Dear Editor:

More than 140 million emergency department (ED) visits occur each year in the United States. Of these, 70%–80% involve patients with serious illness that could not be safely treated in an outpatient setting, resulting in >11 million hospitalizations annually.1 More than 80% of patients are admitted through the ED, and 18% are admitted to intensive care units. Both primary care physicians and specialists report that they are increasingly reliant on EDs to evaluate complex patients with potentially serious medical problems.1,2

During their residency training, emergency medicine (EM) resident physicians frequently have conversations with their patients regarding goals of care (e.g., code status). Yet, most of these residents do not receive any training in how to lead these conversations, nor does the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education require it.3 Not surprisingly, many surveyed EM residents report feeling uncomfortable conducting these conversations.4 Education aimed at increasing skill and confidence in this area for EM residents is needed; however, this has not been studied to-date.

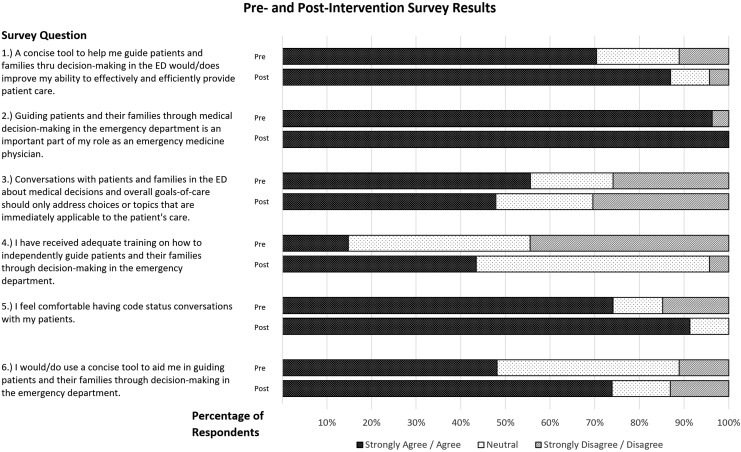

We sought to determine the effect of a brief educational intervention on EM resident perceptions of and comfort with serious illness conversations, here in a 59-person urban tertiary residency program. In this Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved study, EM and palliative medicine attending physicians cotaught a two-hour educational intervention with didactic and simulation components. Residents were also introduced to a communication framework for high-stakes surgical decision conversations called the “Best Case/Worst Case.”5 We assessed the residents' perception and comfort level with leading serious illness conversations using pre-/post-intervention surveys. Response options were based on a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree). Results are shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Survey responses. ED, emergency department.

In our single-program study, a brief educational intervention improved EM residents' comfort with serious illness conversations. Further study is needed to assess intervention generalizability in other EM residency programs, and whether increased comfort correlates with increased competence. The latter question will be particularly important to study, as physicians historically overestimate their competence in communication skills.6 Ultimately, if brief educational interventions can increase resident comfort and competence, we must incorporate such training into standard EM residency curricula.

References

- 1.Emergency Department Visits: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm (Last accessed May3, 2017)

- 2.Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. :. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2013. ISBN 9780833080790 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Emergency Medicine: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Approved July 1, 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/110_emergency_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf (last accessed May1, 2018)

- 4.Lamba S, Mosenthal A, Rella J, et al. : Emergency medicine resident education in palliative care: A needs assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:333–334 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarze ML: Best Case/Worst Case Training Program. UW—Madison Department of Surgery, 2016. https://www.hipxchange.org/BCWC (last accessed May1, 2018)

- 6.Ha JF, Longnecker N: Doctor-patient communication: A review. Ochsner J 2010;10:38–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]