Abstract

Background

Occupational violence is considered unlawful in professional environments worldwide. In the healthcare industry, including dentistry, the safety of workers is essential, and it is of the utmost importance to ensure patient and employee safety and provide quality care. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of violence and associated workplace policies among oral healthcare professionals. Additionally, it aimed to identify the factors associated with violence and their impact on oral healthcare workers.

Methods

A systematic review and analysis of the literature was conducted using PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and ProQuest. Original articles written in English and published between January 1992 and August 2019 were included in the analysis.

Results

A total of 980 articles were found, and eight were selected for analysis. The violence experienced by healthcare workers included both physical and non-physical forms, such as shouting, bullying, and threatening; it also included sexual harassment. The impact of violence on workers manifested as impaired quality of work, psychological problems, and, although rare, quitting the job. With regard to dental healthcare, awareness of occupational violence policies among dental professionals has not been previously reported in the literature.

Conclusions

The increasing incidence of occupational violence against oral healthcare workers indicates the need for the implementation of better protective measures to create a safe working environment for dental professionals. There is a current need for increasing awareness of workplace violence policies and for the detection and reporting of aggression and violence at dental facilities.

Keywords: Workplace violence, Oral healthcare workers, Meta-analysis, Verbal abuse, Sexual harassment, Aggression

Background

With the increasing incidence of violence worldwide, occupational violence has become a reality for all kinds of workers in various kinds of workplaces. Violence in the workplace is the third leading cause of death, and it leads serious safety and health issues that undermine the ability of health workers to focus on their jobs [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), violence in the healthcare industry negatively influences not only employees but also the workplace ambiance, colleagues, employers, families, and society as a whole, and it may result in injury, death, or psychological harm to the affected person. A WHO study reported that this type of violence could reduce health services for the general population, with a consequent increase in healthcare costs. Moreover, it leads to monetary losses ranging in the hundreds of dollars as well as to the loss of workdays [2].

Dentistry is more susceptible than other healthcare areas to occupational violence in hospitals and clinics because dental clinics are usually crowded with patients. The workers at dental healthcare facilities are exposed to threats to personal health during their duties in addition to the biohazard dangers they face due to the use of sharp instruments and chemical components [3, 4]. Oral healthcare occupational violence can be categorised into various forms, such as verbal abuse, property damage or theft, physical abuse, sexual harassment, and bullying. For example, a study performed in Nigeria showed that more than 70% of dental staff experienced verbal assault, although physical violence was reported to be rare [1]. Other studies have focused on sexual harassment due to the major increase in the number of women as healthcare professionals [5–7]. The most common perpetrators are patients and their relatives [1, 5]. Several factors contribute to violence against dental professionals, including long waiting times, the cancellation of appointments, the outcomes of patient treatment, alcohol intoxication, psychiatric patients, and expensive bills [1]. Additionally, the paucity of manpower to handle the increasing number of patients at dental healthcare centres and the uneven geographic distribution of these centres worsen the situation. Because of the aesthetic value associated with the face, any error on the part of a dentist can trigger rage and anger among patients, consequently leading to violent incidents [8].

A consensus definition of healthcare workplace violence, such as bullying, verbal abuse, sexual harassment, threat and physical abuse, was agreed upon and proposed in 2016 by Boyle and Wallis [9]. The absence of information on the prevalence and policies associated with workplace violence among dental professionals is related to poorly defined implementation and solutions. The current situation demands a comprehensive programme aimed at preventing workplace violence [10]. The current systematic review and meta-analysis are meant to evaluate the prevalence of violence experienced by oral healthcare professionals and the associated workplace policies at their facilities. Furthermore, the present study also aims to identify the factors associated with violence and their impact on oral healthcare workers.

Methods

We report this manuscript in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA statement) guideline [11]. All methods used in this review were conducted in strict accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [12].

Study design

The present systematic literature review search was performed using the systematic literature review tool Parsifal (https://parsif.al/). It is an easy-to-use web-based tool for designing protocols and extracting and managing data. Six databases were searched, specifically MEDLINE (PubMed), ABI/INFORM (ProQuest), Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and ScienceDirect (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search terms for each database

| Database | Search Term | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((dentist OR Oral healthcare workers OR dental professionals OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR threats OR harassment) NOT (child Abuse)) | 384 |

| Cochrane Library | ((dentist OR Oral healthcare workers OR dental professionals OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR threats OR harassment)) | 10 |

| Scopus | ((dentist OR Oral healthcare workers OR dental professionals OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR threats OR harassment)) | 72 |

| Science Direct | (((dentist OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR harassment)) AND (Cross-section OR Cross-sectional) NOT (Child Abuse))) | 447 |

| Web of Science | ((dentist OR Oral healthcare workers OR dental professionals OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR threats OR harassment) NOT (child Abuse)) | 44 |

| ProQuest | ((dentist OR Oral healthcare workers OR dental professionals OR dental assistant OR dental hygienists) AND (violence OR bullying OR threats OR harassment)) | 23 |

Search strategy

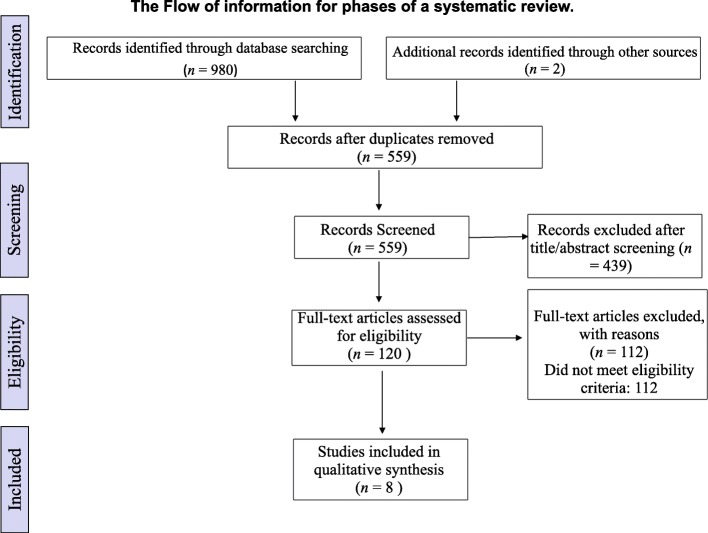

The keywords employed in the search strategy included “dentist” OR “oral healthcare workers” OR “dental professionals” OR “dental assistant” OR “dental hygienists” OR “general practitioners” AND “violence” OR “bullying” OR “threats” OR “harassment.” Only peer-reviewed articles that were written in English were considered. The final sample consisted of eight articles published between 1992 and 2019. After excluding duplicates, non-English articles, and irrelevant articles, the authors systematically reviewed the articles that met the predetermined criteria and studied only oral healthcare professionals’ knowledge related to detecting aggression, reporting violence, the prevalence of violence, and the awareness of occupational healthcare policies among dental professionals following the (PRISMA) guidelines [11], as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow of information through different phases of a systematic review

Study selection process and eligibility criteria

The authors screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved literature records. For titles and abstracts that were deemed relevant to the research question, the full-text articles were obtained and screened for eligibility according to the following criteria: 1) studies whose population was oral healthcare workers, interns, or students, 2) studies that assessed the prevalence of violence and associated workplace policies among oral healthcare professionals, 3) studies reporting any information about the causes of this violence, and 4) observational prospective or retrospective studies.

Articles were also excluded if they included a discussion of violence among general practitioners that included dentists as part of the team.

Data extraction

The data extracted included the year of publication, author’s name, country, study type, population, duration of study, sample size, response rate, demographic data (gender and age), type of violence, number of violent incidents per population, risk, effect, policy, action taken, percentage of each gender affected, and the persons responsible for the mistreatment.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of each included study. It includes eight assessment items for quality appraisal, including ‘selection’, ‘comparability’ and ‘outcome’. According to the NOS scoring standard, cross-sectional studies can be classified as low quality (scores of 0–4), moderate quality (scores of 5–6) and high quality (scores ≥7), Additional file 1.

Statistical meta-analysis

A random effects model meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the pooled success rate. Publication bias, fail-safe N, Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation, and the heterogeneity of the studies were determined using Michael Borenstein’s Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) programme, version 3 (Englewood, NJ, United States).

Results

In total, 980 articles were found based on the search strategy. Of these articles, eight were included after the removal of duplicates and non-English studies; these articles are summarised in Table 2. According to the NOS tool for quality assessment, four studies showed high quality (≥ 8 points), and four showed moderate quality (5 and 6 points), Table 3. The studies were cross-sectional surveys from Brazil, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, the United States of America, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom. Five of these studies were conducted at a dental school, one was conducted at a postgraduate dental hospital, and two were conducted at dental offices. Most studies assessed violence over a period of 2 to 12 months. The mean age ranged from 22 [5, 14] to over 60 years [15]. In most cases, male patients or coworkers were responsible for the mistreatment or violence. Sexual harassment was predominant among the types of violence that occurred in the field of dentistry, with a prevalence rate ranging from 6.8 to 54% in almost all the studies [1, 7]. Verbal abuse included shouting; extremely loud shouting was also frequently reported, and its prevalence ranged from 8.2 to 58.7% [13, 14]. Another type of violence reported was bullying, with a prevalence rate of 22 to 36.8% [1, 16]. Physical abuse was the least frequently reported type of violence, with a prevalence rate ranging from 4.6 to 22% [13, 14].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies focusing on violence among oral healthcare workers

| Author, country, year | Study duration (months) | Sample | Sample size | Response rate (%) | Percentage of violence (%) | Demographics: Age (years) and sex | Type of violence | Action and policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garvin and Sledge, USA, 1992 [6] | 2 | Dental hygienists | 650 | 72.6 | 26.3 | Age mean = 28.9, 100% females | Sexual harassment | Action: terminated employment, legal action, no action, reported incident. No policy |

| Pennington et al., USA, 2000 [7] | NA | Dental hygienists | 540 | 53 | 54 | Mean of age 40, 99% females | Sexual harassment | Action: File formal complaints. No policy |

| Garbin et al., Brazil, 2009 [5] | NA | Dental students | 254 | 82 | 15 | Age range:19–32 years (mean = 22), 65.9% females and 34.1% males | Sexual harassment (15%) | Action: Inform the mentor or do nothing. No policy |

| Steadman et al., United Kingdom, 2009 [13] | 12 | Postgraduate hospital dentists | 227 | 60 | 25 | NA | Bullying (25%), threat (8.2%), verbal abuse (8.2%), sexual harassment (7.5%), property damage (1.5%) | Action: Inform the mentor. No policy |

| Azodo et al., Nigeria, 2011 [1] | 12 |

Dental professionals |

175 | 78.9 | 31.9 | NA | Bullying and physical abuse (22%), loud shouting (50%), sexual harassment (6.8%), threat (22.7%) | Action: NA. No policy |

| Premadasa et al., Sri Lanka, 2011 [14] | 9 |

Junior dental students |

72 | 91 | 50 | Age range: 20–23, 67.7% females and 32.3% males | Loud shouting (50%), physical abuse (4.6%), sexual harassment (11.5%), threat, verbal abuse (58.7%) |

Action: Do nothing, inform friend or family, inform the mentor. No policy |

| McCombs et al., USA, 2018 [15] | 6 | Dental hygienists | 240 | 64 | 24 | Age range: 20 – > 60, 97% females and 3% males | Workplace bullying, opinions and views ignoring, and unmanageable workloads | Action: NA. No policy |

| Ullah et al., Pakistan, 2018 [16] | 6 | Dental interns | 135 | 92.59 | 36.8% | Mean age 24.0 ± 1.3, 69.6% females and 30.4% males | Workplace bullying, unmanageable workload, and being ignored or excluded | Action: Only 14.5% reported a complaint. No policy |

Table 3.

Quality assessment of the enrolled studies

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the sample | Sample size | Non-respondents | Ascertainment of the exposure (risk factor): | Comparability of subjects in different outcome groups on the basis of design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Statistical test | ||

| Garvin and Sledge [6] | * | * | * | * | * | 5/10 | ||

| Pennington et al. [7] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6/10 | |

| Garbin et al. [5] | * | * | * | ** | ** | * | 8/10 | |

| Steadman et al. [13] | * | * | * | ** | ** | * | 8/10 | |

| Azodo et al. [1] | * | * | * | * | * | 5/10 | ||

| Premadasa et al. [14] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | * | 9/10 |

| McCombs et al. [15] | * | * | * | ** | * | 6/10 | ||

| Ullah et al. [16] | * | * | * | ** | ** | * | 8/10 | |

Scale of studies (points): Very Good: 9–10, Good: 7–8, Satisfactory: 5–6, and Unsatisfactory: 0 to 4

A higher proportion of females than males was exposed to aggression and violence among oral healthcare workers, as reported by Garvin and Sledge [6], Pennington et al. [7] and Premadasa et al. [14]. Only one study reported a male predominance in exposure to violence [5]. The gender difference was statistically insignificant in the other studies [1, 6].

Several studies have discussed other factors associated with violence against oral healthcare workers. Long waiting times and a lack of staff training were the most frequent factors reported [1, 5]. Other contributing factors included alcohol intoxication and psychiatric illness, which accounted for 9.1 and 4.5% of the variables, respectively [1]. In all of the studies, the targets of violence reported negative effects of the abuse, such as a decline in ethical values, but few reported psychological stress or any impairment in their performance.

Most studies concluded that healthcare workers did not take any action to deal with the violence or abuse inflicted upon them. However, some abused workers discussed the issue with family members or close friends and reported it to their manager, mentor, or administrative office [5, 13, 14]. Ullah et al. [16] discussed the important reasons that those who experienced bullying did not complain: the majority of respondents (28.8%) thought that complaining was useless; 22% were afraid of the consequences, especially when the perpetrator was a senior faculty member; 20.8% of them felt they could deal with incidents on their own; and 16.9% considered the incident not sufficiently serious. This reflects the importance of educational and instructional courses on how to address such situations.

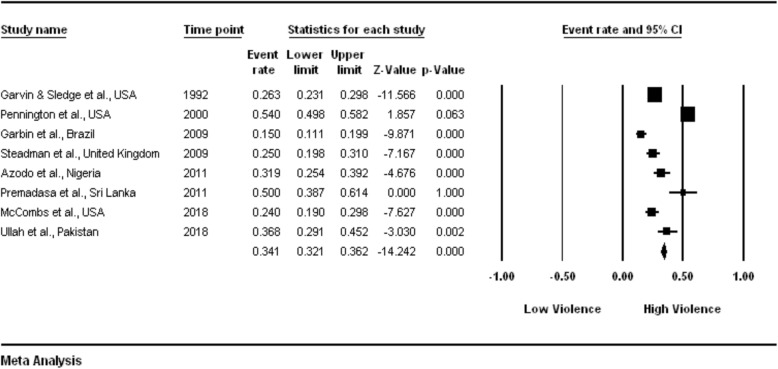

The fail-safe N was 453, and Kendall’s tau ß was 0.179, with a one-tailed p = 0.268. The outcomes of both of these tests indicated a lack of publication bias. The heterogeneity assessment reported a Q-value of 172.423, with df = 7, p < 0.001 and I2 = 95.94 (95% confidence interval: 0.321 to 0.362), suggesting that approximately 96% of the observed variance in the effects was real or heterogeneous.

The pooled estimate for the random-effect model was 0.320 (Fig. 2). An examination of the plot showed the following results:

The violent events were noticeably diverse from study to study;

The violent events ranged from a low of 15.0% to a high of 54.0%; and

The mean prevalence was 0.341 (32%), with a CI ranging from 0.321 to 0.362.

Fig. 2.

Detailed statistics for each study, with event rates calculated using random-effects model meta-analysis

Discussion

In practice and in the literature, the terms “aggression” and “violence” are often used interchangeably. Therefore, it is very important to define each term to solve this confusion. Human aggression was defined by Hills and Joyce [17] as “any action or behaviour directed by a perpetrator towards a target that is characterised by the perpetrator’s intention of causing harm or damage for the purpose of achieving a proximal or distal outcome, the target’s motivation to avoid the action or behaviour and the violation of norms that the action or behaviour represents.” On the other hand, workplace violence is a specific term that refers to incidents in which employees are harassed, endangered or attacked in work-related conditions, causing an explicit or implicit threat to their security, or health or well-being [18]. In the psychological and sociological literature, the phrase ‘workplace aggression’ is used most often, while ‘workplace violence’ is more frequently found in the literature on industrial and health professions [19].

Occupational violence, in any form, should not be acceptable, irrespective of the frequency of its occurrence. Personal safety should be a priority in any professional environment. Professionals have consistently underestimated the prevalence of violence among healthcare workers in general, especially in dental healthcare centres. The occurrence of occupational violence demonstrates the need for improved protection measures to create a safe working environment for dental professionals [1]. Several systematic reviews have been conducted in settings other than dental professional centres, such as emergency departments and nursing settings [20, 21]. A study among National Health System (NHS) staff showed that dentists were the group that least frequently reported work aggression or violence compared to emergency, acute care, and mental departments [3]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review conducted on violence against oral healthcare workers.

Violence in the workplace is associated with various negative consequences. First, it results in both physical and mental trauma for the victims. The victims find it difficult to concentrate on their jobs, as manifested by a decreased interest in work, increased leaves of absence, and decreased job satisfaction. Worker compensation losses, decreased productivity, and the deterioration of ethical values are additional outcomes. Most of the time, the incidence of violence goes unnoticed or underreported [2]. In the studies reviewed in this paper, the victims reported experiencing psychological stress and impairment to their jobs.

The perpetrators of physical violence are usually people from outside the office, for example, patients and their relatives, whereas verbal abuse and bullying are usually carried out by senior colleagues [22]. This finding is inconsistent with a study by Premadasa et al. [14], which found that senior students and instructors are responsible for most sexual harassment incidents. We found that women working in dentistry reported a high prevalence of occupational violence compared to men, a finding similar to several previous studies in other healthcare areas [23, 24]. The availability of limited information in some studies prevented us from calculating the number of males and females who had undergone violent experiences. The mean age of the participants in the studies demonstrated that most of the people exposed to violence were young, a finding that was consistent with many studies [23, 25]. The review articles discussed various types of occupational violence, among which sexual harassment was the most frequently mentioned in all studies, although it was not the most frequently occurring type of incident. Verbal abuse was the most frequently occurring type of violent incident reported in two studies [1, 14]. These findings are comparable to other studies conducted in India and the United Kingdom [26, 27].

Dental professionals usually take no action against abuse due to perpetrator-target relationships [28]. There is clearly a lack of institutional justice and standards or guidelines with regard to dealing with the issue. No intervention studies in the dentistry field have investigated the role of awareness and education in improving the detection and reporting of abuse [29]. A new strategy should be designed to mitigate violence and abuse against dentists and their staff that involves a combination of individual, organisational, social, and political support.

No incidence of violence should remain unnoticed or underreported. However, most incidences of violence are overlooked, which results in worker dissatisfaction in the long run. Addressing the causes leading to violence at dental care centres and improving the quality of service provided may help reduce the likelihood of violent incidents. Improving treatment and reducing waiting times could strengthen doctor-patient communication. Effective interventions in terms of the enhancement of security at dental healthcare centres and sufficient social support should be implemented. Several studies highlighted the importance of social support in reducing anger, frustration and conflict in the work environment in addition to allowing employees to voice their experiences without any concerns about repercussions [30, 31].

At the organisational level, healthcare managers and policy makers should shoulder the responsibility for planning and implementing appropriate guidelines and interventions for reporting and preventing incidences of violence [32]. Organisations should also support the development and analysis of interventions to enhance professional detection and reporting of abuse, including staff documentation, documentation by the attacked employee, contact by legal representatives, contact by outside medical facilities, security patrols, camera installation, the use of bright lights at night, staff support, and truthful media reporting [33]. Additionally, the existence of a violence prevention programme in the workplace may prove beneficial in combating and eliminating any violence-related risk. Individuals in higher positions within the hierarchy should act and respond promptly to any incident of physical or verbal violence, thereby effectively assuring workers’ safety and protection.

The low priority society places on the rights and safety of healthcare providers is another contributing factor. Therefore, dental organisations and societies, such as the American Dental Association (ADA) [34], should act to protect the profession and advocate for policies that prevent violence against dentists and dental staff. Following the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), oral healthcare workers are encouraged to attend training that raises their awareness about the risks of aggression and violence; however, these steps are still insufficient to prevent the issue [10]. Similarly, the government should enact strict laws and regulations that require the investigation of any incidence of violence in dental healthcare centres with the utmost transparency. Abiding by such legislation should be mandatory for all professional centres. Additional steps to curb violence in the workplace may involve conducting a regular questionnaire-based survey to assess awareness among health professionals while keeping their identity secret. Several policies need to be adopted to reduce violent incidents and protect dental professionals. In cases of abuse and violence by patients, all healthcare services should be denied. For example, in England, after violence against any employee by a patient is reported, the patient is removed from the NHS and cannot schedule an appointment with any dentist registered with the NHS [35]. Anti-violence and anti-harassment groups for dental professionals should act in pursuit of a healthy and safe working environment.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis quantified the prevalence of violence towards dental professionals. The findings were limited because of the paucity of articles related to this issue that discussed the incidence of violence against oral healthcare workers and the actions taken to prevent it. The statistical analysis showed that there was no publication bias among the assessed articles. However, it should be noted that these results do not necessarily reflect the significance of the results due to the limited number of studies and their statistical power.

Conclusions

Violence of various forms is a common occurrence in the workplace. The present systematic review demonstrated a moderate prevalence of violence at dental healthcare centres, especially against females. The most commonly observed violence type was sexual harassment, followed by verbal and physical abuse. Healthcare workers at dental centres should inculcate a zero-tolerance approach and should not ignore any warning signs. The lack of implementation of strict guidelines at these centres augments the situation. There is a current need to design and adopt improved policies through collaborations between dental organisations and societies and law-making bodies. Further high-quality studies are needed to investigate the association between violence against dental healthcare workers and the related factors.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies adapted from the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Kalvin Balucanag and his team for their support with the statistical analysis.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ADA

American Dental Association

- CMA

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis

- NHS

National Health Service

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- OSHA

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Authors’ contributions

NB conducted the searches and extracted the articles. NB and JA reviewed the articles and extracted the data. NB analysed and interpreted the data. JA and NB contributed to writing the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received any funds from internal or external sources.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nada O. Binmadi, Email: nmadi@kau.edu.sa

Jazia A. Alblowi, Email: jaalblowi@kau.edu.sa

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12903-019-0974-3.

References

- 1.Azodo CC, Ezeja EB, Ehikhamenor EE. Occupational violence against dental professionals in southern Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:486–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.di Martino V. Relationship of work stress and workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ipsos MORI . Violence against frontline NHS staff: research study conducted for COI on behalf of the NSH security management service. 2010. p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kay EJ, Lowe JC. A survey of stress levels, self-perceived health and health-related behaviours of UK dental practitioners in 2005. Br Dent J. 2008;204:E19. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbin CAS, Zina LG, Garbin AJI, Moimaz SAS. Sexual harassment in dentistry: prevalence in dental school. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18:447–452. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000500004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garvin C, Sledge SH. Sexual harassment within dental offices in Washington State. J Dent Hyg. 1992;66:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennington A, Darby M, Bauman D, Plichta S, Schnuth ML. Sexual harassment in dentistry: experiences of Virginia dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:288–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamalik N, Perea Pérez B. Patient safety and dentistry: what do we need to know? Fundamentals of patient safety, the safety culture and implementation of patient safety measures in dental practice. Int Dent J. 2012;62:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle MJ, Wallis J. Working towards a definition for workplace violence actions in the health sector. Saf Health. 2016;2:4. doi: 10.1186/s40886-016-0015-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers (OSHA Publication 3148–06R). Washington: Department of Labor; 2016.

- 11.Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:91–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandler J, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ, Davenport C, Clarke MJ. Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Handb Syst Rev Interv. 2017;520:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steadman L, Quine L, Jack K, Felix DH, Waumsley J. Experience of workplace bullying behaviours in postgraduate hospital dentists: questionnaire survey. Br Dent J. 2009;207:379–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Premadasa IG, Wanigasooriya NC, Thalib L, Ellepola ANB. Harassment of newly admitted undergraduates by senior students in a Faculty of Dentistry in Sri Lanka. Med Teach. 2011;33:e556–e563. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.600358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCombs GB, Tolle SL, Newcomb TL, Bruhn AM, Hunt AW, Stafford LK. Workplace bullying: a survey of Virginia dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullah R, Siddiqui F, Zafar MS, Iqbal K. Bullying experiences of dental interns working at four dental institutions of a developing country: a cross-sectional study. Work. 2018;61:91–100. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hills DJ. Defining and classifying aggression and violence in health care work. Collegian. 2018;25:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labour I. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector for addressing workplace violence in the health sector. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hills D, Joyce C. A review of research on the prevalence, antecedents, consequences and prevention of workplace aggression in clinical medical practice. Aggress Violent Behav. 2013;18:554–569. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edward K, Stephenson J, Ousey K, Lui S, Warelow P, Giandinoto J-A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:289–299. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikathil S, Olaussen A, Gocentas RA, Symons E, Mitra B. Review article: workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta analysis. Emerg Med Australas. 2017;29:265–275. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schat ACH, Frone MR, Kelloway EK. Prevalence of workplace aggression in the U.S. Workforce: findings from a national study. In: Kelloway EK, Barling J, Hurrell J, editors. Handbook work violence. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2006. pp. 47–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar M. A study of workplace violence experienced by doctors and associated risk factors in a tertiary care hospital of South Delhi, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22306.8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Canbaz S, Dündar C, Dabak S, Sünter AT, Pekşen Y, Cetinoğlu EC. Violence towards workers in hospital emergency services and in emergency medical care units in Samsun: an epidemiological study. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2008;14:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsh J, Patel S, Gelaye B, Goshu M, Worku A, Williams MA, Berhane Y. Prevalence of workplace abuse and sexual harassment among female faculty and staff. J Occup Health. 2009;51:314–322. doi: 10.1539/joh.L8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ness GJ. Aggression and violent behaviour in general practice: population based survey in the north of England. BMJ. 2000;320:1447–1448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devi N, Singh A, Thongam K, Padu J, Abhilesh R, Ori J. Prevalence and attitude of workplace violence among the post graduate students in a tertiary hospital in Manipur. J Med Soc. 2014;28:25. doi: 10.4103/0972-4958.135222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, Ternan E, Endacott R. Workplace abuse narratives from dentistry, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy students: a multi-school qualitative study. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015;19:95–106. doi: 10.1111/eje.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheridan RA, Hammaker DJ, de Peralta TL, Fitzgerald M. Dental students’ perceived value of peer-mentoring clinical leadership experiences. J Dent Educ. 2016;80:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuckey MR, Dollard MF, Hosking PJ, Winefield AH. Workplace bullying: the role of psychosocial work environment factors. Int J Stress Manag. 2009;16:215–232. doi: 10.1037/a0016841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Emmerik IH, Euwema MC, Bakker AB. Threats of workplace violence and the buffering effect of social support. Gr Organ Manag. 2007;32:152–175. doi: 10.1177/1059601106286784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lippel K, (CVO) Addressing occupational violence: an overview of conceptual and policy considerations viewed through a gender lens. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social services workers. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Dental Association . Occupational safety and health administration (OSHA). Oral health topics. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson C, Noblett J, Parke H, Clement S, Caffrey A, Gale-Grant O, Schulze B, Druss B, Thornicroft G. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:467–482. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies adapted from the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.