Abstract

Background

Polarity is necessary for epithelial cells to perform distinct functions at their apical and basal surfaces. Oral epithelial cell-derived ameloblasts at secretory stage (SABs) synthesize large amounts of enamel matrix proteins (EMPs), largely amelogenins. EMPs are unidirectionally secreted into the enamel space through their apical cytoplasmic protrusions, or Tomes’ processes (TPs), to guide the enamel formation. Little is known about the transcriptional regulation underlying the establishment of cell polarity and unidirectional secretion of SABs.

Results

The higher-order chromatin architecture of eukaryotic genome plays important roles in cell- and stage-specific transcriptional programming. A genome organizer, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 1 (SATB1), was discovered to be significantly upregulated in ameloblasts compared to oral epithelial cells using a whole-transcript microarray analysis. The Satb1−/− mice possessed deformed ameloblasts and a thin layer of hypomineralized and non-prismatic enamel. Remarkably, Satb1−/− ameloblasts at the secretory stage lost many morphological characteristics found at the apical surface of wild-type (wt) SABs, including the loss of Tomes’ processes, defective inter-ameloblastic adhesion, and filamentous actin architecture. As expected, the secretory function of Satb1−/− SABs was compromised as amelogenins were largely retained in cells. We found the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8), a known regulator for actin filament assembly and small intestinal epithelial cytoplasmic protrusion formation, to be SATB1 dependent. In contrast to wt SABs, EPS8 could not be detected at the apical surface of Satb1−/− SABs. Eps8 expression was greatly reduced in small intestinal epithelial cells in Satb1−/− mice as well, displaying defective intestinal microvilli.

Conclusions

Our data show that SATB1 is essential for establishing secretory ameloblast cell polarity and for EMP secretion. In line with the deformed apical architecture, amelogenin transport to the apical secretory front and secretion into enamel space were impeded in Satb1−/− SABs resulting in a massive cytoplasmic accumulation of amelogenins and a thin layer of hypomineralized enamel. Our studies strongly suggest that SATB1-dependent Eps8 expression plays a critical role in cytoplasmic protrusion formation in both SABs and in small intestines. This study demonstrates the role of SATB1 in the regulation of amelogenesis and the potential application of SATB1 in ameloblast/enamel regeneration.

Keywords: Ameloblast, Enamel, Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein-1 (SATB1), Amelogenin, Claudin 1, Tight junction, Filamentous actin assembly, EPS8, Epithelial polarity, Membrane trafficking

Background

The establishment of polarity is pivotal for many fundamental epithelial cellular functions. Epithelial polarity is characterized by cells with distinct apical and basolateral surface structural orientations and molecular localization patterns that allow cells to fulfill their specialized functions, for instance, small intestine epithelial cells uptake nutrients at their apical surface and attach to the basement membrane at the basal surface [1, 2].

Ameloblasts are specialized epithelial cells responsible for the formation of the enamel, the hardest tissue in the human body, acting to protect the teeth from wear, caries progression, and fracture. Ameloblast differentiation goes through a series of sequential morphological changes, which begins with the proliferating and thickening of the cuboidal oral epithelial cells lining the first branchial arches of the jaws at the presumptive tooth sites. In response to the signaling from the dental mesenchyme, cuboidal dental epithelial precursor cells differentiate into the epithelial lineage of the enamel organ, including a layer of inner enamel epithelial cells (IEEs), stratum intermedium, stellate reticulum, and a layer of outer enamel epithelial cells. IEEs progress to a single-cell layer of tightly packed and columnar presecretory ameloblasts (PABs) when the distal outer layer of the dental papilla differentiates into odontoblasts and secretes dentin matrix, in which the primary organic component is type I collagen [3]. The signaling cues from dental mesenchymal cells and dentin matrix facilitate further differentiation of PABs to morphologically and functionally distinct secretory ameloblasts (SABs).

SABs are a layer of tall columnar epithelial cells which have an average ratio of length to diameter of about 10. In these elongated cells, the nuclei shift toward the stratum intermedium at the basal surface, allowing the rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi complex, and secretory vesicles to occupy a large portion of the supranuclear compartment. Utilizing these organelles, SABs synthesize and package enamel matrix proteins (EMPs), composed of 90% amelogenins, into the vesicles and subsequently transport them to the apical surface of SABs. These vesicles fuse with the Tomes’ processes, which are six-sided pyramid-like cytoplasmic protrusion at the apical surface of SABs, and then EMPs are deposited into the extracellular enamel space [4, 5]. Cytoskeleton fibers play important roles in coordinating the directional movement of ameloblasts and their secretory vesicles [6]. Filamentous actin bundles shape Tomes’ processes, to form a secretory front to direct the polarized trafficking of secretory vesicles and orientation of enamel crystals, also referred to as enamel rods [7–11]. Enamel crystal rods are arranged in parallel arrays and form an intricate 3D pattern which creates flexibility and strength of the mineralized enamel matrix [12].

As the full thickness of the enamel matrix is deposited, secretory ameloblasts differentiate into maturation ameloblasts. These cells adopt a low columnar morphology and are primarily responsible for ion transport and reabsorption of water and peptides hydrolyzed from the enamel matrix proteins [13–15] to orchestrate the full mineralized enamel matrix that consists of 96% minerals. When enamel biomineralization is complete, ameloblasts subsequently either commit to apoptosis or become the junctional epithelial cells prior to tooth eruption [16, 17]. Hence, ameloblasts do not exist in adult human teeth.

To move toward our ultimate goal of regenerating an entire human tooth organ, it is essential to develop strategies to establish a reliable source of functional ameloblasts. Each developmental stage of ameloblasts has unique features in gene expression profile, morphology, cellular processes, and functions. Thus, the complexities of ameloblast differentiation pose a big hurdle to advance our goals for tooth regeneration. To better understand the stage-specific ameloblasts, first, we utilized the whole-transcript microarray analyses to identify the significantly differentially expressed transcriptional regulators in presecretory ameloblasts (PABs) and secretory ameloblasts (SABs), as compared to autologous oral epithelial cells (OEs) and human embryonic stem cell-derived epithelial cells (ES-ECs). Our studies showed that special AT-rich sequence-binding protein-1 (SATB1) [18] was upregulated in ameloblasts in a tissue- and stage-specific manner during tooth development. We focused our study on SATB1 because it has a global gene regulatory function as a genome organizer by regulating 3D chromatin architecture [19–26]. With the use of a Satb1−/− mouse model [27], we demonstrate that indeed SATB1 is a critical regulator for ameloblast polarization, apical actin filament assembly, Tomes’ process formation, and enamel matrix protein secretion.

Results

Ameloblasts have cell type- and stage-specific gene expression profiles

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the normalized microarray data showed that the triplicate samples of each cell type (designated as ES-EC, OE, PAB, and SAB) were tightly distributed in a biplot, indicating the reproducibility of these assays. The reduced principal components of each cell type clustered together, and each had their own unique positions in the biplot (see Additional file 1: Figure S1), indicating that ameloblasts, as a type of highly specialized epithelial cells, did exhibit a distinctive gene expression pattern as compared to non-dental epithelial cells ES-EC and OE.

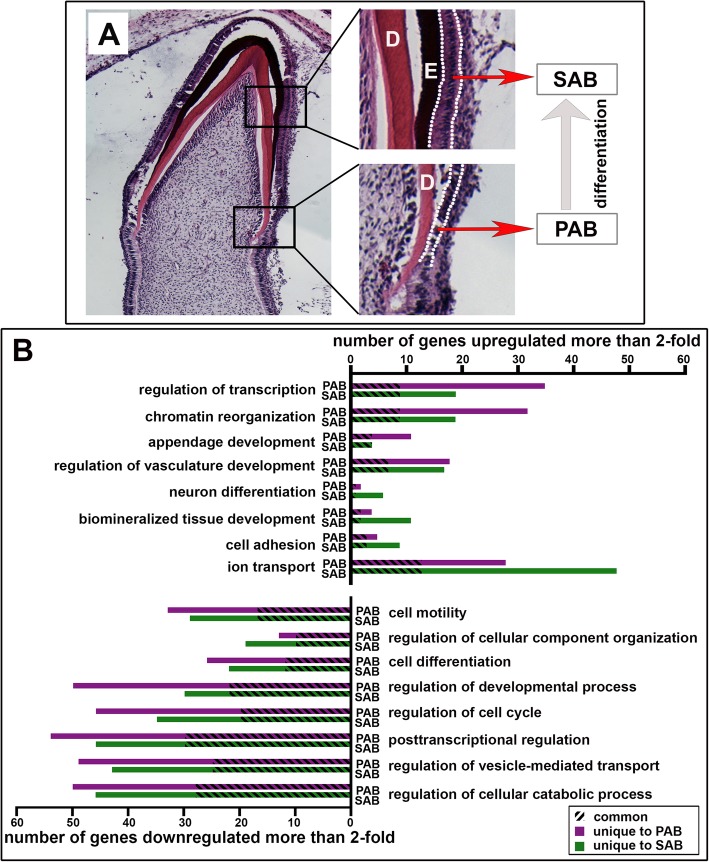

Differential gene expression analyses showed that there were 908 genes in PAB and 1203 genes in SAB that were either down- or upregulated more than 2.0-fold as compared to the average expression level of the same gene expressed by ES-EC and OE (p < 0.05). The most significantly upregulated genes in SAB or PAB were genes related to biomineralized tissue development, cell adhesion, ion transport, transcriptional regulation, epithelial appendage development, and neuron differentiation. It is not surprising that ameloblasts, epidermal cells, and neuronal cells share some degree of similarity, since they are all derived from the ectoderm. The most significantly downregulated genes were involved in cell motility, cellular component organization, cell cycle and regulation of cellular catabolic process, etc., indicating the terminal differentiation state of ameloblasts. The numbers of significantly up- or downregulated genes in several key gene ontology terms are illustrated in Fig. 1b. PAB and SAB shared many similar molecular phenotypes, as evidenced by the fact that many genes were commonly regulated in both cell types.

Fig. 1.

The unique expression patterns of presecretory ameloblasts and secretory ameloblasts are identified through a comparison whole-transcript expression microarray analysis. a The anatomic structure of presecretory ameloblasts (PAB) and secretory ameloblasts (SAB) that were collected from 18–19-week-old human developing incisors using laser capture microscope (LCM). Low columnar epithelial cells (between the dashed white lines in the lower right panel) next to the dentin matrix (D) were microdissected as PAB. Elongated and polarized epithelial cells (between the dashed white lines in the top right panel) adjacent to the organic enamel matrix (E) were microdissected as SAB. b The number of significantly upregulated (top) and downregulated (bottom) genes expressed by PABs and SABs as compared to non-dental epithelial cells in each of the top eight most significant GO terms, grouped by various Gene Ontology (GO) processes. A number of genes that were significantly altered in both PAB and SAB were labeled as common (identified by slashes), and the number of genes that were unique to either PAB or SAB was labeled in purple or in green

Next, we verified the expression levels of some ameloblast-associated marker genes by real-time PCR analysis (see Additional file 2: Figure S2), which confirmed the results from microarray analysis that enamel matrix proteins, including amelogenin, ameloblastin, and enamelin, were all significantly upregulated more than 50-fold in PAB and over 100-fold in SAB as compared to either ES-EC or OE. MMP-20, a specific enamel matrix proteinase [28], was upregulated 137-fold and 119-fold in SAB as compared to ES-EC and OE, respectively. MMP-20 increased about 6-fold in PAB as compared to either ES-EC or OE. Amelotin, an enamel matrix protein mostly produced by maturation ameloblasts [29], was also upregulated in SAB. Interestingly, dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) ,and dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP1), which are also linked to dentin and bone formation, were all significantly upregulated in SAB as compared to ES-EC, OE, and PAB.

Microarray analysis showed that claudin 1 (CLDN1), a major component of tight junction complexes that can join epithelial cells together as a continuous sheet [30–32], was the most upregulated cell adhesion-associated gene in SAB. Further, qPCR analyses of microdissected cells confirmed that this gene was upregulated 23- and 30-fold in the PAB and SAB, respectively, as compared to ES-EC (see Additional file 2: Figure S2). These data imply that as compared to the flat and cuboidal ES-EC and oral epithelial cells, the super elongated columnar ameloblasts may require more sturdy tight junctions to maintain the rigidity and paracellular permeability of ameloblast layer. Integrin alpha 2 (ITGA2), previously identified as a major integrin mediating the attachment of early-stage ameloblasts to the basement membrane and dentin matrix [33], was also upregulated in PAB as compared to ES-EC, OE, and SAB based on both microarray and qPCR analyses.

The two most significantly upregulated transcription regulators identified through the microarray analysis, and confirmed by qPCR, were SATB1 and c-MAF. It is worth mentioning that the microarray analysis also showed the significant upregulation of transcriptional regulator DLX3 in SABs. The functions of DLX3 in ameloblast differentiation and enamel formation have been previously identified [34–37].

SATB1 distributes in the ameloblasts in a stage-specific manner

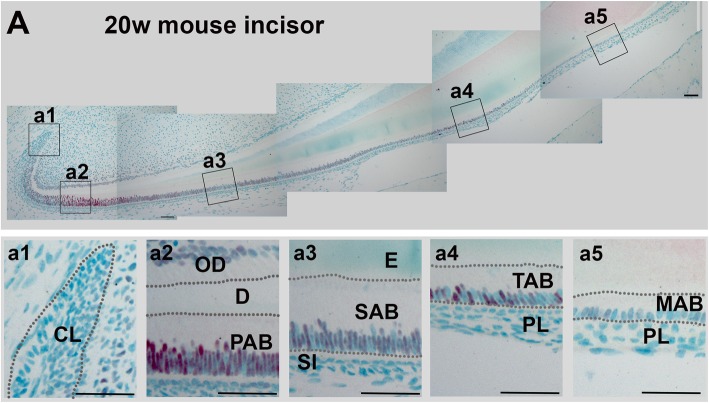

We chose to study the potential role of SATB1 in ameloblast/enamel formation because of its capacity to establish cell-specific transcription programs during the specific cell lineage development, including epidermal cells [38], T cells [21, 24, 26, 27, 39–43], postnatal brain [44], and pituitary gland [45]. SATB1 is also known to reprogram transcription profiles in tumor cells to promote tumor progression and metastasis [22, 46, 47]. Immunohistochemical staining showed that, during tooth development, SATB1 was only immunolocalized in the nuclei of ameloblast lineage cells, with the highest signal in PABs; relatively reduced in SABs; and moderately increased again in transition-stage ameloblasts, with a subsequent reduction in maturation ameloblasts (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining shows that SATB1 is present in mouse incisors in a cell- and stage-specific manner. In a representative sagittal section of the incisor from 20-week-old wt C57BL/6J female mouse, SATB1 immunostaining signal (in red) was intense in PAB (a2), reduced in SAB (a3), then moderately increased in transition stage ameloblasts (TAB) (a4), and significantly reduced last in maturation ameloblasts (MAB) (a5). SATB1 could not be detected in cells of the cervical loop (CL; a1), stratum intermedium (SI; a3), and papillary layer (PL; a4 and a5). Scale bars in a1–a5, 50 μM

Satb1 ablation results in a thin and hypomineralized enamel

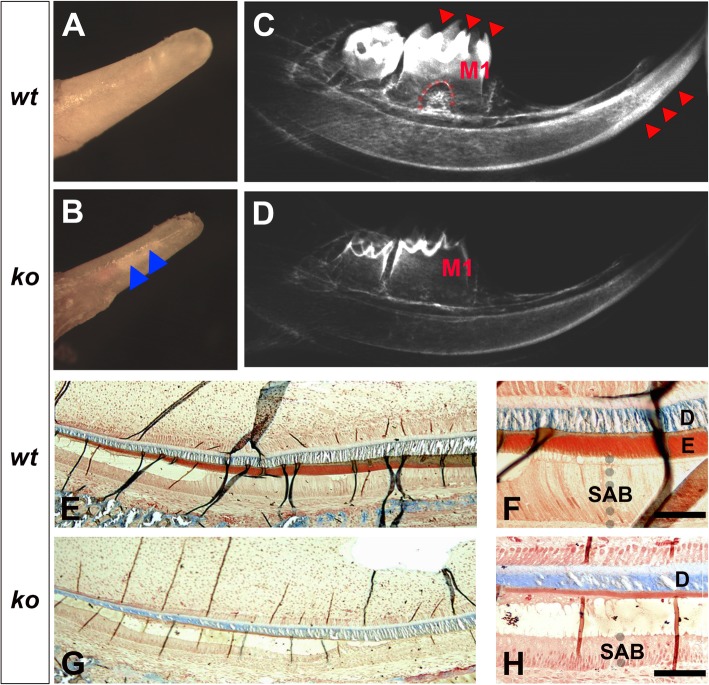

Satb1−/− pups generally die around 2.5 weeks after birth [27]. In normal mice, the molars typically have not yet erupted up to this age. Therefore, we focused on the incisor enamel of P13 days mice. In comparison with the age-matched control incisal tip (see Fig. 3a), the erupted portion of the P13 Satb1−/− incisor was smaller in diameter and more transparent in color (see Fig. 3b). In X-ray radiographic images, well-contrasted enamel layers were evident in the molars and incisors of P13 wt mice (indicated by red arrows in Fig. 3c), whereas the enamel layer in Satb1−/− mice was significantly thinner and less contrasted compared to the underlying dentin and surrounding alveolar bone (see Fig. 3d). Additionally, comparing the well-developed root furcation beneath the first molar (M1) of wild-type control (indicated by the red dashed line in Fig. 3c), no root furcation could be identified in the age-matched Satb1−/− mouse first molar (M1) (see Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

A thin and hypomineralized enamel layer is detected on the Satb1−/− mouse teeth. The gross morphology shows that the erupted portion of the P13 wt mouse mandibular incisor (a) is larger than the diameter of the erupted portion of the P13 Satb1−/− mouse mandibular incisor (b). The enamel layer of the Satb1−/− mouse incisor is more transparent, allowing the underneath dentin to be seen (indicated by blue arrows in b). c X-ray radiographic image of one wt hemimandible shows that well-contrasted mineralized enamel (indicated by red triangles) is easily distinguishable from the dentin on the molars and incisor. In the wt mouse first molar (M1), the root furcation is visible, as marked by the dashed red line. d As to the Satb1−/− mouse hemimandible, the X-ray radiographic image shows only the dentin to be seen; no furcation is detectable in M1. e Trichrome staining of the wt P13 incisor shows the mineralizing dentin layer stained in blue and enamel layer stained in red/brown. Wild-type secretory ameloblasts (SAB) (f), enamel (e), and dentin (d) are illustrated in the enlarged image. g In the P13 Satb1−/− mouse incisor, the dentin layer (in blue) had a thickness similar to that of controls, whereas the red/brown enamel layer was hardly visible. h The shortened SAB and significant thinned enamel layer underneath the dentin layer (d) in the Satb1−/− mouse incisor are further shown in the enlarged image. Scale bars in f and h, 50 μM

Trichrome staining of the sagittal sections of wt P13 incisors showed the mineralizing dentin layer (D) stained blue and the organic enamel layer (E) stained red (see Fig. 3e, f). In the age-matched Satb1−/− mice, the blue-stained dentin layer (D) had a thickness similar to wt controls, whereas the enamel layer (between D and SAB) was significantly thinner (see Fig. 3g, h) as compared to controls.

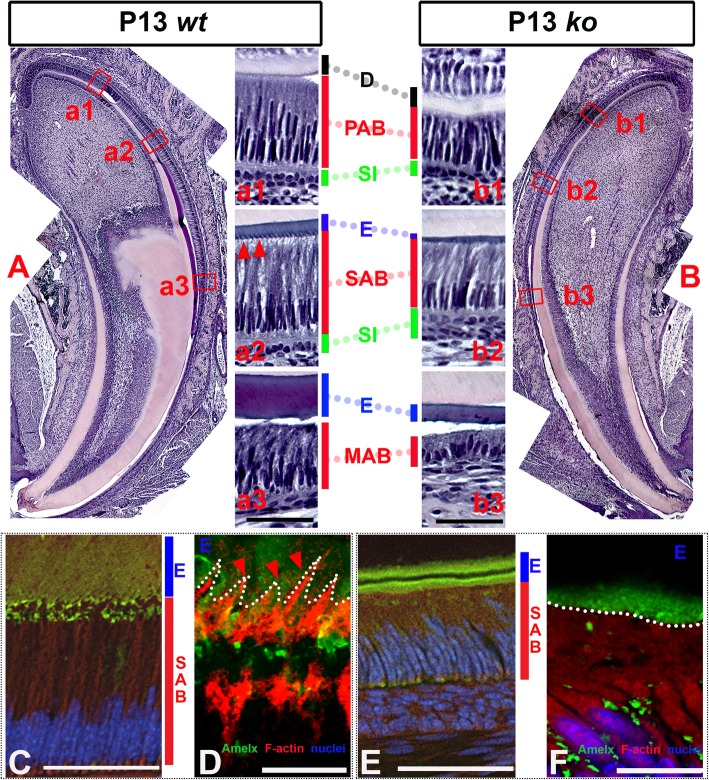

Ameloblast morphodifferentiation is compromised in the Satb1−/− mice

Standard H&E staining of the P13 sagittal sections of the Satb1−/− mouse incisors (see Fig. 4b) showed that compared to controls (see Fig. 4a), the ameloblasts in Satb1−/− mice at all differentiation stages were shorter (see Fig. 4 (b1, b2, b3)). Consistent with those X-ray and trichrome staining results, H&E staining showed a thinner enamel matrix layer (E) in Satb1−/− mouse (see Fig. 4 (b2, b3)) as compared to wt controls (see Fig. 4 (a2, a3)), though the thickness of the dentin layer was not obviously different. With the use of a Nikon W1-SoRA spinning disk super-resolution confocal microscope, at the apical surface of elongated wild-type SABs (see Fig. 4c), picket fence appearance Tomes’ processes were filled with red phalloidin-labeled F-actin (see red triangles in Fig. 4d), but they were lost at the apical surface of Satb1−/− ameloblasts (outlined by white dotted line) (see Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Ameloblast morphology is compromised in the Satb1−/− mouse incisors. a H&E staining of the sagittal sections of the P13 wt mouse incisor shows well-developed PABs adjacent to the mineralizing dentin (in pink); SABs and MABs situate next to the enamel layer (in dark red). (a1) PABs, residing between the dentin matrix (d) and a layer of stratum intermedium (SI), start to elongate and polarize with the nuclei shifting to basal end (closer to SI). (a2) SABs further elongate and polarize to develop ample supranuclear space to accommodate the increased organelles. Tomes’ processes extending into the enamel layer are present at the apical border of SABs, as indicated by red triangles. (a3) H&E staining shows the reduced MAB situated next to mineralizing enamel matrix (e) of wt mouse. b Ameloblasts at all stages are shorter, and the enamel layer is thinner in the Satb1−/− mouse incisor as compared to control. (b1) H&E staining shows the shortened PAB in the Satb1−/− mouse incisor. (b2) SAB in the Satb1−/− mouse incisor was shortened and lacked Tomes’ processes. (b3) Shortened maturation ameloblasts and a thin enamel layer were detected in the Satb1−/− mouse incisor. Scale bar in (a3) applied to (a1) and (a2), and in (b3) applied to (b1) and (b2), 50 μM. The picket fence appearance Tomes’ processes at the apical surface of wt SABs (see c) were visualized by staining the F-actin filament within the cellular protrusion by red fluorescent probe phalloidin, as indicated by red triangles and outlined by the white dotted line (see d). Immunostaining with an anti-amelogenin antibody (in green) shows that Tomes’ processes extended and were embedded into the organic enamel matrix (e). At the apical surface of Satb1−/− SABs (see e), no organized cellular protrusion could be found to extend into the adjacent Satb1−/− enamel matrix (e, labeled in green). The interface between Satb1−/− SAB and e was outlined by a white dotted line (see f). Scale bar in c and e, 50 μM; in panel d and f, 10 μM

Amelogenin secretion is impaired in the Satb1−/− mice

Amelogenins comprise over 90% of the enamel matrix proteins that are synthesized and secreted by ameloblasts during enamel formation. Immunostaining showed that while amelogenins were primarily detected in the enamel matrix (E) residing on SABs in the wt mice (see Fig. 5a), greatly increased intracellular amelogenins were detected in the cytoplasm of Satb1−/− SABs (see Fig. 5b). There was no significant difference in the transcript levels of Amelx, encoding amelogenins, in SABs microdissected from the wt and Satb1−/− mouse molars based on semi-quantitative PCR analysis and Student’s t test (n = 6, P > 0.05).

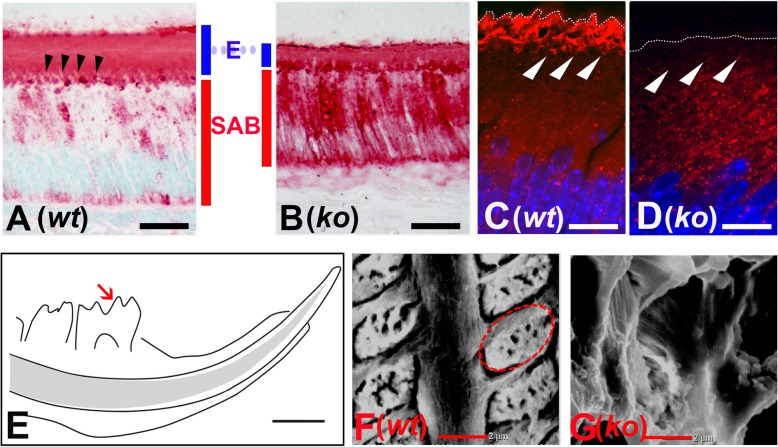

Fig. 5.

Deficiency of amelogenin secretion results in a thin and disorganized enamel layer in Satb1−/− mouse. a Amelogenin immunostaining on a sagittal section of the P13 wt mouse incisor shows amelogenins are primarily detected in the enamel matrix and Tomes’ processes (indicated by black triangles). b A representative sagittal section from the P13 Satb1−/− mouse incisor shows intense amelogenin immunoreactive signal in the shortened ameloblasts, no obvious Tomes’ processes, and a thin layer enamel matrix with a comparable intense immunoreactive signal as that of the control enamel (e). Scale bar in a and b, 25 μM. Rab30 was immunolocalized in the cytoplasm closed to the apical surface of wild-type secretory ameloblasts (as indicated by white triangles) (c). More disperse and intense Rab30 immunostaining signal was detected in the cytoplasm, but not at the apical surface (indicated by white triangles) of Satb1−/− mouse secretory ameloblasts (d). The interface between ameloblasts and the enamel matrix was outlined by a white dotted line. Scale bar in panel c and d, 10 μM. Enamel structure in P13 Satb1−/− mouse teeth is disorganized. e Ground sagittal sections of mouse hemimandible were examined under scanning electron microscope at the position highlighted with a red arrow. f Ordered, well-aligned enamel rods were detected in full width of the wt incisor enamel layer. The red dotted line traces one intact enamel rod, which is fabricated by one ameloblast. g No well-defined structure was visualized in the thin layer of enamel of the Satb1−/− mouse at the corresponding position. Scale bar in e, 1 mm; f and g, 2 μm

We next addressed if the transport of secretory vesicles would be affected in the ameloblasts of the Satb1−/− mice. We focused on Rab30 since it is a key component of the transport vesicles facilitating the fusion of vesicles with a targeting membrane [48]. Our microarray analysis showed that Rab30 was increased in secretory ameloblasts up to 4.9-, 2.5-, and 1.9-fold compared to ES-EC, OE, and PAB respectively. Rab30 immunopositive signal was sparsely distributed in the cytoplasm and was more concentrated close to the apical surface of wt SABs (see Fig. 5c, indicated by white triangles). By contrast, increased numbers of Rab30-containing puncta were detected in the cytoplasm of Satb1−/− SABs, consistent with the increased intracellular amelogenin immunostaining (see Fig. 5d). Semi-quantitative PCR analyses demonstrated that the expression levels of Rab30 gene were similar in Satb1−/− SABs and wt SABs (n = 6, P > 0.05 by Student’s t test). These data indicate that secretory vesicles carrying amelogenins and likely other EMPs cannot be properly transported to the apical plasma membrane in the Satb1−/− SABs for secretion.

Abnormal enamel structure is developed on the Satb1−/− mouse teeth

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images showed that enamel rods with uniform width and architecture were orderly arranged on the P13 wt mouse first molar (see Fig. 5f). No defined enamel rods were observed in the P13 Satb1−/− mouse first molar enamel at a comparable site as controls (see Fig. 5g). This finding suggests a lack of directional secretion of EMPs into the enamel space.

Tight junction complex is altered in the Satb1−/− mouse ameloblasts

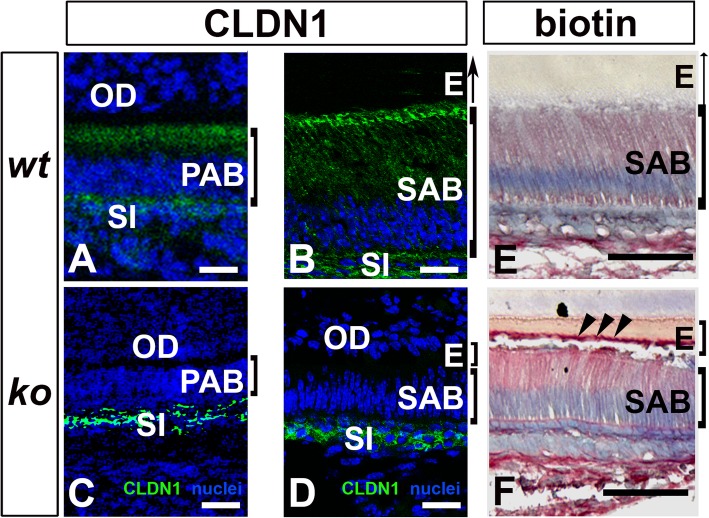

Claudin 1 was immunolocalized primarily at the apical surfaces of presecretory ameloblasts (PAB) and secretory ameloblasts (SAB) and at the membrane of the underlying stratum intermedium (SI) in wt mice (see Fig. 6a, b). In the Satb1−/− mouse incisors, claudin 1 was hardly detected at the apical surface of PAB and SAB (see Fig. 6c, d), though the claudin 1 immunoreactive signal in the stratum intermedium (SI) remained similar to that of control SI (Fig. 6c, d). Impaired claudin 1 distribution indicated the loss of cell polarity in the Satb1−/− ameloblasts.

Fig. 6.

Ameloblast layer’s barrier function is disrupted in Satb1−/− mouse ameloblasts. a Claudin 1 (CLDN1) immunoreactive signal (in green) was detected primarily at the apical end of P1 wt presecretory ameloblasts (PAB) and underlying stratum intermedium (SI) b and P1 wt secretory ameloblasts (SAB) and SI. The cell nuclei were counterstained in blue. c CLDN1 immunoreactive signal in Satb1−/− mouse PAB was primarily localized in SI beneath PAB. d Identical immunostaining pattern was found in SI under the Satb1−/− SAB. OD, odontoblast; E, enamel. Scale bars, 20 μM. e A small amount of injected tracer molecule Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was detected in the enamel matrix (e) adjacent to wt SAB. f Significant more tracer molecule Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was found in the enamel matrix (e) adjacent to Satb1−/− mouse SAB and at the surface of the enamel matrix layer. Scale bars: 50 μM

Tight junctions are critical for epithelial layer integrity and transcellular barrier function. When tracer molecule Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was injected in mice, only a minimal amount of Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was detected in the enamel matrix (E) adjacent to wt SABs (see Fig. 6e). Relatively more Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was found in the enamel matrix (E) adjacent to Satb1−/− SABs, in particular, at the surface of the enamel matrix layer as pointed by the black arrows (see Fig. 6f), as compared to wt controls. These results demonstrated that tight junctions at the apical surface of SABs were impaired by the deletion of SATB1.

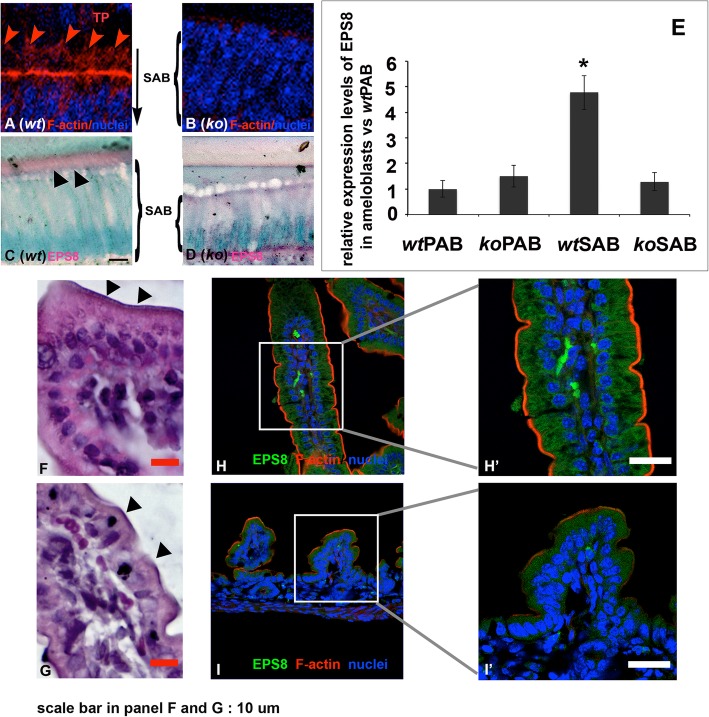

Actin filament assembly at the apical end of SABs is disrupted in the Satb1−/− mice

Claudins are responsible for assembling perijunctional tensile ring/belt of actin filaments at the apical end of polarized columnar epithelial cells [49]. Phalloidin staining showed that the condensed perijunctional tensile ring/belt-like actin filaments were stained in red at the apical end of control SABs (see Fig. 7A). Consistent with the reduced claudin 1 immunostaining, a condensed and orderly actin filament ring/belt-like structure could not be detected at the apical end of Satb1−/− mouse SABs (see Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the branched F-actin bundle was stained in red inside of Tomes’ processes (TP) in the wt mice (see Fig. 7A), which could not be detected at the apical end of Satb1−/− mouse SABs. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (EPS8), previously linked to small intestinal epithelial cytoplasmic protrusion formation [50–53], was mostly immunolocalized in the Tomes’ processes at the apical surface of wt SABs (see Fig. 7C), but not at the same location of Satb1−/− mouse SABs (see Fig. 7D). qPCR analyses on the PABs and SABs collected from the mouse first molars showed that EPS8 was significantly upregulated up to 5.6-fold in wt SABs vs wt PABs (n = 6, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with post hoc tests). However, EPS8 expression levels in Satb1−/− mouse PABs and SABs were similar to those detected in wt PABs (see Fig. 7E). Thus, these data suggest that SATB1 regulates actin filament assembly and Tomes’ process formation through regulating the expression of EPS8 in secretory ameloblasts.

Fig. 7.

The cytoplasmic protrusion of secretory ameloblast and small intestine epithelial cells are deformed in the Satb1−/− mice. A Circumferential F-actin belt-like structure (in red) was detected along the apical end of wt SAB, and branched F-actin bundle was detected in the Tomes’ processes (TP). B No apparent F-actin assembly was detected at the apical end of the Satb1−/− SAB. C EPS8 was immunolocalized in the Tomes’ processes (indicated by black triangles) of wt SAB. D There was no Tomes’ process and concentrated EPS8 signal that could be detected in the Satb1−/− SAB. E qPCR analyses on ameloblasts collected from mouse first molars showed that EPS8 was significantly upregulated up to 5.6-fold in wt SAB vs wt PAB. However, EPS8 expression levels in the Satb1−/− PAB and SAB were similar to that detected in wt PAB. F The well-developed microvilli (indicated by black triangles) were detected along the lining of wt mouse small intestine. G Microvillus layer on the surface of the Satb1−/− mouse small intestine was thinner and less consistent (indicated by black triangles). H, H′ Immunofluorescent staining with EPS8 antibody demonstrated that EPS8 was concentrated and aligned toward wild-type mouse small intestine brush border (in green). Phalloidin-labeled F-actin was well distributed along the brush border (in red). I, I′ EPS8 immunoreactive signal (in green) and F-actin architecture (in red) were less intense and organized at the apical surface of Satb1−/− mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Scale bars in F, G, H′, and I′, 10 μM

In human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231, the expression of EPS8 and CLDN1 genes depends on SATB1 [22], and SATB1 binding sites have been found at multiple sites near and within genes encoding CLDN1 and EPS8 (based on our unpublished ChIP-seq results). To further investigate the regulatory function of SATB1 on the expression of CLDN1 and EPS8, we manipulated the expression levels of SATB1 in human ameloblast-lineage cells (ALCs) using Retro-X™ Tet-On Advanced Inducible Expression System. When SATB1 expression levels increased about 2.5-fold compared to that of non-transduced ALCs, CLDN1 and EPS8 expression levels were about 4.3-fold and 0.43-fold as compared to that of controls, respectively. However, when SATB1 expression levels increased 38-fold, claudin 1 significantly reduced to 0.27-fold, but EPS8 increased to 5-fold as compared to that of non-transduced ALCs (n = 6, P < 0.05). In short, repression of claudin 1 and enhancement of EPS8 by SATB1 could be recapitulated in ALCs by SATB1 overexpression.

Microvilli, constituting the brush border of the small intestine, are an array of actin filament-support apical membrane protrusion of enterocytes [54]. The identical thickness of microvilli (indicated by black arrows in Fig. 7F) was detected along the lining of wt mouse small intestine. Microvillus layer on the surface of Satb1−/− mouse small intestine was thinner and less consistent (see Fig. 7G). In addition, small intestine epithelial cells in Satb1−/− mouse were shorter, and the nuclei were less polarized. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that EPS8 was concentrated at the site of wt mouse small intestine brush border (see Fig. 7H, H′), but was less intense at the apical surface of ko mouse small intestine (see Fig. 7I, I′). There was a threefold reduction in the EPS8 expression levels in the Satb1−/− mouse small intestine as compared to that of controls by qPCR (n = 6, P < 0.05 by Student’s t test). The defective EPS8 expression and microvillus formation in Satb1−/− mouse small intestine epithelial cells further demonstrated the important roles of SATB1 on actin filament assembly and cytoplasmic protrusion formation. Actin filaments underneath the plasma membrane function as cables for short-distance transport, moving the vesicles to fuse with the target membrane [1].

Discussion

Epithelial cell polarity is a feature of asymmetric sequestration of polarity proteins and macromolecules into specific cellular domains. Establishment and maintenance of epithelial cell polarity are critical for many cellular functions, such as cell division, polarized transport, cellular protrusion, and migration [55]. Our studies showed that SATB1 was spatially and temporally upregulated in ameloblast lineage during tooth development. A loss-of-function Satb1−/− mouse model demonstrated that SATB1 is indispensable for ameloblast morphogenesis and normal enamel formation.

Ameloblasts undergo remarkable morphological modulation as they differentiate from cuboidal dental epithelial precursor cells to polarized tall columnar secretory ameloblasts that secrete enamel matrix proteins, composed of 90% amelogenins, to set out the construction of the enamel. Amelogenins are necessary for the hydroxyapatite deposition, growth, and full thickness of enamel formation [56]. Ameloblasts in Satb1−/− mice were shorter in length and lack polarity as compared to wt ameloblasts at all stages. The fact that the Satb1 null mice often die prematurely constrained us to focus on PAB and SAB.

The increased amount of amelogenins in the Satb1−/− mouse SABs, while amelogenin mRNA transcript levels in these cells remained unchanged as compared to that of the controls, indicates defects in amelogenin secretion into the extracellular enamel space. Increased Rab30 dispersed throughout the cytoplasm of Satb1−/− SABs provided additional evidence to demonstrate the vesicle accumulation in these cells. Rab30 was the major member of Rab GTPase family expressed by wt SABs according to the microarray analysis and was primarily localized in the cytoplasm proximal to the nuclei of wt SABs. Rab30 is a key coordinator of eukaryotic intracellular membrane trafficking, primarily associated with vesicle budding and formation along the secretory pathway [48]. A massive accumulation of amelogenins and Rab30 highly accounts for the thin, hypomineralized, and non-prismatic enamel layers on both incisors and molars of the Satb1−/− mice.

Tomes’ processes (TP) are the landmark structures at the apical surface of wt SABs, through which the secretory vesicles fuse with the distal faces of TPs to directionally release EMPs into the enamel matrix [57]. In the Satb1−/− mice, secretory ameloblasts lost their apical Tomes’ processes. As secretory ameloblasts lose polarity and Tomes’ processes, secretory vesicles likely fail to be unidirectionally transported and fused with the plasma membrane. This would impair the directional release of amelogenins and other enamel matrix proteins into the enamel space, resulting in defective enamel. Cytoskeleton organization plays important roles in delivering the vesicles and cargos to the correct domains [58]. Filamentous actin meshwork branches out in Tomes’ processes of wt secretory ameloblasts and are thought to serve as tracks to transport secretory vesicles through the cytoplasm to the secretory face of ameloblast Tomes’ processes [59, 60]. Our data indicated that SATB1 deficiency affected filamentous actin assembly and arrangement underneath the apical plasma membrane of SABs, which might impede the routes for secretory vesicle transporting to secretory front.

There is scant information regarding the molecular mechanisms contributing to the formation of Tomes’ processes. In the intestinal epithelial cells, elongation of F-actin meshwork proximal to the plasma membrane is believed to generate the pushing force for cell protrusion and microvillus formation. Similarly, build-up of an F-actin meshwork might also direct the formation of ameloblast Tomes’ processes. Based on the knowledge learned from intestinal epithelial cells, we know signaling activated by cell-ECM adhesion recruits the formation of focal adhesion complex, which activates the assembly of F-actin branches to anchor cells and generates pushing forces for modulating the cell cortex structure and movement [61, 62]. Similar to the lack of Tomes’ processes in secretory ameloblasts, microvilli in the Satb1−/− mouse small intestinal epithelial cells were deformed as well. We further demonstrated that EPS8 was downregulated in both small intestinal epithelial cells and secretory ameloblasts from Satb1−/− mice. EPS8 is necessary for the formation of small intestinal microvilli, which binds filament actin together to stabilize actin bundling in intestinal epithelial cells [52, 63–65]. We ascertain that EPS8 is one of the SATB1-influenced genes that may be responsible for the cytoplasmic protrusion defect in the Satb1−/− mice. We also found by qPCR analysis that fromin1, a promoter for actin filament nucleation and polymerization [66, 67], was also downregulated in both Satb1−/− mouse secretory ameloblasts and small intestinal epithelial cells by qPCR. We have not been able to confirm the altered distribution pattern of formin1 in the Satb1−/− secretory ameloblasts due to the lack of an antibody. We assume that SATB1 can regulate secretion through regulating the expression of genes associated with cytoskeletal filamentous actin organization.

Another mechanism that may also contribute to the defective enamel in Satb1−/− mice is the increased paracellular permeability between ameloblasts, resulting from the significantly reduced and disorientated claudin 1 distribution at the apical end of ameloblasts when the Satb1 gene is not present. Intercellular tight junctions assemble at the apical end of ameloblasts to physically connect single layer of tall columnar ameloblasts together into a sturdy sheet and control the permeability of molecules and ions through the paracellular space. These structural components are essential for the maintenance of the unique enamel space microenvironment. The increased trans-ameloblastic permeability could potentially affect the ion concentration, osmotic pressure, and pH value in the enamel matrix fluid, in turn, to collectively deteriorate all aspects of enamel formation, including ameloblast-matrix adhesion, cell shaping, enamel matrix protein secretion, and EMP enzymatic processing, which would in turn alter the enamel crystal growth and mineralization.

Secretory ameloblasts have very unique cellular morphology and functions as compared to other epithelial cells, even ameloblasts at other stages. Thus, SAB morphology and functions must be achieved by the coordination of many genes. Through our transcriptome microarray analyses, the second most upregulated transcriptional regulator in SAB is c-Maf. We initially studied the potential link between transcription factor c-Maf and SATB1 and found that c-Maf requires SATB1 for its expression in ameloblasts (see Additional file 3: Figure S3). This is similar to the scenario found during T helper 2 activation, where SATB1 induces c-Maf expression and recruits c-Maf to the promoter region of specific cytokine genes [21]. During ameloblast differentiation, c-Maf as well as other transcriptional regulators, for instance, RNA polymerase II elongation factor (such as ELL2), may be guided by a SATB1 network to be recruited and assembled at specific gene loci to achieve a large-scale gene regulation, enabling ameloblast differentiation.

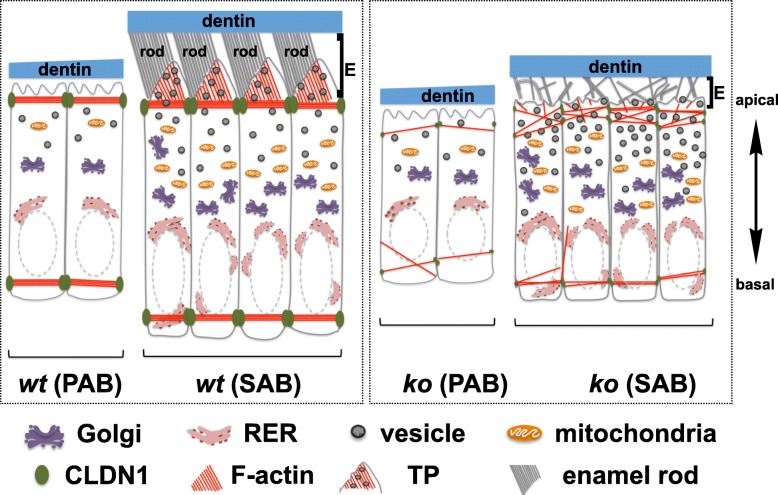

Taken together, our data shows that chromatin organizer SATB1 is temporarily upregulated in epithelially derived ameloblasts and appears to affect ameloblasts’ tight junction formation, polarity, actin filament assembly, Tomes’ process formation, and polarized secretion. All of these events are critical to ameloblast morphodifferentiation and normal enamel formation (illustrated in Fig. 8). These findings suggest the potential application of SATB1, perhaps in concert with other key transcriptional regulators, for enamel regeneration by regulating ameloblast programming from either oral epithelial cells or stem cell-derived epithelial cells.

Fig. 8.

Model of effects of Satb1 deletion on enamel formation. During tooth development, the expression of SATB1 starts in PABs, which attach to the dentin matrix. PABs further elongate and polarize as they differentiate into SABs. Circumferential F-actin belt-like structures are assembled along apical poles, mostly attributing to the locally increased claudin 1 (CLDN1). These F-actin belt-like structures not only physically connect elongated ameloblasts into a sturdy sheet, but also control the contents to be secreted as a sieve. As SABs start to secrete enamel matrix, cells move away from the matrix leaving a cytoplasmic protrusion surrounding by the organic matrix. This protrusion is a histological landmark of SAB, so-called Tomes’ process (TP). The F-actin networks built along the cytoplasmic membrane of the apical surface, likely through the interactions between transmembrane integrins and extracellular matrix proteins, could generate pushing force to facilitate the membrane protrusion and serve as tracks for transporting vesicle/A (secretory vesicles containing amelogenins). TP is responsible for the directional secretion of enamel matrix proteins and the formation of one enamel rod. When Satb1 gene is deleted, PABs are significantly shorter and have barely detectable CLDN1 at the apical pole. Not surprisingly, no F-actin belt orderly assembles at the apical pole of PABs. SABs are continuously shorter compared to controls with significantly reduced CLDN1, deformed F-actin architecture, and no Tomes’ process at its apical end. These defects are believed to account for the amelogenin retention in Satb1−/− ameloblasts and a thin, hypomineralized and disordered enamel phenotype. It is worthy to note that often several claudin family members are co-expressed and interact with each other to regulate the tight junction structure in epithelial cells. This is a simplified schema that primarily focuses on the correlation between SATB1 with CLDN1

Material and methods

To characterize the gene expression profile of stage-specific ameloblasts by whole-transcript microarray analyses

Preparation of human embryonic stem cells into epithelial cells

Human embryonic stem cells (hESC) (NIH-registered WA09 cell line) were purchased from the WiCell Institute (WI, USA). These stem cells were maintained as previously reported, and their differentiation into epithelial cells (ES-ECs) was induced and characterized according to the established protocols [68, 69]. These cells served as controls for microarray analyses.

Laser microdissection of human fetal oral buccal mucosal epithelial cells and ameloblasts

Tissues were collected from 18- to 19-week human aborted fetal cadaver tissues, under guidelines approved by the Committee on Human Research at UCSF, with patients’ consent. Fetal buccal mucosa and maxillae were isolated and embedded in O.C.T. (Tissue-Tek® optimum cutting temperature compound). Those tissues were then cryosectioned at a thickness of 10 μm per section, and consecutive sections were collected on Leica PEN-membrane slides. After stained with hematoxylin & eosin, specific cell types were harvested using a P.A.L.M Laser Dissecting Microscope (Zeiss). Oral buccal mucosal epithelial cells (OE) were collected from the cheek tissues. Presecretory ameloblasts (PABs) were identified as the single layer of columnar epithelial cells directly bordering with the dentin matrix. Secretory ameloblasts (SABs) were identified as the elongated and polarized epithelial cells adjoining to the organic enamel matrix (shown in Fig. 1a). PABs or SABs from three separate maxillae were pooled into one collection tube as a single sample. Three samples were collected for each of four groups, including ES-EC, OE, PAB, and SAB. The microdissected cells were preserved in lysis buffer (RLT buffer) provided by QIAGEN RNeasy Micro kit, 1% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) prior to RNA purification.

Affymetrix whole-transcript human gene 1.0ST microarray

Total RNA was purified from ES-EC, OE, PAB, and SAB cells using RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific), and only the RNA samples with A260:A280 ratio between 7 and 9, determined by a 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies), were subjected to microarray analyses. Fifty nanograms total RNA from each sample was used for RNA amplification and antisense cDNA synthesis with Ovation Pico WTA System (NuGEN Technologies). The biotinylated ST-cDNA probes were generated as previously mentioned [70] and hybridized onto a GeneChip® of Human Gene 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) for 16 h at 45 °C. After hybridization, the array chips were stained with streptavidin phycoerythrin and imaged using an Affymetrix Gene Chip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Significantly differentially expressed gene profile analyses

The robust multichip average (RMA) method was used for background adjustment, quantile normalization, and median polish summarization using Affymetrix Expression Console Software. These normalized and summarized raw data were submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO accession number is GSE75954). RMA data were analyzed using Partex Genomics Suite software (St. Louis, MI) to generate a principal component analysis (PCA) clustering plot. Both R software environment with the Bioconductor affy package [71, 72] and GeneSifter software (Geospiza, Inc., WA) were used to generate the lists of significantly differentially expressed genes in PAB and SAB as compared to non-dental epithelial cells (average expression levels of ES-EC plus OE), using a cutoff of ± 2.0-fold change and p < 0.05. These lists were further analyzed using Exploratory Gene Association Networks (EGAN) software [73] to identify and summarize enriched GO functional pathways; the results of which are reported in Fig. 1b.

Validation of expression levels of genes of interest by semi-quantitative PCR

Total RNA purified from ES-EC, OE, PAB, and SAB cells was used to synthesize cDNA libraries with SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies). Semi-quantitative PCR was performed using the ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems). Primers and corresponding TaqMan® probes used to amplify endogenous control GAPDH and all target genes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. To determine the relative expression level of the target gene, the comparative CT (threshold cycle) method was used [74].

Characterization of enamel mineralization by X-ray analysis

The generation of Satb1−/− mouse model was previously reported by Dr. Kohwi-Shigematsu et al. [27]. The animals were maintained in the UCSF animal care facility, which is a barrier facility, accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Hemimandibles from P13 wt and Satb1−/− mice were radiographed using a Faxitron X-ray system (Hewlett-Packard, Model 43855A) at 30 kV for 2 min at a focal distance of 46 cm with the microfine grain emulsion films (type 4489, Kodak, Rochester, New York).

Characterization of enamel rods by scanning electron microscopy

To characterize the size and arrangement of the enamel rods in wt and Satb1−/− mice using scanning electron microscope, three sets of hemimandibles from P13 wt and Satb1−/− mice were dissected, embedded in epoxy, and polished in a sagittal orientation using a series of SiC paper and diamond polishing suspension. Subsequently, specimens were etched with 10 mM HCl for 60 s. Specimens were sputter-coated with Au–Pd, and enamel layers of the first molar were imaged at 10 kV using a NeoScope SEM (JEOL) as described previously [75].

Characterization of the histomorphometry of the enamel matrix and ameloblasts

We used the continuously growing mouse incisors, including all developmental stages of ameloblasts on a single entity, to characterize ameloblast/enamel phenotype from wt and Satb1−/− mice. We determined the distribution of SATB1 and proteins associated with epithelial apical polarity (CLDN1:claudin 1), actin filament assembly (EPS8), and vesicle membrane fusion (Rab30). Adult C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized with 240 mg/kg tribromoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and perfuse-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The hemimandibles were dissected and post-fixed with 4% PFA for 24 h at 4 °C followed by decalcification in 8% EDTA at 4 °C for 4 weeks. The hemimandibles were then processed, embedded, and sectioned sagittally. The sections were stained with either H&E or Goldman’s trichrome for ameloblast and enamel matrix phenotypical analyses [76].

For immunostaining, the sagittal sections were boiled in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min to retrieve antigens. Next, the sections were incubated with 10% swine and 5% goat sera followed by incubation with primary antibodies recognized antigens SATB1 (abcam®), CLDN1 (abcam®), EPS8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rab30 (Novus Biologicals), or amelogenins [77] overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with biotin- or fluorescein-conjugated species-specific secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. To detect the biotin-labeled antibody, the sections were next incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min then incubated with Vector® Red kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) to reveal positive reactivity indicated by the presence of pink/red precipitating reaction product. Counter-staining was performed with methyl green (Dako). The sections incubated with fluorescein were then counterstained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst (Life Technologies).

To label cytoskeleton filamentous actin, the hemimandibles collected from P1 wt and Satb1−/− mice were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/cytoskeleton-stabilizing BRB80 buffer (80 mM PIPES; 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 6.8) at 37 °C for 2 h then embedded in the OCT compound. Incisor sagittal cryosections with a thickness of 5 μm for each were collected. After blocking with 3% BSA, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 594-phalloidin (Life Technologies) for 20 min to label F-actin. After stringent washes, the cell nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/ml. The slides were imaged using a high-resolution and high-speed Leica TCS SP5 spectrum confocal microscope or a Nikon W1-SoRA spinning disk super-resolution confocal microscope.

Characterization of the transcellular barrier function of secretory ameloblast layer of wt and Satb1−/− mice

The apical tight junction is an important indicator for ameloblast polarity and can be measured by the functional selectivity of the paracellular apical barrier. Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was used as a tracer molecule to evaluate the effects of SATB1 on the ameloblast layer barrier function as previously described [78]. Briefly, four 10-day old pups from each wt and Satb1−/− mouse model were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 0.05 ml/10 g of ketamine (18 mg/ml). A 30-G injection needle with a blunt end was carefully inserted into the left ventricle of the heart, and 150 μl/g of Sulfo-NHS-Biotin solution was perfused into the bloodstream. Ten minutes after receiving Sulfo-NHS-Biotin injection, the pups were sacrificed, and the hemimandibles were dissected, processed, and paraffin-embedded for histological sectioning as previously mentioned. The sagittal sections were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min, and immunoreactivity was visualized using a Vector® Red kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.).

Measurement of the relative amelogenin expression levels in Satb1−/− mouse ameloblasts

After euthanizing with carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation, the mandibles were dissected from P5 control and Satb1−/− mice. Ameloblasts were removed from the first molars, which have the enamel primarily at the secretory stage [79] were microdissected from the surface of the teeth. The total RNA was then purified, and qPCR was performed to determine the relative amounts of amelogenin mRNA in microdissected controls as compared to Satb1−/− SABs. The primer sequences for the amelogenin gene were as follows: mouse amelogenin sense-GGGACCTGGATTTTGTTTGCC, antisense-TTCAAAGGGGTAAGCACCTCA.

Investigation of the effects of overexpressed SATB1 on primary human ameloblast lineage cells

Human ameloblast lineage cells (hALCs) were harvested from the tooth buds as mentioned above. We followed the protocol previously established in our laboratory to maintain these cells [80–82]. As the first passage of hALCs reached 80% confluence, the KGM2 medium was replaced with a D-MEM medium with 10% FBS and 5 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Following Clontech’s Retro-X™ Tet-On Advanced Inducible Expression System manufacturer instructions, expression vector pRetroX-Tight-Pur-human Satb1 cDNA and env expression vector pVSV-G were co-transfected into packaging GP2-293 cells to produce retrovirus stocks. Next, retrovirus was used to infect the hALCs transduced with RetroX-Tet-On expression system. Double-stable hALCs were selected with 400 μg/ml G418 and 1 μg/ml purimycine. Afterwards, 500 ng/ml doxycycline was supplemented to the culture medium to induce the expression of SATB1. The relative expression levels of SATB1 by cells multiplied from each individual clone were measured by qPCR. Two clones with distinctive expression levels of SATB1 were further analyzed for the relative expression levels of CLDN1 and EPS8. The sequences of the primers were as follows: human SATB1 sense-TCGGGCCATCTGATGAAAACC, antisense-CCAACCTGGATTAGCCCTTTG; human CLDN1 sense-CGATGAGGTGCAGAAGATGA, antisense-AAGGCAGAGAGAAGCAGCAG; human EPS8 sense-TCTTCACCACCCTATTCCCAG, antisense-CATCTTTCCGATCCAGCACGA; human GAPDH sense-CATGAGAAGTATGACAACAG, antisense-GTGATGGCATGGACTGTGGT.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Principal component analysis (PCA) shows a scatter plot of variables of four target cell types, as analyzed using the Partex Genomic Suite software. In this plot, each sphere represents one sample. Spheres in the same color represent three triplicate samples of each cell type. The distance between any groups of cell type is related to the similarity between the two observations in the biplot. This result is depicted two dimensionally with PC1 (34.4%) and PC2 (13.3%) as the X and Y axes, respectively. This mapping indicated that variables of PABs and SABs scattered more closely to each other than to others meaning their closer biological relevance during development. (PSD 1137 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Quantitative PCR verified that genes associated with ameloblast morphogenesis and enamel matrix mineralization are significantly upregulated in microdissected human ameloblasts, in a similar pattern shown by microarray analysis. Genes associated with ameloblast morphogenesis including CLDN1 and ITGA2, enamel matrix formation including AMELX, AMBN, ENAM, MMP20, AMTN, DSPP, DMP1 and ALP, and two transcriptional regulators SATB1 and c-Maf, not previously connected with amelogenesis, were confirmed to be specifically upregulated in PAB and SAB by qPCR. (PSD 1104 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S3. c-Maf protein is reduced in Satb1-/- mouse incisor ameloblasts. A) In wt P13 mouse incisor, positive c-Maf immunostaining signal was visualized in cells within cervical loop (CL, a1), more intensely in presecretory ameloblasts (PAB, a2), less intensely in secretory ameloblasts (SAB, a3), again increased in transitional stage ameloblasts (TAB, a4) and least intensely in early maturation stage ameloblasts (MAB, a5). B) In P13 Satb1-/- mouse incisors, c-Maf immunoreactive signal was reduced in all stages of ameloblasts (b1-b5). Immunoreactivity appeared to be unaffected in the stratum intermedium (SI) and papillary layer (PL) (b2-b5) when Satb1 gene is deleted. Scale bar in a1 applied to a2-5 and b1-b5: 20 μM. (PSD 10438 kb)

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the NIDCR grant R03 DE019507-02 and R01 DE027076 and funds from School of Dentistry at UCSF to YZ, NIDCR grant R56 DE13508 to PDK, and NCI grant R37CA39681, NIESH grant ES023854, and NIAMSD grant AR064580 to TK-S.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The microarray data associated with this study has been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus database, accession number GSE75954.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human embryonic tissues were collected under guidelines approved by the Committee on Human Research at UCSF (BUA number: BU034548-04B), with patients’ written consent. The experiments and data collection had been performed in accordance with the Declarations of Helsinki. Mouse studies were approved by UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC), with protocol number AN177146-02.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12915-019-0722-9.

References

- 1.Schneeberger Kerstin, Roth Sabrina, Nieuwenhuis Edward E. S., Middendorp Sabine. Intestinal epithelial cell polarity defects in disease: lessons from microvillus inclusion disease. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2018;11(2):dmm031088. doi: 10.1242/dmm.031088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inman JL, Bissell MJ. Apical polarity in three-dimensional culture systems: where to now? J Biol. 2010;9:2. doi: 10.1186/jbiol213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravindran S, George A. Dentin matrix proteins in bone tissue engineering. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;881:129–142. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22345-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harada H, Kettunen P, Jung HS, Mustonen T, Wang YA, Thesleff I. Localization of putative stem cells in dental epithelium and their association with Notch and FGF signaling. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:105–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jussila M, Thesleff I. Signaling networks regulating tooth organogenesis and regeneration, and the specification of dental mesenchymal and epithelial cell lineages. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a008425. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim A, Warshawsky H. The effect of colcemid on the structure and secretory activity of ameloblasts in the rat incisor as shown by radioautography after injection of 3H-proline. Anat Rec. 1979;195:587–609. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091950403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Simmer JP, Sarte P, Lau EC, Diekwisch T, Slavkin HC. Self-assembly of a recombinant amelogenin protein generates supramolecular structures. J Struct Biol. 1994;112:103–109. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1994.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Diekwisch TG, Lyaruu DM, Wright JT, Bringas P, Jr, Slavkin HC. Evidence for amelogenin “nanospheres” as functional components of secretory-stage enamel matrix. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:50–59. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moradian-Oldak J, Leung W, Fincham AG. Temperature and pH-dependent supramolecular self-assembly of amelogenin molecules: a dynamic light-scattering analysis. J Struct Biol. 1998;122:320–327. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moradian-Oldak J, Paine ML, Lei YP, Fincham AG, Snead ML. Self-assembly properties of recombinant engineered amelogenin proteins analyzed by dynamic light scattering and atomic force microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2000;131:27–37. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanci A, Uchida T, Warshawsky H. The effects of vinblastine on the secretory ameloblasts: an ultrastructural, cytochemical, and immunocytochemical study in the rat incisor. Anat Rec. 1987;219:113–126. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092190203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CE. Cellular and chemical events during enamel maturation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:128–161. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett JD. Dental enamel development: proteinases and their enamel matrix substrates. ISRN Dent. 2013;2013:684607. doi: 10.1155/2013/684607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacruz RS, Smith CE, Kurtz I, Hubbard MJ, Paine ML. New paradigms on the transport functions of maturation-stage ameloblasts. J Dent Res. 2013;92:122–129. doi: 10.1177/0022034512470954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacruz RS, Smith CE, Chen YB, Hubbard MJ, Hacia JG, Paine ML. Gene-expression analysis of early- and late-maturation-stage rat enamel organ. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(Suppl 1):149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibata S, Suzuki S, Tengan T, Yamashita Y. A histochemical study of apoptosis in the reduced ameloblasts of erupting mouse molars. Arch Oral Biol. 1995;40:677–680. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(95)00021-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yajima-Himuro S, Oshima M, Yamamoto G, Ogawa M, Furuya M, Tanaka J, Nishii K, Mishima K, Tachikawa T, Tsuji T, Yamamoto M. The junctional epithelium originates from the odontogenic epithelium of an erupted tooth. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4867. doi: 10.1038/srep04867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson LA, Joh T, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell. 1992;70:631–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90432-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasui D, Miyano M, Cai S, Varga-Weisz P, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 targets chromatin remodelling to regulate genes over long distances. Nature. 2002;419:641–645. doi: 10.1038/nature01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai S, Han HJ, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Tissue-specific nuclear architecture and gene expression regulated by SATB1. Nat Genet. 2003;34:42–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1278–1288. doi: 10.1038/ng1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han HJ, Russo J, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 reprogrammes gene expression to promote breast tumour growth and metastasis. Nature. 2008;452:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature06781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kohwi Y, Takahashi K, Richards HW, Ayers SD, Han HJ, Cai S. SATB1-mediated functional packaging of chromatin into loops. Methods. 2012;58:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao B, Naik AK, Watanabe A, Tanaka H, Chen L, Richards HW, Kondo M, Taniuchi I, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Krangel MS. An anti-silencer- and SATB1-dependent chromatin hub regulates Rag1 and Rag2 gene expression during thymocyte development. J Exp Med. 2015;212:809–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Wang Z, Sun L, Shao L, Yang N, Yu D, Zhang X, Han X, Sun Y. SATB1 mediates long-range chromatin interactions: a dual regulator of anti-apoptotic BCL2 and pro-apoptotic NOXA genes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitagawa Y, Ohkura N, Kidani Y, Vandenbon A, Hirota K, Kawakami R, Yasuda K, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Kondo M, Taniuchi I, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Sakaguchi S. Guidance of regulatory T cell development by Satb1-dependent super-enhancer establishment. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:173–183. doi: 10.1038/ni.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarez JD, Yasui DH, Niida H, Joh T, Loh DY, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:521–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. Proteinases in developing dental enamel. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:425–441. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100040101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwasaki K, Bajenova E, Somogyi-Ganss E, Miller M, Nguyen V, Nourkeyhani H, Gao Y, Wendel M, Ganss B. Amelotin--a novel secreted, ameloblast-specific protein. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1127–1132. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki T, Higashi S, Tachikawa T, Yoshiki S. Formation of tight junctions in differentiating and secretory ameloblasts of rat molar tooth germs. Arch Oral Biol. 1982;27:1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(82)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joao SM, Arana-Chavez VE. Tight junctions in differentiating ameloblasts and odontoblasts differentially express ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1 in early odontogenesis of rat molars. Anat Rec Part A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;277:338–343. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inai T, Sengoku A, Hirose E, Iida H, Shibata Y. Differential expression of the tight junction proteins, claudin-1, claudin-4, occludin, ZO-1, and PAR3, in the ameloblasts of rat upper incisors. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:577–585. doi: 10.1002/ar.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He P, Zhang Y, Kim SO, Radlanski RJ, Butcher K, Schneider RA, DenBesten PK. Ameloblast differentiation in the human developing tooth: effects of extracellular matrices. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson GW, Mahon KA. Differential and overlapping expression domains of Dlx-2 and Dlx-3 suggest distinct roles for distal-less homeobox genes in craniofacial development. Mech Dev. 1994;48:199–215. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Z, Stock D, Buchanan A, Weiss K. Expression of Dlx genes during the development of the murine dentition. Dev Genes Evol. 2000;210:270–275. doi: 10.1007/s004270050314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price JA, Bowden DW, Wright JT, Pettenati MJ, Hart TC. Identification of a mutation in DLX3 associated with tricho-dento-osseous (TDO) syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:563–569. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright JT, Kula K, Hall K, Simmons JH, Hart TC. Analysis of the tricho-dento-osseous syndrome genotype and phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:197–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19971017)72:2<197::AID-AJMG14>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fessing MY, Mardaryev AN, Gdula MR, Sharov AA, Sharova TY, Rapisarda V, Gordon KB, Smorodchenko AD, Poterlowicz K, Ferone G, Kohwi Y, Missero C, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Botchkarev VA. p63 regulates Satb1 to control tissue-specific chromatin remodeling during development of the epidermis. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:825–839. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Notani D, Gottimukkala KP, Jayani RS, Limaye AS, Damle MV, Mehta S, Purbey PK, Joseph J, Galande S. Global regulator SATB1 recruits beta-catenin and regulates T(H)2 differentiation in Wnt-dependent manner. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burute M, Gottimukkala K, Galande S. Chromatin organizer SATB1 is an important determinant of T-cell differentiation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:852–859. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satoh Y, Yokota T, Sudo T, Kondo M, Lai A, Kincade PW, Kouro T, Iida R, Kokame K, Miyata T, Habuchi Y, Matsui K, Tanaka H, Matsumura I, Oritani K, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kanakura Y. The Satb1 protein directs hematopoietic stem cell differentiation toward lymphoid lineages. Immunity. 2013;38:1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kondo M, Tanaka Y, Kuwabara T, Naito T, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Watanabe A. SATB1 plays a critical role in establishment of immune tolerance. J Immunol. 2016;196:563–572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakugawa K, Kojo S, Tanaka H, Seo W, Endo TA, Kitagawa Y, Muroi S, Tenno M, Yasmin N, Kohwi Y, Sakaguchi S, Kowhi-Shigematsu T, Taniuchi I. Essential roles of SATB1 in specifying T lymphocyte subsets. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1176–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balamotis MA, Tamberg N, Woo YJ, Li J, Davy B, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kohwi Y. Satb1 ablation alters temporal expression of immediate early genes and reduces dendritic spine density during postnatal brain development. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:333–347. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05917-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skowronska-Krawczyk D, Ma Q, Schwartz M, Scully K, Li W, Liu Z, Taylor H, Tollkuhn J, Ohgi KA, Notani D, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Rosenfeld MG. Required enhancer-matrin-3 network interactions for a homeodomain transcription program. Nature. 2014;514:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Poterlowicz K, Ordinario E, Han HJ, Botchkarev VA, Kohwi Y. Genome organizing function of SATB1 in tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fromberg A, Engeland K, Aigner A. The special AT-rich sequence binding protein 1 (SATB1) and its role in solid tumors. Cancer Lett. 2018;417:96–111. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly EE, Giordano F, Horgan CP, Jollivet F, Raposo G, McCaffrey MW. Rab30 is required for the morphological integrity of the Golgi apparatus. Biol Cell. 2012;104:84–101. doi: 10.1111/boc.201100080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nusrat A, Giry M, Turner JR, Colgan SP, Parkos CA, Carnes D, Lemichez E, Boquet P, Madara JL. Rho protein regulates tight junctions and perijunctional actin organization in polarized epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10629–10633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Disanza A, Carlier MF, Stradal TE, Didry D, Frittoli E, Confalonieri S, Croce A, Wehland J, Di Fiore PP, Scita G. Eps8 controls actin-based motility by capping the barbed ends of actin filaments. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/ncb1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offenhauser N, Borgonovo A, Disanza A, Romano P, Ponzanelli I, Iannolo G, Di Fiore PP, Scita G. The eps8 family of proteins links growth factor stimulation to actin reorganization generating functional redundancy in the Ras/Rac pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:91–98. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-06-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tocchetti A, Soppo CB, Zani F, Bianchi F, Gagliani MC, Pozzi B, Rozman J, Elvert R, Ehrhardt N, Rathkolb B, Moerth C, Horsch M, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Beckers J, Klingenspor M, Wolf E, Hrabe de Angelis M, Scanziani E, Tacchetti C, Scita G, Di Fiore PP, Offenhauser N. Loss of the actin remodeler Eps8 causes intestinal defects and improved metabolic status in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welsch T, Endlich K, Giese T, Buchler MW, Schmidt J. Eps8 is increased in pancreatic cancer and required for dynamic actin-based cell protrusions and intercellular cytoskeletal organization. Cancer Lett. 2007;255:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crawley SW, Mooseker MS, Tyska MJ. Shaping the intestinal brush border. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:441–451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201407015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Macara IG. Organization and execution of the epithelial polarity programme. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:225–242. doi: 10.1038/nrm3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibson CW, Yuan ZA, Hall B, Longenecker G, Chen E, Thyagarajan T, Sreenath T, Wright JT, Decker S, Piddington R, Harrison G, Kulkarni AB. Amelogenin-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31871–31875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kallenbach E. The fine structure of Tomes’ process of rat incisor ameloblasts and its relationship to the elaboration of enamel. Tissue Cell. 1973;5:501–524. doi: 10.1016/S0040-8166(73)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raman R, Pinto CS, Sonawane M. Polarized organization of the cytoskeleton: regulation by cell polarity proteins. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:3565–3584. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishikawa S. Correlation of the arrangement pattern of enamel rods and secretory ameloblasts in pig and monkey teeth: a possible role of the terminal webs in ameloblast movement during secretion. Anat Rec. 1992;232:466–478. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishikawa S, Kawamoto T. Planar cell polarity protein localization in the secretory ameloblasts of rat incisors. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:376–385. doi: 10.1369/0022155412438887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zamir E, Geiger B. Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3583–3590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stricker J, Falzone T, Gardel ML. Mechanics of the F-actin cytoskeleton. J Biomech. 2010;43:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lie PP, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) is a novel regulator of cell adhesion and the blood-testis barrier integrity in the seminiferous epithelium. FASEB J. 2009;23:2555–2567. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-070573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zwaenepoel I, Naba A, Da Cunha MM, Del Maestro L, Formstecher E, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin regulates microvillus morphogenesis by promoting distinct activities of Eps8 proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1080–1094. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-07-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roffers-Agarwal J, Xanthos JB, Miller JR. Regulation of actin cytoskeleton architecture by Eps8 and Abi1. BMC Cell Biol. 2005;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pring M, Evangelista M, Boone C, Yang C, Zigmond SH. Mechanism of formin-induced nucleation of actin filaments. Biochemistry. 2003;42:486–496. doi: 10.1021/bi026520j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dominguez R. Structural insights into de novo actin polymerization. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng LW, Linthicum L, DenBesten PK, Zhang Y. The similarity between human embryonic stem cell-derived epithelial cells and ameloblast-lineage cells. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Metallo Christian M., Ji Lin, de Pablo Juan J., Palecek Sean P. Retinoic Acid and Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling Synergize to Efficiently Direct Epithelial Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(2):372–380. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Kim JY, Horst O, Nakano Y, Zhu L, Radlanski RJ, Ho S, Besten PK. Fluorosed mouse ameloblasts have increased SATB1 retention and Galphaq activity. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Team RC. A language and environment for statistical computing. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paquette J, Tokuyasu T. EGAN: exploratory gene association networks. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:285–286. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Habelitz S. Materials engineering by ameloblasts. J Dent Res. 2015;94:759–767. doi: 10.1177/0022034515577963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldner J. A modification of the masson trichrome technique for routine laboratory purposes. Am J Pathol. 1938;14:237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu J, Huang T, Li T, Guo Z, Cheng L. C-Maf is required for the development of dorsal horn laminae III/IV neurons and mechanoreceptive DRG axon projections. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5362–5373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6239-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ding L, Zhang Y, Tatum R, Chen YH. Detection of tight junction barrier function in vivo by biotin. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;762:91–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-185-7_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith CE, Nanci A. A method for sampling the stages of amelogenesis on mandibular rat incisors using the molars as a reference for dissection. Anat Rec. 1989;225:257–266. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092250312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DenBesten PK, Machule D, Zhang Y, Yan Q, Li W. Characterization of human primary enamel organ epithelial cells in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yan Q, Zhang Y, Li W, Denbesten PK. Micromolar fluoride alters ameloblast lineage cells in vitro. J Dent Res. 2007;86:336–340. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Y, Li W, Chi HS, Chen J, Denbesten PK. JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway mediates the fluoride-induced down-regulation of MMP-20 in vitro. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials