Abstract

Purpose

Missing data commonly occur in cancer clinical trials (CCT) and may hinder the search for alternative trial endpoints. We consider reasons for missing tumor measurement (TM) data in CCT and how missing TM data are typically handled. We explore the potential impact of missing TM data on predictive ability of a set of TM-based endpoints.

Methods

Literature review identifies reasons for and approaches to handling missing TM data. Data from 3 actual clinical trials were used for illustration. A sensitivity analysis of the potential impact of missing TM data was performed by comparing overall survival (OS) predictive ability of alternative endpoints using observed and imputed data.

Results

Reasons for missing TM data in CCT are presented, based on the literature review and the three trials. Although missing TM data impacted individual objective status (e.g. 12-week status changed for 53% of patients in one imputation set), it surprisingly only minimally impacted endpoint predictive ability (e.g. median c-indices of 500 imputed datasets ranged from 0.566 to 0.570 for N9741, 0.592–0.616 for N9841, and 0.542–0.624 for N0026).

Conclusion

By understanding the reasons for missingness, we can better anticipate them and minimize their occurrence. Our preliminary analysis suggests missing TM data may not impact endpoint predictive ability, but could impact objective response status classification; however these findings require further validation. With response status accepted as an important phase II endpoint in the development of new cancer therapies (including immunotherapy), we urge that in CCT complete TM data collection and adherence to protocol-defined disease evaluation as closely as possible be a priority.

Keywords: Missing data, Phase II, Tumor measurement-based endpoints, Cancer trials

1. Introduction

Phase III cancer clinical trials for solid tumors suffer from high failure rates, i.e. negative trial results (e.g. 50–60% [1]). One possible explanation for this high failure rate is the choice of endpoints used in the earlier phase II trials. Specifically, multiple studies have suggested that Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)-based tumor response [2,3], the primary endpoint in most (single-arm) phase II trials, is a poor predictor of overall survival (OS), the primary endpoint in phase III trials. Consequently, alternative phase II tumor measurement (TM)- based endpoints have been explored [ [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]; see Appendix A1]. Missing data are an unfortunate reality in most clinical trials [11]. Not only do they compromise inference from clinical trials [12], but they might also compromise the development of new, effective therapies by leading to underpowered studies and bias towards the null. The clinical implications are serious in any oncologic setting, but especially in those where treatment options are limited, cure rates are low, and outcomes are poor such as in pancreatic cancer (where overall 5-year survival rates are as low as 8.5%) or liver and biliary cancers (18.1%) [13]. Studies which evaluate alternative phase II endpoints utilize data from real clinical trials, but do not necessarily address the missing TM data challenges, which in turn might impact assessment of the OS predictive ability of those alternate TM-based endpoints. That is, missing TM data may compromise the identification of alternative TM-based Phase II endpoints that better predict overall survival (OS) outcomes in, and therefore the success of, a subsequent Phase III trial.

In light of these, this article considers the reasons for missing TM data in cancer clinical trials practice; how missing TM data are typically handled in the evaluation of alternative TM-based endpoints; and the potential impact of missing TM data on OS predictive ability of alternative TM-based endpoints. We discuss the first two points based on a review of the literature and investigate the third through a case study.

2. How missing TM data arise in cancer clinical trials practice

Many cancer clinical trials follow patients for a long time after they are off protocol treatment to assess long-term survival outcomes. Several data elements, including tumor burden, are collected and assessed longitudinally while the patient is on active protocol treatment. Specifically, trials for solid tumor diseases typically use RECIST to measure tumor burden and response to therapy [2,3]. This requires measuring individual tumor lesions based on a protocol-defined assessment schedule. For example, the protocol may specify that measurements be taken at baseline and every 6–8 weeks while on protocol treatment. Moreover, there are distinct criteria and repeat assessments required for confirmation of a complete (CR) or partial (PR) response, as well as for the documentation of disease progression (PD). Such a resource-intensive follow-up schedule is important for monitoring tumor response to treatment but is also subject to missed, incorrectly timed or inaccurate measurements. We briefly classify three of the common reasons for missing data in cancer clinical trials next.

First, a missing lesion measurement occurs when the target lesion is not measured at a required assessment (i.e. inconsistent measuring) due to a number of reasons, e.g. image quality, inability to measure if not captured on the imaging study, data acquisition or data error etc. Second, a missing assessment refers to when no measurements are recorded on any lesion at a required assessment. This scenario typically arises from missed patient visits. Third, in some cases, multiple (potentially conflicting) measurements are recorded for the same lesion at the same required assessment, likely from different imaging modalities utilized for the assessment or from multiple readers. We consider the third case as a missing data problem because it is not always clear which is the accurate measurement that needs to be utilized in analyzing the tumor burden trajectory for the individual patient. Note that in the trials we analyzed in this paper, we only encountered missingness from the first two reasons.

3. How missing TM data are currently handled in the evaluation of alternative tm-based endpoints

According to RECIST guidelines, the analysis plan for a clinical trial must address how missing data/measurements will be handled in determination of response or progression. However, there is no standard method for how they are to be handled. Furthermore, in the search for alternative TM-based phase II endpoints (see Appendix A1), typically based on secondary analyses, there is no standard practice either. For example, a literature review suggests that in assessing alternative endpoints some authors adopt a complete-case type analysis (e.g. Suzuki et al. [7], Mandrekar et al. [9], and An et al. [10]), while others do not mention how the missing TM data were handled (e.g. Claret et al. [6]). Ignoring missing TM data may yield biased results. Attempts to address missing TM data issues would typically require statistically sophisticated models (e.g. joint model, time-dependent model or a random effects lesion-specific model) that can flexibly handle missing data, but such models may be difficult to interpret clinically. In contrast, the appeal of certain simple endpoints from, e.g. Suzuki et al. [7], Mandrekar et al. [9], An et al. [10], and Claret et al. [6] (see also Appendix A1) is that they are easy to calculate and are clinically relevant. Thus, in the search for alternative TM-based endpoints in the presence of missing TM data, we are faced with meeting two goals: an endpoint that is conducive for widespread clinical use and one that appropriately accounts for missing data. These goals are not immediately congruent, and the literature suggests emphasis has been placed on the former.

4. Impact of missing TM data on OS predictive ability of endpoints: a case study

We explore the potential impact of missing data on the overall survival (OS) predictive ability of the TM-based endpoints developed in Refs. [9,10]. As a secondary analysis, we also explore the change in classification of objective status (complete response/CR, partial response/PR, stable disease/SD, or progression/PD). The endpoints we considered include two categorical endpoints – trichotomous response (CR/PR vs. SD vs. PD) and disease control rate (CR/PR/SD vs. PD) from Ref. [8]; and two continuous endpoints – relative change in measurements from baseline to 6 weeks and 6–12 weeks, and absolute change in measurements between the same pairs of endpoints from Ref. [10] (see Appendix A1). These alternative endpoints offered no statistically significant improvement in OS prediction compared to the standard RECIST dichotomous response (i.e. CR/PR vs. SD/PD) in Refs. [8,9]. All analyses in Refs. [9,10] were based on observed TM data; the missing data, which we address in this current work, are described in the next section. We conduct a sensitivity analysis by imputing the missing measurement data and comparing results before imputation (i.e. using observed data only) and after imputation (i.e. augmenting observed data with imputed missing data) using data from 3 Alliance/North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) trials. The data from these 3 trials were previously used to compare the continuous versus categorical TM-based endpoints [ [14]; see also Appendix A1]. We selected these trials mainly for illustrative purposes and expect that the general findings would be similar for other clinical trials data sources.

4.1. Data description

To investigate the potential impact of missing measurement data on the OS predictive ability of these alternative TM-based endpoints [9–10; see also Appendix A1], we conducted a sensitivity analysis using data from three actual Alliance/NCCTG cancer clinical trials: a phase III randomized study of IFL (bolus 5-fluorouracil [5-FU], leucovorin [LV], irinotecan), FOLFOX4 (bolus and infusional 5-FU plus oxaliplatin), and IROX (irinotecan and oxaliplatin) as first line therapy for advanced colorectal cancer (N9741 [15]); a phase III randomized study of irinotecan vs. FOLFOX4 as second line therapy for advanced colorectal cancer (N9841 [16]); and a phase II first line pemetrexed plus gemcitabine study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (N0026 [17]). Both N9841 and N0026 utilized the RECIST criteria version 1.0 for collection and assessment. N9741 was activated prior to RECIST and instead collected and assessed tumor measurements according to WHO criteria. Thus, for N9741, to be in line with RECIST criteria, which requires uni-dimensional measurements rather than bi-dimensional under WHO criteria, we adopted a uni-dimensional approach and used the maximum of the bi-dimensional measurements recorded for each lesion in our analysis. In our analysis, to be consistent with the current standard and to be able to compare across different trials, we used RECIST 1.1 (Appendix A2) to recalculate the objective response with the following modifications. We used data from only up to 5 target lesions without considering non-measurable lesions, as these did not have any numerical measurements associated with them. Because the original clinical datasets did not contain a variable indicating appearance of new lesions, we derived such a variable based on the TM data. Specifically, a measurable lesion that was not recorded at baseline and appeared later at a post-baseline assessment was considered a new lesion, and thus representing progressive disease (PD). Consequently, the objective status summaries in this article may differ slightly from those in the original published studies. The details of the trials and the disease assessment schedules have been published previously [[15], [16], [17]].

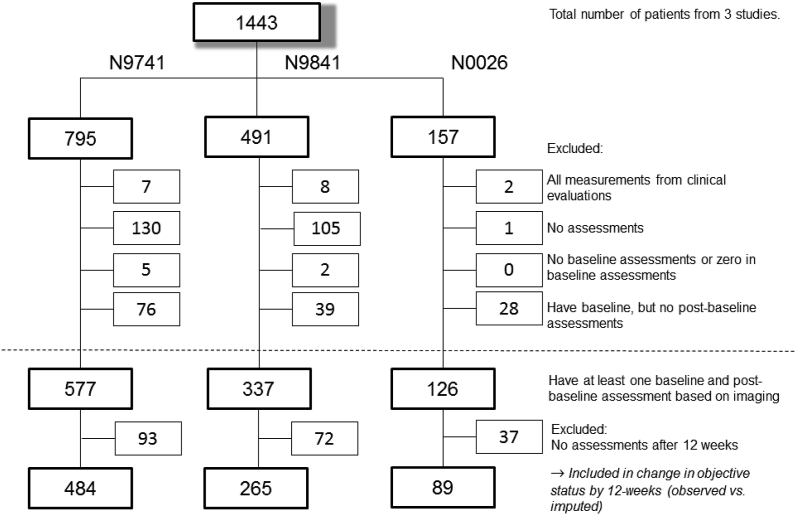

4.2. Analysis dataset preparation

The initial enrollments to the three trials were 795, 491, and 157 patients for N9741, N9841, and N0026, respectively. Patients were excluded from all analyses if: (1) all their measurements were from clinical evaluations only; (2) they had no assessments at all; (3) they had no baseline assessments or “0” for baseline assessments; or (4) they had baseline, but no post-baseline assessments (Fig. 1). That is, to be included in analysis, patients must have had at least one measurable lesion at baseline and one imaging-based assessment post-baseline. A total of 577, 337, and 126 patients from N9741, N9841, and N0026, respectively, fulfilled these initial criteria.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram for observed data in the case study across all 3 trials1.

1Above horizontal dotted line: exclusions due to missing data for reasons as stated. Below horizontal dotted line: additional exclusion due to no assessments after 12 weeks. See Appendix A3 for trial-specific CONSORT diagrams for categorical endpoint and continuous endpoint analyses using observed and imputed datasets.

Tumor measurements from the 6- and 12-week assessments were required to calculate the TM-based endpoints from [9–10; see also Appendix A1]. Although the scan schedule in the original clinical trial required image-based assessments at 6- and 12-week post-baseline, the actual measurements do not align perfectly with the protocol. Therefore, if multiple assessments occurred within a 2-week window around the scheduled assessment (i.e. 4–8 weeks or 10–14 weeks), we took the assessments that were closest to 6- and 12-weeks with the most complete set of tumor measurements to be the 6- and 12-week measurements. Patients with no assessments after 12 weeks were excluded, consistent with our earlier published work [e.g. 9–10]. Most of these patients progressed, died, or initiated alternative anti-cancer therapy before 12 weeks; hence, no further evaluation was conducted after 12 weeks. A total of 484, 265 and 89 patients from N9741, N9841, and N0026, respectively, remained (Fig. 1).

For the analysis of the categorical endpoints [9; see also Appendix A1], in order to calculate the categorical endpoint, patients were additionally screened and included if they were alive and progression-free prior to 12-weeks and had assessments at 12 weeks (±2 weeks). For the analysis of the continuous endpoints [9; see also Appendix A1], patients were additionally screened and included if they were alive and progression-free prior to 12-weeks and additionally had assessments at both 6 and 12 weeks (±2 weeks). In order to use one consistent response criteria across the three studies, we recalculated objective status using RECIST 1.1. It is worth mentioning that because of this recalculation (see Appendix A2), there are patients who progressed at 6-weeks after the recalculation even though in the original trials they were deemed suitable (i.e. did not progress) to continue protocol treatment.

4.3. Missing data evaluation

Patients in these 3 trials had missing data for one of the following 3 distinct reasons: (1) missing data due to inconsistently measured (target) lesions; (2) missing data due to a missed assessment of target lesions; or (3) a combination of (1) and (2).

One set of analyses was conducted on the observed data only (henceforth referred to as “observed”) and another set on observed data augmented with imputed missing data (henceforth, “imputed”). Analyses on the observed dataset used all-available measurements (as described in Appendix A4). Specifically, in the case of inconsistently measured lesions, the sums of lesions were based on differing numbers of lesions at each assessment. Following Wang et al. (2009) [18], we do not use a formal imputation approach and instead use an empirical model to simulate (hereafter, “impute”) measurement data that are otherwise missing. We use a non-linear mixed effects model similar to Wang et al. [18], using the R package brms [19], which adopts a Bayesian approach. The model includes parameters for baseline tumor size, exponential-decay (i.e. tumor shrinkage), and linear tumor growth. See Appendix A5 for more details of the model parameters and estimates. Unlike Wang et al. [18], who modeled the sum of lesions, we modeled each individual lesion and estimated the model parameters based on all available lesion measurements. Missing lesion measurements – either due to inconsistent measuring and/or to a missed assessment – were imputed using the model parameter estimates (see Appendix A5 for the parameter estimates and imputation steps). Original, non-missing, measurements for any lesion were retained; imputations were made only for missing measurements. As a form of model assessment, we created 500 imputed datasets, each having a different randomization seed.

For each of the 500 imputed datasets, we re-calculated the objective status (CR, PR, SD, or PD) using RECIST 1.1 (see Appendix A4), for each patient at each cycle. Since each imputed dataset would have different imputed values, there are different numbers of patients who would be considered as progressed prior to 12 weeks. Since progression prior to 12-weeks is an exclusion criterion for categorical and continuous endpoints, the final dataset used to calculate the endpoints may be different due to differing numbers of patients progressing prior to 12 weeks. We subsequently re-fit the Cox models of OS using the categorical and the continuous endpoints from Refs. [9,10] (see also Appendix A1), adjusted for the average baseline tumor size, and calculated the three statistical measures of predictive ability used in Ref. [10] – concordance-index (c-index [20]), Hosmer-Lemeshow-type statistic [21], and Bayesian Information Critiera (BIC). More details on these measures can be found in Appendix A6. The results from using these imputed datasets were compared with those from using the observed dataset.

4.4. Results

In N9741, N9841, and N0026, respectively, 62%, 66%, and 56% of patients had some missing data for any of the three reasons stated above. The distribution of the missing data reasons across patients is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of missing data reasons among patients with at least one baseline and post-baseline assessment based on imaging and at least one assessment after 12 weeks.

| Number of patients (% within study) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| N9741 | N9841 | N0026 | |

| No missing data (complete data) | 182 (38%) | 90 (34%) | 39 (44%) |

| Missing data, reason | |||

| (1) Inconsistently measured lesions | 18 (4%) | 5 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| (2) Missed assessment | 276 (57%) | 168 (63%) | 48 (54%) |

| (3) Combination of (1) and (2) | 8 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Total | 484 (100%) | 265 (100%) | 89 (100%) |

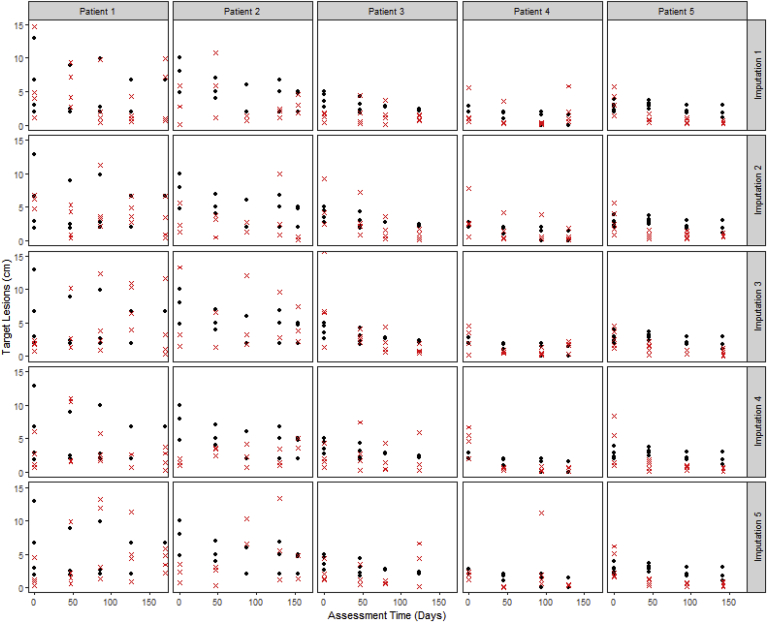

A visual comparison of the observed tumor measurements versus the imputed measurements for a sample of patients who had at least one measurement imputed (Fig. 2) suggests that the imputed measurements are reasonable, i.e., are similar to the observed measurements, and lends plausibility to the empirical model.

Fig. 2.

Observed lesion size (black solid circles) versus the imputed lesion size (red crosses) for a sample of patients, across 5 imputation sets. In the analysis, any observed lesion measurements were retained and not replaced by imputed values; any imputed values appearing below (for which an observed measurement was available) are solely for illustration purposes to facilitate comparison between imputed and observed values. The imputed values and the observed measurements are similar. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The change in objective status based on the target lesions at 12-weeks, using the observed datasets vs. one of the imputed datasets, is shown in Table 2. Of the 8 patients who were originally CR based on observed data, 2 (25%) were reclassified into another objective status based on the imputed data; of the 191 PR's, 30 (16%) were reclassified; of the 261 SD's, 87 (33%) were reclassified; of the 51 PD's, 0 (0%) were reclassified; and of the 327 NA's, 327 (100%) were classified. We note that these changes (e.g. from CR to PR) are expected since, by imputing missing lesion measurements at follow-up assessments, we are filling in the missing lesions measurement and hence increasing the tumor burden (i.e. sum of lesion measurements). While this may seem to introduce bias into the data, ignoring the missing data and conducting a complete-case analysis also introduces bias in the opposite (more optimistic, better objective status) direction. See Appendix A4 for hypothetical scenarios of change in objective status after imputation.

Table 2.

Change in objective status (CR, PR, SD, PD) at 12 weeks, based on one imputed (y-axis) dataset vs. observed (x-axis) dataset. Across all 3 studies, of the 8 patients that were originally CR based on observed data, 2 (25%) were reclassified into another objective status based on the imputed data; of the 191 PR's, 30 (16%) were reclassified; of the 261 SD's, 87 (33%) were reclassified; of the 51 PD's, 0 (0%) were reclassified; and of the 327 patients with missing objective status (“NA”)a, 327 (100%) were classified.

| Imputed Dataset Target Lesion Objective Status | Observed Dataset Target Lesion Objective Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PR | SD | PD | N/A | |

| PD | 2 | 24 | 87 | 51 | 180 |

| SD | 6 | 174 | 27 | ||

| PR | 161 | 120 | |||

| CR | 6 | ||||

| Total | 8 | 191 | 261 | 51 | 327 |

The patients with missing objective status (“NA”) based on observed data had baseline and at least one assessment after 12 weeks, but did not have an assessment at 12-weeks (±2 weeks) required to calculate objective status.

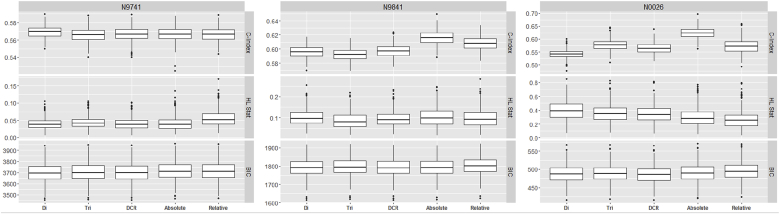

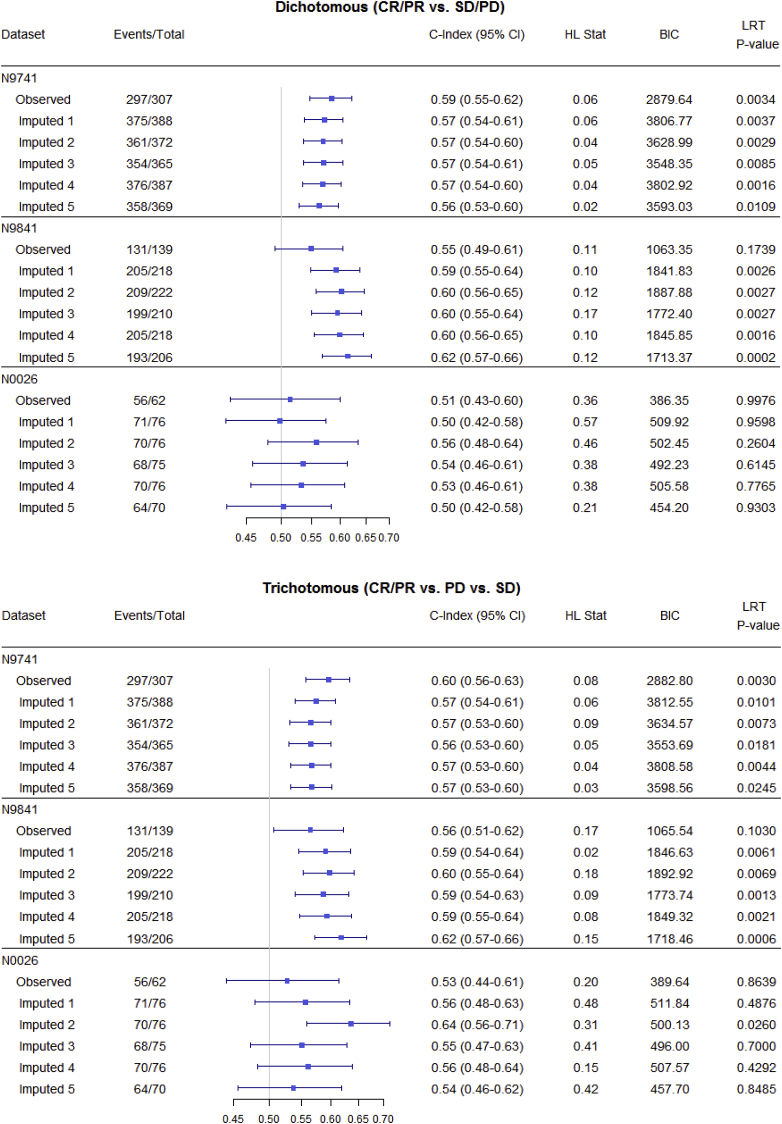

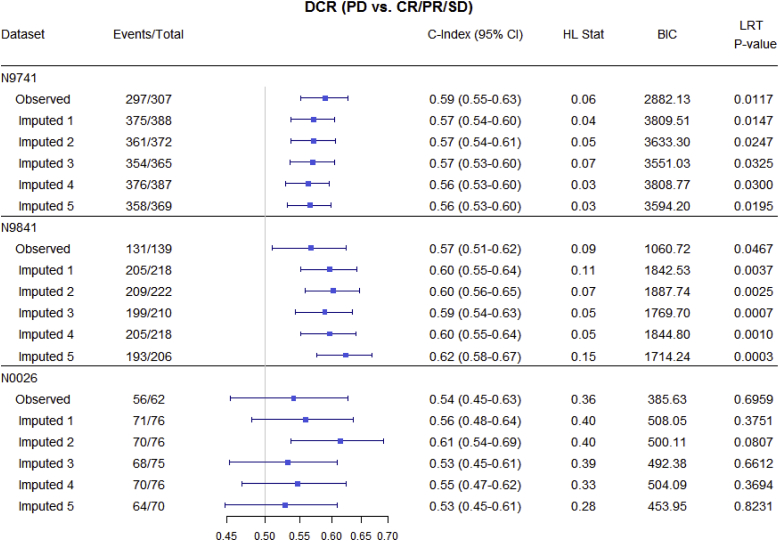

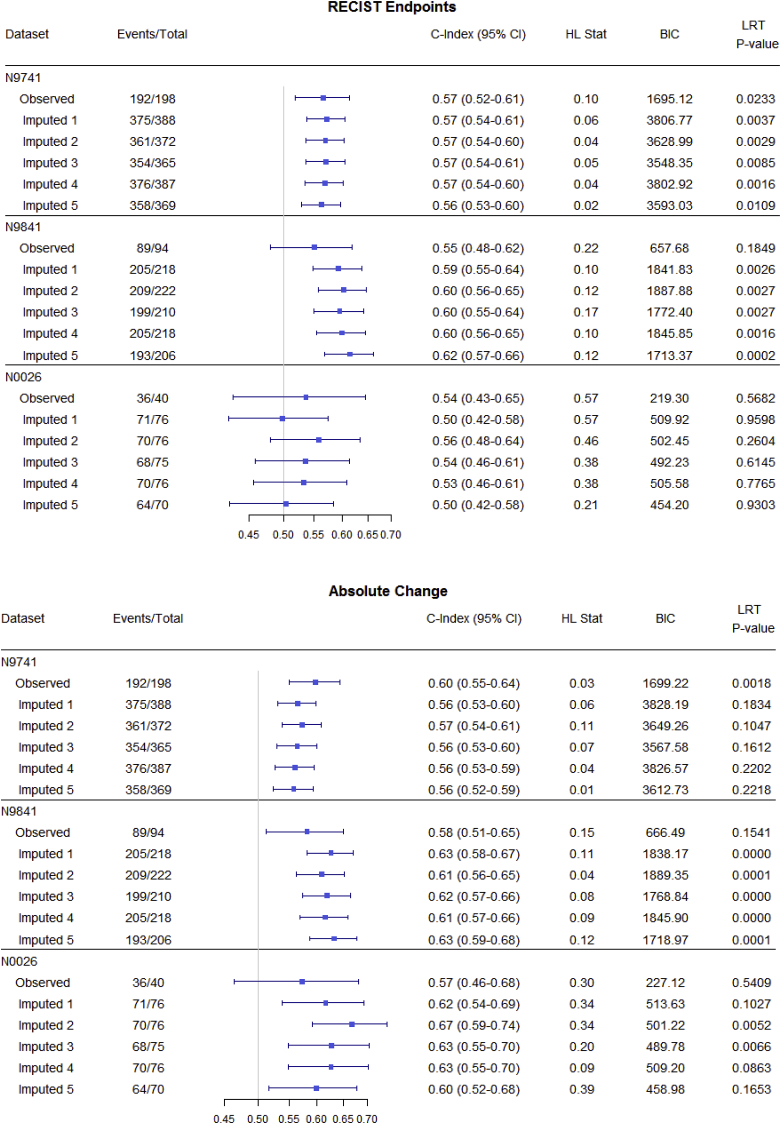

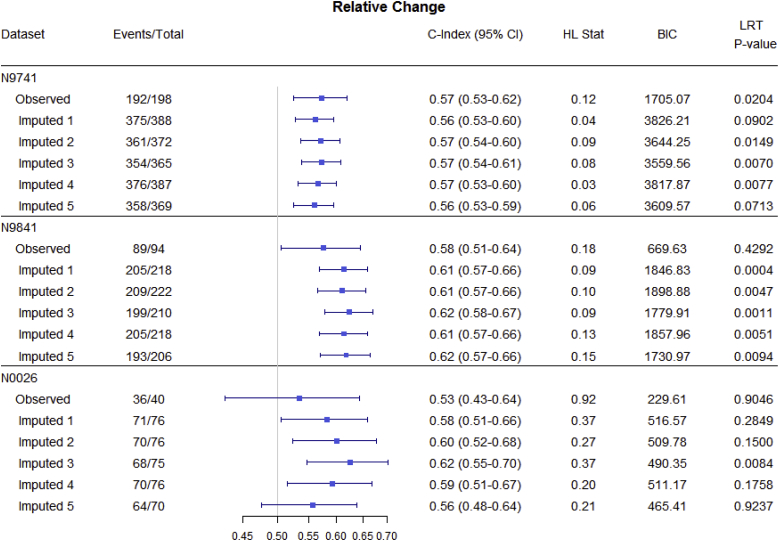

Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Table 3 summarize OS predictive ability metrics across studies and datasets. Specifically, Fig. 3 shows the distribution of metrics (c-index, Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, and BIC), while Table 3 displays p-values of significance tests (F-test) for combining likelihood ratio test (LRT) results [22] across 500 imputed datasets, by study and by endpoint. Fig. 4 summarizes the metrics for categorical endpoints from Mandrekar et al. (2014) [[9]; see also Appendix A1] and Fig. 5 summarizes the metrics for continuous endpoints from An et al. (2015) [[10]; see also Appendix A1] with RECIST dichotomous response for comparison, for the three studies and different datasets (observed and imputed). There is more variability in the c-indices for N0026 compared to the other studies, as expected since N0026 has a smaller sample size. In general, however, for a given endpoint and study, the pointwise c-indices are similar across observed and imputed datasets.

Fig. 3.

Distributions of statistical measures of overall survival (OS) predictive ability across 500 imputed datasets, by study and by endpoint. Statistical measures include the c-index, Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, and the BIC. Endpoints include dichotomous (CR/PR vs. SD/PD), trichotomous (CR/PR vs. PD vs. SD), disease control rate (PD vs. CR/PR/SD), absolute change, and relative change.

Fig. 4.

Statistical measures of overall survival (OS) predictive ability for categorical endpoints (observed vs. imputed; only 5 imputed datasets are shown, for illustrative purposes), by study. Endpoints include dichotomous (CR/PR vs. SD/PD), trichotomous (CR/PR vs. PD vs. SD), and disease control rate (PD vs. CR/PR/SD). The important observation is that, for a given endpoint and study, discriminatory ability (measured by the c-index) is similar across imputed datasets.

Although the imputed datasets initially have the same sample size (“Total”), after responses are calculated based on imputed measurements, some patients are found to progress before 12 weeks and so are excluded from the 12-week landmark analysis.

Fig. 5.

Statistical measures of overall survival (OS) predictive ability for continuous endpoints using different datasets (observed vs. imputed; only 5 imputed datasets are shown, for illustrative purposes), by study. Endpoints include RECIST response (CR/PR vs. SD/PD), absolute change (change in tumor size from 0 to 6 and 6–12 weeks), and relative change (relative change in tumor size from 0 to 6 and 6–12 weeks) endpoints. The important observation is that, for a given endpoint and study, discriminatory ability (measured by the c-index) is similar across imputed datasets.

Although the imputed datasets initially have the same sample size (“Total”), after responses are calculated based on imputed measurements, some patients are found to progress before 12 weeks and so are excluded from the 12-week landmark analysis.

Table 3.

P-valuesa from F-tests for combining likelihood ratio test (LRT) results across 500 imputations, by study and by endpoint. Endpoints include dichotomous (CR/PR vs. SD/PD), trichotomous (CR/PR vs. PD vs. SD), disease control rate (PD vs. CR/PR/SD), absolute change, and relative change.

| F-test (p-value) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichotomous | Trichotomous | DCR | Absolute Change | Relative Change | |

| N9741 | 0.0105 | 0.0069 | 0.0246 | 0.0103 | 0.0069 |

| N9841 | 0.0048 | 0.0034 | 0.0045 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 |

| N0026 | 0.7256 | 0.3045 | 0.4805 | 0.0225 | 0.1885 |

The F-test for combining LRT results across 500 imputations compares a full model with the endpoint and average baseline tumor size as predictors vs. a null model with no predictors. Statistically significant results suggest the endpoint, adjusted for average baseline tumor size, are important for the model.

It is interesting to note that although there are changes in objective status between observed and imputed datasets, thus potentially affecting individual trial results, there is minimal impact on the OS predictive ability (reflected in similar pointwise c-indices) of the alternative endpoints [[9,10]; see also Appendix A1], which was our primary question of interest.

5. Discussion

In this paper we follow Wang et al. [18] and use an empirical model to simulate (or “impute”) missing measurement data. As future work, we could adopt a formal multiple imputation approach, which requires careful consideration of the missing data mechanism [23]. Typically, the assumption of mechanism is based on knowledge of the data and its collection process and is generally non-testable without direct modeling of the missing data mechanism [24]. In clinical trials data, as we outlined above, there are different forms of missingness (e.g. missing a lesion measurement versus missing an entire patient assessment of target lesions), each arising from different potential reasons. For instance, a missing lesion measurement due to data entry issues is likely missing completely at random (MCAR). On the other hand, certain locations of metastases are conceivably more likely prone to result in missing lesion measurements due to technical reasons. For example, it is easy to identify and measure liver and lung metastases, but it is much more difficult to reliably identiy and measure peritoneal disease. Thus, in this case a missing lesion measurement might depend on the lesion location and be missing at random (MAR). Similarly, a missing assessment due to underlying patient health conditions could be missing not at random (MNAR), with the direction of bias going in either direction (patient feeling too sick vs. feeling well). However, we note that in our analysis, we subset to those patients who have subsequent scans after a missed assessment, which implies that the patients did not progress or recur at the missed assessment. As such, we believe it is less likely that a missing assessment is related to disease status, and thus less likely to be MNAR. Unfortunately, the specific reasons are not routinely recorded as part of clinical trials data collection. Therefore, as future work, it might be helpful to first investigate deeper into the actual reasons for missingness (if available) and then conduct a sensitivity analysis comparing different multiple imputation models based on the proposed mechanisms of missingness. Alternatively, a simulation study exploring the impact of different patterns of missing data mechanisms, and ways to address these, on both predictive ability of alternative endpoints and trial outcomes might be of future interest.

Our expectation is that the identification of optimal endpoints may be robust to the imputation model choice. It is reasonable to expect the actual measures of predictive ability to change based on model, but that these changes would be similar across endpoints. That is, there might only be a shift in distribution of measure (e.g. c-index) across endpoints when comparing one model versus another and as such the ranking of endpoints in terms of predictive ability, and hence choice of optimal endpoint, are preserved.

6. Conclusion: call to the community (clinical and statistical) for more complete data collection

Several practical insights emerged from our work in identifying alternative TM-based endpoints using real-world clinical trials data. First, this work acknowledges the widespread problem of missing TM data in cancer clinical trials data. Second, we documented several reasons for missingness using a case study. Knowing these reasons can better equip us to address the problems of missing TM data in a proactive manner. Further, missing TM data may be minimized if clinical trials are better aligned with clinical practice, specifically: (a) the TM schedule reflects clinical practice (e.g. avoid requiring scans every 8 weeks if a patient is on a 3-week treatment regimen); (b) the methods for TM assessments should be in accordance with clinical practice (e.g. use of standard CT scans); and (c) TM assessments should not be too frequent, unless there is a specific trial-based scientific reason for it. Third, we recognize the two-fold goals in identifying alternative endpoints, namely to develop endpoints that are (1) both clinically relevant and simple, and (2) yet appropriately account for missing measurements. Our review of the literature suggests that most efforts to identify alternative phase II endpoints based on TM tend to prioritize the first goal, and seldom address the second. Although our case-study of sensitivity analysis suggests potentially minimal impact on the predictive ability of alternative TM-based categorical and continuous endpoints (our primary question of interest), it does suggest moderate to high impact of missing measurement data on objective status and thus the individual trial results that have response as the primary outcome. These findings require further validation. Therefore, striving for minimal missing information has to be the gold standard. This may be achieved, for example, by keeping protocols for recording measurements as simple as possible, thus facilitating better compliance for data recording practices. When measurements are missing or visits are missed, documenting reasons for missingness is also important for conducting appropriate analysis. Reaching the goal of clean and complete tumor measurement data should be a priority in the conduct of any cancer clinical trial.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant: CA167326.

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant U10CA180821 (Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology). It should also be noted that the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) is now part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100492.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kola I., Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Therasse P., Arbuck S.G., Eisenhauer E.A. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumors: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karrison T.G., Maitland M.L., Stadler W.M. Design of phase II cancer trials using a continuous endpoint of change in tumor size: application to a study of Sorafenib and Erlotinib in non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1455–1461. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaki T., Andre V., Su T.L. Designing exploratory cancer trials using change in tumour size as primary endpoint. Stat. Med. 2013;32(15):2544–2554. doi: 10.1002/sim.5716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claret L., Gupta M., Han K. Evaluation of tumour-size response metrics to predict overall survival in western and Chinese patients with first-line metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(17):2110–2114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki C., Blomqvist L., Sundin A. The initial change in tumor size predicts response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with combination chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(4):948–954. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piessevaux H., Buyse M., Schlichting M. Use of early tumor shrinkage to predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(30):3764–3775. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandrekar S.J., An M.W., Meyers J. Evaluation of alternate categorical tumor metrics and cutpoints for response categorization using the RECIST 1.1 data warehouse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(8):841–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An M.W., Dong X., Meyers J. Evaluating continuous tumor measurement-based metrics as phase II endpoints for predicting overall survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015;107(11) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim J.G., Chu H., Chen M.-H. Missing data in clinical studies: issues and methods. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(26):3297–3303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.7589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little R.J., D'Agostino R., Cohen M.L. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367(14):1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jemal A., Ward E.M., Johnson C.J. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2014, featuring survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An M.W., Mandrekar S.J., Branda M.E. Comparison of continuous versus categorical tumor measurement-based metrics to predict overall survival in cancer treatment trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:6592–6599. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg R.M., Sargent D.J., Morton R.F. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:23–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim G.P., Sargent D.J., Mahoney M.R. Phase III noninferiority trial comparing irinotecan with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma previously treated with fluorouracil: N9841. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:2848–2854. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma C.X., Nair S., Thomas S. Randomized phase II trial of three schedules of pemetrexed and gemcitabine as front-line therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:5929–5937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Sung C., Dartois C. Elucidation of relationship between tumor size and survival in non-small-cell NSCLC cancer patients can aid early decision making in clinical drug development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;86(2):167–174. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bürkner P.C. Brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017;80(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrell F.E., Jr., Califf R.M., Pryor D.B. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1982;247:2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Agostino R.B., Nam B.H. Evaluation of the performance of survival analysis models: discrimination and calibration measures. Handb. Stat. 2004;23 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall A., Altman D.G., Holder R.L. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: current practice and guides. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin D. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galimard J.-E., Chevret S., Curis E., Resche-Rigon M. Heckman imputation models for binary or continuous MNAR outcomes and MAR predictors. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0547-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.