Abstract

Changes of complement and oxidative stress parameters in patients with acute cerebral infarction (ACI) or cerebral hemorrhage (CH), and their clinical significance were explored. A total of 122 patients with ACI or CH admitted to the People's Hospital of Zhangqiu Area from August 2018 to September 2019 were collected. There were 59 ACI patients assigned into a cerebral infarction group (CIG) and further 63 CH patients in a cerebral hemorrhage group (CHG). Additionally, 53 healthy people in physical examination during the same period were enrolled as a control group (CG). Both the CIG and the CHG were treated with edaravone, Xueshuantong, brain protein hydrolysates, aspirin and statin-related drugs. The levels of complement C3, complement C4, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) were determined. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to analyze the predictive value of C3, C4, SOD and TAG in ACI and CH, and logistic regression was used to analyze the risk factors of stroke. Both CIG and CHG showed higher C3 level, and lower C4, SOD and TAC levels than the CG. The NIHSS <4 group and the NIHSS ≥4 group showed higher hs-C3 level, and lower SOD and TAC levels than the CG (all P<0.05), and the NIHSS <4 group showed lower C3 level and lower SOD and TAC levels than the NIHSS ≥4 group (all P<0.05). Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were independent risk factors of stroke. The serum complement and oxidative stress parameters in patients with ACI or CH can be determined through routine examination, and the nerve function deficit could be assessed by determining the complement and oxidative stress parameters in clinical practice.

Keywords: complement, oxidative stress, cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage

Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death in the world, accounting for 11.8% of all the reasons of deaths (1). Cerebral infarction and CH are two common cerebrovascular diseases, which usually lead to severe disability and even death (2–5). Although some neurological scales such as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the Modified Rankin Scale (MRS) have the ability of predicting the prognosis of stroke patients, the prognosis of patients with apraxia, aphasia or disorientation is difficult to evaluate with scales (6).

According to relevant studies, cerebral infarction will bring harmful incidents such as oxidative stress, neuronal excitatory toxicity, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, microvascular injury, and ischemic inflammation, resulting in irreversible damage to brain tissue (7,8). In the early stage of CH, the toxicity of plasma extravasation components including blood-derived coagulation factors, complement, immunoglobulins, and other bioactive molecules is considered to be one of the causes of CH-induced tissue damage, and during CH, hematoma components are the trigger of inflammatory response that can aggravate hemorrhagic brain injury (9,10). Therefore, it is essential to actively search for some specific serum markers such as peripheral biomarkers of related inflammation and oxidative stress markers to analyze the occurrence and prognosis of CH and cerebral infarction.

However, there are few studies on the changes of complement and oxidative stress parameters in patients with acute cerebral infarction (ACI) or cerebral hemorrhage (CH) and their clinical significance. Therefore, this study tested complement and oxidative stress parameters in the serum of such patients and analyzed their clinical significance, so as to provide certain clinical guidance for the two diseases.

Patients and methods

General data

A total of 122 patients with ACI or CH admitted to the People's Hospital of Zhangqiu Area (Jinan, China) from August 2018 to September 2019 were collected, among which 59 ACI patients were assigned into a cerebral infarction group (CIG) and other 63 CH patients were assigned into a cerebral hemorrhage group (CHG). Moreover, 53 healthy people in physical examination during the same period were enrolled as a control group (CG), and the CG consisted of people aged between 24 and 69 years, with an average age of 45.23±15.54 years.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of the CIG and the CHG were as follows: Patients confirmed with cerebral infarction or CH based on CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), patients admitted to the hospital within 24 h after the onset of the disease, patients without shock or surgical indicators, patients who had not recently taken any immune preparations or anti-inflammatory drugs. The inclusion criterion of the CG was as follows: Patients judged as healthy people based on their physical examination results. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with cardiopulmonary insufficiency, hepatic or kidney function obstacle, or a malignant tumor, patients comorbid with infection, and patients with traumatic CH, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Zhangqiu Area and all patients and their families signed informed consent forms.

Treatment

Both the CIG and the CHG were comprehensively treated with edaravone, Xueshuantong, brain protein hydrolysates, aspirin and statin-related drugs.

Methods

The levels of complement C3 (C3), complement C4 (C4), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in the serum of the patients were determined, and the levels in the patients with different nerve function deficits were also determined. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to analyze the predictive value of C3, C4, SOD and TAG in ACI and CH, and logistic regression was used to analyze the risk factors of stroke.

Determination methods

Determination of serum C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels

Fasting venous blood was sampled from the patients on the morning of the third day after admission, and determined using the immune scatter turbidity. The serum C3 and C4 levels were determined using a ADVIA2400 automatic biochemistry analyzer and corresponding kit, and the serum SOD and TAC levels were determined using colorimetry with a SOD detection kit from Dojindo, a total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) determination kit from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, and a ADVIA2400 automatic biochemistry analyzer.

Determination of serum C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels in patients with different nerve function deficits

Patients in the CIG and the CHG were divided into a NIHSS <4 group and a NIHSS ≥4 group according to their nerve function deficits based on NIHSS (11). NIHSS indicates mild disease with a score <4 points, moderate disease with a score between 4–15 points, and severe disease with a score >15 points.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 (Asia Analytics Formerly SPSS China) was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD, and comparison was performed using the Students t-test, while enumeration data were expressed by rate, and comparison was performed using the χ2 test. Comparison among multiple groups was carried out by the Analysis of variance. ROC curves were adopted to analyze the predicative value of C3, C4, SOD and TAC in stroke, and Logistic regression to analyze risk factors of stroke.

Results

General clinical data

There was no significant difference in sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, drinking, and place of residence among the three groups (all P>0.05), while there were differences in hyperlipidemia and hypertension among them (both P<0.05) (Table I).

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Upstream sequence | Downstream sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| U6 | 5′-TCTCTGCTCCTCGTTCGA-3′ | 5′-GCGCCCATACGACCAAATC-3′ |

| miR-122a | 5′-CAAGCGTTGGAGTGTGACA-3′ | 5′-CGTCCTACCATTCTCCAGC-3′ |

Determination of serum C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels

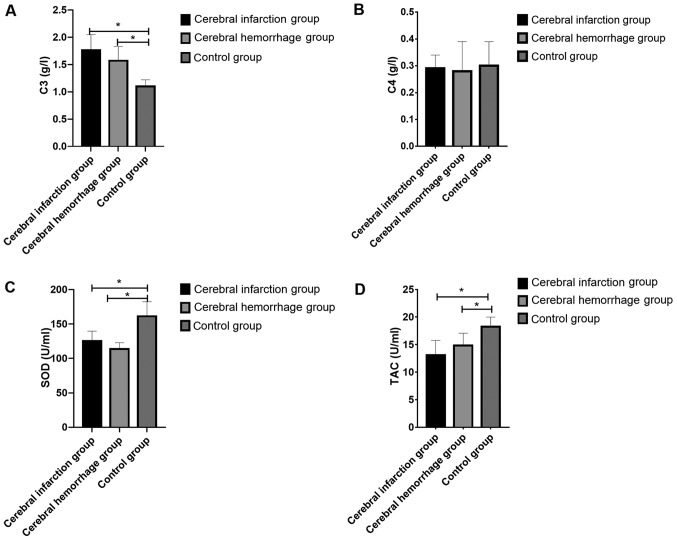

The C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels in the CIG were 1.76±0.2 g/l, 0.29±0.05 g/l, 125.35±14.23 U/ml and 13.07±2.69 U/ml, respectively; those of the CHG were 1.57±0.26 g/l, 0.28±0.1 g/l, 113.62±9.14 U/ml and 14.83±2.25 U/ml, respectively, and those of the CG were 1.10±0.12 g/l, 0.30±0.09 g/l, 161.20±21.12 U/ml and 18.24±1.75 U/ml, respectively. It was apparent that the CIG and the CHG showed significantly higher C3 level and significantly lower C4, SOD and TAC levels than the CG (all P<0.05). It was also shown that there were significant differences in C3, SOD and TAC levels among the three groups (all P<0.05), but no significant difference among them in C4 level (P>0.05), and there was no significant difference between the CIG and the CHG in C3, C4, SOD and HCY levels (all P>0.05) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Determination of serum C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels. (A) The C3 level in the CIG and the CHG was higher than that in the CG. (B) The C4 level in the CIG and the CHG was lower than that in the CG. (C) The SOD level in the CIG and the CHG was lower than that in the CG. (D) The TAC level in the CIG and the CHG was lower than that in the CG. *P<0.05 compared with the CG. TAC, total antioxidant capacity; CIG, cerebral infarction group; CHG, cerebral hemorrhage group; CG, control group; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Determination of serum C3, SOD and TAC levels in the patients with different nerve function deficits

According to the NIHSS, 71 patients were assigned into the NIHSS <4 group, and 51 patients were assigned into the NIHSS ≥4 group. Both groups showed higher hs-C3 level, and lower SOD and TAC levels than the CG, and the NIHSS <4 group showed lower C3, SOD and TAC levels than the NIHSS ≥4 group (all P<0.05) (Table II).

Table II.

Clinical basic data [n (%)].

| Research group (32) | Control group (30) | χ2 or t value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.8±10.6 | 51.2±10.3 | 0.151 | 0.881 |

| Sex | 0.209 | 0.647 | ||

| Male | 21 (65.63) | 18 (60.00) | ||

| Female | 11 (34.38) | 12 (40.00) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.26±0.37 | 22.21±0.25 | 0.618 | 0.538 |

| Marital status | 0.242 | 0.623 | ||

| Married | 29 (90.63) | 26 (86.67) | ||

| Unmarried | 3 (9.38) | 4 (13.33) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.011 | 0.915 | ||

| Han | 22 (68.75) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Ethnic minorities | 10 (31.25) | 9 (30.00) | ||

| Place of residence | 0.501 | 0.479 | ||

| Cities and towns | 18 (56.25) | 19 (63.33) | ||

| Countryside | 14 (43.75) | 11 (36.67) | ||

| History of smoking | 29.370 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 30 (93.75) | 8 (26.67) | ||

| No | 2 (6.25) | 22 (73.33) | ||

| History of drinking | 25.930 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4 (12.50) | 23 (76.67) | ||

| No | 28 (87.50) | 7 (23.33) | ||

| Exercise habits | 0.047 | 0.829 | ||

| Yes | 13 (40.63) | 13 (43.33) | ||

| No | 19 (59.38) | 17 (56.67) |

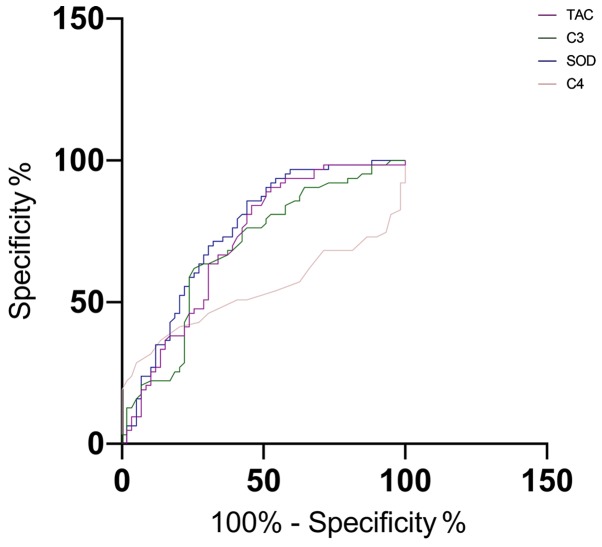

The predictive value of C3, C4, SOD and TAC for stroke

The area-under-the-curve (AUC), critical value, sensitivity, and specificity of C3 in predicting stroke were 0.687, 36.48, 63.49 and 71.19, respectively; those of C4 were 0.540, 23.49, 31.75 and 89.83, respectively; those of SOD were 0.750, 41.65, 85.71 and 54.24, and those of TAC were 0.714, 38.36, 82.54 and 54.24, respectively (Table III and Fig. 2).

Table III.

ROC diagnosis.

| miR-122a | |

|---|---|

| AUC | 0.770 |

| Std. error | 0.057 |

| 95% CI | 0.659–0.881 |

| P-value | 0.001 |

| Cut-off | 4.105 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 82.22 |

| Specificity (%) | 68.75 |

AUC, area-under-the-curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Figure 2.

The predictive value of C3, C4, SOD and TAC for stroke. The AUC of C3, C4, SOD and TAC for predicting stroke were 0.687, 0.540, 0.750 and 0.714, respectively. SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; AUC, area-under-the-curve.

Univariate analysis

The patients were divided into a stroke group (n=122) and a healthy group (n=53) according the occurrence of stroke. Their clinical data were collected and analyzed through univariate analysis. The two groups had no differences in sex, age, BMI, smoking, drinking, place of residence, COPD or C4 (all P>0.05). There were differences in hyperlipidemia, hypertension, C3, SOD and TAC (all P<0.05) (Table IV).

Table IV.

Univariate analysis.

| Stroke group (n=122) | Healthy group (n=53) | χ2 value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] | 0.073 | 0.788 | ||

| Male | 71 (58.20) | 32 (60.38) | ||

| Female | 51 (41.80) | 21 (39.62) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.138 | 0.710 | ||

| <40 | 47 (38.52) | 22 (41.51) | ||

| ≥40 | 75 (61.48) | 31 (58.49) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.251 | 0.616 | ||

| ≥25 | 39 (31.97) | 19 (35.85) | ||

| <25 | 83 (68.03) | 34 (64.15) | ||

| Smoking [n (%)] | <0.001 | 0.978 | ||

| Yes | 78 (63.93) | 34 (64.15) | ||

| No | 44 (36.07) | 19 (35.85) | ||

| Drinking [n (%)] | 0.142 | 0.707 | ||

| Yes | 84 (68.85) | 38 (71.70) | ||

| No | 38 (31.15) | 15 (28.30) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia [n (%)] | 10.790 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 87 (71.31) | 24 (45.28) | ||

| No | 35 (28.69) | 29 (54.72) | ||

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 12.690 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 95 (77.87) | 27 (50.94) | ||

| No | 27 (22.13) | 26 (49.06) | ||

| Place of residence [n (%)] | 0.081 | 0.776 | ||

| Urban area | 57 (46.72) | 26 (49.06) | ||

| Rural area | 65 (53.28) | 27 (50.94) | ||

| COPD [n (%)] | 0.011 | 0.916 | ||

| Yes | 54 (44.26) | 23 (43.40) | ||

| No | 68 (55.74) | 30 (56.60) | ||

| C3 (g/l) | 1.63±0.27 | 1.10±0.12 | 13.700 | <0.001 |

| C4 (g/l) | 0.28±0.15 | 0.30±0.09 | 0.902 | 0.368 |

| SOD (U/ml) | 119.22±12.42 | 161.20±21.12 | 16.400 | <0.001 |

| TAC (U/ml) | 14.17±2.48 | 18.24±1.75 | 10.830 | <0.001 |

SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAC, total antioxidant capacity.

Multivariate analysis of stroke in the patients

We performed assignment to indexes with differences in univariate analysis (Table V) and performed logistic regression analysis. The results revealed that hypertension and hyperlipidemia were independent risk factors of stroke (Table VI).

Table V.

Valuation.

| Dependent variable | Assignment |

|---|---|

| Hyperlipidemia | Yes=0, No=1 |

| Hypertension | Yes=0, No=1 |

| C3 | Raw data of those belonging to continuous variable were used for analysis. |

| SOD | Raw data of those belonging to continuous variable were used for analysis. |

| TAC | Raw data of those belonging to continuous variable were used for analysis. |

SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAC, total antioxidant capacity.

Table VI.

Logistic multivariate analysis of stroke.

| 95% CI of Exp (B) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Wals | Sig. | Exp (B) | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.045 | 0.343 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.956 | 0.489 | 1.872 |

| Hypertension | −0.005 | 0.359 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.995 | 0.493 | 2.01 |

| C3 | −1.147 | 0.428 | 5.575 | 0.723 | 0.409 | 0.117 | 0.819 |

| SOD | −1.114 | 0.446 | 5.876 | 0.267 | 0.310 | 0.120 | 0.799 |

| TAC | −1.157 | 0.489 | 5.387 | 0.457 | 0.315 | 0.118 | 0.835 |

SOD, superoxide dismutase; TAC, total antioxidant capacity.

Discussion

ACI and CH are common diseases that endanger life and health of the middle-aged and the elderly. Vascular atherosclerosis is a common reason, and it is an inflammatory process of plaque formation, development and deposition (12). Cerebral infarction indicates the injury degree of microvascular endothelial cells and brain parenchyma cells due to ischemia, which is closely related to oxygen free radicals. The main reason for the aggravation of cerebral ischemia-induced brain injury is the abnormal increase of oxygen free radicals, and the enhancement of oxygen free radical reactions is an important reason for cerebral edema secondary to CH (13). Stroke treatment is currently limited by lack of accurate and reliable blood biomarkers, and its identification will be helpful for early diagnosis and risk prediction (14).

C3 and C4, as key factors in the complement system, play an important role in various inflammation-related diseases (15,16). In this study, the C3 level in the CIG and the CHG was higher than that in the CG, suggesting that C3 level would increase in ACI and CH, and may be used as a routine serum marker to evaluate the two diseases. In contrast, the C4 level in the former two groups was lower than that in the latter group, which may be due to the decrease of consumption caused by the stress state of the body at the initial stage of the disease. A study by Anrather and Iadecola (17) pointed out that complement system was a humoral branch of natural immunity, which was always related to the pathobiology of stroke, and its activation was linked to the adverse outcomes of stroke. The study also indicated that C3a receptor antagonists could alleviate ischemic brain injury and improve brain function. It was consistent with our experimental results. Based on these results, we speculated that the detection of relevant complement levels in stroke diseases could play a certain clinical guiding role in the clinical diagnosis and prognosis of the diseases.

SOD and TAC are commonly used oxidative stress parameters to eliminate excess oxygen free radicals and avoid cell damage (18,19). In this study, SOD and TAC levels in the CIG and the CHG were lower than those in the CG, indicating that SOD and TAC levels were related to ACI and CH. Relevant studies have pointed out that oxidative stress is one of the main pathophysiological mechanisms of inflammation in the central nervous system and neurodegenerative diseases, and was related to stroke diseases (20,21). A study by Milanlioglu et al (22) concluded that patients with acute ischemic stroke showed enhanced oxidative stress reaction, and weakened antioxidant enzyme activity, suggesting that imbalance of oxidant/antioxidant status may be a part of the pathogenesis of acute ischemic stroke. It further proves that the detection of SOD level is effective in evaluating ACI and CH to a certain degree.

This study additionally employed NIHSS to score the neurological function injury of stroke patients, and determined their serum hs-C3, SOD and TAC levels, finding that patients with a more severe neurological function injury showed a higher C3 level, and lower SOD and TAC levels. A study by Zhang et al (23) reported that the high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) of the NIHSS >5 group was dramatically higher than that of the NIHSS ≤5 group, and hs-CRP has been proved to be related to stroke by many studies (24). Therefore, we speculated that C3, SOD and TAC levels were related to the severity of ACI and CH, and they were expected to be biomarkers of evaluating prognosis. We also studied the predictive value of the four markers of stroke in this study, finding that SOD had a relatively good predictive value among the four markers, but further exploration is needed in this direction. In this study, the Logistic regression analysis revealed that hypertension and hyperlipidemia were independent risk factors of stroke. Moreover, studies by Li et al (25) and Hsieh and Chiou (26) also reported that hypertension and hyperlipidemia were risk factors of stroke. Therefore, it is a reminder of the importance to actively control blood pressure and blood lipid level in daily life to avoid ACI and CH to some extent.

In conclusion, the serum complement and oxidative stress parameters in patients with ACI or CH can be determined through routine examination, and the nerve function deficit could be assessed by determining the complement and oxidative stress parameters in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

MZ was responsible for the determination of serum C3, C4, SOD and TAC levels, and wrote the manuscript. XW and JY conceived and designed the study. SM and YW were responsible for the collection and analysis of the experimental data. SL and SM interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. MZ and XW revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Zhangqiu Area (Jinan, China). Patients who participated in this research had complete clinical data. Signed informed consents were obtained from the patients and/or guardians.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120:439–448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, Bonafe A, Budzik RF, Bhuva P, Yavagal DR, Ribo M, Cognard C, Hanel RA, et al. DAWN Trial Investigators Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV, Xiang J, Stamatovic SM, Antonetti DA, Hua Y, Xi G. Brain endothelial cell junctions after cerebral hemorrhage: Changes, mechanisms and therapeutic targets. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:1255–1275. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18774666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.An SJ, Kim TJ, Yoon BW. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J Stroke. 2017;19:3–10. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.00864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai M, Wang D, Lin Z, Zhang Y. Small molecule copper and its relative metabolites in serum of cerebral ischemic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Gao C, Yu C, Liu S, Hou D, Wang Y, Wang C, Mo L, Wu J. No association between elevated total homocysteine levels and functional outcome in elderly patients with acute cerebral infarction. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:70. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanning JP, See Hoe LE, Passmore MR, Barnett AG, Rolfe BE, Millar JE, Wesley AJ, Suen J, Fraser JF. Differential immunological profiles herald magnetic resonance imaging-defined perioperative cerebral infarction. Ther Adv Neurol Disorder. 2018 Mar 13; doi: 10.1177/1756286418759493. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1177/1756286418759493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono H, Nishijima Y, Ohta S, Sakamoto M, Kinone K, Horikosi T, Tamaki M, Takeshita H, Futatuki T, Ohishi W, et al. Hydrogen gas inhalation treatment in acute cerebral infarction: A randomized controlled clinical study on safety and neuroprotection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2587–2594. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronowski J, Zhao X. Molecular pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: Secondary brain injury. Stroke. 2011;42:1781–1786. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lattanzi S, Brigo F, Trinka E, Cagnetti C, Di Napoli M, Silvestrini M. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute cerebral hemorrhage: A system review. Transl Stroke Res. 2019;10:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bravata DM, Sico J, Vaz Fragoso CA, Miech EJ, Matthias MS, Lampert R, Williams LS, Concato J, Ivan CS, Fleck JD, et al. Diagnosing and treating sleep apnea in patients with acute cerebrovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008841. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu S, Guo J. Clinical significance and difference of some biochemical indexes in patients with cerebral infarction and cerebral hemorrhage. Xiandai Jianyan Yixue Zazhi. 2018;33:114–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi FM, Yuan X, Dong Y. Analysis of SOD and HCY in acute cerebral infarction and acute cerebral hemorrhage patients. Int J Lab Med. 2015;10:1323–1324. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Zhang J. Identification of miRNA-21 and miRNA-24 in plasma as potential early stage markers of acute cerebral infarction. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:971–976. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Z, Lin H, Li W, Huang Y, Dai H. Complement component C3 promotes cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury mediated by TLR2/NFκB activation in diabetic mice. Neurochem Res. 2018;43:1599–1607. doi: 10.1007/s11064-018-2574-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simats A, García-Berrocoso T, Montaner J. Neuroinflammatory biomarkers: From stroke diagnosis and prognosis to therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:411–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anrather J, Iadecola C. Inflammation and stroke: An overview. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13:661–670. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0483-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ighodaro OM, Akinloye OA. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonullu H, Aslan M, Karadas S, Kati C, Duran L, Milanlioglu A, Aydin MN, Demir H. Serum prolidase enzyme activity and oxidative stress levels in patients with acute hemorrhagic stroke. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:199–205. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2013.873949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estevez AY, Stadler B, Erlichman JS. In-vitro analysis of catalase-, oxidase-and SOD-mimetic activity of commercially available and custom-synthesized cerium oxide nanoparticles and assessment of neuroprotective effects in a hippocampal brain slice model of ischemia. FASEB J. 2017;31:693.5–693.5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llull L, Amaro S, Chamorro Á. Administration of uric acid in the emergency treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:4. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milanlioglu A, Aslan M, Ozkol H, Çilingir V, Nuri Aydın M, Karadas S. Serum antioxidant enzymes activities and oxidative stress levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke: Influence on neurological status and outcome. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Huang WJ, Yu ZG. Relationship between the hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) level and the prognosis of acute brainstem infarction. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72:107–110. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Kwon KY, Yoon SY, Kim HS, Lim CS. Characteristics of platelet indices, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and erythrocyte sedimentation rate compared with C reactive protein in patients with cerebral infarction: A retrospective analysis of comparing haematological parameters and C reactive protein. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006275. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Jin C, Vaidya A, Wu Y, Rexrode K, Zheng X, Gurol ME, Ma C, Wu S, Gao X. Blood pressure trajectories and the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and cerebral infarction: A prospective study. Hypertension. 2017;70:508–514. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh FI, Chiou HY. Stroke: Morbidity, risk factors, and care in Taiwan. J Stroke. 2014;16:59–64. doi: 10.5853/jos.2014.16.2.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.