | same clinical procedures. | before the study | ||||||||

| Plaque index (MGMPI) | Study 2 | |||||||||

| USA | Washout period –use | I: 25.35± 10.48 | ||||||||

| 24 H | Colgate 0.76 % SMFP | C: 12.95± 7.18 | ||||||||

| Study 3 | ||||||||||

| I: 27.09± 11.95 | ||||||||||

| C: 9.65± 8.30 | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| I vs. C: Advantage C. | ||||||||||

| Study 1: 7.91 p=0.05 | ||||||||||

| Study 2: 12.4 p=0.05 | ||||||||||

| Study 3: 17.44 p=0.05 | ||||||||||

| Beiswanger et al | randomized | n= 463 | IA: 0.454% SnF2 + | C: 0.243% NaF | No instructions. | PLI: (mean ±SE) | GI: (mean ±SE) | GB: (mean ±SE) no of sites | Drop out: n=47 | Medium |

| 1995 | double-blind | BL: | 2.08% sodium gluconate | Negative control | BL: | BL: | BL: | |||

| parallel | IA: n=157 (50 male/107 female) | IA: 1.03±0.03 | IA: 0.67±0.02 | IA: 17.6±1.2 | Sponsored by | |||||

| single center | 33.34 (18-68) yrs. | IB: 0.454% SnF2 + | IB: 0,97±0.04 | IB: 0,70±0.02 | IB: 18.2±1.3 | Procter & Gamble | ||||

| 4.16% sodium gluconate | C: 0.95±0.03 | IC: 0.70±0.02 | C: 18.7±1.1 | |||||||

| PLI: (Silness & Löe 1964) | IB: n=153 (50 male/ 103 female) | |||||||||

| GI: (Löe 1967) | 34.13 (19-67) yrs. | 3M: | 3M: | 3M: | ||||||

| GB: Gingival bleeding | IA: 1.03±0.03 | IA: 0.68±0.02 | IA: 17.6±01.2 | |||||||

| (no of sites) | C: n=153 (45 male/ 108 female) | IB: 0.96±0.03 | IB: 0.70±0.02 | IB: 18.2±1.3 | ||||||

| 32.34 (18-64) yrs. | C: 0.93±0.03 | C: 0.69±0.02 | C: 18.4±1.1 | |||||||

| 6 M | ||||||||||

| 6M: | 6M: | 6M: | 6M: | |||||||

| IA: n=140 (44 male/ 96 female) | IA: 1.03±0.03 | IA: 0.68±0.02 | IA: 17.6±1.2 | |||||||

| 33.79 (18-68) yrs. | IB: 0.96±0.04 | IB: 0.69±0.02 | IB: 18.2±1.3 | |||||||

| C: 0.95±0.03 | C: 0.71±0.02 | C: 18.7±1.1 | ||||||||

| IB: n=140 (49 male/ 91 female) | ||||||||||

| 34.55 (19-67) yrs. | 6M reduction | 6M reduction | 6M reduction | |||||||

| IA and IB vs C: | IA and IB vs C: | IA and IB vs C: | ||||||||

| C: n=136 (41 male/ 95 female) | IA: 2.6% NS | IA: 18.8% NS | IA: 30.5% NS | |||||||

| 32.64 (19-64) yrs. | IB: 1.6% NS | IB: 18.0% NS | IB: 23.1% NS | |||||||

| USA | ||||||||||

| Beiswanger et al | randomized | N= 835 | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C1: 0.243% NaF | Oral prophylaxis | PLI: (mean ±SE) | GI: (mean ±SE) | GB: (mean ±SE) | Drop out: n=83 | Medium |

| 1997 | double-blind | BL: | Negative control | BL: | BL: | BL: (%) | ||||

| parallel | I: n=278 (77 male/201 female) | I: 0.73±0.02 | I: 0,86±0.02 | I: 24.876±1.05 | Sponsored by | |||||

| single center | 36.3 ±0.62 | C2) 0.243% NaF + PHEN | C1: 0.67±0.03 | C1: 0.84±0.02 | C1: 23.36±1.37 | Procter & Gamble | ||||

| (Listerine®) | C2: 0.70±0.02 | C2: 0.88±0.02 | C2: 26.18±1.16 | |||||||

| PLI: (Silness & Löe 1964) | C1: n= 144 (40 male/104 female) | Positive control | C3: 0.74±0.03 | C3: 0.89±0.02 | C3: 24.87±1.81 | |||||

| 36.1 ± 0.90 | ||||||||||

| GI: (Löe 1967) | 3M: | 3M: | 3M: (%) | |||||||

| C2: n= 289 (71 male/218 female) | C3) 0.243% NaF + Baking | I: 0.51±0.02 | I: 0.72±0.01 | I: 18.05±0.56 | ||||||

| GB: Gingival bleeding | 35.7 ±0.59 | soda + Hydrogen peroxide | C1: 0.50±0.02 | C1: 0.79±0.01 | C1: 22.02±01.77 | |||||

| (no of sites) | Positive control | C2: 0.44±0.02 | C2: 0.73±0.01 | C2: 20.33±0.55 | ||||||

| C3: n=148 (40 male/108 female) | C3: 0.54±0.02 | C3: 0.77±0.01 | C3: 21.31±0.76 | |||||||

| 6M | 36.5 ± 0.85 | |||||||||

| 6M: | 6M: | 6M: (%) | ||||||||

| 6M | I: 0.55±0.02 | I: 0.64±0.01 | I: 16.13±0.65 | |||||||

| I: 267 | C1: 0.54±0.02 | C1: 0.78±0.02 | C1: 22.25±0.90 | |||||||

| CI: n=140 | C2: 0.48±0.02 | C2: 0.73±0.02 | C2: 20.95±0.63 | |||||||

| C2: n= 281 | C3: 0.58±0.02 | C3: 0.74±0.02 | C3: 21.82±1.1 | |||||||

| C3: n= 147 | ||||||||||

| No data regarding gender and | 6M PLI (%) | 6M GI (%) | 6M GB (%) | |||||||

| mean age | I vs C3: 4.2 | I vs C1: 17.5 p=0.05 | I vs C1: 27.5 p=0.05 | |||||||

| C2 vs C3: 16.2 p=0.05 | I vs C2: 10.8 p=0.05 | I vs C2: 23.0 p=0.05 | ||||||||

| USA | C2 vs I: 12.5 p=0.05 | I vs C3: 13.8 p=0.05 | I vs C3: 26.1 p=0.05 | |||||||

| C2 vs C1: 10.8 p=0.05 | C2 vs C1: 7.4 p=0.05 | C2 vs C1: 5.9 NS | ||||||||

| C2 vs I: 2.0 NS | C2 vs C3: 3.4 NS | C2 vs C3: 4.0 NS | ||||||||

| C2 vs C4: 6.1 NS | C3 vs C1: 4.2 NS | C3 vs C1: 1.9 NS | ||||||||

| Bellamy et al | randomized | n=21 | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.76% SMFP + 2% | Brushing with | DPIA: mean ±SE, % plaque | No drop outs | High | ||

| 2008 | double-blind | Zn-Citrat | standardized fluoride | coverage | ||||||

| cross-over | R: 20-60 yrs. | Positive control | (non-antibacterial) TP for | A.M. Pre-brush | Sponsored by | |||||

| two weeks. | I: 9.63±106 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| Digital plaque imaging | England | C: 12.90±1.01 | ||||||||

| analysis (DPIA) | ||||||||||

| A.M. Post-brush | ||||||||||

| 15 days | I: 4.89±0.36 | |||||||||

| C: 5.76±0.34 | ||||||||||

| P.M. | ||||||||||

| I: 9.15±1.12 | ||||||||||

| C: 11.92±1.06 | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| A.M. Pre-brush 25.32 p=0.05 | ||||||||||

| A.M. Post-brush 15.13 NS | ||||||||||

| P.M. 23.24 p=0.09 | ||||||||||

| Bellamy et al | randomized | n=25 (11 male/ 15 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.32% NaF | Pre-treatment with NaF TP | DPIA: (mean ±SE) % plaque | No drop outs | High | ||

| 2009A | double-blind | Negative control | Brushing twice daily. | |||||||

| Two treatment and a | 35.3 (25-57) yrs. | No other oral hygiene aids. | A.M. Pre-brush | Sponsored by | ||||||

| four-day washout period. | I. 12.5±1.63 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| England | C. 16.24±1.63 | |||||||||

| Digital plaque imaging | ||||||||||

| analysis (DPIA) | A.M. Post-brush | |||||||||

| I. 5.39±0.89 | ||||||||||

| 17 days | C. 6.52±0.89 | |||||||||

| P.M. | ||||||||||

| I. 9.46±1,26 | ||||||||||

| C. 12.22±1.26 | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| A.M. Pre-brush 23.03 | ||||||||||

| p= 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| A.M. Post-brush 17.33 | ||||||||||

| p= 0.01 | ||||||||||

| P.M. 22.59 p= 0.0004 | ||||||||||

| Bellamy et al | randomized | n=27 (14 male/ 13 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 1400 ppm AlF | DPIA: (mean ±SE) % plaque | Drop out: n=2 | High | |||

| 2009B | double-blind | 0.05% chlorhexidine + | coverage: | |||||||

| crossover | 35.2 (25-57) yrs. | 0.08% aluminium lactate | A.M. Pre-brush | Sponsored by | ||||||

| Two treatment and a | (AlF3/Chx) | I: 13.08±1.46 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| four-day washout period. | England | C: 16.16±1.46 | ||||||||

| Positive control | ||||||||||

| Digital plaque imaging | A.M. Post-brush | |||||||||

| analysis (DPIA) | I: 5.31±0.87 | |||||||||

| C: 7.14±0.87 | ||||||||||

| 17 days | ||||||||||

| P.M. | ||||||||||

| I: 9.76±1.27 | ||||||||||

| C: 12.17±1.27 | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| A.M. Pre-brush 19.37 | ||||||||||

| p=0.0043 | ||||||||||

| A.M. Post-brush 25.63 | ||||||||||

| p=0.0014 | ||||||||||

| P.M. 19.80 p=0.0057 | ||||||||||

| Boneta et al | randomized | n=109 | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.234% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Brushing twice daily for | PLI: (mean ±SD) | GI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=12 | Medium | |

| 2010 | double-blind | Positive control | 1 min. | BL: | BL: | |||||

| parallel | I: n=55 (14 male/41 female) | I: 3.19±0.64 | I: 2.18±0.40 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| single center | 39 (21-68) yrs. | C: 3.16±0.64 | C: 2.17±0.36 | Colgate | ||||||

| PLI= Turesky modification of | C: n= 54 (18 male/36 female) | 3M (mean ±SE) | 3M (mean ±SE) | |||||||

| the Quigley and Hein | 40 (21-63) yrs. | I: 2.46±0,51 | I: 1.48±0.25 | |||||||

| (Quigley & Hein 1962, | C: 1.95±0.61 | C: 1.20±0.27 | ||||||||

| Turesky et al 1970) | USA | |||||||||

| 6M (mean ±SE) | 6M (mean ±SE) | |||||||||

| GI: (Löe & Silness 1963) | I: 2.36±0.55 | I: 1.40±0.28 | ||||||||

| C: 1.75±0.65 | C: 1.16±0.29 | |||||||||

| 6M | ||||||||||

| 6M Reduktion % | 6M Reduktion % | |||||||||

| I: 32.1 | I: 35.8 | |||||||||

| C: 44.7 | C: 46.5 | |||||||||

| 6M: % treatment diff. | 6M: % treatment diff. | |||||||||

| I vs C: 18.9 p=0.05 | I vs C: 17.1 p=0.05 | |||||||||

| Gerlach & Amini | randomized | n= 97 (60% female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C: 1000 ppm SMFP + | MGI: (mean ±SD) | GB: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=3 | High | ||

| 2012 | controlled | 33.6 ±11.1 (18-66) yrs. | 450 ppm NaF | BL: | BL: | |||||

| clinical trial | Negative control | I: 2.18 ± 0.10 | I: 14.9± 8.89 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| I: n=49 | C: 2.19 ± 0.10 | C: 16.1± 9.72 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| MGI: Modified Gingivitis index | C: n=48 | |||||||||

| (Lobene 1986) | 3M: no data in the article | 3M: (adjusted mean) | ||||||||

| USA | 1: 4.2 | |||||||||

| GB: Gingival bleeding | 2: 15.4 | |||||||||

| (no of sites) | ||||||||||

| Improvement GBI %: | ||||||||||

| 3M | 1. -74% p=0.001 | |||||||||

| 2. 2% NS | ||||||||||

| Mallatt et al | randomized | n= 128 | I: 0.454 SnF2 + SHMP | C: SMFP | PLI: (mean ±SD) | MGI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=12 | Medium | ||

| 2007 | double-blind | Negative control | BL. | BL. | ||||||

| parallel, clinical study | Age: Range 18-65 yr. | I: 2.88±0.34 | I: 2.00 ± 0.13 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| single center | C: 2.79±0.42 | C: 2.00 ± 0.13 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| I: n=62 (25 male/ 37 female) | ||||||||||

| PLI: Turesky Modified Quigley- | 6M: | 6M: | ||||||||

| Hein (Turesky et al 1970) | C: n=66 (23 male/37 female) | I: 2.20±0.40 | T: 1.58±0.31 | |||||||

| C: 2.34±0.49 | C: 1.90 ±0.21 | |||||||||

| MGI: Modified gingival index | USA | |||||||||

| (Lobene 1986) | PLI | MGI reduction % | ||||||||

| I vs C: 8.5 % p=0.001 | I vs C: 16.9 p=0.001 | |||||||||

| GBI: Gingival bleeding index | ||||||||||

| (Saxton & van der Ouderaa | GBI: mean ±SD | |||||||||

| 1989) | BL. | |||||||||

| I: 10.86±4.93 | ||||||||||

| 6M | C: 10.90±3.92 | |||||||||

| 6M: | ||||||||||

| I: 5.08±4.89 | ||||||||||

| C: 8.53±4.48 | ||||||||||

| GBI reduction % | ||||||||||

| I vs C: 40.8 p=0.001 | ||||||||||

| Mankodi et al | randomized | n= 130 | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.76% SMFP | Dental prophylaxis | PLI: (mean ±SD) | MGI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=13 | Medium | |

| 2005 | double-blind | Negative control | Tooth brushing for 1 min | BL: | BL: | |||||

| parallel | I: n=64 (20 male/44 female) | 2 times/day | I: 2.73±0.41 | I: 2.03±0.10 | Sponsored by | |||||

| 37.1± 10.9 (18-65) yrs. | C: 2.91±0.35 | C: 2.04±0.10 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| PLI: Turesky Modified Quigley- | ||||||||||

| Hein (Turesky et al 1970) | C: n=66 (23 male/43 female) | 3M (mean ±SE) | 3M (mean ±SE) | |||||||

| 38.5 ± 11.3 (18-64) yrs. | I: 2.24±0.05 | I: 1.75±0.02 | ||||||||

| MGI: Modified Gingival Index | C: 2.38±0.05 | C: 1.98±0.02 | ||||||||

| (Lobene 1986) | USA | |||||||||

| 6M (mean ±SE) | 6M (mean ±SE) | |||||||||

| GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index | I: 2.14±0.05 | I: 1.57±0.03 | ||||||||

| (Saxton & van der Ouderaa | C: 2.30±0.05 | C: 2.01±0.03 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||||

| 6M % treatment diff. | 6M % treatment diff. | |||||||||

| 6M | I vs C: 6.9 p=0.001 | I vs C: 21.7% p=0.001 | ||||||||

| GBI: (mean ±SD) | ||||||||||

| BL | ||||||||||

| I: 9.39±3.22 | ||||||||||

| C: 8.67±3.40 | ||||||||||

| 3M (mean ±SE) | ||||||||||

| I: 4.14±0.34 | ||||||||||

| C: 7.92±0.34 | ||||||||||

| 6M (mean ±SE) | ||||||||||

| I: 3.81±0.40 | ||||||||||

| C: 8.88±0.39 | ||||||||||

| 6M % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| I vs C: 57.1% p=0.001 | ||||||||||

| Owens et al | randomized | n=138 (41 male/102 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C1: 0.1% NaF + | Dental prophylaxis, | PLI: (mean ±SD) | GI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=5 | Low | |

| 1997 | single-blind | 0.76% SMFP | remove plaque and | BL. | BL. | |||||

| parallel, comparison | Age: 18-65 yr. | Negative control | calculus | I: 2.04±0.18 | I: 1.45±0.28 | No information | ||||

| Brush 2 times a day for | C1: 2.04 ±0.24 | C1: 1.38±0.20 | regarding sponsor | |||||||

| PLI= Turesky modification of | I:n= 34 | C2: 0.8% NaF + 0.3% TCN | 18 weeks. | C2: 2.12±0.21 | C2: 1.42±0.25 | |||||

| the Quigley and Hein | C1:n= 33 | 0.75% zn-citrate | C3: 2.13±0.25 | C3: 1.41±0.21 | ||||||

| (Quigley & Hein 1962, | C2:n= 35 | Positive control | ||||||||

| Turesky et al 1970) | C3:n= 36 | 18W | 18W | |||||||

| C3: 0.32% NaF + 0.3% TCN | I: 1.91±0.03 | I: 1.21±0.02 | ||||||||

| GI: Gingival index | England | Positive control | C1: 1.88±0.03 | C1: 1.22±0.02 | ||||||

| (Mandel-Chilton 1977 | C2: 1.86±0.03 | C2: 1.21±0.02 | ||||||||

| modification of the Loe & | C3: 1.83±0.03 | C3: 1.24±0.02 | ||||||||

| Silness (1963) | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | % treatment diff. | |||||||||

| 4 Groups | I: 6.4 | I: 16.6 | ||||||||

| C1:7.8 | C1: 11.6 | |||||||||

| 18 W | C2: 12.3 | C2: 14.8 | ||||||||

| C3: 14.1 | C3: 12.1 | |||||||||

| NS | NS | |||||||||

| Papas et al | randomized | N= 334 | I: 0.454 SnF2 | C: 0.234% NaF + 0.3% TCN | No treatment | BOP (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=106 | Medium | ||

| 2007 | double-blind | Positive control | BL: | |||||||

| parallel | I: n=163 (77 male/86 female) | I: 94.6±19.5 | Sponsored by | |||||||

| 626.2 ±9.36 (40-79) yrs. | C: 88.3±27.9 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| Bleeding on probing (BOP) | ||||||||||

| 1 Yrs.: | ||||||||||

| 2 Yrs. | C: n=171 (76 male/95 female) | I: 7.4±20.8 | ||||||||

| 66.3±9.31 SD (41-80) yrs. | C: 9.6±23.2 | |||||||||

| USA | 2 Yrs.: | |||||||||

| I: 33.5±35.2 | ||||||||||

| C: 32.5±32.7 | ||||||||||

| 2 Yrs. | ||||||||||

| I vs C: 61.1% vs 55.8% NS | ||||||||||

| Perlich et al | randomized | n= 328 | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C: 0.243% NaF | A 3-month pre-test period | PLI: (mean ±SE) | GI: (mean ±SE) | GB: (mean ±SE) | Drop out: n=55 | High |

| 1995 | double-blind | Negative control | where all subjects brushed | BL: | BL: | BL | ||||

| parallel | I: n=154 (51 male/ 103 female) | with 0.243% Sodium | I: 1.94±0.04 | I: 0.68±0.02 | I: 14.43±0.94 | Sponsored by | ||||

| 37.3 (19-69) yrs. | fluoride TP. | C: 1.90±0.04 | C: 0.68±0.02 | C: 16.40±1.03 | Procter & Gamble | |||||

| PLI= Turesky modification of | ||||||||||

| the Quigley and Hein | 3M | 3M | 3M | Identical data as | ||||||

| (Quigley & Hein 1962, | Cl: n=174 (60 male/ 114 female) | I: 1.99 ±0.12 | I: 2 0.43±0.01 | I: 7.23±0.32 | presented in | |||||

| Turesky et al 1970) | 36.5 yr. (19-48) yrs. | C: 2.07±0.12 | C: 0.53±0.01 | C: 10.52±0.47 | McClanahan et al | |||||

| 1997, but | ||||||||||

| GI: (Löe & Siless 1967) | USA | 6M | 6M | 6M | exkluding TCN. | |||||

| I: 2.16±0.13 | I: 0.41±0.01 | I: 5.71±0.39 | ||||||||

| GB: Gingival Bleeding | C: 2.23±0.13 | C: 0.52±0.01 | C: 8.57±0.43 | |||||||

| (no of sites) | ||||||||||

| PLI (Increase) | GI | No of GBI sites: | ||||||||

| I: -0.23 (11.9%) | I: 0.27 (39.7%) | I: 8.7% (60.4) | ||||||||

| C: -0.43 (-22.6%) | C: 0.18 (25%) | C: 7.8% (47.7%) | ||||||||

| 6M - NS | 6M p=0.05 | 6M p=0.05 | ||||||||

| Sharma et al | randomized | n= 114 subjects | I : 0.454% SnF2 | C: 0.234% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Dental prophylaxis, brush | RMNPI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=8 | High | ||

| 2013 | double-blind | Positive control | for at least 1 min 2 | 3W | ||||||

| parallel | I: n= 56 (21 male/39 female) | times/day | I: 0.39 ±0.01 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| 36.4 ±11.8 (21-71) yrs. | C:0.56±0.01 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| RMNPI: Modification of the | ||||||||||

| Navy Plaque index | C: n= 58 (21 male/39 female) | 6W | ||||||||

| (Rustogi et al. 1992) | 38.6 ±13.7 (20-82) yrs. | I: 0.27±0.01 | ||||||||

| C:0.50±0.01 | ||||||||||

| 6W | USA | |||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| I vs C: | ||||||||||

| 3W: 29.7% p=0.0001 | ||||||||||

| 6W: 44.9% p=0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Shearer et al | randomized | n= 110 (male) | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C1: 0.243% NaF + TCN | Scaling and rotplaning | PLI: (mean ±SD) | MGI: (mean ±SD) | Drop out: n=11 | High | |

| 2005 | double-blind | 25-50 yrs. | + Zn-citrate | and oral hygiene | 3W | 3W | ||||

| 3-arm parallel | Positive control | instruction | I: 1.04±0.03 | I: 0.91 ±0.07 | No baseline data | |||||

| I: n= 39 | C1: 1.08±0.03 | C1: 1.07 ±0.09 | ||||||||

| PLI: (Löe 1967) | C1: n= 36 | C2: 0.243% NaF | C2: 1.13±0.03 | C2: 1.43 ±0.07 | No sponser | |||||

| C2: n = 35 | Negative control | |||||||||

| MGI: Modified Gingival Index | I vs CI: NS | I vs C2: p=0.0003 | ||||||||

| (Lobene 1986) | USA | I vs C2: NS | I vs CI: NS | |||||||

| C1 vs C2: NS | C1 vs C2: p=0.01 | |||||||||

| GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index | ||||||||||

| (Saxton 1989) | GBI (mean SD) | |||||||||

| 3W | ||||||||||

| 21 Days | I: 0.33 ±0.03 | |||||||||

| C1: 0.3 ±0.03 | ||||||||||

| C2: 0.51 ±0.03 | ||||||||||

| I vs C2: p=0.0003 | ||||||||||

| I vs C1: NS | ||||||||||

| C1 vs C2: p=0.0003 | ||||||||||

| White et al. | randomized | n= 16 (6 male/10 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF | Treatment period (TP) 1: | DPIA: Plaque % mean ±SD | No drop outs | High | ||

| 2006 | blinded | Negative control | Including toothbrushing | |||||||

| 3-arm cross-over study | 33.2. (24-38) yrs. | with NaF TP | TP1: Plaque coverage: | Sponsored by | ||||||

| 3-treatment period within the | Procter & Gamble | |||||||||

| same group | USA | TP 2: | Pre-brushing: 13.3% ±4.27 | |||||||

| Modified hygiene regimen | Post-brushing: 6.4% ±1.80 | |||||||||

| Digital plaque imaging | was applied using NaF TP | |||||||||

| analysis (DPIA). | including a period of 24 H | TP2: | ||||||||

| of non-brushing | Pre-brushing: 18.4 ±5.97 | |||||||||

| 2W | Post-brushing: 7.3 ±3.64 | |||||||||

| TP 3: | ||||||||||

| 24 H non-brushing | TP3: | |||||||||

| regimen was continued | Pre-brushing: 15.2 ± 6.87 | |||||||||

| using SnF2 + SHMP TP | Post-brushing: 6.8 ±3.52 | |||||||||

| Reduction %: | ||||||||||

| TP3 vs TP1, TP2: 17% | ||||||||||

| Advantage TP3. | ||||||||||

| White 2007 | double-blind | n= 14 | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C.: 0.243% NaF | Dental prophylaxis | DPIA: Morning Pre-Bruch | No drop outs | High | ||

| cross-over | Negative control | performed by subjects | Regrowth % ±SD | |||||||

| 33 yrs. | I: 10.4 ±4.4 | Sponsored by | ||||||||

| Digital plaque imaging | Cl: 13.8 ± 5.5 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||||

| analysis (DPIA) | USA | |||||||||

| Morning Post-Brushing | ||||||||||

| I: 6.2 ± 2.6 | ||||||||||

| C: 6.3 ±3.3 | ||||||||||

| Afternoon Regrowth | ||||||||||

| I: 8.1± 3.9 | ||||||||||

| C: 11.2 ±5.1 | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | ||||||||||

| Morning Pre-Brush | ||||||||||

| I vs C: 24.4 p=0.0002 | ||||||||||

| Moring Post-Brush | ||||||||||

| I vs C 1.7 NS | ||||||||||

| Afternoon Regrowth | ||||||||||

| I vs C: 27.9 p=0.0003 | ||||||||||

| Willumsen et al | double-blind | n= 40 | I: 0.4% SnF2 | C: 0.2% NaF | Before the two periods, | PLI: (mean ±SD) | GI: (mean ±SD) | Excluded =4 | Medium | |

| 2007 | cross-over | Negative control | the subjects had their | BL: (all surfaces) | BL: (all surfaces) | Drop-out= 4 | ||||

| 88.7 (82-98) | teeth professionally | I and C: 1.44 ± 0.48 | I and C: 1.29 ± 0.38 | |||||||

| PLI: (Silness & Löe 1964) | cleaned. | No sponsor | ||||||||

| Norway | 4W: | 4W: | ||||||||

| GI: (Löe & Silness 1963) | I: 1.14± 0.40 | I:1.22± 0.30 | ||||||||

| C: 1.28± 0.34 | Ctrl: 1.22± 0.27 | |||||||||

| 4 W | ||||||||||

| % treatment diff. | % treatment diff. | |||||||||

| I: 20.8 vs. C: 11.1 | I: 7.0 vs. C: 7.0 | |||||||||

| p=0.001 | NS | |||||||||

| Yates et al | randomized | n= 69 /21 days | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C: 0.24% NaF | Professional prophylaxis, | PLI: (mean ±SE) | MGI: (mean ±SE) | GB: (mean ±SE) | Drop-out: n=6 | Low |

| 2003 | double-blind | n= 67 /42 days | Negative control | allocated toothpaste and | For unshielded teeth | For unshielded teeth (that | For unshielded teeth (that | (42 days) | ||

| parallel | a standard toothbrush | (that have been shielded) | have been shielded) | have been shielded) | no data which | |||||

| I: n=36 (7 male/ 29 female) | Oral hygiene Instructions | BL: 0 | I: BL: 1.54±0.07 | I: BL: 0.33±0.04 | group | |||||

| 21 days experimental gingivitis | 33.1 (20-60) yrs. | 21 days:1.50±0.08 | I: 21 days:1.74±0.05 | I: 21 days: 0.62± 0.03 | ||||||

| protocol and a 6 week (42 days) | 42 days: 1.07± 0.08 | I: 42 days: 1.17± 0.08 | I: 42 days: 0.43± 0.03 | No sponsor | ||||||

| home-use protocol | C: n=35 (7 male/ 28 female) | |||||||||

| 33.6 (21-63) yrs. | C: BL: 0 | C: BL: 1.62±0.06 | C: BL: 0.41±0.04 | |||||||

| PLI: (Löe 1967) | 21 days:1.73±0.06 | C: 21 days:1.85±0.05 | C: 21 days: 0.67± 0.04 | |||||||

| United Kingdom | 42 days: 1.05± 0.09 | C: 42 days: 1.25± 0.07 | C: 42 days: 0.49± 0.04 | |||||||

| MGI: Modified gingival index | ||||||||||

| (Lobene et al. 1986) | Reduction: day 21 to day 42. | MGI reduction 21 – 42 day | GB reduction: 21 to 42days. | |||||||

| I: 0.43 vs C: 0.68 | I: 0.57 vs C: 0.60 | I: 0.19 vs C: 0.18 | ||||||||

| GB= Gingival bleeding | I vs C: NS | I vs C: NS | I vs C: NS | |||||||

| Teeth covered by tooth shield | ||||||||||

| For unshielded teeth | For unshielded teeth | For unshielded teeth | ||||||||

| 21 Days /42 Days | (mean ±SE) | (mean ±SE) | (mean ±SE) | |||||||

| I: BL: 0 | I: BL: 1.43± 0.07 | I: BL: 0.29± 0.03 | ||||||||

| 21 days:0.78± 0.06 | I: 21 days: 1.27± 0.07 | I: 21 days: 0.34± 0.03 | ||||||||

| 42 days: 0.81± 0.07 | I: 42 days: 0.95± 0.08 | I: 42 days: 0.37± 0.02 | ||||||||

| C: BL: 0 | C: BL: 1.43± 0.07 | C: BL: 0.34± 0.03 | ||||||||

| 21 days:0.76± 0.07 | C: 21 days: 1.25± 0.06 | C: 21 days: 0.33± 0.03 | ||||||||

| 42 days: 0.77 ± 0.07 | C: 42 days: 1.02± 0.07 | C: 42 days: 0.38± 0.03 | ||||||||

| PLI reduction: B to 42 days. | MGI reduction: B to 42 days. | GB reduction: B to 42 days. | ||||||||

| I: -0.81 vs C: -0.77 | I: 0.48 vs C: 0.41 | I: -0.08 vs C: - 0.0 | ||||||||

| I vs C: NS | I vs C: NS | I vs C: NS | ||||||||

AlF (aluminium fluoride) BL (baseline), I (intervention), C (control), H (Hour) NaF (Sodium fluoride), SnF2 (Stannous fluoride), SnCl (stannous chloride), STP (sodium tripolyphosphate), SHMP (Sodium hexametaphosphate), SMFP (Sodium monofluorophosphate), PHEN (Phenolic essential oils), TCN (Triclosan), TP (Toothpaste), NS (not significant), vs (versus) Zn- citrate (Zink citrate).

The studies included various study population such as patients, students, volunteers or subjects employed at dental product companies. The number of subjects varied greatly, ranging from 14 to 835 subjects. The 21 included studies comprised 3221 subjects. The duration of the studies ranged from 24 h to 2 years. One study had a duration of 2 years [38], 8 studies of 6 months [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46], one study of 4.5 months [47], five studies of 3–12 weeks [48, 49, 50, 51, 52], four studies of 14–17 days [53, 54, 55, 56], and two studies of 24 h [57, 58]. Most test products contained 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP as the active ingredients. One study, however, contained sodium gluconate and two contained zinc citrate. The control dentifrices in 12 studies contained between 0.1% and 0.15% fluoride as sodium fluoride. Eight trials also included 0.3% Triclosan (TCN) one trial included phenolics (Listerine) and Baking soda + Hydrogen peroxide and one trial included Chlorhexidine as a positive control.

Various indices were used to assess the presence and/or amount of plaque at the examinations. Two studies measured the percentage of surfaces harboring plaque in relation to the total number of tooth surfaces. Four studies [40, 41, 51, 52], assessed plaque according to the plaque index [26]; these studies reported a mean percentage reduction of 6.2% (range 1.6%–12%) for the SnF2 dentifrice compared to a negative control. Six studies [42, 43, 44, 45, 46]; used the modified Quigley and Hein Index [25, 27] and reported a mean reduction in plaque of 15.3% (range 3.9%–25.8%) for the SnF2 dentifrice compared to a negative control.

Gingival inflammation was assessed in 15 of the 21 studies (Table 2). Some used more than one index to measure the level of gingival inflammation. The mean reduction in gingival inflammation, registered as mean GI change, was 17.2% (range 5.3%–25.8%) greater in the SnF2 groups than in the sodium fluoride groups The reduction in percentages of sites showing gingival bleeding was 32.4% greater in the SnF2 groups (range 11.6%–72%).

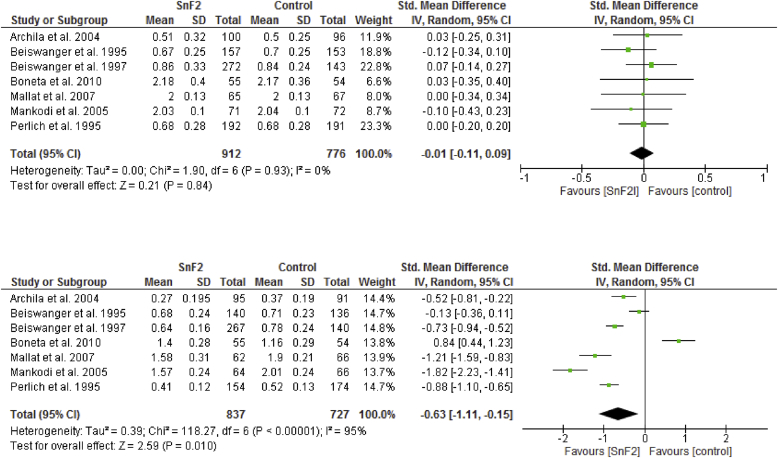

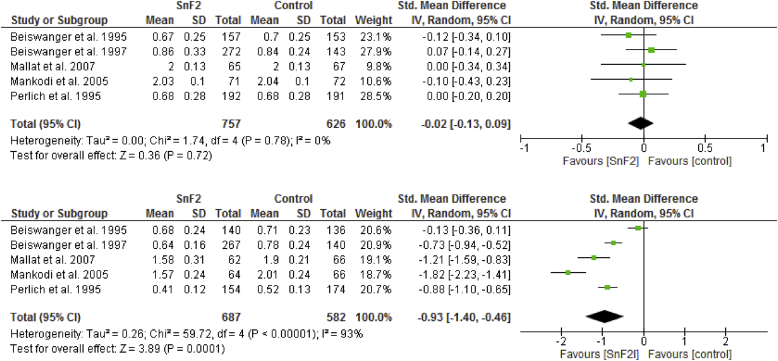

Figure 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis of gingival inflammation and the 6-month studies [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46]. Brushing with SnF2 toothpaste yielded significantly higher reductions in gingival inflammation. The SMD was -0.63 (95% CI: -1.11 to -0.15) with a significant reduction in the SnF2 group (P = 0.010) compared with the controls. When compared with negative controls only, the anti-gingivitis effect of SnF2 had a significant SMD of -0.93 (95% CI: -1.40 to -0.46; P = 0.0001) (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of baseline and after 6 month values (Standardized mean difference: SMD) of the gingivitis indices for the studies using a stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrice compared to control dentifrice (positive and negative controls).

Figure 3.

Forrest plot of baseline and after 6 month values (Standardized mean difference: SMD) of the gingivitis indices for the studies using a stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrice compared to control dentifrice (negative control, NaF).

3.3. Halitosis

Table 4 lists the four included studies on halitosis, which were published between 1998 and 2010. The studies were randomized and had a cross-over [59, 60, 61] or parallel design [33]. They evaluated the effect of either one-time [59] or repeated brushing [33, 60, 61]. The intervention was brushing with a toothpaste containing 0.454% SnF2 alone [33, 59, 60], in combination with sodium fluoride [61], or in combination with tongue brushing [60]. Both single use and repeated exposure reduced breath malodor when using a SnF2 toothpaste in comparison to control products. The studies reported a significant reduction in VSC after single use [33, 61] as well as after cumulative use and overnight readings [33, 59, 60, 61].

Table 4.

Characteristics of included studies on halitosis.

| Authors |

Study design |

Study population |

Intervention (I) |

Control (C ) |

Treatment/ |

Outcome |

Comments |

Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (year) |

Methods |

Number (gender) |

Toothpaste |

Positive/negative |

brushing |

of bias |

||

| Duration |

Age (range) |

|||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| Chen et al | randomized | n=33 (14male/19 female) | I1: 0.454% SnF2 | C1: 0.243% NaF | Brushing three | 24 H | No drop out | High |

| 2010 | examiner-blind | 25 yrs. | negative control | times during 24 H | I1: 93.69 | |||

| crossover | I2: 0.454% SnF2 + | I2: 91.84 | Sponsored by | |||||

| USA | tongue brushing | C2: 0.243% NaF + | Procter & Gamble | |||||

| Breath measurement | tongue brushing | C1: 113.30 | ||||||

| at 24 and 28 H | Positive control | C2: 105.64 | ||||||

| Halimeter (hydrogen | I1 + I2: 92.8 | |||||||

| sulfide, methyl | C1 + C2: 109.9 | |||||||

| mercaptan | ppb)" | |||||||

| 28 H | ||||||||

| I1: 52.98 | ||||||||

| I2: 54.60 | ||||||||

| C1: 66.69 | ||||||||

| C2: 68.72 | ||||||||

| I1 + I2: 53 | ||||||||

| C1 + C2: 66.7 | ||||||||

| Farrell et al | Two RCTs | Healthy adults with | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C: 0.243% NaF | Single day product | Study I (mean ± SD) | No drop out | High |

| 2007 | cross-over double-blind | history of halitosis | negative control | use (2 brushings) | I: 4.59 ± 0.14 | |||

| Breath measurement | C: 4.81 ± 0.14 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| at 24 H | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| Study 1 | Study II (mean ± SD) | |||||||

| Study 1 | n=26 (13 male/13 female) | I: 5.72 ± 0.09 | ||||||

| Halimeter (hydrogen | 38.4 ± 6.7 yrs. | C: 5.94 ± 0.09 | ||||||

| sulfide, methyl | ||||||||

| mercaptan | ppb)" | Study II | ||||||

| n=49 (14 male/35 female) | ||||||||

| Study II | 44.2 ± 12.7 yrs. | |||||||

| Hedonic (9-point scale) | ||||||||

| 5 W | USA | |||||||

| Feng et al | Randomized | n=100 (32 male/68 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + NaF | C I: 0.243% NaF (USA) | Partly supervised | 3 H | No drop out | High |

| 2010 | controlled | 34 (19-62) yrs. | negative control | brushing up to three | I: 88.3 | |||

| single-blind | times | C: 95.7 | Sponsored by | |||||

| crossover | USA (Study I) | C2: 0.321% NaF (China) | Procter & Gamble | |||||

| China (Study II-IV) | negative control | 24 H | ||||||

| Data presented as | I: 140.7 | |||||||

| results from meta- | C: 157.3 | |||||||

| analysis of four | ||||||||

| clinical trials. | 27-28 H | |||||||

| I: 75.2 | ||||||||

| Halimeter VSC | C: 99.6 | |||||||

| Readings after 3-4 H, | ||||||||

| 24 H and 27-28 H | ||||||||

| Gerlach et al | Randomized | n=384 | I: 0.454% SnF2 | CI: 0.243% NaF +5% | Partly supervised | Organoleptic score | 2% drop out | High |

| 1998 | controlled | (79% female/21% male) | pyrophosphate | on examination days | 3/6/8 H | |||

| parallell group | positive control | I: 2.85/3.40/3.99 | Sponsored by | |||||

| 44.5 (18-77) yrs. | CI: 3.09/3.45/4.04 | Procter & Gamble | ||||||

| Fluoride groups | C2:0.24 NaF + | C2: 3.30/3.57/4.01 | ||||||

| Five-day period | USA | 0.30% TCN | C3: 3.23/3.42/4.01 | |||||

| positive control | ||||||||

| Organoleptic scoring | 99/102/104 H | |||||||

| Halimeter VSC (ppb) | C3: bottled distilled | I: 2.90/3.19/3.73 | ||||||

| water | CI: 3.33/3.57/4.10 | |||||||

| Readings after 3, 6 | negative control | C2: 3.43/3.64/4.18 | ||||||

| and 8 H (single use) | C3: 3.54/3.73/4.13 | |||||||

| and 99, 102 and 104 | ||||||||

| H (cumulative use) | ppb | |||||||

| 3/6/8 H | ||||||||

| I: 4.39/3.97/4.09 | ||||||||

| CI: 4.51/3.99/4.19 | ||||||||

| C2: 4.50/4.02/4.18 | ||||||||

| C3: 4.56/4.04/4.20 | ||||||||

| 99/102/104 H | ||||||||

| I: 4.07/3.83/4.00 | ||||||||

| CI: 4.29/4.03/4.16 | ||||||||

| C2: 4.34/4.03/4.29 | ||||||||

| C3: 4.48/4.11/4.29 | ||||||||

BL (baseline), I (intervention), C (control), NaF (Sodium fluoride), SnF2 (Stannous fluoride), TCN (Triclosan), TP (Toothpaste), H (Hours).

3.4. Stain

Table 5 presents the five included studies on stain, which were published between 2005 and 2013 [36,[62], [63], [64], [65]]. The test period varied between 2 and 6 weeks. All studies were controlled, randomized, double-blinded, and parallel-grouped, and represented 488 patients (aged 19–74 yr) with 240 patients in the test groups and 248 in the control groups. In four studies, the test toothpastes contained 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP [36, 62, 63, 65] and were compared with a positive control of 0.243% NaF +0.3% triclosan toothpaste. The fifth study [63] examined a stannous chloride and sodium fluoride toothpaste but had a positive control with only 0.454% SnF2. The overall results showed that the 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP toothpastes and the triclosan controls reduced the Lobene stain index, but at the end of the test periods, no significant differences in stain reducing effect were found. While there were no significant differences in mean Lobene scores between the stannous chloride and the triclosan dentifrices, the toothpaste with only SnF2 had a higher stain score after 5 weeks than at baseline [63].

Table 5.

Characteristics of included studies on stain.

| Authors |

Study design |

Study population |

Intervention (I) |

Control (C ) |

Treatment/ |

Outcome |

Comments |

Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (year) |

Methods |

Number (gender) |

Toothpaste |

Positive/negative |

brushing |

of bias |

||

| Duration |

Age (range) |

|||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| He et al | randomized | Study 1: | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Brushing twice | Study I: | Study I: | High |

| 2007 | double-blind | n=56 (26 male/26 female) | positive control | daily for for 1 min. | BL: I: 2.64, C: 2.45 | Droup-outs= 4 | ||

| parallel group | 6 W: I: 1.05, C: 0.81 | |||||||

| Study 2: | % treatment diff. | Study II: | ||||||

| Lobene stain index | n=58 (19 male/39 female) | I vs C= ns | Droup-outs= 2 | |||||

| 6 W | 30-70 yrs. | Study II: | Sponsored by | |||||

| BL: I: 3.36, C: 3.17 | Procter & Gamble | |||||||

| USA | 6W: I: 0.31, C: 0.15 | |||||||

| % treatment diff. | Equal effect between | |||||||

| I vs C= ns | test and control | |||||||

| He et al | randomized | n=98 (32 male/66 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 | C1: 1450 ppm NaF+ SnCl | Brushing twice | BL: I: 0.42 | Drop-out=2 | High |

| 2010 | double-blind | 19-63 yrs. | positive control | daily for for 1 min. | C1: 0.52, C2: 0.47, | |||

| parallel group | C3: 0.40 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| I: n= 14 | C2: 1450 ppm NaF+ SnCl | Procter & Gamble | ||||||

| Lobene stain index | C1: n= 28 | positive control | 5W: I: 0.80 | |||||

| 1968 | C2: n= 28 | C1: 0.37, C2: 0.40 | The I TP was less | |||||

| C3: n= 28 | C3: 1450 ppm NaF+0.3% TCN | C3: 0.30 | effect | |||||

| 5 W | negative control | |||||||

| USA | % treatment diff. | |||||||

| C1 vs C2 vs C3 = ns | ||||||||

| I vs other 3 groups: | ||||||||

| p<0.0001 | ||||||||

| Nehme et al | randomized | n= 137 | I1: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C= 0.76% MFP | Brushing twice | BL: I1=0.36, I2= 0.32 | Drop-out=6 | High |

| 2013 | double-blind | negative cocntrol | daily for for 1 min. | C=0.30 | ||||

| parallel group | I1:= 21 | I2: 0.454% SnF2 + STP | Sponsored by | |||||

| I2:= 57 | 8W: I1=0.35, I2= 0.28 | GlaxoSmithKline | ||||||

| Lobene stain index | C: n= 59 | C=0.28 | ||||||

| 1968 | Equal effect between | |||||||

| USA | No diff. I vs C | test and control | ||||||

| 8 W | ||||||||

| Schiff et al | randomized | n= 80 (49 male/31 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Brushing twice | BL: I=0.0, C=0.0 | No drop-out | High |

| 2005 | double-blind | 27.5 (19-45) yrs. | positive control | daily for for 1 min. | ||||

| parallel group | 6M: I=0.02, C=0.0 | Sponsored by | ||||||

| I= 40 | No diff. BL vs 6M | Procter & Gamble | ||||||

| Lobene stain index | C= 40 | |||||||

| 1968 | Equal effect between | |||||||

| USA | test and control | |||||||

| 6 M | ||||||||

| Terézhalmy et al | randomized | Study 1: | Study I: | Study I: | Brushing twice | Study 1: | No drop-out | High |

| 2007 | double-blind | n=29 (12 male/17 female) | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | C: 0.243% NaF + 0.3% TCN | daily for for 1 min. | BL: I=1.06, C=1.05 | ||

| parallel group | 50.4 (21-62) yrs. | positive control | 2W: I=0.57, C=0.53 | Sponsored by | ||||

| Study II | I vs C: ns | Procter & Gamble | ||||||

| Lobene stain index | Study 2: | I: 0.454% SnF2 + SHMP | Study II: | |||||

| 1968 | n=30 (17 male/13 female) | C: 0.243% NaF + 0.3% TCN | Study 2: | Equal effect between | ||||

| 47.6 (33-59) yrs. | positive conrol | BL: I=1.68, C=1.48 | test and control | |||||

| 2 W | 2W: I=1.41, C=1.40 | |||||||

| USA | I vs C: ns | |||||||

BL (baseline), I (intervention), C (control), NaF (Sodium fluoride), SnF2 (Stannous fluoride), SnCl (stannous chloride), STP (sodium tripolyphosphate), SHMP (Sodium hexametaphosphate), MFP (monofluorphosphate) TCN (Triclosan), TP (Toothpaste), NS (not significant), vs (versus).

4. Discussion

In the present review, toothpastes containing SnF2 have been proven to have preventive and therapeutic effects against dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis and stain. Comparisons with the effects of other toothpastes on these conditions favored a toothpaste containing SnF2. However, the meta-analyses on gingivitis showed a substantial heterogeneity in the results of the individual randomized trials.

4.1. Dental calculus

The significant reduction in calculus formation that occurred after 6 months of testing a toothpaste containing SnF2 and a calcium phosphate-mineralization inhibitor (SHMP) compared with other toothpastes indicated a beneficial effect. Due to their hardness, calculus deposits can only be removed by scaling and polishing the teeth. SHMP acts by reducing the rate and extent of mineralization, thereby reducing calculus build-up. In the Winston et al. [37] study, home-based and unsupervised use of a SnF2 dentifrice during normal hygiene procedures effectively inhibited calculus regardless of the baseline levels of calculus. The significant anti-calculus efficacy that was observed is further evidence of the capacity of SHMP to interfere with calculus formation.

4.2. Dental plaque and gingivitis

A recent systematic review reported that use of a dentifrice with tooth brushing had a weak additional inhibitory effect on plaque regrowth when compared with tooth brushing alone [66]. The present systematic review demonstrated an increased plaque-reducing effect of a toothpaste containing SnF2 compared with other toothpastes. Depending on the plaque index used and study duration, the reduction in dental plaque ranged from 1.6% to 25.8%. The effect was observed in both 24-hour as well as 6-month studies, indicating that both short- and long-term use of a SnF2 dentifrice has a plaque inhibitory effect. Although long-term studies are desirable, studies of more than 6 months require a degree of compliance among participants that is sometimes difficult.

The present review found evidence for both direct and indirect effects on gingivitis development of brushing with a SnF2 dentifrice. The indirect effect refers to the amelioration of gingivitis due to plaque reduction; the direct effect refers to a possible anti-inflammatory action, which both triclosan and SnF2 have demonstrated, independent of how they affect bacteria [67]. The meta-analysis of the 6-month studies showed that stabilized SnF2 significantly reduced gingival inflammation compared to positive and negative control dentifrices. The results of the present review are in line with the Paraskevas et al. [68] study, which reported that dentifrice containing SnF2 reduced dental plaque as well as gingivitis.

4.3. Halitosis

The four papers [33, 59, 60, 61] evaluating the effect of a SnF2 toothpaste on halitosis vary in number of exposures and in time point for measurement after exposure to the toothpaste. The overall picture, however, is that SnF2 reduces the level of halitosis to a larger extent than comparative toothpaste products. The data are based on the combined level of hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan, representing the VSCs produced by gram negative anaerobes most commonly found in bad breath. Other compounds, such as dimethyl sulfide and fatty acids, may also contribute [17]. The four papers reported limited information on the volunteers, but subjects with medical and oral conditions that could interfere with study measurements seem to have been excluded. The exact mechanism behind the positive findings is not fully known, but the antimicrobial effect of the SnF2 compound is believed to play a significant role and also the effect of zinc in those toothpastes containing zinc citrate.

4.4. Stain

Several toothpastes on the market claim better stain-reducing capacities compared to conventional toothpastes. Historically, this effect has been due to the abrasive ingredient in the toothpastes. The studies in the present review have shown that a SnF2 + SHMP toothpaste plays an important role in stain reduction. All studies demonstrated that the SnF2 + SHMP toothpaste exhibited a stain-reducing effect equal to that of various control toothpastes. Clinical studies have shown that use of the polypyrophosphate formulation SHMP as the sole active ingredient in a toothpaste reduces the development of stain [69]. SHMP has the capacity to interact with stained pellicle films, remove the stain material, and then prevent adsorption of new chromogens by leaving a protective coating on the tooth surface [69].

4.5. Clinical relevance

Several aspects affect the clinical significance of the findings of the present review. For example, other ingredients in a toothpaste may contribute to the effects of a toothpaste on dental plaque, gingivitis, stains, and to some extent halitosis. An abrasive ingredient is necessary to remove plaque and biofilm [70, 71], so modern toothpastes often contain between 30% and 40% abrasives, which are usually various shapes and sizes of silica particles. Other aspects to be considered are the varying lengths and designs of the studies as well as the different indices used to measure results, which could well influence outcomes. This was especially obvious in the plaque and gingivitis studies; in the studies on stain and calculus, the small number of articles also potentially affected clinical significance.

To conclude that the favorable results that the present review found are exclusively related to SnF2 content, identical toothpastes with and without SnF2 must be compared. Other factors, such as the unique silica content of the SnF2 toothpaste, may contribute to the positive findings.

4.6. Bias

Analysis of the included papers followed SBU recommendations for quality assessment. Many of the studies were sponsored by the manufacturers or had authors employed by a toothpaste manufacturer. Although the studies were carefully executed and presented evidence of good quality, the involvement or support of the manufacturers could be regarded as a factor in potential bias. Additional studies that are less dependent on commercial interests and performed by independent researchers are needed. Studies with similar designs including comparable test and control products are necessary for conclusive findings.

5. Conclusion

The present review found that stabilized SnF2 toothpaste had a positive effect on the reduction of dental calculus build-up, dental plaque, gingivitis, stain and halitosis. A tendency towards a more pronounced effect than using toothpastes not containing SnF2 was found, though the results of the individual trials in the meta-analyses showed a substantial heterogeneity. However, a new generation of well conducted randomized trials are needed to further support these findings.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Magdalena Svanberg and Klas Moberg, librarians at Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden, for their assistance with the literature search. We also thank Helena Domeij, DDS, PhD, and the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment for Social Service for assistance with the meta-analyses.

References

- 1.Beikler T., Flemmig T.F. Oral biofilm-associated diseases: trends and implications for quality of life, systemic health and expenditures. Periodontol. 2000. 2011;55(1):87–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murakami S., Mealey B.L., Mariotti A., Chapple I.L.C. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S17–s27. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albandar J.M. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2005;49(3):517–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.003. v-vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trombelli L., Farina R., Silva C.O., Tatakis D.N. Plaque-induced gingivitis: case definition and diagnostic considerations. J. Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S46–S73. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith R.N., Lath D.L., Rawlinson A., Karmo M., Brook A.H. Gingival inflammation assessment by image analysis: measurement and validation. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2008;6(2):137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jepsen S., Blanco J., Buchalla W., Carvalho J.C., Dietrich T., Dorfer C., Eaton K.A., Figuero E., Frencken J.E., Graziani F., Higham S.M., Kocher T., Maltz M., Ortiz-Vigon A., Schmoeckel J., Sculean A., Tenuta L.M., van der Veen M.H., Machiulskiene V. Prevention and control of dental caries and periodontal diseases at individual and population level: consensus report of group 3 of joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S85–s93. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nightingale K.J., Chinta S.K., Agarwal P., Nemelivsky M., Frisina A.C., Cao Z., Norman R.G., Fisch G.S., Corby P. Toothbrush efficacy for plaque removal. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2014;12(4):251–256. doi: 10.1111/idh.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards D. The effectiveness of interproximal oral hygiene aids. Evid. Based Dent. 2018;19(4):107–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratcliff P.A., Johnson P.W. The relationship between oral malodor, gingivitis, and periodontitis. A review. J. Periodontol. 1999;70(5):485–489. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Leeuwen M., Rosema N., Versteeg P.A., Slot D.E., Hennequin-Hoenderdos N.L., Van der Weijden G.A. Effectiveness of various interventions on maintenance of gingival health during 1 year - a randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017;15(4):e16–e27. doi: 10.1111/idh.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jepsen S., Deschner J., Braun A., Schwarz F., Eberhard J. Calculus removal and the prevention of its formation. Periodontol. 2000. 2011;55(1):167–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akcali A., Lang N.P. Dental calculus: the calcified biofilm and its role in disease development. Periodontol. 2000. 2018;76(1):109–115. doi: 10.1111/prd.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang N.P., Berglundh T. Periimplant diseases: where are we now?--Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva M.F., Leite F.R.M., Ferreira L.B., Pola N.M., Scannapieco F.A., Demarco F.F., Nascimento G.G. Estimated prevalence of halitosis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018;22(1):47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erovic Ademovski S. Department of Periodontology, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University; Malmö: 2017. Treatment of Intra-oral Halitosis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bicak D.A. A current approach to halitosis and oral malodor- A mini review. Open Dent. J. 2018;12:322–330. doi: 10.2174/1874210601812010322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Geest S., Laleman I., Teughels W., Dekeyser C., Quirynen M. Periodontal diseases as a source of halitosis: a review of the evidence and treatment approaches for dentists and dental hygienists. Periodontol. 2000. 2016;71(1):213–227. doi: 10.1111/prd.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelsson P., Nystrom B., Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 30 years of maintenance. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2004;31(9):749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapple I.L., Van der Weijden F., Doerfer C., Herrera D., Shapira L., Polak D., Madianos P., Louropoulou A., Machtei E., Donos N., Greenwell H., Van Winkelhoff A.J., Eren Kuru B., Arweiler N., Teughels W., Aimetti M., Molina A., Montero E., Graziani F. Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015;42(Suppl 16):S71–S76. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muhler J.C., Radike A.W., Nebergall W.H., Day H.G. The effect of a stannous fluoride-containing dentifrice on caries reduction in children. J. Dent. Res. 1954;33(5):606–612. doi: 10.1177/00220345540330050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiff T.G. The effect on calculus deposits of a dentifrice containing soluble pyrophosphate and sodium fluoride. A 3-month clinical study. Clin. Prev. Dent. 1986;8(3):8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White D.J., Gerlach R.W. Anticalculus effects of a novel, dual-phase polypyrophosphate dentifrice: chemical basis, mechanism, and clinical response. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2000;1(4):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H., Segreto V., Baker R., Vastola K., Ramsey L., Gerlach R. Anticalculus efficacy and safety of a novel whitening dentifrice containing sodium hexametaphosphate: a controlled six-month clinical trial. J. Clin. Dent. 2002;13(1):25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volpe A.R., Manhold J.H., Hazen S.P. In vivo calculus assessment. I. A method and its examiner reproducibility. J. Periodontol. 1965;36:292–298. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quigley G.A., Hein J.W. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1962;65:26–29. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silness J., Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Ii. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turesky S., Gilmore N.D., Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J. Periodontol. 1970;41(1):41–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loe H., Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1963;21:533–551. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J. Periodontol. 1967;38(6):610–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobene R.R., Weatherford T., Ross N.M., Lamm R.A., Menaker L. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin. Prev. Dent. 1986;8(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxton C.A., van der Ouderaa F.J. The effect of a dentifrice containing zinc citrate and Triclosan on developing gingivitis. J. Periodontal. Res. 1989;24(1):75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ainamo J., Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int. Dent. J. 1975;25(4):229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerlach R.W., Hyde J.D., Poore C.L., Stevens D.P., Witt J.J. Breath effects of three marketed dentifrices: a comparative study evaluating single and cumulative use. J. Clin. Dent. 1998;9(4):83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobene R.R. Effect of dentifrices on tooth stains with controlled brushing. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1968;77(4):849–855. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1968.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services . 2018. Assessment of Methods in Health Care: A Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiff T., Saletta L., Baker R.A., He T., Winston J.L. Anticalculus efficacy and safety of a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2005;26(9 Suppl 1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winston J.L., Fiedler S.K., Schiff T., Baker R. An anticalculus dentifrice with sodium hexametaphosphate and stannous fluoride: a six-month study of efficacy. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2007;8(5):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papas A., He T., Martuscelli G., Singh M., Bartizek R.D., Biesbrock A.R. Comparative efficacy of stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice and sodium fluoride/triclosan/copolymer dentifrice for the prevention of periodontitis in xerostomic patients: a 2-year randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2007;78(8):1505–1514. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Archila L., Bartizek R.D., Winston J.L., Biesbrock A.R., McClanahan S.F., He T. The comparative efficacy of stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice and sodium fluoride/triclosan/copolymer dentifrice for the control of gingivitis: a 6-month randomized clinical study. J. Periodontol. 2004;75(12):1592–1599. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beiswanger B.B., Doyle P.M., Jackson R.D., Mallatt M.E., Mau M., Bollmer B.W., Crisanti M.M., Guay C.B., Lanzalaco A.C., Lukacovic M.F. The clinical effect of dentifrices containing stabilized stannous fluoride on plaque formation and gingivitis--a six-month study with ad libitum brushing. J. Clin. Dent. 1995;6(Spec No):46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beiswanger B.B., McClanahan S.F., Bartizek R.D., Lanzalaco A.C., Bacca L.A., White D.J. The comparative efficacy of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice, peroxide/baking soda dentifrice and essential oil mouthrinse for the prevention of gingivitis. J. Clin. Dent. 1997;8(2 Spec No):46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boneta A.E., Aguilar M.M., Romeu F.L., Stewart B., DeVizio W., Proskin H.M. Comparative investigation of the efficacy of triclosan/copolymer/sodium fluoride and stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate/zinc lactate dentifrices for the control of established supragingival plaque and gingivitis in a six-month clinical study. J. Clin. Dent. 2010;21(4):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mallatt M., Mankodi S., Bauroth K., Bsoul S.A., Bartizek R.D., He T. A controlled 6-month clinical trial to study the effects of a stannous fluoride dentifrice on gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2007;34(9):762–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mankodi S., Bartizek R.D., Winston J.L., Biesbrock A.R., McClanahan S.F., He T. Anti-gingivitis efficacy of a stabilized 0.454% stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005;32(1):75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClanahan S.F., Beiswanger B.B., Bartizek R.D., Lanzalaco A.C., Bacca L., White D.J. A comparison of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice and triclosan/copolymer dentifrice for efficacy in the reduction of gingivitis and gingival bleeding: six-month clinical results. J. Clin. Dent. 1997;8(2 Spec No):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perlich M.A., Bacca L.A., Bollmer B.W., Lanzalaco A.C., McClanahan S.F., Sewak L.K., Beiswanger B.B., Eichold W.A., Hull J.R., Jackson R.D. The clinical effect of a stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice on plaque formation, gingivitis and gingival bleeding: a six-month study. J. Clin. Dent. 1995;6(Spec No):54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owens J., Addy M., Faulkner J. An 18-week home-use study comparing the oral hygiene and gingival health benefits of triclosan and fluoride toothpastes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997;24(9 Pt 1):626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerlach R.W., Amini P. Randomized controlled trial of 0.454% stannous fluoride dentifrice to treat gingival bleeding. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2012;33(2):134–136. 138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma N., He T., Barker M.L., Biesbrock A.R. Plaque control evaluation of a stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice compared to a triclosan dentifrice in a six-week trial. J. Clin. Dent. 2013;24(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shearer B., Hall P., Clarke P., Marshall G., Kinane D.F. Reducing variability and choosing ideal subjects for experimental gingivitis studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005;32(7):784–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willumsen T., Solemdal K., Wenaasen M., Ogaard B. Stannous fluoride in dentifrice: an effective anti-plaque agent in the elderly? Gerodontology. 2007;24(4):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yates R.J., Shearer B.H., Morgan R., Addy M. A modification to the experimental gingivitis protocol to compare the antiplaque properties of two toothpastes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003;30(2):119–124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellamy P.G., Jhaj R., Mussett A.J., Barker M.L., Klukowska M., White D.J. Comparison of a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice and a zinc citrate dentifrice on plaque formation measured by digital plaque imaging (DPIA) with white light illumination. J. Clin. Dent. 2008;19(2):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bellamy P.G., Khera N., Day T.N., Barker M.L., Mussett A.J. A randomized clinical trial to compare plaque inhibition of a sodium fluoride/potassium nitrate dentifrice versus a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2009;10(2):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bellamy P.G., Khera N., Day T.N., Mussett A.J., Barker M.L. A randomized clinical study comparing the plaque inhibition effect of a SnF2/SHMP dentifrice (blend-a-med EXPERT GUMS PROTECTION) and a chlorhexidine digluconate dentifrice (Lacalut Aktiv) J. Clin. Dent. 2009;20(2):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White D.J. Effect of a stannous fluoride dentifrice on plaque formation and removal: a digital plaque imaging study. J. Clin. Dent. 2007;18(1):21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White D.J., Kozak K.M., Gibb R., Dunavent J., Klukowska M., Sagel P.A. A 24-hour dental plaque prevention study with a stannous fluoride dentifrice containing hexametaphosphate. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2006;7(3):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barnes V.M., Richter R., DeVizio W. Comparison of the short-term antiplaque/antibacterial efficacy of two commercial dentifrices. J. Clin. Dent. 2010;21(4):101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farrell S., Barker M.L., Gerlach R.W. Overnight malodor effect with a 0.454% stabilized stannous fluoride sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2007;28(12):658–661. quiz 662, 671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen X., He T., Sun L., Zhang Y., Feng X. A randomized cross-over clinical trial to evaluate the effect of a 0.454% stannous fluoride dentifrice on the reduction of oral malodor. Am. J. Dent. 2010;23(3):175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]